Abstract

Neutrophils enter the peripheral blood from the bone marrow and die after a short time. Molecular analysis of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis is difficult as these cells die rapidly and cannot be easily manipulated. We use conditional Hoxb8 expression to generate mouse neutrophils and test the regulation of apoptosis by extensive manipulation of B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2)-family proteins. Spontaneous apoptosis was preceded by downregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. Loss of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 homology domain (BH3)-only protein Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death (Bim) gave some protection, but only neutrophils deficient in both BH3-only proteins, Bim and Noxa, were strongly protected against apoptosis. Function of Noxa was at least in part neutralization of induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein (Mcl-1) in neutrophils and progenitors. Loss of Bim and Noxa preserved neutrophil function in culture, and apoptosis-resistant cells remained in circulation in mice. Apoptosis regulated by Bim- and Noxa-driven loss of Mcl-1 is thus the final step in neutrophil differentiation, required for the termination of neutrophil function and neutrophil-dependent inflammation.

Keywords: neutrophil granulocyte, apoptosis, Bcl-2 family, inflammation

Neutrophil granulocytes (neutrophils) are the main leukocyte population in human peripheral blood and a major leukocyte population in peripheral blood of mice. Neutrophils phagocytose and kill pyogenic bacteria1 and are the first cellular line of defense to infections with other pathogens, for instance, Chlamydia2 and Leishmania.3 Neutrophils invade tissues from the bloodstream in response to infection or injury.4 During the resolution of infection, they die by apoptosis and are taken up by macrophages.5

Neutrophils are constantly produced in the bone marrow and enter circulation where they die after a short time.1, 6, 7 Neutrophils are ‘programmed to die': apoptosis is their regular fate. The neutrophil life span can be extended by inflammatory mediators of host (e.g., granuloyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor, interleukin 3, tumor necrosis factor) or pathogen origin (e.g., lipopolysaccharide). These signals probably operate to keep neutrophils alive in the inflammatory environment long enough to effectively combat bacteria.8, 9 Inhibition of neutrophil apoptosis can exacerbate tissue inflammation,10 suggesting that apoptosis is the relevant mechanism to turn off neutrophil-mediated inflammation.

Several studies have addressed the molecular regulation of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis.8, 9 Two major signaling pathways mediate apoptosis in mammalian cells, the death receptor pathway (for instance, through Fas and TRAIL)11 and the mitochondrial pathway.12

Mitochondrial apoptosis is regulated by the B-cell lymphoma protein 2 (Bcl-2) family.13 This family has eight pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 homology domain (BH3)-only proteins that act as upstream triggers and can be activated by transcription, phosphorylation and probably other mechanisms. BH3-only proteins activate the pro-apoptotic effectors Bcl-2-associated X protein (Bax) and/or Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer (Bak), which permit cytochrome-c release from mitochondria. The anti-apoptotic Bcl-2-like proteins (Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bcl-w, induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein (Mcl-1) and A1) inhibit this, probably by direct binding of pro-apoptotic proteins. The exact mechanisms of Bax/Bak-activation and the action of Bcl-2-like proteins are under dispute.13

Although Fas stimulation can induce neutrophil apoptosis, Fas-defective neutrophils die normally.14, 15 In contrast, mouse neutrophils overexpressing transgenic Bcl-2 or lacking pro-apoptotic Bcl-2-interacting mediator of cell death (Bim) show reduced spontaneous apoptosis.15, 16

Neutrophils are relatively little understood, owing to the peculiarity that they die rapidly in culture. Moreover, only relatively few cells can be isolated from mice, and human neutrophils cannot be genetically modified. However, an experimental system overcoming these limitations has recently been introduced.17 This system utilizes a conditional estrogen-dependent version of the homeobox protein Hoxb8 to expand mouse hematopoietic progenitors in the presence of stem cell factor (SCF). Deactivation of Hoxb8 initiates the differentiation of the progenitors into cells with all tested characteristics of neutrophils. As these cells can be generated from any genetically modified mouse and are amenable to overexpression and knockdown strategies, they provide a versatile experimental system.

We used this system to analyze the regulation of neutrophil spontaneous apoptosis. Using gene-deficient cells and cells over- or under-expressing Bcl-2-family genes, we in particular describe an unexpectedly strong pro-apoptotic role of the BH3-only protein Noxa, which acts in concert with Bim to limit the life span of neutrophils.

Results

Spontaneous apoptosis in Hoxb8-derived neutrophils is comparable to apoptosis in primary neutrophils

Progenitor cell lines were generated by retroviral transduction of bone marrow cells with ER-Hoxb8 as described,17 followed by long-term culture in the presence of estrogen and SCF. These cells have a morphological promyelocyte-like appearance in culture over several months. Hoxb8 inactivation led to homogenous differentiation into cells morphologically indistinguishable from mouse primary neutrophils (Supplementary Figure S1A). All wild type (wt) and mutant cell lines had the same morphological appearance as progenitors and upon differentiation (Supplementary Figure S1B, data not shown).

As in vivo, primary neutrophils rapidly undergo apoptosis in culture, which can be slowed down by pro-inflammatory mediators. Hoxb8-derived neutrophils (here referred to as neutrophils) also died rapidly (about 80% were dead after 24 h; Supplementary Figure S1E). Neutrophils were used on day 4 of differentiation when they appeared homogenously mature. SCF was then removed to mimic the release from bone marrow. The receptor of SCF, c-kit, was downregulated during differentiation to a level comparable to primary bone marrow-sorted neutrophils (Supplementary Figures S1C and D).

As reported for primary neutrophils, cell death was reduced by SCF, granuloyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor or lipopolysaccharide (Supplementary Figure S1E). In primary neutrophils, a correlation of factor-dependent survival with high expression of Mcl-1 has been reported. We found that spontaneous cell death correlated with Mcl-1 loss, whereas culture with pro-inflammatory factors increased Mcl-1 protein expression (Supplementary Figure S1F). Neutrophils also were capable of efficient phagocytosis of bacteria (Supplementary Figure S1G), oxidative burst (Supplementary Figure S1H) and cytokine production upon bacterial stimulation (Supplementary Figures S1I and K).

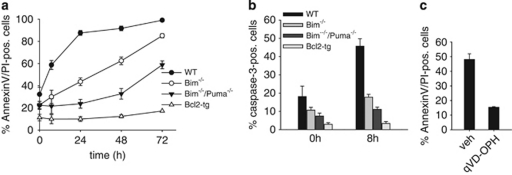

Loss of Bim or overexpression of Bcl-2 protects primary neutrophils against spontaneous apoptosis.15, 16 Neutrophils derived from cells that had either been established from bone marrow from Bim-deficient or from Bcl-2-transgenic mice were similarly protected (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

Spontaneous apoptosis of differentiated Hoxb8 neutrophils of various genotypes. (a and b) Analysis of spontaneous apoptosis of Hoxb8 neutrophils by staining with AnnexinV–FITC and propidium iodide (PI) (a) or staining for active caspase-3 (b). Mature neutrophils of the indicated genotypes (differentiated for 4 days by estrogen withdrawal) were incubated in the absence of SCF for the indicated time periods and analyzed by flow cytometry. Shown are all AnnexinV-positive cells, including cells staining double positive for AnnexinV and PI (a). Data are mean/S.E.M. of three experiments. (c) AnnexinV/PI staining of differentiated wt neutrophils SCF deprived for 24 h in the presence of the pan-caspase inhibitor qVD-OPH (50 μM) or DMSO as vehicle control (veh). Data are mean/S.E.M. (n=3 experiments)

In lymphocytes, cell death in the absence of Bim depends in part on Puma.18 We therefore included Bim/Puma double-deficient neutrophils in this study. Loss of Puma gave additional protection to Bim-deficient neutrophils, although cell death was still considerably higher than in Bcl-2-transgenic cells (Figure 1a).

Cell death was accompanied by caspase-3-activation, which was reduced in Bim-negative and Bcl-2-overexpressing cells (Figure 1b), and the pan-caspase-inhibitor qVD-OPH blocked spontaneous cell death (Figure 1c). These results reproduce for Hoxb8-derived neutrophils the results that are reported for primary neutrophils.

Regulation of Bcl-2-family proteins during spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis

Bim is the most important BH3-only protein in the hematopoietic system. In lymphocytes, Bim-dependent apoptosis is associated with an induction of Bim protein (T cells,19 B cells,20 NK cells21). In neutrophils, spontaneous apoptosis was not accompanied by increased Bim protein levels, at least at early stages when the Bim effect is most obvious (see below, Figure 2). The apoptosis-associated induction of Bim (and of Puma) can be driven by increased FOXO3a-dependent transcription.18, 22 We expressed FOXO3a-specific shRNA by lentiviral transduction of wt progenitor lines. This led to a substantial reduction of FOXO3a protein both in progenitors and in differentiated neutrophils (Supplementary Figure S2A). Downregulation of FOXO3a did not decrease Bim levels (Supplementary Figure S2B), and neutrophils with reduced FOXO3a died at the same rate as control cells (Supplementary Figure S2C). Bim-dependent neutrophil apoptosis therefore appears to be independent of FOXO3a.

Figure 2.

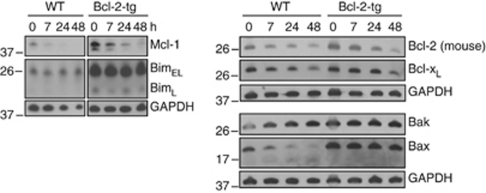

Bcl-2-family protein expression levels during spontaneous apoptosis in Hoxb8 neutrophils. Immunoblot analysis of wt and Bcl-2-tg neutrophils. Mature neutrophils were SCF deprived for the indicated time periods. Equivalents of 9 × 105 cells/sample were directly lysed in Laemmli buffer, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for expression of Mcl-1, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bim, Bax or Bak. GAPDH served as loading control. Shown is one of two independent experiments with similar results

To determine the levels of Bcl-2-family proteins during spontaneous apoptosis in neutrophils, wt neutrophils were followed over 48 h and compared with Bcl-2-overexpressing neutrophils. Because of the massive apoptosis in wt neutrophils, events consecutive to cell death may confound expression levels of proteins. As Bcl-2-overexpressing cells show almost no cell death, changes observed in these cells are likely to be involved in the regulation of apoptosis rather than being a consequence.

Bcl-2-overexpressing neutrophils had higher levels of Bim and also of Bax and Bak (Figure 2). There was no clear increase in Bim levels during spontaneous apoptosis (Figure 2). Notably, there was a loss of Bax (and appearance of a smaller faint band) in wt but not in Bcl-2-overexpressing cells, which may reflect protein loss or consumption (and perhaps cleavage) during apoptosis. Bak levels were slightly increased in both lines (Figure 2).

Although these changes in levels of pro-apoptotic proteins appear fairly small, there were stronger changes in levels of anti-apoptotic proteins. We found a moderate, relatively late but clearly detectable decline in Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL levels. The strongest and most rapid change occurred in Mcl-1 with a strong reduction already at 7 h, regardless of the overexpression of Bcl-2 and therefore independent of cell death (Figure 2). Genetic loss of Mcl-1 causes neutrophil death already during differentiation.23 This makes Mcl-1 a prime candidate for the regulation of neutrophil spontaneous apoptosis. We were unable to detect endogenous A1 protein.

Regulation of Bcl-2-family proteins during neutrophil differentiation

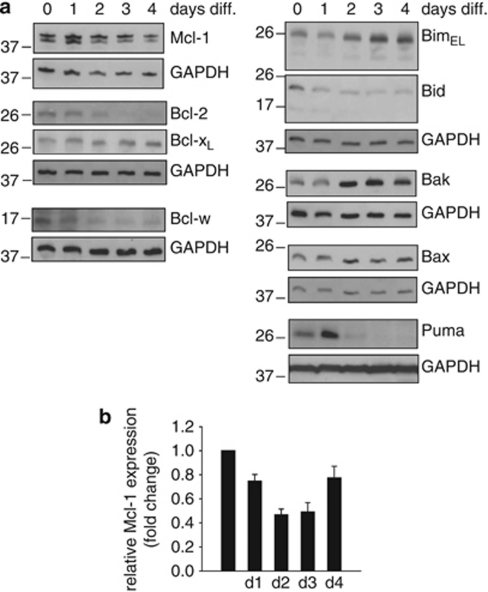

In order to better understand the ‘starting point' of spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis, we followed the expression of Bcl-2-family proteins during differentiation of neutrophils from progenitor lines. There was a considerable increase of Bim, a decrease of BH3-interacting domain death agonist, a small increase of Bax and (more strongly) of Bak (Figure 3). Expression of the BH3-only protein Puma initially increased, but was decreased in mature cells. Further, a decrease of the anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-w and Mcl-1 was seen, with only Bcl-XL remaining constant during differentiation. Although there was a small decline in Mcl-1–mRNA levels during differentiation (Figure 3b), this seemed insufficient to explain the loss of Mcl-1 protein, suggesting post-translational regulation. This protein expression pattern in mature neutrophils indicates a state of high sensitivity to apoptosis.

Figure 3.

Bcl-2-family protein levels during neutrophil differentiation. (a) Immunoblot analysis of Hoxb8 neutrophils during estrogen-withdrawal-induced differentiation. Equivalents of 6 × 105 cells/sample were directly lysed in Laemmli buffer, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for protein expression of Bcl-2-family proteins. GAPDH served as loading control. Data are representative of a total of three experiments. (b) Quantification of mRNA levels of Mcl-1 by real-time PCR in wt neutrophils during differentiation. mRNA levels are shown as ‘fold change' relative to mRNA expression in progenitors (day 0). Data are normalized to β-actin expression and represent mean/S.E.M. of 4–6 experiments

Experimental overexpression of Bcl-2-like proteins

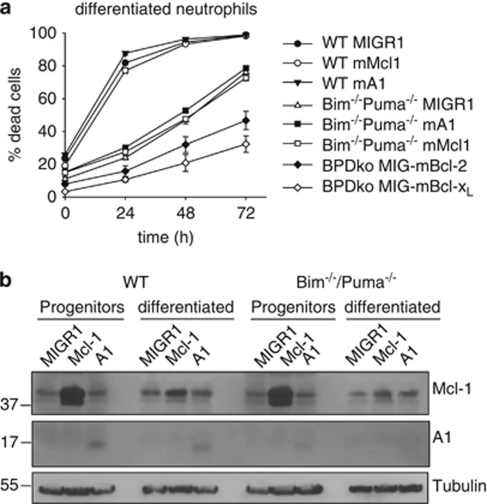

As these results suggested a role of Mcl-1 (and Bcl-2) downregulation in spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis, we tested the effect of overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins in neutrophils. Progenitor lines were retrovirally transduced for stable expression of individual proteins. We had already observed the strong anti-apoptotic effect of Bcl-2-overexpression (see Figure 1a). Surprisingly, there was no protection by either Mcl-1 or A1 expression in neutrophils (Figure 4a). The same was seen when Mcl-1 or A1 was overexpressed in Bim/Puma double-deficient cells, suggesting an independent regulation mechanism (Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL efficiently protected also in Bim/Puma double-deficient neutrophils, Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Protection by antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members in wt and Bim−/−/Puma−/− neutrophils. (a) Analysis of spontaneous apoptosis of differentiated wt and Bim−/−/Puma−/− neutrophils stably expressing either empty vector control (MIGR1) or anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1or A1. Mature neutrophils were incubated in the absence of SCF for the indicated time periods. Cell death was analyzed by propidium iodide staining. Data are mean/S.E.M. (n=3 experiments for empty vector control, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1 and A1; n=2 experiments for Bcl-2). (b) Immunoblot analysis of wt and Bim−/−/Puma−/− neutrophil progenitors and differentiated neutrophils stably expressing either empty vector control (MIGR1) or anti-apoptotic proteins Mcl-1 or A1. Cells were harvested as progenitors or as mature neutrophils after estrogen-withdrawal-induced differentiation for 4 days. Laemmli lysates (9 × 105 cells/lane) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for protein expression of Mcl-1 and A1 as indicated. Tubulin served as loading control. Data are representative of three independent experiments

Analysis of protein levels showed that although strong overexpression of Mcl-1 protein was seen in progenitor cells transduced with Mcl-1 retrovirus, this overexpression was almost undetectable in differentiated neutrophils (Figure 4b). Overexpressed A1 protein was seen in both progenitors and differentiated neutrophils (Figure 4b). Progenitor cells, which are constantly cultured in the presence of SCF, die rapidly upon factor removal (Supplementary Figure S3A). In these cells, Mcl-1 provided strong protection whereas protection by A1 was smaller but still considerable (Supplementary Figure S3A). As both proteins were expressed as untagged proteins, we cannot directly compare the relative protein expression levels. All transgenic progenitor lines were sorted to achieve similar GFP levels (which is expressed from an IRES of the encoded mRNA), indicating that the generation of protein is similar. In progenitor cells, apoptosis was further accompanied by a strong induction of Bim (Supplementary Figure S3B).

The BH3-only protein Noxa contributes to neutrophil spontaneous apoptosis

These results suggested that mechanisms exist that cause Mcl-1 downregulation first during differentiation and later during spontaneous neutrophil death, and that this downregulation is responsible for apoptosis and life-span restriction of neutrophils. One known mechanism regulating Mcl-1 levels is the induction of the BH3-only protein Noxa. Noxa can directly bind Mcl-1, which can trigger the proteolytic degradation of Mcl-1 by the proteasome.24

We were unable to detect Noxa protein consistently in neutrophils but some Noxa was detectable in progenitors by western blotting. No increase of Noxa levels was seen during factor deprivation-induced apoptosis of progenitors (Supplementary Figure S3B). This is however not conclusive evidence against a contribution of Noxa, as Noxa is probably co-degraded with Mcl-1 and levels therefore could also go down.

To test the role of Noxa, we established progenitor lines from Noxa-deficient mice. Neutrophils differentiated from Noxa-deficient lines showed slightly improved survival (Figure 5a). However, Bim/Noxa double-deficient cells were almost completely protected against apoptosis over 72 h and substantially improved even over Bim/Puma-deficient cells (Figure 5a). The additional effect of Noxa deficiency was further demonstrated by RNAi. Lentiviral transfer of Noxa-specific shRNA in Bim/Puma double-deficient progenitors led to a substantial reduction in Noxa protein levels (Supplementary Figure S4B). Upon differentiation, Bim/Puma double-deficient neutrophils carrying Noxa-specific shRNA were more strongly protected against spontaneous apoptosis than Bim/Puma double-deficient controls (Supplementary Figure S4A). The cells had moderately enhanced expression of Mcl-1, but the decrease of Mcl-1 during spontaneous apoptosis was clearly slower (Supplementary Figure S4C).

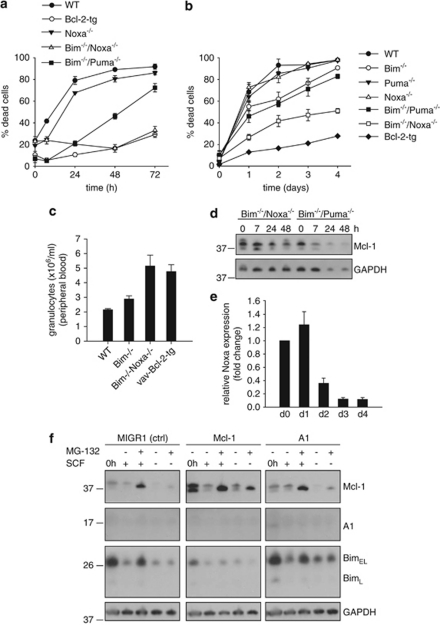

Figure 5.

Regulation of spontaneous apoptosis in neutrophils by Bim and Noxa. (a) Spontaneous apoptosis of mature neutrophils of various genotypes (starting at day 4 of estrogen withdrawal). Cell death was analyzed by propidium iodide staining, followed by flow cytometry. Data are mean/S.E.M. of three (Bcl-2-tg, Noxa−/−, Bim−/−/Puma−/−) or four (wt, Bim−/−/Noxa−/−) independent experiments. (b) Spontaneous apoptosis of primary neutrophils from wt, single (Bim−/−, Puma−/−, Noxa−/−) or double (Bim−/−/Puma−/−, Bim−/−/Noxa−/−) gene-deficient mice or vav-Bcl-2-transgenic mice. Neutrophils isolated from bone marrow were cultured in vitro and harvested at the indicated time points. Cell death was determined by propidium iodide staining and flow cytometry analysis. Data are mean/S.E.M. of a total of three (Bim−/−, Puma−/−, Noxa−/−, Bim−/−/Puma−/−, vav-Bcl-2) or four mice (wt, Bim−/−/Noxa−/−). (c) Double deficiency of Bim and Noxa leads to accumulation of granulocytes in peripheral blood of mice. Comparison of peripheral blood granulocyte counts ( × 106/ml) from wt (n=5), Bim-deficient (n=4), Bim/Noxa double-deficient (n=5) or vav-Bcl-2-tg mice (n=9). Granulocyte numbers of peripheral blood were analyzed using a scil Vet abc blood cell counter. Data represent mean/S.E.M. (d) Mcl-1 expression during spontaneous apoptosis of Bim/Noxa and Bim/Puma double-deficient neutrophils. Mature neutrophils (differentiated for 4 days) were SCF deprived for the indicated time periods. Equivalents of 9 × 105 cells/sample were directly lysed in Laemmli buffer, analyzed by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted for expression of Mcl-1. GAPDH served as loading control. Shown is one of three independent experiments with similar results. (e) Quantification of mRNA levels of Noxa by real-time PCR in wt neutrophils during differentiation. mRNA levels are shown as ‘fold change' relative to mRNA expression in precursor cells (day 0). Data are normalized to β-actin expression and represent mean/S.E.M. of four experiments. (f) Immunoblot analysis of protein expression in neutrophils upon proteasome inhibition. Differentiated wt neutrophils were either SCF deprived or not for 14 h, then treated with 10 μM MG-132 or solvent control for 6 h. Nine times 105 cells/lane were lysed in Laemmli buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting for Mcl-1, A1 and Bim. Equal loading was confirmed by probing for GAPDH. Data are representative of two independent experiments

These results indicate that Noxa is an important mediator of neutrophil spontaneous apoptosis, at least in part through antagonizing Mcl-1. We confirmed these effects in primary neutrophils isolated from various gene-deficient mice. There was no significant survival advantage in Noxa single-deficient cells. The reported moderate apoptosis defect in Bim-deficient neutrophils was confirmed (Figure 5b), but cells from Bim/Noxa double-deficient mice demonstrated substantially reduced apoptosis compared with either Bim-deficient or Bim/Puma double-deficient cells. Bim and Noxa thus cooperate to trigger spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis.

We further determined granulocyte numbers in peripheral blood of Bim/Noxa double-deficient mice compared with wt, Bim-deficient and Bcl-2-transgenic animals (Figure 5c). Double deficiency of Bim and Noxa led to an approximately 2.4-fold increase in granulocyte numbers compared with wt and to an 1.8-fold increase compared with Bim−/−. Neutrophil counts in Bim/Noxa double-knockout mice are thus comparable to those in Bcl-2-transgenic mice. Protection against spontaneous apoptosis and absolute numbers in peripheral blood therefore correlate.

During spontaneous apoptosis of differentiated neutrophils, the role of Noxa appeared to be the targeting and downregulation of Mcl-1: comparison of Bim/Puma-deficient and Bim–Noxa-deficient cells showed a slower decrease of Mcl-1 in neutrophils lacking Noxa (Figure 5d).

Intriguingly, despite its strong functional contribution, the levels of Noxa mRNA declined during differentiation (Figure 5e). Relatively small amounts of Noxa mRNA therefore seem sufficient for Noxa function in neutrophils.

Proteasome inhibition showed that the loss of Mcl-1 protein was strongly determined by proteolytic destruction (Figure 5f). This was particularly apparent in Mcl-1-overexpressing cells. This strongly supports the view that in neutrophils, Mcl-1 levels are regulated by mechanisms targeting its turnover, which are strong enough to counteract retroviral overexpression. One possible mechanism controlling Mcl-1 turnover is Glycogen–synthase–kinase 3 (GSK3)-mediated phosphorylation of Mcl-1 on specific serine sites, which destabilizes Mcl-1 by promoting proteasomal degradation of the protein.25 We tested this possibility by analyzing the effect of a GSK3-specific inhibitor on Mcl-1 turnover and cell death during spontaneous apoptosis. No protection from spontaneous apoptosis and no effect on Mcl-1 protein levels could be seen (data not shown), which argues against a role of GSK3 for regulation of Mcl-1 levels in mature neutrophils.

The Noxa–Mcl-1 axis in progenitor cells

In progenitors, there was no significant protection by individual loss of Noxa or Bim or by combined loss of Bim and Puma. However, there was very strong protection by the combined loss of Bim and Noxa (Supplementary Figure S4D). Again, death of these progenitors was accompanied by Mcl-1 loss, and this loss was slower in the absence of Noxa (Supplementary Figure S4E).

We further expressed A1 or Mcl-1 in Noxa-deficient progenitors. Loss of Mcl-1 during differentiation still occurred, although it was slowed down in Noxa-deficient cells, indicating that mechanisms other than Noxa binding contribute to the loss of Mcl-1 (Supplementary Figure S5A). Accordingly, there was no protection against apoptosis in neutrophils differentiated from Noxa-deficient, Mcl-1-overexpressing progenitors (Supplementary Figure S5B). In progenitors however, both Mcl-1 and A1 provided better protection in the absence of Noxa (Supplementary Figure S5C) than in its presence (wt progenitors Supplementary Figure S3A), suggesting that Noxa also in these cells exerts a pro-apoptotic effect through neutralizing A1 and Mcl-1.

Preliminary experiments indicate that downregulation of Mcl-1 in progenitor cells by RNAi induced apoptosis in wt, Noxa- and Bim/Noxa-deficient progenitor cells to a similar extent (data not shown). This supports the view that loss of Mcl-1 (in part probably dependent on Noxa) is a contributing factor to spontaneous apoptosis.

Combined loss of Bim and Noxa prolongs neutrophil activity

We have previously provided evidence suggesting that inhibition of apoptosis by Bcl-2 also preserves functional activity of neutrophils.10 To test the relevance of Bim/Noxa loss for neutrophil function, we cultured Bim/Noxa-deficient neutrophils for 48 h (at this point, almost all wt cells would be dead, Figure 1a). When Bim/Noxa double-deficient cells at 48 h were tested for function, cells were still fully capable of phagocytosis of bacteria (Figure 6a), oxidative burst (Figure 6b) and tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 production (Figures 6c and d). When Bim/Noxa double-deficient neutrophils were injected into mice, they could be detected in peripheral blood much longer than wt cells, suggesting better survival also in vivo (Figure 6e). Apoptosis is thus the central process that regulates not only neutrophil apoptosis in vitro and in vivo but also their function. On a molecular level, neutrophil apoptosis is regulated by the loss of Mcl-1 function and by the combined effects of Bim and Noxa.

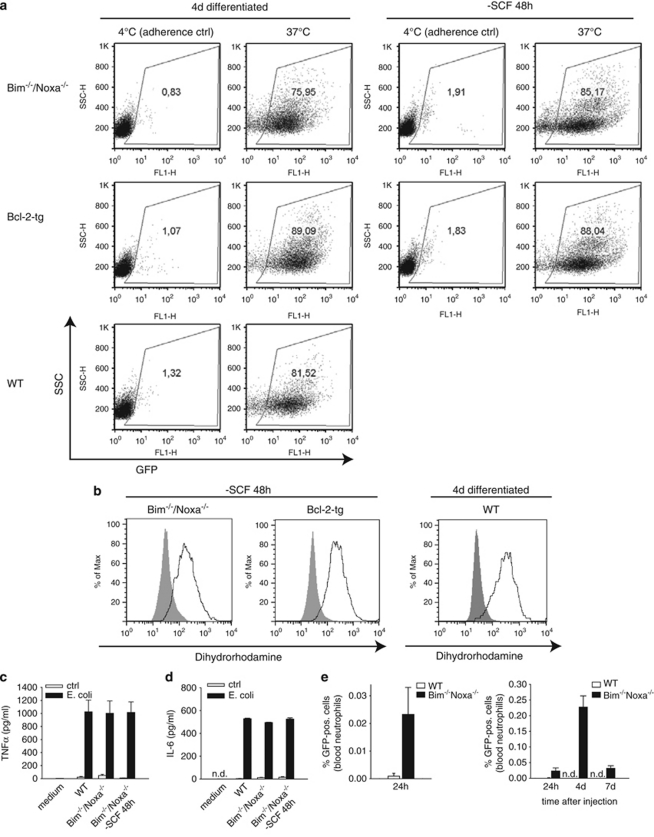

Figure 6.

Inhibition of apoptosis through combined loss of Bim and Noxa maintains neutrophil effector function. (a) Phagocytic uptake of GFP-expressing E. coli by SCF-deprived Bim−/−/Noxa−/− neutrophils. Neutrophils were subjected to co-incubation at 37 or 4°C (adherence control) with E. coli either immediately after differentiation (all genotypes) or after additional SCF deprivation for 48 h (Bim−/−/Noxa−/− and Bcl-2-tg). After 1 h of co-incubation, cells were extensively washed and analyzed by flow cytometry. Uptake is indicated by GFP fluorescence. Similar results were seen in two independent experiments. (b) Production of reactive-oxygen species was measured by the capacity of neutrophils to oxidize dihydrorhodamine. Bim−/−/Noxa−/− or Bcl-2-tg neutrophils differentiated for 4 days were additionally SCF deprived for 48 h and analyzed in comparison with viable wt neutrophils (differentiated for 4 days). Neutrophils were incubated for 30 min with PMA (5 μg/ml, bold line). Unstimulated stained cells are shown as shaded histogram. Similar results were seen in two independent experiments. (c and d) Secretion of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α (c) or interleukin (IL)-6 (d) was measured by ELISA in supernatants of neutrophils stimulated with E. coli for 16 h at a bacteria/cell ratio of 200 : 1. Data are means/S.E.M. of three independent experiments. (e) Ex vivo analysis of neutrophil survival after intravenous injection into mice. Either wt or Bim/Noxa double-deficient neutrophils carrying GFP as a marker were differentiated in vitro for 4 days and then intravenously injected into wt C57Bl/6 mice (2 × 107 cells/mouse). The percentage of GFP-positive cells in the blood, relating to total blood neutrophils, was analyzed by flow cytometry at the indicated time points. Shown are percentages of GPF-positive cells of all blood neutrophils after 24 h (left panel), and after 24 h, 4 days, and 7 days (right panel). Data represent mean/S.E.M. of a total of four mice for each group (n.d., not detectable)

Discussion

In this study, we probe the role of the Bcl-2-family protein in Hoxb8-differentiated neutrophils. The comparison with primary, freshly isolated mouse neutrophils indicates the suitability of these cells for the study of primary neutrophil physiology. Our data confirm earlier results obtained with primary neutrophils but provide substantial new information about the molecular players regulating neutrophil spontaneous apoptosis.

Hoxb8-differentiated neutrophils are obviously not primary neutrophils. However, they have the morphological and functional hallmarks and express all the markers found in primary neutrophils.17 Importantly, for this study, they show the typical high rate of spontaneous apoptosis in culture. The possibility of generating cell lines from genetically modified mice and of over- and underexpressing genes in these neutrophils by transduction of progenitors allows a much more profound study of the regulation of neutrophil function and apoptosis.

There were subtle differences in apoptosis sensitivity between gene-modified Hoxb8-derived and primary neutrophils: the effect of loss of Puma or Noxa on top of Bim deficiency was less pronounced in primary neutrophils. However, there is no unequivocal standard for the isolation or investigation of primary neutrophils. We used neutrophils sorted from mouse bone marrow, a commonly used source, but these cells are heterogeneous in terms of maturation status and they may have suffered during isolation. It is therefore difficult to know what in fact the ‘best neutrophil' would be.

Human neutrophils undergoing apoptosis lose expression of Mcl-1, and in the presence of survival-prolonging factors, this decrease is slower.26 It has recently also been shown that genetic deletion of Mcl-1 prevented the generation of mature neutrophils, most likely due to apoptosis of immature myeloid progenitors.23 Our data show that Mcl-1 rapidly decreases in mature neutrophils also in situations where apoptosis is independently blocked by overexpression of Bcl-2. This suggests that the loss of Mcl-1 and probably other anti-apoptotic proteins is a primary event that triggers apoptosis.

The levels of Mcl-1 appear in many situations to be regulated by protein turnover. Mcl-1 degradation has been shown to be regulated not only by the deubiquitinase USP9X27 but also by ubiquitin-independent degradation.28 As upstream regulators of Mcl-1 degradation, GSK3-dependent phosphorylation25 and binding by the BH3-only protein Noxa24 have been identified. Noxa-deficient neutrophils (and progenitors) showed slightly elevated Mcl-1 levels and slower reduction in Mcl-1 levels during spontaneous apoptosis than wt cells. Noxa is therefore in part responsible for the loss of Mcl-1. As (slower) Mcl-1 degradation still occurred in the absence of Noxa, other factors such as PI3-kinase/GSK3 signalling also may be relevant.

Noxa is required for normal spontaneous neutrophil apoptosis. Indeed, the effect of the loss of Noxa in Bim-deficient cells may be the strongest effect of Noxa loss reported to date. Bim and Noxa together were responsible for most of this form of apoptosis. In the absence of Noxa, there was only a small reduction in apoptosis; Bim therefore seems to be able to do most of the work. However, there was still considerable apoptosis in the single absence of Bim, and this apoptosis was mediated by Noxa.

Transgenic overexpression of Bcl-2 provided still somewhat stronger protection than the combined loss of Bim and Noxa. Perhaps additional BH3-only proteins such as Puma, Bmf or Bad have some small effect that is unmasked by the loss of Bim and Noxa. We think it also conceivable that a small amount of apoptosis occurs without contribution from BH3-only proteins, perhaps through cytosolic changes that directly activate Bax or Bak, and this small effect would also be blocked by direct binding of Bcl-2 to Bax/Bak.

The only molecular mechanism of Noxa action known is linked to the antagonism of Mcl-1 and A1. All our results are consistent with this mode of action. Noxa very likely regulates the levels of Mcl-1, and in the absence of Bim, this is necessary for full apoptosis. Bim, on the other hand, can overcome the protection by Mcl-1. Authors are divided on the view whether Mcl-1 blocks apoptosis by binding to Bax and Bak or by binding to BH3-only proteins like Bim.13 Either way, in neutrophils, the activity of Bim is the main trigger of spontaneous apoptosis, but apoptosis is modulated by Noxa, which in turn regulates the function of Mcl-1 and probably A1.

How Bim is activated in this situation is not entirely clear. There was no increase in Bim levels, although Bim was clearly activated. There was, however, also a moderate reduction in protein levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL. It seems likely that this downregulation is involved in the activation of Bim. Moreover, Bim induction does not necessarily correlate with its activation, as was previously demonstrated for lipopolysaccharide- or granuloyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor-induced survival.29, 30

Neutrophils in the Hoxb8 system differentiate from progenitors that morphologically resemble early promyelocytes. In these cells, the effect of the loss of Bim or Noxa alone was marginal but a very strong effect was seen when both were missing.

On their way from progenitors to neutrophils, the cells acquire a phenotype already inclined towards apoptosis: there was downregulation of Bcl-2, Bcl-XL and Mcl-1, together with upregulation of Bax, Bak and Bim. One interpretation of these changes is that not only mature neutrophils are programmed to die but also already a progenitor cell starts this program, perhaps when it stops dividing.

Neutrophil apoptosis is a program that runs independently of programs that regulate functional capacity: when apoptosis was blocked by the loss of Bim and Noxa, cells were still fully functional. On a therapeutic level, this may be relevant as it indicates that strategies aiming at apoptosis inhibition will preserve neutrophil function and may be useful in situations of human neutropenia.

We believe that the Hoxb8 system is well suited for the analysis not only of apoptosis but also for other investigations into neutrophil function. For apoptosis research, it has the advantage of combining a near-physiological situation of apoptosis, a non-transformed cell and the ease of the generation of relatively large numbers of cells with the possibility of easy genetic manipulation.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and cell culture

Hoxb8 neutrophil progenitors were derived from bone marrow of wt, Bim−/−-, Noxa−/−-, Bim−/−/Puma−/−-, Bim−/−/Noxa−/−-deficient and (human) vav-bcl2-transgenic mice on C57Bl/6 background. Polyclonal precursor cell lines were established by retroviral transduction of Hoxb8 and selection in the presence of SCF, as described.17 Precursor cell lines were cultured in Optimem medium (Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany) supplemented with 10% FCS (PAA, Coelbe, Germany), 30 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma, Munich, Germany), antibiotics (100 IU/ml penicillin G and 100 IU/ml streptomycin sulfate, PAA), 1–4% supernatant from SCF-producing Chinese Hamster Ovarian cells, and 1 μM estrogen (Sigma). Neutrophil differentiation was induced by removal of estrogen and subsequent culture for 4 days in medium containing 1–2% SCF-supernatant. To assess differentiation status, cells were subjected to cytospin followed by Giemsa staining and analyzed by light microscopy. In some experiments, cells were treated with lipopolysaccharide (Sigma), PMA (Sigma), the pan-caspase inhibitor qVD-OPH (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) or MG-132 (Enzo Life Sciences, Lörrach, Germany).

Isolation of primary mouse neutrophils

Mouse neutrophils were positively selected from bone marrow of wt and mutant mice using the Miltenyi MACS Purification Kit (Miltenyi Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany). Following harvest of bone marrow cells and red blood cell lysis, neutrophils were labeled with FITC-coupled anti-Gr-1 antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), followed by anti-FITC antibody coupled to magnetic beads. Labeled cells were isolated by passage over a MACS column (Miltenyi Biotech). Gr-1-positive cells were cultured in Optimem medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FCS, 30 mM β-mercaptoethanol and antibiotics and analyzed as indicated.

Quantification of mouse granulocyte numbers in peripheral blood

100 μl of heparinized blood were collected from the orbital sinus of mice. Samples were analyzed in a scil Vet abc (Scil Animal Care Company GmbH, Viernheim, Germany).

Retroviral transduction of neutrophil precursor lines

To generate Hoxb8 precursor lines stably overexpressing various anti-apoptotic proteins, mouse Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Mcl-1 and A1 were transferred from pENTR/SD/D-TOPO vector into MIGR1-GW retroviral vector by gateway-based LR recombination reaction, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Retroviral particles were produced by transient transfection of the corresponding retroviral expression plasmids together with packaging plasmid pCLEco into the ecotrophic Phoenix packaging cell line using Fugene HD transfection reagent (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Retroviral supernatants were harvested on day 2 and 3, filtered through 0.45 μm membranes and used for infection of target cells at a cell density of 1–2 × 105/ml in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene. GFP-positive cells were FACS sorted, and precursor lines with >90% of GFP-positive cells were used for experiments.

Lentiviral transduction for generation of shRNA-mediated stable knockdown lines

For establishment of shRNA-mediated stable knockdown lines, a lentiviral system was used essentially as described.31 Briefly, shRNA sequences were cloned into pENTR-THT and transferred via Gateway LR recombinase reaction (Invitrogen) into the lentiviral destination vector pHR-dest-SFFV-eGFP. Production of lentiviral particles was performed by transient transfection of shRNA expression vectors into HEK 293FT cells (Invitrogen), together with packaging plasmids psPAX2 and pMD2.G (Dr. Didier Trono, Lausanne) using Fugene HD transfection agent (Roche). Lentiviral supernatants were harvested on day 2 and 3, filtered through 0.45 μm membranes, and used for infection of target cells at a density of 1–2 × 105/ml in the presence of 5 μg/ml polybrene. GFP-positive cells were cell sorted and precursor lines with >90% of GFP-positive cells were used for experiments.

Apoptosis assays

For analysis of apoptosis by AnnexinV–propidium iodide staining, Hoxb8 neutrophils were differentiated for 4 days, then washed in PBS/10% FCS, and cultured in the absence of SCF for the indicated time periods. After washing with AnnexinV-binding buffer (10 mM Hepes, 140 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM CaCl2), cells were incubated with AnnexinV–FITC or AnnexinV–APC (1 : 50, BD Pharmingen, Heidelberg, Germany) and propidium iodide (1 μg/ml, Sigma) for 20 min, followed by flow cytometry analysis.

In some experiments, cell death was assessed by propidium iodide staining (1 μg/ml) for loss of cell membrane integrity, followed by flow cytometry analysis.

For analysis of caspase-3 activation, neutrophils differentiated for 4 days and washed as described above were cultured in the absence of SCF as indicated. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde and permeabilized with 1% Saponin (Sigma). Staining was performed with rabbit anti-active caspase-3 (BD Pharmingen) in PBS/0.5% BSA for 40 min, followed by incubation with secondary donkey anti-rabbit–FITC or anti-rabbit–Cy5 (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany) for 30 min, and samples were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Analysis of neutrophil effector functions

Hoxb8 neutrophils were differentiated for 4 days and deprived of SCF for up to 48 h, as described for apoptosis assays. For analysis of phagocytic capacity, RFP- or GFP-expressing E. coli (DH5α) were grown overnight in liquid culture, harvested, washed with PBS, and the optical density of the suspension at 600 nm was adjusted to 2.0. Neutrophils and E. coli were co-incubated at a bacteria/cell ratio of 200 : 1 at 37°C for the indicated time periods. After extensive washing, cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. In case of adherence controls, cells were incubated at 4°C. For analysis of oxidative burst, reactive-oxygen species production was assessed by oxidation of dihydrorhodamine. Neutrophils (4 × 105) were stimulated with 5 μM PMA (Sigma) or with FITC-labeled pneumococci (bacteria/cell ratio 500 : 1), then 2 mM dihydrorhodamine (Sigma) was added and incubation was continued for another 30 min. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. For the measurement of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 production, neutrophils were co-incubated with E. coli for 16 h (bacteria/cell ratio 200 : 1). Supernatants were harvested and cytokines were quantified using mouse tumor necrosis factorα and interleukin-6 ELISA kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

RNA extraction and quantification

Total RNA was extracted and transcribed into cDNA with commercial kits (Roche), following the manufacturer's instructions. Samples were analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR using the Light Cycler TaqMan Master Kit and the Universal Probe Library system (Roche). Relative expression of the gene of interest was normalized to β-actin reference gene expression.

Immunoblot analysis

Cells were harvested and immediately lysed in Laemmli buffer (3 × 106/50 μl). After separation of cell extracts by SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred onto PVDF membranes. Loading of equal cell numbers was confirmed by probing for GAPDH or Tubulin using specific antibodies (Millipore, Schwalbach, Germany; Sigma). Membranes were probed with antibodies against mouse Bim, Bcl-XL, Bcl-w, Bax (all from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverley, MA, USA), Noxa (Abcam, Cambridge ,UK), BH3-interacting domain death agonist, Puma (NT, ProSci, Poway, CA, USA), Bak (Millipore), Bcl-2 (BD Pharmingen), Mcl-1 (Rockland, Gilbertsville, PA, USA; Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA) or A1. Proteins were visualized using peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies against rabbit (Sigma), mouse, rat or hamster (all from Dianova) and an enhanced chemoluminescence detection system (GE Healthcare, Munich, Germany).

Acknowledgments

We thank Eva Wiedenbauer, Ilka Sührer and Petra Steinke for helpful assistance. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft, SFB 576 (to SK and GH) and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC) (to HH). SG was supported by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments (GSC-4, Spemann Graduate School). FG, EO and AV were supported by the postgraduate program, Molecular Cell Biology & Oncology (MCBO), funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF).

Glossary

- Bak

Bcl-2 homologous antagonist/killer

- Bax

Bcl-2-associated X protein

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma protein 2

- Bcl-XL

Bcl-2-like protein 1

- BH3

Bcl-2 homology domain

- Bid

BH3-interacting domain death agonist

- Bim

Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death

- GM-CSF

granuloyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- GSK3

Glycogen–synthase–kinase 3

- IL-3

Interleukin 3

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- Mcl-1

induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein

- PI

propidium iodide

- SCF

stem cell factor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- wt

wild type

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Cell Death and Differentiation website (http://www.nature.com/cdd)

Edited by H-U Simon

Supplementary Material

References

- Dale DC, Boxer L, Liles WC. The phagocytes: neutrophils and monocytes. Blood. 2008;112:935–945. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-077917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SG, Morrison RP. In situ analysis of the evolution of the primary immune response in murine Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2870–2879. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2870-2879.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Zandbergen G, Klinger M, Mueller A, Dannenberg S, Gebert A, Solbach W, et al. Cutting edge: neutrophil granulocyte serves as a vector for Leishmania entry into macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;173:6521–6525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Savill J. Resolution of inflammation: the beginning programs the end. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1191–1197. doi: 10.1038/ni1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J. Apoptosis in resolution of inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 1997;61:375–380. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright GE, Athens JW, Wintrobe MM. The kinetics of granulopoiesis in normal man. Blood. 1964;24:780–803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillay J, den Braber I, Vrisekoop N, Kwast LM, de Boer RJ, Borghans JA, et al. In vivo labeling with 2H2O reveals a human neutrophil lifespan of 5.4 days. Blood. 2010;116:625–627. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-259028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akgul C, Moulding DA, Edwards SW. Molecular control of neutrophil apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 2001;487:318–322. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo HR, Loison F. Constitutive neutrophil apoptosis: mechanisms and regulation. Am J Hematol. 2008;83:288–295. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koedel U, Frankenberg T, Kirschnek S, Obermaier B, Hacker H, Paul R, et al. Apoptosis is essential for neutrophil functional shutdown and determines tissue damage in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000461. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi A, Dixit VM. Death receptors: signaling and modulation. Science. 1998;281:1305–1308. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5381.1305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JM. Ways of dying: multiple pathways to apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2481–2495. doi: 10.1101/gad.1126903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecho K, Cohen PL. Fas ligand (gld)- and Fas (lpr)-deficient mice do not show alterations in the extravasation or apoptosis of inflammatory neutrophils. J Leukoc Biol. 1998;64:373–383. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villunger A, O'Reilly LA, Holler N, Adams J, Strasser A. Fas ligand, Bcl-2, granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase: regulators of distinct cell death and survival pathways in granulocytes. J Exp Med. 2000;192:647–658. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villunger A, Scott C, Bouillet P, Strasser A. Essential role for the BH3-only protein Bim but redundant roles for Bax, Bcl-2, and Bcl-w in the control of granulocyte survival. Blood. 2003;101:2393–2400. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GG, Calvo KR, Pasillas MP, Sykes DB, Hacker H, Kamps MP. Quantitative production of macrophages or neutrophils ex vivo using conditional Hoxb8. Nat Methods. 2006;3:287–293. doi: 10.1038/nmeth865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You H, Pellegrini M, Tsuchihara K, Yamamoto K, Hacker G, Erlacher M, et al. FOXO3a-dependent regulation of Puma in response to cytokine/growth factor withdrawal. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1657–1663. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parish IA, Rao S, Smyth GK, Juelich T, Denyer GS, Davey GM, et al. The molecular signature of CD8+ T cells undergoing deletional tolerance. Blood. 2009;113:4575–4585. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-185223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders A, Bouillet P, Puthalakath H, Xu Y, Tarlinton DM, Strasser A. Loss of the pro-apoptotic BH3-only Bcl-2 family member Bim inhibits BCR stimulation-induced apoptosis and deletion of autoreactive B cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:1119–1126. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntington ND, Puthalakath H, Gunn P, Naik E, Michalak EM, Smyth MJ, et al. Interleukin 15-mediated survival of natural killer cells is determined by interactions among Bim, Noxa and Mcl-1. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:856–863. doi: 10.1038/ni1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley J, Coffer PJ, Ham J. FOXO transcription factors directly activate bim gene expression and promote apoptosis in sympathetic neurons. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:613–622. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200303026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimer DA, Boyd K, Takeuchi O, Fisher JK, Zambetti GP, Opferman JT. Selective roles for antiapoptotic MCL-1 during granulocyte development and macrophage effector function. Blood. 2009;113:2805–2815. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-159145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis SN, Chen L, Dewson G, Wei A, Naik E, Fletcher JI, et al. Proapoptotic Bak is sequestered by Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL, but not Bcl-2, until displaced by BH3-only proteins. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1294–1305. doi: 10.1101/gad.1304105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurer U, Charvet C, Wagman AS, Dejardin E, Green DR. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 regulates mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis by destabilization of MCL-1. Mol Cell. 2006;21:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulding DA, Quayle JA, Hart CA, Edwards SW. Mcl-1 expression in human neutrophils: regulation by cytokines and correlation with cell survival. Blood. 1998;92:2495–2502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwickart M, Huang X, Lill JR, Liu J, Ferrando R, French DM, et al. Deubiquitinase USP9X stabilizes MCL1 and promotes tumour cell survival. Nature. 2010;463:103–107. doi: 10.1038/nature08646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart DP, Koss B, Bathina M, Perciavalle RM, Bisanz K, Opferman JT. Ubiquitin-independent degradation of antiapoptotic MCL-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:3099–3110. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01266-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer A, Kirschnek S, Häcker G. Inhibition of apoptosis can be accompanied by increased Bim levels. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1714–1716. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andina N, Conus S, Schneider EM, Fey MF, Simon HU. Induction of Bim limits cytokine-mediated prolonged survival of neutrophils. Cell Death Differ. 2009;16:1248–1255. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploner C, Rainer J, Niederegger H, Eduardoff M, Villunger A, Geley S, et al. The BCL2 rheostat in glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2008;22:370–377. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2405039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.