Background: Calmodulin interacts with the HIV-1 Gag protein in infected cells.

Results: The minimal calmodulin binding domain of Gag has been identified.

Conclusion: Residues 8–43 of MA are important for CaM binding.

Significance: Our findings may help in identification of the functional role of CaM-Gag interactions in the HIV replication cycle.

Keywords: Calmodulin, Circular Dichroism (CD), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry, Mass Spectrometry (MS), NMR, Peptide Interactions, Virus Assembly

Abstract

Subcellular distribution of Calmodulin (CaM) in human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1)-infected cells is distinct from that observed in uninfected cells. CaM has been shown to interact and co-localize with the HIV-1 Gag protein in infected cells. However, the precise molecular mechanism of this interaction is not known. Binding of Gag to CaM is dependent on calcium and is mediated by the N-terminal-myristoylated matrix (myr(+)MA) domain. We have recently shown that CaM binding induces a conformational change in the MA protein, triggering exposure of the myristate group. To unravel the molecular mechanism of CaM-MA interaction and to identify the minimal CaM binding domain of MA, we devised multiple approaches utilizing NMR, biochemical, and biophysical methods. Short peptides derived from the MA protein have been examined. Our data revealed that whereas peptides spanning residues 11–28 (MA-(11–28)) and 31–46 (MA-(31–46)) appear to bind preferentially to the C-terminal lobe of CaM, a peptide comprising residues 11–46 (MA-(11–46)) appears to engage both domains of CaM. Limited proteolysis data conducted on the MA-CaM complex yielded a MA peptide (residues 8–43) that is protected by CaM and resistant to proteolysis. MA-(8–43) binds to CaM with a very high affinity (dissociation constant = 25 nm) and in a manner that is similar to that observed for the full-length MA protein. The present findings provide new insights on how MA interacts with CaM that may ultimately help in identification of the functional role of CaM-Gag interactions in the HIV replication cycle.

Introduction

Retroviruses encode a major structural protein called Gag, which is capable of self-assembling to form virus-like particles in vitro in the absence of any viral or cellular constituents (1, 2). Assembly of HIV-12 Gag occurs predominantly on the plasma membrane (PM), a step that is indispensable for proper and efficient assembly to produce progeny virions (3–18). Subsequent to virus assembly and budding, the virus undergoes a major morphological reorganization upon cleavage of the Gag polypeptides into several domains including the myristoylated matrix (myr(+)MA), capsid, and nucleocapsid proteins (3, 4, 17–19). Among the multiple functions proposed for the MA domain, its role in mediating Gag-membrane binding appears to be the most understood. Efficient binding of Gag to the PM requires a myristyl group (myr) and several basic residues localized within the N-terminal domain (3, 4, 20, 21). The ultimate localization of HIV-1 Gag on the PM is dependent on phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (22–24), a prominent phospholipid localized at the inner leaflet of the PM (25–27). Structural studies have shown that phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate binds directly to HIV-1 MA, inducing a conformational change that triggers myr exposure (28).

Although significant progress has been made in defining the viral and cellular determinants of HIV-1 assembly and release (6), the mechanistic pathway of Gag trafficking to the assembly sites in the infected cell and its intracellular interactions are poorly understood. Among many cellular factors proposed to interact with Gag during the virus replications cycle (7, 29–32), calmodulin (CaM) appears to be of a potential interest despite being the least understood. Subcellular distribution of CaM in HIV-infected cells was shown to be distinct from that observed in uninfected cells (33). CaM is a highly conserved calcium-binding protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells and is implicated in a variety of cellular functions (34–39). It can be localized in various subcellular locations, including the cytoplasm, within organelles, or associated with the plasma or organelle membranes (34–39).

Attempts to identify specific roles of CaM in virus replication and infectivity are not limited to HIV. CaM possesses a functional role in budding of Ebola virus-like particles by interacting with the viral matrix protein VP40 (40). CaM also appears to play some role in the simian immunodeficiency virus replication cycle (29, 41–45). A combination of in vivo and in vitro studies revealed that CaM interacts with the HIV-1 Gag, Nef, and the gp160 proteins (29, 41–44). HIV-1 Gag co-localizes with CaM in a diffuse pattern spread throughout the cytoplasm (29). Gag binding to CaM is mediated by the MA domain and is dependent on calcium (29). Investigation of the underlying mechanism of Gag-CaM interactions has gained some momentum recently. Our laboratory (46) and others (47) have shown that CaM binds directly to the MA protein in a calcium-dependent manner. Our NMR data revealed that binding of CaM to MA induces the extrusion of the myr group (46). However, despite the evidence that the N terminus of MA is likely to be the CaM binding domain, severe NMR signal broadening/loss did not allow for determination of the exact MA region that interacts with CaM (46).

In pioneering studies, Radding et al. (29) have shown that peptides from the N-terminal region of MA bind to CaM with variable affinities and in different modes. These studies have prompted others to conduct SAXS experiments to elucidate the overall global features of CaM bound to short peptides derived from the MA protein (48). Most recently, SAXS studies conducted on CaM complexed with full-length MA provided more insights on the global features of the complex (47). However, because of the low resolution “limitation,” SAXS methods cannot provide details on the complex interface, nor can it identify specific residues that are important for the formation and stabilization of the complex. To complement the SAXS studies and to elucidate the precise molecular mechanism of MA-CaM interactions, we devised multiple approaches utilizing NMR, biochemical, and biophysical methods. Short peptides derived from the MA protein have been examined. Our data revealed that a 36-amino acid peptide in the N-terminal region of MA spanning residues 8–43 (MA-(8–43)) constitutes the minimal CaM binding domain. We also found that this peptide binds very tightly to CaM in a manner that is very similar to that observed for the full-length MA protein.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

A plasmid encoding full-length (residues 1–148) Norvegicus rattus calmodulin was a kind gift from Madeline Shea (University of Iowa). The CaM sequence is identical (100% conserved) to the human CaM sequence (Swiss-port code P62158). To construct the MA-(8–43) clone, the MA-(8–43) coding sequence was PCR-amplified from the pNL4–3 isolate (NCBI accession code M15390) and ligated to the 3′-end of small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) gene via BamHI and XhoI sites within a pET28 vector. The resulting plasmid has a His6 tag encoded on the N terminus of SUMO. Both the SUMO plasmid and another encoding for His6-SUMO protease were kindly provided by Jin-Biao Ma (University of Alabama at Birmingham).

Protein Expression and Purification

The unmyristoylated MA (myr(−)MA) protein was expressed and purified as described (49, 50). CaM samples have been prepared as described with minor modifications (51, 52). CaM protein was expressed in Escherichia coli (BL21 Codon+ (DE3) RIL) cell line. To make unlabeled CaM, starter cells (20 ml) were grown overnight at 37 °C in LB media containing ampicillin (100 mg/liter). Next day, cells were transferred to 2 liters of LB media (100 mg/liter ampicillin) and grown until A600 reached ∼0.6–0.7, induced with 1 mm isopropyl-d-thiogalactoside and grown for 4 h. Cells were then harvested, spun down at 5000 rpm, and stored overnight at −80 °C. The next day the cell pellet was resuspended in 60 ml (30 ml/liter cell culture) of a buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.2 and 1 mm EDTA. Cells were then sonicated, and cell lysate was spun down at 17,000 rpm for 30 min. The CaM-containing supernatant was then purified using an ion-exchange column (Q column, GE Healthcare). Fractions containing CaM protein were pooled and dialyzed overnight in a buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.4 and 10 mm CaCl2 (wash buffer A). The dialyzed sample was loaded on phenyl-Sepharose column (GE Healthcare), and the CaM protein was extensively washed with wash buffer A followed by wash buffer B (20 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.4, 500 mm NaCl, and 10 mm CaCl2) and another round with wash buffer A. CaM protein was then eluted with a buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.4 and 10 mm EDTA. CaM samples were stored at −20 °C in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris at pH 7.0 and 10 mm CaCl2. Protein purity was verified by SDS-PAGE. Uniformly 15N- and 13C-labeled CaM samples were prepared according to a previously described protocol (53) and purified as described above for the unlabeled sample.

The His6-SUMO-MA-(8–43) protein was expressed in the E. coli (BL21 Codon+ (DE3) RIL) cell line. To make the unlabeled sample of MA-(8–43) peptide, the His6-SUMO-MA-(8–43) starter cells (20 ml) were grown overnight at 37 °C in LB media containing kanamycin (50 mg/liter). The next day cells were transferred to 2 liters of LB media (50 mg/liter kanamycin) and grown until A600 reached ∼0.6–0.7, induced with 1 mm isopropyl-d-thiogalactoside, and grown for 4 h. Cells were then harvested, spun down at 5000 rpm, and stored overnight at −80 °C. The next day the His6-SUMO-MA-(8–43) cell pellet was resuspended in 40 ml of lysis buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8, 500 mm NaCl, and 20 mm imidazole. Cells were sonicated, and cell lysate was spun down at 17,000 rpm for 30 min. The supernatant was then loaded on nickel resin (Thermo Scientific), and protein was washed and eluted on FPLC (Bio-Rad) using a gradient protocol (elution buffer: 25 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8, 500 mm NaCl, and 500 mm imidazole). FPLC fractions were then pooled and dialyzed overnight in a buffer containing 25 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8 and 250 mm NaCl. The MA-(8–43) peptide was cleaved by SUMO protease (at 1:1000 protease:protein) and purified via nickel affinity and gel filtration chromatography methods. SUMO protease was expressed and purified as described (54). 15N-labeled samples of MA-(8–43) were prepared as described (53). The molecular mass of MA-(8–43) was confirmed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (Mmeas:Mcalc = 4390.47:4390.45). Synthetic MA peptides for residues 11–28 (MA-(11–28)), 31–46 (MA-(31–46)), and 11–46 (MA-(11–46)) were >95% pure and used as received (Genscript, Piscataway, NJ).

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR data were collected at 35 °C on a Bruker Avance II (700 MHz 1H) spectrometer equipped with a cryogenic triple-resonance probe, processed with NMRPIPE (55), and analyzed with NMRVIEW (56). All NMR samples were prepared in buffer containing 50 mm Tris-d11, pH 6.3, 100 mm NaCl, and 10 mm CaCl2. 1H, 13C, and 15N NMR chemical shifts for CaM have been assigned as described (46).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC data were collected on an Auto-iTC200 microcalorimeter (MicroCal Corp., Northampton, MA) in a buffer containing 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.0, 50 mm NaCl, and 5 mm CaCl2. In a typical experiment involving MA-(11–28) or MA-(31–46), ∼800 μm peptide was titrated into 50–80 μm CaM. For MA-(8–43) and MA-(11–46), the reciprocal titration was performed with ∼150–200 μm of CaM titrated into a cell sample containing ∼20 μm of peptide. Exothermic heats of reaction were measured at 37 °C for 19 injections. Heats of dilution were measured by titrating CaM or peptide into a buffer under identical conditions. Base-line corrections were performed by subtracting heats of dilution from the raw CaM-peptide titration data. Binding curves were analyzed, and dissociation constants were determined by nonlinear least-squares fitting of the base-line-corrected data using Origin 7.0 (MicroCal Corp.).

Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy

CD spectra were acquired on a Jasco J815 spectropolarimeter at 25 °C from 260 to 185 nm. The scanning rate was set to 50 nm/min. Loading concentrations were 70 μm for peptides (in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7) and 10 μm for CaM and the CaM-MA-(8–43) complex (in 10 mm HEPES, 50 mm KCl, and 1 mm CaCl2). The background signal from the buffer solution was subtracted from each spectrum.

Proteolysis Assay

Proteolytic digestion reactions were conducted on highly pure samples of myr(−)MA, CaM, and myr(−)MA-CaM complex in a buffer containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 100 mm NaCl, and 5 mm CaCl2. The myr(−)MA-CaM complex was made at 1:1 stoichiometry and run on a gel filtration column (Superdex 75) to ensure sample homogeneity. Protein samples were then subjected to limited proteolysis by the addition of thermolysin (from Bacillus thermoproteolyticus rokko, Sigma) at 1:1000 (enzyme:complex) stoichiometry. All experiments were performed at room temperature. Digestion reactions were monitored for 24 h via SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining.

Mass Spectrometry

To identify the peptides present in the digested samples, the CaM-MA thermolysin digests were separated on a 50 × 2-mm Synergi Fusion-RP column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with a 30-min acetonitrile gradient (0–50% containing 0.1% formic acid) and electrosprayed into a hybrid ion trap-FT ICR mass spectrometer (LTQ-FT, Thermo Finnigan, Waltham, MA). Eluting peptides were fragmented for MS/MS analysis with collision-induced dissociation fragmentation. Fragmentation spectra were annotated by a SEAQUEST search with a custom data base containing thermolysin, CaM, and MA sequences. MA peptides corresponding to residues 7–43 and 7–44 were identified by MS/MS and accurate mass analyses. The intact peptides were detected as multiple charge states (4+–10+), which when deconvoluted match the calculated mass of the peptides within 4 ppm.

RESULTS

Our recent NMR studies revealed that the majority of 1H,15N resonances corresponding to residues in the N-terminal region of MA (residues ∼2–50) exhibit significant chemical shift changes upon binding to CaM (46). However, extensive loss and/or broadening of the NMR signals precluded unambiguous identification of residues critical for binding. Here, we devised new approaches to further characterize CaM-MA interactions and identify the minimal binding domain of MA.

Binding of MA-(11–28) Peptide to CaM

In the MA protein, residues 11–19 form an α-helix (helix I), and residues 20–30 form a β-sheet (Fig. 1) (28, 49, 57, 58). Early studies suggested that a peptide made of residues 11–25 can bind to CaM with 2:1 (peptide:CaM) stoichiometry and dissociation constant of about 10−9 m (29). Subsequent SAXS data suggested that CaM adopts a dumbbell-like structure upon binding of 2 peptide molecules (residues 11–28) to the N and C termini of CaM (48). We chose MA-(11–28) as a representative peptide to understand how it interacts with CaM. The CD spectrum obtained for MA-(11–28) shows a negative band at ∼200 nm, consistent with a random coil in solution (supplemental Fig. S1). Our two-dimensional HSQC NMR data obtained for a 15N-labeled CaM as a function of added unlabeled MA-(11–28) peptide shows that a subset of signals exhibited significant chemical shift changes upon binding of MA-(11–28) (Fig. 2). Amide chemical shift changes were calculated as ΔδHN (ppm) = [(Δδ1H)2 + (Δδ15N)2]1/2, where Δδ1H and Δδ15N are the 1H and 15N amide chemical shift changes, respectively. Chemical shift mapping revealed that these signals correspond to residues in the C-terminal domain of CaM (Fig. 2). More specifically, residues Phe-89, Leu-105, Arg-106, Met-109, Thr-110, Lys-115, Met-124, Ala-128, Phe-141, Met-144, Met-145, and Thr-146 exhibited the most dramatic chemical shift changes (ΔδHN > 0.5 ppm). In comparison, only a few residues in the N-terminal domain of CaM exhibited modest chemical shift changes, suggesting that MA-(11–28) binds preferentially to the C-terminal domain of CaM. Our results sharply contrast previous studies, which have predicted binding of two MA-(11–28) molecules to both of the N- and C termini of CaM (29, 48).

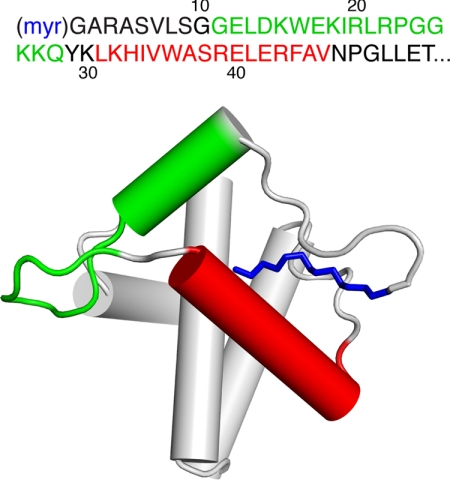

FIGURE 1.

Top, shown is the amino acid sequence of the N-terminal region of HIV-1 MA. Bottom, shown is a schematic representation of the myr(+)MA protein (PDB ID 2H3I). The peptides used in our study are color-coded (green, residues 11–28; red, residues 31–46; the myr group is shown in blue).

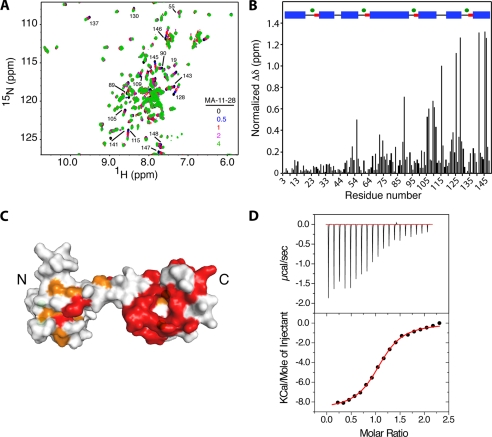

FIGURE 2.

A, shown is an overlay of two-dimensional 1H,15N HSQC spectra obtained for 15N-labeled CaM as a function of added MA-(11–28) (MA-(11–28):CaM = 0:1 (black), 0.5:1 (blue), 1:1 (red), 2:1 (magenta), and 4:1 (green)). B, shown is a histogram of normalized chemical shift changes versus residue number. Inset, secondary structure of CaM (helices, β-turns, and calcium ions are represented in blue, red, and green, respectively). C, shown is a surface representation of the calcium loaded CaM structure (PDB ID 3CLN) showing residues that exhibited substantial (>0.2 ppm) and modest (<0.2 ppm) chemical shift changes in red and orange, respectively. D, ITC data were obtained upon titration of MA-(11–28) (800 μm) into CaM (80 μm). Data best fit a one-site binding mode and afforded a Kd of 4.4 ± 0.2 μm (lower panel).

Although the NMR data suggest that only one peptide is specifically bound to the C-terminal domain of CaM, we sought to determine the stoichiometry and thermodynamic parameters of interactions by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) methods. ITC measures heat absorbed or generated upon binding and provides values for the dissociation constant (Kd), the stoichiometry (N), and the enthalpy change (ΔH°). The Kd value is then used to calculate the change in Gibbs energy (ΔG°), which together with ΔH° allows the calculation of the entropic term TΔS°. The separation of the free energy of binding into entropic and enthalpic components reveals the nature of the forces that drive the binding reaction. As shown in Fig. 2, one-site fitting of the ITC data yielded the following thermodynamic parameters: N = 1.07, Kd = 4.4 ± 0.2 μm, ΔH° = −8.76 ± 0.1 kcal/mol, and ΔS° = −3.96 cal/mol/degree. Again, the ITC results clearly show that only one MA-(11–28) molecule is able to bind to CaM. As indicated by the sign of the heat of enthalpy, CaM binding to MA-(11–28) is exothermic, suggesting that electrostatic interactions may also play a role along with the proposed hydrophobic interactions (Table 1). Of particular note, we have previously shown that CaM interactions with the full-length MA protein are mainly hydrophobic (46).

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for the binding of HIV-1 MA peptides to CaM

| Protein/peptide | Kd | ΔH | TΔS | ΔG | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | kcal/mol | kcal/mol | kcal/mol | ||

| myr(+)MAa | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 11.30 ± 0.1 | 2.32 | 8.98 | 1.08 |

| myr(−)MAa | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 12.90 ± 0.1 | 2.49 | 10.41 | 1.04 |

| MA-(11–28) | 4.4 ± 0.2 | −8.76 ± 0.1 | −0.14 | −8.62 | 1.07 |

| MA-(31–46) | 12.4 ± 2.0 | −1.94 ± 0.1 | −0.60 | −1.34 | 1.45 |

| MA-(11–46) | 0.8 ± 0.1 | −16.4 ± 0.5 | −0.88 | −15.52 | 0.89 |

| MA-(8–43) | 0.025 ± 0.001 | −21.9 ± 0.2 | −1.16 | −20.74 | 0.91 |

a From Ref. 46.

The presence of two hydrophobic surfaces on the N- and C-terminal lobes in CaM is a prominent feature that contributes to the flexibility of the protein and allows it to bind to numerous targets. These regions are only formed upon binding of Ca2+ (39). A major structural consequence of helical rearrangement is the exposure of eight methionine (Met) residues that contribute ∼46% to the solvent-accessible surface area of these two regions (59, 60). Thus, Met residues become essential for the unique promiscuous binding behavior of CaM to target proteins (60). The Met methyl groups are considered excellent “NMR reporters” to detect binding of target proteins/ligands (60–62). We have recently shown that the 13C,1H resonances of Met side chains in the N- and C-terminal lobes of CaM exhibit significant chemical shift changes upon binding to MA (46). To confirm the preferential binding of MA-(11–28) to the C-terminal lobe of CaM, we collected two-dimensional 13C,1H HMQC data on a uniformly 13C-labeled CaM sample as a function of added MA-(11–28). A selected region showing the 13Cϵ,1Hϵ signals is shown in Fig. 3. In the free state, the 13C,1H signals of all nine methionine residues are observed. The addition of a substoichiometric amount of MA-(11–28) (0.25:1 MA-(11–28):CaM) led to significant signal broadening and chemical shift changes in the 13C,1H signals of Met-109, Met-124, Met-144, and Met-145. These Met residues are located in the C-terminal hydrophobic lobe (Fig. 3). Further addition of MA-(11–28) led to sharpening of these signals at saturation points (4:1 peptide:CaM, supplemental Fig. S2). Taken together, our NMR data demonstrate that MA-(11–28) binds preferentially to the C-terminal lobe of CaM and that the Met residues are probably critical for peptide binding.

FIGURE 3.

A, an overlay of two-dimensional 13C,1H HMQC spectra shows the methionine 13Cϵ,1Hϵ signals of CaM as a function of added MA-(11–28) (MA-(11–28):CaM = 0:1 (black) and 0.25:1 (blue)). Chemical shift changes were only observed for CH3 groups in the C-terminal domain of CaM. Complete sets of titration data are shown in supplemental Fig. S2. B, shown is a surface representation of the CaM structure. Calcium ions are colored in green. Labels indicate methionine residue numbers.

Binding of MA-(31–46) Peptide to CaM

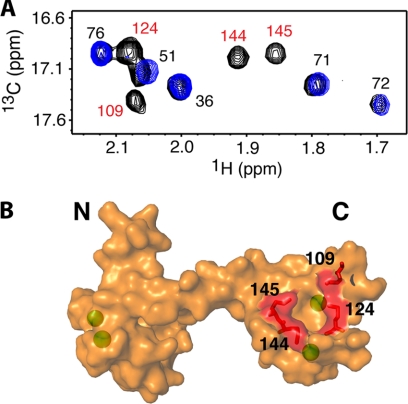

Residues 31–46 form the second α-helix (helix II) in the MA protein (Fig. 1) (28, 49, 57, 58). The CD spectrum for MA-(31–46) shows a negative band at ∼200 nm, consistent with a random coil in solution (supplemental Fig. S1). Tryptophan fluorometry studies suggested that MA-(31–46) can bind to CaM with 1:1 (peptide:CaM) stoichiometry and dissociation constant of about 10−9 m (29). To map out the interaction interface on CaM, we collected two-dimensional HSQC data on a uniformly 15N-labeled CaM as a function of added unlabeled MA-(31–46) (Fig. 4). Interestingly, the majority of the 1H,15N signals shifted upon the addition of MA-(31–46), with a subset of signals exhibiting dramatic chemical shift changes. Chemical shift mapping revealed that those signals correspond to residues located in both the N- and C-terminal domains of CaM (Fig. 4). The most significant chemical shift changes in 1H,15N resonances (Δδ > 0.5 ppm) were observed for residues Ser-17, Phe-19, Leu-48, Val-55, Met-72, Ala-73, Arg-74, Arg-86, Asp-93, Asn-97, Arg-106, Met-109, Thr-110, Asn-111, Lys-115, Val-121, Ala-128, Phe-141, Met-144, Met-145, and Thr-146. Although several residues in CaM are commonly perturbed upon binding of both MA-(11–28) and MA-(31–46), numerous others were more specifically perturbed upon binding of MA-(31–46). ITC data obtained for CaM binding to MA-(31–46) revealed a Kd of 12.4 μm (Fig. 4). As observed for MA-(11–28), the interaction is exothermic and enthalpically driven (Table 1). Of particular note, the N value obtained by ITC data fitting (1.46) is slightly higher than the expected 1:1 stoichiometry. This small difference is attributed to the formation of relatively viscous peptide solution at the experimental conditions (∼800 μm). Taken together, our data suggest that MA-(11–28) and MA-(31–46) peptides bind to CaM with different affinities and interaction interface.

FIGURE 4.

A, shown is an overlay of two-dimensional 1H,15N HSQC spectra obtained for 15N-labeled CaM as a function of added MA-(31–46) (MA-(31–46):CaM = 0:1 (black), 0.5:1 (blue), 1:1 (red), 2:1 (magenta), and 4:1 (green)). B, shown is a histogram of normalized chemical shift changes versus residue number. C, a surface representation of the CaM structure shows residues that exhibited substantial (>0.2 ppm) and modest (<0.2 ppm) chemical shift changes in red and orange, respectively. D, ITC data were obtained upon titration of MA-(31–46) (800 μm) into CaM (50 μm). Data best fit one-site binding mode and afforded a Kd of 12.4 ± 2.0 μm (lower panel).

Interactions between MA-(11–46) and CaM

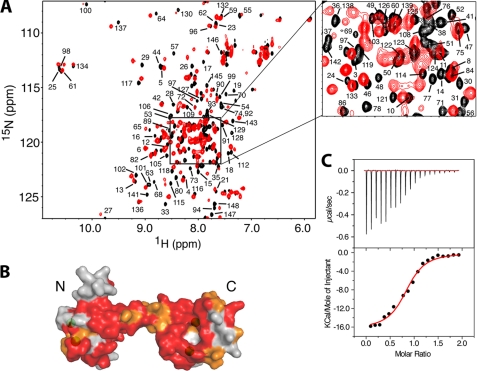

Our data described above clearly indicate that both MA-(11–28) and MA-(31–46) bind to the CaM protein with a 1:1 stoichiometry but with different binding modes. It appears, though, that the C-terminal domain of CaM is the site of docking for both peptides. Next, we monitored the interactions between CaM and MA-(11–46) by similar NMR and ITC methods. At substoichiometric amount of MA-(11–46) (0.5:1 MA-(11–46):CaM), the majority of the 1H,15N resonances in the two-dimensional HSQC spectrum (data no shown) became very broad or disappeared but became sharper as more doses of MA-(11–46) were added. Representative 1H,15N HSQC spectra for 15N-labeled CaM in the unbound form and in complex with MA-(11–46) at 1.4:1 (MA-(11–46):CaM) show that the vast majority of signals exhibited significant chemical shift changes (Fig. 5). No changes in the spectrum were observed upon further addition of MA-(11–46). In contrast to what was observed for MA-(11–28) and MA-(31–46), whereby exchange between free and bound states is fast on the NMR scale, exchange is slow for MA-(11–46) binding to CaM.

FIGURE 5.

A, shown is an overlay of two-dimensional 1H,15N HSQC spectra obtained for 15N-labeled CaM in the free state, (black) and in complex with MA-(11–46) (red). B, a surface representation of the CaM structure shows residues that exhibited substantial (>0.2 ppm) and modest (<0.2 ppm) chemical shift changes in red and orange, respectively. C, ITC data obtained upon titration of CaM (200 μm) into MA-(11–46) (20 μm) are shown. Data best fit one-site binding mode and afforded a Kd of 0.78 ± 0.15 μm (lower panel).

Interestingly, residues that exhibited substantial chemical shift changes are not localized in a well defined region of the CaM protein but, rather, spread throughout the N- and C-terminal lobes as well as the central helix. A surface representation of the CaM protein highlighting residues that exhibited chemical shift changes upon binding of MA-(11–46) is shown in Fig. 5. Strikingly, these chemical shift perturbations are very similar to those observed upon binding of full-length MA to CaM (46), which suggests that the minimal CaM binding domain of MA is likely to be localized within residues 11–46. Perturbations of the vast majority of amide signals may suggest an engagement of a wide interacting interface or induction of significant conformational changes in CaM upon binding to MA-(11–46).

The slow exchange between free and bound states on the NMR scale suggests a tighter binding of MA-(11–46) to CaM than that observed for MA-(11–28) and MA-(31–46). To determine the binding affinity and thermodynamic parameters, interactions between CaM and MA-(11–46) were monitored by ITC. As shown in Fig. 5, one-site fitting of the ITC data yielded the following thermodynamic parameters: Kd = 0.8 ± 0.1 μm, ΔH° = −16.4 ± 0.5 kcal/mol, and ΔS° = −25.2 cal/mol/degree. Consistent with the NMR data, MA-(11–46) binds CaM tighter than MA-(11–28) and MA-(31–46) (Table 1). From the sign of the heat of enthalpy, CaM binding to MA-(11–46) is exothermic, suggesting that along with the proposed hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic interactions may also play a role.

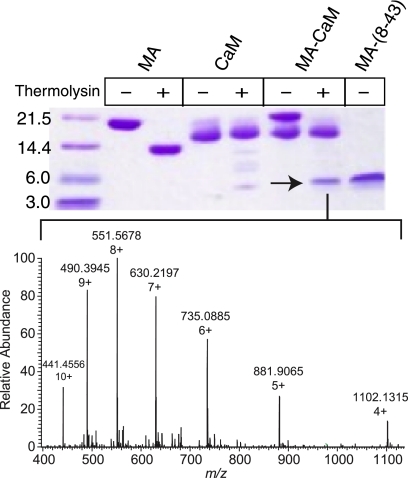

Limited Proteolysis Reveals the Minimal CaM Binding Domain of MA

Because various MA peptides with distinct sequence compositions and different lengths can bind to CaM with variable affinity, we sought to determine the minimal CaM binding domain by utilizing a proteolytic digestion assay followed by analysis with mass spectrometry. Digestion reactions were conducted on the myr(−)MA-CaM complex as well as unbound myr(−)MA and CaM. The complex was subjected to limited proteolysis by the addition of thermolysin (from B. thermoproteolyticus rokko) at 1:1000 (enzyme:complex) molar ratio (see “Experimental Procedures” for more details). After 2 h, the MA protein was readily cleaved, whereas the CaM protein was intact (Fig. 6). Digestion of the complex has resulted in an ∼5-kDa MA peptide that was resistant to proteolysis. Analysis of the digestion products by mass spectrometry revealed that the abundant MA species that was resistant to proteolysis is a peptide spanning residues 7–43 with monoisotopic mass of 4403.47 Da (Fig. 6) as identified by both exact mass measurements and tandem mass spectrometric sequencing. Another closely related minor species for residues 7–44 was also detected (supplemental Fig. S3). On the other hand, digestion of unbound MA resulted in a cleavage of a flexible helix on the C-terminal domain leaving intact residues 1–114 (Fig. 6). No significant cleavage was observed for the CaM protein either in the free or MA-bound states. Taken together, our results demonstrate that MA residues 7–43 constitute the minimal CaM binding domain. In addition, it appears that when compared with the unbound MA protein, CaM binding to MA induced significant conformational changes that facilitated cleavage by thermolysin.

FIGURE 6.

Top, shown is SDS-PAGE of thermolysin proteolysis reactions of MA, CaM, and their complex. The arrow indicates an abundant MA peptide that is resistant to proteolysis. Bottom, shown is a mass spectrum of MA-7–43, a major MA product from the reaction described above. The peptide containing residues 7–43 of MA was observed as multiple charge states (4+–10+) and verified by MS/MS fragmentation. Deconvolution of the charge state distribution produces a monoisotopic mass of 4403.4755 Da, in agreement with the calculated mass (<4 ppm error).

Characterization of MA-(8–43) Binding to CaM

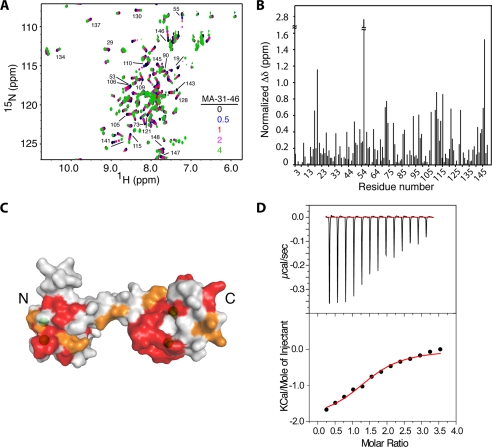

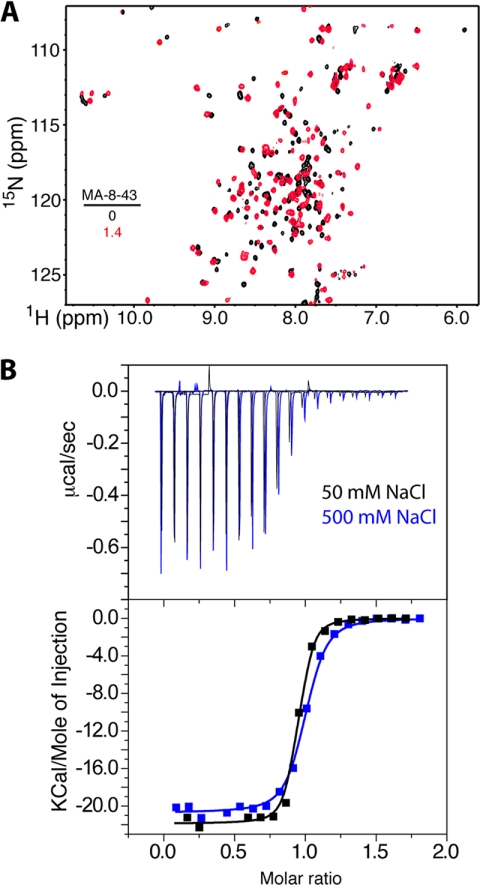

Proteolysis data clearly indicate that MA residues 7–43 are protected upon binding to CaM. To elucidate the binding mode, a peptide made of residues 8–43 was expressed and purified as a SUMO fusion protein then cleaved by using SUMO protease. Cleavage of the SUMO tag left a non-native serine residue on the N terminus. We refer to this 36-amino acid peptide as MA-(8–43) because residues 8–43 are native. NMR, ITC, and CD methods were employed to characterize the interactions between MA-(8–43) and CaM. Two-dimensional HSQC NMR data were obtained for a 15N-labeled sample of CaM as a function of added MA-(8–43). At a substoichiometric amount of MA-(8–43) (0.5:1 MA-(8–43):CaM), the majority of the 1H,15N resonances in the HSQC spectrum (data no shown) became very broad or disappeared but became sharper as further amounts of MA-(8–43) were added. These results confirm a slow exchange between the free and bound states of CaM. Representative 1H,15N HSQC spectra obtained for 15N-labeled CaM in the unbound form and in complex with MA-(8–43) at 1.4:1 (MA-(8–43):CaM) show that the vast majority of 1H,15N signals exhibited significant chemical shift changes (Fig. 7). No changes in the spectrum were observed upon further additions of MA-(8–43). To determine whether MA-(8–43) binds to CaM in a manner similar to that observed for the full-length MA protein, we compare HSQC spectra of 15N-labeled CaM when bound to myr(+)MA to that bound to MA-(8–43) (supplemental Fig. S4). Interestingly, chemical shift changes are similar, indicating that MA-(8–43) binds to CaM in a manner that is very similar to that of the full-length MA protein.

FIGURE 7.

A, shown is an overlay of two-dimensional 1H,15N HSQC spectra obtained for a 15N-labeled CaM in the free state (black) and in complex with MA-(8–43) (red). B, shown are ITC data obtained upon titration of CaM (200 μm) into MA-(8–43) (20 μm) at 50 mm (black) and 500 mm (blue) NaCl concentrations; data best fit the one-site binding mode and afforded Kd values of 25 and 60 nm, respectively (lower panel).

ITC was used to monitor MA-(8–43) binding to CaM. Thermodynamic data revealed that MA-(8–43) binds to CaM with 1:1 stoichiometry (Fig. 7). Strikingly, the binding affinity is much tighter (Kd = 25 nm) than that observed for all peptides described above (Table 1). What is even more intriguing is that the binding affinity of MA-(8–43) to CaM is 32-fold tighter than that of MA-(11–46), suggesting that residues Leu-8, Ser-9, and Gly-10 of MA contribute to the stabilization of the complex. As observed for all the peptides above, MA-(8–43) interaction with CaM is enthalpy-driven.

As described above, although the two hydrophobic surfaces on the N- and C-terminal lobes are considered key to target protein binding, additional electrostatic interactions could also stabilize CaM-protein interactions (38, 41, 42, 63, 64). To assess the role of electrostatic and hydrophobic factors, ITC data were obtained for MA-(8–43) as titrated with CaM at high salt concentration (500 mm NaCl). Our data revealed that the binding affinity (Kd = 60 nm) is only reduced by ∼2-fold upon increasing the salt concentration from 50 to 500 mm (Fig. 7), indicating that electrostatic interactions are not important in stabilizing the CaM-MA-(8–43) complex. This result is also consistent with that obtained for CaM binding to the full-length MA protein (46), indicating that interactions between CaM and MA-(8–43) are mainly hydrophobic.

Far-UV CD spectra of CaM, MA-(8–43), and their complex have been obtained to determine whether formation of the complex induces any major changes in the secondary structures of the peptide or CaM (supplemental Fig. S5). The CD spectrum of the free peptide displays a negative band at ∼200 nm, consistent with a random coil, whereas that of the CaM protein shows two minima at 208 and 222 nm, consistent with a helical structure of the protein. The CD spectrum of the complex is similar to that of the CaM protein, with features distinctive of α-helical type (supplemental Fig. S5). Binding of MA-(8–43) results only in a slight increase of CD minima of CaM, suggesting an increase in the α-helical character. Induction of the α-helical character of the peptide upon binding to CaM has been confirmed by NMR. The two-dimensional HSQC data obtained for a 15N-labeled MA-(8–43) shows a narrow dispersion of the amide proton resonances, indicating a lack of ordered structure (supplemental Fig. S6). Upon binding of CaM, almost all 1H,15N signals of MA-(8–43) exhibited substantial chemical shift changes resulting in large chemical shift dispersion, which indicates that the peptide adopts an ordered structure upon binding to CaM. Thus, it is very likely that MA-(8–43) forms a helical structure upon binding to CaM.

To assess whether the hydrophobic domains of CaM are involved in MA binding, we collected two-dimensional 13C,1H HMQC data on a 13C-labeled CaM sample in the absence or presence of MA-(8–43) (supplemental Fig. S7). The majority of 13C,1H resonances of Met residues shifted upon peptide binding. The 13Cϵ,1Hϵ resonances of Met residues 71, 76, 109, 144, and 145 exhibited the most significant chemical shift changes. These results indicate that binding of the MA-(8–43) peptide to CaM is likely to occur on both hydrophobic batches on the N- and C-terminal lobes.

DISCUSSION

CaM is a highly conserved calcium-binding protein expressed in all eukaryotic cells and is implicated in a variety of cellular functions (34–39). Structural and biophysical investigation of CaM interactions with cellular proteins and peptides is central to understanding its biological function (34, 65–67). CaM is known to interact with more than 100 distinct target proteins (34, 68, 69). We have recently shown that CaM interacts directly with the myr(+)MA protein, inducing a conformational change that triggers myr exposure (46). In previous studies, efforts were focused on elucidating global features of CaM complexed with synthetic peptides, but no attempts have been made to identify the actual binding motif of MA (29, 48). In fact, the assumption that two MA-(11–28) peptides can bind to CaM has led to conflicting conclusions about the global features of the complex (47). In addition, although CaM interactions with peptides to mimic interactions with full-length proteins have been described in numerous reports, it is still possible that nonspecific contacts can occur. In this report, we have (i) identified the interaction interface of CaM bound to short peptides derived from the MA protein, (ii) shown that MA peptides bind to CaM with variable affinities and diverse modes, (iii) identified the minimal CaM binding domain of MA, (iv) shown that the MA-(8–43) peptide interacts with CaM with a very high affinity (Kd = 25 nm), and (v) provided evidence that the interactions between CaM and MA-(8–43) are enthalpy-driven and that hydrophobic interactions are important. Perhaps one of the most surprising results is the finding that CaM binds to the MA-(8–43) peptide with a much tighter affinity (32-fold) than the MA-(11–46) peptide, indicating that residues Leu-8, Ser-9, and Gly-10 of MA are probably involved in CaM binding. In addition, compared with the full-length MA protein, the higher binding affinity of MA-(8–43) is probably due to a better accommodation by the CaM protein.

Previous tryptophan fluorometry studies have shown that MA-(31–46) binds to CaM with a Kd of about 10−9 m (29). However, our ITC data presented here revealed that this peptide binds CaM with a substantially weaker affinity (12 μm). Our HSQC data show that the addition of MA-(31–46) led to incremental chemical shift changes, indicating a fast exchange between the free and bound states on the NMR scale, consistent with μm affinity. We believe that the great discrepancy in affinity between the previously reported data and our data arises from the differences in the experimental methods and conditions. It is very unlikely that the peptide concentration used in the tryptophan fluorometry studies (0.07 μm) can lead to accurate measurements of fluorescence signal intensity and, thus, determination of binding affinity. Fluorescence data reported recently for the interactions between CaM and MA have been conducted with ∼5–7 μm concentrations and yielded very similar results for the binding affinity (46, 47).

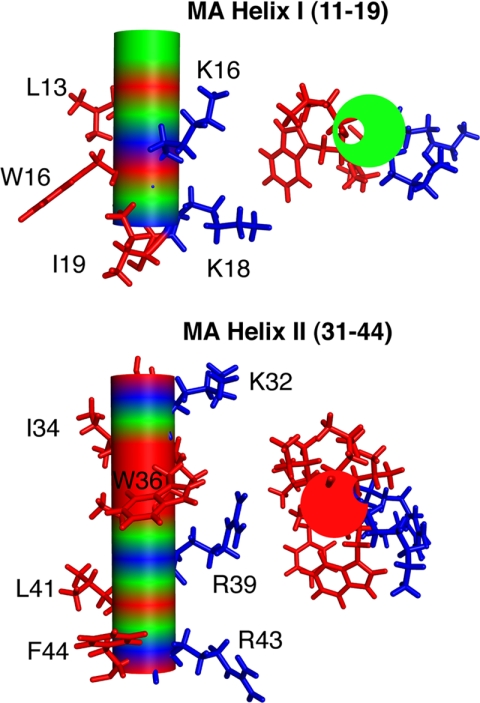

Typically, the CaM binding domain of target proteins is a short peptide (15–30 residues long) that is hydrophobic basic and has the propensity to form an α-helix (36). Indeed, the amphipathic character of CaM binding peptides is a striking feature of helices I and II of MA (Fig. 8). However, the 36-residue-long MA-(8–43) peptide is one of the largest CaM binding motifs to be discovered. In addition, the ability of MA-(8–43) to form two helices is another striking feature of this peptide as almost all known CaM target proteins usually possess a domain that is able to form only one α-helix. In many of the classical CaM binding targets, hydrophobic residues usually occupy conserved positions at 1-5-10 or 1-8-14, which point to one face of the helix (36). Although these patterns are typically found in many CaM binding proteins, numerous unclassified examples were also identified (36). Analysis of MA-(8–43) using a web-based tool to identify a sequence pattern with potential CaM-binding sites (68) yielded the highest score for residues Arg-22—Glu-40. Scores are based on several criteria including hydropathy, α-helical propensity, residue weight, residue charge, hydrophobic residue content, helical class, and occurrence of particular residues. In the three-dimensional structure of MA, residues Arg-22—Glu-40 represent the majority of helix II. However, our data show that MA-(11–28) peptide binds to CaM even more tightly than MA-(31–46) peptide (Table 1). In either case, neither of these peptides contains a motif that matches any of the known patterns of CaM-binding sites. Thus, the presence of several hydrophobic residues (Leu-13, Trp-16, and Ile-19 in helix I, and Ile-34, Val-35, Trp-36, and Ala-38 in helix II) in MA-(8–43) leads us to suggest that MA may contain a novel and unclassified CaM binding sequence. Taken together, our results combined with our recent findings (46) confirm the enormous versatility of CaM-target complex formation and suggest a novel CaM binding mode that requires engagement of hydrophobic residues from both helices I and II of MA. In summary, the MA-(8–43) peptide represents a novel target sequence that is substantially different (in length and composition) from all known CaM binding domains.

FIGURE 8.

Helixes I and II in the MA protein (cf.Fig. 1) are amphipathic. Hydrophobic residues are shown in red, and basic residues are in blue. Based on our data, hydrophobic residues are suggested to be critical for CaM binding.

Among the multiple functions of CaM is activation of several myristoylated proteins (e.g. MARCKS (myristoylated alanine-rich C kinase substrate), CAP-23/NAP-22, and HIV-1 Nef) to facilitate their intracellular localization and membrane targeting (41, 42, 63, 64). Structural studies conducted on short myristoylated peptides revealed that the myr group is involved in CaM binding, suggesting that the myr group is not only important for membrane targeting but also for mediating protein-protein interactions. However, we have recently established that although CaM acts as a trigger of myr exposure, the myr group is not involved in CaM binding (46). As shown in Fig. 1, packing of helices I and II against the other three helices is a requirement for sequestration of the myr group. Thus, it is very likely that CaM binding to MA induces a conformational change that leads to partial unpacking of helices I and II and the consequent extrusion of the myr group. Partial unfolding of the MA protein upon binding to CaM has been recently suggested by Trewhella and co-workers (47). CaM-induced unfolding of protein targets is not unusual. In some cases, this partial unfolding is considered critical for the biological function of target proteins, as in enzyme-driven cleavage reactions (70).

The N-terminal region of MA (residues 2–47) is critical for diverse Gag functions including Gag-membrane interactions, regulation of the myr switch mechanism, and binding to several cellular constituents implicated in Gag trafficking and/or gp160 incorporation (7, 17, 18, 23, 24, 28, 30, 50, 57, 71–73). Several residues in helix I of MA (Leu-8, Ser-9, Leu-13, Trp-16, Glu-17, and Lys-18) are important for gp160 incorporation (74–76), which led to the suggestion that the MA domain of Gag interacts directly with the gp160 protein via helix I (74, 77). Furthermore, Leu-8 and Ser-9 have been shown to be critical for the function of the myristyl switch mechanism and membrane binding (78–81). Subsequent structural studies revealed that substitution of Leu-8 and Ser-9 shuts off the myristyl switch mechanism, which severely inhibit Gag targeting to the PM (50). The finding that Leu-8 and Ser-9 act as stabilizing residues of the CaM-MA complex may suggest a dual role in Gag assembly.

The functional role of CaM in the HIV replication cycle could be rather more complex. Studies by Radding et al. (33) have shown that expression of the HIV-1 gp160 protein has led to a marked increase in CaM distribution. The CaM binding region was identified as a helical peptide in the gp41 protein. Deletion of this region led to diminished virus infectivity (33, 43). Confocal microscopy data confirmed the increase in CaM distribution and showed a co-localization of CaM with the gp160 protein (33). Thus, the interplay between gp160, CaM, and Gag could be an important and underestimated event in the virus replication cycle. Although it is reasonable to hypothesize that HIV-CaM protein interactions may lead to a disruption of CaM-dependent cell-signaling pathways and contribute to immune dysfunction during HIV pathogenesis, the precise functional role of CaM in the HIV replication cycle has yet to be examined.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank to Madeline Shea (University of Iowa) for providing the CaM molecular clone, Jin-Biao Ma for providing SUMO and SUMO protease plasmids, and Peter Prevelige (University of Alabama at Birmingham) and David King (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, University of California Berkeley) for helping with the mass spectrometry data. We thank the University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center x-ray core facility, funded by NCI, National Institutes of Health Grant P30CA13148, which houses the Auto-ITC200, acquired through NIH Grant 1S10RR026478.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants 1R01AI087101 (to J. S. S.), CA13148-35 (NCI; University of Alabama at Birmingham Comprehensive Cancer Center Junior Faculty Development Grant Program, to J. S. S.), and by intramural funding from the Center for AIDS Research at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7.

- HIV-1

- human immunodeficiency virus, type 1

- HIV-1 Gag

- myristoylated HIV-1 Gag polyprotein

- PM

- plasma membrane

- MA

- matrix protein

- CaM

- calmodulin

- myr(-)

- unmyristoylated protein

- myr(+)

- myristoylated protein

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- HMQC

- heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- CD

- circular dichroism

- SAXS

- small angle x-ray scattering

- SUMO

- small ubiquitin-like modifier.

REFERENCES

- 1. Campbell S., Fisher R. J., Towler E. M., Fox S., Issaq H. J., Wolfe T., Phillips L. R., Rein A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 98, 10875–10879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Campbell S., Rein A. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 2270–2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Adamson C. S., Freed E. O. (2007) Adv. Pharmacol. 55, 347–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ganser-Pornillos B. K., Yeager M., Sundquist W. I. (2008) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 18, 203–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bieniasz P. D. (2009) Cell Host Microbe 5, 550–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chu H., Wang J. J., Spearman P. (2009) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 339, 67–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dong X., Li H., Derdowski A., Ding L., Burnett A., Chen X., Peters T. R., Dermody T. S., Woodruff E., Wang J. J., Spearman P. (2005) Cell 120, 663–674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Finzi A., Orthwein A., Mercier J., Cohen E. A. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 7476–7490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gousset K., Ablan S. D., Coren L. V., Ono A., Soheilian F., Nagashima K., Ott D. E., Freed E. O. (2008) PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jouvenet N., Simon S. M., Bieniasz P. D. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 19114–19119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joshi A., Ablan S. D., Soheilian F., Nagashima K., Freed E. O. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 5375–5387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jouvenet N., Bieniasz P. D., Simon S. M. (2008) Nature 454, 236–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jouvenet N., Neil S. J., Bess C., Johnson M. C., Virgen C. A., Simon S. M., Bieniasz P. D. (2006) PLoS Biol. 4, e435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li H., Dou J., Ding L., Spearman P. (2007) J. Virol. 81, 12899–12910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Waheed A. A., Freed E. O. (2009) Virus Res. 143, 162–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Welsch S., Keppler O. T., Habermann A., Allespach I., Krijnse-Locker J., Kräusslich H. G. (2007) PLoS Pathog. 3, e36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ono A. (2010) Biol. Cell 102, 335–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ono A. (2010) Vaccine 28, B55-B59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Turner B. G., Summers M. F. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 285, 1–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ono A. (2009) Future Virol. 4, 241–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Reil H., Bukovsky A. A., Gelderblom H. R., Göttlinger H. G. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 2699–2708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ono A., Ablan S. D., Lockett S. J., Nagashima K., Freed E. O. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 101, 14889–14894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chukkapalli V., Hogue I. B., Boyko V., Hu W. S., Ono A. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 2405–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chukkapalli V., Oh S. J., Ono A. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 1600–1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Martin T. F. J. (2001) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 13, 493–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Behnia R., Munro S. (2005) Nature 438, 597–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. McLaughlin S., Murray D. (2005) Nature 438, 605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Saad J. S., Miller J., Tai J., Kim A., Ghanam R. H., Summers M. F. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 103, 11364–11369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Radding W., Williams J. P., McKenna M. A., Tummala R., Hunter E., Tytler E. M., McDonald J. M. (2000) AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 16, 1519–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lopez-Vergès S., Camus G., Blot G., Beauvoir R., Benarous R., Berlioz-Torrent C. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14947–14952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ryo A., Tsurutani N., Ohba K., Kimura R., Komano J., Nishi M., Soeda H., Hattori S., Perrem K., Yamamoto M., Chiba J., Mimaya J., Yoshimura K., Matsushita S., Honda M., Yoshimura A., Sawasaki T., Aoki I., Morikawa Y., Yamamoto N. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 294–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nishi M., Ryo A., Tsurutani N., Ohba K., Sawasaki T., Morishita R., Perrem K., Aoki I., Morikawa Y., Yamamoto N. (2009) FEBS Lett. 583, 1243–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Radding W., Pan Z. Q., Hunter E., Johnston P., Williams J. P., McDonald J. M. (1996) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 218, 192–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chin D., Means A. R. (2000) Trends Cell Biol. 10, 322–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoeflich K. P., Ikura M. (2002) Cell 108, 739–742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ishida H., Vogel H. J. (2006) Protein Pept. Lett. 13, 455–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Osawa M., Tokumitsu H., Swindells M. B., Kurihara H., Orita M., Shibanuma T., Furuya T., Ikura M. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 819–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vetter S. W., Leclerc E. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 404–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Yamniuk A. P., Vogel H. J. (2004) Mol. Biotechnol. 27, 33–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Han Z., Harty R. N. (2007) Virus Genes 35, 511–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hayashi N., Matsubara M., Jinbo Y., Titani K., Izumi Y., Matsushima N. (2002) Protein. Sci. 11, 529–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Matsubara M., Jing T., Kawamura K., Shimojo N., Titani K., Hashimoto K., Hayashi N. (2005) Protein. Sci. 14, 494–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Srinivas S. K., Srinivas R. V., Anantharamaiah G. M., Compans R. W., Segrest J. P. (1993) J. Biol. Chem. 268, 22895–22899 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Towler D. A., Adams S. P., Eubanks S. R., Towery D. S., Jackson-Machelski E., Glaser L., Gordon J. I. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 1784–1790 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miller M. A., Mietzner T. A., Cloyd M. W., Robey W. G., Montelaro R. C. (1993) AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 9, 1057–1066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ghanam R. H., Fernandez T. F., Fledderman E. L., Saad J. S. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41911–41920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chow J. Y., Jeffries C. M., Kwan A. H., Guss J. M., Trewhella J. (2010) J. Mol. Biol. 400, 702–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Izumi Y., Watanabe H., Watanabe N., Aoyama A., Jinbo Y., Hayashi N. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 7158–7166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Massiah M. A., Starich M. R., Paschall C., Summers M. F., Christensen A. M., Sundquist W. I. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 244, 198–223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Saad J. S., Loeliger E., Luncsford P., Liriano M., Tai J., Kim A., Miller J., Joshi A., Freed E. O., Summers M. F. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 366, 574–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Putkey J. A., Slaughter G. R., Means A. R. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 4704–4712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Sorensen B. R., Shea M. A. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 4244–4253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Marley J., Lu M., Bracken C. (2001) J. Biomol. NMR 20, 71–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Malakhov M. P., Mattern M. R., Malakhova O. A., Drinker M., Weeks S. D., Butt T. R. (2004) J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 5, 75–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Johnson B. A., Blevins R. A. (1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Tang C., Loeliger E., Luncsford P., Kinde I., Beckett D., Summers M. F. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 517–522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hill C. P., Worthylake D., Bancroft D. P., Christensen A. M., Sundquist W. I. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 93, 3099–3104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. O'Neil K. T., DeGrado W. F. (1990) Trends Biochem. Sci. 15, 59–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yuan T., Ouyang H., Vogel H. J. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 8411–8420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Siivari K., Zhang M., Palmer A. G., 3rd, Vogel H. J. (1995) FEBS Lett. 366, 104–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Osawa M., Swindells M. B., Tanikawa J., Tanaka T., Mase T., Furuya T., Ikura M. (1998) J. Mol. Biol. 276, 165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Matsubara M., Nakatsu T., Kato H., Taniguchi H. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 712–718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Matsubara M., Titani K., Taniguchi H., Hayashi N. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 48898–48902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chattopadhyaya R., Meador W. E., Means A. R., Quiocho F. A. (1992) J. Mol. Biol. 228, 1177–1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fallon J. L., Quiocho F. A. (2003) Structure 11, 1303–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Finn B. E., Evenäs J., Drakenberg T., Waltho J. P., Thulin E., Forsén S. (1995) Nat. Struct. Biol. 2, 777–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Yap K. L., Kim J., Truong K., Sherman M., Yuan T., Ikura M. (2000) J. Struct. Funct. Genomics 1, 8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Vogel H. J. (1994) Biochem. Cell Biol. 72, 357–376 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Gietzen K., Sadorf I., Bader H. (1982) Biochem. J 207, 541–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bryant M., Ratner L. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87, 523–527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhou W., Parent L. J., Wills J. W., Resh M. D. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 2556–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fledderman E. L., Fujii K., Ghanam R. H., Waki K., Prevelige P. E., Freed E. O., Saad J. S. (2010) Biochemistry 49, 9551–9562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Davis M. R., Jiang J., Zhou J., Freed E. O., Aiken C. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 2405–2417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Dorfman T., Bukovsky A., Ohagen A., Höglund S., Göttlinger H. G. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 8180–8187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Freed E. O., Martin M. A. (1996) J. Virol. 70, 341–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Dorfman T., Mammano F., Haseltine W. A., Göttlinger H. G. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 1689–1696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Freed E. O., Orenstein J. M., Buckler-White A. J., Martin M. A. (1994) J. Virol. 68, 5311–5320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ono A., Freed E. O. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 4136–4144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ono A., Huang M., Freed E. O. (1997) J. Virol. 71, 4409–4418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Paillart J. C., Göttlinger H. G. (1999) J. Virol. 73, 2604–2612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.