Abstract

Major depressive disorder (MDD) has been characterized by excessive default-network activation and connectivity with the subgenual cingulate. These hyper-connectivities are often interpreted as reflecting rumination, where MDDs perseverate on negative, self-referential thoughts. However, the relationship between connectivity and rumination has not been established. Furthermore, previous research has not examined how connectivity with the subgenual cingulate differs when individuals are engaged in a task or not. The purpose of the present study was to examine connectivity of the default network specifically in the subgenual cingulate both on- and off-task, and to examine the relationship between connectivity and rumination. Analyses using a seed-based connectivity approach revealed that MDDs show more neural functional connectivity between the posterior-cingulate cortex and the subgenual-cingulate cortex than healthy individuals during rest periods, but not during task engagement. Importantly, these rest-period connectivities correlated with behavioral measures of rumination and brooding, but not reflection.

Keywords: depression, rumination, default network, subgenual cingulate, functional magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Rumination is defined as ‘a mode of responding to distress that involves repetitively and passively focusing on symptoms of distress and on the possible causes and consequences of these symptoms’ (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). This tendency characterizes depression (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), and has been ascribed to deficient control processes that cannot rid memory of negative information (Joormann, 2005). As such, a growing literature has examined the relationship between depressive rumination and cognitive control during demanding cognitive tasks.

However, it is likely that the most prominent display of rumination is not when people are engaged in a task, but when they are at rest. Examining how individuals with MDD and healthy controls (HCs) compare during such rest periods is important because interleaved with the ongoing tasks of life are significant periods in which people do not engage in structured tasks, and instead are left to mind-wander or ruminate. In fact, recent research indicates that people mind-wander ∼10–15% of their wakeful hours1 (Sayette et al., 2009). Neurally, mind-wandering appears to engage regions of a ‘default network’ (Christoff et al., 2009, Mason et al., 2007)—a set of neural regions that activate in unison during off-task or ‘rest’ periods, which include the posterior-cingulate, portions of lateral parietal cortex as well as portions of the medial temporal lobe (MTL) and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC; Fox et al., 2005; Raichle, 2010; Shulman et al., 1997; Raichle et al., 2001).

Recent research examining the default network has revealed striking differences between MDDs and HCs. MDDs show increased default-network connectivity (compared with HCs) with the subgenual-cingulate cortex (SCC), a region located in the mPFC, which is positively correlated with the length of MDDs’ current depressive episodes (Greicius et al., 2007). Other researchers have shown abnormalities in the subgenual cingulate for MDDs (Sheline et al., 2009; see Drevets et al., 2008 for a review), and this brain region has also been linked to poor emotion regulation (Abler et al., 2008) and is activated more when healthy young adults are induced to ruminate (Kross et al., 2009). Moreover, stimulation of white matter tracts leading to the subgenual cingulate in MDDs has been associated with remission of depression concomitant with a decrease in hyperactivity of the subgenual-cingulate itself (Mayberg et al., 2005).

Even with all of this research, it is not clear what cognitive processes are reflected by these differences in default-network connectivity (Raichle, 2010). Although some researchers have speculated that this hyper-connectivity reflects rumination (Greicius et al., 2007), no research has directly tested this hypothesis. The first goal of the present research was to test whether default-network connectivity, particularly in the subgenual cingulate, is related to rumination.

Goal two was to examine how differences between MDDs and HCs in default-network connectivity changed when participants were on-task vs off-task. In everyday life, people’s attention wavers between tasks and unfocused thought (Sayette et al., 2009; Christoff et al., 2009). For example, the accountant at work may focus intensely on a balance sheet, but divert attention intermittently to thoughts unrelated to this task. In the present research, the relationship between default-state connectivity and rumination was examined using a situation that approximates such real-world conditions. The relationship between rumination and default-network connectivity was explored when participants performed a demanding short-term memory task interleaved with periods of rest. Alternating between rest and task epochs in this manner allowed us to explore whether default-network connectivity for MDDs and HCs varied between off-task and on-task periods. In addition, the relationships between self-report measures of rumination and default-network connectivity could then be compared for rest and task epochs separately.

In sum, this work was designed to examine whether measures of rumination predicted connectivity of the default state especially in the subgenual cingulate for depressed and healthy individuals, connectivity differences at rest persisted for on-task epochs and the relationship between rumination and default-network connectivity varied for on-task and off-task periods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and behavioral measures

Default-network connectivity in 15 MDDs (10 females, 5 males, mean age = 25.7 years) and 15 HCs (10 female, 5 male, mean age = 23 years) was explored during non-task fixation periods at the beginning and end of each run of a short-term memory experiment conducted in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) environment. The short-term memory task was a variant of a directed forgetting task (Nee et al., 2007), in which participants were initially instructed to remember four words, and after a delay were instructed to forget half of the words and remember the other half. After another delay interval, participants saw a single word and responded yes or no whether that word was one of the words in the to-be-remembered set. Sometimes, the single words were words from the to-be-forgotten set, and the ability of MDDs and HCs to forget positively valenced vs negatively valenced words was examined. A more detailed explanation of the task can be found in the Supplementary materials.

The diagnosis of MDD was determined with a Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV (SCID) by an advanced clinical psychology graduate student and was confirmed by a second independent rater. Behavioral rumination scores were measured with the Rumination Response Styles (RRS) inventory (Treynor et al., 2003), and depressive severity was also assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI; Beck et al., 1996). The RRS measured rumination subjectively with questions such as: ‘[How often do you] think “What am I doing to deserve this?” ’ or ‘[How often do you] think “Why do I always react this way?” ’ Participants responded with a 4-point scale ranging from 1-almost never, to 4-almost always. There were 22 items in total. The RRS can further be subdivided into three components: brooding, reflection and depression-related items (Treynor et al., 2003). MDDs and HCs differed significantly on brooding, the full RRS and the BDI, but no differences were found between the two groups on reflection scores (see Table S1 in the Supplementary Material). Six MDDs were medicated, and two MDDs had co-morbid anxiety.2

fMRI parameters

Images were acquired on a GE Signa 3-T scanner equipped with a standard quadrature head coil. Functional T2*-weighted images were acquired using a spiral sequence with 40 contiguous slices with 3.44 × 3.44 × 3-mm voxels [repetition time (TR) = 2000 ms; echo time (TE) = 30 ms; flip angle = 90°; field of view (FOV) = 22 mm2]. A T1-weighted gradient echo anatomical overlay was acquired using the same FOV and slices (TR = 250 ms, TE = 5.7 ms, flip angle = 90°). Additionally, a 124-slice high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical image was collected using spoiled-gradient-recalled acquisition (SPGR) in steady-state imaging (TR = 9 ms, TE = 1.8 ms, flip angle = 15°, FOV = 25–26 mm, slice thickness = 1.2 mm).

Each SPGR image was corrected for signal inhomogeneity and skull-stripped using FSL’s Brain Extraction Tool (Smith et al., 2004). These images were then normalized with SPM5 (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London), and normalization parameters were calculated from the standard MNI template. These parameters were then applied to the functional images maintaining their original 3.44 × 3.44 × 3-mm resolution, and were spatially smoothed with a Gaussian kernel of 8 × 8 × 8 mm3. Functional images were slice-time corrected using a 4-point sinc-interpolation (Oppenheim et al., 1999) and were corrected for head movement using MCFLIRT (Jenkinson et al., 2002). To reduce the impact of spike artifacts, AFNI’s de-spiking algorithm was implemented. There were 16 TRs of Fixation, eight at the beginning and end of each run, and 168 TRs of task (where participants performed a short-term memory task). There were 12 runs in the experiment.

Seed analysis

Default-network connectivity was revealed by selecting a seed voxel in the posterior-cingulate cortex (PCC), x = −7, y = −45, z = 24, and that voxel’s time-course was correlated within-subjects for all voxels in the brain. This seed was selected anatomically and is similar in location to regions that other authors have used to define the default network (Greicius et al., 2003; Fox et al. 2005; Monk et al., 2009; Raichle, 2010). The posterior cingulate has been argued to play a central role in the default mode network (Greicius et al., 2003), and has been found to reveal connectivity in the default network most effectively (Greicius et al., 2003) and is a reason why other authors have used the posterior cingulate as a seed to define the default network (Monk et al., 2009). In addition, it is an area of greatest deactivation during off-task behavior (Shulman et al., 1997).

Default-network connectivity was calculated separately for fixation and task blocks in which participants performed a short-term memory task. Task and fixation epochs were low-pass filtered, de-trended to remove within-run drift in the fMRI signal (de-trending was performed separately for the beginning and end fixations and acts as a high-pass filter) and processed to have a mean of ‘0’ and a standard deviation of ‘1’ separately for each TR, which was done to control for global activation changes that may have occurred over time. These runs were then concatenated together, which may have biased the correlations positively, but this potential bias did not interact with group. Thus, there were 192 TRs of fixation/rest (6.4 min) and 2016 TRs of task (Inter-Trial-Intervals were removed). While this may not be an ideal design due to the imbalance in number of TRs, the difference in the number of TRs for task and rest should not interact with group, which is of main interest in this study (i.e. comparing MDDs vs HCs during rest, during task and the difference between rest and task epochs). Correlation coefficients were converted to z-scores and entered into our two-sample t-tests in SPM 5. Results were thresholded at P < 0.001 (uncorrected) at the voxel-level and corrected by using a cluster-size threshold of 26 voxels to produce a P < 0.05 (corrected) threshold (Forman et al., 1995). An additional seed analysis was conducted with the mPFC as the seed region based on Fox et al., (2005). We performed region of interest (ROI) analyses for the connectivity networks obtained when using the mPFC as the seed. Two ROIs were of interest, the PCC (containing 455 voxels) and the MTL (containing 978 voxels) which were constructed anatomically based on the WFU PickAtlas. Results for these ROI analyses are reported at P < 0.05 (uncorrected) at the voxel-level and corrected by using a cluster threshold of eight contiguous voxels to produce a P < 0.05 corrected threshold (Forman et al., 1995).

RESULTS

Relation between rumination and neural connectivity

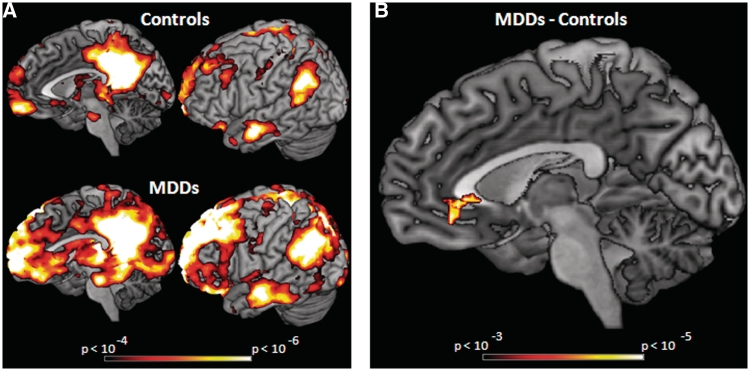

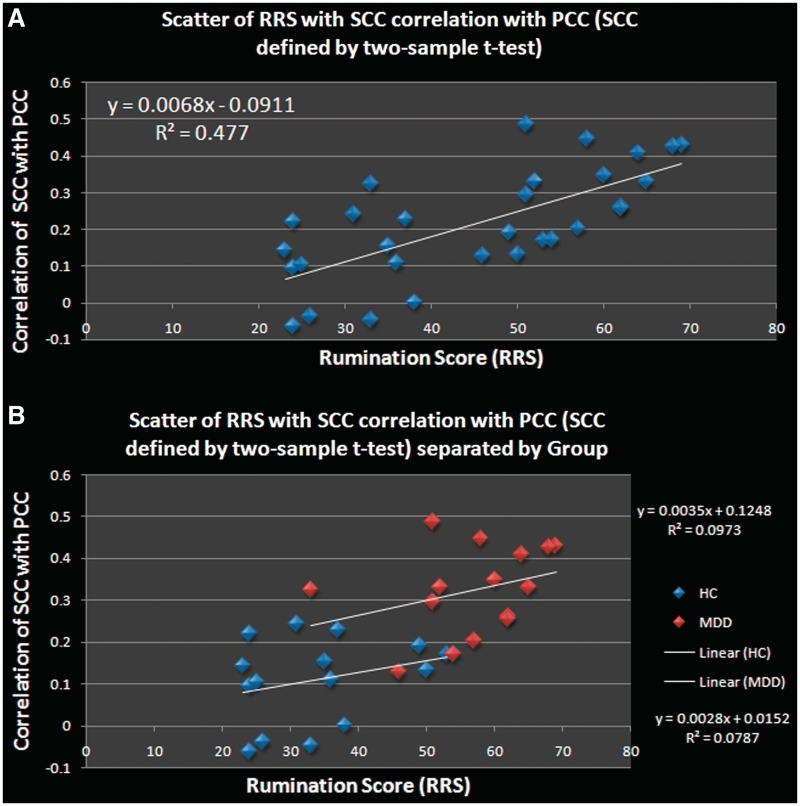

As depicted in Figure 1A, both groups showed high connectivity in the default network during fixation periods. A two-sample t-test comparing the default networks for MDDs vs HCs revealed that MDDs had stronger connectivity with the subgenual cingulate than HCs (Figure 1B) at standard statistical thresholds. At more liberal thresholds, MDDs show more connectivity in other areas as well, which can be seen visually in Figure 1A. To examine how rumination scores related to connectivity between the subgenual cingulate and the posterior cingulate, a functional ROI of the subgenual cingulate was created based on the two-sample t-test. Rumination scores (from the RRS) were then correlated with connectivity in this functionally defined region of interest (ROI) across all participants, which revealed a significant positive relationship (r = 0.68; P < 0.001; see Figure 2A). This relationship also held for both MDDs and HCs separately (Figure 2B), though these correlations were smaller due to the reduced range of the RRS measure (r = 0.30 for MDDs, r = 0.23 for HCs).

Fig. 1.

(A) Default-network connectivity for MDDs and HCs during fixation periods defined by connectivity with posterior-cingulate cortex, x = −7, y = −45, z = 24. Correlations >0.25 (P < 0.001) are displayed. (B) Results of a two-sample t-test comparing MDDs’ and HCs’ default-network connectivity during fixation periods. MDDs show more connectivity in the subgenual-cingulate than HCs (P < 0.05 corrected; peak at x = 0, y = 38, z = −9; 46 voxels).

Fig. 2.

(A) Correlations drawn from the resulting subgenual-cingulate ROI from the two-sample t-test comparing the groups at rest. SCC–PCC connectivity correlates positively with subjective rumination scores across groups (r = 0.68, 95% confidence interval r = 0.44–0.85). (B) Correlations drawn from the resulting subgenual-cingulate ROI from the two-sample t-test comparing the groups at rest. SCC–PCC connectivity correlates positively with subjective rumination scores for both MDDs and HCs. The linear relationship equation is shown in the upper right for MDDs, and lower right for HCs.

The functionally defined ROI that was used may be biased in that it was based on connectivity that was greater for MDDs, which may inflate the relationship between rumination scores and connectivity in that MDDs have reliably higher RRS scores. Therefore, a 10-mm sphere centered on subgenual-cingulate coordinates (x = 6, y = 36, z = −4) was constructed from an independent study (Zahn et al., 2009) and connectivity scores were extracted within this ROI. These connectivity scores were then correlated with RRS scores across all participants. Again, a reliable correlation (r = 0.53, P < 0.005; Table 1) was found suggesting that default-network connectivity with the subgenual cingulate is related to ruminative tendencies.

Table 1.

Bivariate correlations for all participants for the self-report measures of rumination and depression and the brain connectivity scores during rest and task periods extracted using the ROI from Zahn et al. (2009)

| Correlations for all participants |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connectivity rest | Brooding | Reflection | Depression | Full RRS | BDI | Connectivity Task | |

| Connectivity rest | |||||||

| Pearson R | 1 | 0.437* | 0.194 | 0.554** | 0.518** | 0.557** | 0.562** |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.016 | 0.304 | 0.002 | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| Brooding | |||||||

| Pearson R | 0.437* | 1 | 0.628** | 0.758** | 0.904** | 0.636** | 0.294 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.115 | |

| Reflection | |||||||

| Pearson R | 0.194 | 0.628** | 1 | 0.429* | 0.666** | 0.302 | 0.158 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.304 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.105 | 0.404 | |

| Depression | |||||||

| Pearson R | 0.554** | 0.758** | 0.429* | 1 | 0.943** | 0.864** | 0.362* |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.002 | 0.000 | 0.018 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.050 | |

| Full RRS | |||||||

| Pearson R | 0.518** | 0.904** | 0.666** | 0.943** | 1 | 0.794** | 0.347 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.060 | |

| BDI | |||||||

| Pearson R | 0.557** | 0.636** | 0.302 | 0.864** | 0.794** | 1 | 0.391* |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.105 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.033 | |

| Connectivity task | |||||||

| Pearson R | 0.562** | 0.294 | 0.158 | 0.362* | 0.347 | 0.391* | 1 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | 0.001 | 0.115 | 0.404 | 0.050 | 0.060 | 0.033 | |

Depression is the subscale of the RRS with the depression-related items.

*Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (two-tailed).

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

The correlation between RRS scores and connectivity was not driven by a main effect of group (i.e. the relationship between RRS and PCC–SCC correlations seems to be a continuous positive trend as it was for the functionally defined ROI from the two-sample t-test). In addition, the relationship between rumination and connectivity did not reliably differ between groups, Z(30) = 1.46, n.s. This may not be too surprising in that HCs also ruminate; they just do so to a lesser extent, so the relationship between connectivity and rumination should be the same for MDDs and HCs.

One problem with using the full RRS is that it contains items that assess depressive severity; therefore, our rumination results may be driven by depression severity and not rumination (Treynor et al., 2003). To control for this, connectivity scores from the ROI drawn from (Zahn et al., 2009) were correlated with the brooding component of the RRS, which does not contain items related to depression, yielding a significant positive correlation (r = 0.44, P < 0.05; Table 1). Unlike brooding, the reflection sub-component of the RRS did not correlate with connectivity scores (r = 0.19, n.s.; Table 1). Furthermore, when reflection scores were partialed out from the correlation between brooding and connectivity, the relationship was unchanged, (r = 0.41, P < 0.05). In contrast, when brooding scores were partialed out from the correlation between reflection and connectivity, this relationship became mildly, although not reliably, negative (r = −0.12, n.s.). These two partial correlations were also found to be reliably different from one another [Z(30) = 2.04, P < 0.05], which suggests that the correlation between PCC and SCC during rest periods is more related to negative forms of rumination than to other forms of self-reflection.

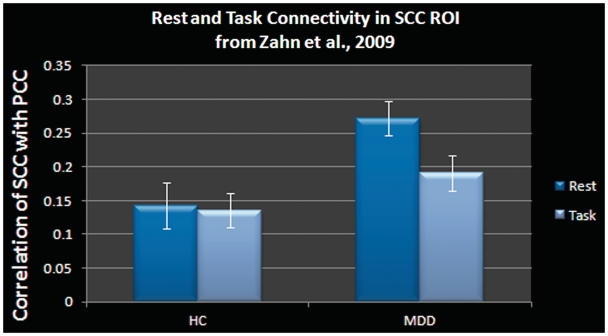

Connectivity differences for rest vs task epochs

These patterns of connectivity in the default network, however, were markedly different when participants were engaged in the memory task. A two-way ANOVA conducted on the subgenual-cingulate ROI from Zahn et al. (2009) was used to explore rest- vs task-related connectivity and revealed a significant task (rest vs task) by group (MDD vs HC) interaction [F(1,28) = 4.27, P < 0.05; Figure 3). Compared with rest, MDDs demonstrated significantly reduced connectivity while engaged in a task [t(14) = 2.87, P < 0.05]. In contrast, HCs showed no reliable changes in connectivity for task vs rest. Finally, during task epochs, MDDs and HCs did not differ in subgenual-cingulate connectivity, t(28) = 1.47, n.s., but did differ reliably for rest epochs as expected, t(28) = 3.15, P < 0.005. In addition, the correlation between rumination scores and connectivity between the PCC and SCC during task epochs was not reliable (r = 0.347, n.s.; Table 1) nor was task connectivity reliably correlated with brooding (r = 0.294, n.s.; Table 1), which suggests that being engaged in a task may disrupt the ability to ruminate by distracting participants and thereby interrupting the neural circuit that may mediate rumination.

Fig. 3.

The subgenual-cingulate ROI as defined from Zahn et al. (2009) demonstrates a task (rest, task) × group (MDD, HC) interaction highlighting a selective difference during periods of quiescence. No differences were found between groups for task epochs. Error bars represent 1 standard error of the group mean.

The correlation between resting-state connectivity and task-related connectivity in the subgenual cingulate was reliably correlated for HCs (r = 0.63, P < 0.05), but was not reliably correlated for MDDs (r = 0.38, n.s.). While this interaction was not reliable (potentially due to a lack of power), these results suggest that the ruminative connectivity pattern is more dissimilar for task and rest for MDDs (they may be ruminating at rest, but may not be able to during task engagement) than HCs (they may be maintaining a similar degree of rumination or mind-wandering throughout) whose connectivity patterns remain similar for both task and rest epochs.

Results could also differ based on medication as Anand et al. (2007) found some differences in connectivity between the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and limbic areas after MDDs had been on medication for 6 weeks. Six of our MDDs were medicated, thus posterior-cingulate to subgenual-cingulate connectivities were compared for our medicated and un-medicated groups for task and fixation as well as the interaction between the two for both the independent Zahn et al. (2009) ROI and the ROI that resulted from our two-sample t-test. No differences in connectivity between the medicated and non-medicated participants were found, which mitigates some concerns that our results may vary based on medication status.

mPFC connectivity

Another analysis was performed to interrogate whether our results may be specific to the PCC as the seed to define connectivity. The other common seed region that is used to define default-mode networks is the mPFC (Fox et al., 2005; Greicius et al., 2003). Utilizing mPFC coordinates from Fox et al. (2005) for the mPFC (x = −1, y = 47, z = −4), default-network connectivity during fixation was calculated with this mPFC seed utilizing the same procedure that was implemented with the posterior cingulate seed. When the two groups’ connectivity maps were compared at standard whole-brain thresholds, no differences were found. At liberal statistical thresholds (P < 0.05 for 20 contiguous voxels), MDDs did show more connectivity in other regions implicated in the default network such as the posterior cingulate. When an ROI analysis was performed within the PCC, two clusters were discovered in which MDDs showed more connectivity in this area at corrected thresholds (22 voxels centered at −10, −45, 24 and 11 voxels at 17, −58.3; see ‘Materials and methods’ section). This analysis shows that a similar pattern of results is found using the mPFC as the seed; however, it is not clear whether the same results should be expected with the mPFC as the seed vs the posterior cingulate, especially given the connectivity differences that Greicius et al. (2003) found when using the posterior cingulate as the seed vs the mPFC. According to Greicius et al. (2003), the PCC showed more connectivity to higher cortical areas, while the mPFC3 showed more connectivity to paralimbic and sub-cortical areas.

In fact, Bar (2009) proposes that constrained thinking fosters rumination and may be due to the mPFC exhibiting hyper-inhibition of the MTL. A second ROI analysis was performed within the MTL (consisting of the hippocampus, para-hippocampus and the amygdala). Again, MDDs showed more connectivity in this area at corrected thresholds (20 voxels in the left amygdala centered at −24, 7, −18; 29 voxels in the left para-hippocampal gyrus centered at −14, −41, 0; 17 voxels in the right amygdala centered at 14, −3, −21 and 18 voxels in the right hippocampus/parahippocampal gyrus centered at 31, −24, −18; see ‘Materials and methods’ section). This analysis is consistent with the Bar (2009) hypothesis that hyper-connectivity (that may be due to hyper-inhibition) between the mPFC and MTL leads to increased rumination.

Summary

These data show that the degree of correlation between the posterior cingulate and the subgenual cingulate is related to rumination and may distinguish MDDs from HCs, but only during off-task periods. Furthermore, the relationship between rumination and connectivity exists only during off-task periods. Lastly, brooding scores correlated with off-task connectivity, but reflection scores did not, which suggests that the thought contents during these off-task periods were negative and not entirely driven by depression severity. Therefore, it seems important to explore the relationship between rest and task connectivity when comparing MDDs and HCs.

DISCUSSION

Neural hyper-connectivity with the subgenual-cingulate seems to exist only during off-task periods for MDDs, and the connectivity of this area with the posterior cingulate is highly related to behavioral assays of depressive rumination. These results build on connectivity differences found in the subgenual cingulate by relating connectivity in that area to psychological processes such as rumination and brooding. These results also showed that hyper-connectivity at rest existed when rest periods were joined with task periods, a finding that may closely approximate real-world situations under which people are likely to engage in rumination, e.g. idle moments at work. Lastly, these results showed the selectivity of these neural differences (between MDDs and HCs) to off-task periods and that the relationship between ruminative psychological processes and connectivity is mitigated by engaging in a task.

The fact that hyper-connectivity in the subgenual cingulate for MDDs was found only during rest or off-task periods supports behavioral research suggesting that ‘distraction’(in our case, responsibility for completing a task) can be effective at temporarily relieving rumination and improving mood (Kross and Ayduk, 2008; for a review see Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). When MDDs engaged in the memory task, they displayed attenuated levels of connectivity in rumination-related regions. However, when left to their own thoughts, ruminative processes were engaged. This finding has important implications for future neuroimaging research and theory-building about the cognitive neuroscience of depression.

Additionally, when the mPFC was used as a seed, some similar results were found where MDDs showed hyper-connectivity in default-network areas (e.g. increased connectivity in the posterior cingulate). It is noteworthy that differences in the MTL were found, where MDDs showed greater connectivity. These hyper-connectivities in the MTL could reflect constrained thinking, which Bar outlines as a mechanism of rumination. More work will be needed to flesh out the relationship between rumination and constrained thought processing and their relation to neural connectivity, but it seems to be a promising enterprise that could lead to some important therapies.

It is tempting try to separate depression status from rumination, but this can be quite challenging considering that depression and rumination are highly overlapping constructs. This is evidenced by the high correlation found between rumination scores and BDI scores r =0.79. As such, an alternative explanation of our findings is that the connectivity between the posterior cingulate and the subgenual cingulate reflects depression severity more than rumination. While separating depression from rumination is not easily done, brooding scores (which do not contain depression-related items) correlated positively and reliably with connectivity, which suggests that this relationship is not driven by depression severity alone. Furthermore, reflection scores did not relate to connectivity scores, which indicate that this network does not signal positive thought patterns in our sample. In sum, depression severity does relate strongly to the connectivity between the subgenual cingulate and the posterior cingulate, but it may do so because of the tight coupling between rumination and depression as they are highly overlapping constructs.

The measure of rumination that was used in our study was a trait measure, namely how much people ruminate in their daily lives. However, it seems reasonable that this trait level measure would predict state rumination. First, as stated above, our correlations between brooding and connectivity scores during rest are greater than the correlations between reflection scores and connectivity during rest, thus providing some evidence that the thinking going on during these rest periods is probably not constructive. Second, partialing out reflection scores did not affect the correlation between brooding and connectivity during rest, indicating that other forms of thinking seem not to be explaining these data. It would have been difficult for us to ask participants what they were doing during these rest breaks post hoc, because it would have been difficult for participants to remember the thoughts they were having after the fact. Participants could have been prompted with rumination questions throughout the rest periods, but then the rest periods would not be as unguided. Since our rest periods were unguided (i.e. participants were not induced to ruminate) and interspersed with task epochs, some ecological validity may have been gained, since participants in the real world are not prompted to ruminate, but do so spontaneously.

As a more general point, our data suggest that studying on-task behavior may mitigate some differences between MDDs and HCs in that engaging in a task may disrupt rumination. Our data showed that the hyper-connectivities that were found at rest disappeared during the task, and the relationship between trait rumination and connectivity was also eliminated when performing a task. If rumination is a critical component of depression, then studying it may require moving to more unguided types of paradigms. This idea is consistent with Raichle’s (2010) suggestion of studying the resting state in both health and disease rather than focus solely on reflexive or ‘on-task’ performance.

Importantly, our results build on the results of Greicius et al. (2007) as MDDs demonstrate increased default-network connectivity with the subgenual cingulate that can be linked to rumination, but only during unguided rest periods. Based on these results, ruminative behavioral and psychological processes can be ascribed to these neural differences linking brain and behavior. In sum, subgenual-cingulate hyper-connectivity in MDDs was restricted to periods of quiescence and may provide a neural mechanism of rumination/brooding, a destructive form of mind-wandering.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the National Institute of Health (NIMH) 60655 to J.J., and a National Science Foundation (NSF) graduate fellowship to M.G.B. We thank Courtney Behnke, Melynda Casement and Hyang Sook Kim for help with data collection.

Footnotes

1Participants in this study were engaged in a reading task.

2We did not find any differences between medicated and non-medicated MDDs in any rumination scores, BDI or neural connectivity.

3Greicius et al. (2003) call the mPFC the ventral anterior cingulate cortex (vACC).

REFERENCES

- Abler B, Hofer C, Viviani R. Habitual emotion regulation strategies and baseline brain perfusion. Neuroreport. 2008;19(1):21–4. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f3adeb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar Moshe. A cognitive neuroscience hypothesis of mood and depression. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2009;13(11):456–63. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Christoff K, Gordon AM, Smallwood J, Smith R, Schooler JW. Experience sampling during fMRI reveals default network and executive system contributions to mind wandering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(21):8719–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Price JL, Furey ML. Brain structural and functional abnormalities in mood disorders: implications for neurocircuitry models of depression. Brain Structure & Function. 2008;213(1–2):93–118. doi: 10.1007/s00429-008-0189-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SD, Cohen JD, Fitzgerald M, Eddy WF, Mintun MA, Noll DC. Improved assessment of significant activation in functional magnetic-resonance-imaging (fMRI) – use of a cluster-size threshold. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 1995;33(5):636–47. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910330508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, van Essen DC, Raichle ME. The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102(27):9673–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504136102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Krasnow B, Reiss AL, Menon V. Functional connectivity in the resting brain: A network analysis of the default mode hypothesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(1):253–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0135058100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Flores BH, Menon V, et al. Resting-state functional connectivity in major depression: Abnormally increased contributions from subgenual cingulate cortex and thalamus. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62(5):429–37. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. NeuroImage. 2002;17(2):825–41. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joormann J. Inhibition, rumination, and mood regulation in depression. In: Engle RW, Sedek G, von Hecker U, McIntosh DN, editors. Cognitive Limitations in Aging and Psychopathology: Attention, Working Memory, and Executive Functions. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 275–312. [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Ayduk O. Facilitating adaptive emotional analysis: Distinguishing distanced-analysis of depressive experiences from immersed-analysis and distraction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2008;34(7):924–38. doi: 10.1177/0146167208315938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kross E, Davidson M, Weber J, Ochsner K. Coping with emotions past: the neural bases of regulating affect associated with negative autobiographical memories. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65(5):361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason MF, Norton MI, van Horn JD, Wegner DM, Grafton ST, Macrae CN. Wandering minds: The default network and stimulus-independent thought. Science. 2007;315(5810):393–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1131295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45(5):651–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monk CS, Peltier SJ, Wiggins JL, et al. Abnormalities of intrinsic functional connectivity in autism spectrum disorders. NeuroImage. 2009;47(2):764–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nee DE, Jonides J, Berman MG. Neural mechanisms of proactive interference-resolution. Neuroimage. 2007;38:740–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking Rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3(5):400–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheim AV, Schafer RW, Buck JR. Discrete-Time Signal Processing. 2nd edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001;98(2):676–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME. Two views of brain function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2010;14(4):180–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayette MA, Reichle ED, Schooler JW. Lost in the sauce: the effects of alcohol on mind wandering. Psychological Science. 2009;20(6):747–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02351.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI, Barch DM, Price JL, et al. The default mode network and self-referential processes in depression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106(6):1942–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812686106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman GL, Fiez JA, Corbetta M, et al. Common blood flow changes across visual tasks. 2. Decreases in cerebral cortex. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1997;9(5):648–63. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1997.9.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. NeuroImage. 2004;23:S208–19. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27(3):247–59. [Google Scholar]

- Zahn R, de Oliveira-Souza R, Bramati I, Garrido G, Moll J. Subgenual cingulate activity reflects individual differences in empathic concern. Neuroscience Letters. 2009;457(2):107–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.