Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to assess the extent of knowledge of primary health care (PHC) patients about colorectal cancer (CRC), their attitudes toward population-based screening for this disease and gender differences in these respects.

Methods

A questionnaire-based survey of PHC patients in the Balearic Islands and some districts of the metropolitan area of Barcelona was conducted. Individuals between 50 and 69 years of age with no history of CRC were interviewed at their PHC centers.

Results

We analyzed the results of 625 questionnaires, 58% of which were completed by women. Most patients believed that cancer diagnosis before symptom onset improved the chance of survival. More women than men knew the main symptoms of CRC. A total of 88.8% of patients reported that they would perform the fecal occult blood test (FOBT) for CRC screening if so requested by PHC doctors or nurses. If the FOBT was positive and a colonoscopy was offered, 84.9% of participants indicated that they would undergo the procedure, and no significant difference by gender was apparent. Fear of having cancer was the main reason for performance of an FOBT, and also for not performing the FOBT, especially in women. Fear of pain was the main reason for not wishing to undergo colonoscopy. Factors associated with reluctance to perform the FOBT were: (i) the idea that that many forms of cancer can be prevented by exercise and, (ii) a reluctance to undergo colonoscopy if an FOBT was positive. Factors associated with reluctance to undergo colonoscopy were: (i) residence in Barcelona, (ii) ignorance of the fact that early diagnosis of CRC is associated with better prognosis, (iii) no previous history of colonoscopy, and (iv) no intention to perform the FOBT for CRC screening.

Conclusion

We identified gaps in knowledge about CRC and prevention thereof in PHC patients from the Balearic Islands and the Barcelona region of Spain. If fears about CRC screening, and CRC per se, are addressed, and if it is emphasized that CRC is preventable, participation in CRC screening programs may improve.

Keywords: Colorectal neoplasm, population-based screening, fecal occult blood test, primary healthcare, attitude, knowledge

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is a significant health problem in developed countries, both because of its high incidence and because it is accompanied by high mortality. An epidemiological analysis of all cancers in Spain indicated that CRC had the highest incidence and the second highest mortality rate for both genders. Every year, approximately 25,600 new cases of CRC are diagnosed [1] and, in 2008, 10,604 patients died from CRC (4,630 men and 5,974 women) (INEbase). An epidemiological study indicated that the incidence of CRC in Spain is increasing, but mortality therefore is declining [2].

CRC is one of the few types of cancer for which both primary and secondary prevention are possible. With respect to secondary prevention, the evidence strongly indicates that population-based screening using the fecal occult blood test (FOBT), and colonoscopy if FOBT results are positive, reduces both the incidence of and mortality from CRC [3]. Participation of a large proportion (more than 50%) of the population in testing is crucial for the success of screening programs [4]. Thus, it is necessary to ensure widespread compliance before implementation of a CRC screening program.

The Theory of Reasoned Action indicates that intention to participate in a CRC screening program overlaps with the Theory of Planned Behavior, the most proximal determinant of participation [5,6]. Intention to participate is associated with a positive attitude toward screening, and knowledge of both CRC and cancer screening in general is an important prerequisite if a positive attitude toward CRC screening is to develop [7]. The knowledge of the general population about CRC is currently poor [7,8], and gender differences in attitudes toward CRC screening are apparent [9,10].

In Spain, a National Cancer Strategy promotes the development of population screening programs for CRC, and several regions are currently implementing such programs. No program has yet been implemented in the Balearic Islands (located in the western Mediterranean Sea) whereas, in Catalonia, after completion of a pilot study, a program will soon be extended to the entire region.

The present work is part of a more comprehensive project that aims to assess the knowledge and attitudes of primary health care (PHC) professionals [11] and patients toward CRC screening. In particular, the present study is exploratory in nature, and precedes implementation of a population-based CRC screening program in the Balearic Islands. The present work was performed during implementation of a CRC screening program in Barcelona. We assessed the extent of knowledge of PHC patients about CRC, their attitudes toward population-based screening for this disease and gender differences in these respects. A secondary objective was to identify factors that might support the use of FOBT and colonoscopy in the context of CRC population-based screening

Methods

Design

This was a cross-sectional descriptive study based on a survey of adult patients visiting PHCs in the Balearic Islands (which had 1,014,405 inhabitants in 2007) and in the southern metropolitan area of Barcelona (with 1,275,679 inhabitants in 2007).

Study population

Patients 50 to 69 years of age who visited PHCs for any reason from January to June 2009 were included. Patients with a diagnosis of CRC or who had a terminal illness were excluded. In both areas, sample size was calculated assuming that 50% of PHC patients would participate in a population-based screening program. Using a confidence level of 95% and a precision of 5%, the estimated sample size was 384 patients for each area. Systematic sampling of participant nurse quotas was used. The first patient (and his/her companion) scheduled to be visited on Tuesdays and Thursdays in participant nurses' agendas were invited to participate in the study if they met inclusion criteria.

Data collection

We developed a questionnaire based on literature review [7,8,12-15]. In December 2008, we performed a pilot study by administering the questionnaire to 20 patients in one healthcare center. As a result, the wording and/or format of some questions were/was modified. Between January and June 2009, 30 nurses in the Balearic Islands and 29 nurses in Barcelona administered the final questionnaire during patient visits. All participants signed informed consent agreements.

This study was approved by the Primary Health Care Research Committee, the Balearic Islands Ethics Committee for Clinical Research, and the Ethics Committee of the Primary Care Research Institut IDIAP Jordi Gol.

Variables

The questionnaire explored the following variables: sociodemographics; lifestyle (tobacco consumption, daily fruit and vegetable consumption, extent of physical exercise); history of chronic health problems, intestinal polyps, and cancer; use of PHC services; knowledge about cancer and CRC; past experience with cancer screening (mammography, cytology, FOBT, colonoscopy, prostate-specific antigen [PSA] measurement, and computed tomography [CT]); attitudes toward FOBT as a CRC screening tool and toward colonoscopy if an FOBT is positive; reasons for performing or not performing an FOBT; and rationales for undergoing or not undergoing colonoscopy. With respect to variables exploring knowledge and attitudes, the possible responses were: "I agree", "I disagree", or "I do not know". Questions on performance or non-performance of FOBT or colonoscopy were posed in multiple-choice format.

Statistical analysis

Answers to questionnaires were recorded in a in a Microsoft Access database using Teleform 4.0 for Windows. We determined the frequencies of all qualitative variables and assessed the normality of quantitative variables, the means and medians of which were calculated. All variables were explored by bivariate analysis for each gender. Next, we dichotomized the variables representing support or lack of support for FOBT and colonoscopy into two categories: "Feeling reluctant" (this category included: "No, I would not do it" and "I am not sure") and "Would support" (this category included: "Yes, I would do it"). Bivariate analysis was performed using these new variables without any change in the initial categories of the other variables. Next, two logistic regression analyses were performed; the first used support or lack of support for FOBT as the dependent variable, and the second support or lack of support for colonoscopy. In both equations, all independent variables had p-values of < 0.1 upon bivariate analysis. Backward logistic regression analysis was next performed. Independent variables were excluded from the model when no statistically significant relationships with the dependent variable were evident, and when the estimated coefficients did not change markedly from those yielded in the previous model employing the variable. Each new model was compared with the previous model by calculation of a likelihood ratio. SPSS version 13.0 for Windows was used for all statistical analysis.

Results

We collected 625 completed questionnaires from 24 PHC healthcare centers in the Balearic Islands and from 36 PHC centers in Barcelona. A total of 34 patients (5.2%), 67.6% of whom were male with a mean age of 58.6 years, refused to participate. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of participating patients. One in three (33%) participants reported visiting a healthcare center often or very often in the previous year, 43% from time-to-time, 21% occasionally, whereas 2% had not visited a center during the previous year. Most participants reported that they had high or very high confidence in PHC doctors and nurses (78% for each question).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Variables | Categories | Cases (N = 625) | Valid % | Women % (N = 361) | Men % (N = 261) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 50-54 | 123 | 19.7 | 22.4 | 15.7 |

| 55-59 | 143 | 22.9 | 24.1 | 21.1 | |

| 60-64 | 177 | 28.3 | 28.5 | 28.0 | |

| 65-69 | 182 | 29.1 | 24.9 | 35.2 | |

| Region | Balearic islands | 254 | 40.6 | 42.2 | 37.2 |

| Barcelona | 371 | 59.4 | 56.8 | 62.8 | |

| Educational level | < Elementary school | 121 | 19.7 | 22.7 | 15.9 |

| Elementary school | 385 | 62.7 | 63.2 | 62.0 | |

| High school | 73 | 11.9 | 9.1 | 15.5 | |

| Bachelor's degree | 35 | 5.7 | 5.1 | 6.6 | |

| Job situation | Active | 242 | 39.0 | 35.5 | 43.2 |

| Not active | 378 | 61.0 | 64.5 | 56.8 | |

| Smoking | Yes | 98 | 15.8 | 12.2 | 20.8 |

| No | 519 | 83.4 | 87.2 | 78.0 | |

| Eats fruit daily | Yes | 584 | 93.7 | 93.1 | 94.6 |

| No | 39 | 6.3 | 6.9 | 5.4 | |

| Eats vegetables daily | Yes | 549 | 88.3 | 93.1 | 94.6 |

| No | 73 | 11.7 | 10.0 | 13.8 | |

| Practices physical activity Daily | Yes | 486 | 78.3 | 76.3 | 81.2 |

| No | 134 | 21.6 | 23.7 | 18.5 | |

| Chronic health problem | Yes | 452 | 77.7 | 77.1 | 78.6 |

| No | 123 | 21.1 | 21.7 | 20.2 | |

| Don't know | 7 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | |

| Type of chronic health problem | Hypertension | 330 | 52.8 | 52.1 | 54.4 |

| Diabetes | 175 | 28.0 | 22.4 | 35.6 | |

| Depression | 79 | 12.6 | 17.5 | 6.1 | |

| Anxiety | 66 | 10.6 | 13.9 | 6.1 | |

| Heart failure | 32 | 5.1 | 3.0 | 8.0 | |

| Renal failure | 14 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 3.4 | |

| Asthma | 27 | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.2 | |

| COPD | 22 | 3.5 | 1.7 | 6.1 | |

| Irritable bowel | 16 | 2.6 | 3.0 | 1.1 | |

| Diverticulosis | 12 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 1.1 | |

| Ulcerative colitis | 4 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 | |

| History of polyps | Yes | 30 | 4.8 | 5.8 | 3.5 |

| No | 567 | 91.3 | 90.9 | 91.8 | |

| Don't know | 24 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 4.7 | |

| History of cancer | Yes | 62 | 10.1 | 10.4 | 9.8 |

| No | 540 | 88.1 | 87.3 | 89.0 | |

| Don't know | 11 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 1.2 | |

| Type of cancer | Breast | 20 | - | 5.5 | - |

| Skin | 13 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 3.1 | |

| Urinary bladder | 4 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 1.5 | |

| Lung | 2 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | |

| Prostate | 8 | - | - | 3.1 | |

| Other | 11 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 2.3 | |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | Yes | 108 | 17.5 | 21.1 | 12.5 |

| No | 472 | 77.1 | 74.4 | 80.8 | |

| Don't know | 33 | 5.4 | 4.5 | 6.7 | |

Table 2 shows respondent knowledge about cancer in general and CRC in particular. Most patients knew that many cancers could be avoided by giving up smoking and that diagnosis before symptom occurrence improved the chance of survival. However, only half of all respondents knew that more than 50% of CRC patients survive for 5 years after diagnosis or that exercise could help prevent CRC. It was also known that many cancers could be avoided by eating more fruit and vegetables and that intestinal polyps must be removed because they can become cancerous. Women had more knowledge of CRC symptoms than did men, and they were aware of the significance of bloody stools, diarrhea, and constipation, but not of other signs and symptoms, such as weight loss, tenesmus, and abdominal pain.

Table 2.

Knowledge about cancer and colorectal cancer

| Questions | Answers | Total % (N = 625) | Women % (N = 361) | Men % (N = 261) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| There are many types of cancer | Trae | 94.3 | 95.0 | 93.5 | 0.729 |

| False | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.4 | ||

| I don't know | 5.3 | 4.8 | 6.2 | ||

| Some cancers can be cured | Trae | 93.2 | 93.8 | 92.3 | 0.617 |

| False | 3.4 | 2.8 | 4.2 | ||

| I don't know | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.5 | ||

| Cancer is a fatal disease | Trae | 27.9 | 27.0 | 29.1 | 0.801 |

| False | 65.4 | 65.9 | 64.7 | ||

| I don't know | 6.7 | 7.1 | 6.2 | ||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by doing more exercise | Trae | 45.1 | 39.4 | 53.1 | 0.003 |

| False | 17.1 | 18.7 | 15.0 | ||

| I don't know | 37.7 | 41.9 | 31.9 | ||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by giving up smoking | Trae | 92.2 | 90.2 | 95.0 | 0.065 |

| False | 2.8 | 3.1 | 2.3 | ||

| I don't know | 5.0 | 6.7 | 2.7 | ||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by eating more fruits and vegetables | Trae | 69.9 | 68.8 | 71.3 | 0.266 |

| False | 7.5 | 8.9 | 5.4 | ||

| I don't know | 22.7 | 22.3 | 23.3 | ||

| Cancer diagnosis before symptoms can improve chances of survival | Trae | 88.2 | 88.5 | 87.7 | 0.476 |

| False | 1.0 | 0.6 | 1.5 | ||

| I don't know | 10.8 | 10.9 | 10.7 | ||

| More than half of colorectal cancer cases survive five years after diagnosis | Trae | 44.7 | 45.3 | 43.8 | 0.759 |

| False | 7.6 | 8.1 | 6.9 | ||

| I don't know | 47.7 | 46.6 | 49.2 | ||

| Intestinal polyps must be removed because they can become a cancer | Trae | 64.2 | 66.8 | 60.6 | 0.224 |

| False | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.3 | ||

| I don't know | 33.2 | 30.4 | 37.1 | ||

| Which of the following symptoms indicate a colorectal cancer | Bloody stools | 72.2 | 76.5 | 66.3 | 0.006 |

| Diarrhea-Constipation | 42.9 | 48.5 | 35.2 | 0.001 | |

| Abdominal pain | 23.6 | 24.1 | 23.0 | 0.775 | |

| Headache | 8.8 | 8.0 | 10.0 | 0.475 | |

| Fatigue | 37.9 | 39.6 | 35.6 | 0.317 | |

| Paleness | 32.0 | 34.3 | 28.7 | 0.163 | |

| Difficulty swallowing | 13.8 | 13.9 | 13.8 | 1.000 | |

| Weight loss | 55.6 | 61.5 | 47.5 | 0.001 | |

| Burning stomach | 15.6 | 14.7 | 16.9 | 0.502 | |

| Tenesmus | 22.2 | 24.9 | 18.4 | 0.063 | |

| Pain during defecation | 36.2 | 37.1 | 34.9 | 0.612 | |

| I don't know | 20.9 | 17.2 | 26.1 | 0.009 | |

A total of 82% of women and 38% of men had participated in screening tests for prevention of some type of cancer. Among women, 83.1% had undergone mammography, 68.1% cytology tests, 16.3% colonoscopies, 9.4% FOBTs, and 8.3% CT scans. Of all men, 36.4% had undergone PSA tests, 10.7% colonoscopies, 8.8% FOBTs, and 6.5% CT scans.

Patients were asked how they would respond if a PHC doctor or nurse proposed that an FOBT be performed for CRC screening. A total of 88.8% of participants reported that they would undergo the test, 7.3% were not sure, and 3.9% indicated they would not. If the FOBT was positive and a colonoscopy was offered, 84.9% of participants reported that they would undergo the procedure, 5.9% were not sure, and 9.2% would not. Responses did not differ significantly between gender.

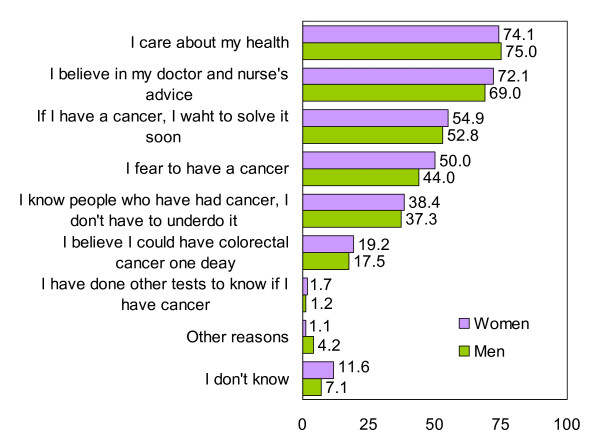

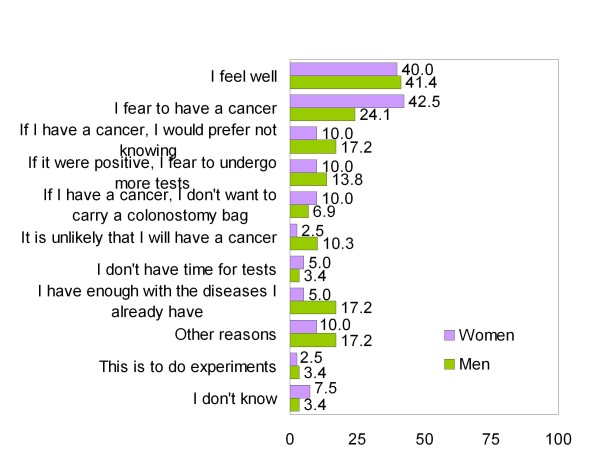

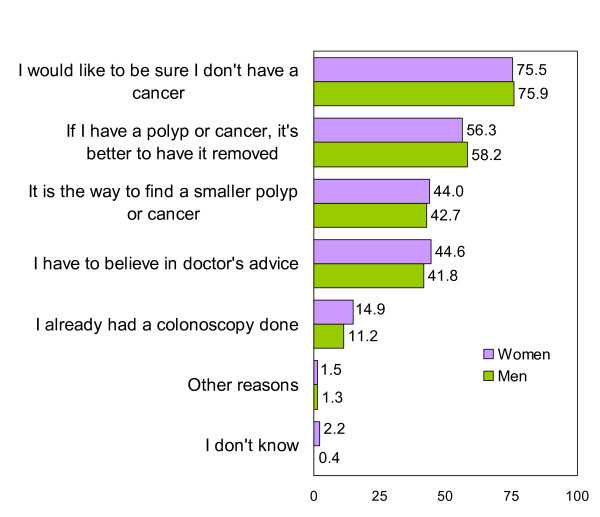

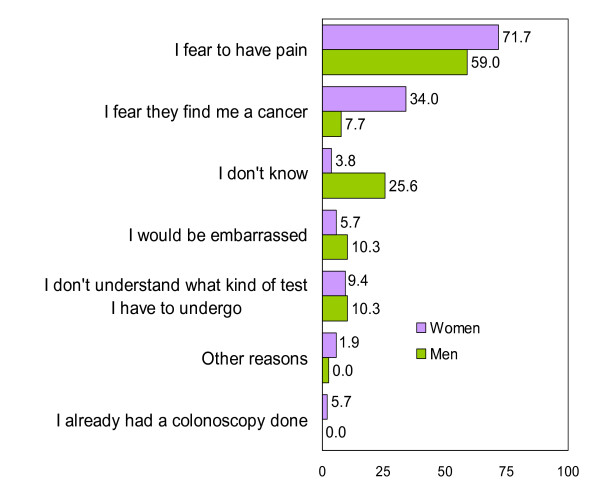

Patients reported that their main reasons for performing the FOBT were that they cared about their health and that they believed in advice received from doctors and nurses (Figure 1). The main reasons why patients would not perform the FOBT were that they felt well and feared discovering cancer (Figure 2). Women reported cancer fears somewhat more frequently than did men, although the difference was not significant. Less than 20% of participants reported that they felt susceptible to CRC. The main reasons for undergoing colonoscopy were to seek reassurance that cancer was absent and the belief that, if a polyp or cancer was present, treatment was necessary (Figure 3). Fear of pain was the main reason for not undergoing colonoscopy, especially among women (Figure 4).

Figure 1.

Reasons for performing a FOBT in % (Only participants that would do it or doubt = 599).

Figure 2.

Reasons for not performing a FOBT in % (Only participants that wouldn't perform it or doubt = 69).

Figure 3.

Reasons for undergoing a colonoscopy (Only participants that would undergo it or doubt = 558).

Figure 4.

Reasons for not undergoing colonoscopy (Only participants that wouldn't undergo it or doubt = 92).

Bivariate analysis indicated that several factors were associated with reluctance to perform the FOBT (Table 3) and to undergo colonoscopy if the FOBT was positive (Table 4). In both instances, the knowledge that many forms of cancer can be prevented by performing more exercise and that cancer diagnosis before symptom onset can improve survival were associated with favorable views on the FOBT and colonoscopy. Knowledge of the main symptoms of colorectal cancer; experience with any screening test for cancer prevention; and a positive attitude toward colonoscopy (when FOBT was explored) or toward FOBT (when colonoscopy was explored) were the main factors associated with reluctance to undergo FOBT or colonoscopy.

Table 3.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated (p < 0.1) with being reluctant to perform a FOBT for colorectal cancer early diagnosis

| Variables | Categories | Reluctant (%) | Would support (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Job situation | Active | 7.5 | 92.5 | 0.019 | |

| Not active | 13.6 | 86.4 | |||

| Educational level | < Elementary school | 16.8 | 83.2 | 0.082 | |

| Elementary school | 10.4 | 89.6 | |||

| High school | 5.5 | 94.5 | |||

| Bachelor's degree | 14.3 | 85.7 | |||

| There are many types of cancer | True | 10.3 | 89.7 | 0.044 | |

| False + don't know | 22.9 | 77.1 | |||

| Cancer is a fatal disease | True + don't know | 14.2 | 85.8 | 0.080 | |

| False | 9.5 | 90.5 | |||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by doing more exercise | True | 5.1 | 94.9 | 0.000 | |

| False + don't know | 15.9 | 84.1 | |||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by giving up smoking | True | 10.0 | 90.0 | 0.013 | |

| False + don't know | 22.9 | 77.1 | |||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by eating more fruits and vegetables | True | 9.0 | 91.0 | 0.012 | |

| False + don't know | 16.2 | 83.8 | |||

| Cancer diagnosis before symptoms can improve survival | True | 9.0 | 91.0 | 0.000 | |

| False + don't know | 26.8 | 73.2 | |||

| Intestinal polyps must be removed, because they can become cancer | True | 8.4 | 91.6 | 0.010 | |

| False + don't know | 15.3 | 84.7 | |||

| Any screening test done for cancer prevention | Yes | 8.6 | 91.4 | 0.014 | |

| No | 15.5 | 84.5 | |||

| PSA test done for cancer prevention | Yes | 5.2 | 94.8 | 0.051 | |

| No | 12.2 | 87.8 | |||

| FOBT done for cancer prevention | Yes | 1.8 | 98.2 | 0.014 | |

| No | 12.1 | 87.9 | |||

| Which of the following symptoms indicate a colorectal cancer | Bloody stools | Yes | 8.4 | 91.6 | 0.001 |

| No | 18.2 | 81.8 | |||

| Diarrhea-Constipation Yes | 7.4 | 92.6 | 0.010 | ||

| No | 14.0 | 86.0 | |||

| Abdominal pain | Yes | 6.1 | 93.9 | 0.034 | |

| No | 12.7 | 87.3 | |||

| Fatigue | Yes | 7.6 | 92.4 | 0.035 | |

| No | 13.3 | 86.7 | |||

| Weight loss | Yes | 8.9 | 91.1 | 0.055 | |

| No | 13.9 | 86.1 | |||

| Burning stomach | Yes | 5.1 | 94.9 | 0.036 | |

| No | 12.2 | 87.8 | |||

| Tenesmus | Yes | 3.6 | 96.4 | 0.001 | |

| No | 13.3 | 86.7 | |||

| Pain during defecation | Yes | 5.3 | 94.7 | 0.000 | |

| No | 14.5 | 85.5 | |||

| I don't know | Yes | 18.6 | 81.4 | 0.004 | |

| No | 9.1 | 90.9 | |||

| In case FOBT were + and a colonoscopy were recommended, would you accept to undergo it? | Yes | 5.2 | 94.8 | 0.000 | |

| No + I doubt | 44.6 | 55.4 | |||

Table 4.

Bivariate analysis of factors associated (p < 0.1) with being reluctant to undergo a colonoscopy for colorectal cancer early diagnosis

| Variables | Categories | Reluctant (%) | Would support (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Balearic Islands | 10.0 | 90.0 | 0.004 | |

| Barcelona | 18.4 | 81.6 | |||

| Job situation | Active | 11.8 | 88.2 | 0.082 | |

| No active | 17.2 | 82.8 | |||

| There are many types of cancer | True | 14.2 | 85.8 | 0.028 | |

| False + don't know | 28.6 | 71.4 | |||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by doing more exercise | True | 10.4 | 89.6 | 0.008 | |

| False + don't know | 18.1 | 81.9 | |||

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by eating more fruits and vegetables | True | 12.9 | 87.1 | 0.026 | |

| False + don't know | 20.1 | 79.9 | |||

| Cancer diagnosis before symptoms can improve chances of survival | True | 12.4 | 87.6 | 0.000 | |

| False + don't know | 35.7 | 64.3 | |||

| More than half of cases of colorectal cancer survive 5 years after diagnosis | True | 10.7 | 89.3 | 0.009 | |

| False + don't know | 18.5 | 81.5 | |||

| Intestinal polyps must be removed, because they can become cancer | True | 12.1 | 87.9 | 0.017 | |

| False + don't know | 19.5 | 80.5 | |||

| Any screening test done for cancer prevention | Yes | 12.7 | 87.3 | 0.067 | |

| No | 18.7 | 81.3 | |||

| Colonoscopy done for cancer prevention | Yes | 3.4 | 96.6 | 0.001 | |

| No | 16.9 | 83.1 | |||

| CT done for cancer prevention | Yes | 4.3 | 95.7 | 0.032 | |

| No | 15.9 | 84.1 | |||

| Which of the following symptoms indicate a colorectal cancer | Bloody stools | Yes | 11.9 | 88.1 | 0.001 |

| No | 23.4 | 76.6 | |||

| Diarrhea-Constipation | Yes | 10.9 | 89.1 | 0.012 | |

| No | 18.2 | 81.8 | |||

| Abdominal pain | Yes | 10.3 | 89.7 | 0.084 | |

| No | 16.5 | 83.5 | |||

| Fatigue | Yes | 9.4 | 90.6 | 0.002 | |

| No | 18.4 | 81.6 | |||

| Paleness | Yes | 10.1 | 89.9 | 0.021 | |

| No | 17.3 | 82.7 | |||

| Difficulty swallowing | Yes | 7.1 | 92.9 | 0.032 | |

| No | 16.2 | 83.8 | |||

| Weight loss | Yes | 12.0 | 88.0 | 0.022 | |

| No | 18.8 | 81.2 | |||

| Burning stomach | Yes | 7.2 | 92.8 | 0.019 | |

| No | 16.4 | 83.6 | |||

| Tenesmus | Yes | 6.5 | 93.5 | 0.001 | |

| No | 17.4 | 82.6 | |||

| Pain during defecation | Yes | 8.0 | 92.0 | 0.000 | |

| No | 19.0 | 81.0 | |||

| I don't know | Yes | 24.4 | 75.6 | 0.002 | |

| No | 12.5 | 87.5 | |||

| Would you accept to perform a FOBT for colorectal screening? | Yes | 9.3 | 90.7 | 0.000 | |

| No + I doubt | 60.3 | 39.7 | |||

Multivariate analysis indicated that patients who did not know that many cancers can be prevented by performing more exercise, and those who would not undergo colonoscopy if an FOBT was positive, were more reluctant to perform the FOBT for CRC screening (Table 5). With respect to colonoscopy, participants from Barcelona who did not know that early diagnosis of CRC was associated with improved prognosis, those who had never had colonoscopies, and those who would not perform the FOBT for CRC screening, were more reluctant to undergo colonoscopy.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with being reluctant to do a FOBT and a colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening*

| Variable | Categories | β | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Being reluctant to perform a FOBT | |||||

| Labour situation | Active | 1 | |||

| No active | 0.641 | 0.072 | 1.914 | 0.044-3.880 | |

| Many cancer cases could be avoided by doing more exercise | True | 1 | |||

| False + don't know | 1.155 | 0.002 | 3.174 | 1.542-6.532 | |

| FOBT done for cancer prevention | Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 2.032 | 0.061 | 7.631 | 0.912-63.822 | |

| Bloody stools is a symptom of colorectal cancer | Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 0.617 | 0.066 | 1.853 | 0.960-3.579 | |

| If FOBT were positive, would you accept to undergo a colonoscopy? | Yes | 1 | |||

| No + I doubt | 2.603 | 0.000 | 13.507 | 7.144-25.536 | |

| Being reluctant to undergo a colonoscopy | |||||

| Region | Balearic Islands | 1 | |||

| Barcelona | 0.798 | 0.012 | 2.220 | 1.188-4.149 | |

| Cancer diagnosis before symptoms can improve chances of survival | True | 1 | |||

| False + don't know | 0.822 | 0.023 | 2.276 | 1.117-4.635 | |

| More than half of cases of colorectal cancer survive 5 years after diagnosis | True | 1 | |||

| False + don't know | 0.500 | 0.101 | 1.649 | 0.907-2.997 | |

| Colonoscopy done for cancer prevention | Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 1.478 | 0.022 | 4.383 | 1.238-15.514 | |

| Fatigue is a symptom of colorectal cancer | Yes | 1 | |||

| No | 0.505 | 0.106 | 1.657 | 0.898-3.058 | |

| Would you accept to perform a FOBT for colorectal screening? | Yes | 1 | |||

| No + I doubt | 2.726 | 0.000 | 15.272 | 7.852-29.703 | |

* Nagelkerke's R2: 0.352 for being reluctant to do a FOBT and 0.323 for being reluctant to do a colonoscopy

Discussion

We examined the extent of knowledge about CRC in PHC patients from two regions of Spain, and the attitudes toward CRC and screening for the cancer. Our results indicate that knowledge about CRC in the general population could be improved, but that attitudes toward the FOBT and colonoscopy were generally positive. Our results also indicated some differences between men and women in attitudes toward CRC screening. This issue will be more thoroughly explored, in a qualitative manner, during the next phase of our study.

Our patients showed clear gaps in knowledge about CRC prevention and symptoms, as also reported in previous studies [7,8,14]. Women had a better knowledge of CRC symptoms and men had more knowledge of CRC prevention. A previous study in the United Kingdom also found that women had more knowledge about CRC than did men [7]. Although a general knowledge of CRC is not enough to raise CRC awareness to the level required for participation in screening programs, such knowledge has been reported as essential for development of a positive attitude toward screening programs in some studies [7,16], but not in others [17].

Most of our PHC patients (88.8%) reported that they would support a population-based screening program for CRC that employed the FOBT followed by colonoscopy in instances of FOBT-positivity. The proportion of responsive PHC patients in the United Kingdom was similar [7], but fewer patients in Japan responded positively [16]. However, an intention to undergo CRC screening is not the same as actual participation in such screening. In particular, Herbert et al. showed that whereas over 80% of participants expressed an intention to participate in a CRC screening program, only 40% actually participated [12]. Thus, it is possible that our results were influenced by social desirability bias (over-reporting of expected behavior) and by the administration of the questionnaire in healthcare centers.

One limitation of the present study is that our PHC patients may not be representative of the general population of Spain, the true target of population-based CRC screening. Spain has a free public healthcare system that covers 99% of the population. Thus, although our participants may not reflect the general population, they may be representative of those of lower socioeconomic status, and such subjects would benefit most from a campaign seeking to improve awareness of CRC screening [7].

In the present study, women reported more prior experience with cancer screening than did men. This reflects the existence of well-established screening programs for breast and cervical cancer. Thus, we expected to find differences between men and women regarding intention to participate in a CRC screening program [18], but we in fact found no gender-based difference in this variable, unlike what was noted in studies in the United Kingdom [19] and Catalonia [20], both of which reported higher participation by women in CRC screening programs.

Fear of being diagnosed with cancer, and of pain during colonoscopy, were the principal reasons given, especially by women, for not wishing to participate in CRC screening. These observations agree with those of other studies [17,21] and with the views held by PHC professionals about their patients [11]. Also, patients perceived that the risk of developing CRC was low, as has also been observed in previous studies [8]. We found no between-gender difference in perceived fear of CRC, in contrast to the results of a previous qualitative study which found that women believed that CRC was more common in men, and the women thus felt less vulnerable to this cancer [22].

Factors associated with a positive attitude toward the FOBT and colonoscopy were diverse in nature and included knowledge about CRC primary prevention, of the symptoms of CRC, and of the benefits afforded by CRC screening. Moreover, positive attitudes toward the FOBT and colonoscopy were associated, and vice versa. Previous studies also found that the perceived benefits and barriers were the main factors associated with an intention to undergo colonoscopy after a positive FOBT [16]. In one previous work, compliance with the advice of the PHC doctor was associated with intention to perform the FOBT for colorectal cancer screening, and also with actual FOBT completion [12]. Another qualitative study found that lack of trust in doctors was a barrier to CRC screening [15]. In the present work, we found no association between a positive attitude toward CRC screening and patient confidence in the PHC doctor or nurse. We suggest further exploration of this issue, because previous experience has shown that PHC doctors play key roles in developing patient willingness to participate in CRC screening [23].

Our results showed that the knowledge that physical activity could protect against CRC was associated with a positive attitude toward the FOBT. Also, we observed that an understanding that early diagnosis of CRC is associated with better prognosis was associated with a positive attitude toward colonoscopy if an FOBT was positive. It is noteworthy that one-third of our subjects did not know that polyps should be removed because they can become cancerous. Together, our results indicate that developing knowledge on CRC preventability should be a key plank in the design of an awareness program promoting CRC population-based screening, as has been noted previously [17].

Conclusions

In summary, the present study has shown that PHC patients have knowledge gaps with respect to both the nature and prevention of CRC. Addressing patient cancer fears and emphasizing that CRC is preventable will be key elements in the successful promotion of CRC screening.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

MR, EC, ME, JMT, JMV, JL and GA designed the study; MR and ML led development of the projects in the Balearic Islands and Barcelona, respectively; MMR, XC, MS, and MT coordinated study work in their respective areas. MR and ME performed the statistical analysis, and MR drafted the manuscript. ME, EC, MM, MMR, XC, MS, GA, MT, JMT, JMV, JL and ML critically reviewed the draft and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Maria Ramos, Email: mramos@dgsanita.caib.es.

Maria Llagostera, Email: mllagostera.cp.ics@gencat.cat.

Magdalena Esteva, Email: mesteva@ibsalut.caib.es.

Elena Cabeza, Email: ecabeza@dgsanita.caib.es.

Xavier Cantero, Email: fxcantero.cp.ics@gencat.cat.

Manel Segarra, Email: msegarra@ambitcp.catsalut.net.

Maria Martín-Rabadán, Email: mmartinrabadan@ibsalut.caib.es.

Guillem Artigues, Email: gartigues@dgsanita.caib.es.

Maties Torrent, Email: maties.torrent@hgmo.es.

Joana Maria Taltavull, Email: jtaltavull@ibsalut.caib.es.

Joana Maria Vanrell, Email: jmvanrell@dgsanita.caib.es.

Mercè Marzo, Email: mmarzoc@gencat.cat.

Joan Llobera, Email: jllobera@ibsalut.caib.es.

Acknowledgements

This study received two grants from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias [Health Research Fund] of Spain's Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo [Ministry of Health and Consumer Affairs] (nos. PI 07/905 and PI 07/90696). The work also received funding from the Red de Investigación en Promoción de la Salud y Actividades Preventivas de Atención Primaria [Health Promotion and Primary Care Prevention Activities Research Network] (red IAPP), supported by Spain's Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo (no. ISCIII-RETCI RD 06/0018), and from the Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Ciencias de la Salud [University Institute for Health Sciences Research] (IUNICS).

References

- Centro Nacional de Epidemiología. Instituto de Salud Carlos III. La situación del cáncer en España. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- López-Abente G, Ardanaz E, Torrella-Ramos A, Mateos A, Delgado-Sanz C. Chirlaque MD for the Colorectal Cancer Working Group. Changes is colorectal cancer incidence and mortality trends in Spain. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 3):iii76–iii92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winawer S, Faivre J, Selby J, Bertaro L, Chen THH, Kroborg O, Levin B, Mandel J, O'Morain C, Richards M, Rennert G, Russo A, Saito H, Semigfnovsky B, Wong B, Smith R. Workgroup II: the screening process. UICC International Workshop on Facilitating Screening for Colorectal Cancer, Oslo, Norway (29 and 30 June 2002) Ann Oncol. 2005;16:31–3. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulard H Boussac-Zarebska M Bloch J Epidemiological assessment of the pilot programme for organized colorectal cancer screening, France, 2007 Bulletin épidémiologique hebdomadaire 20092-322–5.21934590 [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Beliefs, attitudes, intentions and behavior. New York: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Oranizational Behav Human Decis Proc. 1991;50:179–211. doi: 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffery K, Wardle J, Waller J. Knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral intentions in relation to the early detection of colorectal cancer in the United Kingdom. Prev Med. 2003;36:525–35. doi: 10.1016/S0091-7435(03)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa A, Abbate R, Di Giuseppe G, Marinelli P, Angelillo IF. Knowledge, attitudes, and preventive practices about colorectal cancer among adults in an area of Southern Italy. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:171. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gili M, Roca M, Ferrer V, Obrador A, Cabeza E. Psychosocial factors associated with the adherence to a colorectal cancer screening program. Cancer Detect & Prev. 2006;30:354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sach TH, Whynes DK. Men and women: beliefs about cancer and about screening. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:431. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos M, Esteva M, Almeda J, Cabeza E, Puente D, Saladich R, Boada A, Llagostera M. Knowledge and attitudes of primary health care physicians and nurses with regard to population screening for colorectal cancer in Balearic Islands and Barcelona. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:500. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herbert C, Launoy G, Gignoux M. Factors affecting compliance with colorectal cancer screening in France: differences between intention to participate and actual participation. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1997;6:44–52. doi: 10.1097/00008469-199702000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton WR, Balanda KP, Gillespie AM, Lowe JB, Baade PD. Measurement of community beliefs about colorectal cancer. Social Sci & Med. 2000;50:1655–63. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00395-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel V, Gray R, Chart P, Fitch M, Saibil F, Zdanowicz Y. Perspectives on colorectal cancer screening: a focus group study. Health Expect. 2004;7:51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2003.00252.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser KE, Allanan JZ, Fletcher RH, Good MD. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening in community health centers: A qualitative study. BMC Family Practice. 2008;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng YF, Saito T, Takahashi M, Ishibashi T, Kai I. Factors associated with intentions to adhere to colorectal cancer screening follow-up exams. BMC Public Health. 2006;6:272. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg DS, Miller S, Rodoletz M, Egleston B, Fleisher L, Buzaglo J, Keenan E, Marks J. Colorectal cancer knowledge is not associated with screening compliance or intention. J Cancer Educ. 2009;24(3):225–32. doi: 10.1080/08858190902924815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sach TH, Whynes DK. Men and women: beliefs about cancer and about screening. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:431. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller D, Coleman D, Robertson R, Butler P, Melia J, Campbell C, Parker R, Patnick J, Moss S. The UK colorectal cancer screening pilot: results of the second round of screening in England. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1601–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris M, Espinàs JA, Muñoz L, Navarro M, Binefa G, Borràs JM. Catalan Colorectal Cancer Screening Pilot Program Group. Lessons learnt from a population-based pilot program for colorectal screening in Catalonia (Spain) J Med Screen. 2007;14:81–6. doi: 10.1258/096914107781261936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg DS, Turner BJ, Wang H, Myers RE, Miller S. A survey of women regarding factors affecting colorectal cancer screening compliance. Prev Med. 2004;38:669–675. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedemann-Sánchez G, Griffin JM, Partin MR. Gender differences in colorectal cancer screening barriers and information needs. Health Expect. 2007;10:148–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2006.00430.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiatt R, Wardle J, Vernon S, Austoker J, Bistanti L, Fox S, Gnauck R, Iverson D, Mandelson M, Reading D, Smith R. Workgroup IV: public education. UICC International Workshop on Facilitating Screening for Colorectal Cancer, Oslo, Norway (29 and 30 June 2002) Ann Oncol. 2005;16:38–41. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]