Up to 5% of women who conceive are undergoing treatment with antidepressant agents.1 Concerns about possible adverse fetal effects lead many of those women to discontinue medication treatment. 2 Other women with recurrent depression stop antidepressant medication prior to conception to avoid any use of medication in pregnancy. However, patients and their doctors must also consider the risk of relapse into a new major depressive episode if they stop (or decide not to reinitiate) antidepressant medication.3 A recent prospective cohort study found that women with a history of recurrent major depressive episodes who stopped taking antidepressants in pregnancy or just before conception, had a five-fold increased risk of another episode as compared with women who continued medication. 4 While findings from this study have great clinical import, they have not been replicated. Moreover, specific requirements in that study for study participation and substantial recruitment from psychiatric settings may have led to selection of an “antidepressant-requiring” group.

We assessed onset of a major depressive episode in a cohort of women who were recruited from community and hospital-based prenatal care sites. The data were collected as part of a prospective cohort study designed to evaluate the possible association of major depressive episodes or antidepressant treatment in pregnancy with adverse birth outcomes. Detailed monthly data on major depressive symptoms and use of antidepressants allowed us to assess the relationship between the two. We hypothesized that among participants with a history of depressive episodes, those who continue antidepressants would have lower risk for onset of a major depressive episode in pregnancy and after delivery.

METHODS

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

To be enrolled in the study, women had to be at least 18 years of age and not yet completed their 17th week of pregnancy. Women were ineligible if they had a known multi-fetal pregnancy, had insulin-dependent diabetes, did not speak English or Spanish, did not have access to a telephone, had plans to relocate, or intended to terminate their pregnancy.

Recruitment and Assessment Procedures

We recruited women from 137 obstetrical practices and hospital-based clinics in Connecticut and western Massachusetts. Obstetrical providers or a project screener gave patients a form on which patients could indicate interest in participation. The form also included the estimated date of delivery. Providers faxed forms to the central data collection site where research staff obtained consent by phone and completed a screening interview. The structured screening questionnaire included questions about pregnancy dates, mood, psychotherapy, antidepressant use, medical conditions, and plans to relocate or terminate the pregnancy. The interviewer confirmed eligibility criteria and administered the gateway questions for a depressive disorder from the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview v2.1 (WMH-CIDI)5): (1) felt sad, empty or depressed; (2) felt discouraged or (3) lost interest in most things they enjoy for most of the day during any two-week interval in the current pregnancy. The screener also asked respondents about past episodes or treatment for a depressive disorder. We used these results to enrich the cohort with women who used antidepressants or were at risk of a major depressive episode. To do this, we offered participation to women who were undergoing antidepressant treatment or had a current or prior history of a depressive disorder. We randomly selected and invited participation from one of every three women who neither provided a positive response to screening questions for a depressive disorder nor reported treatment for a depressive disorder in the last five years.

We obtained written consent during a face-to-face interview before 17 completed weeks gestation. We re-interviewed participants by phone at 28 (± 2) weeks’ gestation (“monitoring” phone interview) and again at 8 (± 4) weeks postpartum (“postpartum” phone interview). Pregnancies in the cohort occurred between March of 2005 and May of 2009; follow-up continued until September 2009. Institutional Review Boards at Yale University School of Medicine and affiliated hospitals provided approval for the study.

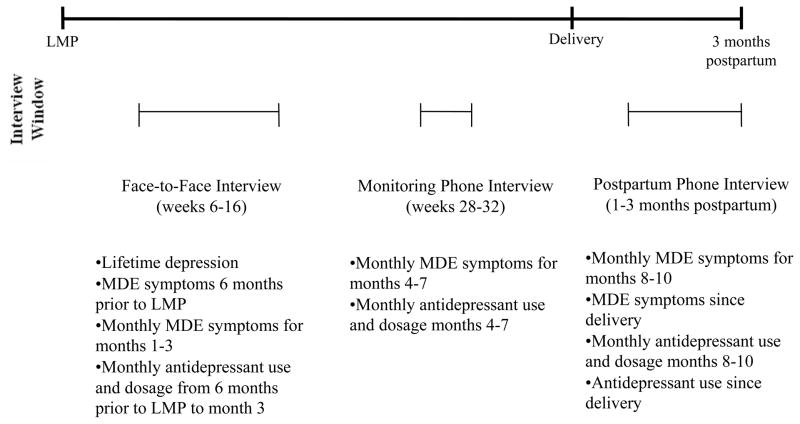

At each assessment point we administered the depressive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder modules of the WMH-CIDI, 5 to participants. The Composite International Diagnostic Interview is a valid and reliable, fully structured lay interview instrument,6 and has been administered to over 150,000 persons from 28 countries. Although the interview has not been specifically validated for use in pregnant women, such women have been well represented among those interviewed. In a validity study of a mixture of participants, the interview had high concordance with a semi-structured clinical psychiatric interview for 12-month period prevalence. 7 The area under the receiver operating curve between the semi- structured clinical interview and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview was between 0.8 to 0.9 for any depressive or anxiety disorder. The specificity for any depressive disorder in the prior 12 months was 97% (se=0.9) and the sensitivity was 69% (se=11.8). The Diagnostic Interview is similarly reliable when administered over the telephone.8 At the initial face-to-face interview we obtained a lifetime history of prior depressive disorder and the self-reported number of lifetime episodes by repeating the gateway questions outlined above. We asked greater detail for depressive episodes in the six months before and during pregnancy. The latter information included questions about all criteria for a major depressive episode according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for DSM-IV.9 At this interview, we asked women about symptoms in pregnancy months 1–3; at the monitoring phone interview we asked about symptoms in months 4–7; and at the postpartum phone interview we asked about symptoms during pregnancy months 8–10 and the first two months after delivery. We gave women specific dates to aid recall. We applied the algorithm for a major depressive episode from the Composite International Diagnostic Interview to determine, on a monthly basis, whether a participant was in an episode of illness. A diagram of the interview schedule and time period queried is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Study Assessments.

LMP indicates Last Menstrual Period; MDE indicates Major Depressive Episode

For information on antidepressant use or psychotherapy, we relied primarily on participant interviews. Interviewers collected information about antidepressant use for time periods corresponding to those for the depressive episodes. We asked participants to show us pill bottles, if available, at the home interview. We also showed participants pictures of various antidepressant pills in order to obtain more accurate information. While we attempted to collect records from outpatient behavioral health clinicians, many clinicians would not provide this information. Because of missing data, we deemed data from this source inadequate for analysis. Information about covariates, such as drug and alcohol use, race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status was also collected by interview.

Interviewers and Quality Control

Interviewers received a minimum of four days of didactic training followed by at least six practice interviews and a minimum of four supervised interviews before becoming eligible to conduct independent interviews. We audiotaped interviews with permission of participants. We randomly selected participants for quality-control assessment. For five percent of interviews, supervising staff subsequently called the participant and confirmed demographic and other information. For an additional five percent, the entire interview tape was reviewed for quality of data collection. Finally, all interviews were reviewed by second- and third-level coders. Any inconsistencies, unresolved questions, or missing information triggered review of the audiotape or a call-back to the participant. We used the same reliability procedures for phone interviews.

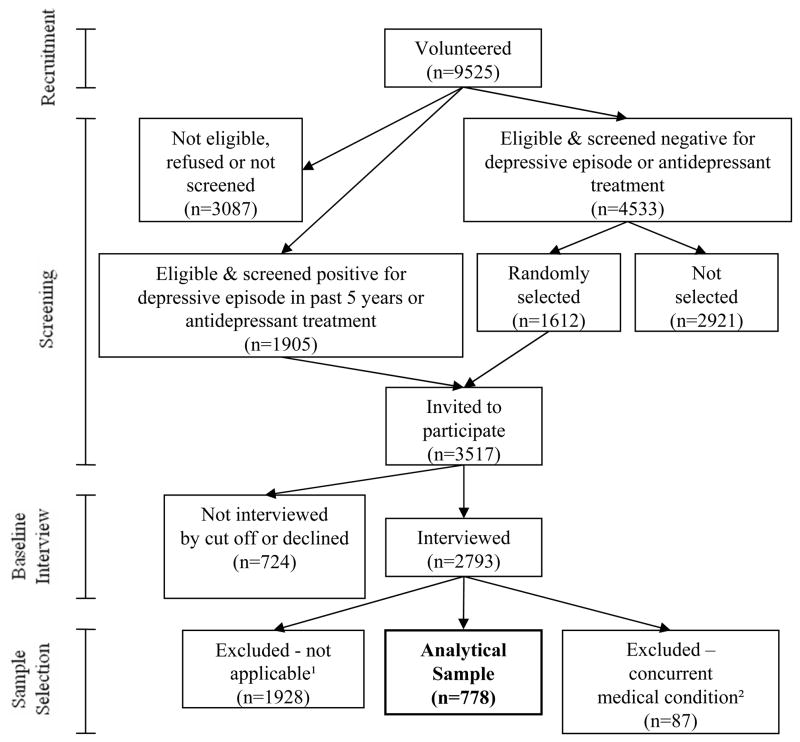

Study Recruitment and Analytic Group

Study recruitment is illustrated in Figure 2. We enrolled 9525 women, of whom 3087 (32%) were ineligible, declined to enroll, or were not screened. Another 1905 (20%) screened positive for a depressive episode in the last five years or were currently undergoing antidepressant treatment. The remaining 4533 women (48%) screened negative for a depressive episode or antidepressant treatment. We invited all women who screened positive to participate in the study, and we randomly selected 1612 (36%) of the women who screened negative to participate. Of these 3517 women, we interviewed 2793 (79%). We excluded 1928 of these women because they were not relevant for the analysis. These included participants who were already experiencing a major depressive episode in Month 1, and women with no history of a depressive disorder (who would have less reason to consider antidepressant use in pregnancy). In addition, we excluded participants with one of the following conditions that may appear similar to a major depressive episode and could have led to misclassification errors: (n=87): HIV (n=4), hypothyroidism (n=31), sickle cell anemia (n=4), pancreatitis (n=1), substance abuse (n=12), or alcohol abuse (n=7). Substance abuse was defined as use of an illegal drug 4 or more days per week in month 3 or later; alcohol abuse was use of alcohol 4 days or more per week or 5 or more drinks per occasion. Finally, we excluded participants who used antipsychotic (n=24) or anticonvulsant (n=19) agents that would indicate a history of bipolar or other psychotic disorder. Some participants in our sample met more than one exclusion criteria.

Figure 2. Study Recruitment and Selection of Analytic Sample.

1 major depressive episode in month 1 of pregnancy or no history of depression

2 Those who were excluded because of a concurrent medical condition had substance or alcohol abuse, hypothyroidism, sickle cell anemia, pancreatitis, human immunodeficiency virus, or use of an antipsychotic or anticonvulsant

The remaining group of 778 women constituted our analytic sample (Figure 2). Of this group, 21 women (3%) miscarried, 617 (79%) successfully completed both subsequent interviews, and 689 (89%) completed at least one of the two remaining interviews. When a monitoring phone interview was missed, we did not collect data for pregnancy months 4–7 and when a postpartum phone interview was missed we did not collect information for pregnancy months 9 and 10 and postpartum months 1 and 2.

Statistical Procedures

We used Cox regression to model risk for a major depressive episode. An event required full DSM IV criteria for at least two weeks. The risk period began in the second month of pregnancy and ended two months after delivery. Women with missing data for a major depressive episode were treated as censored. In a sensitivity analysis, we considered censorship to be an event. For each model, we used the exact method of computation to account for a large number of ties in times to event.

The primary exposure of interest was antidepressant treatment, a time-dependent variable. We examined models comparing treatment with onset of a major depressive episode during the corresponding months. We also created models for time-lagged antidepressant indicators of 1, 2 and 3 months to resolve issues of causal ordering. In the end, we chose a lag of 2 months, so as to relate risk of episodes with antidepressant use two months earlier. The longer lag was chosen to avoid artificially inflating the hazard for antidepressant users by including antidepressants taken following onset of a major depressive episode. Lags of 2 and 3 months produced similar hazard ratios for antidepressant use but a lag of 2 months was more sensitive to changes in use.

We pre-selected covariates that might confound the relationship between antidepressant use and onset of a major depressive episode. A history of prior depressive episodes (categorized as 1, 2, 3 or 4 or more lifetime episodes), illness onset before the age of 14, and psychiatric hospitalization are correlates of severe depressive illness.10 We included age, socioeconomic status and race/ethnicity in our adjusted models because perinatal depressive episodes may be higher in poor, ethnic-minority women11 and in adolescents.12 We included factors related to physical health: pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and binary indicators for doctor visits related to diabetes and hypertension in the 12 months before pregnancy. Finally, we included an indicator for a major depressive episode in the 6 months before pregnancy because women with more recent illness appear to have greater risk after medication discontinuation. 13 All two-way interactions between antidepressant use and other factors, including the antidepressant-time interaction, were not statistically significant. We asked about psychotherapy during pregnancy but only by trimester, making it difficult to model this factor to account for causal ordering.

For each covariate, we computed an unadjusted hazard ratio (HR) for a major depressive episode with the associated 95% confidence interval (CI). We also computed an adjusted HR that assessed the jointly modeled effects of each factor. Missing data were uncommon due to extensive data quality checks; age of initial depressive illness onset and BMI were the only predictors with missing values, and this was due to participant recall. Missing values for these factors were included as a separate category. Missing values for antidepressant use always corresponded to missed interviews and censored data. Analysis was performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Characteristics of the analytic sample are illustrated in Table 1. Over half of the cohort was between the ages of 25 and 34 years, well-educated, and white non-Hispanic. It was relatively rare to have had a depressive disorder onset before age 14 or to have been hospitalized for a depressive episode prior to pregnancy. A sizable minority of participants had a major depressive episode in the six months before pregnancy or 4 or more depressive episodes prior to pregnancy.

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population (N=778) Characteristic No. (%)

| Age (years) | |

| <25 | 115 (15) |

| 25–34 | 439 (56) |

| 35+ | 224 (29) |

| Mother’s Education (years) | |

| <12 | 38 (5) |

| 12–15 | 296 (38) |

| 16+ | 444 (57) |

| No. Previous live births | |

| 0 | 338 (43) |

| 1 | 279 (36) |

| 2+ | 161(21) |

| Married/cohabiting | 686 (88) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| White | 578 (74) |

| Black | 59 (7) |

| Hispanic/Other | 141 (18) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | |

| <19 | 26 (3) |

| 19–24 | 345 (44) |

| 25–29 | 227 (29) |

| 30+ | 166 (21) |

| Unknown height or weight | 14 (2) |

| Diabetes | 13 (2) |

| Hypertension | 32 (4) |

| Major depressive episode 6 months before pregnancy | 182 (23) |

| Age of first depressive episode (years) | |

| <14 | 99 (13) |

| 14–17 | 158 (20) |

| 18–25 | 290 (37) |

| 26+ | 226 (29) |

| Unknown | 5 (1) |

| Number of lifetime depressive episodes prior to pregnancy | |

| 1 | 206 (26) |

| 2 | 159 (20) |

| 3 | 115 (15) |

| 4+ | 298 (38) |

| Number of times hospitalized for depression prior to pregnancy | |

| Never | 684 (88) |

| 1 time | 55 (7) |

| 2–3 times | 28 (4) |

| 4+ times | 11 (1) |

Percents reflect missing data after trimester 1

Antidepressant Treatment and Psychiatric Illness

Antidepressant use decreased early in pregnancy. Twenty-one percent of participants took an antidepressant in the month before pregnancy, decreasing to 18% in Trimester 1, and to 14% in Trimesters 2 and 3. Use of antidepressants returned to 21% after pregnancy. One-hundred-twenty-three women (16%) developed a major depressive episode during pregnancy or postpartum. For those who became depressed, most had onset in the first trimester (n=93; 76%). Regarding other psychiatric disorders during pregnancy, 5% of the cohort met criteria for PTSD 15% for generalized anxiety disorder, and 6% for panic disorder. Eight percent of the sample had more than one of these conditions during pregnancy.

Onset of a Major Depressive Episode

Table 2 provides hazard ratios for onset of a major depressive episode associated with various demographic and clinical factors. There was little evidence of an association between antidepressant use and reduced occurrence of depression (unadjusted HR= 0.85 [95% CI= 0.52—1.40]); adjusted HR= 0.88 [0.51—1.50]). A major depressive episode in the 6 months before pregnancy and a history of 4 or more prior depressive episodes were risk factors for a major depressive episode. A depressive episode before age 14 or unknown age of onset appeared to be associated with increased risk, although adjustments substantially reduced those associations. Black and Hispanic women also appeared to be at increased risk compared with white women. These clinical and racial ethnic associations were consistent in unadjusted and adjusted models that accounted for antidepressant use.

Table 2.

Hazard Ratios of a Major Depressive Episode for Antidepressant Use and Other Potential Risk Factors

| Factor | Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CIa | |

| Antidepressant Use | 0.85 | (0.52 1.40) | 0.88 | (0.51 1.50) |

| Major depressive episode 6 months before pregnancy | 2.91 | (2.02 4.18) | 1.84 | (1.23 2.75) |

| Number of lifetime depressive episodes prior to pregnancy | ||||

| 1b | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2 | 0.97 | (0.48 1.93) | 0.83 | (0.41 1.71) |

| 3 | 1.22 | (0.60 2.47) | 1.05 | (0.50 2.20) |

| 4+ | 2.92 | (1.76 4.84) | 1.97 | (1.09 3.57) |

| Age of first depressive episode | ||||

| <14 | 3.24 | (1.92 5.46) | 1.57 | (0.82 3.01) |

| 14–17 | 1.49 | (0.86 2.56) | 0.85 | (0.45 1.62) |

| 18–25 | 0.99 | (0.59 1.66) | 0.79 | (0.45 1.38) |

| 26+b | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unknown | 6.28 | (1.90 20.80) | 4.61 | (1.26 16.94) |

| Number of times hospitalized for depression prior to pregnancy | ||||

| 0b | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 1.59 | (0.88 2.90) | 0.89 | (0.48 1.66) |

| 2–3 | 0.71 | (0.23 2.25) | 0.51 | (0.15 1.73) |

| 4+ | 1.89 | (0.60 5.96) | 0.98 | (0.30 3.26) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Whiteb | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 4.39 | (2.67 7.22) | 3.69 | (2.16 6.30) |

| Hispanic/other | 2.78 | (1.85 4.18) | 2.33 | (1.47 3.69) |

| Age | ||||

| <25 | 2.31 | (1.52 3.53) | 1.46 | (0.84 2.52) |

| 26–34b | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 35+ | 0.70 | (0.43 1.12) | 0.77 | (0.46 1.29) |

| Mother’s education (years) | ||||

| <12 | 3.23 | (1.73 6.04) | 1.00 | (0.46 2.18) |

| 12–15 | 1.61 | (1.10 2.35) | 0.83 | (0.52 1.32) |

| 16+b | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | ||||

| <19 | 0.87 | (0.27, 2.79) | 0.74 | (0.22, 2.47) |

| 19–24b | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 25–29 | 1.27 | (0.83 1.95) | 1.11 | (0.71 1.74) |

| 30+ | 1.36 | (0.86 2.17) | 1.04 | (0.63 1.73) |

| Unknown height or weight | 1.04 | (0.25 4.29) | 0.93 | (0.22 4.00) |

| Diabetes | 2.17 | (0.80 5.88) | 2.58 | (0.84 7.95) |

| Hypertension | 0.85 | (0.31 2.30) | 1.05 | (0.37 2.95) |

All factors in the adjusted model are shown in the table

We performed a sensitivity analysis to estimate the potential effect of attrition on hazard ratio estimates for antidepressant use. When we assumed that all women lost to follow up experienced a major depressive episode, the estimated hazard ratio for antidepressant use remained neutral (HR=1.00 [95% CI= 0.69—1.45]), reflecting similar attrition between antidepressant users and nonusers.

The mean dose of antidepressants taken by participants is shown in Table 3. Of women who took antidepressants during the study period, 112 took one type, 16 took two types and 2 took three types. These medications were not necessarily taken concurrently. In general, average monthly doses were consistent with the manufacturer’s recommended treatment guidelines. For the most common drugs (those with at least ten users), 71%-90% of the monthly use met recommended levels.

Table 3.

Types and Doses of Antidepressants Used by Study Participants

| Drug | # of Users | Average Dose (mg/day) Mean (SD) | % Months at Minimum Recommended Dose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Citalopram | 10 | 23 (15) | 86 |

| Fluoxetine | 25 | 24 (15) | 90 |

| Lexapro | 22 | 11 (6) | 71 |

| Paroxetine | 6 | 23 (11) | 69 |

| Paroxetine-CR | 1 | 7 (8) | 0 |

| Sertraline | 48 | 68 (34) | 81 |

| Duloxetine | 4 | 44 (20) | 80 |

| Venlafaxine | 11 | 87 (49) | 80 |

| Nortryptiline | 1 | 18 (−) | 0 |

| Bupropion | 22 | 217 (112) | 88 |

Note: 112 women were using 1 antidepressant, 16 women were using 2 antidepressants and 2 women were using 3 antidepressants

DISCUSSION

In this prospective study of pregnant women with recurrent depressive illness who were followed through pregnancy and postnatally, risk for onset of a major depressive episode was similar whether or not women took antidepressant medications. Controlling for antidepressant use, the highest risks of a major depressive episode were in women with an episode in the 6 months before conception, among women with 4 or more depressive episodes prior to pregnancy, and among Black or Hispanic women. Unknown or young age at first depressive episode were also possible risk factors.

Our findings differ from a retrospective study14 and another prospective cohort study.4 In the only previously published prospective study, Cohen and colleagues4 found a markedly increased risk of a major depressive episode among participants who discontinued medication (HR=5.0 [95% CI=2.8—9.1]). In our study the hazard ratio for antidepressant users compared with nonusers was 0.88 (95% CI=0.51—1.5). These differences may be due to differences between the two study populations. Many subjects from the Cohen study4 were recruited from psychiatric treatment centers and had characteristics suggestive of severe depressive illness. In that study, 43% of participants developed a major depressive episode during the observation period and 53% suffered from a concurrent psychiatric condition. In our study, only 16% had the onset of a major depressive episode and 8% had another psychiatric disorder. The two cohorts also differed in the percentage of women who had a depressive episode before age 14 (23% in Cohen4 and 13% in our group). Of the women in our cohort who had 4 or more depressive episodes prior to pregnancy, 26% experienced a depressive episode, similar to that of the Cohen cohort.4

Differences in the study populations may not entirely account for the disparate findings. Cohen et al. used the clinician-administered Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV15 rather than the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). It is possible that our use of lay interviewers led to under-detection of depressive episodes, although interviews were taped and checked by secondary coders. Recall bias may have been an issue in our study as we had several months rather than a single month between assessments. If there were under-detection or recall bias, this may have diminished estimated group differences through non-differential misclassification bias. Other limitations of our study included our reliance on self-report rather than blood tests to document antidepressant use; participants may have under-reported their use of medication. Additionally, given our data-collection methods, we had limited ability to account for the effect of psychotherapy.

Our study was observational and cannot attribute causality. Of particular concern is the issue of confounding by indication. It is likely that women who chose to continue antidepressant treatment had a higher risk for a major depressive episode. We attempted to account for this bias by including measures of depressive disorder prior to pregnancy in the analysis. However, unobserved or unquantifiable differences beyond these factors may have remained. A clinical trial that randomly assigns treatment condition to pregnant women would better control this type of bias, but many would find such as design ethically objectionable.

Synthesizing our findings with that of Cohen and colleagues,4 it is possible that some women are able to discontinue medication in pregnancy without a relapse, while others are not. Numerous parameters may indicate greater illness severity and hence risk for a major depressive episode. We found that 4 or more pre-pregnancy illness episodes and an episode of illness within the 6 months prior to conception were the strongest predictors. These characteristics may be less common among women typically attending prenatal care, from which we recruited the majority of our subjects. While racial and ethnic minority women had elevated risk, it is not clear whether other psychosocial or environmental factors might better explain the association. This deserves further exploration.

In summary, the present cohort provides data on a large group of women with a history of a depressive episode or recent antidepressant treatment who were prospectively followed through pregnancy and into the postpartum period. Our data provide no evidence that failure to use antidepressants increased the risk for onset of a depressive episode in pregnancy. This could be reassuring to women who wish to discontinue treatment in pregnancy. However, our findings are limited by the possibility that women who most strongly required antidepressant treatment are the ones who continued therapy in pregnancy. Clinicians and patients should consider the women’s psychiatric history, since this appears to greatly contribute to outcomes. Patients and their physicians should carefully discuss the risks and benefits of antidepressant treatment in pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Source of Funding: This study was supported by a grant awarded to Dr. Yonkers by the National Institute of Child Health and Development (5-R01-HD045735) entitled “Effects of Perinatal Depression on PTD and LBW”.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: Kimberly A. Yonkers is the lead author and disclose royalties from Up To Date, support for an investigator initiated study from Eli Lilly and study medication for an NIMH trial from Pfizer. Dr. Burkman acknowledges consultation to the Veritech corporation. Remaining authors have no disclosures.

References

- 1.Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Brown J, Lane K, Livingston J, Boudreau D, Rolnick SJ, Roblin D, Smith DH, Willy ME, Staffa JA, Platt R. Use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy: a multisite study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008;198(2):194.e1–194.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einarson A, Selby P, Koren G. Abrupt discontinuation of psychotropic drugs during pregnancy: fear of teratogenic risk and impact of counselling. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2001;26(1):44–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery SA, Dufour H, Brion S, et al. The prophlactic efficacy of fluoxetine in unipolar depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;134 (suppl 3):69–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen L, Altshuler L, Harlow B, Nonacs R, Newport D, Viguera A, Suri R, Burt V, Hendrick V, Reminick A, Loughead A, Vitonis A, Stowe Z. Relapse of major depressive during pregnancy in women who maintain or discontinue antidepressant treatment. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:499–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.5.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI, Version 2.1). Version 2.1. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wittchen H-U. Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1994;28:57–84. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haro JM, Arbabzadeh-Bouchez S, Brugha TS, De Girolamo G, Guyer ME, Jin R, Lepine JP, Mazzi F, Reneses B, Vilagut G, Sampson NA, Kessler RC. Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2006;15(4):167–180. doi: 10.1002/mpr.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Heeringa S, Merikangas KR, Pennell B-E, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM. National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent supplement (NCS-A): II. Overview and design Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009;48(4):380–5. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181999705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-DSM-IV. 4. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rush AJ, Golden WE, Hall GW, Herrera CM, Houston A, Kathol RG, Katon W, Matchett CL, Petty F, Schulberg HC, Smith GR, Stuart GW. Clinical Practice Guideline. 5. Vol. 1. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care and Policy Research; 1993. Depression in Primary Care: Vol. 1. Detection and Diagnosis. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hobfoll SE, Ritter C, Lavin J, Hulsizer MR, Cameron RP. Depression prevalence and incidence among inner-city pregnant and postpartum women. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63(3):445–53. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Troutman BR, Cutrona CE. Nonpsychotic postpartum depression among adolescent mothers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1990;99(1):69–78. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yonkers K, Wisner K, Stewart D, Oberlander T, Dell D, Stotland N, Ramin S, Chaudron L, Lockwood C. The management of depression during pregnancy: a report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen L, Altshuler L, Stowe Z, Faraone S. Reintroduction of antidepressant therapy across pregnancy in women who previously discontinued treatment. A preliminary retrospective study. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics. 2004;73(4):255–8. doi: 10.1159/000077745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders-Patient Edition. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, Biometrics Research Department; 1994. [Google Scholar]