Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a proinflammatory cytokine, plays a key role in the pathogenesis of many inflammatory diseases, including arthritis. Neutralization of this cytokine by anti-TNF-α antibodies has shown its efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and is now widely used. Nevertheless, some patients currently treated with anti-TNF-α remain refractory or become nonresponder to these treatments. In this context, there is a need for new or complementary therapeutic strategies. In this study, we investigated in vitro and in vivo anti-inflammatory potentialities of an anti-TNF-α triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO), as judged from effects on two rat arthritis models. The inhibitory activity of this TFO on articular cells (synoviocytes and chondrocytes) was verified and compared to that of small interfering RNA (siRNA) in vitro. The use of the anti-TNF-α TFO as a preventive and local treatment in both acute and chronic arthritis models significantly reduced disease development. Furthermore, the TFO efficiently blocked synovitis and cartilage and bone destruction in the joints. The results presented here provide the first evidence that gene targeting by anti-TNF-α TFO modulates arthritis in vivo, thus providing proof-of-concept that it could be used as therapeutic tool for TNF-α-dependent inflammatory disorders.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, inflammatory, and systemic autoimmune disorder1 characterized by inflammation of synovial membranes and destruction of cartilage and bone.2 Although the etiology of RA remains unclear, the disease is associated with immunological abnormalities, and a variety of inflammatory cytokines are critically involved in its progression. In particular, key cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and IL-6 (IL-6)3 have been shown to display potent proinflammatory actions contributing to the pathogenesis of RA.4 TNF-α is constitutively produced by the synovial tissue and its expression is highly regulated by stabilizing/destabilizing proteins.5 This mediator functions upstream of the cytokine cascade and plays significant role in the induction of synovitis, as revealed in numerous in vitro and in vivo studies,6,7,8 providing an efficient target for human RA treatment.9,10 Anti-TNF-α therapies are now widely used clinically11,12 and their benefits are well recognized. Nonresponding patients however remain and side effects have been described, particularly with opportunistic infections such as tuberculosis.13 New or complementary inhibition strategies are being investigated. Identifying mechanisms that target upstream inhibition, such as TNF-α mRNA or gene, offer conceptual advantages over existing therapies. Indeed, lower number of potential targets is investigated as compared with that for the antibodies and consequently, side effects consecutive to repetitive injections of large amounts of proteins with available treatments could be limited. Moreover, preventing gene transcription is expected to bring down the mRNA concentration in a more efficient and long-lasting way.

In this context, recent advances on gene silencing using oligonucleotides have received considerable attention in rheumatology14 because they provide a rational way to design sequence-specific ligands of nucleic acids. Different strategies can be used to target a sequence in a nucleic acid; of particular interest are RNA interference (small interfering RNA (siRNA), targeting specific mRNAs) and triplex-forming oligonucleotides (TFO, targeting gene promoter).

RNA interference is a naturally occurring gene silencing mechanism used by mammalian cells to control endogenous genes' expression, this mechanism is of great interest for developing therapies based on inhibition of gene function.15,16 Recent studies have proven the success of siRNA in targeting specific protein in vitro6,8 and in vivo.17,18 Recently, siRNA targeting TNF-α was shown to modulate disease severity and inhibit gene expression in electrotransferred knee joints of arthritic animals.7,19 On the other hand, TFO molecules are 12–28 long oligonucleotides20 which recognize the double-helical DNA by sequence-specific binding, due to Hoogsteen or reverse-Hoogsteen hydrogen bounding.21,22 The triplex-forming molecule inserts in the major groove if one strand of the double helix is composed of purines at the binding site. Purine-rich tracts are frequently found in gene promoter regions23 and TFOs directed against these regulatory sites have been shown to selectively reduce transcription of the targeted genes, likely by interfering with transcriptional activators and/or the formation of initiation complexes.24,25 A major drawback of this kind of gene inhibition is a quick degradation of TFO26,27,28 which prevented their use as therapeutic agents. Various chemical modifications have been developed to improve their resistance to degradation and enhance their binding. The first of these was the use of phosphorothioates bounds. Nevertheless, despite their use in clinical trials for many years, problems are encountered including its nonspecific binding to some cationic proteins,29 leading to undesired side effects. Methylphosphonate is another type of modification where a nonbridging oxygen atom is replaced by a methyl group in the DNA phosphodiester skeleton. Methylphosphonates have the ability to penetrate cells due to their neutral charge and they do resist to degradation.30 To date, no data have been published about TNF gene targeting via triple helix formation, and especially in arthritic models.

In this study, we investigated whether TFO employed as antigene strategy could be an alternative to antisense technology in silencing TNF activation during articular inflammation. In a first step, we investigated the proof-of-concept in vitro, on IL1β/LPS activated chondrocytes/synoviocytes in demonstrating that TFO directed against TNF-α promoter was at least as efficient than TNF-α siRNA. In a second step, we confirmed this beneficial approach via intra-articular (i.a.) delivery of TNF-α siRNA and methylphosphonates TFO during an acute reactional model of rat arthritis dedicated to NSAID screening. Finally, we assessed the anti-inflammatory and structural influence of this i.a. anti-TNF-α TFO during a pure immunologic model of rat chronic monoarthritis.

Results

In vitro studies

Silencing of IL-1β and LPS-induced TNF-α expression by siRNA and TFO in articular cells. Cellular toxicity of TFO and siRNA was assessed in both synoviocytes and chondrocytes using tetrazolium-based viability and Lactate Dehydrogenase assay. With the Lactate Dehydrogenase assay, we observed that the viability of articular cells (chondrocytes and synoviocytes) was maintained throughout the 72-hours culture period whatever the oligonucleotide and the concentration (siRNA and TFO, range from 1 to 100 nmol/l) (Supplementary Figure S1). With the MTT assay, we showed that, with the same oligonucleotide concentration and length of exposure, no significant variations in chondrocyte and synoviocyte mitochondrial activity were observed. These results underlined the fact that cellular viability was not affected by the use of these two oligonucleotides.

We then performed a TNF-α mRNA induction kinetic study following IL-1β stimulation (10 ng/ml) and observed that the TNF-α mRNA level reached a maximum of induction between 2 and 4 hours of stimulation, for both synoviocytes and chondrocytes (Supplementary Figure S2). We also observed a significant induction of IL-1β, IL-6, cox-2, and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNos) mRNA levels. Cox-2 expression was induced first, followed by TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β, and iNos. All five genes were significantly induced after 4 hours of stimulation. Consequently, further analyses of mRNA expression profile on in vitro cultured articular cells were assessed after 4 hours of IL-1β stimulation (10 ng/ml).

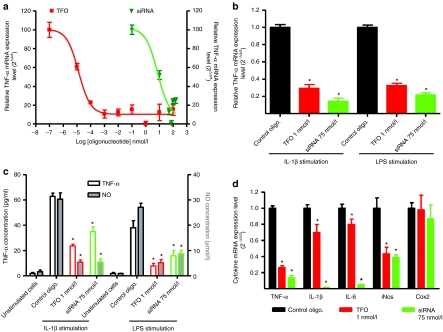

Preventive exposure of rat synoviocytes with TFO and siRNA significantly inhibited IL-1β-induced TNF-α expression in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1a) (up to a threshold of maximal concentration). The highest inhibition was observed at 1 nmol/l for TFO, where a 72 ± 2.1% inhibition in the mRNA expression level was observed, and at 75 nmol/l of siRNA with 82 ± 3.1% inhibition. The inhibition folds observed in the TNF-α mRNA level with siRNA and TFO were identical with the two different inflammation inducers (IL-1β and lipopolysaccharides (LPS)) (Figure 1b). We also assessed TFO and siRNA efficacy in chondrocytes (Supplementary Figure S3) and observed that the inhibition was more pronounced than in synoviocytes with a maximum inhibition of 95% for siRNA and 86% for TFO.

Figure 1.

In vitro evaluation of triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) and small interfering RNA (siRNA) specifically designed to target rat tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Inhibition of TNF-α mRNA was assessed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis of transfected (with TFO or siRNA) rat P3 synoviocytes 4 hours after challenge with (a) interleukin-1β (10 ng/ml) or (b) lipopolysaccharide (LPS). (c) TNF-α and nitric oxide (NO) released in supernatants were assessed 18 hours after inflammation induction using ELISA and GRIESS method, respectively. (d) Biological effects of TNF-α inhibition by oligonucleotides (TFO and siRNA) on proinflammatory cytokines mRNA expression levels (IL-1β, IL-6, iNos, and cox-2). Levels were assessed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis of transfected (with TFO or siRNA) rat P3 synoviocytes 4 hours after challenge with interleukin-1β (10 ng/ml). Nontargeting siRNA and TFO were used as control and RT-qPCR results presented for anti-TNF-α TFO and siRNA are normalized to these controls. Results are representative of three independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. of nine samples.

The inhibition folds observed in mRNA expression were confirmed at the protein level with the assessment of TNF-α released into supernatants of the cultured synoviocytes (Figure 1c). Inhibition of the release of TNF-α into the supernatants with TFO at 1 nmol/l and siRNA at 75 nmol/l was respectively 62.2 ± 2.1% and 44.2 ± 5.8%. We also assessed nitric oxide (NO) released into the supernatants and observed a significant decrease in NO secretion as a result of preventive transfection of both anti-TNF-α oligonucleotides. There was an ~80% decrease in NO secretion by cultured synoviocytes with both anti-TNF-α oligonucleotides regardless of which inflammation inducer (LPS or IL-1β) was used.

Oligonucleotide-mediated TNF-α inhibition down regulates additional cytokines. We also assessed the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, iNos, and cox-2, proinflammatory mediators that are greatly induced during inflammatory processes (under IL-1β and LPS stimulation). mRNA expression was determined by quantitative real-time PCR (after 4 hours of stimulation), following transfection of IL-1β-stimulated articular cells either with anti-TNF-α oligonucleotides or with control TFO and siRNA. The use of control TFO and siRNA did not alter the expression of cytokines mRNAs. In contrast, TNF-α inhibition was accompanied by a significant decrease in IL-1β, IL-6, and iNos expression whereas cox-2 levels remained stable (Figure 1d), a trend that was found with both siRNA and TFO. In addition, the decrease appeared to be greater when TNF-α inhibition was higher than 70%.

In vivo studies

To confirm the in vitro inhibitory effect of TNF-α siRNA and TFO observed on the TNF mediated inflammation, their anti-inflammatory efficacy was further investigated in rats with two experimental arthritis models. First, an acute arthritis model (induced by an i.a. injection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis walls (MbT), which is a useful model for primary evaluation of the anti-inflammatory efficacy of treatments was used. Results showed the greater efficacy of the TFO strategy. Consequently, we then used a chronic experimental arthritis model (induced by methylated bovine serum albumin (mBSA), after systemic immunization), which is an immune-mediated joint inflammation with histopathological events similar to human RA, in order to accurately evaluate the anti-inflammatory potential of TFO.

Tissue distribution of Cy 3′ labeled TFO in articulation after i.a. injection. We first investigated the TFO tissue distribution tissue after i.a. injection with Cy 3′ labeled TFO. Confocal microscopy analysis of articular tissues revealed that TFO was mainly located in synovial membranes, particularly in sublining cells (Figure 2a). Moreover, labeled TFO was present in the superficial and intermediate zones in both patellae and femorotibial articular cartilage of rat knees.

Figure 2.

Triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) tissue distribution and time course of acute arthritis-related changes in rats. (a) Confocal microscopy images of cartilage and synovial membrane from rats intra-articularly injected with 10 µg of Cy 3′ TFO labeled (×10). (b) Time course of arthritis-related changes in rat with Mycobacterium tuberculosis walls-induced arthritis preventively treated or no with 10 µg of anti-TNF-α oligonucleotides [TFO or small interfering RNA (siRNA)] or control oligonucleotide (sham = naive rats, control oligo. = arthritic rats preventively injected with 10 µg of control oligonucleotide, TFO treated = arthritic rats preventively injected with 10 µg of anti-TNF-α TFO, siRNA treated = arthritic rats preventively treated with 10 µg of anti-TNF-α siRNA). Joint circumference of rat knees was estimated from joint width. (c) Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), (d) IL-1β, iNos, vEGF, and MMP13 mRNA expression level in synovial membrane from arthritic rats preventively treated with 10 µg of TFO or siRNA (24 hours after arthritis induction). Levels were assessed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-PCR analysis; results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. of 24 samples (experiment was made three times with eight rats per group in each one). (e) Assessment of TNF-α and NO secretion in synovial fluid from rats. Levels were measured 2 days after arthritis induction by ELISA and GRIESS method for TNF-α and NO, respectively. (f) Assessment of matrix synthesis in patellar chondrocytes from rats (treated or not with TFO or siRNA), 2 days after arthritis induction. Proteoglycan synthesis was measured by Na235SO4 incorporation in patellar cartilage. oligo., oligonucleotide.

Increased improvement of acute arthritis upon anti-TNF-α TFO treatment compared with siRNA

Clinical parameters. Rats received an i.a. preventive injection of 10 µg of anti-TNF-α oligonucleotide (TFO or siRNA) 24 hours before arthritis induction (local injection of MbT). The quantity of 10 µg was chosen considering previous studies using local injection of oligonucleotides in arthritis models.8 We evaluated oligonucleotides efficacy by assessing clinical (joint swelling, body weight), biochemical (anabolism loss in cartilage, cytokines levels) and histological (synovial membrane, cartilage, and bone) parameters. All animals developed first signs of arthritis within 7 hours of intra-articular (i.a.) injection of MbT. Continuous joint swelling was observed in sensitized knees of arthritic rats, which reached a peak at 24 hours, followed by a progressive decrease (Figure 2b). i.a. preventive injection with TFO or siRNA significantly decreased joint swelling by respectively 43.7 ± 4.3% and 28.6 ± 2.9% at 24 hours vs. control oligonucleotide. This inhibition was significantly higher with the TFO preventive injection and continued for 72 hours after injection (Figure 2b) (50% inhibition), when the effect on joint swelling seen initially with siRNA ended. The reduction in body-weight gain observed in arthritic rats was also limited by the preventive injection of TFO (Supplementary Figure S4).

Assessment of cytokines expression in rat knees. At 24 hours after arthritis induction, we evaluated the induction of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α, IL-1β, iNos, MMP13, and vEGF in synovial membranes of arthritic rats. The preventive injection of anti-TNF-α siRNA or TFO decreased TNF-α mRNA levels by 53.1 and 63.8%, respectively (Figure 2c). Nevertheless, the inhibition induced by the use of siRNA did not significantly affect the mRNA expression levels of IL-1β, vEGF, iNos, and MMP13 in synovial membranes. On the other hand, the induction of proinflammatory mediators in the synovial membrane (IL-1β, iNos, vEGF, and MMP13) observed in arthritic rats was significantly lower when TFO was injected in a preventive manner (Figure 2e). Results observed in mRNA expression were further confirmed by the inhibition of TNF-α released (79.5% and 36.4% for TFO and siRNA, respectively) into the synovial fluid of treated rats (Figure 2d). Using the GRIESS method, we also showed that NO secretion in synovial fluid was inhibited by preventive injection of either TFO or siRNA (Figure 2d) (62.5 and 53.5%, respectively). Preventive injection of control oligonucleotide showed no significant variations as compared to arthritic rats.

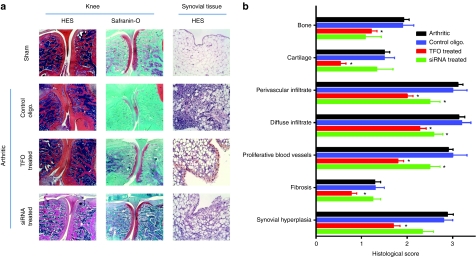

Biochemical parameters and histological assessment. We then investigated the effects of the preventive injection of oligonucleotides on articular bone and cartilage. Loss of proteoglycans observed during the inflammation processes in cartilage was limited by preventive injection of both oligonucleotides (Figure 2f). Rats injected with anti-TNF-α TFO or siRNA had a proteoglycan loss of respectively 77% and 34.4% lower than that in arthritic animals (arthritic rats injected with control oligonucleotide showed a proteoglycan loss similar to arthritic rats). This effect was confirmed by histological grading of knee joints (Figure 3a,b). Cartilage and bone degradation induced by arthritis was significantly reduced by preventive injection of anti-TNF-α, particularly by TFO compared to the control rats. In the first step of arthritis establishment, joint swelling is mainly correlated with synovial hyperplasia. Histologically, we observed that preventive injection of both oligonucleotides limited this hyperplasia, particularly with TFO (Figure 3a). The histological grading of the knee synovium (Figure 3b) confirmed that the preventive injection of both siRNA and TFO significantly reduced fibrosis and global infiltration of synovial tissue. However, the effects were more pronounced with TFO than with siRNA.

Figure 3.

Histological evaluation of anti-TNF-α triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) and small interfering RNA (siRNA) (10 µg) efficiency in an acute arthritis model. (a) Histological sections of joints from Mycobacterium tuberculosis walls-induced arthritic rats preventively injected or not with anti-TNF-α TFO or siRNA or with control oligonucleotide (sham = naive rats, control oligo. = arthritic rats preventively injected with 10 µg of control oligonucleotide, TFO treated = arthritic rats preventively injected with 10 µg of anti-TNF-α TFO, siRNA treated = arthritic rats preventively treated with 10 µg of anti-TNF-α siRNA). Knees were taken 3 days after arthritis induction. Formalin fixed, decalcified, paraffin-embedded, hematoxylin and eosin and safranin-O stained 5 µm sections were assessed for cartilage and bone erosion. Synovial membranes were taken 24 hours after arthritis induction and hematoxylin/eosin stained. Representative images of the different groups are shown. (b) Histological grading of knee synovium, cartilage, and bone lesions in rats developing Mycobacterium walls-induced arthritis and preventively treated or not with anti-TNF-α oligonucleotides (TFO and siRNA). Values are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. of 18 rats per time and group. *P < 0.05 in comparison with control, #P < 0.05 in comparison with arthritic rats. oligo., oligonucleotide; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

Efficiency of anti-TNF-TFO in an immunological experimental chronic arthritis model: clinical and histological evaluation.

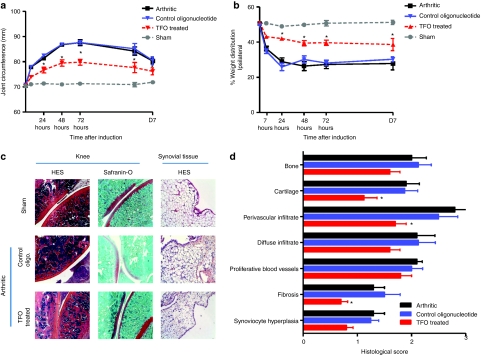

Clinical and structural efficacy of TFO. All sensitized animals developed first signs of antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) within 7 hours after i.a. injection of arthritogen mBSA. Continuous joint swelling was observed in sensitized knees after mBSA injection, which reached a peak after 3 days and then progressively decreased. The preventive injection of anti-TNF-α TFO significantly decreased joint swelling by 48% at day 3 (Figure 4a) and the decrease was maintained until day 7. In parallel, we evaluated hindlimb weight distribution throughout the course of the experiment (Figure 4b). i.a. injection of mBSA in the AIA rats led to a rapid painful response in the ipsilateral sensitized hindlimb causing the animals to redistribute their body weight in favor of the saline injected contralateral limb (Figure 4b). This shift in weight distribution was apparent within the first 24 hours after mBSA injection, and reached a maximal level of incapacitance at 48 hours with rats placing only 25% of their body weight on the sensitized leg (Figure 4b) and continued until day 7. The preventive injection of TFO resulted in a significant correction in body-weight distribution throughout disease establishment whereas injection of control oligonucleotide had no effect in comparison with arthritic rats. These clinical observations were confirmed by histological grading of the knees (synovial membrane, cartilage and bone structure) (Figure 4c,d). Indeed, fibrosis and infiltration in the synovial membrane of treated rats decreased significantly compared to arthritics. A major improvement in bone and cartilage scores (2.0 versus 1.6 and 1.9 versus 1.4, respectively) was also observed in the knee joints of rats preventively injected with TFO.

Figure 4.

Time course of arthritis-related changes in rat with antigen-induced (chronic) arthritis preventively treated or not with anti-TNF-α triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) (sham = naive rats, control oligo. = arthritic rats preventively injected with 10 µg of control oligonucleotide, TFO treated = arthritic rats preventively injected with 10 µg of anti-TNF-α TFO). (a) Joint circumference of rat knees was estimated from joint width. (b) Hindpaw weight-distribution of chronic arthritic and preventively treated rats compared to healthy controls. Data are expressed as percentage of weight distribution onto the sensitized hindlimb. (c) Histological sections of joints from arthritic rats preventively injected or no with anti-TNF-α TFO. Knees were taken 3 days after arthritis induction. Formalin fixed, decalcified, paraffin-embedded, hematoxylin and eosin and safranin-O stained 5 µm sections were assessed for cartilage and bone erosion. Synovial membranes were taken 24 hours after arthritis induction and hematoxylin/eosin stained. Representative images of the different groups are shown. (d) Histological grading of knee synovium, cartilage, and bone in rats developing antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) and preventively treated or no with anti-TNF-α TFO. Rats were immunized with 0.5 g of methylated bovine serum albumin (mBSA) emulsified with complete Freund's adjuvant 21 and 14 days before articular injection (D0) of 0.5 mg of mBSA (sensitized) or saline (contralateral) into the knees. Values are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. of eight rats per time. *P < 0.05 in comparison with control, #P < 0.05 in comparison with arthritic rats. oligo., oligonucleotide; TNF-α, tumor necrosis factor-α.

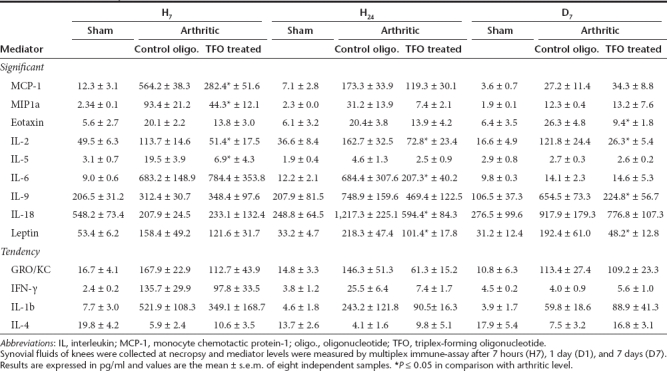

Assessment of cytokines expression in the knee joints. We assessed mRNA expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, iNos, vEGF, and MMP13 in the synovial membrane of the rats and observed a decrease in all these proinflammatory mediators in TFO-treated rats compared with arthritics and control oligonucleotide-injected rats. To confirm these results, levels of 24 inflammatory mediators were assessed in the synovial fluid of the rats using a multiplex beads immunoassay (Table 1). In the early phase of arthritis establishment (within 7 hours), levels of chemokines monocyte chemotactic protein-1, MIP-1α, IL-2, and IL-5 significantly decreased in TFO-treated rats in comparison with arthritic rats. At 24 hours after arthritis induction, IL-2, IL-6, IL-18, and leptin levels were also significantly decreased. At day 7, levels of eotaxin, IL-2, IL-9, and leptin remained significantly lower in the synovial fluid of treated rats than in arthritics. Furthermore, levels of GRO/KC, IL-1β, IL-4, and interferon-γ showed mild but not significant modifications in favor of a positive evolution of arthritis (decrease in GRO/KC, IL-1β, and interferon-γ and limitation of decrease in IL-4).

Table 1. Synovial fluid expression profile of mediators in joints of rats developing antigen-induced arthritis (AIA) and preventively treated or not with intra-articular injection of TFO.

Discussion

In the >10 years since the beginning of targeted therapies to inhibit TNF, anti-TNF-α antibodies and soluble anti-TNF receptors have been key therapeutic agents in the treatment of active RA and other inflammatory diseases. Despite their benefits, their use is not without risks, with prominent side effects as a consequence of frequent injections of large amounts of the proteins, such as the risk of serious infections, malignancies, and lymphomas, as well as of developing adverse immune reactions.31 Our findings enabled us to describe a novel approach to reduce inflammation during arthritis using i.a. targeted oligonucleotides TFO mediated TNF-α silencing. The TFO strategy, targeting TNF-α expression at the transcriptional stage, offered both protection and relief from acute arthritis in rat knee compared to RNA interference (which acts at a post-transcriptional step). Additionally, TFO was shown to exert anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive, and chondroprotective effects in a chronic rat model of autoimmune antigen arthritis closely mimicking joint RA.

The use of TFO in gene silencing was developed with the idea that short nucleotides in certain sequences are found only once in the entire genome and for that reason, gene silencing with specific TFO could be highly specific. Moreover, low doses of this anti-TNF agent should be efficient, which could reduce the side effects observed with currently available systemic anti-TNF agents. In the first step, to assess the potential of an anti-TNF-α TFO, we compared its efficacy and safety to that of a classical siRNA strategy. The in vitro studies first demonstrated that the use of anti-TNF-α TFO oligonucleotides, like siRNA, has no obvious deleterious effects on articular cells. In this study, we focused on the response of synoviocytes given that inflammatory mediators produced during inflammatory arthritides mainly follow synovial membrane inflammation and proliferation.32 Interestingly, we showed that the amounts of TFO needed to obtain a significant inhibition are very low compared to siRNA, underlining the potential advantage of the TFO strategy. Another advantage is the high genomic targeting specificity of TFOs,33 supported by the observation that TFO designed for rat cells had no efficacy on human cells and reciprocally. Our results also showed that maximum inhibition was higher with siRNA than with TFO (82% versus 72%). This difference may be due to the degradation of pre-existing mRNA by siRNA while TFO is only able to stop neosynthesis. Indeed, TNF-α is constitutively expressed but highly regulated at the mRNA level in order to allow rapid mobilization.34

The in vitro study also revealed that TNF-α inhibition by both siRNA and TFO led to a significant decrease in the expression of IL-1β, IL-6, and iNos messengers after only 4 hours of stimulation, meaning it was not the consequence of the decrease in TNF-α protein. The fact that this phenomenon was observed with both strategies and that control oligonucleotides did not generate such a decrease indicates that our results were most likely not due to oligonucleotide aspecificity. Moreover, after cloning IL-6 promoter, we showed that TFO had no influence on IL-6 gene expression (Supplementary Figure S5), whereas this gene was downregulated after 4 hours of stimulation in our in vitro experiments. Inflammatory mediators and particularly TNF-α mRNAs stability is highly regulated by stabilization/destabilization proteins such as TTP, TIA and HuR5 or miRNA.35,36 In addition, common sequences are found on 3′UTR sequences of TNF-α and other decreased messengers.37 Consequently, we suppose that the physical lack of TNF-α mRNA induced either by siRNA or TFO increases the amount of destabilizing proteins available for interaction with similar 3′UTR of other inflammatory mediators “messengers.”

To confirm that these results were not related to the stimulation used, the same experiments were performed using LPS as an inflammation inducer. Cell signaling pathways activated by this stimulation are known to involve transduction processes or different actors from those of IL-1β.38 Inhibition folds observed confirmed the independence of these side effects on the inflammation pathways involved. The mechanisms by which oligonucleotides directed against TNF-α also affect the messengers of other cytokines will be investigated in upcoming studies.

In addition, the possibility to target TNF-α expression with siRNA and TFO nucleotides in articular cells enabled us to assess for the first time their efficacy in experimental arthritis models. Previous encouraging results were obtained with much higher systemic daily doses of PEG sTNFR1 (4 mg/kg) during systemic rat adjuvant-induced arthritis and rat collagen-induced arthritis39 with only beneficial influence on paw volume. During rat AIA40 both repeated systemic etanercept (5.5 mg/kg) and infliximab (7 mg/kg) injections significantly attenuated inflammation-induced changes in locomotor and pain-related behavior in rats. These effects were accompanied by a slight but nonsignificant reduction in joint swelling at some points but no gross inflammatory changes.

In the first step of our in vivo studies, we used an acute inflammatory monoarthritis model of the rat knee, which allows quick screening of the anti-inflammatory potential of oligonucleotides. Rats preventively administered (i.a.) with TFO and siRNA exhibited significantly lower arthritic scores than arthritic or control oligonucleotide-treated rats. This was demonstrated by a significant improvement in arthritis symptoms such as joint swelling, expression of proinflammatory cytokines, and articular histological degradation. The efficiency of both approaches showed that it is advisable to inhibit gene expression at an early stage of protein synthesis in articular cells.8,19 Furthermore, we observed that the effects of the TFO injection were much greater than with the same amount of siRNA (10 µg). During this experiment, methylphosphonate TFO (in NaCl 0.9%) was i.a. injected without transfection agent thanks to its neutral charge, while siRNA was combined to in vivo JetPEI for the transfer. In order to compare both strategies in the same conditions, a group of rats was injected with siRNA alone, but no effect on arthritis establishment was observed. This underlines the fact that oligonucleotides vectorisation could be improved.19

The TFO strategy has the advantage of its relatively limited number of targets compared to siRNA, especially under inflammatory conditions. Furthermore, directly targeting the gene promoter aims to limit transcription in the concerned cells, while siRNA targets TNF-α mRNA which continues to be synthesized. Consequently, with the same amount of oligonucleotide, the effects induced by TFO can be last longer. Taking these results into account, we next focused on whether TFO can inhibit or delay clinical manifestations of a chronic autoimmune monoarthritis model.

The TFO was preventively injected into the knee joint 1 day before arthritis induction. A significant therapeutic effect was observed during arthritis establishment. There was marked reduction in the degree of joint inflammation, the decrease in infiltration may be correlated with a decrease in chemokines observed in synovial fluid of rat knees.41 Most interesting was the significant chondroprotective effect, with preservation of cartilage and bone, which was extensively damaged in control arthritic rats. As previously, at the same time, we observed a decrease in IL-1β and 6 levels in synovial fluid, which are known to be involved in progressive cartilage and bone degradation during arthritis.42,43 Primarily due to these anti-arthritic evaluations, we also investigated the distribution of oligonucleotide tissue and showed the ability of methylphosphonate TFO to enter articular cells thanks to its neutral charge. These observations offer promising perspectives concerning TFO delivery. Moreover, an appropriate vehicle, such as nanoparticles,44,45 could be used as a delaying delivery system and would allow systemic injections of TFO.

In conclusion, the results presented here provide the first evidence that i.a. gene targeting by anti-TNF-α TFO modulates arthritis in vivo has a beneficial influence on clinical, pain-related and structural ancillary chondral lesions using much lower doses than classical TNF-α blockade. We showed the effectiveness of siRNA and TFO in modulating both in vitro and in vivo inflammatory processes. Interestingly, silencing was increased with TFO, enabling improved protection of articular components. We extended our findings by demonstrating for the first time that in rats developing arthritis, a preventive injection of anti-TNF-α TFO led to local and systemic TNF-α inhibition associated with improvement of ancillary clinical signs of arthritis. Taken together, these results are promising regarding the use of oligonucleotides and particularly TFOs as a new strategy for therapeutic intervention in inflammatory conditions. In addition, this targeted technique may serve as a tool to study arthritis disease pathways.

Materials and Methods

General overview. Information on reagents, cell culture and treatment, transfections, scoring and assessment for arthritis, histology, assessment of cytokine mRNA expression and of cytokine protein expression, and statistical analysis is provided in Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Animals. All experiments were carried out on male Wistar Han rats (150–175 g) purchased from Charles River Laboratories (L'arbresle, France). All operative procedures were performed by the same surgeon for consistency. The use of animals and the experimental protocols, including that for euthanasia, were as per the national animal care guidelines and were preapproved by a local ethics committee. Arthritis induction and necropsy were performed under general anesthesia, using volatile anesthetics (Aerrane; Baxter SA, Maurepas, France).

Oligonucleotides. Synthetic siRNA duplexes and TFO targeting rat TNF-α gene were synthesized and purchased from Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium). The two sense sequences (sequences A and B) for the siRNA were as follows: A, 5′-GGA-GGA-GAA-GUU-CCC-AAA-U99-3′, B, 5′-AUU-UGG-GAA-CUU-CUC-CUC-C99-3′. TFO sequence was 5′-TCG-AAA-AGG-GGT-GGG-AGA-AGG-3′ with methylphosphonates modifications for in vivo experiments. The control siRNA was a scramble for in vitro experiments and the sequence of nontargeting TFO was 5′-CAT-GGA-GCC-ACA-TTC-ATG-ACC-3′. The sequence of the control oligonucleotide used in in vivo experiments was 5′-TCG-AAA-AGG-GGG-AGA-AGG-3′.

Oligonucleotides injection and arthritis induction. Oligonucleotides TFO and siRNA were injected i.a. 24 hours before arthritis induction with 10 µg of methylphosphonate TFO or 10 µg of siRNA. Methylphosphonate TFO was injected without transfection agent in 50 µl of 0.9% NaCl and siRNA was combined with in vivo-jetPEI (Euromedex, Souffelweyersheim, France) in 50 µl of 0.9% NaCl. Acute MbT-induced arthritis was used in this study as previously described.46 Briefly, arthritis was induced by i.a. injection of 50 µl saline-containing 600 µg MbT (Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany) into the right knee joint. The left knee received 50 µl of 0.9% NaCl in the articular cavity. Control rats (Sham) received 50 µl of 0.9% NaCl in both knees.

For the chronic arthritis model, animals were immunized 21 and 14 days before induction of AIA by subcutaneous injections of 250 µl of a suspension containing 0.5 g of mBSA (Sigma), dissolved in 125 µl of saline and emulsified with 125 µl of complete Freund's adjuvant (2 mg/ml MbT, DIFCO, Detroit, MI) into the flanks. On day 0 (D0), AIA was induced by a single i.a. injection of 0.5 mg of mBSA (50 µl of 10 mg/ml mBSA dissolved in 0.9% NaCl) into the right knee joint; the left knee received 50 µl of 0.9% NaCl. Control rats (Sham) were immunized as previously described but received an i.a. injection of 50 µl of 0.9% NaCl in both knees on D0.

Anti-TNF-α oligonucleotide efficacy was evaluated by assessment of clinical (joint swelling, body weight, and hindlimb body-weight distribution), biochemical (loss of anabolism in cartilage, levels of cytokines expression) and histological (synovial membrane, cartilage, and bone) parameters.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Cellular viability of P3 synoviocytes transfected with either anti-TNF-α TFO or siRNA. Oligonucleotides were transfected at concentrations from 1nM to 100nM and cells were then stimulated with IL-1β 10 ng/mL during 24, 48 or 72 hours. Viability was estimated using the LDH assay. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples. Figure S2. TNF-α mRNA induction kinetic following IL-1β stimulation (10 ng/ml) on rats P3 synoviocytes. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples. Figure S3. In vitro evaluation of anti-TNF-α triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) and small interfering RNA (siRNA). Inhibition of TNF-α mRNA was assessed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of transfected (with TFO (A.) or siRNA (B.)) rat P1 chondrocytes 4 hours after challenge with Interleukin-1 β (10 ng/mL). Non targeting siRNA and TFO were used as control and RT-qPCR results presented for anti-TNF-α TFO and siRNA are normalized to these controls. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples. Figure S4. In vivo evaluation of anti-TNF-α TFO and siRNA efficiency on body-weight gain. Oligonucleotides were preventively injected 24 hours before arthritis induction. Results are expressed in grams (g) as weight difference (weight at considered time – weight at the time of oligonucleotide injection). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 21 samples. Figure S5. Evaluation of anti-TNF-α TFO effect on IL-6 promoter activity. IL-6 promoter was cloned in pGL3 basic vector. Rat P3 synoviocytes were transfected with this construction and anti-TNF-α TFO. IL-1β 10 ng/mL was used as inflammation inducer. Empty pGL3 basic was used as control. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of luciferase activity. Materials and Methods.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the main major initial contribution of Eliane Taillandier and her group, Université Paris-13, who first designed the TFO. The preliminary in vitro results on THP-1 cells were presented as poster by Amr Abid, PhD, at the 61th National Meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Washington, 8–12 November 1997. We thank Dominique Dumas for his assistance with confocal microscopy, David Moulin for critical reading of the manuscript and Michel Thiery for his good care to the animals. Amgen granted part of the in vitro study on articular cells. This work was also supported by grants “Conseil Général de Meurthe et Moselle,” “Communauté Urbaine du Grand Nancy,” “Conseil Régional” and the Contrat de Projet de Recherche Clinique du CHU de Nancy (CPRC 2007 UF 9661). ANR (ANR-07-BLAN-0302-02) payed J.P.'s salary during 2009–2010.

Supplementary Material

Cellular viability of P3 synoviocytes transfected with either anti-TNF-α TFO or siRNA. Oligonucleotides were transfected at concentrations from 1nM to 100nM and cells were then stimulated with IL-1β 10 ng/mL during 24, 48 or 72 hours. Viability was estimated using the LDH assay. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples.

TNF-α mRNA induction kinetic following IL-1β stimulation (10 ng/ml) on rats P3 synoviocytes. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples.

In vitro evaluation of anti-TNF-α triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) and small interfering RNA (siRNA). Inhibition of TNF-α mRNA was assessed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of transfected (with TFO (A.) or siRNA (B.)) rat P1 chondrocytes 4 hours after challenge with Interleukin-1 β (10 ng/mL). Non targeting siRNA and TFO were used as control and RT-qPCR results presented for anti-TNF-α TFO and siRNA are normalized to these controls. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples.

In vivo evaluation of anti-TNF-α TFO and siRNA efficiency on body-weight gain. Oligonucleotides were preventively injected 24 hours before arthritis induction. Results are expressed in grams (g) as weight difference (weight at considered time – weight at the time of oligonucleotide injection). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 21 samples.

Evaluation of anti-TNF-α TFO effect on IL-6 promoter activity. IL-6 promoter was cloned in pGL3 basic vector. Rat P3 synoviocytes were transfected with this construction and anti-TNF-α TFO. IL-1β 10 ng/mL was used as inflammation inducer. Empty pGL3 basic was used as control. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of luciferase activity.

REFERENCES

- Gorman CL., and, Cope AP. Immune-mediated pathways in chronic inflammatory arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2008;22:221–238. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreas K, Lübke C, Häupl T, Dehne T, Morawietz L, Ringe J.et al. (2008Key regulatory molecules of cartilage destruction in rheumatoid arthritis: an in vitro study Arthritis Res Ther 10R9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi M., and, Benucci M. [The role of interleukin-6 in rheumatoid arthritis] Recenti Prog Med. 2008;99:291–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy EH., and, Panayi GS. Cytokine pathways and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:907–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seko Y, Cole S, Kasprzak W, Shapiro BA., and, Ragheb JA. The role of cytokine mRNA stability in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2006;5:299–305. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jing Y, Shishkov A., and, Ponnappa BC. Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α secretion in rat Kupffer cells by siRNA: in vivo efficacy of siRNA-liposomes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1780:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffelers RM, Xu J, Storm G, Woodle MC., and, Scaria PV. Effects of treatment with small interfering RNA on joint inflammation in mice with collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1314–1318. doi: 10.1002/art.20975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoury M, Escriou V, Courties G, Galy A, Yao R, Largeau C.et al. (2008Efficient suppression of murine arthritis by combined anticytokine small interfering RNA lipoplexes Arthritis Rheum 582356–2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Williams RO, Woody JN., and, Maini RN. The transfer of a laboratory based hypothesis to a clinically useful therapy: the development of anti-TNF therapy of rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2004;18:59–80. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2003.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshizaki K. [Pathogenic analysis of chronic inflammatory disease based on the clinical results by IL-6 blocking therapy] Nihon Rinsho Meneki Gakkai Kaishi. 2008;31:104–112. doi: 10.2177/jsci.31.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano V, Quinn M, Conaghan PG, Reece R, Keenan AM, Walker D, Yorkshire Early Arthritis Register Consortium et al. Effect of the early use of the anti-tumor necrosis factor adalimumab on the prevention of job loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1467–1474. doi: 10.1002/art.24106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff M, Kvien TK, Kälvesten J, Elden A., and, Haugeberg G. Adalimumab therapy reduces hand bone loss in early rheumatoid arthritis: explorative analyses from the PREMIER study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1171–1176. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.091264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybar I, Rozborilova E, Zanova E, Micekova D, Solovic I., and, Rovensky J. The effectiveness for prevention of tuberculosis in patients with inflammatory rheumatic diseases treated with TNF inhibitors. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2008;109:164–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chary-Valckenaere I, Porumb H, Taillandier E., and, Pourel J. Oligonucleotides: a new resource in rheumatology. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1998;65:543–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello CC., and, Conte D., Jr Revealing the world of RNA interference. Nature. 2004;431:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nature02872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplen NJ. Gene therapy progress and prospects. Downregulating gene expression: the impact of RNA interference. Gene Ther. 2004;11:1241–1248. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnappa BC, Israel Y, Aini M, Zhou F, Russ R, Cao QN.et al. (2005Inhibition of tumor necrosis factor α secretion and prevention of liver injury in ethanol-fed rats by antisense oligonucleotides Biochem Pharmacol 69569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen DR, Leirdal M., and, Sioud M. Gene silencing by systemic delivery of synthetic siRNAs in adult mice. J Mol Biol. 2003;327:761–766. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00181-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A, Takahashi KA, Mazda O, Terauchi R, Arai Y, Kishida T.et al. (2005Electro-transfer of small interfering RNA ameliorated arthritis in rats Biochem Biophys Res Commun 336903–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenfeld G., and, Miles HT. The physical and chemical properties of nucleic acids. Annu Rev Biochem. 1967;36:407–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.36.070167.002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zon G. Oligonucleotide analogues as potential chemotherapeutic agents. Pharm Res. 1988;5:539–549. doi: 10.1023/a:1015985728434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hélène C., and, Toulmé JJ. Specific regulation of gene expression by antisense, sense and antigene nucleic acids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1049:99–125. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(90)90031-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Gaddis SS, MacLeod MC, Walborg EF, Thames HD, DiGiovanni J.et al. (2007High-affinity triplex-forming oligonucleotide target sequences in mammalian genomes Mol Carcinog 4615–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winters TA. Gene targeted agents: new opportunities for rational drug development. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2000;2:670–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain A, Magistri M, Napoli S, Carbone GM., and, Catapano CV. Mechanisms of triplex DNA-mediated inhibition of transcription initiation in cells. Biochimie. 2010;92:317–320. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2009.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaerman JL, Moureau P, Deldime F, Lewalle P, Lammineur C, Morschhauser F.et al. (1997Antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotides suppress hematologic cell growth through stepwise release of deoxyribonucleotides Blood 90331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickstrom E. Oligodeoxynucleotide stability in subcellular extracts and culture media. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1986;13:97–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(86)90021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar S, Kole R., and, Juliano RL. Stability of antisense DNA oligodeoxynucleotide analogs in cellular extracts and sera. Life Sci. 1991;49:1793–1801. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(91)90480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CA., and, Krieg AM. Problems in interpretation of data derived from in vitro and in vivo use of antisense oligodeoxynucleotides. Antisense Res Dev. 1994;4:67–69. doi: 10.1089/ard.1994.4.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller PS, McParland KB, Jayaraman K., and, Ts'o PO. Biochemical and biological effects of nonionic nucleic acid methylphosphonates. Biochemistry. 1981;20:1874–1880. doi: 10.1021/bi00510a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzeni F., and, Sarzi-Puttini P. Anti-cytokine antibodies for rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2009;10:1204–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner SS, Klotz U, Alscher DM, Mais A, Lauer G, Schweer H.et al. (2004Osteoarthritis of the knee–clinical assessments and inflammatory markers Osteoarthr Cartil 12469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekhoff P, Ceccaldi A, Polverari D, Pylouster J, Pisano C., and, Arimondo PB. Triplex formation on DNA targets: how to choose the oligonucleotide. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12277–12289. doi: 10.1021/bi801087g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohchi C, Noguchi K, Tanabe Y, Mizuno D., and, Soma G. Constitutive expression of TNF-α and -beta genes in mouse embryo: roles of cytokines as regulator and effector on development. Int J Biochem. 1994;26:111–119. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(94)90203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tili E, Michaille JJ, Costinean S., and, Croce CM. MicroRNAs, the immune system and rheumatic disease. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2008;4:534–541. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen I., and, David M. MicroRNAs in the immune response. Cytokine. 2008;43:391–394. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao S., and, Baltimore D. The stability of mRNA influences the temporal order of the induction of genes encoding inflammatory molecules. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:281–288. doi: 10.1038/ni.1699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., and, Verma IM. NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:725–734. doi: 10.1038/nri910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schett G, Stolina M, Dwyer D, Zack D, Uderhardt S, Krönke G.et al. (2009Tumor necrosis factor α and RANKL blockade cannot halt bony spur formation in experimental inflammatory arthritis Arthritis Rheum 602644–2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettger MK, Hensellek S, Richter F, Gajda M, Stöckigt R, von Banchet GS.et al. (2008Antinociceptive effects of tumor necrosis factor α neutralization in a rat model of antigen-induced arthritis: evidence of a neuronal target Arthritis Rheum 582368–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser B, Wolf M, Walz A., and, Loetscher P. Chemokines: multiple levels of leukocyte migration control. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torzilli PA, Bhargava M, Park S., and, Chen CT. Mechanical load inhibits IL-1 induced matrix degradation in articular cartilage. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18:97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Kuwahara Y, Shima Y, Hirano T, Kawai M, Ogawa M.et al. (2009Successful treatment of reactive arthritis with a humanized anti-interleukin-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab Arthritis Rheum 611762–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toub N, Bertrand JR, Malvy C, Fattal E., and, Couvreur P. Antisense oligonucleotide nanocapsules efficiently inhibit EWS-Fli1 expression in a Ewing's sarcoma model. Oligonucleotides. 2006;16:158–168. doi: 10.1089/oli.2006.16.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toub N, Malvy C, Fattal E., and, Couvreur P. Innovative nanotechnologies for the delivery of oligonucleotides and siRNA. Biomed Pharmacother. 2006;60:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2006.07.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonhomme F, Boucheron C, Migliore D., and, Jollès P. Arthritogenicity of unaltered and acetylated cell walls of mycobacteria. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1969;36:317–320. doi: 10.1159/000230752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cellular viability of P3 synoviocytes transfected with either anti-TNF-α TFO or siRNA. Oligonucleotides were transfected at concentrations from 1nM to 100nM and cells were then stimulated with IL-1β 10 ng/mL during 24, 48 or 72 hours. Viability was estimated using the LDH assay. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples.

TNF-α mRNA induction kinetic following IL-1β stimulation (10 ng/ml) on rats P3 synoviocytes. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples.

In vitro evaluation of anti-TNF-α triplex-forming oligonucleotide (TFO) and small interfering RNA (siRNA). Inhibition of TNF-α mRNA was assessed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction analysis of transfected (with TFO (A.) or siRNA (B.)) rat P1 chondrocytes 4 hours after challenge with Interleukin-1 β (10 ng/mL). Non targeting siRNA and TFO were used as control and RT-qPCR results presented for anti-TNF-α TFO and siRNA are normalized to these controls. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 9 samples.

In vivo evaluation of anti-TNF-α TFO and siRNA efficiency on body-weight gain. Oligonucleotides were preventively injected 24 hours before arthritis induction. Results are expressed in grams (g) as weight difference (weight at considered time – weight at the time of oligonucleotide injection). Results are representative of 3 independent experiments and are expressed as the mean ± SEM of 21 samples.

Evaluation of anti-TNF-α TFO effect on IL-6 promoter activity. IL-6 promoter was cloned in pGL3 basic vector. Rat P3 synoviocytes were transfected with this construction and anti-TNF-α TFO. IL-1β 10 ng/mL was used as inflammation inducer. Empty pGL3 basic was used as control. Results are expressed as the mean ± SEM of luciferase activity.