Abstract

Inorganic lead and mercury are widely spread xenobiotic neurotoxicants threatening public health. The exposure to inorganic lead and mercury results in adverse effects of poisoning including IQ deficit and peripheral neuropathy. Additionally, inorganic neurotoxicants have even more serious impact on earlier stages of embryonic development. This study was therefore initiated in order to determine the cytotoxic effects of lead and mercury in earlier developmental stages of chick embryo. Administration of inorganic lead and mercury into the chick embryo resulted in the prolonged accumulation of inorganics in the neonatal brain, with detrimental cytotoxicity on neuronal cells. Subsequent studies demonstrated that exposure of chick embryo to inorganic lead and mercury resulted in the reorganization of cytoskeletal proteins in the neonatal brain. These results therefore suggest that inorganics-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization of the structural proteins, resulting in neurocytotoxicity, is one of the underlying mechanisms by which inorganics transfer deleterious effects on central nervous system.

Keywords: Lead, mercury, neurotoxicity, tubulin, tau, chick embryo

Toxic metals have been a major global concern of the highest priority for human exposure, since they have a wide range of serious adverse effects, including carcinogenicity, neurotoxicity and immunotoxicity. The factors governing the neurotoxicity of metals and metalloids in specific neuronal tissue are multiple, and highly individualistic with different genetic susceptibility [1]. The neurotoxicity of inorganic lead (Pb) and mercury (Hg) in humans are well established, and exposure to these neurotoxic metals generally results in serious adverse effects, ranging from IQ deficit to peripheral neuropathy [2,3]. In view of the increasing evidence supporting deleterious effect of lead and mercury on central nervous system (CNS), it is important to develop a clearer understanding of the cellular mechanisms involved in the neurotoxicity mediated by lead and mercury.

Lead-mediated cytotoxicity in CNS leads to the generation of incompletely developed blood-brain barrier, encephalopathy, and impaired learning ability. On the other hand, lead-mediated neurotoxicity in developmental period was shown to be related with reduced hippocampal neurogenesis, axonal arborizations, and cortical field area, strongly suggesting detrimental effect of lead on neuronal development. Substitution of lead for dicationic ions including calcium and zinc contributes to the development of mitochondrial dysfunction, resulting in apoptosis and impaired cellular energy metabolism. Additionally, sequence-specific DNA-binding zinc finger protein for zinc binding sites in receptor channels resulted in the alteration of gene transcription [4,5].

Studies on mercury-mediated CNS toxicity have been mainly focused on three forms of organic mercury, aryl-compounds, short- and long-chain alkyl-compounds. Outbreaks of methyl mercury poisoning occurred in Minamata and Niigata in 1950s caused serous neurological syndrome. The fetal brain shown to be more susceptible to the organic mercury-mediated cytotoxicity, however it is not clear for the prenatal exposure to inorganic mercury. Elemental mercury is able to penetrate into the CNS, where it can be ionized and trapped, contributing to its significant neurotoxic effects. Although CNS penetration of salted inorganic mercury has been limited because of the poor lipid solubility, chronic exposure resulted in significant CNS accumulation of mercuric ions and subsequent neurotoxicity [6].

This study was therefore initiated in order to determine the effects of lead and mercury in earlier developmental stages in chick embryo. In the present study, administration of inorganic lead or mercury in early developmental stage of chick embryo led to the accumulation of inorganics in adult, resulting in the cytotoxicity of neuronal cells. Subsequently, exposure of chick embryo to inorganic lead or mercury led to the reorganization of cytoskeletal proteins, including tubulin and tau in the brain. These findings support the mechanisms by which inorganics transfers neurotoxic effects on CNS.

Materials and Methods

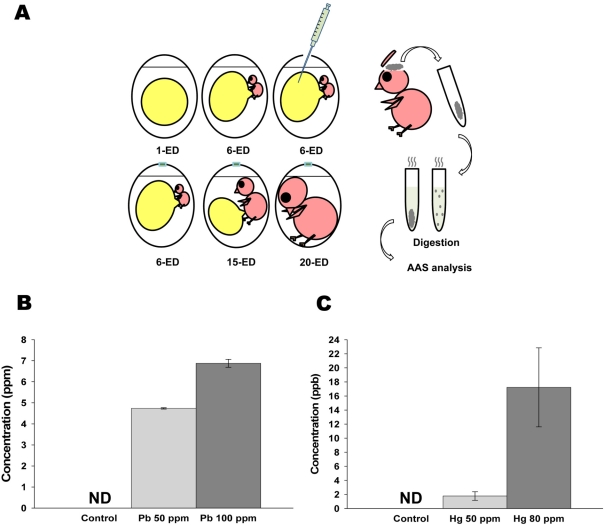

Direct administration of inorganic metals into yolk sac

Fertilized eggs (Pulmuone, Seongnam, Korea) were incubated in a 37℃ egg-incubator with approximately 60% of humidity. As shown in Figure 1, on 6-embryonic day (ED), indicated concentrations of lead or mercury were directly injected into yolk sac. On 20-ED, eggshell was crashed from the air sac side, and chick embryo was harvested. Brain was collected on ice, washed with ice-cold buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5), homogenized and stored at -80℃. All animal experiments were performed according to the protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Konkuk University.

Figure 1.

Administered lead (Pb) and mercury (Hg) in early developmental stage of chick embryo were still detectable in the brain of adult stage. (A) Schematic diagram of experimental design for AAS analysis. The prepared solution [0, 50 (25 µg/500 µL) and 100 ppm (50 µg/500 µL) of Pb; and 0, 50 (25 µg/500 µL) and 80 ppm (40 µg/500 µL) of Hg] was injected into each yolk sac of 6-ED chick embryos. On 20-ED, the collected chick embryo brains were digested for Atomic Absorption Spectrometry analysis. (B-C) Accumulated Pb (B) and Hg (C) in neonatal brain. Indicated concentration of inorganic Pb or Hg were injected into yolk sac on 6-ED. On day 20, the accumulated concentration of Pb (B) and Hg (C) in neonatal brain were determined by F-AAS as described in Materials and Methods. All data represent three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate, and significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test, where ** represents P<0.05 vs control. ND represents non-detectable.

Atomic absorption spectrophotometry (AAS)

Nitric acid, sulfuric acid and perchloric acid were mixed with 5:1:1 ratio for lead and 1:2:1 ratio for mercury, respectively. Following 6-h incubation at room temperature, samples were heated at 160℃, and completely digested samples were evaluated by F-AAS (AA-680; Shimazu, Tokyo, Japan), as described previously [7].

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

Following Pb (7 mM) and Hg (23 µM) treatment, cells were incubated with MTT (Sigma, St. Louis, USA) (50 mg/mL in PBS), for 4 h at 37℃. The precipitated formazan salt in viable cells after cleavage of the tetrazolium ring by mitochondrial dehydrogenases was dissolved in DMSO and read at 570 nm with an ELISA microplate reader (Bio-Tek, Winooski, USA).

Western blot analysis

Total brain extracts (50 µg/lane) were separated on a 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)/polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, Billerica, USA). Probing of the membranes was performed with anti-tubulin (65095; ICN, Irvine, USA) and anti-tau (65784; ICN) antibodies. Immunoreactive bands were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, USA) using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated IgG secondary antibodies.

Neuronal cell culture (astrocytes and neuronal cells primary culture)

On 19-ED chick embryos, brain was collected and digested with porcine trypsin (0.25% w/v) for 40 min at 37℃. Following single cell suspension, the resulting brain feeder cells were cultured for 2 weeks in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 unit/mL penicillin G-sodium and 100 µg/mL streptomycin sulfate. 8-ED chick embryos were directly incubated in calcium-magnesium free solution (2 mM EDTA in HBSS) for 30 min at 37℃. Following single cell suspension, the cells were plated in the feeder cells-coated plates, and cultured further for the maturation of neuronal cells.

Immunocytochemistry

Cultured brain cells treated with Pb (4.8 and 7 mM for 50 and 100 ppm groups, respectively) and Hg (2.4 and 23 µM for 50 and 80 ppm groups, respectively) for overnight, were then fixed, incubated with anti-tubulin and anti-tau antibody and subsequently visualized with ABC reagent (Vector Laboratory, Burlingame, USA). All imaging data were processed with light-microscopy (×200) (PC-2, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means±SEM with the number of individual experiments presented in the figure legends. Significance was tested using analysis of variance with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test (P<0.05) as indicated in figure legends.

Results

Direct administration of inorganic lead and mercury in chick embryo resulted in the accumulation of inorganics in neonatal brain

To determine whether inorganic metals injected into yolk sac in early developmental stage were still remained and accumulated in adult stage, Pb and Hg were directly administrated into yolk sac on embryonic day 6, and the concentrations of remained lead and mercury in neonatal brain were determined. As shown in Figure 1B, administration of 50 (25 mg/500 mL) and 100 ppm (50 mg/500 mL) of lead resulted in the accumulation of 4.73±0.03 and 6.87±0.19 mM of lead in neonatal brain, respectively. On the other hand, administration of 50 (25 mg/500 mL) and 80 ppm (40 mg/500 mL) of mercury resulted in the accumulation of 1.77±0.61 and 17.22±5.62 mM of mercury in neonatal brain, respectively (Figure 1B). These results strongly indicate that administrated lead and mercury in early developmental stage were accumulated and still detectable in neonatal brain.

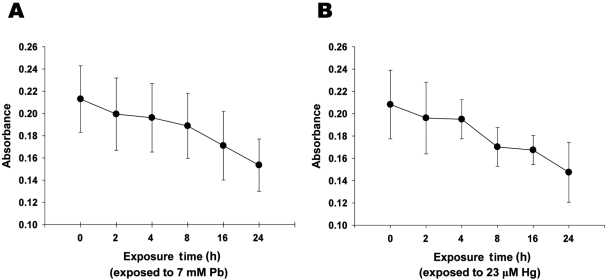

Lead and mercury treatment resulted in the cytotoxicity of primary neuronal cells

To evaluate the effect of inorganic treatment on the viability of adult neuronal cell, MTT colorimetric assay was next performed. Treatment of neuronal cells with lead (7 mM) or mercury (23 µM) for 24 h resulted in ~27.9 and ~29.2% reductions in metabolic cell viability, respectively (Figures 2A and 2B). It is noteworthy that the concentration of lead and mercury treated in neuronal cells were determined based on the concentrations of metals, which were detectable in neonatal brain (Figures 1A and 1B). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that accumulated lead and mercury in neonatal brain could result in the substantial neuronal cell death.

Figure 2.

Lead and mercury induces cytotoxicity of neuronal cells. A-B. Decreased cell viability with the treatment of Pb (A) and Hg (B). Neuronal cells were treated with Pb (7 mM) and Hg (23 µM) for overnight, and MTT colorimetric assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. All data represent three independent experiments, each carried out in triplicate, and significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test, where ** represents P<0.05 vs control.

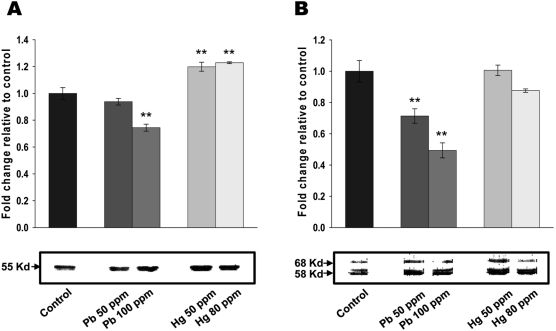

Lead and mercury treatment resulted in the cytoskeletal reorganization of neonatal brain

Interactions between metal salts and cytoskeletal proteins [8] led us to consider the potential involvement of cytoskeletal reorganization for lead and mercury-mediated cytotoxicity in neonatal brain. As shown in Figure 3A, administration of lead (100 ppm) in early developmental stage of chick embryo resulted in the significantly reduced tubulin expression. Administration of 50 ppm lead also resulted in the decreased tubulin expression, however, it didn't reached to the statistically significant point. On the other hand, both 50 and 80 ppm of mercury increased tubulin expression. The effects of lead and mercury on microtubule-associated protein, tau was next determined. As shown in Figure 3B, both 50 and 100 ppm of lead led to the significant reduction of tau expression, whereas mercury didn't show any significant effect on tau expression. Taken together, these results strongly suggest that lead and mercury regulates cytoskeletal reorganization by modulating the levels of tubulin and/or tau expression.

Figure 3.

Lead and mercury modulate cytoskeletal reorganization in neonatal brain. (A-B) Effect of lead and mercury on tubulin (A) and tau (B) expression. Indicated concentration of inorganic lead or mercury were injected into yolk sac on 6-ED. On day 20, total cellular extracts were isolated from neonatal brain and Western blot analyses performed with antibodies against tubulin or tau. Western blots were quantified using densitometric analysis, and values expressed relative to control. Western blots are representative of n=3, and significance was tested using ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post-hoc test, where ** represents P<0.05 vs control.

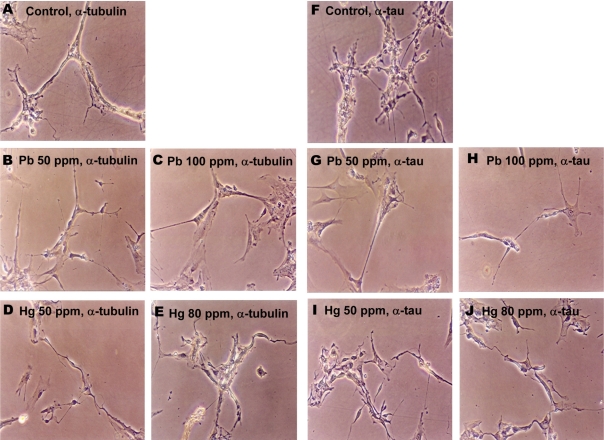

Lead and mercury treatment resulted in the reorganization of cytoskeleton in primary neuronal cells

The effects of lead and mercury treatment on the expression of cytoskeletal protein in neuronal cells were assessed by immunocytochemistry. Since administration of lead or mercury resulted in the accumulation of 4.70-7.06 mM of lead or 1.16-22.84 mM of mercury in neonatal brain, respectively (Figure 1), neuronal cells were treated with corresponded amounts of lead or mercury; 4.8 and 7 mM of lead for 50 and 100 ppm, 2.4 and 23 M of mercury for 50 and 80 ppm, respectively. Lead- and mercury-treated primary neuronal cells tended to show reduced number of axons and dendrites as well as shrinked phenotype, compared to non-treated control (Figure 4). Additionally, lead and mercury induced similar pattern of expression of cytoskeletal proteins; lead-treated cells tended to show reduced tubulin and tau expression, whereas mercury-treated cells showed increased tubulin expression.

Figure 4.

Lead and mercury modulate cytoskeletal reorganization in neuronal cells. Neuronal cells were treated with Pb (4.8 and 7 mM for 50 and 100 ppm groups, respectively) and Hg (2.4 and 23 µM for 50 and 80 ppm groups, respectively) for overnight, and immunocytochemical staining was performed using antibody against tubulin (A-E) or tau (F-J).

Discussion

Lead and mercury are environmental neurotoxicants causing toxic effects on the CNS. Over the past few years, considerable progress has been made in the understanding of molecular mechanisms for the cytotoxic effects of neurotoxins, some of which, the alterations of neurotransmitter homeostasis and cell destruction [2,9,10]. Additionally, exposure to environmental toxicants could be a critical determinant in the etiology of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's [11] and Parkinson's diseases [12]. Intriguingly, neurotoxic effects of lead and mercury shown to be development-dependent, suggesting a distinct response between children and adults [13-15]. However, there is no rigorous way to determine their effects in an early developmental stage. Neuronal cell cultures have been extensively used to evaluate and identify the underlying molecular mechanisms involved in cytotoxic effects of neurotoxins [9,16]. There has been therefore tremendous demand to employ several model systems in order to access the inherent effect of neurotoxins in early developmental stage. In the present study, inorganic metals were directly administrated into the yolk sac to determine neurotoxic effect of inorganic lead and mercury in an early developmental stage. Direct administration of inorganics in early developmental stage resulted in ~6.87% accumulation of lead and ~0.02% accumulation of mercury in neonatal brain, respectively (Figure 1). Mercury found to be accumulated less in adult brain, compared with lead, potentially due to the high affinity binding of ovalbumin to mercury [17].

Cytotoxicity of lead is originated from Ca2+-mimetic action of Pb2+ in many cellular processes, although its' substitutionary characteristics is not the only one explanation for the resulting toxic effect. In normal physiological status, Pb2+ can be uptaken by excitable cells through the activation of voltage-sensitive Ca2+ channels [18,19]. Pb2+ uptake leads to the impaired intracellular Ca2+ concentration, resulting in abnormal neurotransmitter release. Neurotoxic effect of lead was shown to affect cerebrovascular endothelial cells, astroglia and oligodendroglia. Additionally, uptake of lead into CNS through blood-brain barrier (BBB) is due to the Ca2+-mimetic action of Pb2+ [18,20]. High concentrations (>4 mM) of lead exerts deleterious effect on BBB, resulting in acute encephalopathy with brain edema [21]. In the present study, approximately 20% of chick embryos in 100 ppm of lead-treated group developed brain edema (data not shown). The direct neurotoxic actions of lead include apoptosis triggered by impaired intracellular Ca2+ concentration. Cells exposed to lead show a marked accumulation of Ca2+, and sustained Ca2+ accumulation stimulates persistent depolarization of mitochondrial membrane, resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction. Constant opening of the mitochondrial transition pores resulted in cytochrome C release, accompanied with the activation of multiple subtypes of caspases, leading to the cleavage of downstream death effector proteins [21,22]. Neurotoxicity of inorganic mercury in cellular level is also derived from the alteration of Ca2+ signaling pathway [23]. Similar to the neurotoxic exposure to Pb2+, Hg2+ increases the voltage-dependent Ca2+ current through the activation of L-type calcium channel, resulting in enhanced Ca2+ responses to depolarization. Exposure of primary astrocytes and neurons of dorsal root ganglia to inorganic mercury reduced glutamate and nerve fiber growth, respectively [9,24]. In the present study, both lead and mercury induced the cytotoxicity of primary neuronal cells (Figure 2), and it was associated with the modulation of cytoskeletal protein expression (Figures 3 and 4).

Tau plays a pivotal role in regulating microtubule networks in neurons [25], and phosphorylated tau by protein kinase A (PKA) binds to tubulin and promotes tubulin assembly [26]. In earlier study, it was demonstrated that lead disrupted and depolymerized microtubule assembly in vivo as well as in vitro [27,28]. On the other hand, mercury disrupted membrane structure and inhibited linear growth rates of nerve tissues [29]. Both lead and mercury inhibited the protein kinase C (PKC) activity including the basal PKC activity at micromolar concentrations in a concentration-dependent manner [30]. In the present study, lead decreased the expressions of both tubulin and tau, whereas mercury increased tubulin expression (Figures 3 and 4). The distinct responsiveness of these cytoskeletal proteins to lead and mercury implies the presence of unique underlying mechanisms on respective neurotoxicant.

Finally, in view of the increasing evidence of disease related with neurotoxic adverse effect mediated by inorganic lead and mercury, it will be intriguing to establish a clearer understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the neurotoxicity, in order to identify reagents that can slow or block this process.

Acknowledgments

These studies were generously supported by a research funding from Konkuk University.

References

- 1.Manzo L, Castoldi AF, Coccini T, Rossi AD, Nicotera P, Costa LG. Mechanisms of neurotoxicity: applications to human biomonitoring. Toxicol Lett. 1995;77:63–72. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fitsanakis VA, Aschner M. The importance of glutamate, glycine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid transport and regulation in manganese, mercury and lead neurotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2005;204:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2004.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taber KH, Hurley RA. Mercury exposure: effects across the lifespan. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;20:iv-389. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2008.20.4.iv. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baranowska-Bosiacka I, Gutowska I, Marchetti C, Rutkowska M, Marchlewicz M, Kolasa A, Prokopowicz A, Wiernicki I, Piotrowska K, Baskiewicz M, Safranow K, Wiszniewska B, Chlubek D. Altered energy status of primary cerebellar granule neuronal cultures from rats exposed to lead in the pre- and neonatal period. Toxicology. 2011;280:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reddy GR, Zawia NH. Lead exposure alters Egr-1 DNA-binding in the neonatal rat brain. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:791–795. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(00)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidson PW, Myers GJ, Weiss B. Mercury exposure and child development outcomes. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1023–1029. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agemian H, Sturtevant DP, Austen KD. Simultaneous acid extraction of six trace metals from fish tissue by hot block digestion and determination by atomic absorption spectrometry. Analyst. 1980;105:125–130. doi: 10.1039/an9800500125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thier R, Bonacker D, Stoiber T, Böhm KJ, Wang M, Unger E, Bolt HM, Degen G. Interaction of metal salts with cytoskeletal motor protein systems. Toxicol Lett. 2003;140-141:75–81. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(02)00502-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albrecht J, Matyja E. Glutamate: a potential mediator of inorganic mercury neurotoxicity. Metab Brain Dis. 1996;11:175–184. doi: 10.1007/BF02069504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savolainen KM, Loikkanen J, Eerikäinen S, Naarala J. Interactions of excitatory neurotransmitters and xenobiotics in excitotoxicity and oxidative stress: glutamate and lead. Toxicol Lett. 1998;102-103:363–367. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(98)00233-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toimela TA, Tähti H. Effects of mercury, methyl mercury and aluminium on glial fibrillary acidic protein expression in rat cerebellar astrocyte cultures. Toxicol In Vitro. 1995;9:317–325. doi: 10.1016/0887-2333(95)00002-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gorell JM, Johnson CC, Rybicki BA, Peterson EL, Kortsha GX, Brown GG, Richardson RJ. Occupational exposure to manganese, copper, lead, iron, mercury and zinc and the risk of Parkinson's disease. Neurotoxicology. 1999;20:239–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Counter SA, Buchanan LH. Mercury exposure in children: a review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2004;198:209–230. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2003.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monnet-Tschudi F, Zurich MG, Schilter B, Costa LG, Honegger P. Maturation-dependent effects of chlorpyrifos and parathion and their oxygen analogs on acetylcholinesterase and neuronal and glial markers in aggregating brain cell cultures. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;165:175–183. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.8934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zurich MG, Eskes C, Honegger P, Bérode M, Monnet-Tschudi F. Maturation-dependent neurotoxicity of lead acetate in vitro: implication of glial reactions. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:108–116. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morken TS, Sonnewald U, Aschner M, Syversen T. Effects of methyl mercury on primary brain cells in mono- and co-culture. Toxicol Sci. 2005;87:169–175. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards MP, Packard MJ. Mineral metabolism in avian embryos. Poult Avian Biol Rev. 1996;7:143–161. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerper LE, Hinkle PM. Lead uptake in brain capillary endothelial cells: activation by calcium store depletion. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1997;146:127–133. doi: 10.1006/taap.1997.8234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Legare ME, Barhoumi R, Hebert E, Bratton GR, Burghardt RC, Tiffany-Castiglioni E. Analysis of Pb2+ entry into cultured astroglia. Toxicol Sci. 1998;46:90–100. doi: 10.1006/toxs.1998.2492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dyatlov VA, Platoshin AV, Lawrence DA, Carpenter DO. Lead potentiates cytokine- and glutamate-mediated increases in permeability of the blood-brain barrier. Neurotoxicology. 1998;19:283–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silbergeld EK. Mechanisms of lead neurotoxicity, or looking beyond the lamppost. FASEB J. 1992;6:3201–3206. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.6.13.1397842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bressler J, Kim KA, Chakraborti T, Goldstein G. Molecular mechanisms of lead neurotoxicity. Neurochem Res. 1999;24:595–600. doi: 10.1023/a:1022596115897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rossi AD, Larsson O, Manzo L, Orrenius S, Vahter M, Berggren PO, Nicotera P. Modifications of Ca2+ signaling by inorganic mercury in PC12 cells. FASEB J. 1993;7:1507–1514. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.15.8262335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miura K, Himeno S, Koide N, Imura N. Effects of methyl mercury and inorganic mercury on the growth of nerve fibers in cultured chick dorsal root ganglia. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2000;192:195–210. doi: 10.1620/tjem.192.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taniguchi T, Kawamata T, Mukai H, Hasegawa H, Isagawa T, Yasuda M, Hashimoto T, Terashima A, Nakai M, Mori H, Ono Y, Tanaka C. Phosphorylation of tau is regulated by PKN. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10025–10031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tseng HC, Lu Q, Henderson E, Graves DJ. Phosphorylated tau can promote tubulin assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9503–9508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann HP, Faulstich H, Hansch GM, Doenges KH, Stournaras C. The interaction of triethyl lead with tubulin and microtubules. Mutat Res. 1988;201:293–302. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(88)90018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roderer G, Doenges KH. Influence of trimethyl lead and inorganic lead on the in vitro assembly of microtubules from mammalian brain. Neurotoxicology. 1983;4:171–180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leong CC, Syed NI, Lorscheider FL. Retrograde degeneration of neurite membrane structural integrity of nerve growth cones following in vitro exposure to mercury. Neuroreport. 2001;12:733–737. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103260-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajanna B, Chetty CS, Rajanna S, Hall E, Fail S, Yallapragada PR. Modulation of protein kinase C by heavy metals. Toxicol Lett. 1995;81:197–203. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(95)03433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]