Abstract

Several classes of small noncoding RNAs are key players in cellular metabolism including mRNA decoding, RNA processing, and mRNA stability. Here we show that a tRNAAsp isodecoder, corresponding to a human tRNA-derived sequence, binds to an embedded Alu RNA element contained in the 3′ UTR of the human aspartyl-tRNA synthetase mRNA. This interaction between two well-known classes of RNA molecules, tRNA and Alu RNA, is driven by an unexpected structural motif and induces a global rearrangement of the 3′ UTR. Besides, this 3′ UTR contains two functional polyadenylation signals. We propose a model where the tRNA/Alu interaction would modulate the accessibility of the two alternative polyadenylation sites and regulate the stability of the mRNA. This unique regulation mechanism would link gene expression to RNA polymerase III transcription and may have implications in a primate-specific signal pathway.

Keywords: aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase, posttranscriptional regulation

Alu elements are the most abundant repetitive element in primate genomes. They belong to the short interspersed element family and are classified into subfamilies according to their appearance during evolution. Typically, there are more than 1 million Alu elements in a primate genome, which represents 10% of the genome overall. Modern Alu elements are about 300 base-pairs (bp) long and adopt a conserved structure composed of two similar, but distinct, domains (left and right arms) joined by an A-rich linker and followed by a short polyadenylation [poly(A)] stretch. Moreover, Alu elements are transcribed by RNA polymerase III (pol III), and Alu RNA transcripts are present in the cytosol of primate cells (1).

Alu sequences are considered to be a huge reservoir of potential regulatory elements, which may have been involved in primate evolution and possibly facilitated their divergence from other mammals (2). Indeed, insertion of Alu elements could provide previously undescribed regulatory motifs to neighboring genes by creating previously undescribed transcription enhancers or promoters (3, 4). Alu elements can also modulate protein expression in a posttranscriptional way by at least two different mechanisms: (i) they are transcribed as free Alu RNA by the RNA PolIII, assembled into Alu ribonucleo-protein particles and act as transregulatory factors (2, 5, 6); or (ii) their transcription as a part of a mRNA will define them as cis-regulatory elements (7). If the Alu sequence is localized within the mRNA open reading frame, it can either affect gene expression by sequence disruption or, alternatively, simply add to the protein amino acid sequence (8). Nevertheless, most of the time they are present in 5′ and 3′ UTRs (2, 9, 10).

Several reports indicate that mRNAs containing Alu elements in their 3′ UTRs are associated with cell growth and differentiation (11–15). Indeed, their presence could affect the processing of mRNAs at multiple levels (16). Specifically, they have been shown to modulate alternative splicing (e.g., ref. 17), RNA editing (e.g., ref. 18), nuclear retention (19), and STAU1-mediated mRNA decay (20) and to create AU-rich elements that regulate mRNA stability (21). In addition, Alu elements have been shown to introduce previously undescribed 3′ UTR polyadenylation sites (22), thereby affecting 3′ end processing efficiency, as well as alternative 3′ end selection. Remarkably, several examples stress the essential contribution of 3′ end processing in physiological (e.g., immunity and inflammation) or pathological processes (e.g., cancer and viral infection) (23). Maturation of the 3′ end of the mRNA is a nuclear cotranscriptional process that promotes transport of mRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm and affects the stability and the translation efficiency of mRNAs. This process consists of the recognition of defined polyadenylation [poly(A)] signals in the pre-mRNA 3′ UTR by a large cleavage/polyadenylation machinery. For transcripts containing more than one poly(A) signal, which is the majority of the pre-mRNAs (24–26), the basis of the mechanisms involved in poly(A) selection is still not understood and the role of regulatory factors remains undefined (27).

Interestingly, we made the observation that the mRNA encoding the human aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS) displays both a partial Alu insertion (3′ end of the AluJ right arm) and two optimal poly(A) signals in its 3′ UTR. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) are ubiquitous enzymes that attach amino acids to their cognate tRNAs during protein synthesis. They ensure the high fidelity of the tRNA aminoacylation process, thereby maintaining the genetic code and contributing to cell viability (28). Our data show that (i) a human tRNAAsp sequence adopts a peculiar structure, (ii) it binds to the Alu insertion within the 3′ UTR of AspRS mRNA, (iii) it stimulates specifically the expression of a luciferase reporter gene fused to this 3′ UTR, (iv) it alters the 3′ UTR overall folding, and (iv) the regulatory function of the 3′ UTR is related not only to the Alu insertion but also to two functional polyadenylation sites. We propose a model consistent with all these observations, in which the tRNAAsp isodecoder, by binding the Alu insertion, would direct alternative polyadenylation of AspRS mRNA and modulate its expression. We show that a tRNA isodecoder could act as a noncoding RNA (ncRNA), and we discuss its potential implication in a pathway important in cellular metabolism.

Results

AspRS mRNA 3′ UTR Displays Two Poly(A) Signals and a Partial Alu Sequence.

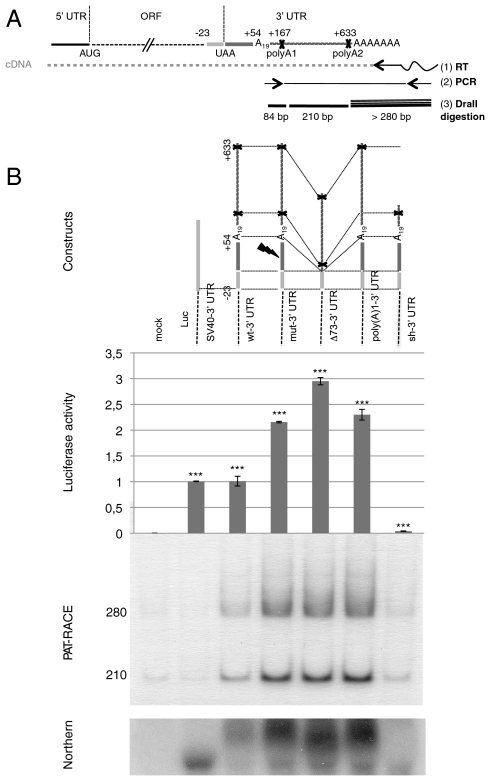

Human AspRS is a protein of 500 amino acids, encoded on chromosome 2. The corresponding mature 2,215 nucleotide (nt) mRNA is characterized by a short 5′ UTR (79 nt) and a predicted 633-nt 3′ UTR containing two polyadenylation signals (Fig. 1A). This transcript is of low abundance and could not be detected by Northern blotting experiments, as verified by quantitative PCR. Therefore, we used RNA ligase mediated RACE by PCR (RLM-RT-RACE PCR) to establish the nucleotide sequence of the different 3′ ends of AspRS mRNA transcripts produced in humans (Fig. S1A). This approach was performed on three different RNA samples purified from human brain, muscle, and breast tissues. Cloning and sequencing of DNA products revealed the presence of two transcripts that matched the genomic sequence (Fig. S1B, arrows). The shortest 3′ UTR sequence corresponds to a proximal cleavage site positioned at nt 167 in the 3′ UTR, whereas the longest corresponds to a distal cleavage site located at position 633, both of them ending with a cytidine thymidine dinucleotide. Each transcript contains a canonical poly(A) signal, defined by two primary sequence elements: a AAUAAA hexamer found 13 and 11 nt upstream and a U/GU-rich region located 15 and 19 nt downstream of both cleavage sites, respectively. Furthermore, UGUA elements, which serve as additional anchors for the 3′ end processing machinery, are also present in the two transcripts (29).

Fig. 1.

AspRS 3′ UTR variants and luciferase reporter gene expression. (A) Global organization of the complete AspRS mRNA and PAT-RACE principle: UTRs and ORF are indicated. Positions numbers are relative to the UAA stop codon. The 3′ UTR contains an Alu sequence located downstream the stop codon (up to position +54) and two predicted polyadenylation signals (polyA1 and polyA2 at positions 167 and 633, respectively). In vitro probing of the junction between the ORF and the 3′UTR showed that the Alu sequence has the capacity to form a stem loop with the last 23 nts of the ORF; therefore, we chose to fuse this entire domain in the reporter system in order to present the Alu sequence in its native structural context (cotranscriptional folding). In PAT-RACE experiments, this mRNA is first reverse transcribed using a “PAT adapter” primer. The resulting cDNA is then amplified using a primer complementary to the adapter and a primer designed intentionally to hybridize after the internal polyA sequence (A19) to avoid background. DraII digestion of radioactive PCR products lead to three fragments of 84, 210, and about 280 nts. This longest fragment is specified by the presence of different polyA tails, initially used to reverse transcribe the mRNA and the shortest fragment was not visible on gels. (B) Schematic representation of reporter constructs: WT-3′ UTR, wild-type sequence including the 23 last nts of AspRS ORF and the 633 nt of the 3′ UTR, Mut-3′ UTR is the Alu mutated version (sequence  was replaced by

was replaced by  ), Δ73-3′ UTR corresponds to the 3′ UTR missing the 54-nt-long Alu sequence and the 19-A stretch, poly(A)1-3′ UTR has its first poly(A) signal AATAAA mutated into AATGCA and Sh-3′ UTR ends at nt 213 and displays only the first poly(A) signal. Finally, SV40-3′ UTR was used as a control. Gene expression is monitored at the protein level with the luciferase activity (Middle, standard deviation values of three independent transfections) and at the mRNA level (Bottom); relative mRNA concentrations are estimated by RACE-PAT (30) and by Northern blotting. Error bars indicating the standard deviation are given. *** shows statistical significance (AspRS 3′ UTR fusions versus SV40 3′ UTR) at P < 0.001 (Welch’s t test).

), Δ73-3′ UTR corresponds to the 3′ UTR missing the 54-nt-long Alu sequence and the 19-A stretch, poly(A)1-3′ UTR has its first poly(A) signal AATAAA mutated into AATGCA and Sh-3′ UTR ends at nt 213 and displays only the first poly(A) signal. Finally, SV40-3′ UTR was used as a control. Gene expression is monitored at the protein level with the luciferase activity (Middle, standard deviation values of three independent transfections) and at the mRNA level (Bottom); relative mRNA concentrations are estimated by RACE-PAT (30) and by Northern blotting. Error bars indicating the standard deviation are given. *** shows statistical significance (AspRS 3′ UTR fusions versus SV40 3′ UTR) at P < 0.001 (Welch’s t test).

Another characteristic of this 3′ UTR sequence is the presence of a short insertion 11 nt downstream of the stop codon (boxed in Fig. S1B). This insertion is conserved in all primate mRNA sequences identified (Pan troglodytes, Macaca mulatta, Callithrix jacchus, Pongo abelii, and Gorilla gorilla), but absent in other mammal sequences. It matches the sequence of the AluJ right arm (in the sense orientation) followed by a poly(A) stretch (19 to 29 A). A second insertion specific to primate sequences, not investigated in this study, is found close to the mRNA 3′ end.

Functional Motifs Within the 3′ UTR.

To assess the importance of both the Alu insertion and the proximal and distal poly(A) signals for gene control, the AspRS mRNA 3′ UTR or different variants were fused directly downstream of the stop codon of the luciferase (Luc) reporter gene (Fig. 1B). All constructs include the last 23 nt from the AspRS ORF because this sequence is partially complementary to the Alu insertion, an observation that was confirmed by in vitro probing experiments. Constructs were transfected into mouse Hepa 1–6 cells and the luciferase activity was measured (Fig. 1B). In comparison with the WT AspRS 3′ UTR (WT-3′ UTR), substantial stimulation of luciferase activity was observed when (i) the Alu insertion is mutated (mut-3′ UTR) or deleted (Δ73-3′ UTR) and (ii) the proximal poly(A) signal is removed [poly(A)1-3′ UTR]. On the contrary, shortening the 3′ UTR at position 213, downstream of the proximal poly(A) signal (sh-3′ UTR), leads to a strong reduction in luciferase expression.

In order to measure specifically the amount of the corresponding mRNAs, we used Northern blotting and the RACE Poly(A) Test (RACE-PAT) (30). RACE-PAT products derived from Luc fusions were further digested with DraII and two specific fragments, corresponding to the longest transcript, were detected: a 210-bp fragment and a 280-bp fragment ending with the poly(A) tail (Fig. 1 A and B). The shortest transcript was not detected by this technique, indicating that it is highly unstable. Variations in mRNA expression level correlate with luciferase activity; this suggests that Luc expression is controlled by mRNA concentration, which in turn is governed by distinct motifs within its 3′ UTR: The region 167–633 stabilizes the mRNA, whereas the Alu insertion, as well as the proximal poly(A) signal, destabilizes the mRNA.

Three Striking tRNAAsp Isodecoders Are Encoded by the Human Genome.

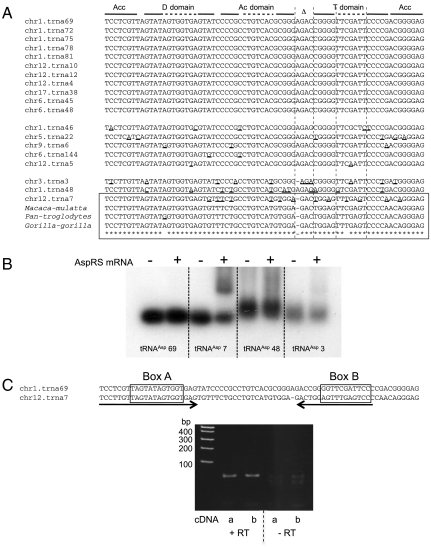

Remarkably, we observed that the Alu insertion present in the AspRS mRNA 3′ UTR is complementary to the tRNAAsp sequence. A total of 19 human tRNAAsp sequences are referenced in the genomic tRNA database (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/), all corresponding to a unique isoacceptor (GUC anticodon), but nine tRNAAsp isodecoders: tRNAs with the same anticodon, but different cores (31) (Fig. 2A). Three families can be distinguished: (i) Eleven tRNA sequences are identical and considered as the reference molecules (tRNAAsp69, 72, 75, 78, 81, 10, 12, 4, 38, 45, and 48), (ii) five contain at most 6 mutations that do not affect conserved residues (tRNAAsp46, 22, 6, 144, and 5), and (iii) three sequences differ significantly from the reference by 11 to 13 mutations (tRNAAsp3, 48, and 7). This last family displays major variations in the variable region and/or in the T-loop sequence. Indeed, tRNAAsp48 has a G54 instead of the strictly conserved U54 in its T loop, whereas tRNAAsp3 and 7 have both a shorter variable region made up of only 2 nt instead of 3. In addition, tRNAAsp7 has a T56 instead of a C56 in the conserved motif TΨC defining the T loop. Despite these major sequence variations, all three unconventional tRNAAsp sequences could still adopt, in theory, the classical cloverleaf tRNA structure; however, tertiary interactions between the D and T loops are unlikely (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Sequences of Homo sapiens tRNAAsp genes and characterization of the most divergent isodecoders. (A) Sequences of tRNAAsp genes registered in the genomic tRNA database (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/) are listed with their numbering and chromosome localization. The general 2D organization of tRNAs is specified on the top: “Acc” stands for acceptor arm, “D domain” for D arm and loop, “Ac domain” for anticodon arm and loop, “Δ” symbolizes the variable region, and “T domain” stands for T arm and loop. Nucleotides in tRNAAsp isodecoders that differ from the most frequent tRNAAsp sequence are underlined. A unique tRNAAsp7 homologue was identified in three primate genomes, namely M. mulatta, P. troglodytes, and G. gorilla (boxed). (B) Detection of putative complexes between tRNA isodecoders and AspRS mRNA. Gel shift assays were performed with radio-labeled tRNAAsp69, 7, 48, or 3 in the presence (+) and absence (−) of 500 nM AspRS mRNA. (C) Detection of tRNAAsp7 in human total RNA. The RNA product corresponding to the trna7 gene, encoded on chromosome 12, was detected only by RT-PCR. A couple of primers have been specifically designed to hybridize (arrows) on the sequences surrounding the putative A and B boxes of tRNAAsp7. For two independent experiments (a and b), PCR controls were performed on the same RNA samples (DNase treated), not subjected previously to reverse transcription. Resultant PCR products were then cloned and sequenced; they all matched tRNAAsp7 sequence.

The reference tRNAAsp sequence (tRNAAsp69), as well as tRNAAsp3, tRNAAsp48, and tRNAAsp7, were produced by in vitro transcription and assayed for their capacity to be aminoacylated by human AspRS. Surprisingly, whereas tRNAAsp69 is efficiently aspartylated, none of the other isodecoders tested are substrates for AspRS in vitro (Fig. S2), despite the conservation of the major aspartate identity nucleotides (32).

All four tRNAs show large sequence complementarity with the Alu insertion of AspRS mRNA 3′ UTR. Transcripts were tested for their ability to bind AspRS mRNA in vitro (Fig. 2B). Among them, only tRNAAsp7 formed a stable duplex with AspRS mRNA. Indeed, its migration is delayed when the full-length AspRS mRNA is added to the binding assay. This indicates that specific sequence or structural motifs in the tRNAAsp7 molecule induce a stable complex with the mRNA.

Expression of endogenous tRNAAsp7 was verified in HeLa cells. It was detectable only by RT-PCR and verified by sequencing, indicating that it is expressed at a very low level (Fig. 2C).

tRNAAsp7 Binds Specifically the Alu Insertion.

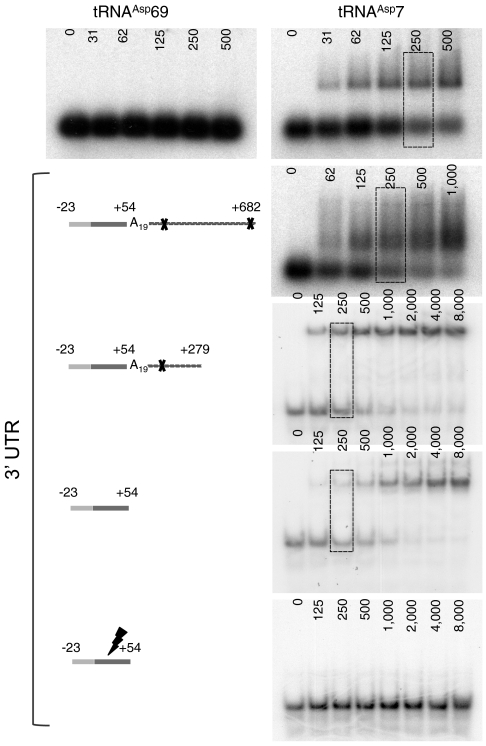

Various transcripts of AspRS mRNA were tested for their capacity to bind tRNAAsp7 in vitro (Fig. 3). P32-labeled tRNAAsp7 transcript was incubated with increasing concentrations of (i) the full-length mRNA, (ii) the 3′ UTR sequence (-23 + 633), (iii) a shorter version of the 3′ UTR (-23 + 279), (iv) the wild-type Alu sequence (-23 + 54), or (v) a mutated Alu sequence. Whereas none of the mRNA variants interact with the canonical tRNAAsp69 (data shown for the full-length mRNA only), all constructs, which contain the intact Alu insertion, strongly bind tRNAAsp7. Indeed, apparent KD is about 250 nM, and only mutations within the Alu sequence hinder completely the interaction.

Fig. 3.

Complex formation between tRNAAsp7 and AspRS 3′ UTR. The global organization of the different 3′ UTR variants is displayed. The resolution of the gels was adapted to the length of the tested mRNA: 1% agarose gels for the longest mRNA transcripts (more than 700 nts) and 6% polyacrylamide gels for shorter ones (less than 300 nts). Increasing mRNA concentrations are indicated at the tops of the autoradiograms, and dashed boxes designate the mRNA concentration for which about 50% of the radio-labeled tRNAAsp7 is shifted (Kd). For each variant tested, tRNAAsp69 was used as a control; here only the experiment performed with the full-length mRNA is presented.

tRNAAsp7 Does Not Fold as a Cloverleaf.

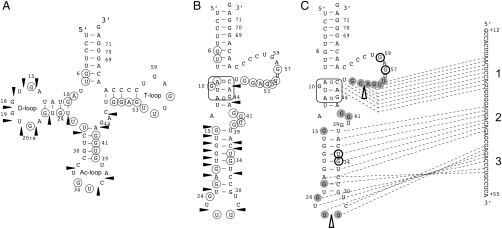

Structure mapping experiments were performed on the tRNAAsp7 transcript using enzymatic probes. Nucleases T1 and S1 are known to specifically cleave unpaired nucleotides, whereas nuclease V1 is specific for double-stranded and structured regions. Analysis of the cleavage pattern reveals that tRNAAsp7 does not fold into the expected canonical cloverleaf structure [see lanes minus Alu (-23 + 54) on the autoradiogram in Fig. S3A]. Indeed, accessibilities to single-stranded probes T1 and S1 (circled nt in Fig. 4A) are clearly present in the T, anticodon (Ac), and D arms, whereas in the double-stranded probe, V1 (arrows) cuts in the D loop of the putative cloverleaf structure.

Fig. 4.

tRNAAsp7 adopts an alternative secondary structure. Data of enzymatic probing are summarized on tRNAAsp7 (A) putative cloverleaf representation or on (B) an alternative structure. Positions cut by single stranded probes (S1 and T1) are specified with circles and V1 cleavages are indicated with arrows. The E-loop motif is squared. (C) Putative interactions with the Alu insertion of AspRS mRNA 3′ UTR are distributed within three blocks (1, 2, and 3). Results of footprinting experiments in the presence of Alu (-23 + 54) are indicated: Nt protected from S1 and T1 digestion are gray-colored; increased accessibilities are shown with thick open circles (S1 and T1) and triangles (V1).

Lead (Pb2+) was further used to probe and compare the global accessibility of both tRNAAsp69 (reference tRNAAsp) and tRNAAsp7 (Fig. S3B). Profiles are drastically different between the two molecules. The classical profile expected for the canonical cloverleaf structure was obtained for tRNAAsp69; however, the profile corresponding to tRNAAsp7 reveals clear discrepancies, confirming the previous observations obtained with enzymatic probes (Fig. 3B). In particular, the frequency of lead cleavages (lane 10 mM Pb2+) is much lower for tRNAAsp7 compared to the reference tRNA, suggesting a more compact structure. Only positions 24–30 and 50–59 show stronger hydrolysis. Based on all our in vitro probing data, we propose an alternative structure (Fig. 3C), where tRNAAsp7 folds into an elongated structure containing a large internal loop made up by 16 nt. The only tRNA feature conserved in this structure corresponds to the acceptor stem.

However, the presence of two unexpected V1 cleavages (nt 44 and 46) as well as the specific reactivity of residue G10, in both enzymatic (T1, Fig. S3A) and lead (Fig. S3B) probing experiments, suggest that this loop may adopt a unique structure. Interestingly, the sequence context (nt 9–12 and 44–46) allows the folding of the internal loop into an E-loop module, originally found in 5SrRNAs (33), with the residue G10 protruding from the structure. The E-loop structure is dependent on Mg2+. Thus, lead probing was repeated in the presence of decreasing concentrations of Mg2+ ions (Fig. S3B). Results indicate that the absence of Mg2+ ions alters significantly the cleavage profile of tRNAAsp7. Above all, the lead cleavage at positions 10 disappears and confirms the presence of an E-loop structure. Besides, lead cleavages decrease significantly at positions 13 and 14 and increase at positions 53 to 57 in the large internal loop.

Structure mapping experiments were performed on the tRNAAsp7 transcript alone or bound to the Alu (-23 + 54) sequence, using enzymatic probes (Fig. S3A). The data of these footprinting experiments support not only the intermolecular interaction but also the alternative fold. Indeed, 16 potential bp can form between tRNAAsp7 and the Alu sequence (Fig. 4C). In particular, disappearance of single stranded specific cleavages as well as appearance of double-stranded V1 cuts support the existence of at least two out of three blocks of interactions (1 and 3). In addition, most of the nucleotides protected by Alu (-23 + 54) binding are distributed around the E-loop platform. This suggests that this motif has a functional role in properly presenting the tRNAAsp7 residues that bind to the mRNA 3′ UTR. This was further confirmed by the progressive disappearance of the tRNAAsp7/Alu sequence duplex in the presence of decreasing concentrations of Mg2+ ions in the test (Fig. S3C).

Binding of tRNAAsp7 Has an Allosteric Effect on 3′ UTR Folding.

Long-range structural effects triggered by the binding of tRNAAsp7 on the mRNA were investigated by probing nt 120 to 250 of the 3′ UTR. Profiles, in the presence or absence of tRNAAsp7, were compared, revealing numerous changes in reactivity (Fig. 5A). First, the occurrence of numerous strong stops in the control experiment (without RNAse treatment) indicates that the 3′ UTR is structured and interrupts reverse transcription. This observation is supported by the fact that, in general, accessibilities for RNAses are rare in this region. Thus, any precise interpretation would be difficult. However, we clearly see that, when tRNAAsp7 is bound, the global pattern changes drastically, even 200 nt away from the binding site, indicating that most of the 3′ UTR, including the proximal poly(A) signal, reorganizes. We propose that tRNAAsp7 binding reshapes the 3′ UTR and, thereby, affects the recognition of the proximal poly(A) signal by the polyadenylation machinery.

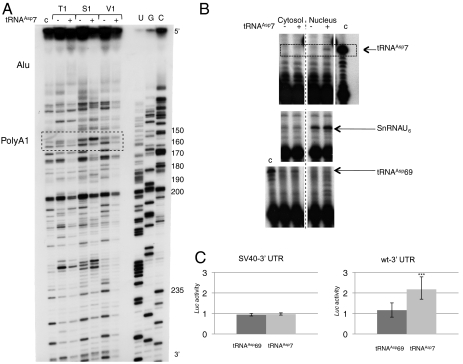

Fig. 5.

Functional study of tRNAAsp7. (A) Long-range rearrangement of AspRS 3′ UTR upon tRNAAsp7 binding. Autoradiogram of 12% denaturing gels displaying probing experiments performed on nt 100 to 250 of the 3′ UTR (in the context of the full-length AspRS mRNA), in the absence (−) or presence (+) of tRNAAsp7. Experiments were performed with RNases T1 (0.4 U), S1 (5.4 × 10-3 U) and V1 (8.3 × 10-3 U). Sequencing (C, G, U) (62) allowed numbering. The dashed box highlights the position of the proximal poly(A) signal. The Alu insertion, which binds tRNAAsp7, is also indicated about 100 nt upstream (top of the autoradiogram). (B) Nuclear localization of tRNAAsp7. RNA molecules were detected by premature chain termination primer extension, which allows elongation of radio-labeled specific primers by 10, 11 and 8 nt matching tRNAAsp69, tRNAAsp7 and SnRNAU6, respectively. Controls (c) were run on in vitro transcribed tRNAAsp7 and tRNAAsp69. Nuclear and cytosolic fractionation is identified by the presence of SnRNAU6 and tRNAAsp69, respectively. (C) Luciferase activity. Hepa 1–6 cells were cotransfected with pRL-CMV (SV40-3′ UTR) or pRL-CMV-WT-3′ UTR (WT-3′ UTR) and pSK-tRNAAsp69 or pSK-tRNAAsp7 and assayed for luciferase activity (deviation values of four independent transfections). Errors bars indicating the standard deviation are given. *** shows statistical significance (tRNAAsp7 versus tRNAAsp69) at P = 0.0006 (Welch’s t test).

tRNAAsp7 Resides Within the Nucleus and Stimulates Expression of an Alu-Containing mRNA.

Because endogenous tRNAAsp7 is detectable only by RT-PCR and sequencing, to distinguish it from the reference tRNAAsp, tRNAAsp7 was expressed in culture cells. Two constructs were designed, one enclosing 700 bp both upstream and downstream of the tRNAAsp7 sequence, whereas the second was shortened and conserved only 40 bp upstream of the tRNAAsp7. Both constructs were transfected into HeLa cells and exhibited similar expression levels, suggesting that the internal A and B box sequences (see Fig. 2C) are sufficient for transcription by RNA polymerase III. Interestingly, cell fractionation experiments show that, whereas tRNAAsp69 is localized in the cytosol, tRNAAsp7 is found in the nucleus only (Fig. 5B), a prerequisite for this small ncRNA to participate in AspRS mRNA 3′ processing.

Overexpression of AspRS appeared to be toxic in primate cells. These observations support the idea that the concentration of AspRS is tightly regulated and that any increase (or decrease) in the level of this housekeeping enzyme is poisonous for the cell, a situation we faced already with yeast AspRS (34, 35). Therefore, these experiments could not be performed directly on the human AspRS mRNA, and we decided to use a luciferase reporter gene strategy. Likewise, overexpression of tRNAAsp7 was toxic for primate cells due to interference with the endogenous AspRS expression and/or possible off-target effects (recognition of irrelevant Alu sequences). Therefore mouse Hepa 1–6 cell appeared as an interesting alternative model. In addition, no tRNAAsp7 homolog is found in the mouse genome, preventing any interference with the reporter system expression.

The Luc reporter gene fused to the wt 3′ UTR (-23 + 682) of AspRS mRNA (Fig. 1) was cotransfected with plasmids encoding tRNAAsp69 or tRNAAsp7 in Hepa 1–6 cells (at low concentration to mimic HeLa conditions). Fig. 5C shows that Luc activity is increased about 2-fold in the presence of tRNAAsp7, compared to the control experiment with tRNAAsp69. This effect is dependent on the presence of the AspRS 3′ UTR, because no stimulatory effect was observed when the SV40 UTR is fused to the Luc reporter gene (Fig. 5C). This result indicates that binding of tRNAAsp7 to the Alu insertion in AspRS mRNA 3′ UTR supports protein expression.

Discussion

A Previously Undescribed Model: Alternative Polyadenylation Is Driven by an ncRNA.

Most mRNA regulatory elements are found within their mRNA untranslated regions. Whereas the 5′ UTR is mainly involved in controlling mRNA translation (36), the 3′ UTR regulates multiple aspects of mRNA metabolism. In particular, 3′ end processing, or polyadenylation is necessary to promote nuclear export of mRNA, to protect mRNA from degradation and to enhance translation (37). This process involves two steps during which pre-mRNA is first cleaved at a specific site and then adenine residues are added (29). More than 50% of mammalian mRNAs are subjected to polyadenylation at multiple poly(A) sites, thus generating distinct mRNA isoforms with 3′ UTRs of variable lengths. Previous studies concluded that alternative polyadenylation shows a higher frequency in tissue-specific regulation than other forms of alternative events (23). However, little is known about how selection is made between different cleavage sites (38). In the proposed model, we considered tRNAAsp7 as a putative effector directing alternative polyadenylation of the human AspRS mRNA. Furthermore, this scenario is supported by previous studies showing that all known cases of aaRS regulation use cognate tRNA or tRNA mimics (39).

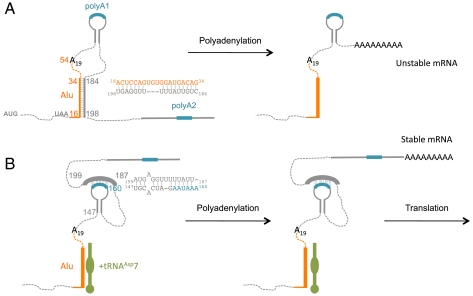

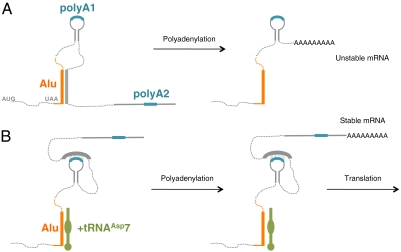

Our findings are consistent with a mechanism for RNA-mediated alternative polyadenylation wherein the binding of a short ncRNA switches the availability of two poly(A) signals (Fig. 6). When the ncRNA (tRNAAsp7) concentration is low (or absent, as is the case in mouse cells), the newly transcribed mRNA can adopt two alternative structures that expose the proximal or the distal poly(A) signal (Fig. 6). The occurrence of a short 3′ UTR destabilizes the mRNA (Fig. 6A) and reduces AspRS expression, whereas 3′ end processing at the distal poly(A) signal (Fig. 6B) produces a long and stable 3′ UTR: a suitable template for translation. Conversely, when the ncRNA concentration is high, its binding to the primate-specific Alu insertion stabilizes allosteric changes in the 3′ UTR folding, burying nucleotides at the proximal poly(A) site and exposing the distal one (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Model for the regulation of AspRS expression via alternative polyadenylation of its mRNA 3′ UTR. (A) Processing of the 3′ UTR in absence of tRNAAsp7. Nts 16–34 within the Alu insertion hybridizes with nt 184–198 of the 3′ UTR, forming a 16 bp duplex. This interaction allows the exposure of the proximal poly(A) signal for early maturation. The resulting short 3′ UTR destabilizes the mRNA and prevents protein expression. (B) Processing of the 3′ UTR in presence of tRNAAsp7. tRNAAsp7 binds cotranscriptionally, nts 19–37 (23-bp duplex) in the Alu insertion, therefore allowing nts 187–199 to fold back on the proximal poly(A) signal (12 bp with nts 147–160) and hide it from the polyadenylation machinery. Maturation takes place at the distal poly(A) signal and produces a stable mRNA for efficient translation. Primate-specific Alu insertion is indicated in orange, both poly(A) signals (1 and 2) are blue, and tRNAAsp7 is represented in green.

This model is supported by the results of the Alu sequence mutagenesis and deletion, which lead to similar increases in mRNA stability than the removal of the proximal poly(A) signal (Fig. 1). Indeed, changes in the Alu sequence prevent the predicted intramolecular interaction with nt 184–198 (16 potential bp), which in turn can cover the proximal poly(A) signal (12 potential bp) (Fig. 6). Moreover, the restricted localization of tRNAAsp7 in the nuclear compartment is in agreement with this model, because it is accepted that pre-mRNA 3′ end processing occurs cotranscriptionally (40).

However, because our results were derived from a reporter system, we cannot exclude that additional mechanisms might be involved in the endogenous mRNA regulation, such as nuclear export, specific localization, degradation, or translational control.

An Alternative Fold of a tRNA-Derived Sequence Is Functional.

tRNA isodecoders are defined as tRNA molecules sharing the same anticodon but diverging elsewhere in their sequence (up to 274 different tRNA species are produced from 446 genes in human) (31). Like all tRNA isodecoders, the tRNAAsp7 sequence contains all the information necessary to maintain the classical cloverleaf structure (Fig. S2). It also displays the functional residues identified as aminoacylation determinants (41). However, tRNAAsp7 is not a substrate for aminoacylation; the main reason is that tRNAAsp7 adopts an alternative fold, deprived of the structural tRNA characteristics. This is consistent with its low tRNAscan score (32.3) compared to the reference tRNAAsp69 (72.9) (http://gtrnadb.ucsc.edu/). However, the alternative architecture is able to drive duplex formation with the AspRS mRNA 3′ UTR. The E-loop module present in the alternative fold plays a major role in stabilizing and in organizing the surrounding nucleotides to properly present the residues involved in the interaction. This study indicates that among eukaryotic tRNA isodecoders, some of them may direct posttranscriptional regulation. This possibility has already been anticipated by colleagues, who proposed that such functional relevance might explain the higher diversity in human tRNA isodecoders (42).

On the other hand, Alu insertions are widely spread over the human genome, and some of them could also be the target of tRNAAsp7. However, only AspRS mRNA carries this exact Alu insertion, and a specific scaffold certainly plays also a major role to permit optimal binding between both RNA molecules.

Toward a Function for a Primate-Specific Control of AspRS Expression: A Bundle of Evidence.

Alternative Polyadenylation Regulates AspRS.

The involvement of polyadenylation in eukaryotic gene control is becoming increasingly apparent, and our findings reveal that primate cells can use a tRNA-derived ncRNA to select alternative polyadenylation sites. Thus, it controls the stability of AspRS mRNA, which encodes a protein involved in translation, a key biochemical process. The major housekeeping function of aaRSs is indeed the attachment of amino acids to their cognate tRNAs during translation (28). As aminoacylation of tRNAs is an essential step in protein synthesis, this process proceeds with high specificity (41) and necessitates the tuned expression of tRNAs and aaRSs. Several aaRS regulation pathways have been studied, especially in bacteria (43). They are not conserved in evolution and differ from one aaRS to another, the only shared occurrence being the involvement of tRNA molecules or tRNA-like structures in the regulatory mechanism (39). In the present study, because tRNAAsp7 is a RNA polymerase III transcript, it could act as a sensor for tRNA transcription activity. This would link two essential processes, transcription and translation for overall coordination and homeostasis of the cell.

AaRSs Are Housekeeping, yet Moonlighting Proteins.

The relevance of the aminoacylation activities of aaRSs is obvious. However, it has recently become clear that some human aaRSs also possess tissue-specific functions, distinct from their role in translation. Indeed, different aaRSs define pathways such as angiogenesis [TyrRS, TrpRS, and AIMP1 (44–46)], the immune response [LysRS (47)], inflammation [GluProRS (48)], apoptosis [GlnRS (49)], but also neural development [AIMP1, GlyRS, AIMP2 (50–52)], and tumorogenesis [LeuRS (53)]. The switch between the canonical aminoacylation function of an aaRS and other alternative functions might rely on a different process: (i) the oligomerization state, (ii) the subcellular localization, or (iii) the differential expression of the protein. In our case, the existence of such a sophisticated regulatory mechanism controlling AspRS expression suggests that AspRS could also have additional functions involved in physiological processes.

Toward Tissue-Specific Expression of AspRS.

We propose that the present regulation mechanism would control AspRS tissue-specific accumulation in a primate-specific regulation pathway such as immunity, development, or tumorogenesis. In an attempt to identify such a putative pathway, we explored the large amount of microarray data available (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/GDSbrowser), searching for reliable results where only human AspRS mRNA would be overexpressed, compared to other aaRS mRNAs. We found four conditions where AspRS mRNA indeed accumulates (2-fold increase for AspRS mRNA compared to an average 2-fold reduction for the other aaRS mRNAs). Interestingly, the relevant microarray data concern different cell types, such as macrophages (GDS2036), B lymphocytes (GDS1807), breast cancer cells (GDS2758), and aortic smooth muscle cells (GDS3112). Yet these different tissues commonly overexpress AspRS mRNA when subjected to hypoxia. Hypoxia is a common condition present in many pathological situations, including inflamed tissues, malignant tumors, atherosclerotic plaques, chronic venous insufficiency, healing wounds, etc. For example, tumor-associated macrophages respond to hypoxia by up-regulating a broad array of genes, encoding proteins that promote the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of cells as well as angiogenesis (reviewed in refs. 54 and 55). These data support the necessity for the control of AspRS accumulation in hypoxic tissues.

Conclusion

The fraction of tRNA isodecoder genes increases all along the phylogenetic spectrum, and the expansion of Alu elements is characteristic of primate genomes. For primates, this opens large perspectives regarding function and structure for the most divergent sequences and reveals the reservoir of potential regulatory functions associated with tRNA- and Alu-derived sequences. Finally, the observation of this original posttranscriptional regulation mechanism points toward the discovery of a unique physiological pathway in which the contribution of AspRS is implicated besides its usual roles in translation.

Methods

RT-PCR.

The cDNA of tRNAAsp7 was amplified from HeLa cells total RNA using the OneStep RT-PCR (Qiagen) following the supplier’s protocol. Two gene specific primers were designed: 5′- GGACTCAAACTCCAGTC-3′ was first used for the reverse transcription and then together with 5′-TCCTTGTTAGTATAGTGGTGAG-3′ for the PCR reaction. The PCR products were cloned into pCR2.1 (PCR cloning kit from Qiagen) and sequenced.

3′ RLM-RACE PCR.

RLM-RACE by RLM-RACE PCR was run on three different human RNA samples (brain, breast, and muscle, Ambion). Reverse transcription and nested PCR reactions were performed using the first choice RLM-RACE kit (Ambion). PCRs were run with two primers complementary to the 3′ adaptor sequence and two nested primers hybridizing (i) at the end of the AspRS mRNA ORF sequence (5′-CCATGTTCCCTCGTGATCCCAAACG-3′) and (ii) directly downstream of the 19 A ending the Alu insertion in the mRNA 3′ UTR (5′-GTAACCTGCTAGTGCACAGGCTGTACTTTAGG-3′). PCR-amplified fragments were cloned into pDrive cloning vector (PCR cloning kit, Qiagen) and sequenced.

Preparation of Templates for in Vitro Transcription.

Human tRNAAsp transcripts were produced in vitro using the “transzyme” system (56). The transcripts were purified on native 12% PAGE and electroeluted (Schleicher and Schuell). DNA sequences encoding the full-length AspRS mRNA (2,215 nt including the ORF and both the 5′ and 3′ noncoding regions) as well as the 3′ UTR (-23 + 682) were PCR-amplified from a cDNA library (human muscle cDNA library, Invitrogen) and cloned between EcoRI and XhoI in pXJ41 downstream the T7 RNA polymerase promoter. Plasmids were linearized with XhoI before in vitro transcription (57). The reaction was stopped by acidic phenol/choloroforme extraction and transcripts were purified on a Sephagex G-25 column (NAP-5, GE Healthcare). Shorter 3′ UTR variants, 3′ UTR (-23 + 279) and Alu (-23 + 54), were cloned into pUC119 between BamHI and EcoRI restriction sites, downstream of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter. In the mutated version of the Alu insertion sequence  was replaced by

was replaced by  . Plasmids were linearized with EcoRI before in vitro transcription and transcripts were purified on a native 12% gel.

. Plasmids were linearized with EcoRI before in vitro transcription and transcripts were purified on a native 12% gel.

Aspartylation Assays.

In vitro aspartylation of human tRNAAsp transcripts was performed as described previously (58).

Band-Shift Assays.

32P 3′-labeled tRNAAsp7 (1,000 cpm/μL) (59) was incubated for 20 min at 37 °C in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 40 ng/μL 5SRNA with increasing concentrations of mRNA variants (30 to 8,000 nM). Bound and unbound RNA molecules were separated either on a 1% agarose gel, with Tris borate EDTA buffer containing 1 mM MgCl2 for 2 h at 50 V [full-length mRNA and 3′ UTR (-23 + 682)] or on a 6% acryl/bisacrylamide (37.5/1) gel 1 × TBE, for 90 min at 140 V [3′ UTR (-23 + 279) and Alu (-23 + 54)].

Structural Mapping Procedures.

Structural mappings of tRNAAsp transcripts and AspRS mRNA were done using chemical and enzymatic probes (Pb2+ and T1, S1 and V1 nucleases). RNA digestions were performed in 25 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM NaCl, whereas lead-induced cleavages were performed in 50 mM Tris acetate pH 7.5, 5 mM Mg acetate, 50 mM KOH acetate, and 1 mM lead acetate (60).

tRNA transcripts were 32P 5′-labeled (61) and purified on NAP5. This molecule was used in (i) direct probing experiments and (ii) in RNA/RNA footprinting experiments where tRNAAsp7 was preincubated in the presence of 20 pmoles of Alu (-23 + 54) transcript prior modifications.

Longer transcripts such as 3′ UTR (-23 + 682) or full-length mRNA were first incubated with structural probes, and cleavage products were then revealed by reverse transcription as described elsewhere (62). Radio-labeled fragments were separated on a denaturing (8 M urea) 12% PAGE.

Constructs for Mammalian Cell Transfection.

Wild-type 3′ UTR (-23 + 682) of AspRS mRNA and its variants were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA and inserted into pRL-CMV vector (Promega) between the XbaI and BamHI, downstream of the Rluc reporter gene, instead of the SV40 late polyadenylation signal. The cloned PCR fragment displays 50 nts below the distal polyadenylation signal, in order to conserve all the downstream elements necessary for an efficient maturation. Luciferase activity assays were achieved as indicated in the dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System manual (Promega). Statistical significances were assessed using the Welch’s t test. Probability P values were calculated using the GraphPad Prism software.

tRNAAsp genes were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA (previously digested with KpnI and SphI). The resulting 1,450-bp amplicon spans positions -700 to +700 relative to the tRNA sequence and incorporates all the upstream promoter and downstream regions required for efficient transcription and maturation. Regarding tRNAAsp7, another construct was designed with only 40 residues upstream from the tRNA sequence to remove potential upstream external transcriptional promoters. PCR products were then cloned into pSK(−), between the NotI and XhoI.

Cell Culture and Transfection.

HeLa (human epithelial) and Hepa 1–6 (mouse hepatocytes) cells were cultured in DMEM, supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, and 20 U/mL streptomycin and penicillin at 37 °C with 5% CO2. At 70–80% confluence, cells were transfected using DreamFect Gold reagent (OZBioscience). Hepa 1–6 were transfected using 100 ng pRL-CMV constructs, 50 ng pGL3 vector (transfection efficiency control), and 10 ng pSK-tRNA per well (24 well plate format). After 6 h incubation, the medium was changed, and the cells were further grown for 20 h. Mouse hepatocytes were chosen as a heterologous system because neither tRNAAsp7 nor the Alu insertion is present; hence the studied regulatory mechanism is absent in this cellular context.

Nucleus Purification.

HeLa cells were transfected with 6 μg DNA (tRNAAsp7) per 10-cm dish for 24 h. Nuclei were purified from the cytosolic fraction as described at http://www.lamondlab.com/f7nucleolarprotocol.htm. RNA was extracted from both nuclear and cytosolic fractions following the Tri-Reagent protocol (Sigma-Aldrich).

RACE-PAT.

cDNAs were synthesized from total RNA using a poly-T/adapter primer (gcgagcacagaattaatacgactcactatagg(t)12). The amount of mRNAs within the sample was determined by a standard PCR reaction in the presence of [α-32P] dCTP.

Northern Blotting.

Total cellular RNAs (15 μg) were run on 1% agarose gel and analyzed by Northern blotting using the NorthernMax kit (Ambion) and 32P labeled probes prepared with the NonaPrimer kit (Quantum Appligene).

Premature Chain Termination Primer Extension.

Different tRNAAsp entities were specifically detected by chain termination primer extension (63), using dideoxyoligonucleotides complementary to tRNAAsp69 (5′-GGGAATCGAACCCCGGTC-3′), tRNAAsp7 (5′-AGTCTCCACATGACAG-3′), and SnRNAU6 (5′-GCAGGGGCCATGCTAATC-TTCTCTGTAT-3′).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Pascale Romby, Catherine Schuster, and Eric Westhof for advice and stimulating discussions; Oliver Miller and Marie Messmer for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Université de Strasbourg, and “La Ligue Contre Le Cancer.”

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Commentary on page 16489.

See Author Summary on page 16497.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1103698108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Batzer MA, Deininger PL. Alu repeats and human genomic diversity. Nat Rev Genet. 2002;3:370–379. doi: 10.1038/nrg798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hasler J, Strub K. Alu elements as regulators of gene expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:5491–5497. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tomilin NV. Control of genes by mammalian retroposons. Int Rev Cytol. 1999;186:1–48. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brosius J. Genomes were forged by massive bombardments with retroelements and retrosequences. Genetica. 1999;107:209–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yakovchuk P, Goodrich JA, Kugel JF. B2 RNA and AluRNA repress transcription by disrupting contacts between RNA polymerase II and promoter DNA within assembled complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5569–5574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810738106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mariner PD, et al. Human Alu RNA is a modular transacting repressor of mRNA transcription during heat shock. Mol Cell. 2008;29:499–509. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landry JR, Medstrand P, Mager DL. Repetitive elements in the 5′ untranslated region of a human zinc-finger gene modulate transcription and translation efficiency. Genomics. 2001;76:110–116. doi: 10.1006/geno.2001.6604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Britten RJ. Almost all human genes resulted from ancient duplication. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:19027–19032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608796103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hasler J, Samuelsson T, Strub K. Useful ‘junk’: Alu RNAs in the human transcriptome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:1793–1800. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7084-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sobczak K, Krzyzosiak WJ. Structural determinants of BRCA1 translational regulation. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17349–17358. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109162200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spence J, Duggan BM, Eckhardt C, McClelland M, Mercola D. Messenger RNAs under differential translational control in Ki-ras-transformed cells. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4(1):47–60. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-04-0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vila MR, et al. Higher processing rates of Alu-containing sequences in kidney tumors and cell lines with overexpressed Alu-mRNAs. Oncol Rep. 2003;10:1903–1909. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuart JJ, Egry LA, Wong GH, Kaspar RL. The 3′ UTR of human MnSOD mRNA hybridizes to a small cytoplasmic RNA and inhibits gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;274:641–648. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krichevsky AM, Metzer E, Rosen H. Translational control of specific genes during differentiation of HL-60 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:14295–14305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.20.14295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vidal F, et al. Coordinated posttranscriptional control of gene expression by modular elements including Alu-like repetitive sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:208–212. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.1.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kramerov DA, Vassetzky NS. Short retroposons in eukaryotic genomes. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;247:165–221. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)47004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorek R, Ast G, Graur D. Alu-containing exons are alternatively spliced. Genome Res. 2002;12:1060–1067. doi: 10.1101/gr.229302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levanon D, Groner Y. Structure and regulated expression of mammalian RUNX genes. Oncogene. 2004;23:4211–4219. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin-Ling C, DeCerbo JN, Carmichael GG. Alu element-mediated gene silencing. EMBO J. 2008;27:1694–1705. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong C, Maquat LE. IncRNAs transactivate STAU1-mediated mRNA decay by duplexing with 3′ UTRs via Alu elements. Nature. 2011;470:284–290. doi: 10.1038/nature09701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.An HJ, Lee D, Lee KH, Bhak J. The association of Alu repeats with the generation of potential AU-rich elements (ARE) at 3′ untranslated regions. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy-Engel AM, et al. Human retroelements may introduce intragenic polyadenylation signals. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2005;110:365–371. doi: 10.1159/000084968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang ET, et al. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456:470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koscielny G, et al. ASTD: The alternative splicing and transcript diversity database. Genomics. 2009;93(3):213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tian B, Hu J, Zhang H, Lutz CS. A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:201–212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan J, Marr TG. Computational analysis of 3′-ends of ESTs shows four classes of alternative polyadenylation in human, mouse, and rat. Genome Res. 2005;15:369–375. doi: 10.1101/gr.3109605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lutz CS. Alternative polyadenylation: A twist on mRNA 3′ end formation. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:609–617. doi: 10.1021/cb800138w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ibba M, Francklyn C, Cusack S. The aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Georgetown, TX: Landes Biosciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Millevoi S, Vagner S. Molecular mechanisms of eukaryotic pre-mRNA 3′ end processing regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2757–2774. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salles FJ, Richards WG, Strickland S. Assaying the polyadenylation state of mRNAs. Methods. 1999;17:38–45. doi: 10.1006/meth.1998.0705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodenbour JM, Pan T. Diversity of tRNA genes in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6137–6146. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pütz J, Puglisi JD, Florentz C, Giegé R. Identity elements for specific aminoacylation of yeast tRNAAsp by cognate aspartyl-tRNA synthetase. Science. 1991;252:1696–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.2047878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leontis NB, Westhof E. The 5S rRNA loop E: Chemical probing and phylogenetic data versus crystal structure. RNA. 1998;4:1134–1153. doi: 10.1017/s1355838298980566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frugier M, Ryckelynck M, Giegé R. tRNA-balanced expression of a eukaryal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase by an mRNA-mediated pathway. EMBO Rep. 2005;6:860–865. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ryckelynck M, Paulus CA, Frugier M. Post-translational modifications guard yeast from misaspartylation. Biochemistry. 2008;47:12476–12482. doi: 10.1021/bi8009295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pickering BM, Willis AE. The implications of structured 5′ untranslated regions on translation and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore MJ, Proudfoot NJ. Pre-mRNA processing reaches back to transcription and ahead to translation. Cell. 2009;136:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muro EM, et al. Identification of gene 3′ ends by automated EST cluster analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20286–20290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807813105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryckelynck M, Giegé R, Frugier M. tRNAs and tRNA mimics as cornerstones of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase regulations. Biochimie. 2005;87:835–845. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Colgan DF, Manley JL. Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giegé R, Sissler M, Florentz C. Universal rules and idiosyncratic features in tRNA identity. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:5017–5035. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.22.5017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dittmar KA, Goodenbour JM, Pan T. Tissue-specific differences in human transfer RNA expression. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Putzer H, Grunberg-Manago M, Springer M. Bacterial aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: Genes and regulation of expression. In: Söll D, RajBhandary UL, editors. tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 1995. pp. 293–333. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. Highly differentiated motifs responsible for two cytokine activities of a split human tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23155–23159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Otani A, et al. A fragment of human TrpRS as a potent antagonist of ocular angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:178–183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012601899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Park SG, et al. Dose-dependent biphasic activity of tRNA synthetase-associating factor, p43, in angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45243–45248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yannay-Cohen N, et al. LysRS serves as a key signaling molecule in the immune response by regulating gene expression. Mol Cell. 2009;34:603–611. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukhopadhyay R, Jia J, Arif A, Ray PS, Fox PL. The GAIT system: A gatekeeper of inflammatory gene expression. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:324–331. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ko YG, et al. Glutamine-dependent antiapoptotic interaction of human glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase with apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6030–6036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006189200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu X, et al. MSC p43 required for axonal development in motor neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15944–15949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901872106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antonellis A, et al. Glycyl tRNA synthetase mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D and distal spinal muscular atrophy type V. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:1293–1299. doi: 10.1086/375039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choi JW, Um JY, Kundu JK, Surh YJ, Kim S. Multidirectional tumor-suppressive activity of AIMP2/p38 and the enhanced susceptibility of AIMP2 heterozygous mice to carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:1638–1644. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin SH, et al. Implication of leucyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (LARS1) over-expression in growth and migration of lung cancer cells detected by siRNA targeted knock-down analysis. Exp Mol Med. 2008;40:229–236. doi: 10.3858/emm.2008.40.2.229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Lewis CE. Hypoxia regulates macrophage functions in inflammation. J Immunol. 2005;175:6257–6263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewis C, Murdoch C. Macrophage responses to hypoxia: Implications for tumor progression and anti-cancer therapies. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:627–635. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62038-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fechter P, Rudinger J, Giegé R, Théobald-Dietrich A. Ribozyme processed tRNA transcripts with unfriendly internal promoter for T7 RNA polymerase: Production and activity. FEBS Lett. 1998;436:99–103. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ryckelynck M, Giegé R, Frugier M. Yeast tRNAAsp charging accuracy is threatened by the N-terminal extension of aspartyl-tRNA synthetase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:9683–9690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211035200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bour T, et al. Plasmodial aspartyl-tRNA synthetases and peculiarities in Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:18893–18903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.015297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Frugier M, Moulinier L, Giegé R. A domain in the N-terminal extension of class IIb eukaryotic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases is important for tRNA binding. EMBO J. 2000;19:2371–2380. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bonnefond L, Florentz C, Giegé R, Rudinger-Thirion J. Decreased aminoacylation in pathology-related mutants of mitochondrial tRNATyr is associated with structural perturbations in tRNA architecture. RNA. 2008;14:641–648. doi: 10.1261/rna.938108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Frugier M, Giegé R. Yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase binds specifically its own mRNA. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:375–383. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00767-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Henriet S, et al. Cooperative and specific binding of Vif to the 5′ region of HIV-1 genomic RNA. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:55–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rederstorff M, et al. Ex vivo correction of selenoprotein N deficiency in rigid spine muscular dystrophy caused by a mutation in the selenocysteine codon. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:237–244. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]