Abstract

Medical implant-mediated inflammatory responses, often involving high levels of macrophages, are typically determined by histological analyses. These methods however are time consuming and require many animals to monitor the kinetics of inflammatory reactions and to generate reproducible outcomes. Recent studies have shown that activated macrophages in inflamed tissue express high levels of folate receptor (FR). In this study, FR-targeting NIR nanoprobes were fabricated and then tested for their ability to detect and quantify the extent of biomaterial-mediated inflammatory responses in vivo. Indeed, FR-targeting nanoprobes preferentially accumulate on activated macrophage surfaces. When administered intravenously, we found that the FR-targeting nanoprobes distinctively gathered in the inflamed tissues and that a different extent of FR-targeting nanoprobe gathering could be found in tissues implanted with different types of biomaterials. Most importantly, we found that there was a good relationship between the extent of inflammatory reactions and the intensity of nanoprobe-associated NIR signal in tissue. Our results support that FR-targeting NIR nanoprobes can be used to monitor and quantify the extent of macrophage recruitment and the degree of an implants' biocompatibility in real time.

1. Introduction

Implantable medical devices are increasingly important in the practice of modern medicine. Prospect shifts in population demographics towards older age groups, coupled with continued medical progresses, will lead to increased utilization of medical devices in the years ahead. Unfortunately, shortly after implantation, most implants accumulate substantial numbers of phagocytes as a result of biomaterial-mediated inflammatory reactions. The interactions between phagocytes and biomaterials have been associated with chronic inflammation and fibrotic reactions surrounding many types of implants [1]. For example, severe inflammatory responses might cause the degradation and failure of many implantable devices and the dissolution of surrounding tissues [2,3]. Therefore, substantial research has been placed on the development of biomaterials with improved blood and tissue biocompatibility.

To assist the search for better biomaterials, many in vitro and in vivo models have been developed to test a material's biocompatibility. For example, several in vitro systems, including phagocyte/platelet adhesion, activation, and blood compatibility, have been used to assess the blood and cell compatibility of the biomaterials [4-8]. Although these in vitro models provide good indication and evaluation of a material's biocompatibility, in vivo animal testing is often necessary to provide critical evaluations of biomaterials' cell and tissue compatibility [9]. However, there are many limitations associated with in vivo testing. First, since immune responses are dynamic reactions, the evaluation of tissue and cell responses at different time points are needed to depict the overall reactions. Second, many animals are needed at each time point to overcome the large variations of cell/tissue responses between individual animals. Finally, histological and chemical evaluations of the implant-associated tissues are often required to analyze the tissue responses to biomaterial implants. Despite the assistance of automatic tissue sectioning and staining processes, histological analyses remain to be time-consuming and tedious. In addition, sequential histology analyses on the same tissue are often needed to establish quantitative results for the whole tissue [10]. Consequently, these technical challenges significantly delay the development of medical implants with improved tissue and cell compatibility. Therefore, there is a need for the development of a fast, accurate, and simple method to assess the extent of foreign body reactions in vivo.

Recent development of in vivo imaging systems has attracted great interest in different research disciplines. Several noninvasive imaging techniques, including computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, positron emission tomography and ultraonography [11-14], have been developed to visualize and quantify the inflammatory responses in vivo. These techniques rely solely on structural changes and, therefore, are not able to identify non-traumatic, acute and localized inflammatory reactions. Several fluorescence-labeled cells and particle-based sensors have been developed for a wide range of applications in biological research and clinical diagnosis [15-22]. Of late, NIR fluorescence has been widely used for in vivo imaging because of reduced absorption and scattering of photons by tissues, and also reduced interference from auto-fluorescence signals [23].

It is well established that biomaterial implants are surrounded by large numbers of monocytes/macrophages (MΦs) and the activities of recruited/activated MΦs play an important role on pathogenesis of foreign body reactions [1,3]. It is therefore generally believed that the quantification of recruited MΦs would serve as a good assessment for the extent of inflammatory responses to biomaterial implants. Lately, FITC-conjugated MΦ-antibody F4/80 was used to image macrophage recruitment at biomaterial implant sites [24]. Although the results are very interesting, the FITC-F4/80 probe can only provide qualitative, not quantitative, assessment of foreign body reactions for the following reasons. First, the FITC-F4/80 produces an emission wavelength close to the autofluorescence emitted by skin with limited in vivo sensitivities. Second, although MΦ-antibody F4/80 has good cell specificity, the high cost of the antibody limits its use as an imaging probe for systemic administration. Interestingly, several recent studies found that activated MΦs over-express folate receptor (FR), which has a high affinity to FR-targeting probes in vitro [25-28]. Although FR-targeting probes have been tested for their ability to detect inflammatory arthritis [29-33], the ability of FR-targeting probes to quantify the degree of inflammatory responses was not determined. Furthermore, it has not previously been investigated whether or not FR-targeting probes may be employed in real-time to quantify the degree of biomaterial-mediated inflammatory responses and also to assess the extent of implant biocompatibility in vivo.

To find the answer, the following study was aimed at fabricating FR-targeting nanoprobes and testing their use in identifying and quantifying the degree of biomaterial-mediated inflammatory responses in vivo. Specifically, NIR dye-trapped Poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide-co-styrene) nanoparticles were synthesized and then conjugated with folate. The efficacy of FR-targeting nanoprobes in recognizing activated MΦs was studied in vitro. Using an in vivo imaging system, the effectiveness of FR-targeting nanoprobes in determining MΦ recruitment to the biomaterial implantation site was assessed. Finally, by comparing nanoprobe fluorescence intensities and histological evaluations, we explored the possibility of using FR-targeting nanoprobes to continuously monitor and quantity the extent of inflammatory responses to different biomaterial implants in vivo. This enhanced ability of FR-targeting nanoprobes may lead to future in vivo determination of a materials biocompatibility.

2. Materials and methods

Materials

N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM), styrene (St), divinylbenzene (DVB), Dodecyl Trimethyl Ammonium Bromide (DTAB), 2,2′-Azobis(2-methylpropionamidine)dihydrochloride (V50), l,l′,3,3,3′,3′-Hexamethylindotricarbocyanine (IR750), folate/folic acid, tetrahydrofuran (THF) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. N-(3-aminopropyl) methacrylamide (APMA) was procured from Polysciences (Warrington, PA). 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC) was obtained from Thermo scientific (Rockford, IL). Goat anti-mouse folate/folic acid receptor polyclonal antibody (sc-16387) and a rat anti-mouse MAC-1 (sc-23937) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat and goat anti-rat secondary antibodies were bought from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA).

Methods

Preparation and characterization of folate receptor(FR)-targeting nanoprobes

PNIPAM-co-St nanoparticles were synthesized by emulsion polymerization as described previously [34,35] with the supplement of 5 mole% APMA to create -NH2 bearing nanoparticles. The average diameter and size distribution of PNIPAM-co-St nanoparticle were determined using Photon Correlation Spectroscopy (ZetaPALS, Brookhaven Instruments Co., Holtsville, NY, USA). The morphology of the nanoparticles was also characterized using a JEM-1200EX transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Japan) as described earlier [36]. The trapping of IR750 dye into PNIPAM-co-St nanoparticles was then carried out according to published procedures [37]. The loading efficiency of IR750 dye was estimated according to the following equation: Loading efficiency= (Mloaded-IR750/MNP) × 100%. where Mloaded-IR750 is mass of the entrapped dye obtained by the calibration curve of IR750 and MNP is mass of the nanoparticles. Absorbance and fluorescence spectra of free and loaded IR750 were determined by UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Lambda 19 Spectrometer, PerkinElmer, MA) and fluorescence spectrometer (Shimadzu RF-5301PC, Japan), respectively. The photo stability of loaded IR750 vs free IR750 was evaluated by measuring the change in emission intensity before and after continuous exposure for 3.5 hours under an incandescent lamp (100 W, GE lighting). FR-targeting nanoprobes were fabricated by coupling folate into the IR750-loaded nanoparticles (folate: NP = 2:5 weight ratio) using an established EDC procedure [38,39]. Coupling efficiency of folate was estimated to be 0.3wt% (folate percentage of the nanoprobe) by using UV spectroscopic method as described in previous publications [40-42].

Cytotoxicity assay of FR-targeting nanoprobes

Cytotoxicity of the FR-targeting nanoprobes was evaluated using a standard MTS assay [43]. In brief, mouse 3T3 fibroblasts were seeded in a 96-well plate at the density of 1× 104 cells/well in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) + 1% antibiotics for 24 hours with 5% CO2 at 37°C. The culture medium in each well was then replaced with 200 μL of complete DMEM medium in the presence or absence of various concentrations of FR-targeting nanoprobes. After 24 hours incubation, the medium was then removed and adherent cells were washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). Twenty μl of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Reagent (Promega, USA) and 100 μl of DMEM medium were added into each well and incubated for 4 hours. Finally, the absorbance of MTS reaction was measured at 490 nm using a SpectraMax 340 Spectrophotometric plate Reader (Molecular Devices, USA).

In vitro MΦ targeting of FR-targeting nanoprobes

Murine Raw 264.7 MΦs (ATCC, Manassas, VA.) were used as model cells to assess the ability of FR-targeting nanoprobes in finding activated MΦ. Raw 264.7 MΦ were cultured in folate free Hank's balanced salt solution (HBSS, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in the presence of 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic at 37°C with 5% CO2 until 75% confluence. Culture media was deprived of folate to prevent down-regulation of the cell surface FR, which usually occurs when cells are cultured with elevated folate concentrations [44]. Prior to each experiment, cells were plated at 300,000 cells/500 μl/well in 24 well plates and then cultured overnight. To up-regulate cell surface FR expression, cultured Raw 264.7 MΦs were activated by the supplement of 1.0 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (from E-coli, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 4 hours as described earlier [45]. After LPS incubation, cells were washed twice with HBSS to remove non-adherent cells. Variously treated nanoprobes were then incubated with adherent cells for different periods of time, followed by washing cells with PBS buffer three times to remove unlabeled nanoprobes. The extent of nanoprobe accumulation was then quantified by measuring fluorescence intensity at emission of 830nm (excitation at 760 nm) using a Tecan Infinite M 200 plate reader (San Jose, CA). In addition, to verify whether nanoprobe accumulation is mediated by conjugated folate, a nanoprobe cell adhesion study was carried out in the presence of various concentrations (2.3 -18 μM) of free folate as established earlier [44].

In vivo inflammation models

Female Balb/c mice (20-25 gram), purchased from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY), were used in this investigation. The animal experiments were approved by the University of Texas at Arlington Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). To test the efficacy of FR-targeting nanoprobes in targeting distal inflammatory responses, subcutaneous inflammation was triggered by the subcutaneous injection of LPS as described earlier [46]. Briefly, LPS (100μg/50 μl saline/animal) or saline (50 μl, as a control) was injected subcutaneously in the back of mice. After injection for 24 hrs, mice were administered intravenously with FR-targeting nanoprobes or control nanoprobes (IR750-loaded nanoparticles) (0.1mg/mouse) and whole body images were taken subsequently at various time points. It should be noted that a 24 hours post-LPS administration time point was found to prompt the maximal inflammatory responses in our pilot study. To investigate foreign body reactions to particle implants, PLA particles (∼8 μm in diameter) and PEG particles (∼150 nm in diameter) were tested. These particles were synthesized using established procedures [47-49]. For in vivo testing, PLA and PEG particles (100 μl, 10% w/v) and saline (100 μl) were injected subcutaneously in various dorsal regions of the mouse. After particle implantation for 24 hours, mice were administered with FR-targeting nanoprobes (0.1mg per mouse) and then imaged.

In vivo animal imaging

Whole body images of mice were taken using KODAK In vivo FX Pro system with excitation wavelength of 760nm an emission wavelength of 830nm (f/stop, 2.5; no optical filter, 4×4 binning). After background correction, regions of interests (ROIs) were drawn over the implantation locations, and the mean fluorescence intensities for all pixels in the fluorescent images were calculated using Carestream Molecular Imaging Software, Network Edition 4.5 (Carestream Health).

Immunohistochemical evaluation of biomaterial-mediated tissue responses

To determine the extent of inflammatory responses to implants, at the end of the study, implants and surrounding tissues were isolated for immunohistochemical evaluation as described earlier [50,51]. Immunohistochemistry was performed to quantify the number of FR+ cells and CD11b+ cells using established procedures [30,50,51]. Briefly, to assess FR+ cells, some tissue sections were stained with a goat anti-mouse folate receptor polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-goat secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, PA). To evaluate inflammatory cells, some tissue sections were stained with inflammatory cell marker CD11b (rat anti-mouse MAC-1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), monocyte/macrophage marker (MOMA-1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rat secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, PA). All slides were treated with 3,3-diaminobenzidine substrate system and counterstained with hematoxylin. Positive immunoreactions appeared as dark brown staining on a blue background. All histological imaging analyses were performed on a Leica microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) and processed using NIH ImageJ [50,51]. To visualize the distribution of FR-targeting nanoprobes in tissues, fresh tissue sections were imaged using Zeiss Axiovert 200 microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., Thornwood, NY) with a cooled CCD camera as previously described [52,53].

Statistical analyses

All the results will be expressed as mean ± Standard error of the mean (SEM). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and student t-test were performed to compare the difference between groups. A value of p<= 0.05 was considered to be significant. Linear regression analyses was used to determine the relationship between fluorescent intensities and cell numbers in vitro, as well as assessing the correlation between fluorescent intensities and macrophage cell numbers in vivo. The coefficient of determination (R2) was calculated providing a measure of correlation.

3.Results

Fabrication and characterization of FR-targeting nanoprobes

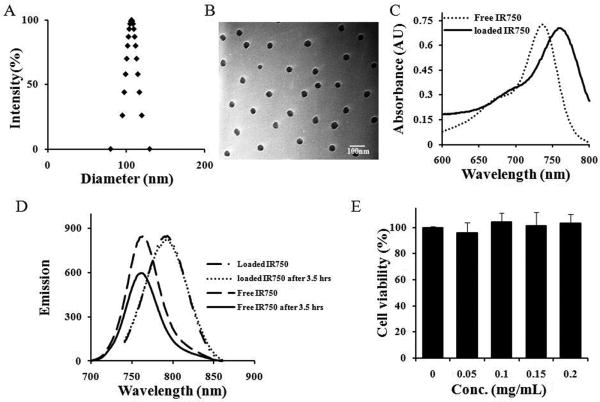

PNIPAM-co-St nanoparticles (NPs), synthesized by emulsion polymerization, had average diameter of ∼100 nm at 25°C. The NPs were found to be highly monodispersed as shown in Fig 1A. TEM images of the PNIPAM-co-St NPs revealed homogeneous and spherical morphology although the diameter of particles reduced to ∼40 nm due to dehydration during the process of sample preparation (Fig. 1B) [54]. IR750 is a hydrophobic dye with maximum absorbance at 731 nm and maximum emission at 758 nm (Fig. 1C-D). To label NPs, IR750 was physically encapsulated into the polystyrene-rich domains of the nanoparticles by the hydrophobic association. The IR750-NPs loading efficiency was calculated to be about 3.5% (w/w) according to the calibration curve:y = 36.252 − 0.0061,R2 = 0.99. As reported elsewhere [36], a red shift of ∼24 nm and ∼32 nm was observed for the absorbance and emission of the loaded IR750 (Fig. 1C-D), respectively. This may be ascribed to the enhanced interactions between segments of the polystyrene chain, leading to a decrease of transition energy of chromophores of IR750 [55].

Fig. 1.

(A) Size distribution of PNIPAM-co-St at 25 °C. (B) Transmittance electron microscope (TEM) images of P(NIPAM-co-St). (C) Absorbance spectra of free and loaded IR750. (D) Emission spectra of free and entrapped IR750. (E) Cytotoxicity study of FR-targeting nanoprobe using MTS assay.

Additionally, as the hydrophobic microenvironment of polystyrenes was impermeable to solvent (water) and oxidative agents, such as dissolved oxygen, the photostability of the physically-entrapped IR750 was substantially improved (Fig. 1D) [36,55]. After exposure to light for 3.5 hours, emission intensity was decreased by ∼30% for free IR750 but only by ∼3% for the loaded IR750 (Supp. Fig.1). FR-targeting nanoprobes were obtained by conjugating folate into IR750-loaded nanoparticles using carbodiimide coupling methods. The cytotoxicity of FR-targeting nanoprobes was determined using 3T3 fibroblasts and MTS assay (Fig.1E). We find that the FR-targeting nanoprobes trigger no statistically significant cytotoxicity over the studied concentration range (up to 0.2 mg/ml), indicating that the above-prepared nanoprobes possess adequate cell compatibility for further in vivo testing.

Effectiveness of FR-targeting nanoprobes on targeting activated MΦ in vitro

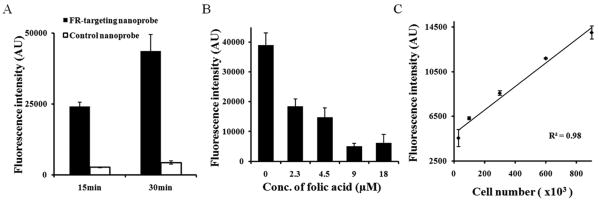

To investigate the interaction between FR-targeting nanoprobes and activated MΦ, LPS-treated rat Raw 264.7 MΦs were incubated with FR-targeting nanoprobes or control nanoprobes for either 15 or 30 minutes. The results show that a substantial amount (∼9 fold compared with controls) of FR-targeting nanoprobes were associated with activated MΦ after 15 minutes of exposure and that the uptake of FR-targeting nanoprobes increased after 30 minutes of exposure (∼10 fold compared with controls) (Fig. 2A). To further confirm the role of nanoprobe surface-bound folate in targeting activated MΦ, we performed a competition binding test in which free folate molecules were introduced to the medium before the addition of FR-targeting nanoprobes. As expected, fluorescence intensity is substantially decreased with increasing concentrations of free folate, suggesting that FR-targeting nanoprobes have high affinity for activated MΦ (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, by incubating FR-targeting nanoprobes with different numbers of activated MΦ, we find that there is a linear relationship between the activated MΦ numbers and fluorescence intensities (Fig. 2C). This data supports our hypothesis that FR-targeting nanoprobes may be used to quantify the number of activated MΦ in vitro.

Fig. 2.

In vitro study to assess the nanoprobe specificity to activated macrophages. (A) Influence of incubation time on the accumulation of FR-targeting nanoprobe and control nanoprobe onto activated macrophages. (B) Interference of different concentrations of free folate molecules on the binding of FR-targeting nanoprobe to activated macrophages; (C) Correlation between activated macrophage number and nanoprobe fluorescence intensity.

Detection of activated MΦ in vivo using FR-targeting nanoprobes

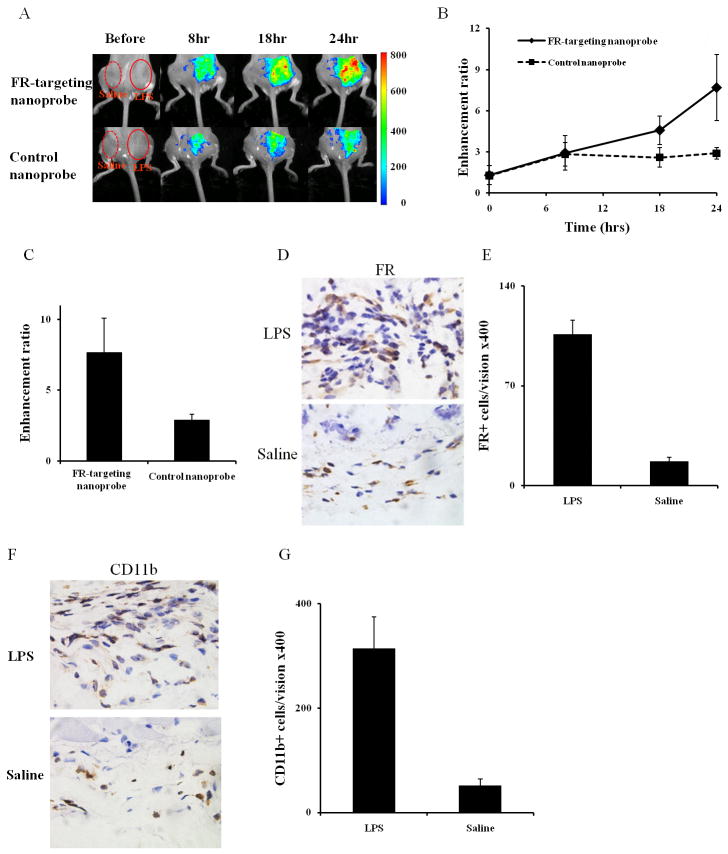

To test whether FR-targeting nanoprobes can be used to detect activated MΦ accumulation in inflamed tissue in vivo, a LPS induced subcutaneous inflammation model was used. After 24 hours LPS challenge, FR-targeting nanoprobes or control nanoprobes were administered intravenously. Our results reveal that the fluorescence intensities at the LPS injection site, regardless FR-targeting nanoprobes or control nanoprobes, were substantially higher than saline controls (Fig 3A-B). We also determined the ability of nanoprobes to distinguish inflamed vs. control tissues by calculating their enhancement ratios (ratios of fluorescence intensity at LPS-site vs. saline-site). Indeed, the enhancement ratio for FR-targeting nanoprobes is higher than that for their controls 18 hours after nanoprobe injection. At 24 hours, our results show a substantially higher fluorescence enhancement ratio (∼2.7 fold) in the FR-targeting nanoprobe group than that in its control group (Fig 3C). Histological evaluations also show that the LPS challenge resulted in tissue with ∼6 times higher FR+ inflammatory cells than saline treatment (Fig. 3D-E). As expected, we also found that the LPS-challenge triggered ∼6 times higher CD11b+ inflammatory cell recruitment than the saline control (Fig. 3F-G). These results strongly support our hypothesis that FR-targeting nanoprobes have the ability to noninvasively detect activated MΦ and may be used to monitor the biomaterial-mediated inflammatory processes in real time.

Fig.3.

In the LPS-induced inflammation model, the FR-targeting nanoprobe and its control nanoprobe were injected intravenously 24hrs after LPS subcutaneous administration. (A) The merged fluorescent signal with a white-light animal image for the FR-targeting nanoprobe groups and the control nanoprobe groups at different time points following nanoprobe administration. (B) The enhancement ratio of LPS-induced inflamed sites vs. saline control in the FR-targeting nanoprobe and the control nanoprobe at different time points. (C) The enhancement ratios of fluorescence intensities between FR-targeting nanoprobe and control nanoprobe in LPS-treated inflamed sites at 24 hours. (D) Representative FR+ cell staining and (E) FR+ cell number quantification in isolated tissue 24 hours following either LPS or saline treatment. (F) Representative CD11b+ cell staining and (G) CD11b+ cell number quantification of LPS- and saline-treated tissues isolated 24 hours after nanoprobe injection.

Quantification of foreign body reactions in vivo using FR-targeting nanoprobes

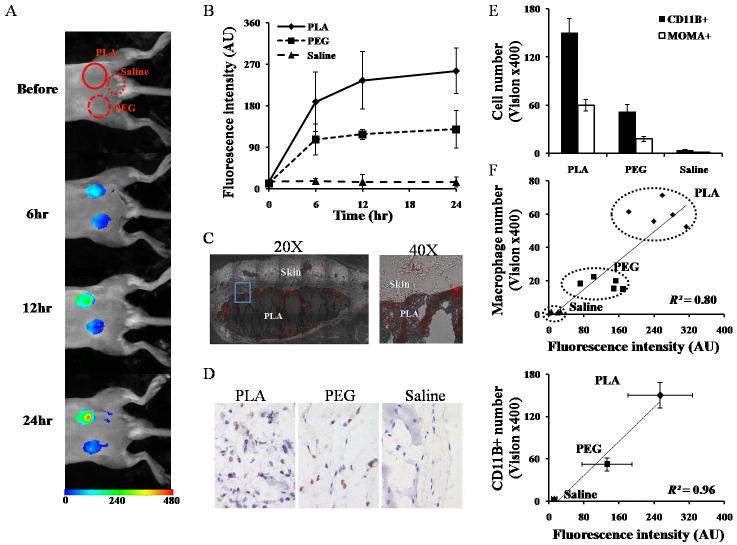

Subsequent studies were carried out to explore the possibility of using FR-targeting nanoprobes to assess inflammatory reactions to different biomaterial implants in vivo. PLA and PEG particles were chosen as model materials which have been shown to trigger strong and weak inflammatory responses, respectively [48,56]. After prior injection (24 hour incubation) with different types of particles or saline as injection control, the FR-targeting nanoprobes were introduced via tail vein injection and the animals were subjected to whole-body imaging at various time points (Fig. 4A). In general, fluorescent signals in both PLA and PEG sites increased over time, and the signal intensities in PLA implantation sites were consistently higher than those in PEG sites (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, saline controls had very low or no fluorescent signals during the same time periods. The varying trends of fluorescence intensities were consistent and statistically significant between different test materials 6 hours after FR-targeting nanoprobe injection (Fig. 4B). To determine the distribution of the nanoprobe in the inflamed tissue, NIR microscopic images of sections of PLA implant sites were taken (Fig. 4C). The microscopic images show that abundant FR-targeting nanoprobes accumulated in tissue adjacent to the PLA implant and that substantially less nanoprobes are found in normal tissue.

Fig.4.

In an implant-mediated inflammatory responses model, PLA particles, PEG particles and saline were implanted subcutaneously in the back of animals for 24 hours prior to FR-targeting nanoprobe intravenous administration. (A) The merged fluorescent signal with a white-light image captured at different time points following nanoprobe injection. (B) The fluorescence intensities in different implantation sites (PLA, PEG and saline) at different time points. After nanoprobe injection for 24 hours, the tissues surrounding implant sites were isolated for the following measurements. (C) NIR fluorescence (red) acquisition superimposed onto the correlative phase contrast microscopy image in the whole stitched image (20X) and enlarged view (40X). The tissue section was unstained and unfixed to preserve fluorescent signal. (D) Representative histological images and (E) quantification of CD11b+ inflammatory cells and MOMA+ macrophages in tissue surrounding PLA-, PEG- and saline-implanted tissue. (F) Correlation between CD11b+ cell number/macrophages number and fluorescence intensity at the implant sites.

Immunohistochemical analyses reveals that, after 24 hour implantation, the saline injection prompted negligible CD11b+ inflammatory cell recruitment, and that the PLA implants are consistently infiltrated by more CD11b+ inflammatory cells than the PEG implants (Fig. 4D). Similar trends were also found for monocyte/macrophages (MOMA+ cells) recruitment. Overall, it was found that the PLA implants recruited 3 times higher CD11b+ inflammatory cells and MOMA+ macrophages than PEG implants (Fig 4E). To determine the relationship between FR-targeting nanoprobe accumulation and implant-mediated macrophage responses, we correlate both the CD11b+ inflammatory cells and MOMA+ macrophage count with the fluorescence intensity. Our results show good near linear trends in both cases (R2=0.80-0.96) (Fig 4F). These results support our assumption that FR-targeting nanoprobes can be employed as an effective imaging probe to detect and to assess the extent of biomaterial-mediated macrophage recruitment and inflammatory responses in vivo.

4. Discussion

In the present study, FR-targeting NIR nanoprobes based on PNIPAM-co-St nanoparticles were prepared to noninvasively evaluate inflammation by targeting activated MΦs. The uniform nanoparticle with an average diameter of ∼100 nm makes it a suitable vehicle for in vivo imaging. Previous studies suggest that particles ranging from 10 nm to 200nm are optimal for prolonging blood circulating times [57]. Furthermore, the presence of PNIPAM segments on the nanoparticles may greatly reduce the binding of plasma proteins to the particles, thus enhancing particle bio-distribution [58-60]. Finally, it has been reported that PNIPAM and PNIPAM-based nanoparticles exhibit no or little cytotoxicity [48,54].

Our in vitro studies demonstrate that FR-targeting nanoprobes can be used to assess the number of recruited and activated MΦs in vivo. The success of this strategy is supported by many previous findings. Specifically, activated MΦs have up-regulated FR expression which has previously been used for targeting molecules [29,39]. Interestingly, similar to our findings, prolonged incubation time was found to enhance uptake of FR-targeting nanoprobes which may be ascribed to a folate-mediated endocytosis by MΦs [28]. It is possible that prolonged exposure to activated MΦs may lead to the endocytosis of initial adherent FR-targeting nanoprobes while allowing additional probes to be bound to FRs on the cell surface. Such internalization may increase the resident time of FR-targeting nanoprobes and increase the sensitivity of such nanoprobes for detection of activated MΦ at the implantation sites in vivo.

FR-targeting nanoprobes were found to preferentially accumulate in the LPS-induced inflamed tissue. These results support the hypothesis that such nanoprobes can be used to detect activated MΦs and to indirectly assess the extent of inflammatory responses in tissue. This assumption is supported by many previous observations. First, it is well established that the administration of LPS prompts a localized inflammatory responses with the upregulation of many inflammatory cytokines [61,62]and the accumulation of inflammatory cells, including activated MΦ [30,56,63]. Second, by targeting activated MΦ, several strategies have been developed to deliver therapeutic and imaging agents [25,28,29,31,64]. Finally, FR-targeting imaging probes have been developed to noninvasively analyze inflammatory activity in atherosclerosis and arthritis in situ [29-31,44]. Interestingly, our study has also uncovered that, despite of a lack of folate, some control nanoprobes were found in the inflammatory tissue. The cause of non-specific accumulation has yet to be determined. However, it has been suggested that nanoparticle accumulation in tissue could be mediated by nonspecific phagocytosis or entrapment in the interstitial space due to the “enhanced permeability and retention” effect (EPR effect) within the inflammation tissues [63,65].

Using polymer particles as model implants, our studies have preliminarily explored the possibility of using FR-targeting nanoprobes to detect activated MΦs in the biomaterial implantation sites. Further analyses revealed that there is a good relationship between FR-targeting nanoprobe accumulation and CD11b+ inflammatory cell/macrophage recruitment in the implantation sites. These results demonstrate that the FR-targeting nanoprobes can be used not only to determine the inflammation location as reported earlier [25,30,31], but also to estimate the extent of biomaterial-mediated macrophage recruitment and associated inflammatory responses. We believe that FR-targeting nanoprobes can also be used to quantify the degree of inflammatory responses to other types of biomaterial implants. Since the FR-targeting nanoprobes are designed to target activated MΦs, representing the major subset of the inflammatory cells, we believe that FR-targeting nanoprobes would provide heightened sensitivity and reliability in the assessment of cellular responses to biomaterial implants, as opposed to other imaging probes currently testing foreign body reactions. Equally important, we anticipate that the FR-targeting nanoprobe-based in vivo fluorescence imaging can provide an alternative method for analyzing biomaterial biocompatibility in a rapid, non-invasive and realtime manner. This would greatly improve our understanding of the processes and factors governing foreign body responses to biomaterials. Furthermore, this fluorescence imaging technique may have a practical application in the evaluation and diagnosis of implant safety and performance.

5. Conclusions

FR-targeting NIR nanoprobes have been developed to target activated MΦs. These nanoprobes were found to have high affinity for activated MΦs in vitro and in the LPS-induced inflamed tissue in vivo. Further study has uncovered that these FR-targeting nanoprobes can be used to detect activated MΦs surrounding biomaterial implants and to assess the overall inflammatory reactions to the subcutaneous implants. These results support that the FR-targeting nanoprobe-based imaging model developed here can provide a rapid noninvasive technique for parallel evaluation of biomaterial tissue compatibility in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant EB007271. The authors would like to thank Drs. Wei Chen and Digant Dave for their facility support to carry out some of the experimental works.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Anderson JM, Rodriguez A, Chang DT. Foreign body reaction to biomaterials. Semin Immunol. 2008;20:86–100. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grayson ACR, Shawgo RS, Johnson AM, Flynn NT, Li YW, Cima MJ, et al. A BioMEMS review: MEMS technology for physiologically integrated devices. P IEEE. 2004;92:6–21. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang L, Eaton JW. Natural responses to unnatural materials: a molecular mechanism for foreign body reactions. Mol Med. 1999;5:351–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ziats NP, Miller KM, Anderson JM. In vitro and in vivo interactions of cells with biomaterials. Biomaterials. 1988;9:5–13. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(88)90063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller KM, Anderson JM. Human monocyte/macrophage activation and interleukin 1 generation by biomedical polymers. J Biomed Mater Res. 1988;22:713–31. doi: 10.1002/jbm.820220805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oreffo RO, Triffitt JT. In vitro and in vivo methods to determine the interactions of osteogenic cells with biomaterials. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 1999;10:607–11. doi: 10.1023/a:1008931607002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee KY, Ha WS, Park WH. Blood compatibility and biodegradability of partially N-acylated chitosan derivatives. Biomaterials. 1995;16:1211–6. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(95)98126-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Courtney JM, Lamba NM, Sundaram S, Forbes CD. Biomaterials for blood-contacting applications. Biomaterials. 1994;15:737–44. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Narayan R SpringerLink. Biomedical materials. New York: Springer; 2009. Online service. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Setiadi AF, Ray NC, Kohrt HE, Kapelner A, Carcamo-Cavazos V, Levic EB, et al. Quantitative, architectural analysis of immune cell subsets in tumor-draining lymph nodes from breast cancer patients and healthy lymph nodes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindner JR, Song J, Xu F, Klibanov AL, Singbartl K, Ley K, et al. Noninvasive ultrasound imaging of inflammation using microbubbles targeted to activated leukocytes. Circulation. 2000;102:2745–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.22.2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhuang H, Alavi A. 18-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomographic imaging in the detection and monitoring of infection and inflammation. Semin Nucl Med. 2002;32:47–59. doi: 10.1053/snuc.2002.29278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Truijers M, Kurvers HA, Bredie SJ, Oyen WJ, Blankensteijn JD. In vivo imaging of abdominal aortic aneurysms: increased FDG uptake suggests inflammation in the aneurysm wall. J Endovasc Ther. 2008;15:462–7. doi: 10.1583/08-2447.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAteer MA, Sibson NR, von Zur Muhlen C, Schneider JE, Lowe AS, Warrick N, et al. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging of acute brain inflammation using microparticles of iron oxide. Nat Med. 2007;13:1253–8. doi: 10.1038/nm1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brasuel M, Kopelman R, Miller TJ, Tjalkens R, Philbert MA. Fluorescent nanosensors for intracellular chemical analysis: decyl methacrylate liquid polymer matrix and ion-exchange-based potassium PEBBLE sensors with real-time application to viable rat C6 glioma cells. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73:2221–8. doi: 10.1021/ac0012041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark HA, Kopelman R, Tjalkens R, Philbert MA. Optical nanosensors for chemical analysis inside single living cells. 2. sensors for pH and calcium and the intracellular application of PEBBLE sensors. Analytical Chemistry. 1999;71:4837–43. doi: 10.1021/ac990630n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fehr M, Frommer WB, Lalonde S. Visualization of maltose uptake in living yeast cells by fluorescent nanosensors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9846–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142089199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ji J, Rosenzweig N, Griffin C, Rosenzweig Z. Synthesis and application of submicrometer fluorescence sensing particles for lysosomal pH measurements in murine macrophages. Analytical Chemistry. 2000;72:3497–503. doi: 10.1021/ac000080p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McNamara KP, Nguyen T, Dumitrascu G, Ji J, Rosenzweig N, Rosenzweig Z. Synthesis, characterization, and application of fluorescence sensing lipobeads for intracellular pH measurements. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73:3240–6. doi: 10.1021/ac0102314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan M, Wang G, Hai X, Ye Z, Yuan J. Development of functionalized fluorescent europium nanoparticles for biolabeling and time-resolved fluorometric applications. J Mater Chem. 2004;14:2896–901. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang L, Yang C, Tan W. Dual-luminophore-doped silica nanoparticles for multiplexed signaling. Nano Lett. 2005;5:37–43. doi: 10.1021/nl048417g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu H, Aylott JW, Kopelman R, Miller TJ, Philbert MA. A real-time ratiometric method for the determination of molecular oxygen inside living cells using sol-gel-based spherical optical nanosensors with applications to rat C6 glioma. Analytical Chemistry. 2001;73:4124–33. doi: 10.1021/ac0102718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frangioni JV. In vivo near-infrared fluorescence imaging. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2003;7:626–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bratlie KM, Dang TT, Lyle S, Nahrendorf M, Weissleder R, Langer R, et al. Rapid biocompatibility analysis of materials via in vivo fluorescence imaging of mouse models. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Low PS, Henne WA, Doorneweerd DD. Discovery and development of folic-acid-based receptor targeting for imaging and therapy of cancer and inflammatory diseases. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:120–9. doi: 10.1021/ar7000815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turk MJ, Waters DJ, Low PS. Folate-conjugated liposomes preferentially target macrophages associated with ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2004;213:165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puig-Kroger A, Sierra-Filardi E, Dominguez-Soto A, Samaniego R, Corcuera MT, Gomez-Aguado F, et al. Folate receptor beta is expressed by tumor-associated macrophages and constitutes a marker for M2 anti-inflammatory/regulatory macrophages. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9395–403. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hilgenbrink AR, Low PS. Folate receptor-mediated drug targeting: from therapeutics to diagnostics. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:2135–46. doi: 10.1002/jps.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turk MJ, Breur GJ, Widmer WR, Paulos CM, Xu LC, Grote LA, et al. Folate-targeted imaging of activated macrophages in rats with adjuvant-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:1947–55. doi: 10.1002/art.10405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen WT, Mahmood U, Weissleder R, Tung CH. Arthritis imaging using a near-infrared fluorescence folate-targeted probe. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R310–R7. doi: 10.1186/ar1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paulos CM, Turk MJ, Breur GJ, Low PS. Folate receptor-mediated targeting of therapeutic and imaging agents to activated macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2004;56:1205–17. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu Y, Stinnette TW, Westrick E, Klein PJ, Gehrke MA, Cross VA, et al. Treatment of experimental adjuvant arthritis with a novel folate receptor-targeted folic acid-aminopterin conjugate. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R56. doi: 10.1186/ar3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yi YS, Ayala-Lopez W, Kularatne SA, Low PS. Folate-targeted hapten immunotherapy of adjuvant-induced arthritis: comparison of hapten potencies. Mol Pharm. 2009;6:1228–1236. doi: 10.1021/mp900070b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hellweg T, Dewhurst CD, Eimer W, Kratz K. PNIPAM-co-polystyrene core-shell microgels: structure, swelling behavior, and crystallization. Langmuir. 2004;20:4330–5. doi: 10.1021/la0354786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blackburn WH, Lyon LA. Size controlled synthesis of monodispersed, core/shell nanogels. Colloid Polym Sci. 2008;286:563–9. doi: 10.1007/s00396-007-1805-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J, Chen H, Xu L, Gu Y. The targeted behavior of thermally responsive nanohydrogel evaluated by NIR system in mouse model. J Control Release. 2008;131:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2008.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ji T, Muenker MC, Papineni RV, Harder JW, Vizard DL, McLaughlin WE. Increased sensitivity in antigen detection with fluorescent latex nanosphere-IgG antibody conjugates. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:427–435. doi: 10.1021/bc900295v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dube D, Francis M, Leroux JC, Winnik FM. Preparation and tumor cell uptake of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) folate conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2002;13:685–92. doi: 10.1021/bc010084g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nayak S, Lee H, Chmielewski J, Lyon LA. Folate-mediated cell targeting and cytotoxicity using thermoresponsive microgels. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:10258–9. doi: 10.1021/ja0474143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quintana A, Raczka E, Piehler L, Lee I, Myc A, Majoros I, et al. Design and function of a dendrimer-based therapeutic nanodevice targeted to tumor cells through the folate receptor. Pharm Res. 2002;19:1310–6. doi: 10.1023/a:1020398624602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Henne WA, Doorneweerd DD, Lee J, Low PS, Savran C. Detection of folate binding protein with enhanced sensitivity using a functionalized quartz crystal microbalance sensor. Anal Chem. 2006;78:4880–4. doi: 10.1021/ac060324r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaidya B, Paliwal R, Rai S, Khatri K, Goyal AK, Mishra N, et al. Cell-selective mitochondrial targeting: a new approach for cancer therapy. Cancer Therapy. 2009;7:141–8. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braydich-Stolle L, Hussain S, Schlager JJ, Hofmann MC. In vitro cytotoxicity of nanoparticles in mammalian germline stem cells. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:412–9. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Antohe F, Radulescu L, Puchianu E, Kennedy MD, Low PS, Simionescu M. Increased uptake of folate conjugates by activated macrophages in experimental hyperlipemia. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;320:277–85. doi: 10.1007/s00441-004-1071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hattori Y, Sakaguchi M, Maitani Y. Folate-linked lipid-based nanoparticles deliver a NFkappaB decoy into activated murine macrophage-like RAW264.7 cells. Biol Pharm Bull. 2006;29:1516–20. doi: 10.1248/bpb.29.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shapira L, Soskolne WA, Houri Y, Barak V, Halabi A, Stabholz A. Protection against endotoxic shock and lipopolysaccharide-induced local inflammation by tetracycline: correlation with inhibition of cytokine secretion. Infect Immun. 1996;64:825–8. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.825-828.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cai T, Marquez M, Hu Z. Monodisperse thermoresponsive microgels of poly(ethylene glycol) analogue-based biopolymers. Langmuir. 2007;23:8663–6. doi: 10.1021/la700923r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weng H, Zhou J, Tang L, Hu Z. Tissue responses to thermally-responsive hydrogel nanoparticles. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2004;15:1167–80. doi: 10.1163/1568562041753106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bodmeier R, McGinity JW. Polylactic acid microspheres containing quinidine base and quinidine sulphate prepared by the solvent evaporation method. III. morphology of the microspheres during dissolution studies. J Microencapsul. 1988;5:325–30. doi: 10.3109/02652048809036729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thevenot PT, Nair AM, Shen J, Lotfi P, Ko CY, Tang L. The effect of incorporation of SDF-1alpha into PLGA scaffolds on stem cell recruitment and the inflammatory response. Biomaterials. 2010;31:3997–4008. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baker DW, Liu X, Weng H, Luo C, Tang L. Fibroblast/fibrocyte: surface interaction dictates tissue reactions to micropillar implants. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:997–1005. doi: 10.1021/bm1013487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weissleder R, Tung CH, Mahmood U, Bogdanov A., Jr In vivo imaging of tumors with protease-activated near-infrared fluorescent probes. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:375–8. doi: 10.1038/7933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hansch A, Frey O, Sauner D, Hilger I, Haas M, Malich A, et al. In vivo imaging of experimental arthritis with near-infrared fluorescence. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:961–7. doi: 10.1002/art.20112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naha PC, Bhattacharya K, Tenuta T, Dawson KA, Lynch I, Gracia A, et al. Intracellular localisation, geno- and cytotoxic response of polyN-isopropylacrylamide (PNIPAM) nanoparticles to human keratinocyte (HaCaT) and colon cells (SW 480) Toxicol Lett. 2010;198:134–43. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu C, Szymanski C, McNeill J. Preparation and encapsulation of highly fluorescent conjugated polymer nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2006;22:2956–60. doi: 10.1021/la060188l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruan G, Feng SS. Preparation and characterization of poly(lactic acid)-poly(ethylene glycol)-poly(lactic acid) (PLA-PEG-PLA) microspheres for controlled release of paclitaxel. Biomaterials. 2003;24:5037–44. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00419-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stolnik S, Illum L, Davis SS. Long circulating microparticulate drug carriers. Adv Drug Deliver Rev. 1995;16:195–214. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cedervall T, Lynch I, Lindman S, Berggard T, Thulin E, Nilsson H, et al. Understanding the nanoparticle-protein corona using methods to quantify exchange rates and affinities of proteins for nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2050–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608582104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aggarwal P, Hall JB, McLeland CB, Dobrovolskaia MA, McNeil SE. Nanoparticle interaction with plasma proteins as it relates to particle biodistribution, biocompatibility and therapeutic efficacy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:428–37. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sutton D, Nasongkla N, Blanco E, Gao J. Functionalized micellar systems for cancer targeted drug delivery. Pharm Res. 2007;24:1029–46. doi: 10.1007/s11095-006-9223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schutte RJ, Xie L, Klitzman B, Reichert WM. In vivo cytokine-associated responses to biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2009;30:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lang CH, Silvis C, Deshpande N, Nystrom G, Frost RA. Endotoxin stimulates in vivo expression of inflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1beta, -6, and high-mobility-group protein-1 in skeletal muscle. Shock. 2003;19:538–546. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000055237.25446.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koning GA, Schiffelers RM, Wauben MH, Kok RJ, Mastrobattista E, Molema G, et al. Targeting of angiogenic endothelial cells at sites of inflammation by dexamethasone phosphate-containing RGD peptide liposomes inhibits experimental arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1198–208. doi: 10.1002/art.21719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nakashima-Matsushita N, Homma T, Yu S, Matsuda T, Sunahara N, Nakamura T, et al. Selective expression of folate receptor beta and its possible role in methotrexate transport in synovial macrophages from patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1609–1616. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199908)42:8<1609::AID-ANR7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Maeda H, Bharate GY, Daruwalla J. Polymeric drugs for efficient tumor-targeted drug delivery based on EPR-effect. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2009;71:409–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.