Abstract

Background

There has been considerable interest in the elevated risk of cardiovascular disease associated with serious mental illness. While the contemporary literature has paid much attention to major depression and schizophrenia, there has been more limited focus on the risk of cardiovascular mortality for those suffering from bipolar disorder, despite some interest in the historical literature.

Methods

We reviewed the historical and contemporary literature related to cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in bipolar disorder.

Results

In studies that specifically assess cardiovascular mortality, bipolar disorder has been associated with a near doubling of risk when compared to general population estimates. This may be explained by the elevated burden of cardiovascular risk factors found in this population. These findings pre-date modern treatments, which may further influence cardiovascular risk.

Conclusions

Given the substantial risk of cardiovascular disease, rigorous assessment of cardiovascular risk is warranted for patients with bipolar disorder. Modifiable risk factors should be treated when identified. Further work is warranted to study mechanisms by which this elevated risk for cardiovascular disease are mediated and to identify systems for effective delivery of integrated medical and psychiatric care for individuals with bipolar disorder.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Cardiovascular disease, Mortality, Metabolic Syndrome, Obesity, Hypertension

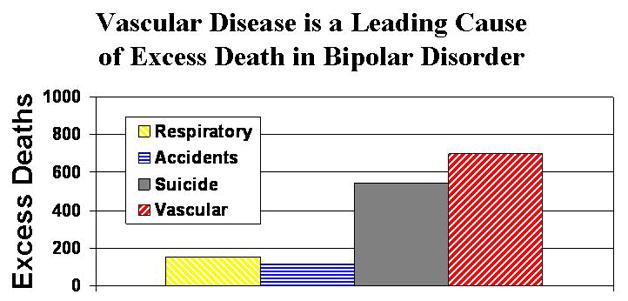

There has been considerable interest in the mortality that accompanies many psychiatric disorders. The psychiatric field has long focused on suicide, but in the past few decades, increasing attention has been given to cardiovascular mortality with psychiatric disorders. This article reviews the research related to cardiovascular disease in bipolar disorder. As illustrated in Figure 1, vascular disease is a leading cause of excess death in bipolar disorder.

Figure 1. Excess deaths in bipolar disorder.

This graph uses aggregate data from one of the largest studies of mortality in mood disorders to illustrate the primary causes of excess death with bipolar disorder (Osby et al. 2001). In their sample, a total of 2,129 excess deaths were identified in those with bipolar disorder, 700 of which were attributable to vascular disease (592 cardiovascular, 108 cerebrovascular). Thus, nearly 1/3 of the excess deaths were attributable to vascular disease alone. The top four causes of excess deaths are illustrated in this figure.

Early Studies

Toward the close of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, studies of morbidity and mortality in bipolar disorder were based almost entirely on case studies. The term bipolar disorder was not used, but the cases of mania and the construct of manic-depressive insanity were analogous to the contemporary construct of bipolar disorder (1). In an early report, Bell reported on 40 patients with mania seen at the McLean Asylum from 1836–1849, more than three-quarters of whom died. A patient suffering from Bell’s mania was said to “get so little food, so little sleep, and be exercised with such constant restlessness and anxiety, that he will fall off from day to day… At the expiration of two or three weeks, your patient will sink into death… (2) (p. 101).” Bell also compared their illnesses to delirium tremens, inflammation of the brain and meninges, and “passive congestion” of the cerebral circulation, but none of the patients demonstrated these conditions at autopsy. Bell concluded that patients experiencing similar manias were at great risk of sudden death, or were perhaps suffering from an illness distinct from any previously defined (2). Similar cases were later presented with continued debate about whether these represented sudden death in mania or a distinct condition altogether (3).

Nearly one hundred years later, Derby studied mortality in patients with manic-depression (4). Between 1912 and 1932, 980 of the patients admitted to Brooklyn State Hospital for manic-depression died during their stay. The cause of death was determined to be “exhaustion from acute mental illness” in 40%, a condition perhaps similar to what Bell had described. The next most common cause of death was cardiac disease, which accounted for an estimated 31% of deaths. In his review, Derby hypothesized that “many of these ‘exhaustion’ cases appeared … to have actually died of somatic disease” with “cardiovascular disturbance” poised as a potential etiology (4). Interestingly, like Bell, he described “the typical case of exhaustion” as characterized by dehydration, fatigue, increased pulse rate, and “some degree of temperature elevation (4).” Contemporaneously, Adlund drew from a series of case studies the belief that the illness he referred to as acute exhaustive psychoses “originates as a psychogenic problem and that the psychopathology … is expressed through dysfunctions of the cardiovascular, heat regulatory, and hematopoietic systems (5).”

These early reports consisted almost entirely of case studies, and lacked the methodological rigor of systematic observational studies. They occurred during a period lacking appropriate methods upon which to rule-out medical illnesses or draw more definitive conclusions on autopsy. Further, the symptoms that characterize “acute exhaustive psychoses” (described variously as Bell’s Mania, fatal catatonia, manic-depressive exhaustive deaths, Scheid’s cyanotic syndrome, and brain death) now suggest agitated delirium with symptoms including disorientation, confusion, visual hallucinations, and fever (3, 4). Thus, these early studies do not solidly support the connection between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular illness, though they are significant in showing that a link between the two conditions was already a topic of interest more than a century ago.

Renewed concern of an association between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular disease followed the publication of several cohort studies. Two German publications suggested that arteriosclerotic disease occurred more often, and earlier, in those with manic-depression than in the general population (6, 7). Several comprehensive studies of state hospital populations were conducted in the 1940’s and early 1950’s. Alstrom compared the death rates of psychiatric patients in the New York Civil State Hospitals to the death rates of the general population in New York. He found that the annual death rate of patients with manic depression was more than twice that of patients with schizophrenia, 7.7% vs. 3.2%, respectively. Alstrom also estimated that the risk of cardiovascular disease was twice of the general population in patients with manic-depression (8). Odegard reported on mortality from Norwegian mental hospitals over a period of approximately 15 years. There were 3,370 deaths in a sample of 21,522 first admissions, a mortality rate 5 – 6 times that of the general population. He also reported that those with manic-depression had higher mortality rates than those with schizophrenia. Men and women with schizophrenia had death rates 3.2 and 4.8 times higher than the general population, respectively, while men and women with manic-depression had mortality rates 3.8 and 6.4 times higher. For circulatory diseases these rates where 1.0 and 2.3 times higher for men and women, respectively, with schizophrenia while 3.9 and 3.5 times higher for those with other diagnoses including manic-depression. Odegard concluded that excess mortality from circulatory diseases was lower in those with schizophrenia as compared to the rest of the mentally ill population. He hypothesized that these individuals “may be protected against circulatory disturbance by their less intensive emotional reactions and their physical inactivity (9) (p. 157).” Malzberg reviewed the rates of mortality and discharge among first admissions to the New York Civil State Hospital. Although Malzberg did not focus his attention on the cause of death or diagnoses, he concluded that mortality rates were lower for individuals suffering from “dementia praecox” (schizophrenia) (10–12). These studies show that patients admitted to public mental health hospitals had a death risk 4 – 10 times that of the general population and further identified individuals with bipolar disorder as particularly at risk for cardiovascular disease.

The excess mortality identified by Malzberg, Odegard, and Alstrom was largely attributed to the conditions of public mental health facilities. More than 20 years later, Babigian and Odoroff examined mortality in all cases of psychiatric illness that were reported to the Monroe County Psychiatric Case Register between 1960 and 1966, about 6% of the population (13). This study found that “the relative risk for the registered group, when adjusted for age, sex, marital status, and socioeconomic status, is three times the general population (p. 478).” This study also found four causes of death were elevated in patients with mental illness: circulatory illness, respiratory illness, accidents, and suicide (13). While the study of Babigian and Odoroff used a representative sample, the potential for selection bias persists in the registry. A patient’s mental disease may have only been identified because medical treatment was sought for a separate physical illness, making it possible that the sampled cases included a disproportionate medical burden. This potential selection bias has been called Berkson’s bias (14). Because cases in such studies are drawn from clinical samples, Berkson’s bias unavoidably impacts research on mortality associated with mental illness (15).

Contemporary Studies

Bipolar disorder has consistently been associated with an elevated risk for cardiovascular mortality relative to the general population. Less consistent elevations in risk are seen when bipolar disorder is compared with unipolar depression. Elevations in mortality are often described with the standardized mortality ratio (SMR). The SMR represents the ratio of observed to expected deaths.

In a seminal “Iowa 500” study that included 100 patients with mania, Tsuang et al. found an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality in women (SMR = 1.63), but not men (16). A larger study in Denmark reported a similar estimate for cardiovascular mortality in patients with bipolar disorder when compared to the general population (SMR = 1.60) (17). In a sub-sample including patients with bipolar and unipolar disorders, those with bipolar disorder were found to have a significantly increased incidence of cardiovascular mortality compared with unipolar disorder (18).

A British study also showed a dramatic difference between the expected and observed deaths from cardiovascular disease in patients with bipolar disorder. During the period of study, 57 of 472 patients identified using the Edinburgh Psychiatric Case Register died; 42.1% of deaths were from cardiovascular illness, whereas a mortality of 14% was expected (19).

A Swiss study followed 406 patients with bipolar (N = 220) and unipolar (N = 186) disorder hospitalized between 1959 and 1963 and followed for up to 38 years at which point 76% of the patients had died. The patients with bipolar disorder were more likely to have died from cardiovascular disease than those with unipolar depression (a SMR of 1.84 for those with bipolar depression compared to 1.36 for patients with unipolar depression). Additionally, patients with bipolar I disorder had higher rates of death from cardiovascular disease than those with bipolar II disorder (20). No subsequent study has compared cardiovascular mortality by bipolar subtype.

A cohort study of over 5.5 million Danes followed from either their fifteenth birthday or the beginning of 1973 through the beginning of 2001 found that of the 11,648 who were admitted for the first time due to bipolar disorder, 3,669 had died by the end of the study period. The SMR for cardiovascular disease was 1.59 for men and 1.47 for women (21). This study strongly supported prior evidence of an elevated risk of cardiovascular morbidity for those suffering from bipolar disorder. A similar study in Sweden found a cardiovascular SMR for those with bipolar disorder of 1.9 for men and 2.6 for women, compared with a cardiovascular SMR for individuals with unipolar depression of 1.5 for men and 1.7 for women (22).

In 1966, Perris and d’Elia investigated mortality in a Swedish sample of 797 patients with “depressive psychoses” admitted between 1950 and 1963, 120 of whom suffered from bipolar disorder. They reported that individuals with bipolar disorder had higher mortality than those with unipolar depression, independent of suicide (23). Sims and Prior estimated mortality in 1,482 inpatients treated for severe neurosis in Birmingham hospitals between 1959 and 1968 and found excess mortality in diseases of the nervous, respiratory, and circulatory systems (SMR 1.6) though the sample was not restricted to individuals with bipolar disorder (24).

The studies detailed above reporting cardiovascular SMRs for samples with bipolar disorder are summarized in Table 1. Studies published in the past quarter century wherein estimates of cardiovascular mortality for samples of individuals exclusively with bipolar disorder could be extracted have been included. Several studies were not included because they presented composite data from mixed diagnostic samples (25–28), did not specifically assess cardiovascular mortality (25, 28–30), or did not express mortality relative to the general population (30).

Table 1. Published estimates on the SMR for cardiovascular disease in bipolar disorder.

The above table summarizes studies presenting data to estimate cause-specific cardiovascular mortality in bipolar disorder. The available estimates come from inpatient samples and suggest approximately a doubling of risk. The observed and expected deaths reflect composite data. Gender-specific estimates were available in only some studies. Observed deaths were provided on request for the Laursen et al. study. Studies presenting a SMR for cardiovascular death in bipolar disorder and published in the past 25 years were selected for inclusion.

| Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMR) for Cardiovascular Deaths in Bipolar Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study Year | Sample | Observed Expected | SMR | |

| Female | Male | |||

| Weeke et al. (17) 1987 | Inpatients, Denmark, male, index admission 1950–1956 (N=1133) or 1969– 1976 (N=2662) | 205 128.5 |

N/A | 1.60 |

| Sharma and Markar (19) 1994 | Inpatients, Scotland, index admission 1970–1975 (N=472) | 24 8 |

3.00 | |

| Osby et al. (22) 2001 | Inpatients, Sweden, index admission 1973–1995 (N=15,386) | 1073 481.5 |

1.94 | 2.65 |

| Angst et al. (20) 2002 | Inpatients, Switzerland, index admission 1959–1963 (N=220) | 59 31.5 |

1.84 | |

| Laursen et al. (21) 2007 | Inpatients, Denmark, alive on or born after 1973 (N=11,648) | 818 502.4 |

1.67 | 1.58 |

| Composite | 2179 1151.9 |

1.89 | ||

Of studies from diagnostically mixed samples or those focusing on natural deaths (inclusive of cardiovascular mortality), some have failed to demonstrate elevated mortality. An Iowa study of mortality in patients hospitalized between 1972 and 1981, Black et al. found no excess of natural death in patients with mood disorders (SMR = 0.9) (31). Similarly, Meloni et al. did not find excess natural deaths in 179 inpatients with affective psychosis from an Italian sample in 1987, though the entire sample of 845 psychiatric inpatients had a significantly elevated SMR for circulatory disease of 2.5 (32). Rorsman also found no excess in natural deaths for those with affective disorders treated at an outpatient clinic in Sweden in 1962 (33). Individuals with bipolar disorder were not examined separately from other patients with affective disorders in these studies. A study by Martin et al. separated diagnostic groups for analysis but did not find any increase in natural deaths among 19 outpatients with bipolar disorder (34). While the assessment of natural mortality in bipolar disorder by Martin et al. was limited by its small sample, the presence of these negative studies, notably the outpatient sample of Rorsman, supports some suspicion for Berkson’s bias.

Several issues influence the results of mortality studies in psychiatry. Choice of study population may be particularly relevant given the concern for Berkson’s bias. To facilitate case selection, studies to date have mainly involved clinical samples. The potential impact of selection bias on these samples must consider illness acuity (for instance, inpatient or outpatient), the nature of the cohort design (retrospective or prospective), and consideration of secular trends. Additional considerations include determination of death, psychiatric assessment, and statistical inference (35). Limitations in statistical power may be particularly evident when estimating a cause-specific mortality for a specific psychiatric diagnosis, such as highlighted in this review of cardiovascular mortality in bipolar disorder. When considering the aggregate data, mindful of these limitations, an association between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular mortality is likely, particularly after weighting the larger, contemporary studies of Osby and Laursen (21, 22).

Despite data supporting an association between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular morbidity, many questions remain. Whether bipolar disorder leads to increased risk of cardiovascular disease or whether cardiovascular disease elevates the likelihood that a person will suffer from bipolar disorder remains unanswered. Whether there is a temporal association between affective disorder and cardiovascular comorbidity is also unknown, as is the nature of that association. Most relevant studies included subjects who had been admitted to hospitals because of their mental illness, leading to ascertainment bias and potentially over-estimating risk of cardiovascular mortality. Lastly, the question remains of whether excess mortality is related to an unidentified, inherent feature of mental illness or mediated through traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

There are several possible explanations for the excess cardiovascular mortality observed with bipolar disorder. Even though the associations between bipolar disorder and cardiovascular mortality predate modern pharmacological treatments, medication could conceivably contribute to cardiovascular risk. Lithium can cause weight gain (36, 37) and adversely influence glucose metabolism (38). Valproic acid has been even more strongly associated with both weight gain and insulin resistance (39, 40). Second generation antipsychotics are associated with hyperlipidemia (41–45), insulin resistance or increased risk of diabetes mellitus (42, 46–51), and weight gain (42, 52–54). Beyond iatrogenic effects, individuals with bipolar disorder may have poor diets and receive inadequate exercise (55). Smoking is more common in those with bipolar disorder, even when compared to other serious mental illnesses (56).

Several cardiovascular risk factors are more common in individuals with bipolar disorder than in the general population, which may help to explain the elevated risk of cardiovascular mortality. These risk factors include: obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. Each could contribute to excess cardiovascular mortality.

Obesity has been associated with bipolar disorder. A study of 644 patients with bipolar disorder from private, academic, and community mental health clinics found that 79% were overweight or obese in contrast to 60% of the general population (57). Another study found that 45% of patients with bipolar disorder were obese while another 29% were overweight (58). In a case-control study, participants with bipolar disorder weighed more, had a greater body mass index, and had higher fat content than controls; but interestingly the premorbid weights of the participants with bipolar disorder were not significantly different than those of controls, leading the authors to conclude that weight gain is caused by the illness or its treatment (59). A Norweigan study of 110 patients with bipolar disorder also found more obesity among the patients than in the general population (24.9% vs. 14.1%, respectively). The differences were more pronounced when central obesity was measured (defined as a waist circumference of >102 cm in men or >88 cm in women). In the general population, only 16% met criteria for central obesity compared with 39.9% of individuals with schizophrenia and 54.2% with bipolar disorder (60). In a recent study at the University of Iowa, evaluation of available weight and height information of 161 patients with bipolar disorder found that over 75% of patients were overweight, and nearly 50% of these patients met criteria for obesity (61).

Hypertension has been less consistently linked with bipolar disorder. Although two studies indicate that hypertension was not more common among those with bipolar disorder (58, 62), other studies suggest otherwise. An Iowa study showed an increased prevalence of hypertension in those with bipolar disorder but not among those with unipolar mood disorders (63). While the prevalence of hypertension among the control population was 5.6%, the prevalence of hypertension in patients with bipolar disorder was 14% and 5% in patients with unipolar depression (63). In the Yates and Wallace study, hypertension was identified by a diagnosis of hypertension, treatment with an antihypertensive, or systolic or diastolic blood pressure greater than 160/95 mm Hg. A Norwegian study estimated a prevalence of hypertension of 61% in those with bipolar disorder as compared with a prevalence of 41% in the general population (60). This study used a much lower threshold with a systolic or diastolic pressure greater than or equal to 130/85 mm Hg. The largest study (involving 25,339 people with bipolar disorder and a control population of 113,698) showed an increased rate of new-onset hypertension among those with bipolar disorder compared with both the control population and individuals with schizophrenia. The incident rate ratio in this study was 1.3, indicating that those with bipolar disorder were significantly more likely to be newly diagnosed with hypertension than individuals in the general population (64). The assessment of incidence rather than prevalence may lessen some of the bias inherent to the study of medical comorbidity in psychiatric populations. With its size and rigorous assessment of incident cases, the study by Johannessen et al. strongly supports a link between bipolar disorder and hypertension.

The association between bipolar disorder and diabetes was first suggested since nearly a century ago (65, 66). Clinical studies have supported a greater prevalence of diabetes with bipolar disorder. Another study found that among inpatients, 9.9% of patients with bipolar disorder suffered from diabetes, three times that expected from the general population (3.3%) (67). A study of 4,210 veterans with an average age of 53 also showed a significantly greater prevalence of diabetes among patients with bipolar disorder (17.2% versus 15.6%) (62). Finally, in Norway 5.5% of 113 with bipolar disorder were found to have diabetes as compared to 2.2% of the general population (60). Overall, the data support a link between bipolar disorder and diabetes.

A possible association between bipolar disorder and hyperlipidemia has also been suggested (68). Almost half of the patients with bipolar disorder in one study met metabolic syndrome criteria for hypertriglyceridemia in contrast to only 32% of the general population (58). At Iowa, of 77 patients with bipolar disorder and a recorded lipid profile, almost a third were diagnosed with hypertriglyceridemia though some potential for surveillance bias existed (61). Available evidence indicates that individuals with bipolar disorder may be at increased risk of hyperlipidemia, specifically hypertriglyceridemia.

The metabolic syndrome can be conceptualized as a composite measure of many of these cardiovascular risk factors: visceral obesity, hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL, hypertension, and insulin resistance. U.S. samples indicate that there may be an elevated risk of metabolic syndrome in those with bipolar disorder. Estimates suggest that metabolic syndrome has a prevalence of 30% – 53% in those with bipolar disorder, as compared to a national prevalence of 27% (58, 61, 69). Several foreign studies have also found evidence of an elevated risk for metabolic disorder in bipolar disorder. In Spain, 22.4% of those with bipolar disorder had the metabolic syndrome, as opposed to the national prevalence of 14.2% (70), and more than double prevalence was seen in a Belgian study (71, 72). Similar trends were found in studies from Brazil and Turkey (38.3% vs 23.7%; 32% vs 17.9%, respectively) (73, 74). Please see Table 2 for a summary of estimates of the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder.

Table 2.

Estimates of NCEP-defined Metabolic Syndrome Prevalence with Bipolar Disorder

| Study | Sample | N (Male/Female) | Prevalence (Male/Female) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cardenas et al. (69) | Outpatients from a West Los Angeles Veterans Affairs clinic | 98 (90/8) | 49% (49%/50%) |

| Fagiolini et al. (58) | Consecutive recruits from 2003–2004 for bipolar disorder center in PA | 171 (67/104) | 30% (31%/29%) |

| Fiedorowicz et al. (61) | Outpatients from a tertiary care center with primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder | 60–125 (46/79) | 36 – 55% (52–64%/27–46%) |

| Garcia-Portilla et al. (70) | Naturalistic, multicenter, cross- sectional study in Spain | 194 (95/99) | 22.4% a (19%/26%) |

| Teixeira and Rocha (73) | Consecutive sample of psychiatric inpatients | 47 (35/12) | 38.3% b (43%/25%) |

| van Winkel et al. (71) | Pre-screening for patients with bipolar disorder started on antipsychotics. | 60 (34/26) | 16.7% c (19%/15%) |

| Yumru et al. (74) | Young sample of outpatients with bipolar disorder in Turkey | 125 (78/47) | 32% d (30%/36%) |

Nearly 60% higher than expected from general Spanish population

More than 60% higher than expected from general Brazilian population (< 24%)

Double the expected prevalence in Belgium

Nearly twice as high as expected prevalence (17.9%) in Turkey

Conclusion

Individuals with bipolar disorder have a significantly greater burden of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality than expected based on general population estimates. Further, there is evidence that this risk may exceed that seen with other mental disorders. The strength and robustness of this association indicated by the evidence suggests this association cannot be dismissed. While there may be features inherent to bipolar disorder that contribute to cardiovascular risk, the preponderance of cardiovascular risk factors in this population warrants public health focus on traditional risk factors. Cardiovascular risk factors are readily identifiable with established screening approaches and risk factors can be modified. Unfortunately, patients with serious mental illness may be less likely to be monitored for (75) and appropriately treated for cardiovascular risk factors (76). Treatment for bipolar disorder may further increase cardiovascular risk and require more rigorous monitoring. Additional research is needed to enable us better understand the many potential mediators of cardiovascular risk in this at risk population.

Acknowledgments

Jess G. Fiedorowicz is supported by L30 MH075180-02, 5KL2 RR024980, the Nellie Ball Trust Research Fund, and a NARSAD Young Investigator Award. He has also received research support for participating in a colleague’s investigator-initiated study with Eli Lilly. Miriam Weiner and Lois Warren have no disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Kraepelin E. Manic-depressive Insanity and Paranoia. Bristol, England: Thoemmes Press; 2002. p. 1921. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell LV. On a form of disease resembling some advanced stages of mania and fever, but so contradistinguished from any ordinarily described combination of symptoms, as to render it probable that it may be overlooked and hitherto unrecorded malady. American Journal of Insanity. 1849;6:97–127. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray I. On undescribed forms of acute maniacal disease. American Journal of Insanity. 1853;10:95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Derby IM. Manic-depressive “exhaustion” deaths: An analysis of “exhaustion” case histories. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1933;7:436–49. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adland ML. Review, case studies, therapy, and interpretation of the acute exhuastive psychoses. Psychiatric Quarterly. 1947;21:38–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01674767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slater E. Zur Erbpathoogie des manisch-depressiven Irreseins. Die Eltern und Kinder von Manisch-Depressiven. (Hereditary pathology of manic-depressive illness. Parents and offspring of manic-depressives) Z Gesamte Neurol Psychiatr. 1938;163:1–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bumke O. Handbuch der Geisteskrankheiten. Berlin: Julius Springer Verlag; 1928. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alstrom CH. Mortality in mental hospitals. Acta Psychiatr Neurol. 1942;17:1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Odegard O. Mortality in Norwegian mental hospitals. Acta Genet. 1951;2:141–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malzberg B. Rates of discharge and rates of mortality among first admissions to the New York civil state hospitals. Ment Hyg. 1952;36:104–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malzberg B. Rates of discharge and rates of mortality among first admissions to the New York civil state hospitals. II. Ment Hyg. 1952;36:618–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malzberg BM. Rates of discharge and rates of mortality among first admissions to the New York Civil State Hospitals. III. Ment Hyg. 1953;37:619–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Babigian HM, Odoroff CL. The mortality experience of a population with psychiatric illness. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126:470–80. doi: 10.1176/ajp.126.4.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merikangas KR, Kalaydjian A. Magnitude and impact of comorbidity of mental disorders from epidemiologic surveys. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:353–8. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281c61dc5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berkson J. Limitations of the application of fourfold tables to hospital data. Biometrics Bulletin. 1946;2:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsuang MT, Woolson RF, Fleming JA. Causes of death in schizophrenia and manic-depression. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:239–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.136.3.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weeke A, Juel K, Vaeth M. Cardiovascular death and manic-depressive psychosis. J Affect Disord. 1987;13:287–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(87)90049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weeke A, Vaeth M. Excess mortality of bipolar and unipolar manic-depressive patients. J Affect Disord. 1986;11:227–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(86)90074-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharma R, Markar HR. Mortality in affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 1994;31:91–6. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Angst F, Stassen HH, Clayton PJ, Angst J. Mortality of patients with mood disorders: follow-up over 34–38 years. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:167–81. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB. Increased mortality among patients admitted with major psychiatric disorders: a register-based study comparing mortality in unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:899–907. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osby U, Brandt L, Correia N, Ekbom A, Sparen P. Excess mortality in bipolar and unipolar disorder in Sweden. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:844–50. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perris C, d’Elia G. A study of bipolar (manic-depressive) and unipolar recurrent depressive psychoses. X. Mortality, suicide and life-cycles. Acta Psychiatr Scand Supp 194. 1966;42:172–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sims A, Prior P. The pattern of mortality in severe neuroses. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133:299–305. doi: 10.1192/bjp.133.4.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kallner G, Lindelius R, Petterson U, Stockman O, Tham A. Mortality in 497 patients with affective disorders attending a lithium clinic or after having left it. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2000;33:8–13. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-7965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Wolf T, Ahrens B, Schou M, Grof E, Grof P, Lenz G, Simhandl C, Thau K, Wolf R. Mortality during initial and during later lithium treatment. A collaborative study by the International Group for the Study of Lithium-treated Patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90:295–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb01596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zilber N, Schufman N, Lerner Y. Mortality among psychiatric patients--the groups at risk. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1989;79:248–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1989.tb10254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vestergaard P, Aagaard J. Five-year mortality in lithium-treated manic-depressive patients. J Affect Disord. 1991;21:33–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(91)90016-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsai SY, Lee CH, Kuo CJ, Chen CC. A retrospective analysis of risk and protective factors for natural death in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1586–91. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Craig TJ, Ye Q, Bromet EJ. Mortality among first-admission patients with psychosis. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Black DW, Warrack G, Winokur G. The Iowa record-linkage study. III. Excess mortality among patients with ‘functional’ disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:82–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790240084009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meloni D, Miccinesi G, Bencini A, Conte M, Crocetti E, Zappa M, Ferrara M. Mortality among discharged psychiatric patients in Florence, Italy. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1474–81. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.10.1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rorsman B. Mortality among psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1974;50:354–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1974.tb08221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin RL, Cloninger CR, Guze SB, Clayton PJ. Mortality in a follow-up of 500 psychiatric outpatients. II. Cause-specific mortality. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:58–66. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1985.01790240060006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin RL. Methodological and conceptual problems in the study of mortality in psychiatry. Psychiatr Dev. 1985;3:317–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vendsborg PB, Bech P, Rafaelsen OJ. Lithium treatment and weight gain. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1976;53:139–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1976.tb00067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sachs G, Bowden C, Calabrese JR, Ketter T, Thompson T, White R, Bentley B. Effects of lamotrigine and lithium on body weight during maintenance treatment of bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:175–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hermida OG, Fontela T, Ghiglione M, Uttenthal LO. Effect of lithium on plasma glucose, insulin and glucagon in normal and streptozotocin-diabetic rats: role of glucagon in the hyperglycaemic response. Br J Pharmacol. 1994;111:861–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1994.tb14817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dinesen H, Gram L, Andersen T, Dam M. Weight gain during treatment with valproate. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;70:65–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1984.tb00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pylvanen V, Knip M, Pakarinen A, Kotila M, Turkka J, Isojarvi JI. Serum insulin and leptin levels in valproate-associated obesity. Epilepsia. 2002;43:514–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2002.31501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang TL, Chen JF. Serum lipid profiles and schizophrenia: effects of conventional or atypical antipsychotic drugs in Taiwan. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henderson DC, Cagliero E, Gray C, Nasrallah RA, Hayden DL, Schoenfeld DA, Goff DC. Clozapine, diabetes mellitus, weight gain, and lipid abnormalities: A five-year naturalistic study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:975–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spivak B, Lamschtein C, Talmon Y, Guy N, Mester R, Feinberg I, Kotler M, Weizman A. The impact of clozapine treatment on serum lipids in chronic schizophrenic patients. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1999;22:98–101. doi: 10.1097/00002826-199903000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gaulin BD, Markowitz JS, Caley CF, Nesbitt LA, Dufresne RL. Clozapine-associated elevation in serum triglycerides. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1270–2. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osser DN, Najarian DM, Dufresne RL. Olanzapine increases weight and serum triglyceride levels. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:767–70. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo JJ, Keck PE, Jr, Corey-Lisle PK, Li H, Jiang D, Jang R, L’Italien GJ. Risk of diabetes mellitus associated with atypical antipsychotic use among patients with bipolar disorder: A retrospective, population-based, case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1055–61. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lambert BL, Chou CH, Chang KY, Tafesse E, Carson W. Antipsychotic exposure and type 2 diabetes among patients with schizophrenia: a matched case-control study of California Medicaid claims. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2005;14:417–25. doi: 10.1002/pds.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ollendorf DA, Joyce AT, Rucker M. Rate of new-onset diabetes among patients treated with atypical or conventional antipsychotic medications for schizophrenia. Med Gen Med. 2004;6:5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sernyak MJ, Gulanski B, Rosenheck R. Undiagnosed hyperglycemia in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1463–7. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carlson C, Hornbuckle K, Delisle F, Kryzhanovskaya L, Breier A, Cavazzoni P. Diabetes mellitus and antipsychotic treatment in the United Kingdom. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gianfrancesco F, White R, Wang RH, Nasrallah HA. Antipsychotic-induced type 2 diabetes: evidence from a large health plan database. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23:328–35. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000085404.08426.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simpson GM. Atypical antipsychotics and the burden of disease. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:S235–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Volavka J, Czobor P, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, Cooper TB, Chakos M, Lieberman JA. Clozapine, olanzapine, risperidone, and haloperidol in the treatment of patients with chronic schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:255–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zipursky RB, Gu H, Green AI, Perkins DO, Tohen MF, McEvoy JP, Strakowski SM, Sharma T, Kahn RS, Gur RE, Tollefson GD, Lieberman JA. Course and predictors of weight gain in people with first-episode psychosis treated with olanzapine or haloperidol. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:537–43. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.6.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kilbourne AM, Rofey DL, McCarthy JF, Post EP, Welsh D, Blow FC. Nutrition and exercise behavior among patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2007;9:443–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. Jama. 2000;284:2606–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McElroy SL, Frye MA, Suppes T, Dhavale D, Keck PE, Jr, Leverich GS, Altshuler L, Denicoff KD, Nolen WA, Kupka R, Grunze H, Walden J, Post RM. Correlates of overweight and obesity in 644 patients with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:207–13. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v63n0306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fagiolini A, Frank E, Scott JA, Turkin S, Kupfer DJ. Metabolic syndrome in bipolar disorder: findings from the Bipolar Disorder Center for Pennsylvanians. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:424–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shah A, Shen N, El-Mallakh RS. Weight gain occurs after onset of bipolar illness in overweight bipolar patients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2006;18:239–41. doi: 10.1080/10401230600948423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Birkenaes AB, Opjordsmoen S, Brunborg C, Engh JA, Jonsdottir H, Ringen PA, Simonsen C, Vaskinn A, Birkeland KI, Friis S, Sundet K, Andreassen OA. The level of cardiovascular risk factors in bipolar disorder equals that of schizophrenia: a comparative study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:917–23. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fiedorowicz JG, Palagummi NM, Forman-Hoffman VL, Miller del D, Haynes WG. Elevated prevalence of obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk factors in bipolar disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20:131–7. doi: 10.1080/10401230802177722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kilbourne AM, Cornelius JR, Han X, Pincus HA, Shad M, Salloum I, Conigliaro J, Haas GL. Burden of general medical conditions among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:368–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yates WR, Wallace R. Cardiovascular risk factors in affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 1987;12:129–34. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(87)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Johannessen L, Strudsholm U, Foldager L, Munk-Jorgensen P. Increased risk of hypertension in patients with bipolar disorder and patients with anxiety compared to background population and patients with schizophrenia. J Affect Disord. 2006;95:13–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raphael T, Parsons JP. Blood sugar studies in dementia praecox and manic-depressive insanity. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1921;5:681–709. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kasanin J. The blood sugar curve in mental disease. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1926;16:414–419. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cassidy F, Ahearn E, Carroll BJ. Elevated frequency of diabetes mellitus in hospitalized manic-depressive patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1417–20. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brandrup E, Randrup A. A controlled investigation of plasma lipids in manic-depressives. Br J Psychiatry. 1967;113:987–92. doi: 10.1192/bjp.113.502.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cardenas J, Frye MA, Marusak SL, Levander EM, Chirichigno JW, Lewis S, Nakelsky S, Hwang S, Mintz J, Altshuler LL. Modal subcomponents of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garcia-Portilla MP, Saiz PA, Benabarre A, Sierra P, Perez J, Rodriguez A, Livianos L, Torres P, Bobes J. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.van Winkel R, De Hert M, Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, Wampers M, Scheen A, Peuskens J. Prevalence of diabetes and the metabolic syndrome in a sample of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:342–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.De Hert M, van Winkel R, Van Eyck D, Hanssens L, Wampers M, Scheen A, Peuskens J. Prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia over the course of the illness: a cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemol Ment Health. 2006;2:14. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Teixeira PJ, Rocha FL. The prevalence of metabolic syndrome among psychiatric inpatients in Brazil. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2007;29:330–6. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462007000400007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yumru M, Savas HA, Kurt E, Kaya MC, Selek S, Savas E, Oral ET, Atagun I. Atypical antipsychotics related metabolic syndrome in bipolar patients. J Affect Disord. 2007;98:247–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kilbourne AM, Post EP, Bauer MS, Zeber JE, Copeland LA, Good CB, Pincus HA. Therapeutic drug and cardiovascular disease risk monitoring in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2007;102:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kreyenbuhl J, Dickerson FB, Medoff DR, Brown CH, Goldberg RW, Fang L, Wohlheiter K, Mittal LP, Dixon LB. Extent and management of cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes and serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:404–10. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000221177.51089.7d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]