Abstract

Objectives

Existing studies on the use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) have produced diverse results regarding the types and prevalence of CAM use due, in part, to variations in the measurement of CAM modalities. A questionnaire that can be adapted for use in a variety of populations will improve CAM utilization measurement. The purposes of this article are to (1) articulate the need for such a common questionnaire; (2) describe the process of questionnaire development; (3) present a model questionnaire with core questions; and (4) suggest standard techniques for adapting the questionnaire to different languages and populations.

Methods

An international workshop sponsored by the National Research Center in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFKAM) of the University of Tromsø, Norway, brought CAM researchers and practitioners together to design an international CAM questionnaire (I-CAM-Q). Existing questionnaires were critiqued, and working groups drafted content for a new questionnaire. A smaller working group completed, tested, and revised this self-administered questionnaire.

Results

The questionnaire that was developed contains four sections concerned with visits to health care providers, complementary treatments received from physicians, use of herbal medicine and dietary supplements, and self-help practices. A priori–specified practitioners, therapies, supplements, and practices are included, as well as places for researcher-specified and respondent-specified additions. Core questions are designed to elicit frequency of use, purpose (treatment of acute or chronic conditions, and health maintenance), and satisfaction. A penultimate version underwent pretesting with “think-aloud” techniques to identify problems related to meaning and format. The final questionnaire is presented, with suggestions for testing and translating.

Conclusions

Once validated in English and non-English speaking populations, the I-CAM-Q will provide an opportunity for researchers to gather comparable data in studies conducted in different populations. Such data will increase knowledge about the epidemiology of CAM use and provide the foundation for evidence-based comparisons at an international level.

Introduction

Despite the prominence of Western biomedical practice and its diffusion around the globe in the past century, many of the world's people—including those in North America and Europe—either rely solely on complementary, alternative, or traditional systems of medicine and natural products, or combine them with Western biomedicine. Practices that arise from traditions other than Western biomedicine or are practiced outside the domain of conventional medicine have been classified as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the Western world. CAM use includes the adherence to traditional (e.g., Ayurvedic) or alternative (e.g., homeopathic) medical systems that include specific healers, therapies, and medications, as well as the use of specific individual therapies, self-help practices, or remedies.

Several national surveys provide evidence of the widespread use of CAM.1 In the 2002 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in the United States, 36% of adults reported receiving or using some form of CAM therapy in the previous year; the number rose to 62% if prayer for health was counted as CAM.2 A compilation of several surveys of CAM use in the Scandinavian countries found that 12%–21% of persons surveyed reported CAM use in the past year.3

While a growing literature exists documenting such CAM practices, it is difficult to compare findings across studies and across countries because of differences in the way CAM use is measured. To address the problem of CAM measurement, a workshop was convened in 2006 by the National Research Center in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFKAM), University of Tromsø, Norway, to develop a common questionnaire that could be used across populations and countries. The purpose of this article is to (1) articulate the need for such a common questionnaire; (2) describe the process of questionnaire development; (3) present a model questionnaire, and (4) suggest standard techniques for adapting the questionnaire to different languages and populations.

Background: Need for a Common Instrument

Existing methods for assessing CAM use make comparisons across populations difficult and are probably at the root of many seemingly contradictory findings on prevalence of use. Some of these difficulties arise from sampling: Different studies focus on different types of populations. For example, within studies of persons with arthritis, studies focused on clinic samples find as many as 90% of patients reporting regular use of CAM.4 In contrast, national and regional population-based surveys find rates of CAM use to be considerably lower.5,6

Difficulties in cross-study comparisons arising from sampling differences are compounded by measurement issues. Some studies have presented respondents with a list of therapies or CAM remedies, other studies have used more open-ended questions, and still other studies have used a single closed question on CAM use in general. It is impossible to know if these three approaches elicit equally thorough inventories of use. The list approach may result in an inflated estimate of use as respondents are “cued” by the list, and use measures depend on what is included on the list. For example, surveys of rural older adults with diabetes using lists that include a wide variety of home remedies have found higher CAM use than other surveys that exclude home remedies.7 Lumping CAM remedies or therapies into broad categories (e.g., “Herbs” or “Manipulative Therapies”) may result in lower use estimates than splitting the modalities into multiple discrete items (e.g., “Ginseng” and “Echinacea,” or “Chiropractic” and “Shiatsu”). Open-ended formats or a single closed question, in contrast, may result in underestimating CAM use because of respondents' failure to remember CAM use or because they do not consider their practices to be CAM.

Another difficulty in comparing prevalence rates is that studies differ in their definitions of CAM.8 Some studies include only visits to CAM practitioners,9 while other studies include visits to CAM practitioners and self-medication using CAM practices and remedies, the use of which has been found to be as extensive as visits to CAM practitioners.10

A final aspect of measurement that hinders cross-study comparison is the timeframe for response. Many researchers11,12 ask if a respondent has “ever used” a CAM modality. These studies tend to show high rates of lifetime use. Other studies try to identify “current use.” This is sometimes specified as in the past 12 months7,13 or as during the course of an illness.14

All of these issues regarding sampling and measurement suggest that the use of a common, standard questionnaire will facilitate comparisons between studies. Such a questionnaire will, of necessity, need to include a set of core questions that are relevant across cultures. While this will not replace questionnaires developed for particular reasons by researchers, a standard questionnaire with core questions will provide researchers who are trying to assess CAM use relative to other studies with a place to start.

The Process of Developing an International CAM Questionnaire

A 2-day workshop of 35 participants was held in Sommarøy, Norway, September 13–15, 2006, to develop a standard questionnaire. The workshop was sponsored by the National Research Center in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFKAM) of the University of Tromsø, Norway, and the Norwegian Research Council. Participants were drawn from a range of backgrounds, including researchers with varied kinds of training (anthropology, sociology, nursing, health services, medicine, public health, and pharmacy) and expertise (survey design, questionnaire construction, and cross-cultural research). All workshop participants were required to have had personal research experience in the area resulting in peer-reviewed publication of their work. Some participants also had clinical experience with conventional or alternative/traditional medicine (e.g., homeopathy, acupuncture, herbal medicine, energy healing, or Traditional Chinese Medicine [TCM]) or both (e.g., physicians practicing integrative medicine). Researchers represented the English-speaking countries of the United States, Canada, Great Britain, and Australia, as well as the non-English speaking countries, Norway, Germany, Sweden, and Denmark. Observers from the World Health Organization (WHO) and NAFKAM also attended the workshop.

Prior to the workshop, attendees circulated existing standardized questionnaires used in a variety of studies that resulted in peer-reviewed publication of the studies. These included local indepth studies of specific populations,7,15–19 broader studies of larger populations,20–22 and such national studies as the United States National Health Interview Survey 2002, which contained a module specifically on complementary and alternative medicine use.2 These questionnaires were reviewed by participants for content and structure.

The workshop was structured to include plenary talks designed to highlight the issues necessitating standardized questionnaires for CAM research. The participants were then divided into four working groups representing different aspects of CAM: (1) personal encounters with CAM providers; (2) use of herbal medicine and dietary supplements; (3) other nonencounter methods; and (4) traditional medicine (as defined by the World Health Organization). These working groups met, initially considered the boundaries of their domains of CAM, and then developed questionnaire items to be included on a standard questionnaire. Through a series of meetings of working groups as well as plenary meetings, these questionnaire items were revised over the course of the workshop to achieve uniformity in format and reduce overlaps in the material. At the end of the workshop, a writing group was formed with representatives of the separate working groups. This writing group was assigned to continue to revise the document after the workshop and to draft a manuscript reflecting the purpose and content of the standard questionnaire. The writing group was to do limited pretesting of the questionnaire, but it was recognized that establishing its validity and reliability would be a long-term goal to achieve after the questionnaire was disseminated to other researchers.

In the course of developing the standard questionnaire, goals were set concerning the final questionnaire. The first goal was that the questionnaire be culture-neutral—not oriented to any particular form of medical care, to any country, or to any cultural tradition. This meant that conventional medicine should not be used as a standard and that any particular forms of CAM should not be privileged. The second goal was that it be accessible to both laypersons (the respondents) and personnel administering the questionnaire (researchers or practitioners). To achieve this, the questionnaire was designed to be either self-administered, for literate populations, or interviewer-administered, for low-literacy populations. Sufficient instructions and formatting were to be provided to assist nonresearchers in collecting data from their patient populations.

Several decisions were made about the content and format. Deliberate decisions were made to construct and present a general questionnaire first, which could be followed later by disease-specific questionnaires aimed at CAM use for conditions such as cancer and arthritis. The issue of whether the questionnaire should be a single general closed question, be open-ended, or contain a list of CAM modalities was carefully weighed. While participants recognized that a completely open-ended questionnaire would allow respondents to report any forms of CAM used, the participants also recognized that such a format would place a heavy burden on the researcher using the questionnaire for probing to elicit a complete inventory of CAM modalities used. This type of questionnaire would also produce data that would require considerable coding to use and might not achieve the goal of producing comparable data across populations. A single general closed question would restrict the possibility of distinguishing among users of different CAM modalities. The working groups also recognized that an exhaustive list of CAM modalities applicable to all people in all countries was impossible and would make administration of the questionnaire impractical.

Thus, the final questionnaire developed was one that included a short common list of CAM modalities in each of several categories. The questionnaire also included open entries in each category for respondents to insert their most commonly used modalities if these did not appear in the fixed list. In addition, the questionnaire had space for researchers to insert modalities of local interest (in particular, traditional practitioners) that would appear as fixed items to the respondents. This made the questionnaire easy to modify for specific populations, while ensuring that a comparable list of items was always included to allow crosspopulation comparisons of CAM use. This also made the questionnaire amenable to reporting CAM at different levels, from most inclusive (e.g., any CAM) to most detailed (e.g., prayer). By being able to span this range, data from a wide range of studies could compared.8

Pretesting

The penultimate version of the questionnaire was pretested by the authors with 9 respondents in the United States and Canada to identify problems in format and interpretation. Permission for the use of human subjects for this was approved by appropriate review boards. The sample included men and women of different ages and educational levels. Cognitive interviews using a “think-aloud” technique 23 were used. Such interviews involve asking respondents to articulate their thoughts—including uncertainties of meaning and confusion about format—while completing the questionnaire. Study personnel present recorded these comments and probed the respondents further after they had completed the questionnaire. Respondents' comments led to changes in formatting but not in content. The final version was completed by 9 patients in a clinic practice, including both men and women of different ages who had a variety of diagnoses (e.g., fibromyalgia, diabetes, infertility, and hypertension) to ensure that the patients could complete the questionnaire with only the printed instructions. All 9 patients were able to do so.

Description of the NAFKAM International CAM Questionnaire (I-CAM-Q)

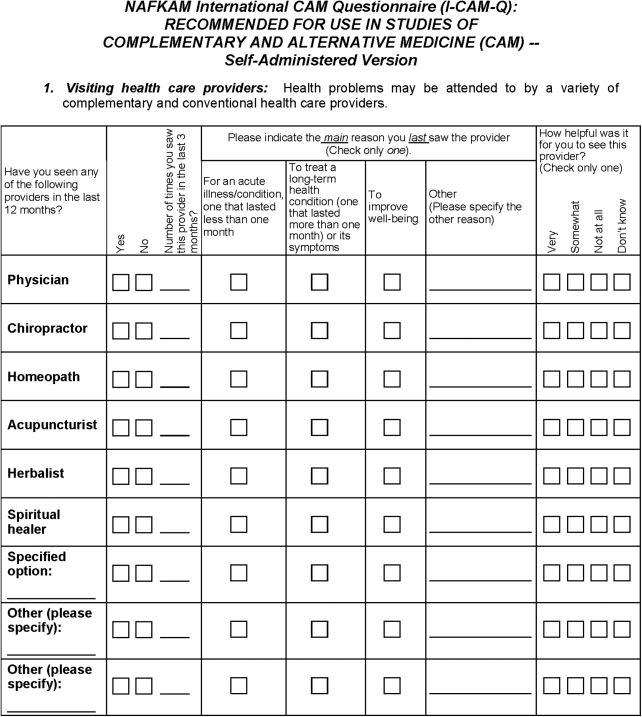

The I-CAM-Q is shown in Appendix A. It is designed to be self-administered. There are four sections, each with introductory instructions and slightly different options. An interviewer-administered version of this suitable for inclusion in a large-scale survey is on the NAFKAM website (http://uit.no/nafkam/omnafkam/?Language=en).

Section 1 includes questions about “visiting health care providers” and cues the respondent that “health problems may be attended to by a variety of complementary and conventional health care providers.” Six specific types of practitioner are listed, based on a list of core health care providers used by the World Health Organization: (1) physician; (2) chiropractor; (3) homeopath; (4) acupuncturist; (5) herbalist; and (6) spiritual healer. There is space for a specified option, which could be a locally available practitioner appropriate to the population surveyed (e.g., a cuarandero or cuarandera for Hispanic populations in the United States–Mexican border states or a Heilpraktiker for the German population) or a practitioner relevant to the health condition of the patients (e.g., a bonesetter). There are also two spaces for a respondent to add any other type of health care provider visited. Respondents are first asked whether they have seen the providers in the last 12 months. If so, the respondents are asked to indicate the number of times the providers were seen in the past 3 months. Respondents are then asked, in a forced choice, to indicate the main reason they last saw each type of provider. Four options are provided: (1) “for an acute illness/condition, one that lasted less than one month”; (2) “to treat a long-term health condition (one that lasted more than one month) or its symptoms”; (3) “to improve well-being”; or (4) “other,” with space provided to specify the other reason. These response options allow information to be specified about the use of the providers for treatment of acute or chronic conditions as well as health promotion and health maintenance. Finally, respondents are asked how helpful it was to see the providers. Ordered categories of responses are “very,” “somewhat,” “not at all,” or “don't know.”

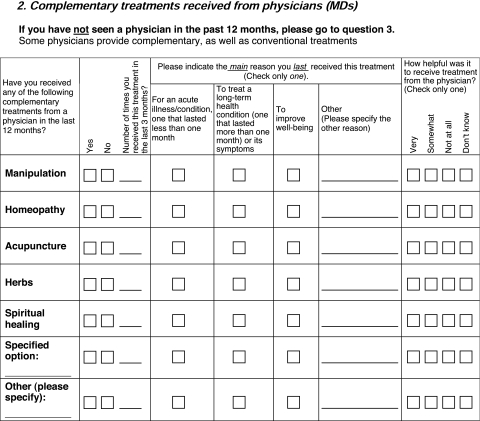

Section 2 is designed to obtain information about “complementary treatments received from physicians (M.D.s).” The intent of this section is to capture information about treatments that have been adopted by Western biomedical practice, whether in an institutionalized fashion as in the United Kingdom, or through individual integrative medicine clinics or practitioners, which is increasingly common in the United States. Respondents who report not having seen a physician in the past 12 months skip Section 2 and move directly to the next section. For respondents who have seen an M.D. in the past 12 months, Section 2 is prefaced by the statement: “Some physicians provide complementary, as well as conventional treatments.” Respondents are then asked to indicate whether they have received any of five “complementary treatments from a physician in the last 12 months.” These are (1) manipulation, (2) homeopathy, (3) acupuncture, (4) herbs, and (5) spiritual healing. There is space for a researcher-specified option and one “other” respondent-specified treatment. As in Section 1, each respondents is asked to indicate how many times he or she received the treatment in the past 3 months, the main reason for the last treatment, and how helpful it was.

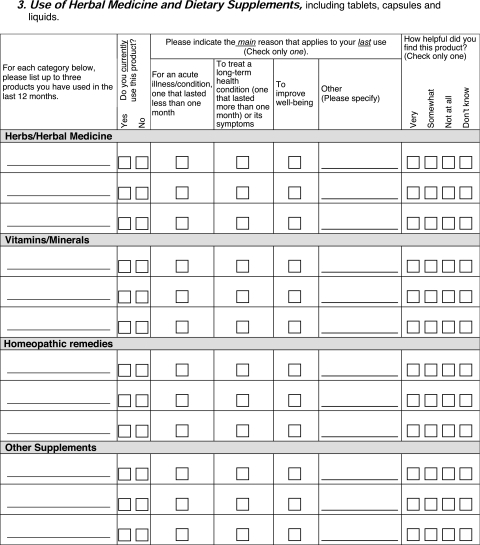

Section 3 queries “use of herbal medicine and dietary supplements, including tablets, capsules, and liquids.” Respondents are asked to list up to three products used in the last 12 months in each of four categories: (1) “herbs/herbal medicine”; (2) “vitamins/minerals”; (3) “homeopathic remedies”; and (4) “other supplements.” For each type of product listed, respondents are asked to indicate if they currently use it. Finally, they are asked the main reason for the last use, and to evaluate how helpful they found the products. Both of these questions use the same format as Sections 1 and 2.

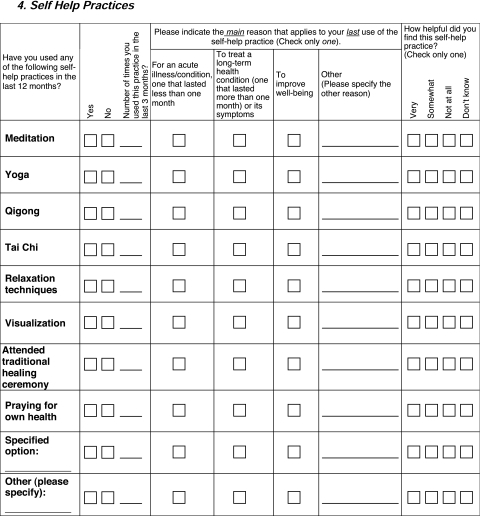

Section 4 covers “self-help practices.” Respondents are asked if they have used each of the following self-help practices in the last 12 months: meditation; yoga; qigong; t'ai chi; relaxation techniques; visualization; attending a traditional healing ceremony; or prayer for own health. There is space for a researcher-specified option and one “other” respondent-specified self-help practice. Questions about number of times used in the last 3 months, the main reason for last use of the practice, and how helpful it was are the same as in prior sections.

Translating the Questionnaire

The questionnaire was developed in English for practical reasons but it is expected that researchers will translate it into languages appropriate to study populations. Quality assurance of the translation process is important in order to maintain similar meaning and to allow cross-study comparisons of results. Standardized methods of forward and back translation should be used,24 and researchers should not underestimate the value of spending time and attention on this process. A good description of the steps involved in such a translation are contained in the manual for the Nordic Occupational Skin Questionnaire—NOSQ-2002.25

Discussion

Considerable discussion and debate surrounded the choice of timeframes for the questions. While not interested in documenting “ever use,” workshop participants considered the fact that that some remedies or practices might be used infrequently, particularly if they were for infrequently arising acute conditions. Yet, some CAMs might be used so frequently that asking respondents to quantify their use would result in heaping of data at convenient memory numbers (e.g., 10, 100, 1000). Therefore, the decision was made to ask about use in the last year, and quantification in the last 3 months. The shorter time period for precise number of visits was designed to prevent “telescoping” of respondent memories (that is, compressing visits in distant time into the 12-month window). The exception to this is Section 3, use of herbal medicine and dietary supplements. Because the array of possible products is so great and dosing schedules so varied, it was decided that use in the last 12 months, followed by “current” use was as much precision as could reasonably be obtained in a survey. “Current” was left to the respondent's interpretation because it might involve different product-specific definitions. For example, a daily vitamin might be taken every day, while an herb for asthma might be taken only when symptoms appear.

Discussion also focused on the specific modalities to list in each section. The intention was not to differentiate types of medical systems and their practitioners, therapies, and products, as what might be alternative medicine in one place in the world could be considered conventional in another. For Section 3, the decision was made to have all products listed by the respondents because of the vast array of possible products. This requires considerable coding by the researcher. However, it avoids the problem of suggestion inherent in presenting the respondent with long lists, as well as the necessity of the researcher to do formative research to discover the array of products available for the population of interest.

The developers struggled with their desire that the questionnaire not be too “Western.” Cognizant of the sheer volume and diversity of CAM modalities possible, the group chose to include researcher-specified options and respondent self-report options to allow the questionnaire to be truly international. Further work is needed to ensure the validity and reliability of this questionnaire and of translations that are produced from it. This should include tests of validity and reliability across different populations.

Conclusions

Once validated in English and in non-English speaking populations, the use of I-CAM-Q will benefit research on CAM by providing more standardized data that can be compared across studies and across countries. This will be particularly important for national comparative data on prevalence so that the data on the epidemiology of CAM use will be able to provide a more complete picture of the health care resources used in different populations. This is particularly important in environments such as the European Union, where health policy and health provision will increasingly become regional rather than national in policy. Consequently, high quality accurate data about this specific and neglected area of medicine will facilitate sensible, evidence-based decision making while taking into account both integrative and culturally appropriate health care.

Appendix

Acknowledgments

Development of this questionnaire and manuscript began at a workshop sponsored by the National Research Center in Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NAFKAM) of the University of Tromsø, Norway and the Norwegian Research Council. The authors acknowledge the input of other workshop participants: Christopher P. Alderman, Lim Alissa, Trude Bessesen, Heather Boon, Einar Borud, Gary Deng, Brit J. Drageset, Leonard E. Egede, Torkel Falkenberg, Markus Horneber, Lauri LaChance, William Lafferty, Laila Launsø, Andrew F. Long, Stephen Myers, Marit Myrvoll, Katherine M. Newton, Lisbeth Nyborg, Terje Risberg, Anne Solsvik, Jackie Wootton, Xiaorui Zhang, Suzanna Zick.

Drs. Quandt and Arcury were supported by NIH grants AT002241 and AT003635. Dr. Lewith is supported by the Rufford Maurice Laing Foundation.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial conflicts exist for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Harris P. Rees R. The prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine use among the general population: a systematic review of the literature. Complement Ther Med. 2000;8:88–96. doi: 10.1054/ctim.2000.0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM. Powell-Griner E. McFann K. Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004;343:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanssen B. Grimsgaard S. Launsø L, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in the Scandinavian countries. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2005;23:57–62. doi: 10.1080/02813430510018419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao JK. Mihaliak K. Kroenke K, et al. Use of complementary and alternative therapies for arthritis among patients of rheumaologists. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:409–416. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-131-6-199909210-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaboli PJ. Doebbling BN. Saag KG. Rosenthal GE. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by older adults with arthritis: a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:398–403. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200108)45:4<398::AID-ART354>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quandt SA. Chen H. Grzywacz JG, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by persons with arthritis: results of the National Health Interview Survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:748–755. doi: 10.1002/art.21443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arcury TA. Bell RA. Snively BM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use as health self-management: Rural older adults with diabetes. J Gerontol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61:S62–S70. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.s62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kristoffersen AE. Fønnebø V. Norheim AJ. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among patients: Classification criteria determine level of use. J Altern Complement Med. 2008;14:911–919. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinsbekk A. Adams J. Sibbritt D, et al. Socio-demographic characteristics and health perceptions among male and female visitors to CAM practitioners in a total population study. Forsch Komplementmed. 2008;15:146–151. doi: 10.1159/000134904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tindle HA. Davis RB. Phillips RS. Eisenberg DM. Trends in use of complementary and alternative medicine by US adults: 1997–2002. Altern Ther Health Med. 2005;11:42–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenfield S. Pattison H. Jolly K. Use of complementary and alternative medicine and self-tests by coronary heart disease patients. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2008;8:47. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-8-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arcury TA. Grzywacz JG. Bell RA, et al. Herbal remedy use as health self-management among older adults. J Gerontol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62:S142–S149. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.s142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessler RC. Davis RB. Foster DF, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262–268. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-4-200108210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alfred L. Claudia S. Georg S, et al. Complementary and alternative treatment methods in children with cancer: A population-based retrospective survey on the prevalence of use in Germany. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2233–2240. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arcury TA. Bell RA. Anderson AM, et al. Oral health self-care behaviors of rural older adults. J Publ Health Dent. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Boon H. Westlake K. Stewart M, et al. Use of complementary/alternative medicine by men diagnosed with prostate cancer: Prevalence and characteristics. Urology. 2003;62:849–853. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00668-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lim A. Cranswick N. Skull S, et al. Survey of complementary and alternative medicine use at a tertiary children's hospital. J Paediatr Child Health. 2005;41:424–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lønroth HL. Ekholm O. Alternative therapies in Denmark—use, users and motives for the use [in Danish] Ugeskr Laeger. 2006;168:682–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wahner-Roedler DL. Elkin PL. Lee MC, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine: Use by patients seen in different specialty areas in a tertiary-care centre. Evid Based Integrative Med. 2004;1:253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eisenberg DM. Davis RB. Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–1575. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.18.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egede LE. Ye X. Zheng D, et al. The prevalence and pattern of complementary and alternative medicine use in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:324–329. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.2.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinsbekk A. Adams J. Sibbritt D, et al. The profiles of adults who consult alternative health practitioners and/or general practitioners. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25:86–92. doi: 10.1080/02813430701267439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: An overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:229–238. doi: 10.1023/a:1023254226592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behling O. Law KS. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2000. Translating Questionnaires and Other Research Instruments. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flyvholm M-A. Susitaival P. Meding B, et al. Nordic Occupational Skin Questionnaire—NOSQ-2002. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers. 2002. www.norden.org/pub/velfaerd/arbetsmiljo/sk/2002-518.pdf. [Oct 21;2008 ]. www.norden.org/pub/velfaerd/arbetsmiljo/sk/2002-518.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]