Abstract

Background

HIV-positive injection drug users (IDU) are known to be at risk for multiple medical problems that may necessitate emergency department (ED) use, however, the relative contribution of HIV disease versus injection-related complications have not been well described.

Objectives

We examined factors associated with ED use among a prospective cohort of HIV-positive IDU in a Canadian setting.

Methods

We enrolled HIV-positive IDU into a community-recruited prospective cohort study. We modeled factors associated with the time to first ED visit using Cox regression to determine factors independently associated with ED use. In sub-analyses, we examined ED diagnoses and subsequent hospital admission rates.

Results

Between December 5, 2005, and April 30, 2008, 428 HIV-positive IDU were enrolled, among whom the cumulative incidence of ED use was 63.7% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 59.1% – 68.3%) at 12 months after enrollment. Factors independently associated with time to first ED visit included: unstable housing (Hazard Ratio [HR] = 1.5, 95% CI: 1.1–2.0) and reporting being unable to obtain needed health care services (HR = 2.2, 95% CI: 1.2–4.1), whereas CD4 count and viral load were non-significant. Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) accounted for the greatest proportion of ED visits (17%). Of the 2461 visits to the ED, 419 (17%) were admitted to hospital.

Conclusions

High rates of ED use were observed among HIV-positive IDU, a behavior that was predicted by unstable housing and limited access to primary care. Factors other than HIV infection appear to be driving ED use among this population in the post-HAART era.

Keywords: Emergency Service, Injection Drug Use, HIV, Canada

INTRODUCTION

Illicit injection drug use is associated with an array of health-related harms and health care expenditures, including emergency department (ED) use.1-2 Injection drug users (IDU) often have poor health status attributable to drug abuse and infectious diseases such as HIV and hepatitis C (HCV).3-5 Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) are also common injection-related complications that bring IDU to the ED.1-2, 6-7 Socio-demographic factors such as homelessness have also been linked to elevated ED and hospital use among IDU and barriers such as lack of access to primary care services have been described in several settings.2, 8-9

Though remarkable advances to HIV/AIDS treatment and care have been made over the past two decades since the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), there is evidence that HIV-positive IDU continue to have unmet health needs with respect to HIV and related care.10-11 IDU have been shown to be more likely to have poorly managed HIV infection due to decreased uptake of HAART and there is some evidence to suggest that HIV-positive IDU continue to have increased use of EDs and more frequent hospitalizations in the post-HAART era compared with other IDU. 2, 12-15

Given the dual susceptibilities of HIV-positive IDU to the complications of poorly managed HIV infection and injection drug use, and potential barriers to health care this population may experience, understanding factors associated with acute care service utilization is essential to better serve seropositive IDU in the ED. We therefore examined the prevalence and correlates of ED use, as well as primary ED diagnoses and hospital admission rates, among a community-recruited cohort of HIV-positive IDU.

METHODS

Data for these analyses were derived from a community-recruited open prospective cohort study of HIV-positive IDU, which has been described in detail previously.16-17 The study instrument was developed from validated United States (US) instruments.18-19 The study was created to examine issues related to access to HIV/AIDS care among IDU.20 In brief, recruitment for the AIDS Care Cohort to Evaluate Exposure to Survival Services (ACCESS) occurred through extensive street-based outreach and word of mouth. Beginning in May 1996, participants were recruited through self-referral and street outreach from Vancouver's Downtown Eastside (DTES), a neighborhood that ranks below the city average in almost all social and economic indicators. There is a large open-drug scene with an estimated 4,700 IDU residing in an area of approximately ten city blocks.21 The ACCESS office is situated in the hub of the city's Downtown Eastside where the majority of injection drug use is concentrated. Study participants are seen on a semi-annual basis at which time they answer a standardized interviewer administered questionnaire and provide a blood sample for research purposes. The study has five full-time staff conducting interviews, many of whom have worked in the community for several years. All variables, with the exception of ED contact and CD4 cell count and viral load determinations, were based on responses to the questionnaire. The location and longevity of both the study site and interview staff aids follow-up and may improve reliability of self-reported stigmatizing behaviors.

Participants were eligible for the study if they were 18 years of age or older, resided in the greater Vancouver region, tested HIV-positive upon entry, had injected an illegal drug during the previous month, and provided informed consent. HIV infection was detected using ELISA and positive test results were confirmed using western blot. At baseline and semi-annual follow-up, participants completed a lengthy interviewer-administered questionnaire that elicits information regarding sociodemographic characteristics, drug use patterns, sexual behaviors, and other relevant exposures. At baseline and semi-annually, all HIV-positive participants provide blood samples to monitor disease progression and complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire. The questionnaire elicits demographic data as well as information about participants’ drug use, including information about type of drug, frequency of drug use, involvement in drug treatment and periods of abstinence. All participants provide informed consent and are remunerated $20 CDN for each study visit. The study is approved on an annual basis by the University of British Columbia/Providence Healthcare Research Ethics Board at its St. Paul's Hospital site.

The primary endpoint of interest in the present analysis was time to first ED visit among cohort participants and we were particularly interested in the potential role of clinical characteristics and unstable housing on ED use. Health record linkages were accessed via the electronic health records department at St. Paul's hospital (SPH), the local tertiary care centre that provides the majority of health care to local IDU, to determine the time to first ED use.1-2, 8 Since we were interested in the role of HIV/AIDS disease progression on ED use, individuals were further eligible if baseline CD4 count and viral load measures were available within one year of recruitment to allow ascertainment of progression of HIV disease at baseline. We considered Aboriginal ethnicity due to the large representation of Aboriginal persons in the Downtown Eastside and the significantly elevated burden of HIV infection in this population.22 Based on a sample size of 428 participants and a known event rate of 73.6% from past research among local IDU, formal sample size calculations were deemed unnecessary.23

Kaplan-Meier methods and Cox regression was used to determine factors associated with time to first ED visit during the study period. The primary explanatory variables were age; gender (male vs. female); Aboriginal ethnicity (yes vs. no); Downtown Eastside neighbourhood residence (yes vs. no); unstable housing; daily crack cocaine smoking (≥ daily vs. less); daily heroin injection (≥ daily vs. less); daily cocaine injection (≥ daily vs. less); sex trade involvement (yes vs. no); history of physical assault (yes vs. no); inability to access health services (yes vs. no); current participation in methadone maintenance therapy (MMT) (yes vs. no); baseline CD4 cell count (per 100 cells/mm3) and baseline plasma HIV-1 RNA viral load (per log10). All variable definitions were identical to earlier reports.24-25 Aboriginal ethnicity was defined by self-report as First Nations, Inuit, Metis, or Aboriginal. In Canada, First Nations is typically defined as indigenous peoples of North America, Inuit refers to indigenous peoples inhabiting Arctic regions, Metis refers to people of mixed First Nations and European descent, and Aboriginal can refer to any of the above. Unstable housing was defined as previously as living in a single room occupancy hotel, shelter, recovery or transition house, jail, on the street, or having no fixed address.26-27 The variable for ability to access health services was based on responses to the question: “reporting inability to obtain needed health services (including hospital, nurse, doctor or clinic care [yes vs. no].” Unless otherwise noted, all variables refer to the six-month period prior to the interview and the multivariate model treated all behavioural variables as time-updated based on each semi-annual follow-up visit. Specifically, if during follow-up a participant changed from stable to unstable housing, the statistical model considered this within individual variation. The same was done for other behavioral variables.

The final multivariate model included all variables that were statistically significant at p<=0.05 level in the univariate analysis, and baseline CD4 count and baseline viral load that were forced into the model. All continuous variables met the assumption of linearity. Examinations showed no sign of non-linearity in CD4 count and using dichotomized CD4 count (≥200 vs. <200) gave similar results. The proportional hazards assumption for time-independent variables was assessed to be valid. When time-updated variables were used in the Cox regression model it was no longer a proportional hazards model. The VIF (variance inflation factor) test showed no evidence of collinearity.

In sub-analyses, we identified the primary ICD-9 diagnosis code for each hospital admission, and examined the number of hospital admissions. The ICD-9 Diseases/Injuries Tabular Index has been used in previous studies to analyze the characteristics of ED and hospital discharge diagnoses in HIV-positive patients.28-29 All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS, Cary, NC). All p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

Between 5 December 2005, and 30 April 2008, 437 HIV-positive IDU were recruited for this study. Nine individuals were excluded for lack of baseline CD4 count or baseline viral load data. Among 428 eligible participants, the cumulative incidence of ED use was 63.7% (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 59.1% – 68.3%) at 12 months after enrollment. The median duration of follow-up was 6.5 months (IQ range: 1.8 – 18.3) and among the entire sample of 428 individuals that were seen at the start of the study period, 152 (35%) had at least two study visits. Baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 428 ACCESS participants in Vancouver, Canada

| Characteristic | median | Interquartile (IQ) range | n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41 | 36 - 47 | |

| Female Gender | 170 (39.72) | ||

| Aboriginal Ethnicity | 178 (41.59) | ||

| DTES Residence * | 291 (68.00) | ||

| Viral Load (Copies/mL) † | 3,845 | 49 – 45,150 | |

| CD4 Count (Copies/mL) † | 290 | 170-460 |

Behaviours refer to activities in the last six months.

Indicates baseline value.

Unstable Housing (Kaplan-Meier Analyses)

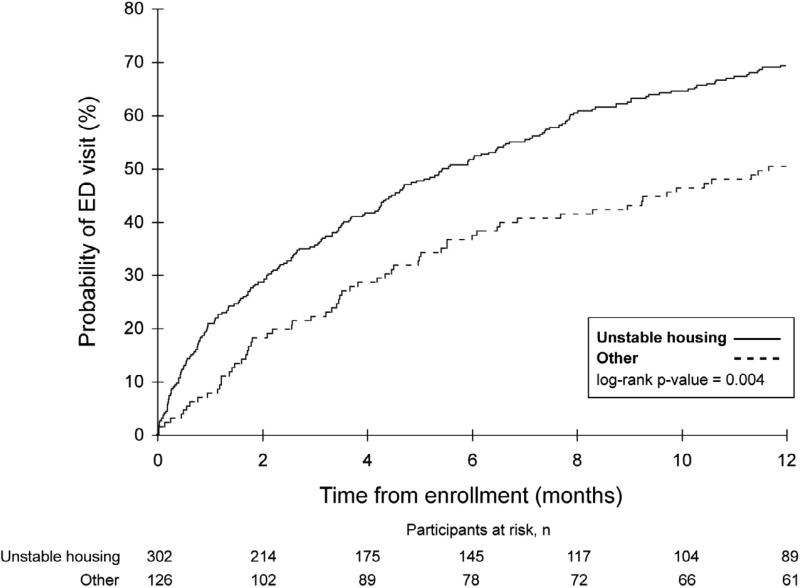

As shown in Figure 1, at 12 months after recruitment, the Kaplan-Meier cumulative incidence rate of ED use was 69.2% (63.9%-74.4%) among those who had unstable housing at baseline and 50.5% (42.1%-59.5%) among those who did not have unstable housing at baseline (log-rank p = 0.004).

Figure 1.

Time to first emergency department (ED) use among a prospective cohort of HIV-positive injection drug users, stratified by unstable housing at baseline.

Predictors of Time to First ED visit (Cox Regression Analyses)

Table 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted relative hazards (RH) for factors associated with time to first ED visit. In the univariate analysis, DTES residence (Hazard Ratio [RH] = 1.37; 95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 1.08 – 1.73; p =0.009), unstable housing (RH = 1.54 [95% CI: 1.21–1.96]; p < 0.001), inability to access needed health services (RH = 2.14 [95% CI: 1.17–3.91]; p < 0.014), and history of physical assault (RH = 1.30 [95% CI: 1.00–1.69]; p =0.05) were each significantly associated with less time to first ED visit. In the multivariate analysis, participants in unstable housing (RH = 1.47 [95% CI: 1.11–1.96]; p = 0.007) and self-reported inability to access needed health services (RH= 2.24 [95% CI: 1.22–4.12]; p = 0.01) were significantly associated with less time to first ED visit.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses of time to first emergency department visit among 428 HIV-positive injection drug users.

| Unadjusted Relative Hazard (RH) | Adjusted** Relative Hazard (RH) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | RH | (95% CI) | p-value | RH | (95% CI) | p-value |

| Age | ||||||

| (Per year old) | 0.99 | (0.98–1.01) | 0.250 | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| (Female vs. male) | 1.10 | (0.89–1.37) | 0.376 | |||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| (Aboriginal vs. other) | 0.94 | (0.76–1.17) | 0.573 | |||

| DTES Residence* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 1.37 | (1.08 – 1.73) | 0.009 | 1.12 | (0.85 – 1.47) | 0.431 |

| Unable to access services* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 2.14 | (1.17 – 3.91) | 0.014 | 2.24 | (1.22 – 4.12) | 0.010 |

| Unstable Housing* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 1.54 | (1.21 – 1.96) | <0.001 | 1.47 | (1.11 – 1.96) | 0.007 |

| Sex Trade Involvement* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 1.28 | (0.94 – 1.73) | 0.118 | |||

| Daily Crack Cocaine Smoking* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 1.22 | (0.98 – 1.52) | 0.075 | |||

| Daily Heroin Injection* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 1.17 | (0.90 – 1.54) | 0.247 | |||

| Daily Cocaine Injection* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 1.22 | (0.85 – 1.75) | 0.273 | |||

| History of Assault* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 1.30 | (1.00 – 1.69) | 0.050 | 1.28 | (0.98 – 1.66) | 0.067 |

| Viral load (copies/mL) † | ||||||

| (per log 10) | 0.99 | (0.91 – 1.07) | 0.807 | |||

| CD4+ count (cells/mm3) † | ||||||

| (Per 100 cells) | 1.01 | (0.97 – 1.06) | 0.634 | |||

| Methadone Use* | ||||||

| (Yes vs. no) | 0.84 | (0.68 – 1.05) | 0.126 | |||

Behaviours refer to activities in the last six months.

Indicates baseline value.

Model was fitted adjusting for all variables significant in unadjusted analyses.

ED Diagnoses & Hospital Admissions

The most common ED diagnoses are presented in Table 3. Of the 2461 visits to the ED, 2242 (91.1%) had diagnosis code data. SSTI such as abscesses and cellulitis accounted for the greatest number of ED visits (17.6%), followed by medical refills and aftercare (17.5%). Substance misuse and overdoses accounted for 6.0% per cent of ED visits.

Table 3.

Most frequent reasons for ED visits among IDU

| (N = 2242) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Reason | n | % |

| Skin and soft tissue infections eg. Abscesses, cellulitis | 394 | (17.6%) |

| Medication refills and aftercare* | 392 | (17.5%) |

| Respiratory infections and disorders | 264 | (11.8%) |

| Wounds, lacerations & contusions | 252 | (11.2%) |

| Gastrointestinal & urological disorders | 203 | (9.1%) |

| Miscellaneous bacterial and viral infections | 191 | (8.5%) |

| Cardiac and circulatory system diseases | 147 | (6.6%) |

| Substance misuse and overdose | 134 | (6.0%) |

| Neurological disorders or seizures | 125 | (5.6%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 69 | (3.1%) |

| Fractures and dislocations | 44 | (2.0%) |

| Other | 27 | (1.2%) |

Aftercare includes wound care & IV antibiotic administration.

Discharge data were obtained for 2381 (96.7%) of the 2461 ED visits. The majority 1778 (74.7%) were discharged from the ED with advice, 419 (17.6%) were admitted to hospital, 93 (3.9%) left the ED without being seen, and 91 (3.8%) were discharged from the ED against medical advice.

DISCUSSION

Our study demonstrates high rates of ED use among a cohort of HIV-positive IDU. Interestingly, living in unstable housing and being unable to obtain needed health care services were both independently associated with time to first ED visit during the study period, whereas baseline CD4 cell count and viral load did not predict ED use. SSTI, including abscesses and cellulitis (17.6%), and medication refills and aftercare (17.5%) accounted for the greatest proportion of ED visits. Of the 2461 visits to the ED, 419 (17.6%) were admitted to hospital.

A key finding of the present study is the independent association between residing in unstable housing environments and shorter time to first visiting the ED. The challenges associated with living in unstable housing may act as a barrier for IDU to access primary care services, as the immediate sustenance needs implicit in being homeless (e.g., daily acquisition of food and shelter) must compete with health care needs.30 Delays in seeking treatment may result in more frequent and lengthy hospital admissions.12, 23, 31 Further, previous studies have clearly demonstrated that unstable housing among IDU is associated with hazardous and unhygienic injecting practices that may also predispose individuals to infection. Unsafe injection practices associated with rushed injections in public places include the use of unclean water sources, decreased sanitization of the skin with alcohol prior to injecting, and the preparation of drugs directly in the barrel of the syringe by adding water and “shaking” without cooking or filtering.32 In our local setting, unstable housing was found to be independently associated with SSTI among IDU who used Vancouver's supervised injection facility.33 This may also help to account for the observation in the present study that SSTI, a common injection-related complication, was the most common ED diagnoses.

The link between ED use and unstable housing is particularly concerning here in Vancouver, Canada, where the number of homeless persons rose by 106% from 2002 to 2005.34 Additionally, there have been recent losses of low-income housing and an increase in homelessness as a result of urban renewal for the 2010 Olympic Winter Games.35 Increased property speculation and increasing property values in the Downtown Eastside neighborhood led to reductions in available low-income housing and a predicted homeless population in excess of 3000 by the start of the 2010 Olympics.34 The high cumulative incidence of ED visits among local IDU and the association with unstable housing indicates a pressing need for affordable housing, especially given the increasing shortage in our setting. Stable living environments can facilitate an individual's ability to stay connected with primary care services and seek care earlier on in disease progression and reduce hospital ED and inpatient service use.36-38 In the ED, case management for unstably housed HIV-positive individuals has also been found to be a successful method in improving adherence to HAART and biological outcomes.39

It is noteworthy that clinical markers of HIV/AIDS disease at baseline, such as CD4 cell count and HIV-1 RNA plasma viral load, were not significantly associated with ED use in the present study. Since baseline CD4 and viral load serves as a significant prognostic indicator of treatment outcome and response to HAART therapy,40-41 recent expansion of HAART coverage and initiation of HAART therapy at higher CD4 counts in our setting may explain somewhat the strong associations with socio-demographic characteristics and injection-related complications as the primary reason for ED use.42-43 This contrasts with ED use patterns in the pre-HAART era when ED presentations frequently related to the acute complications of HIV/AIDS disease, including opportunistic infections.44-45

Inability to access needed health services was also independently associated with time to ED use in multivariate analyses. Though there have been conflicting findings in our setting on the relationship between access to primary care and hospital-based service use, our findings provide support for an association between ED use and a perceived barrier to accessing other needed health care services.1-2, 8 Primary care services that implement an integrated model of care, including harm reduction and drug treatment, may be viewed as less stigmatizing of drug use and prove to be more effective in reducing perceived barriers to health care access.46 One example is supervised injection facilities (SIFs) that integrate harm reduction strategies, including preventative education on sterile injection, with primary care and addiction counseling.46-47 Indeed, integrating wound management care into existing harm reduction services, such as needle exchange programs and SIF, in community settings has been found to be feasible, cost-effective and beneficial for preventing and treating SSTI, the most common presenting ED complaint in our study.46-48 Additionally, previous research has found decreased ED use with methadone maintenance and other drug treatment programs with health care access.49-52 Screening for substance misuse in the ED and referral to harm reduction and drug treatment programs that provide primary care services may therefore prove to be beneficial in this population.

LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. First, we may have underestimated the level of ED use as participants may have sought care at other facilities in the city. However, we did consider the hospital ED that is used by the vast majority of people living in this community.1 Second, the current study relies on self-report of drug use and other stigmatized behaviors (e.g. sexual behaviors) and may be susceptible to socially desirable reporting. In this regard, it is noteworthy that CD4 and viral load information were not susceptible to this concern. Third, although ED usage was ascertained through a linkage to an external database, migration away from the city or other reasons for loss of participants to follow-up may nevertheless introduce some degree of bias into the study results. Fourth, although our cohort includes an estimated 20 per cent of all IDU living in the Downtown Eastside, our sample may not be representative of all IDU in the area. Finally, our study was unable to access follow-up information on health care use after discharge from the ED. Future studies should assess the impact of interventions for this population in the ED on subsequent health care utilization patterns including return to the ED.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, our study documents a high incidence of ED use among HIV-positive IDU. Individuals more likely to visit the ED represented those most severely disadvantaged in terms of housing and access to primary care services, and the most common ED diagnoses were due to preventable injection-related infections. This study indicates that socio-demographic factors and injection-related complications play a major role in ED visits among HIV-positive IDU in the post-HAART era. While expanding use of HAART among IDU is an urgent concern,53-54 the clinical markers of HIV disease status at baseline did not appear to play a role in predicting ED use in this setting.

Acknowledgements

We would particularly like to thank the ACCESS participants for their willingness to be included in the study, as well as current and past ACCESS investigators and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Caitlin Johnston, and Steve Kain for their research and administrative assistance. The study was supported by the US National Institutes of Health and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Thomas Kerr is supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kerr T, Wood E, Grafstein E, et al. High rates of primary care and emergency department use among injection drug users in Vancouver. J Public Health (Oxf) 2005 Mar;27(1):62–66. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Leon H, et al. Hospital utilization and costs in a cohort of injection drug users. Cmaj. 2001;165(4):415–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebo KA, Fleishman JA, Moore RD. Hospitalizations for metabolic conditions, opportunistic infections, and injection drug use among HIV patients: trends between 1996 and 2000 in 12 states. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Dec 15;40(5):609–616. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000171727.55553.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venkat A, Piontkowsky DM, Cooney RR, Srivastava AK, Suares GA, Heidelberger CP. Care of the HIV-positive patient in the emergency department in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Ann Emerg Med. 2008 Sep;52(3):274–285. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.01.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowlton AR, Hoover DR, Chung SE, Celentano DD, Vlahov D, Latkin CA. Access to medical care and service utilization among injection drug users with HIV/AIDS. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2001 Sep 1;64(1):55–62. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00228-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.French MT, McGeary KA, Chitwood DD, McCoy CB. Chronic illicit drug use, health services utilization and the cost of medical care. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1703–1713. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00411-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stein MD, Sobota M. Injection drug users: hospital care and charges. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2001;64:117–210. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00235-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palepu A, Strathdee SA, Hogg RS, et al. The social determinants of emergency department and hospital use by injection drug users in Canada. J Urban Health. 1999 Dec;76(4):409–418. doi: 10.1007/BF02351499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohler NL, Wong MD, Cunningham WE, Cabral H, Drainoni ML, Cunningham CO. Type and pattern of illicit drug use and access to health care services for HIV-infected people. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(Suppl 1):S68–76. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.9985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poundstone KE, R.E. C, Moore RD. Differences in HIV disease progression by injection drug use and by sex in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1115–1123. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruce RD, Altice FL. Clinical care of the HIV-infected drug user. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21(1):149–179. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cunningham CO, Sohler NL, Wong MD, et al. Utilization of health care services in hard-to-reach marginalized HIV-infected individuals. AIDS patient care and STDs. 2007 Mar;21(3):177–186. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleishman JA, Gebo KA, Reilly ED, et al. Hospital and outpatient health services utilization among HIV-infected adults in care 2000-2002. Med Care. 2005 Sep;43(9 Suppl):III40–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000175621.65005.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Josephs JS, Fleishman JA, Korthuis PT, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Emergency department utilization among HIV-infected patients in a multisite multistate study. HIV Medicine. 2010;11:74–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barash ET, Hanson DL, Buskin SE, Teshale E. HIV-infected injection drug users: health care utilization and morbidity. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007 Aug;18(3):675–686. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Joy R, et al. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: the role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2006 Sep 15;84(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strathdee SA, Palepu A, Cornelisse PG, et al. Barriers to use of free antiretroviral therapy in injection drug users. Jama. 1998 Aug 12;280(6):547–549. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strathdee S, Patrick DM, Currie SL, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11:F59–65. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vlahov D, Munoz A, Anthony JC, Cohn S, Celentano DD, Nelson K. Association of drug injection patterns with antibody to human immunodeficiency virus type 1 among intravenous drug users in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):847–856. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drug Situation in Vancouver. Urban Health Research Institute of the British Columbia Centere for Excellence in HIV/AIDS; Vancouver: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.2005/06 Downtown Eastside Community Monitoring Report. 10th Edition. Spring; City of Vancouver: 2007. [March 03, 2010]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wood E, Montaner JS, Li K, Zhang R, et al. Burden of HIV infection among aboriginal injection drug users in Vancouver, British Columbia. Am J Public Health. 2008 Mar;98(3):515–519. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palepu ATM, Leon H, et al. Hospital utilization and costs in a cohort of injection drug users. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2001;165:415–420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood E, Kerr T, Marshall BD, et al. Longitudinal community plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and incidence of HIV-1 among injecting drug users: prospective cohort study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2009;338:b1649. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b1649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wood E, Hogg RS, Lima VD, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and survival in HIV-infected injection drug users. JAMA. 2008 Aug 6;300(5):550–554. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Craib KJ, Spittal PM, Wood E, et al. Risk factors for elevated HIV incidence among Aboriginal injection drug users in Vancouver. Cmaj. 2003 Jan 7;168(1):19–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spittal PM, Craib KJ, Wood E, et al. Risk factors for elevated HIV incidence rates among female injection drug users in Vancouver. Cmaj. 2002 Apr 2;166(7):894–899. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venkat A, Shippert B, Hanneman D, et al. Emergency department utilization by HIV-positive adults in the HAART era. Int J Emerg Med. 2008 Dec;1(4):287–296. doi: 10.1007/s12245-008-0066-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kozak L, DeFrances C, Hall M. National hospital discharge survey: 2004 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Statistics; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV. Health status, health care use, medication use, and medication adherence among homeless and housed people living with HIV/AIDS. Am J Public Health. 2007 Dec;97(12):2238–2245. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nosyk B, Li X, Sun H, Anis AH. The effect of homelessness on hospitalisation among patients with HIV/AIDS. AIDS care. 2007 Apr;19(4):546–553. doi: 10.1080/09540120701235669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wright NM, Tompkins CN, Jones L. Exploring risk perception and behaviour of homeless injecting drug users diagnosed with hepatitis C. Health Soc Care Community. 2005 Jan;13(1):75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lloyd-Smith E, Wood E, Zhang R, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Risk factors for developing a cutaneous injection-related infection among injection drug users: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:405. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eberle M. Homelessness – Cause and Effects, Volume 3: The Costs of Homelessness in British Columbia. [November 20, 2008];Government of British Columbia. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eby D. Still waiting at the altar: Vancouver 2010's on-again, off-again, relationship with social sustainability. Pivot Legal Society and the Impact of the Olympics on Community Coalition. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing First, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2004 Apr;94(4):651–656. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sadowski LS, Kee RA, VanderWeele TJ, Buchanan D. Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically ill homeless adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2009 May 6;301(17):1771–1778. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinez TE, Burt MR. Impact of permanent supportive housing on the use of acute care health services by homeless adults. Psychiatr Serv. 2006 Jul;57(7):992–999. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kushel MB, Colfax G, Ragland K, Heineman A, Palacio H, Bangsberg DR. Case management is associated with improved antiretroviral adherence and CD4+ cell counts in homeless and marginally housed individuals with HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(2):234–242. doi: 10.1086/505212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egger M, May M, Chene G, et al. Prognosis of HIV-1-infected patients starting highly active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative analysis of prospective studies. Lancet. 2007 May 21;360(9327):119–129. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Florence E, Lundgren J, Dreezen C, et al. Factors associated with a reduced CD4 lymphocyte count response to HAART despite full viral suppression in the EuroSIDA study. HIV Med. 2003 Jul;4(3):255–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1293.2003.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lloyd-Smith E, Brodkin E, Wood E, et al. Impact of HAART and injection drug use on life expectancy of two HIV-positive cohorts in British Columbia. AIDS. 2006 Feb 14;20(3):445–450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000206508.32030.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krusi A, Wood E, Montaner J, Kerr T. Social and structural determinants of HAART access and adherence among injection drug users. Int J Drug Policy. 2009 Sep 9;21(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pezzin LE, Fleishman JA. Is outpatient care associated with lower use of inpatient and emergency care? An analysis of persons with HIV disease. Acad Emerg Med. 2003 Nov;10(11):1228–1238. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2003.tb00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Josephs JS, Fleishman JA, Korthuis PT, Moore RD, Gebo KA. Emergency department utilization among HIV-infected patients in a multisite multistate study. HIV Med. 2009;11(1):74–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00748.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Small W, Van Borek N, Fairbairn N, Wood E, Kerr T. Access to health and social services for IDU: the impact of a medically supervised injection facility. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009 Jul;28(4):341–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Small W, Wood E, Lloyd-Smith E, Tyndall M, Kerr T. Accessing care for injection-related infections through a medically supervised injecting facility: a qualitative study. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 Nov 1;98(1-2):159–162. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grau LE, Arevalo S, Catchpool C, Heimer R. Expanding harm reduction services through a wound and abscess clinic. Am J Public Health. 2002 Dec;92(12):1915–1917. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.12.1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pollack HA, Khoshnood K, Blankenship KM, Altice FL. The impact of needle exchange-based health services on emergency department use. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):341–348. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10663.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Laine C, Lin YT, Hauck WW, Turner BJ. Availability of medical care services in drug treatment clinics associated with lower repeated emergency department use. Med Care. 2005;43(10):985–995. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000178198.79329.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gourevitch MN, Chatterji P, Deb N, Schoenbaum EE, Turner BJ. On-site medical care in methadone maintenance: associations with health care use and expenditures. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2007;32(2):143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Turner BJ, Laine C, Yang CP, Hauck WW. Effects of long-term, medically supervised, drug-free treatment and methadone maintenance treatment on drug users’ emergency department use and hospitalization. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(Suppl 5):S457–463. doi: 10.1086/377558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nosyk B, Sun H, Li X, Palepu A, Anis AH. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and hospital readmission: comparison of a matched cohort. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:146. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Celentano DD, Galai N, Sethi AK, et al. Time to initiating highly active antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected injection drug users. AIDS. 2001 Sep 7;15(13):1707–1715. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]