Abstract

Cemento-osseous dysplasias are a group of disorders known to originate from periodontal ligament tissue and involve, essentially, the same pathological process. They are usually classified into three main groups: periapical, florid, and focal cemental dysplasias depending on their extent and radiographic appearances. Radiographically, florid cementoosseous dysplasia (FCOD) appears as dense, lobulated masses, often symmetrically located in various regions of the jaws. The best management for the asymptomatic FCOD patient consists of regular recall examinations with prophylaxis. The management of the symptomatic patient is more difficult. A case of FCOD occurring in a 52-year-old edentulous Korean female is reported which is rare with regard to race and sex.

Keywords: Florid Cemento-Osseous Dysplasia, Cone-Beam Computed Tomography, Cementoma

The term florid cemento-osseous dysplasia (FCOD) refers to a group of fibro-osseous (cemental) exuberant lesions with multi-quadrant involvement.1 FCOD is a rare condition presenting in the jaw. This lesion is the most commonly found in middle-aged black women, although it also may occur in Caucasians and Asians,2,3 and has been entitled as sclerosing osteitis, multiple enostoses, diffuse chronic osteomyelitis, and gigantiform cementoma. In some cases, a familial trend has been observed.4-7 The process may be totally asymptomatic and, in such cases, the lesion is detected on radiographs for some other purposes.8 Symptoms such as dull pain or drainage are almost always associated with exposure of sclerotic calcified masses in the oral cavity. This may occur as the result of progressive alveolar atrophy under a denture or after extraction of teeth in the affected area.9

FCOD lesions have a striking tendency toward bilateral, often quite symmetrical, location, and it is not unusual to find extensive lesions in all four posterior quadrants of the jaw.10

Radiographically, FCOD appears as dense, lobulated masses and often symmetrically located in various regions of the jaws. Computed tomography (CT) is useful for the evaluation of this lesion because of its ability to acquire axial, sagittal, and frontal views.

This report describes a case of a patient who was diagnosed with florid cement-osseous dysplasia on the basis of clinical, radiographic, and histological findings.

Case Report

A 52-year-old Korean female visited Seoul Veterans Hospital with a complaint of acute pain and gingival swelling on the right mandibular molar region. The patient was systemically healthy and her physical examination showed no significant abnormality. Intraoral examination revealed completely edentulous state. The overlying gingiva of the right mandibular area showed swelling and inflammation clinically. On palpation, bilateral buccal bony expansion was noted on the posterior mandible and maxilla (Fig. 1). She had a complete denture, however her denture was out of use due to the gingival swelling and pain.

Fig. 1.

Bilateral buccal bone expansion on posterior quadrant of the maxilla.

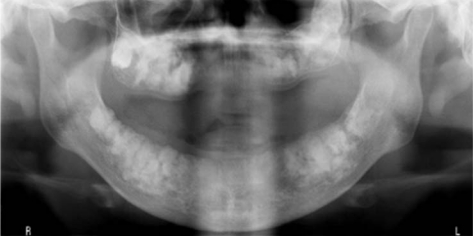

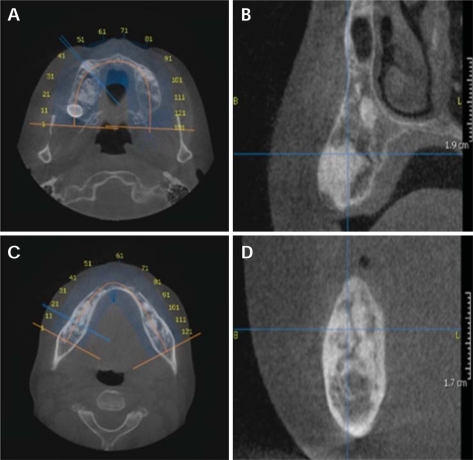

Panoramic radiograph showed diffuse, lobular, and irregularly shaped radiopacities or cotton-wool appearance throughout the alveolar process of both quadrants of the maxilla and mandible. Multiple sclerotic masses with radiolucent borders were found in the maxilla and mandible, confined within the alveoli at the level corresponding to the roots of the teeth, above the inferior alveolar canal (Fig. 2). Cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) (KaVo 3D eXam, KaVo, Biberach, Germany) images also revealed large radiopaque shadow extending into the mandible and maxilla. The bucco-lingual aspects of the lesions could be visualized on the CBCT images, which demonstrated the relationship of the bony lesions to the cortical plates in the bucco-lingual dimension. High density masses were surrounded by a low density layer. The superior border of the mandibular canal was intact (Fig. 3). Some lesions appeared larger and connected with the buccal and lingual cortical plates. On the parasagittal reformatted images at this level, bucco-lingual cortical expansion was observed (Figs. 3B and D). The radiographic appearance varied from radiolucent to mixed lesions or rather radiopaque masses.

Fig. 2.

Panoramic radiograph shows diffuse, lobular, irregularly shaped radiopacities or cotton-wool appearance throughout the alveolar process of the quadrants of the edentulous maxilla and mandible.

Fig. 3.

A. Axial CT image shows high density masses in maxilla premolar-molar regions. B. Coronal CT image show high density masses and their relationship to radiopaque masses and bilateral extensions into the floor of the antrum. C. Axial CT image shows high density masses of the posterior quadrant of the mandible. D. Coronal CT image shows high density masses are surrounded by a low density layer.

Under local anesthesia, incision and surgical curettage was performed on the right mandibular posterior area. Irregular bony defects and inflammatory fibrous tissue were seen in the operation field.

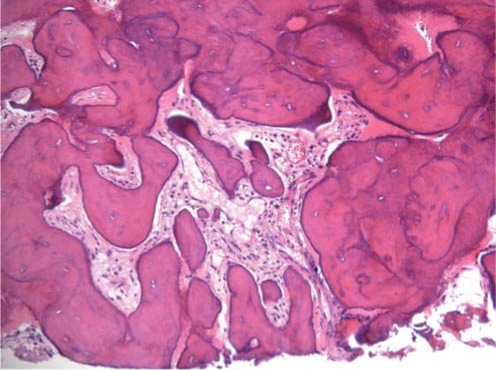

After curettage, the swelling was decreased and the patient could wear her denture. Biopsy was performed and it was histologically diagnosed with cemento-osseous dysplasia. Histological finding of this lesion showed the formations of dense sclerotic calcified cementum-like masses. The lesion was composed of cementum-like substances characterized by islands of calcified deposits and areas of loose fibro-collagenous stroma, which showed the evidence of proliferation. The cementum-like substances mainly showed acellular structure (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

There are thick, confluent curvilinear trabeculae with little fibrotic stroma. This lesion showed formation of dense sclerotic calcified cementum-like masses. Periphery of the lesions showed globular or ovoid structures of cementoid appearance involved by thin fibrous tissue (H&E stain, ×200).

The patient's mother and twin daughters had similar lesions in the jaws. The familial history and histological findings suggested a diagnosis of familial gigantiform cementoma. The patient of the present case has been followed up over the last 12 month and FCOD has remained asymptomatic.

Discussion

Exuberant fibro-osseous lesions occurring in multi-quadrants of the jaws were designated as gigantiform cementomas or familial multiple cementomas in the first edition of the world Health Organization's Histological Typing of Odontogenic Tumor, Jaw cysts and Allied Lesions.11 However, the etiopathogenesis has not been clear.

Our case was diagnosed with FCOD based on the clinical, histologic, and radiographic features. FCOD should be differentiated from Paget's disease, chronic diffuse osteomyelitis, and Gardner's syndrome. FCOD has no other skeletal change, skin tumors, and dental anomalies. Thus FCOD can be differentiated from Gardner's syndrome. Paget's disease is polyostotic and shows the raised alkaline phosphatase level which is not a consistent feature of FCOD. Chronic diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis is not confined to tooth bearing areas. It is a primary inflammatory condition of mandible with cyclic episodes of unilateral pain and swelling. The affected lesion of the mandible exhibits a diffuse opacity with poorly defined borders.

FCOD is a reactive, non-neoplastic process confined to tooth-bearing areas of the jaws that is found most frequently in middle-aged and older black women. Melrose et al reported a study of 34 cases of such lesions, of which 32 were black women (in a predominantly Caucasian population) with mean age of 42 years.12 The definite female gender predilection of the condition is unclear.2,3 In the present case, the patient was a 52-year-old Korean female; it was rare in regard to the race and gender.

FCOD may be familial with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. However, there were only few examples in the literatures in which the familial pattern had been confirmed.10,13,14 In this case, the patient's mother and twin daughters had similar lesions in the jaw, and they were diagnosed with familial gigantiform cementoma in other clinic, however the lesions were focal without pain and any other symptom.

Conventional radiograph, which exhibit multi-quadrant diffuse radiopaque masses in the tooth-bearing areas of the jaws, plays an important role in the diagnosis for asymptomatic FCOD patients. These radiographic features, though not pathognomonic, are helpful in establishing the diagnosis. The CT findings of the lesion have been previously reported.10 Axial CT images clearly showed the location and extent of the lesion, especially in the maxilla. The expansion of the cortical bone was clearly evaluated on the CT images even though it was slight.

The current methods of management of FCOD are not discussed satisfactorily. The onset of the symptom is usually the sign of inflammation. In such cases, tooth can be managed endodontically. Extraction is not recommended due to the poor socket healing from the impaired blood circulation in the affected area of the bone. Extensive surgical resection and saucerization are proposed as treatment options when lesions become extensive and symptomatic.15,16 In this case, surgical resection and saucerization were performed due to the symptoms of the pain and gingival swelling on the edentulous area.

References

- 1.Ong ST, Siar CH. Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia in a young Chinese man. Case report. Aust Dent J. 1997;42:404–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.1997.tb06086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyake M, Nagahata S. Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia. Report of a case. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;28:56–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waldron CA. Fibro-osseous lesions of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1985;43:249–262. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(85)90283-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cannon JS, Keller EE, Dahlin DC. Gigantiform cementoma: report of two cases (mother and son) J Oral Surg. 1980;38:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oikarinen K, Altonen M, Happonen RP. Gigantiform cementoma affecting a Caucasian family. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:194–197. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coleman H, Altini M, Kieser J, Nissenbaum M. Familial florid cemento-osseous dysplasia - a case report and review of the literature. J Dent Assoc S Afr. 1996;51:766–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Toffanin A, Benetti R, Manconi R. Familial florid cementoosseous dysplasia: a case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000;58:1440–1446. doi: 10.1053/joms.2000.16638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gariba-Silva R, Sousa-Neto MD, Carvalho JR, Jr, Saquy PC, Pecora JD. Periapical cemental dysplasia: case report. Braz Dent J. 1999;10:55–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Said-al-Naief NA, Surwillo E. Florid osseous dysplasia of the mandible: report of a case. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1999;20:1017–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beylouni I, Farge P, Mazoyer JF, Coudert JL. Florid cementoosseous dysplasia: report of a case documented with computed tomography and 3D imaging. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:707–711. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90039-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pindborg J, Kramer I, Torloni H. Histological typing of odontogenic tumors, jaws cysts and allied lesions. Geneva: WHO; 1971. WHO International histological classification of tumors series No.5; pp. 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melrose RJ, Abrams AM, Mills BG. Florid osseous dysplasia. A clinical-pathologic study of thirty-four cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1976;41:62–82. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(76)90254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oikarinen K, Altonen M, Happonen RP. Gigantiform cementoma affecting a Caucasian family. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;29:194–197. doi: 10.1016/0266-4356(91)90038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young SK, Markowitz NR, Sullivan S, Seale TW, Hirschi R. Familial gigantiform cementoma: classification and presentation of a large pedigree. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;68:740–747. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(89)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.MacDonald-Jankowski DS. Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia: a systematic review. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2003;32:141–149. doi: 10.1259/dmfr/32988764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider LC, Mesa ML. Differences between florid osseous dysplasia and chronic diffuse sclerosing osteomyelitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1990;70:308–312. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(90)90146-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]