Abstract

Recent advances in pluripotent stem cell research have provided investigators with potent sources of cardiogenic cells. However, tissue engineering methodologies to assemble cardiac progenitors into aligned, 3-dimensional (3D) myocardial tissues capable of physiologically relevant electrical conduction and force generation are lacking. In this study, we introduced 3D cell alignment cues in a fibrin-based hydrogel matrix to engineer highly functional cardiac tissues from genetically purified mouse embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes (CMs) and cardiovascular progenitors (CVPs). Procedures for CM and CVP derivation, purification, and functional differentiation in monolayer cultures were first optimized to yield robust intercellular coupling and maximize velocity of action potential propagation. A versatile soft-lithography technique was then applied to reproducibly fabricate engineered cardiac tissues with controllable size and 3D architecture. While purified CMs assembled into a functional 3D syncytium only when supplemented with supporting non-myocytes, purified CVPs differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle, and endothelial cells, and autonomously supported the formation of functional cardiac tissues. After a total culture time similar to period of mouse embryonic development (21 days), the engineered cardiac tissues exhibited unprecedented levels of 3D organization and functional differentiation characteristic of native neonatal myocardium, including: 1) dense, uniformly aligned, highly differentiated and electromechanically coupled cardiomyocytes, 2) rapid action potential conduction with velocities between 22 and 25 cm/s, and 3) significant contractile forces of up to 2 mN. These results represent an important advancement in stem cell-based cardiac tissue engineering and provide the foundation for exploiting the exciting progress in pluripotent stem cell research in the future tissue engineering therapies for heart disease.

Keywords: Stem cell, Cardiac tissue engineering, Fibrin, Hydrogel, Contractile function, Optical mapping

1. Introduction

During myocardial infarction, large numbers of cardiomyocytes are lost and replaced by a non-contractile scar tissue. An increased load on the remaining heart muscle yields cardiac structural remodeling and a gradual decline in functional output, ultimately leading to congestive heart failure and death [1]. Given the chronic shortage of heart donors, tissue engineering [2] seeks to assemble in vitro a functional cardiac tissue "patch" that would integrate with and reinforce the damaged myocardium, thereby preventing or reversing the progression of post-infarction disease [3, 4]. Currently, the large quantities of functional cardiomyocytes needed for tissue engineering therapies can only be derived from pluripotent (embryonic or induced) stem cells [5–7].

In recent studies, pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes were supplemented with other cell types (e.g., mouse embryonic fibroblasts, human mesenchymal and endothelial cells) to generate synchronously contracting, 3-dimensional (3D) cardiac-like tissues [8–12]. While these studies showed an improvement in cardiomyocyte proliferation and survival in the presence of supporting non-cardiac cells, no rigorous tests have been performed to assess electromechanical function in these stem cell-derived cardiac tissues. In lieu of direct measurements of electrophysiological and contractile function, synchronous contractile activity of cardiomyocytes in engineered cardiac tissues has been frequently used as a single measure of cardiac tissue functionality [10, 11]. However, it is well established that normal electrical conduction requires 2–3 orders of magnitude stronger intercellular coupling than mere cell synchronization [13, 14]. Thus, the actual functionality of engineered cardiac tissues should be carefully assessed by measuring two important parameters: 1) the macroscopic speed at which interconnected cardiomyocytes propagate electrical activity and 2) the amplitude of contractile force generated during electrical propagation via the process of excitation-contraction coupling. Fast anisotropic electrical propagation and strong contraction of engineered cardiac tissues are essential for eliminating the risks of cardiac arrhythmias after implantation, and for enhanced therapeutic effect through coordinated contraction with host myocardial tissue [15, 16].

While hydrogel scaffolds based on type I collagen have been traditionally used for cardiac tissue engineering [8, 12, 17–20], others [21–23] and us [24] have utilized fibrin-based hydrogels due to their proven biocompatibility and unique biomechanical properties. Specifically, similar to native heart tissue [25], fibrin hydrogels exhibit strain-stiffening behavior [26, 27] and at the same time, they remain more compliant than other biopolymers [28] under low-strain conditions, allowing a higher degree of gel compaction and remodeling to take place. In this study, our goal was to develop a cardiac tissue engineering approach that would provide the basis for future application of pluripotent stem cells in tissue engineering therapies for myocardial infarction, Specifically, by incorporating 3D cell alignment cues into fibrin-based hydrogels using our previously developed photolithographic micro-molding technique [24], we aimed to create highly functional, anisotropic cardiac tissue patches with customizable size, geometry, and cell alignment. Immunostaining, RT-PCR, optical mapping of action potentials and calcium transients, and isometric measurements of contractile force were used to systematically assess levels of differentiation and electrical and mechanical function in these engineered cardiac tissues.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Derivation of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cell (mESC) Lines

To derive mESC lines capable of generating pure population of cardiomyocytes (mESC-CMs), D3 mESCs (ATCC CRL-11632) were co-transfected by electroporation (Amaxa, A023) with two vectors. The first vector allowed constitutive expression of G418 resistance under SV40 promoter and puromycin N-acetyl-transferase (Invivogen, pORF39-PAC) expression under a 5.5Kb mouse Myh6 promoter, which was a kind gift from Dr. Jeffrey Robbins [29]. The second vector allowed red fluorescence protein (pDsRed2-1, Clontech) expression under the same Myh6 promoter. Similar to the derivation of mESC-CM lines, mESC-derived cardiovascular progenitor (mESC-CVP) lines were obtained by stable transfection of D3 mESCs with three vectors. The first two vectors allowed expression of either puromycin N-acetyl-transferase or enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) under a 2.3kb Nkx2-5 enhancer element[30, 31] in series with the mouse Hsp68 minimal promoter. The Nkx2-5 enhancer element was a kind gift from Dr. Eric N. Olson [30]. The third vector allowed the hygromycin phosphotransferase expression under mouse polII promoter, which allowed the selection of clonal colonies on hygromycin-resistant feeder layers using hygromycin.

2.2 Fabrication of Cardiac Tissue Patches

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Dow Corning) molds with hexagonal posts were microfabricated as previously described [24]. Hydrogel solution (Supplementary Table 1) was mixed with mESC-CMs or mESC-CVPs to a final concentration of 6.5·106 cells/ml and pipetted into each PDMS mold (120 µL of cell/gel mix for 7×7 mm2 and 500 µL for 14×14 mm2 patch, respectively). Cell/gel solution was left to polymerize for one hour at 37°C and resulting tissue patches were maintained in serum-free N2B27 media (Supplementary Table 1) for 2–3 weeks. Media was changed daily. For the co-culture patch experiments, primary neonatal rat ventricular fibroblasts were obtained using standard protocols [32], grown to confluence (7–9 days) in T-75 flasks (Falcon), dissociated in 0.05% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco), and added to mESC-CMs at 3%, 6% or 12% of the mESC-CM number. Resulting cell mixtures were used for the fabrication of tissue patches as described.

2.3 Assessment of Electrical Propagation

Optical mapping of cell membrane potentials and calcium transients was performed using our established methods [32, 33]. Two-five seconds of activity were recorded in macroscopic (whole tissue) or microscopic (using a 4X objective of Nikon microscope) mode using a 504-channel photodiode array (RedShirt Imaging) or a fast EMCCD camera (iXonEM+, Andor). Data analysis was performed using custom MATLAB software [32].

2.4 Assessment of Contractile Force

Generation of isometric contractile force in tissue patches was assessed in 35°C serum-free media using a custom-made apparatus with an ultra-sensitive optical force transducer and a computer-controlled linear actuator, as previously described [33].

2.5 Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. For single comparisons, one-tailed Student’s t-tests were used at α = 0.05. For multiple comparisons, data were analyzed using ANOVA followed by Student-Newman-Keuls analysis with unequal N and disparate variances.

Additional details and methodologies are described in the Supplemental Information.

3. Results

3.1 Electrophysiological Properties of mESC-CM Monolayers

To generate the large numbers of cardiomyocytes required for cardiac tissue patch fabrication and testing (Supplementary Fig. 1), we stably transfected undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells to drive the expression of puromycin aminotransferase and red fluorescent protein (dsRed2-1) under the control of the mouse Myh6 (α-myosin heavy chain, α-MHC) promoter. This system allowed us to derive mESC-CMs with high purity, as previously reported [34] (Supplementary Video 1). Specifically, mESC-CMs were isolated from suspension cultures of 13 day old differentiating embryoid bodies (EBs) after 5 days of puromycin selection. Cells were cultured as 20 mm diameter confluent monolayers in a defined, serum-free medium (Supplementary Table 1). After 1–2 weeks of culture, the mESC-CMs exhibited a cross-striated phenotype and robust intercellular expression of connexin-43 gap junctions and various coupling proteins (Fig. 1A,B, Supplementary Fig. 2A–C) known to support normal electrical and mechanical communication in the adult heart [35].

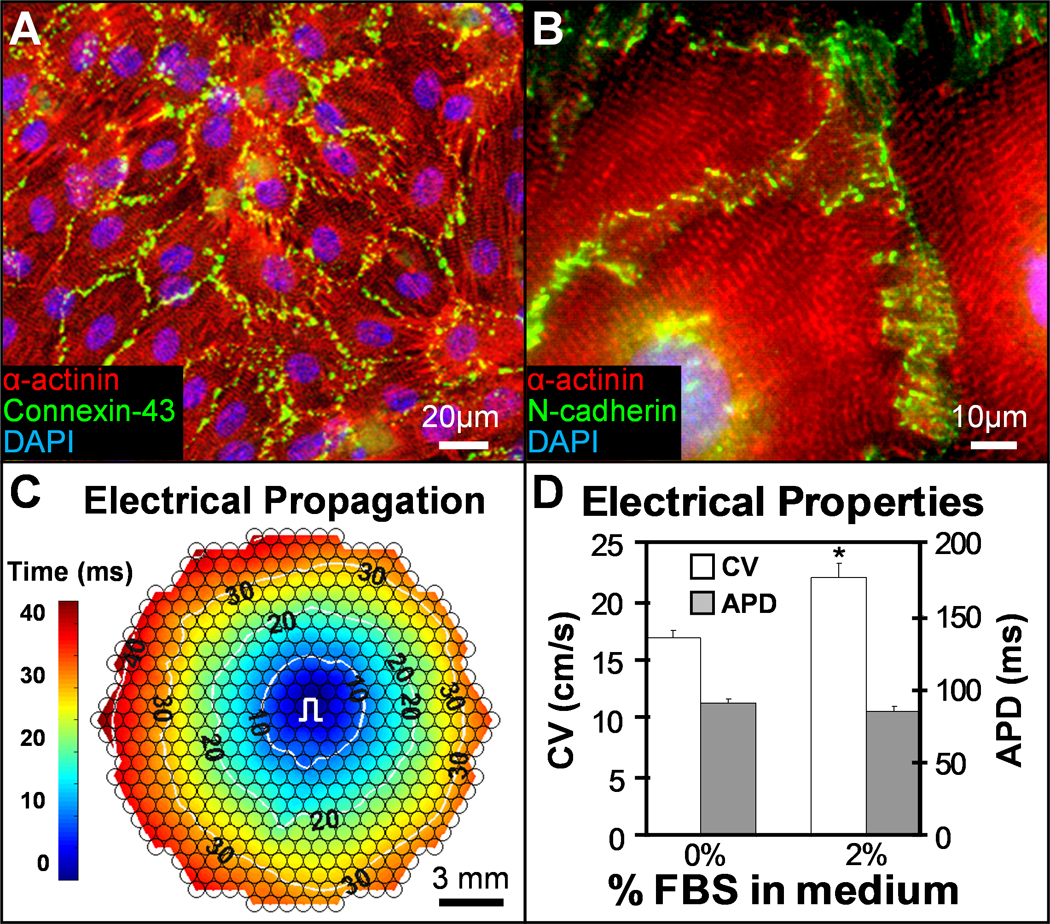

Figure 1.

mESC-CMs form highly functional 2D monolayers. A–B, Under optimized conditions, pure mESC-CMs in 1–2 week old confluent monolayers exhibit well-defined sarcomeric structure and robust intercellular coupling via electrical (A) and mechanical (B) junctions. C, Point pacing (pulse sign) in mESC-CM monolayers elicits rapid and uniform action potential spread (see also Supplementary movie 2). Small circles denote 504 recording sites. Isochrones of cell activation (white circles) are labeled in milliseconds. d. Addition of 2% serum in culture media improves conduction velocity (CV) without affecting action potential duration (APD). *P < 0.05, one-tailed Student’s t-test; n = 6.

When locally stimulated by a point electrode, mESC-CMs responded with uniform action potential propagation across the entire monolayer (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Video 2) at velocities that varied with serum concentration used for EB differentiation and for monolayer culture (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Fig. 2D). Under optimized culture conditions (20% and 2% FBS for EB differentiation and monolayers, respectively), the conduction velocity (CV) and action potential duration at 80% repolarization (APD) in mESC-CM monolayers were 22 ± 1.2 cm/s and 84.4 ± 3.4 ms, respectively. These CV values are significantly higher than previously reported for mouse or human ESC-CMs (1–6 cm/s [11, 36–40]) and similar to values measured in intact neonatal rat [41] and mouse ventricles [42, 43] as well as monolayer cultures of primary neonatal rat ventricular cells (NRVCs) [32, 44]. These neonatal levels of electrical maturity in mESC-CMs were achieved in vitro after a total of 21–28 days, a period comparable to that of mouse embryonic development. As expected, functional differentiation of mESC-CMs was accompanied with a robust, time-dependent activation of cardiac functional genes (Supplementary Fig. 3).

3.2 Tissue Patches made of pure mESC-CMs

Using this optimized cell differentiation protocol and our recently developed methodology for creating PDMS tissue molds [24], we fabricated 7×7 and 14×14 mm2 porous cardiac patches made of mESC-CMs (Supplementary Fig. 4). After 3 weeks of culture, mESC-CMs in patches survived, but failed to compact the surrounding fibrin hydrogel matrix and undergo spreading and alignment (Fig. 2A). Instead, although being cross-striated and coupled by connexin-43 gap junctions, the cells remained rounded and formed isolated clusters (Fig. 2B), and only occasionally aligned against the hydrogel boundary (Fig. 2C). The rounded cardiomyocytes in the patches exhibited locally, but not macroscopically, synchronized spontaneous contractions at rates of 1–2 Hz. When electrically stimulated, they failed to conduct action potentials, and only produced small contractile force amplitudes (< 100 µN) when simulated by a strong electric field shock (not shown).

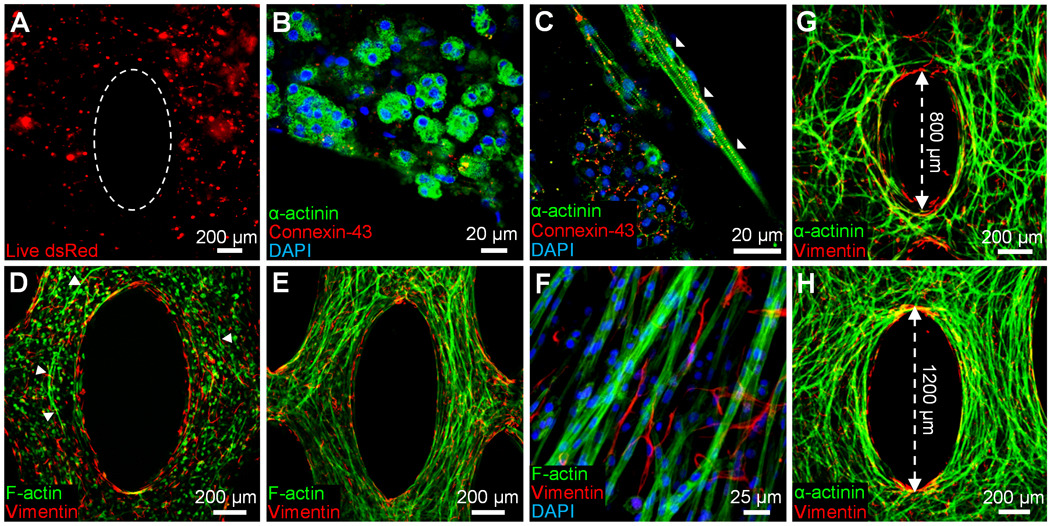

Figure 2.

mESC-CMs in 3D cardiac patches spread and interconnect only in the presence of fibroblasts. A, Pure mESC-CMs in 14 day old tissue patches appear round and clustered. Dotted ellipse delineates the pore boundary created by the PDMS mold. B, mESC-CM clusters contain rounded, cross-striated cardiomyocytes (green) interconnected with connexin-43 gap junctions (red). C, Aligned cells are occasionally found only at the gel boundary (white arrowheads). D, In the presence of neonatal rat ventricular fibroblasts (red), mESC-CMs (green) start spreading (white arrowheads) by culture day 7. E, At day 14, mESC-CMs in co-cultured patches are extensively aligned. F, Fibroblasts around formed cardiac bundles show no preferential alignment. G,H, Degree of local cell alignment can be controlled by varying the length of microfabricated posts.

3.3 Tissue Patches made of mESC-CMs and Cardiac Fibroblasts

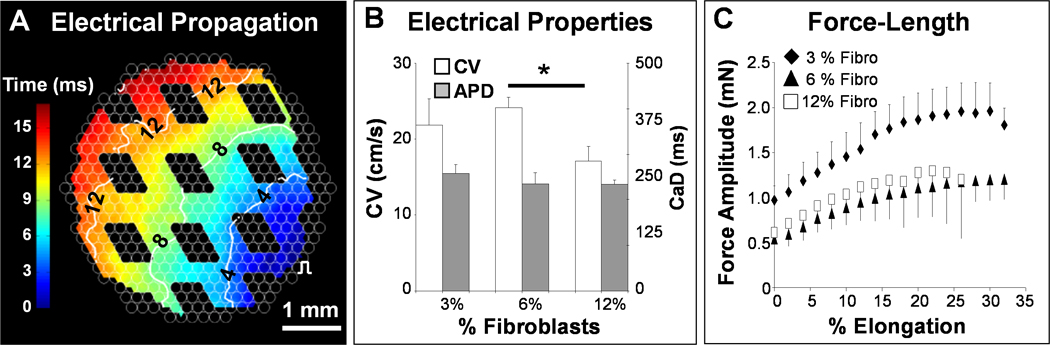

We hypothesized that the pure mESC-CMs (unlike cultured NRVCs [24] that contain a fraction of non-myocytes [32]) failed to form a functional 3D syncytium due to their inability to significantly compact and mechanically remodel surrounding hydrogel matrix. Based on the measured non-myocyte (predominantly fibroblast) fraction in cultured NRVCs [32], we co-encapsulated mESC-CMs with a small number of neonatal rat ventricular fibroblasts (3%, 6% or 12% of mESC-CMs). We expected that this small fibroblast fraction would allow compaction and remodeling of the fibrin hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. 5) without significantly impeding 3D electrical conduction of mESC-CMs [41]. With time of culture, the mESC-CM/fibroblast patches significantly compacted (Supplementary Fig. 5D), and the mESC-CMs in the presence of fibroblasts elongated, co-aligned, interconnected throughout the patch volume (Fig. 2D–F), and generated macroscopically synchronous contractions (Supplementary Video 3). Unlike mESC-CMs, neonatal rat ventricular fibroblasts, exhibited predominantly random orientations within the co-cultured (Fig. 2F) or mono-cultured (Supplementary Fig. 5A2–C2) patch. The degree of cardiomyocyte alignment within the co-cultured patch could be controlled by varying the length of the microfabricated tissue pores (Fig. 2G,H) [24, 45]. When electrically stimulated (Supplementary Fig. 6), the 14 day old, 7×7 and 14×14 mm2 mESC-CM/fibroblast patches supported fast, micro- and macroscopically uniform action potential propagation (Fig. 3A and Supplementary Video 4) with velocities that ranged between 17.8 ± 1.9 cm/s (12% fibroblasts) and 24.1 ± 1.4 cm/s (6% fibroblasts). The patches exhibited average Ca2+ transient durations of 243 ± 10 ms (Fig. 3B) and could be steadily captured by electrical stimulation at maximum rates that ranged between 4.3 ± 0.3 Hz (3% fibroblasts) and 5.7±0.3 Hz (6% fibroblasts). We further tested (Supplementary Fig. 7A) if the fast action potential propagation and the 3D aligned, cardiac-like tissue structure of mESC-CM/fibroblast patches would enable generation of significant contractile forces. All patches exhibited a positive force-length (Fig. 3F) and a negative isometric force-frequency relationship (Supplementary Fig. 7B,C), consistent with previously published observations of engineered neonatal rat cardiac tissues [46]. The amplitudes of contractile force in 7×7 mm2 patches ranged between 1.20 ± 0.40 mN (12% fibroblasts) and 1.96 ± 0.54 mN (3% fibroblasts), which is an order of magnitude higher than previously reported for mouse [8] and human [12] ESC-derived cardiac bundles.

Figure 3.

Co-cultured mESC-CM+fibroblast patches exhibit advanced electrical and mechanical function. A, Optical mapping revealed that co-cultured tissue patches supported fast and uniform action potential propagation (see also Supplementary movie 4). The void spaces in the isochrone map correspond to tissue pores. B, Conduction velocity (CV) and calcium transient duration (CaD) as a function of the initial fraction of fibroblasts (e.g., CV = 241 ± 16 mm/s for 6% fibroblasts). CV of 6% and 12% fibroblast conditions differed significantly. *P < 0.05, one-tailed Student’s t-test assuming unequal variances, n = 3. C, Co-culture tissue patches exhibited rising force-length relationships reminiscent of the Frank-Starling law in whole hearts. Percent elongation is shown relative to tissue length during culture (7 mm).

3.4 Electrophysiological Properties of mESC-CVP Monolayers

Since the presence of a small amount of cardiac non-myocytes in the tissue patch enabled dramatic reorganization of mESC-CMs into a functional 3D syncytium, we further hypothesized that a tri-potent cardiovascular progenitor (mESC-CVP) population [31], capable of differentiating into not only cardiomyocytes but also smooth muscle and endothelial cells (Supplementary Fig. 8), could be used as a sole mESC-derived source for the formation of a functional 3D patch. To efficiently obtain large quantities of pure mESC-CVPs, we derived a mESC clone stably expressing puromycin aminotransferase and eGFP under the control of a cardiac-specific Nkx2.5 enhancer element [31].

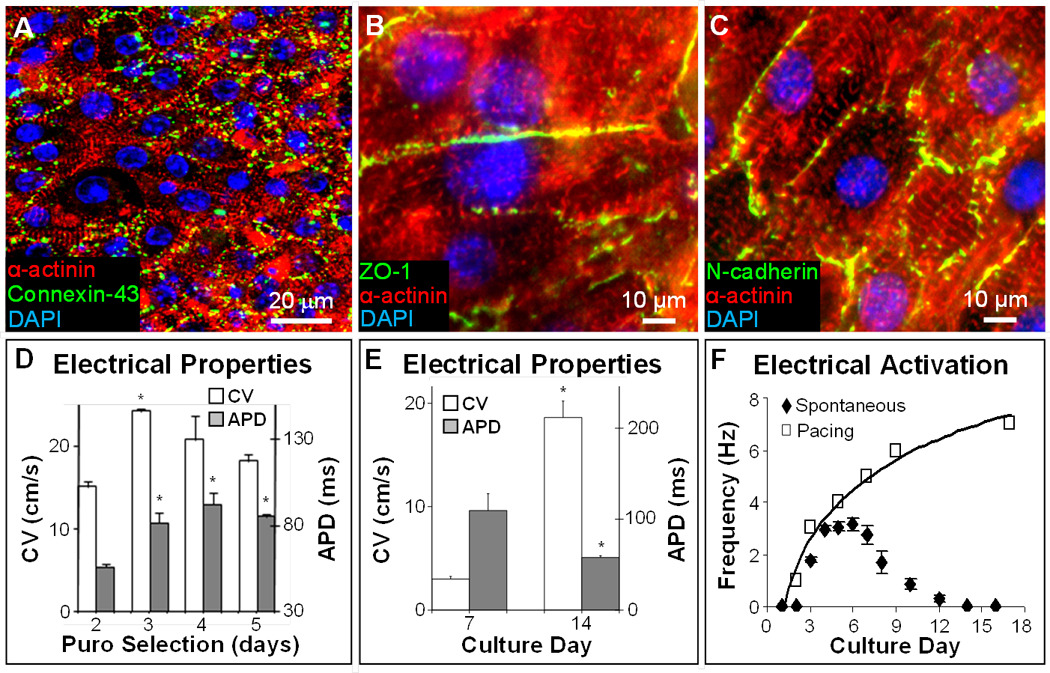

Under optimized culture conditions, mESC-CVPs in confluent monolayers predominantly differentiated into cross-striated cardiomyocytes that robustly expressed electrical and mechanical coupling proteins (Fig. 4A–C). For optimum puromycin selection of 3 days (Fig. 4D), mESC-CVP monolayers exhibited an increase in CV and decrease in APD with time of culture (Fig. 4E), and after 14 days exhibited conduction properties comparable to those of pure mESC-CM monolayers (Fig. 1D). Simultaneously, the rate of spontaneous activity in mESC-CVP monolayers increased to 2.72 ± 0.20 Hz by culture day 5, followed by a gradual decrease to 0 Hz (no activity) by day 14 (Fig. 4F), while the maximum rate of cell capture by electrical pacing steadily increased to 7 Hz by culture day 16. The observed trends in macroscopic electrical properties (i.e., CV increase, APD decrease, and spontaneous rate cessation) suggested that mESC-CVP monolayers initially resembled early embryonic cardiac tissue, but with time of culture, significantly matured to acquire a functional phenotype of working neonatal muscle [47].

Figure 4.

mESC-CVP monolayers exhibit robust electromechanical coupling and fast electrical propagation. A–C, After 7–14 days of culture, confluent mESC-CVP monolayers contain cross-striated cardiomyocytes that robustly express connexin-43 (A), zona occludens 1 (B), and N-cadherin (C). D, Electrophysiological parameters in 14-day old monolayers made using mESC-CVPs purified by selection with 5µg/ml puromycin (puro). The three-day puromycin selection yielded optimum conduction velocities (CV = 242 ± 4 mm/s) and was used in all further studies. *P < 0.05 relative to corresponding parameters for 2-day puromycin selection; ANOVA with Student-Newman-Keuls, n = 3–6. E–F, Functional cardiac differentiation of mESC-CVPs with time in culture was associated with increased CV and decreased APD (E), as well as decreased spontaneous beating rate (closed diamonds) and increased maximum rate of electrical pacing (open squares) yielding steady 1:1 capture (F). *P < 0.05 relative to day 7; one-tailed Student’s t-test, n = 3–5.

3.5 Tissue Patches made of mESC-CVPs

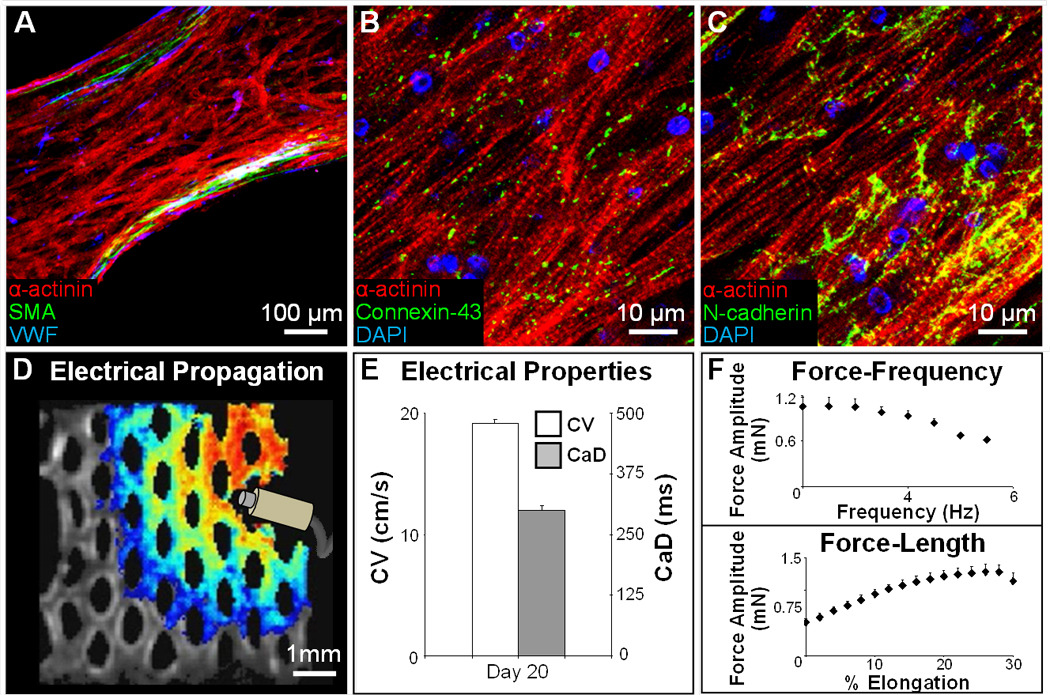

We then applied the same tissue engineering strategy and hydrogel formulation to fabricate 3D cardiac tissue patches using only the mESC-CVP cell source. In contrast to pure mESC-CMs that remained rounded in the 3D culture (Fig. 2A,B), the cardiomyocytes that differentiated from mESC-CVPs spread, aligned, and interconnected throughout the entire hydrogel volume (Fig. 5A–C). Small amounts of endothelial and smooth muscle cells that differentiated from mESC-CVPs were found interspersed between the cardiomyocytes and concentrated near the free gel boundaries (Fig. 5A). After 14 days in culture, the mESC-CVP patches supported continuous and uniform action potential conduction (Fig. 5D and Supplementary video 5) with velocities of 19.2 ± 0.4 cm/s and Ca2+ transient durations of 300 ± 10 ms (Fig. 5E), comparable to values measured in mESC-CM/fibroblast patches (Fig. 3B). The mESC-CVP patches also exhibited a negative force-frequency and positive force-length relationship with maximum contractile forces of 1.28 ± 0.11 mN (Fig. 5F). These electrical and mechanical measurements demonstrated that highly functional 3D cardiac tissues can be generated in vitro from mESC-CVPs alone, without the need for additional cell types and suggest that cardiovascular progenitors rather than pure cardiomyocytes may be the optimal stem cell-derived source for functional cardiac tissue engineering.

Figure 5.

mESC-CVPs can autonomously form a functional 3D cardiac patch. A, Three-week old tissue patch with aligned cardiomyocytes (red), and dispersed endothelial (blue) and smooth muscle (green) cells. SMA; smooth muscle actin. VWF; Von Willebrand factor. B–C, mESC-CVP derived cardiomyocytes in tissue patches are cross-striated and robustly coupled via electrical (B) and mechanical (C) junctions. D, A snapshot of a uniformly propagating action potential (see Supplementary movie 5) induced by a point electrode. E–F, After 3 weeks in culture, mESC-CVP patches exhibit high CVs (E), significant contractile forces, and physiological force-frequency and force-length relationships (F). Mean ± s.e.m; n=3.

4. Discussion

In this study we describe the bioengineering of large, aligned, and highly functional cardiac tissue patches starting from pluripotent stem cells. Our tissue-engineering approach employs efficient methods to generate and differentiate large amounts of genetically purified cardiomyocytes (mESC-CMs) and cardiovascular progenitors (mESC-CVPs) followed by a mesoscopic hydrogel molding technique to assemble and further differentiate these cells into a highly functional 3D cardiac syncytium. After a total culture time of 3–4 weeks, advanced levels of tissue organization and function are evident from the robust expression of electrical and mechanical junctions in aligned, cross-striated cardiomyoctyes, along with the achieved values for macroscopic conduction velocity and contractile force amplitude of up to 25 cm/s and 2 mN, respectively. Overall, through a careful optimization procedure (involving 2D and 3D cell culture) and rigorous functional tests, this study for the first time demonstrates that: 1) it is possible to reproducibly obtain large, anisotropic 3D cardiac tissue patches starting from pluripotent stem cells, 2) this result can be accomplished using only a single cardiovascular progenitor cell source (rather than combining cells of multiple types, ages, or species), and 3) in vitro conditions can be optimized to recapitulate important aspects of embryonic cardiac development and after 21 days of culture (equivalent to mouse gestation period) obtain levels of structural and functional differentiation similar to those of neonatal mouse heart. In addition, our results signify the supporting role that non-myocytes play in the assembly of 3D functional cardiac tissues and emphasize the use of 3D, rather than 2D, cell culture environment as a requisite setting for systematic studies of cardiac tissue formation in vitro.

Current in vitro cardiac tissue engineering approaches involve encapsulation of cells within porous polymer scaffolds [9, 41, 48], natural hydrogels [3, 11, 12], or decellularized tissues [49], or rely on self-assembly of cells into scaffold-free sheets [50], bundles [51], or aggregates [10]. Despite significant progress, the field is still hampered by the lack of methods to fabricate large, thick and dense cardiac tissues with uniformly aligned cells that support anisotropic electrical and mechanical function. While honeycomb-shaped compartmentalized scaffolds have been recently used to introduce mechanical anisotropy in engineered cardiac tissues, the cells within different compartments of the scaffold remained electrically insulated and unable to support macroscopic electrical conduction [48]. We previously employed aligned polymer scaffolds to enable both macroscopic 3D cell alignment and anisotropic electrical conduction, but rigidity of the scaffold prevented visible tissue contractions [52]. In our current work, introduction of elliptical pores in tissue patches enhanced diffusion of oxygen and nutrients to the cells and enabled 3D cell alignment, while the use of hydrogel scaffold permitted vigorous patch contractions. By fabricating PDMS molds with different dimensions, patch thickness, geometry, and the degree and direction of local cell alignment can be precisely and independently varied, which in turn will determine levels of micro- and macroscopic functional anisotropy [53]. Furthermore, this computer-assisted methodology can be combined with digital imaging techniques, such as diffusion tensor MRI, to fabricate 3D tissues with realistic cell orientations (e.g. mimicking cardiac fiber directions on epicardial surface [53]). By applying similar strategy, we have previously micropatterned 2D cardiac monolayers that replicate microanatomy of murine ventricular cross-sections [54].

Importantly, the described tissue engineering approach results in levels of electrical and mechanical function that significantly surpass those previously reported for mouse or human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes and cardiac tissues [8, 11, 12, 36–40]. Moreover, even though our initial cell source consisted of undifferentiated mESCs, the obtained functional properties are comparable to those of engineered 2D monolayers [32, 55, 56] and 3D tissues [3, 41, 49, 52] made starting from considerably more mature neonatal rat ventricular cells. We believe that these significant results reflect our careful optimization strategy where serum type and concentration during embryoid body differentiation, the onset and duration of antibiotic selection, and media formulation during subsequent cell culture were each individually varied to maximize an important tissue-scale functional parameter, conduction velocity. In addition, efficient derivation of highly purified cardiogenic cells through puromycin selection further contributed success of our approach.

Our experiments with the two distinct cardiogenic cell populations revealed that relatively small numbers of non-cardiomyocytes can play a critical role in the in vitro formation of 3D functional cardiac tissues. Similarly, studies of others have shown beneficial effects of stromal cells on the survival, spreading, and functional maturation of neonatal rat and ESC-derived cardiomyocytes [9, 10, 12, 57–60]. The mechanisms of cardiomyocyte/non-myocyte interactions in the context of cardiac development and tissue engineering remain unknown and are likely to depend on non-myocyte type [9, 10, 12], age [61] and number [41] and involve different cell contact, paracrine, and extracellular matrix mediated effects. Importantly, our studies show that contrary to 3D culture, pure mESC-CMs in 2D culture can spread, interconnect, and generate highly functional monolayers without any apparent need for non-cardiomyocytes. Furthermore, non-cardiomyocytes may even appear to only disrupt cardiac function by blocking electrical conduction if the cardiac function is studied in pseudo-1D micropatterned cell strands [62]. Therefore, the 3D cell culture environment appears as the only valid and relevant setting for studies of functional cardiogenesis in vitro.

While this study suggests puromycin-selected Nkx2-5+ progenitors as the optimal source for cardiac tissue engineering, it is unknown if other cardiogenic cell sources, derived from pluripotent stem cells either by genetic selection [7, 63] or directed differentiation [5, 6], could yield engineered tissues with enhanced function compared to that of mESC-CVPs. Use of biophysical [3, 12, 64] and biochemical [65] stimulation, as well as longer time of culture, may further advance structural and functional phenotype of our engineered tissues toward that of adult myocardium. While microfabrication of elliptical pores in our study enabled generation of relatively thick cardiac tissues (~300 µm vs. ~80–100 µm for non-porous patch [41, 66]), this and other approaches are still limited by inability to fabricate perfusable vasculature within the engineered tissue. The presence of tissue pores and precise control of pore dimensions, combined with stacking of multiple patches [3, 66], could allow extension of our approach to engineering a relatively thick cardiac tissue with enhanced capacity for vascularization and survival after implantation.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we have shown successful engineering of stem cell-derived cardiac tissue patches with controllable anisotropic structure and unprecedented levels of electrical and mechanical function brought about by robust cardiomyocyte alignment, differentiation, and electromechanical coupling. Furthermore, our studies demonstrate requisite roles for stromal cells in the formation of 3D, but not 2D, functional cardiac tissues and suggest tri-potent Nkx2-5+ progenitors as a superior autonomous cell source for functional cardiac tissue engineering due to their ability to generate both cardiomyocytes and vascular cells. We believe that this result represents an important step towards future bioengineering of cardiac tissues with levels of functional differentiation that will eventually ensure safe and efficient cardiac therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank N. Badie for assistance with optical mapping and data analysis, and W. Bian for assistance with force measurements. This work was supported by NIH grants HL104326, HL095069, and HL080469 to N.B., a fellowship from the A*STAR (Singapore) to B.L., and the FAMRI Young Clinical Scientist award to N.C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pfeffer MA, Braunwald E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction. Experimental observations and clinical implications. Circulation. 1990;81:1161–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.4.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–926. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmermann WH, Melnychenko I, Wasmeier G, Didie M, Naito H, Nixdorff U, et al. Engineered heart tissue grafts improve systolic and diastolic function in infarcted rat hearts. Nat Med. 2006;12:452–458. doi: 10.1038/nm1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chien KR, Domian IJ, Parker KK. Cardiogenesis and the complex biology of regenerative cardiovascular medicine. Science (New York, NY. 2008;322:1494–1497. doi: 10.1126/science.1163267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, et al. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015–1024. doi: 10.1038/nbt1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L, Soonpaa MH, Adler ED, Roepke TK, Kattman SJ, Kennedy M, et al. Human cardiovascular progenitor cells develop from a KDR+ embryonic-stem-cell-derived population. Nature. 2008;453:524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature06894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller M, Fleischmann BK, Selbert S, Ji GJ, Endl E, Middeler G, et al. Selection of ventricular-like cardiomyocytes from ES cells in vitro. FASEB J. 2000;14:2540–2548. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0002com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo XM, Zhao YS, Chang HX, Wang CY, E LL, Zhang XA, et al. Creation of engineered cardiac tissue in vitro from mouse embryonic stem cells. Circulation. 2006;113:2229–2237. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.583039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caspi O, Lesman A, Basevitch Y, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Habib IH, et al. Tissue engineering of vascularized cardiac muscle from human embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2007;100:263–272. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257776.05673.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens KR, Kreutziger KL, Dupras SK, Korte FS, Regnier M, Muskheli V, et al. Physiological function and transplantation of scaffold-free and vascularized human cardiac muscle tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:16568–16573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908381106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song H, Yoon C, Kattman SJ, Dengler J, Masse S, Thavaratnam T, et al. Interrogating functional integration between injected pluripotent stem cell-derived cells and surrogate cardiac tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3329–3334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905729106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tulloch NL, Muskheli V, Razumova MV, Korte FS, Regnier M, Hauch KD, et al. Growth of engineered human myocardium with mechanical loading and vascular coculture. Circ Res. 2011;109:47–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Verheijck EE, Wilders R, Joyner RW, Golod DA, Kumar R, Jongsma HJ, et al. Pacemaker synchronization of electrically coupled rabbit sinoatrial node cells. J Gen Physiol. 1998;111:95–112. doi: 10.1085/jgp.111.1.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yao JA, Gutstein DE, Liu F, Fishman GI, Wit AL. Cell coupling between ventricular myocyte pairs from connexin43-deficient murine hearts. Circ Res. 2003;93:736–743. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000095977.66660.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Passier R, van Laake LW, Mummery CL. Stem-cell-based therapy and lessons from the heart. Nature. 2008;453:322–329. doi: 10.1038/nature07040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macia E, Boyden PA. Stem cell therapy is proarrhythmic. Circulation. 2009;119:1814–1823. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.779900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zimmermann WH, Schneiderbanger K, Schubert P, Didie M, Munzel F, Heubach JF, et al. Tissue engineering of a differentiated cardiac muscle construct. Circ Res. 2002;90:223–230. doi: 10.1161/hh0202.103644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobita K, Liu LJ, Janczewski AM, Tinney JP, Nonemaker JM, Augustine S, et al. Engineered early embryonic cardiac tissue retains proliferative and contractile properties of developing embryonic myocardium. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1829–H1837. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00205.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kensah G, Gruh I, Viering J, Schumann H, Dahlmann J, Meyer H, et al. A novel miniaturized multimodal bioreactor for continuous in situ assessment of bioartificial cardiac tissue during stimulation and maturation. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2011;17:463–473. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2010.0405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Lange WJ, Hegge LF, Grimes AC, Tong CW, Brost TM, Moss RL, et al. Neonatal mouse-derived engineered cardiac tissue: a novel model system for studying genetic heart disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:8–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.242354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang YC, Khait L, Birla RK. Contractile three-dimensional bioengineered heart muscle for myocardial regeneration. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2007;80:719–731. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Black LD, 3rd, Meyers JD, Weinbaum JS, Shvelidze YA, Tranquillo RT. Cell-induced alignment augments twitch force in fibrin gel-based engineered myocardium via gap junction modification. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:3099–3108. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hansen A, Eder A, Bonstrup M, Flato M, Mewe M, Schaaf S, et al. Development of a drug screening platform based on engineered heart tissue. Circ Res. 2010;107:35–44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.211458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bian W, Liau B, Badie N, Bursac N. Mesoscopic hydrogel molding to control the 3D geometry of bioartificial muscle tissues. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1522–1534. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinto JG, Fung YC. Mechanical properties of the heart muscle in the passive state. J Biomech. 1973;6:597–616. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(73)90017-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winer JP, Oake S, Janmey PA. Non-linear elasticity of extracellular matrices enables contractile cells to communicate local position and orientation. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6382. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudson NE, Houser JR, O'Brien ET, 3rd, Taylor RM, 2nd, Superfine R, Lord ST, et al. Stiffening of individual fibrin fibers equitably distributes strain and strengthens networks. Biophys J. 2010;98:1632–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.12.4312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janmey PA, Winer JP, Weisel JW. Fibrin gels and their clinical and bioengineering applications. J R Soc Interface. 2009;6:1–10. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2008.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramaniam A, Jones WK, Gulick J, Wert S, Neumann J, Robbins J. Tissue-specific regulation of the alpha-myosin heavy chain gene promoter in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24613–24620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lien CL, Wu C, Mercer B, Webb R, Richardson JA, Olson EN. Control of early cardiac-specific transcription of Nkx2-5 by a GATA-dependent enhancer. Development. 1999;126:75–84. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christoforou N, Miller RA, Hill CM, Jie CC, McCallion AS, Gearhart JD. Mouse ES cell-derived cardiac precursor cells are multipotent and facilitate identification of novel cardiac genes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2008;118:894–903. doi: 10.1172/JCI33942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pedrotty DM, Klinger RY, Kirkton RD, Bursac N. Cardiac fibroblast paracrine factors alter impulse conduction and ion channel expression of neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2009;83:688–697. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hinds S, Bian W, Dennis RG, Bursac N. The role of extracellular matrix composition in structure and function of bioengineered skeletal muscle. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3575–3583. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.01.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kolossov E, Bostani T, Roell W, Breitbach M, Pillekamp F, Nygren JM, et al. Engraftment of engineered ES cell-derived cardiomyocytes but not BM cells restores contractile function to the infarcted myocardium. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2315–2327. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noorman M, van der Heyden MA, van Veen TA, Cox MG, Hauer RN, de Bakker JM, et al. Cardiac cell-cell junctions in health and disease: Electrical versus mechanical coupling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;47:23–31. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satin J, Kehat I, Caspi O, Huber I, Arbel G, Itzhaki I, et al. Mechanism of spontaneous excitability in human embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. J Physiol. 2004;559:479–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Caspi O, Itzhaki I, Kehat I, Gepstein A, Arbel G, Huber I, et al. In vitro electrophysiological drug testing using human embryonic stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:161–172. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kehat I, Khimovich L, Caspi O, Gepstein A, Shofti R, Arbel G, et al. Electromechanical integration of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22:1282–1289. doi: 10.1038/nbt1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malan D, Reppel M, Dobrowolski R, Roell W, Smyth N, Hescheler J, et al. Lack of laminin gamma1 in embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes causes inhomogeneous electrical spreading despite intact differentiation and function. Stem Cells. 2009;27:88–99. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hescheler J, Halbach M, Egert U, Lu ZJ, Bohlen H, Fleischmann BK, et al. Determination of electrical properties of ES cell-derived cardiomyocytes using MEAs. J Electrocardiol. 2004;37 Suppl:110–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2004.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bursac N, Papadaki M, Cohen RJ, Schoen FJ, Eisenberg SR, Carrier R, et al. Cardiac muscle tissue engineering: toward an in vitro model for electrophysiological studies. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:H433–H444. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.277.2.H433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vaidya D, Tamaddon HS, Lo CW, Taffet SM, Delmar M, Morley GE, et al. Null mutation of connexin43 causes slow propagation of ventricular activation in the late stages of mouse embryonic development. Circ Res. 2001;88:1196–1202. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pillekamp F, Reppel M, Brockmeier K, Hescheler J. Impulse propagation in late-stage embryonic and neonatal murine ventricular slices. J Electrocardiol. 2006;39:425, e421–e424. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bursac N, Aguel F, Tung L. Multiarm spirals in a two-dimensional cardiac substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15530–15534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400984101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bian W, Bursac N. Abstract 3548: Large 3-Dimensional Tissue Engineered Cardiac Patch With Controlled Electrical Anisotropy. Circulation. 2009;120:S821–S821. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zimmermann WH, Fink C, Kralisch D, Remmers U, Weil J, Eschenhagen T. Three-dimensional engineered heart tissue from neonatal rat cardiac myocytes. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2000;68:106–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yasui K, Liu W, Opthof T, Kada K, Lee J-K, Kamiya K, et al. If Current and Spontaneous Activity in Mouse Embryonic Ventricular Myocytes. Circ Res. 2001;88:536–542. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.5.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Engelmayr GC, Jr, Cheng M, Bettinger CJ, Borenstein JT, Langer R, Freed LE. Accordion-like honeycombs for tissue engineering of cardiac anisotropy. Nat Mater. 2008;7:1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nmat2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ott HC, Matthiesen TS, Goh SK, Black LD, Kren SM, Netoff TI, et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nat Med. 2008;14:213–221. doi: 10.1038/nm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furuta A, Miyoshi S, Itabashi Y, Shimizu T, Kira S, Hayakawa K, et al. Pulsatile cardiac tissue grafts using a novel three-dimensional cell sheet manipulation technique functionally integrates with the host heart, in vivo. Circ Res. 2006;98:705–712. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000209515.59115.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baar K, Birla R, Boluyt MO, Borschel GH, Arruda EM, Dennis RG. Self-organization of rat cardiac cells into contractile 3-D cardiac tissue. FASEB J. 2005;19:275–277. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2034fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bursac N, Loo Y, Leong K, Tung L. Novel anisotropic engineered cardiac tissues: studies of electrical propagation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;361:847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bian W, Liau B, Badie N, Bursac N. Abstract 18051: Engineering of Functional Cardiac Tissue Patch with Realistic Myofiber Orientations. Circulation. 2010;122:A18051–A18051. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Badie N, Bursac N. Novel micropatterned cardiac cell cultures with realistic ventricular microstructure. Biophys J. 2009;96:3873–3885. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kizana E, Chang CY, Cingolani E, Ramirez-Correa GA, Sekar RB, Abraham MR, et al. Gene transfer of connexin43 mutants attenuates coupling in cardiomyocytes: novel basis for modulation of cardiac conduction by gene therapy. Circ Res. 2007;100:1597–1604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.144956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sekar RB, Kizana E, Smith RR, Barth AS, Zhang Y, Marban E, et al. Lentiviral vector-mediated expression of GFP or Kir2.1 alters the electrophysiology of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes without inducing cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H2757–H2770. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00477.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Narmoneva DA, Vukmirovic R, Davis ME, Kamm RD, Lee RT. Endothelial cells promote cardiac myocyte survival and spatial reorganization: implications for cardiac regeneration. Circulation. 2004;110:962–968. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140667.37070.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim C, Majdi M, Xia P, Wei KA, Talantova M, Spiering S, et al. Non-cardiomyocytes influence the electrophysiological maturation of human embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes during differentiation. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:783–795. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pfannkuche K, Neuss S, Pillekamp F, Frenzel LP, Attia W, Hannes T, et al. Fibroblasts facilitate the engraftment of embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes on three-dimensional collagen matrices and aggregation in hanging drops. Stem Cells Dev. 2010;19:1589–1599. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Xi J, Khalil M, Spitkovsky D, Hannes T, Pfannkuche K, Bloch W, et al. Fibroblasts support functional integration of purified embryonic stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes into avital myocardial tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:821–830. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ieda M, Tsuchihashi T, Ivey KN, Ross RS, Hong TT, Shaw RM, et al. Cardiac fibroblasts regulate myocardial proliferation through beta1 integrin signaling. Dev Cell. 2009;16:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Domian IJ, Chiravuri M, van der Meer P, Feinberg AW, Shi X, Shao Y, et al. Generation of functional ventricular heart muscle from mouse ventricular progenitor cells. Science (New York, NY. 2009;326:426–429. doi: 10.1126/science.1177350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moretti A, Caron L, Nakano A, Lam JT, Bernshausen A, Chen Y, et al. Multipotent embryonic isl1+ progenitor cells lead to cardiac, smooth muscle, and endothelial cell diversification. Cell. 2006;127:1151–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Radisic M, Park H, Shing H, Consi T, Schoen FJ, Langer R, et al. Functional assembly of engineered myocardium by electrical stimulation of cardiac myocytes cultured on scaffolds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:18129–18134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407817101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cheng M, Moretti M, Engelmayr GC, Freed LE. Insulin-like growth factor-I and slow, bi-directional perfusion enhance the formation of tissue-engineered cardiac grafts. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:645–653. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shimizu T, Sekine H, Yang J, Isoi Y, Yamato M, Kikuchi A, et al. Polysurgery of cell sheet grafts overcomes diffusion limits to produce thick, vascularized myocardial tissues. FASEB J. 2006;20:708–710. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4715fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.