Abstract

The evolutionarily conserved TGF-β proteins are distributed ubiquitously throughout the body and have a role in almost every biological process. In immunity, TGF-β has an important role in modulating immunity. Much is understood about the process of TGF-β production as a latent molecule and of the consequences and the intercellular signaling of active TGF-β binding to its receptors; however, there is little discussed between the production and activation of TGF-β. This review focuses on what is understood about the biochemical and physiological processes of TGF-β activation and identifies the gaps in understanding immune cell activation of TGF-β. A mechanistic understanding of the process activating TGF-β can lead to regulating multiple biological systems by enhancing or inhibiting TGF-β activation.

Keywords: transforming growth factor-β, immune regulation, latent-associated

LATENT TGF-β

The protein TGF-β has multiple diverse and sometimes contradicting biological activity regulating cell function, proliferation, differentiation, and migration [1, 2]. It holds a role in modulating inflammation, wound repair, and immune homeostasis and tolerance [3]. Originally, TGF-β was discovered to be a growth factor that promoted anchorage-independent growth of fibroblasts [4]. The first defined, nontransforming role for TGF-β was that it promotes wound repair by augmenting collagen synthesis and angiogenesis [5,6,7,8]. Finally, it was found that TGF-β potently suppresses lymphocyte proliferation and is produced by activated lymphocytes [9,10,11,12]. Today, it is known that virtually every cell has the potential of producing TGF-β and responding to TGF-β and that TGF-β can influence every biological system tested in vivo and in vitro. An excellent, comprehensive review of TGF-β activity is found in ref. [13]. Mice with TGF-β1 knocked out, if they make it to birth, have a short life and suffer from extreme immunological disregulation [14]. Therefore, it is not surprising that if TGF-β has a central role in regulating cell functionality for survival and that TGF-β is found everywhere in the body then that itself is also highly regulated. This regulation is dominated not by the usual mechanisms of controlled production and expression of receptors, but by regulating the mechanisms that convert latent TGF-β to active TGF-β.

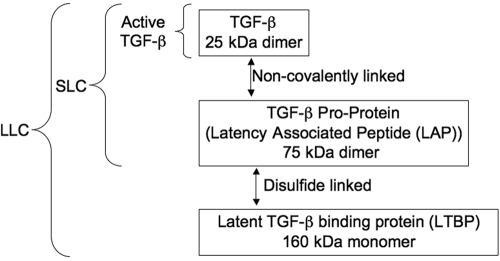

In mammals, there are three TGF-β genes coding for three different isoforms on separate chromosomes that are a little more than 70% homologous with each other [15,16,17,18,19]. Between mammals, the sequence homology within a given isoform can reach as high as 100%. The genes code for a protein of ∼50 kDa that dimerizes with the proprotein cleaved by the endopeptidase furin, but the dimeric proprotein remains noncovalently attached to the TGF-β 25-kDa dimeric protein [20, 21]. The covalently attached proprotein blocks TGF-β binding to its receptors, making the TGF-β latent [21]. The dimeric proprotein is called the latency-associated peptide (LAP). The LAP/TGF-β structure is the small latent TGF-β complex (SLC; Fig. 1), which remains in the cell until it is bound by a third protein product from a second gene, called the latent TGF-β-binding protein (LTBP) [22], a 125- to 160-kDa protein; one LTBP makes a disulfide bound to one of the chains of the LAP. The binding of one LTBP to the dimer of LAP/TGF-β makes up the LLC. It is the LLC that is secreted from cells that needs to be processed further to release active TGF-β [23]. Often the LLC is bound to collagen and other tissue matrix proteins through binding sites on the LTBP [24].

Figure 1.

Latent TGF-β complexes. Latent TGF-β is found in a SLC and in a large latent complex (LLC). The SLC is made of a dimerized single gene product of the TGF-β proprotein, noncovalently bound to the active TGF-β. The LLC is made of the LAP in the SLC, binding one molecule of the LTBP.

There are two groups of TGF-βRs. One group of receptors recognizes and binds LAP as part of the LLC or the SLC. These receptors are involved in mediating a conformational change in the LAP dimer that releases activated TGF-β. There will be more about these receptors later. The second group of receptors binds active TGF-β, which are separated into three types. The signal transduction is with the Type I and Type II receptors [25,26,27,28]. The Type III receptors are β-glycan and endoglin [26, 29]. Although there is no known associated, intracellular signaling pathway activated by the Type III receptors binding TGF-β, they do act as a sink, mopping up active TGF-β. When they are in a soluble form, they act as an inhibitor of active TGF-β, preventing TGF-β from binding the Type II receptor. When bound on the cell surface, the Type III receptor facilitates TGF-β binding to the Type II receptor by handing over the active TGF-β to the Type II receptor. Once the Type II receptors bind active TGF-β, there is recruitment of the Type I receptors. An activation complex is made of two pairs of Type II and Type I receptors, and each pair binds one of the two chains of active TGF-β [30]. Within this engagement of receptors and active TGF-β, the Type II receptor phosphorylates the Type I receptor [31]. The now-activated Type I receptor initiates the Smads intercellular signaling pathway, ending with the translocation of Smad4 into the nucleus to regulate genes with Smad-binding elements [32, 33]. Although there is an understanding as to the effects of TGF-β on gene expression and cell function and to the process of synthesizing TGF-β, there remains a gap in how or when TGF-β is activated.

ENZYME-MEDIATED TGF-β ACTIVATION

Activation of TGF-β requires the release of TGF-β from the LAP and the LTBP in the LLC. This process would involve the release of the LLC from the matrix it is attached to, followed by a conformational change or further proteolysis of the LAP to release TGF-β to its receptors. Laboratory methods of activating TGF-β take advantage of the biophysical properties of TGF-β to resist proteolysis and extreme pH conditions. The most common activation method is to treat conditioned media or biological fluids with a transient acid treatment that lowers the pH to 2.0 for a short period of time [34]. This method activates all of the TGF-β in a sample and can be compared with the same sample not transiently acidified to quantify and measure the level of activated and latent TGF-β in a sample. Other methods, such as freezing and thawing and adding plasmin or other proteases to degrade LAP, can activate TGF-β but are not as complete as transient acidification. Although for laboratory analysis, these methods are effective in activating TGF-β, the in vivo mechanisms are still speculative and may involve multiple activation pathways on the surface of cells. These laboratory procedures are effective in activating all isoforms of latent TGF-β.

The physiological activation of TGF-β may involve surface receptors and localized protease activity. The proteases such as metalloproteinases release the LLC from the tissue matrix [24, 35,36,37]. There is a hinge region in the LTBP between the matrix-binding domains and the remaining domains of the LTBP that include the LAP-binding domain [24]. This hinge region is exposed and readily cut by proteases. Once freed from the matrix, the LAP in the LLC can bind surface receptors and be acted on further by proteases or through conformational changes that release TGF-β. Here, plasmin is considered an important enzyme in the activation of TGF-β. The plasminogen conversion to plasmin can happen at the cell surface by a receptor-bound urokinase plasminogen activator or part of platelet activation [38]. The plasmin system of TGF-β activation was suspected to be the pathway by which TGF-β stored in platelets is activated and released in clot formations; however, platelet activation of TGF-β may more involve furin-like endopeptidases [39]. This pathway is the major reason for the high levels of TGF-β in serum, which can influence TGF-β-sensitive culture conditions containing serum.

RECEPTOR-MEDIATED TGF-β ACTIVATION

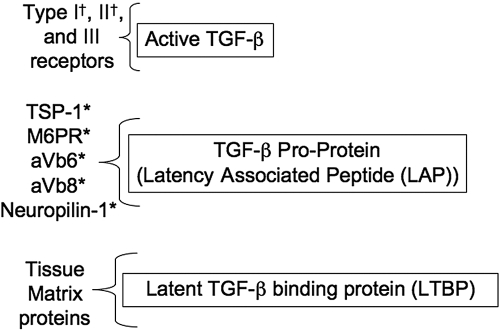

Although receptors for activated TGF-β have been known and characterized for some time, it is now becoming clear that there are receptors (Fig. 2) for LAP as part of the LLC and SLC [40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. The binding of LAP allows for cells to hold latent TGF-β on their surface, making it possible for cells to deliver active TGF-β in an autocrine or a paracrine manner to its own or another cell’s TGF-βRs. This is seen with activated macrophages binding on its surface latent TGF-β from the environment or from its own production and activating TGF-β, which in turn binds to the macrophage’s Type III TGF-βR [51]. Also, through this surface binding of LAP and release of activated TGF-β, one cell can bind LLC and release TGF-β to receptors on an adjacent cell. The most classic example of this is the exchange of TGF-β between smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells [52, 53]. This activation and then delivery of TGF-β from one cell to another cell are also the suggested mechanisms by which T regulatory cells (Tregs) may suppress the activity of other T cells [46, 54,55,56]. As this is at the cell surface, it makes the TGF-β activation pathway an additional type of intercellular communication and a mechanism by which adjacent cells can control each other’s activity [44].

Figure 2.

Receptors for TGF-β proteins. Each of the molecules of latent TGF-β has different binding proteins and receptors. Active TGF-β must be released from the latent complexes to bind its receptors. Binding of LAP does not require it to be released from LTBP. †, TGF-β receptors with intracellular signaling; *, LAP receptors that mediate conformational changes in LAP that release TGF-β. TSP-1, Thrompospondin-1; M6PR, mannose-6-phosphate receptor/insulin-like growth factor-II receptor.

There are several surface-binding proteins for LAP identified. They are TSP-1/CD36, M6PR, and multiple αV-containing integrins [41, 42, 49, 50]. These receptors are expressed on the surface of multiple cells involved in wound repair and inflammation such as macrophages, dendritic cells (DC), endothelial cells, myofibroblasts, and transformed cells. It is not clear if the SLC must be released from the LLC for LAP to bind its receptor or that the surface-bound, latent TGF-β is still part of the LLC with the LTBP cleaved from the matrix. It is likely that it is the LLC binding, as LAP is linked to LTBP through disulfide bonds that are not readily broken under physiological conditions. Although binding of LAP to the surface molecules leads to TGF-β activation through a protease-independent, conformational change, it is not possible to rule out proteases in the activation pathway. The receptor-binding pathways of TGF-β activation add another level of regulating TGF-β activity. Different cell types may use one or more of these LAP-binding receptors. This means that in considering TGF-β-dependent events, it is necessary to consider which LAP-binding receptor is used, whether the LAP receptors themselves are activated when they bind LAP [57], and what the effect of other ligands that can compete with LAP for the same binding site on the receptor.

Although there have been suggested several speculative pathways of TGF-β activation in vivo to explain TGF-β activity in wound repair, scar formation, and immune regulation, there are few reports that actually describe a clear activation pathway on monocytes and lymphocytes. An analysis of the literature suggests that the regulation of immunity by TGF-β may be dependent less on the proteolysis pathways of activation but more on cell-surface, LAP-binding receptors and conformational activation of TGF-β. Mice with TSP-1 knocked out have spontaneous lung inflammation [58], whereas, αVβ6 knockout mice have exaggerated skin and lung inflammation after irritation [59]. A double TSP-1/β6 knockout exhibits severe inflammation in the lungs and other tissues; also, they have an increase in cancer formations associated with knocking out β6 [43]. What has not been checked is to see if the immunosuppression mediated by activation of TGF-β by TSP-1 or αVβ6 is by acting directly on immune cells to suppress their inflammatory activity or that the activated TGF-β mediates induction of Tregs [60].

These findings suggest that the activation of TGF-β by TSP-1 and αVβ6 is part of tissue homeostasis but only if the biological activity is dependent on αVβ6-binding, latent TGF-β1, or latent TGF-β3 [48]. The LAP of TGF-β2 does not express the arginine-glycine-aspartate-binding sequence for binding integrins and TSP-1 [61]. Therefore, tissues that are dominantly TGF-β2, such as the ocular microenvironment, may have to use other mechanisms of activation or have an inefficient activation of TGF-β2.

Mice with the αVβ8 knocked out on their DC suffer from autoimmunity and colitis [47, 62]. There is a significant loss in the ability of these DC to induce activation of Treg, which is reversed with the addition of active TGF-β. Therefore, the induction or the maintenance of Tregs is potentially dependent on DC acquiring the LLC from the tissue environment or of their own production-binding LAP with their αVβ8 inducing a conformational change in LAP-releasing TGF-β to the TGF-βRs on a T cell, which is being activated though its TCRs. Also, this mechanism could be the manner by which active TGF-β is provided to other immune cells to suppress their inflammatory activity. In these mice, if the αVβ8 knock-down was targeted to T cells instead of the DC, the mice appeared phenotypically normal. Initial analysis revealed that there was no expression of β8 in CD8+ T cells, NK cells, B cells, and macrophages. The report showed that the loss of immune regulation is with the inability of the αVβ8 DC to activate TGF-β and mediate induction of Tregs. Although induction of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3)-positive cells can be induced when it is the T cell, not the DC, lacking expression of αVβ8. αVβ8 was not examined was whether the αVβ8-negative, FoxP3-positive T cell functions as Tregs?

TGF-β ACTIVATION AND Tregs

Active TGF-β is important for Tregs to mediate immunosuppression and function in maintaining peripheral tolerance [55, 63]. The Tregs make TGF-β, and blocking TGF-β activity prevents the Tregs from suppressing immunity. The localization of latent TGF-β on the cell membrane may very well be the mechanism by which Tregs interact with other T cells to deliver active TGF-β to suppress immunity [54].

How TGF-β is activated by Tregs to mediate immunosuppression is uncertain, but recent findings suggest that it is also a cell-surface activation pathway. It has been found that Tregs express LAP on their membrane surface [56]. The CD25+ CD4+ LAP+ T cells are more potent in regulatory activity than CD25+CD4+ LAP– T cells, and it is the LAP+ cells that are producing releasing-active TGF-β. This is not limited to only CD25+ CD4+ T cells, as CD25– CD4+ LAP+ T cells are also producers of active TGF-β and mediate immune regulation. This demonstrates that there must be a receptor for LAP as part of the LLC expressed on the surface of the CD4 T cells. This is interesting, as the usual LAP-binding receptors of CD36/TSP-1, αVβ6, are on monocytes, endothelial cells, and DC but not on T cells and that knocking out αVβ8 expression on CD4 T cells does not affect immunity. So far, the only clearly identified LAP-binding molecule on the LAP+ Tregs is the receptor Neuropilin-1 [46], which is a coreceptor for vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)/VEGFR, and VEGF can compete with LAP and be internalized; however, LAP has a much higher affinity with two binding sites on Neuropilin-1 than VEGF. There is some hint that other α-integrins other than αV may be a receptor for LAP on T cells [64]. This means that Tregs may use nonenzymatic pathways for TGF-β activation for the Treg to locally deliver active TGF-β to suppress immunity.

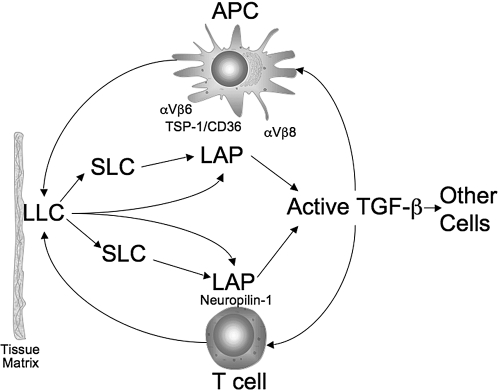

It is possible to place together a pathway of TGF-β production and activation in immune regulation and cellular activity (Fig. 3) [65]. The immune cells can be the source of the LLC, or the immune cells pick up the LLC released from the matrix or other cells. The binding of LAP on the surface of macrophages, DC, and T cells by their own sets of receptors results in a conformational change in the LAP-releasing, active TGF-β. The active TGF-β can be taken up by the Type III or Type II receptors on the same cell that has bound LAP or by the receptors on an adjacent or neighboring cell. The active TGF-β-bound Type II receptor pulls in the Type I receptor, forming the TGF-β/TGF-βR complex, and initiates the TGF-β intracellular signaling pathway.

Figure 3.

Potential pathway of TGF-β activation in immunity. Soluble LLC from cells or released from the matrix can be broken down further to the SLC or remain intact with LAP binding to specific receptors on the surface of APC and T cells. The bound LAP undergoes a conformational change, releasing active TGF-β, which can be taken up by Type III or Type II receptors on the same cell that has bound the LAP or by the receptors on adjacent and neighboring cells.

CONCLUSION

Although the list of the effects of TGF-β on immunity, cell growth, differentiation, and survival is documented extensively and continues to grow, there still lacks a clear understanding of the process of activating TGF-β. Without understanding the mechanisms of TGF-β activation, it is not possible to know when and how to intervene in immunity to augment or neutralize TGF-β activity.

References

- Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B. Transforming growth factor β. Adv Cancer Res. 1988;51:107–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. The transforming growth factor-β family. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1990;6:597–641. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.06.110190.003121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y. Y., Flavell R. A. “Yin-Yang” functions of transforming growth factor-β and T regulatory cells in immune regulation. Immunol Rev. 2007;220:199–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2007.00565.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Larco J. E., Todaro G. J. Growth factors from murine sarcoma virus-transformed cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4001–4005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.4001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignotz R. A., Massague J. Transforming growth factor-β stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation into the extracellular matrix. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:4337–4345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustoe T. A., Pierce G. F., Thomason A., Gramates P., Sporn M. B., Deuel T. F. Accelerated healing of incisional wounds in rats induced by transforming growth factor-β. Science. 1987;237:1333–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.2442813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Assoian R. K., Smith J. M., Roche N. S., Wakefield L. M., Heine U. I., Liotta L. A., Falanga V., Kehrl J. H., et al. Transforming growth factor type β: rapid induction of fibrosis and angiogenesis in vivo and stimulation of collagen formation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:4167–4171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporn M. B., Roberts A. B., Shull J. H., Smith J. M., Ward J. M., Sodek J. Polypeptide transforming growth factors isolated from bovine sources and used for wound healing in vivo. Science. 1983;219:1329–1331. doi: 10.1126/science.6572416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl S. M., Hunt D. A., Wong H. L., Dougherty S., McCartney-Francis N., Wahl L. M., Ellingsworth L., Schmidt J. A., Hall G., Roberts A. B., et al. Transforming growth factor-β is a potent immunosuppressive agent that inhibits IL-1-dependent lymphocyte proliferation. J Immunol. 1988;140:3026–3032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrl J. H., Roberts A. B., Wakefield L. M., Jakowlew S., Sporn M. B., Fauci A. S. Transforming growth factor β is an important immunomodulatory protein for human B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1986;137:3855–3860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kehrl J. H., Wakefield L. M., Roberts A. B., Jakowlew S., Alvarez-Mon M., Derynck R., Sporn M. B., Fauci A. S. Production of transforming growth factor β by human T lymphocytes and its potential role in the regulation of T cell growth. J Exp Med. 1986;163:1037–1050. doi: 10.1084/jem.163.5.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assoian R. K., Fleurdelys B. E., Stevenson H. C., Miller P. J., Madtes D. K., Raines E. W., Ross R., Sporn M. B. Expression and secretion of type β transforming growth factor by activated human macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:6020–6024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. O., Wan Y. Y., Sanjabi S., Robertson A. K., Flavell R. A. Transforming growth factor-β regulation of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:99–146. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni A. B., Huh C. G., Becker D., Geiser A., Lyght M., Flanders K. C., Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Ward J. M., Karlsson S. Transforming growth factor β 1 null mutation in mice causes excessive inflammatory response and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:770–774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R., Jarrett J. A., Chen E. Y., Eaton D. H., Bell J. R., Assoian R. K., Roberts A. B., Sporn M. B., Goeddel D. V. Human transforming growth factor-β complementary DNA sequence and expression in normal and transformed cells. Nature. 1985;316:701–705. doi: 10.1038/316701a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R., Goeddel D. V., Ullrich A., Gutterman J. U., Williams R. D., Bringman T. S., Berger W. H. Synthesis of messenger RNAs for transforming growth factors α and β and the epidermal growth factor receptor by human tumors. Cancer Res. 1987;47:707–712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R., Rhee L. Sequence of the porcine transforming growth factor-β precursor. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3187. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.7.3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derynck R., Rhee L., Chen E. Y., Van Tilburg A. Intron-exon structure of the human transforming growth factor-β precursor gene. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3188–3189. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.7.3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharples K., Plowman G. D., Rose T. M., Twardzik D. R., Purchio A. F. Cloning and sequence analysis of simian transforming growth factor-β cDNA. DNA. 1987;6:239–244. doi: 10.1089/dna.1987.6.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois C. M., Laprise M. H., Blanchette F., Gentry L. E., Leduc R. Processing of transforming growth factor β 1 precursor by human furin convertase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10618–10624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield L. M., Smith D. M., Flanders K. C., Sporn M. B. Latent transforming growth factor-β from human platelets A high molecular weight complex containing precursor sequences. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7646–7654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazono K., Olofsson A., Colosetti P., Heldin C. H. A role of the latent TGF-β 1-binding protein in the assembly and secretion of TGF-β 1. EMBO J. 1991;10:1091–1101. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb08049.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rifkin D. B. Latent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) binding proteins: orchestrators of TGF-β availability. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:7409–7412. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R400029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taipale J., Miyazono K., Heldin C. H., Keski-Oja J. Latent transforming growth factor-β 1 associates to fibroblast extracellular matrix via latent TGF-β binding protein. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:171–181. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laiho M., Weis M. B., Massague J. Concomitant loss of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β receptor types I and II in TGF-β-resistant cell mutants implicates both receptor types in signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18518–18524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. Y., Wang X. F. Expression cloning of TGF-β receptors. Mol Reprod Dev. 1992;32:105–110. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080320205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. Y., Wang X. F., Ng-Eaton E., Weinberg R. A., Lodish H. F. Expression cloning of the TGF-β type II receptor, a functional transmembrane serine/threonine kinase. Cell. 1992;68:775–785. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Dijke P., Yamashita H., Ichijo H., Franzen P., Laiho M., Miyazono K., Heldin C. H. Characterization of type I receptors for transforming growth factor-β and activin. Science. 1994;264:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.8140412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita H., Ichijo H., Grimsby S., Moren A., ten Dijke P., Miyazono K. Endoglin forms a heteromeric complex with the signaling receptors for transforming growth factor-β. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1995–2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massague J. A very private TGF-β receptor embrace. Mol Cell. 2008;29:149–150. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Massagué J. Mechanisms of TGF-β signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretzschmar M., Liu F., Hata A., Doody J., Massague J. The TGF-β family mediator Smad1 is phosphorylated directly and activated functionally by the BMP receptor kinase. Genes Dev. 1997;11:984–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.8.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macias-Silva M., Abdollah S., Hoodless P. A., Pirone R., Attisano L., Wrana J. L. MADR2 is a substrate of the TGFβ receptor and its phosphorylation is required for nuclear accumulation and signaling. Cell. 1996;87:1215–1224. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence D. A., Pircher R., Kryceve-Martinerie C., Jullien P. Normal embryo fibroblasts release transforming growth factors in a latent form. J Cell Physiol. 1984;121:184–188. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041210123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q., Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-β and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dallas S. L., Rosser J. L., Mundy G. R., Bonewald L. F. Proteolysis of latent transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-binding protein-1 by osteoclasts A cellular mechanism for release of TGF-β from bone matrix. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21352–21360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang M. H., Kuo W. W., Chen R. J., Lu M. C., Tsai F. J., Kuo W. H., Chen L. Y., Wu W. J., Huang C. Y., Chu C. H. IGF-II/mannose 6-phosphate receptor activation induces metalloproteinase-9 matrix activity and increases plasminogen activator expression in H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2008;41:65–74. doi: 10.1677/JME-08-0051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godar S., Horejsi V., Weidle U. H., Binder B. R., Hansmann C., Stockinger H. M6P/IGFII-receptor complexes urokinase receptor and plasminogen for activation of transforming growth factor-β1. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:1004–1013. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199903)29:03<1004::AID-IMMU1004>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakytny R., Ludlow A., Martin G. E., Ireland G., Lund L. R., Ferguson M. W., Brunner G. Latent TGF-β1 activation by platelets. J Cell Physiol. 2004;199:67–76. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Ullrich J. E., Poczatek M. Activation of latent TGF-β by thrombospondin-1: mechanisms and physiology. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2000;11:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(99)00029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger J. S., Harpel J. G., Giancotti F. G., Rifkin D. B. Interactions between growth factors and integrins: latent forms of transforming growth factor-β are ligands for the integrin αvβ1. Mol Biol Cell. 1998;9:2627–2638. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.9.2627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford S. E., Stellmach V., Murphy-Ullrich J. E., Ribeiro S. M., Lawler J., Hynes R. O., Boivin G. P., Bouck N. Thrombospondin-1 is a major activator of TGF-β1 in vivo. Cell. 1998;93:1159–1170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81460-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow A., Yee K. O., Lipman R., Bronson R., Weinreb P., Huang X., Sheppard D., Lawler J. Characterization of integrin β6 and thrombospondin-1 double-null mice. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:421–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00367.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annes J. P., Munger J. S., Rifkin D. B. Making sense of latent TGFβ activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:217–224. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil N. TGF-β: from latent to active. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:1255–1263. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)00259-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glinka Y., Prud'homme G. J. Neuropilin-1 is a receptor for transforming growth factor {β}-1, activates its latent form, and promotes regulatory T cell activity. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;84:302–310. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0208090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z., Mu Z., Dabovic B., Jurukovski V., Yu D., Sung J., Xiong X., Munger J. S. Absence of integrin-mediated TGFβ1 activation in vivo recapitulates the phenotype of TGFβ1-null mice. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:787–793. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200611044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger J. S., Huang X., Kawakatsu H., Griffiths M. J., Dalton S. L., Wu J., Pittet J. F., Kaminski N., Garat C., Matthay M. A., Rifkin D. B., Sheppard D. The integrin α v β 6 binds and activates latent TGF β 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;96:319–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leksa V., Godar S., Schiller H. B., Fuertbauer E., Muhammad A., Slezakova K., Horejsi V., Steinlein P., Weidle U. H., Binder B. R., Stockinger H. TGF-β-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells mediated by M6P/IGFII-R and mini-plasminogen. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4577–4586. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipff P. J., Hinz B. Integrins and the activation of latent transforming growth factor β1—an intimate relationship. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:601–615. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong H., Vodovotz Y., Cox G. W., Barcellos-Hoff M. H. Immunocytochemical localization of latent transforming growth factor-β1 activation by stimulated macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 1999;178:275–283. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199903)178:3<275::AID-JCP1>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Tsuboi R., Lyons R., Moses H., Rifkin D. B. Characterization of the activation of latent TGF-β by co-cultures of endothelial cells and pericytes or smooth muscle cells: a self-regulating system. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:757–763. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.2.757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y., Okada F., Abe M., Seguchi T., Kuwano M., Sato S., Furuya A., Hanai N., Tamaoki T. The mechanism for the activation of latent TGF-β during co-culture of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells: cell-type specific targeting of latent TGF-β to smooth muscle cells. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1249–1254. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oida T., Xu L., Weiner H. L., Kitani A., Strober W. TGF-β-mediated suppression by CD4+CD25+ T cells is facilitated by CTLA-4 signaling. J Immunol. 2006;177:2331–2339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Kitani A., Fuss I., Pedersen A., Harada N., Nawata H., Strober W. TGF-β 1 plays an important role in the mechanism of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell activity in both humans and mice. J Immunol. 2004;172:834–842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. L., Yan B. S., Bando Y., Kuchroo V. K., Weiner H. L. Latency-associated peptide identifies a novel CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell subset with TGFβ-mediated function and enhanced suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol. 2008;180:7327–7337. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali N. A., Gaughan A. A., Orosz C. G., Baran C. P., McMaken S., Wang Y., Eubank T. D., Hunter M., Lichtenberger F. J., Flavahan N. A., Lawler J., Marsh C. B. Latency associated peptide has in vitro and in vivo immune effects independent of TGF-β1. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1914. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler J., Sunday M., Thibert V., Duquette M., George E. L., Rayburn H., Hynes R. O. Thrombospondin-1 is required for normal murine pulmonary homeostasis and its absence causes pneumonia. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:982–992. doi: 10.1172/JCI1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X. Z., Wu J. F., Cass D., Erle D. J., Corry D., Young S. G., Farese R. V., Jr, Sheppard D. Inactivation of the integrin β 6 subunit gene reveals a role of epithelial integrins in regulating inflammation in the lung and skin. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:921–928. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.4.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimbert P., Bouguermouh S., Baba N., Nakajima T., Allakhverdi Z., Braun D., Saito H., Rubio M., Delespesse G., Sarfati M. Thrombospondin/CD47 interaction: a pathway to generate regulatory T cells from human CD4+ CD25– T cells in response to inflammation. J Immunol. 2006;177:3534–3541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Dignam J. D., Gentry L. E. Role of carbohydrate structures in the binding of β1-latency-associated peptide to ligands. Biochemistry. 1997;36:11923–11932. doi: 10.1021/bi9710479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travis M. A., Reizis B., Melton A. C., Masteller E., Tang Q., Proctor J. M., Wang Y., Bernstein X., Huang X., Reichardt L. F., Bluestone J. A., Sheppard D. Loss of integrin α(v)β8 on dendritic cells causes autoimmunity and colitis in mice. Nature. 2007;449:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nature06110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bommireddy R., Doetschman T. TGFβ1 and T(reg) cells: alliance for tolerance. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:492–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann J., Huehn J., de la Rosa M., Maszyna F., Kretschmer U., Krenn V., Brunner M., Scheffold A., Hamann A. Expression of the integrin α Eβ 7 identifies unique subsets of CD25+ as well as CD25– regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13031–13036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192162899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleizes P. E., Munger J. S., Nunes I., Harpel J. G., Mazzieri R., Noguera I., Rifkin D. B. TGF-β latency: biological significance and mechanisms of activation. Stem Cells. 1997;15:190–197. doi: 10.1002/stem.150190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]