Abstract

The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has proven to be a rich source of information about the mechanisms and regulation of homologous recombination during meiosis. A common technique for studying this process involves microdissecting the four products (ascospores) of a single meiosis and analyzing the configuration of genetic markers in the spores that are viable. Although this type of analysis is powerful, it can be laborious and time-consuming to characterize the large numbers of meioses needed to generate statistically robust data sets. Moreover, the reliance on viable (euploid) spores has the potential to introduce selection bias, especially when analyzing mutants with elevated frequencies of meiotic chromosome missegregation. To overcome these limitations, we developed a versatile, portable set of reporter constructs that drive fluorescent protein expression specifically in only those spores that inherit the reporter. These spore-autonomous fluorescence constructs allow direct visualization of inheritance patterns in intact tetrads, eliminating the need for microdissection and permitting meiotic segregation patterns to be ascertained even in aneuploid spores. As proof of principle, we demonstrate how different arrangements of reporters can be used to quantify crossover frequency, crossover interference, gene conversion, crossover/noncrossover ratios, and chromosome missegregation.

MEIOSIS is a specialized form of cell division in which a single round of DNA replication is followed by two successive rounds of chromosome segregation. In contrast to mitosis, where daughter cells are identical to the mother cell, the progeny of a meiotic cell division have half the genome equivalent of the progenitor cell. This inheritance pattern is achieved by modifying the mitotic chromosome-segregation machinery in three ways (Marston and Amon 2004). First, homologs pair and become physically connected by chiasmata during prophase I, ensuring proper attachment to the meiosis I (MI) spindle. Second, cohesion established between sister chromatids during premeiotic S phase is lost in a step-wise manner: chromatid-arm cohesion is lost during MI, allowing for homologs to segregate to opposite poles, whereas centromeric cohesion is maintained until late meiosis II (MII) to prevent premature separation of sister chromatids (PSSC) and to allow proper attachment to the MII spindle. Third, sister centromeres are oriented toward the same spindle pole in MI, but toward different spindle poles during MII. Failure to follow this series of events can result in abnormal chromosome segregation and formation of aneuploid gametes.

An important challenge is to define the spatial and temporal regulation of these processes, including the control of interhomolog crossing over, which is essential for the establishment of chiasmata. Crossing over is initiated by developmentally programmed DNA double-strand break (DSB) formation catalyzed by the topoisomerase-like protein, Spo11 (Keeney et al. 1997). In the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ∼160 DSBs are generated per meiosis (Pan et al. 2011). On average, ∼90 DSBs are repaired as crossovers, and the remainder are repaired as either interhomolog noncrossovers or intersister recombinants (Chen et al. 2008; Mancera et al. 2008). However, this repair process is not random, as each pair of homologous chromosomes requires at least one crossover (often referred to as the obligate crossover) and, when two or more crossovers occur on the same chromosome pair, they tend to be farther apart than expected by chance (referred to as “crossover interference”) (Jones 1984; Page and Hawley 2003).

In budding yeast, all four products of a single meiosis can be recovered using a technique called tetrad analysis, which is often used to determine the frequency of crossing over between genetic markers as it provides clear information on the number of reciprocal exchanges in a given interval (Hawley 2007). Tetrad analysis can also identify non-Mendelian segregation events such as gene conversions. However, one drawback to tetrad analysis as currently conducted is the requirement that spores be viable (i.e., able to germinate and form colonies) to score segregation of genetic markers. Moreover, many analyses also require that all four spores of a tetrad are viable.

Elucidating the mechanism and regulation of crossing over and chromosome segregation relies on the study of mutants that alter recombination patterns. For example, mutations in the ZMM family of genes (ZIP1–4, SPO16, MSH4/5, MER3) reduce crossing over, elevate homolog nondisjunction, and decrease crossover interference (Börner et al. 2004; Chen et al. 2008). However, analysis of these mutants is often complicated by low spore viability and temperature-modulated reduction in sporulation efficiency (Börner et al. 2004). Furthermore, crossover interference is measured as a probabilistic phenomenon, i.e., one in which observed frequencies of particular recombinant configurations are compared to frequencies predicted under the null hypothesis of a random distribution of crossovers (Berchowitz and Copenhaver 2008). As a result, many individual meioses must be examined to make statistically significant claims regarding the effects of a particular mutation, making data collection a significant limiting factor in studies of crossover control.

To circumvent the dependence on viable spores and to make data collection less time consuming, we sought to develop a series of fluorescent markers that can be scored in spores, independent of germination and colony formation. Developing such markers requires that the promoter controlling fluorescent protein expression remains “off” until after pro-spore membrane formation and cytokinesis. During MII, prospore membrane formation is initiated at the outer plaque (cytoplasmic surface) of the spindle pole bodies (SPB) and expands from these sites of nucleation to engulf the nuclear lobe to which it is anchored via the SPB (Moens 1971; Neiman 2005). Following nuclear division, closure of the prospore membrane occurs via cytokinesis to capture each of the haploid nuclei (Neiman 2005). Spore-wall synthesis is then initiated in the lumen between the two prospore membrane-derived membranes followed by the collapse of the anucleate mother cell to form the ascus (Lynn and Magee 1970; Neiman 2005).

Here, we show that spore-autonomous fluorescent markers allow crossing over, crossover interference, gene conversion, and chromosome missegregation to be detected and quantified directly in budding-yeast tetrads. Fluorescent marker segregation can be scored even in inviable aneuploid spores, facilitating analysis of mutants with elevated chromosome missegregation. By eliminating tetrad microdissection, large data sets can be generated rapidly for mutant strains under various culture conditions.

Materials and Methods

Yeast strains and plasmids

Strains were of the SK1 background (Supporting Information, Table S1). The m-Cerulean (CFP), tdTomato (RFP), and GFP* markers (Table 1) were engineered using PCR. For m-Cerulean, 596 bp of YKL050c promoter DNA (upstream of the start codon) was amplified from S. bayanus genomic DNA and fused to the 5′ end of the m-Cerulean open reading frame (plasmid from Jeffrey Smith, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center). The PGK1 terminator was then amplified from S. bayanus (416 bp downstream of the PGK1 stop codon), fused to the 3′ end of m-Cerulean, and cloned into pCR2.1. EcoRI sites (added to the 5′ YKL050c primer and 3′ PGK1 terminator primer) were used to excise the fragment from pCR2.1 and subclone it into pRS404 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). Targeting this plasmid to THR1 was achieved by PCR-amplifying Saccharomyces Genome Database (SGD) coordinates 160333–160951 on chromosome VIII (5′ and 3′ primers contain SacII restriction sites), digesting the PCR product with SacII, and cloning the fragment into pRS404-m-Cerulean. To linearize the plasmid for transformation, an AflII restriction site was introduced into the THR1-targeting region by Quickchange Site-directed Mutagenesis (Stratagene) with the primers 5′-CATTAACAATACAGATAATGAATCTTAAGTTGTTTTCAGTCTC and 5′-GAGACTGAAAACAACTTAAGATTCATTATCTGTATTGTTAATG.

Table 1 . Plasmids.

| Plasmid number | Description |

|---|---|

| pSK691 | PYKL050c-RFP in pRS305 (LEU2) |

| pSK692 | PYKL050c-CFP in pRS404 (TRP1) |

| pSK693 | PYKL050c-RFP in pRS305 (LEU2), targets integration to CEN8 |

| pSK694 | PYKL050c-CFP in pRS404 (TRP1), targets to CEN8 |

| pSK695 | PYKL050c-CFP in pRS404, targets to THR1 |

| pSK724 | PGPD1-gfp*-atg (BamHI–SalI fragment) in pMJ349 (URA3) targets to ARG4 |

| pSK725 | PGPD1-gfp*-R215X (BamHI–SalI fragment) in pMJ349 targets to ARG4 |

| pSK726 | PYKL050c-GFP* in pRS306 (URA3) |

| pSK729 | PYKL050c-GFP* in pRS306 (URA3) targets to ARG4 |

For tdTomato, 607 bp of YKL050c promoter DNA and 412 bp of PGK1 terminator DNA from S. kudriavzevii was fused to the tdTomato open reading frame (plasmid from Mark Lundquist, Weill Cornell) and cloned into pCR2.1. BamHI was used to excise the fragment from pCR2.1 and subclone it into pRS305 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989). A silent mutation was introduced into the LEU2 coding sequence on the plasmid using site-directed mutagenesis to destroy the AflII restriction site. Targeting this construct and the m-Cerulean construct to CEN8 was achieved by PCR-amplifying SGD coordinates 105705–106240 on chromosome VIII (5′ and 3′ primers contain SacII restriction sites), digesting the PCR product with SacII, and cloning the fragment into pRS305-tdTomato or pRS404-m-Cerulean. To linearize the plasmids for transformation, an AflII restriction site was introduced into the CEN8-targeting region by site-directed mutagenesis with the primers 5′-CTGAAACCGTCAACTTAAGAAGGGATGTGATATATTCAAAATGG and 5′-CCATTTTGAATATATCACATCCCTTCTTAAGTTGACGGTTTCAG.

For GFP*, 603 bp of YKL050c promoter DNA and 416 bp of PGK1 terminator DNA from S. mikatae was fused to the Green Lantern open reading frame cloned into pCR2.1. EcoRI was used to excise the fragment from pCR2.1 and subclone it into pRS306. The Green Lantern emission spectrum significantly overlapped with the cyan epifluorescence channel on our microscope, causing ambiguity in scoring Gfp+ and Cfp+ spores (data not shown). To circumvent this issue, the green emission spectrum was shifted to yellow by introducing five mutations in Green Lantern (T65G, V68L, Q69M, S72A, and T203Y) (Griesbeck et al. 2001) using site-directed mutagenesis. We refer to this modified protein as “GFP*” hereafter. Targeting to ARG4 was achieved by PCR-amplifying SGD coordinates 140928–142149 on chromosome VIII (5′ and 3′ primers contain SacII restriction sites), digesting the PCR product with SacII, and cloning the fragment into pRS306-Green*. AflII was used to linearize the plasmid for transformation.

For the gfp* heteroalleles, the TaqI fragment (653 bp) of the GPD1 promoter (the 5′ primer has a BamHI site) and a 908-bp fragment (containing 765 bp of the PGK1 terminator) starting at the PstI site and extending in the 3′ direction (the 3′ primer has a SalI site) were amplified from plasmid pG1 (Schneider and Guarente 1991) and fused to the Green Lantern open reading frame. The resulting fragment was cloned into pCR2.1. We used site-directed mutagenesis to destroy a BamHI restriction site in the Green Lantern open reading frame and SalI and EcoRI sites in the PGK terminator sequence. A BamHI–SalI double digest excised the fragment from pCR2.1 for subcloning into pMJ349, replacing the arg4-bgl allele (Borde et al. 1999). The green emission spectrum was shifted to yellow as described above. Site-directed mutagenesis was used to change the start codon (ATG) in one GFP* allele to ACG (gfp*-atg) and introduce a premature stop (TGA) at codon 215 in the other (gfp*-R215X). EcoRI sites were reintroduced into the resulting plasmid by Quickchange Multi Site-directed Mutagenesis (Stratagene) with the primers 5′-GCCCTTTCGTCTTCAAGAATTCATCTGTAAACTACAACCACC and 5′-GACAAAATGCCATGAGAATTCCCTCATGTTTGACAGCTTATCATCG. Targeting this construct to ARG4 was achieved by PCR-amplifying SGD coordinates 140917–142168 on chromosome VIII (5′ and 3′ primers contain EcoRI restriction sites), digesting the PCR product with EcoRI and cloning the fragment into pMJ349-Green*. AflII was used to linearize the plasmids for transformation.

The gfp* heteroalleles were flanked by previously described NdeI restriction site polymorphisms (Martini et al. 2006), introduced by two-step gene replacement, and confirmed by Southern blotting of genomic DNA. The MSH5 deletion was made by replacing the coding sequence with the kanMX4 cassette (Wach et al. 1994).

DSB measurements and random spore analysis

Cultures of sae2Δ strains were grown in liquid YPA (1% yeast extract, 2% Bacto peptone, 1% potassium acetate) for 13.5 hr at 30°, harvested, resuspended in 2% potassium acetate, and incubated at 30°. Samples were collected at 0 and 8 hr, and DNA was prepared for conventional agarose electrophoresis (Murakami et al. 2009). DNA was digested with BglII and probed with part of the YHR018c open reading frame (SGD coordinates 140353–140717). Blots were quantified by PhosphorImager. DSBs are expressed as the percentage of total radioactivity in the lane after background subtraction, not including material in wells. Random spore analysis was performed as previously described (Martini et al. 2006). Map distances (cM ± SE) were calculated using the Stahl Lab Online Tools (http://www.molbio.uoregon.edu/~fstahl/).

Meiotic time courses and analysis of events by microscopy and FACS

For experiments performed at 23° and 30°, the sporulation protocol was as described above, with sporulation medium pre-equilibrated to the appropriate temperature. For experiments performed at 33°, cells were sporulated at 30° for 2 hr and then shifted to 33°. All cultures were sporulated for 48–60 hr. Tetrads were briefly sonicated and then analyzed using a Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope. Diploid cells heterozygous for each fluorescent marker were sporulated, harvested, treated with 500 μg zymolyase (20T), diluted in 0.1% Tween-20, sonicated, and then analyzed using a Cytomation MoFlo Cell Sorter. To enrich for Gfp*+ tetrads in the crossover/noncrossover analysis, cells were harvested and resuspended in an equal volume of 0.1% Tween-20, sonicated briefly, and then sorted.

Incidental crossover analysis using NdeI restriction site polymorphisms

Individual Gfp*+ spores were isolated by FACS and plated onto rich medium. The resulting colonies were replica-plated onto media lacking tryptophan or leucine to identify cells containing the CFP::TRP1 marker or the RFP::LEU2 marker, respectively. DNA was extracted from spores with both parental and nonparental configurations of these markers and analyzed to determine the configuration of the flanking NdeI polymorphisms by PCR amplification followed by digestion with NdeI (Martini et al. 2006).

Results

Versatile, portable constructs that drive spore-autonomous fluorescent protein expression

An elegant fluorescent method was developed for visual analysis of recombination events in tetrads of Arabidopsis thaliana pollen grains, facilitating measurement of genetic distances and crossover interference (Francis et al. 2007). We wanted to develop a similar assay for S. cerevisiae, in which fluorescent protein expression could be detected only in spores that inherit a copy of the reporter gene, termed “spore-autonomous” expression.

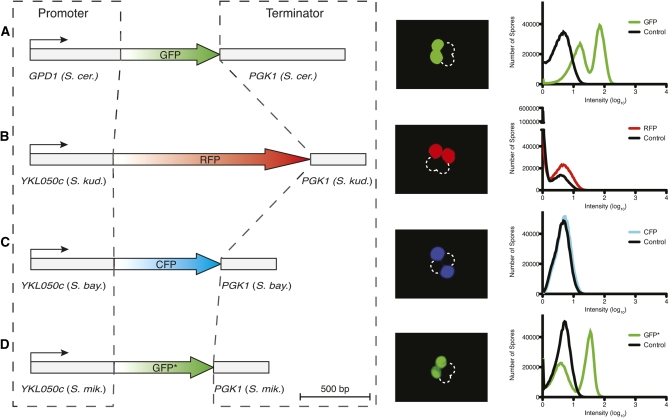

We examined PGPD1 and PYKL050c, two promoters previously reported to give this expression pattern (Gordon et al. 2006; Mell et al. 2008). When individual spores from a PGPD1-GFP hemizygote were analyzed by FACS, equally abundant GFP-high and GFP-low populations were observed, with an approximately fourfold average difference in GFP intensity between them (Figure 1A). Notably, spores that did not inherit PGPD1-GFP (the GFP-low population) also had GFP levels above background (Figure 1A), likely due to vegetative expression.

Figure 1 .

Promoter and terminator combinations to drive spore-autonomous expression of fluorescent proteins. Constructs are diagrammed to scale on the left of A–D, with promoters and terminators cloned from the indicated species. Epifluorescent images of whole tetrads and FACS profiles of individual spores are shown, derived from diploid cells hemizygous for the corresponding construct. Spores from a diploid strain lacking fluorescent markers were used as a control.

PYKL050c exhibited less background fluorescence, enabling ready detection by microscopy of spore-autonomous expression in strains hemizygous for PYKL050c-RFP or PYKL050c-CFP (Figures 1, B and C). However, these signals could not be detected using any of several cytometers evaluated (Figure 1, B and C, and data not shown). In contrast, spore-autonomous expression was readily detected by both microscopy and FACS for a modified version of GFP (PYKL050c-GFP*), which was engineered to reduce emission in the cyan epifluorescence channel (Figure 1D; see Materials and Methods). PYKL050c-GFP* gave approximate ninefold difference in fluorescence intensity between the negative and positive spore populations (Figure 1D).

To minimize the possibility of recombination between reporters, we isolated YKL050c promoter and PGK1 terminator sequences from different Saccharomyces species: S. mikatae, S. kudriavzevii, and S. bayanus (Figure 1). The percentage identity between the sequences is <65.8% and <82.9% for the promoters and terminators, respectively (Table S2). The fluorescent protein-coding sequences also have low sequence identity (<81.0%, excluding the Green Lantern and GFP* comparison) (Table S2). Each reporter cassette has a different selectable marker (RFP::LEU2, CFP::TRP1, GFP*::URA3) on integration vectors that provide portability by allowing targeting throughout the genome. Below, we show proof-of-principle experiments for a series of configurations to score different meiotic chromosome behaviors.

Chromosome segregation

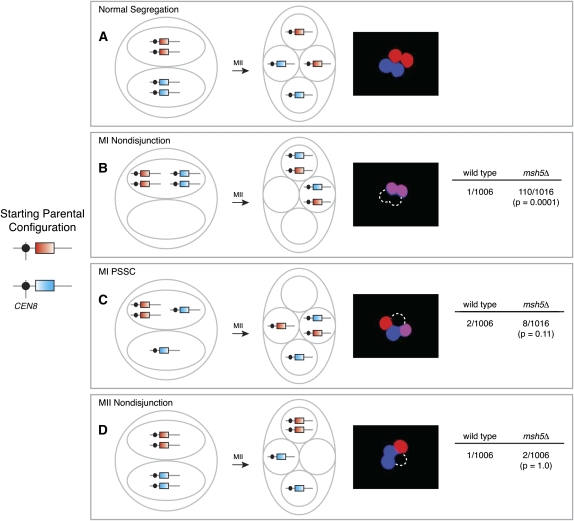

By integrating PYKL050c-RFP and PYKL050c-CFP at allelic positions near the centromere of chromosome VIII, we can score MI nondisjunction, MI PSSC, and MII nondisjunction. Proper chromosome segregation yields tetrads with two Rfp+ spores and two Cfp+ spores (Figure 2A). However, if homologs fail to disjoin at MI, two spores will be both Rfp+ and Cfp+ and two will be nonfluorescent (Figure 2B), whereas PSSC during MI yields tetrads containing one Rfp+ and Cfp+ spore, one Rfp+ spore, one Cfp+ spore, and one nonfluorescent spore (Figure 2C). Both types of missegregation give unambiguous fluorescent patterns because all four marked chromatids (two red and two cyan) can be directly observed.

Figure 2 .

Chromosome missegregation assay. PYKL050c-RFP and PYKL050c-CFP were integrated in allelic positions near CEN8. Cartoons show configuration of the markers after MI and MII for normal segregation and different types of missegregation, and micrographs show examples of each segregation pattern. Data on the right of B–D show the frequency of each type of missegregation in diploid wild-type and msh5Δ strains, pooled from two independent cultures of each strain (≥501 tetrads/culture). Statistical significance was evaluated by Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed P-value). The complementary arrangement for MII nondisjunction was also observed (one Cfp+ spore, two Rfp+ spores, and one nonfluorescent spore; data not shown).

In the event of MII nondisjunction, two spores inherit only the cyan (or red) marker, one spore inherits both of the red (or cyan) markers, and one spore is nonfluorescent (Figure 2D). This pattern is potentially ambiguous because a nonfluorescent spore could also arise through failure to activate the YKL050c promoter. For example, if spores are damaged or if there are spore-autonomous trans-acting loci essential for expression from PYKL050c and the chromosome(s) carrying such loci does not segregate with the chromosome carrying the fluorescent markers, then a spore will be nonfluorescent. Such false negatives would potentially be more frequent in mutants with elevated missegregation rates. To determine the proportion of tetrads with damaged spores, we constructed a diploid strain homozygous for PYKL050c-RFP integrated near the centromere of chromosome VIII and for PGPD1-GFP integrated at LEU2 on chromosome III. Events where both chromosome III and chromosome VIII do not disjoin at MII and segregate to the same spindle pole should be exceedingly rare; therefore, any spore that is completely nonfluorescent is likely damaged or dead. Of 2147 tetrads analyzed, we did not observe a single nonfluorescent spore (<0.05%). The frequencies of chromosome III (24/2147) and chromosome VIII (9/2147) MII nondisjunction observed in the same experiment were significantly greater than the frequency of nonfluorescent spores (P = 0.0001 and P = 0.004, respectively).

As validation of this assay, we analyzed wild-type and msh5Δ cells. Msh5 is a meiosis-specific MutS homolog that does not exhibit mismatch repair activity (Hollingsworth et al. 1995) and that stabilizes intermediates in the crossover repair pathway (Börner et al. 2004; Snowden et al. 2004). Deleting MSH5 increases MI nondisjunction, but rates of MI PSSC and MII nondisjunction are relatively unaffected (Sym and Roeder 1994; Hollingsworth et al. 1995). As expected, all forms of chromosome missegregation were rare in wild type, whereas the msh5Δ mutant showed 109-fold elevation of MI nondisjunction without a change in PSSC or MII nondisjunction (Figure 2, B–D). The MI nondisjunction frequency (10.8%) was lower than reported for chromosome III (15%) (Hollingsworth et al. 1995), presumably because chromosome III, being shorter, is more likely to fail to generate a crossover (Mancera et al. 2008).

Measuring crossover frequency and interference

In budding yeast, the most common way to quantify crossing over involves dissecting tetrads and scoring spore-derived colonies for segregation of heterozygous markers by replica-plating to selective media or by physical analysis of DNA sequence polymorphisms. This approach often requires that all four spores of a tetrad be viable, especially for analysis of crossover interference. It can take more than a week to perform dissections and score phenotypes for 1000 meioses for a wild-type strain sporulated under a single condition, and even longer for mutants that yield fewer four-spore viable tetrads.

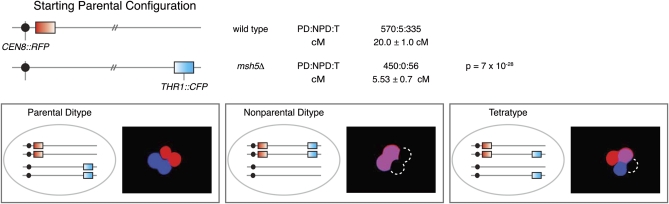

Our fluorescent constructs eliminate tetrad dissection and largely alleviate spore viability requirements, thus significantly reducing the time to perform a genetic analysis. As proof of principle, we integrated PYKL050c-CFP at the THR1 locus on chromosome VIII and mated this strain with one that has PYKL050c-RFP integrated near CEN8 (Figure 3). In wild type, we observed a genetic distance of 20.0 cM (Figure 3), comparable to that previously reported for the same chromosomal region but scored with different genetic markers (20.1 cM) (Martini et al. 2006). In a msh5Δ mutant, the crossover frequency was reduced 3.6-fold (Figure 3), within the expected range of 2- to 5-fold (Malkova et al. 2004; Nishant et al. 2010).

Figure 3 .

Two-factor cross to measure genetic distance. PYKL050c-RFP and PYKL050c-CFP were integrated at CEN8 and THR1, respectively, and segregation of these markers was assessed in wild-type and msh5Δ strains (one culture of each). Cartoons show possible configurations of markers, and micrographs show examples of corresponding tetrads. The frequency of parental ditype (PD), nonparental ditype (NPD), and tetratype (T) tetrads is shown, along with calculated map distances (±SE). For the msh5Δ strain, NPDs were scored as MI nondisjunction events (see Chromosome segregation) and thus not included in the map distance calculations. Statistical significance was evaluated by G test for the distribution of tetrad classes for each strain.

By also integrating PYKL050c-GFP* at ARG4 (Figure 4, A–C), we set up a three-factor cross that allows crossover interference to be examined using the method of Malkova et al. (2004). Briefly, tetrads are divided into two classes: those that have a detectable crossover in a reference interval [tetratypes (T) and nonparental ditypes (NPD)] and those that do not [parental ditypes (PD)]. For each class, we assessed the crossover frequency in the adjacent test interval. If crossing over in the reference interval is associated with a significantly lower crossover frequency in the test interval, then positive crossover interference is present between the two intervals. For example, a wild-type strain sporulated at 30° exhibited a crossover frequency of 5.90 cM in the test interval ARG4-THR1 when there was no crossover in the reference interval CEN8-ARG4, but only 1.37 cM when the reference interval did display a crossover (Table S3). Taking the ratio of the two values (1.37/5.90 = 0.23) gives an estimate of the strength of interference—the lower the value, the stronger the interference.

Figure 4 .

Using a three-factor cross to measure crossover interference. (A) The configuration of PYKL050c-RFP, PYKL050c-GFP*, and PYKL050c-CFP. (B) Schematic representations and micrographs illustrating the configuration of markers when there is a recombination event in either the CEN8-ARG4 interval or the ARG4-THR1 interval. (C) A tetrad with a recombination event in both the CEN8-ARG4 and ARG4-THR1 intervals. This is a three-strand double crossover (DCO) between CEN8 and THR1. Two-strand and four-strand DCOs (one crossover in each interval) can also be identified but are not shown here. (D) An MI nondisjunction tetrad. This segregation pattern is ambiguous because it can also arise from a four-strand DCO in the ARG4-THR1 interval (see Measuring crossover frequency and interference). A four-strand DCO in the CEN8-ARG4 interval is unambiguous (not shown). (E) Interference was assessed at 23°, 30°, and 33°. Numbers above the arcs are the average interference ratios for the interval pair. The smaller the ratio, the greater the apparent strength of interference. Solid arcs indicate significant interference; dashed arcs indicate that there was no statistically significant evidence for interference. The statistical significance was evaluated by G test for the distribution of tetrad classes in the test interval with vs. without a crossover in the adjacent interval. (F) Genetic distances for wild-type and msh5Δ strains sporulated at the indicated temperatures. (G) MI nondisjunction. Error bars are the 95% confidence interval of the proportion. An asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference (Fisher’s exact test (two tailed P-value); P < 0.05).

Interference was observed between the CEN8-ARG4 and ARG4-THR1 intervals at 30° in wild type but not in a msh5Δ mutant (Figure 4E and Table S3), similar to previous results for this region (Martini et al. 2006 and Neil Hunter, personal communication). A major advantage of the fluorescence-based assay is the ability to look easily at multiple conditions once strains are constructed, for example, altering temperature and/or sporulation medium, adding chemicals that affect key cellular processes, etc. To illustrate the ease with which alternative analyses can be conducted, we also measured crossing over in wild-type and msh5Δ strains at 23° and 33°. In both strains, varying temperatures across this range did not significantly alter either crossover frequencies (Figure 4F and Table S3) or presence or absence of interference (Figure 4E and Table S3).

In this three-factor cross, MI nondisjunction and a four-chromatid double crossover (i.e., NPD) in the ARG4-THR1 interval will give the same fluorescence pattern, with two spores each inheriting all three markers and two spores inheriting none (Figure 4D). However, <0.07% of tetrads displayed an NPD in the CEN8-ARG4 interval, which can be scored unambiguously (3 of 4397 total tetrads for wild type and msh5Δ mutant combined; Table S3). Double crossovers are expected to be even rarer in the smaller ARG4-THR1 interval and thus are substantially less frequent than MI nondisjunction, especially in the msh5Δ mutant (Figure 2). We therefore counted all tetrads with the fluorescence pattern shown in Figure 4D as MI nondisjunction events.

At all temperatures tested, the wild-type strain exhibited a low frequency of MI nondisjunction (≤0.3%) (Figure 4G and Table S3). In the msh5Δ mutant, MI nondisjunction at 30° (12.7%) (Figure 4G and Table S3) was similar to that observed with the chromosome missegregation assay (Figure 2B), and comparable frequencies were observed at 23° (Figure 4G and Table S3). In contrast, at 33°, a significantly lower frequency was observed (9.2%) (Figure 4G and Table S3), in agreement with published data showing temperature-modulated chromosome III segregation patterns in msh5 mutants without corresponding changes in crossover frequency (Chan et al. 2009).

It is noteworthy that, once the sporulated cultures were in hand, it took <2 hr to score segregation patterns in 500–1000 tetrads for each of two strains at three temperatures; conventional tetrad dissection and replica-plating likely would have taken many weeks. We conclude that spore-autonomous fluorescent constructs allow much quicker and easier analysis of crossover frequency and interference compared to classical methods. Moreover, MI nondisjunction can be scored concurrently, further reducing the time for comprehensive analysis of a given mutant.

Quantifying crossovers and noncrossovers at a single locus

Heteroallele recombination reporter:

Figure S1 diagrams one way to compare relative frequencies of crossovers and noncrossovers at a single locus (Martini et al. 2006). Strains heterozygous for different arg4 mutant alleles are sporulated and then Arg+ recombinants are selected from random spore populations, and the configuration of flanking markers is determined by replica-plating onto selective media. This is a sensitive assay because the Arg+ selection step allows large numbers of recombinant chromosomes to be scored, but a drawback is that the random spore analysis squanders a strength of yeast, namely, the ability to recover all four products of a single meiosis. Moreover, viable spores are required, which can create a sampling bias that affects observed crossover/noncrossover ratios because crossovers (but not noncrossovers) promote viability by ensuring proper chromosome segregation.

To address these limitations, we designed a fluorescence-based assay to measure crossovers and noncrossovers in tetrads in a manner less dependent on spore viability. We used GFP* as the central recombination reporter, introducing a single point mutation that destroys the start codon in one allele and a single point mutation that creates a premature stop at codon 215 in the other allele (Figure 5A). Spores that inherit either allele do not fluoresce, but functional GFP* can be generated by recombination. Since premeiotic (non-spore-autonomous) expression of mutant gfp* does not yield functional fluorescent protein, we used the S. cerevisiae GPD1 promoter. The PGPD1-gfp* alleles were integrated at ARG4 within the context of plasmid sequences that provide DSB hotspots (Wu and Lichten 1995; Borde et al. 1999). DSBs form predominantly at two locations within the integrated plasmid-associated DNA: upstream of the GPD1 promoter and near the 3′ end of gfp* extending into the PGK1 terminator (Figure 5B). Although DSBs form with a higher frequency near the GPD1 promoter (1.38 ± 0.21%), the majority of these DSBs occur ∼900–1100 bp from the gfp*-atg mutation (Figure 5B). DSB formation in the PGK1 terminator occurs at a lower frequency (0.90 ± 0.15%); however, a portion of these DSBs are generated near the 3′ end of gfp*, only ∼50–200 bp from the gfp*-R215X mutation (Figure 5B). Different spore-autonomous markers were integrated in flanking positions to enable scoring of crossovers and noncrossovers (Figure 5A).

Figure 5 .

Fluorescent crossover/noncrossover assay. (A) The configuration of PGPD1-gfp* heteroalleles, NdeI restriction site polymorphisms, and flanking PYKL050c-RFP and PYKL050c-CFP markers is diagrammed. The relative frequency and position of DSBs are indicated with arrows. (B) DSBs at the ARG4::gfp* insertion site. A Southern blot of BglII-digested genomic DNA from a meiotic culture of a strain homozygous for sae2Δ and containing the fluorescence recombination reporter diagrammed in A. (C) FACS analysis of Gfp*+ recombinant tetrads. Approximately 1.6 × 105 tetrads were analyzed. (D and E) Schematic and micrographs illustrating the configuration of markers when there is a noncrossover gene conversion (D) or either a gene conversion with an associated crossover or a crossover between the two gfp* mutations (E). (F) Tetrad with two Gfp*+ spores, possibly generated from premeiotic recombination or complex meiotic events. (G) MI nondisjunction, or (expected to be very rare) one class of four-strand double crossover. (H) Map distances (±SE) were calculated for the RFP–CFP interval in strains carrying the construct diagrammed in A. Statistical significance was evaluated by G test for the distribution of tetrad classes for each strain; spo11-HA and spo11-yf were compared to SPO11, whereas the SPO11 strain here was compared to SPO11 in Figure 3.

From a strain heterozygous for the PGPD1-gfp* alleles, ∼1.4% of tetrads contained a Gfp*+ spore(s) (Figure 5C). We sorted Gfp*+ tetrads to enrich for recombinants and then scored the flanking marker configurations by microscopy (Figure 5, D and E). In 61.5% of Gfp*+ tetrads from a wild-type strain, the Gfp*+ spore had a nonparental (crossover) configuration of flanking markers (Table 2A and Figure 5E).

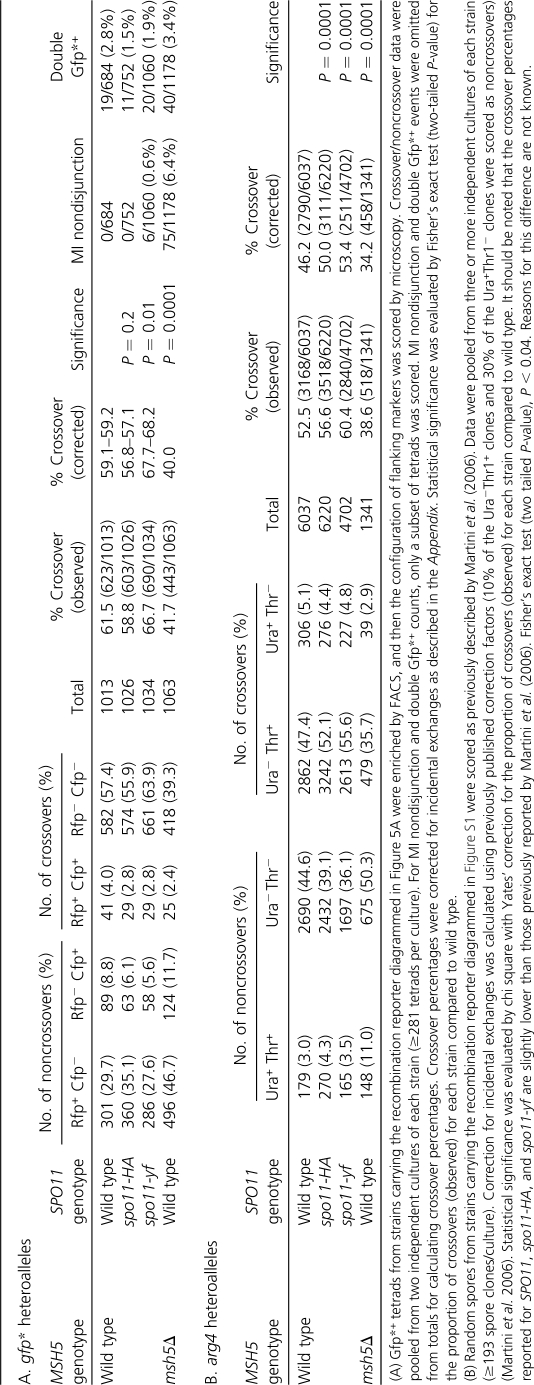

Table 2. Heteroallele recombination assays for crossovers and noncrossovers.

We also analyzed a msh5Δ strain. By FACS, fewer Gfp*+ counts were observed on a per-cell basis (0.22%). This lower apparent recombination frequency is at least partly due to reduced sporulation efficiency (56% for msh5Δ vs. >90% for wild type at 30°). Cells that fail to form spores inflate the apparently nonrecombinant population when scored by FACS. Nonetheless, it was possible to rapidly score crossover and noncrossover outcomes in this mutant. Among sorted tetrads with a Gfp*+ spore, that spore had a crossover configuration of flanking markers 41.7% of the time (Table 2A), which is significantly decreased relative to wild type but similar to results using the arg4 heteroallele assay (Table 2B). This result is as expected from the reduced crossover frequency in the msh5Δ mutant.

Crossover homeostasis:

Cells that experience lower numbers of DSBs compensate by having a higher percentage of breaks that become crossovers (Martini et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2008; Roig and Keeney 2008). This phenomenon, known as crossover homeostasis, can be assayed using arg4 heteroalleles in a series of spo11 hypomorphic mutants with reduced DSB formation: the fraction of Arg+ recombinants that have a crossover configuration increases as Spo11 activity decreases (Martini et al. 2006) (Table 2B). To evaluate utility of the gfp* heteroalleles, we examined recombination in spo11-HA/spo11-HA (hereafter, spo11-HA) and heterozygous spo11-Y135F-HA/spo11-HA (hereafter, spo11-yf) mutant strains. In tetrads from a spo11-yf strain, where DSBs globally are reduced to ∼30% of wild-type levels (Martini et al. 2006), the fraction of Gfp*+ spores with a crossover configuration was 66.7%, significantly higher than in SPO11+ (Table 2A). Thus, PGPD1-gfp* heteroalleles can display the altered recombination outcomes diagnostic of crossover homeostasis. Interestingly, however, the crossover fraction was not increased in the spo11-HA strain (in which global DSBs are ∼80% of wild type), unlike with the arg4 heteroalleles (compare Table 2, A and B). Possible reasons for this difference are addressed in the Discussion.

Crossover homeostasis can also be assessed by comparing genetic distances in wild type and spo11 hypomorphs (Martini et al. 2006). In unselected tetrads (i.e., irrespective of whether a Gfp*+ recombinant had formed), no significant difference was observed between SPO11+ and spo11-HA strains in the CEN8::RFP–THR1::CFP interval (Figure 5H). This result is consistent with the occurrence of crossover homeostasis.

Evaluating incidental exchanges:

When recombination generates a functional GFP* allele, the linkage of the flanking markers on the GFP*-bearing chromatid can be altered by a second recombination event (specifically, a crossover) within the RFP–CFP interval. Such incidental exchanges can cause a noncrossover Gfp*+ conversion to appear to be a crossover or, conversely, “erase” a crossover at gfp*. Incidental exchanges thus complicate estimates of what fraction of recombination events yield a crossover.

This issue could be addressed with the arg4 heteroalleles because of inclusion of nearby NdeI restriction site polymorphisms (Figure S1) (Martini et al. 2006). A crossover associated with an Arg+ conversion usually exchanges the NdeI polymorphisms along with the more distant markers, whereas incidental exchange outside the region between the NdeI sites would leave a parental NdeI configuration (for more detail, see figure S1 of Martini et al. 2006). We created gfp* heteroalleles flanked by the same NdeI site polymorphisms (Figure 5A) and determined the configuration of markers in flow-sorted Gfp*+ single-spore clones (Table 3). For the most common crossover configuration (Rfp− Cfp−), 7.0% had a parental configuration of the NdeI sites, consistent with noncrossover conversion of gfp* plus an incidental exchange. Similarly, 6.5% of spores with the most common noncrossover configuration (Rfp+ Cfp−) had the pattern expected for a crossover gfp* conversion that was erased by a second, incidental exchange (Table 3). SPO11+ and spo11-HA strains did not differ significantly (Table 3), consistent with prior findings with arg4 heteroalleles (Martini et al. 2006).

Table 3 . Analysis of incidental crossovers.

| Gfp*+ spore class | NdeI digest (site1/site2) | No. of spore clones (% of class) | Configuration of markers is consistent with: | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPO11+ | spo11-HA | |||

| Rfp− Cfp− | Cut/cut | 67/72 (93.0) | 53/53 (100.0) | Single crossover associated with GFP* conversion |

| Cut/uncut | 2/72 (2.8) | 0/53 | Noncrossover conversion of gfp*-atg with distal incidental exchange | |

| Uncut/cut | 3/72 (4.2) | 0/53 | Noncrossover conversion of gfp*-R215X with proximal incidental exchange | |

| Rfp+ Cfp+ | Uncut/uncut | 2/2 (100.0) | 8/9 (88.9) | Single crossover associated with GFP* conversion |

| Cut/uncut | 0/2 | 1/9 (11.1) | Noncrossover conversion of gfp*-atg with proximal incidental exchange | |

| Rfp+ Cfp− | Uncut/cut | 43/46 (93.5) | 42/45 (93.3) | Noncrossover conversion of gfp*-R215X |

| Cut/cut | 3/46 (6.5) | 3/45 (6.7) | Crossover associated with GFP* conversion with proximal incidental exchange | |

| Rfp− Cfp+ | Cut/uncut | 9/9 (100.0) | 20/23 (87.0) | Noncrossover conversion of gfp*-atg |

| Cut/cut | 0/9 | 2/23 (8.7) | Crossover associated with GFP* conversion with distal incidental exchange | |

| Uncut/uncut | 0/9 | 1/23 (4.3) | Crossover associated with GFP* conversion with proximal incidental exchange | |

Single Gfp*+ spores of the four possible flanking marker configurations were sorted, allowed to grow, and then genotyped for the NdeI sites diagrammed in Figure 5A. Data were pooled from two independent cultures (≥39 spores analyzed per culture). The agreement with expected marker patterns is described for each class.

Determining the configuration of NdeI markers is laborious and time-consuming, making it difficult to compile large data sets and thus reducing statistical power. The fluorescence-based assay circumvents this limitation by allowing estimation of incidental exchange from the segregation patterns in Gfp*+ tetrads (Appendix). By this analysis, 6.9% of observed crossovers and 4.7% of observed noncrossovers appear to be due to incidental exchange in wild type, similar to results from the restriction site assay. Importantly, none of the mutants analyzed in this study were significantly different from wild type in this regard (Appendix).

Resolving segregation classes that are ambiguous in random spore analysis:

An advantage of the gfp* heteroallele assay is that it allows identification of premeiotic and complex meiotic recombination events, which appear as tetrads containing two Gfp*+ spores (Figure 5F). Such events would be indistinguishable from simple conversions in a random spore analysis. The frequency of double Gfp*+ tetrads was similar in all of the strains analyzed (Table 2A, P > 0.1). These tetrads were excluded from further analyses.

Chromosome missegregation can inject ambiguity into a random spore analysis by yielding spore genotypes indistinguishable from certain recombinant configurations. For example, in the arg4 heteroallele assay, Ura+ Arg+ Thr+ spore clones can arise via noncrossover conversion at arg4, or by an Arg+ conversion along with chromosome VIII MI nondisjunction (Figure S1). Effects of this ambiguity are demonstrated in Table 2B: the high frequency of MI nondisjunction in the msh5Δ strain causes it to show a much greater increase relative to wild type in the Ura+ Thr+ noncrossover class (3.7-fold) than in the Ura− Thr− noncrossover class (1.1-fold). Additional tests (e.g., directly measuring ploidy) are required to resolve this ambiguity and to accurately measure crossover:noncrossover ratios.

The fluorescence-based recombination assay circumvents this issue because segregation of all four chromatids can be followed, allowing ready detection of MI nondisjunction (Figure 5G). MI nondisjunction was not observed in the SPO11 and spo11-HA strains (<0.15%), but occurred at a low frequency in the spo11-yf strain (Table 2A) as expected from its reduced spore viability (Diaz et al. 2002). MI nondisjunction was elevated in a msh5Δ mutant as expected, but the frequency was lower than with the missegregation-specific assay described above (compare Table 2A and Figure 2B). The reason for the discrepancy is that we selected tetrads with a detectable recombination event at gfp*, many of which successfully experienced a crossover that can promote proper segregation of chromosome VIII. If we disregard the crossover tetrads (443/1138) and assume that the remainder have a nondisjunction probability of 0.108 (see Figure 2B), then we expect to recover 75 MI nondisjunction events, precisely as observed (Table 2A). Reasoning in the opposite direction, the MI nondisjunction frequency that would have been observed in unselected tetrads can be estimated as NDJobs/(total − COobs), where NDJobs is the observed number of nondisjunction tetrads and COobs is the number of tetrads with a crossover configuration for the Gfp*+ spore.

Discussion

Here we have shown that recombination and chromosome missegregation can be scored in tetrads largely independently of spore viability by using a set of spore-autonomous fluorescent constructs. For these analyses, the rate-limiting step is moving mutations of interest into the fluorescent tester strains. Once strain construction is completed, a comprehensive analysis can be performed in ∼2 hr following sporulation (500 events counted per hour). The system is potentially amenable to automated scoring, which would further increase throughput. Removing tetrad dissection and subsequent scoring as rate-limiting steps opens the door to rapidly interrogating strains under a wide variety of environmental conditions, which is of interest given that temperature and other factors are known to affect meiotic chromosome dynamics in wild-type and certain mutants (Abdullah and Borts 2001; Börner et al. 2004; Chan et al. 2009; Cotton et al. 2009).

The fluorescent constructs that we developed are modular and portable, allowing one to rapidly tailor the assays described here to different genomic regions. Another advantage of using spore-autonomous cassettes is that the addition of a third fluorescent marker allows for chromosome missegregation and crossover frequency to be scored simultaneously. A different method to follow meiotic chromosome segregation involves visualizing the binding of LacI-GFP to an array of lac operator (lacO) sequences integrated near the centromere of a particular chromosome (Straight et al. 1996). This system permits rapid analysis of MI nondisjunction and PSSC and MII nondisjunction and, unlike spore-autonomous fluorescent protein expression, the segregation of marked chromosomes can be followed in real time. However, our system has complementary advantages over the LacI/lacO system. For example, tandem repeats can influence the position of nucleosomes and transcriptional activity (Vinces et al. 2009), so there is potential for these large repeat arrays to perturb chromosome dynamics, although to our knowledge this issue has not been rigorously tested. In contrast, our fluorescent constructs are smaller and lack repetitive elements, making this method potentially less invasive. Moreover, adding more markers would likely be difficult to achieve with operator arrays, although it is feasible, in principle, given a suitable collection of different operators and fusions of fluorescent proteins to sequence-specific DNA-binding modules.

Recombinants at arg4 and gfp*

Several asymmetries were observed in the recombinant tetrad populations. For example, noncrossover Gfp*+ spores were strongly biased such that 77% had an Rfp+ Cfp− configuration (Table 2A). This is the expected pattern, given the distribution of DSBs relative to the heteroallele sequence polymorphisms and given that the broken chromosome is the recipient of genetic information in a gene conversion event. As noted above, gfp*-R215X is the mutation closest to the nearest DSB site (Figure 5, A and B), so conversion of this mutation to wild type accounts for a majority of the noncrossover Gfp*+ recombinants, which inherit the parental configuration from the original gfp*-R215X chromosome (i.e., Rfp+ Cfp−). DSBs to the right of PGPD1-gfp* are much farther from the gfp*-atg mutation (Figure 5, A and B) and therefore contribute a smaller number of noncrossovers in which the gfp*-atg mutation is converted to wild type, yielding the Rfp− Cfp+ configuration.

Bias was even stronger for crossover Gfp*+ spores, with 93% negative for both RFP and CFP (Table 2A). This pattern is also as expected from the distribution of DSBs. Crossover Gfp*+ recombinants that arise from gene conversion of the gfp*-R215X mutation usually have the crossover breakpoint to the left of the gfp*-atg mutation, which leaves the functional GFP* allele on a chromatid that lacks both flanking markers (Figure 5A). Similarly, crossover Gfp*+ recombinants that arise from gene conversion of the gfp*-atg allele usually have the crossover breakpoint to the right of the gfp*-R215X mutation, which again leaves the functional GFP* allele flanked by neither RFP nor CFP. Finally, functional GFP* can also be generated by crossing over between the two mutations without gene conversion, which would also leave GFP* flanked by neither RFP nor CFP. The stronger bias among crossovers than noncrossovers is explained by the fact that multiple ways to achieve crossover-associated generation of GFP* all favor the same configuration of flanking markers, whereas noncrossover GFP* products have opposite configurations, depending on which allele is converted.

Comparing the gfp* and arg4 assays, we observed a greater fraction of Gfp*+ recombinants with a crossover configuration than was seen for Arg+ recombinants (Table 2, A and B). A possible reason for this difference is discussed below. As previously noted (Martini et al. 2006), arg4 heteroalleles also show biased recovery of particular recombinant configurations (Table 2B). The specific patterns are different for arg4 vs. gfp* [e.g., arg4 heteroalleles showed stronger bias in the noncrossover class (94%) and slightly less bias in the crossover class (90%)], in keeping with the different spatial relationship of DSBs to sequence polymorphisms for the two recombination reporter systems.

Crossover homeostasis and crossover:noncrossover ratios at individual loci

A previous study found that the endogenous ARG4 locus exhibits crossover homeostasis, but the artificial hotspot HIS4LEU2 does not (Martini et al. 2006). We show here that, when DSBs are reduced by spo11 mutation, a different artificial hotspot shows an increased crossover:noncrossover ratio diagnostic of crossover homeostasis. It is possible that HIS4LEU2 does not respond normally to crossover control mechanisms, but an alternative possibility is that DSBs at this site are subject to the same control mechanisms, but are more likely to influence other recombination events nearby than to be influenced by them (Martini et al. 2006). In any case, our results demonstrate that the spore-autonomous fluorescence cassettes are amenable to detecting and quantifying crossover homeostasis.

Interestingly, however, the gfp* heteroalleles did not show altered crossover:noncrossover ratios in the spo11-HA background. Why is gfp* different from arg4 in this respect? One possibility is that the fluorescent protein expression cassettes alter the ability of the CEN8-THR1 genomic interval to experience decreased DSB formation in response to this spo11 mutation. Although the spo11-HA allele appears to reduce DSBs to a roughly similar degree in many locations, locus-specific differences have been documented (Martini et al. 2006).

Another possibility lies in the different ways that the gfp* and arg4 heteroallele systems are affected by gene conversion tract lengths. The majority of Arg+ conversions are generated from DSBs within the arg4 promoter, averaging ∼185 bp from the mutation that is most frequently converted (Nicolas et al. 1989; Martini et al. 2006; Pan et al. 2011). Most conversion tracts must thus extend at least 185 bp and no more than ∼1465 bp (to prevent co-conversion of the second mutation, which would result in an Arg− recombinant). In contrast, most Gfp*+ conversions are generated either from a DSB site ∼50–200 bp to the left of the gfp*-R215X mutation or, less frequently, from a DSB site located ∼900–1100 bp to the right of the gfp*-atg mutation. The two gfp* mutations are 641 bp apart. Most detectable conversions thus have tract lengths between 50 and 841 bp or between 900 and 1741 bp. Both single-locus and whole-genome studies have shown that the median conversion tract length is longer for crossovers (∼2.0 kb) than for noncrossovers (∼1.8 kb) (Borts and Haber 1989; Chen et al. 2008; Mancera et al. 2008). The lengths of individual conversion tracts vary over a wide range, however. The gfp* heteroalleles detect a narrower subset of possible conversion events than the arg4 heteroalleles, which may account for why these reporters yield different fractions of crossover-associated recombinants in wild type (Table 2, A and B). In principle, then, these recombination reporters may respond differently if the distribution of conversion tract lengths changes in a mutant and, in particular, if crossover and noncrossover tract lengths are differentially affected. Determining whether this scenario can account for the different effect of the spo11-HA mutation on crossing over at arg4 vs. gfp* will require testing whether distributions of conversion tract lengths are altered in spo11-HA strains. One approach to reduce the impact of conversion tract length (and thus the frequency of co-conversions) is to measure non-Mendelian segregation (1:3 or 3:1, i.e., gene conversion) in strains heterozygous for a wild-type fluorescent protein allele and an allele with a single point mutation.

Future applications

A fluorescence-enabled dissection scope would make it possible to isolate and grow spores with interesting recombination events. There is also ample precedent that genomic regions can differ from one another in basic recombination patterns and in responses to perturbations or to mutations in trans-acting factors (Borts and Haber 1989; Martini et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2008; Mancera et al. 2008; Zanders and Alani 2009). Although only a single chromosome and set of loci are described here for each assay, the adaptability and portability of the spore-autonomous expression cassettes opens up essentially any portion of the genome to interrogation. Finally, we note that, with application of high-throughput fluorescence imaging techniques, these constructs could also be used as a quantitative phenotypic output for forward genetic screens.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sean Burgess, Owen Hughes, and Kelly Komachi for sharing information and constructs for spore-autonomous expression prior to publication. We thank Jan Hendrikx and Jennifer Wilshire of the Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM058673. S.K. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Appendix: Estimating Frequencies of Incidental Exchanges from Gfp*+ Tetrad Data

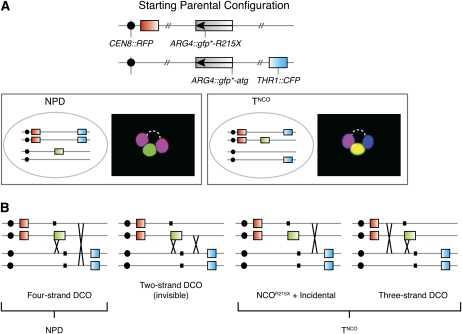

Because we can assess all four spores, we can evaluate the occurrence of Gfp*+ recombinants that are incorrectly scored because of incidental exchanges. Two classes of tetrad are informative for this purpose: those with a NPD configuration of RFP and CFP and those that are tetratype for RFP and CFP but have a noncrossover configuration of the Gfp*+ chromatid (TNCO) (Figure A1A). NPD tetrads arise from two crossovers involving all four chromatids (four-strand double crossover; Figure A1B). TNCO tetrads can arise from a noncrossover gfp* conversion plus a separate crossover involving the GFP*-bearing chromatid’s sister or from a subset of cells that experienced two crossovers involving three chromatids (three-strand double crossovers) (Figure A1B).

Figure A1 .

Classification of Gfp*+ tetrads with at least two detectable recombination events. (A) Schematic of parental marker configuration and schematic representations and micrographs illustrating the configuration of markers when a recombination event at gfp* is associated with a second recombination event in the CEN8–THR1 interval. The two informative classes of tetrads (NPD and TNCO) are shown. (B) NPDs arise from two crossovers between CEN8 and THR1 involving all four chromatids [four-strand double crossovers (DCO)]. TNCO tetrads arise from noncrossover (NCO) gene conversion (either NCOR215X or NCOatg) plus an incidental crossover or from a subset of three-strand DCOs (see Figure A2). Tetrads that have a crossover Gfp*+ recombinant plus an incidental crossover involving the same pair of chromatids (two-strand DCO) are indistinguishable from NCO gene conversion; i.e., they have “invisible” crossovers. Small black boxes represent positions of the gfp*-R215X and gfp*-atg mutations.

The NPD and TNCO tetrad classes are indicative of meioses where at least two separate recombination events occurred within the genetic interval of interest. Thus, examining the frequencies of these tetrad classes provides a simple test to determine whether it is likely that different strains or different experiments display variability in the frequency of incidental exchanges. By this criterion, neither the spo11 hypomorphs nor the msh5Δ strain was significantly different from wild type (Table A1). This result suggests that we need not worry that our ability to evaluate changes in crossover:noncrossover ratios is compromised by variable frequencies of incidental exchange.

Table A1. Frequency of tetrads with at least two detectable recombination events.

| MSH5 genotype | SPO11 genotype | No. of NPD (%) | No. of TNCO(%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Wild type | 4/462 (0.9) | 24/462 (5.2) |

| spo11-HA | 9/745 (1.2), P = 0.78 | 44/745 (5.9), P = 0.70 | |

| spo11-yf | 16/743 (2.2), P = 0.11 | 44/743 (5.9), P = 0.70 | |

| msh5Δ | Wild type | 6/766 (0.8), P = 1.00 | 31/766 (4.0), P = 0.39 |

Gfp*+ tetrads were enriched by FACS from one culture for wild type, spo11-HA, and spo11-yf and from two independent cultures for msh5Δ (≥302 tetrads analyzed per culture). Statistical significance was evaluated by a Fisher’s exact test (two-tailed P-value) that compared each strain to wild type. Note that the observed NPDs may underrepresent total NPDs because a small fraction of tetrads that appear to display MI nondisjunction (Figure 5G) could have arisen from a four-strand double crossover instead. Such NPD tetrads are expected to be exceedingly rare, however, because they contain a Gfp*+ spore that is also Rfp+ Cfp+, which is an uncommon configuration (≥14-fold less common than the Rfp− Cfp−configuration; see Table 2A). All such tetrads were thus scored as “MI nondisjunction.”

Nevertheless, the data allow us to quantitatively estimate the contribution of incidental exchanges. In the discussion that follows, we will consider only situations with a maximum of two recombination events in the RFP–CFP interval per tetrad (either two crossovers or one noncrossover at gfp* plus a crossover somewhere else). Our goal is to estimate the frequency of true crossover-associated Gfp*+ recombinants (COtrue). To do so, we must correct the observed frequency of crossovers (COobs) by adding back tetrads in which a crossover at GFP* was erased by incidental exchange and by removing tetrads in which an incidental exchange falsely caused a GFP* noncrossover to appear to be a crossover:

| . | (A1) |

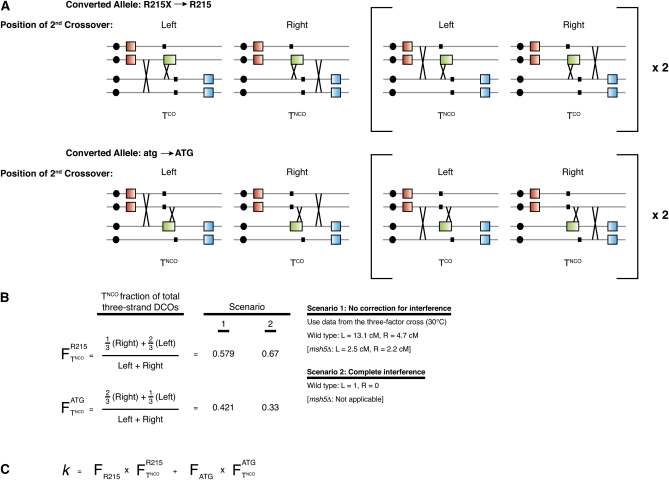

There are two configurations by which an incidental exchange can erase a crossover at GFP*. First, the incidental exchange can involve the same two chromatids as at GFP* (a two-strand double crossover; Figure A1B). Such events are indistinguishable from tetrads in which only a noncrossover conversion has occurred. Second, the incidental exchange can include one of the chromatids involved in the GFP* crossover, plus a different chromatid (three-strand double crossover). All three-strand double crossovers yield a tetratype configuration of RFP and CFP, but only a subset show a false noncrossover arrangement of the Gfp*+ chromatid, depending on which gfp* allele is converted, which chromatids cross over, and whether the second crossover occurs to the left or the right of the crossover at GFP* (see Figure A2A).

Figure A2 .

Estimating the fraction (k) of three-strand DCOs that erase a crossover at GFP*. (A) Schematic representations of three-strand DCOs, all of which give rise to a tetratype (T) configuration of RFP and CFP. A subset has the same configuration as noncrossover GFP* conversion plus an incidental exchange (TNCO), and the remainder look like tetrads with just a single crossover (TCO). Which configuration arises depends on three factors: which gfp* allele is converted to GFP*, whether the incidental exchange occurs to the right or the left of the crossover at GFP*, and which chromatids are involved in the two crossovers. Each situation is diagrammed separately. Events diagrammed inside the brackets (Right) are three-strand DCOs where the incidental exchange involves the gene-converted chromatid’s sister. In the absence of chromatid interference, these events are expected to occur at twice the frequency of three-strand DCOs where the incidental exchange involves the gene-converted chromatid not bracketed. (B) The fraction () of three-strand DCOs expected to have a TNCO configuration is calculated for each converted allele separately. For conversion of gfp*-R215X, a TNCO configuration is expected for one-third of the tetrads with the incidental exchange located to the right side and for two-thirds of the tetrads that have incidental exchange located to the left. Thus, = [1/3⋅(right exchange) + 2/3⋅(left exchange)] ÷ total. Similar logic is applied to calculate the fraction of TNCO for conversion of gfp*-atg (). To estimate the likelihood of right-side incidental exchange vs. left-side, we considered scenarios that ignore crossover interference or that assume strong interference (see Appendix text and B, Right). (C) k is estimated by multiplying the fraction of three-strand DCOs that appear as TNCO for each allele () by the fraction of all conversions that are converted for that allele () and then summing the contributions for the two alleles.

Thus, the number of erased crossovers can be estimated as the number of two-strand double crossovers plus the fraction of three-strand double crossovers that did in fact erase the crossover at GFP* [we use k (0 ≤ k ≤ 1) to denote this fraction]. If we assume that there is no chromatid interference (Chen et al. 2008), then two-strand double crossovers occur at the same frequency as four-strand double crossovers, i.e., NPDs. Moreover, the frequency of all three-strand double crossovers should be twice the frequency of four-strand double crossovers. Thus:

| . | (A2) |

False crossovers (noncrossover at GFP* plus an incidental exchange involving the Gfp*+ chromatid) are indistinguishable from tetrads with a single crossover-associated conversion, and thus their number cannot be directly measured. However, in tetrads that experienced a noncrossover at GFP* plus an independent crossover, there is equal likelihood of the crossover involving the GFP*-bearing chromatid or its sister. As described above, the latter event gives rise to a TNCO tetrad, so the frequency of false Gfp*+ crossovers should equal the frequency of TNCO tetrads after subtracting those TNCO tetrads that arise from three-strand double crossovers and that appear to be noncrossover at GFP* (see above). Thus:

| . | (A3) |

Substituting into equation 1 and rearranging yields:

| . | (A4) |

The value of k depends on multiple factors, most importantly the conversion frequency for each allele and the likelihood of an incidental exchange being to the right or the left of the GFP* conversion (Figure A2, B and C); k will thus differ for different recombination reporter setups. To estimate its value for our system, we assumed that the relative frequency of conversion of the gfp*-R215X allele vs. the gfp*-atg allele equals the relative frequency of Rfp+ vs. Cfp+ noncrossover spores (see Recombinants at art4 and gfp* and Table 2A). Next, we assumed that the likelihood of the second crossover being to the left or the right of the crossover at GFP* is proportional to the RFP–GFP* (13.1 cM) vs. GFP*–CFP (4.7 cM) distances measured in the three-factor cross in Figure 4. Under these assumptions, k = 0.543 for the wild-type strain using the equation in Figure A2C. An alternative assumption would be that crossover interference disfavors instances where the second crossover falls in the shorter genetic interval to the right of the heteroalleles. Under this assumption, k = 0.591.

Table A2 shows values of k estimated from tetrad data from wild type, the two spo11 hypomorphs, and msh5Δ. Corrected estimates of the fraction of crossover-associated Gfp*+ recombinants are provided in Table 2A. Several conclusions emerge. First, different assumptions had little effect on the estimate of k and thus had little effect on the magnitude of the correction in the crossover fraction. Second, the estimates of incidental exchange frequencies from tetrad data agreed well with results from NdeI restriction site analysis. For example, in wild type, 6.8–6.9% of observed crossovers were estimated to be due to incidental exchange [i.e., (TNCO − k⋅2⋅NPD)/COobs], similar to the 7.0% measured by the NdeI assay (Table 3). Third, this analysis suggests that incidental exchanges contribute very little quantitatively to the observed crossover vs. noncrossover ratio. This is in part because the total number of such events is small, but also because false crossovers and erased crossovers largely cancel one another out. As a consequence, robust conclusions about alterations of crossover:noncrossover ratios can be drawn from the uncorrected data. Nonetheless, the ease of executing the tetrad-based evaluation of incidental exchanges allows one to readily address this issue for each mutant, experimental condition, or arrangement of recombination reporters.

Table A2. Estimates of values of k from tetrad data.

| Strain | k1 | k2 | COobs | Total | %COobs | %COcorr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 0.543 | 0.591 | 623 | 1013 | 61.5 | 59.1–59.2 |

| spo11-HA | 0.555 | 0.617 | 603 | 1026 | 58.8 | 56.8–57.1 |

| spo11-yf | 0.552 | 0.610 | 690 | 1034 | 66.7 | 67.7–68.2 |

| msh5Δ | 0.507 | NAa | 443 | 1063 | 41.7 | 40.0 |

Values of k were calculated for scenario 1 (k1) and 2 (k2) (Figure A2B) using the formula in Figure A2C. The corrected fraction of GFP* conversions that are crossover associated (%COcorr) was calculated using Equation 4.

Because msh5Δ strains do not show crossover interference, k2 (calculated assuming complete interference) is not applicable.

Literature Cited

- Abdullah M. F., Borts R. H., 2001. Meiotic recombination frequencies are affected by nutritional states in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98: 14524–14529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchowitz L. E., Copenhaver G. P., 2008. Fluorescent Arabidopsis tetrads: a visual assay for quickly developing large crossover and crossover interference data sets. Nat. Protoc. 3: 41–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borde V., Wu T. C., Lichten M., 1999. Use of a recombination reporter insert to define meiotic recombination domains on chromosome III of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 4832–4842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börner G. V., Kleckner N., Hunter N., 2004. Crossover/noncrossover differentiation, synaptonemal complex formation, and regulatory surveillance at the leptotene/zygotene transition of meiosis. Cell 117: 29–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borts R. H., Haber J. E., 1989. Length and distribution of meiotic gene conversion tracts and crossovers in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 123: 69–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. C., Borts R. H., Hoffmann E., 2009. Temperature-dependent modulation of chromosome segregation in msh4 mutants of budding yeast. PLoS ONE 4: e7284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. Y., Tsubouchi T., Rockmill B., Sandler J. S., Richards D. R., et al. , 2008. Global analysis of the meiotic crossover landscape. Dev. Cell 15: 401–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton V. E., Hoffmann E. R., Abdullah M. F., Borts R. H., 2009. Interaction of genetic and environmental factors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae meiosis: the devil is in the details. Methods Mol. Biol. 557: 3–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz R. L., Alcid A. D., Berger J. M., Keeney S., 2002. Identification of residues in yeast Spo11p critical for meiotic DNA double-strand break formation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22: 1106–1115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis K. E., Lam S. Y., Harrison B. D., Bey A. L., Berchowitz L. E., et al. , 2007. Pollen tetrad-based visual assay for meiotic recombination in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 3913–3918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon O., Taxis C., Keller P. J., Benjak A., Stelzer E. H., et al. , 2006. Nud1p, the yeast homolog of Centriolin, regulates spindle pole body inheritance in meiosis. EMBO J. 25: 3856–3868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesbeck O., Baird G. S., Campbell R. E., Zacharias D. A., Tsien R. Y., 2001. Reducing the environmental sensitivity of yellow fluorescent protein. Mechanism and applications. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 29188–29194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley R. S., 2007. Meiosis in living color: fluorescence-based tetrad analysis in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 3673–3674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth N. M., Ponte L., Halsey C., 1995. MSH5, a novel MutS homolog, facilitates meiotic reciprocal recombination between homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae but not mismatch repair. Genes Dev. 9: 1728–1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G. H., 1984. The control of chiasma distribution. Symp. Soc. Exp. Biol. 38: 293–320 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney S., Giroux C. N., Kleckner N., 1997. Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88: 375–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn R. R., Magee P. T., 1970. Development of the spore wall during ascospore formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 44: 688–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malkova A., Swanson J., German M., McCusker J. H., Housworth E. A., et al. , 2004. Gene conversion and crossing over along the 405-kb left arm of Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome VII. Genetics 168: 49–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mancera E., Bourgon R., Brozzi A., Huber W., Steinmetz L. M., 2008. High-resolution mapping of meiotic crossovers and non-crossovers in yeast. Nature 454: 479–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston A. L., Amon A., 2004. Meiosis: cell-cycle controls shuffle and deal. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5: 983–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini E., Diaz R. L., Hunter N., Keeney S., 2006. Crossover homeostasis in yeast meiosis. Cell 126: 285–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mell J. C., Komachi K., Hughes O., Burgess S., 2008. Cooperative interactions between pairs of homologous chromatids during meiosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 179: 1125–1127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens P. B., 1971. Fine structure of ascospore development in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Can. J. Microbiol. 17: 507–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H., Borde V., Nicolas A., Keeney S., 2009. Gel electrophoresis assays for analyzing DNA double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae at various spatial resolutions. Methods Mol. Biol. 557: 117–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neiman A. M., 2005. Ascospore formation in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 69: 565–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas A., Treco D., Schultes N. P., Szostak J. W., 1989. An initiation site for meiotic gene conversion in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 338: 35–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishant K. T., Chen C., Shinohara M., Shinohara A., Alani E., 2010. Genetic analysis of baker’s yeast Msh4-Msh5 reveals a threshold crossover level for meiotic viability. PLoS Genet. 6: pii: e1001083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page S. L., Hawley R. S., 2003. Chromosome choreography: the meiotic ballet. Science 301: 785–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan J., Sasaki M., Kniewel R., Murakami H., Blitzblau H. G., et al. , 2011. A hierarchical combination of factors shapes the genome-wide topography of yeast meiotic recombination initiation. Cell 144: 719–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig I., Keeney S., 2008. Probing meiotic recombination decisions. Dev. Cell 15: 331–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J. C., Guarente L., 1991. Vectors for expression of cloned genes in yeast: regulation, overproduction, and underproduction. Methods Enzymol. 194: 373–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski R. S., Hieter P., 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122: 19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden T., Acharya S., Butz C., Berardini M., Fishel R., 2004. hMSH4-hMSH5 recognizes Holliday Junctions and forms a meiosis-specific sliding clamp that embraces homologous chromosomes. Mol. Cell 15: 437–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straight A. F., Belmont A. S., Robinett C. C., Murray A. W., 1996. GFP tagging of budding yeast chromosomes reveals that protein-protein interactions can mediate sister chromatid cohesion. Curr. Biol. 6: 1599–1608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym M., Roeder G. S., 1994. Crossover interference is abolished in the absence of a synaptonemal complex protein. Cell 79: 283–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinces M. D., Legendre M., Caldara M., Hagihara M., Verstrepen K. J., 2009. Unstable tandem repeats in promoters confer transcriptional evolvability. Science 324: 1213–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach A., Brachat A., Pohlmann R., Philippsen P., 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10: 1793–1808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T. C., Lichten M., 1995. Factors that affect the location and frequency of meiosis-induced double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 140: 55–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanders S., Alani E., 2009. The pch2Δ mutation in baker’s yeast alters meiotic crossover levels and confers a defect in crossover interference. PLoS Genet. 5: e1000571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]