Abstract

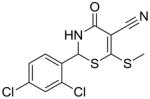

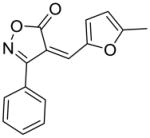

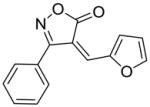

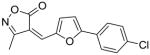

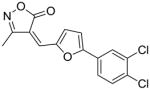

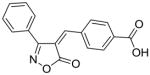

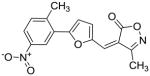

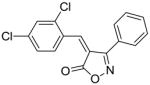

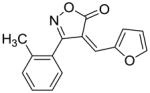

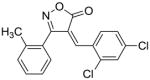

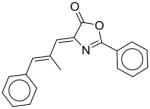

The biosyntheses of isoprenoids is essential for the survival in all living organisms, and requires one of the two biochemical pathways: (a) Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway or (b) Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway. The latter pathway, which is used by all Gram-negative bacteria, some Gram-positive bacteria and a few apicomplexan protozoa, provides an attractive target for the development of new antimicrobials because of its absence in humans. In this report, we describe two different approaches that we used to identify novel small molecule inhibitors of Escherichia coli and Yersinia pestis 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl D-erythritol (CDP-ME) kinases, key enzymes of the MEP pathway encoded by the E. coli ispE and Y. pestis ipk genes, respectively. In the first approach, we explored existing inhibitors of the GHMP kinases while in the second approach; we performed computational high-throughput screening of compound libraries by targeting the CDP-ME binding site of the two bacterial enzymes. From the first approach, we identified two compounds with 6-(benzylthio)-2-(2-hydroxyphenyl)-4-oxo-3,4-dihydro-2H-1,3-thiazine-5-carbonitrile and (Z)-3-methyl-4-((5-phenylfuran-2-yl)methylene)isoxazol-5(4H)-one scaffolds which inhibited Escherichia coli CDP-ME kinase in vitro. We then performed substructure search and docking experiments based on these two scaffolds and identified twenty three analogs for structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies. Three new compounds from the isoxazol-5(4H)-one series have shown inhibitory activities against E. coli and Y. pestis CDP-ME kinases with the IC50 values ranging from 7μM to 13μM. The second approach by computational high-throughput screening (HTS) of two million drug-like compounds yielded two compounds with benzenesulfonamide and acetamide moieties which, at a concentration of 20μM, inhibited 80% and 65%, respectively, of control CDP-ME kinase activity.

Introduction

In different regions of the globe, infectious diseases continue to inflict heavy toll on mankind every year. According to the statistics provided by the World Health Organization, malaria and tuberculosis have killed more than 2.7 million people worldwide in 2011; among which many of them were children (http://www.who.int/topics/millennium_development_goals/diseases/en/index.html). To make matters worse, multiple drug-resistant strains of deadly microbes are on the rise.

When compared developing nations, developed countries have a lesser share of morbidity and mortality caused by widespread microbial infections. Yet, the number of citizens of the developed nations exposed to deadly microbial infections is poised to increase due to rapid globalization. Additionally, as the population ages and the number of chronically-sick patients swell, nosocomial and opportunistic infections will rise, as will the incidents related to antibiotics resistance. Currently, more than half of all nosocomial infections are caused by Gram-negative bacteria [1]. The increasing threat of bioterrorism also justifies the urgent need for new antimicrobials directed against unexplored targets.

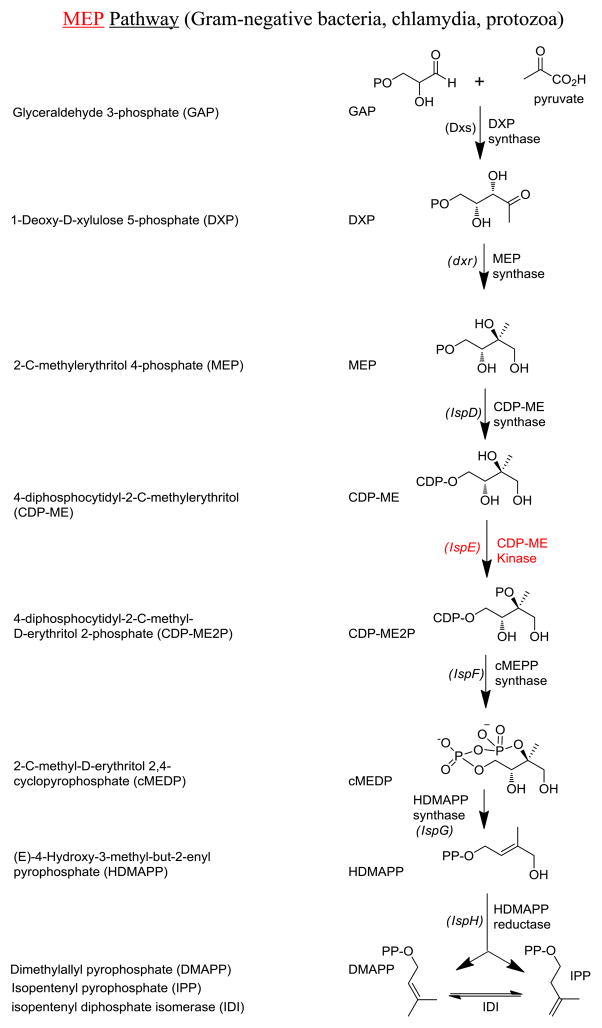

In all living organisms, the biosyntheses of isoprenoids, one of the most functionally diverse classes of naturally occurring molecules, require one of the two biochemical pathways: (a) Mevalonate (MVA) Pathway [2–4] or (b) Methylerythritol Phosphate (MEP) Pathway [5–9] (Fig. 1). The former pathway is utilized by Archaea, Fungi, Eukaryea, and most Gram-positive bacteria, while the latter is used by all Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., Escherichia coli), some Gram-positive bacteria (e.g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis), Chlamydia, a few apicocomplexan protozoa (e.g., Plasmodium sp.), and all plants [5–9]. Disruptions of genes encoding the enzymes of either biosynthetic pathway are lethal to the microbes [10–12]. The absence of the MEP pathway in humans renders the associated enzymes unique and useful targets for the development of novel antimicrobials, as therapeutics against these enzymes are less likely to cause serious side-effects in the patients [10, 13]. Moreover, recent functional and structural characterization of almost every step of the pathway has set the stage for structure-based design of novel small molecule inhibitors for the enzymes of the MEP pathway. Yet, there has been only one published attempt on high-throughput screenings (HTS) for small molecule inhibitors for 2-methylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (IspF) [14]. In this report, we describe the identification of novel small molecule inhibitors of E. coli and Yersinia pestis 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol (CDP-ME) kinases, key enzymes of the MEP pathway encoded by the E. coli ispE and Y. pestis ipk genes, respectively.

Fig. 1.

MEP Isoprenoid biosynthetic pathways in living cells

Materials and Methods

Cloning, over-expression and purification of recombinant E. coli and Y. pestis CDP-ME kinases

The genes encoding the bacterial CDP-ME kinases were PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA harvested from E. coli strain DH5α and Y. pestis strain KIM6 using oligonucleotide primers containing the histidine hexamer (His6) sequence at the 5′ end. The PCR products were sub-cloned into the bacterial expression vector pET15b (Novagen). Sequences of the PCR inserts were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Induction of enzyme production was achieved by adding isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at a final concentration of 1mM to the bacterial cell culture upon reaching OD600 = 0.6 at 37°C. Induction took place from 3 hours to overnight at room temperature. Bacterial cells were then harvested by centrifugation and the pellet was subsequently stored at −80°C. Protein purification was conducted at 4°C throughout. Briefly, cell pellets were re-suspended in lysis buffer (50mM NaH2PO4, 300mM NaCl, 10mM imidazole, pH 8.0). Cells were then lysed using a microfluidizer and clarified by centrifugation, and the lysate was loaded onto a chromatography column containing Nickel affinity resin. The resin was washed with buffer mentioned above but with 20mM imidazole added, and the bound CDP-ME kinase was eluted using an imidazole concentration gradient.

Enzymatic activity assay for bacterial CDP-ME kinases

Two methods were used to assay for bacterial CDP-ME kinase activity: (1) Kinase Glo™ (Promega) luminescence-based reaction for ATP-depletion, and (2) the standard pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase-coupled absorbance-based assay for ADP-production [15]. Both assay were used in our previous studies of the human galactokinase (GALK1) [16, 17].

For the Kinase Glo™ assay, CDP-ME kinase activity was typically measured by incubating 0.15μg purified CDP-ME kinase with 5mM MgCl2, 60mM NaCl, 20mM HEPES, 1mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.5% DMSO, 0.01% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 200μM CDP-ME (Echelon), and 40μM ATP in a total volume of 60μl. After 30 minutes at room temperature (22°C), 30μl of Kinase Glo™ was added, and luminescence was measured 5 minutes later using a Synergy HT Plate Reader (Bio Tek).

For the pyruvate kinase/lactate dehydrogenase-coupled assay, assay conditions were similar to what was mentioned above in the Kinase Glo™ assay, except the following additional reagents were added: 500μM of phosphoenolpyruvate, 1mM NADH, 1.5unit of pyruvate kinase and 1.8unit of lactate dehydrogenase (Sigma-Aldrich). NADH consumption was monitored by the Synergy HT Plate Reader (Bio Tek) at 340nm for 30 minutes at room temperature. The reaction rate was calculated from the initial linear portion of the curve.

To determine the IC50 of selected inhibitors, a standard curve was set up for both assays by using varying the amount of enzyme in the mixture to determine the percent of inhibition as previously described [16, 17]. The final kinetic parameters and IC50 values of inhibitors were calculated from the results of both assays (in triplicates) using nonlinear regression analysis (SigmaPlot V8).

Computational screening for E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors

Computational screening was performed on ~6 million pre-filtered drug-like compound sets from 26 commercial vendors using ICM and QikProp programs [18, 19]. The duplicate structures were removed from the databases of the individual suppliers, and the sets obtained were combined to give a collection of 2 million unique, diverse structures. Next, the selection of drug- and lead-like compounds was based on the properties cut-off values (MW <500, cLogP < 4.5, HBA <8, HBD <5, rotating bonds <6, PSA < 140, CaCO-2 >500, LogS < -5). Removal of both toxic and reactive groups was based according to Lipinski and Veber criteria [20, 21].

Reference protein coordinates used for structure-based virtual screening were taken from the X-ray structure of the ternary complex structure of E. coli CDP-ME kinase co-crystallized with CDP-ME and AMP-PNP (PDB: 1OJ4) [22]. The CDP-ME binding pocket (considered as “CDP-ME allosteric site”) was used in all computational experiments throughout. In preparation for ICM docking, water molecules were removed and the missing bond orders and geometries were edited. Ionizable groups in the protein structures were converted into the protonated states appropriate at neutral pH, and the ICM default partial atomic charges were set up. Hydrogen atoms were added and the combined complex structure was submitted for protein preparation and energy minimization calculation. The active site for a protein was defined as being within 5Å of CDP-ME in the X-ray co-crystallized structure. Energy grids representing the active site (van der Waals, hydrogen bonding, electrostatics, and hydrophobic interactions) were calculated with 0.5Å grid spacing, and docking experiments were performed using the defined CDP-ME binding pocket with the application of our docking workflow.

Purchase of small molecule compounds

Small molecule compounds 8, 15, 16, 32, 33 were purchased from Maybridge (Trevillett, UK). Compounds 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 20, 29, 30, 34, 39 were obtained from ChemDiv (San Diego, CA). Compounds 17, 18, 23 were procured from ChemBridge (San Diego, CA). Compounds 19, 22, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 35, 36, 37, 38, 40 were supplied by TimTec (Newark, DE). Compounds 21 and 31 were purchased from Asinex (Moscow, Russia) and Enamine (Kiev, Ukraine), respectively. Purity of compounds prepared by these companies is typically above 95%. All analogs derived from compound 1 were tested as racemic mixtures.

Bacterial growth inhibition assay

E.coli DH5α was cultured in LB medium at 37°C to reach Optical Density (O.D.) at 600nm = 0.1. Selected compounds at defined concentrations were added to the culture and bacterial growth was monitored for the next 20 hours by recording changes in O.D..

Results & Discussion

Early successes in treating bacterial infections with antibiotics had once led some to believe that infectious diseases were on the brink of elimination. This was, of course, before the recognition of antibiotics resistance as a persistent, growing threat for mankind [10, 23–25]. Yet, for decades, antimicrobial research has been focusing on the traditional biosynthetic steps of the bacterial cell wall, protein synthesis, and topoisomerases. At a time when there is an urgent need for new antimicrobial agents against resistant organisms, some suggested that it might be useful to identify new structural classes heretofore not observed [26]. Despite attempts to design specific CDP-ME kinase inhibitors by synthesizing derivatives of cytidine/cytosine [27–29], there has been no documented experimental, random HTS of inhibitors for E. coli or other bacterial CDP-ME kinases. Although these proof-of-principle approaches are valid, the identified inhibitors shared closely similar chemotypes and in some cases, IC50 values of mM (millimolar) range [27]. In this study, we took two different approaches to expand the repertoire and diversity of the bacterial CDP-ME kinase inhibitors. In the first approach, we tested existing small-molecule inhibitors of GHMP (Galactose, Homoserine, Mevalonate, Phosphomevalonate) kinases [30, 31], the family of kinases in which CDP-ME kinase belongs, for any cross-inhibition of E. coli CDP-ME kinase. In the second approach, we performed computational HTS of compound libraries for E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors by targeting the CDP-ME binding site.

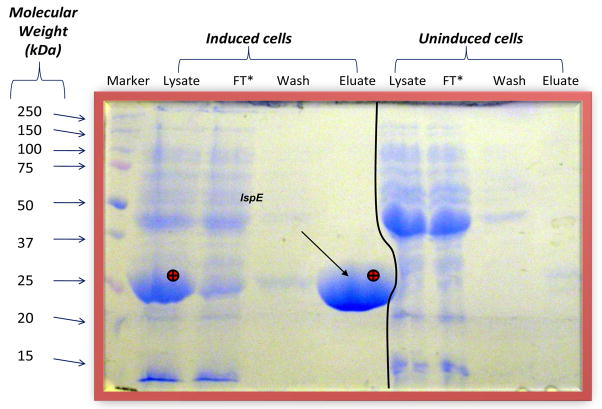

Biochemical characterization of purified recombinant E. coli CDP-ME kinase

To identify E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors from known GHMP kinase inhibitors, we must first purify sufficient E. coli CDP-ME kinase and establish the biochemical assays for its activity. As shown in Fig. 2, we were capable of purifying large amount of active E. coli CDP-ME kinase. We subsequently determined the KM for CDP-ME and ATP for the recombinant enzyme as 200μM and 20μM, respectively (data not shown). Our biochemical data correlated well with the data published by Rohdich and coworkers [32], as well as those of another recombinant bacterial CDP-ME kinase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis reported by Eoh and coworkers [33]. Therefore, His6 epitope tag did not appear to affect the overall folding of the E. coli enzyme and its function.

Fig. 2.

Purification of E. coli CDP-ME kinase. Over-expression of E. coli CDP-ME kinase was induced in E. coli HMS174 cells harboring the plasmid expressing the E. coli IspE gene. The overproduced CDP-ME kinase seen in the lysate of the bacteria (marked by ⊕ in lane 2) was purified by Nickel affinity chromatography and collected in the eluate (also marked by ⊕). FT: Flow-through.

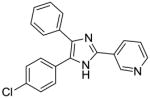

Spectrum of GHMP kinase inhibitors

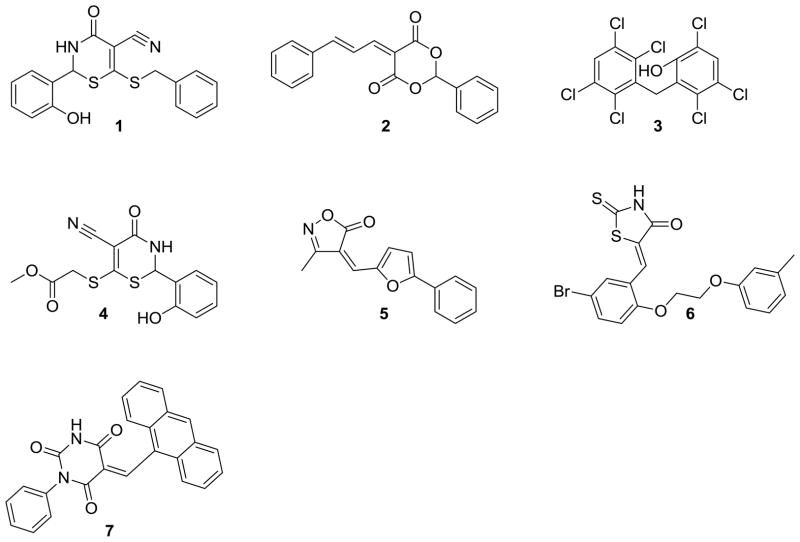

Previously, we identified over 150 small molecule inhibitors of the human enzyme galactokinase (GALK1), a member of the GHMP kinase family to which E. coli CDP-ME kinase belongs, through HTS of 50,000 small molecule compounds [16, 17]. We selected 34 of the 150 compounds for further characterization, including selectivity against other GHMP kinases such as E. coli CDP-ME kinase in vitro [16]. We found that 17 out of 24 (71%) of tested GALK1 inhibitors show no cross-inhibition towards CDP-ME kinase at concentrations of 10-fold or higher than the corresponding IC50 determined for GALK1 [16]. For the seven GALK1 inhibitors that cross-inhibited E. coli CDP-ME kinase, three compounds 2, 5, 7 (Fig. 3) showed a higher efficacy (i.e., lower IC50) towards E. coli CDP-ME kinase [16]. Such degree of cross-inhibition is not totally unexpected within GHMP kinase family [30, 31], as the three very conserved motifs that define this kinase family participate substrates binding [30, 31, 34–37], and the substrate binding sites are often the binding pockets of the inhibitors [16]. Nevertheless, our study confirmed that selectivity among different GHMP kinase inhibitors do exist since more than 70% of all GALK1 inhibitors did not cross-inhibit E coli CDP-ME kinase [16].

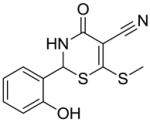

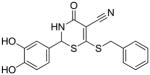

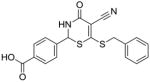

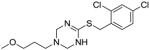

Fig. 3.

Small molecule compounds with dual human GALK1 and E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitory properties.

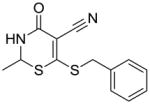

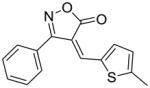

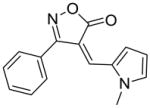

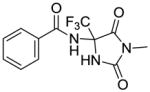

Structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies of novel chemotypes of E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors

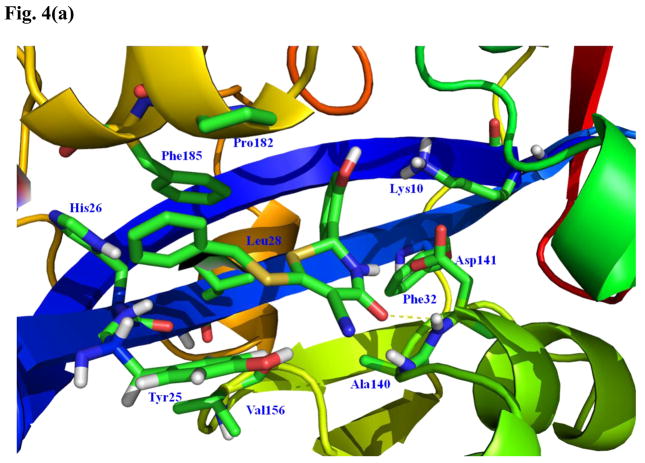

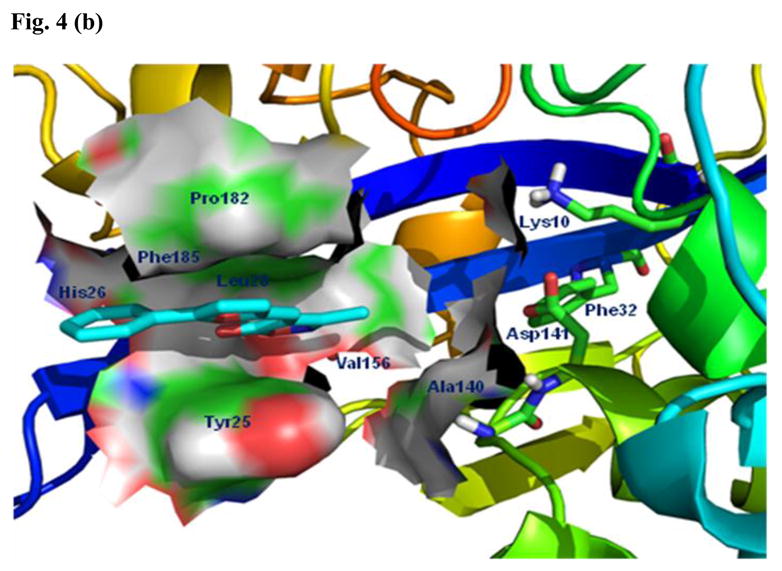

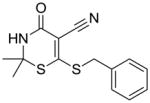

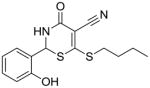

The seven GALK1 inhibitors that cross-inhibited E. coli CDP-ME kinase are shown in Fig. 3. Of those, we chose compounds 1 (IC50 for E. coli CDP-ME kinase = 18μM) and 5 (IC50 for E. coli CDP-ME kinase = 5.5μM) (Fig. 3) [16] for further SAR studies. These compounds were chosen because their predicted binding modes revealed that the 6-benzylthio and 5-phenylfuran ring moieties are involved in strong ππ interaction within the cytidine binding pocket of CDP-ME created by three critical residues - Tyr25, His26, and Phe185. In addition, binding of compound 1 showed that its central core dihydro-2H-1,3-thiazine-5-carbonitrile –C=O mimics the α–, β-phosphates of substrate CDP-ME and participates in H-bonding interaction with Asp141 –NH…O-, whereas the 2-hydroxy-aryl ring of compound 1 positioned towards the binding site of the D-erythritol moiety of CDP-ME (Fig. 4a). Moreover, using the formula: ΔGbind;solv = ΔGbind;vacuum + ΔGcomplex;solv (ΔGprotein;solv + ΔGligand;solv), we determined the binding energies of these two compounds as −23.49 and −21.26 kcal/mol, respectively. These data agreed with the inhibition data. The presence of desirable cytidine-binding pharmacophore groups, solubility, permeability and Lipinski-like criteria supported the selection of these compounds for further SAR studies. At the first glance, however, one might query if the selected compounds are Michael acceptors and if so, they will not be suitable compounds to pursue in the future. However, upon closer look, one will realize that this should not be a concern. For example, compound 1 and its thiazine-5-carbonitrile core can be optimized by the introduction of endocyclic double bond, leading to the more stable conformer where the secondary –NH is changed to tertiary –N atom. In addition, the presence of strong electron-withdrawing group(s) is needed to enhance the reactivity of a typical Michael acceptor. If one looks at compound 1 closely, one will realize that the α,β-unsaturated lactam in the thiazione core adjacent to two alkylated thiol groups will increase the electron density on this double bond through a positive inductive effect. This will overcome the propensity of this double bond to be involved in a potential Michael addition. Similarly, the α,β-unsaturated double bond of the isoxazole core of compound 5 is conjugated to series of double bonds in the furan and the aromatic rings. For this reason, this double bond is very stable and will lack reactivity towards Michael addition.

Fig. 4.

Predicted binding modes of compounds 1 and 5. (a) The predicted binding mode based on docking experiments of compound 1 in complex with E. coli CDP-ME kinase shown is color-by-atom structures. The active site of cytidine pocket is depicted in stick representation. The dotted line represents a hydrogen bonding interaction with thiazine-5-carbonitrile –C=O…HN- Asp141. (b) The isoxazol-5(4H)-one containing scaffold with compound 5 in complex with E. coli CDP-ME kinase.

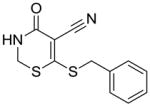

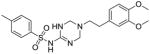

Substructure search and additional docking experiments resulted in the selection of nine analogs for lead compound 1 (compounds 8–16, Table 1) and 14 analogs for compound 5 (compounds 17 – 30, Table 1) for SAR studies. These sets of compounds were screened for their ability to inhibit purified E. coli CDP-ME kinase and the results were shown in Table 1. Both compounds 8 and 13 possess 6-(methylthio) and 6-(butylthio) group, respectively, at the 6th position, but lack the extended aryl ring which is critical for ππ stacking interactions with Phe185 and Tyr25 residues (Table 1). Thus, we were surprised to see the similar inhibitory activity of these compounds to that of compound 1. Nevertheless, these two compounds retained the critical Asp141 –NH…O- H-bonding interaction similar to that of the compound 1, high-lighting the importance of such interaction. Perhaps the conformational rigidity and stable binding mode are more important criteria that need to be considered for future optimization and improvement of these series of compounds.

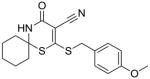

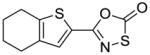

Table 1.

Hit Expansion & SAR Studies of Chemotypes 1 & 5

| Compound | % inhibition at 20μM |

|---|---|

8 |

60 |

9 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

11 |

50 |

12 |

50 |

13 |

50 |

14 |

40 |

15 |

50 |

16 |

50 |

17 |

40 |

18 |

50 |

19 |

60 |

20 |

80 |

21 |

90 |

22 |

80 |

23 |

65 |

24 |

80 |

25 |

50 |

26 |

60 |

27 |

45 |

28 |

50 |

29 |

45 |

30 |

55 |

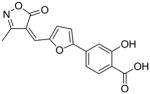

Although the introduction of 2-aryl carboxylic acid in compound 10 (Table 1) exhibited weak ionic interactions with Lys10, it did not improve the CDP-ME kinase inhibitory activity. Further, we attempted to model, in silico, the introduction of a –CONH2 functional group, but this modification also did not improve the binding energy (−19.26 kcal/mol), neither did the introduction of small hydrophobic–CH3 (compound 11) or 3,4-dihydroxy groups (compound 9) (Table 1). Nevertheless, the details of the binding mode of these analogs have improved our understanding and the possibility of optimizing compound 1 to be more selective and potent CDP-ME kinase inhibitors. Our on-going efforts based on this SAR are aimed at modifications on the –C2 aryl ring for hydrophobic sub-pocket by reducing the lipophilicity for desolvation effect, enhancing Asp141 H-bonding interactions.

In the case of second scaffold from the compound 5, the isoxazole was considered for the search criteria to retain the His26 and Ty25/Phe185 interactions (Fig. 4b). The 2-substituted aryl ring to the extent is partially involved in ππ-stacking interaction with the Tyr25. Attempts were made for the modification of the 3-methyl site of isoxazol-5(4H)-one ring with hydrophobic aryl groups to extend further to Phe32, Asp141 and Ala140, which led to the change in binding energy from −24.92 to −23.61 kcal/mol. These modifications provided over 80% inhibition of CDP-ME kinase activity as illustrated by compounds 17, 18 (Table 1).

We have also tested some of the analogs of compounds 1, which were substructure search and additional docking experiments against E. coli CDP-ME kinase, for inhibitory properties against human GALK1. We found that except for compound 9, none showed significant inhibition up to 50μM (data not shown). This is not unexpected as we pointed out above that selectivity among GHMP kinase inhibitors do exist.

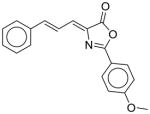

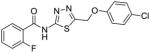

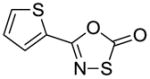

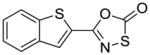

Computational screening and validation for novel CDP-ME kinase inhibitors by targeting the CDP-ME binding sites

To identify more novel and selective E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors, we performed a computational HTS of two million drug-like compounds with diverse chemical scaffolds. Our computational screening focused on the CDP-ME binding site and resulted in the selection of 210 compounds based on docking scores, complex energies and mode of binding within the defined cytidine pocket. These 210 hits were further analyzed with regards to solubility, permeability, Lipinski-like criteria and the presence of desired cytidine binding pharmacophore groups. This led to the selection of 89 compounds belonging to the two scaffold classes of 3,4-dihydro-2H-1,3-thiazine-5-carbonitrile (1) and isoxazol-5(4H)-one (5). 46 compounds from this series were further reviewed for the commercial availability and 23 compounds were planned for purchase for initial CDP-ME kinase inhibition screening. At the end, we were only able to procure ten of them. The virtual screening process led to the identified new tetrahydro-1,3,5-triazine scaffold-based hits 32 and 34 (Table 2), which exhibited binding energies of −24.43 and −26.91 kcal/mol with 40% and 80% CDP-ME kinase inhibitory activities respectively. Additionally, the benzo[d]thiazol scaffold containing compound 39, which was predicted as one of the high score hit (−29.26 kcal/mol), exhibited only modest inhibitory activity (65% Table 2). The tetrahydro-1,3,5-triazine-based scaffolds will therefore be prioritized over the compound 39 for lead optimization because of its chemical novelty.

Table 2.

Experimental validation of computational HTS

| Compound | % inhibition at 20μM |

|---|---|

31 |

40 |

32 |

40 |

33 |

50 |

34 |

80 |

35 |

40 |

36 |

40 |

37 |

40 |

38 |

30 |

39 |

65 |

40 |

45 |

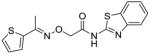

E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors cross-inhibit Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase

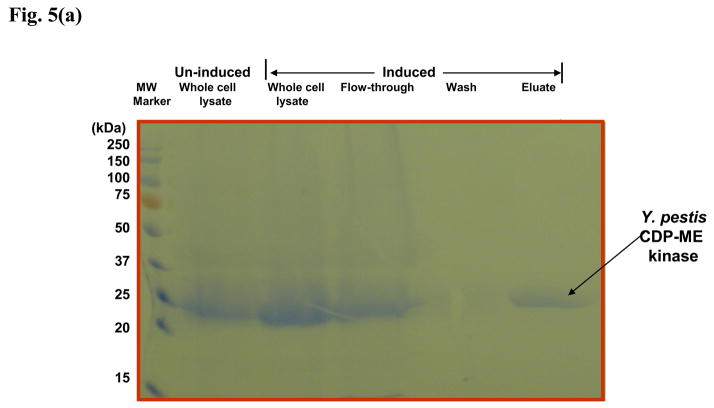

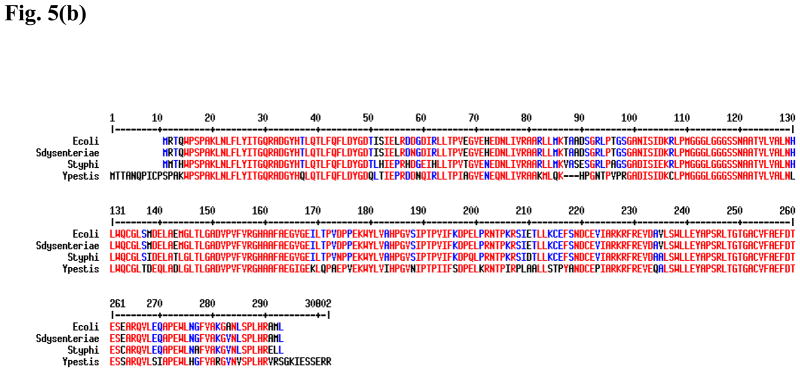

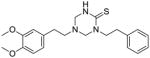

In order to see if any of the identified E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors show any cross-inhibition against the same enzyme from other Gram-negative bacteria, we over-expressed and purified recombinant Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase (Fig. 5a) and used it to test against the selected compounds. We chose Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase because this enzyme shares significant, but not excessive identity with the E. coli enzyme when compared to other more closely related species such as Salmonella sp. or Shigella species (Fig. 5b). All compounds tested showed cross-inhibition towards the Yersinia enzyme. Among six compounds tested, compound 1 and its derivative, 11, actually exhibited lower average IC50 values for the Y. pestis enzyme (9μM vs 18μM; and 15μM vs 20μM, respectively, Table 3). To validate the biochemical activity of compounds 1 and 11, we have performed the computational docking against the homology model of the Y. pestis enzyme constructed based on the E. coli CDP-ME kinase. The close identity and similarity between the Y. pestis and E. coli enzymes, 70% and 79%, respectively, facilitate the construction of the model with ICM and GLIDE docking programs. Using compound 1 in our validation test, we predicted that the 6-arylthio group of this compound to be positioned into the pocket created with Tyr25, His26, Pro182 and Phe185 residues, whereas the central thiazine-5-carbonitrile –C=O and –NH atoms would involve in hydrogen bonding interactions with same residue Asp141 of Y. pestis structure. Moreover, the 2-OH aryl group positioned the compound deep into the Lys10 and Pro182 sites and was predicted to form hydrogen bonding interaction with Lys10. This interaction retained the stable binding mode within the CDP-ME binding site of Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase and was reflected by a binding energy of −27.41 kcal/mol. These energy terms agreed with the biochemical data of compound 1 in inhibiting Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase.

Fig. 5.

(a) Purification of recombinant Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase by Nickel-affinity chromatography. Comassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE showing cell lysate from E. coli bacterial cells over-expressing Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase.

(b) Amino acid sequence alignment of CDP-ME kinases from E. coli, Shigella dysenteriae, Salmonella typhi, and Y. pestis. Residues highlighted in red are identical residues across all four species and residues highlighted in blue are conserved residues.

Table 3.

IC50 of selected E. coli CDP-ME kinase inhibitors against Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase

| Compound | IC50 (μM) for E. coli CDP-ME kinase | IC50 (μM) for Y. pestis CDP-ME kinase |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 | 9 |

| 11 | 20 | 15 |

| 5 | 5.5 | 6 |

| 17 | 8 | 13 |

| 18 | 7 | 12 |

| 19 | 8 | 13 |

Do identified CDP-ME kinase inhibitors inhibit bacterial growth?

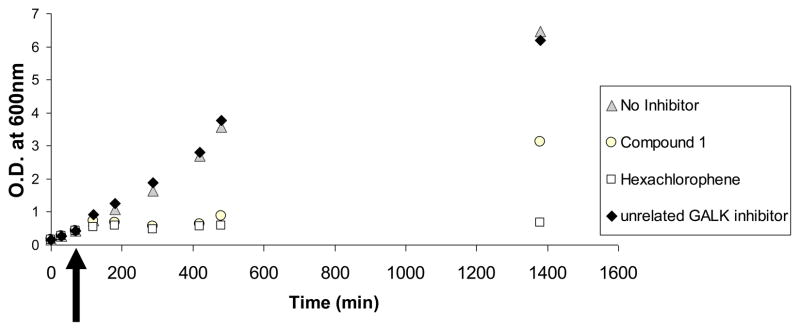

We have selected a few compounds to test for their inhibitory properties E. coli in culture. As shown in Fig. 6, at an external concentration of 50μM, compound 1 was able to inhibit the growth of E. coli culture for at least six hours. A known antiseptic, hexachlorophene, was used as a positive control while another compound with unrelated structure showed no inhibition at all. However, it appears that the bacteria eventually overcame the inhibition overnight, either by metabolism of the drug or efflux mechanisms. Thus, further optimization and/or repeated doses of these compounds will be needed to warrant sustained inhibition, if we decide to move forward with this class of compound. But before we investigated these issues further, we must confirm that the observed inhibition is due to the direction inhibition of CDP-ME kinase in the living bacterial cells. To accomplish this goal, we must establish the methodologies required to quantify CDP-ME and CDP-MEP (phosphorylated CDP-ME) in bacterial cell extracts. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no documented report on these methodologies and we are in the process of developing them and validating our cell-based results,

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of bacterial growth by small molecule compounds. Small molecule compounds 1, chlorohexene and a compound unrelated to compound 1 were added to growing E. coli cultures at time = +75 minutes (black arrow) at an external concentration of 50μM. The growth of bacterial cultures was followed for a period of 21 hours.

Conclusion

There is an urgent need to identify new antimicrobials of new structural classes. In this study, we focus on a novel target, CDP-ME kinase, which is absent in humans and higher animals. Through hit expansion, SAR and docking studies of existing GHMP kinase inhibitors, we have identified and confirmed two novel scaffold classes of CDP-ME kinase inhibitors with micromolar IC50 in in vitro assays. Computational HTS of over two million drug-like compounds yielded additional compounds which, at a concentration of 20μM, inhibited 80% and 65%, respectively, of control CDP-ME kinase activity. One chemotype identified has been shown to inhibit bacterial growth in culture, albeit at double-digit micromolar concentration. Our study represented the first report on random, unbiased HTS for inhibitors of CDP-ME kinases of two significant and deadly Gram-negative pathogens. Not only did our results serve to expand the repertoire of CDP-ME kinase inhibitors, they also paved the way for more in-depth medicinal chemistry work in the future.

Acknowledgments

Research grant support to Kent Lai includes NIH grants 5R01 HD054744-04, 5R01 HD054744-04S1 and 7R03 MH085689-02. We also want to thank Dr. Mark Fisher, U. of Utah and ARUP Laboratories, for the generous gift of genomic DNA isolated from Y. pestis KIM 6 strain.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Gaynes R, Edwards JR. Overview of nosocomial infections caused by gram-negative bacilli. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(6):848–54. doi: 10.1086/432803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balibar CJ, Shen X, Tao J. The mevalonate pathway of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(3):851–61. doi: 10.1128/JB.01357-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343(6257):425–30. doi: 10.1038/343425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smit A, Mushegian A. Biosynthesis of isoprenoids via mevalonate in Archaea: the lost pathway. Genome Res. 2000;10(10):1468–84. doi: 10.1101/gr.145600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dubey VS, Bhalla R, Luthra R. An overview of the non-mevalonate pathway for terpenoid biosynthesis in plants. J Biosci. 2003;28(5):637–46. doi: 10.1007/BF02703339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisenreich W, et al. Biosynthesis of isoprenoids via the non-mevalonate pathway. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61(12):1401–26. doi: 10.1007/s00018-004-3381-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunter WN. The non-mevalonate pathway of isoprenoid precursor biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(30):21573–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lichtenthaler HK, et al. The non-mevalonate isoprenoid biosynthesis of plants as a test system for new herbicides and drugs against pathogenic bacteria and the malaria parasite. Z Naturforsch C. 2000;55(5–6):305–13. doi: 10.1515/znc-2000-5-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eoh H, Brennan PJ, Crick DC. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis MEP (2C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate) pathway as a new drug target. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2009;89(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Testa CA, Brown MJ. The methylerythritol phosphate pathway and its significance as a novel drug target. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2003;4(4):248–59. doi: 10.2174/1389201033489784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Testa CA, Cornish RM, Poulter CD. The sorbitol phosphotransferase system is responsible for transport of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol into Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(2):473–80. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.2.473-480.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilding EI, et al. Identification, evolution, and essentiality of the mevalonate pathway for isopentenyl diphosphate biosynthesis in gram-positive cocci. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(15):4319–27. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.15.4319-4327.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zeidler J, et al. The non-mevalonate isoprenoid biosynthesis of plants as a test system for drugs against malaria and pathogenic bacteria. Biochem Soc Trans. 2000;28(6):796–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geist JG, et al. Thiazolopyrimidine inhibitors of 2-methylerythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (IspF) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Plasmodium falciparum. ChemMedChem. 5(7):1092–101. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinrich MR, Howard SM. Galactokinase. Methods Enzymol. 1966;9:407–412. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang M, et al. Molecular and biochemical characterization of human galactokinase and its small molecule inhibitors. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;188(3):376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wierenga KJ, et al. High-throughput screening for human galactokinase inhibitors. J Biomol Screen. 2008;13(5):415–23. doi: 10.1177/1087057108318331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ICM 3.4 Manual. Microsoft LLC; San Diego, CA: www.molsoft.com. [Google Scholar]

- 19.QikProp v.1.6. http://www.schrodinger.com/Products/quikprop.html.

- 20.Lipinski CA, et al. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;46(1–3):3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Veber DF, et al. Molecular properties that influence the oral bioavailability of drug candidates. J Med Chem. 2002;45(12):2615–23. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miallau L, et al. Biosynthesis of isoprenoids: crystal structure of 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(16):9173–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533425100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chin GJ, Marx J. Resistance to Antibiotics. Science. 1994;264(5157):359. doi: 10.1126/science.264.5157.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzberg O, Moult J. Bacterial resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics: crystal structure of beta-lactamase from Staphylococcus aureus PC1 at 2.5 A resolution. Science. 1987;236(4802):694–701. doi: 10.1126/science.3107125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall DA, et al. Resistance to antibiotics: administrative response to the challenge. Manag Care Interface. 2004;17(12):20–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walsh C. Where will new antibiotics come from? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2003;1(1):65–70. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crane CM, et al. Synthesis and characterization of cytidine derivatives that inhibit the kinase IspE of the non-mevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis. ChemMedChem. 2008;3(1):91–101. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch AK, et al. Inhibitors of the kinase IspE: structure-activity relationships and co-crystal structure analysis. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6(15):2719–30. doi: 10.1039/b804375b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirsch AK, et al. Nonphosphate inhibitors of IspE protein, a kinase in the non-mevalonate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis and a potential target for antimalarial therapy. ChemMedChem. 2007;2(6):806–10. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bork P, Sander C, Valencia A. Convergent evolution of similar enzymatic function on different protein folds: the hexokinase, ribokinase, and galactokinase families of sugar kinases. Protein Sci. 1993;2(1):31–40. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Timson DJ. GHMP Kinases - Structures, Mechanisms and Potential for Therapeutically Relevant Inhibition. Current Enzyme Inhibition. 2007;3(1):77–94. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rohdich F, et al. Biosynthesis of terpenoids: 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase from tomato. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(15):8251–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.140209197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eoh H, et al. Expression and characterization of soluble 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase from bacterial pathogens. Chem Biol. 2009;16(12):1230–9. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu Z, et al. The structure of a binary complex between a mammalian mevalonate kinase and ATP: insights into the reaction mechanism and human inherited disease. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(20):18134–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thoden JB, et al. Molecular structure of human galactokinase: implications for type II galactosemia. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(10):9662–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412916200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krishna SS, et al. Structural basis for the catalysis and substrate specificity of homoserine kinase. Biochemistry. 2001;40(36):10810–8. doi: 10.1021/bi010851z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sgraja T, et al. Characterization of Aquifex aeolicus 4-diphosphocytidyl-2C-methyl-d-erythritol kinase - ligand recognition in a template for antimicrobial drug discovery. Febs J. 2008;275(11):2779–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]