Abstract

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) regulates cell polarity and migration by generating phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3) at the leading edge of migrating cells. The serine-threonine protein kinase Akt binds to PI(3,4,5)P3, resulting in its activation. Active Akt promotes spatially regulated actin cytoskeletal remodeling and thereby directed cell migration. The inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases (5-ptases) degrade PI(3,4,5)P3 to form PI(3,4)P2, which leads to diminished Akt activation. Several 5-ptases, including SKIP and SHIP2, inhibit actin cytoskeletal reorganization by opposing PI3K/Akt signaling. In this current study, we identify a molecular co-chaperone termed silencer of death domains (SODD/BAG4) that forms a complex with several 5-ptase family members, including SKIP, SHIP1, and SHIP2. The interaction between SODD and SKIP exerts an inhibitory effect on SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase catalytic activity and consequently enhances the recruitment of PI(3,4,5)P3-effectors to the plasma membrane. In contrast, SODD−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts exhibit reduced Akt-Ser473 and -Thr308 phosphorylation following EGF stimulation, associated with increased SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3-5-ptase activity. SODD−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts exhibit decreased EGF-stimulated F-actin stress fibers, lamellipodia, and focal adhesion complexity, a phenotype that is rescued by the expression of constitutively active Akt1. Furthermore, reduced cell migration was observed in SODD−/− macrophages, which express the three 5-ptases shown to interact with SODD (SKIP, SHIP1, and SHIP2). Therefore, this study identifies SODD as a novel regulator of PI3K/Akt signaling to the actin cytoskeleton.

Keywords: Akt PKB, Cell Migration, Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase, Phosphatidylinositol Phosphatase, Phosphatidylinositol Signaling, Signal Transduction, Silencer of Death Domains (SODD), Skeletal Muscle and Kidney Enriched Inositol Phosphatase (SKIP), Actin Cytoskeleton, Inositol Polyphosphate 5-Phosphatase

Introduction

The phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling pathway regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and cell migration. The class Ia PI3K generates phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PI(3,4,5)P3)3 in response to growth factor-dependent receptor stimulation. PI(3,4,5)P3 promotes the recruitment and allosteric activation of effector signal transduction proteins that contain pleckstrin homology (PH) domains (1). A well characterized downstream effector of PI(3,4,5)P3 is the serine/threonine protein kinase Akt, which phosphorylates both cytosolic and nuclear targets, leading to increased cell proliferation and prolonged cell survival (2). PI(3,4,5)P3 signaling is also a general regulator of cytoskeletal dynamics that directs cell migration. The accumulation of PI(3,4,5)P3 occurs at the site of F-actin polymerization, causing transient pseudopod extension and lamellipodia formation (3). PI(3,4,5)P3-mediated reorganization of actin cytoskeletal structures can occur by activation of Akt, which in turn phosphorylates PAKa, actin, or actin-regulatory proteins, such as girdin (4–6). The role of Akt in cell migration is both isoform-specific and cell type-dependent (7–9).

PI(3,4,5)P3 is present only transiently at the plasma membrane following its synthesis, due to its rapid degradation by multiple lipid phosphatases. The phosphoinositide 3-phosphatase phosphatase and tensin homology deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN) hydrolyzes PI(3,4,5)P3, forming phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to halt agonist-stimulated growth signals. Another pathway of PI(3,4,5)P3 degradation is via hydrolysis of the 5-position phosphate by inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatases (5-ptases) to form PI(3,4)P2 (10, 11). The 5-ptases comprise 10 mammalian members and share a common 300-amino acid catalytic domain that exhibits 30% amino acid sequence identity within family members (12). Many 5-ptases, including SHIP1, SHIP2, Inpp5e, SKIP, and PIPP, hydrolyze PI(3,4,5)P3 to generate PI(3,4)P2 and thereby reduce Akt activation. The identification of human syndromes associated with mutations in 5-ptases and mouse 5-ptase knock-out studies have collectively revealed that this enzyme family regulates pleiotropic events, including hematopoietic proliferation and neutrophil migration (SHIP1), insulin signaling and weight gain (SHIP2), macrophage phagocytosis (SHIP1 and -2 and Inpp5e), synaptic vesicle recycling (synaptojanin1), endocytosis (synaptojanin2), cilia function (Inpp5e), vesicular trafficking (OCRL), and embryonic development (SKIP and Inpp5e) (10, 13, 14).

Many 5-ptases that degrade PI(3,4,5)P3 and inhibit Akt signaling regulate actin dynamics and cell migration. Overexpression of the 5-ptase SKIP reduces actin stress fiber assembly and insulin-stimulated lamellipodia formation (15, 16). Global homozygous knock-out of the SKIP gene in mice leads to midgestational lethality for unknown reasons, whereas SKIP heterozygosity results in enhanced insulin-stimulated PI3K/Akt signaling (17). SHIP1 is expressed exclusively in hematopoietic cells and plays a preeminent role over PTEN in regulating neutrophil chemotaxis by modulating cell polarization and the directional motility of neutrophils in response to chemokines (18). The related 5-ptase SHIP2, which is ubiquitously expressed, exhibits both enzymatic and adaptor functions to regulate the actin cytoskeleton. Overexpression of SHIP2 results in diminished EGF-stimulated PI(3,4,5)P3/Akt signaling at the plasma membrane, which negatively affects submembraneous actin polymerization and membrane ruffle formation (19). SHIP2 also forms multiprotein complexes with actin cytoskeletal regulatory proteins to modulate cell adhesion and spreading (20, 21).

In this study, we identify that SKIP, SHIP1, and SHIP2 interact with a molecular co-chaperone designated “silencer of death domains” (SODD; also called BAG4). SODD belongs to the Bcl-2-associated athanogene (BAG) family of proteins (BAG1 to -6) and contains a conserved BAG domain at the C terminus and a proline-rich N-terminal region (22). BAG proteins interact with hepatocyte growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor (23), and the androgen receptor (24), suggesting a functional regulatory role in modulating various intracellular signaling pathways. In addition, BAG proteins (BAG1, -2, and -3) compete with Hip for binding to the ATPase domain of Hsc70 and thereby negatively regulate Hsc70-mediated refolding of target proteins (25). SODD forms numerous multiprotein complexes and binds to the death domain of TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1) to prevent constitutive signaling in the absence of TNF-α (26). SODD also interacts with Hsc70, the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 and the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor, although the functional consequences of these interactions are not well characterized (27, 28). Here we demonstrate that SODD inhibits SKIP 5-ptase-mediated degradation of PI(3,4,5)P3, thereby regulating Akt signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. Collectively, our studies identify SODD/BAG4 as a novel regulator of PI3K/Akt signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

General and Cell Culture Reagents

C57BL/6 SODD−/− mice and spontaneously immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were a kind gift from Dr. Wen-Chen Yeh (University of Toronto, Canada). [γ-32P]ATP was from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. The phalloidin-Alexa Fluor488 and DNase I- Alexa Fluor594 were from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). EGF was from Chemicon (Australia). The His and FLAG antibodies were from Sigma; HA antibody was from Covance (Richmond, CA); GST antibody was from GE Healthcare; Xpress antibody was from Invitrogen; PTEN antibody was from Sigma; β-tubulin antibody was from Zymed Laboratories Inc. (San Francisco, CA); paxillin antibody was from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Jose, CA); and Akt, Foxo1, and all phospho-specific antibodies, including Akt-Ser473, Akt-Thr308, and Foxo1-Ser256, were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). The SODD and SKIP (29) antibodies were generated in our laboratory.

Yeast Two-hybrid Analysis

Yeast strain AH109 was co-transformed with the bait (full-length SKIP cDNA) and cDNA library (mouse testis). The co-transformed yeasts were plated onto yeast agar plates lacking leucine and tryptophan (−2 plates) to confirm transformation or plates lacking leucine, tryptophan, adenine, and histidine (−4 plates) to detect potential interactions. Plasmid DNA was purified from all yeast colonies obtained on −4 plates and electroporated into Top 10 Escherichia coli cells. The plasmid DNAs isolated from bacteria were analyzed for nonspecific interaction with SV40 large T-antigen (SV40-T) and p53 as well as inappropriate activation of reporter genes by growth on nutrient-deficient plates.

Direct Binding Assays

E. coli strain BL31 DE3 Gold Codon Plus RP (Stratagene) bacteria transformed with pTRCHISA/pGEX5x1 (Amersham Biosciences)-containing mouse SODD constructs were grown overnight in LB with 50 μg/ml ampicillin until the A600 reached 0.6. Protein production was initiated by the addition of 0.1 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, the culture was grown at room temperature for 3 h, and cells were collected by centrifugation. Human SKIP cDNA was cloned into the pSVTf in vitro transcription/translation vector and incubated with the TNT® coupled wheat germ extract system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Bacterially expressed His-tagged protein was incubated with in vitro transcribed and translated [35S]Met-labeled protein, along with 60 μl of Talon resin (Clontech) 50% slurry for 2 h to overnight, rocking at 4 °C. The mixture was centrifuged briefly to collect the supernatant, and the pellet was washed six times with 1 ml of lysis buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 10% sucrose (w/v), 1% Triton X-100 (v/v), 250 μg/ml PMSF, 1 mm benzamidine, 400 μm leupeptin, and 400 μm aprotinin).

Culturing and Transfection of Mammalian Cells

Primary MEFs were isolated from 13-day-old SODD+/+ or SODD−/− embryos (E13) and used within passage 7 before clonality was established. Experiments utilizing primary MEFs were conducted using MEFs derived from three different embryos for each genotype. For some experiments, as indicated, MEFs were spontaneously immortalized by continued passaging (30). MEFs were maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, and COS-7 cells were maintained in 10% newborn calf serum in addition to 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1% streptomycin. For all indirect immunofluorescence studies involving COS-7 cells, the dextran chloroquine transfection method was undertaken. The transfection reaction mixture included 200 μl of dextran choloroquine (400 μg/ml dextran, 100 μm chloroquine), 5 μg of DNA, and 5 ml of serum-free DMEM, which was added to a 50% confluent 10-cm dish, incubated for 2 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2, and then treated with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 min at room temperature before being allowed to recover in growth medium. For all immunoprecipitation and GST pull-down studies, COS-7 and MEF cells were electroporated, where 5 μg of DNA was added, along with 15 μl of 0.15 m NaCl and sterile pure H2O in electroporation cuvettes (4 mm). The cells were electroporated at 0.2 kV and 975 microfarads and incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 36–48 h.

Western Blotting

Cells were washed twice with PBS, lysed in 500 μl of either Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (5 mm Tris, pH 7.4, and 1% Nonidet P-40) or radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (5 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 1% Triton X-100 (v/v), 0.2% SDS (w/v), 0.2% sodium deoxycholate (w/v), 1 mm EDTA) with 1 mm benzamidine, 2 mm PMSF, 2 mm sodium vanadate, 50 mm NaF, 10 mm sodium pyrophosphate, 400 μm leupeptin, and 400 μm aprotinin and allowed to rock at 4 °C for 1 h and then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 20 min. 30–50 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE, and immunoblot analysis was conducted using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent according to the manufacturer's protocol (Amersham Biosciences).

Immunoprecipitation

1 ml of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer- or Nonidet P-40 buffer-soluble fractions were used for immunoprecipitations with ∼6 μg of monoclonal HA or FLAG antibodies in the presence of 60 μl of 50% protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) slurry. The mixture was incubated by gentle rocking at 4 °C overnight and centrifuged briefly to recover the immunoprecipitate and supernatant. The pellet was washed six times in Tris-saline, pH 7.4, including 1% Triton X-100 or Nonidet P-40. Immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by immunoblotting.

Mammalian GST Pull-down

GST pull-down assays were carried out with radioimmune precipitation assay buffer- or Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer-soluble fractions of appropriately transfected mammalian cells, as described in the figure legends. 500 μl of detergent-soluble fraction was incubated with 60 μl of a 50% glutathione-Sepharose bead slurry at 4 °C for 2 h to overnight. The pellet was washed four times with Tris-saline, pH 7.4, including either 1% Triton X-100 or Nonidet P-40, and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Subcellular Fractionation of Mammalian Cells

COS-7 cells were lysed in a hypoosmotic solution containing protease inhibitors via 20 strokes of a Dounce homogenizer. The lysate was then centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was further centrifuged at 42,400 × g for 1 h. Immunoprecipitation using the HA antibody was carried out on the resulting supernatant. The pellets from the immunoprecipitation were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis with the FLAG or HA antibody.

PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 5-ptase Assay

COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with constructs encoding FLAG-SODD; HA-SKIP; or HA-SHIP2, FLAG, or HA. MEFs were transiently transfected with constructs encoding HA-SKIP or HA alone. 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested, and lysates were immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies as above. Samples were washed three times in ice-cold kinase buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.8, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA), and then PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase assays were performed on the immunoprecipitates. 50 μl of PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 was prepared and added to the immunoprecipitates together with 4 μl of 20× kinase buffer (400 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mm MgCl2, 20 mm EGTA). 10 μmol of unlabeled PI(3,4,5)P3 was also added to each reaction for 5-ptase assays on immunoprecipitates from MEF lysates. Reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, and the lipids were extracted and analyzed by TLC.

Indirect Immunofluorescence

All cell lines utilized in this study for indirect immunofluorescence were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde, PBS for 20 min and then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, PBS for 5 min. Cells were then washed three times with PBS and blocked with 1% BSA, PBS for 15 min, followed by incubation with primary and secondary antibodies for 1 h each. Cells were analyzed with FV500 confocal microscopy with an argon-krypton triple line laser at Monash Biochemistry Imaging Facility.

Cell Adhesion Assay

MEFs were detached using EDTA, and 4 × 105 cells were plated onto uncoated glass coverslips (6-well dish) and then left at 37 °C with 5% CO2, for 30, 60, 120, or 240 min, before being fixed and stained with phalloidin-Alexa Fluor488. Cell adhesion was analyzed in 10 random fields by fluorescence microscopy and scored using a cell counter.

Retroviral Transduction

Retroviruses encoding human myr-Akt1 were generated. Briefly, the BING replication-incompetent virus packaging cell line was electroporated with myr-Akt1-pWZL, and virus-containing supernatant was harvested and added to cultures of SODD−/− cells. Drug-resistant SODD−/− colonies were isolated after 7 days of growth in selection medium containing 100 μg/ml hygromycin B (Invitrogen). However, all experiments were performed in the absence of hygromycin B.

Macrophage Derivation from Bone Marrow

Bone marrow-derived macrophages were extracted from the femurs of SODD+/+ or SODD−/− C57BL/6 male mice aged 8–10 weeks. The bone marrow was flushed and cultured in complete macrophage growth and differentiation medium (DMEM with 15% fetal calf serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 100 units/ml penicillin, 0.1% streptomycin, and culture supernatant from murine L-cells, a source of macrophage colony-stimulating factor). The following day, all nonadherent cells were split into separate dishes and grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2. On the 3rd and 6th day, 2.5 ml of L-cell culture supernatant was added to each dish. Differentiated macrophages were used for experiments on days 7–10.

Transwell Migration Assay

Transwell membrane filter inserts (Corning Glass) containing 8-μm pores were utilized in this assay. Day 7 differentiated bone marrow-derived macrophages were harvested using trypsin, and 3 × 105 cells were added to each Transwell chamber to a final volume of 100 μl (growth and differentiation medium containing macrophage colony-stimulating factor) and then placed into a 24-well dish containing 600 μl of growth and differentiation medium. Bone marrow-derived macrophages were incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 24 h. Cells that had migrated through the pores and adhered to the underside of the top insert were fixed and stained using the DiffQuik staining kit (Lab Aids P/L).

Terminal dUTP Nick-end Labeling (TUNEL) Apoptosis Assay

Apoptosis was detected and quantified using TUNEL assays by utilizing the fluorescein in situ cell death detection kit (Roche Applied Science).

Image Analysis (ImageJ)

In this study, image analysis was conducted by utilizing the public domain ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). Where fluorescence intensity was compared, all images for a single experiment were taken at the same laser attenuation. For assessment of plasma membrane PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 accumulation in COS-7 cells, the relative fluorescence intensity of the phosphoinositide biosensors was measured as a ratio of the average pixel intensity within three areas of intense GFP or YFP accumulation at the plasma membrane and compared with the average pixel intensity of three areas of the cytosol within the same cell. Statistical significance was calculated using an unpaired Student's t test, where p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

SODD Binds to SKIP in Vitro and in Vivo

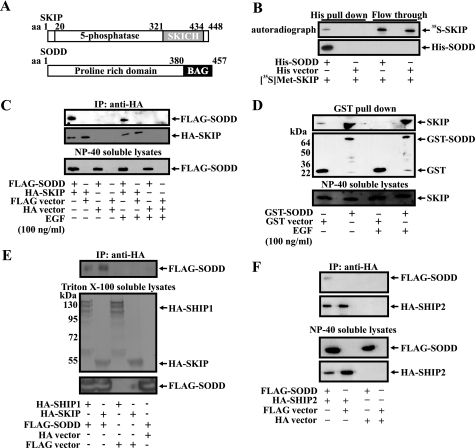

To identify proteins that complex with and regulate 5-ptases, we utilized the smallest PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase, SKIP, as a bait in yeast two-hybrid screening of a mouse testis library. SKIP contains the common 5-ptase catalytic domain and a C-terminal SKICH domain (Fig. 1A) (29). Several rounds of screening of a mouse testis library isolated a partial mouse cDNA (aa 72–456) encoding the silencer of death domain (SODD/BAG4) (Fig. 1A). Control experiments confirmed the fidelity of this interaction, because neither SKIP nor SODD autonomously activated reporter genes in the yeast two-hybrid system when grown on appropriate nutrient-deficient medium (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

SODD and SKIP interaction. A, schematic depicting SKIP and SODD functional domains. B, His-SODD expressed in E. coli was immobilized on Talon resin and, after extensive washing, was incubated with [35S]Met-SKIP. Complexes captured on Talon resin were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography (top) or by Western blot (bottom). C, COS-7 cells co-expressing FLAG-SODD and HA-SKIP or vector controls were serum-starved and/or stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml, 10 min). Nonidet P-40-soluble fractions were immunoprecipitated (IP) with HA antibodies and immunoblotted with FLAG (top) or HA (middle) specific antibodies. Input lysates are shown in the bottom panel. D, HEK293 cells expressing GST-SODD or GST were serum-starved and/or EGF-stimulated (100 ng/ml, 10 min). Nonidet P-40-soluble fractions were incubated with glutathione-Sepharose. Bound proteins eluted in SDS-PAGE buffer (top two panels) or Nonidet P-40-soluble input fractions (bottom panel) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with GST or SKIP antibodies. E and F, detergent-soluble fractions derived from COS-7 cells expressing HA-SHIP1 or HA-SKIP and FLAG-SODD (E) or HA-SHIP2 and FLAG-SODD (F) and vector controls were immunoprecipitated using HA antibodies. Soluble input fractions (bottom panels) and anti-HA immunoprecipitates (top panels) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with FLAG or HA antibodies.

Several experimental approaches were undertaken to verify that SKIP and SODD form a complex. Because SODD/BAG4 binds to several proteins and receptors, we first demonstrated direct protein-protein binding between purified SODD and SKIP proteins using in vitro binding assays in a cell-free system. SODD was expressed in E. coli as a fusion protein with a hexa-His tag, and recombinant SKIP was produced by in vitro translation in the presence of [35S]methionine. Following incubation of the two purified proteins, [35S]Met-SKIP bound to His-SODD that was coupled to Talon resin (Fig. 1B) but not Talon resin alone. In further studies, purified GST-SODD, but not GST alone, bound [35S]Met-SKIP (data not shown). Therefore, SKIP directly binds SODD and does not require the presence of an additional protein(s). To demonstrate a SKIP-SODD complex in intact cells, COS-7 cells were co-transfected with FLAG-SODD and HA-SKIP. FLAG-SODD was detected in anti-HA immunoprecipitates from lysates derived from HA-SKIP- and FLAG-SODD-co-expressing cells but not vector controls (Fig. 1C). No significant difference in the level of complex between SKIP and SODD was demonstrated following EGF stimulation, suggesting constitutive association (Fig. 1C).

An association between endogenous SKIP and recombinant SODD was demonstrated by transfecting HEK293 cells with GST-SODD, capturing complexes on glutathione-Sepharose, and immunoblotting using SKIP antibodies, revealing a 56-kDa immunoreactive species, consistent with endogenous SKIP in complex with recombinant SODD (Fig. 1D). In reciprocal experiments, GST-SKIP interacted with endogenous SODD from both serum-starved or EGF-stimulated cells (supplemental Fig. 1A). However, we were unable to detect an endogenous SKIP-endogenous SODD complex by immunoprecipitation due to the relatively low affinity of both commercially available and our SKIP or SODD antibodies.

Next we examined whether SODD forms a complex with other PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptases. SHIP1 and SHIP2 exhibit both overlapping and distinct functions in regulating the actin cytoskeleton (18, 19). HA-SHIP1 or HA-SHIP2 was co-transfected with FLAG-SODD in COS-7 cells, and anti-HA immunoprecipitates revealed SODD in complex (Fig. 1, E and F). We also investigated whether SODD associates with the PI(4,5)P2 5-ptase, OCRL, which also regulates cytoskeletal dynamics. However, anti-FLAG immunoprecipitates from FLAG-SODD- and Xpress-OCRL-co-expressing cells did not demonstrate the presence of Xpress-OCRL (supplemental Fig. 1B). Therefore, SODD complexes with the PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptases, SKIP, SHIP1, and SHIP2 but not with OCRL.

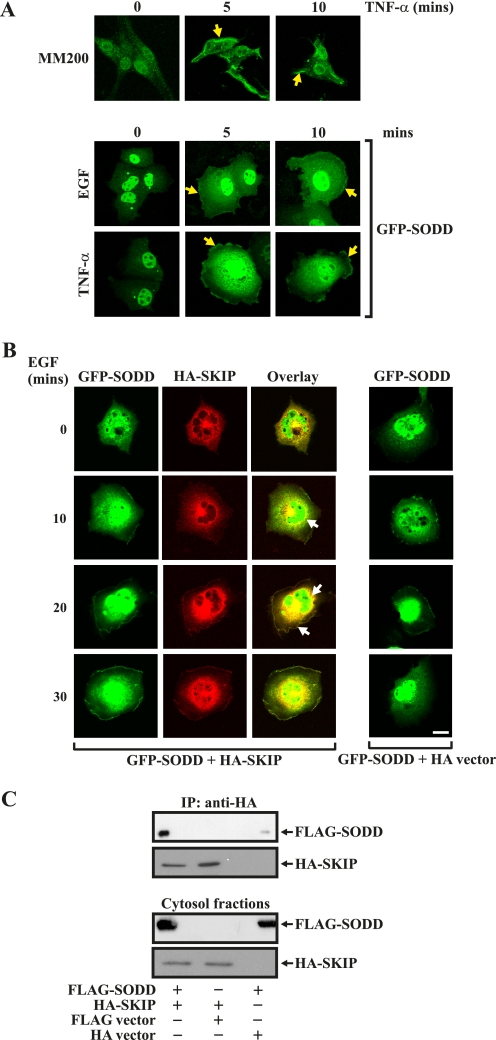

Co-localization of SKIP and SODD

We investigated whether SKIP and SODD co-localize in the same subcellular compartment. SKIP localizes in a perinuclear region in serum-starved cells and, in response to growth factor stimulation, translocates to the plasma membrane, where its substrate PI(3,4,5)P3 is synthesized (29). In previous studies, SODD has been shown to localize to the nucleus, cytosol, or plasma membrane, depending on the cell type and/or stimulus (31–33). We examined the localization of endogenous SODD in the melanoma cell line, MM200, using affinity-purified SODD antibodies. Endogenous SODD was nuclear in nonstimulated cells and, in response to TNF-α stimulation, was detected in the nucleus, in the cytosol, and at the plasma membrane (Fig. 2A). Similarly, GFP-SODD was nuclear in nonstimulated COS-7 cells and demonstrated nuclear, cytoplasmic, and plasma membrane localization in response to TNF-α or EGF stimulation. To determine if SKIP and SODD co-localize, the distribution of GFP-SODD and HA-SKIP was analyzed. Under serum-starved conditions, GFP-SODD was predominantly nuclear, with faint cytosolic distribution (Fig. 2B). As reported (29), HA-SKIP localized to a perinuclear region in nonstimulated cells (Fig. 2B). Upon EGF stimulation, GFP-SODD co-localized with HA-SKIP both in the cytosol and at the plasma membrane within 20 min (Fig. 2B, closed arrows). To confirm SODD and SKIP complex in the cytosol, COS-7 cells co-expressing FLAG-SODD and HA-SKIP were subfractionated into cytosol and membrane fractions. FLAG-SODD co-immunoprecipitated with HA-SKIP from the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Co-localization of SKIP and SODD. MM200 cells were serum-starved and stimulated with TNF-α for the indicated times, fixed, permeabilized, stained with SODD antibodies, and visualized by confocal microscopy (top panel). COS-7 cells were transfected with GFP-SODD or vector alone for 48 h and then serum-starved and stimulated with either EGF or TNF-α for the indicated times and fixed and visualized by confocal microscopy (bottom panels). Yellow closed arrows indicate plasma membrane localization. B, COS-7 cells were transiently co-transfected with GFP-SODD and HA-SKIP or vector controls, EGF (100 ng/ml)-stimulated, fixed, stained with HA antibodies, and imaged by confocal microscopy. Closed arrows indicate co-localization of GFP-SODD with HA-SKIP. Bar, 20 μm. C, cytosolic fractions of COS-7 cells expressing FLAG-SODD and HA-SKIP or vector controls were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures,” and HA immunoprecipitates (IP) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with FLAG or HA antibodies (top two panels). Cytosol input fractions immunoblotted with either FLAG or HA antibodies are shown in the bottom two panels.

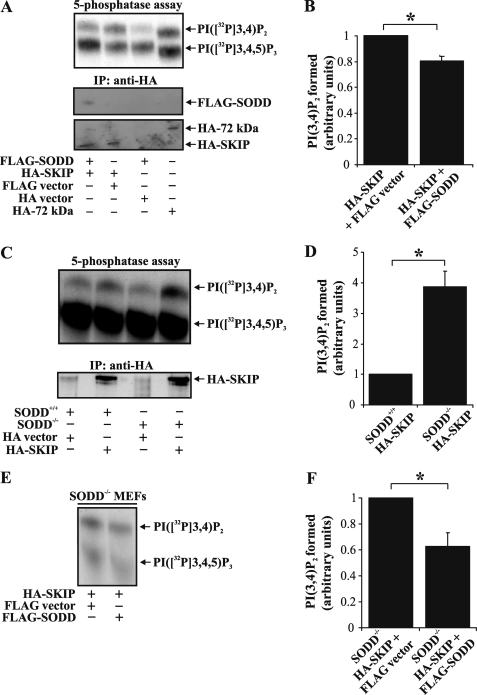

SODD Inhibits PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase Enzyme Activity

PI(3,4,5)P3 is hydrolyzed by SKIP, SHIP1, and SHIP2 to form PI(3,4)P2. The 5-ptases frequently assemble into multiprotein complexes that regulate enzyme activity. For example, binding of Rab5 to Inpp5B enhances its PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity (34), whereas SHIP2 interacts with an adaptor protein containing PH and SH2 domains (APS), resulting in increased SHIP2 PI(3,4,5)P3 phosphatase activity (35). To investigate if SODD regulates PI(3,4,5)P3 degradation, HA-SKIP was immunoprecipitated from COS-7 cells co-expressing FLAG-SODD or vector controls, and PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 5-ptase assays were performed on immunoprecipitates. As a positive control for PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase hydrolysis in the absence of SODD, 72-kDa 5-ptase (Inpp5e) catalytic activity was assessed (36). A typical PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 5-ptase assay is shown in Fig. 3, A, C (upper panels), and E. HA-SKIP hydrolyzed PI ([32P]3,4,5)P3, forming PI([32P]3,4)P2. Enzyme activity upon FLAG-SODD co-expression (as determined by PI([32P]3,4)P2 formed) was reduced by ∼20% (n = 5, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). However, FLAG-SODD did not significantly inhibit HA-SHIP2-mediated PI(3,4,5)P3 hydrolysis under the same experimental conditions (supplemental Fig. 2, A and B). Next, we evaluated whether SODD deficiency affected PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity. To this end, HA-SKIP was expressed in spontaneously immortalized MEFs derived from either wild type (SODD+/+) or SODD-deficient (SODD−/−) mice. HA-SKIP was immunoprecipitated from MEFs, and PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity was determined. We noted a ∼3.9-fold increase (n = 3, p < 0.05) in HA-SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity isolated from SODD−/−, relative to SODD+/+ MEFs (Fig. 3, C and D). To assess whether the increased SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity isolated from SODD−/− MEFs was a result of SODD deficiency, we expressed FLAG-SODD in SODD−/− MEFs (Fig. 3E). Notably, expression of FLAG-SODD reduced HA-SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity in SODD−/− MEFs by ∼37% (n = 4, p < 0.05) (Fig. 3F). Taken together, these results indicate that SODD inhibits SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase enzyme activity.

FIGURE 3.

SODD inhibits SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity. A, COS-7 cells transiently transfected with FLAG-SODD and HA-SKIP or vector controls or HA-72kDa 5-phosphatase alone (positive control) were lysed and immunoprecipitated (IP) with HA antibodies and either subjected to PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 5-ptase assay and the reaction products analyzed by TLC (top) or immunoblotted with FLAG (middle) or HA (bottom) antibodies. The migration of PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 and PI([32P]3,4)P2 lipids is shown on the right. B, the level of PI([32P]3,4)P2 formed was determined by densitometry and represented relative to that detected in HA immunoprecipitates derived from HA-SKIP- and FLAG-expressing cells (arbitrarily set as 1). Bars, mean ± S.E. (error bars) of five independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). C, wild-type (SODD+/+) or SODD-deficient (SODD−/−) MEFs were transiently transfected with HA-SKIP or HA-vector, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 5-ptase assays, and the reaction products were analyzed by TLC (top). Parallel immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with HA antibodies for protein loading (bottom). Results are representative of three independent experiments. D, the level of PI([32P]3,4)P2 formed was determined by densitometry and represented as a relative value to that detected in HA immunoprecipitates derived from SODD+/+ MEFs (arbitrarily set as 1). Bars, mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). E, SODD−/− MEFs were transiently co-transfected with either HA-SKIP and FLAG empty vector or FLAG-SODD. Cells were lysed and immunoprecipitated with HA antibodies. Immunoprecipitates were subjected to PI([32P]3,4,5)P3 5-ptase assays, and the reaction products were analyzed by TLC. Results are representative of four independent experiments. F, the level of PI([32P]3,4)P2 formed was determined by densitometry and represented as a relative value to that detected in HA immunoprecipitates derived from SODD−/− MEFs expressing HA-SKIP and FLAG-empty vector (arbitrarily set as 1). Bars, mean ± S.E. of four independent experiments (*, p < 0.05).

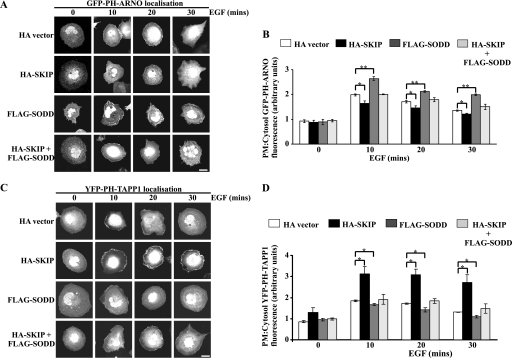

SODD Regulates the Recruitment of PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 Effectors to the Plasma Membrane

As SODD inhibits SKIP hydrolysis of PI(3,4,5)P3, this in turn may impact on the recruitment of PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2 effectors to the plasma membrane. The subcellular localization of the GFP-tagged PH domain of ARNO (GFP-PH-ARNO), which specifically binds PI(3,4,5)P3 (19, 37), was determined when this construct was co-expressed with HA-SKIP, FLAG-SODD, or HA-SKIP/FLAG-SODD, relative to vector controls in COS-7 cells (Fig. 4A). In serum-starved cells, GFP-PH-ARNO was not detected at the plasma membrane regardless of the construct(s) expressed. Upon EGF stimulation, GFP-PH-ARNO translocated to the plasma membrane within 10 min. Notably, FLAG-SODD-co-expressing cells exhibited sustained GFP-PH-ARNO plasma membrane localization for up to 30 min poststimulation, suggesting that 5-ptase activity was inhibited (Fig. 4A). Quantitative analysis of the plasma membrane GFP-PH-ARNO fluorescence relative to the cytosol of the same cell, revealed a ∼25% increase in FLAG-SODD-expressing cells, relative to vector controls following 10-min EGF stimulation (Fig. 4B). In contrast, HA-SKIP expression reduced GFP-PH-ARNO plasma membrane/cytosol fluorescence. The relative GFP-PH-ARNO fluorescence in HA-SKIP/FLAG-SODD-expressing cells was comparable with vector controls (Fig. 4B). Therefore, SODD may enhance the recruitment of PI(3,4,5)P3-binding proteins to the plasma membrane via inhibition of 5-ptase degradation of PI(3,4,5)P3.

FIGURE 4.

Regulation of PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 effector recruitment to the plasma membrane by SODD. A and C, COS-7 cells were transiently co-transfected with plasmids encoding GFP-PH-ARNO (A) or YFP-PH-TAPP1 (C) with either HA-vector, HA-SKIP, FLAG-SODD, or HA-SKIP and FLAG-SODD. Cells were stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) fixed, permeabilized, and stained with either HA and/or FLAG antibodies (not shown) to identify transfected cells. Bars, 20 μm. B and D, the fluorescence intensity of GFP-PH-ARNO (B) or YFP-PH-TAPP1 (D) biosensor at the plasma membrane (PM) as a relative ratio to the level detected in the cytosol was quantitated using ImageJ analysis software. The average intensity of ∼150 pixels within three areas of the plasma membrane was determined relative to three areas of ∼500 pixels within the cytosol of the same cell. 4–10 cells were quantified per construct expressed for each of three experiments. Bars, mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001).

SKIP degrades PI(3,4,5)P3 to generate PI(3,4)P2 at the plasma membrane. The PH domain of TAPP1 binds PI(3,4)P2 with high specificity and, when fused to YFP (YFP-PH-TAPP1), can be used as a biosensor (30). Serum-starved COS-7 cells did not exhibit YFP-PH-TAPP1 fluorescence at the plasma membrane. Following 10-min EGF stimulation, YFP-PH-TAPP1 was observed at the plasma membrane, which was sustained for up to 30 min in cells expressing HA-SKIP (Fig. 4C). The ratio of plasma membrane/cytosol fluorescence was ∼1.7-fold higher in HA-SKIP-expressing cells than vector controls (Fig. 4D), and this ratio was significantly reduced upon co-expression of FLAG-SODD (Fig. 4D). Therefore, SKIP degrades PI(3,4,5)P3 to produce PI(3,4)P2, a reaction that is inhibited by SODD, resulting in enhanced recruitment of PI(3,4,5)P3 effectors but reduced association of PI(3,4)P2-binding proteins with the plasma membrane.

SODD Regulates Akt Phosphorylation

A significant PI(3,4,5)P3 effector is the serine/threonine kinase Akt, which binds to both PI(3,4,5)P3 and PI(3,4)P2 via its PH domain, and this interaction facilitates full Akt activation mediated by phosphorylation of critical residues by PDK1 and mTORC2 (38, 39). Despite the dual role of both phosphoinositides in Akt activation, most studies have demonstrated that overexpression of 5-ptases reduces PI(3,4,5)P3 levels, leading to increased PI(3,4)P2, associated with a reduction in Akt activation (10). To investigate if SODD influences Akt activation, as a consequence of its regulation of 5-ptase hydrolysis of PI(3,4,5)P3, we analyzed the kinetics of Akt phosphorylation in primary (Fig. 5, A–E) and spontaneously immortalized (supplemental Fig. 3, B and C) SODD+/+ or SODD−/− MEFs in response to EGF stimulation. Primary MEFs were isolated from individual SODD−/− versus SODD+/+ embryos and used within less than seven passages. Primary SODD−/− MEFs exhibited reduced Akt-Ser473 and Akt-Thr308 phosphorylation at 5 and 10 min post-EGF stimulation relative to wild type MEFs (Fig. 5, A, B, and D). The level of Akt-Ser473 and Akt-Thr308 phosphorylation, standardized to total Akt at 5-min EGF stimulation, was quantified by densitometry for two independent experiments and was reduced by ∼50% in SODD−/− MEFs relative to wild type (Fig. 5, C and E). The level of Akt-Ser473 phosphorylation was also decreased by ∼50% in spontaneously immortalized SODD−/− MEFs compared with SODD+/+ MEFs stimulated with EGF (supplemental Fig. 3, B and C). Consistent with these results, ectopic expression of SODD in COS-7 cells enhanced Akt-Ser473 phosphorylation in response to EGF treatment (data not shown). Control studies revealed that the levels of SKIP, SHIP2, and the lipid 3-phosphatase PTEN were similar in SODD−/− compared with SODD+/+ MEFs (supplemental Fig. 3A). It should be noted that SHIP1 expression is restricted to hematopoietic cells (10) and was not detected in MEFs (data not shown). These results suggest that SODD regulates SKIP PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity and hence PI3K-mediated Akt activation in response to growth factor stimulation.

FIGURE 5.

Akt signaling in SODD−/− MEFs is reduced. A, primary SODD+/+ or SODD−/− MEFs were serum-starved and either left untreated or stimulated with EGF (40 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies specific for either phospho-Akt-Ser473 (top), phospho-Akt-Thr308 (middle), or Akt (bottom) antibodies. Shown are representative immunoblots from two independent experiments. B and D, primary SODD+/+ or SODD−/− MEFs were treated as in A, and the level of phospho-Akt-Ser473 (B) or phospho-Akt-Thr308 (D) was determined by densitometry, standardized to Akt protein control for each time point. C and E, primary SODD+/+ or SODD−/− MEFs were treated as in A, and the level of phospho-Akt-Ser473 (C) or phospho-Akt-Thr308 (E) at 5 min was determined by densitometry, standardized to Akt loading control, and represented as a relative value to that detected in SODD+/+ lysates (arbitrarily set as 1). Bars, mean ± S.E. (error bars) of two independent experiments. F and G, primary SODD+/+ or SODD−/− MEFs were treated as in A, and the level of phospho-Foxo1-Ser256 was determined by densitometry standardized to Foxo1 protein control for each time point. Shown are representative immunoblots from two independent experiments.

Akt regulates cell survival by phosphorylating BAD, caspase 9, and the forkhead family of transcription factors (Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4) (40, 41). Phosphorylation of Foxo1-Ser256 residue was reduced by >74% at 5–30 min in primary SODD−/− MEFs compared with SODD+/+ MEFs in response to EGF stimulation (Fig. 5, F and G). However, staurosporine or agonistic Fas antibody-induced apoptosis was similar in SODD+/+ and SODD−/− MEFs (supplemental Fig. 3D), consistent with previous observations (42, 43).

SODD Regulates Akt-dependent Actin Polymerization and Cell Migration

PI3K signaling regulates cell migration, adhesion, and spreading in many different cell types as PI(3,4,5)P3 binds to and regulates the activation of Akt, Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factors, Rac effectors, and GTPases such as ARF6 and indirectly regulates Rho GTPase signaling through crosstalk with other pathways (44, 45). In many cell types, overexpression of Akt leads to enhanced cell motility and invasion, in part due to the formation of membrane ruffles and actin cytoskeletal rearrangement (8, 46). However, recent studies have also revealed an anti-migratory role for Akt1 in human epithelial breast cancer cell lines, indicating cell type-specific roles for Akt isoforms in directing cell migration (47). SKIP ectopic expression decreases actin stress fibers (15) and reduces membrane ruffling (16). Similarly, expression of SHIP2 reduces the level of F-actin (19), whereas SHIP1 controls the polarization and directional mobility of neutrophils (18). To examine SODD regulation of PI3K-dependent actin stress fiber formation and membrane ruffling, the distribution of polymerized F-actin and monomeric G-actin was analyzed using fluorescent dyes conjugated to phalloidin and DNase I, respectively (19). In response to EGF stimulation, SODD+/+ immortalized MEFs exhibited an extensive network of actin stress fibers and submembraneous actin, as shown by phalloidin staining, that was reduced in SODD−/− MEFs (Fig. 6, A and C). The total cellular F-actin levels quantified by measuring the average fluorescence intensity of phalloidin-Alexa Fluor488 staining were reduced in SODD−/− MEFs by ∼40% compared with SODD+/+ in EGF-stimulated cells (Fig. 6B). Actin fiber assembly at the cell cortex can be identified by localizing monomeric G-actin (48). Following EGF stimulation, SODD+/+ immortalized MEFs exhibited membrane ruffle formation as shown by DNase I staining of submembraneous G-actin at the leading edge of the cell (Fig. 6A, closed arrow). In contrast, SODD−/− MEFs rarely formed membrane ruffles upon EGF stimulation, and the degree of lamellipodia extension was significantly reduced compared with SODD+/+ MEFs (Fig. 6A). To further evaluate if lamellipodia extension was reduced in SODD−/− MEFs, the percentage of cells exhibiting lamellipodia was quantified. Lamellipodia-positive MEFs were defined as cells that exhibited extensive subcortical F-actin or sheet-like projections containing F-actin. SODD+/+ and SODD−/− immortalized MEFs were serum-starved for 16 h and then stimulated with EGF for 20 min. EGF stimulation increased the percentage of SODD+/+ MEFs exhibiting lamellipodia to ∼50% of the cell population. In contrast, SODD−/− MEFs did not show an increase in the number of cells with lamellipodia relative to unstimulated SODD−/− MEFs (p < 0.05, n = 3) (Fig. 6, C and D). We also noted that focal adhesions, as identified by paxillin distribution, were reduced in complexity in primary SODD−/− MEFs relative to SODD+/+ controls (Fig. 6E). To determine whether the actin cytoskeletal changes detected in SODD−/− MEFs were a consequence of repressed PI3K/Akt signaling, SODD−/− immortalized cells were transduced with constitutively active myr-Akt1. Expression of myr-Akt1 increased both the total cellular and submembraneous F-actin, actin stress fibers (Fig. 6F, top; closed arrows indicate transfected cells) and focal adhesion complexity (Fig. 6F, bottom) in SODD−/− MEFs, relative to neighboring non-transfected cells (Fig. 6F; open arrows indicate nontransfected cells). Therefore, the observed actin cytoskeletal defects in SODD−/− MEFs are corrected by constitutively active Akt1.

FIGURE 6.

SODD−/− MEFs exhibit reduced actin polymerization. A, SODD+/+ or SODD−/− immortalized MEFs were serum-starved and stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 20 min. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and co-stained with phalloidin-Alexa Fluor488 (F-actin) and DNase I-Alexa Fluor594 (G-actin) and visualized by confocal microscopy at the same laser attenuation. Closed arrow, cortical G-actin, indicative of lamellipodia formation. B, SODD+/+ or SODD−/− immortalized MEFs were treated as in A, and the total cellular F-actin levels were quantified by measuring the average fluorescence intensity of phalloidin-Alexa Fluor488 in 4–5 cells for each genotype. Bars, mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). C, SODD+/+ and SODD−/− immortalized MEFs were serum-starved and stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 20 min. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with phalloidin-Alexa Fluor488 and visualized by confocal microscopy. D, MEFs were treated as in C, and the percentage of lamellipodia formation was quantified by calculating the average number of cells that demonstrated lamellipodia extension in ∼10 random fields from three independent experiments. Bars, mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). E, primary SODD+/+ or SODD−/− MEFs were grown in growth medium and then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with paxillin antibodies and visualized by confocal microscopy at the same laser attenuation. F, immortalized SODD−/− MEFs were reconstituted with constitutively active myristoylated Akt1 (HA-Myr-Akt1; closed arrows) by retroviral gene transfer; fixed, permeabilized, and co-stained with HA antibodies to identify transfected cells; and stained with phalloidin-Alexa Fluor488 (top) or paxillin antibodies (bottom) and imaged by confocal microscopy at the same laser attenuation. Open arrows, nontransfected cells. Bars, 20 μm.

During cell migration, agonist-stimulated signaling pathways mediate instructive changes to the actin cytoskeleton, which leads to the extension of the pseudopod via cortical actin reorganization. The extending leading edge of the cell is stabilized by traction forces generated by adhesive structures (49). In this regard, SODD−/− immortalized MEFs exhibited reduced cell adhesion, as determined by scoring the number of cells that adhered to glass coverslips over a 4-h time course (Fig. 7A). In addition, primary SODD−/− MEFs demonstrated a substantial reduction in the average cell area compared with SODD+/+ cells, indicative of diminished cell spreading (Fig. 7, B and C). We also assessed using Transwell migration chambers the chemotaxis of SODD−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages. Primary SODD−/− macrophages exhibited a migration defect because the number of cells that migrated through the pores of Transwell migration chambers was significantly reduced when compared with SODD+/+ macrophages (Fig. 7D). However, no significant changes in phagocytosis of IgG-coated beads (a PI3K-dependent event that requires actin rearrangement, microtubule polymerization, and generation of new membrane to form the phagocytic cup) was demonstrated in primary SODD−/− compared with SODD+/+ macrophages (data not shown). Therefore, SODD controls cell adhesion, spreading, and migration via regulation of PI(3,4,5)P3/Akt-dependent signaling to the actin cytoskeleton.

FIGURE 7.

SODD−/− cells exhibit reduced cell adhesion, spreading, and cell migration. A, 4 × 105 cells/well of SODD+/+ or SODD−/− immortalized MEFs were plated onto glass coverslips for the indicated times. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with phalloidin to identify cells. Cell adhesion was quantified by calculating the average number of adhered cells in 10 randomly chosen fields for each time point. Bars, mean ± S.E. (error bars) of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). B, SODD+/+ or SODD−/− primary MEFs were plated onto glass coverslips in the presence of growth serum for 16 h and then fixed, permeabilized, and stained with phalloidin and visualized by confocal microscopy. Bar, 80 μm. C, the relative area of either SODD+/+ or SODD−/− MEFs (≥39 cells/genotype/experiment) was calculated using ImageJ software. Bars, mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05). D, primary SODD+/+ or SODD−/− bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMM) were applied to Transwell migration chambers for 24 h in the presence of macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and cell migration was quantified by calculating the average number of migrated cells in 10 randomly chosen fields. Bars, mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments (*, p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study identifies that the molecular co-chaperone SODD complexes with and inhibits the catalytic activity of the inositol polyphosphate 5-phosphatase SKIP. As a consequence, SODD regulates growth factor-stimulated PI(3,4,5)P3/Akt signaling to the actin cytoskeleton and thereby reduces cell adhesion, spreading, and migration. We have demonstrated that SODD binds to the 5-ptase SKIP by various approaches, including Y2H interaction, direct binding of purified proteins, GST-pull-down of endogenous proteins, and co-localization of recombinant SKIP and SODD in the cytosol and the plasma membrane. SODD interaction with SKIP inhibits the PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity of SKIP. Interestingly, although SODD can also associate with other 5-ptases, such as SHIP1 and SHIP2, but not OCRL, we did not demonstrate changes in PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that in a different cellular context than COS-7 cells, or when SODD is expressed at high levels as has been observed in some cancers (50–52) or in inflammatory states, that SODD may inhibit the PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity of other 5-ptases, such as SHIP2, SHIP1, Inpp5e, or PIPP. Although the 5-ptase domain in all family members contains highly conserved catalytic motifs, only 30% overall amino acid identity exists between family members (12), providing considerable diversity in potential binding domains and/or regulation of its catalytic function.

The function of SODD in regulating PI3K/Akt signaling was analyzed using both SODD overexpression and knock-out primary MEFs and macrophages and spontaneously immortalized MEFs, revealing altered actin cytoskeleton dynamics leading to altered cell migration and adhesion. SODD expression enhanced the recruitment of PI(3,4,5)P3-binding PH domains but reduced the association of PI(3,4)P2-binding PH domains with the plasma membrane following growth factor stimulation. The serine/threonine kinase Akt is activated by binding of its PH domain to both PI(3,4,5)P3 and/or PI(3,4)P2 at the plasma membrane, although the precise kinetics of these interactions in vivo are emerging. However, many studies have shown that increased 5-ptase activity results in reduced Akt activation, and loss of 5-ptase function leads to enhanced Akt activity (10). Significantly, SODD−/− MEFs exhibited reduced Akt activation and downstream signaling in response to growth factor EGF stimulation. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that because SODD (BAG4) complexes with many different receptors, including the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor and TNFR1 (26, 28), SODD regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling may be agonist/receptor- or cell type-dependent. Indeed, we noted that in response to TNF-α stimulation in SODD−/− MEFs, Akt signaling was enhanced (data not shown), consistent with the known role of SODD in negatively controlling the activation of TNFR1.

We propose that SODD inhibits PI(3,4,5)P3 degradation following growth factor stimulation, and in its absence, the enhanced 5-ptase activity reduces Akt activation, leading to reduced Akt-dependent signaling to the actin cytoskeleton. In support of this model, reconstitution of constitutively active myr-Akt1 into SODD−/− MEFs restored actin stress fibers, submembraneous F-actin, and focal adhesion complexity. Although we have only examined the impact of Akt on the actin cytoskeleton in SODD−/− cells, we cannot exclude the possibility that other actin-regulatory proteins that are activated by PI(3,4,5)P3 may also be affected and contribute to the phenotype. Localized polymerization of F-actin is mediated by Rac guanine nucleotide exchange factors as well as Rac effectors, such as SCAR (WAVE) and WASP proteins, that bind to and are regulated by PI(3,4,5)P3 (44). ArhGAP15, a PH domain-containing Rac-GTPase-activating protein, also binds to and is activated by PI(3,4,5)P3 in migrating macrophages (53). The small GTPase Arf6 binds PI(3,4,5)P3 and regulates actin remodeling in motile cells (54–56). The cytohesin-2/ARF nucleotide-binding site opener (ARNO), a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, activates ARF1 and -6 via PI(3,4,5)P3 binding and thereby regulates actin dynamics (57). The role that Akt plays in modulating cytoskeletal dynamics is mediated via regulation of its targets, including girdin, actin, and ACAP1 (4–6, 50). Akt regulation of cell migration appears to be both isoform-specific and cell type-dependent. Expression of dominant negative Akt1 in fibroblasts blocks cell motility in response to either constitutively active Rac/Cdc42 expression or PDGF stimulation (7). Furthermore, Akt1−/− MEFs migrate more slowly relative to wild type cells, possibly due to reduced Pak1 and Rac activity (9). Interestingly, although we demonstrated Akt-dependent actin cytoskeletal defects in SODD−/− MEFs, like others (42, 43), we were also unable to show any alterations in cell survival. This may relate to the degree of SODD-mediated regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling. In SODD−/− MEFs, we noted a significant but not complete reduction in Akt-Ser473 and Thr308 phosphorylation upon EGF stimulation. This degree of residual Akt activation may be sufficient to maintain normal cell survival and proliferative functions but insufficient for actin cytoskeletal responses. Furthermore, it is likely that the presence of other 5-ptases and PTEN contributes to the regulation of PI3K/Akt signaling in addition to SKIP, SHIP1, and/or SHIP2.

Our study has identified a novel function for SODD in regulating PI3K/Akt signaling and thereby cell migration. Two independent studies have characterized SODD−/− mice. In one report, SODD−/− mice were physiologically normal (43), whereas in the other, SODD−/− mice exhibited increased cytokine secretion in response to TNF-α challenge (42). Actin cytoskeletal functions were not examined in either study. Furthermore, a direct role for SODD in regulating PI3K/Akt signaling has not been reported previously. As shown here, SODD−/− MEFs exhibited actin cytoskeletal defects, comprising reduced actin stress fibers, focal adhesion complexity, and lamellipodia formation correlating with increased PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity. The reduced actin stress fibers and F-actin assembly at the cell cortex leading to retarded lamellipodia formation in response to growth factor stimulation in SODD−/− MEFs is highly reminiscent of the effects on the actin cytoskeleton following overexpression of 5-ptase SKIP or SHIP2. For example, SKIP expression in CHO-IR cells reduced membrane ruffle formation induced by insulin stimulation (16). Overexpression of SHIP2, but not a mutant lacking the 5-ptase domain, reduced β-actin and F-actin levels at the extending lamellipodia during EGF stimulation.

Increased levels of PI(3,4,5)P3 signals are observed in up to 50% of all human cancers as a consequence of gain-of-function mutation in PI3K (PIK3CA) (58), loss of function of PTEN (59), or other yet to be determined mechanisms. Several studies have implicated SODD in aberrant PI3K/Akt signaling, although the molecular basis for these observations has not been delineated. SODD/BAG4 has been linked with the aggressiveness of breast, gastric, ovarian, and pancreatic cancers (31, 60). SODD expression increases significantly in pancreatic cancer compared with normal pancreas, correlating with high Akt activation, even in the absence of cell stimulation (60, 61), although the molecular mechanisms were not described. High expression of SODD was also identified in patients with childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, associated with increased phospho-NF-κB expression. SODD and NF-κB expression correlated with the onset of acute lymphoblastic leukemia, suggesting that SODD may represent a potential prognostic marker for this disease (62). It is intriguing to speculate that the observed increased SODD expression in cancer may enhance the activation of Akt, by inhibiting 5-ptase-mediated PI(3,4,5)P3 degradation. In conclusion, our study identifies a novel pathway for amplifying PI3K/Akt signaling via inhibition of PI(3,4,5)P3 5-ptase activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Wen-Chen Yeh (University of Toronto, Canada) for kindly providing the C57BL/6 SODD−/− mice and spontaneously immortalized MEFs.

This work was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Australia Grants 1010368 and 384137.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–3.

- PI(3,4,5)P3

- phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate

- PI(3,4)P2

- phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate

- 5-ptase

- 5-phosphatase

- BAG

- Bcl-2-associated athanogene

- PH

- pleckstrin homology

- MEF

- mouse embryonic fibroblast

- myr-Akt1

- myristoylated Akt1

- PTEN

- phosphatase and tensin homology deleted on chromosome ten.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vanhaesebroeck B., Leevers S. J., Ahmadi K., Timms J., Katso R., Driscoll P. C., Woscholski R., Parker P. J., Waterfield M. D. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 535–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brazil D. P., Yang Z. Z., Hemmings B. A. (2004) Trends Biochem. Sci 29, 233–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cain R. J., Ridley A. J. (2009) Biol. Cell 101, 13–29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cenni V., Sirri A., Riccio M., Lattanzi G., Santi S., de Pol A., Maraldi N. M., Marmiroli S. (2003) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 60, 2710–2720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vandermoere F., El Yazidi-Belkoura I., Demont Y., Slomianny C., Antol J., Lemoine J., Hondermarck H. (2007) Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 114–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Enomoto A., Murakami H., Asai N., Morone N., Watanabe T., Kawai K., Murakumo Y., Usukura J., Kaibuchi K., Takahashi M. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 389–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Higuchi M., Masuyama N., Fukui Y., Suzuki A., Gotoh Y. (2001) Curr. Biol. 11, 1958–1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stambolic V., Woodgett J. R. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16, 461–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhou G. L., Tucker D. F., Bae S. S., Bhatheja K., Birnbaum M. J., Field J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 36443–36453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ooms L. M., Horan K. A., Rahman P., Seaton G., Gurung R., Kethesparan D. S., Mitchell C. A. (2009) Biochem. J. 419, 29–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Maehama T., Taylor G. S., Dixon J. E. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 247–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mitchell C. A., Gurung R., Kong A. M., Dyson J. M., Tan A., Ooms L. M. (2002) IUBMB Life 53, 25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bielas S. L., Silhavy J. L., Brancati F., Kisseleva M. V., Al-Gazali L., Sztriha L., Bayoumi R. A., Zaki M. S., Abdel-Aleem A., Rosti R. O., Kayserili H., Swistun D., Scott L. C., Bertini E., Boltshauser E., Fazzi E., Travaglini L., Field S. J., Gayral S., Jacoby M., Schurmans S., Dallapiccola B., Majerus P. W., Valente E. M., Gleeson J. G. (2009) Nat. Genet. 41, 1032–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacoby M., Cox J. J., Gayral S., Hampshire D. J., Ayub M., Blockmans M., Pernot E., Kisseleva M. V., Compère P., Schiffmann S. N., Gergely F., Riley J. H., Pérez-Morga D., Woods C. G., Schurmans S. (2009) Nat. Genet. 41, 1027–1031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ijuin T., Mochizuki Y., Fukami K., Funaki M., Asano T., Takenawa T. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 10870–10875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ijuin T., Takenawa T. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1209–1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ijuin T., Yu Y. E., Mizutani K., Pao A., Tateya S., Tamori Y., Bradley A., Takenawa T. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 5184–5195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nishio M., Watanabe K., Sasaki J., Taya C., Takasuga S., Iizuka R., Balla T., Yamazaki M., Watanabe H., Itoh R., Kuroda S., Horie Y., Förster I., Mak T. W., Yonekawa H., Penninger J. M., Kanaho Y., Suzuki A., Sasaki T. (2007) Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dyson J. M., O'Malley C. J., Becanovic J., Munday A. D., Berndt M. C., Coghill I. D., Nandurkar H. H., Ooms L. M., Mitchell C. A. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 1065–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Prasad N., Topping R. S., Decker S. J. (2001) Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1416–1428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Prasad N., Topping R. S., Decker S. J. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 3807–3815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kabbage M., Dickman M. B. (2008) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 65, 1390–1402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bardelli A., Longati P., Albero D., Goruppi S., Schneider C., Ponzetto C., Comoglio P. M. (1996) EMBO J. 15, 6205–6212 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shatkina L., Mink S., Rogatsch H., Klocker H., Langer G., Nestl A., Cato A. C. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 7189–7197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takayama S., Xie Z., Reed J. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 781–786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jiang Y., Woronicz J. D., Liu W., Goeddel D. V. (1999) Science 283, 543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Antoku K., Maser R. S., Scully W. J., Jr., Delach S. M., Johnson D. E. (2001) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 286, 1003–1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cross M., Nguyen T., Bogdanoska V., Reynolds E., Hamilton J. A. (2005) Proteomics 5, 4754–4763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gurung R., Tan A., Ooms L. M., McGrath M. J., Huysmans R. D., Munday A. D., Prescott M., Whisstock J. C., Mitchell C. A. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11376–11385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ivetac I., Munday A. D., Kisseleva M. V., Zhang X. M., Luff S., Tiganis T., Whisstock J. C., Rowe T., Majerus P. W., Mitchell C. A. (2005) Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 2218–2233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Al-Lamki R. S., Wang J., Thiru S., Pritchard N. R., Bradley J. A., Pober J. S., Bradley J. R. (2003) Am. J. Pathol. 163, 401–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Todd I., Radford P. M., Draper-Morgan K. A., McIntosh R., Bainbridge S., Dickinson P., Jamhawi L., Sansaridis M., Huggins M. L., Tighe P. J., Powell R. J. (2004) Immunology 113, 65–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gastpar R., Gehrmann M., Bausero M. A., Asea A., Gross C., Schroeder J. A., Multhoff G. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 5238–5247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Shin H. W., Hayashi M., Christoforidis S., Lacas-Gervais S., Hoepfner S., Wenk M. R., Modregger J., Uttenweiler-Joseph S., Wilm M., Nystuen A., Frankel W. N., Solimena M., De Camilli P., Zerial M. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 170, 607–618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Onnockx S., De Schutter J., Blockmans M., Xie J., Jacobs C., Vanderwinden J. M., Erneux C., Pirson I. (2008) J. Cell. Physiol. 214, 260–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kisseleva M. V., Wilson M. P., Majerus P. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20110–20116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oatey P. B., Venkateswarlu K., Williams A. G., Fletcher L. M., Foulstone E. J., Cullen P. J., Tavaré J. M. (1999) Biochem. J. 344, 511–518 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alessi D. R., James S. R., Downes C. P., Holmes A. B., Gaffney P. R., Reese C. B., Cohen P. (1997) Curr. Biol. 7, 261–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sarbassov D. D., Guertin D. A., Ali S. M., Sabatini D. M. (2005) Science 307, 1098–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Song G., Ouyang G., Bao S. (2005) J. Cell Mol. Med. 9, 59–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Woods Y. L., Rena G. (2002) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 30, 391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Takada H., Chen N. J., Mirtsos C., Suzuki S., Suzuki N., Wakeham A., Mak T. W., Yeh W. C. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 4026–4033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Endres R., Häcker G., Brosch I., Pfeffer K. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 6609–6617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Charest P. G., Firtel R. A. (2007) Biochem. J. 401, 377–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kölsch V., Charest P. G., Firtel R. A. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 551–559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. McKenna L. B., Zhou G. L., Field J. (2007) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 64, 2723–2725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Irie H. Y., Pearline R. V., Grueneberg D., Hsia M., Ravichandran P., Kothari N., Natesan S., Brugge J. S. (2005) J. Cell Biol. 171, 1023–1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cramer L. P., Briggs L. J., Dawe H. R. (2002) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 51, 27–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Affolter M., Weijer C. J. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 19–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Li J., Ballif B. A., Powelka A. M., Dai J., Gygi S. P., Hsu V. W. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 663–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zhou G. L., Zhuo Y., King C. C., Fryer B. H., Bokoch G. M., Field J. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 8058–8069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cheng H. L., Steinway M., Delaney C. L., Franke T. F., Feldman E. L. (2000) Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 170, 211–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Costa C., Barberis L., Ambrogio C., Manazza A. D., Patrucco E., Azzolino O., Neilsen P. O., Ciraolo E., Altruda F., Prestwich G. D., Chiarle R., Wymann M., Ridley A., Hirsch E. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14354–14359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. D'Souza-Schorey C., Chavrier P. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 347–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Jackson T. R., Kearns B. G., Theibert A. B. (2000) Trends Biochem. Sci. 25, 489–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Donaldson J. G. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41573–41576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Frank S., Upender S., Hansen S. H., Casanova J. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 23–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hawthorne V. S., Yu D. (2004) Cancer Biol. Ther. 3, 776–777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Paez J., Sellers W. R. (2003) Cancer Treat. Res. 115, 145–167 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ozawa F., Friess H., Zimmermann A., Kleeff J., Büchler M. W. (2000) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 271, 409–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Bondar V. M., Sweeney-Gotsch B., Andreeff M., Mills G. B., McConkey D. J. (2002) Mol. Cancer Ther. 1, 989–997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tao H., Hu Q., Fang J., Liu A., Liu S., Zhang L., Hu Y. (2007) J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technolog. Med. Sci. 27, 326–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.