Abstract

Background

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is reported to occur in 12 to 25% of patients who require mechanical ventilation with a mortality rate of 24 to 71%. The endotracheal (ET) tube has long been recognized as a major factor in the development of VAP since biofilm harbored within the ET tube become dislodged during mechanical ventilation and have direct access to the lungs. The objective of this study was to demonstrate the safety and effectiveness of a non-invasive antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) treatment method of eradicating antibiotic resistant biofilms from ET tubes in an in vitro model.

Methods

Antibiotic resistant polymicrobial biofilms of Pseudomonas aerugenosa and MRSA were grown in ET tubes and treated, under standard ventilator conditions, with a methylene blue (MB) photosensitizer and 664nm non-thermal activating light. Cultures of the lumen of the ET tube were obtained before and after light treatment to determine efficacy of biofilm reduction.

Results

The in vitro ET tube biofilm study demonstrated that aPDT reduced the ET tube polymicrobial biofilm by >99.9% (p<0.05%) after a single treatment.

Conclusions

MB aPDT can effectively treat polymicrobial antibiotic resistant biofilms in an ET tube.

Keywords: Ventilator associated pneumonia, biofilms, endotracheal tubes, photodynamic therapy

Introduction

The leading cause of patient death from hospital-acquired infections is pneumonia.1–3 Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a common, significant, life threatening infectious disease that occurs in subjects who are intubated with an endotracheal tube and require mechanical ventilation.1–13 In the US, of the 1.6 million patients per year who require mechanical ventilation, 15% to 25% will develop VAP and 24% to 71% will consequently die of the disease.4–6 VAP is associated with significant mortality and costs the US healthcare industry $1.2 billion dollars annually.2,8,10

The endotracheal tube has long been considered as a potential contributor for the development of VAP.1,6,9–13 Staphylococcus aureus and aerobic gram-negative bacilli are the major pathogens responsible for VAP, accounting for 50–70% of all cases.14,15 Several studies have shown that pathogenic bacteria are capable of adhering to the surface of endotracheal tubes (ETT) to form biofilms.10,12 This phenomenon of biofilm formation has been demonstrated to occur on the interior surface of endotracheal tubes in intubated patients and the subsequent dislodgement of biofilm-protected bacteria into the lungs is considered to be a significant factor in the pathogenesis of VAP.9–13 During suctioning, aggregates of bacteria in biofilms may dislodge into the lower airways.10 Biofilms are considered an important factor predisposing to VAP.8 Only recently has the direct correlation between endotracheal tube inner lumen bacterial load and VAP been demonstrated. BARD, Inc. clinically tested its endotracheal tube coated with silver to demonstrate that a reduction in endotracheal tube inner lumen bacterial load resulted in a significant reduction in the incidence of VAP. BARD submitted the results of its clinical study and received FDA approval for use of its antimicrobial endotracheal tube to reduce the incidence of VAP from 7.5% in patients intubated with uncoated endotracheal tubes to an incidence of 4.8% in patients intubated with the BARD Silver-Coated endotracheal tubes.16

Endotracheal tube volume loss due to mucus accumulation and/or biofilm formation within the ETT is common among intubated patients.17,18 Partial obstruction of the inner lumen of the ETT poses a problem by increasing the work of breathing and potentially contributing to weaning failure19,20 ETT volume loss has been shown to be associated with prolonged duration of mechanical ventilation and the occurrence of VAP.17 In a study of mechanically ventilated sheep, silver coated ETT cleaned with a mucus shaver was shown to have significantly less accumulation of mucus and bacterial growth.21 There have been no human studies that have examined the effect of ETT intervention in preventing intraluminal volume loss.

Photodynamic treatment (PDT) is a noninvasive technique that uses light to activate light-sensitive agents known as photosensitizers to destroy microbial pathogens. The photosensitizer developed by Advanced Photodynamic Technologies Inc. is in a liquid solution form containing methylene blue as its photoreactive agent. Methylene blue (MB) is a photoactive dye that belongs to the phenothiazine class. MB has a well known human safety profile.22 It has been long known as an antimicrobial drug with its bactericidal effect against a broad spectrum of microorganisms related to photodynamic properties.23 When sprayed on microorganisms, the pathogens absorb the agent and upon being exposed to a specific wavelength of light the pathogens are quickly destroyed. This photosensitizer is a single pure compound and has a strong absorption at wavelengths longer than 620 nanometers (nm). The absorbance peak of MB is at 664 nm; its optical extinction coefficient is 81600 M−1cm−1. The photoactivity of MB results in two types of photooxidation:

The direct reaction between the photoexcited dye and substrate by hydrogen abstraction or electron transfer creating different active radical products.

The energy transfer between the photoexcited dye in triplet state and molecular oxygen producing singlet oxygen. Both kinds of active generated products are strong oxidizers and cause cellular damage, membrane lysis, protein inactivation and DNA modification. Methylene blue has a high quantum yield of the triplet state formation (~T = 0.52–0.58) and a high yield of the singlet oxygen generation (0.2 at pH 5 and 0.94 at pH 9).

The photodynamic mechanism of bacterial cell destruction is by increased permiability of the cell wall and membrane with PDT induced singlet oxygen and oxygen radicals thereby allowing the dye to be further translocated into the cell. Subsequently, the photodynamic photosensitizer in its new sites photodamages inner organelles and structures and induces cell death. Importantly, the PDT mechanism of microbial cell death is completely different from that of oral and systemic antimicrobial agents. Therefore, it would be effective against antimicrobial-agent resistant bacteria, as well as help to prevent the development of resistant microorganisms by providing for another means of microbial eradication. Additionally, this method of topical treatment of microbial biofilms is a simple, inexpensive and repeatable therapy without the risk of development of antimicrobial resistance to this type of treatment. The PDT effect is target specific to only those organisms that have absorbed the photosensitizer and been exposed to a specific wavelength of light (664 nm laser light). Neither the light alone nor the photosensitizer agent alone has any effect on human tissue.22–26

In vitro Study of the Methylene Blue Based Photosensitizer to Photoablate Polymicrobial Antibiotic Resistant Gram-Negative and Gram-Positive Bacterial Biofilms in an Endotracheal Tube/Ventilator Model

In order to effectively treat biofilms in the ETT, we developed a PDT treatment system (PETT) to eradicate microorganisms from the lumen of the endotracheal tube which are a cause of VAP.9–13 The proposed treatment involves spraying a small amount of photosensitizer solution into the lumen of the endotracheal tube and exposing the solution to light via a very small diameter optical fiber placed into the lumen of the endotracheal tube. Both the photosensitizer and optical fiber are placed into the endotracheal tube via an access port in a similar fashion as that routinely performed by respiratory therapists to suction mucus from the inside of endotracheal tubes with a catheter. The placement and use of the PDT devices will not affect normal ventilator performance.

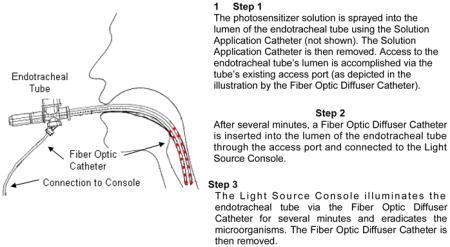

Illustration of the PDT Treatment System

In order to more closely simulate the actual human clinical study environment, a simulated clinical model was developed for testing.

Methods and Materials

Endotracheal Tube Model Setup

To simulate the human clinical study environment we developed a clinical endotracheal tube model to evaluate the effectiveness of the PETT System. The model simulates the complete airway circuitry of an intubated patient including a mechanical ventilator (Inter Med Bear, Bear® 3, Adult Volume Ventilator), humidifier, ventilator airway circuitry tubing and an endotracheal tube. The ventilator and humidifier were running using normal patient output parameters to closely simulate a typical intubated patient. The endotracheal tube was positioned in an angled fixture that simulates typical patient geometry.

Biofilm Generation

Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (clinical isolate) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (clinical isolate) were suspended in 10 mL of tryptic soy broth to achieve a McFarland Standard of 0.5 (1.5×108 cells/mL) as measured by a turbidity nephlometer. This was repeated until there was 65mL of each bacterium, which was combined and vortexed in a 200 mL Erlenmeyer flask. The flask with the bacterium was placed in a 37 °C water bath and appropriate tubing was connected from the outlet connector of the flask through a peristaltic pump to the connector of the proximal end of the endotracheal tube (PCV). The distal end of the endotracheal tube model was then connected through tubing to the inlet connector of the flask. This close loop flow of bacterium broth was circulated through the endotracheal tube for 48 hours.

Photodynamic Therapy Procedure

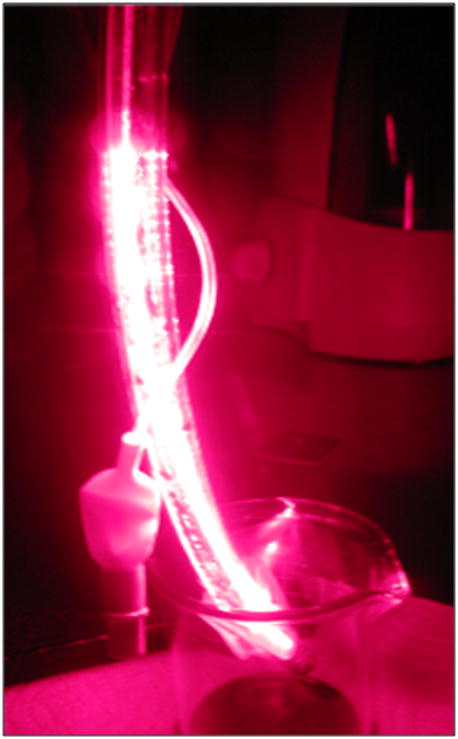

The PETT System Light Source Console was used in all experiments. The Consoles guides the user through each step of the procedure including photosensitizer solution application, Light Delivery Catheter placement and light delivery treatments. After the photosensitizer solution was sprayed into the lumen of the biofilm coated endotracheal tube, the Light Delivery Catheter was inserted through the Y-Adapter until the Light Delivery Catheter stop made contact with the Y-Adapter. This ensured that the Light Delivery Catheter was correctly positioned within the lumen of the endotracheal tube and did not extend beyond. The Light Delivery Catheter was then properly connected to the Y-Adapter. Next, the Light Source Console, which controls the photosensitizer incubation time of 5 minutes followed by the first light treatment of 12 minutes, a dark time of 5 minutes and then a final second light dose of 12 minutes, was started (Figure 1). The Console also automatically delivered a light fluence rate of 150 mW/cm of catheter length. At the end of the second light treatment, the Light Source Console automatically shut down and the Light Delivery Catheter was removed.

Figure 1.

Biofilm coated endotrachal tube undergoing PDT light illumination using the PETT system

Bacterial Culturing and Counting Method

Endotracheal tubes were cultured (both pre and post PDT treatment) using a sterile swab that was placed into 1 mL of phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Samples were serially diluted in PBS and spirally plated using an Autoplate 4000 (Spiral Biotech, Norwood, MA) onto tryptic soy agar with 5% sheeps blood (Remel). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The colonies were counted by a Protos automated counter (Synoptics, Frederick, MD) to determine the number of viable bacteria and expressed as colony forming units (CFU).

Study Design

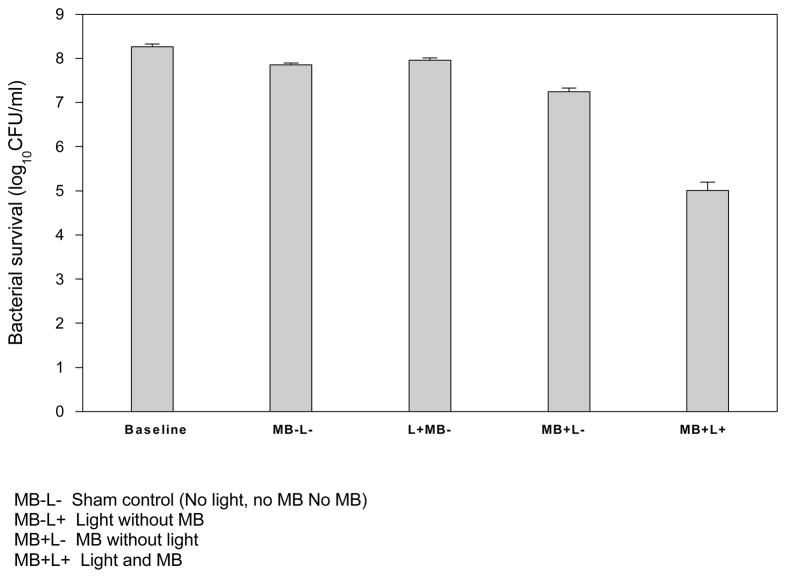

Optimal PDT parameters regarding MB concentration and light intensity were determined in previous in vitro experiments and were repeated using this simulated clinical model. Those parameters included: 500 μg/mL of methylene blue USP trihydrate, a fluence rate of 150 mW/cm of catheter length and a total light dose of 12 minutes on, 5 minutes off and 12 minutes on again. In order to understand the role and affect of each PETT System component, as well as the effect of the model, the following study design was used:

Baseline (the number of microorganisms counted in the endotracheal tube prior to the endotracheal tube being placed in the ventilator model)

Sham control (No light, no MB, but placed in the ventilator model and exposed to the same time, humidity and ventilator flow as all other experiment iterations)

Light without MB

MB without light

Light and MB

A total of 70 endotracheal tubes were tested for each of the study iterations listed above. All experiments used the same test article i.e., an endotracheal tube coated with biofilm as described in the methods above. All iterations of the study design used the same ventilator and humidifier settings and the same time used to deliver the light dose i.e., 12 minutes, plus 5 minutes, plus 12 minutes.

Results

The results found in Table 1 demonstrate that the untreated Control (MB−L−) had a slight reduction (< 0.5 log10) from Baseline. The Baseline value is the number of microorganisms counted in the endotracheal tube prior to the endotracheal tube being placed in the ventilator study model. The Control (sham) experiment exposed the biofilm laden endotracheal tube to the study model using the same parameters for all experiments including the same ventilator and humidifier settings and the same length of time used to deliver the light dose i.e., 12 minutes, 5 minutes and 12 minutes again. However, the Control was not exposed to light or MB. The < 0.5 log10 bacterial reduction in the Control group suggests that the effect of the ventilator and the length of time of the experiment play some minor role in the outcome although the reduction is considered very minor. The experiment group that tested the effect of light alone (MB−L+) resulted in no significant difference compared to the Control (p< 0.05). The experiment group that tested the effect of MB alone (MB+L−) resulted in an approximate 1 log10 decease from Baseline and slightly more than a 0.5 log10 decrease from the Control. This result was expected considering that MB has some bactericidal capabilities on its own, which has been demonstrated by this experiment. In contrast, the PDT experiment of (MB+L+) resulted in a more than 3 log10 reduction (p< 0.005) from baseline. Importantly, the more than 3 log10 reduction from baseline after only one treatment demonstrates the feasibility of MB/PDT to have a significant effect.

Table 1.

Photoablation of Mixed Antibiotic-Resistant Microoganisms in a Simulated Clinical Model

|

Discussion

Pneumonia in ventilated patients is a major clinical problem leading to prolonged length of stay, healthcare costs and in some instances increased mortality. A safe and effective intervention that prevents VAP without increasing the risk of selecting resistant micro-organisms would have a significant impact on patient outcomes and costs. We have demonstrated the ability of MB based PDT using the PETT system to significantly reduce endotracheal tube biofilms, in a single treatment, in a ventilator model simulating the human condition. The PETT system is designed to prevent and control the growth of biofilm within the ETT and is therefore planned for use within 24 hours after intubation and every 8 hours thereafter until the patient is extubated. This treatment schedule would prevent the development of intraluminal ETT biofilm based on previous human studies demonstrating that ETT tube intraluminal biofilms begin to grow after 6 hours of intubation.9,12 Therefore based on the results of our in vitro studies we hypothesize that MB based PDT using the PETT system will decrease the density of bacterial burden in the lumen of ETT as well as tracheal colonization and therefore lower the incidence of ventilator associated tracheobronchitis and VAP compared to a control group of subjects. We also hypothesize that PDT will significantly reduce the biofilm burden and preserve ETT inner diameter loss from mucus accumulation. Preclinical safety studies are underway and a human clinical trial is planned to test the efficacy of the PETT system in intubated intensive care unit patients.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH Grants R43 AI041866, R44 AI041866

LITERATURE REFERENCES

- 1.Koerner RJ. Contribution of endotracheal tubes to the pathogenesis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. J Hosp Infect. 1997;35:83–89. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(97)90096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adair CG, et al. Implications of endotracheal tube biofilm for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:1072–1076. doi: 10.1007/s001340051014. 90251072.134 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Diaz E, Rodriguez AH, Rello J. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: issues related to the artificial airway. Respir Care. 2005;50:900–906. discussion 906–909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leong JR, Huang DT. Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:1409–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safdar N, Crnich CJ, Maki DG. The pathogenesis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: its relevance to developing effective strategies for prevention. Respir Care. 2005;50:725–739. discussion 739–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rello J, et al. Risk factors for ventilator-associated pneumonia by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in presence of recent antibiotic exposure. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:709–714. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pancheco-Fowler V, Gaonkar T, Wyer PC, Modak S. Antiseptic impregnated endotracheal tubes for the prevention of bacterial colonization. J Hosp Infect. 2004;57:170–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adair CG, et al. Eradication of endotracheal tube biofilm by nebulised gentamicin. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:426–431. doi: 10.1007/s00134-002-1223-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman C, et al. The presence and sequence of endotracheal tube colonization in patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:546–551. doi: 10.1183/09031936.99.13354699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sottile FD, et al. Nosocomial pulmonary infection: possible etiologic significance of bacterial adhesion to endotracheal tubes. Crit Care Med. 1986;14:265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz-Blanco J, et al. Electron microscopic evaluation of bacterial adherence to polyvinyl chloride endotracheal tubes used in neonates. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:1335–1340. doi: 10.1097/00003246-198912000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Inglis TJ, Millar MR, Gareth JJ, Robinson DA. Tracheal tube biofilm as a source of bacterial colonization of the lung. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:2014–2018. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.9.2014-2018.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neal F, Adair CG, Gorman SP, Goldsmith C, Webb H. Bacterial biofilm formation on endotracheal tubes: implications for the development of nosocomial pneumonia. Pharmacotherapy. 1991;11:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagon JY, Chastre J, Domart Y, et al. Nosocomial pneumonia in patients receiving continuous mechanical ventilation. Prospective analysis of 52 episodes with use of protected specimen brush and quantitative culture techniques. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1989;139(4):877–84. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/139.4.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craven DE, Steger KA, Barber TW. Preventing nosocomial pneumonia: state of the art and perspectives for the 1990s. Am J Med. 1991;91(3 Part B):44S–53S. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90343-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kollef MH, et al. Silver-coated endotracheal tubes and incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia: the NASCENT randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:805–813. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.7.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah C, Kollef MH. Endotracheal tube intraluminal volume loss among mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:120–125. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000104205.96219.D6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boque MC, Gualis B, Sandiumenge A, Rello J. Endotracheal tube intraluminal diameter narrowing after mechanical ventilation: use of acoustic reflectometry. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:2204–2209. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2465-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Villafane MC, Cinnella G, Lofaso F, Isabey D, Harf A, Lemaire F, Brochard L. Gradual reduction of endotracheal tube diameter during mechanical ventilation via different humidification devices. Anesthesiology. 1996;85:1341–1349. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199612000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Khatib MF, Husari A, Jamaleddine GW, Ayoub CM, Bou-Khalil P. Changes in resistances of endotracheal tubes with reductions in the cross-sectional area. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 25:275–279. doi: 10.1017/S0265021507003134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berra L, et al. Antibacterial-coated tracheal tubes cleaned with the Mucus Shaver: a novel method to retain long-term bactericidal activity of coated tracheal tubes. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32:888–893. doi: 10.1007/s00134-006-0125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Toxicology Program. Executive summary of safety and toxicity information for methylene blue trihydrate 7220-79-3. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jori G, et al. Photodynamic therapy in the treatment of microbial infections: basic principles and perspective applications. Lasers Surg Med. 2006;38:468–481. doi: 10.1002/lsm.20361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Logan ID, McKenna PG, Barnett YA. An investigation of the cytotoxic and mutagenic potential of low intensity laser irradiation in Friend erythroleukaemia cells. Mutat Res. 1995;347:67–71. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(95)90072-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khraishvili GGA. Comparative analysis of cytogenic effects of red (0.63mkm) and infrared (0.85 mkm) low intensity lasers. Tbilisi State Medical University. 2004;4:100–102. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lustig RA, et al. A multicenter Phase I safety study of intratumoral photoactivation of talaporfin sodium in patients with refractory solid tumors. Cancer. 2003;98:1767–1771. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]