Abstract

Poxviruses have been extensively used as a promising vehicle to efficiently deliver a variety of antigens in mammalian hosts to induce immune responses against infectious diseases and cancer. Using recombinant vaccinia virus (VV) and canarypox virus (ALVAC) expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) or multiple HIV-1 gene products, we studied the role of four cellular signaling pathways, the phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase (PI3K), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), in poxvirus-mediated foreign gene expression in mammalian cells. In nonpermissive infection (human monocytes), activation of PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK was observed both VV and ALVAC and blocking PI3K, p38 MAKP, and JNK pathways with their specific inhibitors significantly reduced viral and vaccine antigen gene expression. Whereas, blocking the ERK pathway had no significant effect. Among these cellular signaling pathways studied, PI3K was the most critical pathway involved in gene expression by VV- or ALVAC-infected monocytes. The important role of PI3K in poxvirus-mediated gene expression was further confirmed in mouse epidermal cells stably transfected with dominant-negative PI3K mutant, as poxvirus-mediated targeted gene expression was significantly decreased in these cells when compared with their parental cells. Signaling pathway activation was influenced gene expression at the mRNA level rather than virus binding. In permissive mammalian cells, however, VV DNA copies were also significantly decreased in the absence of normal function of PI3K pathway. Poxvirus-triggered activation of PI3K pathway could be completely abolished by atazanavir, a new generation of antiretroviral protease inhibitors (PIs). As a consequence, ALVAC-mediated EGFP or HIV-1 gag gene expression in infected primary human monocytes was significantly reduced in the presence of atazanavir. These findings implicate that antiretroviral therapy (ART), also known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), may negatively impact the efficacy of live poxvirus vector-based vaccines and should be carefully considered when administering such live vaccines to individuals on ART.

Keywords: poxvirus, monocyte, signaling pathway

Introduction

The poxvirus family (poxviridae) members including canarypox virus, vaccinia virus (VV) and its highly attenuated strains of modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) and New York vaccine strain (NYVAC) have, in recent years, received considerable attention for the development of vaccine vectors that can induce humoral and cellular immunity against virus infections as well as immunotherapy for cancer [1-5]. VV, the prototype and the best studied member of the family Poxviridae, was extensively used in the past as a live virus-based vaccine to globally eradicate smallpox caused by infection of variola virus, the most notorious member of Poxviridae family. Smallpox is one of the most dreaded diseases, which has claimed a greater number of human lives over span of recorded history than all other infectious diseases combined. Following a massive World Health Organization (WHO)-sponsored global vaccination, smallpox was officially declared eradication in 1980, and since then, routine smallpox vaccination ended worldwide. However, the events of 11 September 2001, and the subsequent anthrax attacks have raised concern about malevolent use of variola virus as a biological weapon by terrorists, as waning or nonexistent immunity has rendered most of the population vulnerable to this disease. In response to perceived threats of biological weapons use, many countries including the United States have increased the number of doses of lyophilized live VV-based smallpox vaccine in stockpile and restarted smallpox vaccination programs. The United States has also provided guidelines for smallpox vaccination of certain members of the population, including military personnel, public health care workers, and first responders [6].

Originating from the highly efficacious vaccines securing worldwide eradication of smallpox, VV has also been prove to be an attractive vector for the development of candidate recombinant vaccines against other infectious diseases. Concerns about the safety of VV have been addressed by development of vectors based on VV highly attenuated strains of MVA and NYVAC, and in particular utility of an alternative poxvirus vector ALVAC, a highly attenuated strain of canarypox virus. Several advantages of these vectors for vaccine development include: 1) the ability to insert large size and multiple genes for expression [5]; (2) viral DNA replication and viral assembly entirely occurs in the cytoplasm of infected vertebrate or invertebrate cells without entering the nucleus of the infected host cell, eliminating the risk of viral DNA integration into the cellular genome [1, 5]; (3) a good long term safety profile, although mild to moderate adverse reactions occur in some prototype VV-based vaccine recipients, with rare serious reactions occurring in persons with skin or immune disorders and occasionally in healthy individuals [7]; (4) with ability to infect a wide range of cells, poxvirus preferentially targets antigen-presenting cells (APCs) including peripheral blood monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs), implicating the viral capable of directly loading target antigen(s) on APCs in vivo by transient viral infections [8, 9]; (5) ALVAC and NYVAC vectors are classified as biosafety level 1 (BSL1) agents [10] and can be manufactured in large quantities, stored for an extended period of time, and delivered as lyophilized live-virus vaccine without requirement of cold chain [5]; and (6) ALVAC can elicit immune responses in the VV-exposed or smallpox-vaccinated people circumventing pre-existence of anti-VV immune responses. Poxvirus vectors including ALVAC, VV and its highly attenuated strains of MVA and NYVAC have shown in vivo to express a high level of foreign antigen proteins, which are immunogenic when delivered in animals and humans [11-18]. These live virus-based vectors have been extensively developed to express genes from rabies virus [19], canine distemper virus [20], feline leukemia virus [21], human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) [11, 22-31], simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) [32, 33], human cytomegalovirus (CMV) [34], Japanese encephalitis virus [35], melanoma [36], and prostate cancer [37]. ALVAC has also been used to develop and license several vaccines for companion animals and horses in USA and Europe [4].

The large genomic coding capacity of poxvirus family members enables them to express a unique collection of viral proteins that function as host range factors, which specifically target and manipulate host signaling pathways to establish optimal cellular conditions for viral gene expression and replication. VV has the ability to bind cells and activate cellular mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) including p38 MAPK [38], JNK [39], and ERK [40, 41], leading to permissive virus replication in a variety of diverse cell lines. Experimental studies using A31 cells (a clone derived from mouse Balb/c 3T3 cells) have demonstrated that VV triggers a sustained activation of MAPK/ERK1/2 and protein kinase A at an early stage of infection and whose activation are required for VV multiplication [41]. In fact, activation of multiple cellular signaling pathways including these MAPK pathways are one of the common features at the early infection stage of many viruses such as hepatitis viruses [42, 43], herpes virus [44, 45], HIV [46, 47], influenza virus [48], and coxsackievirus [40]. Thus, viruses manipulate multiple divergent cellular activities such as cell survival, migration, and immunity in order to regulate their own gene expression, lytic replication, DNA synthesis, and reactivation [49]. It is not surprising, therefore, that viruses target cellular signals as a means to regulate viral vector-mediated antigen protein expression.

Given the above, we hypothesize that cellular signaling pathways play a role in multiple steps of the viral life cycle, from viral gene expression to virus production, and that inhibition of certain signaling pathways would result in down-regulation of virus-mediated antigen expression or viral abortive infections. We and others have previously demonstrated that both VV and ALVAC show a strong bias towards human monocyte infection [8, 50, 51] which results in non-productive abortive infection [24, 52-55], and yet is associated with expression of appropriately engineered foreign genes at high levels [4]. This study was aimed at addressing the role of cellular signals in poxvirus-mediated foreign gene expression. We provide evidence that exposure of VV or ALVAC to mammalian cells triggers activation of multiple signaling pathways and some of these pathways play a significant role in the poxvirus-mediate foreign gene expression at mRNA and protein levels in unpermissive cells, and also at DNA synthesis level in permissive cells. We also demonstrate atazanavir, a new generation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease inhibitors, could completely abolished poxvirus-triggered activation of PI3K pathway, the most critical pathway among the four pathways examined in this study in the regulation of poxvirus-mediated foreign expression, consequently decrease poxvirus-mediated gene expression, implicating that ART, also known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), may negatively impact the efficacy of live poxvirus vector-based vaccines and should be carefully considered when administering such live vaccines to individuals on ART.

Experiment Procedures

Preparation of human peripheral monocytes and a dominant-negative PI3K cell line

Primary human peripheral monocytes were separated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) using multistep Percoll (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) gradient centrifugation, and then purified by depletion of contaminating B cells, T cells, NK cells, and granulocytes using antibody-conjugated magnetic beads in the Monocyte Negative Isolation Kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) as previously described [56-58]. Briefly, heparinized human peripheral blood was obtained from healthy blood donors for isolating PBMCs by centrifugation on Ficoll-Hypaque (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden). Isolated PBMCs (up to 50 × 106) were resuspended in 4 ml of complete RPMI 1640 medium [RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) plus 2 mM glutamine, 25 mM HEPES, and antibiotics] and then were gently layered on discontinuous gradients of Percoll in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) consisting of two layers of Percoll with 5 ml of 37% upper layer and 5 ml of 50% bottom layer. The tube was centrifuged 30 min at 1000 × g at 4°C with brake off. This led to formation of 3 cell layers: a layer containing dead material (if present) which did not enter the gradient; a layer near the bottom of the tube containing lymphocytes, granulocytes, red cells, and others, and the layer between the 37% and 50% Percoll layers containing monocytes. The layer containing monocytes was harvested for further purification by depletion of contaminating B cells, T cells, NK cells, and granulocytes using antibody-conjugated magnetic beads in the Monocyte Negative Isolation Kit (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) according to manufacture's recommendation. The resulting cell preparations contained more than 95% monocytes, and <0.1% T and B lymphocytes, as assessed by CD14, CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD19 staining and flow cytometric analysis (data not shown).

Mouse epidermal cell line, JB6 clone 41 (Cl 41), and the Cl 41-derived cell line stably transfected with dominant-negative PI3K mutant (Cl 4lΔp85) were a gift from Dr. Huang C, Nelson Institute of Environmental Medicine, New York University School of Medicine. The dominant-negative PI3K mutant Cl 41Δp85 cell line has been extensively used to study the role of PI3K in tumor promotion by different chemical carcinogens in different systems [59-64]. Cl 41 and Cl 41Δp85 cell lines were cultured in Eagle's minimum essential medium (EMEM, Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) supplemented with 5% FBS, 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, and 25 μg gentamicin/mL. The cultures were dissociated with trypsin and transferred to new 25-cm2 culture flasks (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA) every 3 to 5 days.

Virus preparation and virus infection in vitro

A recombinant VV expressing EGFP (EGFP-VV) and its parental VV strain of CR-19 were obtained from Dr. Jonathan W. Yewdell and Dr. Bernard Moss (NIH, Bethesda, MD). The EGFP-VV has a fusion protein inserted consisting of the nucleoprotein of influenza A/Puerto Rico/8/34 fused to chicken OVA (257-264) epitope, followed by a COOH-terminal fusion to EGFP from aequorea Victoria [65]. Parental ALVAC and two recombinant ALVAC viruses, vCP1540 (EGFP-expressing ALVAC) and vCP1452 (ALVAC expressing multiple HIV-1 genes) were obtained from Sanofi-Pasteur (Toronto, Canada). The vCP1452 is the most recent generation of canarypox-based HIV-1 vaccines, expressing the products of several HIV-1 genes, including gp120, expressed by a part of the Env gene of the HIV-1MN strain, and the anchoring transmembrane region of gp41 of the HIV-1LAI strain; the p55 polyprotein expressed by the Gag gene of the HIV-1LAI strain: a portion of the Pol gene sufficient to express protease activity from the HIV-1LAI strain in order to process the p55 Gag polyprotein; and genes expressing peptides from Pol and Nef known to be HLA-A2-restricted cytotoxic T-cell lymphocyte epitopes [66]. Two vaccinia virus-derived coding sequences, E3L and K3L, are also incorporated in the recombinant virus to improve RNA translation and the expression of HIV-1 gene products as well as to inhibit apoptosis and prolong protein expression in human cells.

VV produces at least two structurally distinct infectious forms of virions, intracellular mature virus (IMV) and extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) [67-69]. IMV represents the majority of infectious progeny and remains within the cytoplasm until cell lysis. EEV is released from the infected cells and processes an extra lipid envelope with at least 10 associated proteins which are absent from IMV [70, 71]. IMV and EEV were purified as described previously [70]. Briefly, VV was grown in primary chicken embryo fibroblasts (CEFs)(Charles River Laboratories, WI) with 0.01 plaque-forming units (pfu)/cell for 3 days in EMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine. IMV was then purified from dounce-homogenized infected cell extracts from which nuclei and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 4°C with 1,000 × g for 10 min. IMV in the clarified cell lysates was sonicated and then sedimented by ultracentrifugation at 35,000 × g, for 80 min at 4°C through a sucrose cushion (36%, wt/vol, in 10 mM Tris · HCl, pH 9). The IMV pellets obtained were further purified by sucrose velocity sedimentation as described [72]. EEV was purified from culture supernatant which was clarified by centrifugation at 1,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. EEV in the supernatant was pelleted by ultracentrifugation at 35,000 × g for 90 min at 4°C. Further steps of EEV purification were identical with IMV purification. Purified IMV and EEV were titrated in primary CEFs and stored at -80°C until use. ALVAC and recombinant ALVACs were also purified from cell culture supernatant and cell lysates, respectively, using the same protocol for VV IMV and EEV purification.

Primary human monocytes or mouse epidermal cell lines were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) 10 (10 viral particles per cell) with parental strain of VV, EGFP-VV, parental strain of ALVAC, vCP1450, or vCP1452. After 1 h adsorption at 37°C, free virus particles were removed by washing 2 times with PBS containing 2% FBS and cell pellets were resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium and cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for various time intervals.

Antibodies and flow cytometric analysis

The following anti-human monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) or polyclonal Abs conjugated with fluorochrome were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA): anti-CD1aFITC, anti-CD3APC, anti-CD4PerCP, anti-CD8PE, anti-CD14APC, anti-CD19PE, anti-CD56PE, and matched-isotype control Abs conjugated with FITC, PE, PerCP, or APC. Monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies including anti-Akt Ab, anti-phospho-Akt Ab, anti-p38 MAPK Ab, anti-phospho-p38 MAPK Ab, anti-ERK1/2 Ab, anti-phospho-ERK1/2 Ab, anti-JNK Ab, and anti-phospho-JNK Ab labeled or unlabeled with fluorochrome, were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). PI3K inhibitor LY294002, ERK inhibitor PD98059, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, and JNK inhibitor SP600215 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Cells, infected or uninfected with virus, were stained with specific fluorochrome-conjugated Abs in PBS/1% FBS/0.02% NaN3 buffer. After staining and washing, samples were subjected to flow cytometric analysis using a BD FACSCalibur (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) and the data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, San Carlos, CA). Appropriate isotype controls were used at the same protein concentration as the test Ab and control staining was performed during every flow cytometric analysis.

DNA/RNA extraction, plasmid preparation, and real-time PCR

DNA was extracted from virus-bound or infected cells by use of DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer's recommendation and extracted DNA samples were stored at -80°C until use. Total RNA was isolated from virus-infected or uninfected cells by use of RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's protocol. Prior to RNA elution from an RNeasy column, DNA removal was performed by on-column DNase digestion for 15 min at room temperature using RNase-Free Set (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). Total RNA was eluted with RNase-free water (Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY) and immediately stored at -80°C until use. Both DNA and total RNA samples were quantified spectrophotopically prior to PCR amplification.

Two plasmid constructs containing either partial VV F4L or ALVAC CNPV136 gene [8] were used to establish standard curves in each real-time PCR performance for quantitative analysis of viral DNA or cDNA copy number. Plasmid DNA concentrations were determined using a ND-1000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE). The number of construct copies in the plasmid solution was calculated, based on plasmid vector size (pCR2.1-TOPO, 3931 bp, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and insert size of 386 bp (VV) or 525 bp (ALVAC), respectively. A plasmid-based calibration curve was generated with 10-fold serial dilutions of plasmid containing the VV or ALVAC gene fragment sequence; to control pipetting steps, three 10-fold serial dilutions were prepared, and concentrations were checked by real-time PCR. For both VV and ALVAC, the quantification was linear over a range of 10 to 107 starting plasmid copy numbers, and the detection limit was ten copies per reaction. The human β-actin gene and mouse house-keeping gene glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used as internal controls for human and mouse DNA/RNA samples, respectively, for the normalization of the amount of viral DNA or cDNA in each sample.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) or RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed in a StepOnePlus Realtime PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Each sample and standard, including positive and negative controls, was set up in triplicate containing: 5 μl of 2 × Sybr Green Master Mix, 15 pmol each primer, and 50 ∼ 100 ng sample DNA or cDNA. PCR cycling conditions were: 95 °C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 30 sec, 55 °C for 30 sec, and 72 °C for 30 sec, and then a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The fluorescence intensity of SYBR green was measured automatically during the annealing steps. At the end of each run, a melting curve analysis was performed. Experiments were performed with undiluted and 10-fold diluted template DNA or cDNA in triplicate. The initial specimen DNA or cDNA was diluted in concentrations corresponding to 40,000 cell equivalents/10 μl with the number of cell equivalents calculated assuming that 6.6 ng of DNA or cDNA was equivalent to 1 × 103 cells. Initially, DNA or RNA samples were adjusted to the same concentrations and the same amount of template was used for both the virus and human β-actin or mouse GAPDH [73] primer sets. The PCR primers used: VV F4L.F389-409: 5′-CGTTGGAAAACGTGAGTCCGG-3′ and VV F4L.R528-509: 5′-GTGGATACATGACAGCGCCG-3′; ALVAC.F159461: 5′-CATCGCGATAACAGACAGTAT-3′ and ALVAC.R159571: 5′-CCAATCATCTTCAGCAGCGGC-3′; human β-actin.For: 5′-AGCCTCGCCTTTGCCGA-3′ and β-actin.Rev: 5′-CTGGTGCCTGGGGCG-3′; mouse GAPDH.For: 5′- AACGACCCCTTCATTGAC-3′ and GAPDH.Rev: 5′-TCCACGACATACTCAGCAC-3′ for amplifying VV, ALVAC, human house-keeping gene β-actin, and mouse house-keeping gene GAPDH, respectively.

ELISA quantification of HIV-1 p24 protein

Beckman Coulter HIV-1 p24 Antigen EIA kit (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA) or HIV-1 p24 ELISA Assay kit (XpressBio, Thurmont, MD) was used in strict accordance with manufacture's instructions to quantify HIV-1 Gag expression. The protocol for quantifying HIV-1 Gag expression in cell lysates prepared from vCP1452-infected or –uninfected (controls) human primary monocytes, mouse epidermal cell line Cl 41, and the Cl 41-derived cell line stably transfected with dominant-negative PI3K mutant (CI 41 Δp85) was modified from a previous report [74]. Briefly, cells were harvested and washed 2 times with ice-chilled PBS. After washing, cells (up to 1 × 106) were resuspended in 50 μl PBS, and then added with 50 μl of lysis buffer appended to the HIV-1 p24 ELISA kit. The mixture was placed on ice for 5 min to completely lyse the cells, and then centrifuged for 15 min at 1000 × g at 4°C to remove cellular debris. The supernatants were used as cell lysate samples. Each standard, negative control, cellular extracts from virus-infected or –uninfected cells were run in duplicate in the ELISA.

Western blot analysis

Primary human monocytes (1-2 × 106 cells) were exposed with VV or ALVAC at an MOI of 10 or medium alone and harvested at indicated time points. Cells were washed 2 times with ice-cold PBS, and then resuspended in 50 μl of 1 × cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling Technology). Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation and protein-containing supernatant was stored at −80°C until further use. Equal amounts (15 μl per lane) of the protein-containing supernatants were mixed with 5 μl of 4 × NuPAGE SDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and boiled for 5 min, and then subjected to NuPAGE Novex high-performance, precast gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked with blocking buffer (5% nonfat dry milk in TBST buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.6) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated at 4°C overnight with primary Abs specific for the phospho-p38 MAPK and total p38 MAPK, phospho-Akt and total Akt, phospho-ERK and total ERK, phospho-JNK and total JNK, respectively. After washing, targeted blots were visualized with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary Abs (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and an ECL detection system (Pierce, Rockford, IL). When inhibitors were used, cells were incubated for 15 min at 37°C in a 5% incubator before exposure to VV or ALVAC.

Statistical analysis

Data were compared using the Student t test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Poxvirus binding to primary human monocytes activates PI3K, p38 MAPK, ERK, and JNK

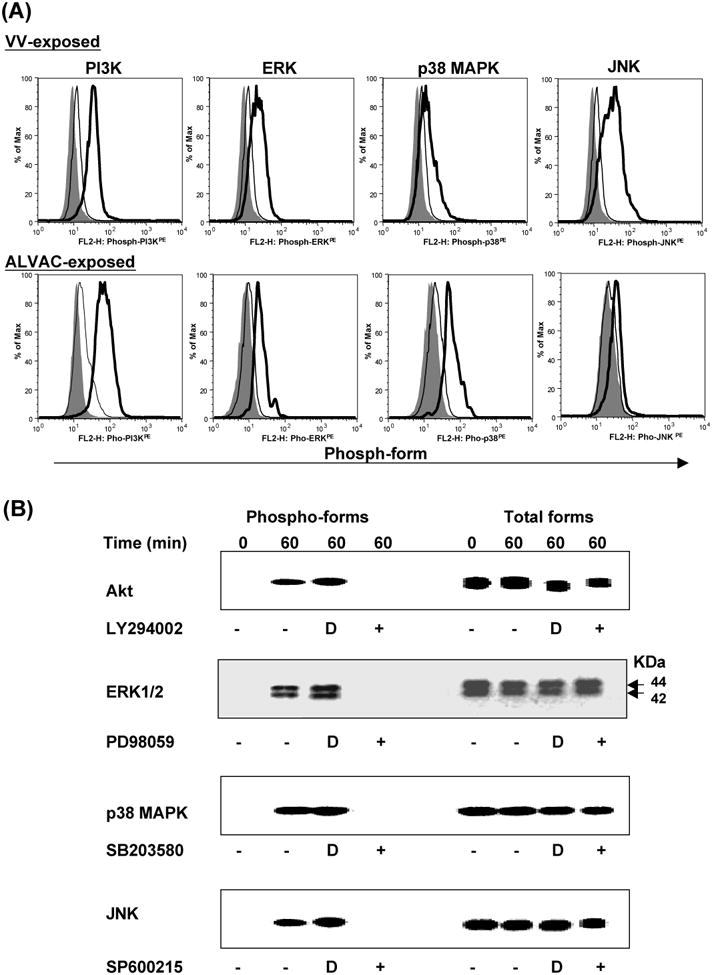

Activation of multiple signaling pathways is a common theme in response to virus infection. Poxvirus infection of mammalian cell lines can activate a variety of cellular signaling pathways including p38 MAPK, ERK, and JNK [38-41]. We previously demonstrated that VV and ALVAC showed a strong bias towards monocyte infection [8]. This observation prompted us to investigate whether poxvirus infection of primary human monocytes also activates multiple signaling pathways. Monocytes isolated from PBMCs were exposed to VV or ALVAC (both VV and ALVAC were purified from cell lysates of virus-infected CEFs) at 37°C up to 1 h, and then subject to flow cytometric analysis and Western blot to determine the activation of PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK by measuring their phosphorylation. We found that within 30 min of virus exposure, PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK were activated (Fig. 1A and 1B). Pretreatment of monocytes with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, ERK inhibitor PD98059, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, or JNK inhibitor SP600215 blocked phosphorylation of PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK or JNK, respectively, in response to virus exposure (Fig. 1B). Thus, the PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK signaling pathways are activated after exposure of VV or ALVAC to primary human monocytes obtained from healthy donors.

Figure 1.

Poxvirus exposure induces phosphorylation of PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK. Isolated primary human monocytes from PBMCs were exposed to VV or ALVAC at 10 MOI for up to 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were then subjected to intracellular staining and flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 1A) or Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B) with specific Abs for the phospho-PI3K, phospho-ERK, phospho-p38 MAPK, and phospho-JNK. In some cases, the monocytes were preincubated with signal transduction pathway inhibitors for 15 min before exposure to VV or ALVAC. (A) Gray histogram represents background without staining. Histogram in a thick line represents positive staining with specific Abs for the phospho-PI3K, phospho-ERK, phospho-p38 MAPK, or phospho-JNK, whereas histogram in a thin line represents negative background staining with isotype-matched control antibodies. (B) Western blot results of signaling pathway activation induced by ALVAC exposure: left side shows the detection of phosphorylated forms of Akt, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK, and right side shows the same plots probed for total Akt, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK proteins, respectively, to demonstrate equal loading of samples. Monocytes that had been incubated with DMSO alone were used as controls for the inhibitors, as signal transduction pathway inhibitors were all dissolved in DMSO. Results are representative of three independent experiments with different donors and similar Western blot results were also obtained from VV-exposed monocytes (data not shown). D, DMSO control.

Interestingly, we observed that intracellular mature virus (IMV) and extracellular enveloped virus (EEV) forms of VV exhibited similar kinetics of monocyte infection in terms of infection rate (data not shown). Furthermore, we also observed that ALVAC viruses purified from culture supernatants of ALVAC infected CEFs and exhibited similar kinetics of primary human monocyte infection as that of ALVACs from lysates of ALVAC-infected CEFs, (data not shown), suggesting that ALVAC may also exist in at least two infectious forms as VV does. In order to determine whether EEV and IMV forms of VV or ALVAC also exhibit similarity in the activation of cell signaling pathways in virus-exposed primary human monocytes, EEV was purified from the culture supernatant of CEFs infected with VV or ALVAC for 72 h. A side-by-side comparison of cell signaling pathway activation by IMV and EEV of VV or supernatant versus cell derived ALVAC was performed. Both IMV and EEV forms of VV and both viruses from supernatant versus cell derived ALVACs activated PI3K/Akt, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK pathways to a similar extent as determined by intensity of phosphorylation of all the four signaling pathways (data not shown).

Signaling pathways of PI3K/Akt, p38 MAPK, and JNK, but not ERK are required for poxvirus-mediated gene expression

Early studies have demonstrated that activation of MAPK plays a pivotal role for VV multiplication [40, 41]. VV infection provoked a sustained activation of ERK1/2, and subsequently exerted effects on viral thymidine kinase gene expression, viral DNA replication, and VV multiplication [41]. VV infection of human monocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells is abortive [53-55] and ALVAC undergoes a non-productive infection in human cells including monocytes [24, 52]. Thus, activation of these signaling pathways in VV- or ALVAC-exposed monocytes may only be required for regulation of viral or host gene expression, rather than for viral DNA replication. We then used primary human monocytes to investigate whether poxvirus-activated signaling pathways exerted an effect on virus-mediated gene expression. Monocytes pretreated with the PI3K inhibitor LY294002, ERK inhibitor PD98059, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, or JNK inhibitor SP600215 at 10 μM concentration which could completely block phosphorylation of PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK or JNK, respectively (Fig. 1A), were infected with EGFP-VV or EGFP-ALVAC (vCP1450) for various time intervals. Cells were directly analyzed for protein expression by flow cytometric analysis. Figure 2 (A and B) shows that blocking the ERK signaling pathway with PD98059 slightly reduced the percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes infected by EGFP-VV or vCP1450, which was not statistically significant as compared with the DMSO alone condition, whereas blocking either PI3K with LY294002, p38 MAPK with SB203580, or JNK with SP600215 significantly reduced the percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes. Blocking the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, however, gave the strongest inhibition of EGFP production. Thus, the signaling pathways of PI3K/Akt, p38 MAPK, and JNK, rather than ERK play a critical role in the induction of EGFP expression.

Figure 2.

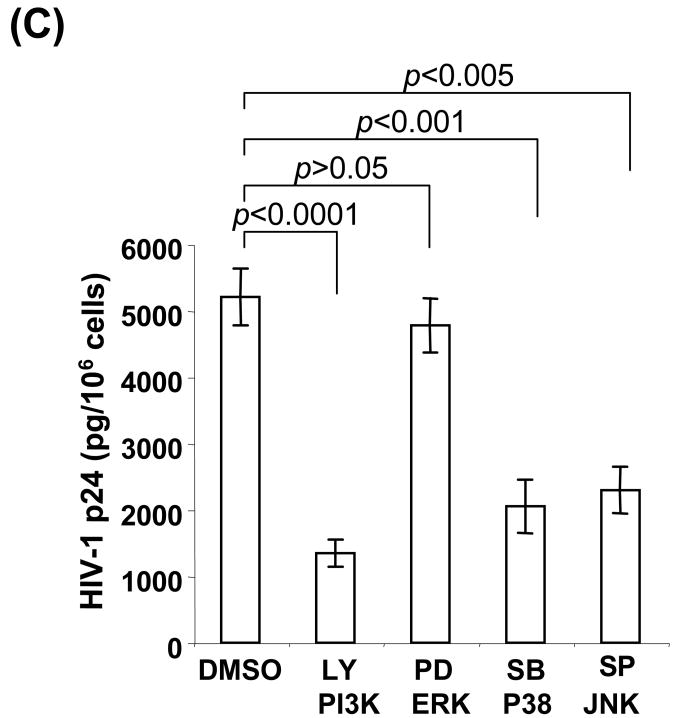

Cellular signaling pathways are involved in poxvirus-mediated protein expression. Primary human peripheral monocytes (up to 1 × 106 cells) were pretreated with specific inhibitors of LY294002, PD98059, SB203580, or SP600125 at 10 μM for 15 min at 37°C for blocking PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, or JNK, respectively. DMSO treatment was used as a negative control in every experiment. Cells were then infected with EGFP-VV, EGFP-ALVAC (vCP1540), or vCP1452 at an MOI of 10 for 8 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After infection, cells infected with EGFP-VV or vCP1540 were harvested for surface staining with anti-human CD14APC Ab, and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis to determine virus-mediated EGFP expression. Cells infected with vCP1452 were lysed for measuring HIV Gag p24 expression. (A) Cells were infected with EGFP-VV or vCP1540 and the infection was determined by analysis of EGFP-positive cells. The number in each dot plot shows the percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes in a representative experiment from five independent experiments with different donors. (B) Pooled data are mean ± SD of percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes, presenting five independent experiments with different donors. (C) HIV-1 p24 ELISA results from cells infected with vCP1452. Pooled data are mean ± SD of HIV-1 p24 levels, presenting five independent experiments with different donors. LY, LY294002; PD, PD98059; SB, SB203580; SP, SP600215.

We next evaluated whether these signaling pathways exerted similar effects on poxvirus-mediated antigen protein expression. To assess vaccine vector mediated antigen expression, monocytes were infected with an ALVAC-based HIV-1 vaccine, vCP1452, in the presence of individual signaling inhibitors. The infected cells were lysed and cellular extracts were prepared by removing nuclei and cell debris through centrifugation at 4°C with 1,000 × g for 15 min. The clarified cellular extracts were subject to ELISA to quantify the level of HIV-1 Gag expression. Figure 2C shows that induction of HIV-1 p24 (pg/106 cells) in vCP1452-infected monocytes in the presence or absence of inhibitors. Similar to EGFP induction, blocking the ERK signaling pathway with PD98059 slightly reduced HIV-1 Gag induction, which was not statistically significant as compared with the DMSO alone condition, whereas blocking either PI3K with LY294002, p38 MAPK with SB203580, or JNK with SP600215 significantly reduced the HIV-1 Gag expression. Blocking the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, however, gave the strongest inhibition of HIV-1 Gag expression. Taken together, the signaling pathways of PI3K/Akt, p38 MAPK, and PI3K, but not ERK play a critical role in poxvirus-mediated antigen protein expression.

A cell viability experiment was conducted to assess whether the observed reduction of targeted protein expression in virus-infected cells in the presence of inhibitors were caused by inhibitor chemical cytotoxicity. Cells infected with VV or ALVAC at an MOI of 10 in the presence of individual inhibitors at 10 μM for 6 h were stained with trypan blue solution for analyzing the ratio of dead cells vs viable cells. No decrease in cell viability compared to DMSO-treated cells was observed during VV or ALVAC infection, indicating that the effects of pathway inhibitors on regulation of poxvirus-mediated protein expression were not associated with inhibitor chemical cytotoxicity. In addition, all four inhibitors examined at 10 μM could completely block activation of their specific pathways in response to poxvirus infection (Fig. 1A), indicating that the most profound inhibition of poxvirus-medicated protein expression by PI3K inhibitor LY294002 at 10 μM was not due to better suppression of this pathway when compared to the other inhibitors used at the same concentration.

Downregulation of poxvirus-mediated protein expression by blocking cellular signaling pathways results from decrease of mRNA synthesis rather than viral binding

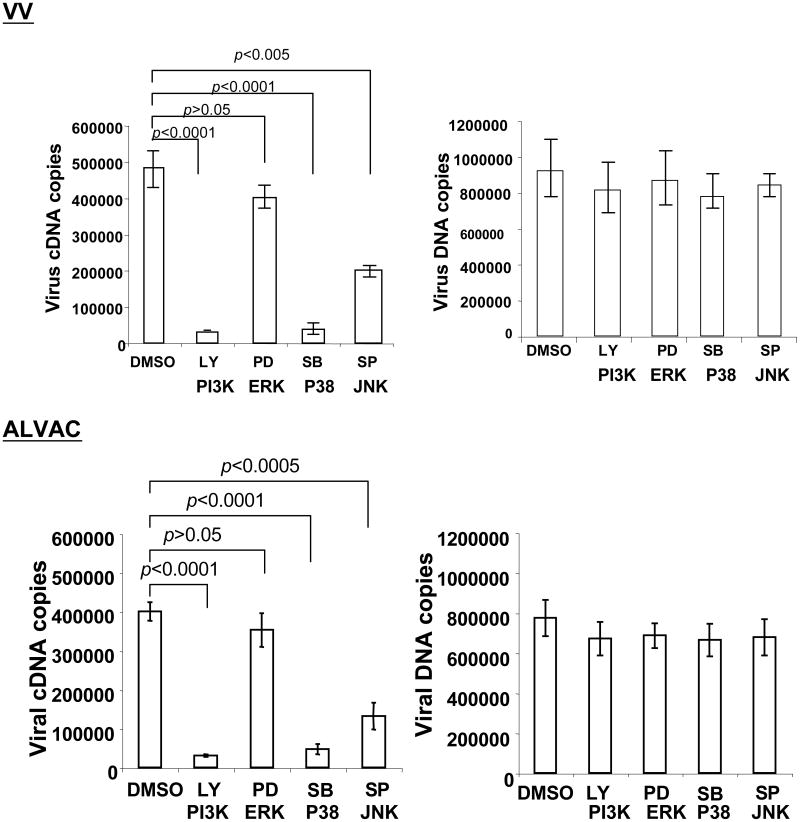

We then performed real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) and RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) to investigate whether the activation of these signaling pathways exerts an effect on viral binding or viral mRNA expression or both levels. Monocytes pretreated or untreated with PI3K inhibitor LY294002, ERK inhibitor PD98059, p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580, or JNK inhibitor SP600215 were exposed with VV or ALVAC for 1 h for viral binding analysis, or 6 h for viral mRNA analysis. Figure 3 shows the effective pattern of viral mRNA level by pathway inhibitors is similar to the regulation of protein expression. Blocking ERK signaling pathway with PD98059 slightly reduced cDNA copies of VV F4L or ALVAC CNPV136 gene, which was not statistically significant as compared with the DMSO alone condition, whereas blocking either PI3K with LY294002, p38 MAPK with SB203580, or JNK with SP600215 significantly reduced cDNA copies of VV F4L or ALVAC CNPV136 gene. Blocking the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, however, gave the strongest reduction of cDNA copies of VV F4L or ALVAC CNPV136 gene. In contrast, pretreatment of monocytes with these signaling pathway inhibitors had no effects on viral binding to monocytes as VV or ALVAC DNA copies were not significantly affected. The results also implicated that the effect of viral protein expression by signaling pathway inhibitors were not derived from nonspecific chemical toxicity of inhibitors to virus or cells, as both the viral DNA copies and house-keeping gene (data not shown) were not affected. Thus, inhibitors of signaling pathways exert an effect on viral mRNA level which is directly correlated with protein expression, not on viral binding.

Figure 3.

Cellular signaling pathways are involved in viral mRNA expression, not in poxvirus binding to monocytes. Primary human peripheral monocytes were pretreated with specific inhibitors of LY294002, PD98059, SB203580, or SP600125 at 10 μM for 15 min at 37°C for blocking PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, or JNK, respectively. DMSO treatment was used as a negative control in every experiment. Cells were then exposed to parental VV or parental ALVAC at an MOI of 10 for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells from each condition were washed twice with PBS to remove free virus particles. After washing, cells were equally split into two aliquots: one aliquot of cells was directly used for DNA extraction for realtime qPCR to determine viral DNA copies, and the other aliquot of cells in each condition was resuspended in 200 μl of complete RPMI 1640 medium and continuously cultured for an additional 6 h in the presence of individual inhibitors. After 6 h culture, cells were harvested for RNA extraction for realtime qRT-PCR to determine the viral mRNA level. Pooled data are mean ± SD of viral cDNA or DNA copies, presenting five independent experiments with different blood donors. LY, LY294002; PD, PD98059; SB, SB203580; SP, SP600215.

Cells transfected with dominant-negative PI3K mutant decrease expression of targeted proteins mediated by poxvirus infection

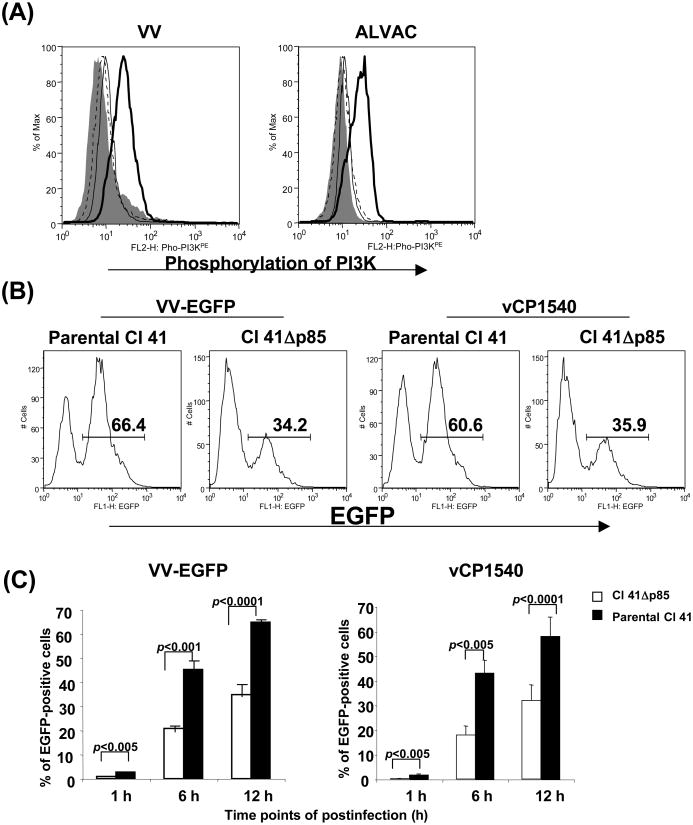

Mouse epidermal cell line, JB6 clone 41 (Cl 41), and the Cl 41-derived cell line stably transfected with dominant-negative PI3K mutant (Cl 41Δp85) were a gift from Dr. Huang C, Nelson Institute of Environmental Medicine, New York University School of Medicine. The dominant-negative PI3K mutant CI 41Δp85 cell line has been extensively used to study the role of PI3K in tumor promotion by different chemical carcinogens in different systems [59-64]. It was, therefore, of interest to use these cell lines to further confirm the involvement of PI3K pathway in poxvirus-mediated gene expression, as the PI3K pathway exerted the strongest effect on poxvirus-mediated gene expression in infected primary human monocytes. Exposure of parental Cl 41 cells with VV or ALVAC activated PI3K/Akt (Fig. 4A) signaling pathway and the activation was abolished 100% when the cells were pretreated with PI3K inhibitor LY294002 at 10 μM. Both VV and ALVAC efficiently infected parental Cl 41 cells and the mean infection rate from three experiments (the mean percentage of EGFP-positive Cl 41 cells) checked at 1h, 6h, and 12h post-infection were 1.8, 46, and 64% for VV infection, respectively, and 1.7, 43, and 58% for ALVAC infection, respectively (Fig. 4B, C). The Cl 41-derived dominant-negative PI3K mutant cell line (CI 41Δp85), however, significantly decreased the infection rate to both VV and ALVAC. In Cl 41Δp85 cells, the virus infection rate significantly decreased to 0.5, 22, and 36% for VV infection, and 0.2, 18, and 32% for ALVAC infection checked at 1h, 6h, and 12h of post-infection, respectively (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Cells transfected with a dominant-negative PI3K mutant decrease expression of targeted proteins mediated by poxvirus infection. Cl 41 cells and the Cl 41-derived cell line stably transfected with a dominant-negative PI3K mutant (Cl 41Δp85) were exposed with poxvirus, either parental VV, EGFP-VV, parental ALVAC, vCP1540, or vCP1452 at an MOI of 10 for 1 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After washing, cells were equally split into two aliquots: one aliquot of cells was directly used for intracellular staining with a specific Ab for the phospho-PI3K to measure activation of PI3K pathway, and the other aliquot of cells in each condition was resuspended in complete RPMI 1640 medium and then continuously cultured for an additional 1 to 12 h. Cells were then harvested at the checked points of 1, 6, and 12h postinfection for detecting EGFP expression (VV-EGFP or vCP1540 infection) by flow cytometric analysis (Fig. 4B and 4C), or detecting HIV-1 p24 expression (vCP1452 infection) by ELISA (Fig. 4D) to determine protein expression, or RNA and DNA extraction for real-time qPCR or qRT-PCR to determine the viral mRNA level and DNA copies (Fig. 4E). Fig. 4A shows a representative experiment of VV- or ALVAC-induced PI3K pathway activation. Gray histogram represents background without staining. Histogram in a thick line represents positive staining with a specific Ab for the phospho-PI3K, whereas histogram in a thin line represents negative background staining with an isotype-matched control Ab and histogram in a dotted line represents PI3K staining from the cells pre-treated with PI3K inhibitor LY294002. Fig. 4B: number in each plot shows the percentage of EGFP-positive cells checked at 6 h postinfection. Fig 4C: pooled data are mean ± SD of percentage of EGFP-positive cells presenting three independent experiments. Fig. 4D: pooled data are mean ± SD of HIV-1 p24 (pg/106 cells), presenting three independent experiments. Fig. 4E: viral cDNA or DNA copies (copies/106 cells), presenting three independent experiments. Black bar: virus-infected Cl 41 cells; open bar: virus-infected Cl 41Δp85.

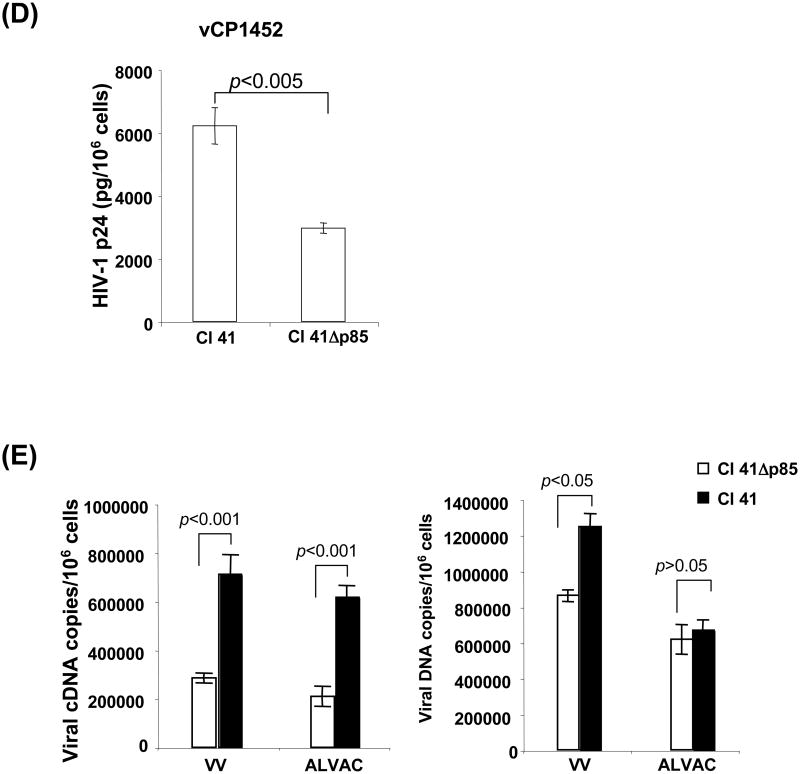

To assess poxvirus-mediated HIV-1 antigen expression, vCP1452 was used to infect Cl 41 cells and CI 41Δp85 cells. HIV-1 Gag protein expression was measured in the infected cell lysates. The level of HIV-1 p24 (pg/106 cells) in vCP1452-infected Cl 41 cells was significantly higher than in vCP1452-infected PI3K dominant-negative Cl 41Δp85 cells (6213 ± 577 pg/106 cells vs 2967 ± 160 pg/106 cells from three experiments, p<0.001)(Fig. 4d). These data further support that the PI3K pathway affects poxvirus-mediated antigen protein expression.

ALVAC virus, a highly attenuated strain of canarypoxvirus, undergoes abortive infection in mammalian cells, yet can achieve expression of extrinsic gene products, whereas VV undergoes productive infection in a variety of mammalian cell lines. It was, therefore, of interest to determine the role of PI3K in poxvirus-mediated mRNA and protein expression as well as viral DNA synthesis by using this PI3K dominant-negative mammalian cell system. Fig. 4E shows that cDNA copies of VV F4L or ALVAC CNPV136 gene were significantly reduced in virus-infected PI3K dominant-negative Cl 41Δp85 cells compared to virus-infected parental Cl 41 cells (284070 ± 20382 vs 710514 ± 80114, p < 0.001 for VV F4L cDNA copies; and 209760 ± 41356 vs 715309 ± 49370, p < 0.001 for ALVAC CNPV136 cDNA copies). As expected, ALVAC DNA copies were observed not significantly different between ALVAC-infected Cl 41 cells and PI3K dominant-negative Cl 41Δp85 cells due to an abortive infection of ALVAC in mammalian cells. VV DNA copies, however, were significantly higher in infected Cl 41 cells than in infected PI3K dominant-negative Cl 41Δp85 cells, indicating that PI3K signaling pathway plays an important role not only in poxvirus-mediated protein and mRNA expression, but also in poxvirus DNA replication when permissive cells are used for the virus infection.

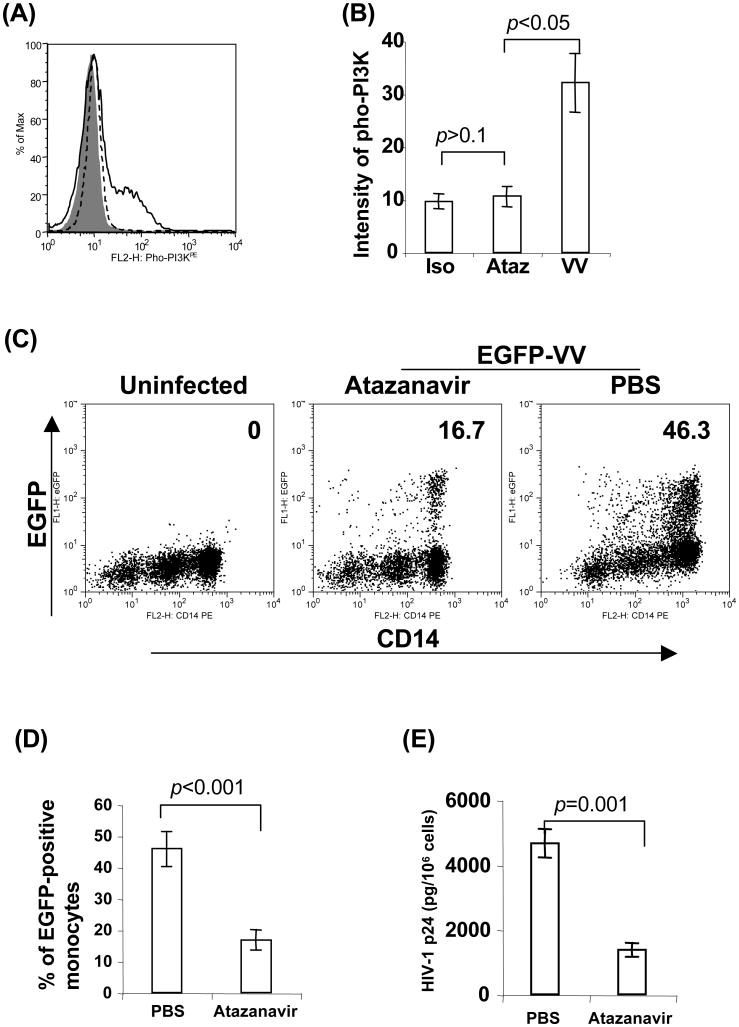

HIV-1 protein inhibitor suppresses poxvirus-mediated protein expression by targeting PI3K/Akt pathway

Live MVA has been developed as an alternative vaccine against smallpox in chronically HIV-1-infected individuals receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (ART), known as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) [75]. Live MVA- and ALVAC-based therapeutic HIV-1 vaccines have been developed and extensively studied in HIV-1-infected patients undergoing HAART. HAART typically uses three or four antiretroviral drugs in combination, including anti-HIV-1 protease inhibitors (PIs) to target viral assembly by inhibiting the activity of protease, an enzyme used by HIV to cleave nascent proteins for final assembly of new virions. PIs have been shown to inhibit PI3K/Akt activation at serum concentrations routinely achieved in HIV-1 patients receiving HAART [76, 77]. Because PI3K/Akt pathway plays a critical role in poxvirus-mediated antigen protein expression, we investigated whether PIs downregulate poxvirus-mediated antigen protein expression via inhibition of PI3K/Akt activation. We found that atazanavir (trade name Reyataz) (Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ), one of PIs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), could inhibit PI3K activation in ALVAC-exposed monocytes and a complete loss of detectable phosphorylation of Akt was observed when 5 μM or higher concentration of atazanavir was used (Fig 5A, B). Similar to PI3K inhibitor LY294002, atazanavir significantly reduced the percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes infected with vCP1540, when used at 5 μM or higher concentration in comparison to PBS treatment control (Fig. 5C, D). HIV-1 Gag expression in vCP1452-infected monocytes also significantly decreased in the presence of atazanavir treatment compared with the control of PBS treatment. Therefore, PIs downregulate poxvirus-mediated antigen protein expression, probably through suppression of PI3K/Akt activation.

Figure 5.

HIV-1 protein inhibitor suppresses poxvirus-mediated protein expression by targeting PI3K/Akt pathway. Monocytes were pretreated with atazanavir at 10 μM for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were then exposed with poxvirus, either ALVAC or vCP1452 at 10 MOI for various time intervals. (A) Cells exposed with ALVAC were harvested at 1 h post-exposure for flow cytometric analysis of PI3K activation with a specific Ab for the phospho-PI3K. (B) Pooled data are mean ± SD of phospho-PI3K fluorescence intensity presenting three independent experiments with different blood donors. (C) Monocytes pretreated with atazanavir at 10 uM for 15 min were infected with vCP1540 at an MOI of 10 for 6 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After infection, cells were harvested for surface staining with anti-human CD14PE Ab, and then subjected to flow cytometric analysis to determine EGFP expression on CD14-positive monocytes. The number in each dot plot shows the percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes in a representative experiment from three independent experiments with different donors. (D) Pooled data are mean ± SD of percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes presenting three independent experiments with different donors. (E) Monocytes infected with vCP1452 for 6 h were harvested and washed 2 times with ice-chilled PBS. Cells were resuspended in 50 μl PBS, and then lysed with 50 μl of lysis buffer appended in the HIV p24 ELISA kit for measuring HIV-1 Gag p24 expression. Pooled data are mean ± SD of HIV-1 p24 (pg/106 monocytes) presenting three independent experiments with different donors.

Discussion

The principal finding of the present study is that both VV and ALVAC triggered a vigorous activation of multiple cell signaling pathways including PI3K, ERK, P38 MAPK, and JNK in the early stage of virus infection. Activation of these signaling pathways, except ERK, plays a pivotal role in regulation of poxvirus-mediated foreign gene expression at levels of protein and mRNA synthesis in unpermissive cells, and also at the level of viral DNA replication in permissive cells. VV undergoes a non-productive abortive infection in primary human monocytes [53-55] and ALVAC infection of mammalian cells including human monocytes is also abortive [24, 52], yet they can express appropriately engineered foreign genes in the infected cells [4]. Activation of cell signaling pathways is required to deliver mitogenic signals for regulation of poxvirus-mediated gene expression. Early studies have demonstrated that activation of MAPK plays a pivotal role for VV multiplication [40, 41]. VV infection provoked a sustained activation of ERK1/2 in permissive A31 cells (a clone derived from mouse Balb/c 3T3 cells), and subsequently exerted effects on viral thymidine kinase gene expression, viral DNA replication, and VV multiplication [41]. Consistent with these recent reports, we also observed that the activation of ERK signal pathway was triggered in VV-exposed primary human monocytes, which are unpermissive cells to VV infection. However, this pathway activation did not exert an effect on VV-mediated gene expression at the levels of protein and mRNA synthesis, as blocking ERK signaling pathway with its inhibitor PD98059 slightly reduced VV-expressed EGFP, and cDNA copies of VV F4L gene, which was not statistically significant in comparison with the DMSO alone condition. It is noteworthy that we only monitored the effects of ERK activation on regulation of gene expression at early stage of VV infection. In fact, VV-stimulated ERK activation was prolonged and yet sustained, i.e. the activation was detectable from early stages of the infection, up to times (36 h postinfection) when the cytopathic effect was clearly visualized in at least 90% of the A31 cells [41]. The effect of VV-mediated ERK activation on gene expression in the late stages of virus infection was not investigated in this study, because VV could induce extensive cytopathic effects, rRNA breakdown, and apoptosis at late times postinfection in primary mammalian cells [77], which could impact the study outcomes. VV has also been shown to activate p38 MAPK [38] and JNK [39], leading to permissive virus replication in a variety of diverse cell lines. The activation of these signaling pathways was consistently reproduced in VV-exposed mammalian cells in the current study. In addition, we also found that exposure of VV to primary human monocytes or mouse A31 cells triggered activation of PI3K signaling pathway. In contrast to ERK, activation of PI3K, p38 MAPK, and JNK played a pivotal role in regulation of VV-mediated protein and mRNA expression in primary human monocytes, as blocking either PI3K with LY294002, p38 MAPK with SB203580, or JNK with SP600215 significantly reduced the percentage of EGFP-positive monocytes as well as the cDNA copies of VV F4L gene. Blocking the PI3K signaling pathway, however, gave the strongest inhibition of EGFP and VV F4L gene productions. Further, in permissive cells, VV DNA copies were significantly decreased in the absence of normal function of PI3K pathway, indicating that PI3K signaling pathway plays an important role not only in poxvirus-mediated protein and mRNA expression, but also in poxvirus DNA replication when permissive cells are used for the virus infection. Token together, the PI3K/Akt, p38 MAPK, and JNK pathways play a critical role in VV-mediated gene expression at levels of mRNA and protein synthesis in unpermissive cells, also at level of DNA replication if permissive cells are used.

ALVAC has been extensively studied as an alternative vector of VV for development of new recombinant vaccines, as application potential of VV is limited by the pre-existence of VV-immunity in the smallpox-vaccinated population as well as rare adverse affects ranging from eczema vaccinatum, to myocarditis, to vaccinial encephalitis, resulting in fatal complications and substantial morbidity in some individuals [7]. Considering the substantial differences in host tropism, replicative capacity, and genome sequences between the VV and ALVAC, it cannot be assumed that the activation magnitude and pattern of VV-stimulated signaling pathways are paralleled by ALVAC. In addition to this consideration, the early events of signal transduction in infected cells have not yet been addressed for ALVAC. We have focused here on a side-by-side comparison of ALVAC and VV capacities in activation of signaling pathways in the early stage of virus infection. Similar to VV, ALVAC triggered activation of PI3K, ERK, p38 MAPK, and JNK signaling pathways and activation of these pathways, except ERK, was observed to play a pivotal role in regulation of ALVAC-mediated protein and mRNA expression. The similar activation magnitude and pattern of cell signaling pathways were observed between VV- and ALVAC-infected mammalian cells, suggesting that activation of multiple signaling pathways is a common theme in response to poxvirus infection. Interestingly, we found that both VV infectious forms of IMV and EEV, purified from cell lysates and culture supernatant respectively, triggered activation of the four signaling pathways examined at same level in terms of their phosphorylation intensity determined by flow cytometric analysis and Western blot. These findings suggest that both VV infectious forms of IMV and EEV may use a common mechanism to trigger cellular responses in the early stage of poxvirus infection, which needs further investigation. It is noteworthy that the outer membrane of EEV is extremely fragile, and pure populations of this virus form are difficult to prepare [78, 79]. The virus preparation protocol we used in this study is a standard sucrose untracentrifuge protocol which most likely generates a mixture of VV virion forms including intact EEV and EEV with a damaged outer membrane from culture supernatant of VV-infected cells. When the outer EEV membrane is ruptured, the particle resembles an IMV and remains fully infective [50].

We also observed that ALVAC viruses purified from culture supernatant of ALVAC-infected CEFs exhibited the similar infectious capacities to mammalian cells including primary human monocytes and mouse epidermal cell lines with the viruses purified from lysates of ALVAC-infected CEFs (data not shown), suggesting that ALVAC may also exist at least two infectious forms as VV does. In addition, similar to VV, ALVAC viruses purified from either cell lysates or culture supernatant of ALVAC-infected CEFs could equally trigger multiple cell signaling pathways. The magnitude and pattern of ALVAC-triggered activation of cell signaling pathways are similar to VV infection. These findings are consistent with the notion that poxvirus members exist multiple infectious forms, which can activate of multiple cell signaling pathways in the early stage of virus infection.

The data concerning poxvirus entry are controversial. Recent data have demonstrated that VV infection of primary hematolymphoid cells requires specific cell receptors [50]. However, earlier studies using electron microscopy have shown that VV may enter cells by phagocytosis [80]. During the process of phagocytosis, interaction of VV with cell surface may induce a complex signaling cascade, leading to activation of cell signaling pathways. The entry of large particles such as intracellular bacteria into mammalian cells generally involves phagocytosis. As a critical step of phagocytosis, protein rearrangements at the plasma membrane occur to form a phagocytic cup that engulfs the bacterium, consequently leading to cellular response to bacterial infection. Whether poxvirus triggers activation of cell signaling pathways through phagocytosis needs further investigations.

Live MVA has been developed as an alternative vaccine against smallpox in chronically HIV-1-infected individuals receiving HAART [75]. Live MVA- and ALVAC-based therapeutic HIV-1 vaccines have been developed and extensively studied in HIV-1-infected patients undergoing HAART [66, 81-86]. Our findings that a commonly used PI, atazanavir, could inhibit PI3K activation in ALVAC-exposed monocytes resulting in reduced poxvirus-mediated antigen protein expression has major implications in considering the use of poxvirus derived vectors as therapeutic vaccines in PI treated individuals, and will likely fuel investigations into the immunogenicity of poxvirus derived vaccine in this patient population [87].

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Huang C. at NYU for cells, to Dr. Moss B. and Dr. Yewdell JW. at NIH for vaccinia viruses, and to Sanofi-Pasteur for ALVAC viruses. This work was supported in part by grant R21AI073250 (Q.Y.), the New Investigator Award from the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research (AI 27757 to Q.Y.), and the Research Facilities Improvement Program Grant Number C06 RR015481-01 from the National Center for Research Resources, NIH to Indiana University School of Medicine.

Abbreviations used are

- VV

Vaccinia virus

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescence protein

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI3K

phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- p38 MAPK

p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- ART

antiretroviral therapy

- HAART

highly active antiretroviral therapy

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- PI

protease inhibitor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Moss B. Vaccinia and other poxvirus expression vectors. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1992 Oct;3(5):518–22. doi: 10.1016/0958-1669(92)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moss B, Fuerst TR, Flexner C, Hugin A. Roles of vaccinia virus in the development of new vaccines. Vaccine. 1988 Apr;6(2):161–3. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(88)80021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss B, Flexner C. Vaccinia virus expression vectors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1987;5:305–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.05.040187.001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poulet H, Minke J, Pardo MC, Juillard V, Nordgren B, Audonnet JC. Development and registration of recombinant veterinary vaccines. The example of the canarypox vector platform. Vaccine. 2007 Jul 26;25(30):5606–12. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.11.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perkus ME, Tartaglia J, Paoletti E. Poxvirus-based vaccine candidates for cancer, AIDS, and other infectious diseases. J Leukoc Biol. 1995 Jul;58(1):1–13. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wharton M, Strikas RA, Harpaz R, Rotz LD, Schwartz B, Casey CG, et al. Recommendations for using smallpox vaccine in a pre-event vaccination program. Supplemental recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee (HICPAC) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003 Apr 4;52(RR-7):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krugman S, Katz SL. Smallpox vaccination. N Engl J Med. 1969 Nov 27;281(22):1241–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196911272812211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu Q, Jones B, Hu N, Chang H, Ahmad S, Liu J, et al. Comparative analysis of tropism between canarypox (ALVAC) and vaccinia viruses reveals a more restricted and preferential tropism of ALVAC for human cells of the monocytic lineage. Vaccine. 2006 Sep 29;24(40-41):6376–91. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ignatius R, Marovich M, Mehlhop E, Villamide L, Mahnke K, Cox WI, et al. Canarypox virus-induced maturation of dendritic cells is mediated by apoptotic cell death and tumor necrosis factor alpha secretion. J Virol. 2000 Dec;74(23):11329–38. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.23.11329-11338.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paoletti E, Taylor J, Meignier B, Meric C, Tartaglia J. Highly attenuated poxvirus vectors: NYVAC, ALVAC and TROVAC. Dev Biol Stand. 1995;84:159–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox WI, Tartaglia J, Paoletti E. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by recombinant canarypox (ALVAC) and attenuated vaccinia (NYVAC) viruses expressing the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein. Virology. 1993 Aug;195(2):845–50. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amara RR, Villinger F, Altman JD, Lydy SL, O'Neil SP, Staprans SI, et al. Control of a mucosal challenge and prevention of AIDS by a multiprotein DNA/MVA vaccine. Science. 2001 Apr 6;292(5514):69–74. doi: 10.1126/science.1058915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hel Z, Tsai WP, Thornton A, Nacsa J, Giuliani L, Tryniszewska E, et al. Potentiation of simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-specific CD4(+) and CD8(+) T cell responses by a DNA-SIV and NYVAC-SIV prime/boost regimen. J Immunol. 2001 Dec 15;167(12):7180–91. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gherardi MM, Najera JL, Perez-Jimenez E, Guerra S, Garcia-Sastre A, Esteban M. Prime-boost immunization schedules based on influenza virus and vaccinia virus vectors potentiate cellular immune responses against human immunodeficiency virus Env protein systemically and in the genitorectal draining lymph nodes. J Virol. 2003 Jun;77(12):7048–57. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.12.7048-7057.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Didierlaurent A, Ramirez JC, Gherardi M, Zimmerli SC, Graf M, Orbea HA, et al. Attenuated poxviruses expressing a synthetic HIV protein stimulate HLA-A2-restricted cytotoxic T-cell responses. Vaccine. 2004 Sep 3;22(25-26):3395–403. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gomez CE, Abaitua F, Rodriguez D, Esteban M. Efficient CD8+ T cell response to the HIV-env V3 loop epitope from multiple virus isolates by a DNA prime/vaccinia virus boost (rWR and rMVA strains) immunization regime and enhancement by the cytokine IFN-gamma. Virus Res. 2004 Sep 15;105(1):11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez CE, Najera JL, Domingo-Gil E, Ochoa-Callejero L, Gonzalez-Aseguinolaza G, Esteban M. Virus distribution of the attenuated MVA and NYVAC poxvirus strains in mice. J Gen Virol. 2007 Sep;88(Pt 9):2473–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster DP, Dunachie S, Vuola JM, Berthoud T, Keating S, Laidlaw SM, et al. Enhanced T cell-mediated protection against malaria in human challenges by using the recombinant poxviruses FP9 and modified vaccinia virus Ankara. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Mar 29;102(13):4836–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406381102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fries LF, Tartaglia J, Taylor J, Kauffman EK, Meignier B, Paoletti E, et al. Human safety and immunogenicity of a canarypox-rabies glycoprotein recombinant vaccine: an alternative poxvirus vector system. Vaccine. 1996 Apr;14(5):428–34. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(95)00171-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welter J, Taylor J, Tartaglia J, Paoletti E, Stephensen CB. Vaccination against canine distemper virus infection in infant ferrets with and without maternal antibody protection, using recombinant attenuated poxvirus vaccines. J Virol. 2000 Jul;74(14):6358–67. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6358-6367.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tartaglia J, Jarrett O, Neil JC, Desmettre P, Paoletti E. Protection of cats against feline leukemia virus by vaccination with a canarypox virus recombinant, ALVAC-FL. J Virol. 1993 Apr;67(4):2370–5. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2370-2375.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salmon-Ceron D, Excler JL, Finkielsztejn L, Autran B, Gluckman JC, Sicard D, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a live recombinant canarypox virus expressing HIV type 1 gp120 MN MN tm/gag/protease LAI (ALVAC-HIV, vCP205) followed by a p24E-V3 MN synthetic peptide (CLTB-36) administered in healthy volunteers at low risk for HIV infection. AGIS Group and L'Agence Nationale de Recherches sur Le Sida. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1999 May 1;15(7):633–45. doi: 10.1089/088922299310935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karnasuta C, Paris RM, Cox JH, Nitayaphan S, Pitisuttithum P, Thongcharoen P, et al. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxic responses in participants enrolled in a phase I/II ALVAC-HIV/AIDSVAX B/E prime-boost HIV-1 vaccine trial in Thailand. Vaccine. 2005 Mar 31;23(19):2522–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tartaglia J, Perkus ME, Taylor J, Norton EK, Audonnet JC, Cox WI, et al. NYVAC: a highly attenuated strain of vaccinia virus. Virology. 1992 May;188(1):217–32. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90752-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marovich MA, Mascola JR, Eller MA, Louder MK, Caudrelier PA, El-Habib R, et al. Preparation of clinical-grade recombinant canarypox-human immunodeficiency virus vaccine-loaded human dendritic cells. J Infect Dis. 2002 Nov 1;186(9):1242–52. doi: 10.1086/344302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marovich MA. ALVAC-HIV vaccines: clinical trial experience focusing on progress in vaccine development. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004 Aug;3(4 Suppl):S99–104. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.4.s99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jaoko W, Nakwagala FN, Anzala O, Manyonyi GO, Birungi J, Nanvubya A, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of recombinant low-dosage HIV-1 A vaccine candidates vectored by plasmid pTHr DNA or modified vaccinia virus Ankara (MVA) in humans in East Africa. Vaccine. 2008 May 23;26(22):2788–95. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shephard E, Burgers WA, Van Harmelen JH, Monroe JE, Greenhalgh T, Williamson C, et al. A multigene HIV type 1 subtype C modified vaccinia Ankara (MVA) vaccine efficiently boosts immune responses to a DNA vaccine in mice. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008 Feb;24(2):207–17. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mooij P, Balla-Jhagjhoorsingh SS, Koopman G, Beenhakker N, van Haaften P, Baak I, et al. Differential CD4+ versus CD8+ T-cell responses elicited by different poxvirus-based human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vaccine candidates provide comparable efficacies in primates. J Virol. 2008 Mar;82(6):2975–88. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02216-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wyatt LS, Belyakov IM, Earl PL, Berzofsky JA, Moss B. Enhanced cell surface expression, immunogenicity and genetic stability resulting from a spontaneous truncation of HIV Env expressed by a recombinant MVA. Virology. 2008 Mar 15;372(2):260–72. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Corbett M, Bogers WM, Heeney JL, Gerber S, Genin C, Didierlaurent A, et al. Aerosol immunization with NYVAC and MVA vectored vaccines is safe, simple, and immunogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Feb 12;105(6):2046–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705191105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manrique M, Micewicz E, Kozlowski PA, Wang SW, Aurora D, Wilson RL, et al. DNA-MVA vaccine protection after X4 SHIV challenge in macaques correlates with day-of-challenge antiviral CD4+ cell-mediated immunity levels and postchallenge preservation of CD4+ T cell memory. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2008 Mar;24(3):505–19. doi: 10.1089/aid.2007.0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andersson S, Makitalo B, Thorstensson R, Franchini G, Tartaglia J, Limbach K, et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of a human immunodeficiency virus type 2 recombinant canarypox (ALVAC) vaccine candidate in cynomolgus monkeys. J Infect Dis. 1996 Nov;174(5):977–85. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adler SP, Plotkin SA, Gonczol E, Cadoz M, Meric C, Wang JB, et al. A canarypox vector expressing cytomegalovirus (CMV) glycoprotein B primes for antibody responses to a live attenuated CMV vaccine (Towne) J Infect Dis. 1999 Sep;180(3):843–6. doi: 10.1086/314951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Konishi E, Kurane I, Mason PW, Shope RE, Kanesa-Thasan N, Smucny JJ, et al. Induction of Japanese encephalitis virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in humans by poxvirus-based JE vaccine candidates. Vaccine. 1998 May;16(8):842–9. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00265-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghose A, Iakhnina E, Spaner D, Tartaglia J, Berinstein NL. Immunogenicity of whole-cell tumor preparations infected with the ALVAC viral vector. Hum Gene Ther. 2000 Jun 10;11(9):1289–301. doi: 10.1089/10430340050032393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arlen PM, Skarupa L, Pazdur M, Seetharam M, Tsang KY, Grosenbach DW, et al. Clinical safety of a viral vector based prostate cancer vaccine strategy. J Urol. 2007 Oct;178(4 Pt 1):1515–20. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.05.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maloney G, Schroder M, Bowie AG. Vaccinia virus protein A52R activates p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and potentiates lipopolysaccharide-induced interleukin-10. J Biol Chem. 2005 Sep 2;280(35):30838–44. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Santos CR, Blanco S, Sevilla A, Lazo PA. Vaccinia virus B1R kinase interacts with JIP1 and modulates c-Jun-dependent signaling. J Virol. 2006 Aug;80(15):7667–75. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00967-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Magalhaes JC, Andrade AA, Silva PN, Sousa LP, Ropert C, Ferreira PC, et al. A mitogenic signal triggered at an early stage of vaccinia virus infection: implication of MEK/ERK and protein kinase A in virus multiplication. J Biol Chem. 2001 Oct 19;276(42):38353–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100183200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Andrade AA, Silva PN, Pereira AC, De Sousa LP, Ferreira PC, Gazzinelli RT, et al. The vaccinia virus-stimulated mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is required for virus multiplication. Biochem J. 2004 Jul 15;381(Pt 2):437–46. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panteva M, Korkaya H, Jameel S. Hepatitis viruses and the MAPK pathway: is this a survival strategy? Virus Res. 2003 Apr;92(2):131–40. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(02)00356-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee S, Tarn C, Wang WH, Chen S, Hullinger RL, Andrisani OM. Hepatitis B virus X protein differentially regulates cell cycle progression in X-transforming versus nontransforming hepatocyte (AML12) cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2002 Mar 8;277(10):8730–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108025200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan H, Xie J, Ye F, Gao SJ. Modulation of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infection and replication by MEK/ERK, JNK, and p38 multiple mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways during primary infection. J Virol. 2006 Jun;80(11):5371–82. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02299-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perkins D, Pereira EF, Gober M, Yarowsky PJ, Aurelian L. The herpes simplex virus type 2 R1 protein kinase (ICP10 PK) blocks apoptosis in hippocampal neurons, involving activation of the MEK/MAPK survival pathway. J Virol. 2002 Feb;76(3):1435–49. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1435-1449.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gee K, Angel JB, Mishra S, Blahoianu MA, Kumar A. IL-10 regulation by HIV-Tat in primary human monocytic cells: involvement of calmodulin/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-activated p38 MAPK and Sp-1 and CREB-1 transcription factors. J Immunol. 2007 Jan 15;178(2):798–807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang X, Gabuzda D. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphorylates and regulates the HIV-1 Vif protein. J Biol Chem. 1998 Nov 6;273(45):29879–87. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.45.29879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pleschka S, Wolff T, Ehrhardt C, Hobom G, Planz O, Rapp UR, et al. Influenza virus propagation is impaired by inhibition of the Raf/MEK/ERK signalling cascade. Nat Cell Biol. 2001 Mar;3(3):301–5. doi: 10.1038/35060098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lambert PJ, Shahrier AZ, Whitman AG, Dyson OF, Reber AJ, McCubrey JA, et al. Targeting the PI3K and MAPK pathways to treat Kaposi's-sarcoma-associated herpes virus infection and pathogenesis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007 May;11(5):589–99. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chahroudi A, Chavan R, Kozyr N, Waller EK, Silvestri G, Feinberg MB. Vaccinia virus tropism for primary hematolymphoid cells is determined by restricted expression of a unique virus receptor. J Virol. 2005 Aug;79(16):10397–407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10397-10407.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sanchez-Puig JM, Sanchez L, Roy G, Blasco R. Susceptibility of different leukocyte cell types to Vaccinia virus infection. Virol J. 2004;1:10. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor J, Meignier B, Tartaglia J, Languet B, VanderHoeven J, Franchini G, et al. Biological and immunogenic properties of a canarypox-rabies recombinant, ALVAC-RG (vCP65) in non-avian species. Vaccine. 1995 Apr;13(6):539–49. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(94)00028-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Engelmayer J, Larsson M, Subklewe M, Chahroudi A, Cox WI, Steinman RM, et al. Vaccinia virus inhibits the maturation of human dendritic cells: a novel mechanism of immune evasion. J Immunol. 1999 Dec 15;163(12):6762–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jenne L, Hauser C, Arrighi JF, Saurat JH, Hugin AW. Poxvirus as a vector to transduce human dendritic cells for immunotherapy: abortive infection but reduced APC function. Gene Ther. 2000 Sep;7(18):1575–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3301287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Broder CC, Kennedy PE, Michaels F, Berger EA. Expression of foreign genes in cultured human primary macrophages using recombinant vaccinia virus vectors. Gene. 1994 May 16;142(2):167–74. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90257-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. Efficient presentation of soluble antigen by cultured human dendritic cells is maintained by granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor plus interleukin 4 and downregulated by tumor necrosis factor alpha. J Exp Med. 1994 Apr 1;179(4):1109–18. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ostrowski MA, Justement SJ, Ehler L, Mizell SB, Lui S, Mican J, et al. The role of CD4+ T cell help and CD40 ligand in the in vitro expansion of HIV-1-specific memory cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2000 Dec 1;165(11):6133–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yu Q, Gu JX, Kovacs C, Freedman J, Thomas EK, Ostrowski MA. Cooperation of TNF family members CD40 ligand, receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand, and TNF-alpha in the activation of dendritic cells and the expansion of viral specific CD8+ T cell memory responses in HIV-1-infected and HIV-1-uninfected individuals. J Immunol. 2003 Feb 15;170(4):1797–805. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li J, Davidson G, Huang Y, Jiang BH, Shi X, Costa M, et al. Nickel compounds act through phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/Akt-dependent, p70(S6k)-independent pathway to induce hypoxia inducible factor transactivation and Cap43 expression in mouse epidermal Cl41 cells. Cancer Res. 2004 Jan 1;64(1):94–101. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang C, Li J, Song L, Zhang D, Tong Q, Ding M, et al. Black raspberry extracts inhibit benzo(a)pyrene diol-epoxide-induced activator protein 1 activation and VEGF transcription by targeting the phosphotidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Cancer Res. 2006 Jan 1;66(1):581–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li J, Tong Q, Shi X, Costa M, Huang C. ERKs activation and calcium signaling are both required for VEGF induction by vanadium in mouse epidermal Cl41 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2005 Nov;279(1-2):25–33. doi: 10.1007/s11010-005-8212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ouyang W, Luo W, Zhang D, Jian J, Ma Q, Li J, et al. PI-3K/Akt pathway-dependent cyclin D1 expression is responsible for arsenite-induced human keratinocyte transformation. Environ Health Perspect. 2008 Jan;116(1):1–6. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ding J, Li J, Chen J, Chen H, Ouyang W, Zhang R, et al. Effects of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) on vascular endothelial growth factor induction through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AP-1-dependent, HIF-1alpha-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006 Apr 7;281(14):9093–100. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510537200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ouyang W, Li J, Ma Q, Huang C. Essential roles of PI-3K/Akt/IKKbeta/NFkappaB pathway in cyclin D1 induction by arsenite in JB6 Cl41 cells. Carcinogenesis. 2006 Apr;27(4):864–73. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Norbury CC, Malide D, Gibbs JS, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Visualizing priming of virus-specific CD8+ T cells by infected dendritic cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2002 Mar;3(3):265–71. doi: 10.1038/ni762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jin X, Ramanathan M, Jr, Barsoum S, Deschenes GR, Ba L, Binley J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ALVAC vCP1452 and recombinant gp160 in newly human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected patients treated with prolonged highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Virol. 2002 Mar;76(5):2206–16. doi: 10.1128/jvi.76.5.2206-2216.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vanderplasschen A, Hollinshead M, Smith GL. Intracellular and extracellular vaccinia virions enter cells by different mechanisms. J Gen Virol. 1998 Apr;79(Pt 4):877–87. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-4-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Appleyard G, Hapel AJ, Boulter EA. An antigenic difference between intracellular and extracellular rabbitpox virus. J Gen Virol. 1971 Oct;13(1):9–17. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-13-1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ichihashi Y, Matsumoto S, Dales S. Biogenesis of poxviruses: role of A-type inclusions and host cell membranes in virus dissemination. Virology. 1971 Dec;46(3):507–32. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(71)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vanderplasschen A, Smith GL. A novel virus binding assay using confocal microscopy: demonstration that the intracellular and extracellular vaccinia virions bind to different cellular receptors. J Virol. 1997 May;71(5):4032–41. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4032-4041.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Payne LG. Significance of extracellular enveloped virus in the in vitro and in vivo dissemination of vaccinia. J Gen Virol. 1980 Sep;50(1):89–100. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-1-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Doms RW, Blumenthal R, Moss B. Fusion of intra- and extracellular forms of vaccinia virus with the cell membrane. J Virol. 1990 Oct;64(10):4884–92. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.10.4884-4892.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simpson DA, Feeney S, Boyle C, Stitt AW. Retinal VEGF mRNA measured by SYBR green I fluorescence: A versatile approach to quantitative PCR. Mol Vis. 2000 Oct 5;6:178–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen J, Zhao X, Lai Y, Suzuki A, Tomaru U, Ishizu A, et al. Enhanced production of p24 Gag protein in HIV-1-infected rat cells fused with uninfected human cells. Exp Mol Pathol. 2007 Aug;83(1):125–30. doi: 10.1016/j.yexmp.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cosma A, Nagaraj R, Staib C, Diemer C, Wopfner F, Schatzl H, et al. Evaluation of modified vaccinia virus Ankara as an alternative vaccine against smallpox in chronically HIV type 1-infected individuals undergoing HAART. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2007 Jun;23(6):782–93. doi: 10.1089/aid.2006.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gupta AK, Cerniglia GJ, Mick R, McKenna WG, Muschel RJ. HIV protease inhibitors block Akt signaling and radiosensitize tumor cells both in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2005 Sep 15;65(18):8256–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]