ABSTRACT

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) studies report that marital/family support relates to glycemic control, adherence, and quality of life. Yet, there are few reports on couples-focused interventions. This study aims to describe the challenges faced and lessons learned in the implementation of a theoretically based, couples intervention. Three hundred fifty couples (one partner has T2DM in poor glycemic control) are randomized to a couples intervention, individual intervention, or enhanced usual care. All contacts are by telephone to increase reach. The medical (e.g., glycemic control), psychosocial (e.g., diabetes distress), and behavioral (e.g., regimen adherence) outcomes were measured. Challenges in recruitment, assessment, and intervention with couples are described, with suggestions about how to address them. Findings concerning the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the couples intervention, its effect on partners, and possible mechanisms of demonstrated changes, are anticipated in 2013. Interventionists need specific skills to work with couples to promote communal coping and increase the likelihood of an efficacious couples intervention.

KEYWORDS: Type 2 diabetes, Glycemic control, Marital interaction, Social support, Telephone intervention

It is estimated that 25.8 million Americans have diabetes with 1.5 million adults diagnosed in 2010. Complications (e.g., blindness, amputations) are life-threatening and disabling [1]. Studies have sought to identify factors that might impact health outcomes and the importance of family, and especially partner, support has been noted [2–5]. Further, research suggests that marital interaction, i.e., how the support is given/received, impacts both marital quality, and health functioning. Negative marital functioning can negatively affect health habits and depression [6] and directly influence endocrine, cardiovascular, immune, and neurosensory systems [7]. While Fisher and colleagues eloquently argued for a “family-focused” approach to disease management [8], most chronic illness interventions target the individual patient. The few studies that suggest models for intervention provide limited and disappointing data [9]. A recent cross-disease meta-analysis of 25 studies that specifically assessed the efficacy of couple-oriented interventions found significant, albeit small, improvements in depressive symptoms, pain, and marital functioning [10]. A meta-analysis of couples vs. individual weight loss interventions also found a significant, albeit small and short-lived, benefit of interventions that included partners [11]. However, a study of fibromyalgia patients [12] and several of behavioral smoking cessation interventions [13, 14] do not show benefits attributed to spousal support.

TYPE 2 DIABETES AND FAMILY/COUPLES INTERVENTIONS

Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) typically begins in adulthood and affects 90% of those with diabetes. T2DM outcomes are heavily determined by patient behavior, which may be affected by relationship factors. Correlational studies report that family support relates to better illness adaptation [15], treatment adherence [16, 17], and glycemic control [18, 19]. Also, marital adjustment, stress, and intimacy relate to glycemic control, quality of life, and adherence [16, 20, 21] and prospectively predict aspects of diabetes-related quality of life [20]. Yet, scant attention has been paid to family or couples interventions for adults with T2DM. Some have warned of potential negative effects of marital support, when the spouse functions like, what is commonly called, the “diabetes police” [22] and “Spouses’ investment of time and effort in attempting to influence patients’ treatment behavior may create marital friction without any improvement” (p. 373) [23]. A few studies have explored whether having the spouse be part of a diabetes intervention enhances its efficacy. With elderly diabetic patients in a diabetes education program, those whose spouses participated showed greater improvements in knowledge, metabolic control, and stress level than those who participated alone [24], and obese diabetic women, but not men, lost more weight if they participated with their obese spouses than if they participated alone [25].

CONCEPTUAL APPROACHES TO COUPLES INTERVENTIONS

These interventions assume that including partners leads to greater spousal support, which leads to better patient health outcomes. Lewis and colleagues conclude this model is overly simplistic and reliance on spouse participation may explain why couples interventions have not demonstrated better efficacy [26]. They argue that interventions should adopt a “dyad-level” model, i.e., address the behaviors, feelings, and thoughts of both partners. This approach recognizes the “interdependence” of partners, and that their interaction affects them both, not simply the behavior of one affecting the other. Interdependence theory, which provides our theoretical base [27, 28], states that partners must cope communally, agree that collaboration is helpful, communicate effectively, and talk about problems as they arise. Thus, if either feels that the patient should do it alone, then spousal involvement will be irrelevant. Or, if their efforts result in greater conflict, spousal involvement will be ineffective. This theory is supported by research showing that couples with conflictual communication patterns are at greater risk for cardiovascular problems and experience immune and endocrine system suppression during a conflict [7, 29].

OVERVIEW OF THE DIABETES SUPPORT PROJECT

The Diabetes Support Project (DSP) is designed to promote collaborative problem solving and communal coping in couples in which one partner has type 2 diabetes and is in poor glycemic control. It is a lifestyle behavior change intervention based on social learning theory principles [30] including behavioral contracting, self monitoring, realistic and incremental goal setting, knowledge development, and provision of social support for change [31]. While diabetic patients can change behavior using these strategies, longer-term maintenance of change is less successful [32] and couples interventions may improve gains maintained. By promoting couples collaboration, we hypothesize that we will demonstrate improved and better maintained diabetes outcomes.

The primary behavior change targets are: (1) blood glucose testing; (2) dietary change, including decreased fat and calorie intake, and carbohydrate consistency; and, (3) increased activity including moderate physical activity (e.g., walking) and decreased sedentary behaviors. The primary outcome is glycemic control.

STUDY DESIGN

The study is a two site, three-arm, randomized, controlled trial, comparing outcomes of three groups over time. Groups are described below. Couples (N = 350) are being recruited in Upstate NY and San Francisco/Sacramento areas of California.

PARTICIPANTS: INCLUSION/EXCLUSION CRITERIA

Patients who have T2DM and their partners are recruited through medical practices and advertising. Since hemoglobin A1c is the primary endpoint, we enroll individuals whose A1c is ≥7.5%, allowing for possible improvement. Participants identify as being in a committed relationship for at least 1 year. Other inclusion criteria include: over 21 years of age; diagnosed with T2DM for ≥1 year; no current medical or psychiatric problems that limit function in ways that will interfere with their ability to engage; able to speak, hear, and read English; and access to a telephone.

OUTCOMES

Multiple outcome measures assess the impact of the intervention on biological, behavioral, and quality of life measures. Patients and partners complete assessments at home or the institution. Medical assessments include A1c (patient only), height, weight, waist circumference, and resting/sitting blood pressure. Well-validated psychosocial questionnaires measure self-care and medication adherence, dietary and physical activity behaviors, quality of life, and relationship quality. We also measure potential mediators and moderators to refine the intervention in the future. Translation measures, per the RE-AIM model, measure reach, efficacy, implementation, and maintenance [33, 34]. Cost-effectiveness will be assessed per guidelines of a public health service panel [35].

STUDY CONDITIONS

Group 1: Couples telephone counseling (“Couples”)

This group is included to assess whether a couples intervention improves outcomes compared to an individual intervention (group #2) and to enhanced usual care (group #3). The partner is actively involved in all sessions and homework. The phone contact is fully interactive and homework tasks involve both partners in goal setting, contracting, and developing skills to promote collaborative care.

Group 2: Individual telephone counseling (“Individual”)

This group is included to assess whether individual education, goal setting, and support improve outcomes compared to a couples intervention (group #1) and enhanced usual care (group #3). The content and homework for each session parallels that of the Couples group, but the partner is not involved and relationship-specific content is not included.

Group 3: Enhanced usual care (EUC)

This group is included as a control group; outcomes reflect the effect of two diabetes self-management education contacts and subsequent usual care.

STUDY-DEVELOPED MATERIALS

Each patient (and partner, if in the Couples arm) has a study-designed workbook that includes the content to be discussed with the educator, material to read prior to calls, homework worksheets, and dietary/blood glucose/activity self-monitoring logs. Educators follow a specific “script” for each contact but are encouraged to tailor the content and speed of delivery of the information to the cultural preferences, and cognitive abilities, of the individuals.

INTERVENTION

Educators, trained and supervised for the study, are dietitians and either certified diabetes educators (CDEs) or with significant experience working with diabetic patients. The specific topics for each session are listed in Table 1. Calls 1–2 provide solid diabetes self-management education for all groups. The EUC group’s intervention ends here. For the two intervention groups, beginning with call #3, each session begins with a review of the participant’s progress in achieving goals set on the prior call. Homework includes dietary/activity self-monitoring (fat grams, carbohydrates, and steps/minutes) and goal setting, and participants establish specific, achievable behavior change goals. For example, they may “choose a low fat food at dinner 2 days per week”, or, “decrease the portion size of my (problem food) each day”, thus promoting incremental goal setting and opportunities for success. Homework also includes blood glucose (BG) testing “experiments”, i.e., participants keep track of BG levels before and 2–3 h after a meal or activity or a stressful event. They are taught to examine the data to learn from any patterns and experience how making a behavioral change (e.g., eating fewer carbs) affects their BG level.

Table 1.

DSP–call content

| Call number | Couples | Individual | Enhanced usual care |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Basic DSME 1a | Same | Same |

| 2 | Basic DSME 2b | Same | Same |

| 3 | Healthy eating 1: fat gram goal behavior change contract BG testing | Same | – |

| 4 | Emotions and DM: anxiety, depression, stress, relationships and DM, practice speaker–listener technique | Emotions and DM: anxiety, depression stress | – |

| 5 | Healthy eating 2: problem dietary situations carbohydrate consistency | Same | – |

| 6 | Healthy eating 3: behavior change strategies (what works, what does not) | Same | – |

| 7 | Couples communication styles (what works, what does not) | 6 step problem-solving process | – |

| 8 | DM and activity 1: benefits of walking, activity contract | Same | – |

| 9 | DM and activity 2: barriers to behavior change | Same | – |

| 10 | DM medications: medication adherence plan | Same | – |

| 11 | Review of goals/of barriers/of accomplishments | Same | – |

| 12 | The future ahead: new action plans to achieve goals and maintain gains | Same | – |

DSME diabetes self-management education

aBiology and T2DM, BG monitoring, HbAlc, meds, insulin, hypoglycemia, sick days, complications

bT2DM and diet, healthy eating, carbohydrate consistency, physical activity

In the Couples arm, homework actively involves the partner and how (s)he can support the patient to successfully change the targeted behavior. To promote communal coping, they also discuss how the patient can support the partner, who has identified his/her own challenges in coping with the patient’s diabetes. During session #4, they learn the “speaker–listener technique”, a way to improve listening and communication, and practice it in a discussion of a diabetes-related area of conflict. In session #5, they reflect on positive and negative ways they communicate. Thus, we not only educate about these issues, but via homework and interaction on the calls, encourage patients and partners to actively engage in reflection and communication exercises to promote shared problem solving. At times, conflict emerges especially if the partner is perceived as nagging. The educators address this directly and encourage discussion of differing expectations, goals, and/or behaviors, encourage them to use the speaker–listener technique to discuss the issue effectively, and at times, help them accept each other’s limitations.

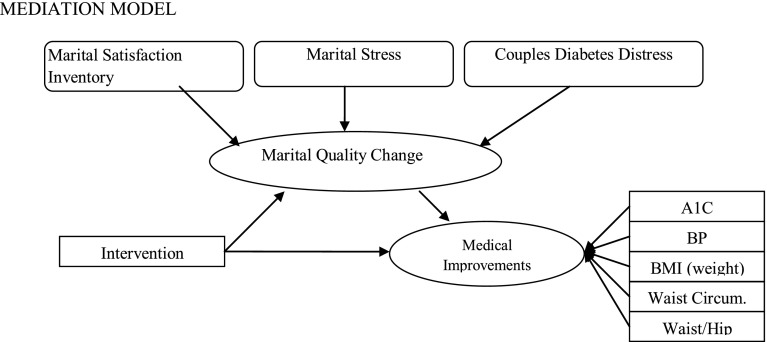

We hypothesize that the interventions, both individual and couples, will have direct effects on outcomes by helping patients work toward their goals more effectively. For the participants in the couples arm, we also hypothesize that this collaborative intervention will result in improved couples communication and marital quality and that the couples intervention will have indirect effects mediated by change in marital quality, i.e., less stress and distress and greater satisfaction. This model is depicted below.

CHALLENGES IN CLINICAL INTERVENTION RESEARCH WITH COUPLES

Recruitment

Definition of a “couple”

We have defined a couple as partners, together at least 1 year, who self-identify as being committed to each other. In modern times, a focus on only married couples would be too limiting. And, some couples are committed though may not live together. Thus, this definition includes partners who may not live together who attest to their mutual commitment and homosexual couples. This does not include other support figures in the patient’s life, e.g., siblings, who could be included in a clinical program for partners.

Both partners want to participate

Patients may resist randomization because they prefer the Couples arm. This may be because both partners have T2DM or, as a committed couple, they want to participate together. We cannot ethically prohibit the partner from reading the materials or listening to the calls if randomized to an individual intervention and include a questionnaire to assess actual partner involvement.

Patient does not want partner involved

Patients may resist randomization because they prefer the Individual arm. They may value independence (“I should know how to handle this on my own”), fear the partner’s criticism (“He’ll just get annoyed at me”), or do not want to add to their partner’s burdens (“She has too much to deal with already”).

One partner is more interested than the other

The patient may be motivated to join, while the partner is not, or vice versa. Differing levels of motivation are acceptable as long as there is sufficient motivation to participate. The educator may address this if it becomes apparent that it is a problem during the calls.

These issues are specific to a research protocol. We address them by explaining the rationale for research and randomization. We explain that randomization is a key to achieving reliable results. Also, we ensure that the consent process for each person is independent, and the research assistant prescreens them separately. For a clinical program, these issues are less salient, as one might advertise as a program for couples, but could decide to accept individual patients or partners alone.

Assessment

The key assessment issue is ensuring that the data provided are independent. Most of the questionnaires are completed by both patient and partner and some ask sensitive questions about relationship satisfaction. Partners may try to talk to each other to see how satisfied their partner is, e.g., “Sweetheart, what did you put down about how happy you are in our marriage?” They may also check in about more benign topics, e.g., “Honey, how often did we eat meat?” It is important therefore that the research assistant (RA) explains the rationale for independent assessments by stating that, for research purposes, it is important that we know what each of them believes independent of the other’s beliefs. Also, the RA should be present during the assessment or can even put them in different rooms to ensure that these discussions do not occur.

INTERVENTION LESSONS LEARNED AND EXAMPLES FROM OUR COUPLES ARM PARTICIPANTS (NAMES CHANGED FOR CONFIDENTIALITY)

Is a telephone couples intervention feasible and acceptable to patients and their partners?

Thus far, our evidence is that it is both feasible and acceptable. As of 1 June 2011, 689 couples were prescreened, 162 were eligible based on prescreening, 143 were consented, and 96 have been randomized. (A1c is measured at the assessment visit after consent was obtained. Therefore, 47 patients were either excluded for normal A1c or eligibility issues discovered after consent or are awaiting randomization.) Of the 67 who have completed the intervention phase, retention has been excellent, with only two subject withdrawals. Anecdotal reports of a high level of satisfaction support its acceptability.

The quiet partner

In many pairs, there is a dominant and a less active partner. The discussions and homework aim to engage both partners, and educators strive to hear from both partners using several techniques. They may use open-ended questions, e.g., “Bob, what are your thoughts about this issue?” They may direct questions specifically to the quiet partner, e.g., “Sally, you’ve been quiet, and we want to hear what you think too, so please share your thoughts about what Jim has said.” They may even make direct requests to the dominant partner to be less talkative, e.g., “Carl, you’ve made a lot of good points, but now it’s time to hear from Joan. Joan, what do you think?” This is an ongoing process of establishing the expectation that both partners will participate and be heard, of setting boundaries, and of making sure the individual speaks for him/herself. We note, however, that the educator also must respect differences in communication style and know when to push and when to back off allowing the quiet one to be as engaged as (s)he wishes, since we know that people learn from listening too.

Example: The “stars”—Bob and Nancy—early 60s, Caucasian. Nancy has T2DM. Nancy works hard to change behavior, i.e., she keeps good logs, has changed her eating habits, and started walking. Initially, Bob had little knowledge about T2DM, but was eager to learn and help Nancy. Although Bob was quiet during the sessions, and let Nancy take the lead, in terms of behavior change Bob was right at her side. He walked with her regularly; he reviewed her BG logs to better understand her numbers; he reminded her to take her medications. He slowly opened up and they report that they both felt good about sharing their fears about future complications, something they had never discussed. Both also liked the speaker–listener technique and reported using it to discuss other difficult issues.

Dealing with negative preexisting couple dynamics

Couples, often together for many years, have established ways of relating to one another. When partners communicate effectively and are receptive, the DSP intervention builds on these strengths. They both gain knowledge, hear each other’s concerns and feelings, and solve problems together. However, when they do not communicate well, conflict may emerge. One partner may use the intervention to criticize the other and resist exploring his/her own role in interactions. For example, Stan repeatedly points out that Marge does not follow her meal plan, e.g., “I don’t know why you signed up for this program, you’re not going to change and we both know it.” We do not believe that the contact causes this hostility and criticism, but it can be another forum for it to emerge, and if it does it is unlikely it will be beneficial and may even be detrimental by increasing partner distress. We address this in the script by including specific prompts to engage both partners positively. For example, we ask the partner to identify one behavior change (s)he noticed that his/her partner has made and to tell him/her (s)he is proud of him/her. We also train and supervise the educators in simple techniques to engage both partners described above. They are also trained to attend to and praise even the smallest positive interactions (e.g., “Bob, you really listened well to Marcia today. That’s what we’re working towards.”). Despite these efforts, sometimes significant dysfunction is evident. In this case, we help the educators to have realistic goals for a behavioral intervention and to know when and how to refer to couples therapy. Thus far, we have raised the possibility of couples therapy referral with two pairs, but they have not been receptive and the educator has been able to continue with the intervention.

Example: The “Strugglers”—James and Diane—early 60s, African–American. Diane has T2DM. Diane’s personality is “very strong”, James is very quiet. Diane blames James for not considering her feelings and needs enough, during the calls their conversations are one-sided and accusatory. The speaker–listener technique took 45 min! However, with gentle guidance through communication, Diane was able to recognize how supportive James is and admit that she had not thought about all he does for her. The educator says, “I learned how important it is to acknowledge her frustration, but to not engage in or encourage it.”

One partner wants to continue, one wants to drop out

As part of a research study, both partners must participate. If they are in the Couples arm and one partner wants to drop out, then the couple has to drop out. To our knowledge, this has not happened yet, but we anticipate it might and it is possible that this was the unstated issue in the two withdrawals. Should it occur, we would explore their reasons and try to address them. For example, if the time required is a barrier, we would be more flexible in scheduling sessions. Some patients do not want to do the required logging and we will work with that. Finally, we would ask them both to reflect on why they joined the program in the beginning to build on those initial motivations. Should this occur in a clinical program one might allow the motivated partner to continue if (s)he feels there is benefit.

Example: The unique outcome couple—Joe and Laura—mid 40s, Caucasian. Laura has T2DM, she always wanted Joe to be more involved and was thrilled, he agreed to participate. But, he did not “get it”; despite listening and participating, he seemed unable to understand her feelings or provide the type of support she needed. She planned to drop out. Joe insisted they continue, which meant a lot to Laura, and they did. At the end, Laura said “I was always frustrated that he didn’t care about my diabetes. Now I see that he does care, but he just can’t give me what I need. I’ve accepted it and let my resentment go. He’s a great guy and I love him. I’ll just have to get this type of support from others. I’m OK with that.”

CONCLUSION

Partners do have an effect on patients, sometimes good, sometimes bad. We are studying an innovative, theoretically based, telephone-administered behavior change intervention that promotes couples’ collaboration. The study includes the recommended elements, i.e., is theoretically grounded, includes a comparison to a patient-only intervention, evaluates change in relationship factors, and assesses partner outcomes too [10]. We have learned a lot about how to deal with the unique challenges of studying and working with couples. It is key to clarify what one means by a “couple” to define your target group. One must identify ways to engage both partners during recruitment if the intervention requires them both to be involved, despite potential differences in interest level. Assessments must be arranged to ensure that the data are independent. Finally, the interventionists need skills to engage both partners and to respect their communication styles while helping them grow in their interactions.

If our intervention is efficacious, other interventions may be tailored to include partners and to promote couples collaboration. Findings may clarify which couples benefit most from a couples intervention. Perhaps couples with a higher level of conflict are more responsive, as suggested by others [36]. Finally, since the intervention is telephone-delivered, time-limited, and delivered by CDEs, it should be able to be disseminated to clinical practitioners. Results are anticipated in 2013.

Acknowledgments

This study is being funded by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (grant no. 1R18DK080867-01A2 Clinicaltrials.gov no. NCT0107523).

Footnotes

Implications

Researchers: will learn about the unique challenges of recruiting, assessing, and intervening with couples.

Practitioners: will learn about the theoretical basis and key elements of an intervention that targets couples in which one partner has type 2 diabetes.

Policy: Policy makers will better understand the potential benefit of instituting policies that encourage couples collaboration in behavioral interventions.

References

- 1.American Diabetes Association website. Available at http://www.diabetes.org.diabetes-statistics.jsp. Accessibility verified. 20 Jan 2011

- 2.Dunkel-Schetter C. Social support and cancer: findings based on patient interviews and their implications. Journal of Social Issues. 1984;40:77–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01108.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herbert TB, Cohen S. Depression and immunity: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;113:472–486. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rissman R, Rissman BZ. Compliance: a review. Family System Medicine. 1987;5:61–67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primomo J, Yates BC, Woods NF. Social support for women during chronic illness: the relationship among sources and types of adjustment. Research in Nursing & Health. 1990;13:153–161. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770130304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell TA (2002) Physical disorder and effectiveness research in marriage and family therapy. In: Sprenkle D, ed. Effectiveness Research in Marriage and Family Therapy. 311–337.

- 7.Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Newton TL. Marriage and health: his and hers. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher L, Wiehs KL. Can addressing family relationships improve outcomes in chronic disease? Report of the National Working Group on family-based interventions in chronic disease. Journal of Family Practice. 2000;49:561–566. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmaling KB, Sher TB. The psychology of couples and illness: theory, research, and practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, Saghafi EM. Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010;40:325–342. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Black DR, Gleser LJ, Kooyers KJ. A meta-analytic evaluation of couples weight-loss programs. Health Psych. 1990;9:330–347. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.9.3.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Voogd JN, Knipping AA, de Blecourt ACE, van Rijswijk MH. Treatment of fibromyalgia syndrome with psychomotor therapy and marital counseling. Journal Musculoskeletal Pain. 1993;1:273–281. doi: 10.1300/J094v01n03_30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmer CA, Baucom DH, McBride CM. Couple approaches to smoking cessation. In: Schmaling T, Sher TG, editors. The psychology of couples and illness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. pp. 311–336. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McBride CM, Baucom DH, Peterson BL, et al. Prenatal and postpartum smoking abstinence: a partner-assisted approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2004;27:232–238. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trief PM, Grant W, Elbert K, Weinstock RS. Family environment, glycemic control and the psychosocial adaptation of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:241–245. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trief PM, Ploutz-Snyder R, Britton KD, Weinstock RS. The relationship between marital quality and adherence to the diabetes care regimen. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:148–154. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garay-Sevilla ME, Nara LE, Malacarra JM, et al. Adherence to treatment and social support in patients with NIDDM. Journal Diabetes & Complication. 1995;9:81–86. doi: 10.1016/1056-8727(94)00021-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukunishi I, Horikawak N, Yamzaki T, Shirasaka K, Kanno K, Akimoto M. Perception and utilization of social support in diabetic control. Diabetes & Clinical Practice. 1998;41:207–211. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(98)00083-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cardenas L, Vallbona C, Baker S, Yusim S. Adult onset diabetes mellitus: glycemic control and family function. American Journal Science Medicine. 1987;293:28–33. doi: 10.1097/00000441-198701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trief PM, Himes CI, Orendorff R, Weinstock RS. The marital relationship and psychosocial adaptation and glycemic control of individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1384–1389. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.8.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pieper BA, Kushion W, Gaida S. The relationship between a couple's marital adjustment and beliefs about diabetes mellitus. The Diabetes Educator. 1990;16:108–112. doi: 10.1177/014572179001600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Schwartz C. Assessment of diabetes-specific distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:754–760. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peyrot M, McMurry JF, Hedges R. Marital adjustment to adult diabetes: Interpersonal congruence and spouse satisfaction. Journal Marriage & the Family. 1988;50:363–376. doi: 10.2307/352003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilden JL, Hendryx M, Casia C, Singh SP. The effectiveness of diabetes education programs for older patients and their spouses. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1989;37:1023–1030. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb06915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wing RR, Marcus MD, Epstein LH, Jawad A. A family based approach to the treatment of obese type II diabetic patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:156–162. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.59.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis MA, McBride CM, Pollak KI, Puleo E, Butterfield RM, Emmons KM. Understanding health behavior change among couples: an interdependence and communal coping approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;62:1369–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley HH, Thibaut TW. Interpersonal relations: a theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rusbult CE, Van Lange PA. Interdependence, interaction, and relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:351–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robles TF, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The physiology of marriage: pathways to health. Physiology and Behavior. 2003;79:409–416. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(03)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning and personality development. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shumaker SA, Schron EB, Ockene JK, McBee W, editors. The handbook of health behavior change. New York: Springer; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Delamater AM, Jacobson AM, Anderson B, et al. Psychosocial therapies in diabetes: report of the Psychosocial Therapies Working Group. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1286–1292. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.7.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glasgow RE, Klesges LM, Dzewaltowski DA, Bull SS, Estabrooks P. The future of health behavior change research: what is needed to improve translation of research into health promotion practice? Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:3–12. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2701_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glasgow RE, Nelson CC, Strycker MA, King DK. Using RE-AIM metrics to evaluate diabetes self management support interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;30:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siegel JE, Weinstein MC, Russell LB, Gold MR. Recommendations for reporting cost-effectiveness analyses. Panel on cost-effectiveness in health and medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276:1339–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.276.16.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Manne S, Ostroff JS, Winkel G. Social-cognitive processes as moderators of a couple-focused group intervention for women with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2007;26:735–744. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]