Abstract

Prostate cancer is the most frequently diagnosed male malignancy. The normal prostate development and prostate cancer progression are mediated by androgen receptor (AR). Recently, the roles of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) and its activator, p35, in cancer biology are explored one after another. We have previously demonstrated that Cdk5 may regulate proliferation of thyroid cancer cells. In addition, we also identify that Cdk5 overactivation can be triggered by drug treatments and leads to apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. The aim of this study is to investigate how Cdk5 regulates AR activation and growth of prostate cancer cells. At first, the data show that Cdk5 enables phosphorylation of AR at Ser-81 site through direct biochemical interaction and, therefore, results in the stabilization of AR proteins. The Cdk5-dependent AR stabilization causes accumulation of AR proteins and subsequent activation. Besides, the positive regulations of Cdk5-AR on cell growth are also determined in vitro and in vivo. S81A mutant of AR diminishes its interaction with Cdk5, reduces its nuclear localization, fails to stabilize its protein level, and therefore, decreases prostate cancer cell proliferation. Prostate carcinoma specimens collected from 177 AR-positive patients indicate the significant correlations between the protein levels of AR and Cdk5 or p35. These findings demonstrate that Cdk5 is an important modulator of AR and contributes to prostate cancer growth. Therefore, Cdk5-p35 may be suggested as diagnostic and therapeutic targets for prostate cancer in the near future.

Keywords: Protein Degradation, Protein Phosphorylation, Protein Translocation, Protein-Protein Interactions, Serine Threonine Protein Kinase, Signal Transduction, Cdk5, Androgen Receptor, p35, Prostate Cancer

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a commonly diagnosed malignancy in men, and androgen plays an important role in its early development (1). Androgen deprivation has been considered as a common therapy for androgen-dependent prostate cancer. However, the existing cancer cells eventually become hormone-refractory, and the following therapy usually gets into scrapes. The androgen receptor (AR),2 which belongs to the steroid receptor family and plays pivotal roles in the development of the prostate gland and the pathogenic progression of prostate cancer. High levels of AR expression along with its target genes have been reported in hormone-refractory prostate cancer cells, suggesting that AR signaling is activated regardless of the levels of serum androgen (2). A study analyzing consensus sequences of phosphorylation indicates that AR contains more than 40 predicted phosphorylation sites (3). Ser-81 of the AR N terminus is the most intensely phosphorylated site in response to androgen binding (4). The latest report reveals the relevance of Ser-81 phosphorylation and AR promoter selectivity as well as cell growth (5). Our recent work also shows the increase of Ser-81 phosphorylation of AR in the androgen-independent LNCaP sub-line (6). Fu et al. (7) proposed that the phosphorylation consensus sequence (SPRT) of cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5) corresponds with the sequence around AR Ser-81. Although AR was reported as substrates for Cdk9 (5) as well as Cdk1 (8), which has high homology with Cdk5, there is no evidence showing a relationship between AR and Cdk5 in prostate cancer. Therefore, the involvement of Cdk5 in AR-related pathogenesis of prostate cancer is interesting to investigate.

Cdk5 is a unique member of the Cdk family due to its irrelevance in cell cycle regulation (9). Cdk5 needs to bind with a regulator to get activated. One major regulating partner for Cdk5 is p35, which was first reported in post-mitotic neurons (10). The crucial role of the Cdk5-p35 complex is to support the development of the central nervous system (CNS) (10, 11). Our previous report shows the importance of Cdk5 in a Drosophila neurodegenerative model (12). In addition to its roles in CNS, numerous groups have sequentially demonstrated the involvement of Cdk5 in different cancers, including liver cancer (13), colorectal cancer (14), pancreatic cancer (15), breast cancer (16, 17), and lung cancer (18–20). Our published data also demonstrate that Cdk5 positively modulates proliferation of thyroid cancer cells through STAT3 activation (21). The effects of retinoic acid on Cdk5 overactivation and consequent apoptosis in cervical cancer cells were also previously shown by us (22). On the other hand, our results indicate that Cdk5 regulates androgen production of mouse Leydig cells through modulating the stability of steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein (23). In prostate cancer cells we discovered that digoxin-triggered Cdk5 overactivation may lead to apoptosis (24). This is the first report demonstrating the role of Cdk5 in prostate cancer cells. Subsequently, the involvement of Cdk5 in metastasis of prostate cancer has been reported (25). However, the relationship between Cdk5 and prostate cancer growth has not yet been identified.

Here we provide evidence demonstrating that Cdk5 activates and stabilizes AR through Ser-81 phosphorylation in prostate cancer cells. The expression correlations of Cdk5/p35 and AR proteins in prostate cancer patients are also proven. Taken together, these findings suggest that Cdk5 signaling plays a significant role in the growth of prostate cancer cells through AR activation. Therefore, Cdk5 and p35 might be potential targets in the diagnosis and treatment of prostate cancer in the future.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

R1881 (methyltrienolone, a synthetic androgen) was purchased from PerkinElmer Life Sciences; roscovitine and cycloheximide were purchased from Sigma; MG132 was purchase from Calbiochem. Antibodies used for immunoblotting were Cdk5, AR, p35, prostate-specific antigen (PSA), Octa-Probe (FLAG), ubiquitin (Santa Cruz), phospho-Ser-81-AR (Millipore), α-tubulin, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (Upstate Biotechnology) and β-actin (Chemicon). Secondary antibodies were peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit (The Jackson Laboratory). Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry were AR, Cdk5, and p35 (Santa Cruz).

Cell Culture

LNCaP (BCRC-60088), PC-3 (BCRC-60348), and 22Rv1 (BCRC-60545) cell lines were purchased from Food Industry Research and Development Institute, Hsinchu, Taiwan. LNCaP and 22Rv1 cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 culture medium supplemented with 1.5 g/liter NaHCO3, 10% FBS, 10 mm HEPES, 1 mm sodium pyruvate, and 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (P/S). PC-3 cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium plus 10% FBS, 1.5 g/liter NaHCO3, and P/S. HEK293 cells were kindly provided by Professor Hong-Chen Chen (Department of Life Sciences, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan) and were cultured in DMEM culture medium supplemented with 1.5 g/liter NaHCO3, 10% FBS, and 100 IU/ml P/S. All cell lines were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. All experiments related to androgen treatment were pretreated in androgen-deprived conditions with complete medium plus dextran-coated charcoal-treated FBS (for 24 h).

Immunoprecipitation, Fractionation, and Immunoblotting Analyses

Cell lysates were obtained in lysis buffer. Lysates were analyzed by direct immunoblotting (20–35 μg/lane) or blotting after immunoprecipitation (0.5–1 mg/immunoprecipitation) using methods modified from those previously described (12, 21, 23, 24). Immunoprecipitates were collected by binding to 25–40 μl of the ExactaCruz beads (Santa Cruz). To isolate subcellular proteins, cells were collected and washed in PBS/Na3VO4. Subsided cells were resuspended in hypotonic buffer (10 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 10 mm KCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm EGTA, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm PMSF, 2 mm Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor mixture). Nuclear proteins were in the pellet, whereas the supernatant contained the cytosolic fraction. The nuclear pellet was washed 3 times with hypotonic buffer before lysing in nuclear extraction buffer (20 mm HEPES (pH 7.9), 0.4 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 m EGTA, 20% glycerol, 1 mm PMSF, 2 mm Na3VO4, and protease inhibitor mixture). The lysates were mixed with ⅓ volume of 5× SDS sample buffer and resolved by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. ECL detection reagent (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) was used to visualize the immunoreactive proteins on PVDF membranes (PerkinElmer Life Sciences) after transfer using a Trans-Blot SD (Bio-Rad).

In Vitro Kinase Assay

In vitro kinase assays were performed by washing immunoprecipitates five times with lysis buffer. The ExactaCruz beads with target proteins were incubated at 30 °C for 30 min in kinase reaction buffer containing 10 μg of substrates (histone H1, Upstate Biotechnology; homemade human recombinant AR), 10 μl of magnesium/ATP mixture (Upstate Biotechnology), 5 μl of 5× assay dilution buffer (Upstate Biotechnology; 100 mm MOPS (pH 7.2), 125 mm β-glycerophosphate, 25 mm EGTA, 5 mm Na3VO4, and 5 mm dithiothreitol), and 1–3 μCi of [32P]ATP in a final volume of 25 μl. The reaction was terminated by adding 7 μl of 5× SDS sample buffer and boiling for 3 min. The samples were separated by 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized on the x-ray film (Fujifilm) (24, 26).

Cell Viability Assay

The modified colorimetric 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was performed to quantify the viability of LNCaP cells. Yellow MTT compound (Sigma) is converted by living cells into blue formazan, which is soluble in isopropyl alcohol. The blue staining was measured using an optical density reader (Athos-2001, Australia) at 570 nm (background of isopropyl alcohol, 620 nm) (21, 24).

Immunocytochemistry

LNCaP and 22Rv1 cells cultured on coverslips were fixed for 15 min in 4% paraformaldehyde with 2% sucrose in PBS at room temperature after 3 washes in PBS. Fixed cells were then washed again in PBS. Then the buffer containing 1% BSA and 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS was added and mixed for 1–2 min at room temperature. After discarding the buffer, the cells were washed in PBS and blocked in 5% BSA-PBS for another 15 min at room temperature. Primary antibodies against Cdk5 and AR were diluted in 5% BSA-PBS and incubated with coverslips overnight at 4 °C. Cells were washed in PBS and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C with FITC- or TRITC-conjugated secondary antibodies (The Jackson Laboratory). After extensive washing, the coverslips were mounted in Gel/Mount (Biomeda) and observed using Olympus fluorescence or Leica confocal microscopes.

Transfection

siRNA-cdk5 and nonspecific control siRNA were purchased from Dharmacon (SMARTpoolTM). shRNA plasmids of pLKO.1-gfp, -cdk5, and -p35 were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility located at the Institute of Molecular Biology/Genome Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan. pcDNA3-FLAG-WT-AR, -S81A-AR, and pGL3–3×ARE (androgen response element) (4) expression plasmids were kindly provided by Professor Daniel Gioeli, Department of Microbiology, University of Virginia. pSV-β-galactosidase expression plasmid was a gift from Professor Jeremy J. W. Chen, Institute of Biomedical Sciences, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan. Human p35 and Cdk5 expression plasmids were constructed by RT-PCR amplification of the human p35- and cdk5-coding sequences and inserted into the pcDNA3 vector (Invitrogen) by TA cloning. The integrities of all constructs were verified by DNA sequencing. Transfections of siRNAs or plasmids into cell lines were performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen).

Reporter Assay

Luciferase reporter gene activity was carried out according to the Dual-Light System (Applied Biosystems). Cells were transfected with luciferase expression plasmids with β-galactosidase plasmids following the manufacturer's instructions. Cells were washed twice with PBS and lysed in lysis solution at room temperature for 15–20 min. Cell lysates were centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C. Supernatants were mixed with luciferase substrate. Reporter gene activity was measured by 1420 Multilabel Counter VICTOR3 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). The transfection efficiency was normalized by β-galactosidase activity.

Immunohistochemistry

Detailed experimental procedures were modified by paraffin immunohistochemistry protocol (Cell Signaling). Prostate cancer tissue array was purchased from Biomax Co., and the thickness of each specimen was 5 μm. The slides were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in graded alcohol and H2O. An antigen retrieval step with 10 nm sodium citrate (pH 6.0) at a sub-boiling temperature was used for each primary antibody. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min followed by a 1-h incubation with blocking serum (Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories). The slides were then incubated for 4 h at room temperature followed by incubation with biotinylated antibody (Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) for 30 min. Finally, the slides were incubated in ABC reagent (Vectastain ABC Kit, Vector Laboratories) for 30 min and in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 2 min. The slides were counterstained with diluted hematoxylin solution (1:10; Merck) and dehydrated with graded alcohol and xylene. Finally, the slides were mounted and recorded by light microscope (Bx-51, Olympus). The blue color indicated nucleus stained by hematoxylin. The brown color indicated the target proteins stained by the 3,3′-diaminobenzidine kit. The images were blinded and evaluated by two experts in accordance with a scoring system that was based on the intensity and distribution of staining signals. The scores were divided into four grades: negative (0, 0%), low (1, 1–17%), moderate (2, 18–35%), and high (3, > 35%). Representative images for each grade of proteins were shown in supplemental Fig. S5.

Xenografted Tumor Growth in Nude Mice

The BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the National Laboratory Animal Center, Taipei, Taiwan. 22Rv1 cells (107 cells per mouse) were subcutaneously injected into the backs of BALB/c nude mice. When the tumor volumes reached 500–1000 mm3, 10 μg of shRNA-cdk5 or Cdk5 plasmids were mixed with in vivo jetPEI transfection reagent (Polyplus) and directly injected into the xenografted tumors every 3 days. The mice in the mock group received shRNA-gfp or EGFP plasmids for different experiments. The major axis (L) and the short axis (W) were measured every day. Tumor volumes were estimated using the formula L × W × W × 3.14/6. The mice were sacrificed 3 days after the final injection.

Statistics

All values are given as the means ± S.E. of the mean (S.E.). Student's t test was used in the proliferation, animal, and reporter assay experiments. A difference between two means was considered statistically significant when p < 0.05. The correlation between Cdk5 or p35 levels to AR levels in tumor specimens was analyzed using Fisher's exact test by S-PLUS 6.2 Professional software.

RESULTS

The Biochemical Relationship between Cdk5 and AR

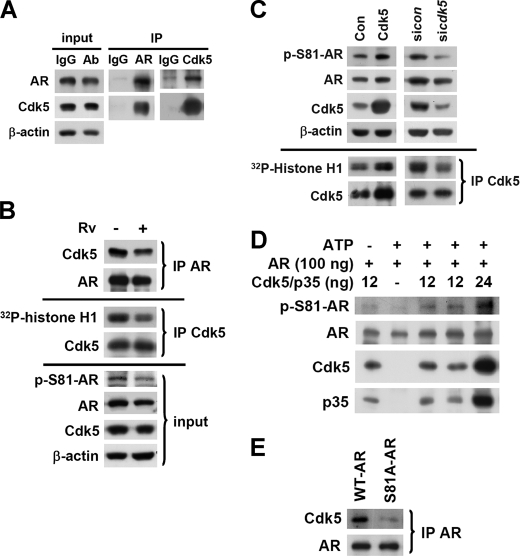

There are seven serine phosphorylation sites that have been identified on the AR protein (4) in which the intensity of Ser-81 phosphorylation in the presence of ligand stimulation is constantly high. According to the comparison of the neighboring sequence of AR Ser-81 site (LLQETSPR) (4) and the phosphorylation consensus sequence of Cdk5, SPRT (7), we propose that Cdk5 might be responsible for AR Ser-81 phosphorylation in prostate cancer cells. To test this hypothesis, the biochemical interaction and subcellular distribution of AR and Cdk5 proteins in prostate cancer cells were initially identified by immunoprecipitation and immunocytochemistry with specific antibodies (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. S1A). Interestingly, roscovitine (Rv, a small molecular inhibitor of Cdk5 in prostate cancer cells (24)) treatment was found to inhibit Cdk5 activity detected by in vitro kinase assay using histone H1 as the substrate and also reduce Cdk5-AR protein interaction detected by immunoprecipitation in LNCaP cells in the presence of low concentration of R1881 (a synthetic androgen; 0.1 nm for 24 h in the steroids-stripped medium) (upper panel, Fig. 1B). The following experiments of cell lines were all performed in the aforementioned condition. These data suggest that Cdk5 activity is important to Cdk5-AR biochemical interaction. Subsequently, the inhibitory effect of Rv on AR Ser-81 phosphorylation was discovered (lower panel, Fig. 1B). AR Ser-81 phosphorylation and Cdk5 kinase activity were, respectively, increased and decreased in response to overexpression and knockdown of Cdk5 or p35 in LNCaP cells (Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S1B). In addition, we further identified the Ser-81 phosphorylation of recombinant AR protein by Cdk5-p35 complex (Millipore Co.) in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of R1881 via an in vitro kinase assay (Fig. 1D). Intriguingly, the S81A mutant significantly reduced the AR-Cdk5 biochemical interaction (Fig. 1E), which indicates that AR Ser-81 is a critical site for Cdk5 modulation.

FIGURE 1.

AR Ser-81 phosphorylation is Cdk5-dependent. A, the biochemical interaction between AR and Cdk5 in LNCaP cells was examined by immunoprecipitation (IP) with specific anti-AR and anti-Cdk5 antibodies (Ab), whereas IgG served as a negative control. The 5% of total untreated lysates before immunoprecipitation served as input. B, the inhibiting effect of Rv (10 μm, 24 h) on Cdk5-AR biochemical interactions in LNCaP cells was evaluated by immunoprecipitation with specific anti-AR antibody. The kinase activity of Cdk5 in LNCaP cells was measured by the in vitro kinase assay using histone H1 as the substrate of Cdk5. Ser-81 phosphorylation of AR was evaluated by immunoblotting with commercial specific anti-phospho-Ser-81-AR antibody after Rv (10 μm, 24 h) treatment. C, shown is Cdk5 overexpression or Cdk5 knockdown in LNCaP cells in the presence of R1881 (a synthetic androgen; 0.1 nm, 24 h). The control groups were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3) or siRNA-control. The corresponding Cdk5 activity in LNCaP cells was performed by in vitro kinase assay using histone H1 as the substrate. D, human recombinant AR was used as a substrate to perform the Cdk5 in vitro kinase assay in the presence of R1881. Ser-81 phosphorylation of AR was detected by immunoblotting with a specific antibody. E, the biochemical interactions of Cdk5 and WT AR or S81A AR mutant were evaluated by immunoprecipitation with specific anti-AR antibody after overexpressing individual AR proteins in LNCaP cells.

Cdk5 Increases AR Stability through Phosphorylation

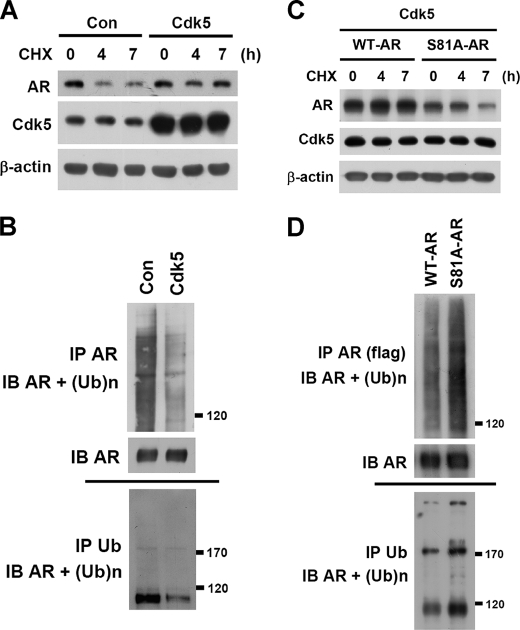

AR is a short half-life protein and tends to be degraded through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (27). The data in Fig. 1C and supplemental Fig. S1B indicated that AR protein levels were simultaneously changed with Cdk5 or p35 proteins, whereas AR mRNA was not affected (data not shown). Therefore, it is interesting to explore whether Cdk5 regulates AR protein stability and whether Ser-81 phosphorylation contributes to this regulation. We found that MG132 (a proteasome inhibitor) rescued sicdk5-caused AR degradation (data not shown). Subsequently, cycloheximide (an inhibitor of protein synthesis) was used to block cellular protein synthesis, and the degradation of existing protein was then monitored. The data indicated that Cdk5 or p35 overexpression could slow down AR degradation in LNCaP cells (Fig. 2A and supplemental Fig. S2A). The intensity of ubiquitinated AR was weaker by Cdk5 overexpression than empty-vector control group (Fig. 2B). In contrast, AR protein degradation was accelerated after Rv treatment or p35 knockdown (supplemental Fig. S2, B and C). Importantly, Cdk5 or p35 overexpression failed to protect against the degradation of S81A-AR mutant (Fig. 2C and supplemental Fig. S2D). The intensity of ubiquitinated S81A-AR mutant was stronger than wild-type AR (Fig. 2D). These results suggest that Cdk5 may result in AR stabilization through Ser-81 phosphorylation.

FIGURE 2.

Cdk5 prevents AR degradation through Ser-81 phosphorylation. A, cycloheximide (CHX) (an inhibitor of protein synthesis, 10 μg/ml) was treated in a time-course manner (0, 4, and 7 h), and AR protein degradation was monitored by immunoblotting. Endogenous AR degradation in LNCaP cells was monitored after Cdk5 overexpression in the presence of 0.1 nm R1881 (24 h). Con, control. B, MG132 (proteasome inhibitor; 5 μm, 6 h) was used to block the proteasome-dependent degradation in LNCaP cells. The ubiquitination of AR was immunoblotted (IB) after immunoprecipitating (IP) with specific anti-AR or anti-ubiquitin (Ub) antibodies. The control groups of both A and B were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3). C, cycloheximide (10 μg/ml; 0, 4, and 7 h) was used to block protein synthesis. The degradations of exogenous WT or S81A AR in PC3 cells were monitored after Cdk5 overexpression in the presence of 0.1 nm R1881 (24 h). D, MG132 (5 μm, 6 h) was used to block the proteasome-dependent degradation in LNCaP cells. The ubiquitinations of FLAG-tagged WT or S81A AR were evaluated by immunoprecipitation with specific anti-FLAG and anti-Ub antibodies.

Cdk5 Promotes AR Activation

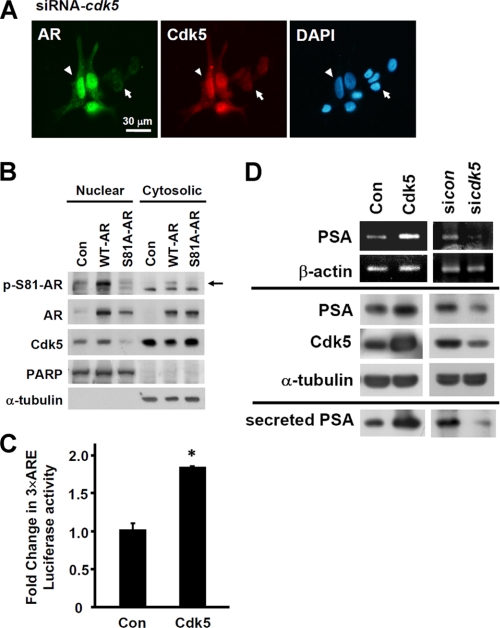

To understand the effects of Cdk5 on AR activation, changes in AR localization were observed after treating with proteasome inhibitor MG132 by using immunocytochemistry. Fig. 3A showed that Cdk5 knockdown by siRNA decreased the nuclear localization of AR (arrows in Fig. 3A), whereas AR protein levels were held by MG132. This phenomenon was identified in 76.7 ± 10.2% of transfected cells (total 50 Cdk5-knockdown cells). The arrowheads indicate the cells that were unaffected by siRNA. The immunocytochemical results in the control group showed that AR protein primarily distributes in nuclei (supplemental Fig. S3A). In addition, EGFP-Cdk5 fusion protein was overexpressed in LNCaP cells in the presence of MG132 treatment. Compared to the untransfected cells without green signals (arrowheads in supplemental Fig. S3B), EGFP-Cdk5 overexpression apparently enhanced AR nuclear distribution (arrows in supplemental Fig. S3B). This phenomenon was identified in 50.4 ± 4.3% transfected cells (total 50 Cdk5-overepression cells). These results suggest that Cdk5 regulates not only AR stability but also AR subcellular distribution. Consequently, the role of Ser-81-phosphorylation on AR localization was then investigated in AR low-expressing PC3 cells. S81A-AR mutant decreased its nuclear distribution but increased its cytosolic distribution after inhibiting AR degradation under MG132 treatment (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, Cdk5 distribution was correspondent with AR distribution (Fig. 3B). Our data further indicated that AR-targeted promoter activity by using pGL3–3×ARE (androgen response element) was significantly stimulated by Cdk5 overexpression with exogenous AR proteins in HEK293 cells in the presence of R1881 (Fig. 3C). Moreover, the mRNA expression of PSA, a target gene of AR, was affected by Cdk5 protein levels (upper panel, Fig. 3D). In accordance with mRNA results, both intracellular and secreted PSA proteins were increased by Cdk5 overexpression and reduced by Cdk5 knockdown (lower panel, Fig. 3D) or Rv treatment3 in LNCaP cells in the presence of R1881. Interestingly, Cdk5 failed to affect AR transcriptional activity in the absence of androgen (supplemental Fig. S3, C and D). According to these results, Cdk5 activation is able to cause AR transactivation in prostate cancer cells in the androgen-dependent way.

FIGURE 3.

Cdk5-dependent Ser-81 phosphorylation on AR distribution and transactivation. A, Cdk5 knockdown was performed by siRNA in LNCaP cells. Cells were treated with MG132 (5 μm) for 6 h before performing immunocytochemistry with specific anti-AR as well as anti-Cdk5 antibodies, FITC (green signal)- and TRITC (red signal)-conjugated secondary antibodies. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue signal). The scale bar represents 30 μm. B, WT and S81A AR were overexpressed in PC3. Cells were treated with R1881 (0.1 nm) for 24 h and MG132 (5 μm) for 12 h before lysing. Cell lysates were segregated by protein fractionation. Phospho-Ser-81-AR, AR, and Cdk5 proteins were immunoblotted in both nuclear and cytosolic fractions. The control (Con) group was transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3). Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and α-tubulin served as markers for the nuclear and cytosolic fractions, respectively. The arrow indicates the positions of phospho-Ser-81-AR in the image. C, a 3×ARE (androgen response element)-luciferase reporter assay was performed in HEK293 cell lysates after Cdk5 and AR overexpression in the presence of R1881 (0.1 nm, 24 h) treatment. The expression of β-galactosidase served as the internal control. Data are represented as the means ± S.E. of the mean; *, p < 0.05 versus control group (EGFP transfection). D, the effects of Cdk5 protein expression changes on the levels of PSA mRNA (upper panel) and intracellular and secreted PSA proteins (lower panel) in LNCaP cell lysates and culture medium in the presence of R1881 (0.1 nm, 24 h) treatment were evaluated by semiquantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting, respectively. The control groups were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3) or shRNA-gfp. β-Actin and α-tubulin, respectively, served as the internal controls of mRNA and proteins.

Cdk5 Activity Regulates the Growth of Prostate Cancer Cells through Affecting AR

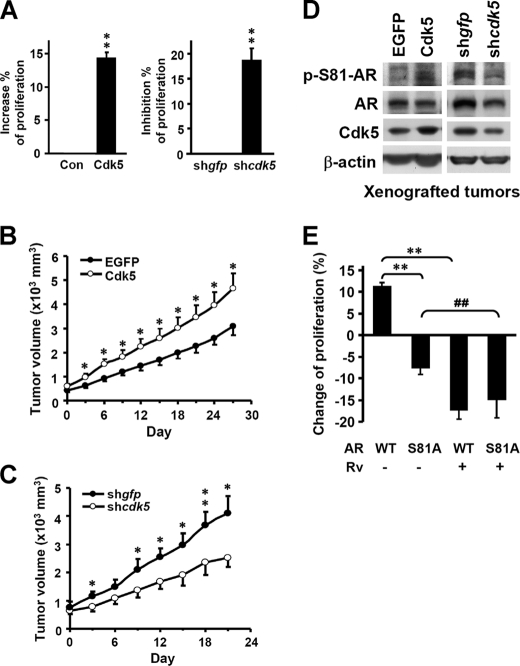

Cdk5 or p35 were observed to positively regulate the proliferation of prostate cancer cells (Fig. 4A and supplemental Fig. S4A). Furthermore, the AR-positive prostate cancer cell line (22Rv1) was xenografted onto BALB/c nude mice. After tumor sizes reached 500–1000 mm3, shRNA-cdk5 were intratumorally injected with in vivo jetPEI reagents every 3 days, and tumor volumes were recorded as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The results indicated that injection of Cdk5 plasmids (open circles) significantly stimulated tumor growth compared with the mock-transfected group, which was injected with EGFP plasmids (filled circles) (Fig. 4B). In contrast, injection of Cdk5 shRNA (open circles) retarded tumor growth compared with the shRNA-gfp injected group (filled circles) (Fig. 4C). Additionally, we found that the growth inhibition in the shRNA-cdk5 group gradually decreased after withdrawal of shRNA injection (days 24–27, data not shown). The immunoblotting results from xenografted tumors (from Fig. 4, B and C) demonstrated that AR Ser-81 phosphorylation was correlated with Cdk5 expressions (Fig. 4D), which supports the in vitro findings in Fig. 1C. Moreover, the immunohistochemical results from xenografted tumors (from Fig. 4B) exhibited AR protein levels were higher in the Cdk5 plasmids-injected group (brown signals in supplemental Fig. S4B). With regard to the in vivo experiment, the average blood PSA concentration was higher in the Cdk5 plasmid-injected xenografted group (4.04 ± 0.37 ng/ml) than in the control group (2.64 ± 0.29 ng/ml). On the other hand, WT-AR overexpression stimulated LNCaP cell proliferation, whereas the dominant negative S81A-AR mutant inhibited proliferation (bars 1 and 2, Fig. 4E). Rv treatment significantly inhibited the proliferation stimulation caused by WT-AR; however, the combination treatment of AR mutant and Rv did not cause further inhibition of proliferation as compared with the WT-AR plus Rv group (bars 3 and 4, Fig. 4E). It suggests that Ser-81 of AR might be important in the Cdk5-dependent regulation of prostate cancer cell growth. Taken together, Cdk5 might activate AR and, therefore, promote the growth of prostate cancer cells. According to these results, Cdk5 may play a role as a positive regulator of growth in prostate cancer cells through AR phosphorylation.

FIGURE 4.

Cdk5 promotes prostate cancer cell growth through AR. A, overexpression or knockdown of Cdk5 was performed in LNCaP cells. Cell proliferation was detected by MTT assay. The control (Con) value was set at 0. The control groups were transfected with empty vector (pcDNA3) or shRNA-gfp. The y axes represented the percentages of cell proliferation changes. The experiments were repeated three times, and the repetition in each was six. Data are represented as the means ± S.E. of the mean; **, p < 0.01 versus control groups. B, 22Rv1 cells were subcutaneously injected into the backs of BALB/c nude mice. Cdk5 or EGFP (for mock group) (B) and shRNA-cdk5 and shRNA-gfp (for mock group) expressing plasmids (C) were delivered by in vivo-jetPEI reagent into the growing tumors when the size of the tumors reached 500 mm3. Plasmid delivery was routinely performed every 3 days until the end of the experiment. Tumor volume was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data are represented as the means ± S.E. of the mean. (n = 10 for both groups in B and n = 6 for both groups in C); * and **, p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 versus mock group. D, AR Ser-81 phosphorylation, AR, and Cdk5 in lysates of xenografted tumors (from B and C) were determined by immunoblotting. β-Actin served as an internal control. E, the effects of AR S81A mutant and Rv treatment on LNCaP cell proliferation were determined by MTT assay. The control (empty vector, pcDNA3) value of proliferation was set at 0. The experiments were repeated three times, and the repetition in each one of the three experiments was eight. Data are represented as the means ± S.E. of the mean; **, p < 0.01 versus WT AR group; ##, p < 0.01 versus S81A mutant AR group.

Evidence from Patients

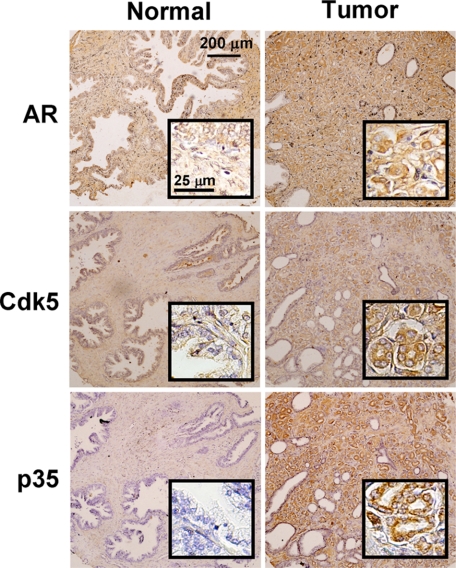

Based on the above results from basic research, we believe that Cdk5 is important to the growth of prostate cancer cells through AR regulation. To seek solid evidence supporting these findings, AR-positive prostate carcinoma specimens from 177 patients were collected (Biomax Co.). Protein levels of AR, Cdk5, and p35 in patient specimens were observed after immunohistochemistry. Representative images for each grade of protein levels were shown in supplemental Fig. S5. The correlations between the proteins levels of Cdk5 or p35 with AR in tumor tissues were analyzed by χ2 test. As summarized in Table 1 and supplemental Table S1, Cdk5 or p35 protein levels were shown to have positive correlations with AR levels (both p < 0.0001, χ2 = 31.05 and 28.01, respectively). Besides, the comparison of the protein levels in tumor and normal tissues was discussed. The images of one representative patient were shown in Fig. 5. AR, Cdk5, and p35 were all highly expressed in tumor tissue as compared with normal tissue. Two of seven patients fit the above findings where all three proteins were highly expressed in tumor tissues. In addition, the mean blood PSA concentration in the high-plus moderate Cdk5 groups (34.2 ± 4.32 ng/ml, n = 13) was significantly higher than the mean from the other patients with low-plus negative Cdk5 levels (16.8 ± 7.41 ng/ml, n = 16, p = 0.037). The mean blood PSA concentrations for all patients was 24.6 ± 4.49 ng/ml (n = 29). These observations imply that Cdk5-related proteins are important in the development of prostate cancer. Taken together, this clinical evidence along with the previous findings suggests that Cdk5 activation may up-regulate AR protein, contributing to prostate cancer progression.

TABLE 1.

Correlations between Cdk5 and AR protein expressions in human prostate cancer tissues

| Expression level | Cdk5, n |

Total n | P, χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative, low | Moderate, high | |||

| % | ||||

| AR | < 0.0001a | |||

| Low | 54 (31) | 9 (5) | 63 | (31.05) |

| Moderate | 35 (20) | 42 (24) | 77 | |

| High | 14 (8) | 23 (13) | 27 | |

| Total n | 103 | 74 | 177 | |

a p < 0.05, statistically significant.

FIGURE 5.

Identification of AR, Cdk5, and p35 protein levels in patient specimens. Representative sections of normal prostate tissues and tumor prostate tissues were immunohistochemically stained with specific antibodies against AR, Cdk5, and p35 (brown signals). The scale bar represents 200 μm. The inset panels indicate the fields with larger magnification (scale bar, 25 μm).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we propose that Cdk5 regulates AR by stabilizing AR proteins through phosphorylation. Our evidence indicates that Cdk5-dependent AR regulation might be important for prostate cancer cell growth. AR, as a transcription factor, plays a crucial role in prostate cancer cells, and its regulation becomes essential to investigate. Since the roles of Cdk5 were sequentially discovered, Cdk5 may be an important player in numerous biological processes (28, 29).

In addition to ligand-dependent regulation, post-translational modification of AR in prostate cancer cells has also been extensively investigated (30). Several lines of evidence have indicated that AR phosphorylation at serine or tyrosine sites mediate AR function (5, 8, 31–34). The existence of AR Ser-81 phosphorylation is highly correlated to androgen administration (4). However, Akt is reported not to be the kinase that responds to AR Ser-81 phosphorylation due to the analysis of phosphorylation consensus sequence sites (35). Although the Ser-81 site occurs in the consensus sequence of protein kinase C (PKC), PKC inhibitors fail to reduce AR Ser-81 phosphorylation (4). Recent evidence indicates that stromal cell-derived factors cause AR Ser-81 phosphorylation and modulate prostate cancer cell growth through the Erk pathway (36). Other kinases are also reported as candidates for phosphorylating AR Ser-81 site, such as Cdk1, Cdk5 (5, 8), and Cdk9 (5). With regard to Cdk5, it has been reported to regulate the transcriptional activity of glucocorticoid receptor through phosphorylation (37). In addition, there is evidence indicating that the amino acid sequence of the N terminus of Cdk5 contains the LXXLL motif, which corresponds to the sequence that cofactors utilize for interaction with nuclear receptors (38). According to these facts and the Cdk5 phosphorylation consensus sequence (SPRT) (7), we hypothesize that Cdk5 might be responsible for AR Ser-81 phosphorylation and thereby modulate AR functions. Nevertheless, two groups suggest distinguishing opinions (5, 8). Chen et al. (8) utilize p25 as a Cdk5 activator and find that Cdk5/p25 fails to increase AR Ser-81 phosphorylation. p25, a Ca2+-dependent p35 cleavage product, is more stable than p35 and abnormally regulates Cdk5 activation (39). According to our previous study in thyroid cancer, unlike p35, p25 overexpression did not increase thyroid cancer cell proliferation, although Cdk5 was activated (21). Actually, p25 is able to maximally activate Cdk5, but this kind of excessive activation is considered to be a deregulation for tumor cell growth (21). Besides, Cdk5/p25 has been reported to be correlated to cell apoptosis by our previous results (24). Thus, it might not be a good strategy to physiologically elevate Cdk5 activity by using p25. On the other hand, the results of an in vitro kinase assay by Gordon et al. (5) indicate that AR Ser-81 is phosphorylated by Cdk9 other than Cdk5. Compared with our experimental conditions, our whole experiments were conducted in the presence of androgen treatment. Our data are the first demonstration indicating the endogenous Cdk5-AR biochemical interaction (Fig. 1A) and Cdk5-dependent Ser-81 phosphorylation of endogenous AR in human prostate cancer cells (Fig. 1, B and C, and supplemental Fig. S1B). Importantly, Ser-81 was a major site for Cdk5-AR interaction, as the S81A mutant extremely blocked this interaction (Fig. 1E). In addition, the interactions between Cdk5 and AR in prostate cancer cells were correlated to the status of Cdk5 activation (Fig. 1B), which was in accordance with our previous studies on Abl kinase (12) in which the interaction between kinase and substrate was determined by kinase activity.

On the other hand the role of ubiquitin-proteasome degradation is important in transcriptional regulation (40), and the ubiquitin-ligase E6-associated protein may be a cofactor of steroid receptors (41). We found that Cdk5-dependent phosphorylation of AR protects ubiquitin-proteasome degradation of AR (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S2). Corresponding to the latest report that indicates the link of Ser-81 and AR stability (34), Cdk5 activation may stabilize AR protein through Ser-81 phosphorylation. With regard to subcellular localization, Cdk5 has been proven to shuttle into the nuclei and phosphorylate MEF2, thereby affecting neuronal cell fate (42). Our data suggest that Cdk5 might cause accumulation of AR protein in the nucleus through phosphorylation (Fig. 3, A and B, and supplemental Fig. S3B). In addition, p35 protein was also reported to translocate into nuclei via a direct interaction with importins without associating with Cdk5 (43). This finding suggests that p35 may enter the nucleus by itself and activate nuclear Cdk5 and subsequently result in Ser-81 phosphorylation of nuclear AR. This evidence corresponds with previous results indicating the nuclear localization of phospho-Ser-81 AR (44). Intriguingly, our results exhibited that the nuclear distributions of both AR and Cdk5 were simultaneously affected by S81A mutation (Fig. 3B). It needs to be further investigated whether these two proteins interact with each other in the nucleus or interact in the cytosol and subsequently translocate into nucleus. Corresponding to Fig. 1E, we thought that the interaction between AR and Cdk5 might mainly exist in the nucleus. Therefore, we hypothesize that Cdk5-dependent AR Ser-81 phosphorylation might cause AR itself to accumulate in the nucleus and protect AR from degradation. In addition, Cdk5-triggered AR transactivation in the presence of R1881 was also identified (Fig. 3C). Cdk5 increased not only PSA expression but also PSA secretion in the presence of R1881 (Fig. 3D). Because Cdk5 enables the regulation of exocytosis (45), it is possible that Cdk5 could regulate the secretion of intracellular PSA. Finally, the relevance of Cdk5-dependent AR regulation on the proliferation of prostate cancer cells was investigated (Fig. 4). Our results agreed with others in which wild-type AR positively regulates prostate cancer cell proliferation but S81A mutant inhibits (5). They also mention that S81A mutant AR is lost with cell passage, probably due to selection against the phospho-null mutant (5). Collectively these studies underscore that Ser-81 phosphorylation of AR proteins is required to cell growth stimulation of prostate cancer. In summary, our results provide evidence indicating that Cdk5 may transduce signals into the nuclei of prostate cancer cells and regulate AR to promote cell proliferation.

Overexpression of cdk5 has been shown in lung cancer (20). The single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the cdk5 promoter was also found and correlated with an increased risk of lung cancer (18). The latest study indicates the association between Cdk5/p35 protein expressions and clinicopathologic parameters in non-small cell lung cancer, whereas the poor prognosis in Cdk5/p35-positive patients has also been shown (19). On the other hand, p35, which results in Cdk5 activation, was found to be expressed in 87.5% of metastatic prostate cancer patients (25). This evidence lead us to hypothesize that Cdk5 may play a role in the progression of prostate cancer. In our findings five of eight patient specimens contained higher Cdk5 proteins in tumor sections than normal ones. The significant correlations of protein levels between individual Cdk5 or p35 to AR were found (both p < 0.0001, Table 1 and supplemental Table S1). Besides, the mean blood PSA concentration from patients who had higher protein levels of Cdk5 was higher than that from left patients. These clinical evidences support our in vitro findings which demonstrate that Cdk5 is a regulator to AR protein levels. Taken together, we propose that Cdk5 activation may play an important role in the development of prostate cancer.

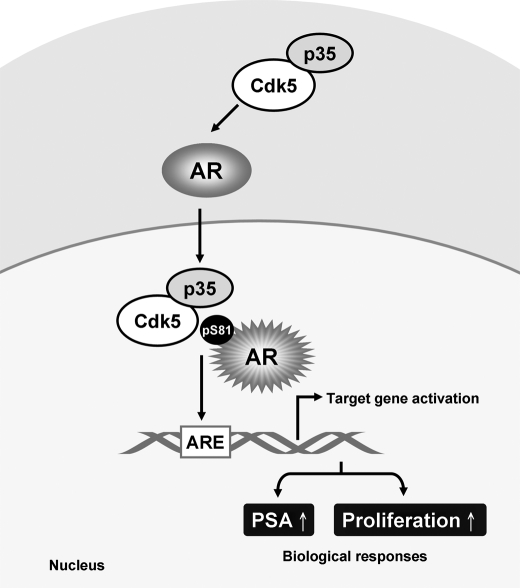

In conclusion, we collect several lines of evidence from in vitro, in vivo, and clinical data describing the way in which AR is activated by Cdk5-dependent pathway. These findings illustrate that Cdk5/p35 contributes to prostate cancer growth by regulating AR stability through Ser-81 phosphorylation and lead us to hypothesize that Cdk5/p35 may play a decisive role in the development of prostate cancer (Fig. 6). Taken together with the findings of Cdk5 in the metastasis of prostate cancer (25) and androgen production (23), we believe that Cdk5 and p35 may become therapeutic and diagnostic targets of prostate cancer in the near future.

FIGURE 6.

The schematic representation illustrates that Cdk5 and p35 may regulate AR through specific phosphorylation. Cdk5 increases AR transcriptional activity through AR protein stabilization. The final outcome of the Cdk5-dependent regulation is the support of prostate cancer cell proliferation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. S. L. Hsu and M. C. Liu (Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taiwan) for full support, Dr. M. T. Lai (Chang Bing Show Chawn Memorial Hospital, Taiwan) for help with the immunohistochemical analysis, Dr. K. C. Lin (National Taipei College of Nursing, Taiwan) for help with the statistical analysis, Dr. H. C. Chen, Dr. T. H. Lee, Dr. Y. M. Liou, Dr. J. W. Chen, and Dr. H. C. Cheng (National Chung Hsing University, Taichung, Taiwan) for technical support, Dr. P. S. Wang (National Yang Ming University, Taiwan), Dr. D. Gioeli (University of Virginia Health System), Dr. G. Jenster (Josephine Nefkens Institute, The Netherlands), and Dr. C. S. Chang (University of Rochester Medical Center) for providing experimental materials. RNAi reagents (shcdk5 TRCN0000021467, shp35 TRCN0000006217 and shgfp TRCN0000072178) were obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility located at the Institute of Molecular Biology/Genomic Research Center, Academia Sinica, supported by the National Research Program for Genomic Medicine Grants of the National Science Council (NSC 97-3112-B-001-016).

This work was supported by National Science Council Grants NSC97-2320-B-005-002-MY3 and NSC96-2628-B-005-013-MY3 and in part by the Taiwan Ministry of Education under the Aiming for the Top University plan.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S5.

F.-N. Hsu, M.-C. Chen, M.-C. Chiang, E. Lin, Y.-T. Lee, P.-H. Huang, G.-S. Lee, and H. Lin, unpublished data.

- AR

- androgen receptor

- Cdk5

- cyclin-dependent kinase 5

- PSA

- prostate-specific antigen

- Rv

- roscovitine

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescence protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Rhim J. S., Kung H. F. (1997) Crit. Rev. Oncog. 8, 305–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Isaacs J. T., Isaacs W. B. (2004) Nat. Med. 10, 26–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Blom N., Gammeltoft S., Brunak S. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 294, 1351–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gioeli D., Ficarro S. B., Kwiek J. J., Aaronson D., Hancock M., Catling A. D., White F. M., Christian R. E., Settlage R. E., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Weber M. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 29304–29314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gordon V., Bhadel S., Wunderlich W., Zhang J., Ficarro S. B., Mollah S. A., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D. F., Xenarios I., Hahn W. C., Conaway M., Carey M. F., Gioeli D. (2010) Mol. Endocrinol. 24, 2267–2280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsu F. N., Yang M. S., Lin E., Tseng C. F., Lin H. (2011) Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 300, E902–E908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fu A. K., Fu W. Y., Ng A. K., Chien W. W., Ng Y. P., Wang J. H., Ip N. Y. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6728–6733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chen S., Xu Y., Yuan X., Bubley G. J., Balk S. P. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15969–15974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hellmich M. R., Pant H. C., Wada E., Battey J. F. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 10867–10871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tsai L. H., Delalle I., Caviness V. S., Jr., Chae T., Harlow E. (1994) Nature 371, 419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen M. C., Lin H., Hsu F. N., Huang P. H., Lee G. S., Wang P. S. (2010) Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 299, C516–C527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lin H., Lin T. Y., Juang J. L. (2007) Cell Death Differ. 14, 607–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Selvendiran K., Koga H., Ueno T., Yoshida T., Maeyama M., Torimura T., Yano H., Kojiro M., Sata M. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 4826–4834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim E., Chen F., Wang C. C., Harrison L. E. (2006) Int. J. Oncol. 28, 191–194 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feldmann G., Mishra A., Hong S. M., Bisht S., Strock C. J., Ball D. W., Goggins M., Maitra A., Nelkin B. D. (2010) Cancer Res. 70, 4460–4469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Goodyear S., Sharma M. C. (2007) Exp. Mol. Pathol. 82, 25–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Upadhyay A. K., Ajay A. K., Singh S., Bhat M. K. (2008) Curr. Cancer Drug. Targets 8, 741–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Choi H. S., Lee Y., Park K. H., Sung J. S., Lee J. E., Shin E. S., Ryu J. S., Kim Y. H. (2009) J. Hum. Genet. 54, 298–303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu J. L., Wang X. Y., Huang B. X., Zhu F., Zhang R. G., Wu G. (2011) Med. Oncol. 28, 673–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lockwood W. W., Chari R., Coe B. P., Girard L., Macaulay C., Lam S., Gazdar A. F., Minna J. D., Lam W. L. (2008) Oncogene 27, 4615–4624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin H., Chen M. C., Chiu C. Y., Song Y. M., Lin S. Y. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2776–2784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuo H. S., Hsu F. N., Chiang M. C., You S. C., Chen M. C., Lo M. J., Lin H. (2009) Chin. J. Physiol. 52, 23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lin H., Chen M. C., Ku C. T. (2009) Endocrinology 150, 396–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lin H., Juang J. L., Wang P. S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29302–29307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Strock C. J., Park J. I., Nakakura E. K., Bova G. S., Isaacs J. T., Ball D. W., Nelkin B. D. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 7509–7515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Berger R., Lin D. I., Nieto M., Sicinska E., Garraway L. A., Adams H., Signoretti S., Hahn W. C., Loda M. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 5723–5728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sheflin L., Keegan B., Zhang W., Spaulding S. W. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 276, 144–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dhavan R., Tsai L. H. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 749–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin H. (2009) Adapt. Med. 1, 22–25 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gelmann E. P. (2002) J. Clin. Oncol. 20, 3001–3015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gioeli D., Black B. E., Gordon V., Spencer A., Kesler C. T., Eblen S. T., Paschal B. M., Weber M. J. (2006) Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 503–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen S., Kesler C. T., Paschal B. M., Balk S. P. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 25576–25584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Guo Z., Dai B., Jiang T., Xu K., Xie Y., Kim O., Nesheiwat I., Kong X., Melamed J., Handratta V. D., Njar V. C., Brodie A. M., Yu L. R., Veenstra T. D., Chen H., Qiu Y. (2006) Cancer Cell 10, 309–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liu S., Yuan Y., Okumura Y., Shinkai N., Yamauchi H. (2010) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 394, 297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mellinghoff I. K., Vivanco I., Kwon A., Tran C., Wongvipat J., Sawyers C. L. (2004) Cancer Cell 6, 517–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shigemura K., Isotani S., Wang R., Fujisawa M., Gotoh A., Marshall F. F., Zhau H. E., Chung L. W. (2009) Prostate 69, 949–955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kino T., Ichijo T., Amin N. D., Kesavapany S., Wang Y., Kim N., Rao S., Player A., Zheng Y. L., Garabedian M. J., Kawasaki E., Pant H. C., Chrousos G. P. (2007) Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 1552–1568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Heery D. M., Kalkhoven E., Hoare S., Parker M. G. (1997) Nature 387, 733–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Patrick G. N., Zukerberg L., Nikolic M., de la Monte S., Dikkes P., Tsai L. H. (1999) Nature 402, 615–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lipford J. R., Deshaies R. J. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 845–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nawaz Z., Lonard D. M., Smith C. L., Lev-Lehman E., Tsai S. Y., Tsai M. J., O'Malley B. W. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 1182–1189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gong X., Tang X., Wiedmann M., Wang X., Peng J., Zheng D., Blair L. A., Marshall J., Mao Z. (2003) Neuron 38, 33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fu X., Choi Y. K., Qu D., Yu Y., Cheung N. S., Qi R. Z. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 39014–39021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kesler C. T., Gioeli D., Conaway M. R., Weber M. J., Paschal B. M. (2007) Mol. Endocrinol. 21, 2071–2084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lilja L., Yang S. N., Webb D. L., Juntti-Berggren L., Berggren P. O., Bark C. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34199–34205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.