Abstract

The Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) plays a vital role in financing behavioral health services for low-income children. This study examines behavioral health benefit design and management in separate CHIP programs on the eve of federal requirements for behavioral health parity. Even before parity implementation, many state CHIP programs did not impose service limits or cost sharing for behavioral health benefits. However, a substantial share of states imposed limits or cost sharing that might hinder access to care. The majority of states use managed care to administer behavioral health benefits. It is important to monitor how states adapt their programs to comply with parity.

Keywords: Behavioral Health Policy, Financing, Parity, Children

Introduction

Recently enacted federal legislation will bring significant changes to the scope and delivery of behavioral health services, or services to treat mental illness and substance use disorders, in the United States. Historically, coverage for behavioral health services was more limited than coverage for general medical health services (Barry 2006). With the 2010 implementation of new parity requirements under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 (MHPAEA), payers that provide both medical/surgical and behavioral health benefits are required to do so with similar financial requirements and treatment limitations across service categories. Parity is expected to both expand coverage for mental health and substance use disorder services and restructure the use of cost and quality management tools to manage behavioral health benefits (Dixon 2009; Shern et al. 2009).

Notably, federal parity requirements will impact coverage available under the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), publicly financed insurance for children in families earning too much to qualify for Medicaid but without adequate income or alternative access to health insurance.1 The CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHI-PRA) required state CHIP programs to comply with the 2008 federal parity law (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] 2009a,Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] 2010a).2 Coverage of behavioral health services under CHIP plays an important role in financing vital services. Many behavioral health problems emerge early in life (Costello et al. 2003), and treatment at this early stage of disease can be particularly effective (Evans et al. 2005). Further, low-income children covered by CHIP have higher rates of behavioral health problems than privately insured or uninsured children (Brach et al. 2003; Howell 2004), yet their families have limited resources to absorb the cost of services not covered by insurance. Data from the Child Health Insurance Research Initiative indicates that CHIP enrollees with special needs reported difficulty accessing mental health and substance abuse treatment services (VanLandeghem et al. 2006). Research shows that parity laws can reduce the financial burden of a family having a child with a mental health need (Azrin et al. 2007; Barry and Busch 2007). Thus, access to behavioral health treatment for children enrolled in these programs is important to minimizing the personal and societal costs of mental health and substance use disorders for a vulnerable population.

Under CHIP, states may administer their programs as Medicaid expansions or as separate, non-Medicaid programs. States with separate, non-Medicaid programs vary widely in program design, especially for behavioral health services. State choices in benefit design have implications for children’s access to such services. Evidence suggests that use of behavioral health services among children with addictive and psychiatric disorders is related to generosity of insurance coverage for those benefits (Ganz and Tendulkar 2006; McAlpine and Mechanic 2000; Mechanic 2001, 2007). For example, compared to uninsured children and children covered by private insurance, children enrolled in Medicaid (which typically has more generous benefits than other types of coverage) were less likely to have an unmet need for mental health care (Kataoka et al. 2002). Behavioral health conditions among children may be associated with high levels of utilization or out-of-pocket cost (Busch and Barry 2009; Soni 2009), and children facing service limits or cost sharing requirements may forego care in the face of service limits.

Despite the importance of benefit design choices, we lack up-to-date information to assess how states design behavioral health benefits in CHIP on the eve of parity implementation (Rosenbach et al. 2002, 2003; SAMHSA 2000). As the basis to understanding the potential impact of parity requirements on benefit design and access to services, this study provides new, state-by-state information on insurance benefit design and management of behavioral health services in separate, non-Medicaid CHIP programs on the eve of implementation of federal parity requirements. These data provide a baseline for ongoing study of the impact of parity on behavioral health service access for children in CHIP programs. Specifically, we detail scope of coverage, cost sharing, and management for both mental health and substance use disorder services in late 2009, before parity regulations were released by the Obama administration. We then discuss the implications of state coverage decisions for the implementation of parity and states’ ability to improve access while managing costs.

Method

The study sample includes states with separate (non-Medicaid expansion) Title XXI programs as of December 2009. We exclude from the sample states with separate programs that serve only unborn children, resulting in a sample of 40 states. In some state programs, coverage varies within CHIP (for example, by health plan or by income level). We count such programs as single states but collect information on each level of coverage within the state. A small number of states (6/40) made parity-related changes to their policies midway through the 2009 calendar year. Our data reflect the policies that were in place for the majority (≥6 months) of the 2009 calendar year.

Our data collection took place in three steps. First, we culled state-by-state information from publicly available sources. These sources included state CHIP plans, amendments, and annual reports submitted to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; plan information and benefits handbooks available directly from state programs; and previously published reports on behavioral health benefits in Title XXI. Second, we analyzed and compared the information available from various sources to identify missing or conflicting information and develop standardized categories of benefit design. Third, we contacted officials in each state to confirm, clarify and update published information. The response rate from state officials was 97.5%. Data were collected between July 2009 and April 2010.

We created coding schemes to categorize and group states by generosity of coverage. Specifically, we characterized the scope of coverage for behavioral health services in separate CHIP programs based on: annual limits on inpatient days and outpatient visits for mental health and substance use disorder services; cost sharing requirements for those services as well as psychotropic prescription drugs; and annual or lifetime dollar limits on behavioral health services. We also collected and analyzed data on the delivery model for behavioral health services (e.g., use of managed behavioral health care organizations) and care management strategies (e.g., initial visit allocations or prior authorization). We examined count data for the number of states falling into categories of interest. To further categorize states, we developed a typology based on whether the state used day/visit limits for any service and whether the state used cost sharing for any service (including prescription drugs). Last, we calculated correlation coefficients (φ) between (i) no use of service limits or cost sharing and (ii) use of managed care for service delivery.

Results

Results for state-by-state coverage of inpatient and outpa-tient behavioral health services are provided in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. States that did not use a day/visit limit to define the scope of coverage are coded as “no limit.” However, programs in these states may have (and typically did) used other mechanisms to control utilization, such as requirements for medical necessity, prior authorization/utilization review, or network and contracting limitations for providers. Thus, “no limit” for the number of covered days or visits should not be interpreted as unrestricted coverage of services. We discuss service delivery and management of behavioral health services in greater detail below.

Table 1.

Inpatient behavioral health coverage in separate CHIP programs, 2009

| State | Mental health services

|

Substance use disorder services

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day limit | Cost sharing | Day limit | Cost sharing | |

| AL | 30 days/year | ≤150% FPL: $5 >150% FPL: $10 |

3 days detox/year | ≤150% FPL: $5 >150% FPL: $10 |

| AZ | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| AR | Not covered | 100% (service not covered) | Not covered | 100% (service not covered) |

| CA | 30 days/year | No co-pay | Detox only | No co-pay |

| CO | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| CT | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| DE | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| FL* | 30 days/year | No co-pay | 7 days/year for detox; 30 days/year residential | No co-pay |

| GA | 30 days/admission | No co-pay | 30 days/admission | No co-pay |

| ID | 10 days/yeara | No co-pay | 10 days/yeara | No co-pay |

| IL | No limit | 133–150% FPL: $2 >150% FPL: $5 |

No limit | No co-pay |

| IN | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| IA** | No limit | No co-pay | 30 days/year | No co-pay |

| KS | No limit | No co-pay | 60 days/year | No co-pay |

| KY | No limit | No co-pay | Not covered | 100% (service not covered) |

| ME | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| MA | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| MI | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| MS | 30 days/year | No co-pay | $8,000/Benefit Periodb | No co-pay |

| MO | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| MT | 21 days/year | $25 | $6000/yearb,c | $25 |

| NV | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| NH | 15 days/year | No co-pay | 30 days/year; no limit for detox | No co-pay |

| NJ | 133–200% FPL: None 201–350% FPL: 35 days/year |

No co-pay | 133–200% FPL: None 201–350% FPL: Detox only |

No co-pay |

| NY* | 30 days/yeard | No co-pay | 30 days/yeard | No co-pay |

| NC | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| ND | 45 days/yeard | $50/visit | 45 days/yeard | $50/visit |

| OR | Nonee | No co-pay | Nonee | No co-pay |

| PA* | 90 days/yearf | No co-pay | 7 days detox/admission | No co-pay |

| SC | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| SD | No limit | No co-pay | 45 days/year | No co-pay |

| TN** | No limit | <150% FPL: $5 150–200% FPL: $100 |

No limit | <150% FPL: $5 150–200% FPL: $100 |

| TX | 45 days/year | 101–150% FPL: $25 151–185% FPL: $50 186–200% FPL: $100 |

14 days/year detox/crisis stabilization, 60 days/year residential treatment | 101–150% FPL: $25 151–185% FPL: $50 186–200% FPL: $100 |

| UT** | No limit | 0–100% FPL: $50 101–150% FPL: $150 after $40/family deductible 151–200% FPL: 20% of total after$1500/family deductible |

No limit | 0–100% FPL: $50 101–150% FPL: $150 after $40/family deductible 151–200% FPL: 20% of total after$1500/family deductible |

| VT | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| VA | 30 days/year | ≤150% FPL: $15 >150% FPL: $25 |

90 days/life | ≤150% FPL: $15 >150% FPL: $25 |

| WA | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| WV | 30 days/yeard | No co-pay | 30 days/yeard | No co-pay |

| WI | ≤200% FPL: No limit 201–300% FPL: 30 days/year |

≤200% FPL: $3/day, up to $75 per stay 201–300% FPL: $50/stay |

≤200% FPL: No limit201–300% FPL: 30 days/year | ≤200% FPL: $3/day, up to $75 per stay 201–300% FPL: $50/stay |

| WY | 21 days/yearg | ≤100% FPL: $0 101–150% FPL: $30 151–200% FPL: $50 |

$6,000/yearb; 21 days/year for detox services | ≤100% FPL: $0 101–150% FPL: $30 151–200% FPL: $50 |

Source: Information collected from state policymakers, state CHIP plans, and state program/benefits information FPL Federal Poverty Level. In 2009, the FPL for a family of four was $22,020

Children in the “Enhanced Plan” (for children with special health needs) have no day limit on services, with the exception of residential treatment services for substance use disorder (which are not covered)

Combined limit for inpatient and outpatient services

Montana’s substance use disorder benefit also has a lifetime maximum benefit of $12,000; after enrollees hit lifetime limit, plan will cover services up to $2,000/year limit

Combined limit for mental health and substance use disorder services

No limit for services that fall within scope outlined in prioritized list. See http://www.oregon.gov/OHPPR/HSC/docs/Oct09MHCDlines.pdf

Combined limit for behavioral and medical/surgical health

Additional 9 days available with prior authorization

State made policy change in 2009. Data represents policies prior to change

State made policy change in 2009. Data represents policies after change

Table 2.

Outpatient behavioral health coverage in separate CHIP programs, 2009

| State | Mental health services

|

Substance use disorder services

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visit limit | Cost sharing | Visit limit | Cost sharing | |

| AL | 20 visits/year | No co-pay | 20 visits/year | No co-pay |

| AZ | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| AR | No limit | $10/visit | Nonea | $10/visit |

| CA | 20 visits/year | $5/visit | 20 visits/year | $5/visit |

| CO | No limit | 101–150% FPL: $2 >150% FPL: $5 |

No limit | 101–150% FPL: $2 >150% FPL: $5 |

| CT | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| DE | 30 visits/year | No co-pay | 30 visits/year | No co-pay |

| FL* | 40 visits/year | $5/visit | 40 visits/year | $5/visit |

| GA | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| ID | 26 services/yearb | No co-pay | 12 h/year for counseling | No co-pay |

| IL | No limit | 133–150% FPL: $2 >150% FPL: $5 |

No limit | No co-pay |

| IN | 50 visits/year | No co-pay | 50 visits/year | No co-pay |

| IA** | No limit | No co-pay | 20 or 30 visits/year depending on plan | No co-pay |

| KS | No limitc | No co-pay | No limitc | No co-pay |

| KY | No limit | No co-pay | Not covered | 100% (service not covered) |

| ME | 2 h/week | $2/day of serviced | 3 h/week | $2/day of serviceb |

| MA | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| MI | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| MS | 52 visits/year | $5/visit | $8,000/Benefit Periode | $5/visit |

| MO | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| MT | 20 visits/year | $3 | $6000/yeare,f | $3 |

| NV | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| NH | 20 visits/yeard | $10/visit | 20 visits/yeard | $10/visit |

| NJ | 133–200% FPL: None 201–350% FPL: 20 days/year |

133–200% FPL: None 201–350% FPL: $25 |

133–200% FPL: None 201–350% FPL: Detox only |

133–200% FPL: None 201–350% FPL: $25 |

| NY* | 60 days/yeard | No co-pay | 60 days/yeard | No co-pay |

| NC | 26 visits/yeard,g | ≤150% FPL: none >150% FPL: $5 |

26 visits/yeard,g | ≤150% FPL: none >150% FPL: $5 |

| ND | 30 h/year | No co-pay | 20 visits/year | No co-pay |

| OR | No limith | No co-pay | No limith | No co-pay |

| PA* | 50 visits/year | No co-pay | 90 visits/year | No co-pay |

| SC | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| SD | 40 h/year for individual therapy; otherwise, no limit | No co-pay | 60 h/year | No co-pay |

| TN** | No limit | <150% FPL: $5 150–200% FPL: $20 |

No limit | <150% FPL: $5 150–200% FPL: $20 |

| TX | 60 visits/year plus 60 rehabilitative treatment days/year | 101–150% FPL: $5 151–185% FPL: $7 186–200% FPL: $10 |

12 weeks/year for intensive outpatient plus6 months/year for outpatient services | 101–150% FPL: $5 151–185% FPL: $7 186–200% FPL: $10 |

| UT** | No limit | 101–150% FPL: $5 151–200% FPL: $30 |

No limit | 101–150% FPL: $5 151–200% FPL: $30 |

| VT | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| VA | 50 visits/yeard | ≤150% FPL: $2 >150% FPL: $5 |

50 visits/yeard | ≤150% FPL: $2 >150% FPL: $5 |

| WA | No limit | No co-pay | No limit | No co-pay |

| WV | 26 visits/yeard | No co-pay | 26 visits/yeard | No co-pay |

| WI | No limit | ≤200% FPL $0.50–$3/visit 201–300% FPL $10–$15/visiti |

No limit | ≤200% FPL $0.50–$3/visit 201–300% FPL $10–$15/visiti |

| WY | 20 visits/yearg | ≤100% FPL: $0 101–150% FPL: $5 151–200% FPL: $10 |

$6,000/year in/outpatient combined; 21 days/year for detox services | ≤100% FPL: $0 101–150% FPL: $5 151–200% FPL: $10 |

Source: Information collected from state policymakers, state CHIP plans, and state program/benefits information FPL Federal Poverty Level. In 2009, the FPL for a family of four was $22,020

Primary diagnosis must be mental health; otherwise, service not covered

Children in the “Enhanced Plan” (for children with special health needs) receive up to 45 h/year psychotherapy, 12 h/week for partial care, and 10 h/week for psychosocial rehabilitation

Outpatient Treatment Request required after first 6 sessions

Combined limit for mental health and substance use disorder services

Combined limit for inpatient and outpatient services

Montana’s substance use disorder benefit also has a lifetime maximum benefit of $12,000; after enrollees hit lifetime limit, plan will cover services up to $2,000/year limit

Additional visits allowed with prior approval

No limit for services that fall within scope outlined in prioritized list. See http://www.oregon.gov/OHPPR/HSC/docs/Oct09MHCDlines.pdf

Co-pay for up to 200% FPL is based on Medicaid/BadgerCare Plus maximum allowable fee for the service provided; no copay for narcotic treatment services. Co-pay for 200–300% FPL does not apply to laboratory tests, electroconvulsive therapy, and pharmacological management

State made policy change in 2009. Data represents policies prior to change

State made policy change in 2009. Data represents policies after change

Very few states (7/40) relied on annual or lifetime dollar limits for behavioral health services under CHIP as of 2009. Three of those states (Mississippi, Montana, and Wisconsin) used dollar limits for substance use disorder services only, while the four remaining states (Florida, North Dakota, West Virginia, Wyoming) have overall plan lifetime limits (e.g., $1 million) for all health services.

Day/Visit Limits

Over a third (14/40) of states with separate CHIP programs did not place any day or visit limits on any behavioral health services in 2009, while a slightly larger share (15/40) had such limits for all behavioral health (inpatient and outpatient, mental health and substance use disorder) services. The remaining states (11/40) used day/visit limits for some but not all services.

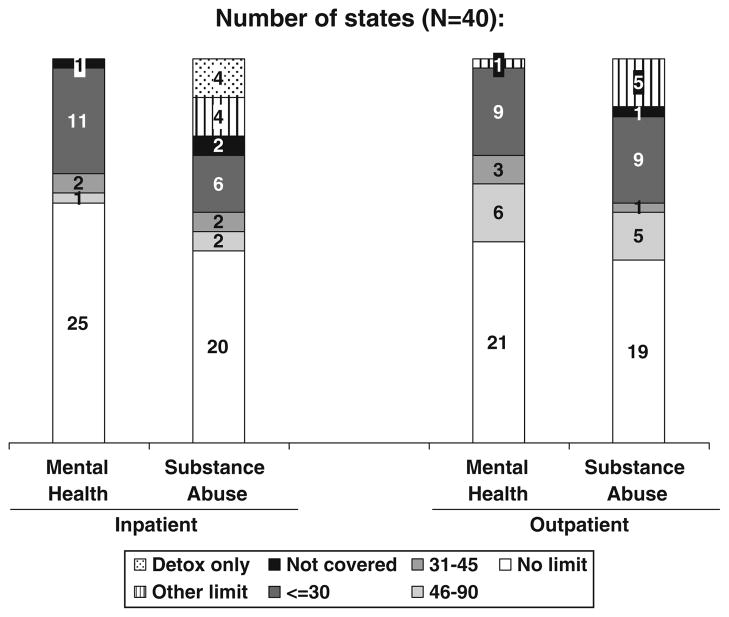

Figure 1 summarizes use of day/visit limits for both inpatient and outpatient mental health and substance use disorder services in separate CHIP programs. Nearly two-thirds (25/40) of states with separate CHIP programs in 2009 placed no day limit on inpatient mental health services. Half had no day limit on inpatient substance use disorder services. Among states using limits, most limited inpatient services to one month. Inpatient limits of 30 days or less per year were in place in 30% of state programs for mental health services and 40% for substance use disorder services. For inpatient substance use disorder services, 10% (4/40) of states covered only detoxification services.

Fig 1.

Day/visit limits for behavioral health benefits in separate CHIP plans as of 2009. Note: Inpatient limits are measured in days/year; outpatient limits are measured in visits/year. States whose limits vary by income or plan (ID, IA, NJ, WI) were categorized by most generous limit in the state. Some states’ limits apply to combined MH/SA services (inpatient: NY, ND, WV; outpatient: NH, NY, NC, VA, WV) or combined BH/physical health services (PA). AR covers SA services only when the primary diagnosis is mental illness. “Other limit” includes: ME (2/3 h/week limit for outpatient MH/SA services); MS ($8000 limit on inpatient and outpatient SA per benefit period); MT ($6000/year & $12,000/lifetime limit on inpatient and outpatient SA); TX (12 weeks/year outpatient SA limit); VA (90 days/lifetime inpatient SA limit); WY ($6,000/year limit for combined inpatient/outpatient SA treatment). Source: Authors’ analysis of information collected from state policymakers, state CHIP plans, and state program/benefits information

Approximately half of state programs had no visit limit for outpatient mental health (21/40) or substance use disorder (19/40) services. One quarter (10/40) of states and 15 out of 40 states limited outpatient mental health and substance use disorder visits to less than 30 days per year, respectively. Of these states, many limited services to the equivalent of once every 2 weeks, or 26 visits per year (7 states for mental health services, 8 for substance use disorder services).

Cost Sharing

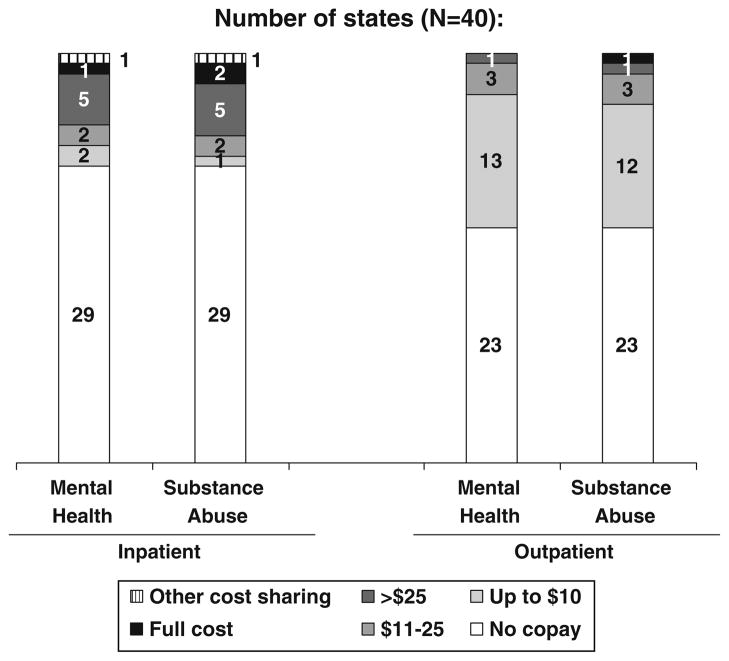

Half of state programs (20/40) did not impose cost sharing for either inpatient or outpatient behavioral health services, while 20% (8/40) had cost sharing in place for both inpatient and outpatient services for both mental health and substance use disorders. About a third (12/40) used cost sharing for some, but not all, services.

As shown in Fig. 2, the majority (29/40) of state programs did not impose cost sharing for inpatient mental health or substance use disorder services. In states that used cost sharing in their separate CHIP programs, co-payments for inpatient mental health ranged from $5/stay to $100/stay, with an average co-payment of $46/stay. [For inpatient substance use disorder services, the co-payment range was $10/visit to $100/visit, with an average of $51.] Over half (23/40) of states had no cost sharing for outpatient mental health or substance use disorder services. States that did impose co-payments for outpatient services used levels that range from $2/visit to $30/visit, with an average co-payment of $10/visit.

Fig 2.

Co-payments for behavioral health benefits in separate CHIP plans as of 2009. Note: In states where cost sharing varies by family income, highest possible cost sharing level is used to group state. “Full cost” indicates that service is not covered and families may face entire cost for services. Other cost sharing includes UT, where the highest income group pays 20% of total after deductible ($500 per child or $1,500 per family) for inpatient services. Source: Authors’ analysis of information collected from state policymakers, state CHIP plans, and state program/benefits information

Most state programs (23/40) imposed cost sharing for prescription drugs, including psychotropic medications. Co-payments ranged from $1 to $40 and typically varied by branded/generic and formulary tier. Among states that used co-payments for prescription drugs, the average co-pay requirement was $10/prescription. However, this figure does not account for the mix of drugs used by beneficiaries: for example, the average co-pay for generic drugs (among states using prescription drug cost sharing) was $4.60.

Service Delivery and Care Management

Most states (29/40) used managed care to deliver behavioral health services to at least some CHIP enrollees. The nature of managed care arrangements varied substantially across states. Eight states used a single, state-wide managed care company to deliver behavioral health services to all children in separate CHIP program, while 16 states had multiple managed care organizations (MCOs) serving their CHIP population for behavioral health. Slightly more than a quarter (11/40) used only fee-for-service or primary care case management to deliver behavioral health services, and five states relied on a mix of MCOs and fee-for-service to deliver behavioral health services.

Similarly, states varied widely in whether they carve out or integrate behavioral health services from medical/surgical health services. In seven state programs (CT, KS, MI, NJ, NC, UT, WA), behavioral health services were carved out from medical/surgical health services for all enrollees. In nine additional states (CA, DE, FL, GA, KY, MA, OR, PA, TX), behavioral health services may have been carved out for some enrollees, as many states left the decision to carve out or integrate to the MCOs that serve their enrollees.

All 40 states reported using care management tools for behavioral health services under separate Title XXI programs, though techniques used vary across states. Often, decisions about which care management tools to use (or when to use them) were left to MCOs. However, many states either developed their own management procedures or specified procedures in MCO contracts. The most common care management tool cited by state officials was prior authorization for services, particularly inpatient care (29 states). Many states (15) also cited retrospective utilization review for at least some services, while few states (6) specifically mentioned case management as a core care management tool. Care should be taken in interpreting these results, however, as state officials stressed that some techniques are applied in special situations (e.g., prior authorization for over a certain number of inpatient days) or for special populations (e.g., case management for children with serious emotional disturbances).

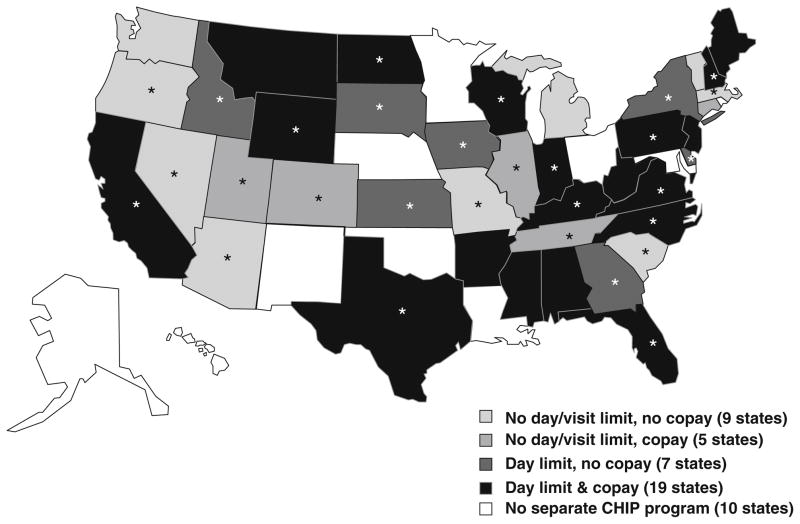

Categorizing States by Generosity of Coverage

States may rely on different combinations of the approaches described above in designing behavioral health benefits under CHIP. To categorize states, we developed a typology based on two factors: whether the state used day/visit limits for any service and whether the state used cost sharing for any service (including prescription drugs). As shown in Fig. 3, nine states did not use any day/visit limits or cost sharing for inpatient, outpatient or pharmaceutical behavioral health services. States that did use these mechanisms in designing behavioral health benefits were more likely to use both day/visit limits and cost sharing (19/40) than to rely on just one approach. Four states (MT, TX, VA, and WY) used both day/visit limits and cost sharing for all behavioral health services.

Fig 3.

Coverage of behavioral health services in separate CHIP programs, 2009. Source: Authors’ analysis of information collected from state policymakers, state CHIP plans, and state program/benefits information

States that did not rely on approaches such as day/visit limits or co-payments may rely on care management mechanisms in controlling utilization. We examined service delivery and management among the nine states that did not use limits or co-pays. No clear pattern emerges. Three of the nine states (MI, VT, WA) used only fee-for-service delivery for behavioral health (correlation between managed care and no limits/copayments = 0.07, p = 0.67), and two of the nine (MI, WA) carved out behavioral health for all enrollees (correlation between use of carve out and no limits/copayments = 0.05, p = 0.76). As with the full sample, all of the nine states used care management tools such as prior authorization, case managers, and retrospective utilization review.

Discussion

Our analysis of coverage of behavioral health services in separate CHIP programs found that nearly two-thirds of states used day or visit limits for some or all behavioral health services in 2009. Such limits were more likely to be in place for substance use disorder services (versus mental health services) and for outpatient services (versus inpatient services). Further, half of states imposed cost sharing for at least some behavioral health services under CHIP. Co-payments ranged from $0 to $100 for inpatient services, $0 to $30 for outpatient services, and $0 to $40 for prescription drugs. Use of managed care to deliver behavioral health services was very common, and most states relied on a range of care management tools to administer benefits.

Even before the implementation of parity requirements, many state CHIP programs did not impose service limits or cost sharing for behavioral health benefits. However, a substantial share of states imposed limits or cost sharing that might hinder access to care. Many children with behavioral health problems need a high level of services: Among youth aged 12–17 who received outpatient specialty mental health services in 2008, 12% reported 25 or more visits; for inpatient care, 13% of users reported staying 25 or more nights (SAMHSA 2009). A child who requires this level of care will run up against service limits in seven state CHIP programs for outpatient services and four states for inpatient services. Further, while substance use disorders are less common than other mental health disorders among children, they commonly co-occur among adolescents with major depressive disorders (nearly 20%) (SAMHSA 2009). Thus, the more restrictive limits for substance use disorder services compared to mental health services may be a barrier for children with co-occurring conditions. Research also has shown that even very low cost sharing requirements (e.g., $5 or less) can deter children in low-income families from accessing care (Artiga and O’Malley 2005), as their budgets are already stretched beyond their means (Dinan 2009). A final possible barrier to access stems from the care management tools on which all states rely for behavioral health services under CHIP. Even if a benefit appears “unlimited” in terms of number of visits, a child must generally meet medical necessity requirements for care, is likely to have to navigate a process of prior authorization, and may face network limitations in choosing a provider. To our knowledge, there is no information summarizing how CHIP enrollees with behavioral health needs respond to aspects of benefit design such as cost sharing or benefit limits. We are currently collecting and analyzing data on children’s access to and utilization of behavioral health services under CHIP to quantify these potential access barriers and address a gap in the literature on this topic.

It is important to continue to monitor state benefit design as states adapt their programs to comply with federal parity requirements. Though most states already have some requirement for coverage of mental health services (whether it is that such services are provided at parity, provided at some level below parity, or simply offered to enrollees) (National Conference of State Legislatures 2010), federal parity requirements extend the scope of many existing state laws (National Alliance on Mental Illness 2009).3 Early evidence from states that made recent, parity-related changes to their CHIP programs indicates that parity could lead states with day/visit limits to eliminate these requirements, as this was the most common policy change cited in our sample. Less commonly, states eased day/visit limits to match those for medical/surgical health care (IA) or tightened medical/surgical health day/visit limits to match behavioral health services (PA). If other states follow this pattern, we can expect substantial changes to limits on behavioral health services. In contrast, parity’s affect on cost sharing requirements may be limited: only one state in our sample indicated that it had already or planned to alter cost sharing to adhere to parity rules (UT), and existing research shows that state cost sharing requirements for medical/surgical health services (Ross et al. 2009) typically already match the requirements we found for behavioral health services.

Another possible response to parity is change to behavioral health service delivery. Experience with parity requirements at the state level and in the Federal Employees Health Benefit Program (FEHBP) suggests that plans affected by parity regulations are likely to maintain coverage but contract with managed behavioral health organizations (MBHOs) to deliver services (Barry and Ridgely 2008; Busch and Barry 2008; Goldman et al. 2006). Most CHIP programs already rely on managed care to help administer behavioral health benefits while limiting costs, though many do not use specialized behavioral health plans. If states respond similarly to private payers faced with parity requirements, we may see an increase in the use of MBHOs under CHIP. Alternatively, parity may lead states currently using behavioral health carve outs to integrate behavioral and medical/surgical health services within a plan in order to streamline administration and comparability across services. Requirements in the interim federal regulations stipulating that deductibles and cumulative treatment limitations are combined for all services provide further incentive to integrate within a plan, as combined deductibles and limits pose administrative challenges to working with separate behavioral health and medical/surgical health plans.

A related potential outcome of parity is change to care management approaches. States and plans may look to these tools to control utilization given a broader scope of benefits. However, interim federal parity regulations propose that parity applies to both service limits/cost sharing and “non-quantitative treatment limits,” such as “medical management standards; prescription drug formulary design; standards for provider admission to participate in a network; determination of usual, customary, and reasonable amounts; requirements for using lower-cost therapies before the plan will cover more expensive therapies; and conditioning benefits on completion of a course of treatment” (Interim Final Rules 2010). Thus, it is possible that parity will actually lead to a loosening of care management tools.

Our work has some limitations that should be noted. First is that the ground-level implementation of behavioral health coverage under CHIP may differ from the delineation of policies on paper. For example, some states have mechanisms in place for hospital days or outpatient visits beyond the stated limit, if such care is determined to be medically necessary or children meet certain diagnostic criteria. Similarly, states commonly allow substitution of multiple partial hospitalization days for an inpatient day, allowing some beneficiaries to “stretch” benefits beyond limits. We do not have data on how often limits are waived or substituted to allow us to determine how binding service limits are. Second, there is variation on coverage within many state CHIP plans. Thus, service limits may apply only to certain populations within state programs. We do not have information on the distribution of enrollees within state programs that would enable us to see which limits are more commonly imposed. Third, we do not have state-by-state information on coverage of other types of services and thus are unable to compare policies for behavioral health to those for medical/surgical benefits. While such information would provide additional insight into the potential impact of parity requirements, it is beyond the scope of this analysis. Last, our data on care management approaches and other non-quantitative treatment limits is limited, as control over these tools is frequently devolved to individual health plans within state programs. This challenge in data collection suggests future challenges in drawing on such data to track and evaluate parity implementation.

Children’s Health Insurance Program served nearly 8 million low-income children in FY2009 (CMSb 2010b). For these children, access to behavioral health services depends on a broad range of facilitating factors, such as provider participation, geographic proximity to services, availability of culturally- and language-appropriate services, and the health insurance benefits available to them (Andersen 1995). From a provider perspective, comprehensive benefits are particularly important to compliance with treatment guidelines in behavioral health services. Recently enacted federal legislation requires parity in behavioral health benefits in state CHIP programs. This study highlights benefits gaps in a program that serves a high-need population and provides baseline data on states in which new parity regulations may have the greatest impact on generosity of behavioral health benefits.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant Nos. 1R01DA027414-01, K01DA019485, and 2K24DA019855).

Footnotes

Some of the data in this manuscript were included in a poster presentation at the June 2010 Academy Health Annual Research Meeting in Boston, MA.

Both Medicaid and CHIP eligibility vary by state. Income eligibility is determined based on a family’s income relative to the federal poverty level (FPL), which was $22,050 for a family of 4 in 2009. In 2009, the median income eligibility cutoff for Medicaid was 185% FPL for infants, 133% FPL for children up to age 6, and 100% FPL for children up to age 19. In 2009, the median income eligibility cutoff for CHIP was 235% FPL for all children up to age 19. Eligibility limits ranged from a low of 160% FPL in North Dakota to 400% FPL in New York. (Ross et al. 2009).

Federal parity requirements are effective for plan years starting on or after October 4, 2009, which in most cases begin on January 1, 2010. Specific regulations implementing MHPAEA, published on February 2, 2010, were effective April 5, 2010 and apply to plan years beginning on or after July 1, 2010. CHIPRA guidance indicates that the federal government will not withhold funding from states “if States make a good faith effort to comply with the requirements prior to the issuance of any regulations or guidance implementing the provisions in question.” For example, states that require state legislation to adhere to the new law will not be penalized if their legislative schedule did not permit such a law to be passed prior to the federal implementation date.

For example, only four states have “comprehensive parity laws” that require coverage a broad range of mental health conditions, including substance use disorder services, and 26 states’ laws cover only “serious mental illnesses.”

Contributor Information

Rachel L. Garfield, Email: rachelg@kff.org, Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 1330 G Street, NW, Washington, DC 20005, USA

William R. Beardslee, Baer Prevention Initiatives, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston, MA, USA. Gardner/Monks Professor of Child Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Shelly F. Greenfield, Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA. McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, USA

Ellen Meara, The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Lebanon, NH, USA. Faculty Research Fellow, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, USA.

References

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: Does it matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artiga S, O’Malley M. Increasing premiums and cost sharing in Medicaid and SCHIP: Recent state experiences. Washington, DC: Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured; 2005. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from http://www.kff.org/medicaid/7322.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- Azrin ST, et al. Impact of full mental health and substance abuse parity for children in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2):e452–e459. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL. The evolution of mental health parity. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2006;14(4):185–194. doi: 10.1080/10673220600883168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Busch SH. Do state parity laws reduce the financial burden on families of children with mental health care needs? Health Services Research. 2007;42(3):1061–1084. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00650.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, Ridgely MS. Mental health and substance abuse insurance parity for federal employees: How did health plans respond? Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2008;27(1):155–170. doi: 10.1002/pam.20311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brach C, et al. Who’s enrolled in the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP)? An overview of findings from the Child Health Insurance Research Initiative (CHIRI) Pediatrics. 2003;112(6):e499–e507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SH, Barry CL. New evidence on the effects of state mental health mandates. Inquiry. 2008;45(3):308–322. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_45.03.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SH, Barry CL. Does Private insurance adequately protect families of children with mental health disorders? Pediatrics. 2009;124(Suppl 4):S399–S406. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1255K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMS] Dear State Health Official Letter SHO-09-014. Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from http://www.cms.gov/SMDL/downloads/SHO110409.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMSa] The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act. Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2010a. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from https://www.cms.gov/healthinsreformforconsume/04_thementalhealthparityact.asp. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services [CMSb]. CHIP ever enrolled in a year. Baltimore, MD: CMS; 2010b. Retrieved June 10, 2010, from http://www.cms.gov/NationalCHIPPolicy/downloads/CHIPEverEnrolledYearGraph.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Costello E, Compton SN, Keeler G, Angold A. Relationships between poverty and psychopathology. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2023–2064. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.15.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinan KA. Budgeting for basic needs: A struggle for working families. New York: National Center for Children in Poverty; 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from http://www.nccp.org/publications/pub_858.html. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon K. Implementing mental health parity: The challenge for health plans. Health Affairs. 2009;28(3):663–665. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DL, et al. Depression and bipolar disorder. In: Evans DL, et al., editors. Treating and preventing adolescent mental health disorders: What we know and what we don’t know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. 3–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ganz ML, Tendulkar SA. Mental health care services for children with special health care needs and their family members: Prevalence and correlates of unmet needs. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):2138–2148. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman HH, et al. Behavioral health insurance parity for federal employees. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;354(13):1378–1386. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howell E. Access to children’s mental health services under Medicaid and SCHIP. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2004. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from www.urban.org/uploadedPDF/311053_B-60.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Interim Final Rules under the Paul Wellstone and Pete Domenici Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. Federal Register. 2010;75:5416–5417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine DD, Mechanic D. Utilization of specialty mental health care among persons with severe mental illness: The roles of demographics, need, insurance, and risk. Health Services Research. 2000;35(1 Part II):277–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Closing gaps in mental health care for persons with serious mental illness. Health Services Research. 2001;35(6):1009–1017. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Mental health services then and now. Health Affairs. 2007;26(6):1548–1550. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.6.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance on Mental Illness. State mental health parity laws. Arlington, VA: NAMI; 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from http://www.nami.org/Template.cfm?Section=Parity1&Template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=45313. [Google Scholar]

- National Conference of State Legislatures. State laws mandating or regulating mental health benefits. 2010 Retrieved August 18, 2010, from http://www.ncsl.org/default.aspx?tabid=14352.

- Rosenbach M, et al. Implementation of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program: Synthesis of state evaluations. Cambridge, MA: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc; 2003. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from: http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/redirect_pubsdb.asp?strSite=pdfs/impchildhlth.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum S, Sonosky C, Shaw K, Mauery DR. Behavioral health and managed care contracting under SCHIP (Policy Brief No. 5) Washington, DC: George Washington University Center for Health Services Research and Policy; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross DC, Jarlenski M, Artiga S, Marks C. A foundation for health reform: Findings of a 50 state survey of eligibility rules, enrollment and renewal procedures, and cost-sharing practices in Medicaid and CHIP for children and parents during 2009. Washington, DC: Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/8028.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Shern DL, Beronio KK, Harbin HT. After parity: What’s next? Health Affairs. 2009;28(3):660–662. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soni A. The five most costly children’s conditions, 2006:Estimates for the U.S. civilian noninstitutionalized children, ages 0–17 (Statistical Brief # 242) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2009. Retrieved August 18, 2010, from http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st242/stat242.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] Mental health and substance abuse services under the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. In: Designing Benefits and Estimating Costs (Center for Mental Health Services, DHHS Publication No. SMA 01-3473) Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAM-HSA] Results from the 2008 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings (Office of Applied Studies, NSDUH Series H-36, HHS Publication No. SMA 09-4434) Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- VanLandeghem K, Bonney J, Brach C, Kretz L. CHIRI™ Issue Brief No. 5 (AHRQ Pub. No. 06-0051) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. SCHIP enrollees with special health care needs and access to care. [Google Scholar]