Abstract

Retinoic acid (RA), an active vitamin A metabolite, is a key signaling molecule in vertebrate embryos. Morphogenetic RA gradients are thought to be set up by tissue-specific actions of retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (RALDHs) and catabolizing enzymes. According to the species, two enzymatic pathways (β-carotene cleavage and retinol oxidation) generate retinaldehyde, the substrate of RALDHs. Placental species depend on maternal retinol transferred to the embryo. The retinol-to-retinaldehyde conversion was thought to be achieved by several redundant enzymes; however, a random mutagenesis screen identified retinol dehydrogenase 10 [Rdh10Trex allele; Sandell LL, et al. (2007) Genes Dev 21:1113–1124] as responsible for a homozygous lethal phenotype with features of RA deficiency. We report here the production and characterization of unique murine Rdh10 loss-of-function alleles generated by gene targeting. We show that although Rdh10−/− mutants die at an earlier stage than Rdh10Trex mutants, their molecular patterning defects do not reflect a complete state of RA deficiency. Furthermore, we were able to correct most developmental abnormalities by administering retinaldehyde to pregnant mothers, thereby obtaining viable Rdh10−/− mutants. This demonstrates the rescue of an embryonic lethal phenotype by simple maternal administration of the missing retinoid compound. These results underscore the importance of maternal retinoids in preventing congenital birth defects, and lead to a revised model of the importance of RDH10 and RALDHs in controlling embryonic RA distribution.

Keywords: branchial arches, hindbrain, phenotypic rescue, heart, organogenesis

Retinoic acid (RA), an active metabolite of vitamin A, is a signaling molecule that regulates numerous developmental events in vertebrates (reviewed in refs. 1 and 2). RA acts as a ligand for nuclear receptors (RAR-RXRs) that bind target DNA sequences (RA-response elements; RAREs) and switch from transcriptional repressors to activators when liganded (reviewed in ref. 3). The distribution and levels of RA must thus be finely controlled within embryonic cell populations. Many studies have highlighted the importance of the regulation of the final step in RA biosynthesis, the oxidation of retinaldehyde (Ral) into RA, catalyzed by retinaldehyde dehydrogenases (RALDH1, 2, and 3) with evolutionary conserved expression patterns and functions (refs. 1 and 2 and references therein). Oviparous species store Ral and carotenoids (β-carotene) in the egg yolk, the latter being cleaved by a specific enzyme (BCO) to release Ral (4, 5). Another retinoid source is retinol (Rol) and retinyl esters, present in variable amounts in egg yolk according to the species (4). In placental species, Rol is the main retinoid transferred from maternal to embryonic circulation via retinol-binding protein (RBP) (6). Oxidation of Rol to Ral can be catalyzed by several enzymes from the alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) families (7, 8). It was first assumed that this reaction was achieved in an essentially redundant manner, as targeted mutations of Adh or Rdh genes led to viable mice with no congenital abnormalities (7, 9, 10). Recently, however, a random mutagenesis screen identified Rdh10 as responsible for a recessive developmental lethal phenotype (the Trex phenotype) with typical features of RA-signaling deficiency (11). Retinol dehydrogenase 10 (RDH10) was first cloned from retinal pigment epithelium (12), and is one of several RDHs acting for 11-cis-Rol oxidation during the visual cycle (13). Subsequent studies in Xenopus (14) and chick (15) further suggested that RDH10 function in embryonic Ral synthesis appeared early in vertebrate evolution.

We report here the production and characterization of unique Rdh10 murine loss-of-function alleles, and find that the homozygous mutants die at earlier stages than Rdh10Trex mutants. We performed molecular analyses focusing on the hindbrain and branchial apparatus, and report that patterning defects are less severe than those occurring under complete embryonic RA deficiency. Most importantly, we addressed the question of the importance of the spatial regulation of Ral synthesis by RDH10 by attempting maternal “replacement therapy”: We found that Ral supplementation between gastrulation and early fetal stages rescued most phenotypic defects, leading to viable Rdh10−/− mice. These findings led to a revised model of the function of RDH10 and RALDHs in the control of embryonic RA synthesis.

Results

Rdh10 Mutants Have Multiple Morphogenetic Defects Leading to Midgestational Lethality.

Two unique Rdh10 alleles (Rdh10L- and Rdh10eGFP*) were generated by gene targeting, both eliminating the catalytic domain (SI Appendix). The previous Rdh10Trex mutation is lethal at embryonic day (E)13.5–E15.5 (11, 16). To analyze the mutants, litters from both lines were collected at various developmental stages (SI Appendix, Table S1). From E8.5 to E10.5, homozygous mutants were obtained at a Mendelian frequency, whereas at E12.5, only a small fraction was recovered (n = 2 and 5; 6% and 15% of the expected numbers). No homozygous mutants were recovered postnatally. Thus, the unique Rdh10 alleles are both embryonic lethal shortly after midgestation, with a minor fraction of the mutants surviving until around E12.5. One explanation for the differing stages of lethality of Rdh10Trex and the present Rdh10 alleles might relate to genetic background.

Homozygous mutants from both Rdh10L- and Rdh10eGFP* lines were similar to wild-type (WT) littermates at early somite stages (E8.5; SI Appendix, Table S1; see below). At E9–E9.5, they showed several external abnormalities, with shortening of the posterior body, abnormal branchial arches posterior to second arches, and small, sometimes duplicated otocysts (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A–I). Some mutants (<10%) were severely affected, exhibiting incomplete body rotation, compacted cervical/upper trunk region, and abnormal heart tube. At E10.5, mutants were growth-retarded and sometimes necrotic (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 J–L). Abnormal blood stasis suggested cardiovascular failure. The forelimb buds were hypoplastic or almost undetectable (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 K and L).

RDH10 Deficiency Affects Organogenesis at E12.5.

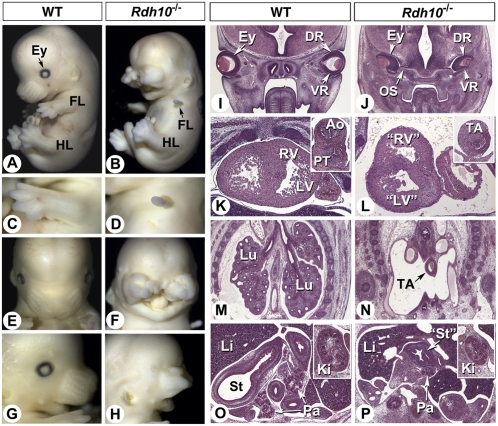

The few Rdh10−/− mutants obtained at E12.5 had severe external abnormalities, with forelimbs reduced to small protrusions (Fig. 1 A–D), facial abnormalities (Fig. 1 A and B), with severe nasal/facial clefting (Fig. 1 E and F) and truncation of the nasal processes (Fig. 1 G and H). The eyes were not visible (Fig. 1 B and H). Histological analysis showed that they had developed intracranially, close to the diencephalon (Fig. 1J). They had small though well-developed lenses and very short ventral retinae (compare Fig. 1I and Fig. 1J). Shortening of the ventral retina is a hallmark of mutants with impaired RA signaling (17–19), the present phenotype most reminiscent of that observed in compound Raldh2;Raldh3 mutants rescued by short-term RA supplementation (20).

Fig. 1.

Pleiotropic anomalies in E12.5 Rdh10−/− mutants. (A–H) External views of control (A, C, E, and G) and mutant (B, D, F, and H; Rdh10eGFP* line) embryos. (I–P) Histological analysis (hematoxylin/eosin staining) of control (I, K, M, and O) and Rdh10−/− (J, L, N, and P) embryos. Frontal sections at the level of the eyes (I and J), heart (K and L; Insets show the aortico-pulmonary/arterial trunk), lungs (M and N; these are absent in the mutant), and abdomen (O and P; Insets show the kidney). Ao, aorta; DR, dorsal retina; Ey, eye; Ki, kidney; FL, forelimb; HL, hindlimb; Li, liver; Lu, lung; LV, left ventricle; OS, optic stalk; Pa, pancreas; PT, pulmonary trunk; RV, right ventricle; St, stomach; TA, truncus arteriosus; VR, ventral retina.

Numerous visceral defects were detected histologically. The heart had no distinct left–right atria, misaligned putative ventricles, and poor myocardial trabeculation (Fig. 1 K and L). The truncus arteriosus was not septated into aorta and pulmonary trunk (Fig. 1 K and L, Insets). Lungs were absent (Fig. 1 M and N), indicating a failure of primary lung bud growth and branching morphogenesis (21). Mutants also exhibited poor morphological differentiation of the stomach and intestine, and hypoplastic liver, pancreas, and kidneys (Fig. 1 O and P). Collectively, these abnormalities recapitulate various defects observed in murine models with impaired RA synthesis (19–23) or receptor signaling (17, 24).

RDH10 Loss of Function Affects Retinoid-Responsive Genes.

Several approaches were used to demonstrate that Rdh10 loss of function affects embryonic RA signaling. First, we crossed Rdh10 mutants with RARE-hsp68-lacZ mice (25) harboring an RA-responsive transgene (11, 16, 26–28). Rdh10−/− embryos almost completely lacked lacZ activity at early somite stages, except for low levels in trunk neural tube and lateral mesoderm (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A–D). At E9.5, activity was detected at low levels in trunk neural tube and discrete regions near the foregut and heart inflow and outflow regions (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 E–H). This contrasts with the strong activation of the transgene in WT embryos in the trunk/posterior cervical region and forebrain/frontonasal tissues. These data are consistent with previous observations made on Rdh10Trex mutants (11), showing that RA signaling is severely down-regulated in the absence of RDH10 function.

Lack of RDH10 activity is expected to lead to a depletion in Ral, the substrate for RALDH enzymes. Exogenous RA administration was shown to lead to a down-regulation of Raldh2 expression in some tissues, indicating that this enzyme is regulated by its product (29). We investigated whether a deficiency in its substrate (Ral) may also impact on Raldh2 expression. Raldh2 expression was unaltered in Rdh10−/− embryos: In particular, there was no sign of ectopic expression in the cervical region or the posterior neural plate (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 I and J). This indicates that Raldh2 does not respond to a deficiency in its substrate, for instance by a compensatory up-regulation. The same conclusion was reached for Raldh3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 K and L).

We analyzed whether lack of RDH10 function affects endogenous RA target genes. The gene encoding RARβ (Rarb) is an RA-responsive gene, one of its promoters being regulated by a canonical RARE (30). Rarb expression was almost undetectable in E9 Rdh10−/− embryos, except for weak levels in branchial arches and foregut tissues (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 M and N). Hoxa1 early expression also depends on a RARE (31). Hoxa1 expression was weak and posteriorly shifted in Rdh10−/− embryos (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 O and P). These results show that RDH10 loss of function affects immediate RA-responsive genes. Down-regulation of Hoxa1 was not as severe as reported for Raldh2−/− embryos (32). This suggests that some retinaldehyde is available in Rdh10−/− embryos—either of maternal origin or through other enzyme activities, allowing some RA synthesis by RALDH2.

RDH10 Deficiency Affects Hindbrain and Cervical Patterning.

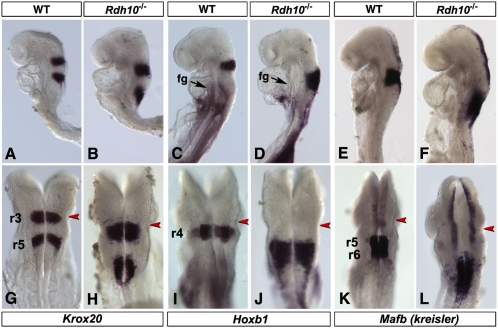

We performed a molecular analysis of the Rdh10−/− mutants. Studies performed on mouse mutants (33–35) and other vertebrate species (36–39) demonstrated that RA controls growth and patterning of the segmented hindbrain, acting as a diffusible signal and/or in increasing concentrations over time, to generate successive posterior rhombomeric fates (reviewed in refs. 2 and 40). In mouse, the most severe (“RA-depleted”) hindbrain phenotypes are observed in Raldh2−/− and in RARα;RARγ compound mutants, in which the prospective caudal hindbrain remains unsegmented and adopts a mixed prerhombomere 3/4 fate (34, 35). Three key markers were used to assess rhombomeric patterning in Rdh10−/− embryos: Krox20, a gene acting in rhombomeres (r)3 and r5 (Fig. 2 A and G); Hoxb1, an r4-specific marker (Fig. 2 C and I); and Mafb (kreisler), a determinant of r5–r6 (Fig. 2 E and K).

Fig. 2.

Rdh10 loss of function affects hindbrain patterning. Whole-mount in situ hybridizations of E8.5 (8–10 somites) embryos (Rdh10eGFP* line) with three markers of prospective rhombomeres: Krox20 (r3 and r5; A, B, G, and H), Hoxb1 (r4; C, D, I, and J), and Mafb/kreisler (r5-r6; E, F, K, and L). On dorsal views (G–L), the preotic sulcus is indicated (red arrowheads) as a visible landmark. Contrasting with the expanded expression in hindbrain, Hoxb1 is down-regulated in foregut (fg) tissues of mutants.

Krox20 was expressed in two separate stripes in mutants (Fig. 2 B and H). However, the caudal stripe (prerhombomere 5) was ill-defined and extended almost to the hindbrain/spinal cord junction (Fig. 2 G and H). The prospective r3 stripe was enlarged, with patches of ectopically expressing cells extending rostrally and caudally (Fig. 2 B and H). The Hoxb1, prerhombomere 4 stripe was enlarged in mutants, with patches of cells extending until the spinal cord level (Fig. 2 D and J). The same conclusion was reached for Mafb, normally restricted to r5–r6 (Fig. 2 E and K), and expressed in mutants as an ill-defined domain until rostral spinal cord/somitic levels (Fig. 2 F and L). Thus, Rdh10−/− mutants have marked hindbrain abnormalities, with abnormal segmentation and segregation of molecular determinants throughout prospective r4–r7 levels.

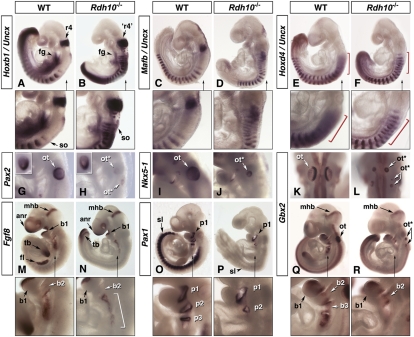

To possibly correlate these abnormalities with patterning defects in cervical mesoderm, we performed double labeling with a somitic marker, Uncx, which labels the somites as successive stripes (Fig. 3 A–F). This revealed two additional features in mutants. The first 8–10 somite pairs were abnormally compacted, whereas more posterior somites had normal size and spacing (Fig. 3 B, D, and F; compare with WT panels). Combined labeling with Hoxb1 (Fig. 3 A and B) or Mafb (Fig. 3 C and D) revealed a striking shortening of the distance between hindbrain and somitic domains, with Hoxb1+ cells almost adjacent to and Mafb+ cells overlapping Uncx-labeled somites. Pax1/Zic1 and Pax3 were used as markers for ventral (sclerotome) and dorsal (dermomyotome) somitic mesoderm. Whereas expression of sclerotomal markers was down-regulated in most Rdh10−/− embryos, Pax3 expression appeared unaffected (Fig. 3 O and P and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). This might indicate an abnormal sclerotome induction in mutants. Hoxb1 levels were also reduced in posterior foregut and trunk mesoderm of mutants (Figs. 2 C and D and 3 A and B). When analyzing Hoxd4, a marker of the r6–r7 boundary and a RARE-containing gene (41), down-regulation was seen in the hindbrain/spinal cord (Fig. 3 E and F).

Fig. 3.

Abnormal patterning of the cervical region, otocysts, and posterior branchial arches in Rdh10−/− mutants. (A–F) To correlate hindbrain abnormalities with somite formation, we performed double labeling experiments with Uncx [Hoxb1 (A and B); Mafb (C and D); Hoxd4 (E and F)]. (Lower) Details of the hindbrain/cervical region are shown (as indicated by the vertical arrows). Red brackets (E and F) highlight Hoxd4 expression in hindbrain/cervical neural tube. (G–R) Otocyst and branchial arch patterning was analyzed with various markers [Pax2 (G and H); Nkx5-1 (I and J); Gbx2 (K, L, Q, and R); Fgf8 (M and N); Pax1 (O and P)]. (Lower) Details of the branchial arches are shown. In G and H, Insets show comparable Pax2 levels in optic vesicles. Bracket in N indicates posteriorly expanded Fgf8 expression. Mutants were from Rdh10L- (B, D, F, H, L, N, P, and R) and Rdh10eGFP* (J) lines. anr, anterior neural ridge; b1–b3, branchial arches; fg, foregut; fl, forelimb; mhb, midhindbrain boundary; ot, otocyst; p1–p3, branchial pouches; r4, rhombomere 4; sl, sclerotome; so, somite; tb, tail bud.

Abnormal Patterning of Otocysts and Posterior Branchial Region.

Several developmental events are linked to segmentation and patterning of the hindbrain. Neural crest cells (NCCs) are generated from specific rhombomeres and migrate in segmental pathways to colonize the branchial arches. Rhombomeric signals are also involved in induction of the otic placode, which develops at the level of r5–r6. As both the branchial arches and otocysts are visibly affected in Rdh10−/− embryos (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 G–I), we performed molecular analysis to characterize underlying patterning defects. Among molecular determinants of the otocyst, Pax2, NKx5-1, and Gbx2 are expressed in distinct ventromedial, dorsal, and dorsomedial domains (Fig. 3 G, I, and K). The hypoplastic otocyst(s) of Rdh10−/− embryos was characterized by very weak Pax2 levels (Fig. 3H), whereas it expressed Nkx5-1 (Fig. 3J) and Gbx2 (Fig. 3L) along most or all the epithelium. This may indicate an abnormal specification of the otocyst toward dorsomedial fates, similar to what is observed in Raldh2−/− mutants (34).

We then focused on the branchial apparatus, another target of RA/RAR signaling (42–44). Fgf8 is expressed in both endoderm and ectoderm of the posterior branchial arches (Fig. 3M). Its expression correctly delineated the posterior edge of arch 2, but otherwise was weaker and posteriorly expanded in Rdh10−/− embryos (Fig. 3N). Other Fgf8 expression domains were not affected in mutants, except for prospective forelimb ectoderm (Fig. 3 M and N). Branchial pouches were analyzed with Pax1, a marker of the pouches endoderm (Fig. 3O). This revealed reduced second pouches, and lack of more posterior pouches, in mutants (Fig. 3P). Gbx2 analysis also showed almost undetectable transcripts posterior to the second arch (Fig. 3 Q and R; notice also down-regulation in spinal cord). Altogether, this analysis reveals a branchial phenotype similar to that of other murine models with altered RA/RAR signaling (42, 43).

Maternal Retinaldehyde Rescues Rdh10−/− Mutants.

The next experiments were designed to investigate the requirement of RDH10 in regulating the spatial distribution of RA. This study and a previous study (11) of Rdh10 mutants clearly demonstrate RDH10 involvement in the embryonic RA biosynthetic pathway. Two functional hypotheses can be made. As RDH10 is expressed in a tissue-specific manner (11, 45, 46), it may regulate the patterns of RA synthesis, by restricting Ral availability, and/or generate Ral “hot spots.” Alternatively, RA distribution may essentially result from the tissue-specific activity of RALDHs. To distinguish between these possibilities, we took advantage of the fact that retinoids administered maternally are transferred through yolk sac and placenta to the embryo. It was thus shown that administering RA at subteratogenic doses can rescue several—although not all—developmental defects in mutants for RA biosynthetic enzymes [Raldh2 (22, 26, 47, 48); Raldh3 (19, 49); Rdh10 (11)]. We compared the efficiency of Ral versus RA in rescuing the Rdh10−/− phenotype, the underlying hypothesis being that if RDH10 activity is critical for restricting Ral distribution, transplacentally administered Ral would not recapitulate these specific patterns and therefore might not rescue Rdh10−/− mutants to a better extent than transplacental RA.

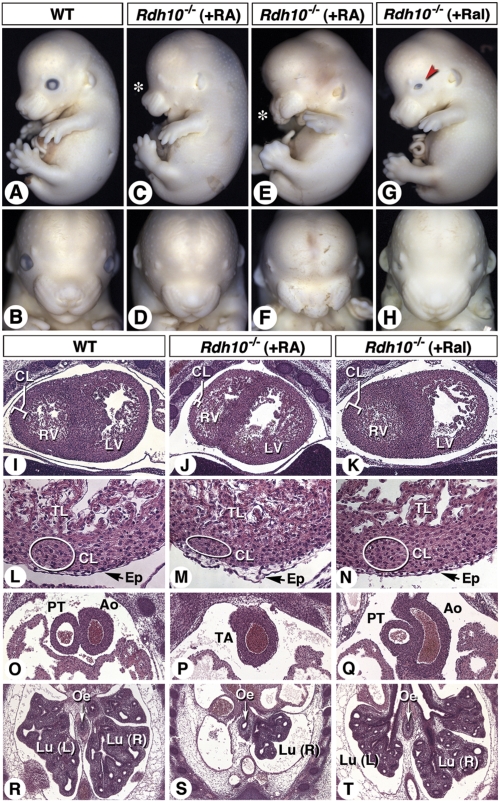

All-trans-RA or all-trans-Ral was administered to Rdh10+/− pregnant mice as supplementation of the maternal diet. The supplemented food was provided over 48 h (E7.5–E9.5) as previously described (42, 50), and fetuses were collected at E12.5–E13.5. At E12.5, the recovery of Rdh10−/− mutants was close to Mendelian frequency after RA or Ral rescue (SI Appendix, Table S2). At E13.5, the frequency of RA-rescued Rdh10−/− fetuses decreased, whereas the frequency of Ral-rescued mutants was almost Mendelian (n = 24/28 expected). In RA-treated litters, all mutants were identified by the absence or the severe reduction of the palpebral fissure (i.e., the lack of externally visible eyes; Fig. 4 A–F). Several RA-rescued mutants also had facial abnormalities, less severe than in the untreated Rdh10−/− mutants (Fig. 4 E and F; compare with Fig. 1 B and F). By contrast, all mutants obtained after Ral rescue had externally normal heads, except for their reduced palpebral fissure (Fig. 4 G and H). Forelimb development was rescued by both RA and Ral treatment. Mutants harboring the RARE-hsp68-lacZ transgene showed a rescue of reporter expression to wild-type levels following Ral treatment, whereas levels were only partly rescued by RA treatments (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

Maternal retinaldehyde rescues organ defects in Rdh10−/− mutants that cannot be rescued by RA treatment. (A–H) Profile and frontal views of the heads from E13.5 control (A and B) and Rdh10−/− mutants (Rdh10L- line) obtained after maternal supplementation with RA (C–F) or Ral (G and H) from E7.5 to E9.5. The variable rescue of facial defects in RA-rescued mutants is shown (C and E, asterisks). Ral-treated fetuses selectively display reduced palpebral fissure (G, red arrowhead). (I–T) Histological sections of heart ventricles (I–K; details in L–N), large arterial vessels (O–Q), and lungs (R–T) of WT, RA-treated, and Ral-treated Rdh10−/− fetuses. Ao, aorta; CL, myocardial compact layer; Ep, epicardium; Lu (L/R), left/right lung; LV, left ventricle; Oe, esophagus; PT, pulmonary trunk; RV, right ventricle; TA, truncus arteriosus; TL, myocardial trabecular layer.

We also checked whether maternal Ral supplementation might improve the phenotype of Raldh2−/− mutant embryos. A 48-h supplementation of Raldh2+/− pregnant mice did not improve the phenotypic features of E9.5 Raldh2−/− embryos (22, 32), and only led to minimal activity of the RARE-hsp68-lacZ reporter (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). This supports the idea that RALDH2 is the main enzyme producing RA after Ral supplementation of Rdh10 mutant embryos.

Maternal Retinaldehyde Rescues “RA-Resistant” Phenotypic Defects.

The above observations suggest that Ral maternal administration is more beneficial than RA in rescuing Rdh10−/− mutants. Previous work (21, 22, 42, 48) had identified a number of developmental events that cannot be rescued by RA in Raldh2−/− mutants, indicating an absolute requirement for region-specific enzymatic RA synthesis. In theory, these events should not—or only poorly—be rescued in RA-treated Rdh10−/− mutants, which would still lack efficient tissue-specific RA synthesis due to the lack of RDH10-dependent Ral production. We performed histological analysis of RA- and Ral-rescued mutants at E13.5. Analysis of head sections confirmed the poor rescue of nasal and ocular development in RA-treated mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A–F). These were better rescued in Ral-treated mutants, although some abnormalities also seen in Raldh3−/− mice [shortened ventral retina, reduced palpebral fissure, and choanal atresia (49)] were observed.

RA-rescued Rdh10−/− mutants (100 μg RA/g food: E7.5–E9.5) showed several cardiovascular abnormalities (reduced myocardial compact layer, epicardial detachment, and lack of septation of the truncus arteriosus; Fig. 4 I, J, L, M, O, and P). Furthermore, these mutants had no left-side lung, and had a hypoplastic right-side lung with few secondary bronchi (Fig. 4 R and S). Stomach and intestine differentiation was also poorly rescued (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 G and H). Analysis of additional mutants obtained after administering higher doses of RA and/or extending the duration of treatment (SI Appendix, Table S3) showed similar defects (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Collectively, these abnormalities are reminiscent of those seen after RA-rescue of Raldh2−/− mutants, which do not survive postnatally (21, 22, 47).

By contrast, the Ral-supplemented Rdh10−/− fetuses displayed hearts comparable to WT littermates, with normal left–right ventricular position, myocardial structure, and separate pulmonary and aortic arteries (Fig. 4 K, N, and Q). Lung development (Fig. 4T) and differentiation of abdominal organs (SI Appendix, Fig. S6I) were also rescued. Hence, various morphogenetic events were corrected in Rdh10−/− mutants after maternal Ral administration.

Maternal Retinaldehyde Rescues RA-Dependent Molecular Events.

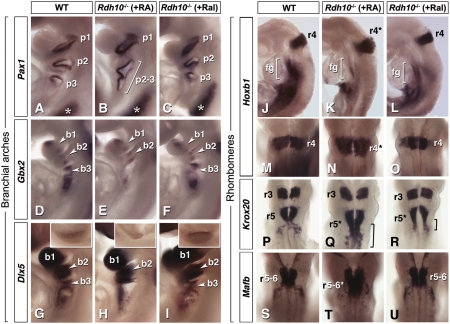

Molecular analysis was performed to assess whether early patterning defects may also be rescued through maternal Ral supply to Rdh10−/− embryos. We focused on the hindbrain and branchial arches. We found that branchial arch development was poorly improved by RA supplementation of Rdh10−/− mutants (Fig. 5 A and B: Pax1, abnormal second–third pouch; Fig. 5 D and E: Gbx2, very weak expression posterior to arch 2; Fig. 5 G and H: Dlx5, absent/hypoplastic arch 3). Strikingly, these abnormalities were corrected to a nearly WT phenotype in Rdh10−/− embryos supplemented with maternal Ral (Fig. 5 C, F, and I).

Fig. 5.

Maternal retinaldehyde rescues branchial arch and hindbrain patterning defects in Rdh10−/− mutants. Molecular analysis (gene markers indicated on the left) was performed on E9.5 (A–I) and E8.5 (J, M, P, and S) WT and Rdh10−/− embryos (Rdh10L- line) following maternal treatment with RA (K, N, Q, and T) or Ral (L, O, R, and U). Retinoid supplementation was from E7.5 until the stage of analysis. Asterisks (A–C) indicate rescue of Pax1 sclerotomal expression by both conditions. (Insets) (G–I) Dlx5 expression in prospective limb apical ectodermal ridge (AER) is shown, which is rescued only by Ral treatment. Brackets (Q and R) show expanded Krox20 expression. b1–b3, branchial arches; fg, foregut; p1–p3, branchial pouches; r4–r6, rhombomeres.

Hindbrain patterning was analyzed with the same molecular markers as above (Fig. 2). Hoxb1 analysis showed incomplete rescue of r4 in RA-supplemented Rdh10−/− mutants, r4 appearing enlarged and with patchy boundaries (Fig. 5 J, K, M, and N). Hoxb1 was also poorly rescued by maternal RA in foregut tissues (Fig. 5K). Following Ral supplementation, Rdh10−/− embryos exhibited better r4 rescue, and higher Hoxb1 expression in foregut (Fig. 5 L and O). Krox20 analysis showed a partial rescue of r5, which remained expanded in Ral-treated mutants, although to a lesser extent than in RA-supplemented mutants (Fig. 5 P–R). Mafb analysis showed a near-complete rescue of r5–r6 following Ral administration, whereas the Mafb domain remained expanded in mutants after RA treatment (Fig. 5 S–U).

Maternal Ral Treatment Allows Rdh10−/− Mice to Survive Postnatally.

Our analysis of Ral-treated Rdh10−/− embryos suggests that these mutants could be rescued to a point allowing their postnatal survival. Litters were therefore genotyped at weaning, after short-term (E7.5–E9.5) or more extended (E7.5–E11.5) RA or Ral treatments. No Rdh10−/− mice were recovered in litters from RA-treated mothers (SI Appendix, Tables S2 and S3). No viable Rdh10−/− mutant was obtained after short-term Ral treatment (n = 0/42), likely due to a nasal abnormality (choanal atresia) preventing breathing at birth and to incomplete palatal fusion (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 D–F) (49). However, after long-term Ral administration, live Rdh10−/− mutants were obtained at a Mendelian frequency (n = 20/75). These were identified by distal limb abnormalities and a characteristic spontaneous circling behavior (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 and Movie S1), which could reflect a nonrescued RDH10 function in the vestibular system (46). The rescued Rdh10−/− mice reached adulthood and were fertile.

Discussion

We have characterized the developmental and molecular outcomes of a lack of RDH10—a critical murine enzyme (11) generating Ral, the intermediate metabolite in the biosynthesis of retinoic acid. Furthermore, we report a replacement therapy by which most phenotypic effects of RDH10 loss of function can be prevented by simple maternal administration of the missing compound (Ral).

Retinol is delivered to embryonic tissues via a specific plasma protein (RBP). The Rol-to-Ral reaction is classically described as a reversible and rate-limiting step in RA synthesis. This, together with findings that Rdh10 expression domains are often more restricted than those of Raldh genes, intuitively suggested that RDH10-mediated Ral synthesis is an important step to spatially restrict the sites of RA synthesis. Strate et al. (14) suggested that generation of an RA gradient along the Xenopus embryonic axis is based on a cooperation between RDH10 and RALDH2: RDH10 generating a posteriorward flow of Ral and, as a consequence, the highest levels of RA being produced at the anterior front of RALDH2 expression. This model was also based on the notion of a feedback loop between RA levels and Rdh10 expression (14). Rdh10 expression has been analyzed in chicken and mouse but, in contrast to Xenopus, its expression is unaffected by excess RA or absence of RA in chicken (15) and is not altered in Raldh2−/− mutants. More significantly, our rescue experiments show that Rdh10 loss of function can be mainly rescued by maternal retinaldehyde administration. This indicates that localized availability of Ral is not crucial within the embryo, although an adequate level of Ral must be reached for RALDHs to generate embryonic RA.

Rdh10−/− mutants have several characteristic traits of impaired RA signaling. Molecularly, the defects do not reflect a complete RA deficiency, but are more reminiscent of conditions where RA signaling is suboptimal. This is the case for posterior branchial arch abnormalities, which phenocopy the defects observed in Raldh2−/− mutants rescued by RA supplementation (42) or hypomorphic Raldh2−/− mutants (51). Also, the hindbrain phenotype of Rdh10−/− mutants is intermediate between the severe alterations observed in Raldh2−/− and Rara−/−;Rarg−/− compound mutants (34, 35) and the more restricted “r5–r7” phenotype of Rara−/−;Rarb−/− mutants (33) (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). This suggests that in the absence of RDH10, the embryo is able to produce some Ral, likely through “less specific” enzymes such as cytosolic ADHs expressed in largely overlapping domains (ref. 7 and references therein) or other RDHs/SDRs; also, the embryo could receive some Ral from the maternal circulation (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). Knockout studies have provided evidence for ADH1, ADH3, and ADH4 functions in retinol metabolism, although none of these knockouts—even in combination—lead to developmental abnormalities. Today, more than 20 different enzymes displaying all-trans and/or cis-RDH activities have been isolated, but no loss-of-function data are available (8). We suggest that before the onset of Rdh10 expression, RALDHs may use Ral produced by ubiquitously expressed ADHs and possibly RDHs. Eventually during development, RDH10 becomes the major source of Ral, which can only be compensated for by extensive maternal supplementation.

In summary, our study leads to a paradoxical conclusion, namely RDH10 being an enzyme with tightly regulated expression and vital function—but whose lack of function can be mainly corrected by simple maternal administration of its product. This underscores the importance of RALDHs in setting up regions enriched in RA levels. Specific expression of RARs and RXRs (reviewed in ref. 52) also contributes to some of the regional effects of RA during development (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). The role of graded RA synthesis in preventing congenital malformations has mainly been inferred indirectly, for instance by showing that malformations in Raldh2−/− mutants can never be fully prevented by exogenous supply of the active ligand (22, 42, 48). We postulated that these developmental defects were because insufficient RA was reaching the pharyngeal region. Ral rescue of Rdh10−/− mutants provides a unique experimental model to investigate how these malformations can be modulated by nutrient signaling.

We propose the following evolutionary scenario with respect to RDH10 function. Marine fishes mainly use Ral and β-carotene as RA precursors (53), enzymes of the BCO family catalyzing β-carotene cleavage into Ral (4, 5). Although the role of the Rdh10 homolog(s) remains to be established in zebrafish, recent studies demonstrated a function of RDH10 in early Xenopus development (14), and expression data suggested a conserved role in avian embryos (15). There may be a trend toward higher Rol/retinyl esters (versus Ral/carotenoids) stores in eggs from amphibian and amniote species. However, the “choice” of the main retinoid seems to be species-specific, even within a single clade. For instance, in chicken and gull eggs, Rol is the dominant retinoid, whereas Ral is the major storage form in goose and duck eggs (4). RDH10 might have had an ancestral function as a RDH acting in the visual cycle (13). Its recruitment as an embryonic RDH, acting additionally to carotenoid cleavage enzymes, would have provided robustness for ensuring an appropriate supply of Ral to the embryo. It also allowed modulating availability of Ral in some tissues, offering an evolutionary advantage in refining or modulating retinoid gradients. RDH10 function thus became critical in placental species, in which Rol is the main retinoid reaching the embryo.

Finally, our results underscore the importance of an adequate supply of retinoids during mammalian—including human—pregnancy. Although the prevalence of RDH10 mutations has not yet been assessed in humans, it is conceivable that mutations for genes of the retinoid synthesis pathway, for instance transheterozygous mutations affecting RDH10 and a RALDH gene, may be involved in nonmonogenic cases of birth defects or neonatal abnormalities. Their incidence or severity may be increased in cases of even subclinical vitamin A deficiency: in poor countries, in cases of imbalanced diets (e.g., strict vegan diets), or in pathological conditions including anorexia.

Materials and Methods

Embryonic analyses were performed according to standard procedures (histology, in situ hybridization, and X-gal assays). Details and references to relevant protocols are available in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. The Rdh10-engineered alleles are also described.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Drs. M. C. Birling and S. Jacquot for engineering Rdh10 alleles, and V. Fraulob and C. Haushalter for assistance. This work was supported by funds from CNRS, INSERM, Université de Strasbourg, and grants from Agence Nationale de la Recherche, Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, Réseau National des Génopoles (P.D.), National Institutes of Health (R01), and Dell Research Foundation (K.N.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1103877108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Duester G. Retinoic acid synthesis and signaling during early organogenesis. Cell. 2008;134:921–931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Niederreither K, Dollé P. Retinoic acid in development: Towards an integrated view. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:541–553. doi: 10.1038/nrg2340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rochette-Egly C, Germain P. Dynamic and combinatorial control of gene expression by nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RARs) Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e005. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simões-Costa MS, Azambuja AP, Xavier-Neto J. The search for non-chordate retinoic acid signaling: Lessons from chordates. J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol. 2008;310:54–72. doi: 10.1002/jez.b.21139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lampert JM, et al. Provitamin A conversion to retinal via the β,β-carotene-15,15′-oxygenase (bcox) is essential for pattern formation and differentiation during zebrafish embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130:2173–2186. doi: 10.1242/dev.00437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ward SJ, Chambon P, Ong DE, Båvik C. A retinol-binding protein receptor-mediated mechanism for uptake of vitamin A to postimplantation rat embryos. Biol Reprod. 1997;57:751–755. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod57.4.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duester G, Mic FA, Molotkov A. Cytosolic retinoid dehydrogenases govern ubiquitous metabolism of retinol to retinaldehyde followed by tissue-specific metabolism to retinoic acid. Chem Biol Interact. 2003;143-144:201–210. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00204-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lidén M, Eriksson U. Understanding retinol metabolism: Structure and function of retinol dehydrogenases. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13001–13004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu P, Zhang M, Napoli JL. Ontogeny of rdh9 (Crad3) expression: Ablation causes changes in retinoid and steroid metabolizing enzymes, but RXR and androgen signaling seem normal. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1770:694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molotkov A, et al. Stimulation of retinoic acid production and growth by ubiquitously expressed alcohol dehydrogenase Adh3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5337–5342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082093299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandell LL, et al. RDH10 is essential for synthesis of embryonic retinoic acid and is required for limb, craniofacial, and organ development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1113–1124. doi: 10.1101/gad.1533407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu BX, et al. Cloning and characterization of a novel all-trans retinol short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase from the RPE. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:3365–3372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farjo KM, Moiseyev G, Takahashi Y, Crouch RK, Ma JX. The 11-cis-retinol dehydrogenase activity of RDH10 and its interaction with visual cycle proteins. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:5089–5097. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strate I, Min TH, Iliev D, Pera EM. Retinol dehydrogenase 10 is a feedback regulator of retinoic acid signalling during axis formation and patterning of the central nervous system. Development. 2009;136:461–472. doi: 10.1242/dev.024901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reijntjes S, Zile MH, Maden M. The expression of Stra6 and Rdh10 in the avian embryo and their contribution to the generation of retinoid signatures. Int J Dev Biol. 2010;54:1267–1275. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.093009sr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cunningham TJ, Chatzi C, Sandell LL, Trainor PA, Duester G. Rdh10 mutants deficient in limb field retinoic acid signaling exhibit normal limb patterning but display interdigital webbing. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1142–1150. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kastner P, et al. Genetic evidence that the retinoid signal is transduced by heterodimeric RXR/RAR functional units during mouse development. Development. 1997;124:313–326. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Matt N, et al. Retinoic acid-dependent eye morphogenesis is orchestrated by neural crest cells. Development. 2005;132:4789–4800. doi: 10.1242/dev.02031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molotkov A, Molotkova N, Duester G. Retinoic acid guides eye morphogenetic movements via paracrine signaling but is unnecessary for retinal dorsoventral patterning. Development. 2006;133:1901–1910. doi: 10.1242/dev.02328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halilagic A, et al. Retinoids control anterior and dorsal properties in the developing forebrain. Dev Biol. 2007;303:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Z, Dollé P, Cardoso WV, Niederreither K. Retinoic acid regulates morphogenesis and patterning of posterior foregut derivatives. Dev Biol. 2006;297:433–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niederreither K, et al. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for heart morphogenesis in the mouse. Development. 2001;128:1019–1031. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.7.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martín M, et al. Dorsal pancreas agenesis in retinoic acid-deficient Raldh2 mutant mice. Dev Biol. 2005;284:399–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendelsohn C, et al. Function of the retinoic acid receptors (RARs) during development (II). Multiple abnormalities at various stages of organogenesis in RAR double mutants. Development. 1994;120:2749–2771. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.10.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rossant J, Zirngibl R, Cado D, Shago M, Giguère V. Expression of a retinoic acid response element-hsplacZ transgene defines specific domains of transcriptional activity during mouse embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1333–1344. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.8.1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao X, et al. Retinoic acid promotes limb induction through effects on body axis extension but is unnecessary for limb patterning. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1050–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dollé P, Fraulob V, Gallego-Llamas J, Vermot J, Niederreither K. Fate of retinoic acid-activated embryonic cell lineages. Dev Dyn. 2010;239:3260–3274. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ribes V, Le Roux I, Rhinn M, Schuhbaur B, Dollé P. Early mouse caudal development relies on crosstalk between retinoic acid, Shh and Fgf signalling pathways. Development. 2009;136:665–676. doi: 10.1242/dev.016204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niederreither K, McCaffery P, Dräger UC, Chambon P, Dollé P. Restricted expression and retinoic acid-induced downregulation of the retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 2 (RALDH-2) gene during mouse development. Mech Dev. 1997;62:67–78. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Thé H, Vivanco-Ruiz MM, Tiollais P, Stunnenberg H, Dejean A. Identification of a retinoic acid responsive element in the retinoic acid receptor β gene. Nature. 1990;343:177–180. doi: 10.1038/343177a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dupé V, et al. In vivo functional analysis of the Hoxa-1 3′ retinoic acid response element (3′RARE) Development. 1997;124:399–410. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niederreither K, Subbarayan V, Dollé P, Chambon P. Embryonic retinoic acid synthesis is essential for early mouse post-implantation development. Nat Genet. 1999;21:444–448. doi: 10.1038/7788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dupé V, Ghyselinck NB, Wendling O, Chambon P, Mark M. Key roles of retinoic acid receptors α and β in the patterning of the caudal hindbrain, pharyngeal arches and otocyst in the mouse. Development. 1999;126:5051–5059. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.22.5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niederreither K, Vermot J, Schuhbaur B, Chambon P, Dollé P. Retinoic acid synthesis and hindbrain patterning in the mouse embryo. Development. 2000;127:75–85. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wendling O, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P, Mark M. Roles of retinoic acid receptors in early embryonic morphogenesis and hindbrain patterning. Development. 2001;128:2031–2038. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.11.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dupé V, Lumsden A. Hindbrain patterning involves graded responses to retinoic acid signalling. Development. 2001;128:2199–2208. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.12.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gale E, Zile M, Maden M. Hindbrain respecification in the retinoid-deficient quail. Mech Dev. 1999;89:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maves L, Kimmel CB. Dynamic and sequential patterning of the zebrafish posterior hindbrain by retinoic acid. Dev Biol. 2005;285:593–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.White RJ, Nie Q, Lander AD, Schilling TF. Complex regulation of cyp26a1 creates a robust retinoic acid gradient in the zebrafish embryo. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gavalas A. ArRAnging the hindbrain. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:61–64. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02067-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nolte C, Amores A, Nagy Kovács E, Postlethwait J, Featherstone M. The role of a retinoic acid response element in establishing the anterior neural expression border of Hoxd4 transgenes. Mech Dev. 2003;120:325–335. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niederreither K, et al. The regional pattern of retinoic acid synthesis by RALDH2 is essential for the development of posterior pharyngeal arches and the enteric nervous system. Development. 2003;130:2525–2534. doi: 10.1242/dev.00463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wendling O, Dennefeld C, Chambon P, Mark M. Retinoid signaling is essential for patterning the endoderm of the third and fourth pharyngeal arches. Development. 2000;127:1553–1562. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Retinoic acid signalling in the development of branchial arches. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cammas L, Romand R, Fraulob V, Mura C, Dollé P. Expression of the murine retinol dehydrogenase 10 (Rdh10) gene correlates with many sites of retinoid signalling during embryogenesis and organ differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:2899–2908. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romand R, Kondo T, Cammas L, Hashino E, Dollé P. Dynamic expression of the retinoic acid-synthesizing enzyme retinol dehydrogenase 10 (rdh10) in the developing mouse brain and sensory organs. J Comp Neurol. 2008;508:879–892. doi: 10.1002/cne.21707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin SC, et al. Endogenous retinoic acid regulates cardiac progenitor differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9234–9239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910430107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mic FA, Haselbeck RJ, Cuenca AE, Duester G. Novel retinoic acid generating activities in the neural tube and heart identified by conditional rescue of Raldh2 null mutant mice. Development. 2002;129:2271–2282. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.9.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dupé V, et al. A newborn lethal defect due to inactivation of retinaldehyde dehydrogenase type 3 is prevented by maternal retinoic acid treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14036–14041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2336223100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Niederreither K, Vermot J, Fraulob V, Chambon P, Dollé P. Retinaldehyde dehydrogenase 2 (RALDH2)-independent patterns of retinoic acid synthesis in the mouse embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:16111–16116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252626599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vermot J, Niederreither K, Garnier JM, Chambon P, Dollé P. Decreased embryonic retinoic acid synthesis results in a DiGeorge syndrome phenotype in newborn mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1763–1768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437920100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dollé P. Developmental expression of retinoic acid receptors (RARs) Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e006. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lubzens E, Lissauer L, Levavi-Sivan B, Avarre JC, Sammar M. Carotenoid and retinoid transport to fish oocytes and eggs: What is the role of retinol binding protein? Mol Aspects Med. 2003;24:441–457. doi: 10.1016/s0098-2997(03)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.