Abstract

Elevated IgE levels and increased IgE sensitization to allergens are central features of allergic asthma. IgE binds to the high-affinity Fcϵ receptor I (FcϵRI) on mast cells, basophils, and dendritic cells and mediates the activation of these cells upon antigen-induced cross-linking of IgE-bound FcϵRI. FcϵRI activation proceeds through a network of signaling molecules and adaptor proteins and is negatively regulated by a number of cell surface and intracellular proteins. Therapeutic neutralization of serum IgE in moderate-to-severe allergic asthmatics reduces the frequency of asthma exacerbations through a reduction in cell surface FcϵRI expression that results in decreased FcϵRI activation, leading to improved asthma control. Our increasing understanding of IgE receptor signaling may lead to the development of novel therapeutics for the treatment of asthma.

Keywords: Adaptor Proteins, Calcium, Lipid Raft, Mast Cell, Signal Transduction, Asthma, FcϵRI, IgE

Introduction

Asthma is a disease characterized by reversible airway obstruction, airway hyper-reactivity, and chronic airway inflammation that manifest as symptoms such as coughing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and wheezing. Asthma is estimated to affect up to 300 million people worldwide, and although the majority of asthmatics are well controlled by treatment with inhaled corticosteroids and bronchodilators, many asthmatics are still inadequately controlled by current therapies, with the most severe asthmatics responding poorly to all available medications (1). Given that the most severe 5–10% of asthmatics are estimated to account for nearly 50% of total healthcare costs related to asthma, there is a significant need for new therapies for the treatment of asthma (2).

Asthma is one of several allergic diseases that are associated with elevated IgE levels and increased IgE sensitization to allergens (3, 4). IgE binds to two different receptors, the high-affinity Fcϵ receptor I (FcϵRI)2 and the low-affinity receptor FcϵRII/CD23 (4). In humans, FcϵRI is found on mast cells and basophils, where it is a tetrameric complex consisting of one α-chain, one β-chain, and two disulfide-bonded γ-chains, and on dendritic cells, Langerhans cells, macrophages, and eosinophils, where it is a trimeric complex consisting of one α-chain and two disulfide-bonded γ-chains (5). The FcϵRI α-subunit (FcϵRIα) is unique to FcϵRI, whereas the β- and γ-subunits (FcRβ and FcRγ, respectively) form complexes with other Fc receptors and, in the case of FcRγ, the T cell receptor, in addition to FcϵRI. IgE stabilizes the cell surface levels of FcϵRI by preventing the internalization of the receptor from the cell surface (6). The up-regulation of cell surface FcϵRI levels by IgE increases the sensitivity of cells to FcϵRI activation triggered by allergen-induced cross-linking of IgE that is bound to FcϵRI. Activation of FcϵRI on mast cells and basophils leads to degranulation, eicosanoid production, and cytokine production, which are associated with early- and late-phase anaphylactic reactions that can result in exacerbations of asthma (3–5). Activation of FcϵRI on dendritic cells leads to increased antigen presentation and cytokine and chemokine production, which may enhance T-helper 2 cell sensitization, which promotes the allergic inflammation that drives asthma pathogenesis (3–5). CD23 is found on B cells and myeloid cells, where it is a homotrimeric complex that regulates IgE synthesis and mediates antigen presentation (4, 7, 8).

A key role for FcϵRI signaling in the pathogenesis of allergic asthma was demonstrated by the therapeutic neutralization of serum IgE in moderate and severe allergic asthmatics, including those who respond poorly to all other therapies, using a monoclonal antibody that blocks the binding of IgE to both of its receptors (9, 10). Treatment with anti-IgE antibody results in significant anti-inflammatory effects that ultimately lead to a reduction in the frequency of asthma exacerbations (11). Upon neutralization of serum IgE, cell surface FcϵRI levels are reduced on mast cells, basophils, and dendritic cells (12–14). The reduction in mast cell and basophil surface FcϵRI levels results in decreased FcϵRI activation and is proposed to be the primary mechanism underlying the efficacy of anti-IgE treatment. However, anti-IgE therapy does not completely abrogate FcϵRI activation; has a relatively slow onset of efficacy; and, due to dosing limitations, is not approved for patients with very high IgE levels, who might benefit the most from neutralization of serum IgE. Thus, approaches that inhibit FcϵRI activation more directly, potently, and quickly than anti-IgE therapy are promising new therapies for the treatment of asthma. Given the important role of FcϵRI signaling and mast cell activation in asthma pathogenesis, this minireview focuses on recent advances in our understanding of the positive and negative regulation of FcϵRI signaling in mast cells. For a detailed discussion of CD23, see several excellent reviews that cover CD23 structure, signaling, and function (4, 7, 8).

FcϵRI Expression, Distribution, and Dynamics at the Cell Surface

The FcϵRIα, FcRβ, and FcRγ components of the tetrameric FcϵRI complex in mast cells have different functions in FcϵRI signaling. FcϵRIα contains an extracellular domain that binds IgE but does not directly mediate intracellular signaling. FcRγ contains a cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM) that couples FcϵRI cross-linking to the initiation of intracellular signaling. FcRβ also contains an ITAM and functions as an amplifier of intracellular signals. The cell surface expression of the human FcϵRI complex is regulated by a number of factors. FcϵRIα contains multiple endoplasmic reticulum (ER) retention signals that reside in the signal peptide, transmembrane, and cytoplasmic regions of the FcϵRIα sequence (15–18). Additional residues in the transmembrane domain of FcϵRIα mediate interactions with FcRγ that are required for cell surface expression (19). In addition to its role in directly promoting FcϵRI signaling via its ITAM, FcRβ also acts as a chaperone that increases cell surface FcϵRI expression (20). Members of the Rab family of GTPases and their intracellular cofactors, such as Rab5, Rabex-5/RabGEF1, and Rabaptin-5, regulate cell surface levels of FcϵRI by modulating FcϵRI internalization and the cell surface stability of FcϵRI (21, 22).

Cross-linking of many cell surface receptors results in receptor partitioning to detergent-insoluble membrane lipid fractions (lipid rafts) (23). Lipid rafts are enriched in signaling and adaptor molecules that mediate intracellular signal transduction, and the localization of cell surface receptors to lipid rafts assists the signal transduction process. For FcϵRI, biochemical and biophysical studies have demonstrated that cross-linking and activation are associated with redistribution of FcϵRI to lipid rafts, and this recruitment of FcϵRI to lipid rafts is important for FcϵRI signaling (24). However, the overall role of lipid rafts in the initiation versus maintenance of FcϵRI signaling is unclear. One model of FcϵRI signaling postulates that activation is initiated in lipid rafts, requiring the recruitment of FcϵRI to lipid raft environments that contain the initiating Src family kinase Lyn (25). Another model of FcϵRI signaling postulates that activation can be initiated outside of lipid raft compartments, where a small fraction of Lyn that is pre-associated with the FcR β-subunit activates FcϵRI signaling upon receptor cross-linking (26, 27). In this model, the recruitment of FcϵRI to lipid rafts is important for signal propagation and maintenance through adaptor proteins such as LAT, but not initiation. Recent biophysical studies of FcϵRI and membrane lipid distribution and dynamics have enabled the monitoring of very small lipid raft microdomains in cells under physiologic conditions. The results of these studies suggest a hybrid of both models and indicate that lipid raft microdomains coalesce upon cross-linking of FcϵRI and redistribute with aggregated FcϵRI proteins in a time frame that correlates with the kinetics of FcϵRI phosphorylation (28, 29).

Signaling Events Proximal to FcϵRI

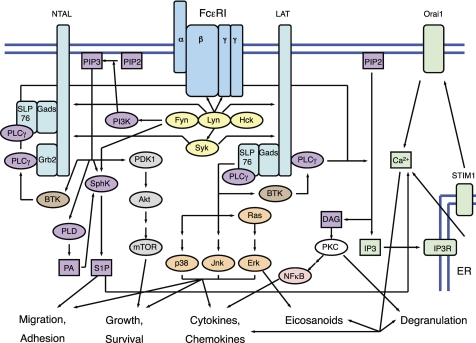

Intracellular FcϵRI signaling proceeds through a network of signaling molecules and adaptor proteins (Fig. 1). The Src family kinases mediate intracellular signaling events that are proximal to FcϵRI (30, 31). Lyn is the most highly expressed Src family kinase in mast cells, and it initiates FcϵRI signaling by phosphorylating the ITAMs of FcRβ and FcRγ. However, the overall role of Lyn as a positive or negative regulator of mast cell activation downstream of FcϵRI is controversial. Substrates for Lyn phosphorylation include both positive regulators of FcϵRI signal transduction such as Syk and negative regulators of FcϵRI signal transduction such as Cbp (Csk-binding protein), which recruits Csk, a negative regulator of Src family kinases (32–34). In vitro studies of Lyn knock-out mast cells have demonstrated increased, decreased, or unaffected degranulation and increased cytokine production upon FcϵRI activation compared with wild-type mast cells (32, 33, 35–37). The discrepancy in effects of Lyn deficiency on mast cell degranulation in these various studies may be due to genetic differences in Fyn expression and activity that are associated with different mouse background strains (38). It may also be due to differences in the strength of FcϵRI stimulation that result in differences in the net role of Lyn as a positive or negative regulator of FcϵRI signaling (34). The interpretation of in vivo studies of Lyn knock-out mice is complicated by age-dependent increases in serum IgE, total numbers of mast cells, and spontaneous mast cell activation. Young Lyn knock-out mice have a hyper-responsive degranulation phenotype in vivo compared with wild-type mice, indicating an overall negative regulatory role for Lyn in mast cell degranulation downstream of FcϵRI activation in vivo (33). Although older Lyn knock-out mice have a defective degranulation phenotype in vivo, this phenotype appears to result from a reduced ability to sensitize these mice with exogenous IgE due to high circulating levels of endogenous IgE as opposed to inherent defects in FcϵRI-mediated mast cell activation (33, 39).

FIGURE 1.

FcϵRI signaling in mast cells proceeds through a network of signaling molecules and adaptor proteins, ultimately leading to effects on cell migration and adhesion, growth and survival, degranulation, eicosanoid production, and cytokine and chemokine production. FcϵRI in mast cells is a tetrameric complex consisting of an α-subunit, a β-subunit, and two disulfide-bonded γ-subunits (blue). Proximal FcϵRI signaling is mediated through Src family kinases and Syk (yellow). Adaptor proteins include LAT, NTAL/LAB/LAT2, Grb2, Gads, and SLP76 (aqua). Lipid signaling pathways are mediated by PI3K, SphK, PLD, and PLCγ (purple). Calcium signaling proceeds through a two-step process, consisting of the initial release of intracellular ER calcium stores, followed by extracellular calcium influx (green). Additional signaling molecules and pathways include Btk, which links PI3K activation to PLCγ activation (brown); Ras/MAPK pathways (orange); the PDK1/Akt/mTOR pathway (gray); PKCs (white); and NF-κB (pink). PA, phosphatidic acid; IP3R, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor.

Other Src family kinases that play a role in FcϵRI signaling are Fyn and Hck. Both Fyn and Hck have positive regulatory roles in mast cell activation such that Fyn and Hck knock-out mast cells have reduced degranulation and cytokine production upon FcϵRI activation (40–42). Fyn is involved in the activation of lipid signaling pathways mediated by PI3K, sphingosine kinase (SphK), and phospholipase D (PLD), which are discussed further below. Among Lyn, Fyn, and Hck, Hck negatively regulates Lyn, and Lyn negatively regulates Fyn (42). Lyn knock-out mast cells with enhanced Fyn activity are hyper-responsive to FcϵRI activation (33). Reduction of Lyn function through disruption of Lyn localization to lipid rafts can also lead to increased Fyn activity (43). This may provide an explanation for the allergic phenotypes that are observed in humans with Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome, a disease that arises from a defective gene mutant of 3β-hydroxysterol Δ7-reductase (DHCR7), an enzyme that converts 7-dehydrocholesterol to cholesterol. Knock-out of DHCR7 in mice results in a disruption of lipid raft stability due to low cholesterol levels and a reduction in the lipid raft localization of FcϵRI and Lyn (43). Fyn activity is increased in DHCR7 knock-out mouse mast cells, resulting in increased mast cell degranulation upon activation of FcϵRI.

A key mediator of proximal FcϵRI signaling is Syk, which is recruited to the FcϵRI complex by association with phosphorylated FcRγ (30). Subsequent to its association with FcϵRI, Syk is phosphorylated and activated by Lyn. Syk phosphorylates the adaptor proteins LAT and NTAL/LAB/LAT2, whose functions are described below, and thereby coordinates the activation of multiple downstream signaling pathways. This ultimately leads to mast cell degranulation, eicosanoid production, and cytokine production (44). Structural and functional aspects of Syk activity in mast cell signaling have been reviewed extensively (30, 45).

Adaptor Proteins in FcϵRI Signaling

Two major adaptor proteins downstream of FcϵRI signaling are LAT and NTAL/LAB/LAT2 (46). Phosphorylation of LAT by Syk leads to the recruitment and activation of phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), which is discussed further below, as well as the recruitment and activation of Ras/Rho GTPases and MAPKs (i.e. p38, JNK, and ERK), leading to mast cell degranulation, eicosanoid production, and cytokine production (47). The LAT adaptor protein integrates both positive and negative regulatory signals downstream of FcϵRI activation (48), leading to an overall positive regulatory role in FcϵRI signaling. The overall role of NTAL in FcϵRI signaling is less clear, with different studies indicating either positive or negative regulatory roles based on mouse gene knock-out and human RNAi knockdown studies in which the entire NTAL protein was deleted (49–52). Two recent studies have focused on a positive regulatory role for NTAL in linking FcϵRI activation to PLCγ activation through pathways that are parallel to and independent of LAT-mediated PLCγ activation (49, 53). One study demonstrated that the adaptor protein Grb2 is recruited to phosphorylated NTAL. The subsequent phosphorylation of Grb2 triggers the recruitment and activation of PLCγ (49). The other study showed that a Gads- and SLP76-mediated pathway that is coupled to NTAL links FcϵRI activation to PLCγ activation (53). Aside from LAT and NTAL, a number of additional adaptor proteins that play a role in FcϵRI signaling, many of which associate with LAT and NTAL to form large scaffolding complexes (e.g. Grb2, Gads, and SLP76), have been extensively discussed by others (46).

Lipid Signaling Downstream of FcϵRI

Several lipid signaling pathways are activated downstream of FcϵRI via Fyn, including pathways mediated by PI3K, SphK, and PLD (31, 54). The PI3K enzymes catalyze the phosphorylation of the inositol ring of membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) at the D3 position to generate phosphatidylinositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3), a major intracellular lipid mediator that has effects on multiple signaling pathways involved in degranulation and cytokine production.

The PI3K enzyme family consists of three subclasses, of which the class I PI3Ks are the most well understood (55, 56). The class I PI3Ks are further subdivided into class IA and class IB PI3Ks. The class IA PI3Ks consist of a p85 regulatory subunit and a p110 catalytic subunit; there are five isoforms of p85 and three isoforms of p110. The class IB PI3Ks consist of a p101 or p87PIKAP regulatory subunit and a p110 catalytic γ-subunit. The p110 α- and β-isoforms are ubiquitously expressed, and the p110 δ- and γ-isoforms (p110δ and p110γ, respectively) are expressed mainly in leukocytes. Both p110δ and p110γ contribute to FcϵRI signaling in mast cells (57–59). p110δ is directly activated downstream of FcϵRI, and genetic and pharmacologic inactivation of p110δ leads to reduced mast cell degranulation, eicosanoid production, and cytokine production both in vitro and in vivo (57, 58). The role of p110γ in FcϵRI-induced mast cell activation is more controversial. p110γ is activated by G-protein-coupled receptors. As such, it is indirectly activated downstream of FcϵRI via autocrine mast cell signals that are mediated by adenosine and other G-protein-coupled receptor agonists (59). In vitro stimulation of mast cells from p110γ knock-out mice results in reduced degranulation compared with mast cells from wild-type mice (58, 59). However, whereas one study reported reduced in vivo activation of mast cells in p110γ knock-out mice (59), another study reported a lack of effect of p110γ knock-out or pharmacologic inactivation of p110γ on in vivo mast cell activation (58).

PIP3 that is generated by PI3K enzymes recruits several signaling proteins to the cell membrane via interaction with pleckstrin homology domains in these proteins, thereby propagating intracellular signaling. These signaling effectors include PDK1, which activates Akt to promote cell proliferation and survival (54), and Btk (37, 60), which activates PLCγ. PIP3 also has regulatory effects on PLD and SphK. PI3K is positively regulated by RasGRP1 (61), in addition to being activated by Fyn. Mast cells from RasGRP1 knock-out mice show defects in multiple pathways downstream of PIP3, including reduced phosphorylation of Akt. This results in reduced degranulation and cytokine production upon FcϵRI activation of RasGRP1 knock-out mast cells.

SphKs generate sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) from sphingosine. There are two SphK isoforms, but the contribution of each SphK isoform to FcϵRI signaling and mast cell activation is controversial. One group has defined an intracellular pathway whereby SphK2 generates S1P, which subsequently promotes intracellular calcium signaling that results in mast cell degranulation and cytokine production (62). SphK1 in other cell types generates S1P that is released extracellularly and acts on mast cells via the S1P1 and S1P2 receptors to promote mast cell migration and to enhance mast cell degranulation and cytokine production upon FcϵRI activation. On the other hand, data from other groups indicate that SphK1, as opposed to SphK2, is the major intracellular source of S1P in mast cells downstream of FcϵRI activation (63, 64). These groups have also described roles for extracellular S1P in mast cell migration and FcϵRI activation via the S1P1 and S1P2 receptors (65, 66).

Calcium Signaling Downstream of FcϵRI

Intracellular calcium signaling contributes to degranulation, eicosanoid production, and cytokine production downstream of FcϵRI activation. FcϵRI-induced calcium signaling in mast cells occurs in two steps, the first being release of calcium from intracellular calcium stores in the ER and the second being calcium influx from the extracellular space through store-operated calcium channels (67). Intracellular calcium signaling is regulated by PLCγ, which generates inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol from PIP2. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate stimulates the release of intracellular calcium stores upon binding to its receptor in the ER. The depletion of ER calcium stores then triggers extracellular calcium influx. Diacylglycerol and intracellular calcium signals cooperate to activate PKCs, which then activate other pathways such as the NF-κB pathway, ultimately leading to mast cell degranulation and cytokine production.

Our understanding of intracellular calcium signaling has advanced significantly in recent years due to the discovery of the identity of key components and regulators of store-operated calcium channels. STIM1 (stromal interaction molecule 1) was identified as a calcium sensor located in the ER that couples the depletion of intracellular ER calcium stores to the activation of store-operated calcium channels (68, 69). Orai1/CRACM1 is a recently discovered membrane protein that constitutes the store-operated calcium channel (70–73). Mutation of Orai1 in humans results in severe combined immunodeficiency that is due to a lack of store-operated calcium channel function. Both STIM1 and Orai1 knock-out mast cells are deficient in intracellular calcium signaling downstream of FcϵRI activation due to defective influx of calcium from the extracellular space, leading to defective mast cell degranulation, eicosanoid production, and cytokine production (74, 75). Recent data indicate that Syk is a local sensor of calcium signaling that contributes to a positive feedback loop downstream of store-operated calcium channel opening and that also couples extracellular calcium influx to the activation of PKC and other pathways (76, 77).

Negative Regulators of FcϵRI Signaling

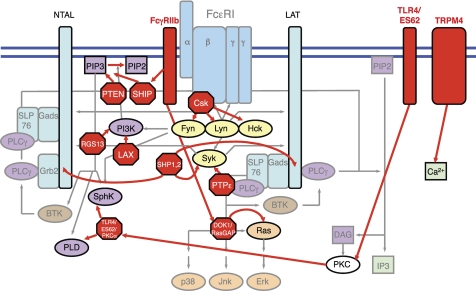

Negative regulators of FcϵRI signaling can be grouped into intracellular and cell surface proteins that act at various points in the FcϵRI signaling network (Fig. 2). Intracellular negative regulators of FcϵRI signaling include the SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases, which inhibit the activity of signaling proteins that are proximal to FcϵRI such as Syk and Fyn and adaptor proteins such as LAT and NTAL (78, 79). Protein-tyrosine phosphatase ϵ is a phosphatase that also acts at a proximal point in the FcϵRI signaling network by inhibiting Syk activity (80). The PI3K pathway is negatively regulated by SHIP and PTEN (81), which directly dephosphorylate PIP3 to generate PIP2. SHIP dephosphorylates the phosphate at the D5 position of the inositol ring of PIP3, whereas PTEN dephosphorylates the phosphate at the D3 position. The PI3K pathway is also negatively regulated by RGS13 and LAX (82, 83), which inhibit the interaction of the PI3K p85 regulatory subunit with the Grb2-NTAL scaffolding complex. Mast cells that are deficient in these negative regulators have heightened degranulation and/or cytokine responses downstream of FcϵRI activation. Cell surface proteins on mast cells that negatively regulate FcϵRI activation include TRPM4 (84), which modulates extracellular calcium influx, and TLR4 (85), which, upon association with the ES62 product of filarial nematodes, traffics into vesicular compartments, where it sequesters and degrades PKCα, a protein kinase that mediates PLD and SphK activation downstream of FcϵRI.

FIGURE 2.

The FcϵRI signaling pathway is negatively regulated by a number of cell surface and intracellular proteins that act at various points in the FcϵRI signaling network. Proximal intracellular FcϵRI signaling and adaptor proteins are negatively regulated by Csk, protein-tyrosine phosphatase ϵ (PTPϵ), SHP-1, and SHP-2. PI3K signaling is negatively regulated by SHIP, PTEN, LAX, and RGS13. Ras signaling is negatively regulated by RasGAP. Cell surface proteins that negatively regulate FcϵRI signaling include TRPM4, which reduces calcium signaling, and TLR4, which, upon formation of a complex with the ES62 product of filarial nematodes, inhibits SphK and PLD signaling by sequestering and degrading SphK- and PLD-activating PKCα. Co-cross-linking of the ITIM-containing cell surface receptor FcγRIIb with FcϵRI triggers the inhibition of FcϵRI signaling at several points, including SHIP-mediated inactivation of PI3K signaling and DOK1/RasGAP-mediated inactivation of Ras signaling. Co-cross-linking of FcϵRI with other ITIM-containing cell surface receptors triggers the inhibition of FcϵRI signaling mediated by SHP-1 and SHP-2. DAG, diacylglycerol; IP3, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate.

A number of cell surface receptors that contain cytoplasmic immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motifs (ITIMs) are found in mast cells and function to negatively regulate FcϵRI activation upon co-engagement with FcϵRI by engaging endogenous negative regulatory pathways (86, 87). These ITIM-containing receptors include FcγRIIb (88), PIR-B (89), gp49B1 (90), myeloid-associated immunoglobulin receptor I (91), mast cell function-associated antigen (92), signal regulator protein α (93), and the recently identified Allergin-1 (94). The mechanisms of FcγRIIb-mediated inhibition of FcϵRI activation have been extensively described. Co-engagement of FcγRIIb with FcϵRI results in Lyn-mediated phosphorylation of the tyrosine residue in the FcγRIIb ITIM motif, which subsequently recruits the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHIP and the docking protein DOK1 to the FcϵRI complex (86, 87). SHIP is activated by phosphorylation and mediates dephosphorylation of PIP3 to generate PIP2, thereby directly inhibiting the PI3K pathway. DOK1 recruits and activates Ras GTPase-activating protein (RasGAP), which inhibits the Ras pathway by enhancing the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras. All other ITIM-containing cell surface receptors inhibit FcϵRI activation through the action of SHP-1 and SHP-2 phosphatases.

Therapeutic Targeting of FcϵRI Signaling

Given the clinical efficacy of therapeutic anti-IgE neutralization in asthma, which reduces FcϵRI activation and has revealed an important role for FcϵRI signaling in asthma pathogenesis, future therapies that directly target and inhibit FcϵRI signaling have significant potential for the treatment of asthma, especially those therapeutic strategies that lead to a more complete and/or faster inhibition of FcϵRI activation compared with anti-IgE therapy. Several intracellular proteins that play key roles in FcϵRI signaling and mast cell activation and whose therapeutic inhibition may lead to superior efficacy compared with anti-IgE therapy have been discussed in this minireview. Of these, there are significant ongoing efforts to generate small molecule inhibitors of Syk and PI3K, which have resulted in some compounds that have entered human clinical trials for asthma or other allergic diseases. There has also been recent progress in the generation of specific small molecule inhibitors of Btk (95). The discovery of STIM1 and Orai1 has spurred efforts to identify novel small molecule inhibitors of these components and regulators of store-operated calcium channels. A major concern associated with many of these small molecule targets is their broad biology beyond FcϵRI signaling, which may result in adverse safety profiles upon therapeutic targeting.

An alternative approach to the intracellular small molecule targeting of FcϵRI signaling utilizes protein-based therapeutics, which are well suited for specifically targeting cell surface proteins. Several groups have developed protein-based therapeutics that directly inhibit FcϵRI activation by co-cross-linking FcϵRI with various cell surface ITIM-containing receptors, most commonly FcγRIIb. These approaches include an IgE-Fc/IgG-Fc fusion protein that simultaneously engages FcϵRI and FcγRIIb (96), a specific allergen/IgG-Fc fusion protein that simultaneously engages allergen-specific IgE that is bound to FcϵRI and FcγRIIb (97), and various bispecific antibody technologies that co-cross-link FcϵRI with FcγRIIb or other ITIM-containing receptors (98, 99). Limitations of several of these protein-based therapeutics include poor in vivo pharmacokinetics, immunogenicity, and difficulties associated with large-scale manufacturing, although some new bispecific antibody formats can overcome many of these limitations (99, 100). Given the increasing development and use of antibody therapeutics for the treatment of diseases, including asthma, novel bispecific antibody approaches may help expand the scope of therapeutic targets in the future.

Summary

A substantial network of signaling molecules and adaptor proteins that function downstream of FcϵRI activation has been defined. Future studies will continue to elucidate the cell and membrane biology of FcϵRI signaling, novel cell surface and intracellular mediators of FcϵRI activation, mechanisms of intracellular calcium signaling, and new inhibitory proteins that negatively regulate parts of the signaling network downstream of FcϵRI activation. Our increasing understanding of FcϵRI signaling may lead to the development of new therapeutics that inhibit FcϵRI activation for the treatment of asthma.

Acknowledgments

I thank Marc Daeron, Alasdair Gilfillan, and Jean-Pierre Kinet for critical reading and helpful comments on the manuscript and Ei-Mang Wu for helpful advice on the figures.

L. C. W. is employed by Genentech, Inc. This is the third article in the Thematic Minireview Series on Molecular Bases of Disease: Asthma. This minireview will be reprinted in the 2011 Minireview Compendium, which will be available in January, 2012.

- FcϵR

- Fcϵ receptor

- ITAM

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- SphK

- sphingosine kinase

- PLD

- phospholipase D

- PLCγ

- phospholipase Cγ

- PIP2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PIP3

- phosphatidylinositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

- S1P

- sphingosine 1-phosphate

- ITIM

- immunoreceptor tyrosine-based inhibition motif

- RasGAP

- Ras GTPase-activating protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Fanta C. H. (2009) N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 1002–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chung K. F., Godard P., Adelroth E., Ayres J., Barnes N., Barnes P., Bel E., Burney P., Chanez P., Connett G., Corrigan C., de Blic J., Fabbri L., Holgate S. T., Ind P., Joos G., Kerstjens H., Leuenberger P., Lofdahl C. G., McKenzie S., Magnussen H., Postma D., Saetta M., Salmeron S., Sterk P. (1999) Eur. Respir. J. 13, 1198–1208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galli S. J., Tsai M., Piliponsky A. M. (2008) Nature 454, 445–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gould H. J., Sutton B. J. (2008) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8, 205–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kraft S., Kinet J. P. (2007) Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 365–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yamaguchi M., Lantz C. S., Oettgen H. C., Katona I. M., Fleming T., Miyajima I., Kinet J. P., Galli S. J. (1997) J. Exp. Med. 185, 663–672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Acharya M., Borland G., Edkins A. L., Maclellan L. M., Matheson J., Ozanne B. W., Cushley W. (2010) Clin. Exp. Immunol. 162, 12–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Conrad D. H. (1990) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 8, 623–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chang T. W., Wu P. C., Hsu C. L., Hung A. F. (2007) Adv. Immunol. 93, 63–119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holgate S. T., Djukanović R., Casale T., Bousquet J. (2005) Clin. Exp. Allergy 35, 408–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Holgate S., Casale T., Wenzel S., Bousquet J., Deniz Y., Reisner C. (2005) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 115, 459–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Beck L. A., Marcotte G. V., MacGlashan D., Togias A., Saini S. (2004) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 114, 527–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. MacGlashan D. W., Jr., Bochner B. S., Adelman D. C., Jardieu P. M., Togias A., McKenzie-White J., Sterbinsky S. A., Hamilton R. G., Lichtenstein L. M. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 1438–1445 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Prussin C., Griffith D. T., Boesel K. M., Lin H., Foster B., Casale T. B. (2003) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 112, 1147–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fiebiger E., Tortorella D., Jouvin M. H., Kinet J. P., Ploegh H. L. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 267–277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Platzer B., Fiebiger E. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 15314–15323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hartman M. L., Lin S. Y., Jouvin M. H., Kinet J. P. (2008) Mol. Immunol. 45, 2307–2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cauvi D. M., Tian X., von Loehneysen K., Robertson M. W. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 10448–10460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wines B. D., Trist H. M., Ramsland P. A., Hogarth P. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 17108–17113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Donnadieu E., Jouvin M. H., Kinet J. P. (2000) Immunity 12, 515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rios E. J., Piliponsky A. M., Ra C., Kalesnikoff J., Galli S. J. (2008) Blood 112, 4148–4157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kalesnikoff J., Rios E. J., Chen C. C., Alejandro Barbieri M., Tsai M., Tam S. Y., Galli S. J. (2007) Blood 109, 5308–5317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simons K., Vaz W. L. (2004) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 33, 269–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Field K. A., Holowka D., Baird B. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 9201–9205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sheets E. D., Holowka D., Baird B. (1999) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 95–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vonakis B. M., Haleem-Smith H., Benjamin P., Metzger H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 1041–1050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kovárová M., Tolar P., Arudchandran R., Dráberová L., Rivera J., Dráber P. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 8318–8328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davey A. M., Walvick R. P., Liu Y., Heikal A. A., Sheets E. D. (2007) Biophys. J. 92, 343–355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Davey A. M., Krise K. M., Sheets E. D., Heikal A. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 7117–7127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gilfillan A. M., Rivera J. (2009) Immunol. Rev. 228, 149–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rivera J., Olivera A. (2007) Immunol. Rev. 217, 255–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nishizumi H., Yamamoto T. (1997) J. Immunol. 158, 2350–2355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Odom S., Gomez G., Kovarova M., Furumoto Y., Ryan J. J., Wright H. V., Gonzalez-Espinosa C., Hibbs M. L., Harder K. W., Rivera J. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199, 1491–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xiao W., Nishimoto H., Hong H., Kitaura J., Nunomura S., Maeda-Yamamoto M., Kawakami Y., Lowell C. A., Ra C., Kawakami T. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 6885–6892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hernandez-Hansen V., Smith A. J., Surviladze Z., Chigaev A., Mazel T., Kalesnikoff J., Lowell C. A., Krystal G., Sklar L. A., Wilson B. S., Oliver J. M. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 100–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iwaki S., Tkaczyk C., Satterthwaite A. B., Halcomb K., Beaven M. A., Metcalfe D. D., Gilfillan A. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40261–40270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kawakami Y., Kitaura J., Satterthwaite A. B., Kato R. M., Asai K., Hartman S. E., Maeda-Yamamoto M., Lowell C. A., Rawlings D. J., Witte O. N., Kawakami T. (2000) J. Immunol. 165, 1210–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamashita Y., Charles N., Furumoto Y., Odom S., Yamashita T., Gilfillan A. M., Constant S., Bower M. A., Ryan J. J., Rivera J. (2007) J. Immunol. 179, 740–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hibbs M. L., Tarlinton D. M., Armes J., Grail D., Hodgson G., Maglitto R., Stacker S. A., Dunn A. R. (1995) Cell 83, 301–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Parravicini V., Gadina M., Kovarova M., Odom S., Gonzalez-Espinosa C., Furumoto Y., Saitoh S., Samelson L. E., O'Shea J. J., Rivera J. (2002) Nat. Immunol. 3, 741–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gomez G., Gonzalez-Espinosa C., Odom S., Baez G., Cid M. E., Ryan J. J., Rivera J. (2005) J. Immunol. 175, 7602–7610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hong H., Kitaura J., Xiao W., Horejsi V., Ra C., Lowell C. A., Kawakami Y., Kawakami T. (2007) Blood 110, 2511–2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kovarova M., Wassif C. A., Odom S., Liao K., Porter F. D., Rivera J. (2006) J. Exp. Med. 203, 1161–1171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Costello P. S., Turner M., Walters A. E., Cunningham C. N., Bauer P. H., Downward J., Tybulewicz V. L. (1996) Oncogene 13, 2595–2605 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Siraganian R. P., Zhang J., Suzuki K., Sada K. (2002) Mol. Immunol. 38, 1229–1233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alvarez-Errico D., Lessmann E., Rivera J. (2009) Immunol. Rev. 232, 195–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Saitoh S., Arudchandran R., Manetz T. S., Zhang W., Sommers C. L., Love P. E., Rivera J., Samelson L. E. (2000) Immunity 12, 525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Malbec O., Malissen M., Isnardi I., Lesourne R., Mura A. M., Fridman W. H., Malissen B., Daëron M. (2004) J. Immunol. 173, 5086–5094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Iwaki S., Spicka J., Tkaczyk C., Jensen B. M., Furumoto Y., Charles N., Kovarova M., Rivera J., Horejsi V., Metcalfe D. D., Gilfillan A. M. (2008) Cell. Signal. 20, 195–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tkaczyk C., Horejsi V., Iwaki S., Draber P., Samelson L. E., Satterthwaite A. B., Nahm D. H., Metcalfe D. D., Gilfillan A. M. (2004) Blood 104, 207–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Volná P., Lebduska P., Dráberová L., Símová S., Heneberg P., Boubelík M., Bugajev V., Malissen B., Wilson B. S., Horejsí V., Malissen M., Dráber P. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 200, 1001–1013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhu M., Liu Y., Koonpaew S., Granillo O., Zhang W. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 200, 991–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kambayashi T., Okumura M., Baker R. G., Hsu C. J., Baumgart T., Zhang W., Koretzky G. A. (2010) Mol. Cell. Biol. 30, 4188–4196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim M. S., Rådinger M., Gilfillan A. M. (2008) Trends Immunol. 29, 493–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Deane J. A., Fruman D. A. (2004) Annu. Rev. Immunol. 22, 563–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Vanhaesebroeck B., Ali K., Bilancio A., Geering B., Foukas L. C. (2005) Trends Biochem. Sci. 30, 194–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ali K., Bilancio A., Thomas M., Pearce W., Gilfillan A. M., Tkaczyk C., Kuehn N., Gray A., Giddings J., Peskett E., Fox R., Bruce I., Walker C., Sawyer C., Okkenhaug K., Finan P., Vanhaesebroeck B. (2004) Nature 431, 1007–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ali K., Camps M., Pearce W. P., Ji H., Rückle T., Kuehn N., Pasquali C., Chabert C., Rommel C., Vanhaesebroeck B. (2008) J. Immunol. 180, 2538–2544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Laffargue M., Calvez R., Finan P., Trifilieff A., Barbier M., Altruda F., Hirsch E., Wymann M. P. (2002) Immunity 16, 441–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hata D., Kawakami Y., Inagaki N., Lantz C. S., Kitamura T., Khan W. N., Maeda-Yamamoto M., Miura T., Han W., Hartman S. E., Yao L., Nagai H., Goldfeld A. E., Alt F. W., Galli S. J., Witte O. N., Kawakami T. (1998) J. Exp. Med. 187, 1235–1247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Liu Y., Zhu M., Nishida K., Hirano T., Zhang W. (2007) J. Exp. Med. 204, 93–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Olivera A., Mizugishi K., Tikhonova A., Ciaccia L., Odom S., Proia R. L., Rivera J. (2007) Immunity 26, 287–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Oskeritzian C. A., Alvarez S. E., Hait N. C., Price M. M., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2008) Blood 111, 4193–4200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Pushparaj P. N., Manikandan J., Tay H. K., H'ng S. C., Kumar S. D., Pfeilschifter J., Huwiler A., Melendez A. J. (2009) J. Immunol. 183, 221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jolly P. S., Bektas M., Olivera A., Gonzalez-Espinosa C., Proia R. L., Rivera J., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2004) J. Exp. Med. 199, 959–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Oskeritzian C. A., Price M. M., Hait N. C., Kapitonov D., Falanga Y. T., Morales J. K., Ryan J. J., Milstien S., Spiegel S. (2010) J. Exp. Med. 207, 465–474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Parekh A. B., Putney J. W., Jr. (2005) Physiol. Rev. 85, 757–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Roos J., DiGregorio P. J., Yeromin A. V., Ohlsen K., Lioudyno M., Zhang S., Safrina O., Kozak J. A., Wagner S. L., Cahalan M. D., Veliçelebi G., Stauderman K. A. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 169, 435–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Liou J., Kim M. L., Heo W. D., Jones J. T., Myers J. W., Ferrell J. E., Jr., Meyer T. (2005) Curr. Biol. 15, 1235–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Prakriya M., Feske S., Gwack Y., Srikanth S., Rao A., Hogan P. G. (2006) Nature 443, 230–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Feske S., Gwack Y., Prakriya M., Srikanth S., Puppel S. H., Tanasa B., Hogan P. G., Lewis R. S., Daly M., Rao A. (2006) Nature 441, 179–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Vig M., Peinelt C., Beck A., Koomoa D. L., Rabah D., Koblan-Huberson M., Kraft S., Turner H., Fleig A., Penner R., Kinet J. P. (2006) Science 312, 1220–1223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Yeromin A. V., Zhang S. L., Jiang W., Yu Y., Safrina O., Cahalan M. D. (2006) Nature 443, 226–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Baba Y., Nishida K., Fujii Y., Hirano T., Hikida M., Kurosaki T. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 81–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Vig M., DeHaven W. I., Bird G. S., Billingsley J. M., Wang H., Rao P. E., Hutchings A. B., Jouvin M. H., Putney J. W., Kinet J. P. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 89–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Chang W. C., Di Capite J., Singaravelu K., Nelson C., Halse V., Parekh A. B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 4622–4631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ng S. W., Nelson C., Parekh A. B. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 24767–24772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Nakata K., Yoshimaru T., Suzuki Y., Inoue T., Ra C., Yakura H., Mizuno K. (2008) J. Immunol. 181, 5414–5424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. McPherson V. A., Sharma N., Everingham S., Smith J., Zhu H. H., Feng G. S., Craig A. W. (2009) J. Immunol. 183, 4940–4947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Akimoto M., Mishra K., Lim K. T., Tani N., Hisanaga S. I., Katagiri T., Elson A., Mizuno K., Yakura H. (2009) Scand. J. Immunol. 69, 401–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Furumoto Y., Brooks S., Olivera A., Takagi Y., Miyagishi M., Taira K., Casellas R., Beaven M. A., Gilfillan A. M., Rivera J. (2006) J. Immunol. 176, 5167–5171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bansal G., Xie Z., Rao S., Nocka K. H., Druey K. M. (2008) Nat. Immunol. 9, 73–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhu M., Rhee I., Liu Y., Zhang W. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 18408–18413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Vennekens R., Olausson J., Meissner M., Bloch W., Mathar I., Philipp S. E., Schmitz F., Weissgerber P., Nilius B., Flockerzi V., Freichel M. (2007) Nat. Immunol. 8, 312–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Melendez A. J., Harnett M. M., Pushparaj P. N., Wong W. S., Tay H. K., McSharry C. P., Harnett W. (2007) Nat. Med. 13, 1375–1381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Katz H. R. (2002) Curr. Opin. Immunol. 14, 698–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Daëron M., Jaeger S., Du Pasquier L., Vivier E. (2008) Immunol. Rev. 224, 11–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Daëron M., Malbec O., Latour S., Arock M., Fridman W. H. (1995) J. Clin. Invest. 95, 577–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Uehara T., Bléry M., Kang D. W., Chen C. C., Ho L. H., Gartland G. L., Liu F. T., Vivier E., Cooper M. D., Kubagawa H. (2001) J. Clin. Invest. 108, 1041–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Katz H. R., Vivier E., Castells M. C., McCormick M. J., Chambers J. M., Austen K. F. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 10809–10814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yotsumoto K., Okoshi Y., Shibuya K., Yamazaki S., Tahara-Hanaoka S., Honda S., Osawa M., Kuroiwa A., Matsuda Y., Tenen D. G., Iwama A., Nakauchi H., Shibuya A. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 198, 223–233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Abramson J., Xu R., Pecht I. (2002) Mol. Immunol. 38, 1307–1313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Liénard H., Bruhns P., Malbec O., Fridman W. H., Daëron M. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32493–32499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Hitomi K., Tahara-Hanaoka S., Someya S., Fujiki A., Tada H., Sugiyama T., Shibayama S., Shibuya K., Shibuya A. (2010) Nat. Immunol. 11, 601–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Honigberg L. A., Smith A. M., Sirisawad M., Verner E., Loury D., Chang B., Li S., Pan Z., Thamm D. H., Miller R. A., Buggy J. J. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13075–13080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Zhu D., Kepley C. L., Zhang M., Zhang K., Saxon A. (2002) Nat. Med. 8, 518–521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Zhu D., Kepley C. L., Zhang K., Terada T., Yamada T., Saxon A. (2005) Nat. Med. 11, 446–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Tam S. W., Demissie S., Thomas D., Daëron M. (2004) Allergy 59, 772–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Jackman J., Chen Y., Huang A., Moffat B., Scheer J. M., Leong S. R., Lee W. P., Zhang J., Sharma N., Lu Y., Iyer S., Shields R. L., Chiang N., Bauer M. C., Wadley D., Roose-Girma M., Vandlen R., Yansura D. G., Wu Y., Wu L. C. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 20850–20859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Saxon A., Kepley C., Zhang K. (2008) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 121, 320–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]