Abstract

Here, we report that the natural compound pentachloropseudilin (PClP) acts as a reversible and allosteric inhibitor of myosin ATPase and motor activity. IC50 values are in the range from 1 to 5 μm for mammalian class-1 myosins and greater than 90 μm for class-2 and class-5 myosins, and no inhibition was observed with class-6 and class-7 myosins. We show that in mammalian cells, PClP selectively inhibits myosin-1c function. To elucidate the structural basis for PClP-induced allosteric coupling and isoform-specific differences in the inhibitory potency of the compound, we used a multifaceted approach combining direct functional, crystallographic, and in silico modeling studies. Our results indicate that allosteric inhibition by PClP is mediated by the combined effects of global changes in protein dynamics and direct communication between the catalytic and allosteric sites via a cascade of small conformational changes along a conserved communication pathway.

Keywords: Actin, Allosteric Regulation, ATPases, Enzyme Inhibitors, Myosin, X-ray Crystallography, Energetic Coupling, Pseudilin

Introduction

Myosins are a large superfamily of molecular motors that move along actin filaments in an ATP-dependent manner. The versatile and indispensable role of myosins as mediators of a wide range of transport and chemo-mechanical signal transduction events is generally accepted. Due to their rapid, conditional, and reversible mode of action, small molecule modulators of protein function are useful tools in cell biological research and can serve as lead compounds in the development of therapeutic agents (1, 2). The use of small molecule effectors of myosin function such as N-benzyl-p-toluenesulfonamide and blebbistatin helped to provide important new insights in a range of cellular functions that require the active participation of at least one member of the myosin family. Compounds such as blebbistatin and N-benzyl-p-toluenesulfonamide display preferred interactions with selected members of myosin class-2 (3, 4). However, there exists a requirement to develop specific inhibitors for other classes of myosins.

Recently, we described the total synthesis of halogenated pseudilins, natural products containing a 2-arylpyrrole moiety, and their synthetic analogues (5). Pentabromopseudilin (PBP)2 was identified as a potent inhibitor of vertebrate myosin-5 motor activity. An IC50 of 400 nm was determined for the PBP-mediated inhibition of the ATPase activity of vertebrate myosin-5 (6). Based on this finding, we screened related compounds to identify myosin effectors with altered selectivity for the members of different myosin classes (7). Pentachloropseudilin (PClP), a close chemical and structural analog of PBP, was identified as a potent inhibitor of class-1 myosins.

Here, we describe the effects of PClP on actomyosin kinetics, myosin motor function, and cellular morphology. Co-crystallization trials with class-1 myosins in the presence of PClP failed. Because most of the class-1 myosin motor domains have 50–60% sequence similarity with class-2 myosin motor domains, we used Dictyostelium discoideum myosin-2 as a model system to interpret the binding site of PClP in other myosin isoforms. The resulting structure shows that the inhibitor binds in the same allosteric pocket as PBP, but the conformation of the inhibitor and details of its interaction with myosin are different. Molecular modeling and docking studies based on the x-ray crystallographic results were used to explain the preferred binding of PClP to class-1 myosins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Preparation

We purified His-tagged motor domain constructs of myosin-1E, myosin-1B, myosin-2, and myosin-5b from D. discoideum comprising amino acids 1–698, 1–698, 1–761, and 1–829, respectively, by Ni2+ chelate affinity chromatography (8, 9). FLAG-tagged truncated Rattus norvegicus myosin-1b and myosin-1c consisting of the motor domain and first IQ domain were prepared as described previously (10, 11). Amino acids 1–816 of human myosin-6 and 1–747 of human myosin-7a were fused to an artificial lever arm and in the case of myosin-7a additionally to an enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) fluorescence marker. His-tagged proteins were overproduced in the baculovirus/Sf9 system and purified by Ni2+ chelate affinity chromatography and gel filtration.

Synthesis of PClP

We synthesized PClP using Ag(I)-catalyzed cyclization to the pyrrole ring system (5).

Inhibition of Myosin-1c-dependent Cellular Processes

HeLa cells were grown to 50% confluence in RPMI 1640 containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, and 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin and treated for 16 h with 1 μm PClP in DMSO. To reduce the expression of myosin-1c, HeLa cells were transfected twice with control siRNA or siRNA specific for myosin-1c on days 1 and 3 using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen). PClP-treated and siRNA knockdown cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked with 1% BSA in PBS, and processed for indirect immunofluorescence using a monoclonal antibody to Lamp1 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa) to label lysosomes, Alexa Fluor 568-labeled phalloidin (Molecular Probes) to visualize actin filaments, and DAPI to stain the nucleus.

Kinetic Measurements

We measured basal and actin-activated Mg2+-ATPase activities using the NADH-coupled assay described previously (8, 12). The assay was performed at 25 °C in a buffer containing 25 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 25 mm KCl, and 4 mm MgCl2. The effect of PClP on the actin-activated myosin ATPase activity was measured in the presence of 20 μm F-actin and 1 mm ATP. PClP was added to the reaction mixture in the absence of nucleotide and incubated for 20 min before the reaction was started by the addition of ATP. Each reaction mixture including the controls contained 2.5% DMSO that was used as a solvent for the compound. Data were corrected for NADH absorption at 340 nm and expressed as relative myosin ATPase activity (in percentage of control), and additional data analysis was carried out with Origin 8 (OriginLab Corp.). Transient kinetic experiments were performed at 20 °C in an assay buffer containing 20 mm MOPS, 100 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, pH 7.0, with an SF-61 DX single mixing stopped-flow system (TgK Scientific Ltd.). PClP was excited at a wavelength of 365 nm, and fluorescence was detected at 416 nm. The in vitro motility assay was performed with a construct consisting of D. discoideum myosin-1B motor domain fused to an artificial lever arm. We measured sliding filament velocity at 25 °C using an Olympus IX81 inverted fluorescence microscope. The coverslip surface was treated with chlorotrimethylsilane (Sigma), and Pluronic F-127 (Sigma) served as a blocking agent. The program DiaTrack 3.01 (Semasopht) was used for automated actin filament tracking. Statistical data analysis was performed with Origin 8 (OriginLab Corp.).

Crystallography

D. discoideum myosin-2 motor domain construct M761 (15 mg/ml) was preincubated for 1 h at 4 °C with a mixture of sodium meta-vanadate (2 mm), ADP (2 mm), and PClP (0.5 mm) before crystallization. D. discoideum myosin-2:PClP complex was crystallized in the presence of 50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 140 mm NaCl, 11% w/v PEG 8000, 2% (v/v) 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, 5 mm MgCl2, 5 mm DTT, and 1 mm EGTA using the vapor diffusion hanging-drop method. The protein and the reservoir solution were mixed in a 1:1 ratio for crystallization. Before data collection, we soaked crystals for 5 min at 4 °C in a cryo-protection solution containing reservoir solution supplemented with 25% ethylene glycol. Subsequently, crystals were flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen. Crystals of space group C2221 produced diffraction data to 2.5 Å resolution. Data were collected with a wavelength of 0.9871 Å at BESSY (BL14-1). Data processing and scaling were performed with XDS (13). Molecular replacement and model refinement were performed using CNS, excluding a random 5% of the data for cross-validation (14). Model building and validation were carried out with COOT (15) and MolProbity (16). Statistics are summarized in Table 1. Coordinates were deposited with Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 2XEL.

TABLE 1.

Summary of data collection and refinement statistics

| Myosin-2-ADP·VO3-pentachloropseudilin | |

|---|---|

| Data collection | |

| Space group | C2221 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9871 |

| Cell dimensions | |

| a, b, c (Å) | 89.53, 147.49, 153.78 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90, 90, 90 |

| Rsym (%) | 6.2 (48.3)a |

| I/σI | 15.97 (5.01) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (100) |

| Redundancy | 8.2 (8.4) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 24.6-2.5 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 22.9/25.3 |

| No. of reflections working/test set | 33755/1777 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 6240 |

| Ligands/ions | 48/1 |

| Water | 458 |

| r.m.s.b deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.008 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.6 |

| Ramachandran plot (% Favored/allowed/outliers)b | 92.3/7.7/0 |

a Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell (2.60–2.50).

b r.m.s., root mean square.

c Residues in favored, allowed, and outlier regions of the Ramachandran plot as reported by MolProbity (21).

In Silico Modeling

Homology models of class-1 myosins (D. discoideum myosin-1B (SwissProt: P34092), Rattus norvegicus myosin-1b (SwissProt: Q05096), R. norvegicus myosin-1c (SwissProt: Q63355), class-2 (Oryctolagus cuniculus myosin-2 (GenBankTM: AAA74199)), and class-5 myosins (D. discoideum myosin-5b (SwissProt: P54697)) were built using MODELLER 9v6 (17). The motor domain structure of D. discoideum myosin-1E (1LKX) (18) was used as template to build D. discoideum myosin-1B, R. norvegicus myosin-1b, and R. norvegicus myosin-1c myosin motor domains. The motor domain structures of D. discoideum myosin-2 (2JJ9) (6) and G. gallus myosin-5a (1OE9) (19) were used as templates to build O. cuniculus myosin-2 and D. discoideum myosin-5b motor domains, respectively. All motor domain models of myosins were built using closely related pre-power stroke state motor domain template structures with sequence similarity greater than 60%. Missing loop regions in the homology models were built by Modeler followed by energy minimization using GROMACS 4 (20).

Docking

The ligand (PClP) was generated and energy-minimized with ChemDraw (CambridgeSoft). Protein input files for docking were prepared by GOLD (21). Initially, we performed blind docking of PClP for all the myosins examined. We found PClP preference to the PBP binding pocket (with highest Goldscore of 30–40 depending on myosin isoform). Further, we focused on the PClP binding site based on blind docking results and also from the experimental binding mode of PClP. We performed local docking using the partial flexible docking feature of GOLD, 8–10 residues in each case, for protein side chains in the binding pocket and limited the search to a radius of 10 Å from the active site.

The binding pocket was defined to comprise all residues within 10 Å of atom 2746 (-Nζ atom of Lys-186 in D. discoideum myosin-1B), atom 1523 (-Nζ atom of Lys-189 in R. norvegicus myosin-1c), atom 1515 (-Nζ atom of Lys-192 in R. norvegicus myosin-1b), atom 2789 (-Nζ atom of Lys-186 in D. discoideum myosin-1E), and atom 4234 (-Nζ atom of Lys-289 in D. discoideum myosin-5B). Docking was performed using the “Genetic algorithm” implemented in GOLD. We used the “Goldscore-Chemscore” protocol. In this protocol, docking poses produced with the Goldscore function are used for initial scoring, and then the Chemscore function is used for final ranking. Twenty solutions were generated for each myosin. In all instances, at least one of the top five solutions (Goldscore 35–40) converged to a similar pose for the myosins tested. The best poses deviated by ≤1 Å, when compared with the experimental ligand bound structure (2XEL).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

PClP Is a Potent Inhibitor of Class-1 Myosins

To elucidate the inhibitory potency and selectivity of PClP for individual myosin isoforms, we tested the effect of the compound on the ATPase activity of myosins from different classes in the absence and presence of filamentous actin (F-actin). The addition of PClP greatly decreased the rate of actin-activated ATP turnover for members of myosin classes 1, 2, and 5, whereas human myosin-6 and myosin-7a motor domain constructs showed no sign of inhibition in the presence of 100 μm PClP. The most potent inhibition was observed for class-1 myosins. Plots of the observed rates against the logarithm of inhibitor concentration could be fitted to sigmoidal curves (Fig. 1A). The IC50 values for D. discoideum myosin-1B, R. norvegicus myosin-1b, and R. norvegicus myosin-1c correspond to 1.0, 5.0, and 5.6 μm, respectively. The potency of PClP for the inhibition of class-2 and class-5 myosins is considerably lower. IC50 values corresponding to 126, 91, and 99 μm were observed with D. discoideum myosin-2, O. cuniculus myosin-2, and D. discoideum myosin-5b, respectively (Fig. 1A).

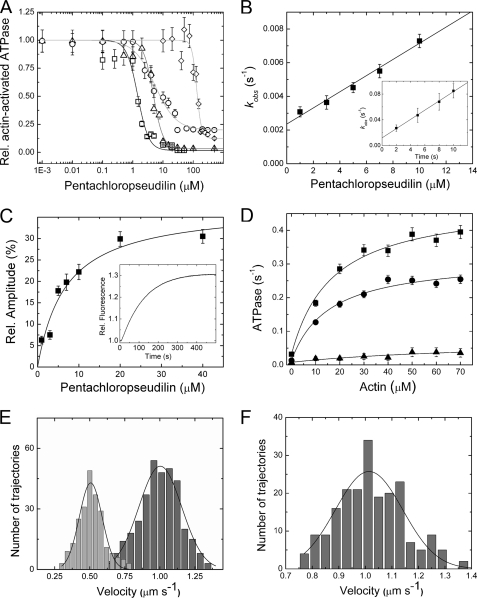

FIGURE 1.

PClP-induced changes in myosin function. A, effect of PClP on myosin actin-activated ATPase activity. The semi-logarithmic plot shows the [PClP] dependence of the inhibition for D. discoideum myosin-1B (Vmax = 0.54 ± 0.10 s−1) (□), R. norvegicus myosin-1b (Vmax = 0.39 ± 0.08 s−1) (△), R. norvegicus myosin-1c (Vmax = 0.75 ± 0.23 s−1) (○), and D. discoideum myosin-2 (Vmax = 0.53 ± 0.03 s−1) (♢). The concentrations of PClP required for half-maximal inhibition (IC50) of the different myosin motors were determined from sigmoidal fits of the data. Rel., relative. Error bars indicate S.E. B, binding and dissociation kinetics for the interaction of PClP with D. discoideum myosin-1B. The observed rate constants for the exponential increase in fluorescence intensity that follows rapid mixing of PClP with D. discoideum myosin-1B display a linear dependence on [PClP] in the range from 1 to 10 μm. The gradient of the plot specifies an apparent second-order rate constant for PClP binding to D. discoideum myosin-1B (k+I = 0.48 ± 0.04 × 10−3 μm−1s−1), whereas the y-intercept defines an apparent dissociation rate constant of k−I = 2.4 ± 0.2 × 10−3 s−1. In the presence of 1 mm ATP, a 15-fold increase in the apparent second-order rate constant for PClP binding (k+I,ATP = 7.19 ± 0.25 × 10−3 μm−1s−1) and a 5-fold increase in the apparent dissociation rate constant (k−I,ATP = 11.8 ± 1.8 × 10−3 s−1) are observed (inset). Error bars indicate S.E. C, direct determination of the affinity of PClP for D. discoideum myosin-1B in the absence of F-actin and nucleotides. Shown is the [PClP] dependence of the change in fluorescence intensity. A hyperbolic fit to the data gives a KI of 4.2 ± 0.8 μm for PClP binding to D. discoideum myosin-1B. The inset shows the increase in fluorescence intensity that follows rapid mixing of PClP with D. discoideum myosin-1B. The process can be fitted to a single exponential function. Error bars indicate S.E. D, PClP-mediated inhibition of the actin-activated ATPase activity of D. discoideum myosin-1B. The ATPase activity at increasing concentrations of F-actin from 0 to 70 μm is shown. Hyperbolic Michaelis-Menten functions are fitted to the data at 0 (■), 1 (●), and 5 μm PClP (▴). Error bars indicate S.E. E, D. discoideum myosin-1B moves actin filaments in the in vitro motility assay with an average velocity of 1.01 ± 0.13 μm s−1 (dark gray bars). In the presence of 2 μm PClP (light gray bars), filament velocity is reduced to 0.51 ± 0.1 μm s−1. F, a complete washout of the inhibitor reconstitutes the motile activity of uninhibited D. discoideum myosin-1B with an average velocity of 1.01 ± 0.3 μm s−1.

To investigate the interaction of PClP with class-1 myosins in detail, we took advantage of the 30% increase in fluorescence intensity of the compound that occurs upon binding to myosin. Stopped-flow transients observed following the rapid mixing of PClP with myosin motor domain constructs are well described by single exponential functions in the absence and presence of F-actin or nucleotides. The observed rate constants are linearly dependent on the PClP concentration in the range from 1 to 10 μm (Fig. 1B). A typical transient obtained for PClP binding to D. discoideum myosin-1B is shown in Fig. 1C in the inset. In the absence of both F-actin and nucleotides, an apparent second-order rate constant for PClP binding to D. discoideum myosin-1B (k+I = 0.48 ± 0.04 × 10−3 μm−1s−1) is given by the gradient of the plot, whereas the y-intercept defines an apparent dissociation rate constant of k−I = 2.4 ± 0.2 × 10−3 s−1. The ratio k−I/k+I defines an apparent dissociation equilibrium constant (KI) of 5.0 ± 0.9 μm. Alternatively, the KI for D. discoideum myosin-1B can be determined by plotting the observed changes in fluorescence amplitude against the PClP concentration (Fig. 1C). The resulting data are well described by a hyperbola and give a value of 4.2 ± 0.8 μm for KI. In the presence of saturating concentrations of F-actin, values of 0.22 ± 0.04 × 10−3 μm−1s−1, 0.52 ± 0.1 × 10−3 s−1, and 2.4 ± 0.8 μm for k+I, k−I, and KI are observed (data not shown). Additionally, we determined the binding kinetics of PClP to D. discoideum myosin-1B during active ATP turnover in the presence of 1 mm ATP (Fig. 1B, inset). When compared with the apo state, the apparent second-order rate constant for PClP binding is ∼15-fold increased (k+I,ATP = 7.19 ± 0.25 × 10−3 μm−1s−1), whereas the apparent dissociation rate constant is only 5-fold increased (k−I,ATP = 11.8 ± 1.8 × 10−3 s−1). This gives an apparent dissociation equilibrium constant (KI,ATP) of 1.64 ± 0.32 μm, which is in good agreement with the IC50 value of 1 μm observed for D. discoideum myosin-1B in the ATPase assay.

PClP Is a Reversible Inhibitor of Myosin Motor Activity

PClP binding reduces the affinity of myosin for F-actin in the presence of ATP and the coupling between actin and nucleotide binding sites. To estimate the extent to which PClP binding affects coupling, we determined the ATPase activity for D. discoideum myosin-1B over the range from 1 to 70 μm F-actin (Fig. 1D). Values for kcat and Km(actin) were estimated from fits of hyperbolic functions to the data. The kcat value of 0.45 ± 0.03 s−1 in the absence of PClP is reduced to 0.3 ± 0.02 s−1 in the presence of 1 μm PClP. The addition of 5 μm PClP results in a further decrease in kcat to 0.07 ± 0.04 s−1. The corresponding Km(actin) values from the Michaelis-Menten fits are 17.0 ± 3.0 μm (in the absence of PClP), 15.6 ± 3.1 μm (at 1 μm PClP), and 84.0 ± 77 μm (at 5 μm PClP). The apparent second-order rate constant for F-actin binding in the presence of ATP (kcat/Km(actin)) is a direct measure of the coupling efficiency between the nucleotide and actin binding sites. The addition of 5 μm PClP leads to a more than 30-fold reduction in coupling efficiency from 0.028 to 0.00088 μm−1s−1. A direct weakening effect on the actomyosin interaction is indicated by observations following the addition of PClP to actomyosin-decorated glass surfaces. A D. discoideum myosin-1B motor domain construct, fused to an artificial lever arm of 12 nm in length, moves F-actin with an average velocity of 1.01 ± 0.13 μm s−1 in the in vitro motility (8). The addition of 2 μm PClP results in a more than 2-fold reduction of the average sliding velocity to 0.51 ± 0.08 μm s−1 (Fig. 1E). Higher concentrations of PClP lead to dissociation of the filaments from the assay surface. Washout of the inhibitor results in complete recovery of motile activity. This result shows that inhibition of myosin motor activity by PClP is reversible (Fig. 1F).

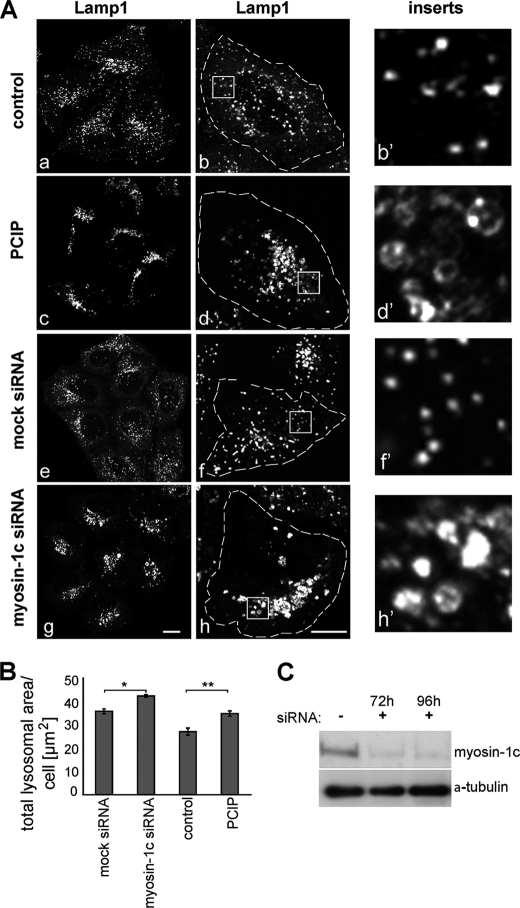

PClP Inhibits Cellular Functions of Human Myosin-1c

We next tested whether PClP inhibits myosin-1c in vivo. In mammals, myosin-1c is involved in a number of highly specialized tissue-specific functions, such as the adaptation of mechanoelectrical transduction in the hair cells of the inner ear and the translocation of glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) transporters to the plasma membrane in adipocytes. In addition, myosin-1c appears to function in the late endocytic pathway, which delivers endocytosed macromolecules to the lysosome for degradation (22). This observation is supported by our demonstration that inhibiting myosin-1c function by RNA interference causes defects in lysosome morphology and intracellular localization of this organelle. As shown in Fig. 2A, loss of myosin-1c expression after transfection of siRNA specific for myosin-1c causes a collapse and clustering of Lamp1-positive lysosomes in the perinuclear region on one side of the nucleus. Furthermore, the lysosomes in these myosin-1c knockdown cells dramatically change their morphology and become large, swollen ring-like structures (Fig. 2A, inserts panel). To test the activity of PClP in a cellular environment, HeLa cells were treated for 16 h with non-toxic concentrations of PClP between 1 and 5 μm. Cytotoxic effects of PClP in this cell type were only observed at concentrations above 25 μm. Interestingly, in PClP-treated HeLa cells, we observed identical changes in lysosome morphology and distribution (Fig. 2A) as observed in myosin-1c siRNA knockdown cells. These observations were quantified by measuring the number and size of lysosomes in a large population of cells (>7000 cells) using high throughput microscopy and fully automated imaging software. Although there was no significant change in the number of lysosomes upon myosin-1c siRNA transfection or PClP treatment (data not shown), the total area covered by these organelles was significantly increased under these conditions due to the enlarged size of the lysosomes (Fig. 2B). Taken together, these results indicate that in mammalian cells, PClP inhibits myosin-1c function at a concentration of 1 μm.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibition of Homo sapiens myosin-1c by PClP causes clustering and swelling of mammalian lysosomes. A, in control HeLa cells without PClP treatment (panels a and b) or siRNA transfection (panels e and f), lysosomes are small vesicular organelles that are distributed throughout the cells. In PClP-treated (panels c and d) and myosin-1c siRNA-transfected cells (panels g and h), the lysosomes are clustered in the perinuclear region, where they are frequently tethered to form larger aggregates. In addition, they are significantly larger in size and appear swollen. The left panels (panels a, c, e, and g) show confocal images of a group of cells stained for lysosomes with an antibody to Lamp1. The middle panels (panels b, d, f, and h) show enlarged confocal images of single cells, further highlighting the aggregated, swollen lysosomes in PClP-treated and myosin-1c siRNA-depleted cells. On the right, in the inserts panels, the panels (b′, d′, f′, and h′) are higher magnifications of the boxed regions. Bars, 10 μm. B, to quantify swelling of lysosomes, HeLa cells treated with/without PClP and mock- or myosin-1c siRNA-transfected cells were labeled with antibodies to Lamp1 for high throughput microscopy. Automated imaging software was used to quantify the total area covered by lysosomes per single cells. A significant increase in the lysosomal area was observed in PClP- and myosin-1c siRNA-treated cells when compared with control cells. A total number of 7775 cells from three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate, was analyzed. Error bars indicate S.E. *, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.005. C, to verify myosin-1c knockdown, cell lysates of mock- and myosin-1c siRNA-treated HeLa cells were blotted and probed with antibodies to myosin-1c and α-tubulin as a loading control.

Structural Basis of PClP-mediated Inhibition

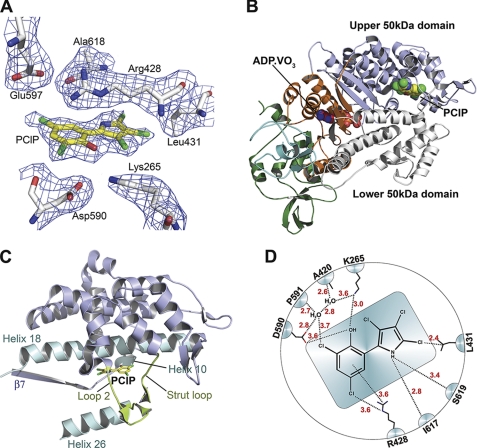

Co-crystallization studies were performed with motor domain constructs derived from three class-1 isoforms. However, these constructs proved refractory to crystallization. Therefore, we co-crystallized and solved the structure of the D. discoideum myosin-2 motor domain complexed to Mg2+-ADP-meta-vanadate in the presence of PClP. Crystals of space group C2221 produced diffraction data to 2.5 Å resolution (Table 1). The crystallographic results are in good agreement with the allosteric mechanisms inferred from the kinetic data. PClP binds near actin binding residues at the tip of the 50-kDa domain, at a distance of ∼16 Å from the nucleotide binding site (Fig. 3A). This is the same allosteric binding pocket previously described for PBP (6). However, both the conformation of PClP and the details of the interaction with myosin residues in the binding pocket differ from those observed with PBP (supplemental Fig. S2). The average root mean square deviation for PClP and PBP is 2.3 Å. The planar anti-conformer of PClP binds to myosin. This differs from the binding mode of PBP, where the syn-conformer is observed to bind with the phenyl and pyrrole ring systems bent 12° out of plane and twisted 20° against each other (6) (supplemental Fig. S2). Three helices and three loops contribute to PClP binding. Toward the actin binding interface, PClP is enclosed by the strut loop (Asn-588-Gln-593) and loop 2 (Asp-614-Thr-629). Toward the core of the motor domain, the binding pocket is lined by helix 10 (Lys-265-Val-268) and helix 18 (Val-411-Leu-441) from the upper 50-kDa domain. Additionally, helix 26 (Val-630-Glu-646) and the loop connecting β7 (Ile-253-Leu-261) with helix 10 contribute to the binding pocket (Fig. 3, B and C). The total protein surface area in contact with PClP comprises 240 Å2.

FIGURE 3.

Structure of D. discoideum myosin-2 motor domain in complex with PClP and Mg2+-ADP-meta-vanadate. A, section of the 2Fo − Fc electron density omit map, contoured at 1.0 σ, depicting the PClP binding site. B, overall view of the myosin motor domain in ribbon representation. PClP and ADP·VO3 are shown in spheres mode; N-terminal residues are shown in green, and the C-terminal converter region are shown in cyan. C, close-up view of allosteric binding pocket with protein residues in graphic representation and PClP in stick representation. Important structural features around the binding pocket are colored and labeled accordingly. D, schematic view of the anti-conformer of PClP and its contact residues. Contacts with residues closer than 4 Å are shown.

A network of interactions stabilizes PClP binding. Important binding site rearrangements include a change in the orientation of the side chain of Lys-265, which moves 3.1 Å from its position in the uninhibited form to facilitate formation of a hydrogen bond between the ϵ-amino group and the hydroxyl group of PClP. The amino group of the pyrrole ring interacts with the main chain carbonyl groups of Ile-617 and Ser-619. Two water molecules form part of a network of interactions that involves the main chain carbonyl groups of Ala-420 and Pro-591, the side chains of Lys-265 and Asp-590, and the hydroxyl and 2-chloro groups of the phenyl ring. Additional interactions are formed between the side chains of Arg-428 and Leu-431 and chloro groups of the inhibitor (Fig. 3D).

Myosin Isoform-dependent Interactions with PClP

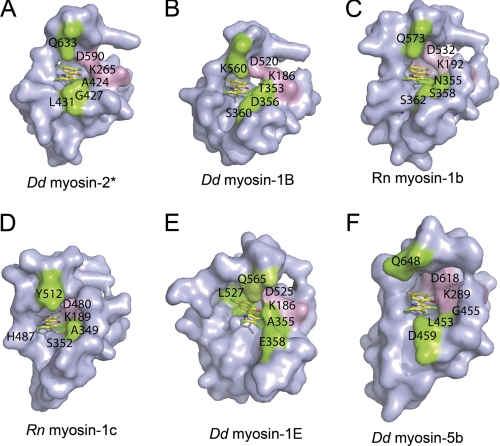

To rationalize the structural basis for the experimentally observed preferred inhibition of class-1 myosins, we performed docking studies using the crystal structure of the motor domain of D. discoideum myosin-1E (1LKX) and homology models of D. discoideum myosin-1B, D. discoideum myosin-5b, R. norvegicus myosin-1b, and R. norvegicus myosin-1c in the pre-power stroke state. For all myosin isoforms tested, initial blind docking studies predict that PClP binds to the same site described above for the complex with the D. discoideum myosin-2 motor domain. To achieve better sampling of the translational, rotational, and torsional degrees of freedom of the ligand, we performed local docking using a 10 Å grid around this site. The highest ranked binding poses are shown in Fig. 4, and the predicted contact residues for PClP in complex with the individual myosin isoforms are shown in Table 2. The results of the docking studies indicate that the contact between the hydroxyl group of PClP and Lys-265 is a common and important feature of the interaction between myosin and effector molecule. Additionally, the polarity of the allosteric binding pocket appears to make an important contribution to the preferred binding of PClP to class-1 myosins (Fig. 4 and Table 2).

FIGURE 4.

Surface representation of the PClP binding site in different myosin isoforms. Highly conserved residues interacting with PClP are shown in pink. Non-conserved residues interacting with PClP are colored green. Amino acid residues are indicated using the single letter code. A–F, PClP binding pocket of D. discoideum (Dd) myosin-2 crystal structure (*, reference structure) (A); D. discoideum myosin-1B (B); R. norvegicus (Rn) myosin-1b (C); R. norvegicus myosin-1c (D); D. discoideum myosin-1E (E); and D. discoideum myosin-5b (F).

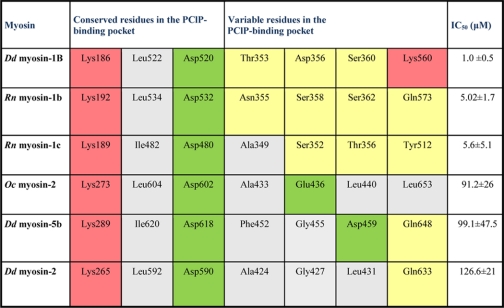

TABLE 2.

PCIP binding site with contact residues for different myosin isoforms

Selected residues interacting with PCIP are shown for D. discoideum (Dd) myosin-1B, R. norvegicus (Rn) myosin-1b, R. norvegicus myosin-1C, O. cuniculus (Oc) myosin-2 and D. discoideum myosin-5b. The half maximal inhibitory concentration of PCIP (IC50) is shown for each myosin isoform. Residues in the binding pocket are color-coded according to their polarity. Uncharged polar residues are shown in yellow, acidic residues are in green, basic residues are in red, and non-polar residues are in gray.

Energetic Coupling between Active and Allosteric Binding Sites

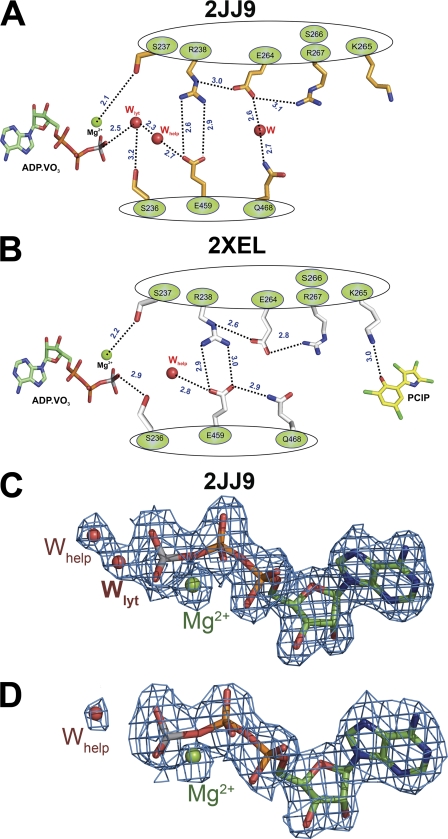

Because x-ray crystallography favors particular stable intermediates, observable changes resulting from the binding of an allosteric effector tend to be subtle in terms of impact on an experimentally determined three-dimensional structure (23). Experimental manifestations of an allosteric effect are thus frequently limited to the rates of interchange between different conformer populations at any given point along the enzymatic reaction coordinate (24). Typical for this type of energetic coupling between the active and allosteric sites, the available x-ray structures in the presence (2XEL) and absence (2JJ9) of bound PClP do not indicate a major conformational change. The myosin backbone Cα atoms in both structures superimpose with a root mean square deviation of 0.4 Å.

Analysis of pre-power stroke state myosin structures in the absence and presence of PClP indicates the existence of a communication pathway that transmits information between the allosteric and nucleotide binding sites. A network of hydrogen bonds extends over a distance of 19 Å, forming a direct link between PClP and the γ-phosphate position of ATP. The network involves side chain as well as main chain interactions. Lys-265 is the starting point for this allosteric relay mechanism. The ϵ-amino group of Lys-265 moves 3.1 Å from its position in the uninhibited form to facilitate an interaction with the hydroxyl group of PClP. The salt bridge connecting Arg-238 in Switch I with Glu-459 in Switch II forms part of the relay path. The distance between Arg-238 and Glu-459 increases by 0.3 Å upon PClP binding. Other key residues involved in the relay mechanism are Ser-236 and Ser-237 in Switch I, Gln-468 in the relay helix, and residues Lys-265, Ser-266, and Arg-267 in helix 10 (Fig. 5, A and B). The major consequence of the rearrangements induced by PClP binding is the displacement of the “catalytic water” molecule at the active site, as indicated by comparison of 2Fo − Fc electron density maps (Fig. 5, C and D). Electron density for a water molecule positioned appropriately for in-line attack to the γ-phosphate analog of nucleotide is present in the active site of the pre-power stroke state structures with bound ADP·VO3 (2JJ9), ATPγS, (1MMG), ADP-AlF4 (1W9L), and N-methylanthraniloyl-ADP-BeFx (1D1C) (6, 25, 26) but absent in structure 2XEL with bound ADP·VO3 and PClP (supplemental Fig. S3). The detailed analysis of the PClP bound structure enabled us to identify the same allosteric pathways in the myosin motor domain structures with bound PBP (2JHR) and tribromodichloropseudilin (2XO8) (6, 7). The inhibitor-induced change in Lys-265 rotamer, the movement of the same key residues along the relay path, and the absence of the catalytic water are shared features by these structures.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic illustration of the relay pathway connecting the allosteric pocket and the nucleotide binding site in the absence and presence of PClP. A, residues involved in the relay pathway and selected side chains are shown for the myosin motor domain in the absence of PClP (2JJ9). B, PClP-induced changes in the orientation of selected side chains along the relay pathway. Distances between residues are shown as dashed lines indicated in Å. Main chain interactions are not explicitly shown. C, in the absence of PClP, the 2Fo − Fc electron density for Mg·ADP·VO3 in structure 2JJ9 allows the unambiguous placement of an extra water molecule. This water molecule is ideally positioned for inline attack relative to Vγ and can thus act as catalytic water. D, PClP binding induces the displacement of the catalytic water. Mg·ADP·VO3 fits into the 2Fo − Fc electron density map from structure 2XEL obtained in the presence of PClP. The 2Fo − Fc electron density maps are contoured at 1.5 σ. Side chains and ADP-meta-vanadate are shown in stick mode. Magnesium ion (green) and waters (red) are shown as spheres; Wlyt denotes the lytic water molecule, and Whelp denotes the helper water.

Conclusion

Allosteric effectors that target myosin motors with high affinity and specificity are key tools in cytoskeletal research. Here, we report that the natural product PClP can be used as a potent and selective inhibitor of class-1 myosins in cell biological studies. The optical properties of the compound allow the direct observation of its binding interactions with myosins. Our detailed kinetic and structural analysis indicate that PClP is a non-competitive, reversible inhibitor of myosin motor activity that acts in part by reducing the coupling between the actin and nucleotide binding sites. Isoform-specific differences in the potency of PClP-mediated inhibition can be rationalized by differences in the size and polarity of the allosteric binding pockets of myosin isoforms (Fig. 4). In contrast to these differences in size and polarity, the residues involved in the relay pathway connecting the allosteric and active sites over a distance of 19 Å show a higher degree of conservation between myosin isoforms (supplemental Fig. S1). This suggests that the same communication pathway plays an important role in coupling information between the actin and nucleotide binding sites during normal catalytic turnover.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at beamline BL14-1, BESSY II, Berlin, Germany for support; Daniela Kathmann for providing D. discoideum myosin-1E; and Petra Baruch for excellent technical assistance. The Cambridge Institute for Medical Research is in receipt of a strategic award from the Wellcome Trust.

The work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grant MA 1081/16-1 and the Cluster of Excellence “Rebirth” (to D. J. M.), Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (to D. J. M. and H.-J. K.), a Wellcome Trust University Award (to F. B.), a Wellcome Trust Studentship (to H. B.), National Institutes of Health Grant DC008793 (to L. M. C.), and the Medical Research Council (J. K.-J.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2XEL) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

- PBP

- pentabromopseudilin

- PClP

- pentachloropseudilin

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- ATPγS

- adenosine 5′-O-(thiotriphosphate)

- BeFx

- beryllium fluoride

- AlF4

- aluminium fluoride.

REFERENCES

- 1. Walsh D. P., Chang Y. T. (2006) Chem. Rev. 106, 2476–2530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehár J., Stockwell B. R., Giaever G., Nislow C. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 674–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Limouze J., Straight A. F., Mitchison T., Sellers J. R. (2004) J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 25, 337–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheung A., Dantzig J. A., Hollingworth S., Baylor S. M., Goldman Y. E., Mitchison T. J., Straight A. F. (2002) Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 83–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Martin R., Jäger A., Böhl M., Richter S., Fedorov R., Manstein D. J., Gutzeit H. O., Knölker H. J. (2009) Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 48, 8042–8046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fedorov R., Böhl M., Tsiavaliaris G., Hartmann F. K., Taft M. H., Baruch P., Brenner B., Martin R., Knölker H. J., Gutzeit H. O., Manstein D. J. (2009) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 80–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Preller M., Chinthalapudi K., Martin R., Knölker H. J., Manstein D. J. (2011) J. Med. Chem. 54, 3675–3685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dürrwang U., Fujita-Becker S., Erent M., Kull F. J., Tsiavaliaris G., Geeves M. A., Manstein D. J. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 119, 550–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manstein D. J., Hunt D. M. (1995) J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 16, 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Perreault-Micale C., Shushan A. D., Coluccio L. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21618–21623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Adamek N., Coluccio L. M., Geeves M. A. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 5710–5715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Furch M., Geeves M. A., Manstein D. J. (1998) Biochemistry 37, 6317–6326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kabsch W. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Emsley P., Lohkamp B., Scott W. G., Cowtan K. (2010) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Davis I. W., Leaver-Fay A., Chen V. B., Block J. N., Kapral G. J., Wang X., Murray L. W., Arendall W. B., 3rd, Snoeyink J., Richardson J. S., Richardson D. C. (2007) Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W375–W383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eswar N., Webb B., Marti-Renom M. A., Madhusudhan M. S., Eramian D., Shen M. Y., Pieper U., Sali A. (2007) Curr. Protoc. Protein Sci. Chapter 2, Unit 2.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kollmar M., Dürrwang U., Kliche W., Manstein D. J., Kull F. J. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 2517–2525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Coureux P. D., Wells A. L., Ménétrey J., Yengo C. M., Morris C. A., Sweeney H. L., Houdusse A. (2003) Nature 425, 419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Van Der Spoel D., Lindahl E., Hess B., Groenhof G., Mark A. E., Berendsen H. J. (2005) J. Comput Chem. 26, 1701–1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Verdonk M. L., Cole J. C., Hartshorn M. J., Murray C. W., Taylor R. D. (2003) Proteins 52, 609–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Poupon V., Stewart A., Gray S. R., Piper R. C., Luzio J. P. (2003) Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 4015–4027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goodey N. M., Benkovic S. J. (2008) Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 474–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Swain J. F., Gierasch L. M. (2006) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16, 102–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gulick A. M., Bauer C. B., Thoden J. B., Pate E., Yount R. G., Rayment I. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 398–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gulick A. M., Bauer C. B., Thoden J. B., Rayment I. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 11619–11628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.