Abstract

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is the most severe form of leishmaniasis and is responsible for most Leishmania-associated deaths. VL represents a serious public health problem that affects many countries. The immune response in leishmaniasis is very complex and is poorly understood. The Th1 versus Th2 paradigm does not appear to be so clear in visceral leishmaniasis, suggesting that other immunosuppressive or immune-evasion mechanisms contribute to the pathogenesis of VL. It has been demonstrated that generation of adenosine, a potent endogenous immunosuppressant, by extracellular enzymes capable to hydrolyze adenosine tri-nucleotide (ATP) at the site of infection, can lead to immune impairment and contribute to leishmaniasis progression. In this regard, this paper discusses the unique features in VL immunopathogenesis, including a possible role for ectonucleotidases in leishmaniasis.

1. Introduction

Parasites that belong to the genus Leishmania are among the most diverse human pathogens, both in terms of geographical distribution and in the variety of infection-induced clinical manifestations they generate. Of the 88 countries affected by leishmaniasis, 72 are classified as developing countries, including 13 of the least developed countries. Despite the widespread distribution of leishmaniasis, 90% of VL cases occur in just five countries: Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Sudan, and Brazil [1]. Leishmania are obligate intracellular protozoan parasites transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies. Flagellated promastigotes injected by sand fly bites replicate as intracellular amastigote stages inside mononuclear phagocytic cells of mammalian hosts [2, 3]. The epidemiology of leishmaniasis is diverse, with 20 Leishmania species that are pathogenic in humans and 30 sand fly species that have been identified as vectors [1]. This range of species variability culminates in different symptomatology and clinical manifestations that can be classified into two broad disease presentations: cutaneous leishmaniasis and VL [4].

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is caused by Leishmania donovani (L. donovani) in the Indian subcontinent, Asia, and Africa and by Leishmania infantum (L. infantum) or Leishmania chagasi (L. chagasi) in the Mediterranean region, southwest and central Asia, and South America; however, other species, such as Leishmania amazonensis (L. amazonensis) in South America, are occasionally viscerotropic [5, 6]. VL is the most severe form of leishmaniasis and is responsible for most deaths caused by leishmaniasis. The disease commonly affects the liver, spleen, and lymph nodes. The pathophysiology of the disease is characterized by the onset of symptoms of a persistent systemic infection, including loss of appetite, weight loss, intermittent fever, fatigue, and exhaustion. The incubation period usually ranges from two to six months. Parasite dissemination occurs via the vascular, lymphatic, and mononuclear phagocyte systems and results in bone marrow infiltration, hepatosplenomegaly, and lymphadenopathy [7, 8].

In VL, the immune response is closely related to disease progression and the development of clinical manifestations. The syndromes and causative mediators are typical of a slowly developing systemic inflammatory response syndrome with multiorgan failure. The absence of parasite actions or products that would harm the host cells or tissues is a further indication that the systemic pathogenicity of VL is dependent on the host response [9].

2. Immune Response in Visceral Leishmaniasis: The Th1 versus Th2 Paradigm

Cytokine production and the subsequent stimulation or inactivation of certain immune cells in the early stages of an infection essentially determines the type of immune response [10]. The complexity of the immunological events triggered during active VL and the relevance of the segregation of human immune responses during VL into type 1 and type 2 still remain unclear. Several studies have identified that the major immunologic dysfunction observed in VL is the inability of T cells to produce IL-2 and IFN-γ upon stimulation with Leishmania antigens and to activate macrophages and kill Leishmania parasites. Analysis of Th1 and Th2 cell-associated cytokines in peripheral blood samples from patients with L. donovani-induced VL showed reduced IFN-γ levels and increased IL-4 levels in comparison to healthy patients in the control group [11].

Recent data have challenged the simplicity of Th1 versus Th2 model and revealed further complexities in cytokine regulation and the mechanisms of acquired resistance and immune escape [3]. For some cases of VL, it appears that the immune response is a mixed Th1 and Th2 type. In patients with VL, although the production of type 1 cytokines was not depressed, cells appeared to be unresponsive to stimulation with type 1 cytokines [10]. Increased production of multiple cytokines and chemokines in VL patients was also observed; the response was predominately proinflammatory, as indicated by the elevated plasma levels of IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-15, IFN-γ-inducible protein-10 (IP-10), monokine induced by IFN-γ (MIG), IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [2, 12]. Gene expression analysis in an in vitro model, using human monocyte-derived macrophages (MDMs) challenged with L. chagasi promastigotes that were subsequently cocultured with or without Leishmania-naïve autologous T-cells, found that the initial encounter between L. chagasi and cells of the innate and adaptive immune system primarily stimulated type 1 immune cytokine responses. Type 1 cytokine responses were produced despite a lack of classical macrophage activation, suggesting that the local microenvironment at the site of parasite inoculation may determine the initial course of T-cell differentiation [13].

Investigations into the mechanisms underlying the immunosuppression observed during acute VL have demonstrated defective antigen-specific proliferation and IFN-γ responses [14], which suggest that the parasites suppress macrophage microbicidal responses, and IFN-γ signaling pathways [15] at the earliest stages of infection. Also supporting the absence of a clear Th1 versus Th2 dichotomy in VL is the observation that inhibition of Th1 cytokines in a murine model of L. chagasi-induced VL results in parasite clearance independent of Th2 cytokines [16]. Studies, not only in mice, but also in humans, suggested that cure was independent of the differential production of Th1 and Th2 cytokines, and both IFN-γ and IL-4 producing T cells have been isolated from asymptomatic and cured patients [17]. These immunosuppressive mechanisms could differ depending upon etiologic agent, T-cell subpopulation predominance at site of infection, stage of infection, and target organ. Such mechanisms could be even more complex because the course Leishmania infection may vary widely depending on the species and strain of parasite.

3. Immunomodulatory Effects of Adenosine and Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) Nucleotidases

In studying the complexity of immune system regulation, especially at the site of injury, several groups have recently begun to demonstrate a possible role for the nucleoside adenosine and adenosine nucleotidases in regulating Leishmania-specific immune responses. It was proposed that ecto-ATP diphosphohydrolases and ectonucleotidases, which are membrane-associated enzymes with their catalytic sites turned extracellular, would act to dephosphorylate adenosine nucleotides into free adenosine [18, 19]. Before discussing the role of ectonucleotidases in leishmaniasis, concepts and comments regarding the immunomodulatory roles of adenosine nucleotides and nucleosides must be stressed.

Extracellular nucleotides are involved in a variety of physiological functions by participating in extracellular signaling through the activation of cell surface metabotropic purinergic (G protein coupled) and ionotropic (ion channel coupled) receptors. The major classes of purinergic receptors include the type P2 receptors (P2X-P2Y) and ionotropic and metabotropic receptors [20–22]. The activation of these receptors by ATP leads to proinflammatory effects by initiating a response characterized by the secretion of IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF-α [23].

During acute inflammation, the ATP released by the leakage of cellular contents can be sequentially dephosphorylated by the action of ectonucleotidases, causing the concentration of extracellular adenosine to increase markedly [22, 24]. Adenosine exerts distinct effects on the immune system compared to ATP. The immunosuppressive actions of adenosine are triggered by activation of four receptor subtypes (A1, A2A, A2B, and A3) belonging to the family of purinergic receptors known as P1 or A. These receptor subtypes are members of a superfamily of receptors composed of seven transmembrane regions that are coupled to G proteins [22, 25] and expressed in neutrophils, macrophages, dendritic cells [26], and T cells [27]. These four adenosine receptor subtypes are expressed concomitantly in various immune cells [28, 29].

Purinergic signaling depends on several factors, including receptor expression, receptor sensitivity, and the levels of extracellular nucleotides and nucleosides. The concentration of extracellular adenosine can determine the activation of a given receptor due to the difference in A receptors affinity [28]. In physiological adenosine concentrations (0.2–0.5 μM), the A1 and A3 receptors are preferentially activated, while at higher adenosine concentrations (16,2–64,1 μM), such as those seen in inflammation, A2B receptors exert their effects [30].

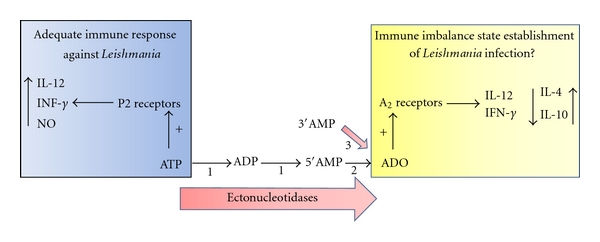

Activation of A2A and A2B receptors leads to increased levels of intracellular cAMP by activating adenylyl cyclase, which inhibits immune cell function [31]. This regulatory effect is caused mainly by inhibiting the production of IFN-γ, IL-12, and TNF-α coupled with an increased production of IL-10 [32] as summarized in Figure 1. Inhibition of monocyte maturation and the suppression of macrophage phagocytic function are also related to the activation of A2 receptors [33]. The signaling pathway that couples A2A and A2B adenosine receptors with G proteins is balanced by the signaling that results from the association of A1 and A3 receptors with Gi protein, which inhibits adenylyl cyclase. Adenylyl cyclase inhibition then leads to decreased levels of cAMP, which limits the premature inhibition of immune cells by A2 receptors [34].

Figure 1.

Partial reactions catalyzed by ecto-nucleoidases: (1) ecto-ATPase, ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase; (2) ecto-5′-nucleotidase; (3) ecto-3′-nucleotidase. The sequential hydrolysis of extracellular ATP by Leishmania ectonucleotidases triggers the host inflammatory and immune response following P2 receptor activation by extracellular ATP (blue square) and P1 (A2) receptors activation by extracellular adenosine nucleoside (yellow square). ADO: Adenosine.

4. Adenosine and the Establishment of Leishmania Infection: The Possible Role of Ectonucleotidases in Immune Impairment

Ectonucleotidases are glycoprotein enzymes present in the plasma membrane with their catalytic sites facing extracellularly [18, 19], which are capable of hydrolyzing extracellular nucleotides. Fundamentally important in maintaining the homeostasis of extracellular nucleotides, these enzymes are also regulatory (termination of signaling events triggered by ATP) and metabolic (generation of nutrients) in function [35]. The hydrolysis of extracellular nucleotides occurs in a sequential manner by the action of ecto-ATPase, ecto-ADPase, ecto-ATPDase, and ecto-5′-nucleotidase [36]. The classification of ectonucleotidases in different families takes into account kinetic aspects such as enzyme specificity and substrate affinity and molecular aspects of protein structure [37].

Since Gottlieb and Dwyer [38] provided information in 1981 about the biochemistry of surface membranes of Leishmania, a large number of authors have observed nucleotidases located on the outer surface of the plasma membrane of the parasite. For example, ecto-ATPases, ecto-5′-nucleotidase, and ecto-3′-nucleotidase have all been described in Leishmania sp. [18, 19, 39, 40].

In Leishmania parasites, it was proposed that an increase in ectonucleotidase activity would increase the production of adenosine, which would consequently aid in the establishment of infection through its immunosuppressive mechanisms. Infective L. amazonensis promastigotes exhibit higher ATPase activity compared to nonvirulent promastigotes [39]. Furthermore, amastigotes, which are responsible for maintenance of leishmaniasis in the vertebrate host, are capable of hydrolyzing ATP at higher rates than promastigotes [40]. L. amazonensis strains that possess higher ectonucleotidase activity are more effective in establishing infection in murine models [41]. Comparison of ectonucleotidase activities between L. amazonensis, Leishmania braziliensis (L. braziliensis), and L. major showed that the more virulent parasite causing nonhealing lesions in C57BL/6 mice (e.g., L. amazonensis) hydrolyzes higher amounts of ATP, ADP, and 5′AMP [42]. Furthermore, adenosine treatment at the time of L. braziliensis inoculation delays lesion resolution and induces increased parasite burdens. Consistent with this, inhibition of adenosine receptor A2B led to decreased lesion size and lower parasite burden [43]. In clinical practice, results that are consistent with the idea that ecto-ATPase activity is involved in virulence were also observed, whereby L. amazonensis strain isolated from a human case of VL possess higher ecto-ATPase activity than strains isolated from CL cases [44].

In addition to these ectonucleotidases, Leishmania parasites also express a bifunctional enzyme called 3′-nucleotidase/nuclease (3′NT/NU) in the plasma membrane with a high capacity to hydrolyze 3′ribonucleotides and nucleic acids [43, 45]. Although first identified in L. donovani [43, 45], it was later found in L. chagasi [46], L. major [47], L. mexicana [48], and L. amazonensis. Although the 3′-nucleotidase enzyme is found solely in some trypanosomatids, 3′-nucleotides are available through nucleic acid hydrolysis in several mammalian tissues [49], especially the spleen, an organ commonly targeted by Leishmania parasites. Recently, our group has characterized the 3′-nucleotidase activity of L. chagasi and demonstrated that such activity could be related to aspects of parasite virulence [46]. Interestingly, the viscerotropic L. chagasi and L. donovani had higher 3′-nucleotidase activity compared to the New World and Old World dermatotropic species (e.g., L. amazonensis, L. major, L. tropica, and L. braziliensis). L. chagasi metacyclics (infective promastigote stage) had higher 3′-nucleotidase activity compared to L. chagasi nonmetacyclics (noninfective promastigote stage) [46]. Similar results were also observed with L. amazonensis, where infective promastigotes possessed twofold higher 3′-nucleotidase activity compared to nonvirulent promastigotes [50].

In addition to the role of ectonucleotidase in the establishment of Leishmania infection by ectonucleotidases, some interesting data have further demonstrated that high expression/activity of such enzymes on immune cells contributes to immune imbalance. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) from mutant mice deficient in CD39 have impaired regulatory function manifesting as a 50% decrease in the ability of CD39-null Tregs to modulate effector T-cell function in vitro and in vivo. These results indicate that CD39 expressed by Treg is the major and rate-limiting ectonucleotidase responsible for the generation of adenosine and suggest that a putative CD39/CD73-adenosinergic axis may contribute to the immunoregulatory function of Treg [51, 52].

In L. infantum-infected BALB/c mice, Tregs are present. The high levels of Foxp3 gene expression and surface expression of Eb7 integrin (CD103) suggest a predisposition for Treg retention within sites of L. infantum infection, as is the case of the spleen and draining lymph nodes, consequently influencing local immune response [53]. It was attributing to CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ regulatory T cells an important role in immune suppression because in those cells, CD39 and CD73 are overexpressed. Inhibitors of ectonucleotidase activities and antagonists of the A2A receptor blocked Treg-mediated immunosuppression [54]. Consistent with this view, it was demonstrated that patients with VL possess high levels of adenosine, which was related to ectonucleotidase activities and disease progression [55].

This paper about the immune modulatory effects of adenosine and the production of such nucleoside by parasite and immune cells provide new perspectives for the understanding of the complex immune response in leishmaniasis. Further studies are needed, especially using visceral leishmaniasis models, to clearly delineate the role of ectonucleotidases in the establishment of infection and Leishmania-induced immunomodulation.

Acknowledgments

Part of the work mentioned in this paper was supported by grants from the Brazilian Agencies Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), and Instituto Nacional de Ciência e Tecnologia de Biologia Estrutural e Bioimagem (INCTBEB).

References

- 1.Desjeux P, Boelaert M, Sundar S, et al. Leishmaniasis. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2004;2(9):692–693. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nylén S, Sacks D. Interleukin-10 and the pathogenesis of human visceral leishmaniasis. Trends in Immunology. 2007;28(9):378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripathi P, Singh V, Naik S. Immune response to Leishmania: paradox rather than paradigm. FEMS Immunology and Medical Microbiology. 2007;51(2):229–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neuber H. Leishmaniasis. Journal of the German Society of Dermatology. 2008;6(9):754–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2008.06809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, Saravia NG. Advances in leishmaniasis. The Lancet. 2005;366(9496):1561–1577. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67629-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guerin PJ, Olliaro P, Sundar S, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: current status of control, diagnosis, and treatment, and a proposed research and development agenda. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2002;2(8):494–501. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(02)00347-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chappuis F, Sundar S, Hailu A, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis: what are the needs for diagnosis, treatment and control? Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2007;5(11):873–882. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herwaldt BL. Leishmaniasis. The Lancet. 1999;354(9185):1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Costa CHN, Werneck GL, Costa DL, et al. Is severe visceral leishmaniasis a systemic inflammatory response syndrome? A case control study. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2010;43(4):386–392. doi: 10.1590/s0037-86822010000400010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hailu A, van Baarle D, Knol GJ, Berhe N, Miedema F, Kager PA. T cell subset and cytokine profiles in human visceral leishmaniasis during active and asymptomatic or sub-clinical infection with Leishmania donovani . Clinical Immunology. 2005;117(2):182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2005.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sundar S, Reed SG, Sharma S, Mehrotra A, Murray HW. Circulating T helper 1 (Th1) cell- and Th2 cell-associated cytokines in Indian patients with visceral leishmaniasis. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1997;56(5):522–525. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.56.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurkjian KM, Mahmutovic AJ, Kellar KL, Haque R, Bern C, Secor WE. Multiplex analysis of circulating cytokines in the sera of patients with different clinical forms of visceral leishmaniasis. Cytometry Part A. 2006;69(5):353–358. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ettinger NA, Wilson ME. Macrophage and T-cell gene expression in a model of early infection with the protozoan Leishmania chagasi . PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2008;2(6):p. e252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bacellar O, Brodskyn C, Guerreiro J, et al. Interleukin-12 restores interferon-γ production and cytotoxic responses in visceral leishmaniasis. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1996;173(6):1515–1518. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.6.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoon P, Keylock KT, Hartman ME, Freund GG, Woods JA. Macrophage hypo-responsiveness to interferon-γ in aged mice is associated with impaired signaling through Jak-STAT. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development. 2004;125(2):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson ME, Young BM, Davidson BL, Mente KA, McGowan SE. The importance of TGF-β in murine visceral leishmaniasis. Journal of Immunology. 1998;161(11):6148–6155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peruhype-Magalhães V, Martins-Filho OA, Prata A, et al. Mixed inflammatory/regulatory cytokine profile marked by simultaneous raise of interferon-γ and interleukin-10 and low frequency of tumour necrosis factor-α(+) monocytes are hallmarks of active human visceral Leishmaniasis due to Leishmania chagasi infection. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2006;146(1):124–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meyer-Fernandes JR. Ecto-ATPases in protozoa parasites: looking for a function. Parasitology International. 2002;51(3):299–303. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5769(02)00017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer-Fernandes JR, Cosentino-Gomes D, Vieira DP, Lopes AH. Ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase activities in trypanosomatids: possible roles in infection, virulence and purine recycling. Open Parasitology Journal. 2010;4:116–119. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burnstock G. P2 purinoceptors: historical perspective and classification. CIBA Foundation Symposia. 1996;(198):1–28. doi: 10.1002/9780470514900.ch1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corriden R, Insel PA. Basal release of ATP: an autocrine-paracrine mechanism for cell regulation. Science Signaling. 2010;3(104):p. re1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3104re1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Junger WG. Immune cell regulation by autocrine purinergic signalling. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011;11(3):201–212. doi: 10.1038/nri2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langston HP, Ke Y, Gewirtz AT, Dombrowski KE, Kapp JA. Secretion of IL-2 and IFN-γ, but not IL-4, by antigen-specific T cells requires extracellular ATP. Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(6):2962–2970. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kumar V, Sharma A. Adenosine: an endogenous modulator of innate immune system with therapeutic potential. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;616(1–3):7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fredholm BB, Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, et al. VI. Nomenclature and classification of purinoceptors. Pharmacological Reviews. 1994;46(2):143–156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Addi AB, Lefort A, Hua X, et al. Modulation of murine dendritic cell function by adenine nucleotides and adenosine: involvement of the A2B receptor. European Journal of Immunology. 2008;38(6):1610–1620. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gessi S, Varani K, Merighi S, et al. Adenosine and lymphocyte regulation. Purinergic Signalling. 2007;3(1-2):109–116. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9042-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bours MJL, Swennen ELR, Di Virgilio F, Cronstein BN, Dagnelie PC. Adenosine 5′-triphosphate and adenosine as endogenous signaling molecules in immunity and inflammation. Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2006;112(2):358–404. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fortin A, Harbour D, Fernandes M, Borgeat P, Bourgoin S. Differential expression of adenosine receptors in human neutrophils: up-regulation by specific Th1 cytokines and lipopolysaccharide. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2006;79(3):574–585. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0505249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fredholm BB, Irenius E, Kull B, Schulte G. Comparison of the potency of adenosine as an agonist at human adenosine receptors expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2001;61(4):443–448. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00570-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raskovalova T, Huang X, Sitkovsky M, Zacharia LC, Jackson EK, Gorelik E. GS protein-coupled adenosine receptor signaling and lytic function of activated NK cells. Journal of Immunology. 2005;175(7):4383–4391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kreckler LM, Wan TC, Ge ZD, Auchampach JA. Adenosine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-α release from mouse peritoneal macrophages via A2A and A2B but not the A 3 adenosine receptor. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2006;317(1):172–180. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.096016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haskó G, Pacher P. A2A receptors in inflammation and injury: lessons learned from transgenic animals. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2008;83(3):447–455. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abbracchio MP, Ceruti S. P1 receptors and cytokine secretion. Purinergic Signalling. 2007;3(1-2):13–25. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9033-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yegutkin GG. Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2008;1783(5):673–694. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goding JW, Grobben B, Slegers H. Physiological and pathophysiological functions of the ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2003;1638(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(03)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zimmermann H. Extracellular metabolism of ATP and other nucleotides. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology. 2000;362(4-5):299–309. doi: 10.1007/s002100000309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gottlieb M, Dwyer DM. Protozoan parasite of humans: surface membrane with externally disposed acid phosphatase. Science. 1981;212(4497):939–941. doi: 10.1126/science.7233189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berrêdo-Pinho M, Peres-Sampaio CE, Chrispim PPM, et al. A Mg-dependent ecto-ATPase in Leishmania amazonensis and its possible role in adenosine acquisition and virulence. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2001;391(1):16–24. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2001.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinheiro CM, Martins-Duarte ES, Ferraro RB, et al. Leishmania amazonensis: biological and biochemical characterization of ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase activities. Experimental Parasitology. 2006;114(1):16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Souza MC, de Assis EA, Gomes RS, et al. The influence of ecto-nucleotidases on Leishmania amazonensis infection and immune response in C57B/6 mice. Acta Tropica. 2010;115(3):262–269. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marques-da-Silva EA, de Oliveira JC, Figueiredo AB, et al. Extracellular nucleotide metabolism in Leishmania: influence of adenosine in the establishment of infection. Microbes and Infection. 2008;10(8):850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dwyer DM, Gottlieb M. Surface membrane localization of 3’- and 5’-nucleotidase activities in Leishmania donovani promastigotes. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 1984;10(2):139–150. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(84)90002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Souza VL, Veras PST, Welby-Borges M, et al. Immune and inflammatory responses to Leishmania amazonensis isolated from different clinical forms of human leishmaniasis in CBA mice. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106(1):23–31. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gbenle GO, Dwyer DM. Purification and properties of 3’-nucleotidase of Leishmania donovani. Biochemical Journal. 1992;285(1):41–46. doi: 10.1042/bj2850041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vieira DP, Paletta-Silva R, Saraiva EM, Lopes AHCS, Meyer-Fernandes JR. Leishmania chagasi: an ecto-3′-nucleotidase activity modulated by inorganic phosphate and its possible involvement in parasite-macrophage interaction. Experimental Parasitology. 2011;127(3):702–707. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lakhal-Naouar I, Achour-Chenik YB, Boublik Y, et al. Identification and characterization of a new Leishmania major specific 3′nucleotidase/nuclease protein. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;375(1):54–58. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bates PA. Characterization of developmentally-regulated nucleases in promastigotes and amastigotes of Leishmania mexicana . FEMS Microbiology Letters. 1993;107(1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(93)90353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bushfield M, Shoshani I, Johnson RA. Tissue levels, source, and regulation of 3’-AMP: an intracellular inhibitor of adenylyl cyclases. Molecular Pharmacology. 1990;38(6):848–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paletta-Silva R, Vieira DP, Vieira-Bernardo R, et al. Leishmania amazonensis: characterization of an ecto-3′-nucleotidase activity and its possible role in virulence. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2011.07.014. Experimental Parasitology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Deaglio S, Dwyer KM, Gao W, et al. Adenosine generation catalyzed by CD39 and CD73 expressed on regulatory T cells mediates immune suppression. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2007;204(6):1257–1265. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dwyer KM, Deaglio S, Gao W, Friedman D, Strom TB, Robson SC. CD39 and control of cellular immune responses. Purinergic Signalling. 2007;3(1-2):171–180. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodrigues OR, Marques C, Soares-Clemente M, Ferronha MH, Santos-Gomes GM. Identification of regulatory T cells during experimental Leishmania infantum infection. Immunobiology. 2009;214(2):101–111. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mandapathil M, Hilldorfer B, Szczepanski MJ, et al. Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010;285(10):7176–7186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rai AK, Thakur CP, Velpandian T, Sharma SK, Ghosh B, Mitra DK. High concentration of adenosine in human visceral leishmaniasis: despite increased ADA and decreased CD73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2011.01315.x. Parasite Immunology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]