Abstract

Purpose

Oxidative stress of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) by reactive oxygen species, and monocytic infiltration have been implicated in age-related macular degeneration. The purpose of this study was to determine the role of superoxide anions (O2−) in mononuclear phagocyte-induced RPE apoptosis.

Methods

Mouse RPE cell cultures were established fromwild-type and heterozygous superoxide dismutase 2-knockout (Sod2+/−) mice. The intracellular reactive oxygen species, O2− and hydrogen peroxide, were measured by using dihydroethidium assay and 5-(and 6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescence diacetate, acetyl ester assay, respectively. RPE apoptosis was evaluated by Hoechst staining and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay. Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential were detected by 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide dye. Activated caspases and caspase-3 were detected in situ by FITC-VAD-fmk staining and NucView™ 488 caspase-3 substrate, respectively.

Results

Mononuclear phagocytes and interferon-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes induced the production of intracellular RPE O2−, a decrease in RPE mitochondrial membrane potential, caspase activation and apoptosis of mouse RPE cells. All theses changes were significantly enhanced in the Sod2+/− RPE cells. Activated mononuclear phagocytes induced more of these oxidative and apoptotic changes in RPE cells compared to unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes.

Conclusions

We have shown that the decreased expression of SOD2 and increased superoxide production correlate with RPE apoptosis induced by unstimulated and activated mononuclear phagocytes. We suggest that elevated O2−levels due to genetic abnormalities of SOD2 or immunologic activation of mononuclear phagocytes lead to greater levels of RPE apoptosis. The current study could serve as a useful model to characterize RPE/phagocyte interaction in AMD and other retinal diseases.

Keywords: apoptosis, mononuclear phagocyte, RPE, ROS, O2−, SOD2

INTRODUCTION

Oxidative stress from reactive oxygen species (ROS) is considered to be one of the major factors involved in the apoptotic retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) death that underlies age-related macular degeneration (AMD).1-3 In addition, low-grade inflammation is recognized to play a role in the pathogenesis of AMD.4-13 The inflammatory response in AMD lesions is characterized by an infiltration of the blood-retina barrier including the RPE layer by leukocytes, mainly mononuclear phagocytes and lymphocytes.8,12,14-16 The RPE, that forms the outer blood-retina barrier, separates the neural retina from its choroidal blood supply, and maintains a physiologic environment for photoreceptor function. The RPE is considered a primary target in the development of AMD.2,10,17-24 Although breakdown of the RPE barrier and monocytic infiltration are hallmarks of AMD, RPE-mononuclear phagocyte interactions remain poorly understood.

Activated mononuclear phagocytes have the capacity to direct apoptosis of various kinds of cells.25-33 Although oxidative stress from ROS has been studied in RPE cells in vitro, and oxidative damage has been associated with AMD, little is known about the mechanisms for the development of the disease. We previously exposed cultured human RPE cells to a natural stimulus – monocyte binding, and found that direct interactions between cultured human RPE cells and interferon-γ (IFN-γ)-activated monocytes promote RPE cell apoptosis and induce ROS within human RPE cells.33 However, the apoptotic mechanisms by which mononuclear phagocytes influence RPE cell death have not been described.

The major endogenous source of ROS is mitochondria.2,34,35 Under normal aerobic conditions, between 0.4% and 4% of molecular oxygen is converted into superoxide anions (O2−).36 Superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) is localized in the mitochondrial matrix and catalyzes the conversion of O2− and water to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), which is the first step in metabolic defense against cellular oxidative stress.37 Several studies showed that the deficiency of SOD2 has been implicated in apoptotic cell death.20,38-46 The homozygous superoxide dismutase 2-knockout mutants survive only for 3 to 18 days.20,42,43 In heterozygous superoxide dismutase 2-knockout (Sod2+/−) mice, SOD2 protein expression in RPE cells was roughly half of the wild-type (WT) levels and SOD2 activity was 60% lower than that of WT controls.20,38 This Sod2+/− model is comparable to decreased antioxidant status during aging and may provide insight into the mechanisms of AMD. Indeed, previous studies showed that the RPE cells derived from Sod2+/− mice were more susceptible to H2O2-induced cell death compared with WT controls.20,38

To our knowledge, the role of SOD2 in the regulation of RPE apoptosis induced by mononuclear phagocytes has not been evaluated. In this study, we investigated the protective role ofSOD2 in mononuclear phagocyte-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis by comparing RPE cells derived from WT and Sod2+/− mice.

METHODS

Materials

Poly-D-lysine coated 96-well plates and Hoechst 33342 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO). Recombinant mouse IFN-γ was purchased from PeproTech, Inc. (Rocky Hill, NJ). Five-(and 6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescence diacetate, acetyl ester (CM-H2−DCFDA), 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) and CellTracker Green CMFDA were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). Fluorescein isothyocyanate-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethylketine (FITC-VAD-fmk) was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI). NucView™ 488 Caspase-3 Assay kit was purchased from Biotium, Inc. (Hayward, CA). In Situ Cell Death Detection kit was purchased from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN). Phycoerythrin-conjugated F4/80 antibody and phycoerythrin-conjugated isotype control were purchased from eBioscience, Inc. (San Diego, CA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA).

Mice

Sod2+/− mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME; stock no. 002973, strain B6.129S7-Sod2tm1Leb) and were fed standard laboratory chow and water ad libitum. To minimize genetic variations, Sod2+/− and WT mice were initially derived from breeding two heterozygous knockout mice. Polymerase chain reaction analysis was used for genotyping the offspring, as described previously.20,45 Three-to 8-month-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories and used for preparation of bone marrow-derived mononuclear phagocytes (BMDMϕ) (see below). All animals used were maintained and treated in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

RPE Cell Culture

Mouse RPE cells were isolated from eyes obtained from 1-year-old WT and Sod2+/− mice.20 Kasahara E et al. found that mouse RPE cells from 1-year-old Sod2+/− mice were more susceptible to H2O2-induced apoptosis than controls.20 The rationale for using one-year-old Sod2+/− mice is that RPE cells isolated from these mice are susceptible to oxidative stress and also have abilities to grow in cell cultures. RPE cells isolated from mice older than one-year-old Sod2+/− are too fragile and hard to survive in cell cultures because of cumulative oxidative injury. Purity of the cells was verified by immunostaining with antibodyto RPE65, a specific marker for RPE, and the SOD2 level was determined by Western blot analysis.20 These cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified essential medium (DMEM)/F12 with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C in a 5% CO2− environment. RPE cells isolated from at least 3 pairs of WT and Sod2+/− mice were used for each experiment. RPE cells at passages 2-6 were plated on 96-well plates at a density of 5 × 103 cells/well, 8-well chamber slides at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well, and 22 × 22 mm glass coverslips in 35 mm culture dishes at a density of 2.5 × 104 cells/coverslip. The RPE cells were grown in phenol red-free DMEM/F12 with 15% fetal bovine serum to 70 – 90% confluence until use.

Preparation of BMDMϕ

Bone marrow was isolated from femurs and tibias of C57BL/6 mice. After bone marrow was collected, the tissue was suspended, passed through 70 micron cell strainer. BMDMϕ were matured for 7 days at 37°C in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium with 10% FBS, 10% horse serum and 20% L-conditioned medium derived from the cell line L929 as described.26,27 Matured BMDMϕ were verified by immunostaining with antibodyto F4/80, a specific marker for Mϕ.

RPE coculture with BMDMϕ

RPE cells were prelabeled with CellTracker Green CMFDA33 and BMDMϕ were added to cultured RPE cells in a 2 BMDMϕ:1 RPE ratio. Experiments were conducted in Hanks’ balanced salt solutions (HBSS)/N-(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N’-(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (HEPES) or DMEM/F12 medium. When desired, BMDMϕ were primed for 12 h with IFN-γ (100 U/ml) before coculture with RPE in presence of IFN-γ (100 U/ml). Unstimulated BMDMϕ were exposed to control medium only. Cocultures were used for experiments involving apoptosis, ROS production, activated caspases and mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm).

Intracellular ROS Measurements

RPE cells were seeded into 96-well plates precoated with poly-D-lysine. RPE cells were washed with HBSS/HEPES, containing Ca2+ and Mg2+, but without phenol red. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with 5 μM CM-H2DCFDA (for H2O2 measurements) for 1 hr or dihydroethidium (for O2− measurements) for 20 min at 37 °C in the dark.47-49 RPE cells were then washed, and exposed to different treatments. Fluorescence intensity was measured with the FlexStation Scanning Fluorometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For H2O2 measurements, excitation and emission wavelengths were set to 495 nm and 528 nm, respectively; and for O2− measurements, excitation and emission wavelengths were set to 518 nm and 605 nm, respectively.

Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurement

JC-1 dye was used to monitor Δψm as previously described.50 In the undamaged mitochondria, the aggregated dye appears as red fluorescence, whereas in the apoptotic cell with altered Δψm, the dye remains as monomers in the cytoplasm with diffuse green fluorescence. The red/green fluorescence ratio is dependent on Δψm. RPE cells were loaded with JC-1 for 1 hr, washed, and exposed to different treatments. Fluorescence intensity was measured with a FlexStation Scanning Fluorometer. For green fluorescence measurements, excitation and emission wavelengths were set to 485 nm and 530 nm, respectively; for red fluorescence measurements, excitation and emission wavelengths were set to 520 nm and 610 nm, respectively.

Hoechst Fluorescent Staining in Living Cells

After challenge, cells were washed with HBSS/HEPES and then stained with the membrane-permeable and nuclear-specific fluorescent dye Hoechst 33342 (5 μg/mL in HBSS/HEPES) for 10 min in the dark at room temperature. After two HBSS/HEPES washes (1 min each), the coverslips were mounted on microscope slides with HBSS/HEPES and immediately viewed in an epifluorescence microscope (model E800; Nikon, Melville, NY) using an ultraviolet filter set. Digital images were collected with a cooled, CCD camera and the allied software (ACT: Nikon). The stained RPE cells that exhibited nuclear condensation and fragmentation were scored as apoptotic.

In Situ Staining of Activated Caspases in Living Cells

After treatments, cells were stained for 1 hr with FITC-VAD-fmk, according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and then washed to remove unbound dye. Images were viewed and collected as described above with a FITC filter set.

Staining of Active Caspase-3 in Living Cells

Activated caspase-3 was measured by NucView™ 488 caspase-3 substrate, a cell membrane-permeable dye consisting of a fluorogenic DNA dye and a DEVD substrate moiety specific for caspase-3 following procedures outlined in the manufacturer’s instructions. The fluorescence intensity of activated caspase-3 was measured by ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

TUNEL Staining

After treatments, cells were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline and subjected to terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) staining using the In Situ Cell Death Detection kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Apoptotic RPE cells were identified and counted.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means ± standard error and evaluated by Student’s unpaired t test or one-way analysis of variance followed by a Newman-Keul’s post hoc test. P < 0.05 is considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

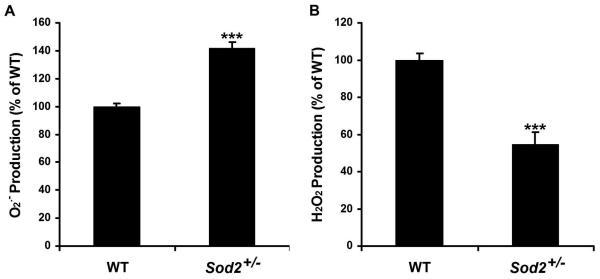

1. Levels of O2− and H2O2 in RPE Cells

RPE cells from Sod2+/− mice have reduced SOD2 protein levels and enzymatic activity.20,38 To test the consequences of reduced SOD2 protein levels and activity in ambient ROS levels, we measured the intracellular ROS, O2− and H2O2, by using dihydroethidium assay and CM-H2DCFDA assay, respectively. In Sod2+/− mice, the level of O2− was 143% of that in WT mice, while the level of H2O2 was 55% of that in WT mice (Fig. 1). Consistent with lower expression of SOD2 protein and lower SOD2 activity, the level of O2− in the Sod2+/− RPE cells was significantly higher than that in the WT RPE cells (P < 0.0001). In Sod2+/− RPE cells, the significant increase in O2− production and decrease in H2O2 production (P < 0.0001) are likely to be related to the decreased catalytic activity mediating 2O2− + 2H+ → H2O2 + O2.

Figure 1. Levels of intracellular O2− and H2O2 in mouse RPE cells.

Mouse WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells were assayed for intracellular ROS, O2− (A), and H2O2 (B), by using dihydroethidium assay and 5-(and 6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescence diacetate, acetyl ester assay, respectively. ***P < 0.0001, compared with WT.

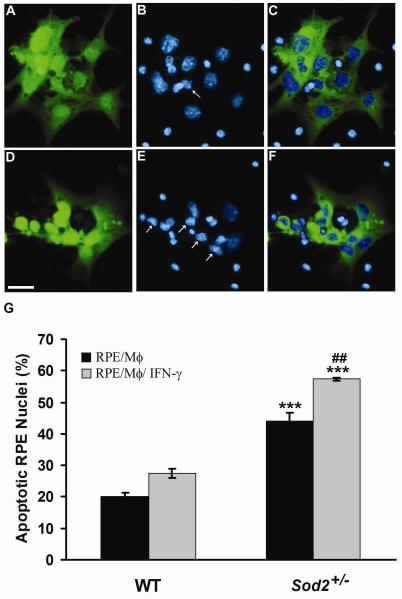

2. Mononuclear Phagocyte-Induced Apoptosis Increased in RPE Cells Derived from Sod2+/− Mice

To investigate whether mononuclear phagocytes could induce mouse RPE apoptosis, WT RPE cells were exposed to mononuclear phagocytes or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes, then evaluated using both Hoechst staining and TUNEL analysis of DNA fragmentation. Figure 2 shows mouse WT RPE cells co-cultured with unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 2, A-C) or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 2, D-F) for 24 h. WT RPE cells, prelabeled with CellTracker Green CMFDA (Fig. 2, A, D), are distinguished from mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 2C) or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 2F). Using Hoechst 33342 staining, apoptotic nuclei, a morphological marker of cell death, were observed under a fluorescent microscope. WT RPE cells stimulated with mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 2, A-C) or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 2, D-F) exhibited condensed nuclei (Fig. 2B, E; arrows). The number of Sod2+/− RPE cells with nuclear condensation was approximately twice that of WT RPE cells. (Fig. 2G) (P < 0.001).

Figure 2. Mononuclear phagocytes induce RPE apoptosis.

Hoechst 33342 staining of WT RPE co-cultured with unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (A-C) or with IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (D-F). WT RPE cells were prelabeled with CellTracker Green CMFDA (A, D). (C) Merged image of prelabeled WT RPE cells (A, green), and nuclei (B, blue) of WT RPE and unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes; (F) Merged image of prelabeled WT RPE cells (D, green), and nuclei (E, blue) of WT RPE and IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. WT RPE cells are distinguished from mononuclear phagocytes by merged images (C, F). Arrows in panels B and E indicate condensed WT RPE nuclei. Scale bar, 25 μm. (G) shows percentage of apoptotic nuclei of WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (RPE/Mϕ) or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (RPE/Mϕ/ IFN-γ). *** P < 0.001, compared with WT; ##P < 0.01, compared with RPE/Mϕ.

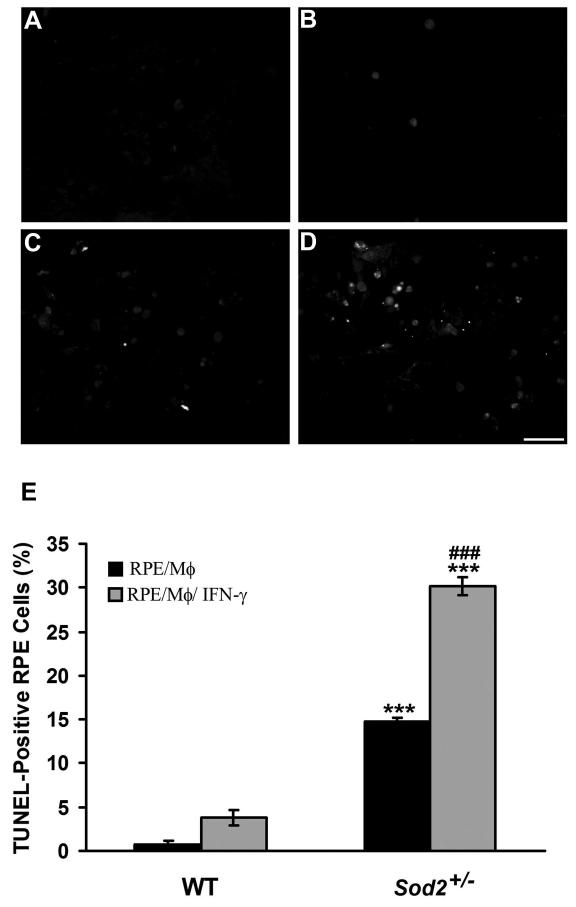

RPE apoptosis induced by mononuclear phagocytes or activated mononuclear phagocytes was confirmed by TUNEL staining (Fig. 3). In WT mice, RPE cells exposed to mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 3A) and IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 3B) showed 0.8% and 3.8% TUNEL-positive cells (Fig. 3E), respectively. However, in Sod2+/− mice, significantly higher numbers of TUNEL-positive cells were observed after mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 3C) or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 3D) were co-cultured with RPE cells to induce apoptosis (14.8% vs. 30.2%) (Fig. 3E) (both P < 0.001). Furthermore, co-cultures of RPE with IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes caused a significant increase in TUNEL-positive RPE cells compared to RPE cells co-cultured with unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 3E) (P < 0.001).

Figure 3. Decreased expression of SOD2 increases mononuclear phagocyte-induced RPE apoptosis.

TUNEL staining of WT (A, B) or Sod2+/− (C, D) RPE cells co-cultured with unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (A, C) or with IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (B, D). Scale bar, 50 μm. (E) shows percentage of TUNEL-positive WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (RPE/Mϕ) or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (RPE/Mϕ/ IFN-γ). *** P < 0.001, compared with WT; ###P < 0.001, compared with RPE/Mϕ.

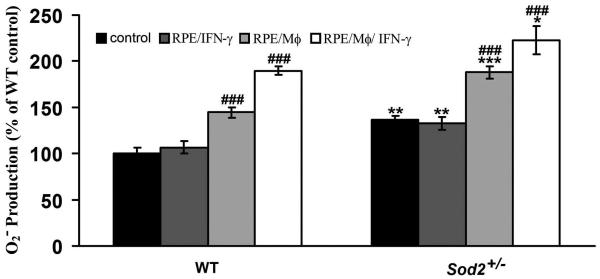

3. Mononuclear Phagocyte-Induced O2− Production Increased in RPE Cells Derived from Sod2+/− Mice

Elevated intracellular ROS may play an important role in triggering cell death.51-53 Therefore, we investigated production of O2− in RPE cells exposed to mononuclear phagocytes or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes by using dihydroethidium assay. We first tested effects of different durations (1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16 or 24 hr) on the O2− production in WT RPE cells treated by unstimulated and IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. We found that the O2− production in the RPE cells significantly increased when RPE cells were treated with unstimulated or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes at 1, 2, 3, 4, 8, 16 or 24 hr, compared to control RPE cells. However, there were no further statistically significant increases in the intracellular O2− production in RPE cells treated with unstimulated or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes at 2, 3, 4, 8, 16 or 24 hr, compared to the same treatment at 1 hr. Therefore, we chose 1 hr time point to measure O2− production in WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells treated with unstimulated or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. As shown in Figure 4, mononuclear phagocytes and IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes significantly increased O2− production in WT RPE cells to 144.5% and 189.7%, respectively (both P < 0.001), in comparison to controls. Mononuclear phagocytes and IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes also significantly increased O2− production in Sod2+/− RPE cells to 187.9% and 222.8%, respectively (both P < 0.001). Basal O2− levels were significantly higher in RPE cells from Sod2+/− mice than those from WT mice (Fig. 1). In both WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells, the increase in the extent of O2− production was significantly higher in RPE cells exposed to IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes than those exposed to unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes. IFN-γ alone did not significantly increase O2− production by the RPE cells from both WT and Sod2+/− mice (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Decreased expression of SOD2 increases mononuclear phagocyte-induced O2− production.

The production of O2− in WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to control medium (control), IFN-γ (RPE/IFN-γ), unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (RPE/Mϕ), or IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (RPE/Mϕ/IFN-γ). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, compared with WT; ###P < 0.001, compared with its own control.

4. Mononuclear Phagocyte-Induced Loss of Δψm Enhanced in RPE Cells Derived from Sod2+/− Mice

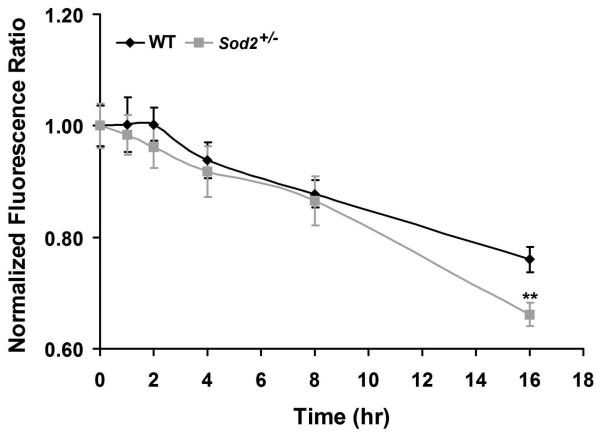

Changes in Δψm are often associated with an early stage of apoptosis.20,54-56 To establish whether O2− production induced by IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes is coincident with changes in Δψm during apoptosis, Δψm was measured with the JC-1 probe. The ratio of red-to-green JC-1 fluorescence is dependent on the Δψm.50 As shown in Fig. 5, the ratio of red-to-green JC-1 fluorescence was plotted versus time in WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. For WT RPE cells, the fluorescence ratio started to decline after a 4 hr exposure to IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. However, in Sod2+/− RPE cells, the decline was first noted after 2 hr of incubation with IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes, although not statistically significant. The ratios measured at 16 hr for Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (0.62 ± 0.02) were significantly lower than those (0.76 ± 0.02) measured for WT RPE cells exposed to IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes (P < 0.01). Thus, SOD2 deficiency results in a greater loss of the Δψm in the presence of activated mononuclear phagocytes. The decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential are not significantly different until 16 hr between WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells, suggesting that both mitochondria-dependent and mitochondria-independent pathways may be operating in RPE apoptosis induced by mononuclear phagocytes.

Figure 5. Decreased expression of SOD2 enhances mononuclear phagocyte-induced loss of Δψm.

Measurement of the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψm) in WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. Δψm was measured by using 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide probe. **P < 0.01, compared with WT.

5. Mononuclear Phagocyte-Induced Activation of Caspases Increased in RPE Cells Derived from Sod2+/− Mice

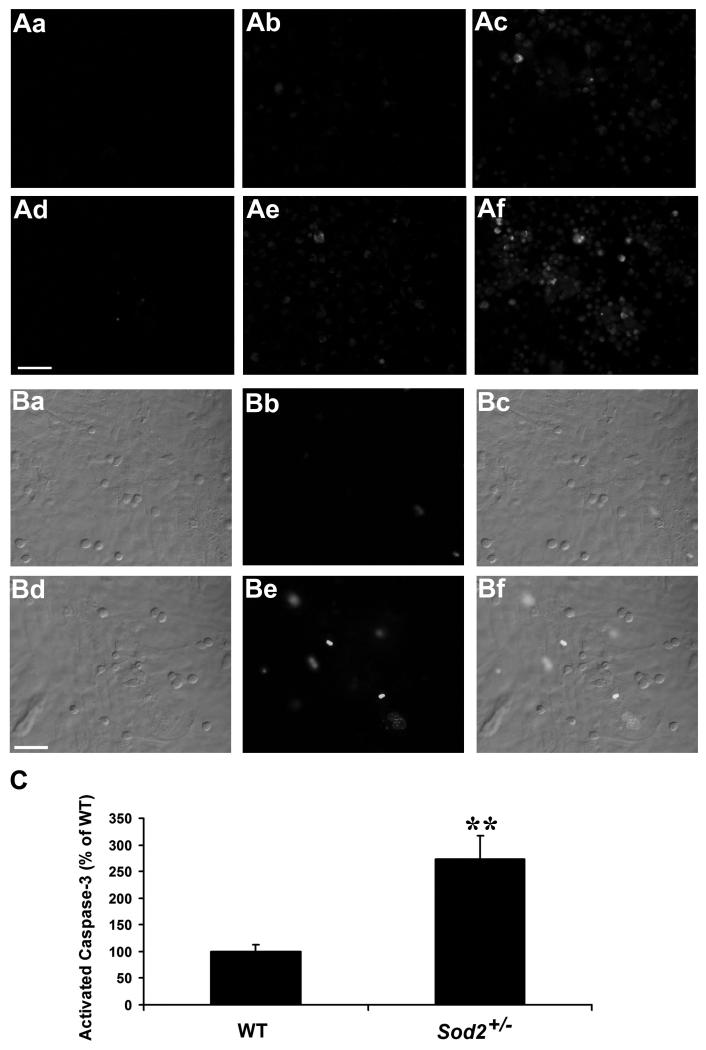

Caspase activation has been implicated in RPE apoptosis in response to various stimuli.2,33,38 Therefore, we first qualitatively examined whether caspases are activated in WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes or activated mononuclear phagocytes. As seen in Fig. 6A, there was a marked increase in activated caspases in RPE cells overlaid with unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 6 Ab, Ae) or activated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 6 Ac, Af) compared with control RPE cells (Fig. 6 Aa, Ad) from WT and Sod2+/− mice. Moreover, Sod2+/− RPE cells (Fig. 6 Ad-Af) exhibited more caspase activation than WT RPE cells (Fig. 6 Aa-Ac). These data indicate that caspases are activated during RPE apoptosis that is induced by mononuclear phagocytes or activated mononuclear phagocytes and that SOD2 deficiency is associated with higher levels of caspase activation in RPE cells. Caspase activation was confirmed by a second assay, in which activated caspase-3 was measured by NucView™ 488 caspase-3 substrate, a cell membrane-permeable dye consisting of a fluorogenic DNA dye and a DEVD substrate moiety specific for caspase-3. The non-cleaved substrate, which is both non-fluorescent and nonfunctional as a DNA dye, rapidly crosses cell membrane to enter the cell cytoplasm, where it is cleaved by activated caspase-3 to release a high-affinity DNA dye that migrates into the cell nucleus and binds to DNA, staining the nucleus green. Thus, the substrate is bi-functional, being able to detect intracellular caspase-3 activity and to stain the cell nucleus at the same time. By using this assay, we detected significantly higher fluorescence intensity of activated caspase-3 in Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to activated mononuclear phagocytes (Fig. 6B, 6C) (P < 0.01).

Figure 6. Decreased expression of SOD2 increases mononuclear phagocyte-induced activation of caspases.

(A) In situ staining of activated caspases in WT (Aa-Ac) and Sod2+/− (Ad-Af) RPE cells. Fluorescence images of cells stained with FITC-VAD-fmk to localize activated caspases in RPE cells alone (Aa, Ad), RPE cells co-cultured with unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes (Ab, Ae), or RPE cells co-cultured with IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes in the presence of IFN-γ (Ac, Af). (B) Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images of activated caspase-3 in WT (Ba-Bc) and Sod2+/− (Bd-Bf) RPE cells co-cultured with IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. (Bc) Merged image of WT RPE DIC (Ba) and activated caspase-3 fluorescence (Bb); (Bf) Merged image of Sod2+/− RPE DIC (Bd) and activated caspase-3 fluorescence (Be). (C) shows a quantification analysis of activated caspase-3 fluorescence intensity in WT and Sod2+/− RPE cells exposed to IFN-γ-activated mononuclear phagocytes. **P < 0.01, compared with WT. Scale bar, 50 μm.

DISCUSSION

Mononuclear phagocyte-induced RPE apoptosis is likely to be involved in human diseases such as AMD, which is the leading cause of blindness among people over age 60 in the developed world. We used a Sod2+/− mouse model to dissect the role of ROS in RPE apoptosis induced by mononuclear phagocytes. Mononuclear phagocyte-induced RPE apoptosis was dramatically increased in RPE cells with reduced SOD2 expression. Mononuclear phagocyte-induced RPE apoptosis involved enhanced intracellular O2− generation, loss of Δψm, and caspase activation, all of which were enhanced when mononuclear phagocytes were activated with IFN-γ.

There is emerging evidence that macrophages play an active role in promoting apoptosis.57 Lang and Bishop first discovered that macrophage ablation permitted persistence of viable cells in mouse ocular vessel networks that failed to undergo normal processes of regression.30 Their seminal work has received support in a number of systems from C. elegans to human cells.25-29,33,58-64

Previously we showed that activated, but not unstimulated monocytes, isolated from human peripheral blood, induced human RPE apoptosis by using a human RPE culture model.33 By using a mouse RPE culture model, our current work shows that unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes and activated mononuclear phagocytes induce mouse RPE apoptosis that is comparable with these previous studies and supports the concept that mononuclear phagocytes may play an active role in cell death.30

Mechanisms of mononuclear phagocyte-induced cell death have been described in vitro and in vivo. In the developing chick retina, Frade and Barde demonstrated macrophage-derived nerve growth factor (NGF) triggered the retinal cell death.65 Addition of NGF-coated glass beads, but not soluble NGF caused cell death in the neural retina, suggesting that NGF may need to be presented locally or bound to the cell surface to result in cell death.65 Tumor necrosis factor-α or Fas ligand was shown to trigger the death of developing neurons, but not to trigger the death of Purkinje cells. The death of Purkinje cells was reported to be promoted by O2−.66-68 Macrophage-derived tumor necrosis factor may also play a major role in directing apoptosis of glomerular mesangial cells.59

ROS are known to induce RPE cell apoptosis and have been implicated in the development of AMD.2,69,70 Moreover, intracellular ROS generation is considered to be more important to apoptosis induction than extracellular ROS.51,52 ROS are generated by different sources. The main sources of intracellular ROS generation are the mitochondrial electron transport chain, microsomal electron transport chains, plasma membrane-bound and intracellular compartmental NAD(P)H oxidases.2,47,71,72 In RPE cells, ROS are usually reduced by endogenous RPE antioxidants and antioxidant enzymes including SOD, catalase and glutathione peroxidase.2 SOD catalyzes the dismutation of O2− to H2O2, protecting against O2−. There are three different isoforms of SOD: SOD1, SOD2 and SOD3, which are localized in the cytoplasm, mitochondria and extracellular space, respectively.73,74 H2O2 can be removed by catalase and glutathione peroxidase. However, during aging and pathological conditions, RPE defenses decrease, disturbing the balance between the generation and elimination of ROS, resulting in oxidative damage.2,75

SOD2 is an important enzyme in maintaining mitochondrial function in the presence of oxidative stress.35 Studies of partial SOD2 deficiency have shown that increased oxidative damage is correlated with altered mitochondrial function, and that chronic mitochondrial oxidative stress in Sod2+/− mice results in the age-related decline of mitochondrial function and induction of premature apoptosis in the liver.41,46 In the brain, oxidative stress may exacerbate infarction, by generating excessive O2− in the mitochondrial compartment in Sod2+/− mice.76,77 In mouse RPE cells, previous studies demonstrated the critical role of SOD2 in protecting RPE cells in vitro against H2O2-induced apoptosis.20,38 This protective effect was directly related to the cellular expression level of the enzyme.20 However, mouse RPE cells with increased SOD2 expression showed increased oxidative damage induced by activated mononuclear phagocyte (data not shown), consistent with Lu L, et al. who found that increased levels of SOD2 in transfected human RPE cells increased constitutive oxidative damage.81 Using an independent approach, Justilien et al. reported the use of ribozyme-mediated partial knockdown of SOD2 mRNA to induce oxidative damage in the RPE of WT mice, as a possible animal model of early dry AMD.78

By partial knockout of SOD2, in this study, we demonstrate that mononuclear phagocytes induced RPE apoptosis via intracellular O2− because mononuclear phagocytes induced O2− generation within 1hr of co-culture, before initiation of RPE apoptosis. Furthermore, mononuclear phagocytes induced activation of caspases, including caspase-3, loss of Δψm, and apoptosis that were all significantly enhanced in the RPE cells derived from Sod2+/− mice. Taken together, these data suggest reduced SOD2 levels are critical to these changes. These changes in the RPE cells are also dependent on the activation state of mononuclear phagocytes as activated mononuclear phagocytes induced more of these oxidative and apoptotic changes in RPE cells compared to unstimulated mononuclear phagocytes. We also noted a positive correlation between intracellular O2− levels and apoptosis in mouse RPE cells. The extent of apoptosis is related to the level of intracellular O2− production (Figs. 3&4). In the current study, we used RPE cells isolated from 1 year old mice. Decreased SOD2 in Sod2+/− mice would likely cause cumulative oxidative injury in these cells and render them more susceptible to apoptosis.41, 46 The aforementioned studies and those described in current study clearly indicate the importance of SOD2 in the RPE in protection against mitochondrial oxidative stress.

Inflammatory macrophages are a heterogeneous group of cells with diverse functions.60 They can exist in the same tissue and play critical roles in both the injury and recovery phases of inflammatory scarring.61 Co-culturing fibroblasts and myofibroblasts with macrophages results in either deposition of matrix components, or lytic degradation of matrix, depending on the activation state of the macrophage.62,79,80

The effects of aging on ocular tissues have not been explored in Sod2+/− mice and remain to be investigated. Principal risk factors for AMD are age, race, smoking, and hypertension. A key element in AMD pathogenesis is dysfunction and apoptotic loss of RPE cells. Thus, it is possible that infiltration of lymphocytes and mononuclear phagocytes may occur in the retina of Sod2+/− mice during aging, leading to RPE apoptosis, as macrophage trafficking in mouse eyes has been shown to increase with aging.4 Therefore, the current study could serve as a useful model to characterize RPE/mononuclear phagocyte interaction in AMD and other retinal diseases. This model directly links RPE apoptosis that underlies AMD with the known risk factors for AMD.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants EY09441 (V.M. Elner), EY00484 (V.N. Reddy), CA74120 (H.R. Petty) and EY07003 (core). V.M. Elner is a recipient of Senior Scientific Investigator Award from Research to Prevent Blindness.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:7915–7922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai J, Nelson KC, Wu M, et al. Oxidative damage and protection of the RPE. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2000;19:205–221. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(99)00009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liang FQ, Godley BF. Oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial DNA damage in human retinal pigment epithelial cells: a possible mechanism for RPE aging and age-related macular degeneration. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(03)00023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ambati J, Anand A, Fernandez S, et al. An animal model of age-related macular degeneration in senescent Ccl-2- or Ccr-2-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2003;9:1390–1397. doi: 10.1038/nm950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson DH, Mullins RF, Hageman GS, et al. A role for local inflammation in the formation of drusen in the aging eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:411–431. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01624-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Apte RS, Richter J, Herndon J, et al. Macrophages inhibit neovascularization in a murine model of age-related macular degeneration. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e310. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Espinosa-Heidmann DG, Suner IJ, Hernandez EP, et al. Macrophage depletion diminishes lesion size and severity in experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3586–3592. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossniklaus HE, Ling JX, Wallace TM, et al. Macrophage and retinal pigment epithelium expression of angiogenic cytokines in choroidal neovascularization. Mol Vis. 2002;8:119–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hageman GS, Luthert PJ, Victor Chong NH, et al. An integrated hypothesis that considers drusen as biomarkers of immune-mediated processes at the RPE-Bruch’s membrane interface in aging and age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:705–732. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(01)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hollyfield JG, Bonilha VL, Rayborn ME, et al. Oxidative damage-induced inflammation initiates age-related macular degeneration. Nat Med. 2008;14:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Penfold PL, Killingsworth MC, Sarks SH. Senile macular degeneration: the involvement of immunocompetent cells. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1985;223:69–76. doi: 10.1007/BF02150948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penfold PL, Madigan MC, Gillies MC, et al. Immunological and aetiological aspects of macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2001;20:385–414. doi: 10.1016/s1350-9462(00)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakurai E, Anand A, Ambati BK, et al. Macrophage depletion inhibits experimental choroidal neovascularization. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:3578–3585. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baudouin C, Peyman GA, Fredj-Reygrobellet D, et al. Immunohistological study of subretinal membranes in age-related macular degeneration. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1992;36:443–451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reddy VM, Zamora RL, Kaplan HJ. Distribution of growth factors in subfoveal neovascular membranes in age-related macular degeneration and presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 1995;120:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)72158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seregard S, Algvere PV, Berglin L. Immunohistochemical characterization of surgically removed subfoveal fibrovascular membranes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1994;232:325–329. doi: 10.1007/BF00175983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bressler SB, Maguire MG, Bressler NM, et al. The Macular Photocoagulation Study Group Relationship of drusen and abnormalities of the retinal pigment epithelium to the prognosis of neovascular macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:1442–1447. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1990.01070120090035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Jong PT. Age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1474–1485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Green WR, McDonnell PJ, Yeo JH. Pathologic features of senile macular degeneration. Ophthalmology. 1985;92:615–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasahara E, Lin LR, Ho YS, et al. SOD2 protects against oxidation-induced apoptosis in mouse retinal pigment epithelium: implications for age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3426–3434. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarks SH. Drusen and their relationship to senile macular degeneration. Aust J Ophthalmo. 1980;8:117–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1980.tb01670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spraul CW, Lang GE, Grossniklaus HE. Morphometric analysis of the choroid, Bruch’s membrane, and retinal pigment epithelium in eyes with age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2724–2735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Young RW. Pathophysiology of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 1987;31:291–306. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(87)90115-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zarbin MA. Age-related macular degeneration: review of pathogenesis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1998;8:199–206. doi: 10.1177/112067219800800401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arantes RM, Lourenssen S, Machado CR, et al. Early damage of sympathetic neurons after co-culture with macrophages: a model of neuronal injury in vitro. Neuroreport. 2000;11:177–181. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Diez-Roux GR, Lang RA. Macrophages induce apoptosis in normal cells in vivo. Development. 1997;124:3633–3638. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duffield JS, Erwig LP, Wei X, et al. Activated macrophages direct apoptosis and suppress mitosis of mesangial cells. J Immunol. 2000;164:2110–2119. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffith TS, Wiley SR, Kubin MZ, et al. Monocyte-mediated tumoricidal activity via the tumor necrosis factor-related cytokine, TRAIL. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1343–1354. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirano S. Nitric oxide-mediated cytotoxic effects of alveolar macrophages on transformed lung epithelial cells are independent of the beta 2 integrin-mediated intercellular adhesion. Immunology. 1998;93:102–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1998.00393.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang RA, Bishop JM. Macrophages are required for cell death and tissue remodeling in the developing mouse eye. Cell. 1993;74:453–462. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80047-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meszaros AJ, Reichner JS, Albina JE. Macrophage-induced neutrophil apoptosis. J Immunol. 2000;165:435–441. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakayama M, Kayagaki N, Yamaguchi N, et al. Involvement of TWEAK in interferon gamma-stimulated monocyte cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1373–1380. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoshida A, Elner SG, Bian ZM, et al. Activated monocytes induce human retinal pigment epithelial cell apoptosis through caspase-3 activation. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1117–1129. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000082393.02727.b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simonian NA, Coyle JT. Oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1996;36:83–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.36.040196.000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial disease in man and mouse. Science. 1999;283:1482–1488. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5407.1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melov S, Coskun P, Patel M, et al. Mitochondrial disease in superoxide dismutase 2 mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:846–851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ho YS, Crapo JD. Isolation and characterization of complementary DNAs encoding human manganese-containing superoxide dismutase. FEBS Lett. 1988;229:256–260. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81136-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ferrington DA, Tran TN, Lew KL, et al. Different death stimuli evoke apoptosis via multiple pathways in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hengartner MO. The biochemistry of apoptosis. Nature. 2000;407:770–776. doi: 10.1038/35037710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karbowski M, Kurono C, Wozniak M, et al. Free radical-induced megamitochondria formation and apoptosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:396–409. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kokoszka JE, Coskun P, Esposito LA, et al. Increased mitochondrial oxidative stress in the Sod2 (+/-) mouse results in the age-related decline of mitochondrial function culminating in increased apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2278–2283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051627098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lebovitz RM, Zhang H, Vogel H, et al. Neurodegeneration, myocardial injury, and perinatal death in mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9782–9787. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Huang TT, Carlson EJ, et al. Dilated cardiomyopathy and neonatal lethality in mutant mice lacking manganese superoxide dismutase. Nat Genet. 1995;11:376–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu L, Trimarchi JR, Keefe DL. Involvement of mitochondria in oxidative stress-induced cell death in mouse zygotes. Biol Reprod. 2000;62:1745–1753. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod62.6.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reddy VN, Kasahara E, Hiraoka M, et al. Effects of variation in superoxide dismutases (SOD) on oxidative stress and apoptosis in lens epithelium. Exp Eye Res. 2004;79:859–868. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams MD, Van Remmen H, Conrad CC, et al. Increased oxidative damage is correlated to altered mitochondrial function in heterozygous manganese superoxide dismutase knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:28510–28515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang D, Elner SG, Bian ZM, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines increase reactive oxygen species through mitochondria and NADPH oxidase in cultured RPE cells. Exp Eye Res. 2007;85:462–472. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pardo M, Melendez JA, Tirosh O. Manganese superoxide dismutase inactivation during Fas (CD95)-mediated apoptosis in Jurkat T cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1795–1806. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhao H, Kalivendi S, Zhang H, et al. Superoxide reacts with hydroethidine but forms a fluorescent product that is distinctly different from ethidium: potential implications in intracellular fluorescence detection of superoxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;34:1359–1368. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00142-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang JH, Le WD, Basinger SF, et al. Mechanisms of apoptosis in human retinal pigment epithelium induced by TNF-alpha in conditions of heavy metal ion deficiency. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1039–1046. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-0325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ramachandran A, Moellering D, Go YM, et al. Activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase and apoptosis in endothelial cells mediated by endogenous generation of hydrogen peroxide. Biol Chem. 2002;383:693–701. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sakaguchi N, Inoue M, Ogihara Y. Reactive oxygen species and intracellular Ca2+, common signals for apoptosis induced by gallic acid. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1973–1781. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00041-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang X, Wang X. Cytochrome C-mediated apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:87–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kroemer G, Reed JC. Mitochondrial control of cell death. Nat Med. 2000;6:513–519. doi: 10.1038/74994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, et al. Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science. 1997;275:1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rao S, Lobov IB, Vallance JE, et al. Obligatory participation of macrophages in an angiopoietin 2-mediated cell death switch. Development. 2007;134:4449–4458. doi: 10.1242/dev.012187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aliprantis AO, Diez-Roux G, Mulder LC, et al. Do macrophages kill through apoptosis? Immunol Today. 1996;17:573–576. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(96)10071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Duffield JS, Ware CF, Ryffel B, et al. Suppression by apoptotic cells defines tumor necrosis factor-mediated induction of glomerular mesangial cell apoptosis by activated macrophages. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1397–1404. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62526-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Duffield JS. The inflammatory macrophage: a story of Jekyll and Hyde. Clin Sci (Lond) 2003;104:27–38. doi: 10.1042/. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Duffield JS, Forbes SJ, Constandinou CM, et al. Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:56–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI22675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duffield JS, Tipping PG, Kipari T, et al. Conditional ablation of macrophages halts progression of crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:1207–1219. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61209-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hoeppner DJ, Hengartner MO, Schnabel R. Engulfment genes cooperate with ced-3 to promote cell death in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2001;412:202–206. doi: 10.1038/35084103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Reddien PW, Cameron S, Horvitz HR. Phagocytosis promotes programmed cell death in C. elegans. Nature. 2001;412:198–202. doi: 10.1038/35084096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frade JM, Barde YA. Microglia-derived nerve growth factor causes cell death in the developing retina. Neuron. 1998;20:35–41. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80432-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davies AM. Regulation of neuronal survival and death by extracellular signals during development. EMBO J. 2003;22:2537–2545. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marín-Teva JL, Dusart I, Colin C, et al. Microglia promote the death of developing Purkinje cells. Neuron. 2004;41:535–547. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mallat M, Marín-Teva JL, Chéret C. Phagocytosis in the developing CNS: more than clearing the corpses. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barak A, Morse LS, Goldkorn T. Ceramide: a potential mediator of apoptosis in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2001;42:247–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Beatty S, Koh H, Phil M, et al. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv Ophthalmol. 2000;45:115–134. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miceli MV, Liles MR, Newsome DA. Evaluation of oxidative processes in human pigment epithelial cells associated with retinal outer segment phagocytosis. Exp Cell Res. 1994;214:242–249. doi: 10.1006/excr.1994.1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang F, Jin S, Yi F, et al. Local production of O(2)(-) by NAD(P)H oxidase in the sarcoplasmic reticulum of coronary arterial myocytes: cADPR-mediated Ca(2+) regulation. Cell Signal. 2008;20:637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lu L, Hackett SF, Mincey A, et al. Effects of different types of oxidative stress in RPE cells. J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:119–125. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Newsome DA, Dobard EP, Liles MR, et al. Human retinal pigment epithelium contains two distinct species of superoxide dismutase. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:2508–2513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ballinger SW, Van Houten B, Jin GF, et al. Hydrogen peroxide causes significant mitochondrial DNA damage in human RPE cells. Exp Eye Res. 1999;68:765–772. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Murakami K, Kondo T, Kawase M, et al. Mitochondrial susceptibility to oxidative stress exacerbates cerebral infarction that follows permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mutant mice with manganese superoxide dismutase deficiency. J Neurosci. 1998;18:205–213. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-01-00205.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fujimura M, Morita-Fujimura Y, Kawase M, et al. Manganese superoxide dismutase mediates the early release of mitochondrial cytochrome C and subsequent DNA fragmentation after permanent focal cerebral ischemia in mice. J Neurosci. 1999;19:3414–3422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-09-03414.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Justilien V, Pang JJ, Renganathan K, et al. SOD2 knockdown mouse model of early AMD. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:4407–4420. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kitamura M. TGF-beta1 as an endogenous defender against macrophage-triggered stromelysin gene expression in the glomerulus. J Immunol. 1998;160:5163–5168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Song E, Ouyang N, Horbelt M, et al. Influence of alternatively and classically activated macrophages on fibrogenic activities of human fibroblasts. Cell Immunol. 2000;204:19–28. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lu L, Oveson BC, Jo YJ, et al. Increased Expression of Glutathione Peroxidase 4 Strongly Protects Retina from Oxidative Damage. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008 doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2171. doi:10.1089/ARS, 2008,2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]