Abstract

Premature closure is a type of cognitive error in which the physician fails to consider reasonable alternatives after an initial diagnosis is made. It is a common cause of delayed diagnosis and misdiagnosis borne out of a faulty clinical decision-making process. The authors present a case of aortic dissection in which premature closure was avoided by the aggressive pursuit of the appropriate differential diagnosis, and discuss the importance of disciplined clinical decision-making in the setting of chest pain.

Background

Despite great advances in clinical science, modern medicine remains riddled by errors, many of which are serious enough to compromise patient care.1 These errors may originate on several levels, from the healthcare systems at large to individual clinicians.2 While good hospital management can reduce systemic errors, only vigilance on the part of physicians can prevent individual errors, especially cognitive errors rooted in the scope and application of the physician’s knowledge. This vigilance is especially important in regards to preventing premature closure,3 where verification occurs before examination of plausible alternatives.4 Indeed, literature cites many instances in which such an error has placed the patient’s life in jeopardy. We describe a case of chest pain where a diligent physician’s continued pursuit of the differential diagnoses averted premature closure during clinical decision-making in a busy inner-city hospital setting.

Case presentation

A 51-year old male with uncontrolled hypertension presented to the emergency department (ED) with two episodes of acute chest pain and an intermittent headache for the past 2 days. His first episode consisted of a stabbing non-radiating retrosternal chest pain that lasted for 2 min, which was not associated with palpitations, sweating or dyspnoea. He also reported dizziness and vomiting. The pain improved greatly after 2 min but left a sense of discomfort until his second episode 1 day later, which consisted of a dull aching diffuse chest pain in the sternal area. That pain lasted for 30 min, and was associated with dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and sweating severe enough to prompt a visit to the ED. The patient was a smoker who had been non-adherent to his antihypertensive medications for the past 2 weeks. Upon admission, his initial vitals were: blood pressure (BP) 246/140 mm Hg; pulse rate 59/min; respiratory rate 18/min. BP and pulse were approximately equal in all four limbs. Cardiac examination revealed 1/6 aortic ejection systolic and early diastolic murmur with loud S2. External jugular veins were not distended and there was no carotid bruit. Peripheral oedema was absent. Neurological examination found no deficits.

Investigations

EKG showed non-specific ST-T wave changes in the lateral chest leads. Chest x-ray revealed mild widening of the aortic silhouette in the mediastinum. Initial cardiac enzymes were negative. Laboratory data included haematocrit 46% and serum creatinine 1.7 mg/dl (glomerular filtration rate 45 ml/min based on Modification of Diet in Renal Disease formula). Electrolytes were within normal limits. Urinalysis revealed proteinuria 3+.

Differential diagnosis

Initial diagnoses of accelerated hypertension, acute coronary syndrome, and stage III chronic kidney disease were considered and a decision was made to admit the patient to the medical ward. The results of the serial EKG and cardiac enzyme set ruled out acute myocardial infarction (MI) as the cause. Cardiology evaluation suggested the diagnosis of accelerated hypertension and acute coronary syndrome. Bedside trans-thoracic echocardiogram revealed mild aortic regurgitation with normal aortic root, normal wall motion and left ventricular resting function.

Based on the evidence at that point in time, diagnosis of aortic dissection was considered to be unlikely by the ED, the medical attending on-call, and the cardiologist. However, in light of his elevated BP, abnormal aortic silhouette on chest x-ray, mild aortic regurgitation and no clear diagnosis for his chest pain, the hospitalist who had evaluated this patient prior to the cardiology team strongly felt that the differential diagnosis of aortic dissection should be explored further. Contrast enhanced CT of the chest was performed immediately, revealing Stanford Type A dissection of the arch of the aorta.

Treatment

The patient was initially administered aspirin, morphine, nitroglycerine, hydrochlorothiazide, atenolol, simvastatin and losartan, as well as intravenous labetalol for acute blood pressure control. After the contrast-enhanced CT scan, the patient was transferred to a cardiac surgery care referral facility where he had aortic arch repair.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperative course was uneventful and patient was discharged with follow-up in outpatient clinic.

Discussion

Chest pain is an alarming, but non-specific, presenting symptom that may suggest pathology in a number of organ systems of the body. Identification and differentiation of the causes of chest pain, which include MI, pulmonary embolism and aortic dissection, among others, is paramount since treatment is distinct for each cause. Unfortunately, atypical presentations obscure and delay prompt diagnoses in the clinical setting. Due to the immense amounts of conflicting information, especially in relation to the initial diagnosis, due diligence must be exercised to prevent committing diagnostic errors in these sorts of cases. Clinicians can do much to avoid such pitfalls by better understanding their own cognitive processes. Indeed, clinical decision-making in emergency circumstances may manifest as either heuristic thought, drawing on one’s own clinical knowledge and experience, or Bayesian inference, relying on statistic models of likelihood.5

The heuristic approach to diagnosis leads the physician to apply his knowledge and past experience to recognise a pattern from individual signs and symptoms. In the case of chest pain, the physician typically suspects MI first, based on the incidence and the lethality of the condition. However, there are many other lethal causes of chest pain with similar presentations that should not to be overlooked. Aortic dissection, for example, carries a mortality of 50% before the patient even reaches the hospital.6 Even upon initial evaluation, physicians may not notice the constellation of signs and symptoms typical of aortic dissection. Indeed, one-third of patients surviving to the emergency room (ER) present atypically, having dull chest pain more suggestive of myocardial ischaemia.7 In this particular case, the patient presented with two episodes of pain, as opposed to the one, and neither episode had the tearing type of pain that classically radiates to the back. In addition to a deceptive history, the physical examination failed to display the classical findings of aortic dissection. Unequal pulses due to occlusion of the large branches of the aorta by the growing pseudolumen were not seen in the patient.8 Likewise, neurological deficits related to hypoperfusion of areas of the brain supplied by the internal carotid artery were not noted. Though radiographs appear to be more objective than history or physical examination, plain chest radiography plays quite an equivocal role in the screening of aortic dissections. The classic widening of the mediastinum is a non-specific finding. In addition, chest x-ray films are subject to highly variable interpretations by different clinicians, operating under their own assumptions and heuristics. EKG, commonly performed on patients presenting with chest pain, may also prove to be red herrings. Non-specific EKG abnormalities have been reported in many cases. Finally, many patients are known to present with ST-T wave changes more suggestive of acute coronary syndrome, due to involvement of the coronary arteries in the condition. A doctor using heuristics as his mode of diagnostic reasoning would probably need to carry such experience and knowledge to be more successful in making a prompt diagnosis; it is altogether understandable that in an emergency setting, those who are less well-versed run the risk of committing premature closure by recognising an incorrect pattern of signs and symptoms.

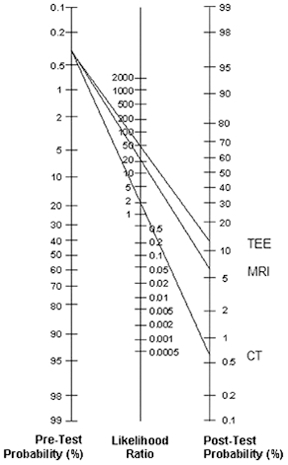

An alternative model of clinical decision-making is the Bayesian model of likelihood assessment. The physician first estimates the pretest odds of a particular condition, based on the patient’s clinical presentation. These pretest odds then serve to guide the selection of diagnostic tests. Since each test has its own sensitivity and specificity with regards to a diagnosis, a likelihood ratio, defined mathematically as sensitivity / 1 - specificity, can be ascertained, and then applied to obtain post-test odds of a particular condition. From these refined post-test probabilities, a diagnosis can then be ruled in and an appropriate treatment can be selected. Graphically, this thought process is often illustrated as a nomogram, with pretest probabilities being scaled to post-test probabilities via the likelihood ratio (figure 1).

Figure 1.

The nomogram is a diagrammatic representation of Bayesian analysis. A pretest probability of the disease is first estimated and then investigative procedures are undertaken to raise or lower the post-test probability, depending on the magnitude of the likelihood ratio defined as sensitivity/1-specificity. Since transoesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) has a high sensitivity and low specificity, it has a correspondingly high likelihood ratio, as compared to MRI and CT.

In this case, the pretest odds of aortic dissection is quite low, as aortic dissection is responsible for only 3% of cases of chest pain in the ED. Acute coronary syndrome has a far greater pretest probability, but the lack of specific EKG findings undermined such a diagnosis in our patient. Moreover, the findings of the chest x-ray, namely the presence of isolated mediastinal widening, indicated a pretest probability of 0.39.8 This value was concerning enough for the clinician to subsequently order a CT scan, whose likelihood ratio is 1.8. The results of the CT scan increased the post-test odds enough to have confidence in the diagnosis of aortic dissection. Alternatively, an MRI or transoesophageal echocardiogram may have been ordered, whose likelihood ratios are 19.9 and 49 respectively (figure 1).9 A case report of aortic dissection using a similar Bayesian approach has also been previously described by other authors.10 Though it is unreasonable to expect the clinician to work with such mathematical precision at the time of emergency, being mindful of such a thought process and possessing rough estimates of the likelihood ratios can guide the physician to the correct diagnosis.

Regardless, diagnostic error is not a phenomenon intrinsic to any particular approach. Rather, it arises from the improper application of those models, and, as such, can affect even the most seasoned physician if proper care is not taken. Premature closure, where verification precedes proper examination of plausible alternatives, is one grave manifestation of such an improper application; it arises most frequently in moments of rushed thought or lack of expertise. It may also occur alongside another related phenomenon, the anchor effect, whereby a particular illness script is placed on the patient without due regard to new and conflicting pieces of information. To avoid such errors, the physician ought to abide by certain guidelines (see learning points).

The ER is a clinical setting fraught with diagnostic errors that expose the vulnerability of even experienced physicians. Aortic dissection is one such difficult presentation, and as such, requires deliberative thought and analysis. Awareness that atypical presentations of aortic dissection are more common than the classical presentation provides a first step in such analysis. Indeed, the physician who harbors the prejudice that aortic dissection manifests exclusively as a tearing pain radiating to the back is far more likely to misdiagnose the condition as an MI. Furthermore, as data emerges, the physician ought to be vigilant in formulating and modifying a hypothesis that explains his findings, in lieu of forcing data to comply with a particular hypothesis. Finally, as patterns of data become increasingly complex, the physician should remain mindful of the patient instead of abstract data; in our case, an indispensible indicator of dissection lay in the discordance between relatively minor changes in radiographic, electrocardiographic and physical findings as well as complaints of disproportionately severe chest pain. In today’s emergency departments, aortic dissection remains a largely amorphous killer, but with greater clinical suspicion and deliberative analysis, the clinician can define it in time to save the patient. Yet for this to happen, the physician ought to not only know the patient but to also, as the ancient Greek saying goes, ‘know thyself’. In doing so, the atypical presentation of aortic dissection may be recognised promptly and this particular challenge of the ER may finally be overcome.

Learning points.

-

▶

Worst-case scenarios ought to be ruled out first. Less severe diagnoses can be assessed in due time, but life-threatening situations require prompt identification.

-

▶

A complete history, in conjunction with chest x-rays, are the greatest tools in identifying an acute aortic dissection.

-

▶

Algorithms can supplement diagnostic skills when sufficient expertise is lacking.

-

▶

Findings inconsistent with the initial diagnosis should not be overlooked, as they may be important indicators of an alternate diagnosis.

-

▶

Reduce diagnostic error by scrutinising one’s own cognitive processes.

Footnotes

Competing interests None.

Patient consent Obtained.

References

- 1.Richardson WC, Berwick DM, Bisgard JC, et al. The Institute of Medicine report on medical errors. N Engl J Med 2000;343:663–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordon R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1493–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McSherry D. Avoiding premature closure in sequential diagnosis. Artif Intell Med 1997;10:269–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borrell-Carrió F, Ronald M. Epstein preventing errors in clinical practice: a call for self-awareness. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:310–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2217–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isselbacher EM, Eagle KA, Zipes DP, et al. Diseases of the aorta. In: Braunwald E, ed. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Fifth edition Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1997:1546–81 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagan PG, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, et al. The International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection (IRAD): new insights into an old disease. JAMA 2000;283:897–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Kodolitsch Y, Schwartz AG, Nienaber CA. Clinical prediction of acute aortic dissection. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:2977–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim MH, Eagle KA, Isselbacher EM. Bayesian persuasion. Circulation 1999;100:e68–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bedient JT, Isakow W, Witt CA, eds. Washington Manual of Critical Care. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins; 2007:311–28 [Google Scholar]