Abstract

Context:

An intensive care unit (ICU) admission of a patient causes considerable stress among relatives. Whether this impact differs among populations with differing sociocultural factors is unknown.

Aims:

The aim was to compare the psychological impact of an ICU admission on relatives of patients in an American and Indian public hospital.

Settings and Design:

A cross-sectional study was carried out in ICUs of two tertiary care hospitals, one each in major metropolitan cities in the USA and India.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 90 relatives visiting patients were verbally administered a questionnaire between 48 hours and 72 hours of ICU admission that included the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) for post-traumatic stress response.

Statistical Analysis:

Statistical analysis was done using the Mann-Whitney and chi-square tests.

Results:

Relatives in the Indian ICU had more anxiety symptoms (median HADS-A score 11 [inter-quartile range 9-13] vs. 4 [1.5-6] in the American cohort; P<0.0001), more depression symptoms (BDI-II score 14 [8.5-19] vs. 6 [1.5-10.5], P<0.0001) but a comparable post-traumatic stress response (IES-R score>30). 55% of all relatives had an incongruous perception regarding “change in the patient's condition” compared to the objective change in severity of illness. “Change in worry” was incongruous compared to the perception of improvement of the patient's condition in 78% of relatives.

Conclusions:

Relatives of patients in the Indian ICU had greater anxiety and depression symptoms compared to those in the American cohort, and had significant differences in factors that may be associated with this psychological impact. Both groups showed substantial discordance between the perceived and objective change in severity of illness.

Keywords: Anxiety, depression, family, psychological, stress disorders, stress, traumatic

Introduction

Admission of a patient to an intensive care unit (ICU) has considerable psychological impact on their relatives.[1] Studies in American hospitals have shown anxiety symptoms in 10-42% and depression symptoms in 16-35% of relatives of critically ill patients.[2–4] A higher prevalence was seen in a study of 78 French ICUs; of the 544 relatives studied, 73% had anxiety symptoms, and 35% depression symptoms.[5] Nearly 5 million patients are admitted to an ICU in India every year.[6] Yet, studies exploring its psychological impact on their relatives are scant.[7,8] In one study, post-traumatic stress symptoms were observed in 79% of 199 relatives of ICU patients in an Indian hospital.[7] Although these psychological effects decrease over time, they may persist for 6 months to 2 years.[1–3,7]

Many factors influence the psychological impact of an ICU admission on relatives.[1,9] Patient-related factors include severity of illness, younger patient age, long-standing illness, and patient's death. Family-related factors include being a female relative and/or being a spouse of the patient. ICU-related factors include having more than one patient in a room, involving relatives in the decision-making process, and the ICU staff being perceived as “not comforting” or “having provided incomplete information.”[1,5,10,11]

Educational, economic and sociocultural factors, and differences in healthcare systems may also influence the psychological impact of an ICU admission on relatives. These factors differ considerably in developing versus economically developed countries. For example, India has a literacy rate of 66%, an annual per capita income of Rs. 38,084 ($778) with government expenditure on healthcare being only 2% of gross domestic product (GDP).[12] In comparison, the United States has a literacy rate of 99%, an annual per capita income of $46,000 with 25% of GDP spent on healthcare.[13] Less than 10% of Indians have medical insurance whereas after including Medicare and Medicaid, only 15-16% of the US population remains completely uninsured.[14,15] The family structure, cultural beliefs, and coping mechanisms differ between these two countries.[16]

If all these differences are actually contributing to the impact, then they should be considered when designing strategies to reduce the psychological impact of an ICU admission in different populations. Hence, we prospectively studied anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms in relatives of patients admitted to an ICU in two such discrepant cohorts, United States and India, in similar publicly funded hospitals that primarily serve the “working poor.” The primary objective was to determine the difference in the psychological impact in relatives of patients in these two cohorts. The secondary objective was to identify differences between the cohorts in factors that have already been shown to influence the psychological impact, and uncover cohort-specific factors that might contribute to the impact.

Materials and Methods

The Institutional Ethics Committee/Institutional Review Board of both hospitals approved the study protocol. Answering the questionnaire implied consent to participate in the study.

Hospitals

Both selected sites were major national tertiary care referral centers. The American hospital was a 586-bed county hospital in the southern USA. The Indian hospital was a municipally funded 1800-bed university hospital and a major referral center for critically ill cases around western India.[17] The hospital selected in the United States is one of two county hospitals in southern USA. The 16-bed Medical Intensive Care Unit (MICU) and the adjacent 9-bed Coronary Care Unit (CCU) are closed ICUs with approximately 1200 admissions annually. An intensivist, two critical care fellows, four internal medicine senior residents, and four interns staff the MICU. Each patient is cared for in an individual room. The hospital selected in India is a municipally funded 1800-bed university hospital. It is one of the major tertiary referral centers for critically ill cases from hospitals in western India. The multidisciplinary ICU in it is a closed unit with 17 beds and receives 1100 admissions annually. A team of two attending intensivists, six ICU senior residents, and three interns manage the patients. Patients are divided between three rooms, and each patient bed is separated from the other by a thick plastic curtain. The diagnostic facilities available at both hospitals and the doctor-patient ratio are comparable. The nurse-patient ratio in the American ICU is 1:2 and in the Indian ICU is 1:4. A waiting room for visitors is available outside both the ICUs and a private meeting room is generally used for formal family meetings.

Participants

The relatives of consecutive patients admitted to each MICU (next-of-kin and/or primary contact) were invited to participate in the study. Relatives aged 18 or older who were contacted between 48 hours and 72 hours of the patient's ICU admission were included.[4,5] Relatives were excluded if patients were admitted to any hospital for > 72 hours prior to the interview and later shifted to the ICU, or if patients died within 48 hours of admission. Relatives were also excluded if they were non-English speaking (in the USA) or did not speak English, Hindi (the national language), or Marathi (the regional language) in India. We contacted the relatives either in the hospital or via telephone, and upon consent, an interview was conducted at a mutually convenient time in person. Participants were allowed to voluntarily opt out of the study at any point.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of demographic information of both patient and relative, an assessment of the relative's knowledge regarding the patient's condition, their perception of the prognosis and change in the patient's condition since admission, and scales to assess the psychological impact. Anxiety symptoms were identified when participants scored > 10 on the anxiety component of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).[18,19] Depression symptoms were identified when participants scored > 13 on the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II).[20] We also included the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) to assess for three domains of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS; avoidance, intrusion, and hyper-arousal) present since the relatives’ ICU admission.[21] A total score >30 was used to identify relatives with significant PTSS.[1,11]

Scales

Hospital anxiety and depression scale

The HADS is a 14-item scale with seven items each in two subscales for evaluation of symptoms of anxiety (HADS-A) and depression (HADS-D).[1,18] It detects symptoms of anxiety and depression, rather than making a diagnosis of the syndrome, and excludes symptoms that may arise from physical illness, insomnia, or fatigue.[1] The participant responds to each question in the context of how they felt in the previous week, or in the case of our study, the time since the patient's ICU admission. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 to 3, and the scores range from 0 to 21 in each subset (HADS-A and HADS-D), representing severity of the emotional symptoms. A HADS-A score of > 10 indicates “presence” of anxiety symptoms and a score between 8 and 10 is “suggestive” of anxiety symptoms.[18,19] The HADS has been validated and used previously in other Indian languages, including Punjabi and Malayalam.[6,37,38] It has been also used to identify symptoms in family members of ICU patients in other countries and to study the effects of interventions designed to reduce the psychological impact of a patient's death on their family members.[1,4,5]

Beck depression inventory-II

The BDI-II is a 21-item questionnaire that assesses the somatic, affective, and cognitive symptoms due to depression.[39] It is also useful to assess feelings of helplessness and potential self-harm (suicidal ideation). Participants answer questions based on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (extreme form of each symptom) - for our study, relating to the time since the ICU admission - and scores range from 0 to 63.[19] A score > 13 indicates ‘presence’ of depression symptoms, while a score > 29 reveals “severe depression.”[20] Like the HADS, the BDI-II has been validated and used in the Indian population.[40,41] It has also been used to identify depressive symptoms in family members of ICU patients in different countries.[4,5]

Impact of event scale-revised

The IES-R is a 22-item questionnaire that can help to identify subjective distress caused by a traumatic event, and comprises three sub-scores or domains.[1,21] The intrusion sub-score consists of 7 items and evaluates repetition of thoughts and impressions related to the event; the avoidance sub-score consists of 8 items and evaluates effortful avoidance of situations or people that serve as reminders of the traumatic event; the hyper-arousal sub-score consists of 7 items and evaluates physiological symptoms of hyper-arousal when thinking of the event. In the context of our study, participants were asked to relate to the ICU admission (the single stressful life event) and indicate how many times they experienced the specific item: 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Hence, total IES-R scores ranged from 0 to 88, and the IES sub-scores were derived by dividing the total score in a subgroup by the total number of items in it.

Though it cannot be used to conclusively diagnose post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a cut-off score of > 30 (considered a “high IES-R score”) is considered a reliable cut-off score for preliminary diagnosis, and hence, we used it for a comparison of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) between the two cohorts.[1] The IES-R has been previously used in relatives visiting a critically ill patient, even in an Indian cohort.[7,11,22]

Adapting the questionnaires for the study population

The HADS and IES-R were translated by a professional translator into the local Indian languages (Hindi and Marathi) that are commonly spoken among people visiting the Indian hospital. These were translated back into English by a psychiatrist, an intensivist, an internal medicine resident, a medical student, and a nonmedical person. These back-translations were compared to the original English questionnaire by us to achieve face and content validity of the Hindi and Marathi questionnaires. Only the original English version was used in the American ICU. Validated versions of BDI-II in all three languages were purchased from NCS Pearson, Inc., Chicago, IL.

Two medical students verbally administered the questionnaires. To ensure uniformity in interviews, both were trained simultaneously for this purpose, but one student interviewed all relatives in the USA and one interviewed all relatives in India. Interviews occurred in separate meeting rooms at both the hospitals to ensure privacy, and lasted for 30-45 minutes. However, relatives were allowed to sit by the patient if they wished to. They had the option of not answering any of the questions and were allowed to withdraw from the interview at any time. Those who met criteria for anxiety/depression symptoms (HADS ≥ 11 and/or BDI-II >13 and/or a suicidal tendency) were offered referral to a counselor/psychiatrist.

In order to study the relatives’ understanding of the patient's illness, we compared their subjective perception of the change in the patient's condition with the objective change in the patient's clinical status. For assessing subjective perception, relatives were asked if they felt that their patient's condition was “better,” “same,” or “worse” compared to admission. “The change in the APACHE II score” was used as an objective assessment of the change in the severity of the illness of the patient from admission till the time of interview. An increase or decrease of > 2 in the score was considered “significant.”

Relatives were also asked whether their level of worry since the patient's admission had “decreased,” “remained the same,” or “increased.” These responses were interpreted as “appropriate worry” if the worry was congruous with the perceived change in the patient's condition (i.e., worry increased when patient's condition was perceived as “worse,” worry decreased when patient's condition was perceived as “better,” or both “remained the same”). “Inappropriate worry” was defined as inconsistency between “change in worry” and “change in perception of patient's condition.”

Statistical methods

Nonparametric results were expressed as [median, inter-quartile range (IQR)]. The prevalence of psychological symptoms was expressed as proportions. The Mann-Whitney test and chi-square tests were used to determine statistical significance. Microsoft Excel 2008 (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) and GraphPad Instat 3.1 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) were used to analyze data. A two-sided P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses.

Results

We enrolled 50 consecutive relatives each from the American ICU (referred to as “USA” henceforth) and the Indian ICU (referred to as “India” henceforth). Of those, 43 from USA and 47 from India agreed to interview. Ten refused, five because they were “too emotional” (three in USA, two in India), three who were “not interested” (two in USA, one in India) and two who were unable to come to the ICU within 72 hours of the patient's admission (both from USA).

Psychological impact

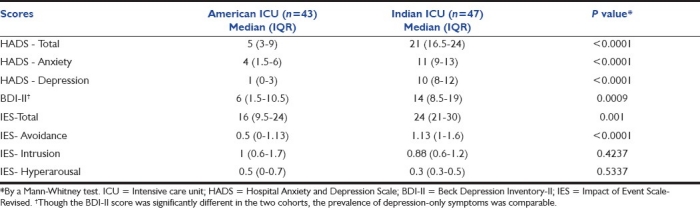

The median HADS score (overall and both the anxiety and depression sub-score), BDI-II score, and IES-R-avoidance sub-score were significantly higher in relatives in the Indian ICU compared to those in the American ICU [Table 1]. However, IES-R sub-scores on intrusive and hyper-arousal thoughts were comparable in the two groups.

Table 1.

Comparison of the psychological impact of an ICU admission of a patient on their relatives in an American and an Indian public hospital

Anxiety symptoms alone (only HADS-A > 10) were present in 21% of relatives in India (10/47) compared to none in USA. Depression symptoms alone (only BDI-II > 13) were present in 28% in India (13/47) and 14% in USA (6/43). Anxiety and depression together were present in 30% in India (14/47) versus 5% (2/43) in USA (P=0.002; RR=6.4, 95%CI: 1.5-26.6). Thus, anxiety and/or depression symptoms were present in 79% (37/47) of the Indian cohort compared to only 18% (8/43) of the American cohort (P<0.0001; RR=4.23, 95% CI 2.23-8.05). None of the participants had severe depressive symptoms (BDI-II >29), but seven in India and two in USA had considered suicide and were referred for counseling. Though overall scores in the Indian cohort were significantly higher [Table 1], post-traumatic stress “response” (IES-R > 30) did not differ between relatives in India (23%; 11/47) and USA (14%; 6/43) (P=0.29).

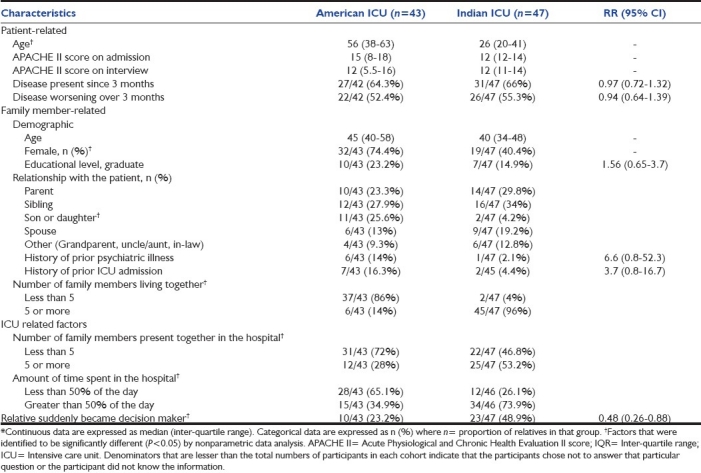

Differences between patients and their relatives in the Indian and American ICU

Patients in the Indian ICU were much younger than those in the American ICU [Table 2]. The APACHE-II scores both on admission and at the time of interview, presence of chronic disease (defined as “disease process existing for > 3 months”) and the proportion of patients with worsening of illness since 3 months were comparable [Table 2].

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients and their relatives admitted to the ICU in an American and an Indian public hospital*

Age and educational status of relatives, and proportion of relatives who had stayed with the patient for at least 6 months, were comparable in both ICUs; however, more female relatives were present in the American ICU [Table 2]. While parents and siblings were similarly represented, children were significantly lesser in the Indian cohort (4.2% vs. 25.6% in USA; P=0.0057). Relatives in the Indian cohort had a significantly larger family size, and more relatives were present in the hospital [Table 2]. The time spent in the hospital per day was significantly greater among relatives in the Indian cohort; 74% spent more than half their day in the hospital compared to only 35% of relatives in USA (P=0.0003; RR=2.12; 95% CI 1.36-3.3).

A large proportion of relatives in both ICUs rated the “need for financial assistance” as either 3 (important) or 4 (very important) [Likert scale 1-4]. However, nearly 81% of those in USA rated the need as “very important” compared to only 38% in India (P≤0.0001; RR=2.1; 95% CI 1.4-3.1). The need for a counselor/psychiatrist to deal with the psychological impact was felt as either “important/very important” by 46% of those in USA versus 13% in India (P=0.0008; RR=3.6; 95% CI 1.6-8.2); 57% of those in India considered it “not important at all.”

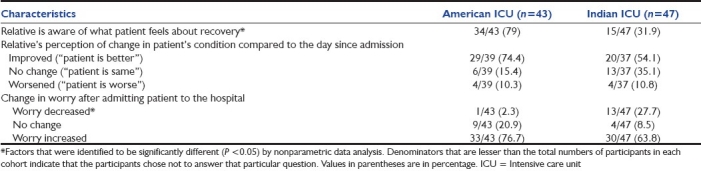

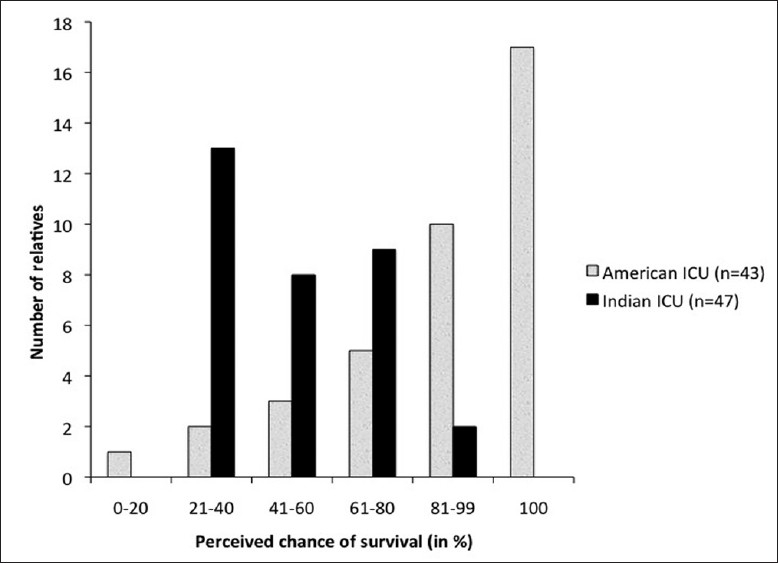

A significantly larger number of relatives in the American cohort felt they were aware of what the patient felt about his/her recovery [Table 3], and were more optimistic of the survival of the patient [Figure 1]. Seventy-four percent of all relatives in the American ICU (32/43) expressed that the patient had > 60% chance of survival, compared to only 23% of relatives (11/47) in the Indian ICU (P<0.0001; RR=3.18; 95% CI 1.84-5.49) [Figure 1]. Importantly, 40% of relatives in USA expressed that their patient had a 100% chance of survival compared to none of the relatives in India. Interestingly, 32% (15/47) of relatives in India chose not to answer this question compared to only 12% (5/43) in USA.

Table 3.

Comparison of the subjective factors contributing to the psychological impact of an ICU admission of a patient on their relatives in an American and an Indian public hospital

Figure 1.

Likelihood of the patient's survival as perceived by the relatives of patients admitted to an Intensive care unit (ICU) in an American and an Indian public hospital

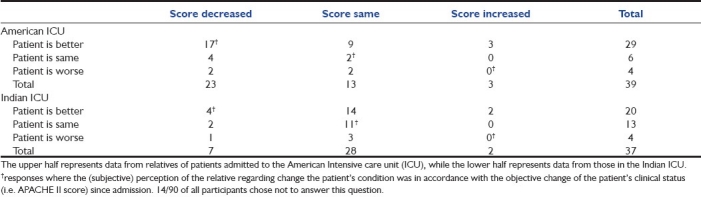

Inappropriate worry

From the day of admission till the time of interview, APACHE II scores improved in 39%, and were unchanged in 54% and worsened in 7% of 75 total patients in both ICUs [pooled from Table 4]. Concomitantly, 64% of their relatives felt that the patient's condition was better, 25% felt it was unchanged while 11% felt it was worse compared to the previous day [Table 3]. This perception was comparable among family members of patients in both ICUs [Table 3]. However, the relative's perceptions paralleled the changes in APACHE II scores in less than 50% of cases in either ICU [Table 4]. Among all relatives, 37% (28/76) perceived that the patient had improved more than was reflected by the change in the APACHE II score (“inappropriate optimism”) while 18% (14/76) perceived that the patient had improved less than what was actually reflected by the change in the APACHE II score (“inappropriate pessimism”). Fourteen relatives chose not to answer these questions.

Table 4.

Comparison between change in the patient's APACHE II score since admission (columns) and perception of the relative regarding change in the patient's condition since the previous day (rows)*

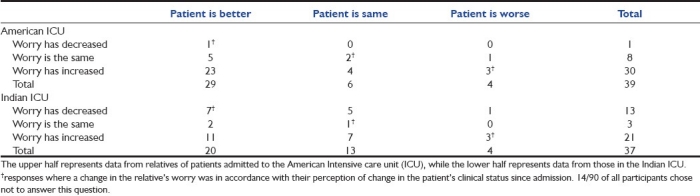

Relatives were also asked if their worry since admission had changed [Table 3]. Only 18% of all relatives (14/76) said their worry had “decreased,” 15% (11/76) said it “remained the same” while 67% (51/76) said it had “increased.” Interestingly, worry among relatives in the Indian ICU decreased after hospital admission (28% vs. 2% in USA, P=0.0009; RR=0.084; 95% CI 0.01-0.616) [Table 3].

“Appropriate worry,” defined as the worry that was congruent to the perceived change in the patient's condition, was seen in only 15% of relatives in the American ICU and 30% of relatives in the Indian ICU [Table 5]. Of the remaining, 68% had “inappropriately high worry” while 9% had “inappropriately low worry.” Fourteen relatives chose not to answer this question. Relatives with a higher psychological impact had a significantly greater tendency for inappropriately high worry (unpublished data).

Table 5.

Comparison between the perception of the relatives regarding change in the patient's condition (columns) and the change in their worry since the patient's admission (rows)*

Discussion

Previous studies from France,[5,10,11] Greece,[22] and United States[2–4] showed that early anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms are common among relatives of ICU patients; however, all previous studies were based on cohorts from a single country. Our study for the first time made a head-to-head comparison of the psychological impact of an ICU admission on relatives of critically ill patients in two countries with widely differing social, cultural, and economic environments. Moreover, it was the first study that explored both anxiety and depression symptoms in relatives of critically ill patients in an Indian ICU, and found these symptoms to be substantially more common in them compared to those in an American ICU. In our study, factors associated with the prevalence of anxiety or depressive symptoms included patient-related factors, relative-related demographics, and educational status, perception of prognosis and desire for psychological as well as financial assistance. These could explain the difference in prevalence of anxiety in our two cohorts. Some of these have already been shown to affect the psychological impact.[5,7,9–11] Patients in our Indian ICU were much younger than those in the American ICU, similar to previous studies where the age of Indian ICU patients ranged between 34-41 years compared to 61-84 years in USA.[3,28–32] Female relatives in the American cohort were significantly more than those in the Indian cohort. Female gender of relatives is an independent predictor of the psychological impact of an ICU admission.[11,27] Also the proportion of spouses - the ones maximally affected by the stress of the ICU admission - was almost equal.[5,10,11,27] In spite of this, psychological distress was significantly greater in Indian cohort in our study, suggesting that there may be other factors that have a stronger impact.

Relatives in our Indian cohort had a greater mean household size, concordant with census data that showed the mean Indian household size is 4.8 versus 2.6 in USA.[33–35] We also found that more relatives of Indian patients were present together in the hospital compared to those of the US patients. Indians seem to have a deep sense of familial belonging; financial, psychological, and social support from all relatives is common.[36] This also may explain why relatives of Indian patients in our cohort spent a greater proportion of their day in the hospital. However, while having many relatives in the hospital is helpful, it can also be counterproductive, because family support can either be “positive” (interactions providing affect, affirmation or aid) or “problematic” (when relatives share information or make suggestions that are unhelpful, upsetting, or try to change the way of coping with illness); precisely how this large number directly influences psychological distress is an area for further research.[37]

A significantly greater proportion of relatives in the American cohort felt they knew what the patient felt about his/her recovery compared to those in the Indian cohort. Also although no formal study exists among families of Indian patients, in one study, only 9% of immigrant Asian Hindus in the United States had some form of advanced directives, compared to the national average of 15-20%.[38] Interestingly, in many Asian cultures, beneficence is valued over patient autonomy, and relatives hope that physicians will promote hope rather than burdening the suffering patient with the additional stress of end-of-life discussions.[38,39] Additionally, we found that siblings and children of patients in the Indian cohort would often request us not to inform other relatives regarding the patient's condition; this was uncommon in the American cohort. These beliefs and practices of limited discussions regarding end-of-life illness may partly explain the difference in the understanding of the patients’ perception of illness between our two cohorts.

Relatives’ perception of the risk of the patient's death can be an important determinant of their response to an ICU admission. We found that APACHE II scores, which objectively quantify risk of death, were comparable in the two groups. Yet, relatives in the American cohort were more optimistic about recovery. This can be partly explained by the prior positive communication to the relatives by the patient. Additionally, Hindus perceive illness to be a result of prior actions (karma).[36] The less-optimistic relatives of Indian ICU patients clearly had a greater psychological burden. Paradoxically, more family members from the American cohort expressed a need for a counselor to deal with the perceived stress, and a greater need for financial assistance, while most relatives in the Indian cohort felt that a counselor/psychiatrist was not necessary. Reluctance to seek psychiatric or psychological assistance among the traditional Indian society has been highlighted before.[40] Interestingly, relatives in the Indian cohort worried lesser after the ICU admission compared to those in the American cohort. This may represent transference of responsibility of decision-making related to the patient's “care” from the family member to the physician.[36] Whether interventions focused on identifying and reconciling suppressed thoughts are useful in similar cohorts should be explored.

Ours is the first study to show that nearly 3 out of 4 relatives of ICU patients experience “inappropriate worry.” Also, many of them chose not to answer questions about changes in their worry and perceived changes in patient's condition. This could signify either an avoidance response or a lack of understanding of the patient's clinical condition. Earlier studies have reported that after a meeting with the physician regarding the patient's condition, 54% of relatives failed to comprehend the diagnosis, prognosis or treatment of the patient,[10] and post-traumatic stress increased when this information was perceived as “incomplete.”[11] This highlights the importance of ICU personnel ensuring that relatives actually understand changes in the clinical status of the patient and the physicians’ perception of the patient's survival. This may play an important role in reducing stress.

Limitations

Our study has a few limitations. First, we only included English-speaking relatives in our American cohort, which could have led to a relative under representation of other ethnicities in our study. Second, the study was conducted in ICUs only from one representative public hospital in both countries that were expected to reasonably represent the population that utilizes healthcare services offered by their public health systems. Those utilizing private hospitals in the USA and India may differ significantly from those utilizing public hospitals and hence, more studies are needed before generalizing results.[14,41] Although the ICUs were matched for most criteria, patients in our American ICU were cared for in individual rooms while most in the Indian ICU shared a large room and were separated from each other by movable curtains. Hence, relatives were often able to see other critically ill patients as well. A previous study has shown that having more than one bed in an ICU room may be associated with depression symptoms.[5] However, we found the prevalence of depression-only symptoms was comparable. The loss of limb or loss of cognitive/physical function can also affect the psychological response to illness, and is not considered when the APACHE-II score is used. This may have impaired objective assessment of the severity of the patient's condition in our study.

Conclusions

We found that prevalence of anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress symptoms are significantly greater in relatives of patients admitted to the ICU of an Indian public hospital compared to a similar American cohort. When taking differences in the cohorts into consideration, factors that are significantly associated with this impact include age of the patient, differences in family structure, time spent in the hospital, relatives’ understanding of the patient's thoughts about recovery, the change in their worry since the patient's hospital admission and their own perception of the patient's survival. A noteworthy gap exists between many relatives’ perceptions of the patients’ illness compared to the objectively measured severity, as well as the worry that they experience. This discrepancy may have an impact on the stress experienced by these relatives and the causes should be further investigated. Measures can then be designed to bridge the gap and ensure better communication between healthcare personnel in the ICU and relatives of critically ill patients, and mitigate incongruous stress. Finally, qualitative research is needed to identify the unmet needs that contribute to the stress in such culturally and economically diverse groups. This could help devise cohort-specific strategies to help people in different countries better deal with the acute psychological impact of a severe illness in a close relative.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Kentish-Barnes N, Lemiale V, Chaize M, Pochard F, Azoulay E. Assessing burden in families of critical care patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(10 Suppl):S448–56. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b6e145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, Bryce CL. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1871–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, Loseth DB, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1722–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guntupalli KK, Rebbapragada VR, Lodhi MH, Bradford S, Burruss J, McCabe D, et al. Anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress reactions in relatives of intensive care unit patients. Chest. 2007;132(4 Suppl):549–50S. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pochard F, Darmon M, Fassier T, Bollaert PE, Cheval C, Coloigner M, et al. Symptoms of anxiety and depression in family members of intensive care unit patients before discharge or death. A prospective multicentric study. J Crit Care. 2005;20:90–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jayaram R, Ramakrishnan N. Cost of intensive care in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;12:55–61. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.42558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pillai LV, Ambike D, Husainy S, Vaidya N, Kulkarni SD, Aigolikar S. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in relatives of severe trauma patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2006;10:181–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pillai L, Aigalikar S, Vishwasrao SM, Husainy SM. Can we predict intensive care relatives at risk for posttraumatic stress disorder? Indian J Crit Care Med. 2010;14:83–7. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.68221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulkarni HS. Less-obvious predictors of post-ICU informal caregiver burden. Chest. 2010;138:1024–5. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azoulay E, Chevret S, Leleu G, Pochard F, Barboteu M, Adrie C, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3044–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, Chevret S, Aboab J, Adrie C, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:987–94. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 2010. Mar 2, [Last cited on 2011 Apr 28]. UNICEF - India - Statistics. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/india_statistics.html . [Google Scholar]

- 13.New York: United Nations Children's Fund; 2010. Mar 2, [Last cited on 2011 Apr 28]. UNICEF - At a glance: United States of America - Statistics. Available from: http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/usa_statistics.html . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapadia F, Singh M, Divatia J, Vaidyanathan P, Udwadia FE, Raisinghaney SJ, et al. Limitations and withdrawal of intensive therapy at the end of life: practices in intensive care units in Mumbai, India. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1272–5. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165557.02879.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danis M, Linde-Zwirble WT, Astor A, Lidicker JR, Angus DC. How does lack of insurance affect use of intensive care? A population-based study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2043–8. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000227657.75270.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blank RH, Merrick JC. End-of-life decision making: a cross-national study. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munnur U, Karnad DR, Bandi VD, Lapsia V, Suresh MS, Ramshesh P, et al. Critically ill obstetric patients in an American and an Indian public hospital: comparison of case-mix, organ dysfunction, intensive care requirements, and outcomes. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:1087–94. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2710-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio (TX): Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–18. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane DA, Jajoo J, Taylor RS, Lip GY, Jolly K. Birmingham Rehabilitation Uptake Maximisation (BRUM) Steering Committee. Cross-cultural adaptation into Punjabi of the English version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas BC, Devi N, Sarita GP, Rita K, Ramdas K, Hussain BM, et al. Reliability and validity of the Malayalam hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in cancer patients. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:395–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smarr KL. Measures of depression and depressive symptoms: The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders-Mood Module (PRIME-MD) Arthritis Care Res. 2003;49:S134–46. doi: 10.1002/acr.20556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Basker M, Moses PD, Russell S, Russell PS. The psychometric properties of Beck Depression Inventory for adolescent depression in a primary-care pediatric setting in India. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2007;1:8. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta R, Dahiya S, Bhatia MS. Effect of depression on sleep: Qualitative or quantitative? Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:117–21. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.49451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paparrigopoulos T, Melissaki A, Efthymiou A, Tsekou H, Vadala C, Kribeni G, et al. Short-term psychological impact on family members of intensive care unit patients. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:719–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parikh CR, Karnad DR. Quality, cost, and outcomes of intensive care in a public hospital in Bombay, India. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:1754–9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199909000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Merchant M, Karnad DR, Kanbur AA. Incidence of nosocomial pneumonia in a medical intensive care unit and general medical ward patients in a public hospital in Bombay, India. J Hosp Infect. 1998;39:143–8. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90328-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agrawal R, Gupta D, Ray P, Aggarwal AN, Jindal SK. Epidemiology, risk factors and outcome of nosocomial infections in a Respiratory Intensive Care Unit in North India. J Infect. 2006;53:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rello J, Ollendorf DA, Oster G, Vera-Llonch M, Bellm L, Redman R, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a US database. Chest. 2002;122:2115–21. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milbrandt EB, Watson RS, Mayr FB, Angus DC, Hartman E, Wunsch H, et al. How big is critical care in the US? Crit Care Med. 2008;36(12 Suppl):A77. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mumbai, India: International Institute for Population Sciences; [Last cited 2011 Apr 28]. National Family Health Survey. Available from: http://www.nfhsindia.org/factsheet.html . [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soneja S, Nagarkar AK, Dey AB. Indian elderly: coping with chronic illness. J Hong Kong Geriatr Soc. 1999;9:10–3. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suitland (MD): United States Census Bureau; 2008. Dec 9, [Last cited on 2011 Apr 28]. United States – Fact Sheet – American Fact Finder. Available from: http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/SAFFFacts . [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandya SK. End-of-life decision making in India. In: Blank RH, Merrick JC, editors. End-of-life decision making: a cross-national study. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2005. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Revenson TA, Schiaffino KM, Majerovitz SD, Gibofsky A. Social support as a double-edged sword: the relation of positive and problematic support to depression among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33:807–13. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90385-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deshpande O, Reid MC, Rao AS. Attitude of Asian-Indian Hindus towards end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:131–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Searight HR, Gafford J. Cultural diversity at the end of life: issues and guidelines for family physicians. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:515–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chadda RK, Agarwal V, Singh MC, Raheja D. Help seeking behavior of psychiatric patients before seeking care at a mental hospital. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2001;47:71–8. doi: 10.1177/002076400104700406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Groeger JS, Strosberg MA, Halpern NA, Raphaely RC, Kaye WE, Guntupalli KK, et al. Descriptive analysis of critical care units in the United States. Crit Care Med. 1992;20:846–63. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199206000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]