Abstract

The term stromal tumor was coined in 1983 by Clark and Mazur for smooth muscle neoplasm of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are nonepithelial tumors arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal, which express KIT protein-CD117 on immunohistochemistry. GIST can arise anywhere in the GIT, including the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum.

Keywords: Exophytic, GIST, immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Before 1983, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) were classified as smooth muscle tumors, along with leiomyoma, leiomyoblastoma, and leiomyosarcomas. With advances in electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry, it is now known that they are nonepithelial tumors arising from the interstitial cells of Cajal, which express KIT protein-CD117, a stem cell factor receptor, on immunohistochemistry.[1] They can arise anywhere along the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), including the stomach, small bowel, large bowel, mesentery, and omentum.[2–4] As most of them arise from the muscularis propria, the bulk of the mass grows exophytically rather than intraluminally or intramurally. This pictorial essay, based on our collection of cases over the last 6 years, aims to illustrate the computed tomography (CT) scan features of GIST confirmed by histopathology and immunohistochemistry (CD117)]. The emphasis is on atypical presentations of GIST and the other GIT neoplasms that can closely resemble GIST.

Epidemiology

The majority of GIST have a uniform appearance, falling into one of three categories: spindle cell, epitheloid cell, and mixed cell.[5] Ever since the classification of GIST as an entity distinct from leiomyomas, leiomyosarcomas, etc., there has been an increased interest in defining their imaging characteristics. It is estimated that approximately 5000–10,000 people are affected per year by this tumor all over the world.[6] There is no known association of GIST with geographic distribution, ethnicity, or race. Most GISTs are benign (70–80%). However, these tumors have a spectrum ranging from benign to malignant lesions, depending on the anatomic site, tumor size, and mitotic frequency.[1,2] Benign behavior is exceptionally common in gastric GIST, where benign lesions outnumber malignant ones by a ratio of 3–5:1.[2] Smaller tumors are likely to be benign.

Clinical features

The clinical findings vary depending on the location and size of the tumor at presentation. If the tumor is small, it may be only an incidental finding during radiological imaging or surgery for some other cause, whereas a large exophytic lesion may present as an abdominal mass due to its large size. Lesions in the stomach, small bowel, or colon may present with gastrointestinal bleed in the form of hematemesis, melena, or occult blood in stools; alternatively, there may be abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. An esophageal GIST most commonly presents with dysphagia.[7] GISTs generally occur with equal frequency in both the sexes, although some studies have shown a male preponderance.[8,9] They are common in the fourth and fifth decades of life.

Site

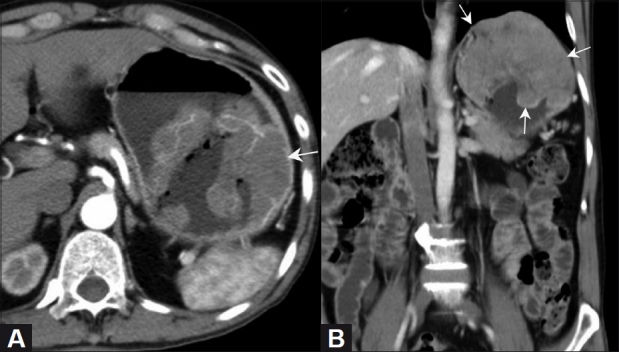

GISTs can arise anywhere along the GIT. In the esophagus, leiomyomas are more common than GIST;[7] however, in the stomach, small intestine, and colon, GISTS are the most common mesenchymal tumors.[2,10] Akwari et al.,[11] in their series, found that the largest numbers of tumors were from the stomach [Figure 1A and B], followed by the small intestine [Figure 2]. Tumors may also arise from the duodenum [Figure 3], large bowel, and even the peritoneum. Skandalak and Gray[12] in their study of 725 smooth muscle tumors of the GIT found that 47.3% of the tumors were from the stomach, 35.4% from the small intestine, 4.6% from the colon, and 7.4% from the rectum. On a barium meal examination, GIST are seen as submucosal masses, similar to leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas.[13] Ulcerations are better demonstrated on barium meal.

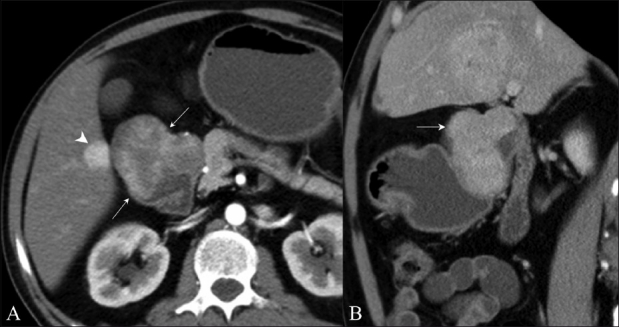

Figure 1 (A, B).

Gastric GIST. Axial (A) and coronal (B) contrast-enhanced CT scan in a 70-year-old male show a well-defined heterogeneously enhancing mass (arrow) in the stomach, with intraluminal and exophytic components, better defined on the coronal images. The left hemidiaphragm is raised

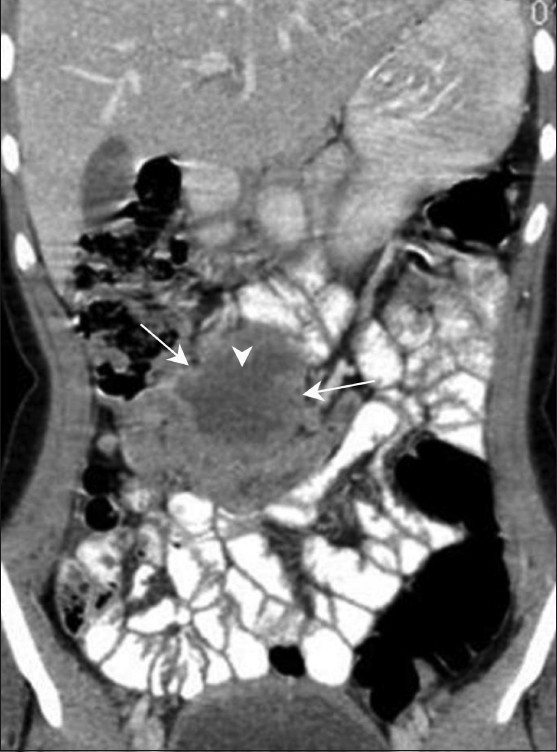

Figure 2.

Jejunal GIST. Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan in a 16-year-old girl shows an exophytic bowel mass (arrow) arising from the jejunal loops. There are areas of necrosis (arrowhead) but there is no evidence of bowel obstruction

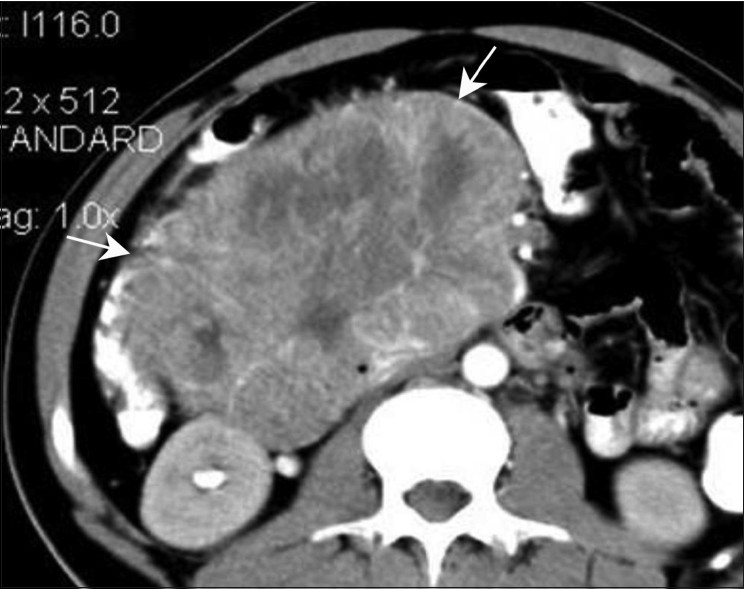

Figure 3.

Duodenal GIST. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in a 35-year-old female show a well-defined heterogeneously enhancing mass (arrow) along the second part of the duodenum

Imaging features

Because most of these tumors are submucosal in location, they usually attain a large size without causing bowel obstruction by the time of diagnosis.[6] Burkill et al. reported a mean diameter of 13 cm in their 116 cases of GIST. The margins of these tumors are well defined in about two-thirds of the cases.[14]

Many of these tumors have an exophytic component as they arise from the muscularis propria. Marla et al.[13] found that all tumors in their study were predominantly exophytic, except for four cases where the primary tumor could not be categorized because of extensive metastatic spread.

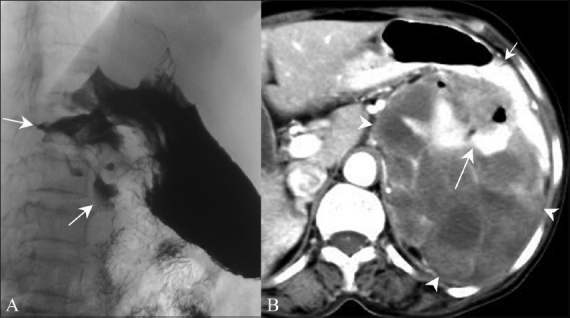

The enhancement pattern can vary from homogenously enhancing to heterogeneously enhancing, with or without ulceration. Lee et al. found GIST to be well-defined tumors with homogenous enhancement, while Levy et al.,[15] found large heterogeneously enhancing masses due to areas of necrosis or cystic degeneration. They described ulceration as a common feature of GIST [Figure 4A and B].

Figure 4 (A, B).

Malignant GIST. Barium meal study (A) shows an irregular filling defect along the fundus and greater curvature of the stomach, suggestive of ulceration (arrow). Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan (B) shows an exophytic heterogeneously enhancing mass (arrowhead) arising from the stomach (small arrow) with areas of ulceration (long arrow)

Atypical features

Peritoneal GIST [Figure 5], although described in the literature, are extremely rare.

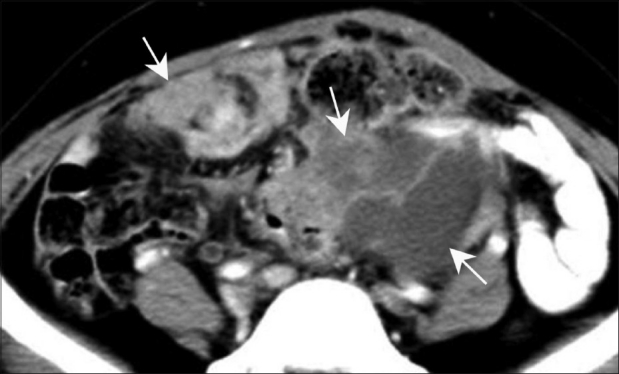

Figure 5.

Peritoneal GIST. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in 65-year-old male shows multiple heterogeneously enhancing peritoneal masses (arrows)

Lymph node metastases [Figure 6] are uncommon.[16,17] Out of four cases of lymph node metastases in the study by Marla et al., only one had lymphadenopathy with a short axis diameter of >10 mm. The standard treatment of GIST is complete surgical resection without regional lymphadenectomy.[18] In a study by Lee et al.,[14] lymphadenectomy was performed in 17 cases, but none of these patients were found to have lymph node metastases.

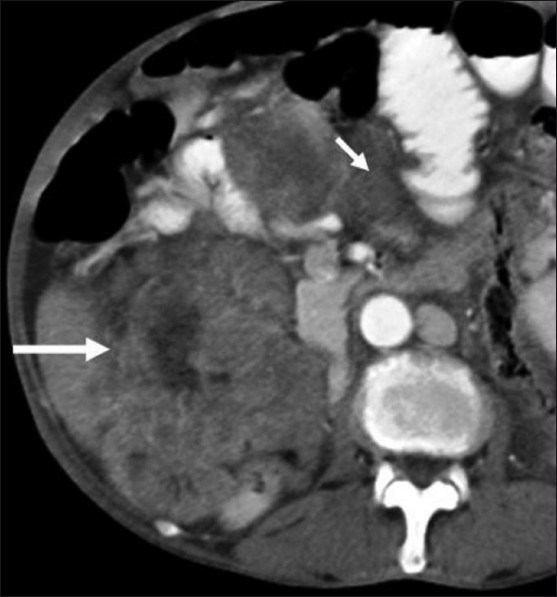

Figure 6.

GIST with lymphadenopathy. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in a 52-year-old male shows a lesser sac necrotic mass (small arrow) infiltrating the pancreas with lymphadenopathy (large arrow)

Cystic changes [Figure 7A and B] are not seen commonly, but have been reported in rapidly growing primary GIST.[19] These cystic lesions, depending on their location, may sometimes be misdiagnosed as pseudocyst of pancreas. Naitoh et al.[20] in a case report, described an exophytic GIST with remarkable cystic changes and speculated that as the tumor was large and exophytic, it may have caused congestion, edema, and hemorrhage, giving rise to a multiseptate appearance. They concluded that GIST should be considered when cystic tumors of unknown origin are found in the abdomen.

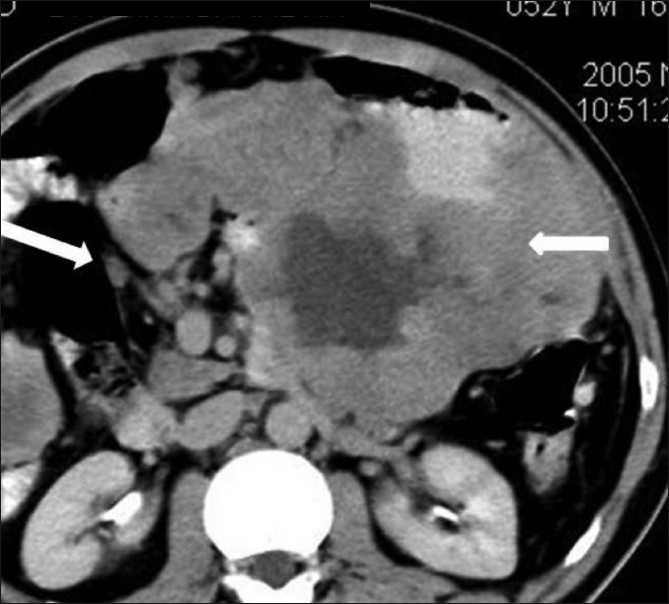

Figure 7 (A, B).

Cystic GIST. Longitudinal USG scan of the abdomen (A) in a 41-year-old male shows a predominantly cystic mass with septae (arrows) in the left hypochondrium. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan (B) shows a peripherally enhancing cystic mass (arrow) in the lesser sac region along the tail of the pancreas

Other atypical features described in the literature include aneurysmal dilatation of the small bowel, which is more common in lymphoma, and presence of nodular tumor or “satellite tumor” in the adjacent soft tissues. This satellite tumor may be because of local invasion or multiple tumors growing synchronously.[21] Bone metastases, although rare, have also been described.[22]

GIST are known to have rare associations with extra-adrenal paraganglioma and pulmonary chondroma (Carney Triad).[23] In a very small percentage of affected patients, they are also associated with adrenocortical adenoma and esophageal leiomyoma. GIST have also been noted in patients with ulcerative colitis.[24]

Metastases

Metastases from GIST commonly occur to the liver [Figure 8] and peritoneal cavity via hematogenous spread and peritoneal seeding. Occasionally, metastases occur to soft tissues, lungs, and pleura. Marla et al. also found that tumors that enhanced homogenously (nine out of 53 cases in their series) showed no metastases when they were followed for a mean period of 2.6 years as compared with those that enhanced heterogeneously. According to Nilsson et al.,[25] at least 50% of these tumors have metastasis at presentation.

Figure 8.

GIST with metastasis. Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan in a 39-year-old male operated for gastric GIST shows metastasis (arrow) in the left lobe of the liver

Differential diagnosis

Tumors to be considered in the differential diagnosis of GIST include adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, peritoneal carcinomatosis, carcinoid, metastases, and other mesenchymal neoplasm, e.g. leiomyoma.

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma is seen as an irregular mucosal or polypoidal growth, with or without intestinal obstruction [Figure 9], and is commonly associated with lymphadenopathy, metastases, or ascites. In contrast, GIST has a predominant exophytic component and does not cause intestinal obstruction; it displaces rather than invades the surrounding structures.

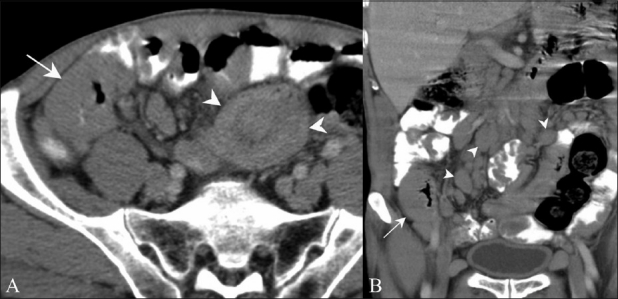

Figure 9.

Adenocarcinoma. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in a 65-year-old female presenting with pain in the abdomen show a large heterogenous mass lesion (arrows) arising from the jejunal loops with para-aortic lymph nodes (arrowheads). No proximal obstruction is seen

Lymphoma

Lymphoma is seen commonly in the stomach and small bowel. There is usually circumferential wall thickening or aneurysmal dilatation of bowel loops, with abdominal lymphadenopathy [Figure 10A and B]. The presence of lymphadenopathy is an important feature differentiating lymphoma from GIST. There may be secondary lymphomatous involvement of the liver and spleen in these cases.

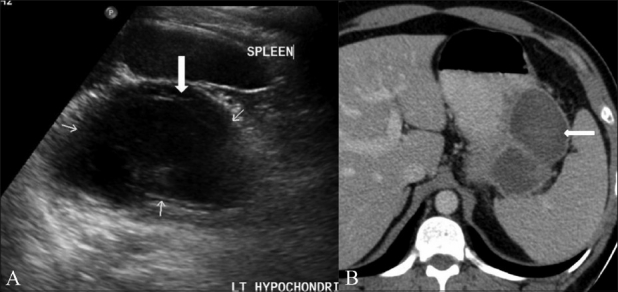

Figure 10 (A, B).

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) Lymphoma. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan (A) in a 67-year-old male presenting with generalized lymphadenopathy shows bowel wall thickening (arrow) along with intussusception (arrowhead). Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan (B) of the same patient shows bowel wall thickening (arrow) with multiple enlarged lymph nodes (arrowheads)

Peritoneal carcinomatosis

In peritoneal carcinomatosis, there are multiple lesions with omental caking, ascites, and lymphadenopathy [Figure 11] in the presence of a known primary, like carcinoma of the ovary, stomach, etc.

Figure 11.

Peritoneal carcinomatosis. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan in a known case of carcinoma ovary in a middle-aged woman shows peritoneal deposits (arrows) suggestive of peritoneal carcinomatosis

Carcinoid

Carcinoids are well-defined, homogenously enhancing bowel masses [Figure 12A and B] with desmoplastic reaction. They may cause bowel obstruction. Metastases from these tumors are hypervascular.

Figure 12 (A, B).

Carcinoid. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan (A) shows a duodenal mass with intraluminal and exophytic components (arrows) along with hypervascular metastasis (arrowhead). Sagittal contrast-enhanced CT scan (B) confirms an intraluminal mass (arrow) in the duodenum causing proximal obstruction

Other imaging and treatment issues

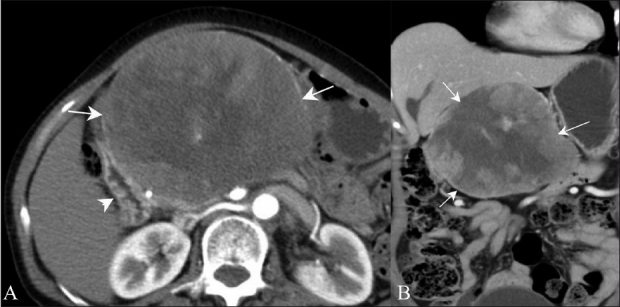

For localizing the organ of origin and defining the extent of the mass, 64–row multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with multiplanar reformations may be helpful. An exophytic nonfunctioning pancreatic neoplasm may sometimes be difficult to differentiate from GIST [Figure 13A] on the axial plane alone, and other imaging planes can be extremely helpful [Figure 13B].

Figure 13 (A, B).

Exophytic pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. Contrast-enhanced axial (A) and coronal (B) CT scans in a 60-year-old female show a well-defined, heterogeneously enhancing mass (arrows) along the second part of the duodenum (arrowhead)

Imatinib is a new chemotherapeutic agent used in the treatment of GIST. It is a molecularly targeted tyrosine kinase receptor blocker. Response to imatinib is usually good, with improved long-term survival.[26] The imaging features in patients showing response to imatinib include decrease in the density of the lesion, reduction in enhancement, and reduction in the number of nodules and number of vessels. The size of the lesion may increase or decrease.[26] King et al.[6] also demonstrated cystic degeneration and involution of hepatic metastases on treatment with imatinib.

Marginal increase in the size of the lesion on CT after imatinib therapy should not be mistaken for disease progression. The Choi criteria for assessing response, based on 10% decrease in size and 15% decrease in density of lesion, have been reported to correlate well with PET(positron emission tomography) /CT.[27]

PET imaging in patients undergoing therapy with imatinib may detect metabolic improvement before morphologic or structural change by demonstrating changes in glucose metabolism, which closely correlate with tumor response.[28] A short-term follow-up by CT scan can be done at 1 month if PET is not available. The metastatic deposits in GIST also show uptake of FDG.[13]

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our sincere thanks to Dr VRK Rao, Head of Department of Radio-diagnosis, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, for his constant guidance and support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Burkill GJ, Badran M, Al-Muderis O, Meirion Thomas J, Judson IR, Fisher C, et al. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Distribution, imaging features, and pattern of metastatic spread. Radiology. 2003;226:527–32. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2262011880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Definition, clinical, histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic features and differential diagnosis. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s004280000338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludwig DJ, Traverso LW. Gut stromal tumors and their clinical behavior. Am J Surg. 1997;173:390–4. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miettinen M, Monihan JM, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Carr NJ, Emory TS, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary to the omentum and mesentery. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1109–18. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199909000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459–65. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.King M. The radiology of gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) Cancer Imaging. 2005;5:150–6. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2005.0109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Sobin LH, Lasota J. Esophageal stromal tumors: A clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 17 cases and comparison with esophageal leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:211–22. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200002000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dematteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal tumors: Recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludwig DJ, Traverso LW. Gut stromal tumors and their clinical behavior. Am J Surg. 1997;173:390–4. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)00064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miettinen M, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors in the appendix: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of four cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:1433–7. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200111000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Akwari OE, Dozois RR, Weiland LH, Beahrs OH. Leiomyosarcoma of the small and large bowel. Cancer. 1978;42:1375–84. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197809)42:3<1375::aid-cncr2820420348>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skandalakis JE, Gray SW. Progress in Clinical Cancer. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1965. Smooth muscle tumors of the alimentary tract; pp. 692–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hersh MR, Choi J, Garsett C, Clark R. Imaging Gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Cancer Control. 2005;12:111–5. doi: 10.1177/107327480501200206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee CM, Chen HC, Leung TK, Chen YY. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Computed tomographic features. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2417–8. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i16.2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy AD, Remotti HE, Thompson WM, Sobin LH, Miettinen M. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Radiologic features with pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2003;23:283–304. doi: 10.1148/rg.232025146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miettinen M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: Review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1466–78. doi: 10.5858/2006-130-1466-GSTROM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fong Y, Coit DG, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Lymph node metastasis from soft tissue sarcoma in adults.Analysis of data from a prospective database of 1772 sarcoma patients. Ann Surg. 1993;217:72–7. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199301000-00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blay JY, Bonvalot S, Casali P, Choi H, Debiec-Richter M, Dei Tos AP, et al. Consensus meeting for the management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors.Report of the GIST Consensus Conference of 20-21 March 2004, under the auspices of ESMO. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:566–78. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ding G, Yang J, Cheng S, Kai L, Nan L, Zhang S, et al. A rare case of rapid growth of exophytic gastrointestinal stromal tumour of stomach. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:820–3. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-2646-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Naitoh I, Okayama Y, Hirai M, Kitajima Y, Hayashi K, Okamoto T, et al. Exophytic pedunculated gastrointestinal stromal tumor with remarkable cystic change. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1181–4. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ulusan S, Koc Z, Kayaselcuk F. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours: CT findings. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:618–23. doi: 10.1259/bjr/90134736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu TY, Wong CS. Bone metastases from Gastrointestinal stromal tumour: Correlation with positron emission tomography- Computed tomography. J HK Coll Radiol. 2009;11:172–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carney JA. Gastric stromal sarcoma, pulmonary chondroma,and extra-adrenal paraganglioma (Carney triad): Natural history, adrenocortical component and possible familial occurrence. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:543–52. doi: 10.4065/74.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grieco A, Cavallaro A, Potenza AE, Mulè A, Tarquini E, Miele L, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) and ulcerative colitis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2002;21:617–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nilsson B, Bümming P, Meis-Kindblom JM, Odén A, Dortok A, Gustavsson B, et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: The incidence, prevalence, clinical course, and prognostication in the preimatinib mesylate era: A population-based study in western Sweden. Cancer. 2005;103:821–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong X, Choi H, Loyer EM, Benjamin RS, Trent JC, Charnsangavej C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: Role of CT in diagnosis and in response evaluation and surveillance after treatment with imatinib. Radiographics. 2006;26:481–95. doi: 10.1148/rg.262055097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benjamin RS, Choi H, Macapinlac HA, Burgess MA, Patel SR, Chen LL, et al. We should desist using RECIST, at least in GIST. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1760–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goerres GW, Stupp R, Barghouth G. The value of PET, CT and in-line PET/ CT in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumours: Long term outcome of treatment with imatinib mesylate. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2005;32:153–62. doi: 10.1007/s00259-004-1633-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]