Abstract

We report a case of dengue fever with features of encephalitis. The diagnosis of dengue was confirmed by the serum antibodies to dengue and the presence of a dengue antigen in the cerebrospinal fluid. This patient had characteristic magnetic resonance imaging brain findings, mainly involving the bilateral thalami, with hemorrhage. Dengue is not primarily a neurotropic virus and encephalopathy is a common finding in Dengue. Hence various other etiological possibilities were considered before concluding this as a case of Dengue encephalitis. This case explains the importance of considering the diagnosis of dengue encephalitis in appropriate situations.

Keywords: Bilateral thalamic involvement, dengue encephalitis, dengue fever

Introduction

The Dengue virus is a single-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family causing Dengue fever and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Encephalopathy is a very common neurological complication of dengue fever. Dengue encephalopathy is usually secondary to multisystem derangement like shock, hepatitis, coagulopathy, and concurrent bacterial infection.[1] Dengue encephalitis is a different entity, which occurs due to direct neuronal infiltration by the dengue virus.[2,3] We report a case of dengue shock syndrome with encephalitis, with peculiar MRI findings.

Case Report

A 17-year-old girl presented with a history of high-grade fever and rigors for three days. She had two episodes of vomiting, generalized headache, and altered sensorium, lasting for 15 to 20 minutes, few hours prior to admission. There was no significant past medical history.

On admission she was febrile, with a temperature of 101°F, pulse of 132 / minute, blood pressure of 90 / 40 mmHg (MAP-60 mmHg) and cold extremities. On pulse oximetry, oxygen saturation was 100% on breathing room air. There were no signs of respiratory distress. She was pale, and skin rash, edema, icterus, and clubbing were absent. There was no evidence of mucosal bleeding.

The neurological examination did not reveal any significant abnormality. There was no neck stiffness. The rest of the systemic examination was also within normal limits. There was no hepatosplenomegaly. She was resuscitated with fluids. First dose of third generation cephalosporin was given empirically in view of the possibility of bacterial infection. Empirical parenteral antimalarial preparation – artesunate was also given, in view of the possibility of cerebral malaria.

Investigations revealed hemoglobin (Hb) of 14.5 g / dl, Packed Cell Volume (PCV) of 45, White Blood Cell count (WBC) of 7100 / cumm, with neutrophils 64%, lymphocytes 34%, and monocytes 2%. The platelet count was 1.35 lacs / cumm and ESR was 48 mm at the end of one hour. Malaria antigen rapid test was negative. The liver enzymes were raised SGOT-220 U / L, SGPT-182U / L. Serum albumin was 3.65 gm / dl, and INR was 2.0. Blood urea nitrogen was 39 gm / dl with creatinine of 1.4 mg / dl. The electrolytes were within normal range. Serum ammonia was 23 mg/dl. There was evidence of metabolic acidosis with blood lactate 2.00 mmol / L on initial blood gas. No hypoxia or hypercapnia was seen; X- Ray chest and 2 D echocardiography were normal. Ultrasonography (USG) showed evidence of bilateral minimal pleural effusion with mild ascites.

The patient's blood pressure and urine output improved after initial resuscitation with crystalloids. A few hours later, this young girl had an episode of generalized tonic-clonic seizure with unresponsiveness. She was treated with lorazepam and fosphenytoin. She was intubated and ventilated in view of the poor level of consciousness after the seizure.

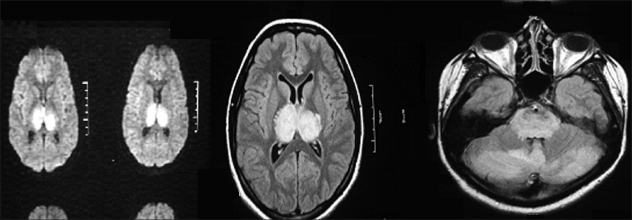

An MRI brain scan was done as an emergency. It showed [Figure 1] extensive parenchymal hyperintense lesions in the bilateral cerebellar cortex, vermis of the cerebellum, entire pons and midbrain, bilateral medial temporal lobes, and both thalami, on T2 and Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images. These lesions look hypointense on T1W images, hyperintense on FLAIR images, and dark on the ADC map. Small foci of hemorrhage in the thalamic lesions looking hypointense, were seen on the T2 GRE images. These features were suggestive of Japanese Encephalitis (JE). She was started on acyclovir with the possibility of Herpes simplex encephalitis.

Figure 1.

T 2 FLAIR and T2-weighted images showing involvement of thalamus, pons, and cerebellum, with presence of hemorrhage on T2 and restricted diffusion on DWI

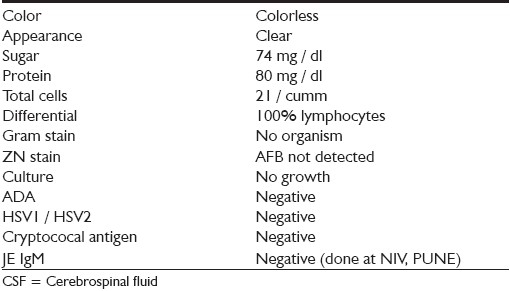

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis was done. The findings are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

CSF analysis report

IgG / IgM antibodies for Dengue were positive in the serum as also on the DNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Dengue. CSF analysis was positive for dengue IgM antibodies. Virus isolation was not possible.

IgM antibodies for Leptospira were negative. Chikungunya antibodies were negative. Titers for Hepatitis viruses were negative (HAV, HEV, HBsAg, HCV). Serum procalcitonin was 0.3 ng / ml (Negative less than 0.5 ng / ml). The blood and urine culture did not show any growth.

Her liver functions improved subsequently, and serum ammonia and electrolytes were within normal limits.

After the episode of seizure, her neurological status did not change. She remained comatose even after correction of shock, hepatitis, metabolic acidosis, and coagulopathy. The MRI brain findings were in favor of the possibility of direct extensive neuronal injury. Although the MRI brain findings were in favor of JE, CSF analysis was negative for JE. Therefore, the possibility of viral encephalitis due to dengue was strongly suspected. During the hospital course, she developed multiorgan dysfunction, shock, and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). She was ventilated according to the ARDS net protocol. She was started on steroids in view of the septic shock. Empirical antibiotics and antimalarials were continued till reports of the causative agent were obtained, and then withdrawn. Her coagulopathy was treated with fresh frozen plasma. Acyclovir was stopped on the basis of CSF analysis and MRI brain findings.

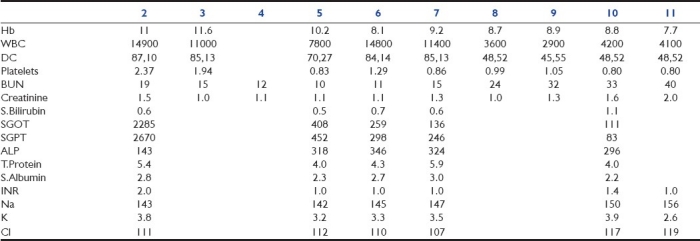

Table 2 shows her investigations over the next 10 days.

Table 2.

Investigations

In spite of all the treatment she continued to remain comatose, with hemodynamic compromise, and expired on the eleventh day after admission.

Discussion

Dengue virus infections are among the most common cause for hospital admissions in western Maharashtra. It is estimated that 50 to 100 million infections and 25,000 fatalities occur worldwide every year. The World Health Organization (WHO) surveillance shows that the global incidence is rising.[4] Numerous neurological manifestations like transverse myelitis,[2] myositis,[5] and Gullian-Barre syndrome[6] have been reported. Dengue encephalopathy is a well-recognized and common entity, the incidence ranging from 0.5 to 6.2 %.[5] The possible mechanisms are liver failure (hepatic encephalopathy), cerebral hypoperfusion (shock), cerebral edema (vascular leak), deranged electrolytes, and intracranial bleeding due to thrombocytopenia or coagulopathy, which is secondary to hepatic failure._[7] There are subsets of patients in whom the cause for neurological injury remains unclear even after excluding the above-mentioned indirect mechanisms. These raise the possibility of direct neuronal injury due to the dengue virus. Dengue is thought to be a non-neurotropic virus.[3] However, there are reports of the demonstration of dengue virus and IgM antigen in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with encephalopathy. There are case reports by Misra et al., from India,[5] and Solomon et al., from Vietnam.[2] In the study described by Misra et al.,[5] 11 patients were seen with confirmed dengue infection, but no CSF study was reported. Solmon et al.,[2] diagnosed dengue encephalitis in nine patients, but virus or antibody was found in the CSF of only two cases. Kankirawatana et al.[8] and Kularatne et al.,[9] had a similar study in which they showed the association of dengue with encephalitis.

On admission our patient had a history suggestive of encephalopathy with shock, coagulopathy, metabolic acidosis, and deranged liver functions. This encephalopathy is usually explained by the abnormalities mentioned earlier in the text. However, subsequent evaluation with positive MRI and CSF showed evidence of encephalitis. This showed the co-existence of encephalopathy and encephalitis. The MRI findings noted in our case are most characteristic of JE and not commonly seen with dengue fever.[10] The pattern of involvement. [bilateral thalamic involvement with foci of hemorrhage, with involvement of temporal lobe and brain stem] is very uncommon with dengue. There is only one similar case report by Kamble et al., with similar MRI findings.[10] This case is presented to highlight the possible extensive involvement of the brain by dengue virus.

Conclusions

Dengue is not classically a neurotropic virus, although there is recent evidence of direct neuronal injury. Dengue encephalitis must be thought of in differentials of encephalopathy, in patients with dengue. In such cases, neuroimaging and CSF analysis should be done whenever possible. The virus or antibody can be isolated from the serum, but the CSF samples may be negative. The dengue encephalitis is thought to be benign, but can be fatal at times. The role of an antiviral in such cases needs to be further defined because of the extensive parenchymal involvement and possible unfavorable outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Koley TK, Jain S, Sharma H, Kumar S, Mishra S, Gupta MD, et al. Dengue encephalitis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:422–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon T, Dung NM, Vaughn DW, Kneen R, Thao LT, Raengsakulrach B, et al. Neurological manifestations of dengue infection. Lancet. 2000;355:1053–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02036-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nathanson N, Cole GA. Immunosuppression and experimental virus infection of the nervous system. Adv Virus Res. 1970;16:397–428. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(08)60028-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dengue haemorrhagic fever; diagnosis, treatment, prevention, and control. Geneva: WHO; 2005. World Health Organisation. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misra UK, Kalita J, Syam UK, Dhole TN. Neurological manifestations of dengue virus infection. J Neurol Sci. 2006;244:117–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sulekha C, Kumar S, Philip J. Guillain-Barre syndrome following dengue fever. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:948–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Varatharaj A. Encephalitis in the clinical spectrum of dengue infection. Neurol India. 2010;58:585–91. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.68655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kankirawatana P, Chokephaibulkit K, Puthavathana P, Yoksan S, Somchai A. Dengue infection presenting with nervous system manifestation. J Child Neurol. 2000;15:544–47. doi: 10.1177/088307380001500809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kularatne SA, Pathirage MM, Gunasena S. A case series of dengue fever with altered consciousness and electroencephalogram changes in Sri Lanka. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102:1053–4. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamble R, Peruvamba JN, Kovoor J, Ravishankar S, Kolar BS. Bilateral thalamic involvement in dengue infection. Neurol India. 2007;55:418–19. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.37103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]