Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Over the last decade apprehension has been growing over the effectiveness of existing parenteral vaccines for diphtheria and has created an interest in the development of a mucosally active vaccine. Oral immunization appears to be an effective alternative, but is not without the inherent disadvantages of antigen destruction and tolerance. Therefore, our objective was to investigate the incorporation of diphtheria toxoid (DTx) into bilosomes, which could provide protection as well as aid transmucosal uptake and subsequent immunization. Another objective was to determine the oral dose that will produce serum antibody titres comparable with those produced by i.m. doses of DTx.

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

Bilosomes containing DTx were prepared by thin film hydration and characterized in vitro for their shape, size, percent antigen entrapment and stability. In the in vivo study the anti-DTx IgG and anti-DTx sIgA response was estimated using elisa, in serum and in various body secretions, respectively, following oral immunization with different doses of DTx entrapped in nano-bilosomes.

KEY RESULTS

High dose loaded nano-bilosomes (DTxNB3, 2Lf) produced comparable anti-DTx IgG levels in serum to those induced by i.m. alum-adsorbed DTx (0.5Lf). In addition, all the nano-bilosomal preparations elicited a measurable anti-DTx sIgA response in mucosal secretion, whereas i.m. alum-adsorbed DTx (0.5Lf) was unable to elicit this response.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

The orally administered nano-bilosomal DTx formulation produced comparable serum antibody titres to i.m.alum-adsorbed DTx, at a fourfold higher dose and without the induction of tolerance. This approach will provide an effective and comprehensive immune protection against diphtheria with better patient compliance.

Keywords: mucosal immunization, Peyer's patches, immune tolerance, M-cells, sIgA antibody, vaccination

Introduction

Diphtheria is a serious upper respiratory tract disease caused by the bacterium Corynebacterium diphtheriae. The organism secretes a toxin that can cause inflammation of the pharynx, larynx and trachea. Moreover, when the toxin travels in blood or the lymph system, it can attack just about any organ in the body, and in more than 10% of cases, the disease proves to be fatal (WHO et al., 2009).

According to the latest WHO report, although diphtheria has been well-controlled using the conventional parenteral alum-adsorbed diphtheria toxoid (DTx) vaccine, it is ready to re-emerge (WHO et al., 2009). Furthermore, reports of diphtheria epidemics in some countries have raised serious concerns about its recurrence (George et al., 1995; Galazka, 2000; Kelly and Efstratiou, 2003). There has been a shift in the frequency of occurrence of the disease from childhood to older age groups, as well as the spread of disease to rural areas. This has been accompanied by severe clinical symptoms, raising concerns about the epidemiological and protective efficacy of the conventional parenteral vaccine. Parenteral diphtheria vaccine lacks the ability to induce long-lasting memory, requiring the use of multiple booster doses (Clements and Griffiths, 2002; Galazka 2000; Gandon et al. 2001), thus leading to poor patient compliance. Furthermore, it fails to induce a local secretory antibody response in the respiratory tract (Gandon et al., 2001). Lastly, the use of alum-adsorbed vaccines is associated with IgE-related adverse effects and hypersensitivity reactions, necessitating research for alternative adjuvants (Martin-Munoz et al., 2002). These conditions have created interest in the development of a needle-free, more patient-compliant and mucosally active diphtheria vaccine, which would be suitable for mass vaccination campaigns in poor and developing countries (Fromen-Romano et al., 1999; Schroder and Svenson, 1999; Alpar et al., 2001; van der Lubben et al., 2003). Achieving this objective, however, has been constrained by the fact that purified protein antigens usually induce systemic non-responsiveness rather than active immunity by mucosal administration of vaccine antigens (Shalaby, 1995; Mowat, 2003).

Oral vaccination holds well-documented advantages over parenteral vaccination including ease of administration, increased patient compliance, facility of repeated administration and potential to induce mucosal antibody response. However, the oral delivery of vaccine antigens remains an arduous challenge because of their poor gastrointestinal absorption and susceptibility to enzymatic degradation. Consequently, the antigen needs to be administered more frequently in larger doses, thus leading to systemic non-responsiveness (i.e. oral tolerance) (Shalaby, 1995; Mowat, 2003; Dubois et al., 2005). Several strategies have been devised to provide protection to the orally administered antigens from the hostile environment of the gut, which includes the use of synthetic particulate, polymerized liposomes, live microbial delivery vehicles and bilosomes (Lehr, 1994; Chen et al., 1996; DiBiase and Morrel, 1997; McClean et al., 1998; Conacher et al., 2001; Mann et al., 2004; Shukla et al., 2008; Werle et al., 2009; Amidi et al., 2010; Shukla et al., 2010).

The current study aimed to formulate diphtheria toxoid-loaded nano-bilosomes (DTxNB) and investigate the possibility of DTxNB as an effective vaccine formulation that could induce systemic as well as mucosal antibody responses against diphtheria. Further, we also endeavoured to determine the oral dose of DTx using nano-bilosomes that could produce serum anti-DTx antibody titres, which were comparable with those obtained following i.m. administered doses of alum-adsorbed DTx. Hence, DTx-containing nano-bilosomes with different entrapped doses were prepared and assessed for their potential to induce both mucosal and systemic immune responses.

Methods

Preparation of nano-bilosomes

Sorbitan tristearate (150 µmol), cholesterol and dicetyl phosphate (DCP) in a molar ratio of 7:3:1 were dissolved in 10 mL chloroform in a round-bottomed flask. Solvent was removed under reduced pressure by rotary evaporator to form a thin film on the glass surface of a round-bottomed flask. The film was then hydrated with 3.5 mL PBS (pH 7.4), containing 100 mg of sodium deoxycholate along with 20.0 Lf (low dose, 0.5 Lf per dose, group 1), 40.0 Lf (intermediate dose, 1.0 Lf per dose, group 2) and 80.0 Lf (high dose, 2.0 Lf per /dose, group 3) of DTx, to produce DTx-loaded bilosomes. The total preparation volume was than made up to 4 mL with PBS. The bilosomes were then formed by extrusion through a 200 nm pore membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). The unentrapped antigen and sodium deoxycholate were removed by mini-column centrifugation technique using a Sephadex G-100 column (Fry et al., 1978). The eluted fractions were collected and challenged with Triton X-100 (0.2% v v-1). Samples were diluted in order to fall within the standard curve concentration range. DTx was measured using a micro BCA protein estimation kit (Genei, Bangalore, India). The experiment was repeated three times using a fresh column each time.

Characterization of bilosomes

Morphological examination of the bilosomes was performed using a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (Philips CM-10, Eindhoven, the Netherlands) after negative staining of the samples with phosphotungustic acid solution (2% w v-1). The mean particle size was determined using a laser diffraction-based particle size analyzer (Zetasizer Nano ZS 90, Malvern Instruments Co., Worcestershire, UK).

In-process stability

SDS-PAGE was performed so as to confirm the integrity (in-process stability) of the entrapped antigen in the final formulation, in comparison with the native antigen and reference markers. The samples were loaded onto SDS electrophoresis assembly (Bio-Rad, Gurgaon, Haryana, India) using 5% stacking gel and 12% separation gel, run at 60–110 V until the dye band reached the gel bottom. Subsequent to migration the gel was removed and stained with Coomassie blue to locate the individual position of proteins and was then finally destained.

Stability in simulated gastric fluid, simulated intestinal fluid and bile salt solutions

The stability of the DTx-loaded bilosomes was determined in simulated gastric fluid (SGF, pH 1.2), simulated intestinal fluid (SIF, pH 7.5) and at different concentrations of bile salt solutions (5 and 20 mM), by addition of 1.8 mL of different solutions to 0.2 mL of bilosomal formulation. After 2 h, samples were withdrawn, and unentrapped DTx was removed by minicolumn centrifugation using Sephadex G-100 column (Fry et al., 1978). Unentrapped DTx free bilosomes were challenged with Triton X-100 (0.2%v/v), and DTx was estimated using the micro BCA protein estimation kit (Genei).

In vivo uptake study

For confirmation of efficient uptake of nano-bilosomes in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), a fluorescent uptake study was performed. Fluorescent marker (i.e. R 123) was loaded into the nano-bilosomes and administered orally. The animals were killed, the small intestine was removed and cut, and microtomy was conducted after 5 h (Shalaby, 1995) of oral administration of rhodamine-loaded nano-bilosomal formulation. Sections of around 3 µm thickness were then examined under confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) (Bio-Rad, MRC 1024, UK) (n = 3). Control animals were administered the equivalent amount of unentrapped rhodamine orally and microtomy was carried out.

Storage stability

The stability of the formulations over time was checked in screw-capped glass bottles in a stability chamber (humidity and temperature controlled cabinet, Lab Hosp Corporation, Mumbai, India) at 5 ± 3°C and 25 ± 2°C, at 70% relative humidity, for 30 days. The formulations were evaluated at weekly intervals for changes in size and % residual antigen. The initial antigen content was taken as 100%.

Immunization and sample collection

Female BALB/c mice of 6–8 weeks age, weighing between 15 and 20 g, were used for the in vivo studies. Animals were housed in groups of five with free access to food and water. They were deprived of any food intake for 3 h prior to immunization. The study protocols followed were approved by the Institutional Animals Ethical Committee of Panjab University, Chandigarh. The studies were carried out according to the guidelines of the Council for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. The mice were immunized by intragastric lavage, following the protocol of three primary inoculations for three consecutive days and boosting after 3 weeks. The mice were immunized by intragastric administration of formulations with 0.5 mL of low dose DTx nano-bilosomes (DTxNB1, 0.5 Lf per dose, group 1); 0.5 mL of intermediate dose DTx nano-bilosomes (DTxNB2, 1 Lf per dose, group 2); 0.5 mL of high dose DTx nano-bilosomes (DTxNB3, 2 Lf per dose, group 3) and 0.5 mL of unentrapped 2 Lf per dose of DTx for three consecutive days. Booster immunization was carried out after 3 weeks. The control group (group 5) received a 0.5 Lf per dose of alum-adsorbed DTx i.m. on day 0 and a booster 3 weeks after primary immunization.

Samples of serum and secretions (saliva, nasal secretions, vaginal fluid and intestinal lavage) were collected from the immunized animals on day 0 before immunization. Blood was collected by retro-orbital plexus under light ether anaesthesia after 14, 28, 42 and 56 days of booster dosing. Sera were stored at −40°C until analysed by elisa for antibody titres. The intestinal lavage, vaginal, nasal and salivary secretions were collected after 5 weeks of booster immunization. For collection of saliva, mice were administered 0.2 mL of sterile solution of pilocarpine (10 mg·mL−1) i.p., and the saliva was collected 20 min later using a capillary tube. Intestinal lavage was collected using the technique reported earlier (Elson et al., 1984). Briefly, four doses of 0.5 mL lavage solution (NaCl 25 mM, Na2SO4 40 mM, KCl 10 mM, NaHCO3 20 mM and polyethylene glycol MW 3350; 48.5 mM) were administered intragastrically at 15 min intervals using a blunt-tipped feeding needle. Thirty minutes after the last dose, the mice were given 0.2 mL of pilocarpine (10 mg·mL−1) i.p. A discharge of intestinal contents was carefully collected for the next 20 min. Vaginal secretions were collected using a pipettor to douche the mice with 0.1 mL of PBS (pH 7.4), which was then aspirated back into the pipette tip and used for the determination of antibody levels. The nasal wash was similarly collected by cannulating the trachea of the mice after they had been killed. The nasal cavity of the dead mice was flushed three times with 0.5 mL of 1% BSA containing PBS (BSA-PBS, pH 7.4). These fluids were stored with 100 mM PMSF as a protease inhibitor at −40°C until analysed by elisa for secretory antibody (sIgA) levels.

Measurement of specific IgG and IgA responses

Antibody responses in immunized animals were monitored using a microplate elisa. Microtitre plates (Nunc-Immuno Plate® Fb 96 Mexisorp, NUNC, Rochester, NY, USA) were coated with 0.5 Lf·mL−1 DTx in PBS (pH 7.4), 100 µL per well, and incubated overnight at 4°C. The plates were washed three times with PBS-Tween 20 (0.05%, v/v) (PBST) and blocked with PBS-BSA (3% w/v) for 2 h at 37°C, followed by washing with PBS-T. The serum/ body fluids were serially diluted with PBS, and 100 µL of each sample was added to each well of coated elisa plates. The plates were incubated for 1 h at room temperature and washed three times with PBST. One hundred microlitres of peroxidase-labelled goat anti-mouse IgG/ IgA (1:1000 dilution, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well. The plates were covered, and after incubation for 1 h at room temperature, washing was repeated. One hundred microlitres of tetramethyl benzidine (TMB-H2O2) solution was added to each well, followed by addition of 50 µL of H2SO4 after 90 min. After 15 min of incubation, the plate was read at 450 nm using a plate reader (Bio-Rad, USA). End-point titres were expressed as the log of the reciprocal of the last dilution, which gave an optical density (OD) at 450 nm above the OD of negative controls.

Data analysis and statistical procedures

Analysis of antibody titres was performed on logarithmically transformed data, and the data are presented along with SD. Student's t-test was used to compare mean values of different groups. Multiple comparisons were made using a one-way anova, followed by Dunnett's post anova test using InStat™ software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

Materials

Diphtheria toxoid was received as gift sample from M/s Panacea Biotech Ltd, Panjab, India. Sorbitan tristearate and cholesterol were procured from M/s Central Drug House (P) Ltd, New Delhi, India and M/s Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd, Mumbai, India respectively. Sodium deoxycholate, rhodamine 123 (R123), DCP and Sephadex G-100 were purchased from M/s Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO. BCA protein estimation kit was procured from M/s Genei, Bangalore, India. All the reagents used in SDS-PAGE were obtained from M/s Bio-Rad, India. All other chemicals and reagents were of analytical grade and purchased from the local suppliers unless otherwise mentioned.

Results

Characterization of bilosomes

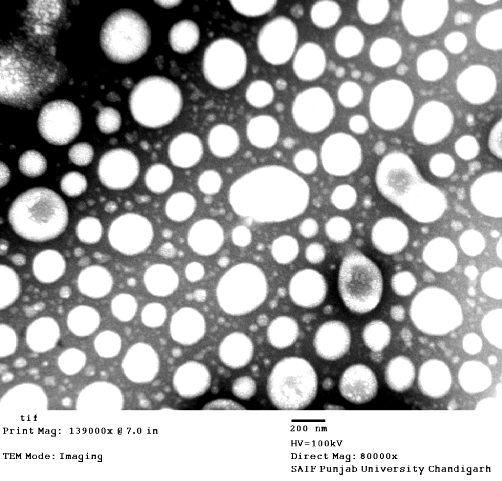

The TEM photomicrographs (Figure 1) show that the vesicles were unilamellar and spherical in shape. The mean particle size as determined by photon correlation spectroscopy using a Zetasizer Nano ZS 90 (Malvern Instruments Co.) was found to be 206 ± 20 nm. The amount of DTx entrapped in the bilosomes was found to be around 20–24% of the amount added.

Figure 1.

TEM photomicrograph of DTx-loaded nano-bilosomes.

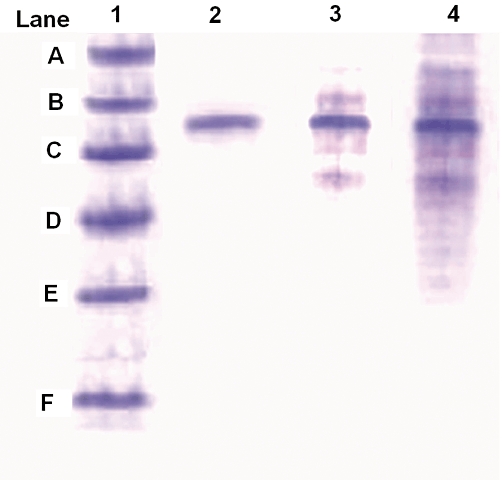

In-process stability

In-process stability and integrity of the entrapped antigen was assessed by SDS-PAGE. The gel was run with the wells containing standard markers, native DTx and DTx loaded in nano-bilosomes. Clearly visible bands for pure as well as extracted antigen from the nano-bilosomes were observed for DTx in between 45 and 66 kDa (Figure 2). For the comparison, the native DTx and protein molecular weight markers were also run in separate wells of the same gel.

Figure 2.

SDS-PAGE of antigen from formulations. (Lane 1) Mol. wt. markers: (A) phosphorylase b, 97.4 kDa; (B) BSA, 66.2 kDa; (C) ovalbumin, 45.0 kDa; (D) bovine carbonic anhydrase, 31.0 kDa; (E) trypsin inhibitor, 21.5 kDa; (F) lysozyme, 14.2 kDa. (Lane 2) native DTx solution. (Lane3) Alum-adsorbed DTx. (Lane 4) DTx nano-bilosomal formulation.

Stability in simulated gastric fluid, simulated intestinal fluid and bile salt solutions

The stability of the formulation was assessed in SGF, pH 1.2 and SIF, pH 7.5. It was found that around 88% and 92% of DTx was retained in the vesicles in SGF and SIF, respectively.

The formulations were also tested in 5 and 20 mM bile salt solutions. It was found that around 93% of DTx was retained in the vesicles in the 5 mM solution, and 83% in the 20 mM solution.

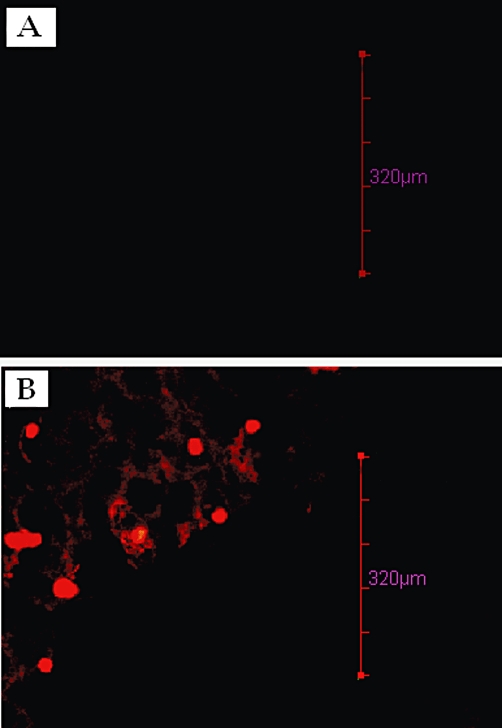

CLSM

The CLSM studies revealed that after administration of R 123 loaded bilosomes the fluorescence localized in the GALT region was much higher (Figure 3B) than in the sections in which unentrapped R 123 was administered orally (Figure 3A). This indicated the effective uptake of the bilosomes by the GALT (M Cells) especially by Peyer's patches.

Figure 3.

CLSM image of Peyer's patches (M cells) after oral uptake of (A) unentrapped R 123, administered orally, and (B) R 123-entrapped nano-bilosomes, administered orally.

Storage stability

On storage at 25 ± 2°C, around 94% antigen remained intact in the nano-bilosomes after 30 days, while >98% antigen was measured when the DTx-loaded nano-bilosomes were stored at 5 ± 3°C. Negligible changes in particle diameter were observed at 5 ± 3°C but a slight increase (around 10 nm) occurred after storage at 28 ± 1°C.

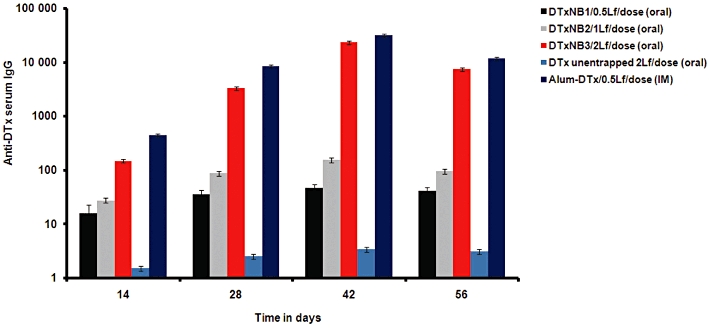

Immunological studies

The serum anti-DTx IgG titres obtained subsequent to oral administration of DTxNB3 (i.e. high dose, 2 Lf per dose) were comparable with that obtained after i.m. administration of alum-adsorbed DTx (0.5 Lf, control group) (P > 0.05). However, the responses obtained following oral administration of DTxNB3 (i.e. high dose, 2 Lf per dose) were significantly different (P < 0.01) from those to DTxNB1 (i.e. low dose, 0.5 Lf per dose). The systemic IgG immune responses are graphically presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Serum anti-DTx IgG profile of mice immunized orally with different formulations. The serum was collected after 14, 28, 42 and 56 days of boosting. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). Multiple comparisons were made using one-way anova followed by post hoc analysis using Dunnett's test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

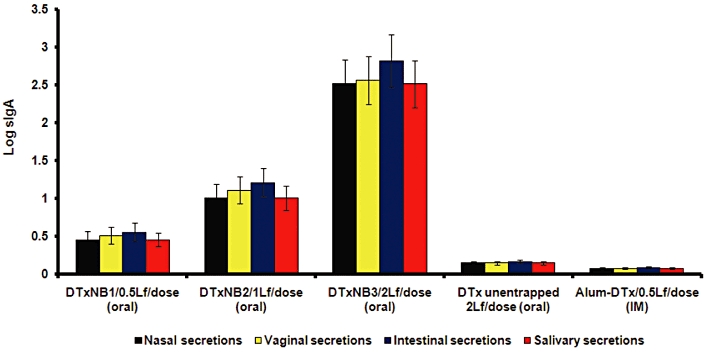

All the nano-bilosomal formulations, administered orally, produced significant sIgA responses (P < 0.01) in mucosal secretions vis-à-vis the alum-adsorbed DTx (control group), administered i.m. Alum-adsorbed formulations and unentrapped DTx, 2 Lf did not elicit detectable sIgA in the mucosal secretions. The mucosal immune response measured as IgA titres is shown in Figure 5. However, the four times higher unentrapped DTx was unable to produce any significant immune response, both at systemic as well as mucosal levels. This can ostensibly be attributed due to the lack of protection of the antigen, leading eventually to its denaturation and destruction by the acidic gastric environment as well as by other intestinal enzymes.

Figure 5.

Secretory IgA level in nasal, vaginal, intestinal and salivary secretions of mice immunized orally with different formulations after 5 weeks of boosting. Values are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5). Multiple comparisons were made using one-way anova followed by post hoc analysis using Dunnett's test. Alum-DTx versus DTxNB1 (*P < 0.05), Alum-DTx versus DTxNB2 (**P < 0.01), Alum-DTx versus DTxNB3 (**P < 0.01).

Discussion

The objective of this study was to investigate DTxNB as an effective oral vaccine formulation, which could induce both systemic and mucosal antibody response against diphtheria. The studies embarked upon the determination of the oral dose of DTx using nano-bilosomes that could produce systemic anti-DTx antibody titres via oral route, comparable with those following alum-adsorbed DTx i.m. immunization. In this context, we were able to demonstrate that orally administered DTx-loaded nano-bilosomes stimulated immune responses both at the systemic as well as at the mucosal level.

The prepared DTx-loaded nano-bilosomes were unilamellar and spherical in shape. The amount of DTx entrapped in the nano-bilosomes was analogous to that observed in other antigen-loaded bilosomes (Shukla et al., 2008). The in-process stability study revealed that the preparation conditions and the amount of bile salt used for the formulation did not cause any irreversible aggregation or cleavage of the antigen. Furthermore, in order to evaluate the ability of the nano-bilosomes to resist a range of bioenvironmental stresses as well as to retain the stability of antigen, the stability of the vaccine formulations in simulated fluids as well as in different bile salt solutions was determined. The studies confirmed significant stability of the nano-bilosomes. Stability studies (in-process, in simulated fluids and at storage) are of vital importance, especially in the case of immunological preparations, as denatured or deactivated antigen will lead to the generation of an inadequate immune response. This in turn will make the subject prone to the disease against which the vaccination is being carried out. Immunological products are recommended to be stored in refrigerated conditions; the storage stability at room temperature was also performed to study the protective effect of the nano-bilosomes towards the entrapped antigen. The stability of the formulation may be attributed to the negative charge on the surface of the nano-bilosomes (because of the negative charge inducer; DCP), preventing fusion and aggregation on storage. The presence of a negative charge causes retardation of fusion and aggregation due to electrostatic repulsion.

The mucosal surfaces are known to have abundant B cells, T cells and plasma cells. Uptake of antigen by mucosal tissues (i.e. GALT) is essential for the induction of immune responses (Neutra and Kraehenbuhl, 1996; Clark et al., 2001; Jepson et al., 2004). The CLSM studies demonstrated efficient uptake of bilosomes by the GALT; thus, confirming that the nano-bilosomes are capable of transporting vaccine antigens to the Peyer's patches, resulting in both mucosal and systemic immune responses.

Oral immunization with antigens often leads to feeble immune responses probably due to incomplete absorption of antigens by the Peyer's patches (Dertzbaugh and Elson, 1993). Thus, in case of oral delivery of vaccines, the protection of vaccine antigens from the hostile gastrointestinal environment containing acid and enzymes is essential. Furthermore, oral tolerance, a key feature of intestinal immunity generates systemic non-responsiveness to the ingested antigens (Worbs et al., 2006). Therefore, in order to induce significant immune protection, a fine equilibrium between the mucosal delivery of antigens and induction of tolerance (Holmgren and Czerkinsky, 2005) is required. Hence, the nano-bilosomal vaccine delivery system was utilized to overcome the above mentioned problems. An important feature of the nano-bilosome-based DTx vaccine was that it was immunogenic when administered by the oral mucosal route. Systemic immune responses were also seen after oral immunization of mice with DTx-loaded nano-bilosomes, although more frequently administered, higher doses were required for this route. This probably reflects the requirement of higher amounts of antigen on oral administration as compared with other routes of administration.

M cells overlying Peyer's patches take up the gut luminal antigens by endocytosis and transport them to underlying lymphoid cells in the dome region containing functional T, B and antigen-presenting cells (McGhee et al., 1992). The T cells act as helpers for the production of antibodies by the B cells. Various cytokines, from the activated TH cells, are instrumental in activating B cells, TC cells, macrophages and various other cells that participate in the immune responses. Furthermore, the cytokines play a key role in B-cell activation, proliferation, differentiation and class switching (Kuby, 2007; McGhee et al. 1992). Hence, production of specific anti-DTx sIgA and IgG antibodies, confirms the activation of T cells upon oral immunization. Our results on the IgG antibody response showed that a fourfold higher nano-bilosomal dose is needed to elicit a comparable response with that of the alum-adsorbed DTx administered i.m. However, our results are vital and interesting, with respect to the earlier findings with positively charged mucoadhesive microparticles (van der Lubben et al., 2003), in that our negatively charged non-mucoadhesive nano-bilosomes produced an sIgG response and sIgA response at a dose 20 times less and at a lower dosing frequency. In contrast to the 40 Lf with total of six doses utilized in an earlier study, in the present immunization protocol, the highest dose used was 2 Lf and a total of three doses was given before boosting. This was done in order to avoid the possibility of oral tolerance occurring due to the high dose of antigen and higher dosing frequency. Furthermore, van der Lubben et al. (2003) only reported the induction of sIgA in the intestinal secretions. In this context, our nano-bilosomal formulations induced significant sIgA response not only at the site of application (i.e. in the intestinal secretions) but also at the distant mucosal sites. The significant nasal, vaginal and salivary IgA antibody responses are of vital importance as the natural route of infection for diphtheria is by the respiratory mucosa. Hence, local mucosal protection against pharyngeal carriage is likely to be decisive for preventing dissemination of disease in populations. Conventional parenteral alum-adsorbed DTx vaccines are not able to stimulate mucosal immune responses (Eriksson and Holmgren, 2002; Shalaby, 1995), thus restricting their efficacy in infections of mucosal surfaces such as the respiratory tract. This also tends to explain the emerging limitations of the current vaccination schedule against diphtheria (Martin-Munoz et al., 2002). The applicability of nano-bilosome-based oral mucosal diphtheria vaccine is emphasized more, due to the fact that DTx-loaded nano-bilosomes also primed excellent anti-toxin neutralizing antibody responses in the circulation after oral immunization following transmucosal uptake.

Conclusions

To conclude, the results of this study demonstrated that the DTx-loaded nano-bilosomal vaccine formulation was significantly immunogenic when administered by the oral mucosal route. The four times higher bilosomal entrapped dose required to produce a comparable systemic antibody response has an added advantage of secretory mucosal protection. Moreover, the ability of DTx-loaded nano-bilosomes to stimulate comparatively balanced systemic as well as local mucosal immune responses makes them a potentially promising formulation for inducing as well as boosting protective immunity against diphtheria. The nano-bilosomes-based DTx vaccine formulation may also provide a useful way of developing mucosally active oral diphtheria vaccines.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to M/s Panacea Biotec Ltd, Panjab, India for providing the gift sample of diphtheria toxoid (DTx). The authors are also thankful to National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research (NIPER), Punjab, and Sophisticated Analytical Instrumentation Facility (SAIF), Panjab University, Chandigarh, for providing the facilities of confocal laser scanning microscopy and Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS 90, and TEM studies, respectively. Authors also express gratitude for the University Grants Commission (UGC), New Delhi, India, for providing Research Fellowship in Sciences for Meritorious Students to one of us (AS).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CLSM

confocal laser scanning microscope

- DCP

dicetyl phosphate

- DTx

diphtheria toxoid

- DTxNB

diphtheria toxoid-loaded nano-bilosomes

- GALT

gut-associated lymphoid tissue

- PBST

PBS Tween

- R123

rhodamine 123

- SGF

simulated gastric fluid

- SIF

simulated intestinal fluid

- sIgA

secretory immunoglobulin A

- TEM

transmission electron microscope

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Alpar HO, Eyles JE, Williamson ED, Somavarapu S. Intranasal vaccination against plague, tetanus and diphtheria. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2001;51:173–201. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amidi M, Mastrobattista E, Jiskoot W, Hennink WE. Chitosan-based delivery systems for protein therapeutics and antigens. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2010;62:59–82. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Torchilin V, Langer R. Lectin-bearing polymerized liposomes as potential oral vaccine carriers. Pharm Res. 1996;13:1378–1383. doi: 10.1023/a:1016030202104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Jepson MA, Hirst BH. Exploiting M cells for drug and vaccine delivery. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2001;50:81–106. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00149-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements CJ, Griffiths E. The global impact of vaccines containing aluminium adjuvants. Vaccine. 2002;20(Suppl 3):S24–S33. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00168-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conacher M, Alexander J, Brewer JM. Oral immunisation with peptide and protein antigens by formulation in lipid vesicles incorporating bile salts (bilosomes) Vaccine. 2001;19:2965–2974. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dertzbaugh MT, Elson CO. Comparative effectiveness of the cholera toxin B subunit and alkaline phosphatase as carriers for oral vaccines. Infect Immun. 1993;61:48–55. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.1.48-55.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiBiase MD, Morrel EM. Oral delivery of microencapsulated proteins. Pharm Biotechnol. 1997;10:255–288. doi: 10.1007/0-306-46803-4_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B, Goubier A, Joubert G, Kaiserlian D. Oral tolerance and regulation of mucosal immunity. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:1322–1332. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elson CO, Ealding W, Lefkowitz J. A lavage technique allowing repeated measurement of IgA antibody in mouse intestinal secretions. J Immunol Methods. 1984;67:101–108. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(84)90089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson K, Holmgren J. Recent advances in mucosal vaccines and adjuvants. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14:666–672. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromen-Romano C, Drevet P, Robert A, Menez A, Leonetti M. Recombinant Staphylococcus strains as live vectors for the induction of neutralizing anti-diphtheria t oxin antisera. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5007–5011. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5007-5011.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fry DW, White JC, Goldman ID. Rapid separation of low molecular weight solutes from liposomes without dilution. Anal Biochem. 1978;90:809–815. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(78)90172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galazka A. The changing epidemiology of diphtheria in the vaccine era. J Infect Dis. 2000;181(Suppl 1):S2–S9. doi: 10.1086/315533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandon S, Mackinnon MJ, Nee S, Read AF. Imperfect vaccines and the evolution of pathogen virulence. Nature. 2001;414:751–756. doi: 10.1038/414751a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George RC, Beloborodov VB, Efstratiou A. Diphtheria in the 1990s: return of an old adversary. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1995;1:139–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1995.tb00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmgren J, Czerkinsky C. Mucosal immunity and vaccines. Nat Med. 2005;11(4) Suppl:S45–S53. doi: 10.1038/nm1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jepson MA, Clark MA, Hirst BH. M cell targeting by lectins: a strategy for mucosal vaccination and drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 2004;56:511–525. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly C, Efstratiou A. Seventh International Meeting of the European Laboratory Working Group on Diphtheria. Vienna: Euro Surveill; 2003. pp. 189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuby J. Immunology. 5th edn. New York: W. H. Freeman and Co.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lehr CM. Bioadhesion technologies for the delivery of peptide and protein drugs to the gastrointestinal tract. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1994;11:119–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Lubben IM, Kersten G, Fretz MM, Beuvery C, Coos Verhoef J, Junginger HE. Chitosan microparticles for mucosal vaccination against diphtheria: oral and nasal efficacy studies in mice. Vaccine. 2003;21:1400–1408. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00686-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann JFS, Ferro VA, Mullen AB, Tetley L, Mullen M, Carter KC, et al. Optimisation of a lipid based oral delivery system containing A/Panama influenza haemagglutinin. Vaccine. 2004;22:2425–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Munoz MF, Pereira MJ, Posadas S, Sanchez-Sabate E, Blanca M, Alvarez J. Anaphylactic reaction to diphtheria-tetanus vaccine in a child: specific IgE/IgG determinations and cross-reactivity studies. Vaccine. 2002;20:3409–3412. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00228-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClean S, Prosser E, Meehan E, O'Malley D, Clarke N, Ramtoola Z, et al. Binding and uptake of biodegradable poly-DL-lactide micro- and nanoparticles in intestinal epithelia. Eur J Pharm Sci. 1998;6:153–163. doi: 10.1016/s0928-0987(97)10007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGhee JR, Mestecky J, Dertzbaugh MT, Eldridge JH, Hirasawa M, Kiyono H. The mucosal immune system: from fundamental concepts to vaccine development. Vaccine. 1992;10:75–88. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(92)90021-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mowat AM. Anatomical basis of tolerance and immunity to intestinal antigens. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:331–341. doi: 10.1038/nri1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neutra MR, Kraehenbuhl J. Antigen uptake by M cells for effective mucosal vaccines. In: Kiyono H, Ogra PL, McGhee JR, editors. Mucosal Vaccines. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1996. pp. 41–55. [Google Scholar]

- Schroder U, Svenson SB. Nasal and parenteral immunizations with diphtheria toxoid using monoglyceride/fatty acid lipid suspensions as adjuvants. Vaccine. 1999;17:2096–2103. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalaby WSW. Development of oral vaccines to stimulate mucosal and systemic immunity: barriers and novel strategies. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1995;74:127–134. doi: 10.1006/clin.1995.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Khatri K, Gupta PN, Goyal AK, Mehta A, Vyas SP. Oral immunization against hepatitis B using bile salt stabilized vesicles (bilosomes) J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2008;11:59–66. doi: 10.18433/j3k01m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla A, Katare OP, Singh B, Vyas SP. M-cell targeted delivery of recombinant hepatitis B surface antigen using cholera toxin B subunit conjugated bilosomes. Int J Pharm. 2010;385:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werle M, Takeuchi H, Bernkop-Schnurch A. Modified chitosans for oral drug delivery. J Pharm Sci. 2009;98:1643–1656. doi: 10.1002/jps.21550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO, UNICEF, World Bank. State of the World's Vaccines and Immunization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Worbs T, Bode U, Yan S, Hoffmann MW, Hintzen G, Bernhardt G, et al. Oral tolerance originates in the intestinal immune system and relies on antigen carriage by dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]