Abstract

Background

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) is a B cell malignancy with a variable clinical course and unpredictable response to therapeutic agents. Single cell network profiling (SCNP) utilizing flow cytometry measures alterations in signaling biology in the context of molecular changes occurring in malignancies. In this study SCNP was used to identify proteomic profiles associated with in vitro apoptotic responsiveness of CLL B cells to fludarabine, as a basis for ultimately linking these with clinical outcome.

Methodology/Principal Finding

SCNP was used to quantify modulated-signaling of B cell receptor (BCR) network proteins and in vitro F-ara-A mediated apoptosis in 23 CLL samples. Of the modulators studied the reactive oxygen species, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a known intracellular second messenger and a general tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor stratified CLL samples into two sub-groups based on the percentage of B cells in a CLL sample with increased phosphorylation of BCR network proteins. Separately, in the same patient samples, in vitro exposure to F-ara-A also identified two sub-groups with B cells showing competence or refractoriness to apoptotic induction. Statistical analysis showed that in vitro F-ara-A apoptotic proficiency was highly associated with the proficiency of CLL B cells to undergo H2O2-augmented signaling.

Conclusions/Significance

This linkage in CLL B cells among the mechanisms governing chemotherapy-induced apoptosis increased signaling of BCR network proteins and a likely role of phosphatase activity suggests a means of stratifying patients for their response to F-ara-A based regimens. Future studies will examine the clinical applicability of these findings and also the utility of this approach in relating mechanism to function of therapeutic agents.

Introduction

CLL is the most common adult leukemia in the Western world and is characterized by aberrant accumulation of CD5+ B lymphocytes in the peripheral blood, bone marrow and secondary lymphoid organs. Clinical presentation, natural course of the disease and response to treatment are all extremely variable, with patient survival after diagnosis ranging from months to decades. Although the biological mechanisms accounting for the unpredictability of the disease are unknown, several biological indicators including cytogenetics, presence or absence of somatic mutations within the immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region (IgVH), ZAP70 and CD38 expression have all been associated with response to therapy and prognosis [1]–[3].

A greater understanding of CLL biology is needed to chart disease progression as well as assist in selecting optimal therapeutic strategies. Ideally, monitoring on an individual patient basis would take into account differing inter-patient cell biology as well as shifts in the intra-patient population biology of mutant cells within a heterogeneous tumor cell population. SCNP studies in myeloid leukemias and follicular lymphoma distinguished healthy from diseased cells by their response to growth factors and cytokines [4]–[10]. In these studies induced protein phosphorylation was shown to be more informative than the frequently measured basal phosphorylation state of a protein revealing signaling deregulation consequent to the numerous cytogenetic, epigenetic and molecular changes characteristic of transformed cells. Furthermore, SCNP simultaneously measures multiple signaling proteins and assigns their activation states to specific cell sub-sets within complex primary cell populations [11].

Central to B cell development, and also believed to be important in CLL progression, is the BCR signal complex composed of membrane-bound immunoglobulin and the signal transducing CD79α/CD79β heterodimer. In normal B cells, antigen mediated BCR activation regulates cell survival, differentiation, proliferation and migration [12], [13]. Additional regulation of BCR signaling involves phosphatase(s) whose activity is regulated by NADPH-oxidase-generated reactive oxygen species H2O2 [14]–[16]. Furthermore, studies from the groups of Munroe and Rajewsky have recognized that in conjunction with antigen-driven responses, ligand-independent signaling (tonic signaling) by both the pre-B cell receptor and BCR has an important role in survival throughout B cell development [17]–[20]. Although the molecular mechanisms governing tonic BCR signaling are not well defined, recent studies suggest that tyrosine phosphatase regulation by reactive oxygen species play a likely role [14], [16], [17], [21]–[23]. Furthermore, recent evidence has described deregulated tonic BCR signaling in diffuse large B cell lymphoma and CLL [24]–[28].

In CLL, associations have been observed between the clinical course of the disease and functional alterations in the BCR and its regulators, suggesting that both antigen-driven and tonic BCR signaling play an important role in its pathogenesis. This is corroborated by in vitro studies in which significant differences in both ligand-mediated and ligand-independent BCR signaling were found in primary CLL patient samples [25], [29].

In a healthy physiological setting, apoptosis proceeds from sensors that monitor cell stress and damage, to effectors that relay the signals to activate programmed cell death pathways. Apoptosis is also regulated by cell survival signals, and in B cells one such set of signals emanates from the BCR via tonic signaling, as noted above. The accumulation of malignant monoclonal B cells in CLL has largely been attributed to defects in apoptosis cascades rather than to aberrant proliferation [30]. In some CLL patients inactivation of cell death pathway proteins such as p53 (17p deletion) is an example of how this mechanism can over-ride benefit from a therapeutic agent [31]. No relationship between BCR signaling, cell survival and resistance of patient cells to chemotherapy has yet been shown using existing analytical methods. SCNP technology now provides an opportunity to re-examine the global alterations in signaling that inevitably occur in B cells in response to the genetic and molecular changes they have sustained.

Materials and Methods

Ethics statement

All patients consented, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, for the collection and use of their samples for institutional review board-approved research purposes.

Patient samples

Cryopreserved, Ficoll-purified (Sigma Aldrich) [32] peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 23 CLL and 7 healthy subjects were used in this study (Table 1). The majority of samples were collected from patients previously treated. CLL diagnosis was based on the Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia criteria [33].

Table 1. Clinical and molecular characteristics of patient samples.

| Sample ID | Gender | Age at DX | IgVH | % ZAP 70 | FISH | First Treatment (Rx) Type |

| CLL001 | M | 44 | 93 | 0.4 | Not available | HDMP+Rituxan |

| CLL003 | F | 53 | 92.6 | 0.6 | Not available | FR (2cycles) - good response |

| CLL004 | M | 53 | 100 | 92.5 | 11qdel(16%) | HDMP Rituxan Frontline (3 cycles) |

| CLL005 | M | 65 | 98.6 | 43.6 | tri12 (90%) | Leukeran (4 mg/day) |

| CLL006 | F | 61 | 99.6 | 45.2 | normal FISH | F; then FR (4 cyc) - MRD on BM |

| CLL007 | M | 66 | 99.3 | 79.1 | tri 12 (84%) | Leukeran |

| CLL008 | M | 72 | 95.8 | 3 | 13q del (73%) | Leukeran |

| CLL009 | M | 81 | 95.2 | 9.8 | 13q del (100%) | Chloroambucil |

| CLL010 | M | 48 | 89 | 5 | Not available | Fludarabine (3 cycles) |

| CLL011 | M | 57 | 93.3 | 1.1 | tri 12(75%) | ASCENTA-002 |

| CLL012 | F | 72 | 96.8 | 1.2 | Not available | no Rx |

| CLL013 | M | 59 | 99.6 | 62.8 | tri 12(89%) | Chlorambucil |

| CLL014 | M | 54 | 90.5 | 0.5 | tri 12 (karyotype) | High dose chemoRx w/BM transplant |

| CLL015 | F | 51 | 100 | 91.9 | tri 12 (82%) | ASCENTA-002 |

| CLL016 | F | 53 | 93 | 0.1 | Normal FISH | HDMP+R 04 Frontline |

| CLL017 | F | 39 | 96.1 | 10.1 | Normal Karyotype | no Rx |

| CLL018 | M | 55 | 100 | 91.1 | 13qdel(70%) | HDMP+R 04 (3 cycles) Frontline |

| CLL019 | M | 50 | 100 | 45.9 | Normal FISH | Rituximab (3 cycles) - 4 weeks |

| CLL020 | M | 43 | 91.9 | 1.1 | 13 del (99%) | Chlorambucil |

| CLL021 | M | 66 | 100 | 65.3 | 13 del (99%) | Solumedrol Rituxan |

| CLL022 | M | 48 | 100 | 73.1 | tri 12 (80%) | no Rx |

| CLL023 | M | 72 | 94.7 | 1.3 | 13 del (17%) | GMCSF and Rituxan |

| CLL024 | F | 49 | 100 | 51.8 | Not available | no Rx |

IgVH mutational status and percent ZAP70-positive cells determined as previously described [62].

Cell preparation

Samples were thawed at 37°C and suspended in RPMI 1640 1% FCS. Viability was measured for an aliquot immediately post thaw with trypan blue. In this sample set viability was greater than 90% for all samples. Amine Aqua (Invitrogen) was used to determine cell viability according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, Amine Aqua was added to all samples before the 2 hour rest and was present throughout the duration of the experimentation. Cells were arrayed in duplicate in 96-deep-well plates at 6.0×105 cells or 8.0×105 cells per well for measurements of BCR signaling and apoptosis respectively. More cells were used for apoptosis assays to get a more reliable measurement over the 48 hours of exposure to F-ara-A. All measurements for signaling and apoptosis were performed in duplicate for each sample and assay performance characteristics noted (manuscript in preparation).

Ramos cell line control

The human Burkitt lymphoma Ramos cell line, a control for BCR signaling, acquired from ATCC was cultured according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Treatment with extracellular modulators of BCR and apoptosis pathways

After a 2 hour rest at 37°C, each sample was treated in bulk for 10 minutes at 37°C with goat polyclonal (F(ab’)2 human anti−μ (anti−μ) or anti−γ (Southern Biotech), final concentration 10 µg/ml or with H2O2, final concentration 3.3 mM. For the combination of anti−μ and H2O2, anti−μ was added first followed by H2O2 [16]. Phorbol Myristate Acetate ((PMA) Sigma), final concentration 400 nM, was used as a control to show that cells were capable of signaling, in this case downstream of Protein Kinase C and in a BCR-independent manner. For apoptosis assays, samples were exposed either to 9-β-D-arabinosyl–2-fluoroadenine (F-ara-A, Sigma-Aldrich), the free nucleoside of fludarabine, final concentration 1μM, staurosporine (Sigma-Aldrich), final concentration 5 µM for 48 and 6 hours respectively or to vehicle (0.05% DMSO) for matching times at 37°C [34], [35].

Cells were fixed with paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 100% ice-cold methanol as previously described [5], [16], [36].

Flow cytometry determinations of BCR and apoptotic pathways

Cells were incubated with panels of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against a core set of B cell phenotypic markers combined with antibodies recognizing intracellular signaling or apoptosis molecules (Table S1). All antibody concentrations were optimized to maximize signal to noise ratio and to minimize non-specific binding. Eleven point titrations (two fold dilutions) were performed with cryopreserved PBMCs from two healthy donors or with the Ramos cell line. For surface antibodies, titrated in PBMCs, the optimal concentration selected is one where the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the signal to noise ratio is maximal between a cell immunophenotype that expresses an epitope versus one that does not. For the antibodies against phospho-specific epitopes, antibody titrations were performed to determine the concentration that gave the maximal signal to noise ratio for fold increase of stimulated over unstimulated signal (median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of stimulated/ MFI unstimulated sample) in cell lines and PBMCs (data not shown). Further determinations of phospho-antibody specificity were determined by pre-blocking the antibody with the phospho-peptide epitope against which the antibodies were generated (data not shown).

Samples processed for cytometry [16], [36] were acquired on a BD FACS Canto II flow cytometer equipped with a high throughput sampler (HTS).

Expression of surface markers on unfixed cells

Cells were incubated with immunophenotypic cocktails (Table S1) before FACS analysis.

Data analysis

Cells gated on light scatter characteristics were evaluated for viability by exclusion of Amine Aqua. Live cells were gated as CD3-/CD20+ to allow for direct comparison of B cells from CLL and healthy samples. The gating scheme is shown in Figure S1. Metrics included median fluorescence intensity (MFI), percentage of positive cells, and mixture-model derived population content and were extracted from CD3-/CD20+ cells. FCS files were analyzed in FlowJo (Treestar, Ashland, OR) version 8.8.2. To display and compare intensity values including negative numbers and correct for large variance with some fluorophores we used the inverse hyperbolic sine (arcsinh) with a cofactor instead of the traditional log10 scale as shown below.

The arcsinh transformation behaves linearly for small values and log-like for larger values. This transformation for fluorescent intensities was computed using the expression:

|

where  is the fluorescent intensity and

is the fluorescent intensity and  is a factor that determines the linear region of the transform. The addition of

is a factor that determines the linear region of the transform. The addition of  term guarantees that the log function will have a positive value even if

term guarantees that the log function will have a positive value even if  is negative.

is negative.

The criteria used to assign apoptotic proficiency to a sample were a two-fold or greater increase in the number of CD3−−/CD20+ cells at 48 hours that were positive for cleaved PARP (c-PARP+) and cleaved Caspase 3 (C-Caspase 3) after exposure to F-ara-A compared to vehicle or to staurosporine compared to vehicle. The criteria to assign apoptotic refractoriness to F-ara-A were a less than two fold change in the number of of CD3−/CD20+ cells at hours that were positive for c-PARP+and c-Caspase3+.

Results

Surface marker characterization and basal phosphorylation states in healthy and CLL B cells

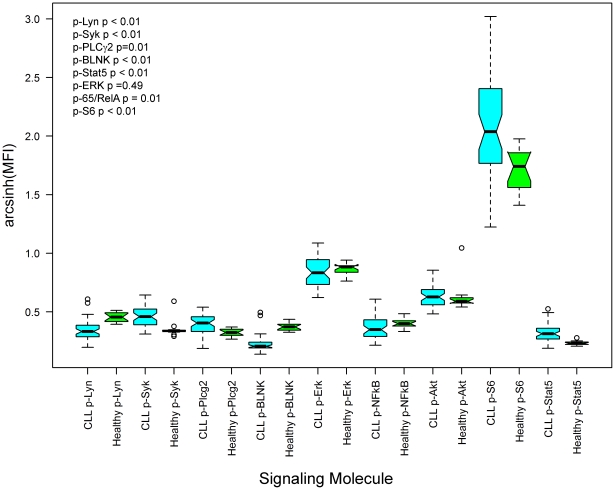

Comparison of MFI values of BCR signaling molecules in their basal phosphorylation states showed greater variability in CLL versus healthy B cells. MFI values for p-Akt and p-Lyn spanned a range of 16 and 17 respectively among healthy B cells and 63 and 66 in CLL B cells (Figure 1 and Table 2). p-Erk and p-65/RelA showed no significant differences between healthy and CLL samples, indicating that at their basal level the activation state of these molecules did not reflect a CLL-dependent phenotype. Although not statistically significant, some samples did have high basal levels of p-65/RelA consistent with previous reports documenting a wide degree of variability for the phosphorylation status of this transcription factor [37] [38]. Similarly, expression (determined by MFI) of B cell lineage markers (CD5, CD19 and CD20) and tyrosine phosphatases (CD45, SHP-1 and SHP-2) also showed greater variability in CLL B cells (Table S2). The expected 2∶1 kappa/lambda ratio was evident in healthy B cells and contrasted with the exclusive expression of either kappa or lambda chain in CLL B cells (data not shown). In 4 samples no light chain, IgM or IgG were detected. Although technical limitations cannot be excluded, the presence of CLL B cell markers such as CD5, CD19 and CD20 suggest these cells to be a clonal B cell population with a CLL phenotype. Expected hallmarks of CLL were seen in the low expression of IgM and CD79βin individual patient samples (Table S2). For CD38 expression most samples were negative but in seven samples, there was a bimodal profile for CD38 expression (data not shown and [39]. No significant separation of CLL samples into distinct subgroups could be made based on expression levels of the measured surface markers or the tyrosine phosphatases.

Figure 1. Basal phosphorylation levels of signaling molecules downstream of the BCR.

Box and whisker plots comparing magnitude and range of basal signaling between CLL (blue) and healthy donors (green). Notch and red horizontal line indicates median signaling for parameter, box drawn from lower to upper quartiles of data, and whiskers extend to 1.5 times the interquartile range. p-values from Student’s t-test comparing Arcsinh transformed MFI values from CLL and healthy B cells.

Table 2. Range of basal phosphorylation levels (MFI) of BCR signaling molecules in CLL and healthy B cells.

| p-Lyn | p-Syk | p-PLCγ2 | p-BLNK | p-Erk | p-65/RelA | p-Akt | p-S6 | p-Stat 5 | ||

| CLL | Range | 66 | 62 | 57 | 50 | 94 | 68 | 63 | 1155 | 43 |

| Mean | 52 | 79 | 63 | 35 | 153 | 56 | 105 | 579 | 51 | |

| Stdev | 14 | 16 | 15 | 11 | 28 | 17 | 16 | 287 | 11 | |

| Healthy | Range | 17 | 16 | 17 | 21 | 41 | 19 | 16 | 198 | 6 |

| Mean | 66 | 55 | 51 | 53 | 157 | 57 | 94 | 377 | 35 | |

| Stdev | 6 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 72 | 2 |

Modulated signaling responses distinguish subgroups of CLL patient samples

To test whether differences in CLL physiology could be discerned based on intracellular signaling responses, cells were treated with extracellular modulators. The modulators chosen were anti−μ to cross link and activate the BCR and H2O2, a mild oxidant produced naturally by healthy B cells to control the strength of antigen receptor signaling by reversible inhibition of tyrosine phosphatases [5], [16] [15] The 10-minute time point for modulator treatment was chosen based on kinetic analyses (data not shown) and produced robust, but not necessarily maximal phosphorylation, of all the BCR pathway signaling molecules under study. The H2O2 concentration chosen was one in which minimal effects were seen on intracellular signaling molecules in healthy B cells (Figure S2) and was consistent with H2O2 concentrations used in other studies [5], [7], [16], [40].

Consistent with previous reports, anti−µ-mediated BCR signaling was observed and further potentiated by H2O2 in B cells from healthy donors (Figure S2) [16].

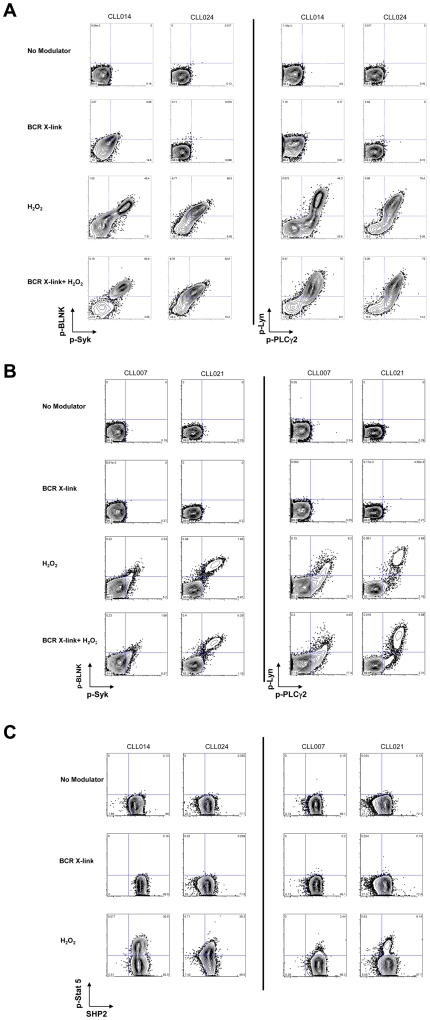

Analysis of the signaling responses showed that the CLL sample cohort was minimally responsive to anti–μ treatment but could be broadly segregated into two patient groups based on their responsiveness to H2O2. In Group l a significant subpopulation of cells was responsive to H2O2 such that there was an anti–μ-independent increase in phosphorylation of signaling molecules downstream of the BCR (the mean percentage of a cell subset with activated p-Lyn, p-Syk, p-BLNK or p-PLCγ2 population was 51%, 52% and 45% and 68% respectively, (Table 3 and Figure 2(A)). Signaling was coordinated in that all these components of the proximal B cell receptor network were augmented in concert. In all but three cases, the addition of anti–µ did not mediate a further increase in measured signaling responses, consistent with the notion that aberrant phosphatase activity might be regulating signaling downstream of the BCR in CLL.

Table 3. BCR and apoptosis responses in CLL and healthy B cells.

| Sample Group | CLL Sample | p-Lyn | p-Syk | p-BLNK | p-Stat 5 | p-PLC–γ | p-Akt | p-Erk | Apoptosis |

| Group I | CLL024 | 80 | 65 | 73 | 47 | 77 | 46 | 88 | +(55) |

| Group 1 | CLL003 | 73 | 74 | 64 | 60 | 81 | 74 | 86 | +(25) |

| Group 1 | CLL008 | 57 | 57 | 47 | 36 | 77 | 67 | 84 | +(9) |

| Group 1 | CLL010 | 56 | 54 | 39 | 30 | 85 | 80 | 90 | +(22) |

| Group 1 | CLL009 | 47 | 63 | 54 | 29 | 79 | 56 | 69 | −(1) |

| Group 1 | CLL014 | 43 | 52 | 52 | 36 | 67 | 59 | 57 | +(28) |

| Group 1 | CLL001 | 40 | 41 | 20 | 34 | 51 | 43 | 52 | +(13) |

| Group 1 | CLL002 | 39 | 39 | 36 | 21 | 56 | 40 | 70 | +(15) |

| Group 1 | CLL016 | 27 | 26 | 17 | 23 | 39 | 56 | 41 | +(20) |

| Group 1 | Mean | 51 | 52 | 45 | 35 | 68 | 58 | 71 | |

| Group 1 | SD | 16 | 14 | 18 | 11 | 15 | 13 | 17 | |

| Group 2 | CLL019 | 24 | 29 | 19 | 12 | 40 | 66 | 53 | −(4) |

| Group 2 | CLL004 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 13 | 45 | 31 | 76 | +(14) |

| Group 2 | CLL018 | 20 | 21 | 18 | 15 | 33 | 45 | 61 | +(17) |

| Group 2 | CLL013 | 19 | 25 | 19 | 13 | 37 | 26 | 27 | +(31) |

| Group 2 | CLL012 | 17 | 32 | 23 | 7 | 48 | 61 | 34 | −(9) |

| Group 2 | CLL005 | 15 | 18 | 10 | 9 | 35 | 74 | 41 | −(3) |

| Group 2 | CLL020 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 33 | 40 | 44 | −(1) |

| Group 2 | CLL023 | 10 | 16 | 14 | 10 | 43 | 87 | 83 | −(8) |

| Group 2 | CLL007 | 8 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 19 | 66 | 40 | −(0) |

| Group 2 | CLL021 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 10 | −(0) |

| Group 2 | CLL011 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 28 | 68 | 19 | −(1) |

| Group 2 | Mean | 14 | 17 | 13 | 9 | 33 | 52 | 44 | |

| Group 2 | SD | 6 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 11 | 23 | 22 | |

| Healthy | CON195 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 3.4 | 18 | 51 | 21 | +(23) |

| Healthy | CON196 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 0.16 | 12 | 48 | 15 | +(21) |

| Healthy | CON219 | 1 | 3.5 | 3 | 0.6 | 25 | 44 | 26 | +(12) |

| Healthy | CON240 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0.6 | 4.5 | 38 | 10 | +(34) |

| Healthy | CON228 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 30.5 | 29 | +(20) |

| Healthy | CON202 | 0.6 | 3 | 5 | 0.6 | 5 | 45 | 17 | +(30) |

| Healthy | CON193 | 0.5 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.3 | 4 | 33 | 6 | + (42) |

| Healthy | Mean | 1.6 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 1.0 | 10.4 | 41.4 | 17.7 | |

| Healthy | SD | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 1.0 | 7.7 | 7.1 | 7.7 | |

| Ramos | 50 | 53 | 88 | 38 | 77 | 85 | 64 | +(21) |

Percentage of B cells from CLL and healthy samples that undergo H2O2-mediated phosphorylation of intracellular signaling molecules. Values are taken from the 2D cytometry plots (Figures S3(A) and (B), S4(B) and (C) and data not shown). Mean and standard deviations are shown for each CLL and healthy sample. CLL samples were segregated into Group 1 and Group 2 based their H2O2-mediated p-Stat5 response which was statistically significant (p-value 1.6×10–4) between the two groups. There was statistical significance for all other signaling molecules between each group (p-values within the range of 3.8×10–5–9×10–3). The exception was H2O2-mediated p-Akt signaling for which the p-value was 0.5. Apoptosis responses to in vitro F-Ara-A exposure are shown as+for proficient and – for refractory according to the criteria described in the Data Analysis section on page 11. The percentage of cells that are positive for cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP at 48 hours after background subtraction are in parentheses.

Figure 2. H2O2 treatment segregates CLL samples into two sub-groups based on magnitude of their signaling responses.

(A) CLL B cells were untreated or exposed to anti–µoranti–γalone, H2O2 alone or the combination for 10 minutes. Representative 2D flow plots show CLL B cell subsets which exhibit (A) robust H2O2–mediated signaling (B) a reduced H2O2–mediated signaling response for proximal BCR signaling molecules. (C) phosphorylation of Stat5 demonstrates either an increased (left-hand columns) or a marginal response (right-hand columns) to H2O2 treatment. The 2D plot has SHP-2 along the X-axis as the SHP-2 antibody was in the same antibody panel.

In Group ll a greatly reduced subpopulation of cells had a signaling response after exposure to H2O2 compared to Group l samples. For example, the mean percentage of cells in a subpopulation with activated p-Lyn, p-Syk, p-BLNK or p-PLCγ2 was 14%, 17%, 13% and 33% respectively (Table 3 and Figure 2(B)).

Interestingly, the H2O2-mediated p-Akt response was similar between the two groups (a mean cell subpopulation of 58% for Group l and 52% for Group ll, Table 3), suggesting that an alternative phosphatase such as the H2O2–sensitive PTEN [41] is not differentially regulated in CLL and healthy B cells. The mean number of cells with activation of Erk in Group ll was less than in Group I (44% and 71% respectively). In healthy B cells, all signaling molecules except Akt were minimally responsive to H2O2 treatment alone (Table 3). Given that H2O2 is a known inhibitor of phosphatase activity, and that phosphatase activation is a physiological regulator of proximal BCR signaling activities [5], [14]–[17], [21]–[23], these data suggest that deregulation of phosphatase activity could explain some of the differences observed between CLL and healthy B cell signaling responses.

Unexpectedly, in 9/23 CLL samples an increase in p-Stat5 was observed in response to H2O2 within a subset of cells in individual samples in Group 1 (Table 3, Figure 2(C)(left hand panels) and Figure S2(A)). In 11/23 CLL samples a minimal number of cells exhibited a H2O2-mediated increase in phosphorylated Stat5 and this was also true for healthy B cells (Table 3, Figure 2(C)(right hand panels, Figure S3(B) and (C)). This observation suggests either that there is a significant re-wiring event downstream of ligand-independent BCR signaling or that an alternative pathway is activated in response to H2O2, and either could be connected to Stat5 activity.

Interestingly, in many patient samples at least two prominent CLL cell populations with unique and definable signaling responses were observed. For example, a sample in which a dominant cell subset demonstrated augmented signaling in response to H2O2, other subsets could be identified with marginal responses (Figure 2(A and C)). No such distinctions were observed using basal phosphorylation states, underscoring that activation of BCR signaling molecules highlights the differences in pathway biology between and within samples.

Lack of responsiveness of the Lyn/Syk/BLNK/PLCγ2 signaling proteins to H2O2 treatment associated with lack of apoptotic response to F-ara-A in CLL B cells

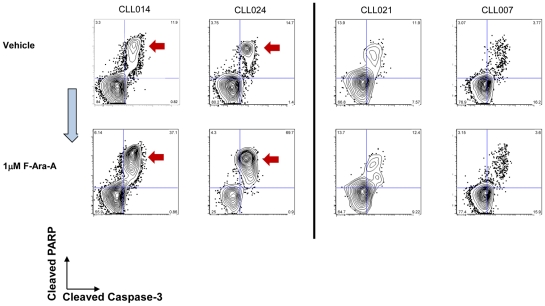

There has long been a presumed link between ligand-dependent and independent BCR signaling with B cell survival [17]–[20]. If such links are critical, then it might be further postulated that in CLL and other B cell malignancies, associations may exist between signaling potential downstream of the BCR and apoptotic competence. To test this, apoptotic responses of CLL samples and healthy donors were enumerated by SCNP after in vitro exposure to F-ara-A for 48 hours. Representative CLL samples responsive or refractory (Criteria described in Materials and Methods) to in vitro F-ara-A exposure show simultaneous measurement of cleaved caspase 3 and cleaved PARP in each cell (Figure 3 and Figure S4(B) (C)). Measurements of loss of mitochondrial cytochrome C in the same cells are consistent with these apoptotic responses (data not shown).

Figure 3. Effect on apoptosis of In vitro exposure of CLL B cells to F-ara-A.

Representative 2D flow plots (cleaved caspase 3 (X-axis) and cleaved PARP (Y-axis)) show that samples CLL014 and CLL024 undergo F-ara-A-mediated apoptosis (left-hand panels, (red arrows). By contrast samples CLL021 and CLL007 were relatively refractory to F-ara-A treatment (right-hand panels).

Within apoptotically responsive samples there were at least two cell subpopulations, with a second cell subset that was refractory to in vitro F-ara-A exposure (Figure 3 (Left hand panels). This is reminiscent of the signaling data described above in which cell subsets with heterogeneous signal transduction responses were seen within the same sample (Figure 2(A)). At 48 hours 5 leukemic samples (in the absence of F-ara-A) had high background values for cleaved PARP and cytochrome C and were therefore excluded from the analysis (Figure S3). DNA damage was assessed using an antibody against the phospho-threonine 68 epitope on Chk2, the ATM phosphorylation site [42]. Although differences in p-Chk2 levels were seen in cell subsets within F-ara-A responsive and refractory samples, these differences were not statistically significant (data not shown). Furthermore, staurosporine a global kinase inhibitor, and mechanistically distinct from F-ara-A, mediated apoptosis in all except 3 samples (Figure S5(A) and S5(B)).

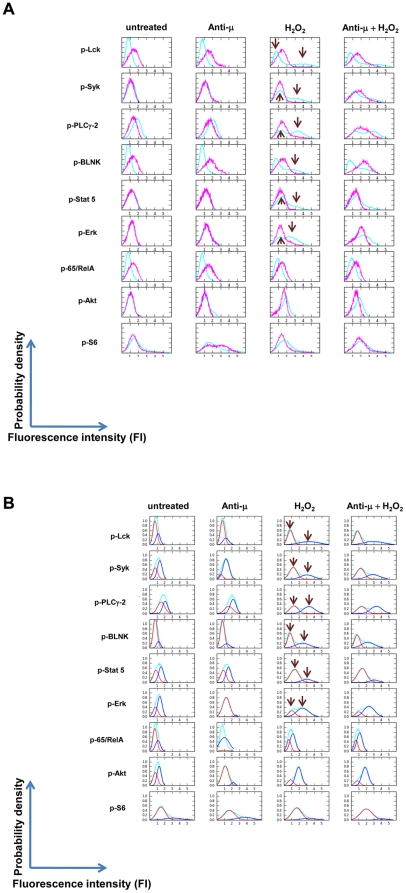

Given the pro-survival role BCR signaling molecules play in healthy and tumorigenic B cell biology [5], [12], [16], [43], the data were analyzed for any associations between H2O2-modulated signaling and apoptotic response to in vitro F-ara-A exposure. To evaluate the CLL cohort for trends, all cell events from gated B cells of all CLL samples and, separately, all healthy samples were combined into respective ‘virtual’ samples that represented a composite of the fluorescence intensities for each modulated signaling molecule. The histograms show a greater spread in the fluorescence intensities in CLL versus healthy B cells treated with H2O2 for each intracellular signaling molecule (Figure 4(A) CLL B cells (cyan) versus healthy B cells (pink)). Combining H2O2 with anti−µ did not produce additional substantial changes compared to H2O2 alone in the B cell population distribution of CLL B cells, suggesting that H2O2 was defining the signaling potential of these CLL B cell populations. This contrasted with healthy B cells in which the combination of H2O2 and anti−μ, but not H2O2 alone resulted in an enhanced population distribution based on signaling (Figure 4(A), fourth column [16]).

Figure 4. Population distributions of all CLL and all healthy B cells based on their fluorescence intensities.

(A) Arcsinh transformed fluorescence intensities either from all gated CLL and healthy B cells in all samples were used to derive the histograms. CLL samples (cyan) demonstrate multiple examples of bimodal activation (arrows), revealed after H2O2 treatment. By contrast healthy B cells (pink) demonstrate a single cell subset with minimal activation of signaling after H2O2 treatment. (B) Mixture models comprised of two normal distributions [60] were generated from the histograms of CLL B cells in (A) [61]. These metrics were termed ‘MixMod1’ and ‘MixMod2’ representing the areas under the curve for the distributions with lower (red) and higher (blue) fluorescence intensities, respectively.

Defining cell populations by mixture models in CLL B cells

On the assumption that at least two subpopulations of cells could be driving the distribution of expression in the combined samples, the underlying "subpopulations" were decomposed via mixture modeling for the CLL samples to represent the underlying probability distributions (Figure 4(B)). The trends in the mixture models emphasize the patterns (as expected) of the individual patient samples: the presence of an H2O2 de-repressed cell subpopulation and a cell subset non-responsive to H2O2. The mixture model has the benefit of showing, at least for this cohort of patients, the averaged boundaries of where such subpopulations of cells lay on the histograms. The relative numbers of cells in each population defined by these curves were used as metrics that may be linked to the presence or absence of these observed cell subsets to apoptosis response.

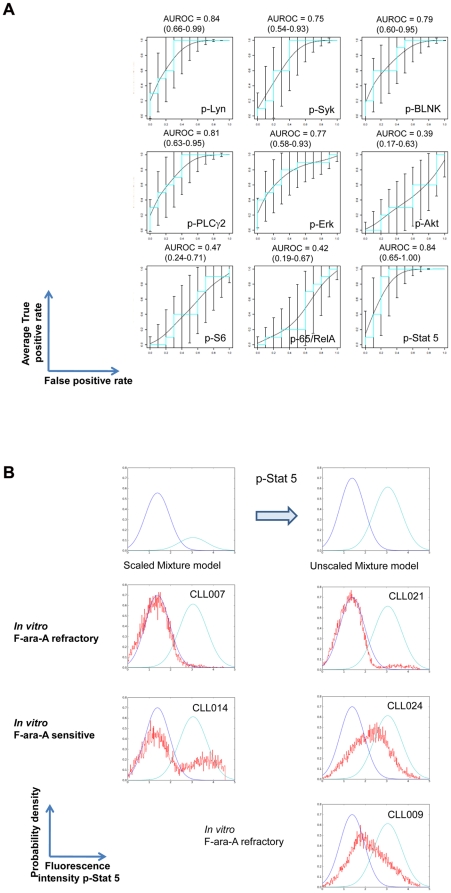

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves (Figure 5(A)) were generated to demonstrate whether presence of either or both of the populations defined by the mixture models (Figure 4(B)) was associated with apoptotic response to in vitro F-ara-A exposure. No such associations were observed for healthy B cells, as expected, since the H2O2 concentration was selected to give no response in healthy B cells as previously reported [16].

Figure 5. Statistical association between H2O2-mediated signaling and apoptotic induction by F-ara-A.

(A) AUROC curves were expressed with 95% confidence limits in order to evaluate how statistically significant H2O2–induced signaling is in predicting an in vitro apoptotic response to F-ara-A. The mixture model metric for H2O2-mediated signaling was used to calculate whether there was an association with response or lack of response to in vitro exposure to F-ara-A. A value of 0.5 for the ROC plots indicates that the association is due to chance. A value of 1.0 indicates that there is a perfect association. (B) Example of a Mixture Model showing the ability of H2O2-mediated increase in p-Stat5 to predict response to F-ara-A for an individual patient. An unscaled mixture model was derived from the mixture model for H2O2-mediated p-Stat5 signaling (top panel and Figure 4B, 5th row). Blue - population density distribution defined by MixMod1, cyan - population density distribution defined by MixMod2, red - population density distribution for H2O2-mediated p-Stat5 for B cells from an individual patient.

Area under the ROC curves (AUC of ROC curve) [44] for signaling induced by H2O2 treatment showed that p-Lyn (AUC 0.84), p-Syk (AUC 0.75), p-BLNK (AUC 0.79), p-PLCγ2 (AUC 0.81), p-Erk (AUC 0.77) and p-Stat5 (AUC 0.84) signaling stratified patient samples according to their apoptotic pathway response (Figure 5(A)). Using the metrics derived from the mixture models, the ROC curves showed that samples in which H2O2 exposure revealed signaling were more likely to undergo F-ara-A mediated apoptosis (Figure 4(B), 5(A)). By contrast, samples in which H2O2 failed to induce signaling were largely non-responsive to F-ara-A (Figures 2(A–C), Figure 3 and Table 3).

Of note, although the range of expression observed for SHP-1, SHP-2 and CD45 tyrosine phosphatases was greater in CLL compared to healthy B cells (Table S2) no association could be seen between their expression with induced signaling or apoptosis. Thus levels of these phosphatases alone were not surrogates for these pathway functions. No associations could be made between the IgVH mutational status or ZAP70 expression status and in vitro response to F-ara-A (Fisher’s exact test for association between IgVH status and apoptosis F-ara-A responder/F-ara-A refractory, p value = 1, odds ratio = 0.84).

The areas under the ROC curves demonstrated significant associations between H2O2-mediated signaling and apoptotic proficiency for the entire CLL sample cohort (Figure 5(A)). However, in order to predict response to in vitro F-ara-A treatment for an individual sample, an un-scaled mixture model of for example, H2O2-induced phosphorylation of Stat5 was established for all the CLL samples (Figure 5(B), top panels). Samples CLL007 and CLL021 have one population distribution of cells and are refractory to F-ara-A exposure. Samples CLL014 and CLL024 show population distributions of cells that span both subpopulations and CLL B cells and these samples are responsive to F-ara-A exposure. CLL009 has a signaling profile predictive of apoptotic sensitivity but was refractory to in vitro F-ara-A. This latter sample does not fit the model presumably due to alternative pathways that confer refractoriness to apoptosis (Figure 5(B)). By contrast CLL013 had a reduced H2O2-mediated signaling response but yet had a strong apoptotic response (Table 3, Figure S3 and data not shown) suggesting that in this sample a different biology may be driving CLL.

Discussion

Although, several molecular and cytogenetic lesions have emerged as potential prognostic indicators for CLL many disparities and confounding issues limit their clinical utility [33], [45], [46]. For example, although primary resistance to fludarabine has been shown to occur in patients harboring p53 deletions, a recent study reported that treatment-naïve patients with p53 deletions exhibit clinical heterogeneity with some patients experiencing an indolent course [47], [48]. These published clinical studies suggest that there are underlying differences in CLL biology, which if understood, could provide more reliable prognostic information for individual patients.

The data in this study have highlighted a link between H2O2-induced changes in phosphorylation of signaling proteins downstream of the BCR and in vitro F-ara-A-mediated apoptosis in CLL B cells. Specifically, the data showed: (1) The sample cohort could be divided into two groups based on the size of a cell subset within each sample that was responsive to the reactive oxygen species H2O2 based on increased phosphorylation of p-Lyn, p-Syk, p-BLNK, p-PLCγ2 and p-Stat5. (2) In most cases in which the H2O2 responsive subpopulation was greater than 30%, a cell subset proficient for F-ara-A mediated apoptosis was seen in the same sample. (3) A mixture modeling metric was derived that was linked to the presence or absence of these observed cell subsets to apoptosis response. (4) AUC values for this model were above 0.75 for p-Lyn, p-Syk, p-BLNK, p-PLCγ2 and p-Stat5 and stratified patient samples according to their apoptotic pathway response.

Although the CLL sample cohort was obtained from CLL patients receiving different treatments, it was striking that their H2O2 response was able to segregate the samples into two groups. The concentration of H2O2 used in study was in the millimolar range and was chosen based on its ability to mediate a response in leukemic B cells but not in healthy B cells as previously reported [5]. It is difficult to ascertain exact intracellular concentrations of H2O2 as its production tends to be localized either in the plasma membrane or in endosomes and inactivating antioxidant enzymes prevent indiscriminate oxidation of intracellular molecules by H2O2 [14], [49]. H2O2 is produced by NADPH Oxidase (Nox) enzymes that are activated by cell surface receptors including BCR [14], [15], [50]. To function as an intracellular signaling molecule, H2O2 must be imported into the cytosol and reported intracellular concentrations range from micromolar to millimolar levels [49], [51]. As an intracellular second messenger, H2O2, results in amplification of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling by transiently and reversibly inactivating tyrosine phosphatases (PTPS) through reversible oxidation of the catalytic cysteine to sulfenic acid [14], [49], [52]. A likely role for PTPs in both ligand-dependent and independent BCR signaling was revealed in several studies. In healthy B cells and follicular lymphoma H2O2 participates in anti-µ mediated signaling [5], [7], [15], [16]. Other reports showed that Syk was activated by pervanadate/H2O2 in the absence of BCR crosslinking [14], [21]–[23].

That activated BCR signaling molecules, in the absence of ligand, play an important survival role in CLL and other B cell malignancies is substantiated by recent studies. One study showed that in CLL B cells where Lyn protein is over-expressed, its inhibition by small molecule inhibitors in vitro in the absence of a BCR ligand, induced apoptosis [53]. Corroborating these findings, in vitro treatment of DLBCL and CLL cells with R406 a small molecule inhibitor of Syk (a substrate of Lyn) also induced apoptosis [25], [26], [54]. More recently, a phase I/II clinical trial of fostamatinib disodium, an oral Syk inhibitor showed clinical activity in CLL and non-Hodgkins lymphoma [27]. Another study showed a negative correlation between the expression of ZAP70 with the phosphorylation state of Syk and a positive correlation between p-Syk with p21cip, a cell cycle inhibitor [55]. Further insights into the relationship of phosphatase activity with BCR signaling molecules and apoptosis could be determined by experiments including specific tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors specifically targeting SHP-1 and/or CD45. A priori, such inhibitors would be predicted to promote CLL blast cell survival. Consistent with this hypothesis, ectopic expression of protein tyrosine phosphatase, PTPRO, (silenced in CLL by DNA methylation) increased growth inhibition in response to F-ara-A [34]. In DLBCL, PTPROt was identified as a tumor suppressor with a role in tonic BCR signaling [56]. Furthermore, additional studies will be required to determine whether lymphoid tyrosine phosphatase (Lyp) also known as PTPN22, whose expression was reported to be increased in CLL B cells, plays a role in the response of CLL B cells to therapeutic agents (Negro et al., Blood (ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts) 2009 114: Abstract 800).

Although not definitively proven, the data in this study potentially support a mechanism whereby H2O2 through inhibition of tyrosine phosphatases relieves a negative feedback loop that results in activation of signaling proteins within the BCR network. Regardless of its exact mechanism of action, H2O2 was able to reveal differential signaling within CLL samples and these signaling differences appear to be associated with a signaling posture that either drives, or is driven by the ability of these cells to undergo apoptotic induction by, in this case F-ara-A.

In this study, SCNP analysis, combined with mixture modeling identified at least two phenotypes of CLL B cells based on their H2O2 – mediated response of signaling molecules (Figure 2(A), (B), (C), Table 3). Notably, some samples demonstrated simultaneous presence of both cell subsets, suggesting co-evolution of signaling phenotypes, a common precursor of these cell subsets, or a lineage relationship between the two subpopulations of cells (Figure 2(A), (C)). Interestingly, and in contrast to studies where the presence of ZAP70 and unmutated IgVH correlated with greater anti−μ-mediated-BCR signaling [25], [29], the signaling responses described here were unrelated to the IgVH mutational status or to ZAP70 expression and spanned a range of cytogenetic abnormalities. Although further studies are warranted to investigate this issue, it is important to note that the above studies [25], [29] were accomplished via indirect assay of total phospho-tyrosine on signaling proteins. In our study, we undertook direct assay of phosphorylation sites using antibodies directed against known, functional, epitopes on a per cell basis. Additionally, no associations were observed between SHP-1, SHP-2, CD22 or CD45 expression levels with H2O2-mediated signaling (data not shown).

Although not a member of the canonical BCR signaling network, the increase seen in H2O2 –mediated p-Stat5 could be due to a bystander effect resulting from phosphatase inhibition with consequent increases in kinase activities for which Stat5 is a substrate. Interestingly, Sattler et al, showed the importance of H2O2 generation with consequent increases in p-Stat5 in several hematopoietic growth factor cascades in cell lines [40]. A pivotal role was also demonstrated for activated Stat5 in hematopoietic stem cell self- renewal and expansion of multi-potential progenitors in myeloid disease [57]. In addition, highly distinctive cytokine responses in Stat5 phosphorylation were reported in both normal and leukemic stem/progenitor cells [58]. Furthermore, in a recent study phospholipase C-β3 was shown to be a tumor suppressor by acting as a scaffold for simultaneous interaction with p-Stat5 and SHP-1 and by doing so promoted the dephosphorylation of p-Stat5 [59]. Whether these mechanisms regulate p-Stat5 in CLL awaits further study.

The clinical complexity (and unpredictability) of CLL as well as the many components governing cell proliferation and survival mechanisms, suggest a diversity of mechanisms that give rise to CLL. Nonetheless, the current studies, although mechanistically incomplete demonstrate a convergence of signaling patterns in CLL that lead to a remarkably limited set of phenotypic cell signaling outcomes. This suggests that despite the underlying molecular and clinical heterogeneity that maintains cellular homeostasis in CLL, only a limited number of signaling pathway variations exist and these may be exploited for therapeutic benefit. Although the sample set was limited, the encouraging AUC values (Figure 5(A)) endorse follow-up studies with expanded sample cohorts, both cryopreserved and fresh, to determine whether SCNP of individual samples can predict treatment outcome and stratify patients who might gain the most benefit from fludarabine-based treatment regimens.

Supporting Information

Gating scheme applied to B cells from CLL and healthy donors.

(TIF)

H2O2 amplifies BCR-mediated signaling in healthy B cells. PBMCs from healthy donors were either untreated or stimulated for 10 minutes with anti-µalone, H2O2 alone or the combination. 2D flow plots of gated B cells show exemplary samples in which H2O2 potentiates anti-µ mediated signaling of proximal BCR effectors as previously reported [16].

(TIF)

H2O2 treatment segregates CLL samples into two groups based on p-Stat 5 signaling in cell subsets. Changes in Stat 5 phosphorylation are shown in 2D flow plots and panels (A) and (B) show samples organized by their apoptotic response to in vitro F-ara-A exposure. (A) Stat 5 is phosphorylated in response to H2O2 alone in a CLL B cell subset within this CLL sample sub-group. All samples with these Stat 5 responsive cells undergo F-ara-A-induced apoptosis. (B) Minimal Stat 5 phosphorylation is seen in response to H2O2 alone within this CLL sample sub-group. All samples except for CLL009 fail to undergo H2O2–mediated Stat 5 phosphorylation. (C) Stat 5 is not phosphorylated in healthy B cells in response to H2O2.

(TIF)

Measurements of apoptosis after In vitro exposure of all samples from CLL and healthy donors to F-ara-A. (A) 2D flow plots show that healthy B cells undergo apoptosis in response to F-ara-A exposure. (B) 2D flow plots in which CLL B cells subsets undergo apoptosis after exposure to F-ara-A. (C) 2D flow plots in which CLL B cells subsets are refractory to F-ara-A exposure.

(TIF)

Measurements of apoptosis after in vitro exposure of CLL samples to staurosporine (5µM) for 6 hours. (A) 2D flow plots showing response of samples that were recorded as F-ara-A responders (Table 3 and Figure S4 (A). (B) 2D flow plots showing response of samples that were recorded as F-ara-A non-responders (Table 3 and Figure S4 (B)).

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. M. Irish for intellectual input, T.J. Kipps and L. Rassenti for providing clinical samples and R. Lin, D. Soper, and D.R. Parkinson for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have read the journal's policy and have the following conflicts: GPN is a consultant, Chairman of the SAB, and holder of equity in Nodality, Inc. WJF, ALP, EE, Y-WH and AC are holders of equity in Nodality, Inc. This does not alter the authors' adherence to all the PLoS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

Funding: This work was supported by research funding from Nodality, Inc. to WJF. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Dohner H, Stilgenbauer S, Benner A, Leupolt E, Krober A, et al. Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1910–1916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200012283432602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damle RN, Wasil T, Fais F, Ghiotto F, Valetto A, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. Cellular origin(s) of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: cautionary notes and additional considerations and possibilities. Blood. 2011;117:1781–1791. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-155663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Irish JM, Hovland R, Krutzik PO, Perez OD, Bruserud O, et al. Single cell profiling of potentiated phospho-protein networks in cancer cells. Cell. 2004;118:217–228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irish JM, Czerwinski DK, Nolan GP, Levy R. Altered B-cell receptor signaling kinetics distinguish human follicular lymphoma B cells from tumor-infiltrating nonmalignant B cells. Blood. 2006;108:3135–3142. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotecha N, Flores NJ, Irish JM, Simonds EF, Sakai DS, et al. Single-cell profiling identifies aberrant STAT5 activation in myeloid malignancies with specific clinical and biologic correlates. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:335–343. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irish JM, Myklebust JH, Alizadeh AA, Houot R, Sharman JP, et al. B-cell signaling networks reveal a negative prognostic human lymphoma cell subset that emerges during tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12747–12754. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002057107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kornblau SM, Minden MD, Rosen DB, Putta S, Cohen A, et al. Dynamic single-cell network profiles in acute myelogenous leukemia are associated with patient response to standard induction therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3721–3733. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosen DB, Minden MD, Kornblau SM, Cohen A, Gayko U, et al. Functional characterization of FLT3 receptor signaling deregulation in acute myeloid leukemia by single cell network profiling (SCNP). PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen DB, Putta S, Covey T, Huang YW, Nolan GP, et al. Distinct patterns of DNA damage response and apoptosis correlate with Jak/Stat and PI3kinase response profiles in human acute myelogenous leukemia. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e12405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irish JM, Kotecha N, Nolan GP. Mapping normal and cancer cell signalling networks: towards single-cell proteomics. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:146–155. doi: 10.1038/nrc1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brezski RJ, Monroe JG. Sigalov AB, editor. B-Cell Receptor. Multichain Immune Recognition Receptor Signaling: From Spatiotemporal Organization to Human Disease: Landes Bioscience. 2008. [PubMed]

- 13.Gauld SB, Dal Porto JM, Cambier JC. B cell antigen receptor signaling: roles in cell development and disease. Science. 2002;296:1641–1642. doi: 10.1126/science.1071546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reth M. Hydrogen peroxide as second messenger in lymphocyte activation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:1129–1134. doi: 10.1038/ni1202-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh DK, Kumar D, Siddiqui Z, Basu SK, Kumar V, et al. The strength of receptor signaling is centrally controlled through a cooperative loop between Ca2+and an oxidant signal. Cell. 2005;121:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Irish JM, Czerwinski DK, Nolan GP, Levy R. Kinetics of B cell receptor signaling in human B cell subsets mapped by phosphospecific flow cytometry. J Immunol. 2006;177:1581–1589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monroe JG. ITAM-mediated tonic signalling through pre-BCR and BCR complexes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:283–294. doi: 10.1038/nri1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fuentes-Panana EM, Bannish G, Karnell FG, Treml JF, Monroe JG. Analysis of the individual contributions of Igalpha (CD79a)- and Igbeta (CD79b)-mediated tonic signaling for bone marrow B cell development and peripheral B cell maturation. J Immunol. 2006;177:7913–7922. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraus M, Alimzhanov MB, Rajewsky N, Rajewsky K. Survival of resting mature B lymphocytes depends on BCR signaling via the Igalpha/beta heterodimer. Cell. 2004;117:787–800. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kraus M, Pao LI, Reichlin A, Hu Y, Canono B, et al. Interference with immunoglobulin (Ig)alpha immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) phosphorylation modulates or blocks B cell development, depending on the availability of an Igbeta cytoplasmic tail. J Exp Med. 2001;194:455–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wienands J, Larbolette O, Reth M. Evidence for a preformed transducer complex organized by the B cell antigen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:7865–7870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolli V, Gallwitz M, Wossning T, Flemming A, Schamel WW, et al. Amplification of B cell antigen receptor signaling by a Syk/ITAM positive feedback loop. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1057–1069. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00739-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith SH, Reth M. Perspectives on the nature of BCR-mediated survival signals. Mol Cell. 2004;14:696–697. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghia P, Chiorazzi N, Stamatopoulos K. Microenvironmental influences in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: the role of antigen stimulation. J Intern Med. 2008;264:549–562. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02030.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Huynh L, Apgar J, Tang L, Rassenti L, et al. ZAP-70 enhances IgM signaling independent of its kinase activity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;111:2685–2692. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gobessi S, Laurenti L, Longo PG, Carsetti L, Berno V, et al. Inhibition of constitutive and BCR-induced Syk activation downregulates Mcl-1 and induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Leukemia. 2009;23:686–697. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Friedberg JW, Sharman J, Sweetenham J, Johnston PB, Vose JM, et al. Inhibition of Syk with fostamatinib disodium has significant clinical activity in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:2578–2585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-236471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Davis RE, Ngo VN, Lenz G, Tolar P, Young RM, et al. Chronic active B-cell-receptor signalling in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature. 2010;463:88–92. doi: 10.1038/nature08638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gobessi S, Laurenti L, Longo PG, Sica S, Leone G, et al. ZAP-70 enhances B-cell-receptor signaling despite absent or inefficient tyrosine kinase activation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphoma B cells. Blood. 2007;109:2032–2039. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-011759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kolb JP, Kern C, Quiney C, Roman V, Billard C. Re-establishment of a normal apoptotic process as a therapeutic approach in B-CLL. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2003;3:261–286. doi: 10.2174/1568006033481384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rassenti LZ, Huynh L, Toy TL, Chen L, Keating MJ, et al. ZAP-70 compared with immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene mutation status as a predictor of disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:893–901. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;111:5446–5456. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Motiwala T, Majumder S, Kutay H, Smith DS, Neuberg DS, et al. Methylation and silencing of protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type O in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3174–3181. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gandhi V, Plunkett W. Cellular and clinical pharmacology of fludarabine. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:93–103. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200241020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krutzik PO, Nolan GP. Intracellular phospho-protein staining techniques for flow cytometry: monitoring single cell signaling events. Cytometry A. 2003;55:61–70. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hewamana S, Alghazal S, Lin TT, Clement M, Jenkins C, et al. The NF-kappaB subunit Rel A is associated with in vitro survival and clinical disease progression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and represents a promising therapeutic target. Blood. 2008;111:4681–4689. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-11-125278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hertlein E, Byrd JC. CLL and activated NF-kappaB: living partnership. Blood. 2008;111:4427. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghia P, Guida G, Stella S, Gottardi D, Geuna M, et al. The pattern of CD38 expression defines a distinct subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients at risk of disease progression. Blood. 2003;101:1262–1269. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sattler M, Winkler T, Verma S, Byrne CH, Shrikhande G, et al. Hematopoietic growth factors signal through the formation of reactive oxygen species. Blood. 1999;93:2928–2935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwon J, Lee SR, Yang KS, Ahn Y, Kim YJ, et al. Reversible oxidation and inactivation of the tumor suppressor PTEN in cells stimulated with peptide growth factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:16419–16424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407396101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antoni L, Sodha N, Collins I, Garrett MD. CHK2 kinase: cancer susceptibility and cancer therapy - two sides of the same coin? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:925–936. doi: 10.1038/nrc2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jumaa H, Hendriks RW, Reth M. B cell signaling and tumorigenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kay NE, O'Brien SM, Pettitt AR, Stilgenbauer S. The role of prognostic factors in assessing ‘high-risk’ subgroups of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2007;21:1885–1891. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hamblin TJ. Prognostic markers in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2007;20:455–468. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tam CS, Shanafelt TD, Wierda WG, Abruzzo LV, Van Dyke DL, et al. De novo deletion 17p13.1 chronic lymphocytic leukemia shows significant clinical heterogeneity: the M. D. Anderson and Mayo Clinic experience. Blood. 2009;114:957–964. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-210591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dohner H, Fischer K, Bentz M, Hansen K, Benner A, et al. p53 gene deletion predicts for poor survival and non-response to therapy with purine analogs in chronic B-cell leukemias. Blood. 1995;85:1580–1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rhee SG. Cell signaling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 2006;312:1882–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.1130481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rao GN. Protein tyrosine kinase activity is required for oxidant-induced extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase activation and c-fos and c-jun expression. Cell Signal. 1997;9:181–187. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(96)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sundaresan M, Yu ZX, Ferrans VJ, Irani K, Finkel T. Requirement for generation of H2O2 for platelet-derived growth factor signal transduction. Science. 1995;270:296–299. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5234.296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tonks NK. Redox redux: revisiting PTPs and the control of cell signaling. Cell. 2005;121:667–670. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Contri A, Brunati AM, Trentin L, Cabrelle A, Miorin M, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells contain anomalous Lyn tyrosine kinase, a putative contribution to defective apoptosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:369–378. doi: 10.1172/JCI22094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buchner M, Fuchs S, Prinz G, Pfeifer D, Bartholome K, et al. Spleen tyrosine kinase is overexpressed and represents a potential therapeutic target in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5424–5432. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaplan D, Meyerson HJ, Li X, Drasny C, Liu F, et al. Correlation between ZAP-70, phospho-ZAP-70, and phospho-Syk expression in leukemic cells from patients with CLL. Cytometry Part B, Clinical cytometry. 2010;78:115–122. doi: 10.1002/cyto.b.20506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen L, Juszczynski P, Takeyama K, Aguiar RC, Shipp MA. Protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor-type O truncated (PTPROt) regulates SYK phosphorylation, proximal B-cell-receptor signaling, and cellular proliferation. Blood. 2006;108:3428–3433. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kato Y, Iwama A, Tadokoro Y, Shimoda K, Minoguchi M, et al. Selective activation of STAT5 unveils its role in stem cell self-renewal in normal and leukemic hematopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2005;202:169–179. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Han L, Wierenga AT, Rozenveld-Geugien M, van de Lande K, Vellenga E, et al. Single-cell STAT5 signal transduction profiling in normal and leukemic stem and progenitor cell populations reveals highly distinct cytokine responses. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xiao W, Hong H, Kawakami Y, Kato Y, Wu D, et al. Tumor suppression by phospholipase C-beta3 via SHP-1-mediated dephosphorylation of Stat5. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:161–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Du J. McMaster University; 2002. Combined Algorithms for Fitting Finite Mixture Distributions. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Efroni S, Schaefer CF, Buetow KH. Identification of key processes underlying cancer phenotypes using biologic pathway analysis. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e425. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rassenti LZ, Jain S, Keating MJ, Wierda WG, Grever MR, et al. Relative value of ZAP-70, CD38, and immunoglobulin mutation status in predicting aggressive disease in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2008;112:1923–1930. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-092882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Gating scheme applied to B cells from CLL and healthy donors.

(TIF)

H2O2 amplifies BCR-mediated signaling in healthy B cells. PBMCs from healthy donors were either untreated or stimulated for 10 minutes with anti-µalone, H2O2 alone or the combination. 2D flow plots of gated B cells show exemplary samples in which H2O2 potentiates anti-µ mediated signaling of proximal BCR effectors as previously reported [16].

(TIF)

H2O2 treatment segregates CLL samples into two groups based on p-Stat 5 signaling in cell subsets. Changes in Stat 5 phosphorylation are shown in 2D flow plots and panels (A) and (B) show samples organized by their apoptotic response to in vitro F-ara-A exposure. (A) Stat 5 is phosphorylated in response to H2O2 alone in a CLL B cell subset within this CLL sample sub-group. All samples with these Stat 5 responsive cells undergo F-ara-A-induced apoptosis. (B) Minimal Stat 5 phosphorylation is seen in response to H2O2 alone within this CLL sample sub-group. All samples except for CLL009 fail to undergo H2O2–mediated Stat 5 phosphorylation. (C) Stat 5 is not phosphorylated in healthy B cells in response to H2O2.

(TIF)

Measurements of apoptosis after In vitro exposure of all samples from CLL and healthy donors to F-ara-A. (A) 2D flow plots show that healthy B cells undergo apoptosis in response to F-ara-A exposure. (B) 2D flow plots in which CLL B cells subsets undergo apoptosis after exposure to F-ara-A. (C) 2D flow plots in which CLL B cells subsets are refractory to F-ara-A exposure.

(TIF)

Measurements of apoptosis after in vitro exposure of CLL samples to staurosporine (5µM) for 6 hours. (A) 2D flow plots showing response of samples that were recorded as F-ara-A responders (Table 3 and Figure S4 (A). (B) 2D flow plots showing response of samples that were recorded as F-ara-A non-responders (Table 3 and Figure S4 (B)).

(TIF)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)