Abstract

Objective

To examine tooth loss and dental caries by sociodemographic characteristics from community-based oral health examinations conducted by dentists in northern Manhattan.

Background

The ElderSmile programme of the Columbia University College of Dental Medicine serves older adults with varying functional capacities across settings. This report is focused on relatively mobile, socially engaged participants who live in the impoverished communities of Harlem and Washington Heights/Inwood in northern Manhattan, New York City.

Materials and Methods

Self-reported sociodemographic characteristics and health and health care information were provided by community-dwelling ElderSmile participants aged 65 years and older who took part in community-based oral health education and completed a screening questionnaire. Oral health examinations were conducted by trained dentists in partnering prevention centres among ElderSmile participants who agreed to be clinically screened (90.8%).

Results

The dental caries experience of ElderSmile participants varied significantly by sociodemographic predictors and smoking history. After adjustment in a multivariable logistic regression model, older age, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic race/ethnicity, and a history of current or former smoking were important predictors of edentulism.

Conclusion

Provision of oral health screenings in community-based settings may result in opportunities to intervene before oral disease is severe, leading to improved oral health for older adults.

Keywords: elderly, oral health, dental caries, tooth loss, ageing, geriatric dentistry

Introduction

While vaunted improvements in the health of the US population have occurred over the last century, the persistence of health disparities between segments of society, notably those defined by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic factors such as education and income, indicates that such improvements have been uneven1. Among the enduring health disparities are those concerned with oral health; social disparities in tooth loss, dental caries, and periodontal disease have consistently been documented both nationally and regionally2-9. Overall, findings indicate that racial/ethnic minorities, impoverished populations, and groups with lower educational attainment suffer worse oral health outcomes than non-Hispanic Whites, wealthier populations, and groups with higher educational attainment10-11.

Throughout the life course, teeth remain at risk for the two most prevalent oral diseases: dental caries and periodontal disease, which are cumulative12. Older adults are at increased risk for root caries because of both increased gingival recession that exposes root surfaces and increased use of medications that produce xerostomia. Approximately 50% of persons aged 75 years and older have root caries affecting at least one tooth, and approximately 25% of older adults have loss of tooth-supporting structures because of advanced periodontal disease10. Without early prevention and control interventions, these progressive conditions can demand extensive treatment to curb infection and restore function13.

Given the vast expansion in the population of US older adults and the challenges of providing supportive care to growing numbers of people, coordinated efforts and continued support from academic research are needed to better ensure more satisfying later years. In particular, minimising the impact of diseases and conditions now prevalent in older adults and improving their quality of life through better oral health as part of overall health and well-being has been championed as part of the healthy ageing agenda14. The ElderSmile programme of the Columbia University College of Dental Medicine (CDM) has adopted an interdisciplinary approach to meet these challenges, which represents a flexible model for the future15. Here we present the clinical findings regarding tooth loss and dental caries obtained from community-based oral health examinations conducted by dentists in northern Manhattan, New York as part of the ElderSmile programme of the CDM.

Material and Methods

Study sites and populations

The ElderSmile clinical programme currently consists of 27 prevention centres, which are located at senior centres and other locations in which older adults gather in the Harlem and Washington Heights/Inwood communities of northern Manhattan, New York City15. The foremost reason that the CDM elected to focus on creating a network of prevention centres was to access a population of older adults that was not centrally interested in obtaining oral health care for painful conditions, in order to intervene before disease is severe. Given ongoing partnership with the prevention centres over time, both older adults who received services and centre directors, who value the programme, help recruit additional participants for subsequent oral health screenings. The prevention centres host a combination of services, including: (1) general presentations and discussions in both English and Spanish of oral health promotion in later life (e.g., potential oral health problems, how to choose oral health care products, and access to oral health care, including transportation issues); (2) demonstrations of brushing and flossing techniques and care of prosthetic devices; and (3) oral cancer and oral health examinations for older adults who elect to participate. Services are provided by two faculty dentists and dental students of the CDM, who were trained by the project director.

The comparison population for this study is adults aged 65 years and older who received a dental examination in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999-2004. In these US national surveys, dental examinations were conducted in the mobile examination centre by trained dentists who were periodically calibrated by the reference dental examiner16. Similar procedures were followed for the ElderSmile dental examinations. In brief, ElderSmile examiners used a non-magnifying mirror and a pen light to assess for tooth loss and dental caries. The examining protocol was based upon the Radike criteria17 with minor modifications, as per the NHANES protocol.

Older adults are enrolled in the ElderSmile programme after participating in the oral health promotion activities and being examined by one of the ElderSmile dentists. After the screening dentist reviews the results of the oral health examination with each patient, the patient has the option of being referred to an ElderSmile community-based treatment centre (if there is no dental home) or to her or his own dentist15. The project coordinator functions as a case manager to better ensure that indicated follow-up is received by the patients, which is currently at 88%.

Study design and measures

The present study is cross-sectional in design and is centrally concerned with baseline data collected during community-based screenings of adults aged 65 years and older who agreed to participate in the ElderSmile programme. Self-reported sociodemographic characteristics and health and health care information were provided by ElderSmile participants who took part in community-based oral health education and completed a screening questionnaire. Oral health screenings were conducted by dentists in partnering prevention centres among ElderSmile participants who agreed to be clinically examined.

The primary outcome measure of interest is the presence or absence of teeth as assessed by an ElderSmile dentist based upon a complete dentition of 28 teeth. Third molars were excluded from the analysis as they are often missing because of reasons other than dental caries or other oral diseases. Secondary outcomes of the study were dental caries. The following conditions were measured and calculated based upon the clinical examinations of ElderSmile participants: (1) DMFT—number of decayed, missing, and filled permanent teeth; (2) DT—number of decayed permanent teeth as assessed by gross lesions clearly visible to the unaided eye (radiographs were not used); (3) MT—number of permanent teeth missing due to caries18; and (4) FT—number of filled permanent teeth. Finally, edentulism is defined as having no natural permanent teeth in the mouth16. No radiographs or probing were involved, which may lead to an underestimation of dental caries but not missing teeth.

Covariates included in the analyses included age group (65-74 years and 75 years and older), gender (men and women), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic), education level (less than high school, high school, more than high school), and smoking history (current smoker, former smoker, and never smoker). These covariates were selected and the categories formed to be consistent with those employed in NHANES 1999-2004 to aid in comparisons between these US national surveys and the ElderSmile programme data.

Statistical analyses

Means and standard deviations were computed for continuous variables and counts and percentages were computed for categorical variables. In addition to descriptive statistics, mean differences across different levels of each characteristic were computed using a two-sample t-test (for two levels) or a one-way analysis of variance (for more than two levels) for continuous variables, and a chi-squared test for categorical variables. Bivariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted with edentulism as the outcome variable, and age, gender, race/ethnicity, education level, and smoking history as the predictor variables. All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.119.

Results

From August, 2006 through March, 2009, a total of 729 older adults aged 65 years or older participated in oral health promotion presentations and discussions and completed a self-reported oral health survey. Of these 729 older adults, 662 (90.8%) were clinically examined by dentists.

Sociodemographic characteristics

As shown in Table 1, two-thirds of the ElderSmile participants were women (65.9%). Although there were fewer participants in the oldest age groups, there was nonetheless representation throughout the age range of 65-69 years to 95 years and older in the ElderSmile programme. Two of every five participants (39.0%) stated that their primary language was Spanish and self-identified as Hispanic (37.4%); another two of every five participants self-identified as non-Hispanic Black. More than half (53.4%) were born outside of the mainland United States, largely in Puerto Rico (18.8%) and the Dominican Republic (14.8%). About a third (32.5%) had earned less than a high school education. While the study is based upon participants in a community-based service delivery programme and is not population-based, the sample is representative of older adults who frequent senior centres in northern Manhattan.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of older adults aged 65 years and older who participated in community-based oral health education and completed a screening questionnaire (N=729): The ElderSmile Programme, New York, NY, August, 2006 to March, 2009

| Characteristic (n1) | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n=728) | ||

| Men | 250 | 34.3 |

| Women | 478 | 65.7 |

| Age in years (n=729) | ||

| 65-69 | 172 | 23.6 |

| 70-74 | 177 | 24.3 |

| 75-79 | 167 | 22.9 |

| 80-84 | 116 | 15.9 |

| 85-89 | 72 | 9.9 |

| 90-94 | 21 | 2.9 |

| 95+ | 4 | 0.6 |

| Primary language (n=728) | ||

| English | 414 | 56.9 |

| Spanish | 284 | 39.0 |

| Other | 30 | 4.2 |

| Race/ ethnicity (n=639) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 108 | 16.9 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 264 | 41.3 |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 28 | 4.4 |

| Hispanic | 239 | 37.4 |

| Place of birth (n=724) | ||

| Mainland United States | 337 | 46.6 |

| Dominican Republic | 107 | 14.8 |

| Puerto Rico | 136 | 18.8 |

| Other | 143 | 19.9 |

| Education (n=701) | ||

| Less than high school | 228 | 32.5 |

| High school | 269 | 38.4 |

| More than high school | 204 | 29.1 |

| Totals | 729 | 100.0 |

Sample sizes (hence denominators used to compare percentages) may vary across characteristics because of missing values.

Health and health care information

About one in 10 (10.3%) ElderSmile participants reported that they currently smoke cigarettes or cigars and nearly a third (32.2%) reported that they were former smokers (see Table 2). The overwhelming majority of participants reported having medical insurance (94.4%) and visiting a medical doctor within the last year (80.9%). In contrast, less than half of participants reported having dental insurance (46.7%) and visiting a dentist within the last year (45.6%). Finally, 60.5% rated the condition of their teeth or mouth as fair (31.8%) or poor (28.7%).

Table 2.

Health and health care information of older adults aged 65 years and older who participated in community-based oral health education and completed a screening questionnaire (N=729): The ElderSmile Programme, New York, NY, August, 2006 to March, 2009

| Characteristic (n1) | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking history2 (n=624) | ||

| Current smoker | 64 | 10.3 |

| Former smoker | 201 | 32.2 |

| Never smoked | 359 | 57.5 |

| Has medical/ health insurance (n=717) | ||

| Yes | 677 | 94.4 |

| No | 40 | 5.6 |

| Last visit to a medical doctor (n=707) | ||

| Less than 1 year | 572 | 80.9 |

| 1-3 years | 58 | 8.2 |

| More than 3 years | 41 | 5.8 |

| Never | 36 | 5.1 |

| Has dental insurance (n=694) | ||

| Yes | 324 | 46.7 |

| No | 370 | 53.3 |

| Last visit to a dentist (n=695) | ||

| Less than 1 year | 317 | 45.6 |

| 1-3 years | 212 | 30.5 |

| More than 3 years | 150 | 21.6 |

| Never | 16 | 2.3 |

| Self-rated condition of teeth or mouth (n=645) | ||

| Excellent | 18 | 2.8 |

| Very good | 151 | 23.4 |

| Good | 86 | 13.3 |

| Fair | 205 | 31.8 |

| Poor | 185 | 28.7 |

| Total | 729 | 100.0 |

Sample sizes (hence denominators used to compare percentages) may vary across characteristics because of missing values.

ElderSmile participants in the former smoker and never smoked categories were determined by dividing the subset of older adults who reported that they do not currently smoke cigarettes or cigars into those who reported that they ever smoked cigarettes or cigars (former smokers) and those who reported that they did not ever smoke cigarettes or cigars (never smokers).

Of the aforementioned access to care measures (having medical insurance, visiting a medical doctor within the last year, having dental insurance, and visiting a dentist within the last year), significant differences by race/ethnicity and educational level were found for dental insurance coverage (Hispanics were more likely to be covered than other racial/ethnic groups) and time since last dental visit (those with more than a high school education were less likely to have visited a dentist in the past year than those with less education). In addition, self-rated condition of the teeth or mouth was examined by race/ethnicity and education level, and non-Hispanic Blacks and those with more than a high school education were more likely to report poor self-rated oral health than other groups (data and analyses are available upon request from the authors).

DMFT Index

As highlighted in bold in Table 3, the dental caries experience of ElderSmile participants varied importantly by certain sociodemographic predictors and especially by smoking history. Indeed, the mean DMFT, mean DT, and mean MT were decidedly higher and the mean FT was decidedly lower for current smokers than for former smokers (whose caries experience was intermediate for all measures) and never smokers (whose caries experience was best for all measures). In effect, those participants who were current smokers lost on average five more teeth than participants who never smoked. As expected in an older adult population, missing teeth (MT)—an indicator of past severe disease--was the major contributor to DMFT with important differences in mean MT found across all sociodemographic characteristics examined. In particular, higher mean MT values were found among participants 75 years and older (vs. 65 to 74 years), women (vs. men), non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics (vs. Whites), and those with less than high school or high school as their highest educational level achieved (vs. more than high school). Other findings of note include that men were at higher risk of current disease than women (e.g., exhibited higher mean DT levels), although there were no important differences found by gender in filled teeth (e.g., mean FT levels were similar at 5.2 for men and 5.0 for women) in this population.

Table 3.

Means and standard errors (SE) of Decayed Filled Missing Teeth (DMFT), Decayed Teeth (DT), Missing Teeth (MT), and Filled Teeth (FT) by age, gender, race/ ethnicity, education level and smoking history of older adults aged 65 years and older (N = 6621) who participated in community-based oral health examinations conducted by dentists: The ElderSmile Programme, New York, NY, August, 2006 to March, 2009

| Characteristic | Mean DMFT (SE) |

p-value3 | Mean DT (SE) |

p-value3 | Mean MT (SE) |

p-value3 | Mean FT (SE) |

p-value3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | ||||||||

| 65-74 | 20.6 (0.3) | 0.19 | 0.9 (0.1) | 0.66 | 14.2 (0.5) | 0.05 | 5.5 (0.3) | 0.04 |

| 75+ | 21.2 (0.3) | 1.0 (0.1) | 15.6 (0.5) | 4.7 (0.3) | ||||

| Gender | ||||||||

| Men | 20.5 (0.4) | 0.14 | 1.4 (0.2) | <0.01 | 13.9 (0.6) | 0.04 | 5.2 (0.4) | 0.66 |

| Women | 21.2 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.1) | 15.4 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.3) | ||||

| Race/ ethnicity | ||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 20.4 (0.5) | 0.09 | 1.2 (0.3) | 0.13 | 8.9 (0.9) | <0.01 | 10.4 (0.7) | <0.01 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 21.2 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.1) | 16.4 (0.6) | 3.9 (0.3) | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Other | 18.4 (1.2) | 1.3 (0.4) | 10.4 (1.5) | 6.8 (0.8) | ||||

| Hispanic | 21.1 (0.4) | 0.7 (0.1) | 16.1 (0.6) | 4.2 (0.3) | ||||

| Education level | ||||||||

| Less than high school | 21.7 (0.5) | 0.02 | 1.0 (0.2) | 0.89 | 17.4 (0.7) | <0.01 | 3.4 (0.3) | <0.01 |

| High school | 21.0 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.1) | 15.5 (0.6) | 4.6 (0.3) | ||||

| More than high school | 20.0 (0.4) | 0.9 (0.1) | 11.4 (0.7) | 7.7 (0.4) | ||||

| Smoking history2 | ||||||||

| Current smoker | 23.0 (0.7) | <0.01 | 1.8 (0.5) | <0.01 | 18.2 (1.2) | <0.01 | 3.0 (0.6) | <0.01 |

| Former smoker | 22.0 (0.4) | 1.0 (0.2) | 15.8 (0.7) | 5.2 (0.5) | ||||

| Never smoked | 20.0 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.1) | 13.5 (0.5) | 5.7 (0.3) | ||||

| Total | 20.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.1) | 14.9 (0.4) | 5.1 (0.2) |

Sample sizes (hence denominators used to compare percentages) may vary across characteristics because of missing values.

ElderSmile participants in the former smoker and never smoked categories were determined by dividing the subset of older adults who reported that they do not currently smoke cigarettes or cigars into those who reported that they ever smoked cigarettes or cigars (former smokers) and those who reported that they did not ever smoke cigarettes or cigars (never smokers).

p-values correspond to testing whether the mean DMFT, DT, MT, and FT is the same across different levels of each characteristic (age, gender, etc.) Mean differences between groups were computed using a chi-squared test.

Edentulism

To better understand levels of and predictors of edentulism in the ElderSmile participants, we first compared results obtained in this community-based sample to those obtained in a nationally representative sample, namely, NHANES 1999-2004 (Table 4). While overall levels of edentulism of adults aged 65 years and older were lower in the ElderSmile sample (19.5%) than in the US national sample (27.3%), the results by sociodemographic characteristics and smoking history were showed similar trends in the two populations.

Table 4.

Edentulism1 by age, gender, race/ ethnicity, education level and smoking history of older adults aged 65 years and older who participated in community-based oral health examinations conducted by dentists (N=662): The ElderSmile Programme, New York, NY, August, 2006 to March, 2009 and seniors 65 years and older in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination, 1999-20042

| Characteristic | % Edentulism in ElderSmile3 | % Edentulism in NHANES3 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 65-74 | 17.0 | 23.9 |

| 75+ | 21.8 | 31.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 19.4 | 24.4 |

| Women | 19.6 | 29.3 |

| Race/ ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 8.7 | 26.1 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 21.8 | 32.8 |

| Hispanic4 | 24.3 | 23.9 |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 27.9 | 43.3 |

| High school | 19.2 | 28.3 |

| More than high school | 11.5 | 13.6 |

| Smoking history5 | ||

| Current smoker | 30.0 | 49.7 |

| Former smoker | 22.1 | 28.7 |

| Never smoked | 14.8 | 21.7 |

| Total | 19.5 | 27.3 |

No natural permanent teeth.

Source: Table 68 in Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics, 2007: 1-92. (Vital and health statistics; series 11; no. 248.)

Sample sizes (hence denominators used to compare percentages) may vary across characteristics because of missing values.

Mexican American for NHANES.

ElderSmile participants in the former smoker and never smoked categories were determined by dividing the subset of older adults who reported that they do not currently smoke cigarettes or cigars into those who reported that they ever smoked cigarettes or cigars (former smokers) and those who reported that they did not ever smoke cigarettes or cigars (never smokers).

Finally, we examined findings regarding edentulism within the ElderSmile sample using bivariable and multivariable logistic regression (Table 5). Even after adjustment for the other predictors in the model, older age, non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic race/ethnicity, and a history of current or former smoking were important predictors of edentulism; more than a high school education level was protective against edentulism, but was not statistically significant in the multivariable model.

Table 5.

Unadjusted and adjusted1 Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) of edentulism2 with covariates of age, gender, race/ ethnicity, education level and smoking history of older adults aged 65 years and older who participated in community-based oral health examinations conducted by dentists (N=662): The ElderSmile Programme, New York, NY, August, 2006 to March, 2009

| Characteristic | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) |

| Gender | ||

| Men | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Women | 1.05 (0.66, 1.68) | 1.11 (0.68, 1.81) |

| Race/ ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 2.64 (1.19, 5.86) | 2.42 (1.06, 5.56) |

| Non-Hispanic Other | 0.49 (0.06, 4.11) | 0.62 (0.07, 5.40) |

| Hispanic | 3.14 (1.42, 6.94) | 3.06 (1.28, 7.30) |

| Education level | ||

| Less than high school | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| High school | 0.67 (0.41, 1.11) | 0.77 (0.45, 1.33) |

| More than high school | 0.37 (0.21, 0.67) | 0.57 (0.29, 1.10) |

| Smoking history3 | ||

| Current smoker | 2.53 (1.32, 4.83) | 3.00 (1.50, 6.02) |

| Former smoker | 1.59 (0.97, 2.58) | 1.81 (1.09, 3.02) |

| Never smoked | 1.00 | 1.00 |

Multivariable logistic regression adjusting for age, gender, race/ ethnicity, education level, and smoking history.

No natural permanent teeth.

ElderSmile participants in the former smoker and never smoked categories were determined by dividing the subset of older adults who reported that they do not currently smoke cigarettes or cigars into those who reported that they ever smoked cigarettes or cigars (former smokers) and those who reported that they did not ever smoke cigarettes or cigars (never smokers).

Discussion

This study contributes to a better understanding of the oral health and health care of community-dwelling older adults who were examined at senior centres and other venues where older adults gather, rather than those who were seeking oral health care per se. A key finding is that the study participants were twice as likely to have health insurance and recent visits over dental insurance and recent visits, pointing to the need for policy reform in order to ensure that older adults receive indicated oral health care services.

Even in socially disadvantaged communities such as Harlem and Washington Heights/Inwood in northern Manhattan, New York City, appreciable variation in levels of tooth loss and dental caries experience was evident among participants in the community-based screenings of the ElderSmile programme. Moreover, while social disparities in edentulism were evident in both the ElderSmile and NHANES 1999-2004 (US national) samples, the overall level of edentulism was lower in the ElderSmile sample (19.5%) than in the US national sample (27.3%). Ahluwalia et al. found an even lower level of edentulism (9.0%) among community-dwelling older adults who regularly utilise dental services in northern Manhattan20. It may be that the social support evidenced by gathering with other adults at senior centres and the affordable clinics available in these communities through the CDM and may aid in ensuring that these segments of the population have more regular dental care than other similarly disadvantaged populations.

Factors operating at the societal, community, interpersonal, and individual levels may support or hinder older adults in realising oral health, including oral health care access and utilisation, which is consistent with social-ecological theories for describing and understanding multilevel interventions21-23. According to Trickett, “Multilevel community-based culturally situated interventions are those that integrate a multi-layered ecological conception of the community context, a commitment to working in collaboration or partnership with groups and settings in the local community, and an appreciation of how intervention efforts are situated in local culture and context22, p. 257.”

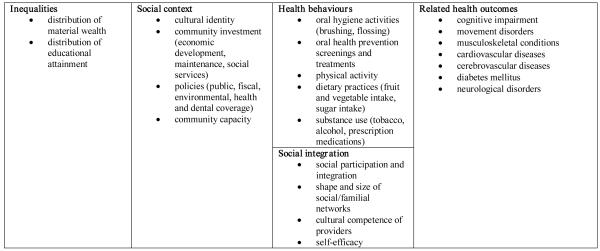

With regard to the segment of older adults in northern Manhattan who participated in the present study, it is possible that their social participation and integration in activities of the senior centres countered societal ideologies such as ageism and racism and enabled them to take advantage of services including health promotion activities and dental care that positively enhanced their oral health outcomes. The complex, multilevel relationships just delineated which determine tooth loss and dental caries in older adults are captured in the Ecological Model of Social Determinants of Oral Health for Older Adults presented as Figure 1, as adapted from a previous conceptual model24.

Figure 1. Ecological Model of Social Determinants of Oral Health for Older Adults.

This ecological model for thinking about pathways whereby social determinants at various scales (societal, community, and interpersonal) influence oral health and related health outcomes for both individuals and populations of older adults is adapted from a conceptual model titled, “Social Determinants of Health and Environmental Health Promotion” that first appeared in Northridge ME, Sclar E, and Biswas P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J Urban Health 2003; 80: 556-568. Note that these factors operate across the life course from pregnancy through older age to affect oral health and related health outcomes (see, e.g., Fisher-Owens SA, Barker JC, Adams S, Chung LH, Gansky SA, Hyde S, Weintraub JA. Giving policy some teeth: routes to reducing disparities in oral health. Health Aff 2008; 27: 404-412).

As depicted in this framework, oral health in older adults is due to the lifelong accumulation of advantageous and disadvantageous experiences at multiple scales, from the micro-scale of the mouth to the societal scale that involves inequalities in the distribution of material wealth and educational attainment. A corollary is that certain factors at the neighbourhood scale (e.g., access to services such as health and dental care), interpersonal scale (e.g., health behaviours such as oral hygiene activities), and individual scale (e.g. related health outcomes such as cognitive impairment) may be particularly important in influencing oral health outcomes for older adults such as tooth loss, dental caries, and periodontal disease, and may be useful targets for intervention. Note that this model is compatible with the life course perspective, as both view oral disease as cumulative12,25. Systems science holds promise in integrating multiscalar and dynamic processes to understand places to intervene to improve oral health and health care over time and place26.

A growing body of literature points to changes over time and the diversity of the older adult population with regard to their oral health and health care experiences. In a previous study conducted among US older adults attending senior centres using data from the National Survey of Oral Health in US Employed Adults and Seniors:1985-1986, Marcus et al. found that those with the least education or income and those who lived in New England or the Northeast had the fewest number of teeth27. In the Florida Dental Care Study, 19% of those screened by telephone were found to be edentulous, but the subjects were younger (45 years and older) than those in the present study (65 years and older) 28. At the US state level, there is marked variation in the percentage of older adults who are edentulous: 13% in California and Hawaii compared to 42% in Kentucky and West Virginia29.

Samson and colleagues compared the oral health status among institutionalised older adults in Norway living in the same five nursing homes over a period of 16 years30. They concluded that as more people retain their teeth throughout the life course and the prevalence of oral diseases increases among institutionalised older adults, their objective need for dental care is greater in contemporary than in the earlier time periods. Loesche and colleagues examined the oral health of four groups of older adults across the following settings: (1) lived in a residential retirement home or in the community; (2) sought dental care at a Veterans Affairs (VA) Dental Outpatient Clinic; (3) resided in a VA long-term care facility; and (4) recently admitted to a VA acute care ward with a diagnosis of cerebral vascular disease or other neurologic problem31. Findings were that independent living older adults had better oral health than dependent living older adults and healthy persons had excellent oral health whereas the sickest persons were either edentulous or had many missing teeth. Another study of 650 long-term care residents of six VA nursing home care units found moderate levels of untreated dental caries and periodontal disease and significant tooth loss which increased with age32. The authors identified a need for preventive therapy, restorative dentistry, conservative periodontal therapy, and prosthodontic care for these residents.

The oral health status of particular underserved communities of older adults has been reported, including that of rural residents33, Brazilian adults34, and Canadian Inuits35. While barriers and facilitators to oral health care for older adults have been identified36-38, the reasons various groups of older adults seek or do not seek oral health care at different stages of their lives are complex. For instance, a census survey designed for a Canadian municipal home for the aged found that among the dentate population, dental insurance was associated with higher oral health status, but its effect on the edentulous population depended upon age and the pattern of visiting the dentist39. Our findings are consistent with the results of these and other investigators who have analysed the importance of dental caries, socioeconomic status, and smoking history into very old age40.

Strengths and limitations

Among the strengths of this study is that it is part of the larger ElderSmile programme at the CDM. This context permitted the leveraging of resources in the form of faculty and students to assist in the dental screenings and health promotion activities, and better ensured high cooperation rates for the involved community partners, given ongoing relationships between the CDM and the administrators and staff at the involved prevention sites. Among the limitations are that the assessments reported here were restricted by the field nature of the study. Further, older adults who were home-bound or institutionalised were not included in the study. Finally, it is an assumption of the index that MT represents teeth missing due to caries only, and does not take into account periodontal disease and trauma18.

Conclusion

The major oral health outcomes in older adults (tooth loss, dental caries, and periodontal disease) usually progress slowly, are chronic in nature, and cannot be fully understood in terms of the reductionist concept of well-defined disease entities41. In concert with the community engagement perspective, a flexible approach has been adopted by the ElderSmile programme of the CDM that involves oral health evaluation at partnering sites, referral for treatment where indicated to community providers, and case management services in order to meet the oral health and health care needs of different segments of the population15. Findings from the baseline assessments conducted at the prevention centres demonstrated that the dental caries experience of ElderSmile participants varied significantly by sociodemographic predictors and smoking history. Challenges remain in linking and enhancing the use of health promotion and disease prevention education and services by older adults and their providers, and in integrating oral health and health care into other health promotion and service programmes across the life course.

Human participant protection

Appropriate Columbia University institutional review board and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act safeguards were followed.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, Stella and Charles Guttman Foundation, and The Jean & Louis Dreyfus Foundation, Inc. for their financial support of the project The ElderSmile Dental Network: Delivering Dental Services to the Elderly in Northern Manhattan, which provided major funding for the educational and screening components of the ElderSmile programme. ME Northridge and F Ue were supported in conducting the analyses for this paper by a development grant from the Department of Sociomedical Sciences, Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University (grant 4-25917). M.E. Northridge was supported in the conceptualisation and writing of this paper by Legacy (contract 7-70983). The authors were supported in revising this paper by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (grant 1R21DE021187-01).

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services . Healthy People 2010: Understanding and Improving Health. 2nd ed US Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly JE, Van Kirk LE. Periodontal disease in adults. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, Maryland: 1965. pp. 1–30. (Vital and health statistics; series 1; no. 12.) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelly JE, Harvey CR. Basic data on dental examination findings of persons 1-74 years. United States, 1971-1974. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, Maryland: 1979. pp. 1–33. (Vital and health statistics; series 11; no. 11.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oral Health Coordinating Committee, Public Health Service Toward improving the oral health of Americans: an overview of oral health status, resources, and care delivery. Public Health Rep. 1993;108:657–672. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caplan DJ, Weintraub JA. The oral health burden in the United States: a summary of recent epidemiologic studies. J Dent Educ. 1993;57:853–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White BA, Caplan DJ, Weintraub JA. A quarter century of changes in oral health in the United States. J Dent Educ. 1995;59:19–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Barker LK, Canto MT, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for dental caries, dental sealants, tooth retention, edentulism, and enamel fluorosis--United States, 1988-1994 and 1999-2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2005;54:1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burt BA, Eklund SA. Dentistry, Dental Practice, and the Community. 6th ed Elsevier Saunders; St. Louis, Missouri: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zabos GP, Northridge ME, Ro MJ, Trinh C, Vaughan R, Howard J Moon, Lamster I, Bassett MT, Cohall AT. Lack of oral health care for adults in Harlem: a hidden crisis. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:49–52. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services (US DHHS) Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General. National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; Rockville, Maryland: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Borrell LN. Social disparities in oral health and health care for older adults. In: Lamster IB, Northridge ME, editors. Improving oral health for the elderly: an interdisciplinary approach. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Northridge ME, Lamster IB. A life course approach to preventing and treating oral disease. Soz Praventivmed. 2004;49:299–300. doi: 10.1007/s00038-004-4040-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamster IB. Oral health care services for older adults: a looming crisis. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:699–702. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albert SM. The aging US population. In: Lamster IB, Northridge ME, editors. Improving oral health for the elderly: an interdisciplinary approach. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marshall S, Northridge ME, De La Cruz L, et al. ElderSmile: a comprehensive approach to improving oral health for older adults. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:595–599. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.149211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dye BA, Tan S, Smith V, et al. Trends in oral health status: United States, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2007. pp. 1–92. (Vital and health statistics; series 11; no. 248.) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Dental Association Proceedings of the Conference on the Clinical Testing of Cariostatic Agents; October 1968; Chicago: Council on Dental Research and Council on Dental Therapeutics, American Dental Association; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein H, Palmer CE, Knutson JW. I. Dental status and dental needs of elementary school children. Public health Rep. 1938;53:751–765. [Google Scholar]

- 19.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS/STAT 9.1 User’s Guide. SAS Institute, Inc.; Cary, NC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahluwalia KP, Cheng B, Josephs PK, Lalla E, Lamster IB. Oral disease experience of older adults seeking oral health services. Gerodontology. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2009.00311.x. doi:10.1111/j.1741-2358.2009.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trickett EJ, Schensul JJ. Summary comments: multi-level community based culturally situated interventions. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:377–381. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9237-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trickett EJ. Multilevel community-based culturally situated interventions and community impact: an ecological perspective. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:257–266. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Northridge ME, Sclar E, Biswas P. Sorting out the connections between the built environment and health: a conceptual framework for navigating pathways and planning healthy cities. J Urban Health. 2003;80:556–568. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jtg064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher-Owens SA, Barker JC, Adams S, Chung LH, Gansky SA, Hyde S, Weintraub JA. Giving policy some teeth: routes to reducing disparities in oral health. Health Aff. 2008;27:404–412. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meadows DH. Thinking in systems: a primer. Chelsea Green Publishing; White River Junction, VT: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marcus SE, Kaste LM, Brown LJ. Prevalence and demographic correlates of tooth loss among the elderly in the United States. Spec Care Dentist. 1994;14:123–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1994.tb01117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert GH, Duncan RP, Dolan TA, Foerster U. Twenty-four month incidence of root caries among a diverse group of adults. Caries Res. 2001;35:366–375. doi: 10.1159/000047476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Public health and aging: retention of natural teeth among older adults—United States, 2002. MMWR. 2003;52:1226–1229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samson H, Strand GV, Haugejorden O. Change in oral health status among the institutionalized Norwegian elderly over a period of 16 years. Acta Odontol Scand. 2008;66:368–373. doi: 10.1080/00016350802378654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Loesche WJ, Abrams J, Terpenning MS, et al. Dental findings in geriatric populations with diverse medical backgrounds. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80:43–54. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(95)80015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weyant RJ, Jones JA, Hobbins M, et al. Oral health status of a long-term-care, veteran population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:227–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vargas CM, Yellowitz JA, Hayes KL. Oral health status of older rural adults in the United States. J Am Dent Assoc. 2003;134:479–486. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silva DD, Sousa da LM, Wada RS. Oral health in adults and the elderly in Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2004;20:626–631. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2004000200033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galan D, Odlum O, Brecx M. Oral health status of a group of elderly Canadian Inuit (Eskimo) Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1993;21:53–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1993.tb00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dolan TA, Atchison KA. Implications of access, utilization and need for oral health care by the non-institutionalized and institutionalized elderly on the dental delivery system. J Dent Educ. 1993;57:876–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kiyak HA, Reichmuth M. Barriers to and enablers of older adults’ use of dental services. J Dent Educ. 2005;69:975–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Macek MD, Cohen LA, Reid BC, Manski RJ. Dental visits among older U.S. adults, 1999: the roles of dentition status and cost. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1154–1162. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0375. quiz 1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adegbembo AO, Leake JL, Main PA, et al. The influence of dental insurance on institutionalized older adults in ranking their oral health status. Spec Care Dentist. 2005;25:275–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.2005.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorstensson H, Johansson B. Why do some people lose teeth across their lifespan whereas others retain a functional dentition into very old age. Gerodontology. 2010;27:19–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-2358.2009.00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eriksen HM, Dimitrov V. Ecology of oral health: a complexity perspective. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:285–290. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0722.2003.00053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]