Abstract

Purpose

Factors that influence hematology-oncology fellows' choice of academic medicine as a career are not well defined. We undertook a survey of hematology-oncology fellows training at cancer centers designated by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) to understand the factors fellows consider when making career decisions.

Methods

Program directors at all NCI and NCCN cancer centers were invited to participate in the study. For the purpose of analysis, fellows were grouped into three groups on the basis of interest in an academic career. Demographic data were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test and χ2 test, and nondemographic data were tested by using the multiscale bootstrap method.

Results

Twenty-eight of 56 eligible fellowship programs participated, and 236 fellows at participating institutions responded (62% response rate). Approximately 60% of fellows graduating from academic programs in the last 5 years chose academic career paths. Forty-nine percent of current fellows ranked an academic career as extremely important. Fellows choosing an academic career were more likely to have presented and published their research. Additional factors associated with choosing an academic career included factors related to mentorship, intellect, and practice type. Fellows selecting nonacademic careers prioritized lifestyle in their career decision.

Conclusion

Recruitment into academic medicine is essential for continued progress in the field. Our data suggest that fewer than half the current fellows training at academic centers believe a career in academic medicine is important. Efforts to improve retention in academics should include focusing on mentorship, research, and career development during fellowship training and improving the image of academic physicians.

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, there has been an increase in the number of hematology-oncology fellows trained at academic institutions—cancer centers designated by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN)—who complete their training and pursue nonacademic careers. This trend is not unique to North America1 or to medical oncology.2 Research to date has focused on the factors that influence the career decisions of medical students and residents, and it indicates that sex, mentorship, experience, the intellectual content of the domain, and the perceived fit with personality are important factors to be considered when making career decisions.3–17 Financial considerations such as escalating debt and lower future income potential have also been identified as reasons why medical school graduates do not consider academic careers.18–21 Graduates also appear to be placing greater emphasis on lifestyle and control over their work hours when making career decisions.9,16,22–25

Studies that focus on particular subspecialties are slowly emerging and are likely propelled forward by fellowship programs that are struggling to find strategies to improve their recruitment success. One such study26 looked specifically at residents' reasons for choosing or rejecting gastroenterology and found that a poor job market, less intellectual interest, and limited research opportunities were the most important dissuading factors. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists found that lack of clear objectives and adequate feedback in clerkship, sex biases, lack of early exposure in medical school, lifestyle, and liability were contributing to the declining popularity of the specialty among medical students.27 A study of rheumatology fellows28 identified clinical experience, mentorship, and early exposure to the field as influencing career choices.

As the number of applicants to internal medicine declines, the proportion of applicants to hematology-oncology programs may also decline.29 However, the number of internal medicine residents applying to hematology-oncology remains high, with approximately 700 applicants per year.30 The percentage of trainees entering academic careers is not known. In addition to their contribution to innovations in medical knowledge and patient care, academic physicians play a major role in the education of medical students, residents, and fellows and, thus, are responsible for shaping our future physicians. Given the important role academic physicians play in advancing the field of medicine, there is a need to ensure continued interest in academic careers. Currently, there are no published data regarding the proportion of hematology-oncology fellows entering academic versus nonacademic practice or the factors that fellows consider important when choosing between academic and nonacademic careers. If we can identify the variables that influence the career choices of hematology-oncology fellows, medical educators and policymakers could use this information to determine what barriers must be addressed to increase the interest and retention of those fellows in careers in academic medicine.

The objectives of this study were to examine the trends in the number of United States hematology-oncology fellows choosing academic versus nonacademic careers and to identify the factors that influence their career choices.

METHODS

Study Design

The study used a survey previously described by Horn et al.16 The research team—three medical oncologists, a division director, a program director, and a subspecialty fellow—made limited modifications to the survey instruments' demographic data to include questions pertaining to prior opportunities to participate in, present, and publish research. In addition, all fellows were asked to rank, on a scale of 1 to 5, the importance of a future academic career with 1 being “extremely unimportant” to 5 being “extremely important.” There were a total of 20 demographic and 43 nondemographic variables. Before administering the survey, it was pilot-tested on a random sample of five junior faculty in hematology-oncology to ensure that the instrument was coherent. Before survey distribution, this study was approved by the Vanderbilt University institutional review board.

All hematology-oncology program directors at NCI- and/or NCCN-designated cancer centers were contacted via e-mail and invited to collaborate. Program directors were asked to provide data on the number of fellows completing their fellowship program in the last 5 years and the number of fellows pursuing academic, nonacademic, and industry employment per year. Surveys for fellows were mailed directly to the offices of program directors and mailed back to the investigators on completion. The surveys were completed anonymously. Data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet by investigators and imported into SPSS (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Statistical Analysis

For purposes of analysis, fellows were grouped into three groups: group 1, low interest in academic career (ranked importance of academic career as “extremely unimportant” or “unimportant”); group 2, moderate interest in an academic career (ranked importance of academic career as “important”); and group 3, high interest in an academic career (ranked importance of an academic career as “very important” or “extremely important”). For demographic characteristics, age differences were tested with the Kruskal-Wallis test; all other differences were tested with the χ2 test.

To assist in finding similarities between the 43 career questions, questions were sorted into hierarchical clusters which were then tested by using a multiscale bootstrap method with 5,000 bootstrap resamples.31,32 The statistically determined clusters were compared with the scientifically derived clusters to determine whether the clustering technique had found meaningful clusters.

Next, each question was added as two indicator variables to a proportional odds model with academic career interest as the ordered three-category outcome. The proportional odds model also adjusted for age, sex, fellowship year, current educational debt, and whether the respondent had published research. The P values from a likelihood ratio test that compared the model with two indicator variables for response to the career question with the model that had no variables for response to the career question were recorded. These 43 P values were then adjusted by using the Benjamini-Yekutieli adjustment for multiple comparisons with a cutoff of 0.2 to determine which of the 43 career questions were related to career choice after adjusting for the demographic variables already listed.33 Because some categories had few respondents, all summaries and analyses, except for the clustering step, were done on collapsed responses to questions. The 43 questions were ranked within the three groups of respondents by average importance, and the top 10 in each group are reported. All summaries and analyses were produced by using R version 2.8 software (http://www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Twenty-eight of 56 eligible fellowship programs agreed to participate, and 236 fellows at participating institutions responded (62% response rate). Approximately 40% of fellows graduating from academic institutions in the last 5 years have entered nonacademic career paths (Table 1). Of fellows surveyed, 30% ranked an academic career as “unimportant” or “extremely unimportant,” 21% ranked an academic career as “important,” and 49% ranked an academic career as “very important” or “extremely important.”

Table 1.

Trends in Fellows Graduating and Entering Practice

| Year | Percent of Fellows Entering Practice |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic | Nonacademic | Industry | |

| 2008 | 59 | 38 | 3 |

| 2007 | 59 | 40 | 1 |

| 2006 | 52 | 47 | 1 |

| 2005 | 51 | 45 | 4 |

| 2004 | 54 | 44 | 2 |

The median age of fellows was 32 years (Table 2), 37% had more than $100,000 in debt, and 27% had a second postgraduate degree. Ninety-eight percent had participated in a research project: 50% in clinical research, 17% basic science research, 29% in both clinical and basic science research, and 3% in other research. Although not significant, respondents with a low interest in an academic career were more likely to be training at NCCN-designated cancer centers than at NCI-designated cancer centers. There was no difference between groups with regard to year of fellowship or current level of debt. Fellows with high interest in academic careers were more likely to be female (69% v 56%; P=.095), to have an additional graduate degree (84% v 64%; P=.015), and to have participated in basic research (23% v 11%; P=.051). Fellows with high interest in academic careers were also more likely to have presented research at a scientific meeting (78% v 53%; P=.002) or to have published their research (78% v 41%; P < .001) than those with low interest. Similarly, fellows with more publications were more likely to have a high interest in an academic career (P < .001).

Table 2.

Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | Overall (N=236) |

Low Importance (group 1) (n=70) |

Important (group 2) (n=50) |

High Importance (group 3) (n=116) |

P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Age, years | .250 | ||||||||

| Median | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 | |||||

| Range | 28-44 | 28-41 | 28-40 | 28-44 | |||||

| Sex | .095 | ||||||||

| Male | 58 | 138 | 69 | 48 | 50 | 25 | 56 | 65 | |

| Female | 42 | 98 | 31 | 22 | 50 | 25 | 44 | 51 | |

| Marital status | .638 | ||||||||

| Married/engaged | 74 | 174 | 78 | 54 | 78 | 39 | 70 | 81 | |

| Single | 25 | 60 | 21 | 15 | 22 | 11 | 29 | 34 | |

| Divorced | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Postgraduate year of fellowship | .191 | ||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| 4 | 33 | 77 | 26 | 18 | 39 | 19 | 34 | 40 | |

| 5 | 31 | 74 | 41 | 29 | 27 | 13 | 28 | 32 | |

| 6 | 29 | 69 | 30 | 21 | 33 | 16 | 28 | 32 | |

| 7 | 6 | 13 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 10 | |

| Current level of debt, $ | .217 | ||||||||

| ≤ 50,000 | 47 | 110 | 44 | 31 | 46 | 23 | 48 | 56 | |

| 50, 001-100,000 | 16 | 38 | 24 | 17 | 16 | 8 | 11 | 13 | |

| > 100,000 | 37 | 88 | 31 | 22 | 38 | 19 | 41 | 47 | |

| Additional postgraduate degrees | .015 | ||||||||

| Master's | 11 | 26 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 16 | |

| Doctor of Philosophy | 11 | 27 | 1 | 1 | 10 | 5 | 18 | 21 | |

| Other | 5 | 11 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| None | 73 | 172 | 84 | 59 | 78 | 39 | 64 | 74 | |

| Participated in research | .051 | ||||||||

| Basic science | 17 | 40 | 11 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 23 | 27 | |

| Clinical | 50 | 117 | 61 | 43 | 54 | 27 | 41 | 47 | |

| Both | 29 | 69 | 20 | 14 | 34 | 17 | 33 | 38 | |

| Other | 3 | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | |

| None | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Research during | |||||||||

| Undergraduate school | 25 | 58 | 24 | 17 | 20 | 10 | 27 | 31 | .652 |

| Medical school | 32 | 76 | 20 | 14 | 36 | 18 | 38 | 44 | .033 |

| Graduate school | 18 | 43 | 10 | 7 | 12 | 6 | 26 | 30 | .011 |

| Residency | 51 | 121 | 43 | 30 | 58 | 29 | 53 | 62 | .211 |

| Fellowship | 56 | 132 | 54 | 38 | 56 | 28 | 57 | 66 | .941 |

| Research was | |||||||||

| Published | 64 | 150 | 41 | 29 | 62 | 78 | < .001 | ||

| Presented | 67 | 158 | 53 | 37 | 62 | 78 | .002 | ||

| No. of publications | < .001 | ||||||||

| 0 | 41 | 24 | 6 | ||||||

| 1-3 | 47 | 56 | 56 | ||||||

| 4-9 | 10 | 16 | 30 | ||||||

| > 10 | 1 | 4 | 8 | ||||||

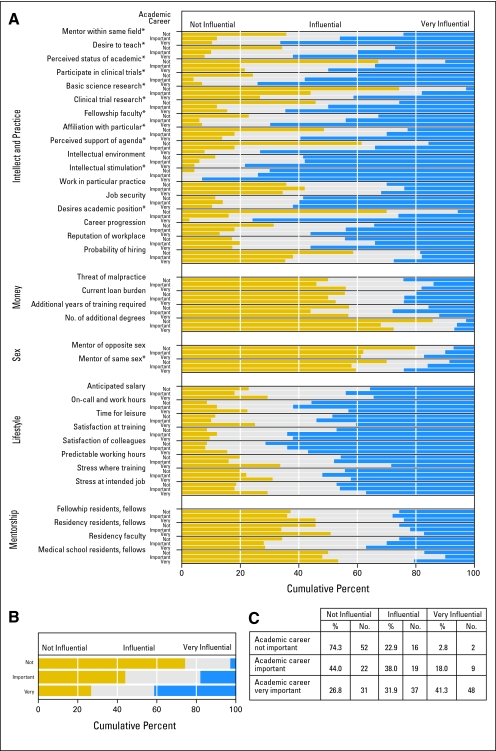

The relationships between interest in an academic career and the influence the survey questions had on career selection are shown in Figure 1. The questions are grouped according to the hierarchical clustering results. Note that questions within a cluster have similar relationships to an interest in an academic career. For example, the eight questions pertaining to lifestyle—anticipated salary, on-call and work hours, time for leisure, satisfaction at training, satisfaction of colleagues, predictable work hours, stress where training, and stress at intended job—tend to be influential to respondents, regardless of their interest in an academic career. In contrast, threat of malpractice, current loan burden, additional years of training required, and number of additional degrees tend to be not influential for respondents, regardless of interest in an academic career.

Fig 1.

(A, B) Relationship between career and survey questions. The relationship between the response to each survey question and to “How important is an academic career to you?” are summarized in the table (C). The percents in each row sum to 100%. For example, of the respondents who indicated that an academic career was not important, 74.3% also responded that basic science research was not influential to them, 22.9% responded it was influential, and 2.8% responded it was very influential. The top line of the table (C) is represented in the top line of the smaller graph (B). Looking down the columns of the large graph (A), we see the trend that the more important an academic career is to someone, the more likely that person is to respond that basic science research is very important. This trend is visible in the graphic as a stair-step pattern. Had the percentages in each column been the same, there would not be a relationship between the response to the survey question and the question “How important is an academic career to you.” The graphic for a table with no relationship would not have this stair-step pattern but would still indicate how important each survey question is, regardless of interest in an academic career. The large graph (A) represents 35 of these tables; (*) indicates survey questions that were statistically related (in a proportional odds model) to interest in an academic career after accounting for differences in age, sex, fellowship year, current educational debt, and whether the respondent had published research.

The cluster at the top of Figure 1 appears different from the others; this cluster contains questions that tend to discriminate between respondents who indicated a career in academics was not important and those who thought it was very important. For example, “Influence of a mentor in the same field,” located at the top of Figure 1, displays a stair-step pattern indicating that respondents who were very interested in an academic career were more likely to respond that a mentor in the same field was very influential to their career decision. After adjusting for age, sex, fellowship year, current educational debt, and whether the respondent had published research in a proportional odds model, the “Influence of a mentor in the same field” was still significantly related to interest in an academic career. Additional factors associated with high interest in an academic career—desire to have an academic position, desire to teach, perceived status of an academic position, opportunity to participate in clinical trials, basic research being conducted in the field, clinical trials being conducted in the field, influence of a faculty member during fellowship, opportunity to be affiliated with a particular hospital or university, perceived support of their research agenda, intellectual stimulation, and influence of a mentor of the same sex—all influenced career decisions (significant factors are indicated with an asterisk in Fig 1).

Regardless of future career preferences (Table 3), fellows ranked future job satisfaction, experience with patients during training, consistence with personality, and intellectual environment in which they intend to practice among the top 10 reasons for choosing their future practice setting. Fellows with low or moderate interest in academic careers listed on-call and work hours as staff, satisfaction among faculty where they are training, and perceived time for leisure activities as staff among the top 10 factors influencing their career decisions. Fellows with moderate and high interest in academic careers included opportunity to participate in clinical trials among their top 10 reasons for choosing a practice type. Fellows with low interest in academic careers listed job security and practice independence to round off their top 10 reasons, and those with moderate interest listed city in which institution is located. Fellows with high interest in academic careers included desire to have an academic position, desire to teach, perceived support for research agenda, influence of a faculty member or members during fellowship, and influence of mentor within the same field among their top 10 reasons for considering an academic career.

Table 3.

Top 10 Reasons Associated With Career Choice

| Group 1: Low interest in academic career |

| 1. Intellectual stimulation |

| 2. Job satisfaction among staff where I intend to practice |

| 3. Job security |

| 4. Consistent with my personality |

| 5. On call and work hours as a staff physician |

| 6. Intellectual environment where I intend to practice |

| 7. Independence when practicing |

| 8. Time for leisure activities as staff |

| 9. Experience with patients during training |

| 10. Satisfaction among faculty/staff where I am training |

| Group 2: Moderate interest in academic career |

| 1. Job satisfaction among staff where I intend to practice |

| 2. Intellectual stimulation |

| 3. On call and work hours as a staff physician |

| 4. City in which institution is located |

| 5. Opportunity to participate in clinical trials |

| 6. Satisfaction among faculty/staff where I am training |

| 7. Time for leisure activities as staff |

| 8. Experience with patients during training |

| 9. Intellectual environment where I intend to practice |

| 10. Consistent with my personality |

| Group 3: High interest in academic career |

| 1. Job satisfaction among staff where I intend to practice |

| 2. Intellectual environment where I intend to practice |

| 3. Desire to have academic position |

| 4. Opportunity to participate in clinical trials |

| 5. Perceived support for my research agenda |

| 6. Influence of faculty members during fellowship |

| 7. Consistent with my personality |

| 8. Influence of mentor within the same field |

| 9. Desire to teach |

| 10. Experiences with patients during training |

DISCUSSION

Recruitment into academic medicine is a problem faced by all medical specialties. Our data suggest that approximately 40% of fellows training at academic institutions are choosing nonacademic careers. This value is likely higher for fellows training at nonacademic institutions, given that we chose to interview fellows at NCI- and/or NCCN-designated institutions—programs that are more likely to attract fellows seeking an academic appointment. It appears from our study that fewer than half the fellows currently training at academic centers believe a career in academic medicine is “very important” or “extremely important.” These results suggest that the number of fellows entering academic practice after training may decline in the next 5 years.

Approximately 90% of fellows with high interest in an academic career identified mentorship as an important positive influence on career decision, and faculty members or mentors within hematology-oncology programs is among their top 10 reasons for their career decision. By contrast, only 65% of fellows with “low” or “moderate interest” reported that faculty members or mentors within hematology- oncology programs influenced their decision. Mentorship has been found to have an impact on both choice of career and development and productivity in residents and medical students.16,34–37 This finding suggests that training programs need to continuously evaluate mentoring activities and consider a more formal structure for assessing mentorship for trainees. Our data also indicate that trainees who either publish or present their data in a formal manner are more likely to pursue an academic career. Possibly the personal recognition that comes with a published paper or a presentation at a research meeting may inspire an individual to pursue academics where such activity is more commonplace. Similar trends were observed in a study of plastic surgery subspecialty fellows who were followed after graduation; those with publications, active participation in medical societies, and participation on editorial boards were more likely to remain in academic practice.38

Previously, level of debt has been shown to increase residents' stress and the likelihood of residents considering income potential when choosing a specialty.39 Somewhat paradoxically perhaps, in our survey, a higher percentage of fellows with a high interest in an academic career had existing debt loads of more than $100,000, suggesting that the perceived disparity in remuneration between academic and nonacademic physicians is not a major factor in decision making for hematology-oncology fellows. This may be partly due to the competitive loan repayment plans offered to physicians practicing within academic institutions. This is contradictory to a recent survey of gastroenterology fellows that found fellows choosing nonacademic careers were doing so because they believed such practice would be more likely to meet their perceived financial needs.40 Contrary to findings of other studies,39 our findings show that fellows likely to pursue an academic career are also more likely to be female and single. It is conceivable that such individuals may not be considering the future financial burdens that would occur with family obligations when making their career decisions.

Regardless of career choice, all fellows list “job satisfaction” and “consistency with personality” among the most important factors influencing their career choice. Job satisfaction for those choosing academic careers appears to be related to ability to teach, participate in research, and secure research support; those with low or moderate interest in academic careers prioritize lifestyle factors, including on-call and work hours, time for leisure activities, and independence while practicing. Interestingly, these same fellows identified satisfaction among faculty where they are training as influencing their decision not to pursue academic careers, which indicates the potential negative perceptions fellows may have of the lifestyle of role models practicing at academic centers.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to review the factors that have an impact on the career choices of hematology-oncology fellows training at academic institutions. Our data indicate a general decline in the number of hematology-oncology trainees who intend to pursue an academic career over the next few years. Given the anticipated workforce shortage,29 a decline in the number of trainees entering academic positions could further exacerbate this problem because there would be fewer individuals training future hematologists and oncologists. Efforts to address these factors need to be considered, including strategies to increase and improve the mentoring experience for current and future trainees, development of studies designed to better understand the current plight of the academic physician vis-à-vis work environment and lifestyle. Erikson et al29 surveyed hematology-oncology fellows in 2005 and found that 60% were concerned with balance between work and home life. Our data strongly suggest that fellows are greatly influenced by their perceptions of the professional lives of their trainers. Those who train in an environment that fosters good mentorship and provides excellent role models are much more likely to pursue employment in a similar work environment. By contrast, fellows who train in an environment of dissatisfaction, lack good mentorship, and lack research opportunities be they laboratory-based or otherwise are much less likely to seek employment in an academic setting. Other factors that may be at play include the blurring of the traditional line that separates an academic practice from a traditional community-based practice versus employment in industry or government. Less than a decade ago, there were sharp differences between university-based practices and private practices in terms of research opportunities and patient care opportunities. In recent years, these differences have become less pronounced. Lifestyle also has become an increasingly important factor when making a career choice. Academics was once viewed as a more leisurely albeit less financially rewarding work environment, whereas private practice was viewed as the exact opposite. These differences simply no longer exist. Thus, it is not enough to entice trainees into academic careers with the promise of discovery and lifestyle benefits. It will require an evidence-based approach that appeals to the individual's personality. It is also interesting that academia was once considered the domain of men, but our data suggest it is fast becoming the province of the single woman. What this means for the future of academic and community practice is unknown but it warrants continuous assessment.

Acknowledgment

We thank the institutions that agreed to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Supported in part by Grant No. UL1 RR024975 from the Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Science Award, National Comprehensive Cancer Network, National Institutes of Health.

Presented at the 46th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, Chicago, IL, June 4-8, 2010.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: David H. Johnson, miRNA Therapeutics (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: None Research Funding: None Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Leora Horn, Jill Gilbert, David H. Johnson

Financial support: David H. Johnson

Administrative support: David H. Johnson

Collection and assembly of data: Leora Horn

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Savill J. More in expectation than in hope: A new attitude to training in clinical academic medicine. BMJ. 2000;320:630–633. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7235.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Straus SE, Straus C, Tzanetos K. Career choice in academic medicine: Systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1222–1229. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00599.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hauer KE, Durning SJ, Kernan WN, et al. Factors associated with medical students' career choices regarding internal medicine. JAMA. 2008;300:1154–1164. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.10.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babbott D, Levey GS, Weaver SO, et al. Medical student attitudes about internal medicine: A study of U.S. medical school seniors in 1988. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114:16–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-1-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kassler WJ, Wartman SA, Silliman RA. Why medical students choose primary care careers. Acad Med. 1991;66:41–43. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199101000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marple RI, Pangaro L, Kroenke K. Third-year medical student attitudes toward internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2459–2464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMurray JE, Schwartz MD, Genero NP, et al. The attractiveness of internal medicine: A qualitative analysis of the experiences of female and male medical students—Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force on Career Choice in Internal Medicine. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:812–818. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-8-199310150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwartz RW, Haley JV, Williams C, et al. The controllable lifestyle factor and students' attitudes about specialty selection. Acad Med. 1990;65:207–210. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199003000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW. Influence of controllable lifestyle on recent trends in specialty choice by US medical students. JAMA. 2003;290:1173–1178. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldacre MJ, Turner G, Lambert TW. Variation by medical school in career choices of UK graduates of 1999 and 2000. Med Educ. 2004;38:249–258. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01763.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsdell JW. The timing of career decisions in internal medicine. J Med Educ. 1983;58:547–554. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198307000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lieu TA, Schroeder SA, Altman DF. Specialty choices at one medical school: Recent trends and analysis of predictive factors. Acad Med. 1989;64:622–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basco WT, Jr, Reigart JR. When do medical students identify career-influencing physician role models? Acad Med. 2001;76:380–382. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200104000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mayer KL, Perez RV, Ho HS. Factors affecting choice of surgical residency training program. J Surg Res. 2001;98:71–75. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Klaghofer R, Abel T, et al. Swiss residents' specialty choices: Impact of gender, personality traits, career motivation and life goals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:137. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horn L, Tzanetos K, Thorpe K, et al. Factors associated with the subspecialty choices of internal medicine residents in Canada. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:37. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-8-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawson SR, Hoban JD, Mazmanian PE. Understanding primary care residency choices: A test of selected variables in the Bland-Meurer model. Acad Med. 2004;79:S36–S39. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenthal MP, Marquette PA, Diamond JJ. Trends along the debt-income axis: Implications for medical students' selections of family practice careers. Acad Med. 1996;71:675–677. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199606000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doherty MJ, Schneider AT, Tirschwell DL. Will neurology residents with large student loan debts become academicians? Neurology. 2002;58:495–497. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thornton J, Esposto F. How important are economic factors in choice of medical specialty? Health Econ. 2003;12:67–73. doi: 10.1002/hec.682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newton DA, Grayson MS, Thompson LF. The variable influence of lifestyle and income on medical students' career specialty choices: Data from two U.S. medical schools, 1998-2004. Acad Med. 2005;80:809–814. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200509000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams GC, Saizow R, Ross L, et al. Motivation underlying career choice for internal medicine and surgery. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1705–1713. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00103-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeWitt DE, Curtis JR, Burke W. What influences career choices among graduates of a primary care training program? J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:257–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kassebaum DG, Szenas PL. Specialty preferences of 1993 medical school graduates. Acad Med. 1993;68:866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dodson TF, Webb AL. Why do residents leave general surgery?. The hidden problem in today's programs. Curr Surg. 2005;62:128–131. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benya RV. Why are internal medicine residents at university medical centers not pursuing fellowship training in gastroenterology?. A survey analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:777–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bienstock JL, Laube DW. The recruitment phoenix: Strategies for attracting medical students into obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1125–1127. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000162532.62399.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kolasinski SL, Bass AR, Kane-Wanger GF, et al. Subspecialty choice: Why did you become a rheumatologist? Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1546–1551. doi: 10.1002/art.23100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erikson C, Salsberg E, Forte G, et al. Future supply and demand for oncologists: Challenges to assuring access to oncology services. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:79–86. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0723601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Resident Matching Program. www.nrmp.org.

- 31.Shimodaira H. An approximately unbiased test of phylogenetic tree selection. Syst Biol. 2002;51:492–508. doi: 10.1080/10635150290069913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimodaira H. Approximately unbiased tests of regions using multistep-multiscale bootstrap resampling. Ann Stat. 2004;32:2616–2641. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. Quantitative trait loci analysis using the false discovery rate. Genetics. 2005;171:783–790. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.036699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martini CJ, Veloski JJ, Barzansky B, et al. Medical school and student characteristics that influence choosing a generalist career. JAMA. 1994;272:661–668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linzer M, Slavin T, Mutha S, et al. Admission, recruitment, and retention: Finding and keeping the generalist-oriented student—SGIM Task Force on Career Choice in Primary Care and Internal Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9(suppl 1):S14–S23. doi: 10.1007/BF02598114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harvey A, DesCôteaux JG, Banner S. Trends in disciplines selected by applicants in the Canadian resident matches, 1994-2004. CMAJ. 2005;172:737. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusiæ A. Mentoring in academic medicine: A systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296:1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grewal NS, Spoon DB, Kawamoto HK, et al. Predictive factors in identifying subspecialty fellowship applicants who will have academic practices. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1264–1271. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181858f8d. discussion 1272–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwong JC, Dhalla IA, Streiner DL, et al. Effects of rising tuition fees on medical school class composition and financial outlook. CMAJ. 2002;166:1023–1028. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adler DG, Hilden K, Wills JC, et al. What drives US gastroenterology fellows to pursue academic vs. non-academic careers?. Results of a national survey. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1220–1223. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]