Abstract

α,β-Unsaturated aldehydes generated during lipid peroxidation, such as 4-oxoalkenals and 4-hydroxyalkenals, can give rise to protein degeneration in a variety of pathological states. Although the covalent modification of proteins by these end products has been well studied, the reactivity of unstable intermediates possessing a hydroperoxy group, such as 4-hydroperoxy-2-nonenal (HPNE), with protein has received little attention. We have now established a unique protein modification in which the 4-hydroperoxy group of HPNE is involved in the formation of structurally unusual lysine adducts. In addition, we showed that one of the HPNE-specific lysine adducts constitutes the epitope of a monoclonal antibody raised against the HPNE-modified protein. Upon incubation with bovine serum albumin, HPNE preferentially reacted with the lysine residues. By employing Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine, we detected two major products containing one HPNE molecule per peptide. Based on the chemical and spectroscopic evidence, the products were identified to be the Nα-benzoylglycyl derivatives of Nϵ-4-hydroxynonanoic acid-lysine and Nϵ-4-hydroxy-(2Z)-nonenoyllysine, both of which are suggested to be formed through mechanisms in which the initial HPNE-lysine adducts undergo Baeyer-Villiger-like reactions proceeding through an intramolecular oxidation catalyzed by the hydroperoxy group. On the other hand, using an HPNE-modified protein as the immunogen, we raised a monoclonal antibody against the HPNE-modified protein and identified one of the HPNE-specific lysine adducts, Nϵ-4-hydroxynonanoic acid-lysine, as an intrinsic epitope of the monoclonal antibody. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the HPNE-specific epitopes were produced not only in the oxidized low density lipoprotein in vitro but also in the atherosclerotic lesions. These results indicated that HPNE is not just an intermediate but also a reactive molecule that could covalently modify proteins in biological systems.

Keywords: Immunochemistry, Lipid Oxidation, Oxidative Stress, Post-translational Modification, Protein Chemical Modification

Introduction

Lipid peroxidation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases, including atherosclerosis, diabetes, cancer, and rheumatoid arthritis, as well as in drug-associated toxicity, postischemic reoxygenation injury, and aging (1). Lipid peroxidation proceeds by a free radical chain reaction mechanism and yields lipid hydroperoxides as the major initial reaction products. Subsequently, the decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides generates a number of breakdown products that display a wide variety of damaging actions (2). Among them are a variety of different aldehydes. The primary products of lipid peroxidation, lipid hydroperoxides, can undergo carbon-carbon bond cleavage via alkoxyl radicals in the presence of transition metals, giving rise to the formation of short-chain, unesterified aldehydes of 3–9 carbons in length and a second class of aldehydes still esterified to the parent lipid (2). The important agents that give rise to the modification of a protein may be represented by reactive aldehydic intermediates, such as 2-alkenals, 4-oxo-2-alkenals, and 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals (2–4). These α,β-unsaturated aldehydes are considered important mediators of cell damage due to their ability to covalently modify biomolecules, which can disrupt important cellular functions and can cause mutations (2). Furthermore, the adduction of aldehydes to the apolipoprotein B in low density lipoproteins (LDL) has been strongly implicated in the mechanism by which LDL is converted to the atherogenic form that is taken up by macrophages, leading to the formation of foam cells (5, 6). Among the variety of lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes, 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal (HNE)2 is a major product of lipid peroxidation and is believed to be largely responsible for the cytopathological effects observed during oxidative stress (2, 7). HNE exerts these effects because of its facile reactivity with biological materials, including proteins (2, 7). Upon the reaction with protein, HNE specifically reacts with nucleophilic amino acids, such as cysteine, histidine, and lysine, to form their Michael addition adducts possessing a carbonyl functionality.

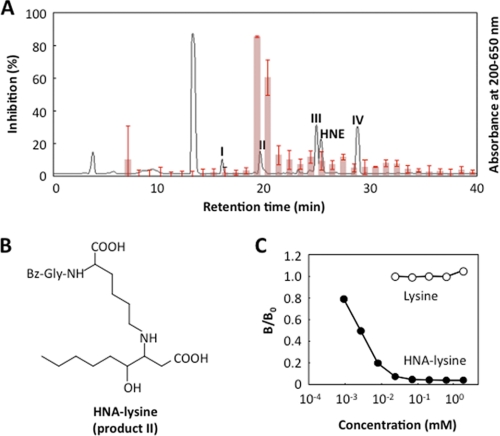

It is generally believed that HNE is directly formed through reduction of 4-hydroperoxy-2-nonenal (HPNE), the 4-hydroperoxy analog of HNE. HPNE was originally recognized as an enzymatic product of the ω6-polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism in plants (8). Brash and colleagues (9) reported that the formation of HPNE is also generated through a Hock rearrangement during homolytic decomposition of the prototypic polyunsaturated fatty acid hydroperoxide, 13-[S-(Z,E)]-9,11-hydroperoxyoctadecadienoic acid. Moreover, they established two distinct mechanisms leading to the formation of HNE via HPNE in which the allylic hydrogen abstraction at C-8 of 13S-HPODE leads to a 10,13-dihydroperoxide that undergoes cleavage between C-9 and C-10 to give 4S-HPNE, whereas 9S-HPODE directly cleaves to (3Z)-nonenal as a precursor of the racemic HPNE (9–11). Beside HNE, HPNE has been reported to generate 4-oxo-2-nonenal (ONE) (12, 13), a particularly potent lipid hydroperoxide-derived genotoxin that can readily react with nucleophilic biomacromolecules, such as protein and DNA (14). Thus, HPNE has been recognized as a direct precursor of the most representative α,β-unsaturated aldehydes, HNE and ONE (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

HPNE as a precursor of ONE and HNE during the peroxidation of ω6-polyunsaturated fatty acids.

On the other hand, due to the unstable nature of the hydroperoxy group, HPNE has received relatively little attention as the causative agent for modification of nucleophilic biomolecules. In the present study, we characterized the HPNE modification of lysine residues, identified two novel HPNE-specific lysine adducts, and established a unique adduction mechanism, in which the 4-hydroperoxy group of HPNE is involved in the adduction chemistry. In addition, we showed that one of the HPNE-specific lysine adducts constitutes the epitope of a monoclonal antibody (mAb) raised against the HPNE-modified protein. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the HPNE-specific epitopes were indeed generated not only in the oxidized low density lipoprotein in vitro but also in the atherosclerotic lesions in vivo. These results indicate that HPNE is not just a precursor of HNE and ONE but also a reactive molecule that could directly modify proteins in biological systems.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

(3Z)-Nonenol and pyridiniumchlorochromate were obtained from TCI (Tokyo, Japan). Nα-Benzoylglycyl-lysine was obtained from the Peptide Institute, Inc. (Osaka, Japan). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was obtained from Wako (Osaka, Japan).

General Procedures

The 1H NMR spectra (400 or 600 MHz) and 13C NMR spectra (100 or 150 MHz) were recorded at 27 °C on an AMX 400 (400 MHz) or an AMX 600 (600 MHz) spectrometer (Bruker, Rheinstetten, Germany). In all cases, tetramethylsilane or the solvent peak served as the internal standard for reporting the chemical shifts, which are expressed as parts per million downfield from tetramethylsilane (δ scale). The 1H-1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY), 1H-detected heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (HMQC), and 1H-detected heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) experiments were carried out using an AMX 400 (400 MHz) or an AMX 600 (600 MHz) instrument. The UPLC-MS analysis was carried out using a Waters Acquity UPLC system (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) coupled to a Waters Acquity TQD tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer (Waters) with electrospray ionization (ESI) in the positive and negative modes. The high resolution mass spectral data were obtained using a Mariner Biospectrometry work station (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) in the positive ESI mode. High performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted using a JASCO system (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan).

Preparation of HPNE

HPNE was prepared by the autoxidation of (3Z)-nonenal (15, 16). Briefly, to a NaOAc-buffered solution (54 mg, 0.4 mmol) of pyridiniumchlorochromate (231 mg, 2 mmol, 2 eq) in 4 ml of methylene chloride, (3Z)-nonenol (142 mg, 1 mmol) dissolved in 2 ml of methylene chloride was added. After stirring for 30 min at room temperature, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 20 ml of diethyl ether and immediately filtered through a column of silica gel eluted with methylene chloride to remove the oxidizing agent. The crude product was isolated by open bed column chromatography (silica gel, hexane/EtOAc (90:10) (v/v)). In the autoxidation reaction, (3Z)-nonenal was dissolved in a 1:1 mixture of water/acetonitrile and bubbled with oxygen for 18 h at ambient temperature. After extracting with hexane, an aqueous layer was injected on a preparative C18 column (10 × 250 mm; ChromaNik, Osaka, Japan) eluted with a solvent of acetonitrile/water/TFA (53:47:0.1, v/v/v) at the flow rate of 2.5 ml/min and monitored by UV 220 nm. The collected product was evaporated from acetonitrile and then extracted using a 100-mg C18 Sep-Pak cartridge (Waters) eluted with acetonitrile.

In Vitro Modification of BSA

Modification of the protein by HPNE was performed by incubating BSA (1.0 mg/ml) with 0.5–10 mm HPNE in 1.0 ml of 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 24 h.

SDS-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

SDS-PAGE was performed according to Laemmli (17). The protein was stained with Coomassie Blue.

Amino Acid Analysis

An aliquot (0.1 ml) of the protein samples (1.0 mg/ml) incubated for 24 h at 37 °C in the absence or presence of HPNE was treated with 10 mm EDTA (10 μl), 1 n NaOH (10 μl), and 100 mm sodium borohydride (10 μl). After incubation for 1 h at room temperature, 10 μl of 2 n HCl was added to the mixture to stop the reaction, and the mixture was then incubated for 60 min at room temperature after adding 140 μl of 20% trichloroacetic acid. After centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, the proteins were hydrolyzed in vacuo with 2 ml of 6 n HCl for 24 h at 110 °C. The hydrolysates were then dried and dissolved in sodium citrate buffer, pH 3.15. The amino acid analysis was performed using a JEOL JLC-500 amino acid analyzer equipped with a JEOL LC30-DK20 data-analyzing system.

Reaction of Nα-Benzoylglycyl-lysine with HPNE

The reaction mixture containing 5 mm Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine was incubated with 5 mm HPNE in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After incubation for 0–24 h at 37 °C, the reaction mixtures were analyzed by a reverse-phase HPLC on a ChromaNik Sunniest RP-AQUA column (4.6-mm inner diameter × 250 mm; ChromaNik, Osaka, Japan) eluted with a linear gradient of water containing 0.1% TFA (solvent A)-acetonitrile (solvent B) (time = 0 min, 2% B; 40–50 min, 100% B) at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. The elution profiles were monitored by absorbance at 200–650 nm.

Identification of Reaction Products

HPNE (5 mm) was added to a solution of Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine (5 mm) in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, the mixture was subjected to preparative HPLC on a ChromaNik Sunniest RP-AQUA column (10.0-mm inner diameter × 250 mm; ChromaNik, Osaka, Japan) using a gradient of 10–60% aqueous CH3CN containing 0.1% TFA. The products I–IV were further purified by preparative HPLC on the same column under each of the elution conditions.

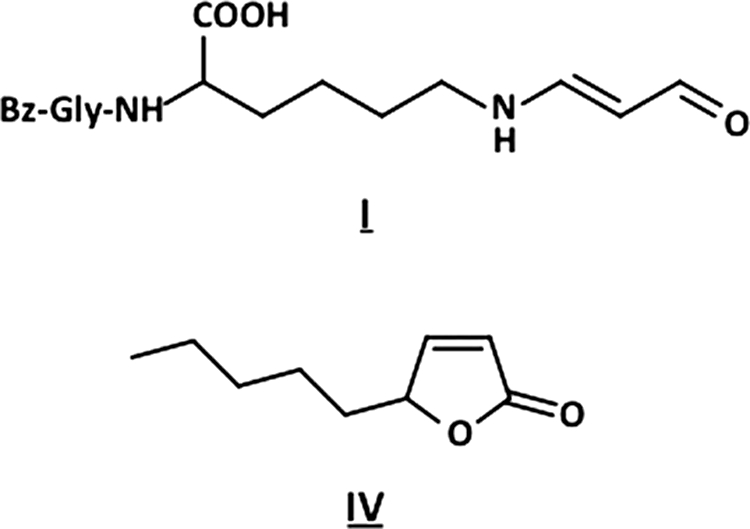

2-[(2-Benzamidoacetyl)amino]-6-[[(E)-3-oxoprop-1-enyl]amino]hexanoic acid (I)

A secondary purification was conducted using 21% aqueous CH3CN containing 0.1% TFA to give I (1.6%, based on HPNE). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 8.94 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-3), 7.86 (2H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, H-11′, 15′), 7.53 (1H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-13′), 7.46 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, H-12′, 14′), 7.24 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 13.2 Hz, H-1), 5.03 (1H, dd, J = 8.4, 13.2 Hz, H-2), 4.17 (1H, m, H-5′), 3.91 (2H, dd, J = 6.0, 16.2 Hz, H-8′), 2.96 (2H, m, H-1′), 1.71 (1H, m, H-4′), 1.60 (1H, m, H-4′),1.48 (2H, m, H-2′), 1.33 (2H, m, H-3′). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 188.6 (C-3), 173.6 (C-6′), 168.9 (C-7′), 166.6 (C-9′), 157.7 (C-1), 134.1 (C-10′), 131.4 (C-13′), 128.4 (C-12′, 14′), 127.4 (C-11′, 15′), 100.0 (C-2), 52.1 (C-5), 42.7 (C-1′), 42.5 (C-8′), 31.1 (C-4′), 27.2 (C-2′), 22.8 (C-3′). HR-ESI-MS: m/z 362.1684 (calcd for C18H23N3O5 + H: 362.1710).

3-[[5-[(2-Benzamidoacetyl)amino]-6-hydroxy-6-oxo-hexyl]amino]-4-hydroxynonanoic Acid (II)

A secondary purification was conducted using 25% aqueous CH3CN containing 0.1% TFA to give II (4.4%, based on HPNE). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.89 (2H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-11′, 15′), 7.52 (1H, t, J = 3.6 Hz, H-13′), 7.46 (2H, d, J = 7.8 Hz, H-12′, 14′), 4.18 (1H, m, H-5′), 3.93 (2H, m, H-8′), 3.43 (1H, overlapped with solvent), 2.94 (1H, m, H-3), 2.81 (2H, m, H-1′), 2.30 (1H, dd, J = 4.2, 16.8 Hz, H-2), 2.15 (1H, dd, J = 6.0, 16.8 Hz, H-2), 1.72 (2H, m, H-4′), 1.55 (2H, m, H-2′), 1.44 (1H, m, H-5), 1.42 (1H, m, H-6), 1.36 (1H, m, H-3′), 1.28 (1H, m, H-6), 1.27 (4H, m, H-5, 8, 3′), 1.25 (2H, m, H-7), 0.86 (3H, t, J = 6.6 Hz, H-9). 13C-NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.4 (C-6′), 172.9 (C-1), 168.8 (C-7′), 166.4 (C-9′), 134.1 (C-10′), 131.2 (C-13′), 128.2 (C-12′, 14′), 127.3 (C-11′, 15′), 69.7 (C-4), 59.0 (C-3), 51.7 (C-5′), 44.0 (C-1′), 42.4 (C-8′), 32.9 (C-5), 32.7 (C-2), 31.1 (C-7), 30.5 (C-4′), 26.0 (C-2′), 24.4 (C-6), 22.2 (C-3′), 22.0 (C-8), 13.8 (C-9). HR-ESI-MS: m/z 480.2684 (calcd for C24H37N3O7 + H: 480.2704). The authentic sample was synthesized as follows. A solution of 0.8 g (8.8 mmol) of NaClO2 in 7 ml of water was added dropwise to a stirred mixture of 100 mg (0.2 mmol) of the HNE-Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine Michael adduct in 5 ml of 50% aqueous CH3CN and 160 mg of NaH2PO4 in 2 ml of water and 500 ml of 31% H2O2 at room temperature. After 4 h, a small amount (50 mg) of Na2SO3 was added to destroy the unreacted HOCl and H2O2. The reaction product was evaporated from acetonitrile, extracted using a 100-mg C18 Sep-Pak cartridge eluted with acetonitrile.

2-[(2-Benzamidoacetyl)amino]-6-[[(Z)-4-hydroxynon-2-enoyl]amino]hexanoic Acid (III)

A secondary purification was conducted using 40% aqueous CH3CN containing 0.1% TFA to give III (8.3%, based on HPNE). 1H NMR (600 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 7.87 (2H, d, J = 7.4 Hz, H-11′, 15′), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 7.4 Hz, H-13′), 7.47 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz, H-12′, 14′), 5.86 (1H, dd, J = 7.6, 11.6 Hz, H-3), 5.70 (1H, d, J = 11.6 Hz, H-2), 4.98 (1H, m, H-4), 4.20 (1H, m, H-5′), 3.93 (2H, dd, J = 6.0, 10.4 Hz, H-8′), 3.05 (2H, m, H-1′), 1.71 (1H, m, H-4′), 1.59 (1H, m, H-4′), 1.45–1.18 (12H, m, H-5, 6, 7, 8, 2′, 3′), 0.85 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, H-9). 13C NMR (150 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 173.5 (C-6′), 168.9 (C-7′), 166.4 (C-9′), 165.4 (C-1), 148.1 (C-3), 134.1 (C-10′), 131.3 (C-13′), 128.3 (C-12′, 14′), 127.3 (C-11′, 15′), 121.4 (C-2), 66.3 (C-4), 51.8 (C-5′), 42.2 (C-8′), 38.2 (C-1′), 36.7 (C-5), 31.3 (C-7), 30.9 (C-4′), 28.6 (C-2′), 24.5 (C-6), 22.9 (C-3′), 22.1 (C-8), 13.8 (C-9). HR-ESI-MS: m/z 462.2603 (calcd for C24H35N3O6 + H: 462.2598).

5-Pentylfuran-2H-one (IV)

A secondary purification was conducted using 40% aqueous CH3CN containing 0.1% TFA to give IV (15.1%, based on HPNE). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD3CN): δ 7.60 (1H, dd, J = 1.6, 5.6 Hz, H-3), 6.05 (1H, dd, J = 2.0, 5.6 Hz, H-2), 5.06 (1H, m, H-4), 1.75 (1H, m, H-5), 1.62 (1H, m, H-5), 1.41 (2H, m, H-6), 1.40 (2H, m, H-7), 1.34 (2H, m, H-8), 0.89 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz, H-9). 13C-NMR (100 MHz, CD3CN): δ 174.6 (C-1), 159.1 (C-3), 121.8 (C-2), 84.9 (C-4), 34.1 (C-5), 32.6 (C-8), 25.8 (C-6), 23.5 (C-7), 14.6 (C-9).

Antibody Preparation

The antigen was prepared by incubating keyhole limpet hemocyanin (1.0 mg/ml) with 1 mm HPNE in 5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37 °C for 24 h. Female BALB/c mice were immunized three times with the HPNE-treated keyhole limpet hemocyanin. Spleen cells from the immunized mice were fused with P3U1 murine myeloma cells and cultured in hypoxanthine/amethopterin/thymidine selection medium. The cultured supernatants of the hybridoma were screened using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), employing pairs of wells of microtiter plates on which were absorbed the HPNE-treated BSA as the antigen (500 ng of protein/well). After incubation with 100 μl of the hybridoma supernatants and with intervening washes with PBS, containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS/Tween), the wells were incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG, followed by a substrate solution containing 0.5 mg/ml 1,2-phenylenediamine. Hybridoma cells corresponding to the supernatants that were positive on the HPNE-modified BSA were then cloned by limiting dilution. After repeated screening, two clones were obtained. Among them, clone PM9 showed the most distinctive recognition of the HPNE-modified BSA.

ELISA

A 100-μl aliquot of the antigen solution was added to each well of a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated for 20 h at 4 °C. The antigen solution was then removed, and the plate was washed with PBS containing 0.5% Tween 20 (PBS/Tween). Each well was incubated with 200 μl of 4% Blockace (Yukijirushi, Sapporo, Japan) in PBS/Tween for 60 min at 37 °C to block the unsaturated plastic surface. The plate was then washed three times with PBS/Tween. A 100-μl aliquot of the antibody was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. After discarding the supernatants and washing three times with PBS/Tween, 100 μl of a 5 × 103 dilution of goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase in PBS/Tween was added. After 1 h at 37 °C, the supernatant was discarded, and the plates were washed three times with PBS/Tween. The enzyme-linked antibody bound to the well was revealed by adding 100 μl/well 1,2-phenylenediamine (0.5 mg/ml) in a 0.1 m citrate/phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) containing 0.003% hydrogen peroxide. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 2 m sulfuric acid (50 μl/well), and the absorbance at 490 nm was read using a micro-ELISA plate reader.

In Vitro Oxidation of LDL

LDL (1.019–1.063 g/ml) was prepared from the plasma of healthy humans by sequential ultracentrifugation and then extensively dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (10 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 150 mm NaCl) containing 0.01% EDTA at 4 °C. The LDL used for the oxidative modification by Cu2+ was dialyzed against a 1000-fold volume of PBS at 4 °C. The oxidation of LDL was performed by incubating 0.5 mg of LDL with CuSO4 (10 μm) in 1 ml of 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Informed consent was obtained under the study approved by our institutional review board. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 as revised in 1983.

Agarose Gel Electrophoresis/Immunoblot Analysis

Agarose gel electrophoresis of LDL was performed using the Helena TITAN GEL high resolution protein system (Helena Laboratories, Saitama, Japan). The samples were run on two separate gels. One gel was used for staining with Fat Red 7B; the other was transblotted to nitrocellulose membranes, incubated with Block Ace (40 mg/ml) for blocking, washed, and treated with the primary antibody (mAb PM9). This procedure was followed by the addition of horseradish peroxidase conjugated to a goat anti-mouse IgG and ECL reagents (Amersham Biosciences). The bands were visualized by exposure of the membranes to autoradiography film.

Immunohistochemistry

This investigation was carried out on aortic wall samples obtained at autopsy from patients with generalized arteriosclerosis. Autopsies were performed at Tokyo Women's Medical University after the patients' family members granted informed consent in accordance with local ethics guidelines. Each sample was fixed in 10% formalin, embedded in paraffin, and stored at room temperature. Multiple 6-μm-thick sections were cut from these paraffin-embedded and frozen materials and used for the histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations. Sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated, quenched for 10 min at 4 °C with 3% hydrogen peroxide for inhibiting the endogenous peroxidase activity, rinsed in PBS, subjected to microwaving (95 °C, 400 W, 30 min) in 1 mm Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) for antigen unmasking, pretreated for 30 min at room temperature with 5% skim milk in PBS, and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the mouse monoclonal anti-protein-bound HPNE antibody (Clone PM9) at a dilution of 1:200,000 as well as mouse monoclonal IgG1 antibodies against CD31 (Clone JC/70A) at a dilution of 1:100, CD68 (Clone KP-1) at a dilution of 1:10,000, and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Clone 1A4) at a dilution of 1:2,000. The antibodies to CD31, CD68, and SMA were purchased from Dako (Glostrup, Denmark), and they were used as specific markers of vascular endothelial cells, macrophages, and vascular smooth muscle cells, respectively. Sections processed with omission of the primary antibodies or incubated with 5% skim milk in PBS served as negative reaction controls. The specificity of the anti-protein-bound HPNE antibody was verified by negative staining on sections incubated with the antibody preabsorbed with an excess of the specific antigen (the HNA-lysine adduct) at a concentration of 10 μm or HPNE-modified BSA at a concentration of 0.1 mg/ml. Antibody binding was visualized by the polymer immunocomplex method using the appropriate Envision system (Dako). 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) was used as the chromogen, and hematoxylin was used as the counterstain. Moreover, immunohistochemical localization of the HPNE-specific epitopes was strictly identified by the double immunolabeling method. In brief, sections were incubated with the anti-protein-bound HPNE antibody, and immunoreaction product deposits were detected by the polymer immunocomplex method using DAB (brown), and microphotographs of atherosclerotic lesions were taken. After microwaving (95 °C, 400 W, 10 min) in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for removal of the immune complex, the immunostained sections were incubated with the antibody to CD31, CD68, or SMA, and immunoreaction product deposits were detected by the polymer immunocomplex method using NiCl2-DAB (blue). Immunohistochemical observations of protein-bound HPNE were compared with the initially taken microphotographs of CD31, CD68, and SMA on the same regions by light microscopy.

RESULTS

Covalent Binding of HPNE to BSA

To assess the reactivity of HPNE to protein, BSA (1 mg/ml) was exposed to HPNE (0–10 mm) in vitro. Covalent binding of HPNE to the protein was suggested by a slight expansion and mobility shift of the protein bands on the SDS-PAGE and native PAGE analyses (Fig. 2A). In addition, we examined changes in the amino acid composition and observed that the incubation with HPNE resulted in the loss of the lysine and histidine residues (Fig. 2B), suggesting the covalent binding of HPNE to these amino acids. However, at this stage, it was unclear whether this is a direct action by HPNE or its products, such as HNE and ONE.

FIGURE 2.

Covalent modification of protein by HPNE. A, SDS-PAGE (left) and PAGE (right) analyses of the HPNE-treated BSA. BSA (1 mg/ml) was incubated with 0–10 mm HPNE in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. B, amino acid analysis of the HPNE-treated BSA. The number of histidines (open squares) and lysines (closed circles) that had been lost upon incubation with HPNE was plotted. BSA (1 mg/ml) was incubated with 0–10 mm HPNE in 0.1 m sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. An aliquot (0.1 ml) was then taken from the reaction mixture, and the amount of amino acids was determined by amino acid analysis as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

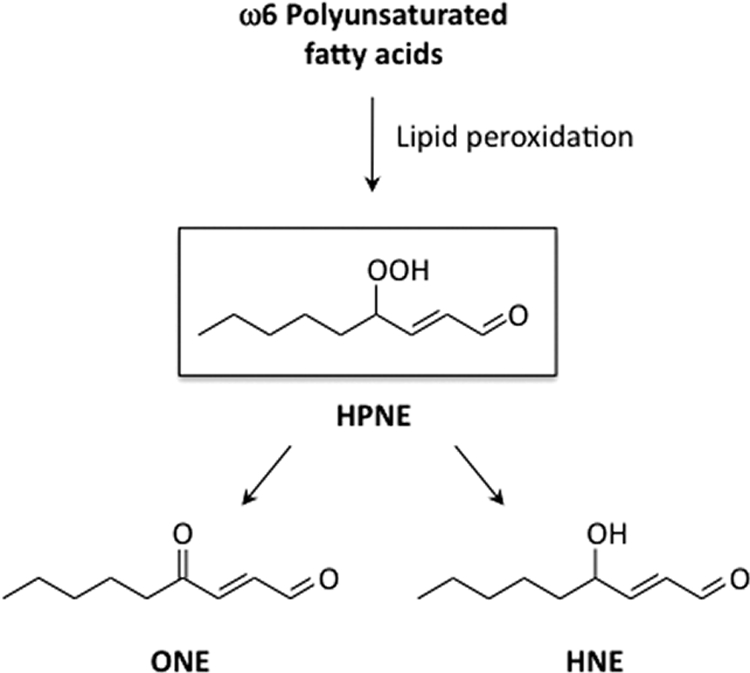

Reaction of Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine with HPNE

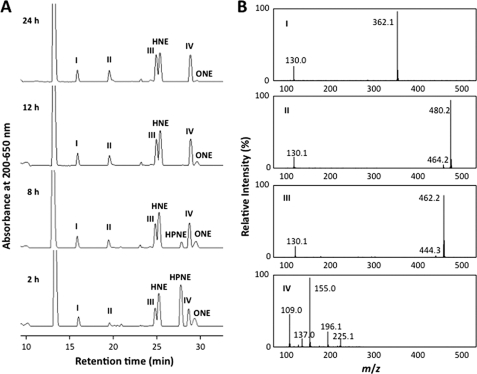

Based on the observation that the lysine residue was found to be the major target of HPNE, we sought to establish an HPNE-lysine adduction chemistry using Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine. The lysine-containing peptide (5 mm) was incubated with an equimolar concentration of HPNE (5 mm) in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). After incubation at 37 °C for 2–24 h, the reaction mixture was analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC monitored at 200–650 nm. As shown in Fig. 3A, besides the peaks corresponding to HNE and ONE, several new peaks (I, II, III, and IV) were detected. Within 2 h of incubation, the products I, II, III, and IV in addition to HPNE were detected. Subsequent incubation resulted in the disappearance of HPNE and concomitant increase of I, II, III, and IV. By 24 h, these products in addition to HNE were the major products. Molecular ion MS information for the products was collected using UPLC-ESI-MS. The mass spectrum of II showed an MH+ at m/z 480, suggesting that the product is composed of one molecule of HPNE and Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine. The mass spectrum of III exhibited an intense MH+ at m/z 462, corresponding to the dehydration from a simple HPNE-Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine monoadduct. The LC-MS analysis of I and IV gave intense MH+ signals at m/z 362 and m/z 155, respectively. The molecular mass of I suggested the addition of a small molecule (Mr 54 kDa) to the original peptide, whereas IV was likely to have originated from HPNE itself. Thus, II and III were suggested to represent the HPNE-lysine adducts.

FIGURE 3.

The reaction of Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine with HPNE. A, HPLC profiles of the reaction monitored at UV 200–650 nm. Nα-Benzoylglycyl-lysine (5 mm) was incubated with an equimolar concentration of HPNE (5 mm) in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. B, mass spectra of the products I, II, III, and IV.

Identification of HPNE-Lysine Adducts

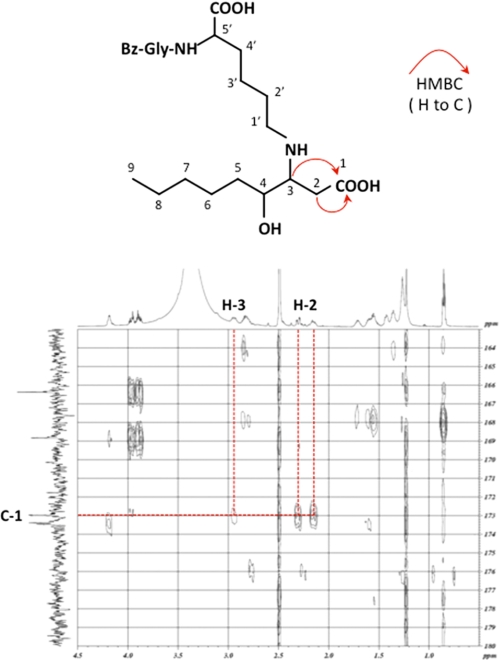

To further characterize the chemical structure of these products, isolation by HPLC on a reverse-phase column was carried out. After purification, II was characterized by mass spectrometry and by NMR (supplemental Figs. S1–S6). The high resolution ESI-MS of II showed a molecular ion peak at m/z 480.26840 (M + H)+ corresponding to the molecular formula of C24H38N3O7, which could be expected from the Michael addition to the central HPNE double bond to give the substituted 4-hydroperoxynonanal. However, neither the signals of the α,β-unsaturated linkage nor the signal of the aldehyde group of HPNE could be detected in the 1H NMR spectrum measured in DMSO-d6 (Table 1), whereas, as compared with the 13C NMR spectra between the Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine and the product, one signal at 172.9 ppm, corresponding to the carbonyl group, newly appeared in the 13C NMR spectrum of the product. The HMBC spectroscopy showed the correlations of the methine proton (2.94 ppm; H-3) with the ϵ-CH2 carbon (44.0 ppm; C-1′). The 1H-1H COSY spectrum showed correlations between the H-3 and the methine proton (3.6–3.2 ppm; H-4) and the H-3 and the methylene protons (2.15, 2.30 ppm; H-2). Unfortunately, the H-4 appeared under the large peak from H2O. To assign this signal, the 1H NMR spectrum of II was recorded in CD3CN. Although the methine proton H-4 had a cross-peak with the protons on the methylene protons (1.30–1.25 ppm, 1.45–1.40 ppm; H-5), no other cross-peaks were observed from H-2. The HMBC spectrum showed correlations of the carbonyl carbon at 172.9 ppm with two protons (H-2 and H-3), but no other correlations of protons with the carbonyl carbon (172.9 ppm) were observed (Fig. 4), indicating the presence of the carboxyl group at the C-1 position. Moreover, II has a hydroxyl group at C-4; this was supported by the chemical shift in the proton (3.44 ppm) and carbon (69.7 ppm) signals at C-4. The 1H-1H COSY spectrum showed the correlations between the methylene protons (H-5) and the methylene protons (1.28, 1.42 ppm; H-6), H-6 and the methylene protons (1.25 ppm; H-7), H-7 and the methylene protons (1.27 ppm; H-8), and H-8 and the methyl protons (0.86 ppm; H-9). Thus, the most likely structure of II was the Nα-benzoylglycyl derivative of Nϵ-4-hydroxynonanoic acid-lysine (HNA-lysine). To confirm this structure, we prepared the authentic Nα-benzoylglycyl-HNA-lysine by oxidation of the Nα-benzoylglycyl-HNE-lysine Michael adduct with NaClO2. The LC-MS analysis revealed that the product was indistinguishable from the authentic HNA-lysine adduct (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

1H and 13C NMR assignments of adduct II

| Position | δH | δC |

|---|---|---|

| ppm | ppm | |

| 1 | 172.9 | |

| 2 | 2.30 (1H, dd, J = 16.8, 4.2 Hz) | 32.7 |

| 2.15 (1H, dd, J = 16.8, 6.0 Hz) | ||

| 3 | 2.94 (1H, m) | 59.0 |

| 4 | 3.43 (1H, overlapped with solvent) | 69.7 |

| 5 | 1.44 (1H, m) | 32.9 |

| 1.27 (1H, m) | ||

| 6 | 1.42 (1H, m) | 24.4 |

| 1.28 (1H, m) | ||

| 7 | 1.25 (2H, m) | 31.1 |

| 8 | 1.27 (2H, m) | 22.0 |

| 9 | 0.86 (3H, t, J = 6.6 Hz) | 13.8 |

| 1′ | 2.81 (2H, m) | 44.0 |

| 2′ | 1.55 (2H, m) | 26.0 |

| 3′ | 1.36 (1H, m) | 22.2 |

| 1.27 (1H, m) | ||

| 4′ | 1.72 (2H, m) | 30.5 |

| 5′ | 4.18 (1H, m) | 51.7 |

FIGURE 4.

The proposed structure (top) and 1H-detected HMBC spectrum (bottom) of product II.

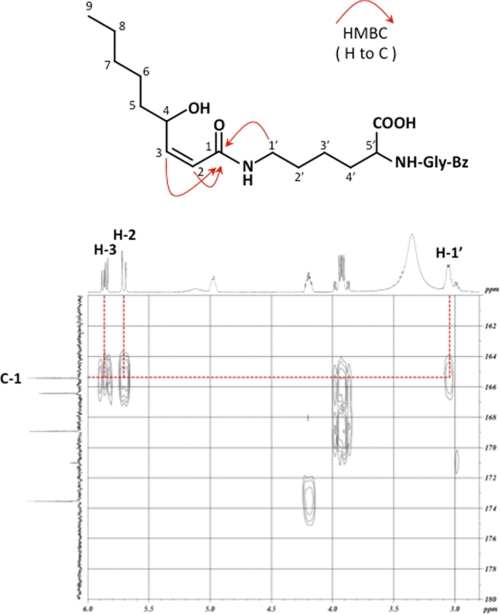

III was detected as the most prominent lysine adduct formed by HPNE (Fig. 2). To clarify the structure of III, this adduct was purified from the reaction mixture of HPNE with Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine by preparative HPLC. After purification, III was characterized by mass spectrometry and by NMR (supplemental Figs. S7–S11). The high resolution ESI-MS of III showed a molecular ion peak at m/z 462.26031 (M + H)+ corresponding to the molecular formula of C24H36N3O6. Assignment of the NMR spectra to III (Table 2) was accomplished by extensive analysis of the one- and two-dimensional spectra. The signal corresponding to the aldehyde group was not observed in the 1H NMR spectrum. The HMBC experiment showed the correlations of the ϵ-CH2 protons (H-1′) and vinylene protons (H-2 and H-3) with the carbonyl carbon (C-1) at 165.4 ppm (Fig. 5), suggesting the binding of HPNE to the ϵ-amino group via an amide bond. In addition, the coupling constant for the vinylene protons was J = 11.6 Hz for the cis proton. The signal at 0.85 ppm was assigned to the methyl protons (H-9), based on its chemical shift; it was the farthest upfield, corresponding to a saturated carbon chain terminus. It had a cross-peak with the protons on H-7 or H-8. Unfortunately, the H-7 and H-8 signals overlapped (1.45–1.18 ppm) and were coupled to each other so that they could not be readily distinguished. They in turn had a cross-peak with H-6 protons (1.45–1.18 ppm), the H-6 with the methylene protons H-5 (1.45–1.35 ppm), the H-5 with the methylene protons H-4 (4.98 ppm), and H-4 with the methine proton H-3. Moreover, III has a hydroxyl group at C-4; this was supported by the chemical shift in the proton (4.98 ppm) and carbon (66.3 ppm) signals at C-4. Based on the above data, III was identified as the 4-hydroxy-(2Z)-nonenoyl derivative of the peptide.

TABLE 2.

1H and 13C NMR assignments of adduct III

| Position | δH | δC |

|---|---|---|

| ppm | ppm | |

| 1 | 165.4 | |

| 2 | 5.70 (1H, d, J = 11.6 Hz) | 121.4 |

| 3 | 5.86 (1H, dd, J = 11.6, 7.6 Hz) | 148.1 |

| 4 | 4.98 (1H, m) | 66.3 |

| 5 | 1.45–1.18 (12H, m) | 36.7 |

| 6 | 24.5 | |

| 7 | 31.3 | |

| 8 | 22.1 | |

| 2′ | 28.6 | |

| 3′ | 22.9 | |

| 9 | 0.85 (3H, t, J = 6.8 Hz) | 13.9 |

| 1′ | 3.05 (2H, m) | 38.2 |

| 4′ | 1.71 (2H, m) | 30.9 |

| 1.59 (2H, m) | ||

| 5′ | 4.20 (1H, m) | 51.8 |

FIGURE 5.

The proposed structure (top) and 1H-detected HMBC spectrum (bottom) of product III.

Based on the mass spectrometric data, I was suggested to be an adduct composed of Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine and an HPNE-derived decomposition product with a molecular mass of 54 kDa. The UV spectrum of I exhibited λmax (ϵ) values of 228 (N-benzoyl) and 280 nm (supplemental Fig. S12). The high resolution ESI-MS of I showed a molecular ion peak at m/z 362.16847 (M + H)+, corresponding to the molecular formula of C18H24N3O5, suggesting that it was composed of one molecule of Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine and C3H2O1. The 1H and 13C NMR data determined I to be Nϵ-(2-propenal)lysine (Fig. 6 and supplemental Figs. S13–S17). The adduct has been reported to be a product of the reaction between lysine and a major lipid peroxidation product, malondialdehyde (18). It is not unlikely that HPNE during incubation with the lysine-containing peptide undergoes further peroxidation to generate this aldehyde.

FIGURE 6.

Chemical structures of products I (top) and IV (bottom).

IV was suggested to be a product derived from HPNE itself. The incubation of HPNE alone in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for 24 h at 37 °C indeed resulted in the formation of this product (data not shown). To determine the chemical structure of IV, the NMR experiments were performed. The assignment of the proton and carbon signals of adduct IV was made on the basis of the proton and carbon chemical shifts; proton-proton couplings; and 1H-1H COSY, HMQC, and HMBC correlations. The structure of IV was established as 5-pentylfuran-2H-one (Fig. 6 and supplemental Figs. S18–S22).

A Monoclonal Antibody Specific for the HPNE-Lysine Adduct

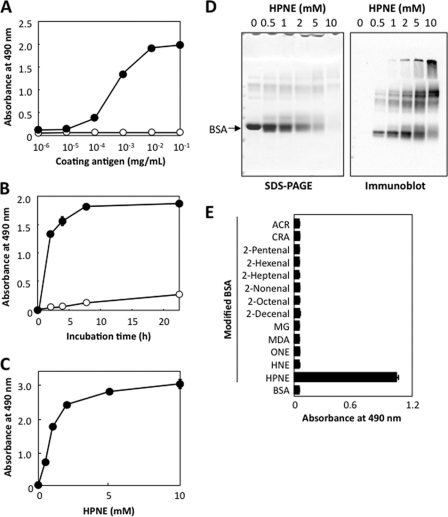

We have so far demonstrated that HPNE covalently reacts with proteins, generating specific adducts with lysine. It is known that such adducts generated on protein molecules could be an immunodominant target of antibodies. Hence, we examined if animals immunized with the HPNE-modified protein could develop an antibody specific to the HPNE-specific adducts. BALB/c mice were immunized with the HPNE-modified keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH), and, during the preparation of the monoclonal antibodies, hybridomas were selected by the reactivities of the culture supernatant to the HPNE-modified BSA. We finally obtained one clone (PM9) that exhibited the most distinctive recognition of the HPNE-modified BSA over an unmodified BSA (Fig. 7A). The ELISA and immunoblot analyses showed that, upon incubation with BSA, HPNE generated immunoreactive materials with the mAb PM9 (Fig. 7, B–D). In addition, we examined the immunoreactivity of the antibody to aldehyde-treated BSA by direct ELISA and found that, among the aldehydes tested, HPNE was the only source of immunoreactive materials generated in the protein (Fig. 7E). Notably, the antibody hardly cross-reacted with the BSA treated with the HPNE-derived products, HNE and ONE.

FIGURE 7.

Preparation of a mAb against the HPNE-modified proteins. A, the immunoreactivity of the mAb PM9 to the HPNE-treated protein was determined by a direct ELISA. A coating antigen was prepared by incubating BSA (1 mg/ml) with 1 mm HPNE in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 24 h. Open circle, native BSA; closed circle, HPNE-modified BSA. B, time-dependent formation of immunoreactive materials with the mAb PM9 upon incubation of BSA with HPNE. BSA (1 mg/ml) was incubated with 1 mm HPNE in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. C, dose-dependent formation of immunoreactive materials with the mAb PM9 upon incubation of BSA with HPNE. BSA (1 mg/ml) was incubated with HPNE (0–10 mm) in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 24 h. D, immunoblot analysis of HPNE-modified BSA. BSA (1 mg/ml) was incubated with HPNE (0–10 mm) in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 24 h. Left, SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining; right, immunoblot analysis with mAb PM9. E, the immunorectivity of the mAb PM9 to the aldehyde-treated proteins. The affinity of the mAb PM9 was determined by a direct ELISA using the aldehyde-treated proteins as the absorbed antigens. The coating antigens were prepared by incubating BSA (1 mg/ml) with 1 mm aldehydes in 1 ml of 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 24 h. Error bars, S.E.

To gain an insight into the epitope structure recognized by the mAb PM9, the immunoreactivity with the reaction products of HPNE with the amino acid derivatives, such as Nα-acetylcysteine, Nα-benzoyl-histidine, Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine, and Nα-acetylarginine, was characterized. The binding of the HPNE-modified BSA to the mAb PM9 was scarcely inhibited by the reaction mixtures of HPNE/histidine, HPNE/arginine, and HPNE/cysteine but was significantly inhibited by the reaction mixture of HPNE/lysine (supplemental Fig. S23), suggesting that the mAb PM9 might recognize an HPNE-lysine adduct as the epitope.

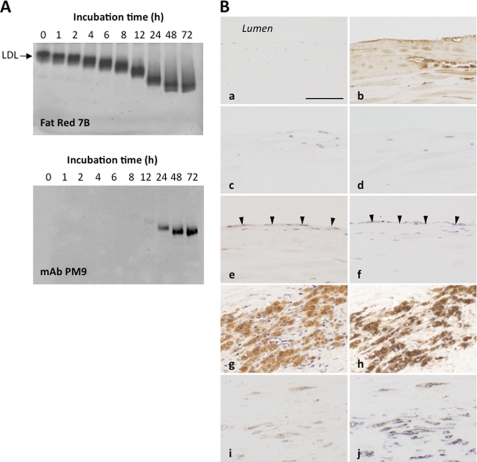

To identify the HPNE-lysine adducts recognized by the mAb PM9, the immunoreactivity with the reaction products of HPNE with Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine was characterized. As shown in Fig. 8A, the ELISA analysis of the HPLC fractions for immunoreactivity with the mAb PM9 showed that the antibody had an immunoreactivity with one fraction, including a main product HNA-lysine adduct (II) (Fig. 8B). The competitive ELISA analysis indeed showed that the purified HNA-lysine adduct inhibited the binding of the antibody to the coated antigen (HPNE-modified BSA) in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 8C). Approximately 500 pmol of HNA-lysine/well (100 μl) caused a 50% inhibition of the antibody binding to the HPNE-modified protein. Thus, the epitope recognized by the mAb PM9 was determined to be the HNA-lysine adduct.

FIGURE 8.

Isolation and structural characterization of the antigenic HPNE-lysine adduct. A, competitive ELISA analysis of the HPLC fractions for the immunoreactivity with the mAb PM9. The reaction was performed by incubating 5 mm Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine with 5 mm HPNE in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 24 h. Solid line, profile of UV absorbance at 200–650 nm. Bar, competitive ELISA analysis. The results shown are means ± S.D. (error bars) of two independent experiments. B, gross structure of the HNA-lysine adduct. C, competitive ELISA analysis with the HNA-lysine adduct. The competitors used were Nα-benzoylglycyl-HNA-lysine (closed circle) and Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine (open circle).

Immunochemical Detection of HPNE-specific Epitopes in Vitro and in Vivo

To reveal that the HPNE-specific epitopes can be formed during lipid peroxidation modification of the protein, we incubated the various polyunsaturated fatty acids with an iron/ascorbate-mediated free radical-generating system in the presence of BSA and examined their formations in the modified proteins by ELISA. As shown in supplemental Fig. S24, the formation of HPNE-specific epitopes was observed in the protein modified with the oxidized ω-6-polyunsaturated fatty acids (linoleic acid, arachidonic acid, and γ-linolenic acid) but not with the oxidized ω-3-polyunsaturated fatty acids (α-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, and docosahexaenoic acid). These results suggest the involvement of ω-6-polyunsaturated fatty acids in the formation of HPNE followed by the formation of HPNE-specific epitopes upon reaction with protein.

The formation of the HPNE-specific epitopes was also examined in the oxidized LDL in vitro. LDL treated with 10 μm Cu2+ for 0–72 h was subjected to an agarose gel electrophoresis followed by immunoblot analysis with mAb PM9. The agarose gel electrophoresis showed that the native form of the LDL appeared as a single protein band that was readily visualized by Fat Red 7B staining; however, the LDL incubated with 10 μm Cu2+ exhibited an enhanced anodic mobility compared with the native LDL (Fig. 9A, top), indicating an increased negative charge of the molecule due probably to modification of the ϵ-amino group of the lysine residues. The immunoblot analysis of the Cu2+-oxidized LDL using mAb PM9 revealed the formation of the HPNE-specific epitopes, which were not detected in the native LDL (Fig. 9A, bottom).

FIGURE 9.

Formation of the HPNE-specific epitopes in vitro and in vivo. A, formation of the HPNE-specific epitopes in the oxidized LDL. LDL (0.5 mg) was incubated with 10 μm Cu2+ in 1 ml of 50 mm phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C. Top, agarose gel electrophoresis; bottom, agarose gel electrophoresis/immunoblot analysis with the mAb PM9. B, immunohistochemical observations of sections processed with the omission of a primary mouse monoclonal antibody (a) and incubated with non-preabsorbed PM9 (b, e, g, and i), HNA-lysine-preabsorbed PM9 (c), HPNE-BSA-preabsorbed PM9 (d), and the anti-CD31 antibody (f) as well as sections double-stained with the antibodies to CD68 (h) and SMA (j). a–d, the same region in consecutive sections. e and f, the same region in consecutive sections. h and j, the same regions as those in g and i, respectively. The arrowheads indicate endothelial cells facing to the lumens. Scale bar, 100 μm (a–j). The polymer immunocomplex method was employed, using DAB (a–e, g, and i) and NiCl2-DAB (f, h, and j).

Early atherosclerosis is characterized by fatty streaks primarily composed of multiple layers of macrophage-derived foam cells surrounded by fibrously thickened intima. LDL, a key component of the fatty streak lesion of atherosclerosis, must undergo oxidative modification before it is taken up to foam cells (5, 19). Thus, the HPNE-specific epitopes are most likely accumulated in the atherosclerotic lesions. Hence, these lesions were immunohistochemically examined for HPNE-specific antigens using mAb PM9 (Fig. 9B). No immunoreactivity was detectable on sections as the negative reaction controls (Fig. 9B, a) and processed for preabsorption tests (Fig. 9B, c and d). Protein-bound HPNE immunoreactivity (Fig. 9B, b, e, g, and i) was localized in the cytoplasm of CD31-immunoreactive vascular endothelial cells (Fig. 9B, f), CD68-immunoreactive macrophages (Fig. 9B, h) and SMA-immunoreactive migrating vascular smooth muscle cells (Fig. 9B, j). Regularly arranged vascular smooth muscle cells in media were only weakly stained with PM9 and extracellular matrix of aortic wall (data not shown). Thus, the detection of the HPNE-specific epitope in the atherosclerotic plaques supports the notion that the reaction between HPNE and the primary amines might represent a process common to the LDL modification during aging and its related diseases.

DISCUSSION

During the lipid peroxidation process, the decomposition of lipid hydroperoxides leads to the generation of many reactive aldehydes, such as 2-alkenals, 4-hydroxy-2-alkenals, and ketoaldehydes. These electrophilic aldehydes show the highest reactivity with lysine residues of protein. However, there have been few detailed insights into the chemical mechanism of the derivatization of lysine residues of proteins with reactive aldehydes. This may be partly because, unlike the modification of cysteine and histidine, the modification of lysine by these aldehydes is quite diversified. HNE, for example, has been shown to form not only the Michael addition-type lysine adducts (20) but also the adducts possessing a pyrrole structure (21) and a 2-hydroxy-2-pentyl-1,2-dihydropyrrol-3-one iminium structure (22, 23). In addition, the chemical structures of the lysine-bound aldehydes, such as MDA-lysine, acrolein-lysine, crotonaldehyde-lysine, and 2-nonenal-lysine adducts, have been elucidated (4, 7). On the other hand, despite the fact that HPNE has an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde moiety, its covalent binding potential to proteins has received little attention. Because HPNE is a direct precursor of HNE and ONE (12, 13), it may be inevitable to speculate that HPNE generates the same lysine adducts as those obtained from the reaction with these end products. In the present study, based on the observation that the lysine residue in BSA was found to be the major target of HPNE, we characterized the lysine modification by HPNE in detail and established that HPNE is not just an intermediate but also a reactive molecule that could covalently modify proteins to generate unique HPNE-specific lysine adducts. Moreover, we raised an mAb against the HPNE-modified protein and identified one of the HPNE-lysine adducts as the epitope of the mAb.

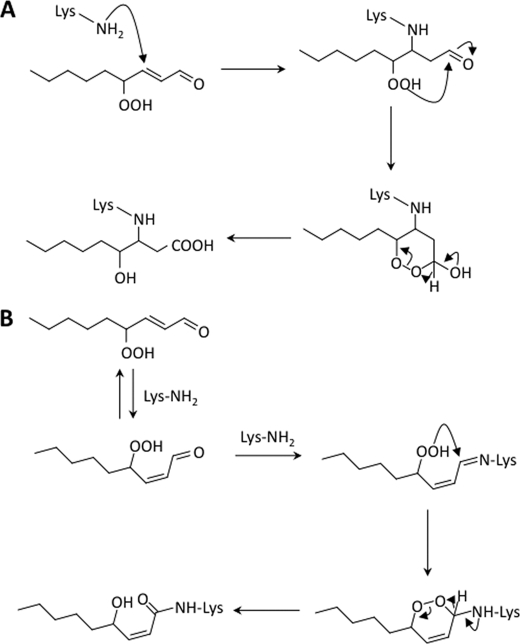

Upon incubation of Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine with HPNE in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C, we detected four products (I, II, III, and IV) in the HPLC analysis of the reaction mixture. Products II and III, among them, were found to be the HPNE-specific lysine adducts. The mass spectrum of product II showed a molecular ion peak corresponding to a product composed of one molecule of HPNE and one molecule of Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine. Therefore, we speculated that this product might simply be an HPNE-lysine Michael adduct. However, the NMR spectra apparently indicated that the product does not have an aldehyde group but has a carboxyl group. The adduct II was finally determined to be an aldehyde-oxidized product, HNA-lysine. The likely origin of this adduct is outlined in Fig. 10A. Like other α,β-unsaturated aldehydes, HPNE should be susceptible to nucleophilic addition of the lysine amino group at the double bond (C-3) to form a secondary amine derivative with retention of the aldehyde group. The C-4 hydroperoxide in this intermediate is trapped by the aldehyde group via an intramolecular Baeyer-Villiger-like reaction, which generates the corresponding cyclic peroxide derivative. The ring breaks down by migration of a hydride from a carbon to an oxygen atom, resulting in the formation of a carboxyl group. Thus, the hydroperoxide group on the C-4 carbon adjacent to an α,β-unsaturated aldehyde group plays a role in the formation of this unique HNA-lysine adduct via the six-membered ring intermediate. Due to such a unique intramolecular oxidation of the aldehyde group to the carboxyl group catalyzed by the hydroperoxide, the initial HPNE-lysine Michael adduct may not be converted to the HNE-lysine and/or ONE-lysine adducts but to the HNA-lysine adduct. Our recent study has also shown that HPNE can react by a Michael addition mechanism with the imidazole ring of histidine to generate a similar HNA-histidine adduct.3

FIGURE 10.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of HNA-lysine (II) (A) and Nϵ-4-hydroxynonenoyllysine (III) (B) adducts upon reaction of the lysine amino group with HPNE.

We also established that the reaction of the lysine derivative with HPNE generated another HPNE-specific lysine adduct, 4-hydroxy-(2Z)-nonenoyl-lysine (III). Formation of this type of adduct possessing an amide structure is not without precedent. Zhu and Sayre (24) have previously identified a novel 4-ketoamide-type ONE-lysine adduct, Nϵ-(4-oxononanoyl)lysine, that arises from a reversibly formed ONE-lysine Schiff base. We have also reported the formation of similar amide-type adducts upon reaction of the lysine derivative with n-alkanals in the presence of H2O2 or alkyl hydroperoxides (25). Therefore, we hypothesized that HNE generated from HPNE might be involved in the formation of this product. However, the same adduct was not detected when the lysine derivative was incubated with HNE in the presence of H2O2 (data not shown). Fig. 10B depicts a proposed mechanism for the formation of 4-hydroxy-(2Z)-nonenoyl-lysine. HPNE initially forms a Schiff base derivative. The hydroperoxy group of the Schiff base adduct then reacts with the imine carbon to generate an endoperoxide followed by hydride migration to form the 4-hydroxy-(2Z)-nonenoyl-lysine. Formation of this adduct requires an isomerization of the double bond of HPNE from trans to cis, which may be most easily understood in terms of addition-elimination of the amines in the system to the double bond of HPNE (21, 26).

In addition to these HPNE-specific lysine adducts, we identified Nϵ-(2-propenal)lysine (product I) as one of the HPNE-lysine reaction products. This adduct is not HPNE-specific because the same adduct has been reported to be formed upon reaction of lysine with MDA (27). It is likely that HPNE in the presence of the lysine derivative is first converted to the free MDA, which then reacts with the ϵ-amino group of lysine to generate Nϵ-(2-propenal)lysine. The mechanism for the formation of MDA from HPNE is unknown; however, the 4-hydroperoxy group may be involved in the oxidative cleavage of the C3-C4 linkage in HPNE. We have previously shown that, using an antibody against Nϵ-(2-propenal)lysine, the adduct represents one of the major constituents of the in vitro oxidized LDL (18). We also identified 5-pentylfuran-2H-one (product IV) as the product. Incubation of HPNE alone indeed generated the same product, suggesting the spontaneous conversion of HPNE to the product. It is of interest to note that this product was previously detected in the water-mediated oxidative decomposition of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes (28).

On the other hand, using the HPNE-modified KLH as the immunogen, we successfully raised the mAb PM9 specific to the HPNE-modified proteins. Of note, the antibody hardly reacted with the proteins treated with the HPNE analogs, such as HNE and ONE. The mAb PM9 was found to be capable of detecting antigenic structures generated in the oxidized LDL in vitro. Furthermore, the detection of the HPNE-specific epitopes was attempted in the tissue samples from the patients with atherosclerosis, which is considered to be a form of chronic inflammation resulting from the interaction between the modified lipoproteins, monocyte-derived macrophages, T cells, and the normal cellular elements of the arterial wall. We confirmed that atheromatous lesions indeed contained the protein-bound HPNE, mainly colocalizing with foamy macrophages. The result is consistent with the view (5, 19) that protein alterations, including oxidative modification, predispose LDL to clearance by scavenger receptors of the macrophages, intracellular deposits of lipoprotein-derived cholesterol, and the formation of foam cells. Therefore, HPNE may play a role in the formation of the arterial foam cells and contribute to the development of atherosclerosis. Additional studies will be needed to establish a direct connection between the HPNE modification of proteins and their atherogenic properties.

Finally, based on the observations that the binding of the HPNE-modified BSA to mAb PM9 was significantly inhibited by the reaction mixture of HPNE/lysine, we characterized the immunoreactivity of the antibody with the reaction products of HPNE with Nα-benzoylglycyl-lysine and identified the HNA-lysine adduct (II) as the HPNE-specific epitope. The preferential recognition of the antibody to HNA-lysine is probably explained by the structural characteristics in the side chain of the adduct. In contrast to 4-hydroxy-(2Z)-nonenoyl-lysine (III), HNA-lysine contains a more negative charge on the side chain, which may represent an important immunological epitope. Indeed, a monoclonal antibody against the glyoxal-modified proteins recognized a similar adduct with the carboxyl group as the major epitope (29). On the other hand, relatively high concentrations of the inhibitor (HNA-lysine) were required for the antibody binding to the HPNE-modified protein (Fig. 8C). This may be due to the higher affinity of the antibody with the coating antigen (HPNE-modified protein) than with the HNA-lysine adduct used as a competitor. In general, the sensitivity of the competitive ELISA depends on relative affinities of antibody both for the coating antigen and the competitor (low molecular weight adduct) in the solution. Thus, to utilize the mAb PM9 for quantitative evaluation of the HNA-lysine adducts, further improvements, such as antibody labeling and preparation of adequate antigen, may be required.

In summary, we characterized the reaction of the protein with HPNE and identified the structures of the novel HPNE-specific lysine adducts, HNA-lysine and 4-hydroxy-(2Z)-nonenoyl-lysine. It was speculated that both adducts might be formed through an intramolecular Baeyer-Villiger-like reaction catalyzed by the hydroperoxy group. These findings and a previous report that HPNE reacts with deoxyguanosine to generate etheno-DNA adduct (30) suggest that HPNE is not just an intermediate but also a reactive aldehyde that covalently modifies proteins and DNA. We also demonstrated that HNA-lysine constitutes an epitope of the mAb specific to the HPNE-modified proteins. Using immunochemical techniques, we showed that the HPNE-specific epitopes were formed in the lipid peroxidation-modified proteins and in the Cu2+-oxidized LDL in vitro. These data suggest the usefulness of this antibody for further investigations aimed at elucidation of the relative contribution of HPNE to the accumulation of oxidatively modified proteins in vivo. We indeed observed that the HPNE-specific epitopes were accumulated in the atherosclerotic lesions. Because lipid peroxidation and subsequent modification of proteins are known to be involved in widespread biological processes, HPNE may contribute to the modification of biomolecules and the development of tissue damage under oxidative stress. Additional studies should provide an insight into the biological significance of HPNE that could be ubiquitously generated in biological systems.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Research in a Proposed Research Area), Japan (to K. U.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S24.

Y. Shimozu, K. Hirano, and K. Uchida, unpublished data.

- HNE

- 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- COSY

- correlation spectroscopy

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- HMBC

- heteronuclear multiple bond correlation

- HMQC

- heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation

- HPNE

- 4-hydroperoxy-2-nonenal

- MDA

- malondialdehyde

- ONE

- 4-oxo-2-nonenal

- SMA

- α-smooth muscle actin

- ONE

- 4-oxo-2-nonenal

- DAB

- 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride.

REFERENCES

- 1. Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. (1989) Free Radicals in Biology and Medicine, 2nd Ed., Clarendon Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 2. Esterbauer H., Schaur R. J., Zollner H. (1991) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 11, 81–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stadtman E. R. (1992) Science 257, 1220–1224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Uchida K. (2000) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 28, 1685–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Steinberg D., Parthasarathy S., Carew T. E., Khoo J. C., Witztum J. L. (1989) N. Engl. J. Med. 320, 915–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steinberg D. (1995) Lancet 346, 36–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Uchida K. (2003) Prog. Lipid Res. 42, 318–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gardner H. W., Hamberg M. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 6971–6977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schneider C., Tallman K. A., Porter N. A., Brash A. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20831–20838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schneider C., Boeglin W. E., Yin H., Ste D. F., Hachey D. L., Porter N. A., Brash A. R. (2005) Lipids 40, 1155–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schneider C., Porter N. A., Brash A. R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 15539–15543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lee S. H., Blair I. A. (2000) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 13, 698–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lee S. H., Oe T., Blair I. A. (2001) Science 292, 2083–2086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rindgen D., Nakajima M., Wehrli S., Xu K., Blair I. A. (1999) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 12, 1195–1204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tijet N., Schneider C., Muller B. L., Brash A. R. (2001) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 386, 281–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. West J. D., Ji C., Duncan S. T., Amarnath V., Schneider C., Rizzo C. J., Brash A. R., Marnett L. J. (2004) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 17, 453–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Uchida K., Sakai K., Itakura K., Osawa T., Toyokuni S. (1997) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 346, 45–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Glass C. K., Witztum J. L. (2001) Cell 104, 503–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Szweda L. I., Uchida K., Tsai L., Stadtman E. R. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 3342–3347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sayre L. M., Arora P. K., Iyer R. S., Salomon R. G. (1993) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 6, 19–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Itakura K., Osawa T., Uchida K. (1998) J. Org. Chem. 63, 185–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Xu G., Sayre L. M. (1998) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 11, 247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhu X., Sayre L. M. (2007) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 20, 165–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ishino K., Wakita C., Shibata T., Toyokuni S., Machida S., Matsuda S., Matsuda T., Uchida K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15302–15313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Patai S., Rappoport Z. (1964) in The Chemistry of Alkenes (Patai S. ed) pp. 565–573, Wiley-Interscience, London [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chio K. S., Tappel A. L. (1969) Biochemistry 8, 2821–2826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Grein B., Huffer M., Scheller G., Schreier P. (1993) J. Agric. Food Chem. 41, 2385–2390 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Reddy S., Bichler J., Wells-Knecht K. J., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 10872–10878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lee S. H., Arora J. A., Oe T., Blair I. A. (2005) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 18, 780–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.