Abstract

Ebola virus (EboV) belongs to the Filoviridae family of viruses that causes severe and fatal hemhorragic fever. Infection by EboV involves fusion between the virus and host cell membranes mediated by the envelope glycoprotein GP2 of the virus. Similar to the envelope glycoproteins of other viruses, the central feature of the GP2 ectodomain postfusion structure is a six-helix bundle formed by the protein's N- and C-heptad repeat regions (NHR and CHR, respectively). Folding of this six-helix bundle provides the energetic driving force for membrane fusion; in other viruses, designed agents that disrupt formation of the six-helix bundle act as potent fusion inhibitors. To interrogate determinants of EboV GP2-mediated membrane fusion, we designed model proteins that consist of the NHR and CHR segments linked by short protein linkers. Circular dichroism and gel filtration studies indicate that these proteins adopt stable α-helical folds consistent with design. Thermal denaturation indicated that the GP2 six-helix bundle is highly stable at pH 5.3 (melting temperature, Tm, of 86.8 ± 2.0°C and van't Hoff enthalpy, ΔHvH, of −28.2 ± 1.0 kcal/mol) and comparable in stability to other viral membrane fusion six-helix bundles. We found that the stability of our designed α-helical bundle proteins was dependent on buffering conditions with increasing stability at lower pH. Small pH differences (5.3–6.1) had dramatic effects (ΔTm = 37°C) suggesting a mechanism for conformational control that is dependent on environmental pH. These results suggest a role for low pH in stabilizing six-helix bundle formation during the process of GP2-mediated viral membrane fusion.

Keywords: viral membrane fusion, protein design, protein folding, circular dichroism

Introduction

The transmembrane envelope glycoproteins of many viruses use simple α-helical bundle motifs to facilitate fusion between the virus and host membranes during infection.1–3 (Historically, envelope glycoproteins have been categorized according to structural features with α-helical bundle proteins comprising the so-called “class I” family.2) In the general model for membrane fusion, folding of a six-helix bundle by the glycoprotein ectodomain provides the driving force for bringing the two bilayers together.1–3 The prototypic six-helix bundle formed by the N- and C-heptad repeat (NHR and CHR) regions from the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) transmembrane envelope glycoprotein gp41 has been particularly instructive for understanding this mechanism (Fig. 1).4–6 The primary sequence of gp41 contains a hydrophobic N-terminal fusion peptide (FP), the ectodomain containing the NHR and CHR, and a transmembrane domain that anchors the glycoprotein to the virus. Following receptor binding by the surface glycoprotein (gp120), the FP of gp41 embeds in the membrane of the host cell giving rise to a transient trimeric intermediate known as the “extended” or “prehairpin” intermediate that spans both the virus and cell membranes and in which the NHR and CHR segments are exposed [Fig. 1(A)]. Next, folding of the NHR and CHR into the six-helix bundle forces the two anchored membranes into proximity, which promotes mixing and, ultimately, formation of a fusion pore. This process likely proceeds via a hemifusion intermediate, in which the outer leaflets are fused but the inner leaflets are not, and it is thought that the transition from this hemifusion intermediate to the fusion pore represents the rate-limiting step during entry.1 Transmembrane glycoproteins from other viruses such as Ebola virus (EboV) (GP2) and influenza A virus (HA2) have similar architectural features and by analogy are thought to promote membrane fusion via similar mechanisms.1–3,7–9 For EboV, experimental evidence suggests that GP2 also forms an extended intermediate that ultimately collapses into the six-helix bundle and that degradation of the surface subunit (GP1) by host endosomal proteases cathepsins L and B (CatL and CatB) is an obligatory step in the pathway toward this intermediate.7–12 However, the precise molecular events that lead to triggering of the envelope spike to form the extended intermediate are still under investigation.

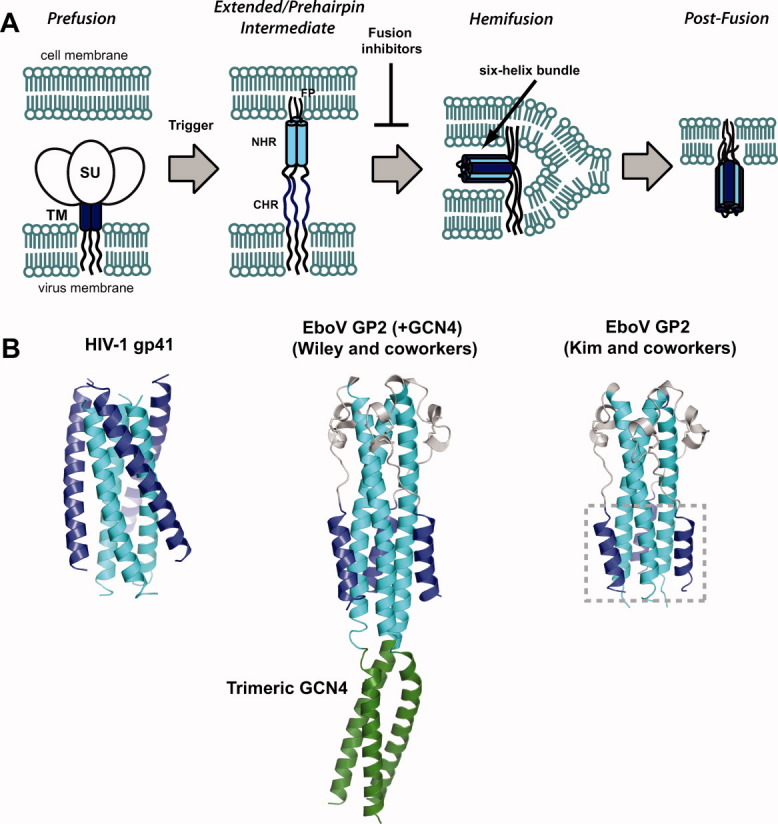

Figure 1.

A: General mechanism of viral membrane fusion catalyzed by α-helical bundle containing ectodomains. In both HIV-1 and EboV, the prefusion assembly consists of a dimer of trimers containing a surface subunit (SU, gp120 for HIV-1 and GP1 for EboV) and the transmembrane subunit that contains the NHR and CHR regions (TM, gp41 for HIV-1 and GP2 for EboV). In both cases a “trigger” leads to insertion of the N-terminal fusion peptide (FP) into the cell membrane resulting in the extended or prehairpin intermediate in which the NHR (cyan) and CHR (blue) are exposed to the environment. Folding of the six-helix bundle juxtaposes the two membranes and ultimately leads to their coalescence. Agents that bind the extended/prehairpin intermediate and prevent six-helix bundle formation have been shown to act as potent antiviral agents in HIV-1 (fusion inhibitors). B: Postfusion conformations of HIV-1 gp41 (PDB ID 1AIK) and EboV GP2 ectodomains solved by the Wiley (PDB ID 1EBO) and Kim groups (PDB ID 2EBO). The NHR and CHR elements are colored as in panel A; the Wiley GP2 construct contained an N-terminal trimeric GCN4 segment which is shown in green. The six-helix bundle of EboV GP2 is boxed on the structure reported by Kim and coworkers.

Crystal structures of the EboV GP2 ectodomain in the putative postfusion conformation were reported independently by the Kim and Wiley groups8,9 [Fig. 1(B)]. The structure described by Kim and coworkers9 was of a protease stable 74-residue fragment encompassing residues 557–630 (Zaire ebolavirus numbering, “Ebo-74”). The structure reported by Wiley and coworkers8 contained residues 552–650 of the ectodomain linked to a N-terminal trimeric GCN4 coiled-coil domain to promote solubility and stability (pIIGp2(552–650)). The GP2 ectodomain regions in these two structures were in good agreement and revealed several unique features of the α-helical bundle. The EboV GP2 six-helix bundle is much shorter than that of HIV-1 gp41, consisting of segments containing just three α-helical turns each in the NHR and CHR regions compared to seven turns for these regions in gp41. The region linking the NHR and CHR in GP2 contains a short helix-turn-helix motif that is stabilized by an intramolecular disulfide bond. Interestingly, this motif is structurally similar to that found in the moloney murine leukemia virus (MoMLV) glycoprotein postfusion core despite the fact that these viruses are not phylogenetically related.8,9,13 Sequence homology suggests that analogous regions in the envelope glycoproteins of avian sarcoma/leukosis virus (ASLV) and human T-cell leukemia virus type I (HTLV-1) adopt similar structures, and mutational studies suggest that a histidine residue in this region plays a role in pH-dependent ASLV viral entry.14 In EboV GP2, the helix-turn-helix motif appears to contribute to overall stability as the native disulfide bond pairing is required for high thermostability.9 Another feature of EboV GP2 is the presence of a “stutter” in the heptad repeat pattern in the NHR core, noted by both the Kim and Wiley groups. Typical α-helical bundle proteins contain a characteristic abcdefg repeat where a and d positions are occupied by hydrophobic residues (the 3-4 repeat).15 In the NHR region of GP2, there is a stutter in this hydrophobic repeat at position T565 that results in a 3-4-4-3 repeat pattern; a similar stutter exists at the N-terminal end of the low-pH induced influenza A virus HA2 coiled-coil.16 Finally, the central NHR coiled-coil contains an anion binding pocket that also appears to contribute to folding stability. These features make the EboV GP2 α-helical bundle an interesting system to study in the context of factors that are required to drive membrane fusion.

The evidence for the extended intermediate in HIV-1 gp41 was obtained from designed peptides and proteins that bound the extended intermediate and prevented rearrangement to the six-helix bundle [“fusion inhibitors,” Fig. 1(A)].3,4 Proteins, peptides, and small molecules that bind protein mimics of the HIV-1 gp41 extended intermediate have antiviral activity and have been exploited for design of viral entry inhibitors.17–20 Furthermore, appropriately designed protein mimics of the gp41 extended intermediate serve as targets for neutralizing antibodies and thus have potential as immunogens for vaccine discovery.21–24 In theory, similar approaches could be adopted for EboV GP2, given the similarity in their proposed fusion mechanisms.25 Our goal was to design protein mimics of the α-helical bundle segment of EboV GP2 that could be used as model systems to study folding stability and potentially aid in development of inhibitors of EboV membrane fusion. To this end, we prepared model proteins consisting of the alternating NHR and CHR segments from EboV GP2 linked by short, flexible loops. Biophysical characterization reveals that these proteins adopt stable α-helical structures consistent with their design. Further analysis provided interesting insights into factors that influence stability of the EboV GP2 six-helix bundle.

Results and Discussion

Design of protein mimics of the EboV GP2 α-helical bundle

We sought to analyze the folding properties of the α-helical bundle segment of the EboV GP2 ectodomain. The GP2 postfusion structure is distinct from that of HIV-1 gp41 in that GP2 contains a relatively small six-helix bundle segment but a long, triple stranded core NHR coiled-coil; much of the GP2 postfusion outer layer consists of the helix-turn-helix and loop segments [the six-helix bundle is boxed in Fig. 1(B)].8,9 By contrast, the long, central NHR trimer of HIV-1 gp41 is surrounded by CHR α-helices of essentially equal length.5,6,26–28 Previously, Wiley and coworkers29 performed denaturation studies with pIIGp2(552–650) and found it to be highly thermostable (complete unfolding was not observed on heating to 98°C at pH 8). Kim and coworkers9 performed denaturation studies with two GP2 ectodomain constructs, a larger 95-residue construct containing essentially the entire GP2 ectodomain (“Ebo-95”), and the protease-resistant Ebo-74. These proteins were also found to be thermostable (thermal midpoint, Tm, of 88°C at pH 7.2 for Ebo-95 and 77°C at pH 4.5 for Ebo-74). We wondered what contributions were provided by the GP2 six-helix bundle segment alone (i.e., in the absence of the helix-turn-helix and loop segments). Analysis of folding energetics for six-helix bundle constructs from HIV-1 and simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) gp41 has previously been performed using short hairpin proteins (i.e., a single NHR and a single CHR segment linked by a short linker that form a trimer).27,28 However, such proteins typically display concentration-dependent behavior and therefore aggregation complicates thermodynamic analysis. We reasoned that a single chain construct consisting of the EboV GP2 α-helical NHR and CHR segments alone would provide a useful system to examine folding stability of the GP2 six-helix bundle.

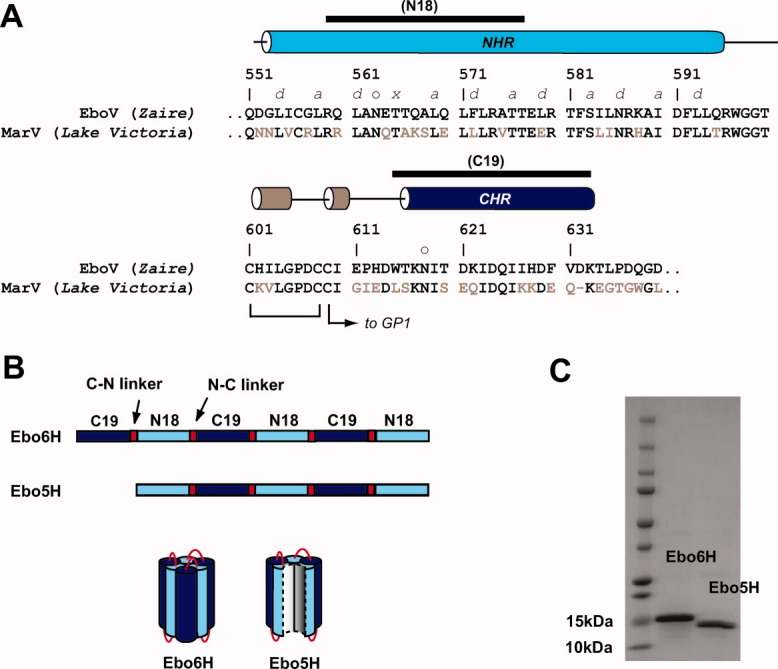

We designed two proteins consisting of alternating NHR and CHR segments of Zaire ebolavirus GP2: “Ebo6H” and “Ebo5H” (Fig. 2). Ebo6H contains the segments each of the CHR region encompassing residues 615–633 (this segment is referred to as “C19”) linked to the NHR segment consisting of residues 559–576 (“N18,” which includes the unusual heptad repeat stutter) via short, flexible protein linkers. When properly folded, this polypeptide is predicted to adopt a six-helix bundle that mimics that of the GP2 postfusion core.8,9 Ebo5H is similar to Ebo6H but lacks one of the CHR regions. When folded, Ebo5H should adopt a structure similar to that of Ebo6H but lacking a single CHR segment. Comparison of stabilities for Ebo5H and Ebo6H should therefore provide insight into contribution of stability of a single CHR segment. In addition, similar “5-Helix” constructs based on HIV-1 gp41 have been used as entry inhibitors and mimics of the extended intermediate.18–24 Therefore, Ebo5H may be useful for development of EboV entry inhibitors. Ebo6H and Ebo5H proteins containing hexahistidine tags were expressed in E. coli, purified from inclusion bodies, and then subjected to refolding conditions. Both proteins were obtained in good yield and purity [Fig. 1(C)].

Figure 2.

Protein design of mimics of the EboV GP2 α-helical bundle. A: Sequence of GP2 ectodomain from EboV (Zaire strain). The regions corresponding to the NHR, CHR, and helix-turn-helix regions are indicated with cylinders whose colors match the structural elements depicted in Figure 1(B). The helix-turn-helix region contains three cysteines, two of which form an intramolecular disulfide bond and the third tethers GP1 to GP2. The ectodomain contains two glycosylation sites, these are indicated with an “o.” The T565 residue that gives rise to the unusual 3-4-4-3 hydrophobic stutter in the NHR is indicated with an “×,” other residues in the NHR that form core positions are denoted a and d. For comparison, the sequence of the related marburgvirus (MarV, Lake Victoria strain) is also shown; conserved residues are colored black. The segments used in design of Ebo6H and Ebo5H (N18 and C19) are indicated with a black bar above. B: Schematic representation of Ebo6H and Ebo5H design. Ebo6H consists of alternating C19 and N18 segments linked by short linkers (C–N linker sequence –GSSGG– and N–C linker sequence –GGSGG–). Ebo5H is similar but lacking the first C19 sequence. C: SDS-PAGE analysis of purified, refolded Ebo6H and Ebo5H. In both cases, a single band was observed of expected molecular weight (16 kDa for Ebo6H and 15 kDa for Ebo5H).

Ebo6H and Ebo5H adopt stable α-helical conformations

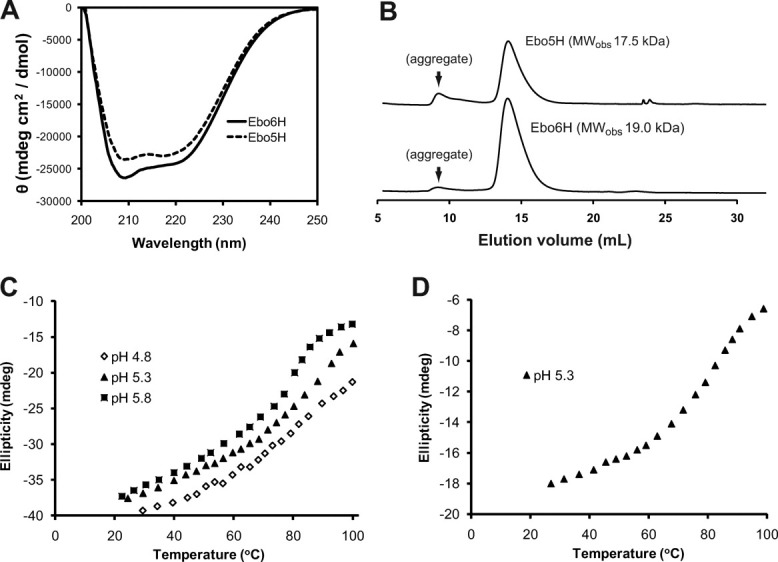

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra for Ebo6H (2 μM) and Ebo5H (0.4 μM) in 20 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.3) exhibited double minima at 208 and 222 nm, characteristic of α-helical secondary structure and consistent with the intended design [Fig. 3(A)]. The CD signature (as judged by ratio of signal intensity at 208 and 222 nm) for both proteins was invariant across a 0.2–10 μM concentration range, indicating that α-helix formation was not driven by aggregation. Gel filtration analysis at mid-micromolar protein concentrations (80 μM for Ebo6H and 50 μM for Ebo5H) yielded molecular weight estimates consistent with monomer for each protein, although a small amount of aggregate was observed in both cases [Fig. 3(B)]. Ebo6H underwent a cooperative unfolding transition on heating when monitored by CD at 222 nm (Fig. 3) with Tm of 86.8 ± 2.0°C at pH 5.3 and 77.8 ± 1.6°C at pH 5.8. Ebo5H was less stable than Ebo6H at pH 5.3 (Tm = 80.6 ± 0.7°C); therefore, the additional CHR segment in Ebo6H provided 6.2°C of thermal stability under these conditions. The reversibility of unfolding was confirmed by cooling heated samples to room temperature over 5 min; we found the intensity of the 222 nm signal returned to initial values during this process (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Characterization of Ebo6H and Ebo5H. A: CD spectra of Ebo6H and Ebo5H in 20 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.3. B: Gel filtration analysis under similar conditions. Observed molecular weight estimates (19.0 and 17.5 kDa for Ebo6H and Ebo5H, respectively) were consistent with monomer in each case. A small amount of aggregate was observed in each case. Thermal denaturation of Ebo6H (C, pH 5.8, 5.3, and 4.8) and Ebo5H (D, pH 5.3).

To obtain insight into thermodynamic parameters of unfolding, we performed van't Hoff analysis of the thermal denaturation data.30–32 Assuming a simple two-state unfolding model ( ) with no intermediates, the equilibrium constant for the unfolding reaction (Kunf) is related to the fraction unfolded (Funf) by Eq. (1).

) with no intermediates, the equilibrium constant for the unfolding reaction (Kunf) is related to the fraction unfolded (Funf) by Eq. (1).

| (1) |

The van't Hoff enthalpy (ΔHvH) can be derived from nonlinear regression of Kunf as a function of temperature (T) in accordance with Eq. (2) (where R is the gas constant).

| (2) |

Although ΔHvH does not provide direct information about the free energy of unfolding (ΔGunf), it nonetheless provides a rough parameter to assess folding stability. This analysis yielded ΔHvH of −28.2 ± 1.0 kcal/mol for Ebo6H and −27.6 ± 0.4 kcal/mol for Ebo5H at pH 5.3. These values are lower than unfolding enthalpies obtained by differential scanning calorimetry of model six-helix bundle proteins of SIV gp41 (ΔHunf = −42.3 kcal/mol).28 The SIV gp41 six-helix bundle segment is much longer than that of EboV GP2; therefore, it is not surprising that the unfolding enthalpy of SIV gp41 is larger than that of EboV GP2.

Effects of pH on stability

The envelope glycoproteins of many viruses that enter via the endosome undergo large structural transitions on exposure to acidic pH.1–3,16,33–37 These pH-dependent conformational changes are generally thought to control timing of the membrane fusion reaction such that it occurs only in endosomal compartments. For example, low pH triggers dissociation of the surface subunit (HA1) and HA2 subunits of influenza and extension of the central HA2 coiled-coil.1,3 A pH-dependent coil-to-helix transition in the midsection of the HA2 coiled-coil effectively jackknifes the N-terminal FP from the center of the envelope spike out toward the cell membrane.16,33,34 This rearrangement projects the FP into the cell membrane, leading to the extended intermediate. In the envelope glycorproteins of viruses such as alphaviruses and flaviriruses that contain mostly β-sheet structures (the “class II” envelope glycoproteins), similar pH effects destabilize the inactive prefusion conformation and promote oligomerization of fusion-active components.35,37 In EboV entry, proteolytic disassembly of GP1 by CatL and CatB, whose optimal catalytic activity is known to be at pH ∼5, is an essential step in early infection events.10,11 However, pH-dependent structural transitions have not been reported for GP1 or the GP2 ectodomain. Very recently, Gregory et al.38 demonstrated that the GP2 fusion loop undergoes pH-dependent conformational changes that promote fusogenic activity.

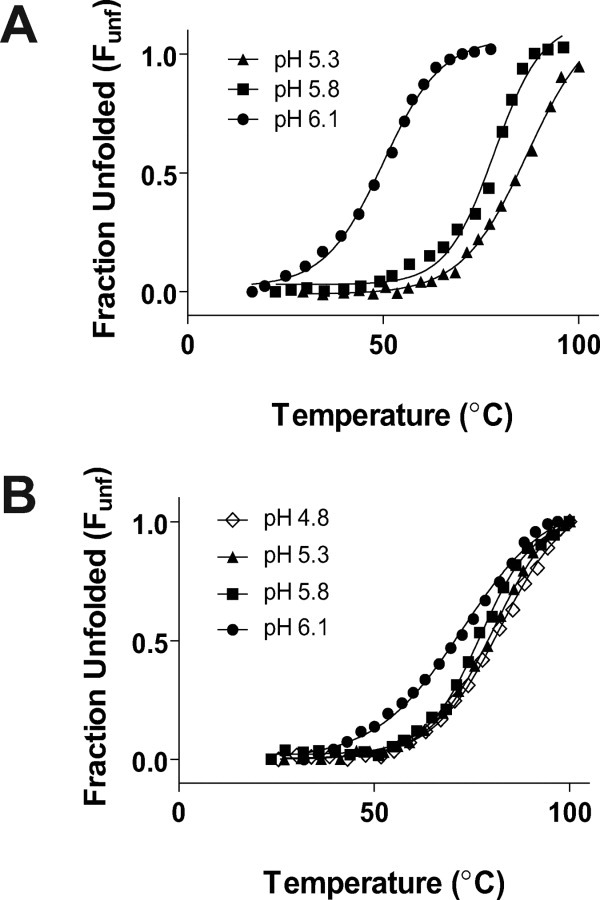

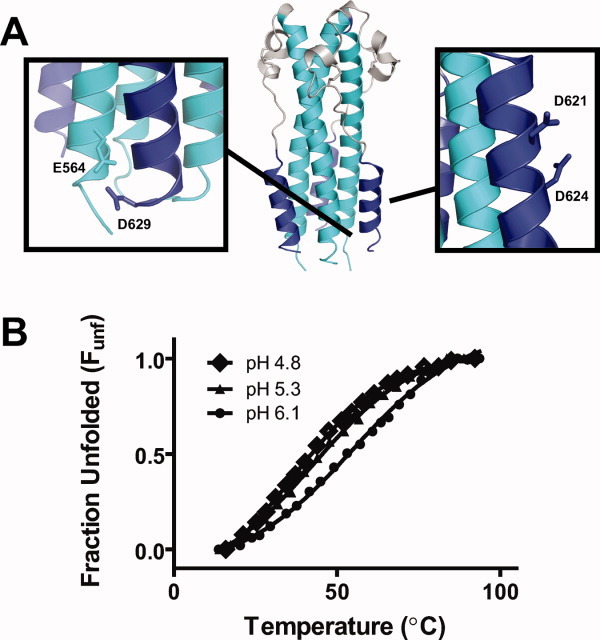

We determined the effect of pH on α-helical bundle stability of Ebo6H and Ebo5H by performing spectroscopic analysis under various buffer conditions. In conditions above pH 6.5, both proteins were poorly behaved and prone to aggregation. However, in range of pH 4.8–6.1, we found that both proteins retained their well-behaved, native-like properties. We performed thermal denaturation of Ebo6H and Ebo5H under several buffering conditions and found that the Tm was lower at higher pH for both proteins (Fig. 4 and Table I). The folding stability of small, globular proteins can be significantly influenced by pH; however, most proteins are most stably folded at neutral (physiologic) pH and become less stable in conditions below pH 6 (converse to the behavior observed here).39 The effects of pH on Tm were most pronounced in Ebo6H, where the Tm differed by 37°C between pH 5.2 (Tm = 86.8 ± 2.0°C) and pH 6.1 (Tm = 49.8 ± 1.1°C), corresponding to a ΔΔHvH of 7.8 kcal/mol over this range. In addition, heating to 100°C at pH 4.8 did not result in complete unfolding of Ebo6H [Fig. 3(C)]. Similar stability effects were observed for Ebo5H although they were less dramatic. The Tm values ranged from 82.2 ± 1.2°C at pH 4.8 to 72.6 ± 1.9°C at pH 6.1; this corresponded to a ΔΔHvH of 9.6 kcal/mol over this range. Both pIIGP2(552–650), the Wiley construct, and Ebo-95, the longer of the two Kim constructs, had high thermostability at neutral pH or higher.9,29 However, the shorter Ebo-74 construct was crystallized and characterized by CD at pH 4.5–4.6.9 Ebo6H and Ebo5H contain even less of the ectodomain than does Ebo-74, therefore the α-helical stability of shorter constructs may be more sensitive to environmental pH.

Figure 4.

Thermal denaturation of Ebo6H and Ebo5H under various buffering conditions. Corresponding Tm and ΔHvH values are listed in Table I.

Table I.

Folding and Stability of Ebo6H and Ebo5H Under Various Buffering Conditions

| Buffering condition | Tm (°C)a | ΔHvH (kcal/mol)a |

|---|---|---|

| Ebo6H | ||

| 20 mM NaOAc, pH 5.3 | 86.8 ± 2.0 | −28.2 ± 1.0 |

| 20 mM NaOAc, pH 5.8 | 77.8 ± 1.6 | −24.0 ± 0.4 |

| 20 mM NaHPO4, pH 6.1 | 49.8 ± 1.1 | −20.4 ± 0.2 |

| Ebo5H | ||

| 20 mM NaOAc, pH 4.8 | 82.2 ± 1.2 | −27.7 ± 0.6 |

| 20 mM NaOAc, pH 5.3 | 80.6 ± 0.7 | −27.6 ± 0.4 |

| 20 mM NaOAc, pH 5.8 | 77.2 ± 0.8 | −28.9 ± 0.3 |

| 20 mM NaHPO4, pH 6.1 | 72.6 ± 1.9 | −18.1 ± 0.2 |

Errors listed here represent 95% confidence interval from data fitting.

An examination of the six-helix bundle segment of the GP2 postfusion structure suggests that two side chain–side chain ionic interactions may be responsible for this pH-dependent behavior. On the CHR α-helix, an intrahelical i → i + 3 interaction between D621 and D624 could destabilize CHR α-helix formation at neutral pH due to repulsion between the carboxylate anions [Fig. 5(A)]. In other short α-helical bundle systems, overall folding stability can be greatly influenced by propensity of individual segments to adopt α-helical fold.40 Electrostatic i → i + 3 interactions can strongly influence α-helix formation and therefore α-helical bundle formation in systems containing segments as short as the GP2 CHR (three α-helical turns).41,42 In addition, a repulsive interaction between E564 of the NHR and D629 of the CHR may disrupt interhelical association at neutral pH [Fig. 5(A)]. To test this hypothesis, we prepared an Ebo6H variant with the mutations D621N, D624N, and D629N on the CHR segments, and E564Q on the NHR segments (“Ebo6H-QNNN”). As Ebo6H contains a total of three NHR and CHR segments each, the GP2 NHR/CHR segments of Ebo6H-QNNN have 12 total substitutions relative to the analogous segments in Ebo6H. We found Ebo6H-QNNN to be α-helical by CD; thermal denaturation indicates that the Tms were similar at pH 4.8 and 5.3 [43.1 ± 0.9°C and 46.2 ± 1.0°C, respectively, Fig. 5(B)] but was lower than Ebo6H under these conditions. Furthermore, unfolding transition for Ebo6H-QNNN was much broader that of Ebo6H. These differences may reflect the fact that aspargine has lower α-helical propensity in coiled-coil proteins than does aspartic acid and therefore the nine Asp → Asn substitutions in the GP2 NHR/CHR regions have a cumulative effect on folding stability.40 Ebo6H-QNNN had higher stability at pH 6.1 (Tm = 53.5 ± 1.1°C) than at the lower pHs. This behavior contrasts with that of Ebo6H, which was significantly more stable under acidic conditions than at pH 6.1. Furthermore, Ebo6H-QNNN had 3.7°C higher Tm than did Ebo6H at pH 6.1, indicating that the α-helical fold of Ebo6H-QNNN is less sensitive to conditions near neutral pH. In addition, Ebo6H was much less stable than Ebo5H at pH 6.1 (Tms of 49.8 ± 1.1°C for Ebo6H and 72.6 ± 1.9°C for Ebo5H) suggesting that repulsive interactions within the additional CHR segment in Ebo6H substantially affects global α-helical bundle fold stability under these conditions. Taken together, these results suggest that anionic side chain–side chain interactions mediate pH-dependent α-helical bundle stability in Ebo6H.

Figure 5.

A: Side chain–side chain interactions that may contribute to pH-dependent α-helical fold stability. B: Thermal denaturation of Ebo6H-QNNN in 20 mM acetate at pH 4.8, 5.3, and 6.1. The Tms were 43.1 ± 0.9, 46.2 ± 1.0, and 53.5 ± 1.1°C, respectively.

Both Ebo6H and Ebo5H were purified with two hexahistidine tags, one at each terminus. As the pKa of the imidazole side chain is approximately 6, it is possible that the histidine tags contribute to the pH-sensitive behavior observed here. Unfortunately, attempts to isolate Ebo6H variants containing fewer than two histidine tags were unsuccessful and therefore we could not directly compare thermostability with and without these segments. However, increased cationic charge density by protonation of histidine tags at the N- and C-terminal ends is predicted to disfavor folding due to repulsion between the N- and C-terminal ends in a compact, globular state. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that the histidine tags play a role in the pH-dependent stability of Ebo6H and Ebo5H, it seems unlikely that the observed effects could be explained by these regions alone. Although the pH range in which we see the most dramatic changes in Ebo6H and Ebo5H structural stability (pH 4.8–6.1) falls above the pKa of carboxylic acid side chains (pH ∼4), it is not unusual for side chain pKas to be elevated in situations where their deprotonation disfavors formation of a highly stable fold.43–46 Such phenomena have been documented in other α-helical bundle proteins as well.43–46

Conclusions and implications for membrane fusion

Our analysis with Ebo6H and Ebo5H provide new insight into folding and stability for the six-helix bundle of EboV GP2. We found that Ebo6H, a designed protein mimic of the GP2 α-helical bundle, adopts a highly thermostable fold. Among class I viral membrane fusion glycoproteins, the central ectodomain core NHR trimeric coiled-coil of EboV GP2 and analogous proteins from the structurally related MarV, MoMLV HTLV-1, and ASLV are relatively short in length.1,2,14 The core NHR trimers of influenza A virus HA2 and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus S2 are longer than EboV GP2, but these ectodomains also contain loop or non-α-helical segments and therefore their six-helix bundle segments are also small in comparison to HIV-1 gp41.3 Our studies demonstrate that even the small α-helical bundle of EboV GP2 (consisting of α-helical segments containing just three to four turns) provides a large amount of energy to overcome barriers associated with membrane fusion. Furthermore, we found that Ebo5H was less stable than Ebo6H (ΔTm = 6.2°C at pH 5.3) thereby demonstrating that a single CHR segment can enhance thermostability of the α-helical bundle by a significant amount. Similar designed 5-Helix proteins based on HIV-1 gp41 act as potent inhibitors of entry by sequestering the CHR segment on the extended intermediate during infection.18–24 We tested Ebo5H for entry inhibition using a recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus containing the EboV GP in place of the native envelope glycoprotein (VSV-GP). We found that Ebo5H was not able to inhibit infection of VSV-GP (Miller and Chandran, unpublished results), although this result is likely because the extended intermediate is exposed only in the endosome.7 We recently reported that antiviral activity of peptides corresponding to the GP2 CHR segment (C-peptides) can be enhanced by inclusion of an endosome-targeting sequence.25

Further studies indicated that the folding stabilities of Ebo6H and Ebo5H were pH sensitive. The α-helical bundle stability as judged by Tm and ΔHvH values was significantly lower in buffering conditions closer to neutral pH than in acidic conditions. Analysis with Ebo6H-QNNN suggested that anionic side chain–side chain interactions mediate this pH-dependent stability in Ebo6H; this feature of the GP2 six-helix bundle may have implications in control of the fusion reaction. In the prevailing model for viral membrane fusion, it is thought that the transmembrane subunit is prevented from adopting the thermodynamically stable α-helical bundle structure by interactions with the surface subunit in the prefusion conformation.47,48 Triggering events cause dissociation of the surface subunit and releases constraints on the transmembrane subunit ectodomain, allowing the eventual formation of the α-helical bundle that drives membrane fusion (the “spring loaded clamp” model). In HIV-1 and influenza A virus, the events that trigger release of the transmembrane subunits (gp41 and HA2) from the prefusion conformation are well established. For HIV-1, where membrane fusion is thought to occur at the cellular surface, a conformational change in gp120 on CD4 and coreceptor binding induces its dissociation from the spike.49 In influenza A virus, which enters via the endosome, low pH destabilizes the prefusion conformation and leads to the extended intermediate.

A role for pH in structural transitions of GP1 or the GP2 ectodomain has not been established and the precise trigger for membrane fusion is still under investigation. Comparison of the NHR and CHR segments in the prefusion GP1–GP2 assembly demonstrates that the protein segment corresponding to the long α-helical NHR coiled-coil is interrupted into three shorter α-helices in the prefusion structure.7,12 Electron density for the CHR segments was not observed in the prefusion structure, suggesting that this region is dynamic.12 Recent mutational studies on the helix-turn-helix/loop segment of the ASLV transmembrane envelope glycoprotein (EnvA) have implicated a histidine residue in the pH dependence of EnvA-mediated viral entry.14 Mutation of residues in the analogous segment in EboV GP2 have an effect on viral entry but, in the absence of a fusion assay directed at the cell surface, it is not possible to determine whether these residues are involved in pH-dependent structural changes that promote membrane fusion.14 Furthermore, a recent report suggests that the fusion loop of GP2 also undergoes a conformational transition between pH 7 and 5.5 that activates fusogenic activity under the lower pH condition.38 The results presented here suggest that pH-dependent α-helical bundle stability could also play a role in controlling the timing of membrane fusion. At neutral pH, the six-helix bundle is less stable and therefore the prefusion conformation is preferred. However, once the virus particle is taken up into an endosome that undergoes acidification, the postfusion six-helix bundle becomes more stable and therefore the postfusion state becomes preferred. The pH range in which we see the most significant changes in stability (pH 4.8–6.1) corresponds to the pH of late endosomes and correlates closely with the optimal pH for acid-dependent cysteine cathepsin activity. This proposed mechanism for conformational control is distinct from that of other endosomal viruses: in most cases, the pH change destabilizes the prefusion conformation rather than stabilizing the postfusion conformation.1–4 Further studies will be required to determine if this pH-dependent stability is relevant in the virus and whether other pH-induced structural changes occur.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression, purification, and refolding of Ebo5H and Ebo6H

Synthetic DNA encoding the genes for Ebo6H and Ebo5H codon optimized for E. coli were obtained from a commercial supplier (DNA 2.0, Menlo Park, CA) and cloned into pET28 using the NdeI and XhoI restriction sites. Constructs of Ebo5H were prepared containing His6 tags at the N-terminus, at the C-terminus, or at both the N- and C-termini and protein expression assessed in small-scale cultures. We found that the construct containing His6 tags at both the N- and C-termini was most abundantly expressed and therefore we used this format for large-scale expression of both Ebo6H and Ebo5H. E. coli BL21(DE3) (Invitrogen, Madison, WI) harboring expression plasmids for Ebo6H or Ebo5H were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C to an optical density (600 nm, OD600) of 0.6 and then expression of the protein was induced by addition of 1 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cells were incubated overnight at 37°C, harvested by centrifugation, and then lysed in a French Pressure cell. The insoluble fraction was separated by ultracentrifugation, dissolved in 6 M guanidine HCl (GdnHCl) and applied to nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) resin (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The resin was washed with 10 column volumes of 15 mM imidazole containing 6 M GdnHCl and the protein was eluted with 250 mM imidazole containing 6 M GdnHCl. The fractions containing purified protein were pooled and refolded by two-step dialysis first into 100 mM glycine HCl (pH 3.5), then into 20 mM NaOAc pH 5.3 containing 150 mM NaCl. Precipitated material was removed by centrifugation and the protein solution was used immediately for analysis or flash frozen and stored at −80°C. Preparation of Ebo6H-QNNN was similar.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy

Protein samples were prepared in the appropriate buffer and measurements were performed on a Jasco J-815 spectrometer with a 1 cm quartz cuvette. Protein concentrations ranged from 0.4 to 10 μM as determined by absorbance at 280 nm. CD wavelength scans were obtained with a 0.2 or 1 nm step size and a 2 s averaging time. The signal was corrected for blank and then converted to mean residue ellipticity (θ). Thermal denaturation data were obtained with a 3°C step size and 1 min equilibration at each temperature. The raw ellipticity signal was corrected for folded and unfolded baselines and then nonlinear least squares regression was performed using a standard four-parameter logistic equation. The Tm values were derived from the inflection point of the curve. For van't Hoff analysis, the baseline-corrected ellipticity was converted to Funf and then Kunf was calculated at each temperature (in °K) according to Eq. (1). Nonlinear least-squares regression of a Kunf versus T curve was then performed in accordance with Eq. (2) to obtain ΔHvH.

Gel filtration analysis

Analysis was performed on a Sephadex S75 column (10/300) at 4°C in 20 mM NaOAc pH 5.3 containing 150 mM NaCl. Protein samples were loaded at concentrations of 50–80 μM and elution was monitored by absorbance at 280 nm. Both Ebo6H and Ebo5H eluted as a single peak. Protein molecular weight standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) were used to generate a standard curve and the Ebo6H and Ebo5H molecular weights were estimated by elution volume.

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael Brenowitz and Margaret Kielian (Albert Einstein College of Medicine) for helpful discussions and critical reading of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:690–698. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White JM, Delos SE, Brecher M, Schornberg K. Structures and mechanisms of viral membrane fusion proteins: multiple variations on a common theme. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;43:189–219. doi: 10.1080/10409230802058320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eckert DM, Kim PS. Mechanisms of viral membrane fusion and its inhibition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:777–810. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan DC, Kim PS. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell. 1998;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee JE, Saphire EO. Neutralizing ebolavirus: structural insights into the envelope glycoprotein and antibodies targeted against it. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2009;19:408–417. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissenhorn W, Carfi A, Lee KH, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Crystal structure of the Ebola virus membrane fusion subunit, GP2, from the envelope glycoprotein ectodomain. Mol Cell. 1998;2:605–616. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malashkevich VN, Schneider BJ, McNally ML, Mihollen MA, Pang JX, Kim PS. Core structure of the envelope glycoprotein GP2 from Ebola virus at 1.9 Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2662–2667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chandran K, Sullivan NJ, Felbor U, Whelan SP, Cunningham JM. Endosomal proteolysis of the Ebola virus glycoprotein is necessary for infection. Science. 2005;308:1643–1645. doi: 10.1126/science.1110656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schornberg K, Matsuyama S, Kabsch K, Delos S, Bouton A, White J. Role of endosomal cathepsins in entry mediated by the Ebola virus glycoprotein. J Virol. 2006;80:4174–4178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.8.4174-4178.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JE, Fusco ML, Hessell AJ, Oswald WB, Burton DR, Saphire EO. Structure of the Ebola virus glycoprotein bound to an antibody from a human survivor. Nature. 2008;454:177–182. doi: 10.1038/nature07082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fass D, Harrison SC, Kim PS. Retrovirus envelope domain at 1.7 Å resolution. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:465–469. doi: 10.1038/nsb0596-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delos SE, La B, Gilmartin A, White JM. Studies of the “chain reversal regions” of the Avian Sarcoma/Leukosis Virus (ASLV) and Ebolavirus fusion proteins: analogous residues are important, and a His residue unique to EnvA affects the pH dependence of ASLV entry. J Virol. 2010;84:5687–5694. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02583-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woolfson DN. The design of coiled-coil structures and assemblies. Adv Protein Chem. 2005;70:79–112. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(05)70004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bullough PA, Hughson FM, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of the influenza haemagllutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckert DM, Malashkevich VN, Hong LH, Carr PA, Kim PS. Inhibiting HIV-1 entry: discovery of D-peptide inhibitors that target the gp41 coiled-coil pocket. Cell. 1999;99:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Root MJ, Kay MS, Kim PS. Protein design of an HIV-1 entry inhibitor. Science. 2001;291:884–888. doi: 10.1126/science.1057453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frey G, Rits-Volloch S, Zhang XQ, Schooley RT, Chen B, Harrison SC. Small molecules that bind the inner core of gp41 and inhibit HIV envelope-mediated fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13938–13943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601036103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steger HK, Root MJ. Kinetic dependence to HIV-1 entry inhibition. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25813–25821. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601457200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luftig MA, Mattu M, Di Giovine P, Geleziunas R, Hrin R, Barbato G, Bianchi E, Miller MD, Pessi A, Carfi A. Structural basis for HIV-1 neutralization by a gp41 fusion intermediate-directed antibody. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:740–747. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller MD, Geleziunas R, Bianchi E, Lennard S, Hrin R, Zhang H, Lu M, An Z, Ingallinella P, Finotto M, Mattu M, Finnefrock AC, Bramhill D, Cook J, Eckert DM, Hampton R, Patel M, Jarantow S, Joyce J, Ciliberto G, Cortese R, Lu P, Strohl W, Schleif W, McElhaugh M, Lane S, Lloyd C, Lowe D, Osbourn J, Vaughan T, Emini E, Barbato G, Kim PS, Hazuda DJ, Shiver JW, Pessi A. A human monoclonal antibody neutralizes diverse HIV-1 isolates by binding a critical gp41 epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14759–14764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sabin C, Corti D, Buzon V, Seaman MS, Lutje Hulsik D, Hinz A, Vanzetta F, Agatic G, Silacci C, Mainetti L, Scarlatti G, Sallusto F, Weiss R, Lanzavecchia A, Weissenhorn W. Crystal structure and size-dependent neutralization properties of HK20, a human monoclonal antibody binding to the highly conserved heptad repeat 1 of gp41. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001195. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustchina E, Li M, Louis JM, Anderson DE, Lloyd J, Frisch C, Bewley CA, Gustchina A, Wlodawer A, Clore GM. Structural basis of HIV-1 neutralization by affinity matured Fabs directed against the internal trimeric coiled-coil of gp41. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001182. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller EH, Harrison JS, Radoshitzky SR, Higgins CD, Chi X, Dong L, Kuhn JH, Bavari S, Lai JR, Chandran K. Inhibition of Ebola virus entry by a C-peptide targeted to endosomes. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15854–15861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.207084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frey G, Chen J, Rits-Volloch S, Freeman MM, Zolla-Pazner S, Chen B. Distinct conformational states of HIV-1 gp41 are recognized by neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:1486–1491. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jelesarov I, Lu M. Thermodynamics of trimer-of-hairpins formation by the SIV gp41 envelope protein. J Mol Biol. 2001;307:637–656. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marti DN, Bjelić S, Lu M, Bosshard HR, Jelesarov I. Fast folding of the HIV-1 and SIV gp41 six-helix bundles. J Mol Biol. 2004;336:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weissenhorn W, Calder LJ, Wharton SA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. The central feature of the membrane fusion subunit from the Ebola virus glycoprotein is a long triple-stranded coiled coil. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6032–6036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greenfield NJ. Using circular dichroism collected as a function of temperature to determine the thermodynamics of protein unfolding and binding interactions. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2527–2535. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.John DM, Weeks KM. van't Hoff enthalpies without baselines. Protein Sci. 2000;9:1416–1419. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.7.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen DL, Pielak GJ. Baseline length and automated fitting of denaturation data. Protein Sci. 1998;7:1262–1263. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carr CM, Kim PS. A spring-loaded mechanism for the conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin. Cell. 1993;73:823–832. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90260-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson IA, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Structure of the haemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus at 3 Å resolution. Nature. 1981;289:366–373. doi: 10.1038/289366a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sánchez-San Martín C, Liu CY, Kielian M. Dealing with low pH: entry and exit of alphaviruses and flaviviruses. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fritz R, Stiasny K, Heinz FX. Identification of specific histidines as pH sensors in flavivirus membrane fusion. J Cell Biol. 2008;183:353–361. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qin ZL, Zheng Y, Kielian M. Role of conserved histidine residues in the low-pH dependence of the Semliki Forest virus fusion protein. J Virol. 2009;83:4670–4677. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02646-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gregory SM, Harada E, Liang B, Delos SE, White JM, Tamm LK. Structure and function of the complete internal fusion loop from Ebolavirus glycoprotein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:11211–11216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104760108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang AS, Honig B. On the pH dependence of protein stability. J Mol Biol. 1993;231:459–474. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Neil KT, DeGrado WF. A thermodynamic scale for the helix-forming tendencies of the commonly occurring amino acids. Science. 1990;250:646–651. doi: 10.1126/science.2237415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kohn WD, Cyril MK, Hodges RS. Protein destabilization by electrostatic repulsions in the two-stranded α-helical coiled-coil/leucine zipper. Protein Sci. 1995;4:237–250. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scholtz JM, Qian H, Robbins VH, Baldwin RL. The energetics of ion-pair and hydrogen-bonding interactions in a helical peptide. Biochemistry. 1993;32:9668–9676. doi: 10.1021/bi00088a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.O'shea EK, Lumb KJ, Kim PS. Peptide ‘Velcro’: design of a heterodimeric coiled-coil. Curr Biol. 1993;3:658–667. doi: 10.1016/0960-9822(93)90063-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O'shea EK, Rutkowski R, Kim PS. Mechanism of specificity in the Fos-Jun oncoprotein heterodimer. Cell. 1992;68:699–708. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lumb KJ, Kim PS. Measurement of interhelical electrostatic interactions in the GCN4 leucine zipper. Science. 1995;268:436–439. doi: 10.1126/science.7716550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lau WL, Degrado WF, Roder H. The effects of pK(a) tuning on the thermodynamics and kinetics of folding: design of a solvent-shielded carboxylate pair at the a-position of a coiled-coil. Biophys J. 2010;99:2299–2308. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.07.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker D, Agard DA. Influenza hemagglutinkinetic control of protein function. Structure. 1994;2:907–910. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carr CM, Chaudhry C, Kim PS. Influenza hemagglutinin is spring-loaded by a metastable native conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14306–14313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen B, Vogan EM, Gong H, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC, Harrison SC. Structure of an unliganded simian immunodeficiency virus gp120 core. Nature. 2005;433:834–841. doi: 10.1038/nature03327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]