Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE

Adenosine is believed to participate in the pathological development of asthma through a mast cell-dependent mechanism. Our study aimed to pharmacologically characterize the functions of adenosine receptor (AR) subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B and A3) in primary human cultured mast cells (HCMC).

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACH

HCMC were derived from progenitor stem cells in buffy coat and the effects of adenosine receptor ligands on basal and IgE-dependent histamine release were evaluated.

KEY RESULTS

Adenosine and analogues alone did not induce HCMC degranulation. When HCMC were activated by anti-IgE after 10 min pre-incubation with adenosine, a biphasic effect on histamine release was observed with enhancement of HCMC activation at low concentrations of adenosine (10−9–10−7 mol·L−1) and inhibition at higher concentrations (10−6–10−4 mol·L−1). The potentiating action was mimicked by A1 AR agonists CCPA and 2'MeCCPA, and inhibited by the A1 AR antagonist PSB36. In contrast, the inhibitory action of adenosine was mimicked by the non-specific A2 AR agonist CV1808 and attenuated by A2B AR antagonists PSB1115 and MRS1760. The non-selective AR antagonist CGS15943 attenuated both the potentiating and inhibitory actions.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

We have defined for the first time the contribution of A1 and A2B ARs, respectively, to the potentiating and inhibitory action of adenosine on human mast cell activation. With reference to the current trend of developing novel anti-asthmatic agents from AR ligands, our results suggest that inhibition of human mast cell activation would be a mechanism for A1 AR antagonists, but not A2B AR antagonists.

Keywords: Adenosine, anti-IgE, asthma, histamine, human mast cells

Introduction

Activation of mast cells through cell surface IgE receptors (FcεRI) initiates the release of chemical mediators, which are pivotal in the pathogenesis of inflammatory disorders such as asthma. The mast cells store some of these mediators preformed in their secretory granules (e.g. histamine, neutral proteases and TNF-α) and synthesize others during activation (e.g. PGD2, leukotrienes and various cytokines). The level of adenosine is increased in both bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluids and exhaled breath condensate of patients with asthma (Livingston et al., 2004), suggesting that this endogenous purine nucleotide is associated with the development of the disease. Moreover, adenosine and its precursor AMP can provoke bronchoconstriction when inhaled by asthmatic individuals, but not in non-asthmatic subjects (Phillips et al., 1990; Forsythe and Ennis, 1999). Mast cells in the airways have been suggested to play a role in the bronchoconstricting effect of exogenous adenosine through the release of strong bronchospastic agents (van den Berge et al., 2007).

Adenosine exerts its cellular effects through four distinct subtypes of adenosine receptor (AR), namely A1, A2A, A2B and A3, which belong to the GPCR family (Jacobson and Gao, 2006; Spicuzza et al., 2006). A1 and A3 ARs are Gαi-protein-coupled receptors, and their activation decreases adenylyl cyclase activity and cAMP levels, while PLC activity is increased by the βγ subunit of the activated Gi protein. In contrast, A2A and A2B ARs are Gαs-protein-coupled receptors and their activation conversely increases cAMP levels. Additionally, A1 ARs have also been reported to couple with Gαo-proteins to activate K+ or inhibit Ca2+ conductance, whereas A2B ARs and A3 ARs can also couple to Gαq-proteins and stimulate PLC activity (Jacobson and Gao, 2006; Alexander et al., 2009). Adenosine at nanomolar concentrations can activate A1 and A2A ARs, while sub-micromolar and micromolar concentrations are required for activating A3 and A2B ARs, respectively (Klinger et al., 2002).

Extensive pharmacological studies in rodents revealed that adenosine does not directly activate mast cells but can significantly potentiate mast cell activation induced by a variety of stimuli in an A3 AR-dependent manner (Ramkumar et al., 1993). However, investigations into the interaction between adenosine and human mast cells are less extensive and have produced controversial results. Early studies with dispersed human lung mast cells (HLMC) in general reported that adenosine did not induce histamine release alone but produced opposing effects on histamine release mediated by various secretagogues. Peters et al. (1982) and Peachell et al. (1991) reported that adenosine enhanced mediator release at low concentrations but exhibited inhibitory actions at high concentrations. However, Hughes et al. (1984) reported that adenosine and analogues in general inhibited antigen-induced histamine release dose-dependently when added to HLMC at times up to 5 min before activation. A small potentiation was only observed if adenosine was added 5 min after challenge. The discrepancies between these observations have been suggested to be due to different mast cell dispersion techniques, which modified membrane properties, or the use of impure mast cell preparations containing different degrees of purity in mast cells (Peachell et al., 1991). Pharmacological studies suggested that the responses of HLMC to adenosine displayed characteristics most closely resembling an A2 AR-linked process (Hughes et al., 1984; Peachell et al., 1991).

In order to overcome the lack of a homogeneous population of human mast cells, studies were carried out in the human mast cell like (HMC-1) cell line, and it was demonstrated that the adenosine analogue NECA alone was able to evoke IL-8 release through A2B AR-mediated Gαq-coupled PLC activation (Feoktistov et al., 1995). Because HMC-1 is an immature atypical mast cell-line that lacks FcεRI, the effect of adenosine on immunological stimulation cannot be truly reflected (Wilson et al., 2009). With the development of culturing techniques, primary human mast cells were developed from progenitors isolated from human umbilical cord-blood, and an early study using these cells observed only an inhibitory action of adenosine (Suzuki et al., 1998). Although the cord-blood derived human mast cells are a better working model for human tissue mast cells than HMC-1 cells, they have different characteristics from adult human mast cells (Inomata et al., 2005; Holm et al., 2008). In contrast, mast cells cultured from progenitors isolated from adult peripheral blood demonstrated a higher degree of resemblance to human tissue mast cells and are more preferred for functional studies (Wang et al., 2006a; Holm et al., 2008). In fact, our preliminary study demonstrated that adenosine produced a biphasic modulatory effect on anti-IgE-induced histamine release from primary mast cells cultured from human peripheral blood progenitors (Yip et al., 2009). This further supports our postulation that these primary human cultured mast cells (HCMC) are suitable for the further characterization of the mast cell modulatory actions of adenosine in humans. The aim of the current study was to provide a more comprehensive pharmacological investigation into the roles of AR subtypes in the activation of primary human mast cells by using peripheral blood derived HCMC.

Methods

Reagents

Adenosine and anti-human IgE antibody (ε-chain specific) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Human myeloma IgE and 6-S-[(4-nitrophenyl)methyl]-6-thioinosine (NBMPR) were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). AR agonists and antagonists were purchased from Tocris (Bristol, UK). The agonists were 2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine (CCPA), 2-chloro-N-cyclopentyl-2′-methyladenosine (2′-MeCCPA), 2-phenylaminoadenosine (CV1808), 4-[2-[[6-amino-9-(N-ethyl-b-D-ribofuranuronam-idosyl)-9H-purin-2-yl]amino]ethyl]-benzenepropanoic acid hydrochloride (CGS21680), 2-(1-hexynyl)-N-methyladenosine (HEMADO), 1-[2-chloro-6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]-1-deoxy-N-methyl-b-D-ribofuranuronamide (2-Cl-IB-MECA) and 5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine (NECA). The antagonists were 1-butyl-8-(hexahydro-2,5-methanopentalen-3a(1H)-yl)-3,7-dihydro-3-(3-hydroxypropyl)-1H-purine-2,6-dione (PSB36), 2-(2-furanyl)-7-[3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propyl]-7H-pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]pyrimidin-5-amine (SCH442416), 4-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1-propyl-1H-purin-8-yl)-benzene-sulphonic acid potassium salt (PSB1115), N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-[4-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-1H-purin-8-yl)phenoxy]acetamide (MRS1706), 2-phenoxy-6-(cyclo-hexylamino)purine hemioxalate (MRS 3777) and 9-chloro-2-(2-furanyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo[1,5-c]quinazolin-5-amine (CGS 15943).

HCMC

Mature primary HCMC were derived from progenitors isolated from fresh buffy coat, as previously described (Wang et al., 2006b). Briefly, isolated progenitors were first cultured with IL-6 and stem cell factor (SCF) (PeproTech Asia, Rehovot, Israel) in serum free methylcellulose (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) for 6 weeks with IL-3 added in the first two weeks only. This was followed by 6 weeks of culture in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with SCF and IL-6. HCMC were identified by May Grunwald–Giemsa (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) staining of cytoplasmic granules, as well as immunocytochemical staining of human mast cell tryptase using a monoclonal anti-human tryptase antibody (Chemicon, Billerica, MA, USA) and the alkaline APAAP kit from Dako (Carpinteria, CA, USA).

Histamine release assay

At 12–14th week of culture, HCMC were sensitized with human myeloma IgE (0.5 µg·mL−1), overnight at 37°C in IMDM in a 5% CO2 incubator. Sensitized HCMC were washed with HEPES-buffered Tyrode solution with 0.03% human albumin and incubated with AR agonists for 0 min or 10 min before challenged with anti-IgE (0.5 µg·mL−1). HCMC were only pre-incubated with adenosine for 10 min when activation with the calcium ionophore, A23187 (10−6 mol·L−1) was investigated. In antagonist studies, HCMC were pre-incubated with antagonists for 10 min before addition of AR agonists, and anti-IgE was added after 10 min. Histamine release was allowed to proceed for 30 min at 37°C following the addition of anti-IgE or A23187, and was stopped by addition of ice-cold buffer followed immediately by centrifugation. The cell pellets and supernatants were collected separately and histamine content was measured spectrofluorometrically using a Bran+Luebbe AutoAnalyzer 3 (Norderstedt, Germany). The percentage of total cellular histamine released into the supernatant was then calculated and expressed as [Histamine release (% total)] in Figures 1A and 2B. For facilitating comparison of the mast cell modulating actions of different AR ligands, all subsequent results were normalized against the anti-IgE-induced histamine release and expressed as the percentage of anti-IgE-induced histamine release (% of anti-IgE).

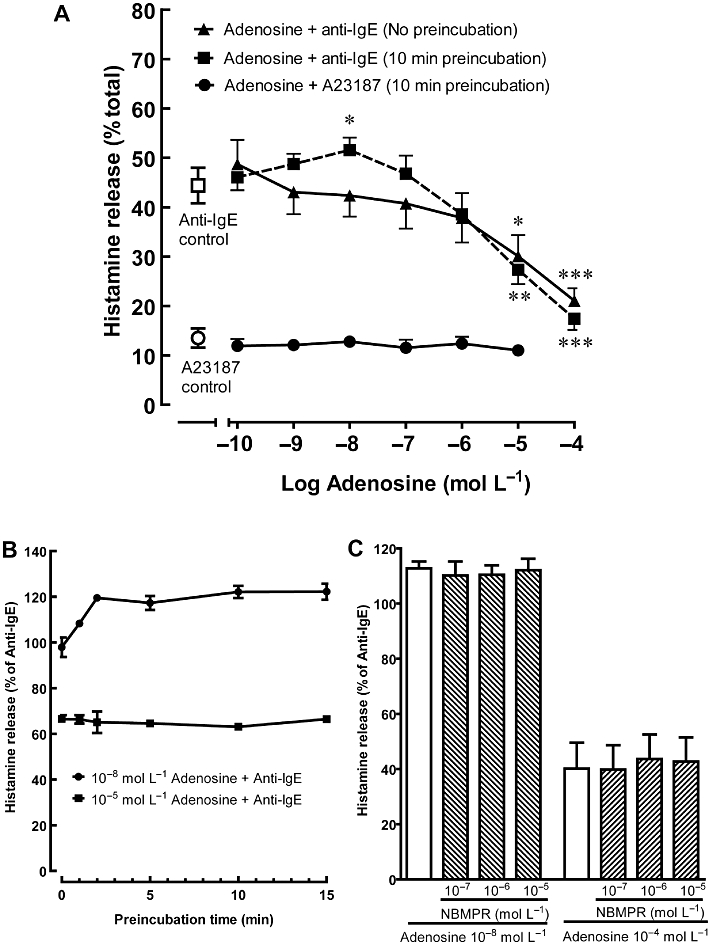

Figure 1.

Effects of adenosine on histamine release from activated HCMC. (A) Sensitized HCMC were incubated with adenosine for 0 (no pre-incubation) or 10 min prior to being challenged with anti-IgE (n = 5) or calcium ionophore A23187 (n = 3) for 30 min. The actual percentage of total cellular histamine released into the supernatant was listed. Significant differences between histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone and in the presence of adenosine are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (B) Sensitized HCMC were pre-incubated with adenosine (10−8 mol·L−1 for potentiation and 10−5 mol·L−1 for inhibition) for 0, 1, 2, 5, 10 and 15 min prior to being challenged with anti-IgE (n = 3). (C) HCMC were pre-incubated for 10 min with NBMPR and then subsequently incubated with 10−8 mol·L−1 or 10−4 mol·L−1 adenosine prior to being challenged with anti-IgE (n = 3). Results are expressed as a percentage of histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone (30.4–36.1% of total cellular histamine) for (B) and (C) and all values are mean ± SEM of the number of experiments indicated.

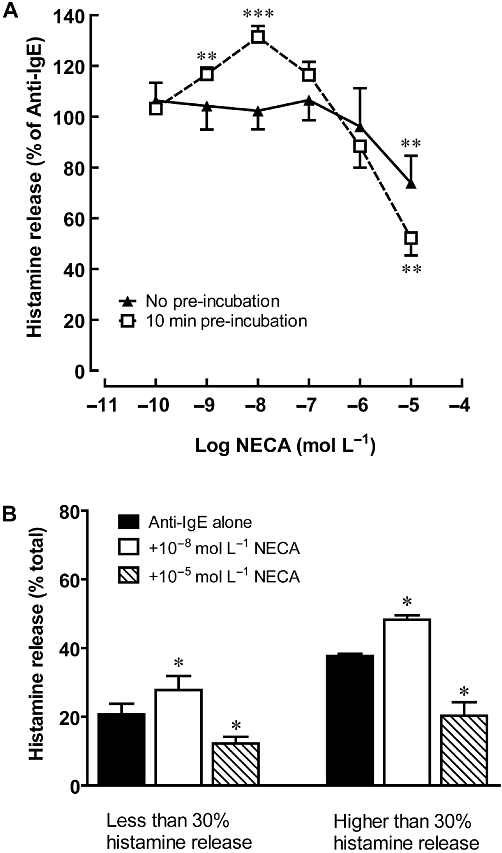

Figure 2.

Effects of NECA on anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC. (A) Sensitized HCMC were incubated with NECA for 0 (no pre-incubation) or 10 min prior to being challenged with anti-IgE for 30 min. Results are expressed as a percentage of histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone (28.8–43.8% of total cellular histamine). Significant differences between histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone and in the presence of NECA are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (n = 5). (B) The degree of modulation produced by 10 min pre-incubation with NECA was compared in low-responding HCMC (20.7 ± 3.1% histamine release, n = 6) and high-responding HCMC (37.7 ± 0.7% histamine release, n = 5). The actual percentage of total cellular histamine released into the supernatant was listed. *P < 0.05 indicates significant differences between histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone and in the presence of NECA.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed where appropriate using anova with Bonferroni's post-test by comparing the actual levels of histamine release, with the exception of Figure 2B where Student's t-test was used.

Results

Effects of adenosine and NECA on histamine release from HCMC

Incubation of HCMC with adenosine or NECA (10−10 mol·L−1 to 10−4 mol·L−1) had no effect on basal histamine release, which was generally less than 7% of total cellular histamine. However, when added to HCMC at the time of anti-IgE challenge, adenosine inhibited histamine release from HCMC in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A). Anti-IgE-induced histamine release was reduced to 45.5 ± 5.8% of the control level in the presence of 10−4 mol·L−1 adenosine (P < 0.001). Hughes et al. (1984) and our earlier study (Yip et al., 2009) demonstrated that varying the time of adenosine addition, with respect to immunological challenge, changed the modulatory function of adenosine. Accordingly, when HCMC were incubated with adenosine (10−8 mol·L−1) 10 min prior to anti-IgE challenge, anti-IgE-induced histamine release was enhanced by 13.9 ± 3.3% (P < 0.01), while inhibition was only observed at concentrations above 10−6 mol·L−1 (Figure 1A). Furthermore, when histamine release was induced by the calcium ionophore A23187, adenosine failed to induce any modulatory action (Figure 1A). The potentiating action of adenosine on anti-IgE-induced histamine release became significant after 2 min pre-incubation with 10−8 mol·L−1 adenosine and remained at a similar level even when the pre-incubation period was extended to 15 min (Figure 1B). As for the inhibitory action of 10−5 mol·L−1 adenosine, it was observed without pre-incubation and remained at the same level after 15 min pre-incubation. To determine whether the mast cell modulating actions of adenosine were mediated by an interaction with cell surface receptors, the adenosine uptake inhibitor NBMPR was added 10 min before addition of adenosine. As illustrated in Figure 1C, NBMPR failed to affect the adenosine-mediated potentiation and inhibition of anti-IgE-induced histamine release. Similar to adenosine, the non-selective AR agonist NECA also produced a time-dependent biphasic action on anti-IgE-activated HCMC (Figure 2A). When added at the time of anti-IgE activation, NECA demonstrated only an inhibitory effect, and anti-IgE-induced histamine release was reduced to 67.5 ± 6.2% (P < 0.01) in the presence of 10−5 mol·L−1 NECA. As seen with responses to adenosine, potentiation of histamine release was observed when HCMC were pre-incubated with 10−9 mol·L−1 and 10−8 mol·L−1 NECA for 10 min before stimulation with anti-IgE. NECA at 10−8 mol·L−1 produced a significant enhancement of anti-IgE-induced histamine release, 29.5 ± 4.2% (P < 0.001), while an inhibitory action was observed at concentrations above 10−7 mol·L−1. To investigate whether the biphasic action of non-selective AR agonists is altered by the degree of mast cell activation, we compared the effects of NECA on HCMC that released above 30% of their total cellular histamine with those that released less than 30%. For both groups of HCMC, adenosine produced comparable levels of potentiation and inhibition at 10−8 mol·L−1 and 10−5 mol·L−1, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 2B, anti-IgE-induced histamine release was increased to 136.8 ± 7.8% and 128.2 ± 3.0% of control by 10−8 mol·L−1 NECA in the low and high responders, respectively. As for the degree of inhibition produced by 10−5 mol·L−1 NECA, it was 65.0 ± 11.6% and 53.4 ± 9.7% of control for the low and high responders, respectively.

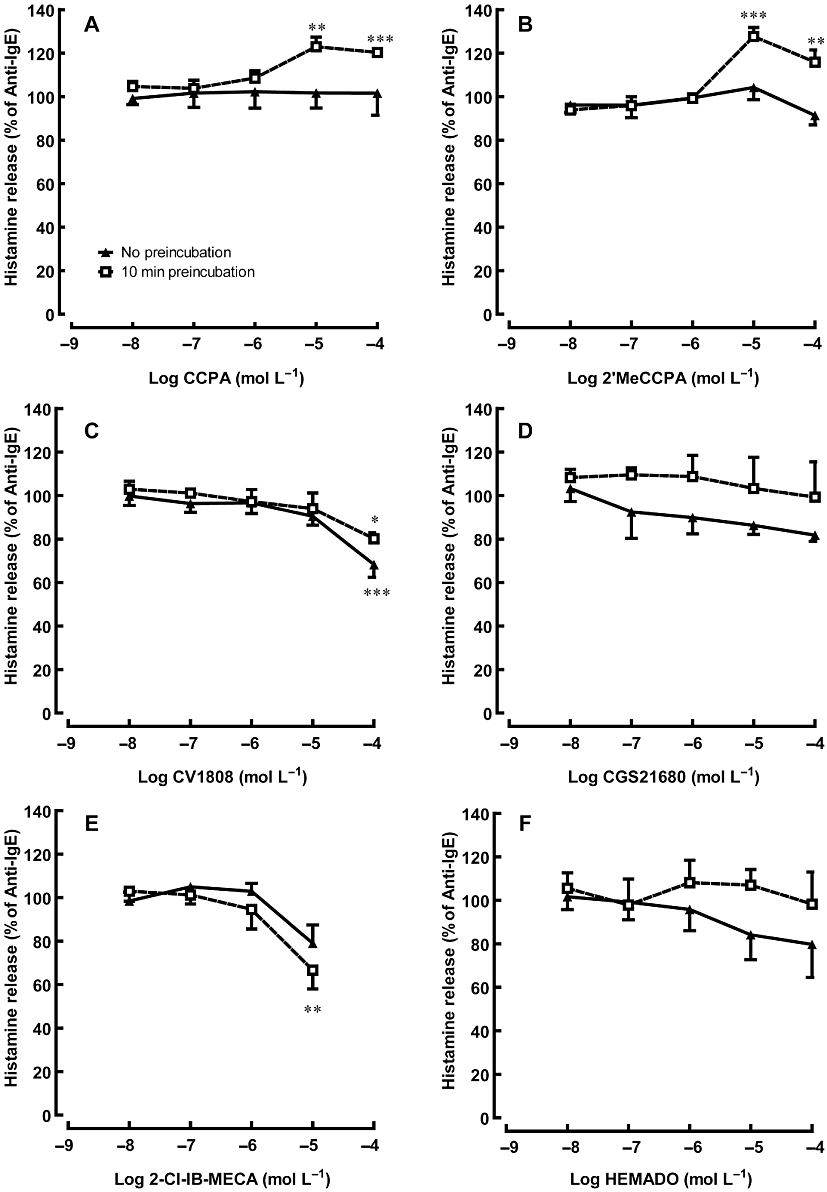

Effects of AR agonists on anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC

The AR agonists tested in the current study were selected according to their reported affinity or potency at the various AR subtypes, as listed in Table 1. All the agonists when tested alone did not affect basal histamine release from HCMC. Among them, only high concentrations of the A1 AR agonists, CCPA and 2'MeCCPA, induced a significant enhancement of HCMC activation when they were pre-incubated with HCMC for 10 min before anti-IgE challenge (Figure 3). Anti-IgE-induced histamine release was increased by 22.9 ± 4.5% (P < 0.01) and 27.7 ± 4.1% (P < 0.001) in the presence of CCPA and 2'MeCCPA (10−5 mol·L−1), respectively (Figure 3A and B). As with adenosine and NECA, this enhancing effect was not observed when the agonists were added to HCMC at the time of anti-IgE stimulation. In a separate experiment involving three independent samples from different donors, the potentiating action of 10−5 mol·L−1 2'MeCCPA (increased anti-IgE-induced histamine release to 126.7 ± 5.7% of control, P < 0.05 vs. anti-IgE control) was significantly attenuated (105 ± 3.9% of anti-IgE-induced histamine release) in the presence of 10−6 mol·L−1 PSB36, an A1 AR-specific antagonist, but not by 10−6 mol·L−1 of the A3 AR-specific antagonist MRS 3777.

Table 1.

Affinity values of agonists and antagonists at human adenosine receptor subtypes

| A1 | A2A | A2B | A3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ki (nmol·L−1) | References | ||||

| Agonist | |||||

| Adenosine | 310aa | 730aa | 23 500aa | 290aa | (Fredholm et al., 2001b) |

| NECA | 14 | 20 | 2 400aa | 6.2 | (Klotz, 2000) |

| CCPA | 0.83 | 2 270 | 18 800 | 38 | (Jacobson and Gao, 2006) |

| 2'MeCCPA | 3.3 | 9580 | 37 600 | 1 150 | (Cappellacci et al., 2005) |

| CGS21680 | 290 | 27 | 88 800aa | 67 | (Klotz, 2000) |

| CV1808 | N.D. | 76a | N.D. | 1 450b | a(Dionisotti et al., 1997) |

| b (Varani et al., 1998) | |||||

| 2-Cl-IB-MECA | 220 | 5 360 | >100 000 | 0.33 | (Jacobson and Gao, 2006) |

| HEMADO | 327 | 1 230 | >100 000 | 1.1 | (Klotz et al., 2007) |

| Antagonists | |||||

| CGS15943 | 3.5 | 4.2 | 16 | 51 | (Fredholm et al., 2001a) |

| PSB36 | 0.12 | 552 | 187 | 2 300 | (Weyler et al., 2006) |

| SCH442416 | 1 111 | 0.048 | >10 000 | >10 000 | (Moro et al., 2006) |

| PSB1115 | >10 000 | 24 000 | 53.4 | >10 000 | (Moro et al., 2006) |

| MRS1706 | 403 | 503 | 2 | 570 | (Moro et al., 2006) |

| MRS3777 | >10 000 | >10 000 | >10 000 | 47 | (Jacobson and Gao, 2006) |

Data were collected from various references listed. ND = Not determined.

EC50 values of agonists at human adenosine receptors were determined in a functional assay using changes in cAMP formation in CHO cells stably transfected with the human A1, A2A, A2B, and A3 receptors.

Ki values were obtained from binding experiments at recombinant human A1, A2A, A2B and A3 adenosine receptors.

Figure 3.

Effects of adenosine receptor agonists on anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC. Sensitized HCMC were incubated with an adenosine receptor agonist for 0 (no pre-incubation) or 10 min prior to being challenged with anti-IgE for 30 min. Adenosine agonists used were: (A, B) selective A1 adenosine receptor agonists CCPA and 2'MeCCPA (C) A2 adenosine receptor agonists CV1808 (D) selective A2A adenosine receptor agonist CGS21680 and (E, F) selective A3 adenosine receptor agonists 2-Cl-IB-MECA and HEMADO. Significant differences between the histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone and in the presence of adenosine receptor agonists are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results are expressed as a percentage of histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone (28.6–41.6% of total cellular histamine) and all values are mean ± SEM of four experiments.

In contrast to the A1 AR agonists, the non-selective A2 AR agonist CV1808 demonstrated an inhibitory effect on anti-IgE-induced activation at 10−4 mol·L−1, which was not observed with the A2A AR agonist CGS21680 (Figure 3C and D). Although the A3 AR agonist 2-Cl-IB-MECA significantly reduced anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC at 10−6 mol·L−1 (Figure 3E), the other A3 AR agonist HEMADO did not demonstrate any significant mast cell modulatory effect (Figure 3F). In a separate set of experiments involving three independent samples from different donors, the inhibitory action of 10−5 mol·L−1 2-Cl-IB-MECA (reduced anti-IgE-induced histamine release to 73.8 ± 6.7% of control, P < 0.05 vs. anti-IgE control) was blocked by 10−6 mol·L−1 of the specific A2B AR antagonist, PSB 1115, with anti-IgE-induced release restored to 90.3 ± 4.8% of control, but not by 10−6 mol·L−1 of the A3 AR specific antagonist, MRS 3777.

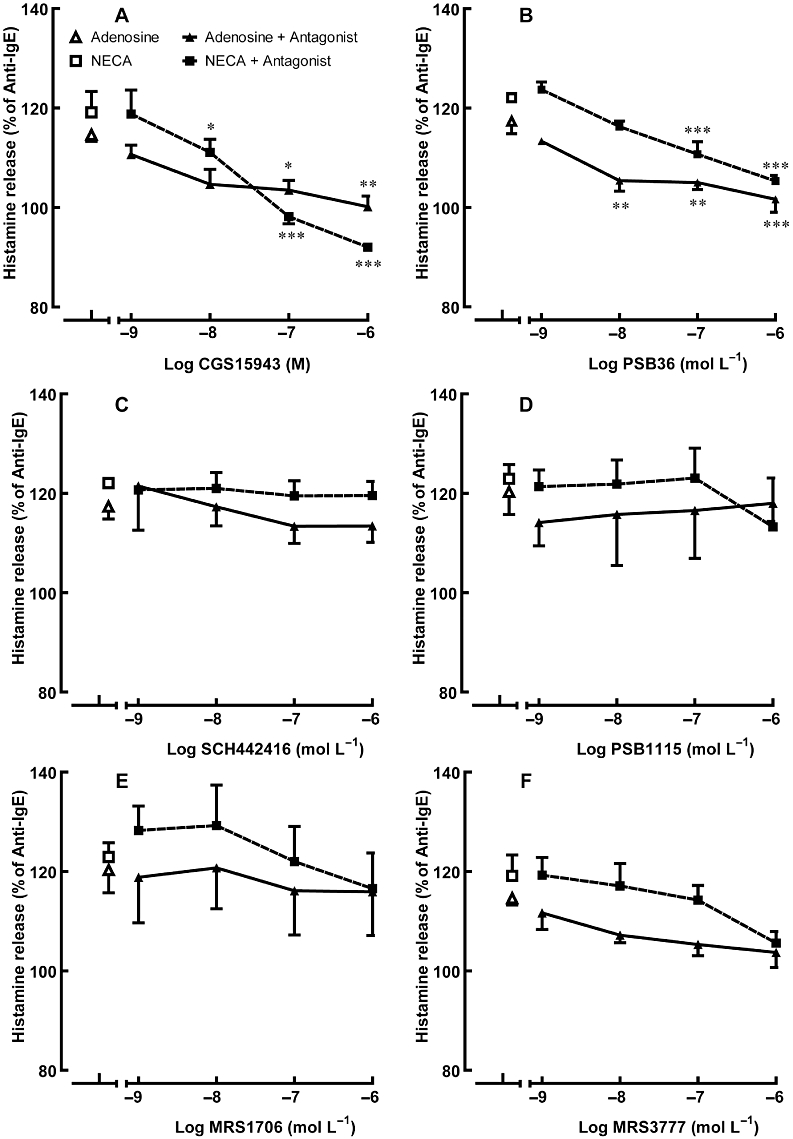

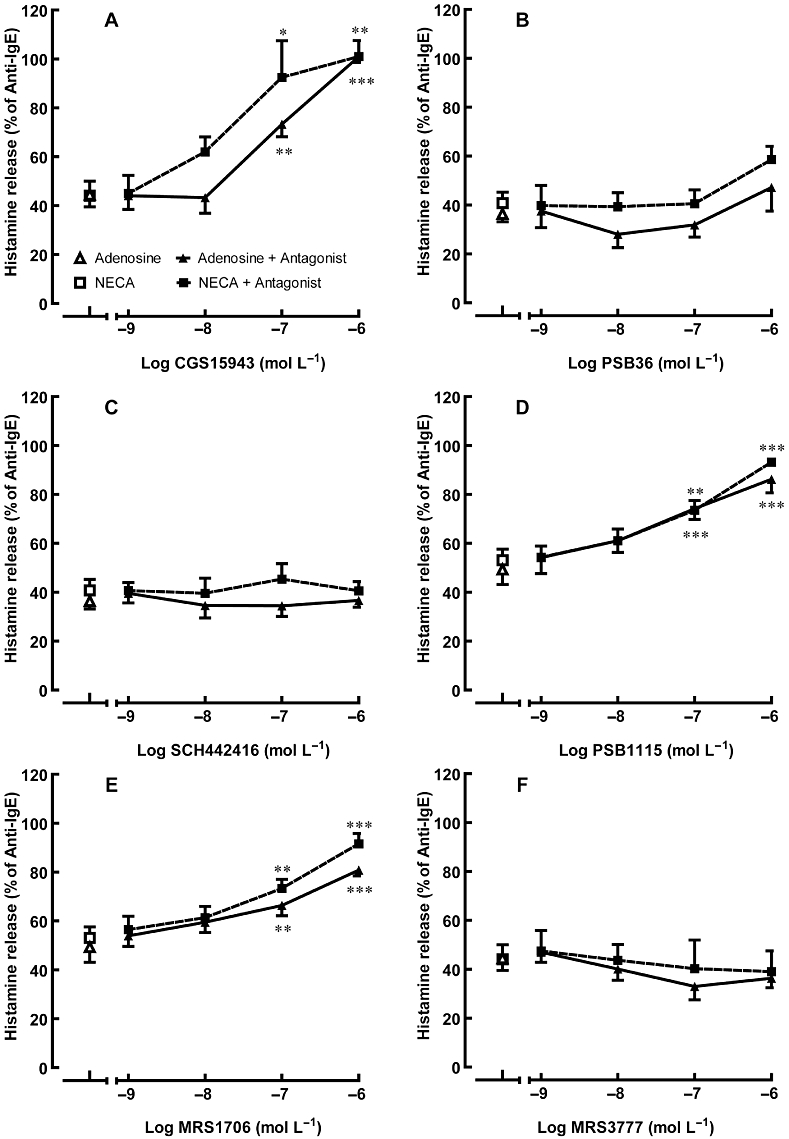

Effects of AR antagonists on adenosine and NECA-mediated effects on HCMC activation

The antagonists tested in the current study were selected according to their reported affinity for the various AR subtypes, as listed in Table 1. None of the antagonists alone affected basal or anti-IgE-induced histamine release. Instead of studying their effects on the whole concentration-response curves of adenosine or NECA, the effects of the antagonists on the potentiating action produced by 10−4 mol·L−1 adenosine or 10−5 mol·L−1 NECA and the inhibitory action produced by 10−8 mol·L−1 of adenosine or NECA on anti-IgE-induced histamine release following 10 min pre-incubation with these agonists were investigated. Both actions of adenosine and NECA on activated HCMCs were significantly attenuated by the non-selective adenosine AR antagonist CGS15943, in a concentration-dependent manner (Figures 4A and 5A). The potentiating actions of adenosine and NECA, were concentration-dependently antagonized by the A1 AR antagonist, PSB36, but not by the A2A antagonist, SCH442416 and the A2B AR antagonists, PSB1115 and MRS1706 (Figure 4B–E). The potentiation of histamine release was almost completely abolished at the highest concentration of PSB36 tested (Figure 4B). Although the A3 AR antagonist MRS3777 slightly reduced the enhancing actions of adenosine and NECA, the effect was not statistically significant (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Effect of adenosine receptor antagonists on adenosine/NECA-mediated potentiation of anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC. Sensitized HCMC were pre-incubated with an adenosine receptor antagonist for 10 min and then subsequently with 10−8 mol·L−1 adenosine or 10−8 M NECA for 10 more min prior to being challenged with anti-IgE for 30 min. Adenosine receptor antagonists used were: (A) the non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist CGS15943 (B) the selective A1 adenosine receptor antagonist PSB36 (C) the selective A2A adenosine receptor antagonist SCH442416 (D, E) selective A2B adenosine receptor antagonists PSB1115 and MRS1706, respectively, and (F) the selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonist MRS3777. Significant differences between the percentage of anti-IgE-induced histamine release in adenosine/NECA alone and in the presence of adenosine/NECA with adenosine receptor antagonists are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results are expressed as a percentage of histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone (28.5–48.3% of total cellular histamine) and all values are mean ± SEM of four experiments.

Figure 5.

Effect of adenosine receptor antagonists on adenosine/NECA-mediated inhibition of anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC. Sensitized HCMC were pre-incubated with an adenosine receptor antagonist for 10 min and then subsequently with 10−4 mol·L−1 adenosine or 10−5 mol·L−1 NECA for 10 more minutes prior to being challenged with anti-IgE for 30 min. Adenosine receptor antagonists used were: (A) the non-selective adenosine receptor antagonist CGS15943 (B) the selective A1 adenosine receptor antagonist PSB36 (C) the selective A2A adenosine receptor antagonist SCH442416 (D, E) selective A2B adenosine receptor antagonists PSB1115 and MRS1706, respectively, and (F) the selective A3 adenosine receptor antagonist MRS3777. Significant differences between the percentage of anti-IgE-induced histamine release in adenosine/NECA alone and in the presence of adenosine/NECA with adenosine receptor antagonists are indicated by asterisks: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Results are expressed as a percentage of histamine release induced by anti-IgE alone (28.5–48.3% of total cellular histamine) and all values are mean ± SEM of four experiments.

The inhibitory effects of adenosine and NECA were prevented by the selective A2B AR antagonists, PSB1115 and MRS1706 (Figure 5D and E). The level of anti-IgE-induced histamine release was restored to 80–90% of that produced by anti-IgE alone in the presence of either A2B antagonist at 10−6 mol·L−1. In contrast, the A1, A2A and A3 AR antagonists all failed to attenuate the inhibitory effect of adenosine and NECA (Figure 5B, C and F, respectively).

Discussion

We have previously reported preliminary results, which demonstrated that adenosine was able to produce a biphasic modulation of anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC (Yip et al., 2009). Our current results extend these observations to include the effect of the more potent non-selective AR agonist NECA. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that both adenosine and NECA at concentrations above 10−6 mol·L−1 produced a predominantly inhibitory effect on HCMC activation induced by anti-IgE challenge. A potentiating effect was observed at 10−8 mol·L−1 only after HCMC were pre-incubated with these non-selective AR agonists for 10 min prior to anti-IgE challenge. Although the inhibitory action required no prior incubation with AR agonists, the development of the potentiating effect was time-dependent; optimal potentiation was reached after 2 min pre-incubation with adenosine prior to anti-IgE-induced activation (Figure 1B). Furthermore, neither the degree of potentiation nor inhibition was affected by the level of anti-IgE-induced histamine release, as demonstrated in Figure 2B. The effects of adenosine and NECA observed in our current study are similar to those previously reported for highly purified dispersed HLMC in which NECA demonstrated a biphasic action on anti-IgE-induced histamine release (Peachell et al., 1991), and thus, further support our previous observations that our cultured human mast cells are functionally similar to primary HLMCs (Wang et al., 2006a). As histamine release induced by the calcium ionophore A23187 was not affected by adenosine, the mast cell modulatory action of adenosine is specific for the IgE receptor-mediated signalling that precedes the influx of calcium. The concentration-dependent biphasic effect on anti-IgE-induced histamine release induced by both adenosine and NECA suggests the activation of AR subtypes with different affinity for these ligands (Calabrese, 2001). The inhibition of the biphasic action of adenosine by the non-selective AR antagonist CGS15943 confirms that adenosine specifically interacts with ARs in HCMC (Figures 4A and 5A). The failure of the adenosine uptake blocker NBMPR to effect the mast cell modulatory actions of adenosine (Figure 1C) and the fact that NECA is not a substrate of the adenosine transporter (Meester et al., 1998) suggest that these ARs are located in the cell membrane of HCMC. In our earlier study (Yip et al., 2009), we proposed that A1 and A2B ARs are involved in the modulatory action of adenosine on human mast cells. This hypothesis is now confirmed in the current investigation in which the effects of more agonists over a wider concentration range were studied and selective antagonists used.

The significant enhancement of HCMC activation by the A1 AR agonists, CCPA and 2'MeCCPA (Figure 3A and B), and the suppression of the effects of adenosine and NECA by the A1 AR antagonist PSB36 (Figure 4B), suggest that adenosine potentiates anti-IgE-induced histamine release from HCMC through activation of A1 ARs. Although the A3 AR antagonist MRS3777 also suppressed the potentiating action of adenosine, this effect was not statistically significant and required high concentrations of this antagonist (Figure 4F). The ineffectiveness of the two specific A3 AR agonists to enhance anti-IgE-induced histamine release further rules out the involvement of the A3 AR (Figure 3E and F). A direct correlation between A1 AR and human mast cell activation has not been previously reported, but A1 AR was suggested to promote adenosine-induced hyper-responsiveness and allergen-induced early and late phase allergic responses in a hyper-responsive rabbit model of asthma (Ali et al., 1994; Obiefuna et al., 2005). Moreover, A1 AR expression was found to be markedly up-regulated in bronchial tissue obtained from subjects with asthma who are responsive to AMP challenge (Brown et al., 2008a). Stimulation of the A1 AR leads to inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity through Gαi-protein and activation of PLC through the βγ subunit (Jacobson and Gao, 2006). It is well known that activation of PLC generates metabolites that trigger the mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ stores and subsequently opening of Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane. The increase in intracellular calcium consequently initiates the degranulation process of mast cells (Bradding, 2005). As calcium ionophores directly transport extracellular calcium into the cytosol, the failure of adenosine to affect histamine release induced by A23187 supports the involvement of such early calcium elevation mechanisms, which are bypassed by A23187, in the activation of A1 AR. These signalling events are capable of up-regulating IgE receptor-mediated mast cell activation and may help to explain the observed potentiating effect of A1 AR agonists on HCMC.

Both adenosine and NECA bind to the A1 ARs with high affinity and this corresponds to the low concentrations required for producing the potentiating action observed in the current study. However, the requirement of at least 10−5 mol·L−1 of the specific A1 AR agonists, CCPA and 2'MeCCPA (both with Ki values of around 10−9 mol·L−1 for A1 AR), to produce a significant potentiating effect, is unexpected. Despite these high concentrations, the potentiating effect demonstrated by the A1 AR agonists were confirmed to be mediated through A1 AR as this effect was totally suppressed by the A1 AR specific antagonist PSB36 (Figure 4B), but not by the A3 AR antagonist MRS3777 (Figure 4F). It is also interesting to note that the inhibitory potency of CV1808 (Figure 3C) and the inhibitory tendency of high concentrations of CGS21680 and HEMADO (Figure 3D and F, respectively) were less apparent in cells that were activated after 10 min pre-incubation with these agonists. At concentrations above micromolar, these AR agonists would be non-selective and are likely to induce a time-dependent activation of A1 AR, which would produce a potentiating effect that would counteract the more dominant suppressive action mediated at the same time by the A2B AR.

The lower potency of the two A1 AR agonists than that anticipated and the time-dependent characteristic of the A1 AR-mediated action may be due to the location of the receptors in the cell membrane. In cardiomyocytes, A1 ARs have been found to be localized in lipid rafts/caveolae under basal conditions (Lasley et al., 2000; Cavalli et al., 2007). Upon the addition of agonists, A1 ARs were shown to translocate out of the caveolae and disperse into the general plasma membrane (Lasley et al., 2000). The exact function of this translocation process is not known, but it can be prevented by prior incubation of the myocytes with the A1 AR antagonist, 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine. The lack of potentiating action of adenosine, NECA or the specific A1 AR agonists when added to HCMC at the time of anti-IgE-induced activation may thus be due to the time required for the A1 ARs to translocate from the caveolae to the plasma membrane, where they can functionally interact with the IgE receptor-mediated signalling pathways. As for the lower potency of the two A1 agonists, it may be caused by difficulties of these ligands in reaching the A1 ARs in the caveolae. Obviously, further studies are required to confirm this hypothesis. The physiological concentration of adenosine in tissues is reported to be in the range of 0.5–2 × 10−7 mol·L−1 (Latini et al., 2001), and activation of the A1 AR on human mast cells at the initiation of an allergic reaction could serve the purpose of accentuating the IgE receptor-mediated activation to provide a more substantial stimulation of the immunological response against the potentially harmful exogenous allergen.

Elevation of intracellular cAMP leads to the suppression of human mast cell activation (Peachell et al., 1988), suggesting a role for Gαs coupled A2 AR in the inhibitory actions of adenosine and NECA. The A2B AR subtype is likely to be involved, as the high concentrations of adenosine and NECA required to significantly suppress anti-IgE-induced histamine release correlate with the low affinity of these ligands for A2B AR. This hypothesis was supported by the observation that significant inhibition of anti-IgE-induced histamine release was induced only by the non-selective A2 AR agonist CV1808 (Figure 3C), but not by the A2A AR selective agonist CGS21680 (Figure 3D) even at 10−4 mol·L−1. NECA is currently the most potent agonist of A2B AR, while CV1808 and CGS21680 have been shown to be 108- and 626-fold less potent than NECA, respectively, in a study investigating the potency of A2 AR agonists in guinea pig (Gurden et al., 1993). It is, thus, not surprising that significant inhibition of anti-IgE-induced histamine release by CV1808 was observed only at 10−4 mol·L−1 (Figure 3C), whereas 10−6 mol·L−1 NECA (Figure 2A) was required to produce a similar effect. The definitive evidence for the involvement of A2B AR comes from the observation that only the selective A2B AR antagonists, PSB1115 and MRS1706 (Figure 5D and E), but not the selective A2A AR antagonist SCH442416 (Figure 5C), demonstrated concentration-dependent attenuation of the inhibitory effect of adenosine and NECA. The reduction of anti-IgE-induced histamine release by 10−5 mol·L−1 of the A3 AR agonist 2-Cl-IB-MECA (Figure 3E) was also mediated through the A2B AR, as this effect was attenuated by 10−6 mol·L−1 PSB 1115.

Our results demonstrate and confirm for the first time that the A2B AR is associated with an inhibitory action of adenosine in human mast cells. However, our findings contrast with those from an earlier study in cord blood derived human mast cells (CBMC) in which it was reported that the inhibitory action of adenosine was mediated through the A2A AR (Suzuki et al., 1998). The discrepancy may be due to intrinsic differences between mast cells cultured from these two sources. CBMC are regarded as less suitable than peripheral blood derived mast cells as a tool for studying physiological and pathological characteristics of human mast cells due to their lower content of histamine and incomplete expression of IgE receptors (Andersen et al., 2008). Moreover, the significance of the CBMC study is questionable as the conclusion was based on only two independent experiments employing limited pharmacological tools. Although it was reported that the A2A AR antagonist, ZM241383, could attenuate adenosine-induced inhibition of human mast cell activation at concentrations above 10−8 mol·L−1, this effect could still be mediated through A2B ARs as the pA2 of this antagonist at the A2B AR is around 7.5 (Prentice et al., 1997).

According to studies employing primary human tissue or cultured mast cells, adenosine does not directly induce release of mediators. In contrast, studies with the mast cell like HMC-1 cell line have demonstrated that adenosine can directly induce IL-8 release through Gαq protein coupled signalling pathways (Feoktistov et al., 1995; 1999). HMC-1 cells are derived from a highly malignant, undifferentiated human mastocytoma cancer and are regarded as atypical mast cells as they do not possess functional IgE receptors. The relevance of the direct activating action of adenosine in HMC-1 cells to the roles of adenosine in IgE immunologically-sensitized human mast cells in allergic asthma is thus doubtful (Wilson et al., 2009). Although some studies using bronchoalveolar (BAL) fluid attempted to provide indirect evidence to support the hypothesis that mast cells in the BAL fluid of atopic asthmatic patients are particularly sensitive to the stimulating action of adenosine due to the presence of Gαq coupled A2B ARs (Forsythe et al., 1999), the BAL fluid contains other cells in addition to mast cells, and an additional signal from these contaminating cells might have acted to promote mast cell stimulation by adenosine (Brown et al., 2008b). Further studies are required to confirm the existence of Gαq coupled A2B ARs in purified BAL mast cells of atopic asthmatic patients and to explain why BAL mast cells of normal subjects do not have this property; inhaled adenosine does not induce bronchoconstriction in them.

The suppression of mast cell activation by adenosine through Gs-coupled A2B ARs has recently also been demonstrated in mice (Hua et al., 2007). Murine bone marrow derived mast cells obtained from A2B AR-deficient mice were reported to have reduced basal levels of cAMP and to produce an excessive influx of extracellular calcium through store-operated calcium channels following antigen activation. The functional role of A2B ARs was further demonstrated by the observed increased sensitivity to IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in mice lacking these receptors. The authors thus conclude that the response of mast cells towards antigen stimulation was limited by modulation of the IgE receptor-induced signalling pathways by A2B AR. A more recent study in a murine model of endotoxin-induced lung injury has further confirmed a general protective effect of A2B AR against pulmonary inflammation (Schingnitz et al., 2010). Pharmacological suppression of A2B ARs by the specific A2B AR antagonist MRS 1754 or genetic deletion of the A2B AR in functional studies of LPS-induced lung injury resulted in dramatic increases in lung inflammation and histological tissue injury. Furthermore, pretreatment of mice with a specific A2B AR agonist (BAY 60-6583) significantly attenuated lung inflammation and pulmonary oedema in wild-type, but not in A2B AR-deficient mice. During an inflammatory response the local concentration of adenosine in tissues has been reported to exceed micromolar concentrations (Driver et al., 1993), and this would allow the relatively insensitive A2B AR to be activated with the consequence of turning on the associated anti-inflammatory and tissue protective signalling in various acute inflammatory conditions.

In conclusion, our studies using HCMC have confirmed the original observation in HLMCs that low concentrations of adenosine potentiate, while high concentrations of this nucleotide suppress IgE receptor-mediated histamine release from human mast cells (Peachell et al., 1991). In addition, we have provided the first direct evidence that the A1 and A2B ARs are responsible for the potentiating and suppressing actions of adenosine, respectively. Such effects are in accordance with the respective coupling of A1 and A2B ARs to Gαi and Gαs proteins. We also confirmed that adenosine does not stimulate normal, non-activated mast cells, and our results do not support a facilitating role of A2B ARs in human mast cell activation as proposed by studies employing HMC-1 cells. With reference to the propagation of allergen-induced inflammatory reactions, the enhancement of IgE-mediated mast cell activation by low physiological concentrations of adenosine through the high affinity A1 AR would be important in amplifying the immediate immunological response against an invading allergen, whereas the suppression of mast cell activation induced by a high level of adenosine through A2B ARs would serve to limit the extent of inflammation and prevent excessive tissue damage. Although current research suggests that A2B AR antagonists are potentially useful in the control of asthma (Brown et al., 2008b), inhibition of mast cell activation, as indicated by our results, does not seem to be a part of their mechanism of action. Alternatively, unjustified use of A2B antagonists in non-asthmatic subjects may jeopardize the protective effect of A2B ARs against endotoxin-induced pulmonary inflammation. Our findings further suggest that the development of A1 AR antagonists as anti-asthmatic agents may reduce the contribution of mast cells to allergen-induced asthma. Finally, one cannot rule out the possibility that airway mast cells in asthmatic patients display different profiles of adenosine-mediated responses, but further studies are required to provide direct evidence.

Acknowledgments

This work was fully supported by the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (CUHK 4515/06M).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 2-Cl-IB-MECA

1-[2-chloro-6-[[(3-iodophenyl)methyl]amino]-9H-purin-9-yl]-1-deoxy-N-methyl-b-D-ribofuranuronamide

- 2′-MeCCPA

2-chloro-N-cyclopentyl-2′-methyladenosine

- AR

adenosine receptor, BAL, bronchoalveolar lavage

- CCPA

2-chloro-N6-cyclopentyladenosine

- CGS15943

9-chloro-2-(2-furanyl)-[1,2,4]triazolo [1,5-c]quinazolin-5-amine

- CGS21680

4-[2-[[6-amino-9-(N-ethyl-b-D-ribofuranuronam-idosyl)-9H-purin-2-yl]amino]ethyl]-benzenepropanoic acid hydrochloride

- CV1808

2-phenylaminoadenosine

- FcεRI

(IgE receptor)

- HCMC

human cultured mast cells

- HEMADO

2-(1-hexynyl)-N-methyladenosine

- IMDM

Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium

- MRS1706

N-(4-acetylphenyl)-2-[4-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1,3-dipropyl-1H-purin-8-yl)phenoxy]acetamide

- MRS3777

2-phenoxy-6-(cyclo-hexylamino) purine hemioxalate

- NBMPR

6-S-[(4-nitrophenyl)methyl]-6-thioinosine

- NECA

5′-N-ethylcarboxamidoadenosine

- PSB1115

4-(2,3,6,7-tetrahydro-2,6-dioxo-1-propyl-1H-purin-8-yl)-benzene-sulphonic acid potassium salt

- PSB36

1-butyl-8-(hexahydro-2,5-methanopentalen-3a(1H)-yl)-3,7-dihydro-3-(3-hydroxypropyl)-1H-purine-2,6-dione

- SCH442416

2-(2-furanyl)-7-[3-(4-methoxy-phenyl)-propyl]-7H-pyrazolo[4,3-e][1,2,4] triazolo[1,5-c]pyrmidin-5-amine

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- Alexander SP, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 4th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158(Suppl 1):S1–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali S, Mustafa SJ, Metzger WJ. Adenosine receptor-mediated bronchoconstriction and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in allergic rabbit model. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:L271–L277. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.3.L271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen HB, Holm M, Hetland TE, Dahl C, Junker S, Schiotz PO, et al. Comparison of short term in vitro cultured human mast cells from different progenitors – peripheral blood-derived progenitors generate highly mature and functional mast cells. J Immunol Methods. 2008;336:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berge M, Hylkema MN, Versluis M, Postma DS. Role of adenosine receptors in the treatment of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recent developments. Drugs R D. 2007;8:13–23. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200708010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradding P. Mast cell ion channels. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;87:163–178. doi: 10.1159/000087643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Clarke GW, Ledbetter CL, Hurle MJ, Denyer JC, Simcock DE, et al. Elevated expression of adenosine A1 receptor in bronchial biopsy specimens from asthmatic subjects. Eur Respir J. 2008a;31:311–319. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00003707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Spina D, Page CP. Adenosine receptors and asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2008b;153(Suppl 1):S446–S456. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese EJ. Adenosine: biphasic dose-responses. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2001;31:539–551. doi: 10.1080/20014091111811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappellacci L, Franchetti P, Pasqualini M, Petrelli R, Vita P, Lavecchia A, et al. Synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular modeling of ribose-modified adenosine analogues as adenosine receptor agonists. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1550–1562. doi: 10.1021/jm049408n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli A, Eghbali M, Minosyan TY, Stefani E, Philipson KD. Localization of sarcolemmal proteins to lipid rafts in the myocardium. Cell Calcium. 2007;42:313–322. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dionisotti S, Ongini E, Zocchi C, Kull B, Arslan G, Fredholm BB. Characterization of human A2A adenosine receptors with the antagonist radioligand [3H]-SCH 58261. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;121:353–360. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driver AG, Kukoly CA, Ali S, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:91–97. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Biaggioni I. Adenosine A2b receptors evoke interleukin-8 secretion in human mast cells. An enprofylline-sensitive mechanism with implications for asthma. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1979–1986. doi: 10.1172/JCI118245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feoktistov I, Goldstein AE, Biaggioni I. Role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase kinase in adenosine A2B receptor-mediated interleukin-8 production in human mast cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:726–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe P, Ennis M. Adenosine, mast cells and asthma. Inflamm Res. 1999;48:301–307. doi: 10.1007/s000110050464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe P, McGarvey LP, Heaney LG, MacMahon J, Ennis M. Adenosine induces histamine release from human bronchoalveolar lavage mast cells. Clin Sci (Lond) 1999;96:349–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, AP IJ, Jacobson KA, Klotz KN, Linden J. International Union of Pharmacology. XXV. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors. Pharmacol Rev. 2001a;53:527–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredholm BB, Irenius E, Kull B, Schulte G. Comparison of the potency of adenosine as an agonist at human adenosine receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001b;61:443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurden MF, Coates J, Ellis F, Evans B, Foster M, Hornby E, et al. Functional characterization of three adenosine receptor types. Br J Pharmacol. 1993;109:693–698. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb13629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm M, Andersen HB, Hetland TE, Dahl C, Hoffmann HJ, Junker S, et al. Seven week culture of functional human mast cells from buffy coat preparations. J Immunol Methods. 2008;336:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua X, Kovarova M, Chason KD, Nguyen M, Koller BH, Tilley SL. Enhanced mast cell activation in mice deficient in the A2b adenosine receptor. J Exp Med. 2007;204:117–128. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes PJ, Holgate ST, Church MK. Adenosine inhibits and potentiates IgE-dependent histamine release from human lung mast cells by an A2-purinoceptor mediated mechanism. Biochem Pharmacol. 1984;33:3847–3852. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(84)90050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inomata N, Tomita H, Ikezawa Z, Saito H. Differential gene expression profile between cord blood progenitor-derived and adult progenitor-derived human mast cells. Immunol Lett. 2005;98:265–271. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KA, Gao ZG. Adenosine receptors as therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:247–264. doi: 10.1038/nrd1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinger M, Freissmuth M, Nanoff C. Adenosine receptors: G protein-mediated signalling and the role of accessory proteins. Cell Signal. 2002;14:99–108. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(01)00235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz KN. Adenosine receptors and their ligands. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362:382–391. doi: 10.1007/s002100000315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz KN, Falgner N, Kachler S, Lambertucci C, Vittori S, Volpini R, et al. [3H]HEMADO-a novel tritiated agonist selective for the human adenosine A3 receptor. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;556:14–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasley RD, Narayan P, Uittenbogaard A, Smart EJ. Activated cardiac adenosine A(1) receptors translocate out of caveolae. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4417–4421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.4417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latini S, Pedata F. Adenosine in the central nervous system: release mechanisms and extracellular concentrations. J Neurochem. 2001;79:463–484. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston M, Heaney LG, Ennis M. Adenosine, inflammation and asthma–a review. Inflamm Res. 2004;53:171–178. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-1248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meester BJ, Shankley NP, Welsh NJ, Meijler FL, Black JW. Pharmacological analysis of the activity of the adenosine uptake inhibitor, dipyridamole, on the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes of the guinea-pig. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:729–741. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro S, Gao ZG, Jacobson KA, Spalluto G. Progress in the pursuit of therapeutic adenosine receptor antagonists. Med Res Rev. 2006;26:131–159. doi: 10.1002/med.20048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obiefuna PC, Batra VK, Nadeem A, Borron P, Wilson CN, Mustafa SJ. A novel A1 adenosine receptor antagonist, L-97-1 [3-[2-(4-aminophenyl)-ethyl]-8-benzyl-7-{2-ethyl-(2-hydroxy-ethyl)-amino]-ethyl}-1-propyl-3,7-dihydro-purine-2,6-dione], reduces allergic responses to house dust mite in an allergic rabbit model of asthma. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:329–336. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peachell PT, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Lichtenstein LM, Schleimer RP. Regulation of human basophil and lung mast cell function by cyclic adenosine monophosphate. J Immunol. 1988;140:571–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peachell PT, Lichtenstein LM, Schleimer RP. Differential regulation of human basophil and lung mast cell function by adenosine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1991;256:717–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters SP, Schulman ES, Schleimer RP, MacGlashan DW, Jr, Newball HH, Lichtenstein LM. Dispersed human lung mast cells. Pharmacologic aspects and comparison with human lung tissue fragments. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:1034–1039. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.6.1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips GD, Ng WH, Church MK, Holgate ST. The response of plasma histamine to bronchoprovocation with methacholine, adenosine 5′-monophosphate, and allergen in atopic nonasthmatic subjects. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141:9–13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/141.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prentice DJ, Payne SL, Hourani SM. Activation of two sites by adenosine receptor agonists to cause relaxation in rat isolated mesenteric artery. Br J Pharmacol. 1997;122:1509–1515. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramkumar V, Stiles GL, Beaven MA, Ali H. The A3 adenosine receptor is the unique adenosine receptor which facilitates release of allergic mediators in mast cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:16887–16890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schingnitz U, Hartmann K, Macmanus CF, Eckle T, Zug S, Colgan SP, et al. Signaling through the A2B adenosine receptor dampens endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. J Immunol. 2010;184:5271–5279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spicuzza L, Di Maria G, Polosa R. Adenosine in the airways: implications and applications. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:77–88. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H, Takei M, Nakahata T, Fukamachi H. Inhibitory effect of adenosine on degranulation of human cultured mast cells upon cross-linking of Fc epsilon RI. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;242:697–702. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varani K, Cacciari B, Baraldi PG, Dionisotti S, Ongini E, Borea PA. Binding affinity of adenosine receptor agonists and antagonists at human cloned A3 adenosine receptors. Life Sci. 1998;63:PL 81–PL 87. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Sam SW, Yip KH, Lau HY. Functional characterization of human mast cells cultured from adult peripheral blood. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006a;6:839–847. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XS, Yip KH, Sam SW, Lau HY. Buffy coat preparation is a convenient source of progenitors for culturing mature human mast cells. J Immunol Methods. 2006b;309:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weyler S, Fulle F, Diekmann M, Schumacher B, Hinz S, Klotz KN, et al. Improving potency, selectivity, and water solubility of adenosine A1 receptor antagonists: xanthines modified at position 3 and related pyrimido[1,2,3-cd]purinediones. Chem Med Chem. 2006;1:891–902. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200600066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson CN, Nadeem A, Spina D, Brown R, Page CP, Mustafa SJ. Adenosine receptors and asthma. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;193:329–362. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-89615-9_11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip KH, Wong LL, Lau HY. Adenosine: roles of different receptor subtypes in mediating histamine release from human and rodent mast cells. Inflamm Res. 2009;58(Suppl 1):17–19. doi: 10.1007/s00011-009-0647-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]