Abstract

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract characterized by recurring flares followed by periods of inactive disease and remission. The etiology is unknown, although the common opinion is that the disease arises from a disordered immune response to the gut contents in genetically predisposed individuals. Infliximab (IFX), a chimeric immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody to tumor necrosis factor, has dramatically changed the approach to managing patients with CD and improving their treatment, by achieving treatment goals, such as mucosal healing, and decreasing the need for hospitalizations and surgeries. This review provides an update on existing evidence for the use of IFX in CD, taking into account the safety profile in clinical practice and special situations such as pregnancy. Antitumor necrosis factor therapy has been evaluated as an induction and maintenance therapy in CD in several randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses, showing efficacy in both clinical settings. Early use of biologics may improve patient outcomes in active CD. However, a widespread use of a “top-down” approach in all CD patients cannot be recommended. Clinical factors at diagnosis may predict poor outcome in CD, and should be taken into account when determining the initial therapeutic approach.

Keywords: Crohn’s disease, infliximab, adult

Introduction

Current models of Crohn’s disease (CD) indicate an initial disturbance of the epithelial interface between the gut mucosa and intestinal microbiota, suggesting that mucosal damage by luminal bacteria is an early, initiating factor in the etiopathogenesis of the disease. However, a number of features of CD argue against a primary mucosal process, including phenotypic studies of patients with CD that point to a macrophage defect and genetic studies that predict impaired innate immunity to intracellular bacteria. A contemporary working model suggests an immunologic defect plus the presence of certain bacteria, stimulating a variety of experimental models that aim to dissect the mucosal immune response to intestinal microbiota as a function of defined chemical, genetic, or immunologic perturbations. The intestinal flora as a whole and specific bacteria and their products have been found to trigger cytokine expression in various cell types. Consistently, multiple bacterial strains were found to induce tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-8 in macrophage and epithelial cell systems, respectively, in particular in CD. In inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), the evidence indicates that dysregulation of mucosal immunity in the gut causes an overproduction of inflammatory cytokines and trafficking of effector leukocytes into the bowel, leading to uncontrolled intestinal inflammation. Under normal conditions, the intestinal mucosa is in a state of “controlled” inflammation regulated by a delicate balance of proinflammatory (TNF, interferon-gamma [IFN-γ], IL-1, IL-6, IL-12), and anti-inflammatory (IL-4, IL-10, IL-11) cytokines.

Interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha

IL-1 and TNF-α share a multitude of proinflammatory properties and appear to be critical to the amplification of mucosal inflammation in IBD. Both cytokines are primarily secreted by monocytes and macrophages upon activation, and induce intestinal macrophages, neutrophils, fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells to produce prostaglandins, proteases, and other soluble mediators of inflammation and injury, as well as other inflammatory and chemotactic cytokines. An enhanced expression of IL-1 and TNF-α was found in inflammatory bowel disease, and the important role of TNF-α was also confirmed in the genesis of these diseases. TNF-α has several biologic activities that may be directly related to the pathogenesis of IBD, and there is increasing evidence suggesting a central role for TNF-α in CD.1 The effects of TNF-α in the intestine are disruption of the epithelial barrier, induction of apoptosis of the villous epithelial cells and secretion of chemokines from the intestinal epithelial cells. TNF-α activates endothelium by upregulating E-selectin and other adhesion molecules, such as intercellular adhesion molecule-1, as well as by inducing the expression of cytokines and chemokines. Several studies have shown that TNF-α production is increased in the intestinal mucosa2 and in the serum of patients with CD.3

Prior to the introduction of biologic agents in the late 1990s, patients with moderate-to-severe CD or fistulous CD had few nonsurgical options. Systemic corticosteroid therapy is effective for acute CD, and budesonide may be an alternative for those with terminal ileal CD for whom systemic steroid adverse effects are a concern. These drugs are not recommended for maintenance therapy in IBD. Immunosuppressants are generally not recommended for inducing remission in active CD. The exception to this is that intramuscular methotrexate may be of benefit as an adjunct to steroids in inducing remission in CD. The thiopurine immunosuppressive agents, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and methotrexate, are effective steroid-sparing drugs that maintain remission in patients with CD. Infliximab (IFX) is a chimeric mouse/human monoclonal IgG1 antibody comprised of 75% human and 25% murine sequences, which has a high specificity for and affinity to TNF-α, and neutralizes the biologic activity of TNF-α by inhibiting binding to its receptors. It has proven to be a powerful new tool for the treatment of moderately to severely active CD that is refractory to conventional therapy.

In parallel with IFX, two more humanized anti-TNF-α agents were developed. Adalimumab is a fully human recombinant IgG1 monoclonal antibody against TNF-α, and is approved for use in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and luminal CD. Unlike IFX, adalimumab is administered by subcutaneous injection and can be easily self-administered every 2 weeks. Certolizumab pegol (CDP-870) is a pegylated humanized fragment antigen binding (Fab) that binds TNF-α; it is administered subcutaneously and has been approved in the US for treatment of CD.4,5 The choice of first anti-TNF-α agent will depend greatly on the personal preference of the treating physician and the patient’s perspectives on convenience issues. The objective of this paper was to review the role of IFX in patients with CD, in terms of clinical efficacy and safety in various indications. Table 1 lists current indications and contraindications for IFX therapy in CD.

Table 1.

Indications and contraindications for infliximab therapy in CD

| Indications | Contraindications |

|---|---|

| Refractory luminal CD | Active abscess or infections |

| Steroid-dependent CD | Suspected active tuberculosis |

| Refractory fistulizing CD | Intestinal obstruction |

| Systemic manifestations of IBD | Multiple sclerosis or optical neuritis |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Previous lymphoma or neoplastic disease |

| Chronic uveitis | Heart failure |

Abbreviations: CD, Crohn’s disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Induction of remission in patients with active CD

Multiple studies have evaluated the efficacy of IFX in patients with active luminal CD. Several centers have also published their clinical experience with IFX, which provides further insight into the effectiveness of IFX outside of the clinical trials setting. Approval was based upon the results of two randomized controlled trials (a single-dose trial and a multiple-dose trial) involving a total of 653 patients with moderately to severely active CD (Crohn’s Disease Activity Index [CDAI] ≥220 and ≤400) who had responded inadequately to conventional therapy.6,7 The results are confirmed by a Cochrane review8 and by two meta-analyses9,10 of placebo-controlled trials that evaluated the efficacy of TNF-α antagonists for luminal disease demonstrating that IFX is more efficacious than placebo in inducing remission in moderate to severely active luminal CD.

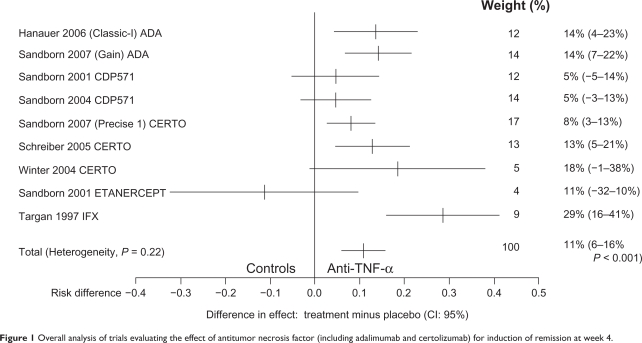

The efficacy of IFX for induction of clinical remission is summarized in Figure 1 which shows an overall analysis of trials for induction of remission at week 4, with a number needed to treat of three, based on only one small study performed by Targan et al.6 This single-dose trial included 108 patients with moderate-to-severe CD who were randomly assigned to a single 2-hour intravenous infusion of either placebo or IFX by comparing doses of 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg with placebo. At 4 weeks of follow-up, 22 of 27 patients (81%) who received IFX at a dose of 5 mg/kg, 14 of 28 (50%) who received 10 mg/kg, and 18 of 28 (64%) who received 20 mg/kg had a clinical response compared with four of 24 (17%) who received placebo. Remission occurred significantly more often in those randomized to IFX (33% of the treated group overall vs 4% of the placebo group). The clinical response persisted in many patients over the 12 weeks of follow-up (41% vs 12%). Statistical analyses demonstrated no effect of concomitant medication or disease location on response rates or remission rates. There was no statistically significant difference between the three doses of IFX used in the trial, although the 5 mg/kg body weight dose consistently yielded the highest response and remission rates.

Figure 1.

Overall analysis of trials evaluating the effect of antitumor necrosis factor (including adalimumab and certolizumab) for induction of remission at week 4.

Experience with IFX has accumulated rapidly since the initial controlled trial demonstrating the role of IFX in inducing clinical remission in active luminal CD disease. A report from the University of Chicago that included 129 treated patients with intestinal disease found the median time to initial response was 8 days, with a 65% response rate at 3 weeks. The median time to remission was 9 days, with a 31% response rate.11 Relapse occurred in 78% of patients at a mean of 8.5 weeks. Steroid tapering was seen in more than 90% of patients, with 54% able to stop steroids. Treatment of patients with IFX markedly decreases endoscopic and histologic disease activity in Crohn’s colitis.12,13 An Italian multicenter study involving 12 centers and 573 patients by Orlando et al14 represents a large and valuable Italian experience addressing the question of predictive factors determining the response to IFX in CD. The primary endpoints of the study were clinical response and clinical remission in patients with luminal refractory disease treated with a dose of 5 mg/kg. Patients were followed for at least 6 months after infusion, showing that 322 patients (84.1%) had a clinical response 12 weeks after the first infusion and 228 (59.5%) reached clinical remission. This study identifies the use of a single infusion and previous resectional surgery as negative predictive factors of IFX response in refractory luminal disease. In summary, evidence from the controlled trials and meta-analyses supports the use of biological therapy in patients with CD who have failed treatment with first-line and second-line drugs, or who are corticosteroid-dependent.

Induction of remission in fistulizing disease

IFX was approved for use in fistulizing CD based upon the results of two randomized controlled trials.15,16 One study included 94 patients who were unresponsive to at least 3 months of conventional therapy who were randomly assigned to receive three doses of IFX (5 or 10 mg/kg) or placebo at weeks 0, 2, and 6. After a follow-up of 26 weeks, significantly more patients receiving IFX had a reduction in the number of draining fistulas without requiring an increase in other medications (68% and 56% in the 5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg arm, respectively, vs 26% for placebo). Closure of all fistulas was observed in 55% and 38% of patients receiving the 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg dose, respectively, compared with 13% of those receiving placebo. This study did not address issues such as relapse rate after initial success or the potential benefit of combining IFX with immunomodulators or antibiotics. Whether the combination of IFX and oral antibiotics improves efficacy is unclear and more evidence is needed. A randomized controlled trial involving 24 patients with severe perianal disease concluded that the combination of IFX plus ciprofloxacin (500 mg orally twice daily) was more effective than IFX alone.17 A prospective study18 assessed the efficacy and safety of treatment of perianal CD by means of a combination of surgical management and a standardized protocol for the intravenous infusion of IFX showing that the combination of seton drainage and infusion of IFX completely healed the perineum in 47% of patients with complex fistulizing perianal CD. A small uncontrolled case series confirms these initial results.19 Two open-label Italian studies20,21 evaluated IFX as a local injection adjacent to the perianal fistula tract in patients with CD and contraindications to systemic infusion, showing encouraging results, but further controlled clinical investigations are warranted.

Maintenance of response and remission

Patients with moderate-to-severe luminal CD who have responded to an induction regimen with anti-TNF-α therapy should be considered for scheduled retreatment with or without concomitant immunomodulators. This strategy is more effective than episodic therapy for maintaining response. The largest and most comprehensive study of maintenance therapy (ACCENT I) was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, international trial studying retreatment and maintenance of remission in patients with CD treated with IFX.22

The study included patients who had moderate-to-severe non-fistulizing CD (CDAI 220 to 400) for at least 3 months refractory to conventional treatment, and compared single-dose with three-dose induction. Of the 573 patients entered into the study, 335 (58%) had a clinical response to IFX at 2 weeks. Of the 473 responders, 325 (69%) responded by week 2 and another 127 (27%) by week 10. After 10 weeks, there was a statistically significant improvement in response and remission rates in the two groups that received scheduled maintenance therapy. Sixty-five percent of the patients had a clinical response (including 40% who achieved remission), while 31% demonstrated mucosal healing. In contrast, only 28% of patients who received a single initial dose entered remission. The initial clinical response was maintained significantly more often in the two groups that received scheduled maintenance therapy (43% and 53% vs 17% in the 5 mg/kg, 10 mg/kg vs single-dose groups, respectively). After 54 weeks, the median duration of response was only 19 weeks for patients in the single-dose group, compared with 38 weeks for the IFX 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks group, and greater than 54 weeks for patients in the IFX 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks group. In patients who initially had a clinical remission, maintenance of remission occurred in only 14% of patients in the single-dose group compared with 28% of patients maintained on IFX 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks and 38% of patients on IFX 10 mg/kg every 8 weeks. Patients receiving scheduled therapy had significantly fewer CD-related hospitalizations (23% vs 38%) and surgeries (3% vs 7%). After 54 weeks, clinical remission and successful tapering of the patient off steroids was observed significantly more often in the two scheduled maintenance groups (28% and 32% vs 9% in the 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg groups vs the single infusion group, respectively). Of particular importance, significantly more patients receiving scheduled IFX had discontinued glucocorticoids and were also in clinical remission with a CDAI < 150 (31% and 36.8% vs 10.7% for the 5 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg doses vs placebo, respectively). Patients assigned to the scheduled maintenance groups had significant improvement in quality-of-life as measured by a validated instrument (IBDQ).23 Furthermore, patients who could be maintained in remission had increased employment and fewer hospitalizations and surgeries.24 A recent meta-analysis25 confirms that IFX prevents relapse of quiescent luminal CD once remission has been achieved, maintains clinical remission (relative risk [RR]: 2.50; 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 1.64–3.80), maintains clinical response (RR: 1.66; 95% CI: 1.00–2.76), and has corticosteroid-sparing effects (RR: 3.13; 95% CI: 1.25–7.81). Schnitzler et al26 assessed the long-term efficacy of IFX in a large cohort of patients who had CD, with a median follow-up of almost 5 years. The analysis demonstrated excellent efficacy of IFX in maintaining improvement not only during 1 year as in the published trials but also during a median follow-up of 4.6 years, showing sustained clinical benefit defined as a lasting control of disease activity during follow-up, with persistent improvement of symptoms in 63.4% of patients.

Patients with fistulizing disease

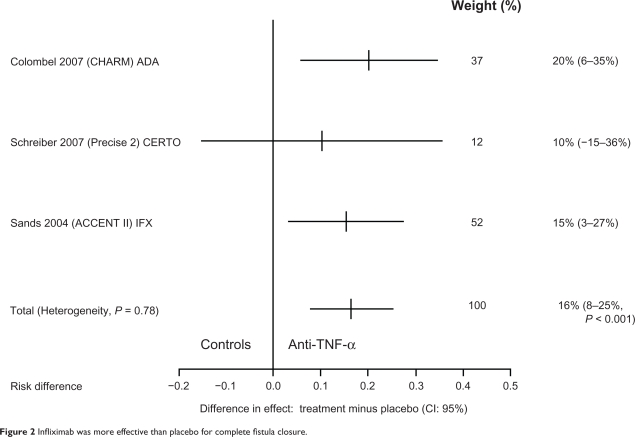

Patients with fistulizing CD who have responded to an induction regimen with anti-TNF-α therapy should receive scheduled retreatment with IFX. The pivotal maintenance trial for IFX in fistulizing CD was ACCENT II which included 306 adults with one or more draining abdominal or perianal fistulas of at least 3 months’ duration. Systematic treatment with IFX 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks was superior to placebo in both improvement and closure of draining fistulas over 54 weeks. The median time to loss of response was >40 weeks vs 14 weeks on scheduled treatment with 5 mg/kg every 8 weeks following three-dose induction therapy (see Figure 2 which shows that IFX was more effective than placebo for complete fistula closure). Lichtenstein et al27 examined the effect of IFX maintenance treatment on hospitalizations, surgeries, and procedures in patients with fistulizing CD enrolled in the ACCENT II study and showed that among patients randomized as responders there was a >50% reduction in the mean number of CD-related hospitalizations compared with placebo maintenance treatment, and the length of stay of patients was also significantly reduced (from 2.5 to 0.5 days). IFX maintenance treatment was also associated with a >70% reduction in the mean number of CD-related inpatient surgeries and procedures, as well as major surgeries. Patients had an approximately 50% reduction in all surgeries and procedures, as compared with placebo maintenance treatment. An Italian multicenter group28 reported an initial response to induction with IFX in 76% of 188 patients with perianal CD and a 44% clinical remission rate. The ACCENT I and ACCENT II studies have shown that scheduled maintenance therapy with IFX is superior to episodic therapy to maintain response and remission, both in luminal and in fistulizing CD.

Figure 2.

Infliximab was more effective than placebo for complete fistula closure.

Use of immunosuppressive agents in combination with IFX

There are conflicting opinions regarding the use of immunosuppressive agents in combination with IFX due to several safety reports. The GETAID group evaluated the usefulness of short-term IFX combined with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine in 113 steroid-dependent CD patients stratified as follows: the failure stratum consisted of patients receiving azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine at a stable dose for more than 6 months, and the naïve stratum consisted of patients not treated previously with azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine. Patients were randomized to IFX 5 mg/kg or placebo at weeks 0, 2, and 6. All patients were treated with azathioprine/6-mercaptopurine maintained at a stable dose throughout the 52 weeks of the study. The study demonstrated the benefits of initiating IFX treatment earlier by showing that IFX plus azathioprine combination therapy is more effective than azathioprine monotherapy in azathioprine-naïve patients29 for achievement of remission (CDAI < 150) in the IFX group than in the placebo group (57% vs 29%, respectively) without steroids at week 24, and to reduce exposure to steroids. It is less clear whether it is beneficial to use the IFX-azathioprine combination in patients who previously failed therapy with azathioprine. The occurrence of hepatosplenic T cell lymphomas in patients on IFX in combination with azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine, along with an increased incidence of opportunistic infections in patients on more than one immunosuppressive agent, led to the recommendation that IFX be given as monotherapy without concomitant immunosuppressive agents, mainly in a particular setting of patients. Data from the SONIC30 study demonstrated that patients with moderate to severe CD treated with azathioprine 2.5 mg/kg/day in combination with IFX 5 mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6 and then every 8 weeks, or IFX alone, are more likely to have a glucocorticoid-free clinical remission than those on azathioprine alone (57% and 44% vs 31%, respectively). The benefit was relevant in those with endoscopic or biochemical evidence of active inflammation. In contrast, there seems to be no synergism between methotrexate and IFX for the induction and maintenance of steroid-free remission in luminal CD.31 The Combination of Maintenance Methotrexate-IFX Trial was a randomized placebo-controlled study comparing methotrexate in combination with IFX against IFX alone in patients who received prednisone induction therapy for active CD. The primary endpoint was time-to-treatment failure (success was CDAI < 150 through week 50 and no steroids). There were no differences in steroid-free remission between the two groups (76% and 77% at week 14; 56% and 57% at week 50). Because of the risks of combination therapy noted earlier, consideration can be given to using combination therapy and then having an “exit strategy”. This concept was addressed in a study of patients whose disease had been controlled for at least 6 months on maintenance IFX combined with immunosuppressive agents who were randomly assigned to continue or stop the immunosuppressive agents while they continued IFX maintenance therapy for up to 2 years;32 the primary endpoint was the proportion of patients who required a decrease in the IFX dosing interval or stopped IFX therapy. The results of the study were that discontinuation of immunosuppressive agents after 6 months did not adversely affect either response or remission after IFX at the end of 2 years. In contrast with these results, a recent paper postulated the usefulness of cotreatment with immunomodulators and scheduled IFX treatment.33 In patients with CD who have responded to 1 year of anti-TNF-α therapy, the benefits of continuing therapy should be weighed against the risks of discontinuation. Unfortunately, there are still insufficient data to make recommendations on when to stop anti-TNF-α therapy. Preliminary evidence suggests that for patients in clinical remission for more than 1 year, with a normal C-reactive protein and mucosal healing, an appreciable proportion will remain in remission during the year after stopping treatment. In a cohort study from Leuven, 20% of patients who had responded to IFX were able to stop therapy over a variable amount of time.34 A study of IFX discontinuation in CD patients in stable remission on combined therapy with immunosuppressor therapy recruited 115 patients in steroid-free remission on IFX + azathioprine for more than 1 year and discontinued IFX. The relapse rate was 57% in the first year. Predictors of relapse included smoking, previous steroid use, elevated fecal calprotectin, and elevated C-reactive protein. Randomized controlled data are required to confirm these observations. A significant portion of patients are termed “primary nonresponders” and do not show improvements in their symptoms at the end of induction. Indeed, a significant rate of patients who initially respond to the treatment subsequently lose this response (termed “secondary failures”) and experience flares of disease necessitating dose escalation, switch to another anti-TNF-α drug, or surgical intervention. It has been shown that loss of response to anti-TNF-α at 12 months of therapy occurs in 23%–46% of patients when judged by dose intensification, or 5%–13% when gauged by drug discontinuation rates.35 Several mechanisms are proposed to explain loss of response to anti-TNF-α but the most investigated is immunogenicity due to antidrug antibodies. In a study focusing on these issues, anti-IFX antibodies were detected in 61% of 125 patients with refractory CD treated repeatedly during a 10-month period.36 The presence of antibody titers at a level of 8.0 μg/mL was significantly associated with a shorter duration of response (35 days vs 71 days) and a higher risk of infusion reactions (relative risk 2.40). The concentration of IFX was significantly lower at 4 weeks among those patients who had an infusion reaction compared with those who never had an infusion reaction. The concomitant use of immunosuppressive therapy was predictive of low titers of anti-IFX antibodies and higher concentrations of IFX 4 weeks after infusion. It was shown that scheduled treatment is better than episodic because it elicits less immunogenicity and that loss of response can be prevented by concomitant immunomodulators.37

Extraintestinal manifestations

Maintenance therapy with IFX may be helpful in resolving extraintestinal manifestations of CD, particularly arthritis and arthralgias.38 In the case of failure of traditional therapy, the efficacy of anti-TNF-α agents is largely established,39 with an obvious advantage for patients with active intestinal disease. A large, prospective, open-label trial demonstrated improvement of peripheral arthritis in patients with IBD who had previously been refractory to corticosteroids, 6-mercaptopurine, azathioprine, or methotrexate. In this study, patients were treated with IFX 5 mg/kg at baseline (luminal CD) and at weeks 2 and 6. At the end of 12 weeks, 36/59 (61%) patients had significant improvement of their arthritis, defined by improvement of one point in the arthritis component of CDAI score, and complete resolution of arthritis in 27/59 (46%) patients.40 A small uncontrolled series supported the use of IFX in axial arthritis associated with IBD.41 Cutaneous manifestations, such as erythema nodosum and pyoderma gangrenosum, are classically associated with inflammatory bowel disease, occurring in 3%–20% and 0.5%–20% of patients, respectively. In many cases, pyoderma gangrenosum refractory to standard medications (oral, intravenous, and intralesional corticosteroids, azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, antibiotics, dapsone, cyclosporine, FK506, and mycophenolate) has been successfully treated with anti-TNF-α agents. In one small multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (30 patients with pyoderma gangrenosum, 19 of whom also had IBD) IFX 5 mg/kg as a single infusion has been compared with placebo.42 A response was observed in 46% of patients receiving IFX compared with 6% of those receiving placebo (P = 0.0025). Ocular manifestations developed in 2%–6% of patients with IBD, with the most common being episcleritis and uveitis. Many case reports and pilot studies have demonstrated that IFX can suppress uveitis and scleritis associated with various autoimmune disorders, including IBD.

Predictors of response in luminal and fistulizing CD

Smoking and concomitant use of immunosuppressive drugs appear to have an important influence on the initial response and durability of response in patients with inflammatory disease. A study from the Cleveland Clinic included 100 patients with inflammatory or fistulous CD who were followed for at least 3 months after treatment.43 In those with inflammatory disease, an initial response was significantly more likely in nonsmokers (73% vs 22%) and in those taking concurrent immunosuppressive medications (74% vs 39%). A prolonged response (more than 2 months) was also more likely in nonsmokers (59% vs 6%) and in those taking concomitant immunosuppressive medications (65% vs 18%). For those with fistulous disease, overall response rates were no different between smokers and nonsmokers, but nonsmokers had a longer duration of response. Patients with isolated colonic disease,44 those of young age,45 those with endoscopic evidence of ileocolonic ulcers at baseline, and those with an elevated C-reactive protein had a better response, whereas those with stricturing disease46 or previous abdominal disease47 were less likely to respond.48

Safety

Although short- and long-term anti-TNF-α therapy is generally well tolerated, clinicians must be vigilant for the occurrence of infrequent but serious adverse events (see Table 2). A long-term report of safety data over a 14-year period reported a 13% rate of severe adverse events vs 19% in placebo group. A recent review compared the rate of different adverse events among biologics and placebo, and concluded that serious adverse events such as infections, lymphoma, and congestive heart failure did not have a significantly different incidence between biologics and control treatment. IFX was associated with a significantly higher risk of withdrawals due to adverse events compared with controls (odds ratio: 2.04, 95% CI: 1.43–2.91; number needed to harm = 12, 95% CI: 8–28).49 Safety data from the SONIC trial demonstrated that the rate of adverse events was similar among the IFX monotherapy, IFX plus azathioprine, and azathioprine monotherapy groups. Infusion reactions occurred less frequently among patients receiving combination therapy but the risk of opportunistic infections increases when TNF-α therapy is combined with additional immunosuppressive treatment.

Table 2.

Adverse events associated with infliximab use

| Infections (opportunistic and mycobacterial) |

| Cytokine release reactions |

| Autoimmunity (formation of antinuclear and DNA antibodies) |

| Malignancies |

| Heart failure |

| Demyelination |

| Liver function abnormalities |

| Dermatologic complications (psoriasis and other skin lesions) |

A report from the Mayo Clinic described the clinical experience in 500 patients who received a median of three infusions and were followed up for a median of 17 months.50 Although the authors concluded that therapy was generally well tolerated, they warned that clinicians using IFX should be vigilant for the occurrence of infrequent but serious adverse events, particularly in elderly patients. A more recent paper reports that patients older than 65 years treated with TNF inhibitors for IBD have a high rate of severe infections and mortality compared with younger patients or patients of the same age who did not receive these drugs.51

The most important concerns with prolonged use of biologics are related to cancer risk. A recent multicenter, matched-pair study assessed whether IFX use in CD for a median of 6 years is associated with an increased frequency of neoplasia in the long term. The authors concluded that the frequency of neoplasia was comparable in an adult population of CD patients treated or not with IFX.52 Toxicity can be significantly reduced by routine tuberculosis screening, and by avoiding anti-TNF agents in patients with heart failure, chronic infections, or previous neoplastic disease. Prospective, observational studies with longer follow-up, such as the TREAT registry,53 will continue to provide more useful information on this issue, and clinicians need to remain aware of the potential for serious adverse events during longer-term exposure beyond the confines of clinical trials. Patients with intestinal strictures due to CD may be less likely to respond to treatment and are also at risk for developing acute bowel obstruction. These issues were examined in a review of data from the TREAT study and the ACCENT studies.54 In the TREAT study, intestinal stenosis, strictures, and obstruction occurred significantly more often in patients receiving IFX compared with those receiving other treatments. However, on multivariate analysis, the only independent predictors of stenosis were the severity and duration of CD, the presence of ileal disease and new glucocorticoid use. In ACCENT I, no increase in stenosis was described in those receiving IFX maintenance therapy compared with those who received episodic therapy. Thus, these data do not support a causal role for IFX in the development of stenosis.

Early treatment

In recent years the hypothesis that early treatment with biologics may influence the natural history of CD has developed.55 The early approach can be interpreted in terms of early onset in patients with newly diagnosed CD, or to prevent postoperative relapse. In patients with newly diagnosed CD naïve for corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or biologics, the early use of combined immunosuppression (IFX plus azathioprine) is more effective than conventional management for induction of remission and reduction of corticosteroid use. These data suggest that reversing the treatment paradigm from a “step-up” to a “top-down” approach may positively alter the natural course of this illness. The evidence indicates that early use of biologic therapy, in combination with immunomodulators, resulted in remission occurring more rapidly than the conventional “step-up” treatment, with a longer time period to relapse, decreased need for treatment with corticosteroids, faster reduction in clinical symptoms, rapid decline in biochemical inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein), and improved endoscopic mucosal healing. In 2006, a retrospective study of 1123 patients identified clinical factors associated with a subsequent 5-year disabling course of CD56 suggesting that patients presenting at a young age with stricturing disease, needing initial treatment with steroids, and with perianal disease at diagnosis have a poorer prognosis. Such patients may benefit from early introduction of biologic or immunomodulator therapy. However, the correct approach is debated.

The impact of IFX on recurrence in the postoperative setting had not yet been reported.

Sorrentino et al57 studied 12 consecutive patients treated immediately after surgery who maintained clinical and endoscopic remission with maintenance IFX 5 mg/kg for 24 months after surgery, and whose IFX treatment was discontinued. At 4 months after discontinuation of IFX, 10 of the 12 patients (83%) developed endoscopic recurrence (Rutgeerts score i2, i3, or i4). The 10 patients were treated again with IFX 3 mg/kg every 8 weeks, and mucosal integrity was then restored and maintained for 1 year. From their findings, long-term maintenance therapy with IFX is required to maintain mucosal integrity in patients after surgery for CD.

Subsequently, Regueiro et al58 conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 24 patients with CD who had undergone ileocolonic resection and were allocated to receive intravenous IFX (5 mg/kg, n = 11) or placebo (n = 13) administered within 4 weeks of surgery and continued for 1 year. The endoscopic recurrence rate at 1 year was significantly lower in the IFX group (9.1%) compared with the placebo group (84.6%). The histologic recurrence rate at 1 year was significantly lower in the IFX group (27.3%) compared with the placebo group (84.6%). From these results, 1 year of IFX treatment after surgery was effective for preventing endoscopic and histologic recurrences of CD, but some clarifications should be made. The population included was at high risk for recurrence and this could explain the high rate of recurrence in the placebo group. It is notable that almost half of the study patients continued to receive immunomodulator therapy and this could raise a safety issue. Although it had a small sample size, this study provides the strongest evidence for the efficacy of postoperative IFX therapy, but a larger prospective randomized trial to evaluate the sustained efficacy of IFX as a single agent to prevent postoperative recurrence is desirable.

IFX cannot be recommended for all patients after surgery because of potential adverse events and high medical costs. IFX should be used for patients at high risk of postoperative recurrence. Recently, Yamamoto et al59 conducted a prospective pilot study to investigate the efficacy of IFX in preventing early endoscopic recurrence after ileocolonic resection, and showed that IFX therapy reduced clinical and endoscopic disease activity in patients with early endoscopic recurrence after surgery. Clearly, the effectiveness of such a strategy should be demonstrated with longer follow-up.

Pregnancy

IFX is currently rated as a class B medication for pregnancy. Although large molecules like IFX do not cross the placenta during the early stages of pregnancy, it has recently been shown that there are detectable levels present in fetal serum at birth,60 indicating that there may be diffusion across the placenta in the third trimester. These findings suggest that pregnant patients should avoid therapeutic antibody treatments after 30 weeks’ gestation, and if necessary, the expectant mother can be bridged with steroids to control disease activity until delivery. One report identified 131 pregnancies in which the women were exposed directly to IFX for treatment of CD or rheumatoid arthritis.61 Outcome data were available for 96 of these women. Rates of live births, miscarriages, and therapeutic terminations was similar to those expected for the general population of pregnant women or pregnant women with CD not exposed to IFX. In the TREAT registry, of the 5807 patients enrolled, 66 pregnancies were reported, 36 of them with prior IFX exposure. Fetal malformations did not occur in any of the pregnancies. Rates of miscarriage and neonatal complications were not significantly different between IFX-treated and IFX-naïve patients (11.1% vs 7.1% and 8.3% vs 7.1%, respectively). Despite these encouraging observations, prospective data will be needed to determine more definitively the risk of IFX therapy prior to conception and during pregnancy. There are no available data on the use of IFX during breast feeding, except some case reports suggesting placental rather than breast milk transfer of IFX.

Conclusion

IFX has become a powerful tool for the treatment of moderately to severely active CD that is refractory to conventional therapy, improving quality of life in a significant proportion of patients suffering with CD. Clinical trials have demonstrated significant utility of IFX for induction of remission in moderately active, steroid-refractory CD and maintenance of remission in these patients for up to 54 weeks after initial infusion. For fistulizing CD, the efficacy of IFX for inducing fistula closure is best documented. Patients receiving scheduled therapy had significantly fewer CD-related hospitalizations. Long-term follow-up has underscored the benefit of therapy in properly selected patients in order to avoid widespread use.

According to current European62 and Italian63 guidelines for treatment of CD and the American Gastroenterological Association guidelines64 on the use of biologics in IBD, biological therapy is indicated in steroid-refractory, steroid-dependent, and/or immunomodulator-refractory IBD, in patients intolerant to these conventional therapies, and in conjunction with surgical drainage when CD is complicated by a complex fistula. Unfortunately, there are still insufficient data to make recommendations on when to stop anti-TNF therapy, and the benefits of continuing therapy should be weighed against the risks of discontinuation. A number of adverse events have been described following treatment with IFX, and thus providers and patients should be familiar with the risks as well as appropriate measures to prevent and monitor for complications.

Keypoints

IFX therapy in CD is effective at inducing and maintaining remission in steroid-refractory, steroid-dependent, and/or immunomodulator-refractory IBD, and in patients intolerant to conventional therapies.

IFX allows more profound control of bowel inflammation resulting in mucosal healing than conventional therapies, which could translate into improvement in long-term outcome of the disease course.

Preliminary data show that IFX therapy decreases the need for hospitalizations and surgery in patients with luminal or fistulizing CD.

Clinical data demonstrate an excellent efficacy and safety profile in selected patients.

IFX works best in patients with evidence of active inflammation as demonstrated by an elevated C-reactive protein and patients with nonstricturing disease.

From the current evidence, an association with immunomodulators should be evaluated carefully.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest with regard to this work.

References

- 1.Plevy SE, Landers CJ, Prehn J, et al. A role for TNF-alpha and mucosal T helper-1 cytokines in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease. J Immunol. 1997;159:6276–6282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reimund JM, Wittersheim C, Dumont S, et al. Increased production of tumour necrosis factor-alpha interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-6 by morphologically normal intestinal biopsies from patients with Crohn‘s disease. Gut. 1996;39:684–689. doi: 10.1136/gut.39.5.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bosani M, Ardizzone S, Porro GB. Biologic targeting in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases. Biologics. 2009;3:77–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 4.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn’s disease: The CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, et al. Adalimumab induction therapy for Crohn disease previously treated with infliximab: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:829–838. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn’s disease. Crohn’s Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: The ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akobeng AK, Zachos M. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody for induction of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;1:CD003574. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003574.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, et al. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn’s disease: Meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:644–653. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ford A, Sandborn WJ, Khan KJ, et al. Efficacy of biological therapies in inflammatory bowel disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:644–659. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen RD, Tsang JF, Hanauer SB. Infliximab in Crohn’s disease: First anniversary clinical experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3469–3477. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Dullemen HM, van Deventer SJ, Hommes DW, et al. Treatment of Crohn’s disease with anti-tumor necrosis factor chimeric monoclonal antibody (cA2) Gastroenterology. 1995;109:129–135. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D’haens G, Van Deventer S, Van Hogezand R, et al. Endoscopic and histological healing with infliximab anti-tumor necrosis factor antibodies in Crohn’s disease: A European multicenter trial. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:1029–1034. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orlando A, Mocciaro F, Colombo E, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: Predictors of response in an Italian multicentric open study. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.West RL, van der Woude CJ, Hansen BE, et al. Clinical and endosonographic effect of ciprofloxacin on the treatment of perianal fistulae in Crohn’s disease with infliximab: A double-blind placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1329–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talbot C, Sagar PM, Johnston MJ, Finan PJ, Burke D. Infliximab in the surgical management of complex fistulating anal Crohn’s disease. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:164–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2004.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guidi L, Ratto C, Semeraro S, et al. Combined therapy with infliximab and seton drainage for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease with anal endosonographic monitoring: A single-centre experience. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:111–117. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0411-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poggioli G, Laureti S, Pierangeli F, et al. Local injection of infliximab for the treatment of perianal Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:768–774. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asteria CR, Ficari F, Bagnoli S, et al. Treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease by local injection of antibody to TNF-alpha accounts for a favourable clinical response in selected cases: A pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:1064–1072. doi: 10.1080/00365520600609941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn’s disease: The ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feagan BG, Yan S, Bala M, et al. The effects of infliximab maintenance therapy on health-related quality of life. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2232–2238. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, Hanauer S. Remission in patients with Crohn’s disease is associated with improvement in employment and quality of life and a decrease in hospitalizations and surgeries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:91–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behm BW, Bickston SJ. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha antibody for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;1:CD006893. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in 614 patients with Crohn’s disease: Results from a single-centre cohort. Gut. 2009;58:492–500. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.155812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, Blank M, Sands BE. Infliximab maintenance treatment reduces hospitalizations, surgeries, and procedures in fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:862–869. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orlando A, Colombo E, Kohn A, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: Predictors of response in an Italian multicentric open study. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lémann M, Mary JY, Duclos B, et al. Infliximab plus azathioprine for steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease patients: A randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1054–1061. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. SONIC Study Group Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Feagan B, McDonald JWD, Panaccione R, et al. A randomized trial of methotrexate in combination with infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:294–295. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Assche G, Magdelaine-Beuzelin C, D’Haens G, et al. Withdrawal of immunosuppression in Crohn’s disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance: A randomized trial. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1861–1868. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sokol H, Seksik P, Carrat F, et al. Usefulness of co-treatment with immunomodulators in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with scheduled infliximab maintenance therapy. Gut. 2010;59:1363–1368. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.212712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in 614 patients with Crohn’s disease: Results from a single-centre cohort. Gut. 2009;58:492–500. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.155812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ben-Horin S, Chowers Y. Review article: Loss of response to anti-TNF treatments in Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:987–995. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baert F, Noman M, Vermeire S, et al. Influence of immunogenicity on the long-term efficacy of infliximab in Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:601–608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vermeire S, Noman M, Van Assche G, Baert F, D’Haens G, Rutgeerts P. Effectiveness of concomitant immunosuppressive therapy in suppressing the formation of antibodies to infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2007;56:1226–1231. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.099978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hanauer SB, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer L, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease: Response to infliximab (Remicade) in the ACCENT I trial through 30 weeks. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:A26. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Braun J, Brandt J, Listing J, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with infliximab: A randomised controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1187–1193. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Herfarth H, Obermeier F, Andus T, et al. Improvement of arthritis and arthralgia after treatment with infliximab (Remicade) in a German prospective, open-label, multicenter trial in refractory Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2688–2690. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.06064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rispo A, Scarpa R, Di Girolamo E, et al. Infliximab in the treatment of extra-intestinal manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Scand J Rheumatol. 2005;34:387–391. doi: 10.1080/03009740510026698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooklyn TN, Dunnill MG, Shetty A, et al. Infliximab for the treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum: A randomised, double blind, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2006;55:505–509. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.074815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parsi MA, Achkar JP, Richardson S, et al. Predictors of response to infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:707–713. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vermeire S, Louis E, Carbonez A, et al. Demographic and clinical parameters influencing the short-term outcome of anti-tumor necrosis factor (infliximab) treatment in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2357–2363. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnott ID, McNeill G, Satsangi J. An analysis of factors influencing short-term and sustained response to infliximab treatment for Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1451–1457. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seksik P, Loftus EV, Beaugerie L, et al. Validation of predictors of 5-year disabling CD in a population-based cohort from Olmsted County, Minnesota 1983–1996. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:A17. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinberg AM, Rattan S, Lewis JD, et al. Strictures and response to infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:S255. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. Role of genetics in prediction of disease course and response to therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2609–2615. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i21.2609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Singh JA, Wells GA, Christensen R, et al. Adverse effects of biologics: A network meta-analysis and Cochrane overview. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;2:CD008794. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008794.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Colombel JF, Loftus EV, Jr, Tremaine WJ, et al. The safety profile of infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease: The Mayo Clinic experience in 500 patients. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:19–31. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cottone M, Kohn A, Daperno M, et al. Advanced age is an independent risk factor for severe infections and mortality in patients given anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Biancone L, Petruzziello C, Orlando A, et al. Cancer in Crohn’s disease patients treated with infliximab: A long-term multicenter matched pair study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:758–766. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, et al. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn’s disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lichtenstein GR, Olson A, Travers S, et al. Factors associated with the development of intestinal strictures or obstructions in patients with Crohn’s disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1030–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D’Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn’s disease: An open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660–667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, et al. Predictors of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:650–656. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sorrentino D, Paviotti A, Terrosu G, et al. Low-dose maintenance therapy with infliximab prevents postsurgical recurrence of Crohn’s disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:591–599. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Regueiro M, Schraut W, Baidoo L, et al. Infliximab prevents Crohn’s disease recurrence after ileal resection. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:441–450. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamamoto T, Umegae S, Matsumoto K. Impact of infliximab therapy after early endoscopic recurrence following ileocolonic resection of Crohn’s disease: A prospective pilot study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1460–1466. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vasiliauskas EA, Church JA, Silverman N, Barry M, Targan SR, Dubinsky MC. Case report: Evidence for transplacental transfer of maternally administered infliximab to the newborn. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1255–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Katz JA, Antoni C, Keenan GF, Smith DE, Jacobs SJ, Lichtenstein GR. Outcome of pregnancy in women receiving infliximab for the treatment of Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2385–2392. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.D’Haens GR, Panaccione R, Higgins P, et al. The London Position Statement of the World Congress of Gastroenterology on Biological Therapy for IBD With the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization: When to start, when to stop, which drug to choose, and how to predict response? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:199–212. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, et al. Clinical practice guidelines: The use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy ininflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lichtenstein GR, Abreu MT, Cohen R, et al. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on corticosteroids, immunomodulators, and infliximab in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:940–987. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]