Abstract

Background

Myelomatous pleural effusion (MPE) is rare in myeloma patients. We present a consecutive series of patients with MPE in a single institution.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of 19 patients diagnosed with MPE between 1989 and 2008 at the Asan Medical Center. Diagnoses were confirmed by cytologic identification of malignant plasma cells in the pleural fluid.

Results

Our patients showed dominance of IgA (36.8%) and IgD (31.6%) subtypes. Of 734 myeloma patients, the incidence of MPE was remarkably high for the IgD myeloma subtype (16.7%), compared to the other subtypes (1.4% for IgG and 4.6% for IgA). At the time of diagnosis of MPE, elevated serum β2-microglobulin, anemia, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase, and elevated creatinine levels were found in 100%, 89.5%, 83.3%, and 57.9% of the patients, respectively. Approximately one-third (31.3%) of the patients had adenosine deaminase (ADA) activities in their pleural fluid exceeding the upper limit of the reported cutoff values for tuberculous pleural effusion (55.8 U/L). Chromosome 13 abnormality was seen in 77.8% of the tested patients. The median survival period from the development of MPE was 2.8 months.

Conclusions

Patients with MPE have aggressive clinical and laboratory characteristics. The preponderance of IgD myeloma in MPE patients is a noteworthy finding because IgD myeloma is a rare subtype. Elevated ADA activity in the pleural fluid is also noteworthy, and may be helpful for detecting MPE. Physicians treating myeloma patients should monitor the development of MPE and consider the possibility of a worse clinical course.

Keywords: Myelomatous pleural effusion, IgD myeloma, Adenosine deaminase, Chromosome 13 abnormality

INTRODUCTION

Pleural effusion is a relatively uncommon finding in myeloma patients, with a frequency of only 6%, and is usually associated with benign conditions such as nephrotic syndrome, pulmonary embolism, congestive heart failure secondary to amyloidosis, and infection [1, 2]. Myelomatous pleural effusion (MPE) is rare, occurring in less than 1% of cases [1]. To date, the majority of studies in the literature have reported experiences with a single case of MPE and provide a brief literature review [3-5]. To the best of our knowledge, there has been only one case series of MPE in the English language literature [6]. In this report, the authors concluded that MPE in patients with myeloma is often associated with high-risk disease, including deletion 13 chromosomal abnormality and indicated a poor prognosis despite aggressive local and systemic treatment. Here, we report a further case series of 19 patients who were diagnosed with MPE at a single institution in Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We retrospectively collected data on patients who were diagnosed with multiple myeloma with pleural effusion from October 1989 to December 2008 at the Asan Medical Center. We reviewed medical records for 734 patients with multiple myeloma, and found that 54 of these cases were diagnosed with pleural effusion. Of these 54 eligible cases, 12 were excluded because of insufficient medical records or lack of pleural fluid analysis data. Among the remaining 42 patients, 19 were diagnosed with MPE and 23 had benign pleural effusion.

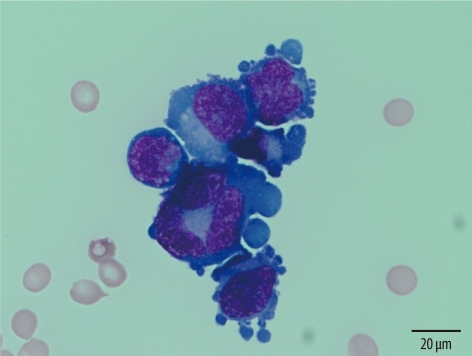

Diagnosis of multiple myeloma was based on the criteria of the International Myeloma Working Group [7]. The MPE diagnosis was established by cytologic identification of malignant plasma cells in the pleural fluid (Fig. 1). The data collected from the patients' medical records included the characteristics of pleural effusion, paraprotein isotype, and various laboratory parameters at the onset of pleural effusion. Early-onset effusion was defined as effusion occurring at the time of the initial diagnosis of myeloma or during the first cycle of chemotherapy. Clinical staging for myeloma patients was performed according to the International Staging System (ISS), which is the most widely used method for assessing the prognosis of myeloma [8]. A study on Japanese patients with IgD myeloma proposed a new staging system based on the light chain subtype and white blood cell (WBC) count [9]. They designated patients with a WBC count of 7.0×109 cells/L or more and a λ subtype as the high-risk group, while patients with a WBC count less than 7.0×109 cells/L and a κ subtype were classified into the low-risk group. Those with an intermediate status were classified into the middle-risk group. In our study, patients with IgD myeloma were separately staged using this new staging system. Laboratory parameters were reviewed, including serum calcium, serum creatinine, hemoglobin, serum M-protein, serum β2-microglobulin, serum lactate dehydrogenase (LD), serum C-reactive protein (CRP), and adenosine deaminase (ADA) activity in the pleural fluid. Chromosome analysis was conducted using bone marrow samples at the time of diagnosis. Survival was calculated from the onset of MPE to death. Continuous data are presented as medians (ranges) according to their non-parametric distribution. The institutional review board of Asan Medical Center approved this study.

Fig. 1.

Malignant plasma cells in the pleural effusion (case M). The cells have large, eccentrically placed and pleomorphic nuclei and prominent nucleoli (Wright-Giemsa stain, ×1,000).

RESULTS

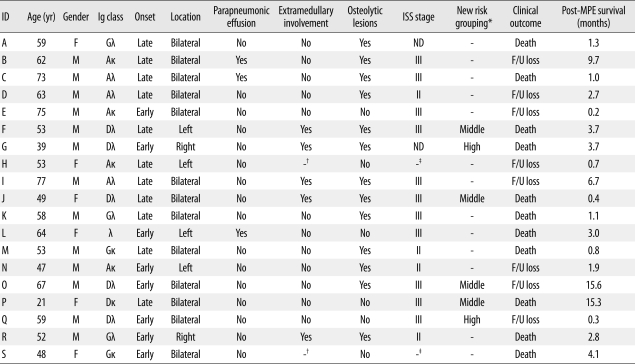

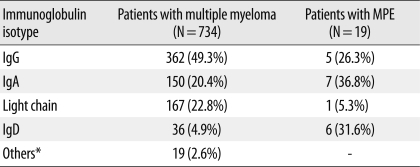

Among the 734 patients with multiple myeloma seen at our institution from October 1989 through December 2008, 19 (2.6%) had MPE. The clinical characteristics and outcomes of MPE in these patients are described in Table 1. Of the 19 patients with MPE, 13 were men and 6 were women. The median age of these patients was 58 yr (range: 21-77 yr). Two cases of extraosseous plasmacytoma were diagnosed, one in the paranasal sinus and one in the mediastinum, without evidence of plasmacytosis in the bone marrow. The most common myeloma isotype was IgA (36.8%, 7/19), followed by IgD (31.6%, 6/19), IgG (26.3%, 5/19), and light chain (5.3%, 1/19). Considering that the overall frequency of IgD myeloma was 4.9% in our institution, the frequency of this subtype in the MPE patients (31.6%) was unexpectedly high (Table 2). Furthermore, there was an exceptionally high incidence of MPE in patients with IgD myeloma (16.7%, 6/36) compared to those with IgG (1.4%, 5/362), IgA (4.7%, 7/150), or the light chain subtype (0.6%, 1/167) (Table 2). The frequencies of early-onset effusion, bilateral location, and parapneumonic effusion were 42.1%, 68.4%, and 15.8%, respectively. Osteolytic bone lesions and extramedullary involvement other than in the pleural space were observed in 68.4% and 29.4% of patients, respectively. At diagnosis, 73.3% (11/15) of patients belonged to ISS stage III. According to the new staging system for IgD myeloma [9], the majority of our IgD myeloma patients (66.7%, 4/6) were classified into the middle-risk group, while 33.3% (2/6) were classified into the high-risk group. None were classified into the low-risk group. Overall, the prognosis was poor, with an overall mortality of 57.9%. The median survival time from the development of pleural effusion was 2.8 months (range: 0.2-15.6 months) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 19 patients with MPE

*Grouping of IgD myeloma was based on reference 9; †Two patients with extraosseous plasmacytoma were excluded from the analysis; ‡Two patients with extraosseous plasmacytoma were excluded from estimation of clinical stage.

Abbreviations: ID, identification; ISS, International Staging System; MPE, myelomatous pleural effusion; F, female; M, male; ND, not described; F/U, follow up.

Table 2.

Comparison of the frequency of immunoglobulin isotypes between myeloma patients and MPE patients in our institution

*Others included biclonal gammopathy, IgM subtype, or non-secretory type.

Abbreviation: MPE, myelomatous pleural effusion.

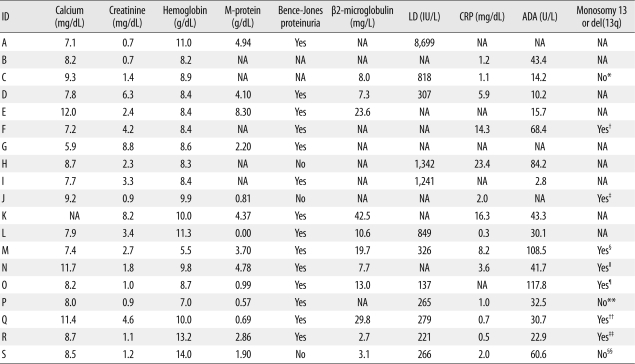

Laboratory evidence of advanced disease, such as elevated serum β2-microglobulin (>2.0 mg/L), anemia (hemoglobin <13 g/dL in males or <12 g/dL in females), elevated serum LD (>250 IU/L), elevated serum creatinine (>1.7 mg/dL), elevated serum CRP (>2.0 mg/L), and hypercalcemia (>10.5 mg/L), was seen in 100% (11/11), 89.5% (17/19), 83.3% (10/12), 57.9% (11/19), 42.9% (6/14), and 16.7% (3/18) of patients, respectively. The median level of serum M-protein was 2.53 g/dL (range: 0.0-8.30 g/dL), and the median ADA activity in the pleural fluid was 37.1 U/L (range: 2.8-117.8 U/L). The cutoff value of ADA activity to exclude tuberculous pleural effusion has been reported to range from 38 to 55.8 U/L [10-12]. In our study, approximately one-third of MPE patients (31.3%, 5/16) had ADA activities exceeding the upper limit of the reported cutoff values (55.8 U/L). However, we could not find any evidence of active pulmonary tuberculosis in the medical records of our patients. Bence-Jones proteinuria was present in 82.4% (14/17) of patients. Bone marrow cytogenetic analysis was conducted for 10 patients, including one (case S) who had extraosseous plasmacytoma and a normal karyotype in the marrow sample. The frequency of chromosome 13 abnormality (monosomy 13 or deletion of 13q) was 77.8% (7/9) of tested patients, excluding case S. These laboratory findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Laboratory characteristics of 19 patients with MPE

*Despite that bone marrow cytogenetics was conducted, a full description of the karyotype was not found in the medical record of this patient. However, we identified the summarized description, which was "hypertriploidy and very complex abnormality involving chromosomes 1, 3, 17, and 21"; †Karyotype was 44,XY,+1,der(1;16)(q10;p10),del(5)(p13),del (5)(q13),-10,-11,-13,-14,-17,der(19)t(17;19)(q21;p13.3),+der(?)t(11;?),+mar[5]/46,XY[2]; ‡Karyotype was 42,X,-X,+der(1;16)(q10;p10),dic(1;6)(p11;p25),-5,-6,-10,-13,der(14)t(6;14)(p21;q32)[6]/42,idem,del(3)(p21),del(4)(q33)[7]/47,X,X,+1,der(1;16)(q10;p10),dic (1;6)(p11;p25),t(6;14)(p21;q32),13,+der(14)t(6;14),+15,+21[4]/47,X,X,+1,der(1;16)(q10;p10),dic(1;6)(p11;p25),del(5)(q31),t(6;14)(p21;q32),-13,+der(14)t(6;14),+15,add(18) (q21),+21[3]; §Karyotype was 45,XY,+add(1)(p13),-2,del(6)(q15),-13[1]/46,XY[20]; ∥Karyotype was 72,XX,-Y,-1,+7,+12,-13,+14,+15,-17,-17,der(19)t(1;19)(q11;p13.3),-20,-20,-22,-22,+der(?)t(1;?)(q21;?),+7mar[19]/46,XY[1]; ¶Karyotype was 46,XY,add(7)(q11.2),del(13)(q12q14),add(14)(q32),del(14)(q24)[13]/46,XY[3]; **Karyotype was 46,XX[30]; ††Karyotype was 46,XY,add(1)(q21),+7,-13,del(14)(q32),+21,-22[4]/46,idem,add (16)(q22)[20]/46,XY[1]; ‡‡Karyotype was 47,XY,der(1)t(1;1)(p36.3;q11),der(1)t(1;14)(q44;q11),add(3)(q27),+7,+12,-13,-15,+21[3]/46,XY[27]; §§This patient had extraosseous plasmacytoma. Bone marrow cytogenetics revealed a normal female karyotype (46,XX[20]).

Abbreviations: MPE, myelomatous pleural effusion; ID, identification; LD, serum lactate dehydrogenase level; CRP, serum C-reactive protein; ADA, adenosine deaminase activity in pleural fluid; NA, not available.

DISCUSSION

The most noteworthy finding in this case series was the high frequency of IgD myeloma among MPE patients. Generally, the most common isotype in myeloma is IgG (50%), followed by IgA (20%), light chain (20%), and IgD, IgE, IgM, and biclonal (<10%) [13]. The distribution of immunoglobulin isotypes in our myeloma patients was consistent with this general description (Table 2). Despite this, we found that the frequencies of IgA and IgD subtypes in our MPE patients were quite high (36.8% and 31.6%, respectively). This predominance of IgA is consistent with previously reported findings of 3 separate studies, which found IgA myeloma in 80%, 27.6%, and 36.4% of MPE patients [3, 4, 6]. In contrast, the high frequency of IgD myeloma in our MPE patients was exceptional because IgD myeloma has accounted for only 0.7-5.7% of myeloma cases in prior studies [14], and the frequency of IgD myeloma in our institution was 4.9%. IgD myeloma is different from IgG and IgA myeloma, and one of the distinct characteristics of IgD myeloma is a frequent occurrence of extraosseous spread [14, 15]. Reflecting this characteristic, there have been 7 case reports of IgD myeloma with MPE in the English literature [16-22]. According to these reports, the predominance of IgD myeloma in MPE is thought to result from a tendency for extraosseous spread of IgD myeloma.

Another noteworthy finding was the presence of high ADA activity in the pleural fluid of some of the MPE patients. High ADA activity in pleural fluid strongly favors tuberculous pleural effusion. Even though we did not find any evidence of active pulmonary tuberculosis in our patients, approximately one-third of patients showed ADA activities exceeding the upper limit of the reported cutoff value for tuberculous pleural effusion. ADA is present in virtually all human tissues, but the highest levels are found in lymphoid tissues, such as the lymph nodes, spleen, and thymus [23]. In previous studies investigating the levels of ADA in hematologic malignancies, abnormal activities were found in some myeloma cases [24, 25]. High ADA levels in the pleural fluid have been previously reported in 2 patients with MPE: 61 U/L in a patient with IgA myeloma, and 50.2 U/L in a patient with IgD myeloma [3, 21]. Thus, we could assume that a small fraction of myeloma cells express ADA on their surfaces, and this may partly explain the high ADA levels in some MPE patients. However, considering that ADA plays a central role in the differentiation and maturation of the lymphoid system, elevated ADA in MPE patients might indicate changes in immunological activity following antigenic challenges, regardless of the ADA expression on myeloma cells.

The reported median survival time after the development of MPE is less than 4 months [4-6], consistent with the median survival time of our patients. The reason that MPE patients showed short survival times is clear. At diagnosis, the majority of patients were classified into advanced clinical stages using either the ISS system or the new risk grouping in the case of IgD subtype. At the time of development of MPE, the laboratory characteristics of many patients indicated an aggressive clinical course. In addition, MPE represents clinical progression of the disease in itself. In terms of prognosis, it was interesting that chromosome 13 abnormality was found with high frequency in our MPE patients, despite the relatively small number of patients tested. Chromosome 13 abnormality has been observed in 14-19% of myeloma patients using conventional cytogenetics [26, 27]. While fluorescence in situ hybridization is 2- to 3-fold more sensitive than metaphase cytogenetics for detecting such abnormalities, the karyotypes of our case series were based on conventional cytogenetic techniques. Therefore, the frequency of chromosome 13 abnormalities observed in our MPE patients (77.8%) was exceptionally high. However, this is very similar to the incidence (81.8%, 9/11) in MPE patients reported in a previous case series [6]. Since chromosome 13 abnormality has been associated with adverse clinical outcomes in myeloma patients [6, 26, 27], this may explain, at least in part, the association between MPE and a poor prognosis.

This study has two limitations. First, the study population was small. Although we described a few distinctive features of MPE patients, we cannot completely exclude possible bias caused by the small number of patients. Second, the diagnoses of MPE were made by cytological examination. Other ways of confirming the myelomatous etiology are the demonstration of monoclonal protein on pleural fluid electrophoresis, and histologic confirmation using a pleural biopsy specimen. Since hemorrhagic effusions are common, protein electrophoresis of the pleural fluid is an unreliable method for documenting myelomatous pleural involvement [6]. Pleural biopsy also has a low diagnostic yield for plasma cell infiltrates. Because of the patchy involvement of the pleura by the tumor, it may be difficult to diagnose myelomatous infiltration using a blind, closed pleural biopsy [4]. For these reasons, the best means of diagnosis is probably cytologic identification of malignant plasma cells within the pleural fluid [4]. However, it is possible that a microscopist could fail to identify the malignant plasma cells, particularly if they are few in number or in vitro degeneration has occurred. Despite these limitations, this case series describing a population of MPE patients, rather than a single case report or a review of the reported cases in the literature, represents a significant contribution, since it is only the second study of its kind.

In conclusion, our study found that MPE is highly associated with a predominance of IgA and IgD subtypes, and with aggressive clinical and laboratory characteristics. In particular, the preponderance of IgD myeloma in our MPE patients was an unexpected finding. Although the incidence of MPE was exceptionally high in IgD myeloma patients compared to the other subtypes, further studies are needed to determine whether IgD myeloma is strongly associated with the development of MPE. Elevated ADA activity in the pleural fluid can be useful for screening MPE. The high incidence of chromosome 13 abnormality in MPE patients is also significant, since the detection of these abnormalities is a critical prognostic factor for myeloma. Physicians who treat myeloma patients should monitor closely for the development of MPE and consider the possibility that their clinical course will deteriorate.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Kintzer JS, Rosenow EC, Kyle RA. Thoracic and pulmonary abnormalities in multiple myeloma. A review of 958 cases. Arch Intern Med. 1978;138:727–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alexandrakis MG, Passam FH, Kyriakou DS, Bouros D. Pleural effusions in hematologic malignancies. Chest. 2004;125:1546–1555. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez JN, Pereira A, Martinez JC, Conde J, Pujol E. Pleural effusion in multiple myeloma. Chest. 1994;105:622–624. doi: 10.1378/chest.105.2.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meoli A, Willsie S, Fiorella R. Myelomatous pleural effusion. South Med J. 1997;90:65–68. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199701000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim YJ, Kim SJ, Min K, Kim HY, Kim HJ, Lee YK, et al. Multiple myeloma with myelomatous pleural effusion: a case report and review of literature. Acta Haematol. 2008;120:108–111. doi: 10.1159/000165694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamble R, Wilson CS, Fassas A, Desikan R, Siegel DS, Tricot G, et al. Malignant pleural effusion of multiple myeloma: prognostic factors and outcome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1137–1142. doi: 10.1080/10428190500102845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International Myeloma Working Group. Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Munshi NC, Longo DL, Anderson KC. Plasma cell disorders. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al., editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 17th ed. New York, USA: McGraw Hill Medical; 2008. pp. 700–707. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimamoto Y, Anami Y, Yamaguchi M. A new risk grouping for IgD myeloma based on analysis of 165 Japanese patients. Eur J Haematol. 1991;47:262–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1991.tb01569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen ML, Yu WC, Lam CW, Au KM, Kong FY, Wo Cham AY. Diagnostic value of pleural fluid adenosine deaminase activity in tuberculous pleurisy. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;341:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaric B, Kuruc V, Milovancev A, Markovic M, Sarcev T, Canak V, et al. Differential diagnosis of tuberculosis and malignant pleural effusions: what is the role of adenosine deaminase? Lung. 2008;186:233–240. doi: 10.1007/s00408-008-9085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porcel JM, Aleman C, Bielsa S, Sarrapio J, Fernandez de Sevilla T, Esquerda A. A decision tree for differentiating tuberculous from malignant pleural effusions. Respir Med. 2008;102:1159–1164. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna RW, Kyle RA, Kuehl WM, Grogan TM, Harris NL, Coupland RW. Plasma cell neoplasms. In: Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al., editors. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008. pp. 200–213. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jancelewicz Z, Takatsuki K, Sugai S, Pruzanski W. IgD multiple myeloma. Review of 133 cases. Arch Intern Med. 1975;135:87–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blade J, Lust JA, Kyle RA. Immunoglobulin D multiple myeloma: presenting features, response to therapy, and survival in a series of 53 cases. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2398–2404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.11.2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pruzanski W, Rother I. IgD plasma cell neoplasia: clinical manifestations and characteristic features. Can Med Assoc J. 1970;102:1061–1065. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnston JB, Weinerman B, Cooney T, Bowman DM, Pettigrew NM, Orr K. IgD kappa plasma cell dyscrasias: extraosseous manifestations including isolated leptomeningitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1982;77:60–65. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/77.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamal MK, Williams E, Poskitt TR. IgD myeloma with malignant pleural effusion. South Med J. 1987;80:657–658. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198705000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim YM, Lee KK, Oh HS, Park SK, Won JH, Hong DS, et al. Myelomatous effusion with poor response to chemotherapy. J Korean Med Sci. 2000;15:243–246. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2000.15.2.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Natori K, Izumi H, Nagase D, Fujimoto Y, Ishihara S, Kato M, et al. IgD myeloma indicated by plasma cells in the peripheral blood and massive pleural effusion. Ann Hematol. 2008;87:587–589. doi: 10.1007/s00277-008-0444-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yokoyama T, Tanaka A, Kato S, Aizawa H. Multiple myeloma presenting initially with pleural effusion and a unique paraspinal tumor in the thorax. Intern Med. 2008;47:1917–1920. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang H, Chou WC, Lee SY, Huang JY, Hung YH. Myelomatous pleural effusion in a patient with plasmablastic myeloma: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:205–207. doi: 10.1002/dc.21004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cristalli G, Costanzi S, Lambertucci C, Lupidi G, Vittori S, Volpini R, et al. Adenosine deaminase: functional implications and different classes of inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2001;21:105–128. doi: 10.1002/1098-1128(200103)21:2<105::aid-med1002>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meier J, Coleman MS, Hutton JJ. Adenosine deaminase activity in peripheral blood cells of patients with haematological malignancies. Br J Cancer. 1976;33:312–319. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1976.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohata M, Masuda I, Nonaka K, Sugiura K. Combination assay of IAP and ADA in hematologic malignancies. Rinsho Byori. 1990;38:703–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaughnessy J, Jr, Tian E, Sawyer J, McCoy J, Tricot G, Jacobson J, et al. Prognostic impact of cytogenetic and interphase fluorescence in situ hybridization-defined chromosome 13 deletion in multiple myeloma: early results of total therapy II. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:44–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.03948.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiecchio L, Protheroe RKM, Ibrahim AH, Cheung KL, Rudduck C, Dagrada GP, et al. Deletion of chromosome 13 detected by conventional cytogenetics is a critical prognostic factor in myeloma. Leukemia. 2006;20:1610–1617. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]