Abstract

TNNC1, which encodes cardiac troponin C (cTnC), remains elusive as a dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) gene. Here, we report the clinical, genetic, and functional characterization of four TNNC1 rare variants (Y5H, M103I, D145E, and I148V), all previously reported by us in association with DCM (Hershberger, R. E., Norton, N., Morales, A., Li, D., Siegfried, J. D., and Gonzalez-Quintana, J. (2010) Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 155–161); in the previous study, two variants (Y5H and D145E) were identified in subjects who also carried MYH7 and MYBPC3 rare variants, respectively. Functional studies using the recombinant human mutant cTnC proteins reconstituted into porcine papillary skinned fibers showed decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of force development (Y5H and M103I). Furthermore, the cTnC mutants diminished (Y5H and I148V) or abolished (M103I) the effects of PKA phosphorylation on Ca2+ sensitivity. Only M103I decreased the troponin activation properties of the actomyosin ATPase when Ca2+ was present. CD spectroscopic studies of apo (absence of divalent cations)-, Mg2+-, and Ca2+/Mg2+-bound states indicated that all of the cTnC mutants (except I148V in the Ca2+/Mg2+ condition) decreased the α-helical content. These results suggest that each mutation alters the function/ability of the myofilament to bind Ca2+ as a result of modifications in cTnC structure. One variant (D145E) that was previously reported in association with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and that produced results in vivo in this study consistent with prior hypertrophic cardiomyopathy functional studies was found associated with the MYBPC3 P910T rare variant, likely contributing to the observed DCM phenotype. We conclude that these rare variants alter the regulation of contraction in some way, and the combined clinical, molecular, genetic, and functional data reinforce the importance of TNNC1 rare variants in the pathogenesis of DCM.

Keywords: Cardiac Muscle, Cardiomyopathy, Genetic Diseases, Protein Structure, Troponin, Actomyosin ATPase, Circular Dichroism, Dilated Cardiomyopathy, Skinned Fibers, Troponin C

Introduction

The dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)3 phenotype is manifested by a decrease in left ventricular contractility, ventricular wall thinning, and dilation of the ventricular chamber, all of which lead to a reduction in the ejection fraction (1). Adverse consequences of DCM include heart failure, arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac death (2). Although DCM can be caused by a variety of factors, genetic predisposition remains an important cause (3). Continued efforts are necessary to discover the heritable causes of DCM in patients and, when identified, substantiate their significance with relevant functional studies (3).

DCM-causing mutations have been found in several sarcomeric proteins, but only a few have been identified in TNNC1, which encodes cardiac troponin C (cTnC), a Ca2+ sensor and key regulator of contraction (4). TnC plays an important role in excitation-contraction coupling and is the primary target of compounds such as levosimendan that augment Ca2+ responsiveness of the thin filament (5). Functionally, DCM troponin mutations manifest distinctively as decreased Ca2+ sensitivity, reduced thin filament Ca2+ affinity, and decreased in vitro cross-bridge cycling rate (4). The first DCM-causing mutation identified in TNNC1, G159D, was found in three families (6, 7). In functional studies, G159D showed little-to-no decrease in myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity (8–10) but an ablated response to PKA phosphorylation (9). It is known that cardiac β-adrenergic stimulation activates PKA in the myocardium, and phosphorylation of its targets in the myofilament leads to its decreased Ca2+ sensitivity (11–13). Structural studies have elucidated the molecular impact of the G159D mutation. By NMR spectroscopy, it was determined that the C-terminal domain of cTnC containing the G159D mutation has lower affinity for the cTnI-(37–71) peptide (14). In addition, the combinatory purported mutations E59D and D75Y were identified in a patient with idiopathic DCM, and functional characterization also suggested their potential relevance (15, 16).

Knock-out of cTnC in adult zebrafish using an inducible antisense strategy confirmed that the loss of TnC function leads to a phenotype consistent with DCM (17). Another recent human study identified a mutation in TNNC1 that segregated with familial DCM (including a member with peripartum cardiomyopathy), adding to the genetic evidence of this disease (18). In this study, we present clinical, pedigree, and functional studies of the Y5H, M103I, D145E (this mutation was previously studied as a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)-linked mutation), and cTnC I148V genetic variants in human DCM and show that two of these novel rare variants manifested functional properties typical of DCM (decreased Ca2+ sensitivity), accompanied by altered responsiveness to PKA phosphorylation in all the mutants.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Patient Population

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects, and the Institutional Review Boards of the Oregon Health & Science University and the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine approved the project. The study was a subset of a previous publication (19) that used methods of clinical categorization of subjects with DCM as described previously (19–21).

Genetic Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood and sequenced in both directions to detect nucleotide variants in TNNC1 (cTnC) as previously described (19, 21). All exons and intron/exon boundaries were PCR-amplified by standard methods at SeattleSNPs. Samples from probands identified by the resequencing service as carriers of protein-altering variants, as well as any available samples from their relatives, were resequenced in our laboratory for confirmation and segregation analysis. Nucleotide changes were evaluated only if they were absent in all 246 control samples analyzed at the resequencing center (186 white, 23 Yoruban, 19 Asian, and 18 Hispanic) as reported previously (19, 21).

Functional and Structural Studies

Recombinant Proteins

The recombinant TnC mutants Y5H, M103I, D145E, and I148V were cloned as previously described (22). Prior to expression and purification, all subcloned DNAs were sequenced to verify that the sequences were correct. Escherichia coli-derived BL21-CodonPlus(DE3) cells were transformed with pET-3d constructs containing human cTnC. The WT and mutant proteins were overexpressed and purified as described previously (22).

Fiber Preparation and Ca2+ Dependence of Force Development Measurements

Fresh cardiac tissue was obtained from slaughterhouse pigs. Strips of papillary were isolated from the left ventricle and skinned overnight (22). Briefly, a skinned fiber bundle ∼75–100 μm in diameter was mounted using stainless steel clips to a force transducer and then immersed in a pCa 8.0 relaxation solution as described (22). Native cTnC was depleted upon incubation of the fiber in 5 mm CDTA and 25 mm Tris (pH 8.4) for ∼1.5 h. Fibers were then incubated with 55 μm mutant or WT cTnC diluted in pCa 8.0 solution for 1 h (22). For the PKA experiments, after TnC reconstitution, the fibers were incubated with 500 units/ml PKA catalytic subunit (Sigma P2645) for 30 min under relaxing conditions. The Ca2+ dependence of force development was tested in the skinned fibers in various Ca2+ solutions. The following equation was used to analyze the data: % change in force = 100 × [Ca2+]n/([Ca2+]n + [Ca2+50]n), where [Ca2+50] is the free [Ca2+] that produces 50% force and n is the Hill coefficient.

Activation and Inhibition of the Actin-Tropomyosin-activated Myosin ATPase

Human cTnT and cTnI were overexpressed and purified as described (23). To form the troponin complexes, the individual troponin subunits were first dialyzed against 3 m urea, 1 m KCl, 10 mm MOPS, 1 mm DTT, and 0.1 mm phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and then twice against the same buffer excluding urea. The troponin subunits were mixed in a 1.3:1.3:1 TnT/TnI/TnC molar ratio. Then, the complexes were successively dialyzed against decreasing concentrations of KCl (0.7, 0.5, 0.3, 0.1, 0.05, and 0.025 m). The troponin complexes were centrifuged to remove any precipitated TnT and TnI. Prior to storage of the troponin complexes at −80 °C, SDS-PAGE was performed to determine the stoichiometry of the troponin subunits. Additional proteins utilized in this assay included porcine cardiac myosin, rabbit skeletal F-actin, and porcine cardiac tropomyosin (Tm), which were prepared as described previously (24). The protein concentrations utilized for actomyosin ATPase assays were as follows: 0.6 μm porcine cardiac myosin, 3.5 μm rabbit skeletal F-actin, 1 μm porcine cardiac Tm, and 0–2 μm preformed Tn complexes (described above). The ATPase inhibitory assay was performed using a 0.1-ml reaction mixture consisting of 3.4 mm MgCl2, 0.13 μm CaCl2, 1.5 mm EGTA, 3.5 mm ATP, 1 mm DTT, and 11.5 mm MOPS (pH 7.0) at 25 °C. The ATPase activation assay used the same 0.1-ml buffer mixture but with adjustments for 3.3 mm MgCl2 and 1.7 mm CaCl2. The reaction was initiated by the addition of ATP, and activity was quenched after 20 min with trichloroacetic acid to a final concentration of 35%. The precipitated assay proteins were removed by centrifugation, and the supernatant was analyzed according to the method of Fiske and SubbaRow (25) to determine the concentration of inorganic phosphate released by ATP hydrolysis.

Circular Dichroism Measurements

Far-UV CD spectra were collected using a 1-mm path length quartz cell in a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter with a bandwidth of 1 nm at a speed of 50 nm/min at room temperature (23). The mean residue ellipticity ([θ]MRE in degrees·cm2·dmol−1) for the spectra was calculated with Jasco software using the following equation: [θ]MRE = [θ]/(10 × Cr × l), where [θ] is the measured ellipticity in millidegrees, Cr is the mean residue molar concentration, and l is the path length in centimeters. For all single experiments, 10 scans were collected and averaged without numerical smoothing, and the optical activity of the buffer was subtracted from relevant protein spectra. The experimental protein concentration for the WT and mutants was determined to be 0.2 mg/ml by the biuret reaction using bovine serum albumin as a standard. The CD experiments were performed under three different conditions: for apo, 1 mm EGTA, 20 mm MOPS, and 100 mm KCl (pH 7.0); for Mg2+, 1 mm EGTA, 20 mm MOPS, 100 mm KCl, and 2.075 mm MgCl2 (pH 7.0); and for Ca2+/Mg2+, 1 mm EGTA, 20 mm MOPS, 100 mm KCl, 2.075 mm MgCl2, and 1.096 mm CaCl2 (pH 7.0).

Statistical Analysis

The experimental results are reported as mean ± S.E. and were analyzed for significance using Student's t test at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Molecular Genetic Data

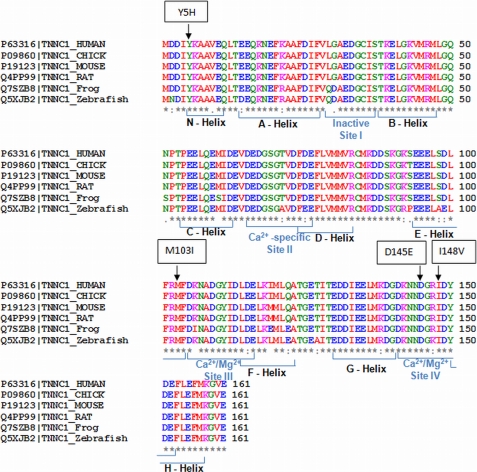

The TNNC1 rare variants identified are shown in Table 1, and each was conserved among species (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Non-synonymous mutations in TNNC1 (cTnC)

| Pedigree | Molecular genetic data |

Clinical and pedigree data |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCSC hg18 coordinates | Nucleotide changea | Amino acid change | Diagnosis, FDCb or IDC | Race | Disease-associated status in our prior report (19) | Phenotype of variant reported previously (22) | |

| A | chr3:52463059 | 2040T→C | Y5H | IDC | Caucasian | Possibly | |

| B | chr3:52460808 | 4291G→A | M103I | FDC | Caucasian | Likely | |

| C | chr3:52460466 | 4633C→A | D145E | IDC | Caucasian | Possibly | HCM |

| D | chr3:52460459 | 4640A→G | I148V | FDC | Caucasian | Possibly | |

a Nucleotide numbering is per the SeattleSNPs resequencing service (gi:302313132).

b FDC, familial DMC; IDC, idiopathic DCM.

FIGURE 1.

TNNC1 (cTnC) gene structure and amino acid conservation resulting from the identified rare variants. The TNNC1 gene shows a remarkable degree of conservation between mammalian, avian, amphibian, and fish species. Altered amino acids are indicated for each missense mutation in a box above the first line, and the human wild-type sequence is shown in the first line, followed by chicken, mouse, rat, frog, and zebrafish sequences. All variants were conserved throughout these various species. Information concerning the helices and sites can be found under UniProt accession number P63316.

Clinical Data

Clinical assignments for each subject available for analysis and their family pedigrees are provided in Fig. 2 and Tables 1 and 2 according to the TNNC1 rare variant identified. None of these variants were seen in control DNAs (246 DNAs, 492 chromosomes) in our initial report, providing support that these were rare variants (19). This conclusion is supported by a prior TNNC1 study in HCM that sequenced 500 control DNAs (1000 control chromosomes) where only one synonymous variant was identified (22), suggesting that the cTnC protein is highly conserved.

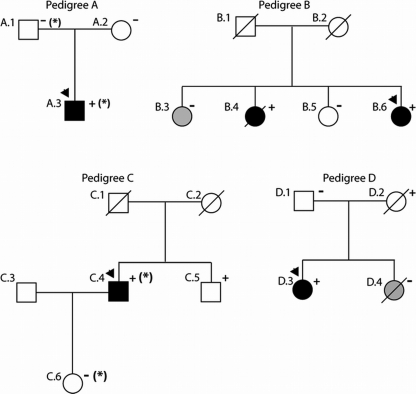

FIGURE 2.

Pedigrees of cTnC-associated DCM. Pedigrees have been labeled by letters, which correspond to their respective mutation as shown in Fig. 1 and are given in Tables 1 and 2. Squares represent males, and circles represent females. Arrowheads denote the probands. Diagonal line mark deceased individuals. Solid symbols indicate DCM with or without heart failure; shaded symbols represent any cardiovascular abnormality; and open symbols represent unaffected individuals. The presence or absence of the family's TNNC1 rare variant is indicated by + or −, respectively. Obligate carriers are noted in parentheses (+). The asterisk in Pedigree A denotes an MYH7 R1045C rare variant and that in Pedigree C denotes an MYBPC3 P910T rare variant thought to be possibly disease-causing as reported previously (19).

TABLE 2.

Clinical characteristics

| Subject | Age of diagnosis or screening | DCM | LVEDD (Z-score)a | LV septum, posterior wall thickness | Ejection fraction | ECG/arrhythmia | TNNC1 mutation present? | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| years | mm | mm | % | |||||

| Pedigree A: Y5H | ||||||||

| A.1 | NA | Unk | NA | NA | NA | NA | No | Asymptomatic at 51 years, no clinical screening data |

| A.2 | 47 | No | 43 (−0.86) | 7, 7 | 65 | Unusual P axis, possible ectopic atrial rhythm | No | |

| A.3 | 2 weeks | Yes | 72 (5.71) | 5, 9 | 24 | NSR, biatrial enlargement, possible RVH | Yes | Echo data at age 15 years, heart transplant at 15 years, also has MYH7 R1045C rare variant |

| Pedigree B: M103I | ||||||||

| B.3 | 40 | No | 56 (3.11) | 9, 9 | 60 | 1st degree AVB, SVT, ICD | No | LVE, syncope, palpitations, ICD age 41 |

| B.4 | 39 | Yes | 59 (3.47) | 11, 12 | 43 | NSR, LAE, septal MI | Yes | |

| B.5 | 47 | No | 46 (−0.084) | 7, 8 | 65 | Sinus bradycardia, PVCs, QT prolongation | No | PM at age 47 |

| B.6 | 47 | Yes | 60 (3.96) | 10, 9 | 42 | AF, RVR, LVH, PVCs, LAD, anterolateral infarction, long QT | Yes | ICD and PM after cardiac arrest at age 49 |

| Pedigree C: D145E | ||||||||

| C.4 | 60 | Yes | 73 | 11, 12 | 10 | LBBB, 1st degree AVB | Yes | Also has MYBPC3 P910T rare variant |

| C.5 | 63 | No | 51 (−0.01) | 11, 10 | 65 | NSR, frequent PVCs, trigeminy | Yes | |

| C.6 | 38 | No | 40 (−2.44) | 7, 8 | 65 | NSR | No | Has MYBPC3 P910T rare variant |

| Pedigree D: I148V | ||||||||

| D.1 | NA | Unk | NA | NA | NA | NSR, RBBB, LVH, inferior MI pattern | No | No cardiovascular data except ECG available at age 70 |

| D.2 | NA | Unk | NA | NA | NA | NSR, LBBB, LVH | Yes | Coronary artery disease by angiogram at age 69, ECG at age 69 |

| D.3 | 40 | Yes | 56 (3.40) | 8, 10 | 30 | NSR, LBBB | Yes | |

| D.4 | 40 | Unk | 49 (1.49) | 8, 8 | 62 | NA | No | Normal echo at age 40, died in sleep at age 50, autopsy (LVH) |

a LVEDD, left ventricular end-diastolic dimension; LV, left ventricular; ECG, electrocardiogram; NA, data not available; Unk, unknown; NSR, normal sinus rhythm; RVH, right ventricular hypertrophy; echo, echocardiogram; 1st degree AVB, first degree atrioventricular block; SVT, supraventricular tachycardia; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; LVE, left ventricular end; LAE, left atrial enlargement; MI, myocardial infarction; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; PM, pacemaker; AF, atrial fibrillation; RVR, rapid ventricular response; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; LAD, left axis deviation; LBBB, left bundle branch block; RBBB, right bundle branch block.

Pedigree A

The proband in Pedigree A (A.3) was hospitalized with heart failure at 2 weeks of age and was diagnosed with congenital DCM. He received medical therapy but later developed heart failure at age 14 and received a heart transplant at age 15. Two missense variants (TNNC1 Y5H and MYH7 R1045C) not seen in 246 controls and 253 controls, respectively, were detected in the proband (19, 21). His mother, who was clinically unaffected (negative echocardiogram and electrocardiogram at age 47), was negative for both variants. His father was positive for the MYH7 R1045C variant and negative for the TNNC1 Y5H variant. Thus, this TNNC1 variant is likely a de novo mutation or results from germ line mosaicism in one of his parents. Clinical data are not available on this subject's father, although by patient report, he is asymptomatic with no history of heart disease, and he is currently 51 years old. No other clinical or genetic data are available for this family.

Pedigree B

The proband in Pedigree B (B.6) carried an M103I alteration in TNNC1, which segregated with disease in a sister (B.4) who was diagnosed with DCM at age 39 and died at age 48 of non-cardiac causes. The variant was absent in the two other sisters (B.3 and B.5). The proband (B.6) and her two unaffected sisters (B.3 and B.5) all have a history of conduction system disease and/or syncopal episodes, as well as a long QT interval.

Pedigree C

The proband in Pedigree C (C.4) (Fig. 2 and Table 2) was found to carry two missense variants (TNNC1 D145E and MYBPC3 P910T). The TNNC1 variant was previously reported in a proband with familial HCM (22) who presented at age 57 with chest pain and dyspnea, with a maximal left ventricular wall thickness of 22 mm and a left ventricular outflow tract obstruction of 100 mm Hg; several other family members were affected with HCM. The proband in Pedigree C (C.4) had DCM without any evidence of an HCM phenotype (Table 2). A brother of the proband (Pedigree C; not shown) (Fig. 2) was reported by family history to have HCM; however, no medical records or genetic analysis is available for this family member to assess segregation of either variant with cardiomyopathy. Another brother (C.5) who had normal cardiac screening at age 63 without evidence of cardiomyopathy was found to carry the TNNC1 variant only. The proband's daughter (C.6) (Fig. 2) carries only the MYBPC3 variant seen in the proband and had normal cardiac screening at age 38.

Pedigree D

The TNNC1 I148V nucleotide alteration in the proband of Pedigree D (D.3) (Fig. 2) is potentially disease-causing (Table 2), as it predicted the replacement of a conserved amino acid; however, no additional pedigree information was available to assess segregation with disease. A sister (D.4) died in her sleep at age 50 and was found to have left ventricular hypertrophy on autopsy; this individual did not carry the I148V TNNC1 variant. The variant was inherited from the proband's mother, who died at age 74 with a history of a left bundle branch block as determined by an electrocardiogram at age 69 and coronary artery disease, but echocardiographic data and any further medical information are not available.

Skinned Cardiac Fibers

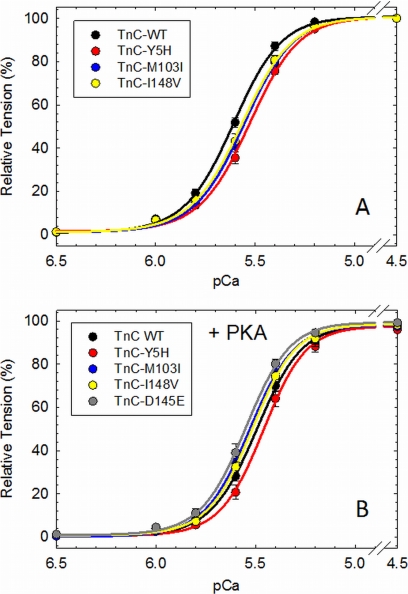

Skinned fibers reconstituted with cTnC mutants Y5H (pCa50 = 5.532 ± 0.012) and M103I (pCa50 = 5.548 ± 0.013) showed a statistically significant decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity of force development compared with WT cTnC (pCa50 = 5.613 ± 0.012) (Fig. 3A and Table 3). However, fibers reconstituted with I148V (pCa50 = 5.573 ± 0.016) did not show a significant decrease in the Ca2+ sensitivity compared with WT cTnC (Fig. 3A and Table 3). We previously reported the Ca2+ sensitivity of force for skinned fibers reconstituted with D145E (22). In contrast to the other cTnC mutants, D145E (pCa50 = 5.898 ± 0.008) displayed a leftward shift in the Ca2+ sensitivity compared with WT cTnC (Table 3). The Hill coefficient (nH), which is an index of the cooperative activation of the myofilament, was not affected in any way by the incorporation of cTnC mutants (Table 3). It has been well established that PKA phosphorylation of cardiac myofilament proteins decreases their Ca2+ sensitivity of force and increases relaxation of cardiac muscle (13). Skinned fibers reconstituted with the cTnC mutants and incubated with PKA showed a reduced (Y5H and I148V) or abolished (M103I) effect of PKA phosphorylation on myofilament Ca2+ desensitization compared with WT cTnC (Fig. 3B and Table 3). The ΔpCa50 (pCa50 PKA-treated − pCa50 PKA-untreated) values for WT cTnC and mutants Y5H, M103I, and I148V were −0.117, −0.071, −0.018, and −0.054, respectively (Table 3). In contrast, D145E displayed an extensive Ca2+ desensitization upon PKA phosphorylation (ΔpCa50 = −0.343). The cTnC mutants did not affect the maximal force recovery in the presence or absence of PKA compared with WT cTnC (except for D145E in the absence of PKA (Fig. 3B and Table 3) as shown previously (22)).

FIGURE 3.

pCa-force relationship measured in porcine skinned papillary fiber containing DCM TnC mutants. Native porcine TnC was extracted, and the skinned fibers were reconstituted with WT TnC or the DCM mutant. The Ca2+ sensitivity of force development was measured at pH 7.0 before (A) and after (B) PKA treatment. The fiber data are summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Summary of calcium-force relationship curves of TnC-extracted porcine papillary fibers reconstituted with WT TnC or DCM mutants

The pCa50, nH, percent maximal force, and percent Ca2+ unregulated force values are the average of a number of independent fiber experiments, and the errors are reported as S.E. values.

| TnC | pCa50 | Hill coefficient (nH) | ΔpCa50a | ΔpCa50b | Maximal force recovery | No. of experiments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | ||||||

| WT | 5.613 ± 0.012 | 3.678 ± 0.150 | 54.91 ± 2.34 | 12 | ||

| Y5H | 5.532 ± 0.012c | 3.747 ± 0.231 | −0.081 | 53.04 ± 1.94 | 15 | |

| M103I | 5.548 ± 0.013c | 3.705 ± 0.179 | −0.065 | 49.28 ± 2.83 | 13 | |

| I148V | 5.573 ± 0.016 | 3.728 ± 0.243 | −0.040 | 54.97 ± 2.56 | 12 | |

| D145Ed | 5.898 ± 0.008c | - | +0.285 | 70.30 ± 1.40c | 8 | |

| WT + PKA | 5.496 ± 0.013e | 3.988 ± 0.261 | −0.117 | 54.39 ± 2.65 | 11 | |

| Y5H + PKA | 5.461 ± 0.018e | 4.269 ± 0.242 | −0.035 | −0.071 | 55.41 ± 1.64 | 12 |

| M103I + PKA | 5.530 ± 0.017 | 3.946 ± 0.220 | +0.034 | −0.018 | 53.74 ± 2.41 | 12 |

| I148V + PKA | 5.519 ± 0.012e | 4.142 ± 0.269 | +0.023 | −0.054 | 55.62 ± 2.37 | 11 |

| D145E + PKA | 5.555 ± 0.017c,e | 4.359 ± 0.249 | +0.059 | −0.343 | 47.36 ± 2.66 | 14 |

a ΔpCa50 = DCM TnC mutant pCa50 − WT TnC pCa50 (under the same conditions).

b ΔpCa50 = TnC pCa50 with PKA − TnC pCa50 without PKA.

c p < 0.05; the DCM TnC mutant is significantly different from WT TnC (under the same conditions).

d Values were obtained from a previous report (22).

e p < 0.05; WT TnC or DCM mutant in the presence of PKA was significantly different from the same TnC (WT or DCM mutant) without PKA.

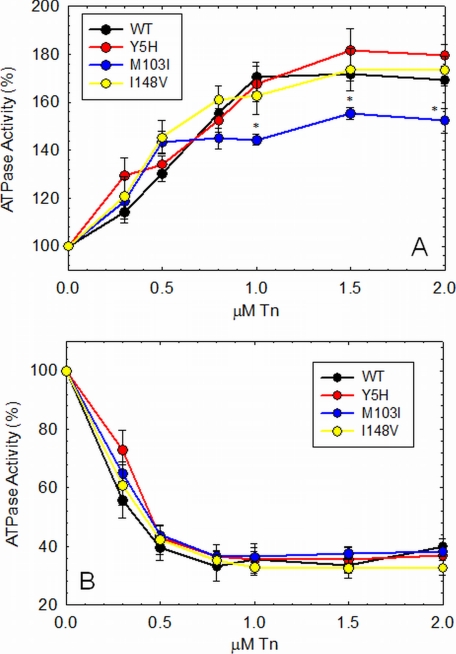

Actomyosin-Tm-Tn ATPase Activity

We measured the ability of the mutant cTn complexes to activate (in the presence of Ca2+) and inhibit (in the absence of Ca2+) the actomyosin-Tm ATPase activity. cTn containing the M103I mutation was the only complex that was not able to fully activate the actomyosin-Tm ATPase activity compared with WT cTn (Fig. 4A). Inhibition of the actomyosin-Tm ATPase activity was not affected by any of the cTnC mutants (Fig. 4B). Activation and inhibition of actomyosin-Tm-Tn ATPase activity by D145E has been reported in our previous study (23). D145E increased activation of the actomyosin-Tm-Tn ATPase activity, although it did not affect the inhibitory properties of the actomyosin ATPase (23).

FIGURE 4.

Activation and inhibition of the actomyosin-Tm ATPase activity as a function of Tn. A, activation of the ATPase activity is shown in the presence of Ca2+. B, inhibition of the ATPase activity is shown in the absence of Ca2+. Data are reported as means ± S.E. (n = 6–8).

Circular Dichroism

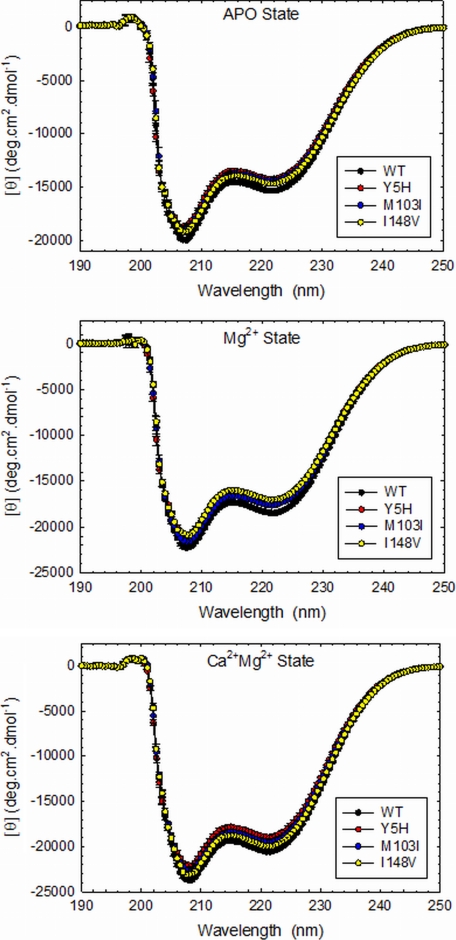

CD analyses were performed to address whether the mutations disrupt the normal secondary structure of the isolated protein. As shown in Fig. 5, the cTnC mutants decreased the amount of secondary structure under the apo (absence of cations) and Mg2+ conditions compared with WT cTnC. However, in the presence of Ca2+/Mg2+, I148V was the only mutant that did not show any significant rearrangements in secondary structure compared with WT cTnC (Fig. 5, lower panel). Table 4 lists the averages of the mean residue ellipticity in degrees·cm2·dmol−1 measured at 222 and 208 nm. The peaks at 222 and 208 nm are known to coincide with α-helix and β-sheets analyses, respectively. As reported previously, D145E showed a significant decrease in the amount of α-helix content in the apo- and Ca2+/Mg2+-bound states (23).

FIGURE 5.

Far-UV CD spectra. Experiments were performed in apo-, Mg2+-, and Ca2+/Mg2+-bound states. Spectra were recorded in a Jasco-720 spectropolarimeter at room temperature (21 °C). For each independent measurement, 10 scans were averaged. Data are summarized in Table 4. deg, degrees.

TABLE 4.

Far-UV circular dichroism

| TnC | [θ]222 nm |

n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apo | Mg2+ | Ca2+/Mg2+ | ||

| degrees·cm2·dmol−1 | ||||

| WT | 15,314.0 ± 29.4 | 18,496.6 ± 47.4 | 20,527.9 ± 114.3 | 4 |

| Y5H | 14,208.4 ± 208.5a | 17,173.7 ± 196.7a | 18,900.4 ± 261.1a | 4 |

| M103I | 14,397.5 ± 212.2a | 17,588.8 ± 106.8a | 19,442.7 ± 343.3a | 4 |

| I148V | 14,617.7 ± 173.5a | 17,014.8 ± 46.1a | 19,919.0 ± 225.7 | 4 |

| [θ]208 nm | ||||

| WT | 19,729.9 ± 74.6 | 22,208.2 ± 54.0 | 23,767.0 ± 121.6 | 4 |

| Y5H | 18,426.9 ± 134.5a | 20,852.7 ± 230.9a | 22,075.7 ± 299.2a | 4 |

| M103I | 18,704.4 ± 295.8a | 21,514.1 ± 123.8a | 22,787.2 ± 354.0a | 4 |

| I148V | 18,972.0 ± 298.2a | 20,899.9 ± 5.0a | 23,078.7 ± 299.1 | 4 |

Mean residue ellipticity ([θ]MRE in degrees·cm2·dmol−1) for the spectra was calculated utilizing the same Jasco software and the following equation: [θ]MRE = [θ]/(10 × Cr × l), where [θ] is the measured ellipticity in millidegrees, Cr is the mean residue molar concentration, and l is the path length in centimeters.

a p < 0.05 compared with WT TnC under the same conditions.

DISCUSSION

Three novel variants (Y5H, M103I, and I148V) showed functional properties typical of those reported previously in DCM associated with cTn mutations. These properties include decreased Ca2+ sensitivity of contraction, impaired response of the myofilament to undergo Ca2+ desensitization upon PKA phosphorylation, and often a diminished capacity to recover force in skinned fibers. Furthermore, reconstituted ATPase assays frequently show an impaired ability to activate the thin filament (8, 15, 26–29). With regard to PKA phosphorylation, these responses were altered in all of the novel DCM mutants tested here, consistent with what was shown previously for the DCM TnC mutation G159D (9). Further evidence of this phenomenon was provided when the cTnC mutations Y5H and I148V blunted PKA-mediated Ca2+ desensitization in skinned fibers, whereas M103I completely abolished the effects of PKA phosphorylation.

The fourth cTnC variant, D145E, previously reported in association with HCM (22), was observed in our study in an individual with a DCM phenotype who also harbored another sarcomeric rare variant in MYBPC3. With the D145E variant, we have previously observed enhanced myofilament Ca2+ sensitization, consistent with HCM (4, 22). We suggest that the sarcomeric mutation in MYBPC3 may have modulated the otherwise likely HCM phenotype, based on prior reports, to the DCM phenotype observed in this patient. These results point to the complexity of mutation-based disease, where mutations in sarcomeric proteins such as cTnC may alter the proteins themselves, interactions with their associated proteins, or the ability to respond to higher order converging systems of regulation.

This study provides a valuable integration of clinical DCM data from different DCM-associated mutations to add to the evidence that these rare variants are indeed disease-causing and to rigorously assess the fundamental basis of myofilament dysfunction. The precise molecular pharmacologic mechanisms of DCM are still unclear; however, most of the DCM mutations (including Y5H and M103I studied here) significantly decrease the Ca2+ sensitivity of skinned fibers (4). Another emerging concept is that the DCM mutations may affect the phosphorylation status/function of cTnI, and this may be an important parameter governing disease phenotypes (9, 30, 31). A number of thin filament mutations in TNNI3, ACTC, and TNNC1 (also reported here) have been found to uncouple the effects of PKA phosphorylation on Ca2+ sensitivity, although these mutations do not always produce the same clinical phenotype (9, 30–32). This observation is based on a limited number of mutations that diminish lusitropy in the heart and impair heart rate acceleration and increased contractile force normally induced by β-adrenergic stimulation. Subsequently, this dysfunction causes the heart to lose its dynamic response to stress. In humans, it has been shown that DCM mutations involve primarily defective force transmission (33), which in functional studies is observed as decreased force recovery in skinned fibers with a corresponding reduction in ATPase activation (8, 15, 26, 27, 29). In vitro motility assays also indicated a decrease in Ca2+ sensitivity and a loss of thin filament sliding velocity (10). This dysfunction at the myofilament level may progress over time and lead to diastolic and systolic dysfunction, pathological remodeling, and ultimately heart failure.

Mutations occurring in proteins such as phospholamban are normally accompanied by altered Ca2+ handling, a hallmark of DCM (34–36). We speculated that the decrease in myofilament Ca2+ affinity may affect cytosolic Ca2+ levels, interfering with the Ca2+ transient, thus leading to cardiac dysfunction and a predisposition to arrhythmia (37). We have previously shown in transgenic animal models bearing TnI Ca2+-sensitizing mutations that they also display a simultaneous delay in Ca2+ transients in intact papillary muscle fibers (38, 39). This further highlights the importance of cTnC to the responsiveness of the thin filament to Ca2+, the fundamental stimulus signaling contraction. Mutations in cTn may also diminish the contractile response, which could subsequently lead to a reduction in the ejection fraction seen in DCM patients.

The CD studies of isolated cTnC provide insight into whether the DCM mutations alter the global structure and capacity to transduce the Ca2+-binding signal throughout the thin filament. Mutations Y5H, M103I, D145E, and I148V decrease the α-helix content of cTnC, which may be associated with a less coordinated response to Ca2+ binding and decreased Ca2+ sensitivity in skinned fibers (23, 28). Interestingly, Y5H is the second cTnC mutation found within the N-helix, known for its ability to modulate the Ca2+ affinity of Site II (40, 41). Conversely, the HCM cTnC mutation A8V, also located in the N-helix, increases the Ca2+ sensitivity and the amount of α-helix. These rare point mutations alter the structure of cTnC, which in turn affect the ability of the myofilament to bind Ca2+.

A limitation of our study is that we were unable to simultaneously introduce the MYBPC3 or MYH7 mutations into our system(s) in which we evaluated the TNNC1 mutations. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the additional functional consequences that these other mutations may confer. The cTnC D145E mutation had been previously described as an HCM mutation (22), and functional studies indicated that this replacement in cTnC corroborates its HCM phenotype (23). One possibility is that this TnC mutation in combination with MYBPC3 P910T had an altered functional profile that led to the DCM phenotype instead of HCM as shown previously. Unfortunately, our physiological system did not permit us to address this question. Alternately, as described previously, some HCM patients develop DCM at later stages of disease (42–45). It is possible that an animal model for these mutations would better address these points. The cTnC Y5H mutation led to the development of a very severe clinical phenotype in the proband compared with the other cTnC mutations, with DCM onset at 2 weeks of age. The presence of the β-myosin heavy chain R1045C mutation accompanying cTnC Y5H may have potentiated the myofilament dysfunction and misregulation of the cardiac muscle. For example, the Y5H mutation did not show altered activation of the actomyosin ATPase, a trend found in most troponin mutations associated with DCM. However, we speculate that the absence of the additional mutation in our experimental system may have obscured a more complete functional profile of the double mutation. It has been shown that animal models bearing double mutations present a more severe phenotype (46). A murine model that contained the cTnI G203S and myosin R403Q mutations showed an increased mortality rate with survival of ∼21 days (46). At 14 days of age, the double mutant mouse model developed the clinical and molecular features of cardiac hypertrophy such as increased heart/body weight ratio and interstitial myocardial fibrosis. Interestingly, by 16–18 days of age, the double mutant mice developed severe DCM associated with heart failure (46). It has been reported that the occurrence of double or triple sarcomeric mutations in HCM patients might be associated with earlier onset of the disease and a more severe clinical phenotype (47).

Until recently, TNNC1 was not considered a cardiomyopathy-associated gene (48). We recently demonstrated a set of mutations in TNNC1 linked to HCM with the potential to disrupt myocardial contractility (23). Before this report, only two mutations in TNNC1 had been linked to DCM (6, 7, 18). The G159D (6, 7) and Q50R (18) mutations have been shown to segregate among family members. These functional studies of G159D have strengthened our knowledge of its effects and potential to cause disease. Translational studies such as these provide a basis for comparison of the pathogenic phenotypes of DCM-associated mutations in the clinical setting with mechanistic analysis to further dissect the fundamental basis of myofilament dysfunction (49). In conclusion, these combined clinical, genetic, and functional data reinforce the importance of TNNC1 rare variants in the pathogenesis of human DCM.

Acknowledgments

We thank the many families and referring physicians for participation in the Familial Dilated Cardiomyopathy Research Program, without whom these studies would not have been possible.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HL58626 (to R. E. H.), R01-HL42325 (to J. D. P.), and 1K99HL103840-01 (to J. R. P.). Resequencing services were provided by the University of Washington Department of Genome Sciences under United States Federal Government Contract N01-HV-48194 from NHLBI.

- DCM

- dilated cardiomyopathy

- cTn

- cardiac troponin

- HCM

- hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- CDTA

- 1,2-cyclohexylenedinitrilotetraacetic acid

- Tm

- tropomyosin.

REFERENCES

- 1. Burkett E. L., Hershberger R. E. (2005) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 969–981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lakdawala N. K., Givertz M. M. (2010) Circulation 122, 527–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hershberger R. E., Morales A., Siegfried J. D. (2010) Genet. Med. 12, 655–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Willott R. H., Gomes A. V., Chang A. N., Parvatiyar M. S., Pinto J. R., Potter J. D. (2010) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 48, 882–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Endoh M. (2008) Circ. J. 72, 1915–1925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mogensen J., Murphy R. T., Shaw T., Bahl A., Redwood C., Watkins H., Burke M., Elliott P. M., McKenna W. J. (2004) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 44, 2033–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kaski J. P., Burch M., Elliott P. M. (2007) Cardiol. Young 17, 675–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dweck D., Hus N., Potter J. D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33119–33128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Biesiadecki B. J., Kobayashi T., Walker J. S., John Solaro R., de Tombe P. P. (2007) Circ. Res. 100, 1486–1493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mirza M., Marston S., Willott R., Ashley C., Mogensen J., McKenna W., Robinson P., Redwood C., Watkins H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28498–28506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kranias E. G., Solaro R. J. (1982) Nature 298, 182–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robertson S. P., Johnson J. D., Holroyde M. J., Kranias E. G., Potter J. D., Solaro R. J. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 260–263 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang R., Zhao J., Mandveno A., Potter J. D. (1995) Circ. Res. 76, 1028–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baryshnikova O. K., Robertson I. M., Mercier P., Sykes B. D. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 10950–10960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dweck D., Reynaldo D. P., Pinto J. R., Potter J. D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17371–17379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lim C. C., Yang H., Yang M., Wang C. K., Shi J., Berg E. A., Pimentel D. R., Gwathmey J. K., Hajjar R. J., Helmes M., Costello C. E., Huo S., Liao R. (2008) Biophys. J. 94, 3577–3589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ho Y. L., Lin Y. H., Tsai W. Y., Hsieh F. J., Tsai H. J. (2009) Circ. J. 73, 1691–1697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. van Spaendonck-Zwarts K. Y., van Tintelen J. P., van Veldhuisen D. J., van der Werf R., Jongbloed J. D., Paulus W. J., Dooijes D., van den Berg M. P. (2010) Circulation 121, 2169–2175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hershberger R. E., Norton N., Morales A., Li D., Siegfried J. D., Gonzalez-Quintana J. (2010) Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 3, 155–161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kushner J. D., Nauman D., Burgess D., Ludwigsen S., Parks S. B., Pantely G., Burkett E., Hershberger R. E. (2006) J. Card. Fail. 12, 422–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hershberger R. E., Parks S. B., Kushner J. D., Li D., Ludwigsen S., Jakobs P., Nauman D., Burgess D., Partain J., Litt M. (2008) Clin. Transl. Sci. 1, 21–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Landstrom A. P., Parvatiyar M. S., Pinto J. R., Marquardt M. L., Bos J. M., Tester D. J., Ommen S. R., Potter J. D., Ackerman M. J. (2008) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 45, 281–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pinto J. R., Parvatiyar M. S., Jones M. A., Liang J., Ackerman M. J., Potter J. D. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 19090–19100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gomes A. V., Guzman G., Zhao J., Potter J. D. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35341–35349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fiske C. H., SubbaRow Y. (1925) J. Biol. Chem. 66, 375–400 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Venkatraman G., Harada K., Gomes A. V., Kerrick W. G., Potter J. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41670–41676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morimoto S., Lu Q. W., Harada K., Takahashi-Yanaga F., Minakami R., Ohta M., Sasaguri T., Ohtsuki I. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 913–918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Parvatiyar M. S., Pinto J. R., Liang J., Potter J. D. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27785–27797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carballo S., Robinson P., Otway R., Fatkin D., Jongbloed J. D., de Jonge N., Blair E., van Tintelen J. P., Redwood C., Watkins H. (2009) Circ. Res. 105, 375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Song W., Dyer E., Stuckey D., Leung M. C., Memo M., Mansfield C., Ferenczi M., Liu K., Redwood C., Nowak K., Harding S., Clarke K., Wells D., Marston S. (2010) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 49, 380–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Dyer E. C., Jacques A. M., Hoskins A. C., Ward D. G., Gallon C. E., Messer A. E., Kaski J. P., Burch M., Kentish J. C., Marston S. B. (2009) Circ. Heart Fail. 2, 456–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gomes A. V., Harada K., Potter J. D. (2005) J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 39, 754–765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Olson T. M., Michels V. V., Thibodeau S. N., Tai Y. S., Keating M. T. (1998) Science 280, 750–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmitt J. P., Kamisago M., Asahi M., Li G. H., Ahmad F., Mende U., Kranias E. G., MacLennan D. H., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. (2003) Science 299, 1410–1413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Haghighi K., Kolokathis F., Pater L., Lynch R. A., Asahi M., Gramolini A. O., Fan G. C., Tsiapras D., Hahn H. S., Adamopoulos S., Liggett S. B., Dorn G. W., 2nd, MacLennan D. H., Kremastinos D. T., Kranias E. G. (2003) J. Clin. Invest. 111, 869–876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeWitt M. M., MacLeod H. M., Soliven B., McNally E. M. (2006) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 48, 1396–1398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wehrens X. H., Lehnart S. E., Marks A. R. (2005) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1047, 366–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wen Y., Pinto J. R., Gomes A. V., Xu Y., Wang Y., Wang Y., Potter J. D., Kerrick W. G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20484–20494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wen Y., Xu Y., Wang Y., Pinto J. R., Potter J. D., Kerrick W. G. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 392, 1158–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith L., Greenfield N. J., Hitchcock-DeGregori S. E. (1999) Biophys. J. 76, 400–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith L., Greenfield N. J., Hitchcock-DeGregori S. E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 9857–9863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nanni L., Pieroni M., Chimenti C., Simionati B., Zimbello R., Maseri A., Frustaci A., Lanfranchi G. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 309, 391–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fujino N., Shimizu M., Ino H., Yamaguchi M., Yasuda T., Nagata M., Konno T., Mabuchi H. (2002) Am. J. Cardiol. 89, 29–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fujino N., Shimizu M., Ino H., Okeie K., Yamaguchi M., Yasuda T., Kokado H., Mabuchi H. (2001) Clin. Cardiol. 24, 397–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Freeman K., Colon-Rivera C., Olsson M. C., Moore R. L., Weinberger H. D., Grupp I. L., Vikstrom K. L., Iaccarino G., Koch W. J., Leinwand L. A. (2001) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 280, H151–H159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tsoutsman T., Kelly M., Ng D. C., Tan J. E., Tu E., Lam L., Bogoyevitch M. A., Seidman C. E., Seidman J. G., Semsarian C. (2008) Circulation 117, 1820–1831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Girolami F., Ho C. Y., Semsarian C., Baldi M., Will M. L., Baldini K., Torricelli F., Yeates L., Cecchi F., Ackerman M. J., Olivotto I. (2010) J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 1444–1453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Liew C. C., Dzau V. J. (2004) Nat. Rev. Genet. 5, 811–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hershberger R. E., Pinto J. R., Parks S. B., Kushner J. D., Li D., Ludwigsen S., Cowan J., Morales A., Parvatiyar M. S., Potter J. D. (2009) Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2, 306–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]