Abstract

Spt6 is a highly conserved transcription elongation factor and histone chaperone. It binds directly to the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain (RNAPII CTD) through its C-terminal region that recognizes RNAPII CTD phosphorylation. In this study, we determined the solution structure of the C-terminal region of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Spt6, and we discovered that Spt6 has two SH2 domains in tandem. Structural and phylogenetic analysis revealed that the second SH2 domain was evolutionarily distant from canonical SH2 domains and represented a novel SH2 subfamily with a novel binding site for phosphoserine. In addition, NMR chemical shift perturbation experiments demonstrated that the tandem SH2 domains recognized Tyr1, Ser2, Ser5, and Ser7 phosphorylation of RNAPII CTD with millimolar binding affinities. The structural basis for the binding of the tandem SH2 domains to different forms of phosphorylated RNAPII CTD and its physiological relevance are discussed. Our results also suggest that Spt6 may use the tandem SH2 domain module to sense the phosphorylation level of RNAPII CTD.

Keywords: NMR, Protein Phosphorylation, Protein Structure, RNA Polymerase II, SH2 Domains, Chemical Shift Perturbation, Spt6

Introduction

Eukaryotic mRNA transcription is regulated through the interaction between RNA polymerase II and various factors. The largest subunit (Rpb1) of RNAPII has a C-terminal domain (CTD)3 that comprises dozens of copies of the consensus heptad-peptide sequence 1YSPTSPS7, which can be phosphorylated at Tyr1, Ser2, Ser5, and Ser7 (1–5). During the process of gene transcription, phosphorylation of RNAPII CTD occurs on sites Ser5, Ser7, and Ser2 (5). Specifically, both Ser5 and Ser7 are phosphorylated by the basal transcription factor TFIIH (Transcription factor II H) at the promoter-proximal region, whereas Ser2 is phosphorylated by the kinase complex pTEFb·CDK9 at the gene-coding region (6, 7). Various combinations of phosphorylation and cis-trans isomerization of prolines constitute the so-called “CTD code” (8, 9), which serves as a recognition marker for diverse regulatory factors that are involved in transcription initiation, elongation, termination, mRNA processing, and mRNA transport (7, 10).

Spt6 is an elongation factor and histone H3·H4 chaperone, which interacts with the nucleosome and RNAPII in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (11, 12). Spt6 activates transcription elongation of many genes in vivo (11, 13–15), regulates histone H3 lysine 36 methylation, and participates in mRNA 3′-end processing and export (16–18). Many research reports have indicated that Spt6 cooperates with another histone H2A·H2B chaperone named FACT (FAcilitates Chromatin Transcription) in the reassembly of chromatin in the wake of transcribing RNAPII (12, 19–21). In addition, functional loss of Spt6 results in an aberrant short transcript, which begins from the cryptic promoter in the coding region of genes (15). A previous study reported that murine Spt6 associated with hyperphosphorylated RNAPII in cell extracts through its C-terminal region (residues 1476–1726), where an SH2 domain preferentially recognized Ser2 phosphorylation of RNAPII CTD (18). A point mutation of the phosphate-binding arginine (Arg1528) to lysine in this SH2 domain impaired the binding ability of Spt6 to RNAPII. Cells that contain this R1528K mutant produced transcripts with splicing defects and had malfunctions in mRNA export (18).

Previous studies have shown that Spt6 contains the first SH2 domain reported to recognize the phosphoserine of RNAPII CTD rather than phosphotyrosine, which is the preferential partner of canonical SH2 domains (18). Therefore, the structural investigation of this unusual SH2 domain should increase our understanding of the interaction of this SH2 domain with RNAPII CTD. Recently, three groups reported the crystal structures of two tandem SH2 domains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Candida glabrata, and Antonospora locustae Spt6 (22–24). They found that the tandem SH2 domains directly bound to Ser2-phosphorylated RNAPII CTD, and both SH2 domains were essential for Spt6 function in vivo. In all three of the structures, the first SH2 domain (designated “SH2N” hereafter) had a canonical pocket for phosphate recognition. However, due to the lack of a complex structure with RNAPII CTD, two of the groups had different hypotheses about the binding site in the second SH2 domain (designated “SH2C”). To solve this discrepancy, we employed the solution NMR approach to characterize the interaction between these tandem SH2 domains (designated “SH2NC”) and RNAPII CTD at the atomic level.

Here, we report the solution structure of the C-terminal region (residues 1250–1440) of S. cerevisiae Spt6. The structure reveals that this fragment consist of two tandem SH2 domains, which are packed in a head-to-tail manner through a conserved interdomain hydrophobic core. Using NMR chemical shift perturbation experiments, we have determined the binding affinities and interaction surface of the tandem SH2 domains with RNAPII CTD peptides phosphorylated at one or more residues (Tyr1, Ser2, Ser5, or Ser7). Data show that the SH2N domain binds to phosphoserine or phosphotyrosine with the same canonical phosphate binding pocket, which is missing in the SH2C domain. However, the SH2C domain still weakly binds to phosphoserine via a conserved noncanonical binding site and enhances the association between SH2N and RNAPII CTD. Surprisingly, we found that the tandem SH2 domains also bound to Ser7- or Tyr1-phosphorylated RNAPII CTD, which were reported to be involved in snRNA expression or transcription-coupled DNA repair, respectively (1, 25, 26). Our data suggest that the SH2NC module of Spt6 can sense the phosphorylation level of RNAPII CTD because the weak binding between the SH2NC module and RNAPII CTD can be additively enhanced by simultaneous phosphorylation of the same or different repeat units of RNAPII CTD.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Preparation

Two fragments (SH2NC, residues 1250–1440; SH2N, residues 1250–1304) of S. cerevisiae Spt6 were cloned into the NdeI/XhoI sites of plasmid pET22b(+) (Novagen) to produce proteins with a His6 tag fused at the C terminus. A PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis approach was used to generate the SH2NC-MT mutant, in which four residues were substituted with alanines or phenylalanine (R1282A, S1283A, Y1381F, and K1435A), Generally, the protein expression in Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) was induced at A600 = 0.8–1.5 with 0.1 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside at 16 °C for 24 h. 15N- or 13C/15N-labeled proteins were produced in M9 medium supplemented with 15NH4Cl or both 15NH4Cl and [13C]glucose. A 2H/13C/15N triple-labeled SH2NC sample was produced in the same medium but containing 95% 2H2O. The resulting proteins were firstly extracted with Ni2+ affinity resin and then further purified using size-exclusion chromatography on a HiLoad Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare). The purified proteins were dialyzed into NMR buffers (for SH2NC, 150 mm NaCl, 25 mm H2KPO4-HK2PO4, pH 5.5, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA; for SH2N, 150 mm NaCl, 25 mm H2KPO4-HK2PO4 pH 7.0, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA) and concentrated to ∼0.5 mm.

NMR Experiments and Structure Calculation

All of the spectra for the structure determination or resonance assignment were recorded at 310 K (for SH2NC) or 298 K (for SH2N) on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic probe (Bruker BioSpin). Each NMR sample was prepared in NMR buffer with 10% (v/v) 2H2O. Heteronuclear spectra HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, HNCO, HN(CA)CO, CC(CO)NH-TOCSY, HCC(CO)NH-TOCSY, HCCH-TOCSY, HCCH-COSY, 15N-edited three-dimensional NOESY, 13C-edited three-dimensional NOESY were collected with a 13C/15N-labeled sample. For backbone assignments of SH2NC, we also recorded HNCACB, HN(CO)CACB, HNCA, HN(CO)CA, HNCO, HN(CA)CO with a 2H/13C/15N triple-labeled protein.

RDC data for SH2NC were collected in 2.8% (w/v) 1,2-Dimyristoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine:1,2-Dihexanoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphocholine bicelle medium prepared according to a previously reported protocol (27). IPAP-HSQC spectra (28) were recorded at 311 K on a Bruker 600 MHz spectrometer. Backbone 15N relaxation experiments were carried out at 310 K on a Bruker 500 MHz NMR spectrometer using published methods (29). All NMR data were processed with the NMRPipe package and assigned with Sparky software (30, 31).

Structure calculations were performed using Xplor-NIH2.24 (32) with 3170 NOEs, 296 dihedral angles, 93 hydrogen bonds, and 95 backbone 1H-15N RDC restraints. A standard script (xplor-nih-2.24/eginput/protG/anneal.py) was modified to anneal the structures from extended conformation.

Chemical Shift Perturbation Experiments

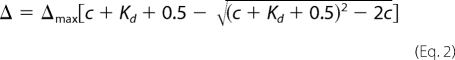

Both synthetic peptides (SciLight-Peptide Biotechnology LLC, Beijing, China) and 15N-labeled proteins were prepared in the same buffer: 10 mm Bis-Tris, pH 7.0, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, 10% (v/v) 2H2O, and adjusted to pH 7.0 if needed. A series of 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded at 310 K as the peptides were titrated into the 500-μl 0.5 mm protein solution. The total volume of added peptide solution did not exceed 50 μl to ensure that there was no significant dilution of the protein. The combined chemical shift change Δ is calculated using Equation 1,

|

where Δ1H and Δ15N are chemical shift changes in the 1H and 15N dimensions, respectively. The dissociation constant Kd is deduced by fitting the combined chemical shift change to the function below (Equation 2),

|

where Δmax denotes the maximal change in chemical shift when the protein is saturated by the peptide, and c is the total concentration of peptide in solution.

Phylogenetic Analysis

We searched the PDB database with the structure of yeast Spt6 SH2C (residues 1359–1440) on the DALI server (33). Structures with a Z-score of >5.0 were aligned with SH2C. The secondary structure region was aligned according to the three-dimensional comparison, whereas the loop region was aligned using the ClustalW program (34). With the established sequence alignment (see supplemental data set 1), a neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was built in the MEGA4 program (35).

RESULTS

Spt6 Has Two SH2 Domains in Tandem

It is reported that RNAPII can be pulled down by a C-terminal fragment (residues 1162–1496) of murine Spt6 (18), which encompasses an SH2 domain (residues 1250–1355) and an additional C-terminal region. The predicted secondary structure (data not shown) of this additional region from different species exhibited a pattern very similar to that of the upstream SH2 domain (namely SH2N), indicating that this region (namely SH2C) is evolutionarily conserved and might also be involved in the interaction between Spt6 and RNAPII.

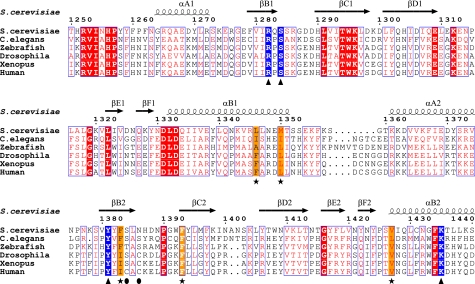

Sequence analysis indicated that the SH2C domain shares little sequence similarity with canonical SH2 domains and is present only in Spt6. The SH2C domains of the Spt6 proteins were not detected by several important databases, including Uniprot, SMART, and Pfam. Further BLAST searches using SH2C as a query in the Uniprot database did not identify any SH2 domains from any other protein except for the Spt6 homologues. A sequence alignment showed that the SH2C domain is less conserved than the SH2N domain across different species (see Fig. 2). For instance, between yeast and human, the SH2C domains have only 7.3% sequence identity, compared with 16.5% for the SH2N domains.

FIGURE 2.

Sequence alignment of the Spt6 tandem SH2 domains from different species: S. cerevisiae (P23615), C. elegans (P34703), Drosophila (B6IDH0), zebrafish (Q8UVK2), Xenopus (Q08D33), and human (Q7KZ85). The Uniprot accession codes are given in parentheses. The residues involved in electrostatic interactions with phosphorylated RNAPII CTD are colored in blue and marked (▴). Five type-conserved residues forming the interdomain hydrophobic core are indicated with * and colored in yellow. ●, two residues in the SH2C domain, which correspond to Arg175/Ser177 of Src SH2. The sequence alignment was produced with ClustalW (34) and colored with the ESPript server (47).

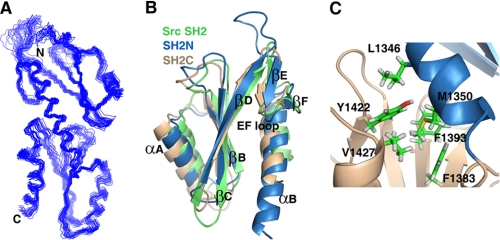

We determined the solution structure of the tandem SH2 domains (residues 1250–1440) of S. cerevisiae Spt6 using heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Structures were calculated with experimental restraints such as NOE, predicted dihedral angles, backbone amide 1H-15N RDC data, and hydrogen bond information from a hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiment (Table 1). Fig. 1A shows 20 energy-minimized structures of the tandem SH2 module. The backbone root mean square deviation is 0.63 Å for the well restrained region (residues 1259–1283, 1291–1310, and 1321–1438). The overall architecture of the structure clearly displays two SH2 domains arranged in a head-to-tail manner. Both domains adopt the canonical SH2 fold, which consists of three anti-parallel β strands (βB, βC, and βD) that are sandwiched by two α helices (αΑ and αΒ) at the N and C termini (Fig. 1B). Two additional short anti-parallel β strands (βΕ and βF) are inserted between the βD strand and αΒ helix (Fig. 1B). Although the sequence similarity between the SH2N and SH2C domains is very low (13.3% identity), their backbone Cα atoms can be superimposed well with a 1.1 Å root mean square deviation for the secondary structure region (Fig. 1B).

TABLE 1.

Statistics for the solution structure ensemble of the yeast Spt6 tandem SH2 domains

| Experimental restraints | |

| NOE distance restraints | 3170 |

| Intraresidue | 852 |

| Short range (i − j = 1) | 905 |

| Medium range (2 ≤ i − j ≤ 4) | 656 |

| Long range (i − j ≥ 5) | 757 |

| TALOS dihedral angle constraints | 296 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 93 |

| Backbone 1H-15N RDC | 95 |

| X-PLOR energies (kcal mol−1) | |

| Etotal | −1430.7 ± 28.5 |

| Ebond | 35.7 ± 3.9 |

| Eangle | 227.5 ± 5.0 |

| Eimproper | 45.3 ± 3.0 |

| Evdw | 168.1 ± 12.8 |

| Enoe | 93.1 ± 19.1 |

| Ecdih | 20.4 ± 2.8 |

| Experimental restraints violation analysis | |

| NOE > 0.5 Å | 0 |

| Dihedral angle > 5° | 0 |

| RDC > 2.0 Hz | 0 |

| Ramachandran plot analysis (%) | |

| Residues in most favored regions | 88.2 |

| Residues in additional allowed regions | 10.1 |

| Residues in generously allowed regions | 0.9 |

| Residues in disallowed regions | 0.8 |

| r.m.s.d. from mean structure (Å)a | |

| Backbone (N, Ca, CO) atoms | 0.63 |

| All non-hydrogen atoms | 1.11 |

a Root mean square deviation (r.m.s.d.) is calculated for the well restrained region, including residues 1259–1283, 1291–1310, and 1321–1438.

FIGURE 1.

Solution structure of the tandem SH2 domains of S. cerevisiae Spt6. A, backbone superimposition of 20 energy-minimized structures. B, structural comparison between Src SH2 (green, PDB code 1SPS) and the SH2N (blue) and SH2C (beige) domains of Spt6. The three-dimensional structure alignment was carried out using the DALI server (33). C, an interdomain hydrophobic core consisting of residue Leu1346, Met1350, Phe1383, Phe1393, Tyr1422, and Val1427.

Two SH2 Domains Intimately Associate with Each Other

The tandem SH2 domains are closely packed against each other through hydrophobic residues and are connected by a short linker (residues 1553–1558). Notably, compared with the SH2C domain, the SH2N domain has a longer αΒ1 helix, which makes extensive contacts with the SH2C domain. Indeed, some long range NOEs were identified between residues in the αΒ1 helix of SH2N (Leu1346, Met1350) and the SH2C domain (Phe1383, Phe1393, Tyr1422, and Val1427). These residues form an interdomain hydrophobic core (Fig. 1C). A sequence alignment further shows that except for Tyr1422, the residues are all type conserved among the Spt6 homologues (Fig. 2), suggesting the importance of this interdomain hydrophobic core in the evolution of this tandem SH2 domain module.

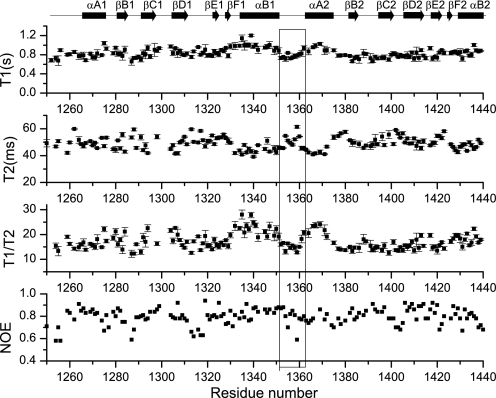

NMR dynamic and RDC data support the formation of the tandem SH2 domains into a rigid module. We measured the longitudinal (transversal) relaxation time T1 (T2), and the 1H-15N NOE data of the backbone amides (Fig. 3). These dynamic data revealed that the two SH2 domains have similar dynamic properties in solution, and the interdomain linker is as rigid as the secondary structure region. In addition, only one common alignment tensor is needed to back-calculate the measured RDC data for both domains, and these RDC values fit well with the measured ones (see supplemental Fig. S1). These results revealed that the two SH2 domains tumble as a whole in solution and have a fixed relative orientation (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 3.

The NMR dynamic data for the tandem SH2 domains in solution. The backbone amide longitudinal/transversal relaxation time T1, T2, and 1H-15N NOE values are shown.

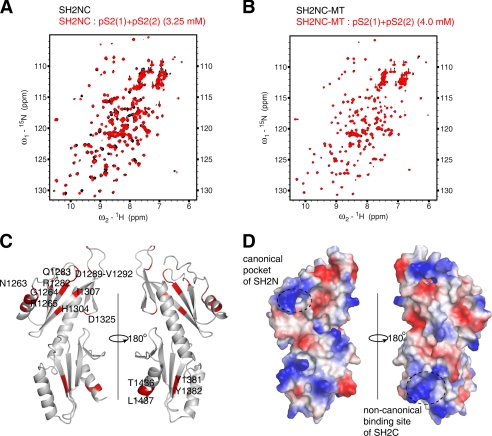

Tandem SH2 Domains Bind to Phosphorylated RNAPII CTD

The interaction between the tandem SH2 domains and phosphorylated the RNAPII CTD peptides was investigated using chemical shift perturbation experiments. Eight unmodified or phosphorylated RNAPII CTD peptides were titrated into the 15N-labeled protein, respectively (Table 2). All of the phosphorylated peptides induced a number of distinct chemical shift perturbations in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of SH2NC, whereas no perturbation was found for the unmodified peptide (Fig. 4 and supplemental Fig. S2), indicating that the interaction between the SH2NC module and the RNAPII CTD is phosphorylation-dependent. On the other hand, the observation of a single set of resonances averaged over the bound and free states in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra suggested that the interaction between the phosphorylated peptide and the protein was in the realm of fast exchange.

TABLE 2.

Binding affinity of the Spt6 tandem SH2 domains or single SH2N domain to the different RNAPII CTD peptides

| Peptide | Sequence | Dissociation constant Kd (mm) |

|---|---|---|

| pY1 | TSPS(pY)SPTSPSa | 1.1 ± 0.1 |

| pS2 | SPSY(pS)PTSPSb | 3.2 ± 0.1 |

| pS5 | SYSPT(pS)PSYSPTb | 5.3 ± 0.1 |

| pS7 | PTSP(pS)YSPTSb | 8.0 ± 0.5 |

| pS2+pS5 | SPSY(pS)PT(pS)PSYSPTb | 1.4 ± 0.1 |

| pS2(1)+pS2(2) | SY(pS)PTSPSY(pS)PTSPSb | 1.5 ± 0.2 |

| pS2(1)+pS2(3) | TSPSY(pS)PTSPSYSPTSPSY (pS)PTSPSb | 1.2 ± 0.1 |

| pS2(1)+pS2(2) (titrated to SH2N) | SY(pS)PTSPSY(pS)PTSPSb | 2.5 ± 0.2 |

| Unmodified | YSPTSPSYSPTSPS | No binding |

a pY refers to phosphotyrosine.

b pS refers to phosphoserine.

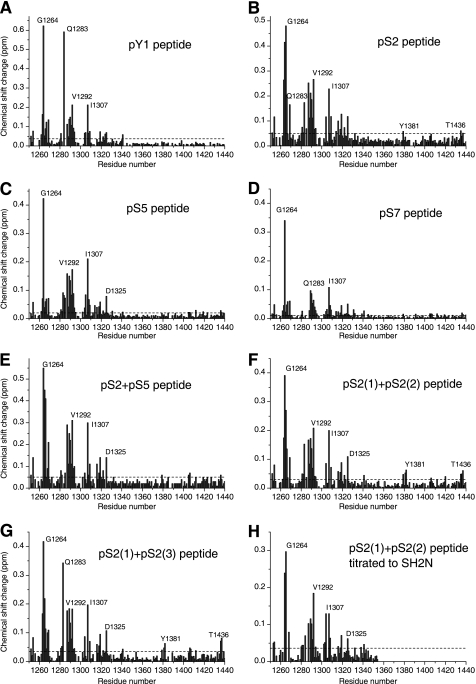

FIGURE 4.

The histogram plot of the chemical shift changes of the tandem SH2 domains induced by the phosphorylated RNAPII CTD peptides. The peptide name is labeled on the top of each subfigure. The horizontal dashed line denotes the mean value of the chemical shift change. The labeled residues are located around the canonical pocket of the SH2N domain or the noncanonical binding site of the SH2C domain.

Yoh and coworkers (18) have reported that Spt6 preferentially binds to Ser2-phosphorylated (pS2) over Ser5-phosphorylated (pS5) RNAPII CTD. Our data confirmed that the binding affinity of SH2NC module to the pS2 peptide is higher than to the pS5 peptide (see Table 2). More interestingly, the pY1 peptide showed the highest binding affinity. We found that the tandem SH2 domains also bound to pS7, which is a recently confirmed phosphorylation site for RNAPII CTD (3, 26).

Double phosphorylation at Ser2 and Ser5 were identified previously in the same RNAPII CTD repeat (6, 7). We wanted to investigate whether these two phosphorylations act cooperatively in the interaction between Spt6 and RNAPII CTD. We found that adding pS5 to the pS2 peptide increased the binding affinity by ∼2-fold. This result reveals that the simultaneous phosphorylation of Ser2 and Ser5 in the same repeat enhances the association between RNAPII CTD and Spt6 but does not exhibit a synergistic effect.

We also investigated whether longer peptides with multiple phosphorylation sites would bind more tightly to the SH2NC module, which presumably has two binding pockets for RNAPII CTD. Indeed, both the two-repeat peptide pS2(1)+pS(2) and the three-repeat peptide pS2(1)+pS2(3) with both Ser2 sites phosphorylated have 2∼3 times higher affinities than the single repeat pS2 peptide (Table 2). These results show that SH2NC preferentially binds to RNAPII CTD peptides with double or multiple phosphorylation sites. Furthermore, it appears that two consecutive repeats is long enough to span the binding sites in these two SH2 domains, as indicated by the similar affinities of the pS2(1)+pS2(2) and pS2(1)+pS2(3) peptides.

Using solution NMR, we showed that the SH2NC module of Spt6 bound to both phosphoserine and phosphotyrosine residues of RNAPII CTD with very low affinities (mm), which are difficult to detect by other analytical techniques such as fluorescence polarization, surface plasma resonance or isothermal titration calorimetry (23). Our work also confirmed that NMR is well suited to unravel extremely weak protein-protein interactions (36).

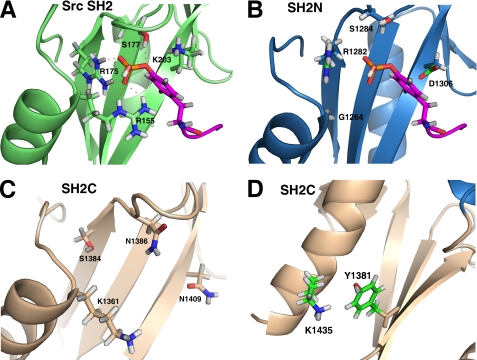

Interaction Surface on Tandem SH2 Domains

All phosphorylated RNAPII CTD peptides perturbed almost the same region in the SH2N domain (Fig. 4, A–E), whereas only a few residues in the SH2C domain were weakly affected by the Ser2 phosphorylated peptides. In the case of the pS2 peptide, significantly perturbed residues (with a chemical shift change above average) in the SH2N domain included Asn1263, Gly1264, Arg1265, Gln1266, Asp1269, Arg1282, Asp1289–Val1292, His1304, Ile1307, Leu1316, Gly1319, and Asp1325 (Figs. 4B and 5C). Arg1282 is an invariant residue corresponding to Arg175 in the Src SH2 domain (Fig. 6, A and B), which binds to phosphate through its positively charged side chain (Fig. 6A) (37). Other perturbed residues, except Leu1316 and Gly1319, are located around the canonical binding pocket of the SH2N domain (Fig. 5, C and D). Among them, residues Asn1263, Gly1264, Arg1265, Gln1266, and Asp1269 reside in the αA1 helix that is close to the side chain of R1282. Residues Asp1289–Val1292 are in the βC1 strand opposite to Arg1282, whereas His1304 and Ile1307 are two residues located between the canonical pocket and the EF loop. In the Src SH2 domain, the EF loop is involved in the recognition of the C-terminal hydrophobic residues of phosphotyrosine (37). However, in the SH2N domain, only one residue (Asp1325) in this region was slightly perturbed (Fig. 4C).

FIGURE 5.

Chemical shift perturbation experiments revealed the interaction surface of the SH2NC module with the phosphorylated RNAPII CTD peptides. A, the overlay of the HSQC spectra of the SH2NC module in the free state and in the presence of the pS2(1)+pS2(2) peptide. B, the pS2(1)+pS2(2) peptide could not perturb the resonance of the SH2NC-MT mutant (R1282A/S1283A/Y1381F/K1435A). C, a schematic mapping the binding interface of the pS2(1)+pS2(2) peptide onto the tandem SH2 domains. D, the canonical phosphate binding pocket of SH2N and the noncanonical binding site of SH2C on the electrostatic surface.

FIGURE 6.

Phosphate binding pocket comparison between Src SH2 and the two SH2 domains of Spt6. A, the Arg155, Arg175, and Ser177 residues in Src SH2 (PDB code 1SPS) form hydrogen bonds with phosphotyrosine. The side chain amides of Arg155 and Lys203 attract the aromatic ring of phosphotyrosine. The red dashed lines denote the hydrogen bonds formed between Src SH2 and phosphate (purple). B, a model of the SH2N domain complexed with a phosphotyrosine. Arg1282 and Ser1284 can presumably form hydrogen bonds with the phosphate, but Gly1264 and Asp1306 are unfavorable to accommodate the aromatic ring of phosphotyrosine. C, the region of SH2C corresponding to the canonical pocket lacks the critical residues for phosphate binding. Ser1384 and Asn1386 substitute for the critical residues corresponding to Arg175 and Ser177 in Src SH2. D, two invariant residues (Tyr1381 and Lys1435) in SH2C are close in space and presumably attract the phosphate group of RNAPII CTD.

Compared with pY1, pS5, and pS7 peptides, both the single repeat pS2 peptide and the double Ser2 phosphorylated peptides (pS2(2)+pS2(2) and pS2(1)+pS2(3)) had titrations that resulted in a weak chemical shift perturbation of a few residues in the SH2C domain. Interestingly, all of these perturbed residues (Tyr1381, Tyr1382, Thr1436, and Leu1437) are located on a positively charged surface where two invariant residues, Tyr1381 and Lys1435, are found (Fig. 5, C and D). The structural analysis and sequence alignment of the SH2C domains from different species showed a high degree of conservation of this positively charged surface. In contrast, in the region corresponding to the canonical binding pocket of a canonical SH2 domain, the critical arginine residue in the βB2 strand is replaced by a serine (Ser1384) (Fig. 6C). More importantly, no residues in this area experienced a chemical shift perturbation. These results indicate that the SH2C loses its canonical phosphate binding pocket but uses a novel binding site to recognize phosphoserine.

Both SH2 Domains Contribute to RNAPII CTD Binding

Compared with the SH2N domain, the chemical shift perturbation of the SH2C domain was much weaker upon titration with the phosphorylated RNAPII CTD peptides (Fig. 4). To find out whether both domains were essential for RNAPII CTD binding, we tried to express the single SH2N and the single SH2C domain alone. However, the SH2C domain is expressed in inclusion bodies, possibly due to the solvent exposure of the interdomain hydrophobic interface. Fortunately, the single SH2N domain was soluble and stable enough for NMR analysis. We successfully assigned the backbone resonances of the separated SH2N domain and titrated it with the double Ser2 phosphorylated peptide pS2(1)+pS2(2). The peptide induced a similar perturbation to the same residues as those in the SH2NC module (Fig. 4H). However, an increase in the dissociation constant from 1.5 ± 0.2 mm (for SH2NC) to 2.5 ± 0.2 mm was observed (supplemental Fig. S3). Furthermore, the simultaneous mutation of both binding sites (R1282A, S1283A, Y1381F, and K1435A) in the SH2N and SH2C domains completely abolished the interaction between the SH2NC module and the pS2(1)+pS2(2) peptide (Fig. 5B). These results suggested that both the SH2N and the SH2C domains contribute to the interaction between Spt6 and phosphorylated RNAPII CTD.

DISCUSSION

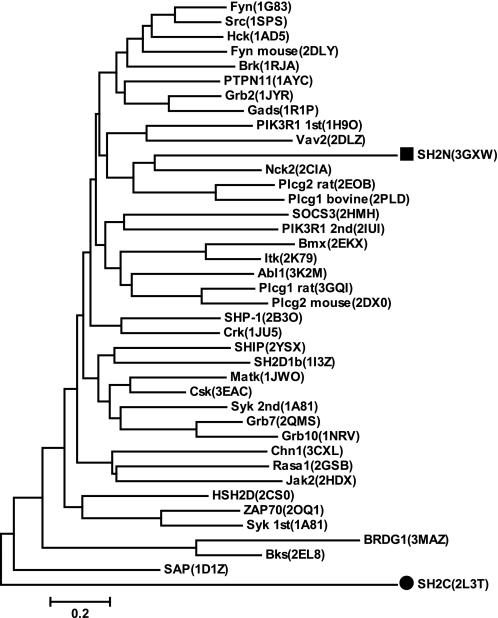

SH2C Domain Represents a Novel SH2 Subfamily

The SH2 domain is a widespread protein interaction module and is involved in various cell functions such as cell surface receptor signal transduction, protein trafficking, cell cycle progression, gene expression, DNA repair, and cell polarity (38, 39). Canonical SH2 domains specifically recognize phosphotyrosine with relatively high affinity (μm) (37).

Canonical SH2 domains, such as the Src SH2 domain, have a phosphate binding pocket around a highly conserved arginine residue in the βB strand, whose side chain forms a hydrogen bond with the phosphate group of its binding partner. This arginine is highly conserved even in the SH2 domains that can bind unmodified peptides, such as SAP and CTEN SH2 (40, 41). However, in the yeast Spt6 SH2C domain, this characteristic arginine residue is replaced by a serine (Ser1384) (Figs. 2 and 6C). The phylogenetic tree in Fig. 7 suggests that there is no close evolutionary relationship between the Spt6 SH2C domain and any other SH2 domains with known structures. Interestingly, two residues (Tyr1381 and Lys1435) in the noncanonical phosphate binding site are totally invariant in all aligned species (Fig. 2). All of these analyses suggest that the Spt6 SH2C domain represents a novel SH2 domain subfamily, which has a noncanonical binding site for phosphoserine.

FIGURE 7.

Phylogenetic tree for the SH2 domains of Spt6 and their homologues in the PDB database. The PDB accession codes are given in parentheses. The SH2N and SH2C domains from yeast Spt6 are indicated with ■ and ●, respectively.

Structural Basis for Interaction between SH2NC Module and Phosphorylated RNAPII CTD

Our NMR studies reveal that the SH2N domain binds to the phosphoserine and phosphotyrosine of RNAPII CTD with millimolar affinity, which is ∼1000 times lower than the canonical SH2 to phosphotyrosine binding affinity. The canonical Src SH2 domain binds to phosphotyrosine using a highly conserved arginine (Arg175) and a less well conserved serine (Ser177) (Fig. 6A). A region around the EF loop recognizes the +3 to +5 residues downstream of the phosphotyrosine and defines the sequence specificity. This binding mode has been called the “two-pronged” model (37). Canonical SH2 domains accommodate the phosphotyrosine aromatic ring through the attraction between the side chain amino groups of Arg155/Lys203 and the π-electron of phosphotyrosine (37). However, in the SH2N domain of Spt6, these two residues corresponding to Arg155 and Lys203 are replaced by Gly1264 and Asp1306 (Fig. 4A). Residue Gly1264 lacks a side chain to attract the aromatic ring, whereas the negatively charged Asp1306 may repel the π-electron of the phosphotyrosine. These residue differences help explain why the binding affinity of the SH2N domain to phosphotyrosine drops dramatically (to the millimolar range) despite the retention of the phosphate binding arginine (Arg1282) and serine (Ser1284). The binding fidelity of the canonical pocket of the SH2N domain is also affected so that now both phosphoserine and phosphotyrosine can bind to SH2N.

In all of the titration experiments, only one residue (Asp1325) of the EF loop was weakly perturbed upon the addition of a phosphorylated RNAPII CTD peptide (Fig. 4), indicating that the EF loop is only marginally involved in the binding with RNAPII CTD. This result is consistent with the fact that the SH2N domain shows little selectivity toward the C-terminal residues of the phosphorylation site. In a typical SH2 and phosphotyrosine interaction, the binding strength is mostly determined by the recognition of the phosphotyrosine, which contributes more than half of the binding free energy (42). Thus, the electrostatic interaction between the side chains of residues Arg1282/Ser1284 and the phosphate group should contribute the majority of the binding energy of the SH2N domain.

Our data also indicated that the SH2C domain has a noncanonical phosphate binding site for phosphoserine. Based on the structural analysis and chemical shift perturbation information, a conserved positively charged site around Tyr1381 and Lys1435 was found that weakly bound to Ser2-phosphorylated RNAPII CTD.

Physiological Relevance of Binding between Tandem SH2 Domains and Phosphorylated RNAPII CTD

Our NMR studies indicated that the SH2NC module of Spt6 exhibited only very weak binding affinity (in the millimolar range) to short phosphorylated RNAPII CTD peptides in vitro. However, it was demonstrated that the SH2NC module could readily pull down the hyperphosphorylated full-length RNAPII from a cell extract in an Ser2 phosphorylation-dependent manner (18). Disruption of this phosphorylation-dependent binding between Spt6 and RNAPII CTD causes transcription reinitiation from a cryptic promoter and a high level of mRNA accumulation in the nucleus (15, 18).

The in vivo binding of SH2NC to RNAPII CTD could be enhanced significantly. The most possible scenario would be that dozens of YSPTSPS repeats of RNAPII are simultaneously phosphorylated at multiple sites and that this dramatically increases the effective local concentration of the recognition sites for the SH2NC module to facilitate the recruitment of Spt6. Our chemical shift perturbation experiments indicated that the double phosphorylation in either the same (pS2+pS5 peptide) or different repeat units (pS2(1)+pS2(2) and pS2(1)+pS2(3) peptides) could additively increase the affinity of the SH2NC module to RNAPII CTD. However, the small enhancement also showed that the double phosphorylation in the same or different repeats was not synergistic. Given this observation, the SH2NC module may function as a sensor for the phosphate density in RNAPII CTD, i.e. the higher the phosphorylation level of RNAPII CTD, the tighter the binding between Spt6 and RNAPII.

Another way to enhance the association between Spt6 and RNAPII is that a third RNAPII-associated factor tethers Spt6 in the proximity of RNAPII CTD, thereby increasing the chance of an encounter between SH2NC and RNAPII CTD. For example, it has been reported that Spt6 co-immunoprecipitates with RNAPII, Pob3, Spt16, Spt4, and Spt5 (43) and that Spt5 associates with RNAPII in vivo (13). Recently, Mayer et al. (44) reported a genome-wide occupancy profile of the different phosphorylated forms of RNAPII and Spt6 along the top 50% of the most highly expressed genes in yeast. They found that the deletion of the SH2NC module led to much less recruitment of Spt6 to RNAPII but did not completely abolish this process (44). This finding not only has proven that the SH2NC module is required for the recruitment of Spt6 to phosphorylated RNAPII during transcription but also supports the idea that there is another mechanism for Spt6 association with RNAPII, which is independent of the binding between SH2NC and RNAPII CTD.

We found that the SH2NC module of Spt6 also weakly binds to pS7 NAPII CTD, which was a newly discovered modification event of RNAPII CTD (3, 26) catalyzed by the same kinase complex (TFIIH) as for Ser5 (4). This RNAPII CTD phosphorylation can be detected in both protein coding and snRNA genes (26). Substituting Ser7 with an alanine residue did not affect the transcription or processing of protein-coding genes but dramatically reduced the transcription and processing of two spliceosomal snRNA genes (26). Our results implied that Spt6 might be involved in snRNA expression.

Compared with Ser2, Ser5, and Ser7 phosphorylation of RNAPII CTD, the role of Tyr1 phosphorylation in gene transcription and processing has not been studied thoroughly. It has been reported that Tyr1 phosphorylation is catalyzed by c-Abl and Abl-related gene (Arg) kinases in DNA damage response in mammalian cells (1, 25). DNA damage in the coding region of a gene can cause arrest the RNAPII-directed transcription and trigger a process called transcription-coupled repair to remove the lesion in the transcribed strand (45). Because the SH2NC modules are conserved from yeast to humans, we assume that mammalian Spt6 also has the ability to bind to pY1 RNAPII CTD and might participate in the transcription coupled DNA repair.

Broad involvement of Spt6 in the transcription cycle depends on its association with RNAPII. The ability to bind to different phosphorylated forms of RNAPII CTD is critical for the recruitment of Spt6 to dynamically phosphorylated RNAPII. We find that Spt6 directly binds to Tyr1-, Ser2-, Ser5-, or Ser7-phosphorylated RNAPII CTD. We propose that the SH2NC module of Spt6 probably functions as a sensor for the phosphate density in RNAPII CTD and regulates the interaction between Spt6 and RNAPII. In addition, our data also suggest that Spt6 may play a role in snRNA expression and transcription-coupled DNA repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Dr. Haiyan Liu, Dr. Yu Xue, and Dr. Ziliang Qian for helpful discussions about phylogenetic analysis. All structure figures were produced with PyMOL (46).

This work is supported by grants from the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation (Grant 30830031), the National Basic Research Program of China (Grants 2011CB966302 and 2011CB911104), and the Chinese National High Technology R&D Program (Grant 2006AA02A315).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2L3T) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3 and data set 1.

- CTD

- C-terminal domain

- RNAPII

- RNA polymerase II

- Bis-Tris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- TOCSY

- total correlation spectroscopy

- NOESY

- nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy

- RDC

- residual dipolar coupling.

REFERENCES

- 1. Baskaran R., Chiang G. G., Mysliwiec T., Kruh G. D., Wang J. Y. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18905–18909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dahmus M. E. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19009–19012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chapman R. D., Heidemann M., Albert T. K., Mailhammer R., Flatley A., Meisterernst M., Kremmer E., Eick D. (2007) Science 318, 1780–1782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akhtar M. S., Heidemann M., Tietjen J. R., Zhang D. W., Chapman R. D., Eick D., Ansari A. Z. (2009) Mol. Cell 34, 387–393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim M., Suh H., Cho E. J., Buratowski S. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 26421–26426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Komarnitsky P., Cho E. J., Buratowski S. (2000) Genes Dev. 14, 2452–2460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Egloff S., Murphy S. (2008) Trends Genet. 24, 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Buratowski S. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 679–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Corden J. L. (2007) Science 318, 1735–1736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Meinhart A., Kamenski T., Hoeppner S., Baumli S., Cramer P. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1401–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ardehali M. B., Yao J., Adelman K., Fuda N. J., Petesch S. J., Webb W. W., Lis J. T. (2009) EMBO J. 28, 1067–1077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bortvin A., Winston F. (1996) Science 272, 1473–1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hartzog G. A., Wada T., Handa H., Winston F. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 357–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Endoh M., Zhu W., Hasegawa J., Watanabe H., Kim D. K., Aida M., Inukai N., Narita T., Yamada T., Furuya A., Sato H., Yamaguchi Y., Mandal S. S., Reinberg D., Wada T., Handa H. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 3324–3336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaplan C. D., Laprade L., Winston F. (2003) Science 301, 1096–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yoh S. M., Lucas J. S., Jones K. A. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 3422–3434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Youdell M. L., Kizer K. O., Kisseleva-Romanova E., Fuchs S. M., Duro E., Strahl B. D., Mellor J. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 4915–4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoh S. M., Cho H., Pickle L., Evans R. M., Jones K. A. (2007) Genes Dev. 21, 160–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Svejstrup J. Q. (2003) Science 301, 1053–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Belotserkovskaya R., Reinberg D. (2004) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14, 139–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adkins M. W., Tyler J. K. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 405–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sun M., Larivière L., Dengl S., Mayer A., Cramer P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41597–41603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Diebold M. L., Loeliger E., Koch M., Winston F., Cavarelli J., Romier C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 38389–38398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Close D., Johnson S. J., Sdano M. A., McDonald S. M., Robinson H., Formosa T., Hill C. P. (2011) J. Mol. Biol. 408, 697–713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Duyster J., Baskaran R., Wang J. Y. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 1555–1559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Egloff S., O'Reilly D., Chapman R. D., Taylor A., Tanzhaus K., Pitts L., Eick D., Murphy S. (2007) Science 318, 1777–1779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tjandra N., Bax A. (1997) Science 278, 1111–1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ottiger M., Delaglio F., Bax A. (1998) J. Magn. Reson. 131, 373–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Farrow N. A., Muhandiram R., Singer A. U., Pascal S. M., Kay C. M., Gish G., Shoelson S. E., Pawson T., Forman-Kay J. D., Kay L. E. (1994) Biochemistry 33, 5984–6003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Goddard T. D., Kneller D. G. (2008) SPARKY 3, Version 3.114, University of California, San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- 31. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schwieters C. D., Kuszewski J. J., Tjandra N., Clore G. M. (2003) J. Magn. Reson. 160, 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Holm L., Rosenström P. (2010) Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W545–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Thompson J. D., Higgins D. G., Gibson T. J. (1994) Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tamura K., Dudley J., Nei M., Kumar S. (2007) Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vaynberg J., Qin J. (2006) Trends Biotechnol. 24, 22–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Waksman G., Shoelson S. E., Pant N., Cowburn D., Kuriyan J. (1993) Cell 72, 779–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pawson T., Gish G. D., Nash P. (2001) Trends Cell Biol. 11, 504–511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Liu B. A., Jablonowski K., Raina M., Arcé M., Pawson T., Nash P. D. (2006) Mol. Cell 22, 851–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Poy F., Yaffe M. B., Sayos J., Saxena K., Morra M., Sumegi J., Cantley L. C., Terhorst C., Eck M. J. (1999) Mol. Cell 4, 555–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liao Y. C., Si L., deVere White R. W., Lo S. H. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176, 43–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gan W., Roux B. (2009) Proteins 74, 996–1007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lindstrom D. L., Squazzo S. L., Muster N., Burckin T. A., Wachter K. C., Emigh C. A., McCleery J. A., Yates J. R., 3rd, Hartzog G. A. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1368–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Mayer A., Lidschreiber M., Siebert M., Leike K., Söding J., Cramer P. (2010) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1272–1278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hanawalt P. C., Spivak G. (2008) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 958–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3, Schrödinger, LLC, San Carlos, CA [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gouet P., Robert X., Courcelle E. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3320–3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.