Abstract

Recent work has demonstrated that antibody phage display libraries containing restricted diversity in the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) can be used to target a wide variety of antigens with high affinity and specificity. In the most extreme case, antibodies whose combining sites are comprised of only two residues – tyrosine and serine – have been identified against several protein antigens. [F. A. Fellouse, B. Li, D. M. Compaan, A. A. Peden, S. G. Hymowitz, and S. S. Sidhu, J. Mol. Biol., 348 (2005) 1153–1162.] Here, we report the isolation and characterization of antigen-binding fragments (Fabs) from such “minimalist” diversity synthetic antibody libraries that bind the heptad repeat regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) gp41. We show that these Fabs are highly specific for the HIV-1 epitope and comparable in affinity to a single chain variable fragment (scFv) derived from a natural antibody repertoire that targets the same region. Since the heptad repeat regions of HIV-1 gp41 are required for viral entry, these Fabs have potential for use in therapeutic, research, or diagnostic applications.

Keywords: Antibody engineering, Phage display, HIV-1

1. Introduction

Infection by human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) requires fusion between the viral and host cell membranes [1, 2]. This process is facilitated by the virus’s envelope glycoproteins, gp120 and gp41, which exist as a hexameric assembly on the native viral spike (three molecules each of gp120 and gp41) [3, 4]. The gp41 primary structure consists of an N-terminal fusion peptide region, an ectodomain containing two heptad repeat regions (N- and C-terminal, denoted NHR and CHR, respectively), a transmembrane domain, and a C-terminal domain [5, 6]. In the prefusion spike assembly, gp120 is non-covalently associated with gp41 which is anchored into the viral membrane. Viral entry is initiated by recognition of cell-surface receptors (CD4 and the coreceptors CXCR4 or CCR5) by gp120 [3, 4]. Next, gp41 undergoes a conformational change that results in insertion of the fusion peptide into the host cell membrane. This rearrangement gives rise to a structural intermediate known as the ‘extended’ or ‘prehairpin’ intermediate in which the gp41 ectodomain spans both the cell and virus membranes, and in which the NHR and CHR are exposed to the extraviral environment [1, 2, 5, 6]. Next, the NHR and CHR collapse to form a highly stable six-helix bundle [5, 6]. Formation of this six-helix bundle brings the cell and virus membranes into close proximity and facilitates lipid mixing. Ultimately, a fusion pore is formed through which the contents of the viral particle are released into the cellular cytosol [1]. The extended intermediate is long-lived (on the order of minutes) and therefore can be targeted by small molecules, peptides, or antibodies that bind these exposed regions and prevent their rearrangement to the six-helix bundle [7, 8]. One such peptide, T-20/enfuvirtide, is a potent HIV-1 entry inhibitor that has been approved by the FDA for clinical use [1, 2, 7–11]. In addition, the isolation of neutralizing antibodies from naïve or memory repertoires that bind these regions suggests the NHR and CHR segments may be useful templates for immunogen design [9–11].

There is growing interest in development and application of antibody of libraries in which diversity at the complementarity determining regions (CDRs) is encoded by designed, synthetic oligonucleotides (‘synthetic antibodies’) [12–16]. Selection and screening of synthetic antibodies is typically performed by a display method (most commonly phage display) [13]. Since the entire process of library design, construction, and selection of synthetic antibodies is performed in vitro, this approach is not dependent on cloning of antibody variable domains from natural source repertoires [13]. Therefore, this approach offers considerable advantages over other antibody isolation methods in terms of rapidity and functional properties of the resulting antibodies [12–20]. A number of randomization schemes for diversity of the CDRs have been described; many are based on structural analysis of functional paratopes from existing antibody-antigen interactions [12, 14, 17–20]. The groups of Sidhu, Koide, Koissiakoff, and others have demonstrated that synthetic antibody libraries containing restricted diversity – that is, variation among only a few of the 20 natural amino acids – can be used to identify specific binders against a number of protein antigens [17–19]. In the most extreme example, antibody fragments in which the combining site is comprised of just two residues – tyrosine and serine (“minimalist” antibodies) – have been isolated against the antigens human vascular endothelial growth factor (hVEGF), human death receptor (hDR5), insulin, and others [18, 19]. Tyr and Ser have optimal physicochemical properties to engage in molecular recognition and are enriched in natural combining site interactions [12].

Given the value of antibodies that bind the gp41 NHR and CHR regions for research or other purposes, we identified and characterized minimalist antigen-binding fragments (Fabs) that bind a designed protein containing the gp41 NHR and CHR segments that mimics the extended intermediate conformation (“5-Helix”) [8, 20]. We characterized these Fabs in vitro and found they were highly specific for 5-Helix, and comparable in affinity to a natural antibody that targets the same antigen.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Strains and vectors

The phagemid pJH3 displaying the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) of the antibody D5 as a fusion to the C-terminal 188 residues of M13 coat protein pIII (pIII-CT) was previously described [21]. This phagemid was modified for bivalent D5 scFv by insertion of a DNA segment encoding the IgG hinge region and a GCN4 leucine zipper segment between the scFv and pIII-CT [22]. The E. coli strain SS320 was used for library construction and was prepared by mating MC1016 (obtained from the Yale University Coli Genetic Stock Center) and XL1-Blue (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA). Helper phage were obtained from New England Biolabs (NEB, Ipswich, MA) (K07) or Stratagene (VCSM13).

2.2 Synthesis and selection of minimalist phage display Fab libraries

The region of pJH3 upstream of pIII-CT was modified to include two open reading frames: one encoding the light chain of the synthetic antibody YADS1 and a second encoding the YADS1 heavy chain variable and constant domains linked to the IgG hinge region, GCN4, and pIII-CT [22, 23]. This bivalent Fab display phagemid (pAS-Fab2zip) served as the scaffold for Tyr/Ser library construction which was performed essentially as described [18, 21]. An inactivated clone based on pAS-Fab2zip in which HCDR2 and HCDR3 regions had been replaced by poly rare-Arginine codon segments was used as a template for Kunkel mutagenesis. Library diversity was introduced at LCDR3 and HCDR1-3 regions with synthetic oligonucleotides encoding Tyr/Ser binomial variation using the codon TMT (where M = A/C) [18]. Typical Kunkel mutagenesis reactions contained 20 μg of uridine-enriched template DNA and 3-fold excess of library primer. Library DNA was purified using a QIAgen PCR purification kit and then electroporated into competent E. coli SS320 cells that had been preinfected with helper phage. The cells were allowed to recover in LB broth at 37 °C for 30 mins, and then the media supplemented with 50 μg/mL carbenecillin and 25 μg/mL kanamycin, and the phage propagated an additional 20 hrs. The cells were removed by centrifugation and then the phage precipitated by addition of 3% (w/v) NaCl and 4% (w/v) PEG 8000. The phage were pelleted by centrifugation and then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) containing 1% (w/v) BSA. The phage libraries were used immediately for selections or stored at −80 °C.

The 5-Helix protein reported by Frey et al. (a.k.a. ‘gp41-5’) was purified as previously described [20, 21]. Wells in Costar high binding EIA/RIA plates (Corning, Big Flats, NY) were coated with 5-Helix (1 μg/well) in 100 mM NaHCO3 pH 8.5 for 1 hr at room temperature or overnight at 4 °C. The well solutions were decanted and unbound sites blocked by incubation with PBS/1% BSA for 1 hr. The wells were washed with PBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween 20 (PBS-T) and then library phage added at phage titers of ~1012 pfu/mL in PBS/1% BSA. Library phage were allowed to bind for 1 hr, then the wells were washed 5 times with PBS-T, and bound phage eluted by addition of 100 μL 100 mM glycine pH 2.0 for 5 mins. The eluted phage solution was neutralized in 30 μL of 2 M Tris pH 8 then propagated in XL1-Blue E. coli. The clones described in Table 1 were isolated from two independent selections performed with three rounds each.

Table 1.

Competitive ELISA IC50 determination for 5-Helix binding clones.

| Antibody Fragment | IC50 on-phage (bivalent) (nM)A | IC50 off-phage (monovalent) (nM)A |

|---|---|---|

| D5 scFv | 0.1 ± 0.03 | 4.1 ± 0.6 |

| 1G7 Fab | 1.1 ± 0.5 | 3.5 ± 4.7 |

| 1G1 Fab | 1.2 ± 0.3 | NDB |

| 1E10 Fab | 2.3 ± 0.9 | 4.2 ± 1.7 |

| 1E5 Fab | 4.7 ± 1.9 | 11 ± 4 |

| 1H5 Fab | NDB | ~ 120 |

| 2F10 Fab | ~ 50 | NDB |

| 1F12 Fab | ~ 120 | NDB |

Errors reported here represent 95% confidence interval from data fitting.

ND, not determined.

2.3 Phage enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Individual clones from the second and third rounds were analyzed for binding to 5-Helix and BSA using high throughput phage ELISA. Small-scale phage cultures (1 mL) were grown in deep 96-well plates at 30 °C for 20 hrs. The cells were removed by centrifugation and the supernatant applied directly to ELISA plate wells that had been coated with 5-Helix or BSA (as above). The phage were allowed to bind for 1 hr at room temperature, the solution decanted, and the wells washed 5 times with PBS-T. An anti-M13/horse radish peroxidise conjugate (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) was added as per the manufacturer’s protocol and incubated for 1 hr. The wells were washed with PBS-T and 100 μL of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, Pierce Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) substrate added. The color was allowed to develop for 5 mins, quenched with 0.5 M H2SO4, and the OD at 450nm determined.

2.4 Expression and purification of Fab protein

The phage display vectors were converted to protein expression vectors by replacement of the region downstream of the light chain variable domain (scFv) or the heavy chain constant domain (Fab) with a hexahistidine tag. This modification yields a periplasmic expression vector under control of the alkaline phosphatase (phoA) promoter. Proteins were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) by growth in low-phosphate media at 30 °C for 20 hrs. The cells were harvested by centrifugation and lysed with Bug Buster (Novagen, Madison, WI) as directed by the manufacturer. The lysate was clarified by ultracentrifugation and the soluble fraction applied to Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The beads were washed with 20 – 50 mM imidazole and then the protein eluted with 250 – 500 mM imidazole. Fractions containing scFv or Fab protein were pooled and dialyzed into PBS, pH 7.4. For Fab proteins, a second purification step was performed on protein A beads (Pierce Thermo Scientific). The protein solution was loaded onto protein A beads, then the beads were washed with PBS pH 8.5, and the Fab eluted with 100 mM glycine pH 2.0. The eluted protein was neutralized immediately with 1 M Tris, pH 8. Fractions containing the Fab protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight in PBS pH 7.4. Final purified proteins were used immediately for analysis or flash-frozen and stored at −80 °C.

2.5 Characterization of Fabs by ELISA and competition ELISA

Wells in Costar EIA/RIA plates were coated with 5-Helix or BSA as above. Phage or purified scFv/Fab protein were added at various concentrations and allowed to bind for 1 hr at room temperature. Wells were washed 5 times with PBS-T; bound phage were detected with anti-M13/HRP as above and scFv or Fab protein with anti-FLAG/HRP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO); all scFv or Fab proteins contained a FLAG sequence for detection) and TMB substrate. Competitive ELISA procedures were modified from ref. 24. ELISA experiments at various 5-Helix loading concentrations and scFv/Fab phage or protein titers were performed to identify conditions that would permit competition with reasonable dynamic range. Generally, scFv/Fab phage or protein titers were chosen at ~ 50 – 80% maximal binding signal for the competition experiment. The scFv/Fab phage or proteins were then preincubated for 20 mins with various concentrations of soluble 5-Helix and then the solutions transferred to wells containing immobilized 5-Helix. After 20 mins, the well solutions were decanted and the presence of scFv/Fab phage or protein detected using anti-M13/HRP (phage) or anti-FLAG/HRP (protein). Experiments were performed in triplicate. The OD signal at 450nm was converted to fraction bound and fit to a standard four-parameter logistic equation using the program Prism (Washington, NY). The IC50 was obtained from the inflection point of the curve.

3. Results

3.1 Phage display selection of minimalist Fabs that bind 5-Helix

We prepared a bivalently displayed Fab with Tyr/Ser randomization in LCDR3, and HCDR1-3 based on the scaffold of the synthetic antibody YADS1 [18, 23]. The design of this library was nearly identical to that reported by Fellouse et al. [18]. The LCDR3 and HCDR1-2 regions were of fixed length but HCDR3 loop sizes of 7, 9, and 12–15 amino acids were included. The library was produced with 5 × 109 total clones and large-scale sequencing indicated that library members contained the expected diversity in the CDR regions.

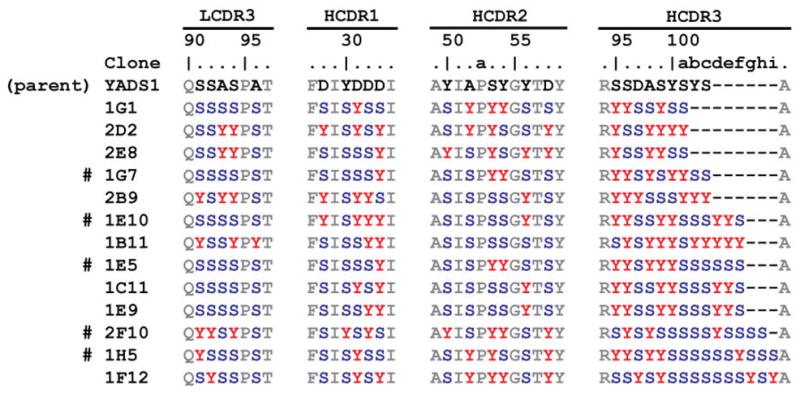

We next performed several rounds of selection against 5-Helix. Individual clones were screened by phage enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Clones that had strong, positive ELISA signal for 5-Helix that was 5-fold or higher than signals for BSA were sequenced. Overall, we identified 13 clones that matched these criteria. Sequences of LCDR3 and HCDR1-3 for these hits are shown in Figure 1; the clones contained a variety of HCDR3 loop lengths and distribution of Tyr and Ser throughout the CDRs.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of binding clones from the minimalist diversity library. LCDR3 and HCDR1-3 sequences of the parental clone (YADS1) and 13 clones that had high, specific ELISA signal for 5-Helix. Clones that were produced as Fab proteins are indicated with #.

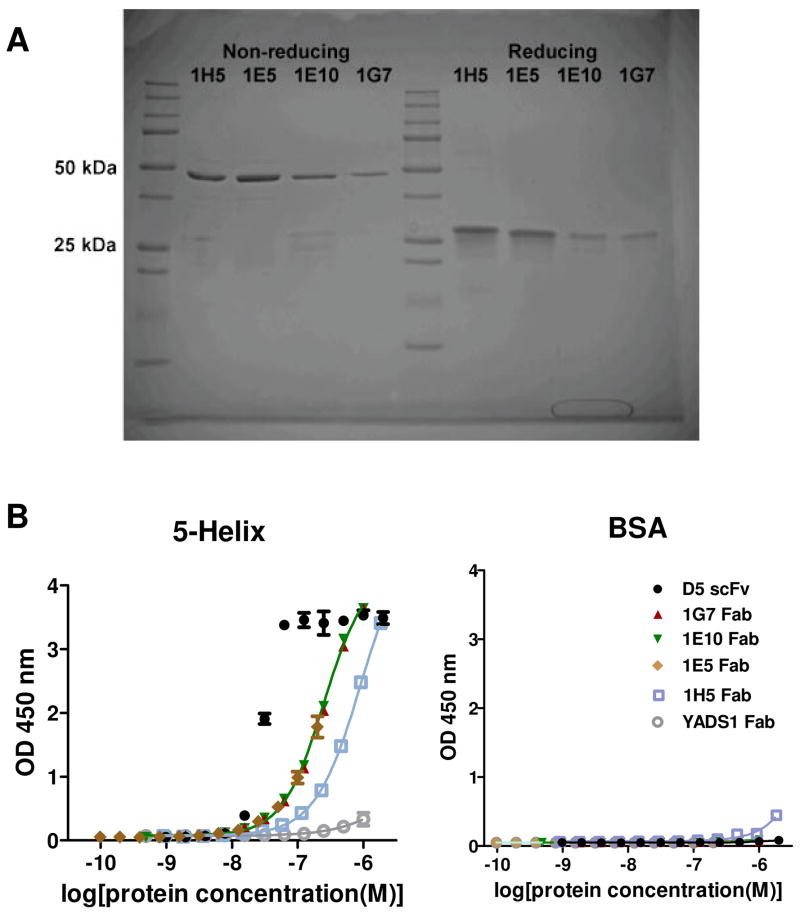

3.2 Characterization of purified Fab proteins

To confirm that off-phage binding activity was similar to on-phage behavior, the Fab proteins corresponding to several clones (1G7, 1E10, 1E5, and 1H5) were expressed in E. coli and purified. The purification results are shown in Figure 2A. In all cases, a single band of ~50 kDa was observed under non-reducing conditions; under reducing conditions, a band at ~25 kDa was observed corresponding to the separated, unresolved VL-CL and VH-CH fragments. The parental Fab (YADS1) was purified using a similar procedure for use as a control protein. We also produced the single-chain variable fragment (scFv) of the previously reported antibody D5, which is also known to bind 5-Helix [9]. All scFv and Fab proteins contained a FLAG epitope sequence that was used for detection in ELISA binding assays.

Fig. 2.

(A) SDS-PAGE analysis of purified minimalist Fabs under non-reducing and reducing conditions. (B) Reactivity of the purified D5 scFv, and Fabs 1G7, 1E10, 1E5 1H5, and YADS1 for 5-Helix and BSA.

ELISA indicated the minimalist Fabs and the D5 scFv bound 5-Helix but not BSA (Figure 1B). The D5 scFv had a half-maximal binding titer of ~ 30 nM; the binding curves for the minimalist Fabs did not reach saturation at the highest Fab concentrations. However, we estimate that the minimalist Fabs had at least 10-fold lower half-maximal binding titer than D5 scFv. The parental Fab (YADS1) showed no reactivity for 5-Helix.

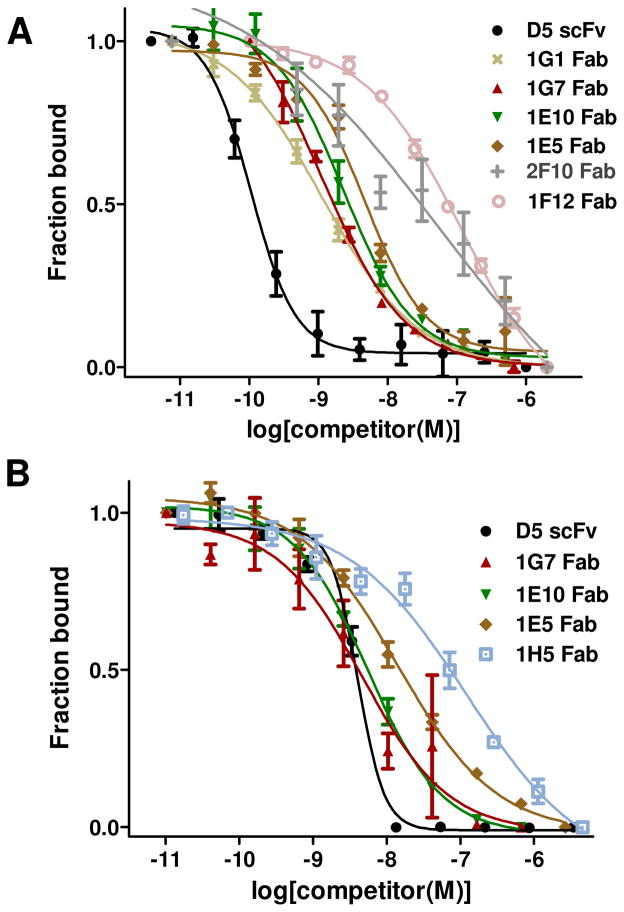

3.3 Estimation of binding affinities by competitive ELISA

To obtain estimates for affinity of several clones, we performed competitive ELISA experiments in which binding to immobilized 5-Helix was competed by free, soluble 5-Helix. Such experiments have previously been shown to provide a rough parameter to assess affinity of synthetic antibodies [25]. This analysis was performed both on-phage (bivalent format) and off-phage (monovalent) for several clones (Figure 3 and Table 1). The D5 scFv had an IC50 of 0.1 ± 0.03 nM when expressed bivalently on phage and 4.1 ± 0.3 nM as scFv protein. These results are consistent with previously reported KD measurement of D5 antibody fragments determined by surface plasmon resonance (KD = 0.15 nM for the scFv, 0.05 nM for the IgG) or isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC, KD = 20 nM for the Fab) [9, 11]. Analysis of minimalist clones obtained from our selection indicated they bound with IC50 values ranging from 1 nM – 120 nM on-phage and 2.5 – 120 nM as Fab proteins.

Fig. 3.

Competitive ELISA for binding 5-Helix for antibody fragments expressed bivalently on phage (A) or as purified protein (B).

4. Discussion

We describe the isolation and characterization of synthetic Fab fragments from a minimalist phage display library that bind specifically to 5-Helix, an antigen that consists of the N- and C-heptad repeat regions of HIV-1 gp41 [8, 20]. These results affirm the generality of the Tyr/Ser binomial randomization scheme for antibody molecular recognition [18]. Comparison of the minimalist Fabs to the D5 scFv indicates they are comparable in affinity and specificity. The critical paratope of D5 for recognition of 5-Helix involves hydrophobic residues on HCDR2 [8]. The fact that some of the minimalist Fabs contain a high content of Tyr in HCDR2 (e.g., 2F10 and 1F12) but others do not (e.g., 1B11 and 1E10) suggest that some clones may mimic the HCDR2-dominated interactions but other binding modes are also possible. Interestingly, 1E10, 1C11, and 1E9 differed from one another only in LCDR3 and HCDR1, suggesting that some convergence of recognition exists within this family of minimalist Fabs. Furthermore, the clones with the longest HCDR3 regions (2F10 and 1F12) had the lowest IC50 values. This observation suggests that highest affinity minimalist Fab-5-Helix interactions are not HCDR3 dominated. This region (HCDR3) plays a dominant role in many antibody-antigen interactions and often constitutes the major functional paratope in synthetic antibodies [26]. Therefore, minimalist libraries can provide a wide variety of solutions to protein recognition.

Antibodies directed against the NHR and CHR segments of gp41 and analogous regions of other viruses have been used in a variety of practical applications [9–11, 27, 28]. The minimalist synthetic Fabs described here exhibit high affinity and specificity for the heptad repeat segments. In addition, they can be obtained in good yields and high purity from E. coli. These characteristics make such Fabs highly attractive for use in therapeutic, research, or diagnostic applications.

Highlights.

Synthetic antibody libraries can be used to target many protein antigens.

The heptad repeat regions of HIV-1 gp41 are required for viral entry.

Synthetic antibody fragments that target the HIV-1 gp41 heptad repeat regions were identified.

Synthetic antibody fragments targeting gp41 were purified from Escherichia coli.

Synthetic antibody fragments targeting gp41 had high affinity and specificity.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, the Arnold and Mabel Young Investigators Program, and the National Institutes of Health (R01-AI090249). A.S. was supported in part by a fellowship from the UNCF/Merck Science Initiative. We thank Sachdev Sidhu (University of Toronto) for helpful discussions, and Gustavo Da Silva for assistance with the D5 scFv purification.

Abbreviations

- HIV-1

human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- NHR

N-terminal heptad repeat

- CHR

C-terminal heptad repeat

- CDR

complementarity determining region

- hVEGF

human vascular endothelial growth factor

- Fab

antigen-binding fragment

- scFv

single-chain variable fragment

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckert DM, Kim PS. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwong PD, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet RW, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA. Structure of an HIV gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing human antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen B, Vogan EM, Gong H, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Harrison SC. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature. 2005;433:834–841. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kilby JM, Hopkins S, Venetta TM, DiMassimo B, Cloud GA, Lee JY, Alldredge L, Hunter E, Lambert D, Bolognesi D, Matthews T, Johnson MR, Nowak MA, Shaw GM, Saag MS. Potent suppression of HIV-1 replication in humans by T-20, a peptide inhibitor of gp41-mediated virus entry. Nat Med. 1998;4:1302–1307. doi: 10.1038/3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Root MJ, Kay MS, Kim PS. Protein design of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Science. 2001;291:884–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1057453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luftig MA, Mattu M, Di Giovine P, Geleziunas R, Hrin R, Barbato G, Bianchi E, Miller MD, Pessi A, Carfí A. Structural basis for HIV-1 neutralization by a pg41 fusion intermediate-directed antibody. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:740–747. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabin C, Corti D, Buzon V, Seaman MS, Lutje Hulsik D, Hinz A, Vanzetta F, Agatic G, Silacci C, Mainetti L, Scarlatti G, Sallusto F, Weiss R, Lanzavecchia A, Weissenhorn W. Crystal structure and size-dependent neutralization properties of HK20, a human monoclonal antibody binding to the highly conserved heptad repeat 1 of gp41. PLoS Pathog. 2010;18:e101195. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gustchina E, Li M, Louis JM, Anderson DE, Lloyd J, Frisch C, Bewley CA, Gustchina A, Wlodawer A, Clore GM. Structural basis of HIV-1 neutralization by affinity matured Fabs directed against the internal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001182. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koide S, Sidhu SS. The importance of being tyrosine: lessons in molecular recognition from minimalist synthetic binding proteins. ACS Chem Biol. 2009;15:325–334. doi: 10.1021/cb800314v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fellouse FA, Sidhu SS. Synthetic therapeutic antibodies. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:682–688. doi: 10.1038/nchembio843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bostrom J, Yu SF, Kan D, Appleton BA, Lee CV, Billeci K, Man W, Peale F, Ross S, Wiesmann C, Fuh G. Variants of the antibody herceptin that interact with HER2 and VEGF at the antigen binding site. Science. 2009;323:1610–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.1165480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rizk SS, Paduch M, Heithaus JH, Duguid EM, Sandstrom A, Kossiakoff AA. Allosteric control of ligand-binding affinity using engineered conformation-specific effector proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:437–442. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cobaugh CW, Almagro JC, Pogson M, Iverson B, Georgiou G. Synthetic antibody libraries focused towards peptide ligands. J Mol Biol. 2008;378:14 622–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birtalan S, Fisher RD, Sidhu SS. The functional capacity of the natural amino acids for molecular recognition. Mol BioSyst. 2010;6:1186–1194. doi: 10.1039/b927393j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fellouse FA, Li B, Compaan DM, Peden AA, Hymowitz SG, Sidhu SS. Molecular recognition by a binary code. J Mol Biol. 2005;348:1153–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koide A, Gilbreth RN, Esaki K, Tereshko V, Koide S. High-affinity single-domain binding proteins with a binary-code interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6632–6637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700149104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frey G, Rits-Volloch S, Zhang XQ, Schooley RT, Chen B, Harrison SC. Small molecules that bind the inner core of gp41 and inhibit HIV envelope-mediated fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13938–13943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601036103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Da Silva GF, Harrison JS, Lai JR. Contribution of light chain residues to high affinity binding in an HIV-1 antibody explored by combinatorial scanning mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5464–6472. doi: 10.1021/bi100293q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee CV, Sidhu SS, Fuh G. Bivalent antibody phage display mimics natural immunoglobulin. J Immunol Methods. 2004;284:119–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fellouse FA, Wiesmann C, Sidhu SS. Synthetic antibodies from a four-amino-acid code: a dominant role for tyrosine in antigen recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12467–12472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401786101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeLano WL, Cunningham BC. Rapid Screening of Phage Displayed Protein Binding Affinities by Phage ELISA. In: Clackson T, Lowman HB, editors. Phage Display: A Practical Approach. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fellouse FA, Esaki K, Birtalan S, Raptis D, Cancasci VJ, Koide A, Jhurani P, Vasser M, Wiesmann C, Kossiakoff AA, Koide S, Sidhu SS. High-throughput generation of synthetic antibodies from highly functional minimalist phage-displayed libraries. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:924–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Birtalan S, Zhang Y, Fellouse FA, Shao L, Schaefer G, Sidhu SS. The intrinsic contributions of tyrosine, serine, glycine and arginine to the affinity and specificity of antibodies. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:1518–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S, Boyer-Chatenet L, Lu H, Jiang S. Rapid and automated fluorescence-linked immunosorbent assay for high-throughput screening of HIV-1 fusion inhibitors targeting gp41. J Biomol Screen. 2003;8:685–693. doi: 10.1177/1087057103259155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Frey G, Chen J, Rits-Volloch S, Freeman MM, Zolla-Pazner S, Chen B. Distinct conformational states of HIV-1 gp41 are recognized by neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1486–1491. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]