Abstract

Three experiments were designed to examine temporal envelope processing by cochlear implant (CI) listeners. In experiment 1, the hypothesis that listeners’ modulation sensitivity would in part determine their ability to discriminate between temporal modulation rates was examined. Temporal modulation transfer functions (TMTFs) obtained in an amplitude modulation detection (AMD) task were compared to threshold functions obtained in an amplitude modulation rate discrimination (AMRD) task. Statistically significant nonlinear correlations were observed between the two measures. In experiment 2, results of loudness-balancing showed small increases in the loudness of modulated over unmodulated stimuli beyond a modulation depth of 16%. Results of experiment 3 indicated small but statistically significant effects of level-roving on the overall gain of the TMTF, but no impact of level-roving on the average shape of the TMTF across subjects. This suggested that level-roving simply increased the task difficulty for most listeners, but did not indicate increased use of intensity cues under more challenging conditions. Data obtained with one subject, however, suggested that the most sensitive listeners may derive some benefit from intensity cues in these tasks. Overall, results indicated that intensity cues did not play an important role in temporal envelope processing by the average CI listener.

INTRODUCTION

As cochlear implants (CIs) convey sparse spectral cues, the processing of temporal cues is of substantial importance in electrical hearing. Speech perception can be subserved relatively well with temporal envelope cues and only a few spectral channels of information (Shannon et al., 1995; Fishman et al., 1997). As the degree of spectral degradation increases, listeners rely more heavily on the envelope cues (e.g., Xu et al., 2005). The lower rates of envelope fluctuation are most important for speech recognition: thus, even with only four broad bands of information, envelope cues above 20 Hz do not appear to play a critical role in phoneme or sentence recognition in quiet (Shannon et al., 1995). When the task involves the processing of voice pitch changes, however, the faster temporal fluctuations become more important (Fu et al., 2004, 2005; Green et al., 2004). Significant correlations have been observed between CI listeners’ ability to discriminate between two different amplitude modulation (AM) rates (i.e., temporal envelope rate discrimination) and lexical tone recognition (Luo et al., 2008) as well as fundamental frequency (F0)-based intonation recognition (Chatterjee and Peng, 2008). Thus, it is of considerable importance to understand the mechanisms underlying temporal envelope processing by CI listeners, particularly at envelope rates that span the range of speech envelope and voice pitch fluctuations.

The temporal modulation transfer function has been described in both normal and electric hearing. Viemeister (1979) used a broadband noise carrier to measure the temporal modulation transfer function (TMTF) for amplitude modulation detection (AMD) in acoustic hearing, and found a low-pass filter shaped function that was relatively level-independent. More recently, work on modulation-tuned filters (Dau et al., 1997) suggests that the poorer AM sensitivity observed with noise carriers at high AM rates stems from modulation interference. According to the modulation filterbank model, the intrinsic fluctuations of broadband noise would excite the broader AM filters tuned to high rates more than the narrower low-rate AM filters, which would in turn result in greater modulation interference at high AM rates. As TMTFs measured in electric hearing are typically obtained using pulse train carriers which do not have the inherent fluctuations of noise, acoustic TMTFs obtained using tonal carriers are likely to be more comparable to electric TMTFs. Excluding issues involving spectral sideband detection which arise when tonal carriers are used, the TMTF shape obtained with such carriers in NH listeners also has a low-pass filter shape, and, unlike the TMTF obtained with broadband noise, shows strong level-dependence (Kohlrausch et al., 2000). Similar to this pattern, the TMTF obtained in CI listeners typically shows a low-pass filter characteristic (Shannon, 1992) and is level-dependent in both shape and sensitivity. At lower carrier levels, the low-pass filter cutoff tends to be lower for electrical hearing than at higher levels, and sensitivity is poorer than at higher levels (Shannon, 1992; Chatterjee and Robert, 2001; Fu, 2002).

Thresholds for amplitude modulation rate discrimination (AMRD) in electrical hearing were measured by Chatterjee and Peng (2008) at a fixed 20% modulation depth and a comfortably loud fixed carrier level of 50% of the dynamic range (DR, measured as the difference in microamperes between the loudest acceptable level and threshold). At that level, the function had a steep roll-off at high AM rates (>200 Hz). At low AM rates, there was also a worsening of performance, perhaps owing to limited stimulus duration [i.e., not as many cycles of AM at low rates as at high rates within the 300 ms duration: see Luo et al. (2010)]. This worsening of performance at low rates generally is not observed in AMD tasks.

It appears reasonable to speculate that AMRD thresholds should depend on the salience of the AM, and therefore, on AMD thresholds. AMRD is measured at a fixed AM depth. If AMD thresholds are higher at a particular AM rate, the perceptual salience of the modulation is likely to be weaker. If the perceptual salience is weaker, AMRD thresholds in turn are likely to be higher. Assuming that the strength of the cue increases with the depth of the modulation, listeners’ performance should improve with increases in the AM depth. Chatterjee and Peng (2008) observed a relationship between the two measures in their study; however, the dataset was not extensive enough to allow statistical analysis of the correlation. The goal of experiment 1 of the present study was to compare TMTFs in AMD and AMRD in CI listeners, and to explore the effects of increasing AM depth on listeners’ performance in AMRD.

As previous studies have shown some dependence of AMD on electrode location (Pfingst et al., 2008), the measurements in the present study were made at three locations in the apical half of the electrode array. Middlebrooks and Snyder (2010) have suggested that the apical-most neurons in the cochlea may encode temporal cues more strongly than basal neurons. They concluded that access to these apical neurons was not possible with present-day intrascalar CIs; therefore, enhanced temporal coding at apical-most cochlear regions could not be observed with these implants. It is, however, still possible that apical fibers of passage are stimulated by the apical-most electrodes in intracochlear implants in humans. In fact, research on pitch-matching between acoustic and electric hearing suggests that the apical electrodes of the intracochlear electrode are matched to lower pitches than would be predicted based on tonotopic locations (e.g., Boex et al., 2006; Dorman et al., 2007). Thus, it is possible that the apical-most specialized temporal coding neurons proposed by Middlebrooks and Snyder can indeed be excited by apical stimulation of intracochlear electrodes. In humans, Chatterjee and Peng (2008) measured the place-dependence of AMRD in three subjects and observed strong place-dependence in two of the three, with poorer performance in the more basal electrodes than the apical electrodes. This issue is explored further in the present study, in the context of Middlebrooks and Snyder’s recent findings in the cat. In the present study, electrodes 18, 14, and 10 in our subjects with Nucleus CIs (apical, middle and basal electrodes in the apical half of the array) were selected for testing. This section of the electrode array would receive the bulk of speech energy in CIs, corresponding to a range of frequencies from about 500–2500 Hz.

One factor that has not been sufficiently considered in studies of AM coding in electrical hearing, is the contribution of loudness cues to listeners’ performance. The root mean square (rms) level of an AM signal increases slightly with increasing AM depth (m). In NH listeners, the increase in rms level also results in a change in loudness (Moore et al., 1999). Viemeister (1979) showed that in NH, AM detection thresholds increased slightly when the changing rms cue was compensated for, but this was only evident at very high AM rates where AM sensitivity is generally poorer. In electrical stimulation, the change in the rms level accompanying AM near AMD threshold is mostly very small, often smaller than the amplitude resolution of the CI. At low carrier levels and at high AM rates, however, AMD thresholds are higher, and it is still a possibility that larger rms level changes accompanying the larger AM depths provide an alternate cue to AM at these levels. In this context, it is important to keep in mind that the peak amplitudes of the AM signal have been also shown to contribute to loudness in electric hearing. Zeng and Zhang (1997) showed that at low levels, the rms level of the electrical signal dominates the loudness percept, but that at higher levels, the AM peak amplitudes dominate the loudness.

In a recent paper, McKay and Henshall (2010) suggested that loudness cues may in fact play an important role in AMD, and questioned the results of several previous AMD studies in CI listeners in which loudness cues were not controlled. In their published experiments, McKay and Henshall conducted loudness-balancing between modulated and unmodulated stimuli and found an increase in loudness resulting from AM: however, there currently is no direct empirical evidence showing the effect of these loudness increases on AM coding. The AM rates used by McKay and Henshall were high (500 and 250 Hz): it is uncertain how results obtained at such high rates would pertain to results obtained at the lower envelope rates that are more relevant to speech. McKay and Henshall stated that they selected the high AM rates because the resulting loudness percept is steady, whereas at lower AM rates, the “instantaneous loudness” would fluctuate. Although the authors described unpublished data at lower AM rates, published data on the impact of intensity cues on AM coding at lower AM rates that are more relevant to speech perception, are lacking. For the 250 Hz AM rate, McKay and Henshall used a low carrier rate of 500 Hz. This would result in a single peak and a single valley for each AM cycle at best, resulting in much poorer sampling than that used by Chatterjee and colleagues in previous studies and in the present study. Overall, McKay and Henshall’s conclusions were based on their loudness model and a limited dataset. Thus, a more complete experimental examination of the role of loudness in AM processing is warranted.

To this end, experiment 2 of the present study examined the loudness of AM stimuli of different rates and modulation depths. The AM rates spanned the range that would be relevant to speech perception (20–300 Hz) by CI listeners. To shed further light upon the issue, experiment 3 of the present study examined the effects of different amounts of level-roving on both AMD and AMRD thresholds. Donaldson and Viemeister (2002) found that large amounts of roving (up to 5.5 dB) reduced the sensitivity of the TMTF for AMD at high AM rates (200 and 400 Hz); overall, the variability in listeners’ performance increased considerably with level-roving.

In AMRD, the listener must discriminate between signals with the same carrier but different modulation rates, given a constant AM depth. The rms and peak amplitudes are identical in the AM signals to be distinguished, but it is possible that the perceived loudness of the higher-rate AM signal is greater because the number of peaks is greater; as discussed previously, there is some evidence that the peak amplitudes can dominate the loudness of AM signals, especially at moderate and high carrier levels (Zeng and Zhang, 1997 ). Chatterjee and Peng (2008) observed that a rove of ±0.5 dB did not influence thresholds in an AMRD task significantly. However, the impact of larger level-roves on AMRD tasks is not known. It is possible that larger level roves are required to eliminate the effect of the loudness cue from the task.

Viemeister’s finding that listeners use the rms amplitude increase to detect AM at high rates, but not at low rates, suggests that when the task becomes difficult, listeners may attend to overall intensity changes rather than the temporal fluctuations in the signal. The same is likely to be true in electrical stimulation: when the task becomes more difficult (at high AM rates or at lower carrier levels), uncompensated intensity cues may have greater influence on AM thresholds. It was thus expected that roving the level of the carrier would result in greater effects (1) at higher AM rates rather than lower AM rates (2) at lower carrier levels rather than at higher carrier levels and (3) in the subjects who had the poorest AMD or AMRD thresholds.

METHODS

Subjects

Ten adult users of the N-24 and Freedom devices (Cochlear Corporation, Inglewood, CO) participated in these experiments. Table TABLE I. lists relevant information about the participants. The subjects’ duration of implant use prior to participating in these experiments ranged from 1 to 10 years (mean = 5.2 yr).

Table 1.

Potentially relevant information about the CI subjects. Vowel identification tests were performed using speech tokens from the Hillenbrand et al. (1995) vowel set (12 vowels, 5 male and 5 female talkers) and consonant identification tests were performed using tokens recorded by Shannon et al. (1999) (20 consonants, 5 male and 5 female speakers). Identification tests were controlled by means of software made available by Dr. Qian-Jie Fu (TigerSpeech Technology, House Ear Institute). Speech tokens were presented via single loudspeaker in a sound-treated booth at 65 dB SPL.

| Subject | Onset of Deafness | Device | Stimulation Mode | Gender | Age at Testing | Vowel Recognition (% correct) | Consonant Recognition (% correct) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | Postlingual | N24 | MP1+2 | F | 66 | 84.17 | 85.5 |

| S2 | Postlingual | N24 | MP1+2 | M | 63 | 45.83 | 68 |

| S3 | Postlingual | Freedom | MP1 | F | 71 | 40 | 59 |

| S4 | Postlingual | Freedom | MP1 | F | 64 | 67.5 | 84 |

| S5 | Postlingual | Freedom | MP1 | F | 68 | 57.5 | 76.5 |

| S6 | Prelingual | N24 | MP1+2 | F | 57 | 25.83 | 36.5 |

| S7 | Postlingual | Freedom | MP1 | F | 64 | 58.33 | 69 |

| S8 | Postlingual | N24 | MP1+2 | M | 21 | 61.67 | 85 |

| S9 | Prelingual | N24 | MP1+2 | M | 26 | 35.83 | 37.5 |

| S10 | Postlingual | N24 | MP1+2 | M | 49 | 69.17 | 72 |

Stimuli

Electrical stimuli were presented via the House Ear Institute Nucleus Research Interface (Robert, 2002). Stimuli were 300 ms trains of biphasic, charge-balanced, rectangular current pulses (40 μs∕phase, 8 μs inter-phase gap) presented at a carrier rate of 2000 pulses∕s. This relatively fast stimulation rate was selected to allow sufficient resolution to carry information at high AM rates (up to 300 Hz). All stimuli were presented to a single electrode at a time, in monopolar (MP1 or MP1 + 2, see Table TABLE I.) stimulation mode. The electrode arrays in the devices under study comprise 22 intracochlear electrodes, numbered 1–22 from base to apex. The electrodes selected for these experiments were located in the apical to mid portion of the array, which receives most of the speech stimulation delivered by the device [electrode numbers (els.) 18, 14, and 10]. The reference carrier level was either 50% of the dynamic range (DR) (experiment 1) or 25% and 50% of the DR (experiments 2 and 3): see Sec. 2C below for how DR was determined. The current amplitudes in μA were obtained by using appropriate equations to convert from clinical units to μA. Sinusoidal amplitude modulation was applied to the current amplitude of the pulses such that the amplitude y of the nth pulse was given by y=A{1+mcos[2πfm(n∕2000)+π]}, where A, fm, and m represent the reference carrier amplitude (μA), the modulation rate (Hz), and the modulation depth, respectively (0.0<m<1.0; throughout this paper, m is referred to either as a percentage or in dB units). AM rates in the present experiments spanned the voice pitch range (Rosen, 1992) and included 20, 50, 75, 100, 150, 200, and 300 Hz. Modulation depths varied across experiments (described below).

Procedures

Dynamic range measures

First, the “Maximum Acceptable Level” (MAL) was determined for each (unmodulated) stimulus using standard methods in our laboratory. Subjects were presented with a low initial signal level and instructed to adjust the current amplitude (by pressing “up” and “down” arrows on the keyboard) until the loudness reached a maximally tolerable level. At least two repetitions were completed for each signal, and the mean MAL (in μA) of all runs was taken as the final MAL for that stimulus. Next, threshold was obtained using a 2-down, 1-up, 2-interval forced-choice adaptive procedure (minimum of 8 reversals, step size halved after 4 reversals, first 4 reversal points discarded in computing the mean of the adaptive run, correct∕incorrect feedback provided), yielding the 70.7% correct point on the psychometric function (Levitt, 1971). Again, the mean of at least two runs was computed to yield the final threshold. Finally, the dynamic range was calculated as the difference in microamperes between the MAL and the threshold for each stimulus. Stimuli were presented at fixed percentages of the DR (in microamperes).

Amplitude modulation detection (experiments 1 and 3)

Amplitude modulation detection (AMD) thresholds were measured using a 2-down, 1-up, 3-interval, 3 alternative forced choice (3AFC) adaptive procedure (number of reversals, etc., identical to Thresholds, see above). Of the three intervals, two contained the unmodulated carrier; randomly, the third interval contained the modulated carrier, and the listener’s task was to indicate (by using a mouse to click on the appropriate button on the screen) which of the three sounds was different. The AM depth was adaptively varied following the 2-down, 1-up rule. Correct∕incorrect feedback was provided. The reference carrier level was either fixed at 50% DR or 25% DR. For each electrode and condition, the AMD thresholds were measured across AM rates in random order. Again, at least two repetitions were completed for each condition tested, and the mean of all repetitions was computed to obtain the final AMD threshold for each condition. The participants were highly experienced in these tasks and did not require practice runs.

Amplitude modulation rate discrimination (Experiments 1 and 3)

Amplitude modulation rate discrimination (AMRD) thresholds were measured using a 2-down, 1-up, 3-interval, 3AFC adaptive procedure identical to that described above. All three intervals contained modulated signals, presented at the same fixed AM depth (either 20% or higher, depending upon the experiment). Two of the intervals contained signals modulated at the reference rate (e.g., 20, 50, 100 Hz, etc.) and the remaining interval contained the same signal, modulated at a higher rate. The listener’s task was to indicate which of the three sounded different. The carrier was presented at either 50% DR or 25% DR.

Compensation for AM salience in AMRD tasks (experiments 1 and 3)

In some instances, the AM depth in the AMRD task was increased for specific conditions, in an attempt to equalize the perceptual salience of the AM. In experiment 1, the compensation was applied whenever the AMD threshold exceeded 1%. Compensation was applied by linearly increasing the AM depth by adding 20% to AMD threshold (m in percent). Thus, if AMD threshold was a modulation depth of 4%, the compensated AM depth used in the AMRD task was 24%. In experiment 3, the compensation was applied only if the AMD threshold exceeded 5% in a particular condition.

Level-roving (experiment 3)

When level-roving was applied in AMD and AMRD tasks, the level of the carrier in each of the three intervals was not fixed, but rather, randomly roved within a specified range (±1, ±2, or ±3 dB, with reference to the reference carrier level) of amplitudes. The range of amplitudes corresponded to 13, 23 −27, and 35–39 clinical units for the ±1, ±2, and ± 3 dB roves, respectively, for the different subjects. Note that only the carrier level was roved; AM depth was not changed with the rove. Subjects were specifically advised to try to ignore the loudness differences between the stimuli when performing the AMRD task. For the higher current level conditions (i.e., at the 50% DR level), subjects were asked to indicate the loudness of the highest-amplitude roved signal: if it sounded too loud, that condition was not included for that subject. If the level of stimulus pulses in any of the conditions exceeded MAL, the condition also was not included.

Loudness balancing (experiment 2)

A double-staircase, 2-interval, 2AFC adaptive procedure was used for loudness balancing (Jesteadt, 1980; Zeng and Turner, 1991) the stimuli. The reference was always the modulated signal (with different fixed AM rates and depths) with the carrier level either at 50% DR or 25% DR. The comparison signal was unmodulated. At each carrier level, all conditions were presented in randomized order. In each trial, the listener heard the two signals (modulated and unmodulated stimuli presented in random order) and was asked to indicate which sounded louder. The carrier level was adaptively varied in a descending and ascending track. The descending track (2-down, 1-up, converging at the level at which the unmodulated signal was louder 70.7% of the time) and the ascending track (2-up, 1-down, converging at the level at which the unmodulated signal was louder 29.3% of the time) were interleaved. At the end of the run, the thresholds obtained for the descending and ascending tracks were averaged to yield the level of the unmodulated carrier that was loudness-balanced to the modulated reference. At least two repetitions were completed for each condition. The final loudness-balanced level was computed from the mean of all runs.

RESULTS

Experiment 1: Threshold functions in AMD and AMRD

Figure 1 shows the threshold functions obtained in each of the ten participants, for both the AMD and AMRD tasks. The AMD data are plotted in dB [20*log(m), where m corresponds to the modulation index]. The AMRD data were converted to a dB scale [20*log(w), where w corresponds to the Weber fraction] to facilitate comparison with the AMD results. Subject S6’s Weber fraction at 300 Hz was exceedingly small and is not shown in the plot in Fig. 1 to preserve visual clarity (this subject’s results are discussed further in later sections).

Figure 1.

(Color online) Individual threshold functions for the AMD and AMRD tasks in experiment 1. AMD thresholds (in dB [20*log(m)]) and AMRD thresholds (dB [20*log(w)]) are shown as a function of AM rate (Hz). Different symbols correspond to data obtained at the three electrode locations (insets in top left-hand panels). Vertical scales for both AMD and AMRD thresholds span a 40 dB range. The dotted lines in each panel showing the AMD data represent the estimated best measurable AMD thresholds given device limitations.

An important point to note here is that for the more sensitive subjects (e.g., S5), the ability to properly measure the AMD threshold was constrained by the device limit of current step size (clinical unit). The estimated best AMD threshold that can be measured given the device limit is shown in the dotted line for each subject (these are slightly different for the N24 and Freedom devices). Note that precise calibration measurements are not available for each individual subject’s device or electrode; the microampere values used in the present experiments represent the best estimates provided by the manufacturer, and individual subject’s devices may vary slightly. As the Nucleus CI system allows far better precision in the time domain than in amplitude domain, researchers have sometimes preferred to modulate pulse phase duration rather than amplitude in the past (e.g., Shannon, 1992; Chatterjee and Robert, 2001). Modulating pulse phase duration, however, has the disadvantage of limiting the maximum carrier pulse rate.

Overall, the AMD results show the low-pass filter shape typical of TMTFs, with varying high-frequency cutoffs and sensitivities. Two of the subjects (S6 and S8) had nearly flat TMTFs, with very high sensitivity. Only two of the nine subjects (S4 and S5) from whom data were available at three electrode locations had different sensitivities at the different electrode locations. In both instances, sensitivity at the more basal location (electrode 10) was poorer than at the apical locations (electrodes 14 and 18).

The AMRD results show the inverted bowl-shaped characteristic, consistent with results obtained by Chatterjee and Peng (2008). The reduced sensitivity at low AM rates found in many of the listeners was likely due to the limited number of modulation cycles in the stimuli, consistent with findings of Viemeister (1979). Above 100 Hz, sensitivity falls off with increasing AM rate in most listeners as expected. Across subjects, the AMRD data did not show much dependence of the AMRD threshold function on electrode location.

One subject (S6) produced noteworthy results as they were not typical of the rest of the listeners in this study. Above 75 Hz, subject S6’s sensitivity to AM rate differences tended to improve with increasing rate, reaching very small Weber fractions at 300 Hz. At high AM rates, the sampling of the waveform by the 2000 pps carrier worsens; it is possible that some degree of sub-sampled, slowly fluctuating temporal cues were available to very sensitive∕attentive listeners, such as subject S6. To investigate this possibility, the AMRD thresholds were also measured in subject S6 using a 4000 pps carrier rate (50% DR) on electrode 10. These data are shown in Fig. 2, and they demonstrated the expected low-pass filter shape. This suggests that sub-sampling at the lower 2000 pps carrier rate may indeed have contributed to subjects S6’s sensitive thresholds at the higher AM rates. Another possible explanation is the poorer AM sensitivity associated with high carrier rates (Galvin and Fu, 2005; Pfingst et al., 2007); however, if this was the case then S6’s AMRD thresholds should have been poorer at all AM rates, rather than just the high rates.

Figure 2.

(Color online) Subject S6’s AMRD thresholds (dB [20*log(w)]) as function of AM rate (Hz) for the standard carrier pulse rate (2000 pps) and a higher carrier pulse rate (4000 pps) on electrode 10.

The relationship between the AMD and AMRD thresholds was first examined within subjects. For each listener, all available data were pooled across electrode locations. First, the overall correlation between the AMD and AMRD thresholds in these pooled data was analyzed. Results (Table TABLE II.) showed a statistically significant positive correlation in only four of the ten listeners. Subject S6’s data showed a negative correlation (not statistically significant). Recall that subject S6’s results were different from the rest: this subject’s AMRD thresholds improved with increasing AM rate, while her AMD thresholds worsened slightly at the highest AM rate (Fig. 1), thus accounting for the negative correlation.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients (r) and significance levels (p) between AMD and AMRD thresholds obtained in each subject, when data obtained at all AM rates were considered (left-hand columns) and when data obtained at the low rates (20 and 50 Hz) were not considered in the analysis (right-hand columns). Asterisks indicate significance at the 0.05 level or better.

| All rates | 75–300 Hz | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject | r | p | r | p |

| S1 | 0.5835 | 0.0055** | 0.8868 | <0.0001**** |

| S2 | 0.7015 | 0.0004*** | 0.8082 | 0.0003*** |

| S3 | 0.6952 | 0.0007*** | 0.9441 | <0.0001**** |

| S4 | 0.3243 | 0.1515 | 0.9303 | <0.0001**** |

| S5 | 0.2069 | 0.3682 | 0.6269 | 0.0124* |

| S6 | −0.4910 | 0.0238 | −0.5414 | 0.0371 |

| S7 | 0.1305 | 0.5944 | 0.6685 | 0.0125* |

| S8 | 0.0905 | 0.6965 | 0.0331 | 0.9067 |

| S9 | 0.6791 | 0.0007*** | 0.7981 | 0.0004*** |

| S10 | 0.6811 | 0.0921 | 0.8596 | 0.0618 |

*=p<0.05.

**=p<0.01.

***=p<0.001.

****=p<0.0001.

Next, the data obtained at the low rates (20 and 50 Hz) were eliminated from the analysis, as it was hypothesized that the limited number of cycles in the observation interval (i.e., the duration effect alluded to earlier), and not the salience of the AM, was the reason for the overall higher AMRD thresholds at these lower AM rates. If this is indeed the case, then inclusion of the low-rate data was expected to have weakened the observed correlation; recall that the relationship between the two measures is expected based on the salience of the AM and not on other factors such as signal duration. This manipulation improved the strength of the correlations considerably: seven of the ten participants now showed a significant relationship between AMD and AMRD (Table TABLE II.). The correlations obtained with the remaining three subjects showed inconsistent effects: in S8, it was weakened, in S10, it was strengthened, and in S6, the negative correlation strengthened. In subject S10, the number of data points was one-third that of the other subjects, possibly accounting for the lack of statistical significance. The strength of the correlation in this subject improved considerably, nearly reaching significance, after the two lower AM rates were removed from consideration.

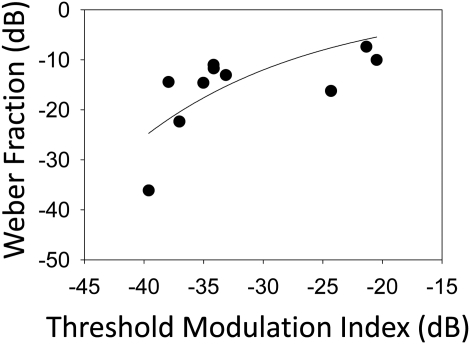

The relationship between the two measures was also examined across subjects. For each AM rate, an overall average threshold was computed for each subject, across electrode locations, for both AMD and AMRD data. A statistically significant nonlinear relation [Fig. 3, two-parameter exponential rise following the equation y = a(1−e−bx)] was observed between these two measures (r = 0.6469, p = 0.0432): linear regression did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.07). Nonlinear regression was selected based on the compressive shape of the function as observed in the data; the specific equation was chosen assuming that the data would asymptote at a particular level (a). AMRD thresholds presented so far were measured using a single, fixed AM depth of 20%. As listeners had different AMD thresholds at different AM rates, it is possible that the depth of 20% was not equally or sufficiently salient across all rates in the AMRD task. Therefore, the effects of AM salience were examined further by increasing AM depth in such a way as to create equal AM depth re: AMD threshold (e.g., if m at detection threshold was 10% for a listener at a particular rate, AM depth at that rate was increased to 30%). The hypothesis was that AMRD sensitivity would increase with increasing salience.

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of mean AMD and AMRD thresholds obtained in experiment 1 showing a non-linear relationship (solid line and equation indicates best-fitting function). AMD and AMRD thresholds were averaged across electrodes and all AM rates for each subject.

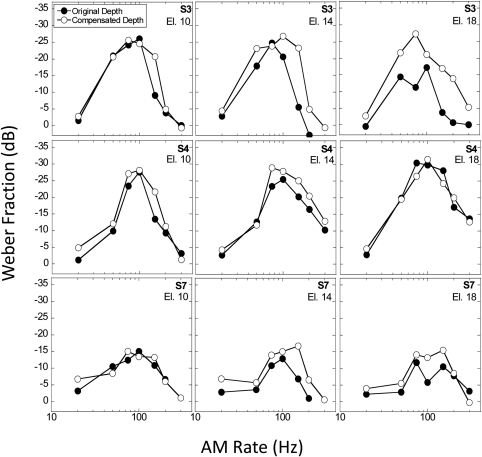

Results were obtained in listeners whose AMD thresholds were the poorest, i.e., exceeded an average of 5% depth (i.e., m corresponding to 0.05 or −26 dB). These were subjects S3, S4, and S7. Referring to Fig. 1, these three subjects also had AMD thresholds exceeding 20% AM depth (−13.98 dB) at the highest AM rates. Figure 4 shows the AMRD thresholds obtained in these subjects with and without AM depth compensation. The change from the original (20% depth) to compensated AM depths generally resulted in similar or improved AMRD thresholds. However, the compensation for AM salience had variable effects across subjects, and for a given subject, variable effects across electrodes. On some, but not all, electrodes, the relation between AMRD thresholds and AM depth was nonmonotonic. If AMRD performance was directly related to AM depth or salience, a consistent relationship should be evident in these plots. No such consistent pattern was observed.

Figure 4.

(Color online) AMRD threshold functions for subjects S3, S4, and S7 obtained at the “original” fixed AM depth of 20% and at a “compensated” AM depth (20% + AMD threshold) at three electrode locations (els. 10, 14, and 18, shown in left, middle and right panels, respectively).

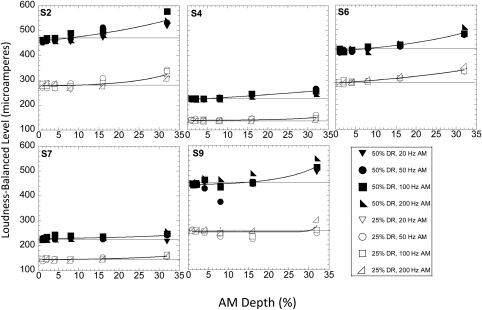

Experiment 2: The loudness of AM stimuli

Loudness-balanced levels were obtained for the 50% DR and 25% DR AM stimuli at six different AM depths and at four AM rates (20, 50, 100, and 200 Hz). The AM depths were 1%, 2%, 4%, 8%, 16%, and 32%, chosen to span the range of AMD thresholds of the CI listeners. Owing to limits on subjects’ availability, measurements were made at electrode 10 only. Figure 5 shows these loudness-balanced levels for the five CI listeners who participated in this experiment. Within each panel, the filled symbols show the results obtained at the 50% DR level, and the open symbols show results obtained at the 25% DR level. The solid horizontal lines in each panel show the levels of the unmodulated carrier at 50% and 25% DR. If the loudness levels of all the AM stimuli were equal to that of the unmodulated carrier, all data points would fall on these lines. The different symbols in each panel correspond to data obtained at different AM rates. It is evident that changing the AM rate from 50 to 200 Hz did not influence the shape of the functions appreciably. Therefore, the data obtained at the different rates were pooled for further analyses. It is apparent that (1) the change in AM depth from 1 to 32% did not cause large changes in loudness; (2) the functions obtained at the 50% and 25% levels were fairly similar and paralleled each other; (3) the loudness remained fairly constant up to an AM depth of about 16%, beyond which there was a small but appreciable increase in loudness. The data were fit by an exponential function of the form:

| (1) |

where y corresponds to the loudness-balanced level, y0 corresponds to the initial loudness-balanced level (and approximates the reference level, shown by the horizontal lines in each plot), m corresponds to the AM depth (in percent), and a and b are constants governing the slope of the increase. The data were well fit by this function (dotted lines in the figures), with one exception: the fit for subject S7’s data at the 50% DR level approached but did not reach significance (r = 0.4828, p = 0.0616). In the remaining cases, r values ranged from 0.5661 to 0.9561, and p ranged from <0.0001 (7 out of 10 cases) to 0.0173. Although the most sensitive listeners had AMD thresholds as low as 1% depth, some listeners (e.g., S4 and S7) did have AMD thresholds close to 32% depth at high AM rates. These listeners may have relied on loudness cues in AM processing tasks at the highest rates.

Figure 5.

(Color online) Individual subjects’ loudness-balanced levels (μA) for AM stimuli at six AM depths (1%, 2%, 4%, 8%, 16%, and 32%) and four AM rates (20, 50, 100, and 200 Hz) obtained in experiment 2. The ordinate shows the level of the unmodulated pulse train that matches the loudness of the pulse train modulated at the specific depth and rate. Filled and open symbols show results obtained with the two carrier reference levels (25% and 50% DR), respectively. The solid horizontal line in each case shows the unmodulated carrier level (μA).

To compare the increase in loudness with AM depth more directly across the two levels, the data obtained at each level were normalized (each data point was divided by the loudness-balanced level at the smallest AM depth, 1%). The normalized data were subjected to a three-factor, repeated-measures analysis of variance (with AM depth, AM rate and carrier level as the three factors and the normalized loudness-balanced level as the dependent variable). As the loudness did not change appreciably between 1 and 4% AM depth, and also to increase the power of the analysis, data obtained at the 1% and 2% AM depths were not considered in the analyses. Elimination of the 1% AM depth data from the analyses was also necessary as this was the normalization reference, and all normalized data had the same value (1.0) at this depth, resulting in a zero-variance dataset. Results indicated a significant effect of AM depth [F(3, 12) = 39.409, p <0.001], but no significant effects of AM rate or carrier level, and no significant interactions. Post hoc pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni correction) showed significant differences between the loudness at the 32% AM depth and all other depths (p <0.02). The loudness at the 16% AM depth was significantly different from that of the 8% depth (p = 0.045), but not from that at the 4% depth. No other significant differences were observed.

Figure 6 shows the normalized data for each subject, averaged across AM rates. The lower right-hand panel shows the mean data across subjects. As carrier level did not influence the shape of the functions, a single exponential function of the form of Eq. 1 was used to fit the pooled data in this panel, and found to approximate the data very well (r = 0.965, p <0.0001):

| (2) |

This equation yields an average increase of 3.39% (0.33 dB, corresponding to 1.88 clinical units for the N-24 device and 2.10 clinical units for the Freedom device) of the modulated over the unmodulated signal level when the AM depth is 20%, regardless of carrier level. At 32% depth, the increase is 13.48% (1.098 dB, corresponding to 6.24 clinical units for the N-24 device and 6.99 clinical units for the Freedom device). It is unclear whether these increases in loudness would influence the strength of the cue in the AMRD task in CI listeners, but the increased loudness may aid less sensitive listeners in the AMD task. This was explored further in experiment 3.

Figure 6.

(Color online) Normalized loudness-balanced levels (re. 1% depth, shown by the solid horizontal line in each panel) plotted as a function of AM depth for individual subjects at the two carrier reference levels (25% and 50%DR) in experiment 2. The left-hand ordinate is expressed in linear units while the right-hand ordinate displays dB values corresponding to those linear units. The lower right-hand panel shows the mean normalized loudness-balanced levels across subjects. Error bars in all panels show ±1 s.d. from the mean. For individual subjects, s.d. was computed across AM rates. For the averaged normalized data shown in the lower right-hand panel, the s.d. reflects variation across subjects.

Experiment 3: Effects of level-roving on TMTFs

Figure 7 shows the effects of level-roving on the AMD thresholds in the five subjects who participated in this experiment. Data were collected at both soft (25% DR) and comfortable (50% DR) listening levels. Fairly large roves (±1, ±2, and ±3 dB) were applied to eliminate the impact of any residual loudness cues. The larger roves (±2 and ±3 dB) constituted a significant portion of the limited electrical DR, likely creating some distraction and perhaps making the task more difficult for reasons unrelated to the use of intensity cues. The effects of level-roving appear to be small in most subjects. In contrast, subject S6’s performance was strongly impacted by even moderate roving under the most challenging conditions (i.e., at the lower level and at the higher AM rates). This suggests that S6 was using intensity cues in these conditions.

Figure 7.

(Color online) Effects of level-roving on AMD TMTFs for the 5 subjects who participated in experiment 3. Each plot shows AMD thresholds as a function of AM rate under different level-roving conditions (No Rove, ±1, ±2, and ±3 dB). The left-hand panel displays the results of roving at a 25% DR reference carrier level, and the right-hand panel for a 50% DR reference carrier level. The lower panels show the mean AMD TMTFs across subjects, with error bars reflecting ±1 s.d. from the mean.

A two-factor, repeated-measures analysis of variance was conducted on the results obtained at the 50% DR level, using data collected at 50 and 100 Hz AM rates (data were not available in all subjects at 20 and 200 Hz), with AM rate and degree of rove (No rove, ±1 dB rove, and ±2 dB rove) as the 2 factors. Effects of rate [F(1, 4) = 10.969, p = 0.03] and degree of rove [F(2, 8) = 4.736, p = 0.044] reached significance at the 0.05 level, but post hoc pairwise comparisons did not show significant differences between the levels of rove, likely because of the small sample size. No significant interactions were observed.

Similar analyses were conducted on the results obtained at the 25% DR level. As data were not available with subject S4 at the 200 Hz rate, the analyses were conducted in two ways, one including S4 (and excluding the 200 Hz condition) and the other excluding S4 (but including all the rates). This provided a more complete picture than using only one of the approaches. First, a two-factor, repeated-measures analysis of variance was conducted with three levels of AM rate (20, 50, and 100 Hz) and four degrees of rove (No rove, ±1, ±2, and ±3 dB roves). Results indicated a barely significant interaction between AM rate and rove [F(6, 24) = 2.613, p = 0.043], and significant main effects of rate [F(2, 8) = 12.414, p = 0.004] and degree of rove [F(3, 12) = 4.335, p = 0.027]. Post hoc pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni adjustment) revealed a barely significant difference between the 50 and 100 Hz AM rates (p = 0.049) and no significant differences between degrees of rove. Next, the analyses were repeated excluding subject S4, and including the 200 Hz rate as a fourth level of rate. In this case, the effect of rate was highly significant [F(3, 9) = 31.294, p <0.001], but the effect of rove and the interaction between the two did not reach significance. Taken together, these analyses suggest that the effect of rate is stronger than the effect of rove, and that the interaction between the two is also not strong.

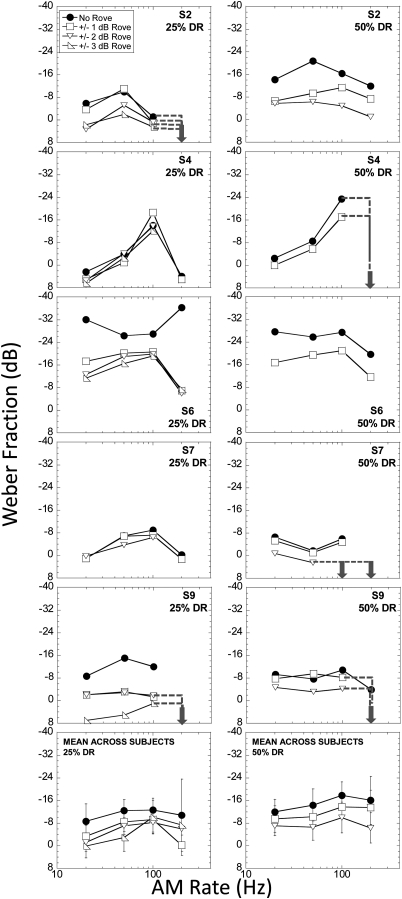

Figure 8 shows the effects of roving on the AMRD thresholds. Note that here, the AM depths were compensated for salience when AMDTs exceeded 5% (−26.02 dB). The dotted lines and arrows indicate conditions in which the task became too difficult and AMRD thresholds could not be obtained. At 50% DR, AMRD thresholds could not be obtained with larger roves in many cases because the loudness exceeded tolerance limits. When the TMTF changes in gain (i.e., the entire function shifts down), it is reasonable to infer that the task became more difficult for some reason. For instance, pitch and loudness cues may have been confused, a very common occurrence in electrical stimulation, or the fluctuations in loudness could have introduced a greater cognitive load. This pattern was observed in most subjects at both carrier levels. However, subject S6’s data showed a different pattern at the lower level, with the greatest decline in performance occurring at the highest AM rate, strongly suggesting that this subject had been using intensity cues at the 25% DR level.

Figure 8.

(Color online) Effects of level-roving on AMRD threshold functions for the 5 subjects who participated in experiment 3. AM depths were compensated for salience when AMD thresholds exceeded m of 5%. Gray dotted lines and arrows indicate conditions in which thresholds were too high to be measurable. Remaining aspects of plots are identical to those in Fig. 8. Other missing data correspond to conditions in which roving led to excessive loudness.

A two-factor, repeated measures analysis of variance was conducted on the 50% DR level data, with AM rate (20, 50, and 100 Hz) and degree of rove (No Rove and ±1 dB rove) as the two factors (not enough data were available at 200 Hz or with the higher levels of rove). Results showed no significant effects of rate or rove, and no significant interactions. A two-factor, repeated measures analysis of variance also was conducted on the results obtained at the 25% DR level, with AM rate (20, 50, and 100 Hz) and degree of rove (No Rove, ±1 and ±2 dB) as factors. Results showed a significant effect of rove [F(2, 8) = 7.97, p = 0.012], but no significant effect of AM rate, and no significant interactions between the two. A post hoc pairwise comparison (Bonferroni adjustment) showed no significant differences between the degrees of rove.

Given the limited number of subjects and data available for analyses, these results should be treated with the utmost caution. Overall, an examination of the mean data in Figs. 78 suggests that the effects of even large roves on the threshold functions in AMD and AMRD were small although sometimes statistically significant. The shapes of the functions were not substantially influenced by level-roving. Importantly, listeners who were least sensitive to AM showed little to no effect of roving, whereas the most sensitive listener (S6) showed the expected negative effect of roving.

DISCUSSION

The weight of information transmitted by CIs resides in the temporal envelopes of the pulse train carriers stimulating multiple regions of the cochlea. The experiments presented here have explored mechanisms involved in CI listeners’ sensitivity to temporal envelopes in some depth.

Effects of AM depth∕salience

In experiment 1, the relationship between performance in the two temporal processing tasks (AMD and AMRD) was examined. It was hypothesized that listeners’ ability to discriminate between two different AM rates would be determined at least in part by the perceptual salience of the AM (as reflected in AMD thresholds). The within-subject analysis showed that, when all AM rates were considered, only four of the ten subjects showed a significant correlation between AMD and AMRD thresholds. However, when only high AM rates were considered, seven of the ten subjects showed a significant correlation between the two. In part, the latter result could be considered somewhat artificial, as the AMD TMTFs and AMRD threshold functions had different shapes at low AM rates, and were more similar in shape at high AM rates. When the mean AMD and AMRD thresholds of all subjects were correlated across AM rates, a significant positive (nonlinear) relationship between the two still emerged, suggesting a true relation between the salience of AM and CI listeners’ ability to discriminate between two AM rates.

The second part of experiment 1 focused on three subjects with poorer AMD thresholds. Compensating the depth of modulation to achieve equal AM salience across AM rates sometimes resulted in improvements in their performance, but contrary to expectations, no clear relationship between the degree of AM salience and AMRD thresholds emerged. Taken together with the correlation analyses above, these results suggest that while AMD thresholds and AMRD thresholds are related, AMD threshold is not the only factor determining performance in AMRD. Factors other than AM salience (such as the strength of the temporal pitch cue, for instance) are likely to dictate listeners’ ability to discriminate between temporal envelopes. Loudness was shown to increase with increasing AM depths above 16% in experiment 2, but the results of experiment 1 suggest that this increase in loudness was not a consistent cue for AMRD. This can be inferred from the observation that when the AM depth of the signal was systematically increased in experiment 1, listeners showed improvements in performance in AMRD, but these improvements did not always increase monotonically with modulation depth. This was the case even though the increase in loudness (although small and only observed at the higher AM depths) was consistent and monotonic with increasing AM depth in experiment 2.

A secondary observation emerging from experiment 1 was that the electrode location did not influence listeners’ temporal coding abilities in a consistent manner. This appears to be consistent with findings of Middlebrooks and Snyder (2010) indicating that stimulation of the intrascalar electrodes did not elicit the high-fidelity temporal coding they observed with apical stimulation.

Loudness∕intensity cues in AMD and AMRD

Experiments 2 and 3 directly examined the impact of loudness∕intensity cues on AMD and AMRD. Experiment 2 clearly showed that increasing AM depth increases the loudness of the modulated signal; however, appreciable increases were only observed at the highest AM depth tested (32%). The carrier level had no influence on the effect of AM depth on loudness, and no effects of AM rate were observed in the results. The exponential nature of the function relating the loudness to the AM depth indicates that, consistent with findings of McKay and Henshall (2010), very deep AM would result in considerably greater perceived loudness. This finding has implications for speech processing strategies in which the temporal envelope cue is enhanced to improve F0 coding.

The role of carrier level may also shed light on the impact of loudness cues. The increase in loudness with increasing AM depth was very similar at the two carrier levels tested. However, listeners’ performance in AMD was strongly level-dependent (shown in results from experiment 3), consistent with findings from previous studies (e.g., Fu, 2002; Galvin and Fu, 2005, 2009; Pfingst et al., 2007; Chatterjee and Robert, 2001; Shannon, 1992). If loudness was a primary cue in AM detection, listeners should show similar sensitivity at the two carrier levels, but they did not. The discrepancy suggests that loudness is not an important contributor to CI listeners’ performance in AMD tasks.

Experiment 3 showed that the effect of level-roving did reach statistical significance in most conditions in both AMD and AMRD; however, the effect was not large enough to reveal significant differences in post hoc comparisons with the limited data set available. The effect of level-roving was more apparent at the lower carrier level (at the 50% DR level, loudness limitations prevented large roves). No interactions were observed between the degree of rove and the AM rate. This lack of interaction strongly suggests that listeners were not using intensity cues to perform the task in the more difficult conditions (i.e., at higher AM rates), consistent with observations in NH listeners by Viemeister (1979). Instead, we speculate that roving the carrier level resulted in increased uncertainty∕difficulty of the task; perhaps the cognitive load of the task was increased.

The listener’s ability to use intensity cues

It may be worthwhile to consider the present results in the light of the hypotheses stated in the Introduction regarding the effects of loudness cues∕roving on performance by listeners with different degrees of AM sensitivity. In most listeners, the overall gain of the TMTF decreased slightly when the rove was introduced. Subject S6, however, proved a strong exception to the rule. She demonstrated great sensitivity in both AMD and AMRD tasks, even with large level-roving. It is possible that she was able to use subsampled temporal cues in the AMRD task (as shown in Fig. 2 when the carrier rate was increased). She was also likely using intensity cues in difficult conditions, as roving resulted in reduced performance at high AM rates.

Contrary to the hypotheses stated in the Introduction, larger effects of roving were not observed in the less sensitive CI listeners. For instance, S4 and S7 were the least sensitive to the AM cue, and yet roving the carrier level had little to no effect on their AMD thresholds (Fig. 7). However, S6, one of the most sensitive, showed a stronger effect of roving at the highest AM rate and the lower carrier level. Thus, it appears that the more sensitive listeners also may be the ones who can use the intensity cues under difficult listening conditions. Perhaps the changes in intensity are not large enough to be usable by the less sensitive listeners. These findings are broadly consistent with the previously cited results of Donaldson and Viemeister (2002), who also observed negative effects of roving at high AM rates on the most sensitive CI listeners.

Green (1988) demonstrated that, for a 2-down, 1-up adaptive procedure tracking the 70.7% correct performance level, threshold intensity increments (in dB units) less than 23.46% of the dB range of the rove, cannot be detected by within-channel intensity∕loudness cues alone. Using this criterion, we calculate a level detection limit [in 20 log(m) units] of −9.54 dB for a ±0.5 dB rove and −1.15 dB for a ±3 dB rove. In this context, the data of Fig. 7 can be considered in two ways. First, if loudness cues were being used for AM detection, listeners’ performance should improve with increasing range of rove: this does not occur. Second, most of the AMD thresholds in Fig. 7 (except for those obtained at the highest AM rates) are better than −9.54 dB, indicating that in most instances, Green’s level detection limit is met. This analysis thus provides additional support for the conclusion that AM-induced loudness cues are not in fact useful for listeners in AM detection tasks.

In the AMRD task, applying large roves at the highest rates made the task practically impossible for some of the participants. It is possible that this was due to changing pitch cues accompanying the large changes in loudness.

Possible roles of instantaneous amplitude changes and overall loudness, and implications for the results of previous studies

It is clear that the perception of AM depends on the listener’s ability to process intensity changes over time. The perceptual correlate of these instantaneous intensity changes that lead to the perception of AM may be identical to the instantaneous perception of loudness changes, or related to precursors of the loudness variable. The instantaneous changes of perceived loudness may be very difficult to measure behaviorally. When a listener is asked to loudness-balance a modulated signal to the unmodulated carrier, we obtain an idea of the overall loudness difference between the two. However, this overall loudness difference may not be the primary cue used by the listener when processing AM: rather, some (possibly related) correlate of the fluctuating instantaneous amplitude is more likely involved in AM coding. When the task of detecting AM becomes difficult (i.e., at high AM rates or at low carrier levels), the more sensitive listeners may resort to using the overall loudness difference as a cue. It is important to keep the distinction between the two in mind when considering AM coding.

The effect of loudness cues may impact a number of findings related to AM coding in electric hearing. For instance, McKay and Henshall (2010) suggested that changes in the instantaneous loudness variable may also explain “stochastic-resonance”-like effects observed in AM detection (Chatterjee and Robert, 2001; Chatterjee and Oba, 2005). An expansive nonlinearity of the sort associated with loudness in electrical hearing (much like the input∕output function of a “threshold device”), may well explain a stochastic resonance phenomenon (Harmer et al., 2002). To date, there is no clear evidence to suggest that loudness cues specifically explain the observed results: any expansive nonlinear function operating on the envelope would serve the purpose.

Some studies of AM processing by CI listeners (e.g., Shannon, 1992; Chatterjee and Robert, 2001; Chatterjee and Oba, 2005; Pfingst et al., 2007) used pulse phase duration modulation instead of pulse amplitude modulation. When considering the impact of possible loudness cues on the results of these previous studies, it may be worthwhile to note that the loudness increase accompanying an increase in pulse phase duration is less than that accompanying the same relative increase in pulse amplitude (Chatterjee et al., 2000). Thus, when pulse phase duration is modulated, the same AM depth would result in even smaller loudness increases than those observed in the present study and by McKay and Henshall (2010).

Chatterjee (2003) and Chatterjee and Oba (2004) reported on modulation detection interference (MDI) effects in electrical stimulation. The interference observed in those studies caused AM depths to increase by large amounts in order to reach AM detection threshold in many CI listeners. It is very possible that listeners could have used the accompanying loudness cues to detect the AM on the signal channel. If level-roving had been used in those studies, the MDI effects would have likely been magnified. Thus, the MDI reported by Chatterjee (2003) and Chatterjee and Oba (2004) was possibly underestimated relative to the true size of the effect.

Other than the work of Chatterjee and colleagues, these results also generally pertain to previous studies of AM detection conducted without level-roving by other investigators (e.g., Shannon, 1992; Fu, 2002; Galvin and Fu, 2005, 2009; Pfingst et al., 2007; Luo et al., 2009). We conclude that level-roving would not have influenced these results appreciably, except perhaps in the case of the most sensitive listeners attending to the highest AM rates.

Implications for CIs

The present set of results is consistent with previous findings (Zeng and Zhang, 1997; McKay and Henshall, 2010) showing that in electric hearing, sounds that fluctuate greatly in time are perceived to be louder than steady-state sounds with the same mean level. CI listeners, however, appear not to rely on these loudness cues in AM processing (at least for the AM rates included in this study), with the exception of perhaps the most sensitive listeners. The results also showed that CI listeners’ ability to detect AM was correlated with their ability to discriminate two distinct AM rates. While deeper modulations of the temporal envelope sometimes resulted in improved temporal AM rate discrimination, the relation between depth of modulation and improvement in performance was not always monotonic. Regardless, more deeply modulated temporal waveforms should be more discriminable by CI listeners. This suggests that speech processing strategies aimed at enhancing the temporal-envelope-based F0 cue should succeed at some level. Whether improved discrimination of two temporal envelopes can be directly translated to improvements in various complex pitch perception tasks is not clear. Chatterjee and Peng (2008) found a nonlinear correlation between CI listeners’ AMRD thresholds and their performance in F0-contour-based speech intonation recognition. Thus, excellent AMRD thresholds were necessary, but not sufficient, for excellent performance in the speech intonation recognition task.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS

-

(1)

Threshold function shapes for AMD and AMRD in CI listeners were consistent with findings by previous investigators. Electrode location did not appear to influence TMTF sensitivity or shape in a consistent manner.

-

(2)

A significant positive nonlinear correlation was observed between performance in AMD and AMRD. Listeners with greater sensitivity to AM also showed greater sensitivity to AM rate differences.

-

(3)

Loudness increased monotonically with increasing AM depth above AM depths of 16%. These increases, however, were small, corresponding to mean increases in level of 0.33 dB (approximately 2 clinical units) and 1.09 dB (6 or 7 clinical units) at 16% and 32% modulation depth, respectively. While the amount of loudness increase with AM depth did not depend upon carrier level, AM sensitivity showed strong level-dependence. This suggests that loudness is not a primary cue for AM detection.

-

(4)

Although the effects of level-roving on AMD and AMRD thresholds were statistically significant in some instances, post hoc comparisons and interactions were not significant. Importantly, level-roving did not change the shape of the TMTF, nor did it influence the results obtained in the least sensitive listeners.

-

(5)

Results obtained with one of the listeners suggest that the more sensitive listeners may be best able to use loudness∕intensity cues, as well as temporal cues resulting from subsampling, in AM processing tasks: however, the average CI listener can derive only limited benefit from the loudness changes that accompany AM.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very grateful to the CI users who participated in this study for their patience and ongoing support of our research. We thank Mark E. Robert for software support. We are very grateful to Bernhard Laback and an anonymous reviewer for their detailed and insightful comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by NIH Grant No. R01-DC-004786 to MC.

References

- Boex, C., Baud, L., Cosendai, G., Sigrist, A., Kos, M. I., and Pelizzone M. (2006). “Acoustic to electric pitch comparisons in cochlear implant subjects with residual hearing,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolayngol. 7(2), 110–124. 10.1007/s10162-005-0027-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, M. (2003). “Modulation masking in cochlear implant listeners: Envelope vs. tonotopic components,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 113(4), 2042–2053. 10.1121/1.1555613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, M., Fu, Q.-J., and Shannon, R. V. (2000). “Effects of phase duration and electrode separation on loudness growth in cochlear implant listeners,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 107(3), 1637–1644. 10.1121/1.428448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, M., and Oba, S. I. (2004). “Across- and within-channel envelope interactions in cochlear implant listeners,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 5(4), 360–375. 10.1007/s10162-004-4050-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, M., and Oba, S. I. (2005). “Noise improves modulation detection by cochlear implant listeners at moderate carrier levels.” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 118(2), 993–1002. 10.1121/1.1929258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, M., and Peng, S. C. (2008). “Processing F0 with cochlear implants: Modulation frequency discrimination and speech intonation recognition,” Hear. Res. 235(1–2), 143–156. 10.1016/j.heares.2007.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, M., and Robert, M. E. (2001). “Noise enhances modulation sensitivity in cochlear implant listeners: Stochastic resonance in a prosthetic sensory system?” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 2(2), 159–171. 10.1007/s101620010079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dau, T., Kollmeier, B., and Kohlrausch, A. (1997). “Modeling auditory processing of amplitude modulation I. Detection and masking with narrow-band carriers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 2892–2905. 10.1121/1.420344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, G. S., and Viemeister, N. F. (2002). “TMTFs in cochlear implant users: The role of loudness cues,” Abstracts 24th ARO Midwinter Meeting (Association for Research in Otolaryngology, Mt. Royal, NJ).

- Dorman, M. F., Spahr, T., Gifford, R., Loiselle, L., McKarns, S., Holden, T., Skinner, M., and Finley, C. (2007). “An electric place-frequency map for a cochlear implant patient with hearing in the nonimplanted ear,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 8(2), 234–240. 10.1007/s10162-007-0071-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, J. J., III, and Fu, Q.-J. (2005). “Effects of stimulation rate, mode and level on modulation detection by cochlear implant users,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 6(3), 269–279. 10.1007/s10162-005-0007-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvin, J. J., III, and Fu, Q.-J. (2009). “Influence of stimulation rate and loudness growth on modulation detection and intensity discrimination in cochlear implant users,” Hearing Res. 250(1–2), 46–64. 10.1016/j.heares.2009.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman, K. E., Shannon, R. V., and Slattery, W. H. (1997). “Speech recognition as a function of the number of electrodes used in the SPEAK cochlear implant speech processor,” J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 40(5), 1201–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.-J. (2002). “Temporal processing and speech recognition by cochlear implant users,” Neuroreport 13(13), 1635–1639. 10.1097/00001756-200209160-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q.-J., Chinchilla, S., and Galvin, J. J., III (2004). “The role of spectral and temporal cues in voice gender discrimination by normal-hearing listeners and cochlear implant users,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol., 5, 253–260. 10.1007/s10162-004-4046-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Q -J., Chinchilla, S., Nogaki, G., and Galvin, J. J., III (2005). “Voice gender identification by cochlear implant users: The role of spectral and temporal resolution,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 118, 1711–1718. 10.1121/1.1985024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green, D. M. (1988). Profile Analysis: Auditory Intensity Discrimination, Oxford Psychology Series No. 13. (Oxford University Press, New York), pp. 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Green, T., Faulkner, A., and Rosen, S. (2004). “Enhancing temporal cues to voice pitch in continuous interleaved sampling cochlear implants,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116, 2298–2310. 10.1121/1.1785611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer, G. P., Davis, B. R., and Abbott, D. (2002). “A review of stochastic resonance: Circuits and measurement,” IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 51(2), 299–309. 10.1109/19.997828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand, J., Getty, L., Clark, M., and Wheeler, K. (1995). “Acoustic characteristics of American English vowels,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 97, 3099–3111. 10.1121/1.411872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesteadt, W. (1980). “An adaptive procedure for subjective judgments,” Percept. Psychophys. 28(1), 85–88. 10.3758/BF03204321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlrausch, A., Fassel, R., and Dau, T. (2000). “The influence of carrier level and frequency on modulation and beat-detection thresholds for sinusoidal carriers,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 108(2), 723–734. 10.1121/1.429605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, H. (1971). “Transformed up-down methods in psychoacoustics,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 49, 467–477. 10.1121/1.1912375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X., Fu, Q.-J., Wei, C. G., and Cao, K. L. (2008). “Speech recognition and temporal amplitude modulation processing by Mandarin-speaking cochlear implant users,” Ear Hear. 29(6), 957–970. 10.1097/AUD.0b013e3181888f61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, X., Galvin, J. J., and Fu, Q.-J. (2010). “Effects of stimulus duration on amplitude modulation processing with cochlear implants,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 127(2), EL23–EL29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay, C. M., and Henshall, K. R. (2010). “Amplitude modulation and loudness in cochlear implantees,” J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 11(1), 101–111. 10.1007/s10162-009-0188-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrooks, J. C., and Snyder, R. L. (2010). “Selective electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve activates a pathway specialized for high temporal acuity,” J. Neurosci. 30(5), 1937–1946. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4949-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore, B. C., Vickers, D. A., Baer, T., and Launer, S. (1999). “Factors affecting the loudness of modulated sounds,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 105(5), 2757–2772. 10.1121/1.426893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfingst, B. E., Burkholder-Juhasz, R. A., Xu, L., and Thompson, C. S. (2008). “Across-site patterns of modulation detection in listeners with cochlear implants,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 123(2), 1054–1062. 10.1121/1.2828051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfingst, B. E., Xu, L., and Thompson, C. S. (2007). “Effects of carrier pulse rate and stimulation site on modulation detection by subjects with cochlear implants,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 121(4), 2236–2246. 10.1121/1.2537501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert, M. E. (2002). House Ear Institute Nucleus Research Interface User’s Guide (House Ear Institute, Los Angeles: ). [Google Scholar]

- Rosen, S. (1992). “Temporal information in speech: acoustic, auditory, and linguistic aspects,” Philos. Trans. Biol. Sci. 336(1278), 367–373. 10.1098/rstb.1992.0070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R. V. (1992). “Temporal modulation transfer functions in patients with cochlear implants,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 91, 2156–2164. 10.1121/1.403807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R. V., Zeng, F. G., Kamath, V., Wygonski, J., and Ekelid, M. (1995). “Speech recognition with primarily temporal cues,” Science 270, 303–304. 10.1126/science.270.5234.303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, R. V., Jensvold, A., Padilla, M., and Robert, M. E. (1999). “Consonant recordings for speech testing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 106(6), L71–L74. 10.1121/1.428150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viemeister, N. F. (1979). “Temporal modulation transfer functions based upon modulation thresholds,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 66, 1364–1380. 10.1121/1.383531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., Thompson, C. S., and Pfingst, B. E. (2005). “Relative contributions of spectral and temporal cues for phoneme recognition,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117(5), 3255–3267. 10.1121/1.1886405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F. G., and Turner, C. W. (1991). “Binaural loudness matches in unilaterally impaired listeners,” Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 43A, 565–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F. G., and Zhang, C. Y. (1997). “Loudness of dynamic stimuli in electric and acoustic hearing,” J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102, 2925–2934. 10.1121/1.420347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]