Abstract

Fundamental aspects of interactions of the Dengue virus type 3 full-length polymerase with the single-stranded and double-stranded RNA and DNA have been quantitatively addressed. The polymerase exists as a monomer with an elongated shape in solution. In the absence of magnesium, the total site size of the polymerase-ssRNA complex is 26 ± 2 nucleotides. In the presence of Mg2+, the site size increases to 29 ± 2 nucleotides, indicating that magnesium affects the enzyme global conformation. The enzyme shows a preference for the homopyrimidine ssRNAs. Positive cooperativity in the binding to homopurine ssRNAs indicates that the type of nucleic acid base dramatically affects the enzyme orientation in the complex. Both the intrinsic affinity and the cooperative interactions are accompanied by a net ion release. The polymerase binds the dsDNA with an affinity comparable with the ssRNAs affinity, indicating that the binding site has an open conformation in solution. The lack of detectable dsRNA or dsRNA-DNA hybrid affinities indicates that the entry to the binding site is specific for the sugar-phosphate backbone and/or conformation of the duplex.

Keywords: E. coli Dengue Polymerase, Dengue NS5 Protein, Biophysics, Fluorescence, RNA Polymerase, RNA-Protein Interaction, Fluorescence Titrations, Thermodynamics

Introduction

The dengue virus (DENV)2 is a member of the Flaviviridae family and the etiological agent of dengue fever, a disease affecting worldwide ∼100 million people each year (1–5). The Flaviviridae family includes such human pathogens as tick-borne encephalitis virus, hepatitis C virus, West Nile virus, yellow fever virus, and Japanese encephalitis virus (1–5). The dengue virus exists in four distinct types, DENV1, -2, -3, and -4, which show ∼60% genomic sequence identity (1). The dengue fever often develops into the dengue hemorrhagic fever, an acute form of the disease, possibly as a result of sequential infection with different types of the virus. It is characterized by a significant mortality, particularly for individuals with a weakened or undeveloped immune system. The small, 10.7-kbp positive strand RNA genome of the dengue virus encodes only 10 proteins: three structural proteins (capsid, premembrane, and envelope proteins) and seven nonstructural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, and NS5 proteins) (3, 6–8). The entire viral genome is translated as a single polyprotein, subsequently cleaved by viral and cellular proteases into functional entities.

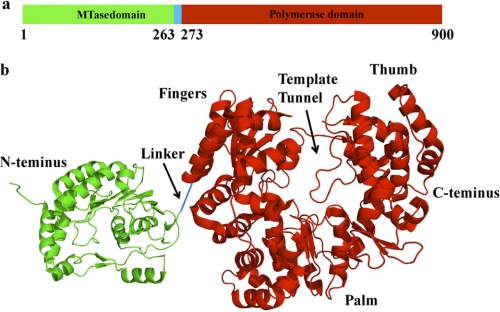

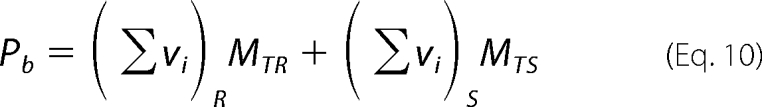

The NS5 protein is the viral replicative RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (1, 3, 6–8). The primary structure of the full-length polymerase encompasses 900 amino acids (i.e. it is the largest of the nonstructural proteins of the dengue virus) (6–10). The enzyme is built of two functional domains (6–10). The N-terminal domain includes the first 263 amino acids. It functions as a methyltransferase (MTase), whose activity is necessary for viral RNA recognition by the host cell translational apparatus. Correspondingly, amino acids ∼273–906 form the polymerase domain, containing the active site of the RNA synthesis (Fig. 1a) (6–8). The crystal structures of the isolated N-terminal and polymerase domains have been determined up to 1.8–2.8 and 1.85 Å resolutions, respectively, providing crucial insights about their topologies (8–10). The polymerase domain has a tertiary structure with palm, thumb, and finger subdomains, typical for the RNA and DNA polymerases, with the catalytic site containing conserved aspartic residues and coordinated magnesium cations, which points to a common, two-metal ion catalytic mechanism of the nucleotide incorporation. The active site is encircled by several loops, predominantly protruding from the thumb subdomain, resulting in a “tunnel-like” template-binding site (Fig. 1b) (9). The domain also possesses two zinc-binding pockets, although their functional role is at present not clear. Nevertheless, the structure of the full-length DENV polymerase is still unknown.

FIGURE 1.

a, the domain structure of the DENV phenotype 3, full-length polymerase used in this work within the primary structure of the enzyme. The MTase and polymerase domains are colored green and red, respectively. The linker is colored blue. b, the corresponding crystal structures of the MTase and polymerase domains with the schematic linker connecting the domains in the full-length enzyme (9, 10). The structures have been generated using data from the Protein Data Bank, under the codes 2XBM and 2J7U, for the MTase and polymerase domains, respectively, using PyMOL (Schrodinger, LLC, New York). In the case of the polymerase domain, typical polymerase folds, fingers, palm, and thumb, as well as the location of the proposed nucleic acid binding site, are labeled in b.

Analogously to other viral polymerases of the Flaviviridae family, the DENV polymerase can catalyze de novo synthesis of RNA (i.e. synthesis of the complementary RNA strand), which does not require the primer, although it requires the presence of the GTP cofactor, whose binding site is located on the palm subdomain (6, 7, 10–14). Thus, the interactions with the ssRNA are sufficient to initiate and continue the nucleic acid synthesis. Both the isolated polymerase domain and the full-length enzyme can catalyze the RNA synthesis in vitro (9, 13). Nevertheless, the isolated polymerase domain shows decreased enzymatic activity (9).

Interactions of the dengue RNA polymerase with the ssRNA play a vital role in the function of the enzyme as one of the major elements that determine the degree of fidelity of the RNA synthesis (15–17). Despite its paramount importance for understanding the RNA recognition process by the full-length dengue RNA polymerase, the direct and quantitative analyses of the enzyme interactions with the nucleic acid have not been addressed. The fundamental aspects of these interactions, like stoichiometries (site size of the DENV polymerase-ssRNA complex (i.e. the number of nucleotides occluded by the protein in the complex)), energetics of intrinsic affinities, cooperativities, and base specificity in the RNA recognition process, are unknown. Nothing is known about the effect of solution conditions on the energetics of the complex formation. Little is known about the role of the nucleic acid conformation in engaging the tunnel-like, encircled template-binding site, which is proposed to accommodate only the single-stranded conformation of the RNA (9). These characteristics constitute the essential framework for addressing any specificity of the polymerase activities and the reference points for the potential behavior of the polymerase in the nucleic acid synthesis.

In this paper, we report the first quantitative analyses of the full-length DENV polymerase interactions with the single-stranded and double-stranded RNA and DNA. We establish that, in solution, in the absence of magnesium, the enzyme occludes 26 ± 2 nucleotides. Binding of Mg2+ to the enzyme affects its global conformation and increases the site size of the complex to 29 ± 2 nucleotides. The polymerase binds the homopurine polymers with a significant positive cooperativity, indicating that the type of base affects the enzyme orientation in the complex with the nucleic acid. The DENV polymerase binds the dsDNA with affinity comparable with the ssRNA, indicating that the proposed tunnel-like binding/active site is in open conformation in solution.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Buffers

All solutions were made with distilled and deionized >18-megaohm (Milli-Q Plus) water. All chemicals were reagent grade. Buffer T5 contained 50 mm Tris adjusted to pH 7.6 with HCl at a given temperature, 100 mm NaCl, 1 mm DTT, and 10% glycerol (w/v). Temperatures and concentrations of salts in the buffer are indicated throughout.

Expression and Purification of the Dengue Virus Full-length RNA Polymerase

Full-length DENV (type 3) NS5 polymerase with a C-terminal hexahistidine tag was expressed in BL21-CodonPlus-RIL Escherichia coli cells. The cells were grown at 37 °C in Luria Broth (LB) containing 34 μg/ml kanamycin and 30 mg/ml chloramphenicol to an absorbance of 0.7 at 600 nm. The expression of the protein was induced by adding 1.5 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside, and the cell growth was continued overnight at 18 °C. The cells were suspended in the lysis buffer (100 mm sodium phosphate, pH 8.0, 0.5 m NaCl, 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 tablet of EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche Applied Science) and subjected to sonication. After centrifugation, the protein in the soluble fraction was purified by Talon metal affinity chromatography (Clontech). The polymerase was eluted with a 5–100 mm gradient of imidazole in 100 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 0.5 m NaCl, and 2 mm β-mercaptoethanol. The fractions containing the polymerase were collected and concentrated to 1–2 ml, using an Ultrafree centrifugal filter device (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Subsequently, the sample was loaded on a Superdex 200 gel column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.4 m NaCl, and 2 mm DTT. The DENV polymerase elutes as a monomer. The protein was >99% pure as judged by polyacrylamide electrophoresis with Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining. The concentration of the DENV polymerase was spectrophotometrically determined with the extinction coefficient ϵ280 = 21.2198 × 104 cm−1 M−1 (monomer) obtained using an approach based on the method of Edelhoch (18, 19).

Nucleic Acids

Nucleic acid oligomers and polymers have been purchased from Midland Certified Reagents (Midland, TX). Nucleic acids were at least ∼1000 nucleotides long as determined using the sedimentation velocity method (20). The concentrations of the nucleic acids were determined using extinction coefficients: poly(dA), ϵ257 = 10,000 cm−1 m−1; poly(A), ϵ260 = 10,300 cm−1 m−1; poly(C), ϵ267 = 6.5 × 103 m−1 cm−1; and poly(U), ϵ260 = 9,200 cm−1 m−1 (nucleotide) (21). The etheno-derivatives of poly(A) (poly(ϵA)) were obtained by modification with chloroacetaldehyde (22–26). This modification goes to completion and provides a fluorescent derivative of the nucleic acid. The concentration of poly(ϵA) was determined using the extinction coefficient, ϵ257 = 3700 cm−1 m−1 (nucleotide) (22–26). The dsRNA and dsDNA 30-mer were random sequence oligomers containing ∼60% of GC base pairs with the sequence GGAGUCCACGACUUCGCAGGCUCGUUACGU, with T replacing U in the case of the DNA. The double-stranded conformations of the nucleic acids have been obtained by mixing oligomers with the complementary strands, heating the sample to 95 °C, and slowly cooling for a period of ∼4 h. The integrity of the dsRNA and dsDNA 30-mer has been tested using UV melting and analytical ultracentrifugation methods (27–29).

Fluorescence Measurements

Steady-state fluorescence titrations were performed using an ISS PC1 spectrofluorometer (ISS, Urbana, IL). In order to avoid possible artifacts, due to the fluorescence anisotropy of the sample, polarizers were placed in excitation and emission channels and set at 90 and 55° (magic angle), respectively. The DENV polymerase binding was followed by monitoring the fluorescence of the etheno-derivative of adenosine homopolymer poly(ϵA) (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm). Computer fits were performed using KaleidaGraph software (Synergy Software, PA) and Mathematica (Wolfram Research, IL). The relative fluorescence increase of the nucleic acid, ΔF, upon binding the DENV polymerase is defined as follows, ΔFobs = (Fi − Fo)/Fo, where Fi is the fluorescence of the nucleic acid solution at a given titration point i, and Fo is the initial fluorescence of the sample (30–38). Both Fo and Fi are corrected for the background fluorescence, including residual protein fluorescence at the applied excitation wavelength (30–38).

Determination of Thermodynamically Quantitative Binding Isotherms of the DENV Polymerase-ssDNA Complexes

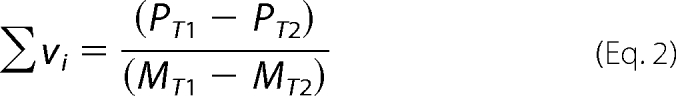

To obtain quantitative estimates of the total average binding density, Σvi (number of bound polymerase molecules per nucleotide of the single-stranded nucleic acid) and the free protein concentration, PF, independent of any assumption about the relationship between the observed spectroscopic signal and Σvi, we applied an approach previously described by us (30–38). Briefly, each different possible “i” complex of the DENV RNA polymerase with the ssDNA contributes to the experimentally observed relative fluorescence increase, ΔFobs. Thus, ΔFobs is functionally related to Σvi by Equation 1,

where ΔFi is the molecular parameter characterizing the maximum fluorescence increase of the nucleic acid with the DENV polymerase bound in complex i. The same value of ΔFobs, obtained at, for example, two different total nucleic acid concentrations, MT1 and MT2, indicates the same physical state of the nucleic acid (i.e. the total average binding density, Σvi, and the free DENV polymerase concentration, PF, must be the same). The values of Σvi and PF are then related to the known total protein concentrations, PT1 and PT2, and the known total nucleic acid concentrations, MT1 and MT2, at the same value of ΔFobs, by the following,

|

|

Analytical Ultracentrifugation Measurements

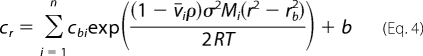

Analytical ultracentrifugation experiments were performed with an Optima XL-A analytical ultracentrifuge (Beckman Inc., Palo Alto, CA), as we described previously (39–43). Sedimentation equilibrium scans were collected at the absorption band of the DENV polymerase (280 nm). The sedimentation was considered to be at equilibrium when consecutive scans, separated by time intervals of 8 h, did not indicate any changes. For the n-component system, the total concentration at radial position r, cr, is defined by Equation 4,

|

where cbi, v̄, and Mi are the concentration at the bottom of the cell, partial specific volume, and molecular weight of the i component, respectively, ρ is the density of the solution, σ is the angular velocity, and b is the base-line error term (39–44). Equilibrium sedimentation profiles were fitted to Equation 4 with Mi and b as fitting parameters (39–44).

Sedimentation velocity scans were collected at the absorption band of the DENV polymerase at 280 nm. Time derivative analyses of the sedimentation scans were performed with the software supplied by the manufacturer using averages of 8–15 scans for each concentration. The reported values of sedimentation coefficients were corrected to s20,w for solvent viscosity and temperature to standard conditions (44).

RESULTS

The Oligomeric State of the Full-length DENV RNA Polymerase in Solution

The schematic primary structure of the full-length DENV RNA polymerase is shown in Fig. 1a. The protein molecule contains 900 amino acid residues, with monomer molecular mass of ∼104,000 kDa. The amino acids corresponding to the methyltransferase and polymerase domains, respectively, are marked by different colors. Fig. 1b shows the crystal structures of the isolated MTase and polymerase domains of the enzyme, schematically connected through the 10-amino acid linker, as in the full-length enzyme (9, 10). In the case of the polymerase domain, modeling analysis suggests that the nucleic acid occupies the tunnel-like binding site on the domain, which spans the length of ∼5–7 nucleotides (9). As discussed below, the total site size of the full-length DENV polymerase-ssRNA complex is much larger than ∼5 -7 nucleotides, indicating significantly more complex interactions.

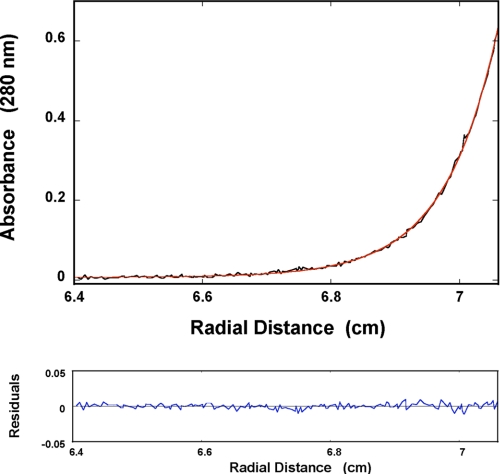

An example of the sedimentation equilibrium profile of the DENV RNA polymerase recorded at the protein absorption band (280 nm) is shown in Fig. 2a. The protein concentration is 1.41 × 10−6 m. The solid red line is the nonlinear least squares fit, using the single exponential function defined by Equation 4 (see “Experimental Procedures”). The fit provides an excellent description of the experimental curve indicating the presence of a single species with molecular weight of 101,000 ± 6000. Adding additional exponents does not improve the statistics of the fit (data not shown). The same equilibrium sedimentation experiments have been performed at different protein concentrations, providing molecular weights ranging between ∼101,000 and 106,000 (data not shown). These results indicate that the full-length DENV polymerase exists as a monomer in the concentration range studied in this work.

FIGURE 2.

Sedimentation equilibrium concentration profile of the DENV polymerase in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2. The concentration of the protein is 1.41 × 10−6 m (monomer). The profile has been recorded at 280 nm and at 12,000 rpm. The solid red line is the nonlinear least squares fit to a single exponential function (Equation 4), with a single species having a molecular weight of 101,000 ± 6000. The bottom panel shows the residuals of the fit.

Global Conformation of the DENV Polymerase in Solution

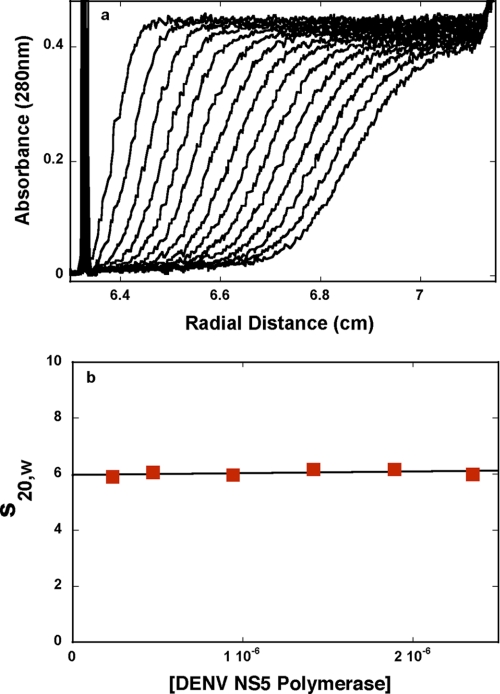

The sedimentation velocity profiles (monitored at 280 nm) of the DENV polymerase in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C) are shown in Fig. 3a. The concentration of the protein is 1.89 × 10−6 m (monomer). Inspection of the profiles clearly shows that there is a single moving boundary, indicating the presence of a single molecular species (41, 42, 44). To obtain the sedimentation coefficient of the protein, s20,w, the sedimentation velocity scans have been analyzed using the time derivative approach (45, 46). The dependence of s20,w of the DENV polymerase upon the protein concentration is shown in Fig. 3b. The value of s20,w shows very little dependence upon [DENV polymerase]. Extrapolation of the plot to [DENV polymerase] = 0 provides s20,w0 = 6.0 ± 0.08 S (Fig. 3b).

FIGURE 3.

a, sedimentation velocity absorption profiles at 280 nm of the DENV NS5 polymerase in buffer T5 (pH 7. 6, 10 °C). The concentration of the protein is 1.89 × 10−6 m; 40,000 rpm. b, dependence of the DENV polymerase sedimentation coefficient, s20,w, upon the protein concentration in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C).

Having the experimental values of s20,w0, one can address the hydrodynamic shape of the free DENV polymerase monomer in solution (44). Independently of any hydrodynamic models, the sedimentation coefficient is related to the average translational frictional coefficient, f̄p, of the protein by the following,

|

where v̄ is the partial specific volume of the protein, M is the molecular weight of the anhydrous DENV RNA polymerase, ρ is the density of the solvent in g/ml, and NA is Avogadro's number. The average translational frictional coefficient ratio, F, is defined, as follows (44),

|

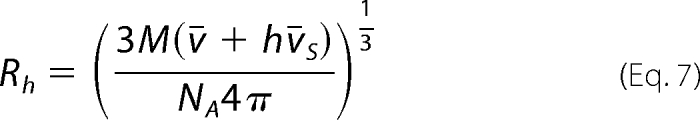

where Rh is the hydrodynamic radius of the corresponding hydrated sphere, defined as follows,

|

where η is the viscosity of the solvent (poise), h is the degree of the protein hydration expressed as gH2O/gprotein, and v̄S is the partial specific volume of the solvent equal to the inverse of its density. The degree of hydration can be estimated by the method of Kuntz (47). For the DENV polymerase, it provides h ≈ 0.41 gH2O/gprotein. However, this value of h is calculated for the mixture of amino acids completely exposed to the solvent and represents the maximum possible value of the degree of hydration. Part of the amino acid residues will not be accessible to the solvent in the native structure of the protein. Thus, the value of h should be corrected for the part of residues in the native structure that is not accessible to the solvent. The correction factor can be obtained in a systematic way by comparing Kuntz's values for a series of proteins with the degree of hydration of the folded structure of the same protein (47–49). In the case of the DENV polymerase, the correction factor amounts to ∼0.91; thus, ∼91% of the maximum value of h is associated with the folded protein molecule. The corrected value of the degree of hydration for the DENV polymerase is then h = 0.37 gH2O/gprotein. The value of the sedimentation coefficient, s20,w0 = 6.0 ± 0.08 S, of the DENV polymerase provides F = 1.16 ± 0.01, indicating that the DENV polymerase, in solution, has an elongated structure (44).

The Total Site Size of the DENV RNA Polymerase-ssRNA Complex in the Absence of Magnesium

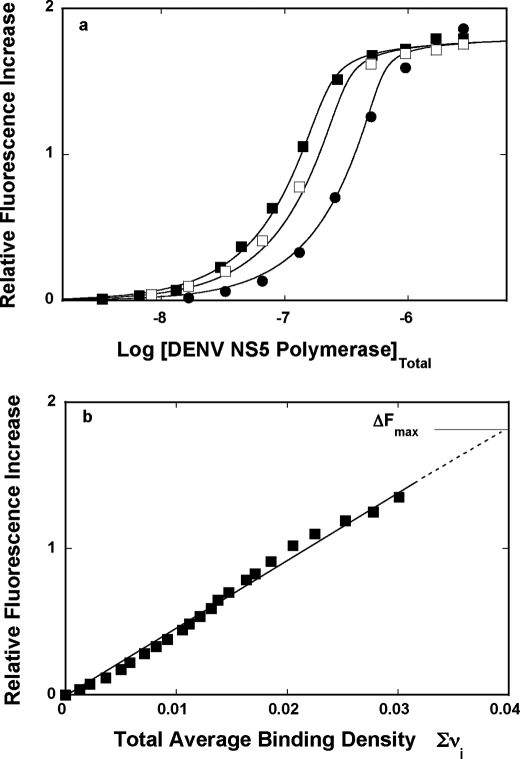

In the course of our studies, we have found that formation of the complex between the DENV polymerase and the etheno-derivative of the adenosine homopolymer, poly(ϵA), causes a strong nucleic acid fluorescence increase, providing an excellent signal required to perform high resolution measurements and to address the fundamental problem of the stoichiometry and mechanism of the enzyme interactions with the nucleic acids (see “Experimental Procedures”) (30–38). Fluorescence titrations of the poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase at three different nucleic acid concentrations, in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), are shown in Fig. 4a. At a higher nucleic acid concentration, the titration curves shift toward higher protein concentrations, resulting from the fact that, at high nucleic acid concentration, more protein is required to obtain the same total binding density, Σvi. The applied poly(ϵA) concentrations provide separation of the titration curves up to the relative fluorescence increase of ∼1.5.

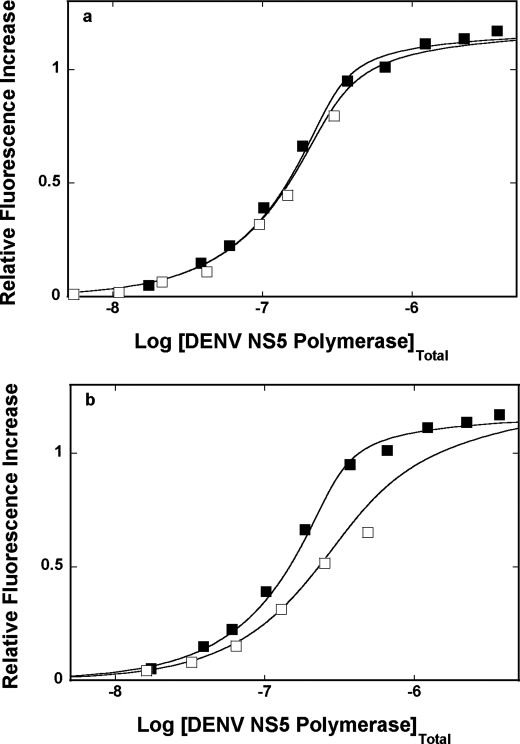

FIGURE 4.

a, fluorescence titrations of the poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C) at three different nucleic acid concentrations: 5.99 × 10−6 m (■), 8.55 × 10−6 m (□), and 1.71 × 10−5 m (nucleotide) (●). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the titration curves, using the generalized McGhee-von Hippel isotherm, described by Equations 8–9 with the intrinsic binding constant, K = 4 × 106 m−1, cooperative interactions parameter, ω = 17, and maximum fluorescence increase, ΔFmax = 1.81. b, dependence of the relative fluorescence increase, ΔFobs, of poly(ϵA) upon the total average binding density, Σvi of the DENV polymerase (■). The solid line follows the experimental points and has no theoretical basis. The dashed line is the extrapolation of ΔFobs to its maximum value, ΔFmax = 1.81.

In order to obtain thermodynamic binding parameters, independent of any assumption about the relationship between the observed signal and the total average binding density, Σvi, the fluorescence titration curves, shown in Fig. 4a, have been analyzed, using the quantitative approach outlined under “Experimental Procedures” (30–38). Fig. 4b shows the dependence of the relative fluorescence increase of poly(ϵA), ΔFobs, as a function of Σvi of the DENV polymerase. Within experimental accuracy, the plot is linear, indicating that binding of the subsequent protein molecules induces similar changes of the nucleic acid fluorescence. Moreover, the linearity of the plot also indicates the lack of any detectable heterogeneity in the binding process (see “Discussion”). Although the plots in Fig. 4a show clear plateaus, the maximum change of the nucleic acid fluorescence, ΔFmax, has been additionally determined by adding nucleic acid to the sample containing highly concentrated stock solution of the enzyme (32–35). Extrapolation to the determined maximum fluorescence change, ΔFmax = 1.81 ± 0.03, provides the maximum average binding density of the complex, 0.039 ± 0.003. The reciprocal of this value is the site size of the complex (i.e. n = 1/0.039 = 26 ± 2 nucleotides) (30–33, 35–38, 50–52). Thus, the full-length DENV RNA polymerase occludes in the complex with the ssRNA of ∼26 nucleotides.

Statistical Thermodynamic Model of the DENV RNA Polymerase Binding to the ssRNA Polymers; Intrinsic Affinities and Cooperativities

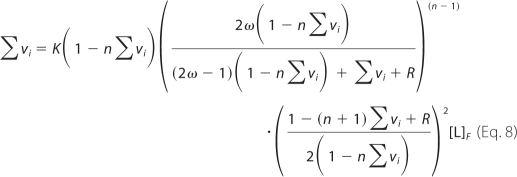

For association of a large protein ligand with a long homogeneous nucleic acid lattice, the McGhee-von Hippel model is the simplest statistical thermodynamic description for the binding process (50–52). The model takes into account the cooperativity of the protein association and the overlap of the potential binding sites. Although the original work provides two expressions for the noncooperative and cooperative binding, a single, generalized equation for the McGhee-von Hippel model, which can be applied to both cooperative and noncooperative binding systems, has been derived and is defined by the following (52),

|

where K is the intrinsic binding constant, n is the site size of the protein-nucleic acid complex, ω is the parameter characterizing the possible cooperative interactions, and r = ((1 − (n + 1)Σvi)2 + 4ωΣvi(1 − nΣvi))0.5 (55). The linearity of the plot of ΔFobs, as a function of Σvi (Fig. 4b) indicates that the observed relative fluorescence change, ΔFobs, is then described by the following,

|

where ΔFmax is the maximum observed relative molar fluorescence increase (30–33). The value of the total site size of the DENV polymerase-ssRNA complex, n ≈ 26, is known (see above). The value of ΔFmax can be estimated from the parental fluorescence titration curves, as shown in Fig. 4a. Thus, there are two independent parameters, K and ω, which must be determined. The solid lines in Fig. 4a are nonlinear least squares fits of the titration curves using Equations 8–9, which provide an excellent description of the experimental data. In the examined solution conditions, the intrinsic binding constant K is ∼4 × 106 m−1. The value of the cooperative interaction parameter, ω ≈ 17, indicates that binding of the DENV polymerase to the ssRNA, poly(ϵA), is characterized by a significant positive cooperativity. Nevertheless, ω strongly depends upon the base type of the nucleic acid and salt concentration (see below).

Salt Effect On the DENV RNA Polymerase-ssRNA Interactions

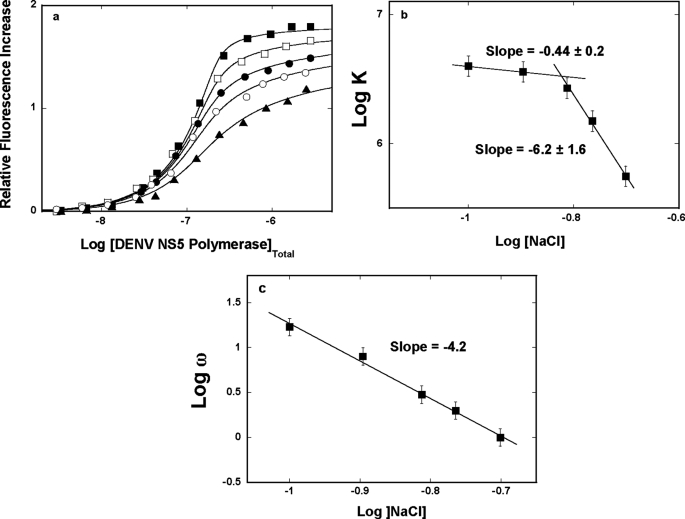

Fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C) containing different NaCl concentrations are shown in Fig. 5a. As the salt concentration increases, there is a decrease of the maximum fluorescence increase at saturation, ΔFmax, from ∼1.8 at 100 mm to ∼1.5 at 199 mm NaCl, indicating only a modest change of the nucleic acid structure in the complex (see “Discussion”). The titration curves have been analyzed using the quantitative approach outlined under “Experimental Procedures,” indicating that the site size of the complex remains at n = 26 ± 2 nucleotides in all examined solution conditions (30–38). The solid lines in Fig. 5a are nonlinear least squares fits to Equations 8–9 with two fitting parameters, K and ω.

FIGURE 5.

a, fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing different NaCl concentrations: 100 mm (■); 127 mm (□); 154 mm (●); 172 mm (○); 199 mm (▴). The concentration of poly(ϵA) is 5.99 × 10−6 m (nucleotide). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the titration curves, using Equations 8–9, with K, ω, and ΔFmax: 4.0 × 106 m−1, 17, 1.81 (■); 3.3 × 106 m−1, 8, 1.77 (□); 2.7 × 106 m−1, 3, 1.73 (●); 1.5 × 106 m−1, 2, 1.67 (○); 5.8 × 105 m−1, 1, 1.54 (▴). b, the dependence of the logarithm of the intrinsic binding constant, K, upon the logarithm of NaCl (■). The solid lines are linear least squares fits of the low and high NaCl concentration regions of the plot, which provide the slopes ∂logK/∂log[NaCl] = −0.9 ± 0.2 and ∂logK/∂log[NaCl] = −6.2 ± 1.6, respectively. c, the dependence of the logarithm of the cooperative interactions parameter, ω, upon the logarithm of NaCl (□). The solid line is the linear least squares fit of the of the plot, which provides the slope ∂logω/∂log[NaCl] = −4.2 ± 0.8. Error bars, S.E.

The dependence of the logarithm of the intrinsic binding constant K upon the logarithm of NaCl concentrations (log-log plot) is shown in Fig. 5b (53, 54). Although, in general, the increase of the salt concentration decreases the value of K, the plot is clearly nonlinear in the examined salt concentration range. At the low NaCl concentrations, the plot is characterized by the slope, ∂logK/∂log[NaCl] = −0.4 ± 0.2, whereas in the high NaCl concentration range, ∂logK/∂log[NaCl] = −6.2 ± 1.6. The nonlinear character of the log-log plot strongly suggests that the observed ion exchange includes progressive saturation of the ion binding site(s) in the protein and/or protein-nucleic acid complex (see below). The value of the slope in the high [NaCl] range indicates that there is a maximum net release of ∼6 ions upon complex formation.

The dependence of the logarithm of the cooperative interactions parameter, ω, upon the logarithm of NaCl concentration is shown in Fig. 5c. The values of ω strongly decrease with the increasing salt concentration. However, unlike the salt effect on the intrinsic binding constant (Fig. 5b), the plot in Fig. 5c is linear in the examined salt concentration range and characterized by the slope, ∂logω/∂log[NaCl] = −4.2 ± 1.2. Thus, the value of the slope indicates that there is a net release of ∼4 ions as a result of cooperative interactions between the bound DENV polymerase molecules (see “Discussion”).

Magnesium Effect on the DENV RNA Polymerase-ssRNA Interactions; Total Site Size of the DENV RNA Polymerase-ssRNA Complex

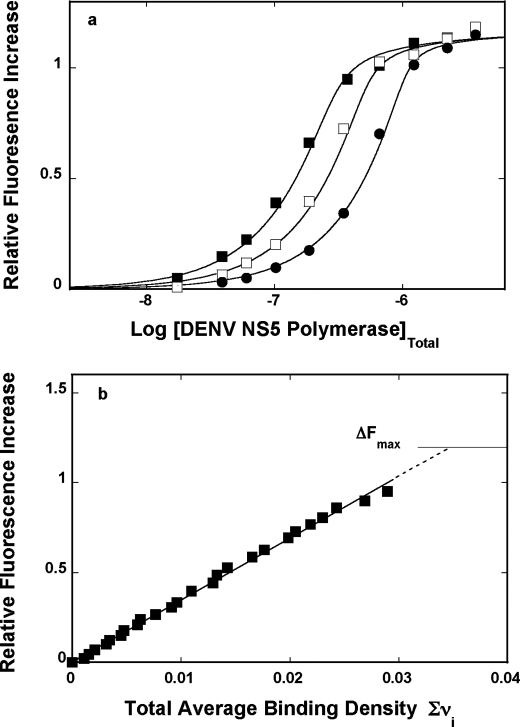

Magnesium cations are absolutely necessary for catalytic activity of the DENV RNA polymerase (13). Moreover, binding of Mg2+ cations also play a structural role in several well studied polymerases (15). Fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase at three different poly(ϵA) concentrations, in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C) containing 1 mm MgCl2, are shown in Fig. 6a. The applied poly(ϵA) concentrations provide separation of the titration curves up to the relative fluorescence increase of ∼0.9. Fig. 6b shows the dependence of the relative fluorescence increase of poly(ϵA), ΔFobs, as a function of Σvi of the DENV polymerase on the nucleic acid. Within experimental accuracy, the plot is linear. Extrapolation to the maximum fluorescence change, ΔFmax = 1.2 ± 0.02, provides the maximum average binding density of the complex, 0.034 ± 0.003, which indicates the site size of the formed complex, n = 29 ± 2 nucleotides (53–55). Although the effect is only slightly larger than the measurement error, these data indicate that, in the presence of Mg2+, the polymerase occludes a larger number of nucleotides than in the absence of magnesium (see “Discussion”). The solid lines in Fig. 6a are nonlinear least squares fits of the titration curves using Equations 8–9, which provide an excellent description of the experimental data.

FIGURE 6.

a, fluorescence titrations of the poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7. 6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2, at three different nucleic acid concentrations: 9.0 × 10−6 m (■), 1.71 × 10−5 m (□), and 3.4 × 10−5 m (nucleotide) (●). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the titration curves, using the generalized McGhee-von Hippel isotherm, described by Equations 8–9, with the intrinsic binding constant, K = 2.5 × 106 m−1, cooperative interactions parameter, ω = 14, and maximum fluorescence increase, ΔFmax = 1.19. b, dependence of the relative fluorescence increase, ΔFobs, of poly(ϵA) upon the total average binding density, Σvi of the DENV polymerase (■). The solid line follows the experimental points and has no theoretical basis. The dashed line is the extrapolation of ΔFobs to its maximum value, ΔFmax = 1.19.

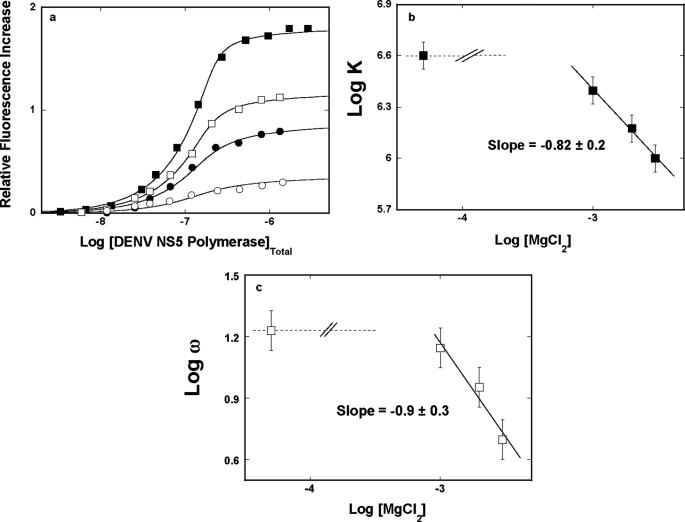

Fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase, in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing different MgCl2 concentrations, are shown in Fig. 7a. The effect of magnesium on the protein interactions with the nucleic acid is much more pronounced than that observed for the NaCl effect. As the magnesium concentration increases, the value of ΔFmax decreases from ∼1.8 in the absence of magnesium to ∼0.4 in the presence of 3 mm MgCl2, indicating a strong change of the nucleic acid conformation in the complex (see “Discussion”). Analysis of the titration curves has been performed as described above. The larger site size of n ≈ 29 is preserved at all examined MgCl2 concentrations (data not shown). The solid lines in Fig. 7a are nonlinear least squares fits to Equations 8–9, with the site size n = 29 and two fitting parameters, K and ω.

FIGURE 7.

a, fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7. 6, 10 °C), containing different MgCl2 concentrations: 0 (■), 1 mm (□), 2 mm (●), and 3 mm (○). The concentration of poly(ϵA) is 5.99 × 10−6 m (nucleotide). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the titration curves, using Equations 8–9, with K, ω, and ΔFmax: 4.0 × 106 m−1, 17, 1.81 (■); 2.5 × 106 m−1, 14, 1.19 (□); 1.5 × 106 m−1, 9, 0.90 (●); 1.0 × 106 m−1, 5, 0.38 (○). b, the dependence of the logarithm of the intrinsic binding constant, K, upon the logarithm of NaCl. The solid line is the linear least squares fit of the high MgCl2 concentration region of the plot, which provides the slopes ∂logK/∂log[MgCl2] = −0.8 ± 0.2. The dashed line indicates the slope of the plot, ∂logK/∂log[MgCl2], in the low magnesium concentration range. c, the dependence of the logarithm of the cooperative interactions parameter, ω, upon the logarithm of MgCl2. The solid line is the linear least squares fit of the high MgCl2 concentration region of the plot, which provides the slope ∂logω/∂log[MgCl2] = −0.9 ± 0.3. The dashed line indicates the slope of the plot, ∂logω/∂log[MgCl2], in the low magnesium concentration range. Error bars, S.E.

Fig. 7b shows the dependence of the logarithm of K upon the logarithm of [MgCl2]. Similar to the analogous effect of NaCl (Fig. 6b), the log-log plot is clearly nonlinear, although placed at a much lower salt concentration than NaCl. At low [MgCl2], the slope, ∂logK20/∂log[MgCl2] = ∼0 ± 0.2. Above ∼1 mm MgCl2, the affinity dramatically decreases, indicating that the intrinsic binding process is accompanied by a net ion release. At high magnesium concentrations, the linear part of the plot is characterized by the ∂logK/∂log[MgCl2] = −0.8 ± 0.2, indicating that a net release of ∼1 ion accompanied the formation of the intrinsic DENV polymerase-ssRNA interactions. Nevertheless, this value is significantly lower than the ∼6 obtained in the presence of NaCl (Fig. 5b) (see “Discussion”).

The dependence of the logarithm of the cooperative interactions parameter, ω, upon the logarithm of MgCl2 concentration is shown in Fig. 7c. The behavior of the plot is distinct from the analogous plot for NaCl (Fig. 5c). It is nonlinear in the examined MgCl2 concentration range. The initial part of the plot is characterized by the slope ∂logω/∂log[MgCl2] ∼0. Above 1 mm MgCl2, the values of ω strongly decrease, and the plot is characterized by the slope ∂logω/∂log[MgCl2] = −0.9 ± 0.3, indicating that a net release of ∼1 ion accompanies the engagement of the bound polymerase molecules in cooperative interactions. Similar to the intrinsic interactions, this value is significantly lower than the ∼4 obtained in the presence of NaCl (see “Discussion”).

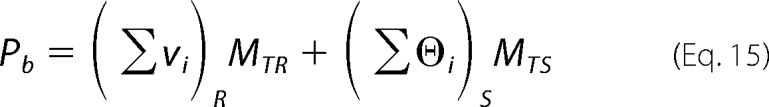

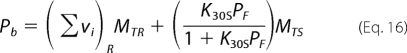

Base Specificity of DENV Polymerase-ssDNA Interactions; Lattice Competition Titrations Using the Macromolecular Competition Titration Method

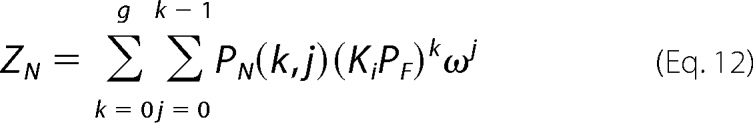

Quantitative determination of affinities of the DENV polymerase for unmodified ssRNAs, differing by the type of base, has been performed using the macromolecular competition titration method (31, 32, 36). The approach is based on the same thermodynamic arguments as applied to quantitative titrations of fluorescent nucleic acids with the protein (see “Experimental Procedures”). In the presence of the competing unmodified ssDNA oligomer, the protein binds to two different nucleic acids that are present in the solution, but the observed signal originates only from the fluorescent “reference” nucleic acid. In studies described in this work, we use, as a reference lattice, poly(ϵA), and the base specificity of the DENV polymerase has been examined using different ssRNA homopolymers, poly(A), poly(U), and poly(C). At a given titration point, i, the total concentration of the bound protein, Pb, is defined as follows (31, 32, 36, 38),

|

where (Σvi)R and (Σvi)S are the total average binding densities of the polymerase on the reference poly(ϵA) and the examined ssRNA polymer, respectively. MTR and MTS are the total concentrations of the reference and the unmodified ssRNA polymer, respectively. The concentration of the free protein, PF, is then as follows,

where PT is the known total concentration of the DENV polymerase.

It should be stressed that the McGhee-von Hippel model is equivalent to the combinatorial model as the length of the homogenous lattice approaches infinity (51). To overcome the problem of resorting to complex numerical calculations, one can apply a combined application of the generalized McGhee-von Hippel model, as defined by Equations 8 and 9, and the combinatorial theory for large ligand binding to a linear, homogeneous lattice (31, 32, 36, 38). In this approach, the ligand binding to the reference fluorescent nucleic acid is described by the generalized McGhee-von Hippel equation. Binding of the protein to the competing nonfluorescent lattice is described by the combinatorial theory. For a long enough lattice, the isotherm generated using the combinatorial theory, will be, within experimental accuracy, indistinguishable from the isotherm generated, using the generalized Equation 8. For instance, in the case of a protein like the DENV polymerase (n = 26 or 29), a lattice that can accommodate ≥30 protein molecules (∼1000 nucleotides) represents an “infinite” lattice for any practical purpose.

In the combinatorial theory, the partition function of the protein-nucleic acid system, ZS, is defined as follows (54),

|

where g is the maximum number of protein molecules that may bind to the finite nucleic acid lattice (for the nucleic acid lattice N residues long, g = N/n), ω is the cooperative interactions parameter, k is the number of ligand molecules bound, and j is the number of cooperative contacts between the k bound protein molecules in a particular configuration on the nucleic acid. The combinatorial factor PN (k, j) is the number of distinct ways that k protein molecules bind to a nucleic acid lattice with j cooperative contacts and is defined by the following.

|

The total average binding density, (Σvi)S, on the unmodified ssRNA polymer is then as follows.

|

The observed relative fluorescence increase, ΔFobs, is defined by Equation 7.

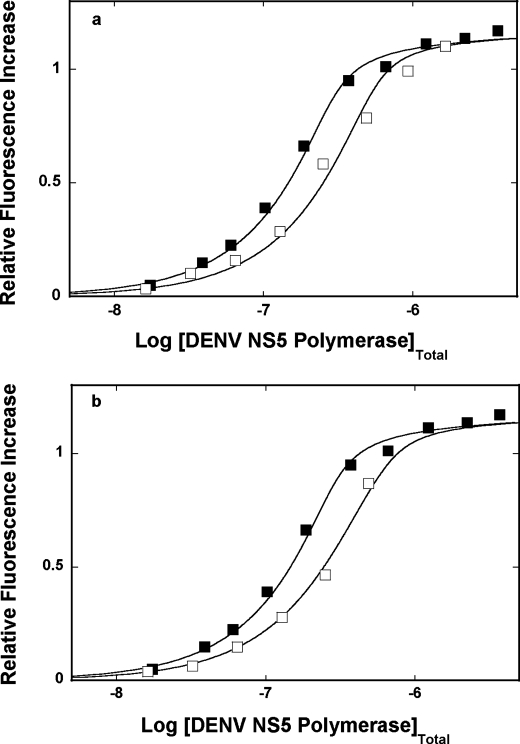

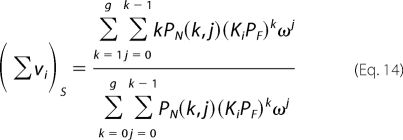

Fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2, in the presence of poly(C), are shown in Fig. 8a. For comparison, the titration curve of poly(ϵA) in the absence of the competing poly(C) is also included. In the presence of poly(C), the titration curve shifts toward high protein concentrations, indicating significant competition between poly(ϵA) and poly(C) for the DENV polymerase. Note that the competition curve covers ∼95% of the total titration curve. Moreover, because KR = 2.5 × 106 m−1, ω = 14, and ΔFmax = 1.2 are known from independent titration experiments (Fig. 4a), the solid lines in Fig. 8a are nonlinear least squares fits of the experimental titration curves, with only two parameters, KS and ωS, as fitting parameters, using Equations 10–14. Analogous fluorescence titration of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase, in the presence of poly(U), is shown in Fig. 8b, together with the titration curve of poly(ϵA) in the absence of the competing ssRNA. The binding constants for all examined ssRNA polymers, differing by the base type, are included in Table 1.

FIGURE 8.

a, fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λex = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7. 6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2, in the absence (■) and presence of the ssRNA homopolymer, of poly(C) (□). The concentration of poly(ϵA) is 9.41 × 10−6 m (nucleotide). The concentration of poly(C) is 1.34 × 10−5 m (nucleotide). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the binding titration curves, using Equations 8–14, with K = 2.5 × 106 m−1, ω = 14, and ΔFmax = 1.19 for poly(ϵA), and KS = 3 × 106 m−1 and ωS = 1 for poly(C). b, fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2, in the absence (■) and presence of the ssRNA homopolymer, of poly(U) (□). The concentration of poly(ϵA) is 9.41 × 10−6 m (nucleotide). The concentration of poly(U) is 1.92 × 10−5 m (nucleotide). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the binding titration curves, using Equations 8, 9, and 12–14, with the binding and spectroscopic parameters for poly(ϵA) as in a and KS = 9 × 105 m−1 and ωS = 1, for poly(U).

TABLE 1.

Intrinsic binding constant, K, cooperativity parameter, ω, and the site size, n, characterizing the binding of the DENV full-length polymerase to different nucleic acids, in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2

The binding parameters for the unmodified RNAs and DNAs were determined using the macromolecular competition titration method (for details, see “Results”). Errors are S.D. Values determined using 3–4 independent titration experiments.

| Parameter | poly(ϵA) | poly(A) | poly(U) | poly(C) | poly(dA) | dsRNAa 30-mer | dsDNAa 30-mer | dsRNA-DNAa 30-mer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K (m−1)b | (2.5 ± 0.5) × 106 | (3.0 ± 0.6) × 105 | (9 ± 1.8) × 105 | (1.3 ± 0.4) ×106 | (1.3 ± 0.4) × 105 | ≤1 × 105 | (4.3 ± 0.8) × 105 | ≤1 × 105 |

| ω | 14 ± 3 | 35 ± 9 | 1 ± 0.3 | 1 ± 0.3 | 37 ± 9 | |||

| n | 29 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 | 29 ± 2 |

a Macroscopic binding constant.

b Intrinsic binding constant.

The obtained value of the intrinsic binding constants, KS, for pyrimidine polymers are by a factor of ∼3 and ∼4 higher than the analogous parameter determined for the homopurine polymer, poly(A), although they are similar to the intrinsic binding constant obtained for the modified poly(ϵA). However, the most striking difference between the examined polymer ssRNAs is in the value of the cooperativity parameter, ω (Table 1). Whereas the binding of the DENV polymerase to the adenosine ssRNA polymers is characterized by a significant positive cooperativity, with ω in the range of 14–35, binding of the enzyme to the homopyrimidine RNAs is noncooperative and characterized by ω ≈ 1 (see “Discussion”).

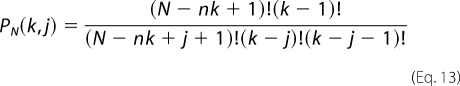

Lattice Competition Analysis of the DENV Polymerase-dsRNA, dsRNA-DNA Hybrid, and dsDNA Interactions

Next, we addressed the DENV polymerase affinity for the double-stranded conformations of both the RNA and the DNA. The studies have been performed with the 30-mers of the nucleic acids and using the macromolecular competition titration method (see “Experimental Procedures”). The length of the oligomers is dictated by the fact that the site size of the enzyme in the complex with the single-stranded nucleic acids is ∼29 nucleotides (see above). Thus, both 30-mers should bind only a single molecule of the polymerase, which greatly simplifies the binding analysis. The reference fluorescent nucleic acid is poly(ϵA) (31, 32, 36, 38). In the presence of the unmodified 30-mer, at a given titration point, i, the total concentration of the bound protein, Pb, is defined by an expression analogous to Equation 10, as follows,

|

where (Σvi)R and (Σϴi)S are the total average binding density of the DENV polymerase on the reference poly(ϵA) and the total average degree of binding on the examined unmodified 30-mer, respectively. MTR and MTS are the total concentrations of the reference and the unmodified 30-mer, respectively. For one DENV polymerase molecule binding to the 30-mer, Equation 15 is as follows,

|

where K30S is the macroscopic binding constant of the enzyme for the examined dsRNA or the dsDNA 30-mer. As discussed previously, ΔFobs is defined by Equation 7 (see above).

Fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2, in the presence of the dsRNA 30-mer, are shown in Fig. 9a. For comparison, the titration curve of poly(ϵA) in the absence of the competing dsRNA oligomer is also included. Because the system precipitates at high protein concentrations, only titration points where no precipitation has been observed are included in the plot. The titration curve hardly shifts in the presence of the oligomer, indicating the lack of detectable competition between poly(ϵA) and the dsRNA for the polymerase. Analogous competition fluorescence titrations have been performed in the presence of the dsRNA-DNA hybrid (data not shown). Similar to the dsRNA 30-mer, the hybrid hardly shifts the titration curves, indicating that the 30-mer very weakly competes with poly(ϵA) for the enzyme. These data indicate that the macroscopic binding constant, K30S, of the polymerase for the dsRNA or the dsRNA-DNA hybrid must be ≤1 × 105 m−1.

FIGURE 9.

a, fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7. 6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2, in the absence (■) and presence (□) of the dsRNA 30-mer (see “Experimental Procedures”). The concentration of poly(ϵA) is 9.41 × 10−6 m (nucleotide). The concentration of the dsRNA 30-mer is 1.44 × 10−5 m (oligomer). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the binding titration curves, using Equations 6, 7, 13, and 14, with K = 2.5 × 106 m−1, ω = 14, and ΔFmax = 1.19 for poly(ϵA) and KS ≤ 1 × 105 m−1 for the dsRNA oligomer. b, fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase (λex = 325 nm, λem = 410 nm) in buffer T5 (pH 7.6, 10 °C), containing 1 mm MgCl2, in the absence (■) and presence (□) of the dsDNA 30-mer (see “Experimental Procedures”). The concentration of poly(ϵA) is 9.41 × 10−6 m (nucleotide). The concentration of the dsDNA 30-mer is 1.0 × 10−5 m (oligomer). The solid lines are nonlinear least squares fits of the binding titration curves, using Equations 8, 9, 15, and 16, with K = 2.5 × 106 m−1, ω = 14, and ΔFmax = 1.19 for poly(ϵA) and KS = 8.5 × 105 m−1 for the dsDNA oligomer.

The situation is different in the case of the dsDNA. Fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the DENV polymerase, in the absence and presence of the dsDNA 30-mer, are shown in Fig. 9b. Although the DENV polymerase is an RNA enzyme, the observed shift of the titration curve, in the presence of the dsDNA, shows that the protein has significant affinity for the dsDNA. As pointed out above, because the system precipitates at high protein concentrations, only titration points, where no precipitation has been observed, are included in the plot. The solid lines in Fig. 9b are nonlinear least squares fits of the experimental titration curves, with a single fitting parameter, K30S, using Equations 8, 10, and 16, which provides K30S = 8.5 × 105 m−1 for the dsDNA (see “Discussion”).

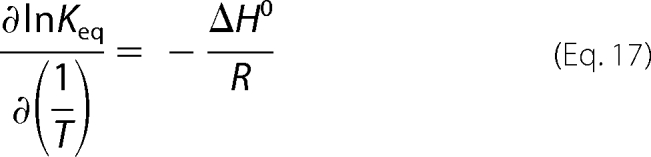

Temperature Effect on the DENV Polymerase Association with the ssRNA

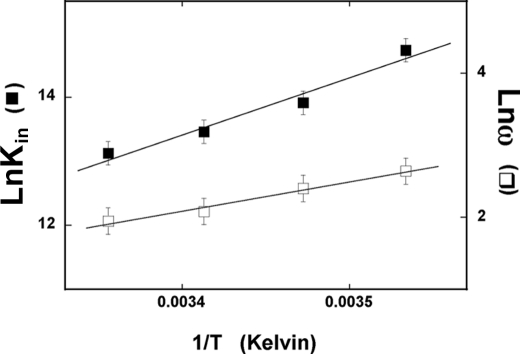

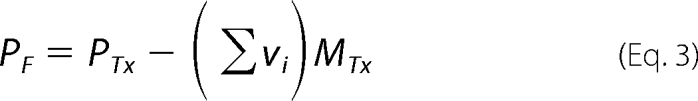

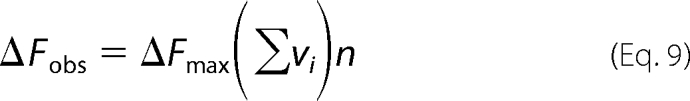

To further probe the nature of the DENV polymerase-ssRNA interactions, we examined the temperature effect on the energetics of the DENV polymerase binding to the ssRNA. Fluorescence titrations of poly(ϵA) with the enzyme have been performed in buffer T5 at several different temperatures (data not shown). The titration curves have been analyzed as described above (Fig. 4, a and b), using Equations 8 and 9. Fig. 10 shows the dependence of the natural logarithm of the binding constants, Kin and cooperativity parameter, ω, upon the reciprocal of the temperature (Kelvin). Within experimental accuracy, the plots are linear in the examined temperature range. Both the intrinsic binding constant and the cooperativity parameter, ω, strongly decrease with a temperature increase. The temperature dependence of an equilibrium constant, Keq, is described by van't Hoff's equation,

|

where Keq is an equilibrium constant characterizing a given equilibrium process, and ΔH0 is the corresponding enthalpy change. The intrinsic binding of the enzyme to the ssRNA and cooperative interactions between bound polymerase molecules are characterized by the apparent enthalpy changes, ΔHin0 = −17.8 ± 3 kcal/mol and ΔHcoop0 = −8.1 ± 2 kcal/mol, respectively. Using the thermodynamic relationship, ΔG0 = −RTlnKin and ΔG0 = −RTlnω, one obtains the corresponding apparent entropy changes as ΔSin0 = −91 ± 21 cal/mol degrees and ΔScoop0 = −34 ± 5 cal/mol degrees, respectively. The large difference between thermodynamic functions for the intrinsic binding and the cooperative interactions indicate that the processes of very different natures are observed. Nevertheless, both the intrinsic binding and cooperative interactions in the DENV polymerase association with the ssRNA are enthalpy-driven processes (see “Discussion”).

FIGURE 10.

The dependence of the natural logarithm of the intrinsic binding constant, Kin (■) and cooperativity parameter, ω (□), for the binding of the DENV polymerase to poly(ϵA) upon the reciprocal of the temperature (Kelvin) (van't Hoff plots). The solid lines are linear least squares fits to Equation 15 (for details, see “Results”). Error bars, S.E.

DISCUSSION

In the Absence of Magnesium, the Total Site Size of the Full-length DENV Polymerase-ssRNA Complex Is 26 ± 2 Nucleotides

To our knowledge, studies described in this work are the first quantitative characterization of the full-length Flaviviridae RNA-dependent RNA polymerase interactions with both single- and double-stranded conformations of the RNA and DNA. The total site size of the protein-nucleic acid complex is a fundamental parameter indispensable in any quantitative analysis of the energetics and dynamics of the formed complex (31, 32, 36, 38, 50–52). It is the nucleic acid fragment occluded by the protein and prevented from interacting with another protein molecule (50–52). For instance, any design of the nucleic acid substrates to address the catalytic activities of the polymerase must take into account the site size of the protein-ssRNA complex. The obtained results show that, in the absence of magnesium, the full-length DENV polymerase occludes ∼26 nucleotides in the complex with the ssRNA (Fig. 4b). On the other hand, the model based on crystallographic studies of the isolated polymerase domain suggests that the binding site of the enzyme could accommodate only 5–7 nucleotides of the ssRNA (Fig. 1b) (9). First, the proposed crystallographic model addresses only the size of the RNA in the binding tunnel, not the total fragment of the RNA occluded by the domain. Second, the dimensions of the isolated domain (65 × 60 × 40 Å) are too small to occlude a fragment of ∼26 nucleotides of ∼92 Å in length, without assuming a very peculiar folding pattern of the nucleic acid in the complex.

Analytical ultracentrifugation studies indicate that the full-length DENV polymerase has an elongated shape in solution. Such an elongated shape can accommodate the site size of ∼26 nucleotides. Moreover, it indicates that the enzyme assumes a rather rigid structure where the MTase and polymerase domains are placed side-by-side in the full-length protein. Thus, the strikingly large difference between the size of the proposed binding site of the isolated polymerase domain and the determined total site size of the full-length DENV polymerase-ssRNA complex in solution indicates that the methyltransferase domain of the full-length enzyme must protrude over the bound nucleic acid.

Magnesium Binding to the DENV Polymerase Affects the Global Conformation of the Enzyme, Leading to the Increased Total Site Size of the Protein-ssRNA Complex

In the presence of magnesium, the site size of the DENV polymerase-ssRNA increases from 26 ± 2 to 29 ± 2 nucleotides (Figs. 4b and 6b). The transition is already completed at [MgCl2] = 1 mm, indicating that association of magnesium cations with a binding constant of at least ∼104 m−1 participates in the process. In the applied solution condition (100 mm NaCl), the Mg2+ binding to the single-stranded nucleic acid is characterized by a significantly lower affinity of ∼102 m−1 (55). Note that although the site size is increased at 1 mm MgCl2, the intrinsic affinity of the polymerase is only slightly affected in these conditions. Thus, the conformational transition does not seem to have an effect on the intermediate vicinity of the binding site. Altogether, the data indicate that the increase of the site size by the additional ∼3 nucleotides is due to the specific, high affinity magnesium binding to the polymerase, resulting in the global conformational transition of the enzyme possibly affecting the mutual reorientation of the methyltransferase and polymerase domains of the protein.

Above 1 mm MgCl2, the intrinsic affinity diminishes, and the log-log plot becomes linear (Fig. 7b). Nevertheless, the slope of the plot indicates that only ∼1 ion participates in the ion exchange reaction at the protein-nucleic acid interface (53, 54). If a simple ion exchange process occurred, then the slope of the log-log plot for MgCl2 would be half the value of ∼6.2 observed for NaCl (Fig. 5b) (53, 54). Because much larger changes of the NaCl concentration do not produce a similar decrease of the intrinsic affinity of the enzyme (Fig. 5b), the effect of anions on the polymerase-ssRNA association seems to be negligible. Therefore, the simplest explanation of the observed behavior is that an additional low affinity magnesium binding process to the protein is observed, which affects the intrinsic association with the nucleic acid.

The DENV Polymerase Forms a Single Type of Complex with the ssRNA

Although the total site size of the protein-DNA complex includes nucleotides inaccessible for the binding of another protein molecule, it may have a heterogeneous structure and contain an area(s) that is directly involved in interactions with the nucleic acid as well as the nucleotides occluded by the protruding protein matrix. Previously, we found a profound heterogeneous structure of the total DNA-binding site of the rat and human polymerase β as well as the polymerase X of the African swine fever virus, which plays a significant functional role in activities of these enzymes (28, 36, 56–59). However, whereas the rat and human polymerase β form different binding modes in the complex with the ssDNA, in which the enzyme engages different domains and occludes different number of nucleotides, the African swine fever virus polymerase X forms a single complex with the nucleic acid, despite the heterogeneous structure of its total DNA-binding site (28, 36, 56–59).

In this context, the dependence of the poly(ϵA) fluorescence upon the total average binding density, Σvi, of the DENV polymerase is, within experimental accuracy, linear (Figs. 4b and 6b). The advantage of using the etheno-derivatives of the ssDNA and ssRNA is that their fluorescence depends little upon the polarity of the environment and predominantly reflects the structure of the nucleic acid (23, 60). The linear dependence of ΔFobs over a large range of Σvi does not exclude the heterogeneous structure of the total binding site, as is the case of the African swine fever virus polymerase X (28, 36). Nevertheless, it indicates that, similar to the African swine fever virus polymerase X, the full-length DENV polymerase forms a single type of complex with the polymer nucleic acid. This is true both in the absence and presence of Mg2+ where the enzyme has different total site sizes (see above). The structural and functional heterogeneity of the total nucleic acid binding site of the DENV polymerase awaits further quantitative studies.

The Intrinsic Affinity of the DENV Polymerase Shows Preference for the Homopyrimidine RNAs, whereas a Significant Positive Cooperativity in the Binding Process Is Observed Only for the Homopurine Nucleic Acids

The statistical thermodynamic approach applied in this work allows us to quantitatively extract both the intrinsic affinities and the cooperative interactions parameter, ω, characterizing the interactions between the bound DENV polymerase molecules (52). With the exception of poly(ϵA), the intrinsic affinity of the enzyme is moderately higher for the homopurine ssRNAs, poly(U) and poly(C), than for poly(A) (Table 1). However, the most striking difference between the homopyrimidine and homopurine polymers is in the value of the cooperative interactions parameter, ω. Whereas the binding to poly(U) and poly(C) is noncooperative, association with poly(A) is characterized by a significant positive cooperativity. The same is true for poly(ϵA) and poly(dA) (Table 1).

There are two important aspects of these data. First, in order to engage in cooperative interactions, the DENV polymerase must have different orientation on the nucleic acid, which favors the engagement of the interacting areas of the protein, without changing its site size in the complex. Second, depending on the RNA sequence, the enzyme will act alone or form clusters on the nucleic acid lattice, with possible different catalytic activities. Moreover, the cooperative interactions strongly decrease with the increase of the salt and/or magnesium concentration in solution (Figs. 5c and 7c). The slopes of the log-log plots for NaCl and MgCl2 are ∼−4.2 and ∼−0.9, respectively. The difference between the values of the slopes indicates that a specific ion binding, not a simple ion exchange process, controls the cooperative interactions between bound polymerase molecules and, in turn, orientation of the enzyme on the nucleic acid (see above).

The DENV Polymerase Binds the dsDNA with an Affinity Similar to the Intrinsic Affinity of the ssRNA, Indicating That the Total Nucleic Acid Binding Site of the Enzyme Has an Open Conformation in Solution

As mentioned above, crystallographic studies of the isolated DENV polymerase domain as well as other viral RNA-dependent polymerases indicate that the nucleic acid binding site forms a tunnel-like entity, ∼30 Å deep and only 24 Å wide, on the surface of the protein (9). It has been proposed that the enzyme is initially in a closed conformation, with several loops predominantly originating from the thumb domain, hindering/closing the access of the nucleic acid to the site (Fig. 1b). Thus, the catalytic competence of the polymerase would not be a preexisting state of the enzyme, but the nucleic acid binding would induce it. A very slow binding step in the association of the isolated DENV polymerase domain-template-primer complex seems to support this model and was proposed to result from the temperature-dependent, structural rearrangement of the closing loops (13).

However, direct thermodynamic studies reported in this work, with the full DENV polymerase, clearly show that the enzyme has a dsDNA intrinsic affinity in the range of ∼4.3 × 105 to ∼8.0 × 105 m−1 (i.e. comparable with the affinities for the examined ssRNA homopolymers) in the same solution conditions (Table 1). These data are not compatible with the closed binding site model, with a strong preference for the single-stranded conformation of the nucleic acid, and indicate that the solution structure of the binding site of the full-length enzyme is different from that seen in the crystal structure of the isolated domain (9). It is possible that the lack of the methyltransferase domain and the domain-domain interactions result in the closed state of the binding site of the isolated polymerase domain seen in the crystal. In other words, the full-length DENV polymerase is in an open conformational state prior to the binding of the nucleic acid and can accept both the single- and double-stranded conformations of the nucleic acid.

In this context, the lack of detectable affinity of the enzyme for the dsRNA and the dsRNA-DNA hybrid is puzzling. Nevertheless, these results are in agreement with previous studies, which indicated that the enzyme affinity for the dsRNA is very low, if any (14). It has also been proposed that the DENV polymerase binding site can accommodate the dsRNA at higher temperatures (14). Such behavior would indicate that the transformation of the binding site and the binding process should be characterized by a large and unfavorable enthalpy change. On the other hand, intrinsic binding of the enzyme to the ssRNA (as well as the cooperative interactions) is characterized by large and favorable apparent enthalpy changes (Fig. 8). In effect, both reactions are enthalpy-driven processes with large and unfavorable entropy changes. These results corroborate the conclusion that the binding site of the full-length polymerase is open in solution, as indicated by fact that it can easily accommodate the dsDNA and energetically favorably adjusts to the entering nucleic acid (see above). In consequence, the data strongly suggest that, in the entry process of the duplex nucleic acid to the binding site, the site specifically checks the nature of the sugar-phosphate backbone of the duplex conformation and/or the duplex conformation (A versus B structure) and requires additional conformation adjustment for the dsRNA and dsRNA-DNA hybrid with their A structures, in a process characterized by positive enthalpy change.

Note that the DENV polymerase, which is a RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, shows similar intrinsic affinity for both the ssRNA and the ssDNA. It is possible that the preference for ssRNA is determined by interactions with other components of the viral replication apparatus in the cell (34). Moreover, the fact that the enzyme shows preference for the pyrimidine stretches of the nucleic acid, while changing its orientation and engaging in positive cooperative interactions on the purine-rich fragments, strongly suggests that the replication mechanism of the viral RNA by DENV polymerase depends on the sequence of the encountered nucleic acid. Our laboratory is currently studying these issues.

Acknowledgment

We thank Gloria Drennan Bellard for help in preparing the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM-58565 (to W. B.) and AI-087856. This work was also supported by a Sealy Memorial Endowment Fund research pilot grant (to K. C.).

- DENV

- dengue virus

- MTase

- methyltransferase.

REFERENCES

- 1. Blok J. (1985) J. Gen. Virol. 66, 1324–1325 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Westaway E. G. (1987) Adv. Virus Res. 33, 45–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chambers T. J., Hahn C. S., Galler R., Rice C. M. (1990) Annu. Rev. Mirobiol. 44, 649–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Guzmán M. G., Kourí G. (2002) Lancet Infect. Dis. 2, 33–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Halstead S. B. (2002) Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 15, 471–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferrer-Orta C., Arias A., Escarmís C., Verdaguer N. (2006) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16, 27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Choi K. H., Rossmann M. G. (2009) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 19, 746–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Egloff M. P., Benarroch D., Selisko B., Romette J. L., Canard B. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 2757–2768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yap T. L., Xu T., Chen Y. L., Malet H., Egloff M. P., Canard B., Vasudevan S. G., Lescar J. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 4753–4765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yap L. J., Luo D., Chung K. Y., Lim S. P., Bodenreider C., Noble C., Shi P. Y., Lescar J. (2010) PLoS ONE 5(9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Choi K. H., Gallei A., Becher P., Rossmann M. G. (2006) Structure 14, 1107–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nomaguchi M., Ackermann M., Yon C., You S., Padmanabhan R. (2003) J. Virol. 77, 8831–8842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jin Z., Deval J., Johnson K. A., Swinney D. C. (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2067–2077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ackermann M., Padmanabhan R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 39926–39937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Joyce C. M., Benkovic S. J. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 14317–14324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Luo G., Hamatake R. K., Mathis D. M., Racela J., Rigat K. L., Lemm J., Colonno R. J. (2000) J. Virol. 74, 851–863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Selisko B., Dutartre H., Guillemot J. C., Debarnot C., Benarroch D., Khromykh A., Despres P., Egloff M. P., Canard B. (2006) Virology 351, 145–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Edelhoch H. (1967) Biochemistry 6, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gill S. C., von Hippel P. H. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 182, 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eisenberg H., Felsenfeld G. (1967) J. Mol. Biol. 30, 17–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kowalczykowski S. C., Lonberg N., Newport J. W., von Hippel P. H. (1981) J. Mol. Biol. 145, 75–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ledneva R. K., Razjivin A. P., Kost A. A., Bogdanov A. A. (1978) Nucleic Acids Res. 5, 4225–4243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tolman G. L., Barrio J. R., Leonard N. J. (1974) Biochemistry 13, 4869–4878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jezewska M. J., Rajendran S., Bujalowski W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27865–27873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bujalowski W., Jezewska M. J. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 8513–8519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Galletto R., Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 11002–11016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jezewska M. J., Galletto R., Bujalowski W. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 11864–11878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski P. J., Bujalowski W. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 12909–12924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski P. J., Bujalowski W. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 373, 75–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bujalowski W., Jezewska M. J. (2000) Spectrophotometry and Spectrofluorimetry: A Practical Approach (Gore M. G. ed) pp. 141–165, Oxford University Press, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (1996) Biochemistry 35, 2117–2128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bujalowski W. (2006) Chem. Rev. 106, 556–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lohman T. M., Bujalowski W. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 208, 258–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kapoor M., Zhang L., Ramachandra M., Kusukawa J., Ebner K. E., Padmanabhan R. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19100–19106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jezewska M. J., Galletto R., Bujalowski W. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 343, 115–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jezewska M. J., Marcinowicz A., Lucius A. L., Bujalowski W. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 356, 121–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jezewska M. J., Rajendran S., Bujalowski W. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 3116–3136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Szymanski M. R., Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 398, 8–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bujalowski W., Klonowska M. M., Jezewska M. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 31350–31358 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 4261–4265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Galletto R., Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 329, 441–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marcinowicz A., Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 375, 386–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roychowdhury A., Szymanski M. R., Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 6712–6729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cantor R. C., Schimmel P. R. (1980) Biophysical Chemistry, Vol. II, pp. 591–641, W. H. Freeman, New York [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stafford W. F., 3rd (1992) Anal. Biochem. 203, 295–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Correia J. J., Chacko B. M., Lam S. S., Lin K. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 1473–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kuntz I. D. (1971) J. Am. Chem. Soc. 93, 514–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bull H. B., Breese K. (1968) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 128, 497–502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Galletto R., Maillard R., Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (2004) Biochemistry 43, 10988–11001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. McGhee J. D., von Hippel P. H. (1974) J. Mol. Biol. 86, 469–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Epstein I. R. (1978) Biophys. Chem. 8, 327–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bujalowski W., Lohman T. M., Anderson C. F. (1989) Biopolymers 28, 1637–1643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Record M. T., Jr., Lohman M. L., De Haseth P. (1976) J. Mol. Biol. 107, 145–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Record M. T., Jr., Anderson C. F., Lohman T. M. (1978) Q. Rev. Biophys. 11, 103–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Krakauer H. (1971) Biopolymers 10, 2459–2490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jezewska M. J., Rajendran S., Galletto R., Bujalowski W. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 313, 977–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Jezewska M. J., Galletto R., Bujalowski W. (2003) Cell Biochem. Biophys. 38, 125–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rajendran S., Jezewska M. J., Bujalowski W. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 11794–11810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jezewska M. J., Marcinowicz A., Lucius A. L., Bujalowski W. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 356, 121–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Baker B. M., Vanderkooi J., Kallenbach N. R. (1978) Biopolymers 17, 1361–1372 [Google Scholar]