Abstract

In the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, the synthesis of the major and essential membrane phospholipid, phosphatidylcholine, occurs via the CDP-choline and the serine decarboxylase phosphoethanolamine methylation (SDPM) pathways, which are fueled by host choline, serine, and fatty acids. Both pathways share the final two steps catalyzed by two essential enzymes, P. falciparum CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (PfCCT) and choline-phosphate transferase (PfCEPT). We identified a novel class of phospholipid mimetics, which inhibit the growth of P. falciparum as well as Leishmania and Trypanosoma species. Metabolic analyses showed that one of these compounds, PG12, specifically blocks phosphatidylcholine biosynthesis from both the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways via inhibition of PfCCT. In vitro studies using recombinant PfCCT showed a dose-dependent inhibition of the enzyme by PG12. The potent antimalarial of this compound, its low cytotoxicity profile, and its established mode of action make it an excellent lead to advance for further drug development and efficacy in vivo.

Keywords: Infectious Diseases, Malaria, Parasite Metabolism, Phosphatidylcholine, Phospholipid

Introduction

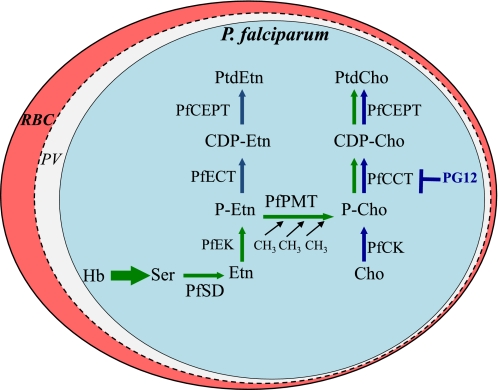

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease caused by Plasmodium parasites responsible for over 200 million clinical cases and approximately 800,000 deaths annually (1). This burden is due mainly to the absence of an effective malaria vaccine and the spread of parasites resistant to virtually all available antimalarial drugs. The dramatic increase of lipid synthesis in Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes to meet the high demand for new membranes as the parasite develops and multiplies has highlighted lipid metabolism as an excellent target for the development of new antimalarial drugs. Several compounds that target various steps in lipid biogenesis have been reported and include quaternary ammonium compounds, alkylphospholipid analogs, and fatty acid biosynthesis inhibitors (2–4). The major phospholipid in Plasmodium falciparum membranes is phosphatidylcholine (PtdCho),3 representing 40–50% of total phospholipids (5). PtdCho is synthesized from either choline (CDP-choline pathway) (6) or serine (serine decarboxylation-phosphoethanolamine methylation (SDPM) pathway) (2). The three-step methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine (PtdEtn) into PtdCho, predominant in most eukaryotes, does not occur in Plasmodium species (Fig. 1). The CDP-choline pathway synthesizes PtdCho from choline that is scavenged from the host (7). Once transported inside the parasite, choline is phosphorylated to form phosphocholine, which is converted to CDP-choline by the CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase (PfCCT). The synthesis of CDP-choline by PfCCT is the rate-limiting step of the CDP-choline pathway in Plasmodium. CDP-choline is subsequently transformed into PtdCho by a parasite choline-phosphate transferase (PfCEPT) (8, 9). The SDPM pathway uses host serine as a precursor for the synthesis of PtdCho. Serine may be obtained from degradation of host proteins or transported from the host (2, 10) (Fig. 1). The SDPM pathway involves five enzymes, two of which (serine decarboxylase (PfSD) and phosphoethanolamine methyltransferase (PfPMT)) are absent in mammals (11). PfPMT catalyzes the three-step S-adenosylmethionine methylation of phosphoethanolamine to form phosphocholine, which is used as a substrate by PfCCT and subsequently by PfCEPT to form PtdCho (2, 12). The transmethylation of phosphoethanolamine to form phosphocholine also exists in plants, worms, and other protozoa but not in mammals (11, 13–16). Recent genetic studies have shown that parasites lacking a functional SDPM pathway are severely altered in their development, produce half the number of nuclei and daughter parasites compared with wild-type P. falciparum, and show increased cell death (17). These findings suggest that the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways are not redundant. In addition to the synthesis of PtdCho by the parasite, biochemical analyses and genomic data suggest that PtdCho turnover and the transport of host phospholipids may also play an important role in parasite membrane biogenesis as well as development and survival within human erythrocytes. A parasite-specific phospholipase C (sphingomyelin/monoradylglycerophosphocholine-phospholipase C; PfNSM) has been shown to be expressed by P. falciparum during its intraerythrocytic life cycle, and its inhibition by scyphostatin results in parasite death (18), suggesting that PfNSM plays an essential role in parasite development. Here we describe the identification of a new class of phospholipid mimetics that inhibit the growth of P. falciparum as well as other protozoan parasites. Biochemical and genetic analyses aimed at characterizing the mechanism of action of one of these compounds, PG12, revealed that it exerts its antimalarial activity by inhibiting the essential step in the biosynthesis of PtdCho from both the SDPM and CDP-choline pathways catalyzed by PfCCT.

FIGURE 1.

Phospholipids biosynthesis pathways in P. falciparum and model of inhibition by PG12. The pathways of synthesis of PtdCho in P. falciparum from serine (SDPM pathway in green) and choline (CDP-choline in red) and PtdEtn from ethanolamine (CDP-ethanolamine pathway) are represented. Cho, choline; P-Cho, phosphocholine; HB, hemoglobin; Etn, ethanolamine; CDP-Cho, CDP-choline; PfSD, serine decarboxylase; PfEK, ethanolamine kinase; PfCK, choline kinase; PfPMT, phosphoethanolamine methyltransferase; PfCEPT, choline-phosphate transferase; PfCCT, CTP:phosphocholine cytidylyltransferase; PfECT, CTP:phosphoethanolamine cytidylyltransferase; RBC, red blood cell; PV, parasitophorous vacuole.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains, Growth Conditions, and Media

P. falciparum strain 3D7 was maintained in culture using standard growth conditions (19). The parasitemia was monitored by Giemsa staining. The culture medium contained RPMI 1640, sodium pyruvate (110 mg/liter), hypoxanthine (50 mg/liter), HEPES (7.13 g/liter), sodium bicarbonate (2.52 g/liter), glucose (2 g/liter), thymidine (2.5 mg/liter), gentamicin (10 mg/liter), and Albumax I (0.5%; Invitrogen). For labeling assays, parasites were grown in RPMI medium lacking choline, inositol, and serine. All media were sterilized by filtration.

Growth Inhibition Assays

Preliminary screening against Plasmodium, Trypanosoma, and Leishmania species and cytotoxicity studies were performed in collaboration with the World Health Organization at the Swiss Tropical Institute as described earlier (20–23). For antimalarial activity against the P. falciparum 3D7 strain, a hypoxanthine incorporation assay was performed. Parasites were synchronized at the ring stage with 5% (w/v) d-sorbitol, washed three times in medium lacking hypoxanthine, resuspended in medium with a low concentration of hypoxanthine (200 nm), and diluted to 1% parasitemia in this medium. A 24-well plate was loaded with 990 μl of infected culture in hypoxanthine-free medium, and 10 μl of the compounds (Table 1) was added at different concentrations. The plate was incubated at 37 °C for 48 h. After 2 days, 200 μl of culture was transferred in triplicate to a 96-well plate, and 25 μl of [3H]hypoxanthine in hypoxanthine-free medium (0.5 μCi/well) was added. The plate was incubated for 16 h at 37 °C. The following day, the cells were harvested, and the radioactivity within parasites was counted. The data were used to determine the percentage of inhibition of P. falciparum and to calculate IC50 values.

TABLE 1.

Structure of the phospholipid mimetics used in the study

Determination of PG12 Stage Specificity of Inhibition

A highly synchronized P. falciparum 3D7 culture at the ring stage was diluted to 2% parasitemia. A 24-well plate was loaded with 990 μl of this culture. PG12 was added at a concentration of 1 μm at different time intervals for 48 h after merozoite invasion, and the drug was changed every 8 h. In each well, the growth of the parasites was monitored by collecting samples every 8 h and performing Giemsa staining.

PLC Activity in P. falciparum Cell Extracts

Cell extracts were prepared from a 150-ml culture of P. falciparum at 10% parasitemia. Parasitized red blood cells were washed in PBS and lysed using 0.15% saponin. Parasites were harvested by centrifugation at 1700 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. Parasites were washed three times in PBS and centrifuged at 1700 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet was suspended in 200 μl of PBS containing a mixture of protease inhibitors. The isolated parasites were lysed by sonication, and the lysate was resuspended in 1% Triton X-100 and maintained on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, the supernatant containing soluble proteins was collected, and protein concentration was determined. The effect of PG12 on P. falciparum endogenous PLC activity was determined by using the experimental procedure described by Hanada et al. (18) and measuring the hydrolysis of sphingomyelin.

Labeling Studies and Phospholipid Analysis in P. falciparum

Synchronous 3D7 parasites were grown to a parasitemia of 10% with a hematocrit of 2% in medium lacking choline and transferred to a 6-well plate for incubation with PG12 for 1 h at 37 °C. Following treatment with PG12, parasites were labeled with 30 μm [methyl-14C]choline (55 mCi/mmol) or 2 μm [1,2-14C]ethanolamine (55 mCi/mmol) for 3 h. Parasites were then collected by centrifugation and washed once in choline-free medium and once in 0.15% saponin-PBS. Lipids and their soluble metabolites were extracted using a mixture of CHCl3/MeOH/H2O (2:1:0.75) (24). The organic and aqueous phases were evaporated and resuspended in 40 μl of CHCl3/MeOH (9:1, v/v) or 30 μl of MeOH/H2O (1:1), respectively. Organic phase samples were spotted on precoated silica gel plates and eluted with CHCl3, MeOH, acetic acid, 0.1 m sodium borate (75:45:12:3, v/v/v/v). The aqueous phase samples were also spotted on silica plates and eluted with MeOH, 0.5% NaCl, NH4OH (50:50:5, v/v/v). Phospholipids and their metabolites were identified with appropriate standards and detected by autoradiography.

Uptake of Radiolabeled Choline

P. falciparum 3D7 parasites were synchronized and grown to a parasitemia of 10% (2 × 107 infected red blood cells/ml). Trophozoite-infected erythrocytes were washed twice in RPMI and resuspended in the same medium. Transport was initiated by the addition of 1 μm [methyl-14C]choline (0.055 μCi/ml) (7). Transport was stopped by rapid centrifugation as described earlier (25), and radioactivity in the supernatant and the cells was determined by scintillation counting.

Expression of Recombinant PfCCTw

The primary sequence of the full-length PfCCT (896 amino acids) was identified from PlasmoDB (MAL13P1.86) and codon-optimized for expression in E. coli (GenScript). PfCCTw(528–795) was cloned into pET-15b expression vector, and recombinant protein was expressed in BL21(DE3) E. coli as a His6-tagged fusion and purified in a two-step purification using Ni2+-NTA affinity and gel filtration chromatography. Purified proteins were recovered at a final concentration of ∼0.2 mg/ml.

Activity Assays

Recombinant PfCCTw was incubated with phospho-[methyl-14C]choline (specific activity of 55 μCi/μmol (ISOBIO)). The enzymatic activity was measured by monitoring the formation of radiolabeled CDP-choline. Enzymatic reactions were performed in a 50-μl sample volume containing 100 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, buffer, 10 mm CTP, 0.5 mm phosphocholine (0.1 μCi of radiolabeled phosphocholine), 20 mm MgCl2. PG12 inhibitor concentrations ranged between 5 and 100 μm. Reactions were initiated with the addition of 0.5 μg of CCT followed by a 10-min incubation at 37 °C and stopped by heating at 96 °C for 5 min. For each assay, a sample of 20 μl was spotted onto a thin layer chromatography (TLC) silica gel plate (Merck), previously activated by heating at 100 °C for 1 h. Radiolabeled products and substrates were then separated in ethanol, 0.5% NaCl, 30% ammonia (50:50:1, v/v/v) and analyzed using a PhosphorImager (Storm 840; Amersham Biosciences). Spots corresponding to CDP-choline were excised from the plates and counted. Inhibitor dependence curves were fit using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad software, Inc.).

RESULTS

PG12 Inhibits P. falciparum Development and Prevents Parasite Intraerythrocytic Maturation and Multiplication

Previous work by Hanada et al. (18) indicated that scyphostatin, which specifically inhibits PfNSM activity, blocks parasite intraerythrocytic proliferation with an ID50 value of 7 μm. This finding led us to investigate the possible antiparasitic activity of several phospholipid analogs, originally designed as inhibitors of Bacillus cereus PLC enzyme, PLCBc (26, 27). In vitro screening of 14 of these compounds against a panel of parasites, including Leishmania donovani, Trypanosoma cruzi, Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense, and P. falciparum, showed growth-inhibitory activities with IC50 values in the micromolar to low nanomolar range (Table 2). Remarkably, 12 of the 14 compounds tested were more potent than scyphostatin, and nine of those compounds tested inhibited the growth of the chloroquine- and pyrimethamine-resistant P. falciparum K1 strain with IC50 values below 1 μm (Table 2). In vitro cytotoxicity assays identified PG12 as an excellent antimalarial candidate with a selectivity index of 500. This compound was therefore selected for further analysis.

TABLE 2.

Antiprotozoan and cytotoxicity activities of 14 phospholipid mimetics

| Compounds | P. falciparum IC50 | L. donovani IC50 | T. cruzi IC50 | T. brucei rhodesiense IC50 | Cytotox IC50 | SIa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | μm | μm | μm | μm | ||

| PG11 | 0.67 | 11.07 | 4.88 | 2.61 | 5.42 | 8.06 |

| PG12 | 0.42 | 6.10 | 36.50 | 3.40 | >139 | 515 |

| PG13 | 0.23 | 24.70 | 4.12 | 0.19 | 3.28 | 14.27 |

| PG14 | 0.98 | >77 | 5.92 | 0.44 | 11.64 | 11.89 |

| PG15 | 0.73 | 59.67 | 31.39 | 27.41 | 85.88 | 117.5 |

| PG17 | 0.40 | 44.68 | 24.51 | 1.87 | 13.57 | 33.89 |

| PG18 | 0.24 | 42.21 | 18.89 | 0.50 | 102.74 | 434 |

| PG19 | 9.06 | >90 | 55.19 | 5.42 | >270 | 29.80 |

| PG20 | 0.72 | 48.02 | >50 | 10.14 | 98.21 | 135.12 |

| PG21 | 2.54 | >69 | >69 | 8.48 | >206 | 81 |

| PG22 | >14 | >87 | >87 | 52.55 | >260 | |

| SG22 | 4.47 | 7.76 | 33.82 | 3.62 | 31.02 | 6.94 |

| AG84 | 0.54 | 13.75 | 12.14 | 1.14 | 6.69 | 12.43 |

| AG87 | 3.70 | 6.53 | 31.47 | 0.38 | 11.29 | 3.05 |

a Selectivity index, ratio of the IC50 value of a compound in mammalian cells and that in the chloroquine- and pyrimethamine-resistant P. falciparum K1 strain.

To determine whether PG12 targets a specific stage of parasite development, the compound was added to a highly synchronized P. falciparum (3D7 clone) culture following merozoite invasion, and the growth of the parasite was monitored every 8 h. The addition of PG12 at the early stage of parasite development (8 h postinvasion) had no effect on parasite progression from the ring to the trophozoite stage; the progression from the trophozoite to the mature schizont stage was completely blocked. No new nuclei or daughter parasites could be produced (Fig. 2). A similar effect of PG12 on parasite nuclear division and the ability to produce new daughter parasites was seen when the compound was added 16 or 24 h postinvasion but prior to the initiation of nuclear division (Fig. 2). Interestingly, the addition of PG12 at the schizont stage (32–40 h postinvasion), once nuclear division started, did not block merozoite release or erythrocyte reinvasion (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2.

PG12 inhibits P. falciparum development. Parasite intraerythrocytic development and multiplication were assessed in the absence or following the addition of PG12 (1 μm) after 8, 16, 24, 32, 40, or 48 h postmerozoite invasion. Samples collected were analyzed by light microscopy of Giemsa-stained smears.

PG12 Blocks the Biosynthesis of PtdCho and Only Partially Inhibits Parasite PLC Activity

Due to the known inhibitory activity of PG12 against PLCBc and the knowledge that PfNSM activity is essential in P. falciparum (27), this enzyme was regarded as a possible target of this compound. Therefore, the effect of PG12 on parasite endogenous PLC activity was examined by comparing the hydrolysis of radiolabeled sphingomyelin in the absence or presence of the compound. No inhibition of PLC activity could be detected at concentrations up to 10 μm. At 100 μm, PG12 reduced PLC activity by ∼50% (Fig. 3). These results suggest that, unlike in B. cereus, PLC activity is not the primary target of PG12 in P. falciparum.

FIGURE 3.

PG12 does not target PLC activity in P. falciparum. Inhibition of PfPLC was determined by measuring PfPLC hydrolysis of [14C]sphingomyelin in the presence of PG12. The substrate, enzyme, and inhibitor were incubated for 3 h, and the reaction was then quenched by the addition of CHCl3/MeOH (2:1, v/v). The aqueous soluble metabolites were separated by TLC, and PtdCho was identified using a standard and detected by autoradiography. Radioactive spots were scraped and counted in scintillation fluid. Error bars, S.D. of the mean values of three independent experiments.

The finding that PG12 blocks parasite proliferation at the peak of membrane biogenesis and prior to nuclear division and the structural similarity between PG12 and the phosphocholine analog, hexadecylphosphocholine, suggest that PG12 may act by inhibiting the biosynthesis of parasite major phospholipids PtdCho and PtdEtn. Metabolic labeling using [14C]choline and [14C]ethanolamine and subsequent TLC analyses showed that PtdCho biosynthesis from choline was reduced by more than 90% when PG12 was present at 10 μm and was almost completely inhibited when the compound was present at 25 μm (Fig. 4A). Similarly, the biosynthesis of PtdCho from ethanolamine via the SDPM pathway was reduced by ∼80 and ∼90% at concentrations of PG12 of 10 and 25 μm, respectively (Fig. 4B). Conversely, PtdEtn biosynthesis from ethanolamine was not significantly affected at 10 μm and was reduced only by ∼50% when the compound was added at 25 μm (Fig. 4C). Together, these results suggest that PG12 targets primarily the biosynthesis of PtdCho via the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways.

FIGURE 4.

PG12 inhibits the synthesis of PtdCho from choline and ethanolamine. Lipids were extracted from parasites grown in the absence or presence of PG12 and labeled with [14C]choline (A) and [14C]ethanolamine (B and C). The organic phase was separated by TLC, and PtdCho (A and B) and PtdEtn (C) were detected by autoradiography. Radioactive spots were then scraped and counted in scintillation fluid, and values were normalized to the untreated sample. Error bars, S.D. of three independent experiments. The amount of PtdCho (0.4 nmol/107 parasites) and PtdEtn (0.09 nmol/107 parasites) detected in the absence of the compound was set at 100%.

PG12 Blocks the Entry of Choline into Parasitized Red Blood Cells and Inhibits PfCCT Endogenous Activity

The inhibition of PtdCho biosynthesis by PG12 from both choline and ethanolamine suggests that the compound could act either by inhibiting different steps in the synthesis of PtdCho via the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways or by blocking one of the last two steps in the biosynthesis of PtdCho common to both pathways. The key initial steps of these two pathways are mediated by the choline transporter (PfCT) for the CDP-choline pathway and PfPMT for the SDPM pathway. The last steps are mediated by PfCCT and PfCEPT. To assess whether PG12 inhibits the uptake of choline, transport assays were performed in infected erythrocytes during the linear phase of transport in the absence or presence of PG12. As shown in Fig. 5, PG12 had no effect on the uptake of choline during the first 30 min of transport. However, after 60 min of incubation with the drug, choline uptake into Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes was reduced by 65% (Fig. 5). Despite this effect, choline concentrations up to 200 μm had no effect on the antimalarial activity of PG12 (data not shown), suggesting that the entry of the compound into the parasite does not involve the parasite primary choline transporter.

FIGURE 5.

PG12 impairs the uptake of [14C]choline. Transport of [methyl-14C]choline (1 μm) was measured in Plasmodium-infected erythrocytes in the absence (black bars) or presence (white bars) of PG12 (10 μm). The amount of radioactivity inside the parasite (transport and metabolism) was determined by liquid scintillation. Error bars, S.D.

The effect of PG12 on PfPMT, which catalyzes the limiting step in the SDPM pathway and is known to be inhibited by hexadecylphosphocholine (2, 28), was investigated by comparing the potency of the compound in culture against wild-type and transgenic parasites lacking the PfPMT gene. No differences in the inhibitory activity of PG12 in wild-type and transgenic P. falciparum parasites lacking or overexpressing PfPMT could be detected (data not shown). Together, these findings indicate that the initial steps of the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways might not be the primary targets of PG12.

To determine which of the last two steps in the biosynthesis of PtdCho from choline and ethanolamine was the target of PG12, the parasites were cultured in the presence of [14C]choline and [14C]ethanolamine in the absence or presence of the compound, and phospholipids and soluble metabolites were separated by thin layer chromatography and quantified. Whereas in the absence of PG12, 87.5% of labeled choline was found in the form of PtdCho and 11% as phosphocholine (8:1 ratio), treatment with 10 μm PG12 resulted in 39.5% of labeled choline incorporated into PtdCho and 49.5% incorporated into phosphocholine (∼1:1 ratio) (Fig. 6A). A higher concentration of PG12 resulted in a further decrease in the biosynthesis of PtdCho but a relatively similar PtdCho/phosphocholine ratio (∼1:1) (Fig. 6A). Similarly, metabolic analyses using radiolabeled ethanolamine showed 88% of radiolabeled ethanolamine incorporated into PtdCho and 12% into phosphocholine in the absence of the compound (Fig. 6B). Treatment with PG12 resulted in ∼3-fold accumulation of phosphocholine and a net decrease in the synthesis of PtdCho from ethanolamine (Fig. 6B). The major accumulation of phosphocholine and a concomitant decrease in the synthesis of PtdCho in parasites treated with PG12 suggest a direct effect of PG12 on PfCCT but not PfCEPT activities.

FIGURE 6.

Inhibition of phosphocholine (P-Cho) and PtdCho biosynthesis by PG12. Parasites were labeled with [14C]choline (A) and [14C]ethanolamine (B) in the absence or presence of PG12, and lipids and soluble precursors were separated. Phospholipids and soluble metabolites were detected by autoradiography. Labeled bands were scraped and counted in scintillation fluid, and values were normalized to the untreated sample. Error bars, S.D. of two independent experiments.

PG12 Inhibits PfCCT Activity in Vitro

In order to validate the direct inhibition of PfCCT activity, the effect of PG12 on recombinant PfCCT was measured. Because full-length PfCCT could not be expressed in a soluble form, a truncated version of the enzyme PfCCTw encompassing the C-terminal catalytic domain (residues 528–795) and lacking the membrane binding domain was generated. PfCCTw activity followed a Michaelis-Menten kinetic and was not lipid-dependent (not shown). PG12 inhibitory activity was tested at substrate concentrations corresponding to Km values (37).

As shown in Fig. 7, PG12 inhibits PfCCTw activity in a dose-dependent manner and within a very narrow concentration range. The IC50 value of the compound was ∼28 μm. At 50 μm, PG12 caused total inhibition of PfCCTw activity.

FIGURE 7.

Effect of PG12 on the activity of recombinant PfCCT. Experiments were carried out with purified recombinant protein PfCCTw. CCT activity was measured with increasing concentrations of PG12 compound. The activity is given in percentage of controls. Data points are means of duplicate observations. Results show a representative experiment of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

PtdCho and PtdEtn are the major phospholipids in the membranes of P. falciparum, representing 40–50 and 35–40% of the total phospholipids, respectively (29). Whereas lipid metabolism in non-infected erythrocytes is almost non-existent, infection of erythrocytes with P. falciparum results in a dramatic increase in lipid metabolism to meet the high demand for new membranes as the parasite rapidly develops and multiplies (30). Due to the essential role phospholipids play in parasite multiplication and pathogenesis, the biosynthesis of phospholipids has long been viewed as an excellent target for the development of novel antimalarial drugs. Several compounds have thus been identified that target various steps in lipid biogenesis and include quaternary and bisquaternary ammonium compounds, alkylphospholipid analogs, and fatty acid biosynthesis inhibitors (31).

The finding by Hanada et al. (18) that inhibition of the P. falciparum PfNSM by scyphostatin accounts for its antimalarial activity prompted us to study the antiparasitic activity of several compounds synthesized as inhibitors of PC-PLCBc. An initial screening conducted as part of the World Health Organization TDR program identified 12 compounds of the 14 compounds tested to have a significantly more potent antimalarial activity than scytostatin, with nine of the compounds inhibiting the in vitro growth of P. falciparum in the nanomolar range. One candidate compound, PG12, chosen for its excellent antimalarial activity and low cytotoxicity was selected for further characterization. Examination of the stage of development targeted by PG12 showed that it blocks parasite intraerythrocytic development and multiplication but has no effect on parasite rupture or reinvasion. Analysis of the effect of this compound on PLC activity showed that although PG12 is a specific inhibitor of mammalian PC-PLC enzymes, it has no effect on the P. falciparum endogenous PLC activity. Conversely, phospholipid analysis showed that PtdCho biosynthesis via both the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways was altered in the presence of the compound, whereas PtdEtn synthesis was only partially affected.

Previous studies in P. falciparum and Saccharomyces cerevisiae have shown that the antimalarial bisquaternary ammonium compound T16 inhibits PtdCho synthesis via inhibition of choline transport as well as other steps in phospholipid metabolism (32). This suggests that some phospholipid inhibitors could exert their antimalarial activity by inhibiting more than one pathway leading to the synthesis of the major parasite phospholipids. The specific inhibition of PtdCho synthesis from choline and ethanolamine by PG12 and the structural similarity between PG12 and hexadecylphosphocholine (miltefosine), a phospholipid analog known to inhibit PfPMT activity (2, 28), suggested that it could inhibit PtdCho by blocking the initial steps of both the SDPM and CDP-choline pathways. Indeed, PG12 inhibited the uptake of radiolabeled choline and, to a lesser extent, that of ethanolamine into the infected erythrocyte. However, the potency of this compound was not affected by choline supplementation up to 10-fold its physiological concentration, suggesting that PG12 inhibits choline transport but is not transported into the parasite via the parasite primary choline transporter. Our studies also showed that parasites lacking or overexpressing PfPMT were equally sensitive to PG12 as wild-type parasites. Together, these results demonstrate that the initial steps of the CDP-choline (choline transport and choline phosphorylation) and SDPM pathways are not the main targets of the compound. Consequently, this finding suggests that one of the last two steps of PtdCho biosynthesis common to the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways and encoded by the PfCCT and PfCEPT genes may be the main target of the compound. Our genetic studies have thus far failed to generate a knock-out of these genes, most likely due to their essential function during P. falciparum intraerythrocytic life cycle. Analysis of the phospholipid and soluble metabolites produced following labeling with [14C]choline and [14C]ethanolamine demonstrated a major accumulation of phosphocholine and a concomitant decrease in the synthesis of PtdCho in parasites treated with PG12 compared with untreated parasites. The finding that the antimalarial activity of PG12 was unaffected by exogenous choline and the finding that levels of intracellular choline were similar between untreated and PG12-treated parasites all indicate that the accumulation of phosphocholine in PG12-treated parasites is solely due to the inhibition of PfCCT and not to an increase in choline phosphorylation or to the inhibition of the PfCEPT enzyme.

The inhibition of PfCCT activity by PG12 was further validated using recombinant active PfCCTw enzyme. Due to the pattern of inhibition of PfCCTw by PG12, a reliable Ki value could not be determined. Although the IC50 value of PG12 against the parasite is in the nanomolar range, its intracellular concentration remains unknown. Previous studies with the phospholipid inhibitors of the quaternary and bisquaternary ammonium compound family have shown dramatic increases in the intracellular accumulation of these compounds, with the ratios between the intracellular and extracellular concentrations exceeding 1000 (4). A similar phenomenon has previously been reported for other antimalarials, such as chloroquine, in the digestive vacuole (33). Thus, if PG12 follows this same pattern, its intracellular concentration might be high enough to result in a complete inhibition of the parasite PfCCT activity and PtdCho synthesis, leading to parasite death. Consistent with the inhibition of PfCCT, studies in mammalian cells have shown that structural analogs of this class of phospholipid mimetics, such as hexadecylphosphocholine and edelfosine, also inhibit CCT activity (9, 34–36).

In summary, we identified a new and potent antimalarial compound, which blocks the synthesis of PtdCho from choline and ethanolamine. Our findings suggest a model (Fig. 1) for the mode of action of this class of antimalarials and possibly other lipid-based antimalarial inhibitors. We propose that PG12 specifically targets the activity of PfCCT and by doing so blocks the synthesis of PtdCho from both the CDP-choline and SDPM pathways. The structural novelty of this compound, the knowledge of its mechanism of action, and its effects on PfCCT, a previously undisclosed P. falciparum drug target of essential function during its intraerythrocytic life cycle, make PG12 an attractive candidate for antimalarial drug development.

Acknowledgments

We thank the World Health Organization, Dr. Foluke Fakorede, and Dr. Reto Brun for the preliminary screening of compounds under the WHO/TDR Training in Tropical Diseases program; A. G. Fernández and J. Casas for discussions; A. Gonzalez-Roura for early synthetic work; and S. Gonzalez and M. Lavigne for technical support.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NIAID, Grant AI51507 (to C. B. M.). This work was also supported by “Generalitat de Catalunya” Grant 2009SGR-1072 and “Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación,” Spain (Project CTQ2008-01426/BQU and a fellowship to P. G. B.), Department of Defense Grant PR033005 (to C. B. M.), and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to C. B. M.).

- PtdCho

- phosphatidylcholine

- PtdEtn

- phosphatidylethanolamine

- SDPM

- serine decarboxylase phosphoethanolamine methylation

- PLC

- phospholipase C.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization (2010) World Malaria Report, World Health Organization, Geneva [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pessi G., Kociubinski G., Mamoun C. B. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6206–6211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Surolia N., Surolia A. (2001) Nat. Med. 7, 167–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wengelnik K., Vidal V., Ancelin M. L., Cathiard A. M., Morgat J. L., Kocken C. H., Calas M., Herrera S., Thomas A. W., Vial H. J. (2002) Science 295, 1311–1314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vial H. J., Ben Mamoun C. (2005) in Molecular Approaches to Malaria (Sherman I. W. ed) pp. 327–352, American Society for Microbiology Press, Washington D. C [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kennedy E. P., Weiss S. B. (1956) J. Biol. Chem. 222, 193–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Biagini G. A., Pasini E. M., Hughes R., De Koning H. P., Vial H. J., O'Neill P. M., Ward S. A., Bray P. G. (2004) Blood 104, 3372–3377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ancelin M. L., Vial H. J. (1989) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1001, 82–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Boggs K. P., Rock C. O., Jackowski S. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 7757–7764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pessi G., Ben Mamoun C. (2006) Future Med. Future Lipidol. 1, 173–180 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bobenchik A. M., Augagneur Y., Hao B., Hoch J. C., Ben Mamoun C. (2011) FEMS Microbiol Rev. 35, 609–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pessi G., Choi J. Y., Reynolds J. M., Voelker D. R., Mamoun C. B. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 12461–12466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bolognese C. P., McGraw P. (2000) Plant Physiol. 124, 1800–1813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brendza K. M., Haakenson W., Cahoon R. E., Hicks L. M., Palavalli L. H., Chiapelli B. J., McLaird M., McCarter J. P., Williams D. J., Hresko M. C., Jez J. M. (2007) Biochem. J. 404, 439–448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Charron J. B., Breton G., Danyluk J., Muzac I., Ibrahim R. K., Sarhan F. (2002) Plant Physiol. 129, 363–373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Palavalli L. H., Brendza K. M., Haakenson W., Cahoon R. E., McLaird M., Hicks L. M., McCarter J. P., Williams D. J., Hresko M. C., Jez J. M. (2006) Biochemistry 45, 6056–6065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Witola W. H., El Bissati K., Pessi G., Xie C., Roepe P. D., Mamoun C. B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27636–27643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hanada K., Palacpac N. M., Magistrado P. A., Kurokawa K., Rai G., Sakata D., Hara T., Horii T., Nishijima M., Mitamura T. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 195, 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Trager W., Jensen J. B. (1976) Science 193, 673–675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Baltz T., Baltz D., Giroud C., Crockett J. (1985) EMBO J. 4, 1273–1277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dua V. K., Verma G., Agarwal D. D., Kaiser M., Brun R. (2011) J. Ethnopharmacol. 136, 123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Matile H., Pink J. R. L. (1990) Plasmodium falciparum Malaria Parasite Cultures and Their Use in Immunology, Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 23. Räz B., Iten M., Grether-Bühler Y., Kaminsky R., Brun R. (1997) Acta Trop. 68, 139–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Folch J., Lees M., Sloane Stanley G. H. (1957) J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. El Bissati K., Downie M. J., Kim S. K., Horowitz M., Carter N., Ullman B., Ben Mamoun C. (2008) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 161, 130–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. González-Bulnes P., González-Roura A., Canals D., Delgado A., Casas J., Llebaria A. (2010) Bioorg Med. Chem. 18, 8549–8555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanada K., Mitamura T., Fukasawa M., Magistrado P. A., Horii T., Nishijima M. (2000) Biochem. J. 346, 671–677 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bobenchik A. M., Choi J. Y., Mishra A., Rujan I. N., Hao B., Voelker D. R., Hoch J. C., Mamoun C. B. (2010) BMC Biochem. 11, 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsiao L. L., Howard R. J., Aikawa M., Taraschi T. F. (1991) Biochem. J. 274, 121–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sherman I. W. (1979) Microbiol. Rev. 43, 453–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ben Mamoun C., Prigge S. T., Vial H. (2010) Drug Dev. Res. 71, 44–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Richier E., Biagini G. A., Wein S., Boudou F., Bray P. G., Ward S. A., Precigout E., Calas M., Dubremetz J. F., Vial H. J. (2006) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 3381–3388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sullivan D. J., Jr., Gluzman I. Y., Russell D. G., Goldberg D. E. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 11865–11870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Baburina I., Jackowski S. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 2169–2173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Boggs K., Rock C. O., Jackowski S. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1389, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vogler W. R., Shoji M., Hayzer D. J., Xie Y. P., Renshaw M. (1996) Leuk. Res. 20, 947–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yeo H. J., Larvor M. P., Ancelin M. L., Vial H. J. (1997) Biochem. J. 324, 903–910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]