Abstract

Patients with adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency exhibit spontaneous and partial clinical remission associated with somatic reversion of inherited mutations. We report a child with severe combined immunodeficiency (T-B-NK- SCID) due to ADA deficiency diagnosed at the age of 1 month, whose lymphocyte counts including CD4+ and CD8+ T and NK cells began to improve after several months with normalization of ADA activity in PBL, as a result of somatic mosaicism due to monoallelic reversion of the causative mutation in the ADA gene. Our patient was not eligible for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or gene therapy (GT); therefore enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with bovine PEG-ADA was initiated. The follow up of metabolic and immunologic responses to ERT included gradual improvement in ADA activity in erythrocytes and transient expansion of most lymphocyte subsets, followed by gradual stabilization of CD4+ and CD8+ T (with naïve phenotype) and NK cells, with sustained expansion of TCRγδ+ T cells. This was accompanied by disappearance of the revertant T cells as shown by DNA sequencing from PBL. Although the patient’s clinical condition improved marginally, he later developed a germinal cell tumor and eventually died at the age of 67 months from sepsis. This case adds to our current knowledge of spontaneous reversion of mutations in ADA deficiency and shows that the effects of the ERT may vary among these patients, suggesting that it could depend on the cell and type in which the somatic mosaicism is established upon reversion.

INTRODUCTION

Autosomal recessive severe combined immunodeficiency due to adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID, OMIM #102700) is characterized by severe and recurrent early-onset infections, profound lymphopenia, absent cellular and humoral immunity and failure to thrive [1]. Its incidence is estimated between 1: 200,000 and 1: 1,000,000 live births and is the second most prevalent form of SCID, accounting for up to 20% of all cases. ADA is involved in the metabolism of purine nucleosides and its deficiency causes excessive accumulation of Ado and dAdo and preferential conversion of the latter to the toxic compound dATP, leading to its accumulation in plasma, red blood cells (RBC) and lymphoid tissues, where it impairs lymphocyte development and function throughout different mechanisms (reviewed in [2]). More than 65 different mutations have been described in the ADA gene in humans, from which nearly 70% are missense and the rest nonsense and splicing mutations [3, 4]. These usually correlate with the residual enzymatic activity as well as the extent of substrate accumulation and are reflected in a spectrum of clinical phenotypes [1, 3], being the most frequent the early-onset or fatal infantile onset (ADA-SCID) characterized by absent enzyme activity and total dAXP increased by 300 to 2000-fold in RBC. Other less frequent variants include delayed or late-onset and late or adult onset in some patients, as well as a partial ADA deficiency in a few healthy relatives of ADA-deficient patients [3–5].

ADA-SCID is commonly fatal within the first year of life, unless the immune system is reconstituted by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) or gene therapy (GT) [6]. Another option of treatment for patients who lack an immediate HLA-matched stem cell donor is enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) with pegylated bovine ADA (PEG-ADA) [6]. Continued administration of PEG-ADA eliminates dAXP and protects lymphocytes restoring immune function within 2 to 4 months in most patients [1]; however, in some long-term patients lymphocyte counts can diminish in time and abnormalities in lymphocyte function have been documented [7], [8]. In recent years, a small number of ADA deficient patients have been shown to have spontaneous and partial clinical remission with increasing numbers of peripheral blood (PB) lymphocytes, as a result of reversion of inherited mutations to wild type (ADA deficiency with somatic mosaicism) [9–13]. This phenomenon is being recognized in other primary Immunodeficiencies (PID) as well, and it might provide a model of the process of development of cell and gene therapy in these diseases [14]. Furthermore, the characterization of the immunologic and molecular effects of ERT in this type of patients is providing a unique opportunity to evaluate immune reconstitution in this particular setting. However, it is also being shown that the recovered immune function in these revertant patients might be very variable, suggesting that the effects of ERT might be unique to each patient.

In this report we describe the molecular and immunologic abnormalities associated with ADA deficiency in a child diagnosed initially at the age of 1 month with T-B-NK- SCID, in whom low numbers of PB T lymphocytes were found at the age of 23 months and became normal by 50 months of age. This was associated initially to a homozygous for the L107P mutation that later resulted in a mosaic in the patient due to a monoallelic reversion of the mutation that was documented in his T cells. As this child was not eligible for HSCT or GT, he was placed on ERT and we describe the molecular and immunologic changes due to the partial immune reconstitution and the clinical outcome after 17 months of ERT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient and control subjects

Our patient was a boy diagnosed with ADA-SCID at the Primary Immunodeficiencies Clinic in the University of Antioquia in Medellin (Colombia), that we followed until the age 67 months. Written informed consent approved by the IRB at the University of Antioquia was obtained from both parents and healthy age and sex-matched controls.

Immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocytes

Peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBL) from EDTA-whole blood were stained with different combinations of fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibodies against CD3, CD4, CD8, CD19, CD21, CD27, IgD, CD16, CD56, TCRαβ, TCRγδ, CD45RA and CD45RO (eBioscience Inc, San Diego, CA, and BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by treatment with lysing solution (BD FACS Lysing Solution®, BD Biosciences) for 10 min to remove RBC. After this, the cells were washed twice in PBS (Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline, Sigma Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), and fixed in 200 μl of 2% formaldehyde and read on a FACScan Flow Cytometer equipped with a 388 nm laser (Becton Dickinson). Files were analyzed using the software FlowJo v8.2 (TreeStar Inc, Ashland, OR) and the results were compared with the controls as indicated [15].

Mutation Analysis

Genomic DNA from the patient and controls was extracted from whole blood, PBL and buccal epithelial cells as well as from negatively enriched CD3+ T cells using a DNA Purification Kit (Puregene, Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Primers and PCR conditions used for the amplification of all ADA exons have been described previously [5, 16]. The nucleotide sequences were determined using the genetic analyzer ABI-PRISM 3100 (AB Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), and analyzed using the Sequencher software v. 4.8 (Gene Codes Corporation, MI, USA).

ADA activity and adenine nucleotide content in RBC

Anticoagulated-whole blood from the patient, the parents and a healthy control were applied separately to filter cards (FTA cards, Whatman Inc, Piscataway, NJ) and allowed to dry completely. The dry blood spots were extracted on ice with 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 15 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, and ADA and Purine Nucleoside Phosphorylase (PNP) activities as well as the total protein content were assayed as described previously [12]. An additional aliquot of the extract was treated with perchloric acid, neutralized, and analyzed for AXP and dAXP content; “percent dAXP” (dAXP/(AXP + dAXP) X 100) was used to assess dAXP elevation [12].

Cell Proliferation assays

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from the patient and controls were purified from whole blood using density gradient centrifugation with Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma Aldrich) and suspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10% human serum. PBMC at 2 × 105 from each individual were added in triplicates to 96-well U-bottom plates (Falcon-Becton Dickinson, San Diego, CA) and cells were stimulated with Phytohemagglutinin (PHA, Sigma Aldrich) at 5, 10 and 20 μg/ml, and cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C containing 5% CO2 for 86 h. One μCi of 3H-thymidine (MP Biomedicals, Irving, CA) was added to each well where the cells were cultured for an additional 20 h. The plates were harvested onto glass fiber filter papers (Inotech Biosystems Internacional Inc, Rockville, MD) using an automated multisample Cell Harvester (Inotech Biosystems). Counts per minute (cpm) were measured using a liquid scintillation counter (Plate Chameleon, Multilabel reader, Hidex, Turku, Finland), and the results were expressed as proliferation index (PI), calculated by dividing the mean cpm from the triplicates of stimulated cells by the mean cpm of triplicates from unstimulated cells.

Complementarity Determining Region 3 (CDR3) size distribution analysis of T cells

Anticoagulated-whole blood was collected from the patient and the controls and treated with RNA Stabilization Reagent (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and stored at −20°C until use. Total RNA was isolated using the High Pure RNA Isolation kit (Roche Diagnostics) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with the exception that stabilized samples were directly added to the filters instead of the initial lysis step. The cDNA was generated from 2 μg of total RNA using the SuperScript II reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and later used as template for PCR using 24 different unlabeled TCR Vβ primers (Gene Probe Technology, Gaithersburg, MD) and a 6-fluorescein phosphoramidite (6-FAM)-labeled Cβ-specific primer (Invitrogen) that recognizes both Cβ1 and Cβ2. PCR conditions included 40 cycles of amplification at 95°C/2 min, 95°C for 45 s, 60°C/45 s, 72°C/54 s, with a final step at 72°C/7 min. PCR products were mixed with formamide (Hi-Di, Applied Biosystems) plus a size standard (ROX- GeneScan 400HD, Applied Biosystems) and denatured for 2 min at 90°C. The size distribution of each product was determined on an ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems); the analyses were performed with the GENESCAN software (Applied Biosystems) and are shown as graphics of the distribution of peaks by size (spectratype).

RESULTS

Case Report

The boy was born from non-consanguineous parents and had one older female sibling that died from sepsis at the age of 6 months from suspected PID. Soon after birth our patient developed respiratory distress syndrome and neonatal jaundice and was hospitalized with the diagnosis of neonatal sepsis; he was treated accordingly and discharged after 20 days. Due to his previous family history, an initial immunophenotyping of PBL populations was performed at the age of 1 month, revealing very low T, B and NK cell counts (Table 1); in addition, he had normal serum IgA and IgM but low IgG. He was referred to our clinic at the age of 3 months for further evaluation, and we found a child with low weight-for-age but the physical exam was otherwise unremarkable; nonetheless, the chest X-rays did not show a thymic shadow. A new immunophenotyping of PBL confirmed the severe lymphopenia (250 cells/μl) affecting all lymphocytes, and this time he had normal IgG and IgA but low IgM for his age (Table 1). With the diagnosis of SCID treatment was initiated with prophylactic antimicrobials and intravenous gammaglobulin (IVIG) while he awaited HSCT, however we did not see him again until the age of 23 months. By now at this age he had already suffered several moderate-to severe infections (one UTI, 2 bronchopneumonias and had chronic diarrhea), and his physical exam revealed significant failure to thrive, hypotrophic tonsils and a few small inguinal lymph nodes. However, the phenotyping unexpectedly revealed increased lymphocyte counts (1404 cells/μl) that were mostly T cells (894 cells/μl compared to < 100 cells/μl from previous results), although they were still below normal for age (Table 1); in contrast, B cell counts had remained unchanged while NK cell counts improved slightly.

Table 1.

Lymphocyte subsets in PB and serum Ig levels in the ADA deficient patient

| Age in months | 1 | 3 | 23 | 50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Lymphocytes (cell/μl) | ND (3500–13100) | 250 (3700–9600) | 1404 (2700–11900) | 3889 (1700–6900) |

| CD3+ (cells/μl) | 68 (2300–7000) | 73 (2300–6500) | 894 (1400–8000) | 3348 (900–4500) |

| CD3+CD4+ (cell/μl) | 63 (1700–5300) | 15 (1500–5000) | 244 (900–5500) | 402 (500–2400) |

| CD3+CD8+ (cell/μl) | 5 (400–1700) | 57 (500–1600) | 605 (400–2300) | 747 (300–1600) |

| CD19+ (cell/μl) | 20 (600–1900) | 58 (700–2500) | 16 (600–3100) | 11 (200–2100) |

| CD3−CD16/56+ (cell/μl) | 2 (200–1400) | 22 (100–1300) | 74 (100–1400) | 498 (100–1000) |

| IgG (mg/dl) | 675 (793–1339) | 282 (236–1291) | 516.6* (642–2616) | ND |

| IgM (mg/dl) | 30 (9–148) | 13 (21–199) | 93.1* (39–576) | ND |

| IgA (mg/dl) | 0.006 (0–20) | 34 (2–270) | 125* (44–313) | ND |

Normal ranges for age are shown in parentheses [15]. The asterisks denote that the patient was already on IVIG replacement therapy at this age. Bold numbers denote abnormal counts per microliter.

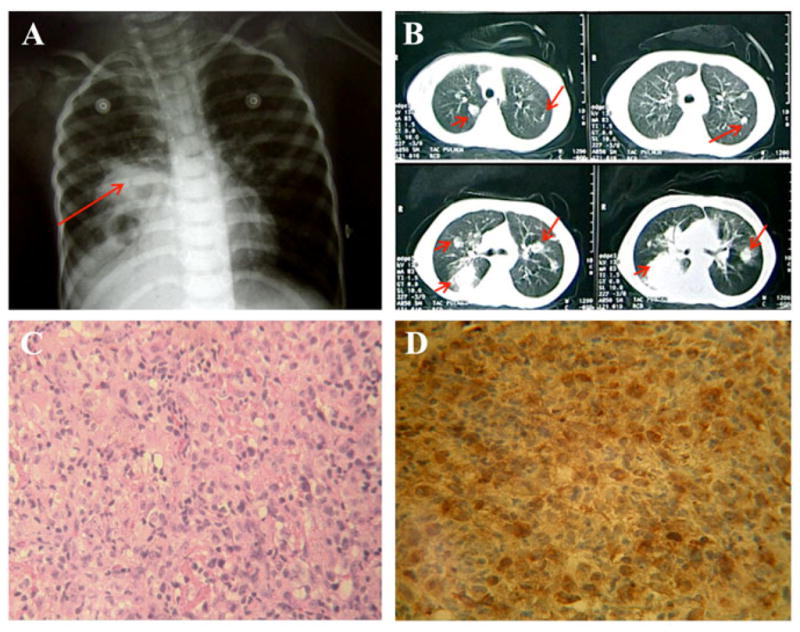

By the age of 50 months the patient already exhibited normal numbers of total lymphocytes in PB (3889 cells/μl, mostly T and NK cells). However, he also had suffered multiple infections and had chronic lung damage, despite the continued use of prophylactic antibiotics and IVIG. At this time HSCT or GT could not be performed, therefore we placed him on ERT with PEG-ADA and his clinical condition began to improve. Yet two months later he was hospitalized with pansinusitis, otitis, diarrhea and severe malnutrition. We noted that liver enzymes and bilirubin were increased and the diagnosis of sclerosing cholangitis was established; he was treated accordingly but showed only partial improvement. In the next few months he continued to have recurrent sinusitis and bronchitis, although these were less severe and responded faster to treatment. Nonetheless, at the age of 63 months he started to show persistent bronchospasm and chest X-rays as well as a lung CT-scan revealed multiple nodules involving both lungs (Figure 1, A and B). H & E stain from a biopsy of one nodule showed normal tissue being replaced by anaplastic cells suggestive of a malignancy, and ICH for placental alkaline phosphatase was positive indicating a primary germ cell tumor (probably a metastasis) of unknown location. (Figure 1, C and D respectively). Despite this, ERT was continued along with palliative therapy for pain management until the patient eventually died at the age of 67 months due to a septic shock.

Figure 1. Chest X-rays and CT Scan of lungs and lung biopsy.

(A) Chest X-rays: dense areas are observed with the aspect of “cannonballs” compatible with pulmonary compromise secondary to a neoplastic process; B) CT Scan of the lungs showing multiple nodules involving both lungs; (C) H&E staining showing the normal tissue replaced by anaplastic cells and the presence of abnormal mitosis (400X); (D) Immunohistochemistry with Avidin-Biotin Peroxidase showing the expression of placental alkaline phosphatase enzyme (PLAP) throughout the tissue sample from the same nodule (400X).

Molecular and biochemical basis of the immune deficiency in the patient

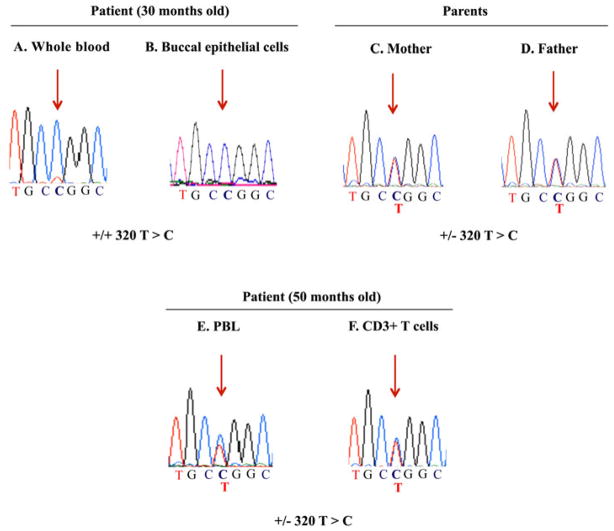

In order to investigate the molecular basis of his immune deficiency, we obtained genomic DNA from the patient at the age of 30 months and sequenced all the exons of the ADA gene from whole blood and buccal epithelial cells. As shown in Figure 2 (upper panel, A and B), we found in both samples a homozygous missense mutation in exon 4 (g.29009 T>C) that leads to a replacement of a leucine for a proline in the position 107 of the protein (L107P). This mutation has been reported previously and results in ≤ 0.05% of ADA activity in vitro, correlating with the clinical phenotype of severe early-onset ADA deficiency [5]; in addition, both parents were heterozygous for this mutation (Figure 2 upper panel, C and D). We also measured the ADA activity in the dried blood spots obtained from the patient and found no activity on his RBC (0 vs. 25.5 nmol/h/mg protein in the control) (Table 2, 30 months old); moreover, both parents showed approximately half of the ADA activity observed in the healthy control. However, the dAXP were modestly elevated (14.1% vs. 0% for the healthy control and 50.3 ± 18% for patients with ADA-SCID), a finding more consistent with a delayed-onset phenotype.

Figure 2. Sequencing of exon 4 of the ADA gene in genomic DNA from the patient and his parents.

Chromatograms detailing a fragment of exon 4 of the ADA gene obtained after sequencing the genomic DNA obtained from the patient at the age of 30 months (A and B, whole blood and buccal epithelial cells respectively) and 50 months (E and F, PBL and CD3+T cells), as well as from whole blood from his parents (C and D). Red arrows indicate the position of the mutated nucleotide C and/or the parental T.

Table 2.

ADA enzyme activity and % dAXP on the patient and his parents

| RBC | PBL | RBC Nucleotides | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADA nmol/h/mg | PNP nmol/h/mg | ADA nmol/h/mg | PNP nmol/h/mg | % dAXP | |

| Healthy Control | 25.5 | 1086 | - | - | 0.0 |

| ADA-SCID Control | 0.38 ± 0.5 | - | - | - | 50.3 ± 18 |

| Patient (30 months old) | 0.0 | 1339 | ND | ND | 14.1 |

| Patient (50 months old) | 0.7 | 1511 | 3492 | 13967 | 4.7 |

| Mother | 14.6 | 867 | ND | ND | 0.0 |

| Father | 9.5 | 959 | ND | ND | 0.0 |

| Normal values | 33 ± 14 | 2382 ± 183 | 1197 ± 516 | 3007 ± 824 | < 0.2 |

The dAXP levels and ADA activity in the patient at the age of 30 months were measured in RBC only, while at 50 months measurements were performed both on RBC and PBL (bold numbers). PNP, purine nucleoside phosphorylase; RBC, red blood cells; PBL, peripheral blood lymphocytes; dAXP, dado nucleotides.

Origin of the increase in T lymphocytes in the patient

An unexpected increase in numbers of T lymphocytes in patients with SCID could be more often explained by spontaneous engraftment of maternal lymphocytes or alternatively, by transfusion of HLA-mismatched non-irradiated blood products [3]. As no records of previous blood transfusions were found, we karyotyped his PBL and performed HLA typing on him and his parents, and found that our patient was 46 (X, Y) and was HLA-haploidentical to his parents, excluding maternal and transfusion-related engraftment of T cells (data not shown). The possibility of somatic mosaicism due to a de novo mutation was excluded because both parents were carriers of the same mutation (Figure 2).

Since a small number of ADA deficient patients reported up to date exhibit variable counts of T lymphocytes that result from an in vivo reversion of inherited mutations in the ADA gene [9–13], we decided test this possibility on his T cells. As his lymphocyte counts reached normal values (Table 1, age 50 months) we first sequenced again the genomic DNA from PBL as well as from DNA obtained from negatively enriched T cells and found that in contrast to the previous state of homozygosity for the L107P mutation, he was now heterozygous for the L107P mutation due to the presence of the wild-type thymine (T) on one allele (Figure 2, lower panel E and F). These results demonstrated that the T cells now harbored a mutant and a wild type sequence, confirming the in vivo reversal of the mutation in one allele of the ADA gene. We also measured the ADA activity at this time (Table 2, 50 months old) and found that RBC had some activity (although still very low compared to a healthy control), and continued to show a modest but lower level of dAXP than previously. However, the ADA activity on his PBL was almost 3 times higher when compared to reference values (Table 2, age 50 months). This suggested that the revertant T cells could have contributed to mildly improve the immune function in the patient allowing him to survive past 4 years.

Evolution of lymphocyte populations and in vitro lymphocyte function during the ERT with PEG-ADA

For ADA deficient patients in whom immune reconstitution by HSCT or GT is not feasible, ERT with PEG-ADA is an option that leads to rapid improvement of lymphocyte counts within several weeks to few months after initiation of therapy [13, 17], and it has been used also even in situations in which a somatic mosaicism due to a reversion of an inherited mutation is detected. At the age of 50 months our patient was not eligible for HSCT or GT, therefore we started him on ERT at the dose of 30 U/kg of weight, and just after two weeks the ADA activity in PBL increased from 0.9 to 12.6 nmol/h/mg and the dAXP decreased from 10.4% to 2.7% (not shown). However, difficulties in adherence to treatment, led to some fluctuations in ADA activity and dAXP, therefore we increased the dose to 50 U/kg after 10 months of treatment and this quickly led to normal ADA activity and undetectable dAXP (not shown).

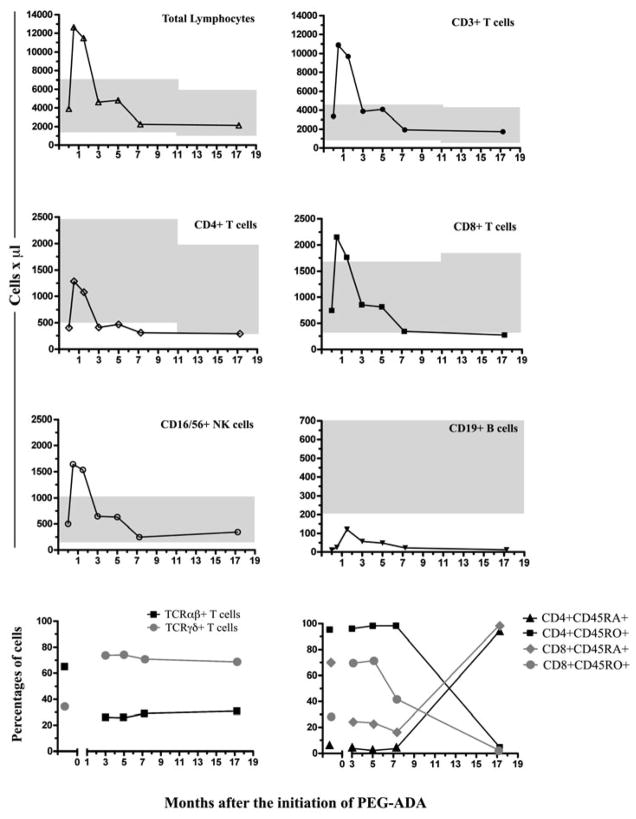

In order to monitor the treatment with PEG-ADA, we decided to phenotype all the main lymphocyte populations in PB at several intervals after the initiation of therapy. As mentioned earlier, by the age of 50 months our patient had normal PBL counts with normal CD3+, CD8+ and CD16/56+ NK lymphocytes, and although CD4+ T cells also increased they were still below normal; CD19+ B cells remained unchanged (Table 1, age 50 months). Just after only 2 weeks on PEG-ADA led to a rapid increase in PBL counts exceeding the reference values for the patient’s age including CD3+, CD8+ T cells as well as NK cells (12637, 10880, 2154 and 1643 cells/μl, respectively; see Figure 3). CD4+ T cells also increased reaching normal values transiently (1284 cells/μl); moreover, CD19+ B cells also increased but always remained below normal (25 cells/μl). Interestingly, lymphocyte (and subset) counts returned to normal or just below normal after 3 months of therapy and remained stable for the next 14 months (Figure 3). These results demonstrated that the ERT resulted in a transient expansion in total counts for most lymphocyte populations in PB.

Figure 3. Phenotyping of the main lymphocyte subsets before and during ERT with PEG-ADA.

The shapes and connecting lines on every graph represent the total counts at the different times before and after the initiation of the ERT in our patient. In the upper 6 panels, shaded areas represent the absolute counts per microliter of the main lymphocyte subpopulations in PB (median and percentiles: 5th to 95th percentiles), according to age in normal children [15]. The percentages of TCRαβ+ and TCRγδ+ were analyzed on CD3+ gated T cells; percentages of CD45RA and RO+ T cells were analyzed on the CD4+ and CD8+ gates respectively.

The mature pool of T lymphocytes in PB in humans is comprised of clonally-derived TCRαβ+ and TCRγδ+ T cells in a proportion of 90% vs ≤ 10%, respectively [18], however our patient had an abnormal distribution of these cells (65% TCRαβ+ vs 34.4% TCRγδ+, respectively; Figure 3 lower left panel) before ERT. Interestingly, the treatment with PEG-ADA led to a decrease in TCRαβ+ T cells while TCR γδ+ T cells expanded (~ 30% and > 70%, respectively), and these changes remained constant throughout the therapy. In addition, before the ERT his T cell repertoire was comprised of low numbers of CD4+CD45RA+ and high numbers of CD8+CD45RO+ T cells (5.6% vs 71.3% respectively; figure 3, lower right panel). However, these percentages started to change with ERT and by 17 months, the percentages of naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that were CD45RA+ had increased to 94.4% and 99.5% respectively. We also evaluated T cell proliferation to PHA and found that before therapy, T cells did not proliferate in response to PHA (PI = 0.99; SE = 1.14–1.15) when compared to healthy controls (PI = 6.40, SE = 16.03–22.03), and even after 3 months there was no detectable lymphoproliferation (data not shown). However after 6 months of PEG-ADA, we could observe proliferation of PBL to PHA (PI = 2.45; SE = 4.22–3.69), although it remained very low as compared to controls (PI = 3.53; SE = 6.45–7.97).

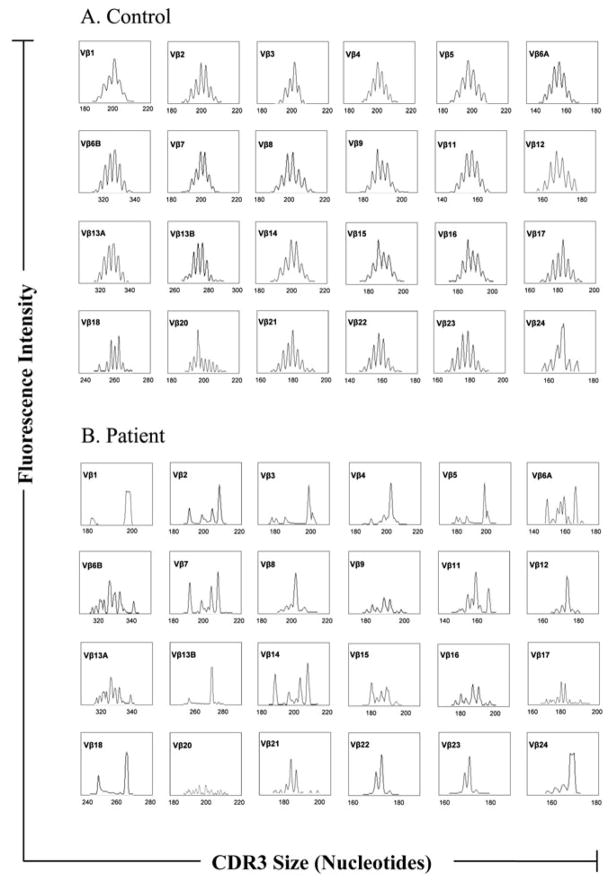

Clonality of the T cells in our patient after ERT with PEG-ADA

The lymphoproliferation to mitogen in the PB T cells from our patient at 50 months before ERT suggested that although their numbers were now normal, their functionality seemed to be compromised. In fact, SCID due to mutations in the Rag1/Rag2 genes (the variant also known as classic Omenn syndrome) is characterized by marked lymphocytosis, yet these cells are non-functional and exhibit a limited clonality [19]. T cell spectratypying has been recently used as a tool to assess clonality in an ADA deficient revertant patient that was placed on ERT [13], therefore we performed cDNA size distribution analysis of the TCRβ variable CDR3 regions in the T lymphocytes of our patient (CD3-size spectratyping) for 24 Vβ families after 12 months of PEG-ADA therapy and found that the patient had a severely skewed distribution of peaks for all Vβ families. This was due to a markedly oligoclonal T-cell repertoire in Vβ families 1, 4, 5, 8, 12, 13B, 18 and 24 while the rest of the Vβ families exhibited a pattern of clonal dominance and a more restricted repertoire (Figure 4). This is in contrast to the polyclonal profile observed from the T lymphocytes obtained form a healthy age and sex-matched control.

Figure 4. Distribution of CDR3 sizes of 24 V β families of TCR in lymphocytes in our patient and a healthy control.

(A) Healthy control and (B) Patient. Each peak corresponds to fragments of 3 nucleotides in length. Results are shown for each Vβ family as a density peak histogram. Each peak corresponds to different length fragments and a polyclonal repertoire with 6–10 peaks (Gaussian profile) is exhibited by normal controls, but an oligoclonal T cell expansion (dominant peaks) results in profiles of ≤ 4 peaks per Vβ family.

Relationship between PEG-ADA therapy and decreased revertant cells

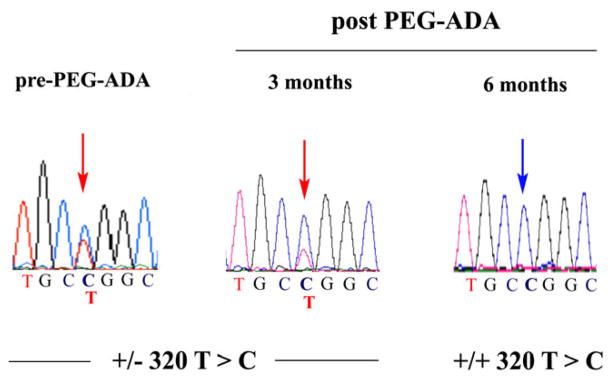

In patients with somatic mosaicism, the continued administration of PEG-ADA has shown to decrease the in vivo selective advantage of the revertant cells [12]. To evaluate this in our patient we sequenced exon 4 again in the genomic DNA from PBL obtained before ERT, as well as 3 and 6 months post-therapy, and these results showed that the patient was heterozygous before PEG-ADA, indicating the presence of the revertant cells (Figure 5, CTG-Leu, normal sequence along with CCG-Pro). However, after 3 months of therapy the intensity of the reversion of the C > T peak decreased and by 6 months it disappeared (CCG, Pro, mutated sequence), confirming that the ERT eliminated the revertant cells in vivo in our patient.

Figure 5. Gradual loss of the revertant nucleotide in PBL after PEG-ADA.

Exon 4 of the ADA gene was sequenced from genomic DNA in the patient 3 and 6 months after initiation of the ERT. Left chromatogram corresponds to the sequence at 50 months just before the start of the ERT (from Figure 2), and it is shown to illustrate the changes in the peak as the therapy progressed (middle and right chromatograms). Red arrows indicate the position of the mutated nucleotide C and/or the parental T; blue arrow indicates the homozygous T.

Discussion

We report a child with ADA-SCID in whom an unexpected graduate increase in PBL was the result of a monoallelic reversion of a homozygous missense mutation (L107P) resulting in somatic mosaicism in his CD3+ T cells and to our knowledge, this is the first case in which this mutation is spontaneously reversed in vivo in an ADA-deficient patient. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated in vitro that this mutation results in almost no ADA activity and correlates well with the severity of the disease [5]. Our patient showed severe lymphopenia from the age of 1 month and developed a neonatal life-threatening severe infection, showing that this mutation had a causative effect in the phenotype observed initially. In fact, our patient continued to suffer from recurrent and chronic infections that eventually led to failure to thrive as well as organ damage. However, he survived past 4 years only with antimicrobials and IVIG, therefore the progressive retention of ADA activity in the revertant cells not only increased the T cell counts in time (although we did not observe lymphoproliferation to PHA), but also ameliorated his clinical condition. This is in contrast to other revertant patients in which their mutations have been associated to a milder phenotype from the initial diagnosis, making it difficult to establish the actual contribution of the somatic reversion to the phenotypes [20], [13]. Revertant somatic mosaicism leading to unusual phenotypes continue to be described suggesting that these events might be more common than initially considered and these patients the reversions resulted from multiple mechanisms (reviewed in [21]). However, back mutations like the one found in our patient are most likely random and may reflect an increased mutation rate due to accumulation of mutagenic metabolites [22].

As our patient was not eligible for HSCT or GT, we placed him on ERT with PEG-ADA at the age of 50 months. However, we believe that the impact of this therapy was marginal because although his clinical condition improved during the first months (gain of weight and less severe and frequent infections), he also developed sclerosing colangitis just after 2 months of ERT, a complication linked to opportunistic infections with protozoa in patients with other PID [23]. Although we could not find reports of its association with ADA deficiency and/or to the ERT and we do not know if it was a secondary effect of the therapy (no microorganism could be isolated), it is also tempting to speculate that this might have indirectly impacted the outcome of the therapy. Complications that contribute to mortality during treatment with PEG-ADA include refractory hemolytic anemia, chronic pulmonary insufficiency, lymphoproliferative disorders and solid tumors in the liver [6, 24, 25]. However, these have been identified in patients under different circumstances and their relationship to the ERT has not been established. Finally, our patient is the first to our knowledge in which a rare and aggressive germinal cell tumor has been identified. A retrospective look at images before PEG-ADA did not provide clues to suggest that this tumor was already present at the start of the therapy; therefore his relationship to the ERT is currently unknown.

The phenotyping of the circulating T cells detected in our patient from the age of 23 months and up to the point before the start of ERT showed that they were mostly CD8+, although CD4+ T cells were also raising (but remained below normal). Moreover, NK cells also increased and reached normal counts by 50 months of age, suggesting that a common T/NK committed lymphoid progenitor might have been affected by the partial reversal of the mutation, and that the reversion might have taken place in NK cells as well [26]. However, we were only able to show that negatively enriched CD3+ T cells harbored the revertant nucleotide, therefore we don’t know in which T cells (CD4+ and/or CD8+) and NK cells, the reversion also took place. With respect to the phenotype of the few circulating CD19+ B cells we only phenotyped them at 35 before ERT and found that similarly to what was observed by Liu et al in their revertant patient [13], > 80% of the B cells were also switched memory (IgD-CD27+) B cells (not shown). One intriguing aspect of this revertant patient was that the severe infectious episodes, his PBL cells expanded transiently up to 6000 cells/ml (data not shown). We could not demonstrate that PBL proliferated in response to PHA before ERT; therefore we assume that some undefined mechanism must have promoted these transient expansions. Interestingly, it has been shown in mice that in lymphopenic environments, T cells can proliferate in response to autologous antigens presented in the context of MHC-I and growth factors such as IL-7 and IL-15, a phenomenon known as homeostatic proliferation [27]. Whether a similar mechanism was responsible for promoting and maintaining a level of homeostatic proliferation in our patient could not be tested.

In our patient, the ERT with PEG-ADA resulted in long-term correction of the metabolic abnormalities, along with a transient expansion of PBL including CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and NK cells, followed by stabilization of lymphocyte counts and mild lymphoproliferation. It has been reported that in ADA-deficient patients, CD3dimCD4−CD8− T cells appear approximately between the 5th and 10th weeks of PEG-ADA treatment, and CD3brightCD8+ and CD3brightCD4 + (mature T cells) after week 12 [17]. However, our ADA-deficient patient was a revertant that had normal T and NK cell counts (with the exception of CD19+ B cells) before starting ERT (Figure 3). Therefore, it is likely that the transient expansion in T, B and NK subsets observed during the first two weeks after ERT was partly due to a clonal expansion of pre-existing cells. Still, is possible that non-revertant cells also contributed to this as some T cell populations (TCRγδ+ T cells) also expanded (Figure 3, lower right panel). Liu et al reported that before ERT, their revertant patient had mostly circulating CD8+ T cells with a terminally differentiated phenotype [13]. Furthermore, over the course of 9 months of ERT his patient steadily accumulated mature naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [13]. Interestingly, in our patient we observed in his CD8+ T cells a transition from > 60 % CD45RA+ to < 30% with transient expansion of CD45RO+ T cells within the initial 3 months of therapy (Figure 3). Moreover, the CD4+ T cells were mostly CD45RO+ and remained as such for up to 7 months after ERT. Nevertheless, after 17 months on ERT all his CD4+ and CD8+ T cells became CD45RA+ [13]. Therefore, it is possible that differences in the revertant phenotypes attributed to long-term exposure to ADA in the context of the deficiency, might reflect differences in how the T cells are reconstituted with PEG-ADA. In addition, differences in PEG-ADA administration dosages and regularity, as well as different residual thymic function at the time of initiation of the ERT could have also contributed to these differences among patients. In fact, while in the patient reported by Liu et al the CD4, CD8 and B cells steadily increased, in our patient those numbers returned to pre-PEG-ADA levels after the initial expansion. Therefore, it is also possible that the high level of CD45RO+ CD4+ and CD8+ T cells that were observed during the first months of ERT in our patient, resulted from the expansion of CD3+TCRαβ+ T cells. On the other hand, the total numbers of CD19+ B cells in our patient remained well below the normal throughout the ERT. This contrasts with findings by others showing that B cells from ADA deficient patients with or without revertant T cells, reach steady numbers during the first months of treatment [13, 28]; the reason for this variability among patients remains unclear. In addition, recovery of function of B cells in response to immunization after ERT, have yielded variable results with absent or [13] or normal humoral responses [29]. Unfortunately we were unable to evaluate them in our patient.

Liu et al reported that the initial TCRvβ repertoire in the T cells from his patient was substantially restricted and consistent with a dominant oligoclonal CD8+ population, however after 8 months it became more polyclonal and correlated with the accumulation of naïve T cells in response to ERT [13]. We only analyzed the TCRvβ repertoire in our patient after 12 months of ERT and the results showed that it was markedly oligoclonal (Figure 4). We did not look for naïve T cells at this time neither we performed additional spectratyping later, nevertheless it is tempting to speculate that this could be partly explained by the preferential expansion of TCRγδ+ T cells observed early during ETR, as these cells are known to have a restricted TCR repertoire. It has also been reported that PEG-ADA therapy normalizes toxic levels of Ado and dAdo, allowing the ADA-deficient cells to survive while the revertant cells lose their selective advantage [11, 12]. Our results also showed that the signal of revertant cells disappeared gradually and was no longer detectable after 6 months of PEG-ADA therapy, (Figure 5). Therefore, the marginal immune function observed in our patient is probably a reflection of the selective advantage conferred to the newly formed cells by the PEG-ADA therapy.

In summary, we report the first ADA deficient patient in which a fully penetrant mutation that manifested initially as classic SCID, eventually led to a “delayed onset” phenotype due to somatic mosaicism by reversion of the mutation in T cells. Our work highlights the differences that can be observed when monitoring the clinical and immunological function in these types of patients within a context of different mutations, but even more the clinical and immunologic effects in the revertant phenotype once they are under the effects of the ERT with PEG-ADA. Our findings might provide additional insight into the effects of immune reconstitution by gene therapy in ADA deficiency, particularly in patients that have been treated previously with ERT.

Acknowledgments

We deeply appreciate the commitment of the patient and his parents to perform these studies. Acknowledgments are made to Carlos J. Montoya, Olga L. Morales, Alejandra Wilches, Dagoberto Cabrera and Yadira Coll for their dedication to the care of our patient. We also thank the Grupo de Inmunología Celular e Inmunogenética (University of Antioquia, Medellín, Colombia) for their help with the HLA typing. This work was supported by the Group of Primary Immunodeficiencies and the Fundación “Diana García de Olarte” para las Inmunodeficiencias Primarias -FIP- (Medellín, Colombia).

References

- 1.Hershfield MS, Mitchell BS. Immunodeficiency diseases caused by adenosine deaminase deficiency and purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. McGraw-Hill; New York: 2001. pp. 2585–2625. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershfield MS. New insights into adenosine-receptor-mediated immunosuppression and the role of adenosine in causing the immunodeficiency associated with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(1):25–30. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirschhorn R, Candotti F. Immunodeficiency Due to Defects of Purine Metabolism. In: Ochs SCHD, Puck JM, editors. Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases: A molecular and genetic approach. Oxford University Press; New York: 2007. pp. 169–196. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershfield MS. Genotype is an important determinant of phenotype in adenosine deaminase deficiency. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15(5):571–7. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(03)00104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arredondo-Vega FX, et al. Adenosine deaminase deficiency: genotype-phenotype correlations based on expressed activity of 29 mutant alleles. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(4):1049–59. doi: 10.1086/302054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaspar HB, et al. How I treat ADA deficiency. Blood. 2009;114(17):3524–32. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-189209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malacarne F, et al. Reduced thymic output, increased spontaneous apoptosis and oligoclonal B cells in polyethylene glycol-adenosine deaminase-treated patients. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35(11):3376–86. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan B, et al. Long-term efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy for adenosine deaminase (ADA)-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) Clin Immunol. 2005;117(2):133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirschhorn R, et al. Somatic mosaicism for a newly identified splice-site mutation in a patient with adenosine deaminase-deficient immunodeficiency and spontaneous clinical recovery. Am J Hum Genet. 1994;55(1):59–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirschhorn R, et al. Spontaneous in vivo reversion to normal of an inherited mutation in a patient with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Nat Genet. 1996;13(3):290–5. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariga T, et al. T-cell lines from 2 patients with adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency showed the restoration of ADA activity resulted from the reversion of an inherited mutation. Blood. 2001;97(9):2896–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.9.2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arredondo-Vega FX, et al. Adenosine deaminase deficiency with mosaicism for a “second-site suppressor” of a splicing mutation: decline in revertant T lymphocytes during enzyme replacement therapy. Blood. 2002;99(3):1005–13. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu P, et al. Immunologic reconstitution during PEG-ADA therapy in an unusual mosaic ADA deficient patient. Clin Immunol. 2009;130(2):162–74. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada T, Candotti F. Somatic mosaicism in primary immune deficiencies. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8(6):510–4. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e328314b651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comans-Bitter WM, et al. Immunophenotyping of blood lymphocytes in childhood. Reference values for lymphocyte subpopulations. J Pediatr. 1997;130(3):388–93. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santisteban I, et al. Novel splicing, missense, and deletion mutations in seven adenosine deaminase-deficient patients with late/delayed onset of combined immunodeficiency disease. Contribution of genotype to phenotype. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(5):2291–302. doi: 10.1172/JCI116833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberg K, et al. T lymphocyte ontogeny in adenosine deaminase-deficient severe combined immune deficiency after treatment with polyethylene glycol-modified adenosine deaminase. J Clin Invest. 1993;92(2):596–602. doi: 10.1172/JCI116626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Vries E, et al. Longitudinal survey of lymphocyte subpopulations in the first year of life. Pediatr Res. 2000;47(4 Pt 1):528–37. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200004000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niehues T, Perez-Becker R, Schuetz C. More than just SCID--the phenotypic range of combined immunodeficiencies associated with mutations in the recombinase activating genes (RAG) 1 and 2. Clin Immunol. 2010;135(2):183–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Speckmann C, et al. Clinical and immunologic consequences of a somatic reversion in a patient with X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency. Blood. 2008;112(10):4090–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-153361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschhorn R. In vivo reversion to normal of inherited mutations in humans. J Med Genet. 2003;40(10):721–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.10.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brox L, et al. DNA strand breaks induced in human T-lymphocytes by the combination of deoxyadenosine and deoxycoformycin. Cancer Res. 1984;44(3):934–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodrigues F, et al. Liver disease in children with primary immunodeficiencies. J Pediatr. 2004;145(3):333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaufman DA, et al. Cerebral lymphoma in an adenosine deaminase-deficient patient with severe combined immunodeficiency receiving polyethylene glycol-conjugated adenosine deaminase. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):e876–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Husain M, et al. Burkitt’s lymphoma in a patient with adenosine deaminase deficiency-severe combined immunodeficiency treated with polyethylene glycol-adenosine deaminase. J Pediatr. 2007;151(1):93–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freud AG, Caligiuri MA. Human natural killer cell development. Immunol Rev. 2006;214:56–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyman O, et al. Cytokines and T-cell homeostasis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19(3):320–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bollinger ME, et al. Brief report: hepatic dysfunction as a complication of adenosine deaminase deficiency. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(21):1367–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochs HD, et al. Antibody responses to bacteriophage phi X174 in patients with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Blood. 1992;80(5):1163–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]