Abstract

Decreased dilation of cerebral arterioles via an increase in oxidative stress may be a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of diabetes-induced complications leading to cognitive dysfunction and/or stroke. Our goal was to determine whether resveratrol, a polyphenolic compound present in red wine, has a protective effect on cerebral arterioles during type 1 diabetes (T1D). We measured the responses of cerebral arterioles in untreated and resveratrol-treated (10 mg·kg−1·day−1) nondiabetic and diabetic rats to endothelial (eNOS) and neuronal (nNOS) nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-dependent agonists and to a NOS-independent agonist. In addition, we harvested brain tissue from nondiabetic and diabetic rats to measure levels of superoxide under basal conditions. Furthermore, we used Western blot analysis to determine the protein expression of eNOS, nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 in cerebral arterioles and/or brain tissue from untreated and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic and diabetic rats. We found that T1D impaired eNOS- and nNOS-dependent reactivity of cerebral arterioles but did not alter NOS-independent vasodilation. While resveratrol did not alter responses in nondiabetic rats, resveratrol prevented T1D-induced impairment in eNOS- and nNOS-dependent vasodilation. In addition, superoxide levels were higher in brain tissue from diabetic rats and resveratrol reversed this increase. Furthermore, eNOS and nNOS protein were increased in diabetic rats and resveratrol produced a further increased eNOS and nNOS proteins. SOD-1 and SOD-2 proteins were not altered by T1D, but resveratrol treatment produced a decrease in SOD-2 protein. Our findings suggest that resveratrol restores vascular function and oxidative stress in T1D. We suggest that our findings may implicate an important therapeutic potential for resveratrol in treating T1D-induced cerebrovascular dysfunction.

Keywords: brain, N-methyl-d-aspartic acid, adenosine 5′-diphosphate, nitroglycerin, oxidative stress, superoxide

cerebral vascular disease leading to cognitive dysfunction and/or stroke is a complication of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The risk of stroke is significantly higher in patients with diabetes than in persons without, and the mortality following a stroke is significantly higher in patients with diabetes compared with those without (4, 25, 37). Endothelial dysfunction appears to play an important role in the pathogenesis of vascular abnormalities during many disease states, including type 1 and type 2 diabetes (12, 21, 26, 39, 42). Many studies have shown that type 1 diabetes (T1D) affects endothelial cell function of large peripheral vessels by influencing the generation of nitric oxide via nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and/or via the formation of reactive oxygen species (11, 23, 36, 38, 40). In addition, we have shown that responses of cerebral resistance arterioles to endothelial NOS (eNOS)- and neuronal NOS (nNOS)-dependent agonists are decreased during T1D, presumably via an increase in oxidative stress (28, 32, 48). Thus, since cerebral blood flow is tightly coupled to metabolism and since eNOS- and nNOS-dependent vasodilation are important networks that regulate cerebral blood flow, it is critical to determine factors that may influence vascular function/dysfunction during T1D. An understanding regarding the regulation of cerebral blood flow/cerebrovascular reactivity during T1D may provide insights into the mechanisms that contribute to cognitive dysfunction and/or stroke observed in patients with T1D.

Resveratrol (3,4′,5-trihydroxystilbene) is found in many dietary plants, and it is a phytoalexin present in grapes and red wines. Resveratrol has been reported to have a variety of pharmacological effects, including anti-inflammatory, anticarcinogenic, antioxidant, and antiplatelet properties (5, 6, 20, 24, 45, 55, 58). Several investigators have shown that resveratrol has both acute and chronic influences on organ systems (7, 8, 45, 53) and endothelial function of large peripheral blood vessels during T1D (41, 44). The mechanisms that account for the effects of resveratrol on vascular function are varied but appear to involve an increase in the expression of eNOS, an increase in the expression of antioxidant pathways and pathways that might regulate antioxidant responses in cells (including SIRT1 and Nrf2), and/or a decrease in the expression of endothelin (13, 22, 41, 44, 47, 53, 58). Thus resveratrol can limit oxidative stress and restore nitric oxide bioavailability to preserve NOS-dependent reactivity of large peripheral blood vessels. However, to our knowledge, no studies have examined the influence of resveratrol on eNOS- and nNOS-dependent responses of cerebral resistance arterioles, arterioles that directly regulate cerebral blood flow. Thus the present study was designed to test the hypothesis that resveratrol can restore impaired responses of cerebral arterioles via its influence on nitric oxide and/or oxidant/antioxidant pathways. To test this hypothesis, we had three goals. Our first goal was to determine whether chronic treatment with resveratrol could influence eNOS- and nNOS-dependent responses of cerebral arterioles in nondiabetic and diabetic rats. To accomplish this goal, we measured in vivo responses of cerebral (pial) resistance arterioles to eNOS- and nNOS-dependent agonists in control nondiabetic and diabetic rats and in resveratrol-treated nondiabetic and diabetic rats. Our second goal was to determine the influence of resveratrol on superoxide levels in brain tissue during T1D. To accomplish this goal, we used lucigenin chemiluminescence to measure superoxide levels in cortex tissue in control nondiabetic and diabetic rats and in resveratrol-treated nondiabetic and diabetic rats. Our third goal was to determine the influence of resveratrol on the protein expression of several key enzymes in the brain. To accomplish this goal, we used Western blot analysis to measure the expression of eNOS, nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 in isolated cerebral arterioles and/or brain tissue from control nondiabetic and diabetic rats and from resveratrol-treated nondiabetic and diabetic rats.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of animals.

All rats were housed in an animal care facility that is approved by the American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, and all protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male Sprague-Dawley rats (200–220 g body wt) were randomly assigned to a nondiabetic group that was injected with vehicle (sodium citrate buffer) or a diabetic group that was injected with streptozotocin (50 mg/kg ip). Blood glucose concentration was measured 3 days after injection of streptozotocin or vehicle. A blood glucose concentration of ≥300 mg/dl was considered diabetic. The nondiabetic group was further divided into a control nondiabetic group and a resveratrol-treated nondiabetic group. The diabetic group was also further divided into a control diabetic group and a resveratrol-treated diabetic group. Resveratrol (10 mg·kg−1·day−1) was administered in the drinking water, and the treatment with resveratrol was started 3 days after injection with vehicle or streptozotocin. On the day of the experiment (4–6 wk after injection of vehicle or streptozotocin), rats were anesthetized with thiobutabarbital sodium (Inactin; 100 mg/kg body wt ip) and a tracheotomy was performed. The rats were mechanically ventilated with room air and supplemental oxygen. A catheter was placed in a femoral vein for infusion of supplemental anesthetic (10–20 mg/kg, as needed), and a femoral artery was cannulated to measure arterial blood pressure, to obtain a blood sample for the measurement of blood glucose concentration, and for the measurement of arterial pH, Pco2, and Po2.

To visualize the microcirculation of the cerebrum, a craniotomy was prepared over the left parietal cortex (33). The cranial window was suffused with artificial cerebral spinal fluid (flow rate = 2 ml/min) that was bubbled continuously (95% nitrogen and 5% carbon dioxide). The temperature of the suffusate was maintained at 37 ± 1°C. The cranial window was connected via a three-way valve to an infusion pump that allowed infusion of agents into the suffusate and thus onto the cerebral microcirculation. This method, which we have previously used (29, 31), maintained a constant temperature, pH, Pco2, and Po2 of the suffusate during infusion of agents.

Measurement of pial arteriolar reactivity.

The in vivo diameter of pial arterioles was measured using a video image-shearing device (model 908, Instrumentation for Physiology and Medicine). We examined the reactivity of the largest arteriole exposed by the craniotomy. The cranial window was suffused for 30–45 min before testing responses to the agonists. We then examined responses of pial arterioles in control nondiabetic (n = 11), resveratrol-treated nondiabetic (n = 8), diabetic (n = 8), and resveratrol-treated diabetic (n = 8) rats to an eNOS-dependent agonist 5′-adenosine diphosphate (ADP; 10 and 100 μM), an nNOS-dependent agonist N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA; 100 and 300 μM), and to a NOS-independent agonist nitroglycerin (1.0 and 10 μM). The diameter of arterioles was measured immediately before the application of agonists and every minute during a 5-min application period. After the application of the agonist was stopped, the diameter of pial arterioles returned to baseline within 3–5 min. The agonists were mixed in artificial cerebral spinal fluid and then superfused over the cerebral microcirculation in a random manner. The application of each dose of agonist was separated by a 5-min period, and the application of different agonists was separated by a 10-min period.

Superoxide levels.

In groups of control nondiabetic (n = 15), control diabetic (n = 13), resveratrol-treated nondiabetic (n = 10), and resveratrol-treated diabetic (n = 15) rats, we measured superoxide levels using lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence (1). Rats were anesthetized and exsanguinated, and the brain was then removed and immersed in a modified Krebs-HEPES buffer containing (in mmol/l) 118 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.3 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.2 KH2PO4, 25 NaHCO3, 10 HEPES, and 5 glucose (20 glucose for brains from control and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats) (pH 7.4). Tissue samples from the parietal cortex were placed in polypropylene tubes containing 5 μmol/l lucigenin and then read in a Fentomaster FB12 (Zytox) luminometer, which reports relative light units emitted, integrated over 30-s intervals for 5 min. Data were corrected for background activity and normalized to tissue weight. In these studies, we measured superoxide levels under basal conditions.

Western blot analysis.

In separate groups of control and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic and diabetic rats (n = 5 for each group), we measured eNOS, nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 proteins in isolated cerebral arterioles (eNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2) and cortex tissue (nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2). We also used Western blot analysis to measure the protein expression of GAPDH, and the values for eNOS, nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 proteins were normalized to GAPDH. Cerebral arterioles were isolated from brain tissue using methods previously described (49). Samples were homogenized in 20% (wt/vol) ice-cold buffer containing 10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 1% SDS, 1 mM sodium vanadate, 10 μg/ml aprotinine, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. The homogenates were centrifuged at 12,000 g for 20 min at 4°C, and the protein concentrations in the supernatant were determined by the Bradford method (Bio-Rad; Richmond, CA) with BSA as the standard. The protein was mixed and boiled in SDS-PAGE sample buffer for 5 min and then loaded and run on standard 7.5% or 12% gels. After SDS-PAGE, the proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Immunoblotting was performed using the appropriate primary and secondary antibodies for eNOS, nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The bound antibody was detected using an ECL kit and quantified by scanning densitometry.

Statistical analysis.

Analysis of variance with Fischer least significant difference test for significance was used to compare baseline parameters, functional responses of cerebral arterioles, basal superoxide levels, and protein densitometry between the various groups of rats. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Control conditions.

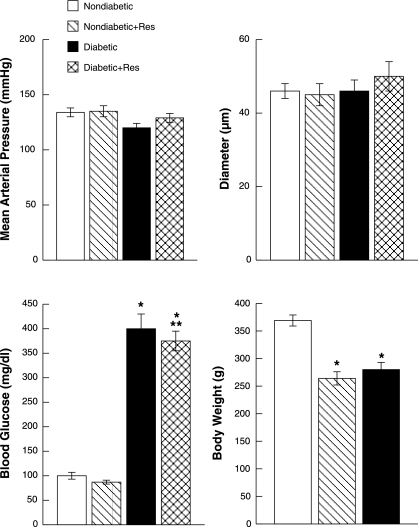

There were no significant differences in mean arterial pressure or baseline diameter of pial arterioles between control and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic and diabetic rats (Fig. 1). However, blood glucose concentration was significantly higher in diabetic and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats than in nondiabetic and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats. In addition, resveratrol treatment produced a small, but significant, decrease in blood glucose concentration in diabetic rats compared with untreated diabetic rats. There was no difference in blood glucose concentration between nondiabetic and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats. Body weight was significantly lower in diabetic and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats compared with nondiabetic and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats (Fig. 1). Resveratrol treatment did not influence body weight within groups of nondiabetic and diabetic rats.

Fig. 1.

Mean arterial blood pressure, baseline diameter of pial arterioles, blood glucose concentration, and body weight in nondiabetic, resveratrol (Res)-treated nondiabetic, diabetic, and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. nondiabetic rats; **P < 0.05 vs. diabetic rats.

Responses to the agonists.

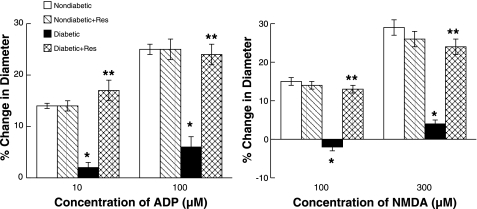

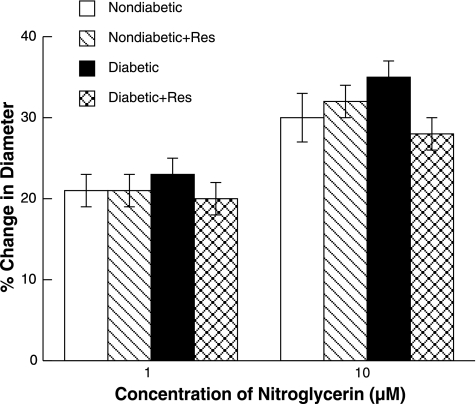

ADP, NMDA, and nitroglycerin produced dilation of pial arterioles in control and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic and diabetic rats (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively). However, the magnitude of vasodilation in response to ADP and NMDA (Fig. 2) was greater in control and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats than in control diabetic rats. Dilation of pial arterioles in response to ADP and NMDA was restored by resveratrol treatment in diabetic rats to that observed in control and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats. Dilation of pial arterioles in response to nitroglycerin (Fig. 3) was similar in all groups of rats. Thus resveratrol treatment does not influence eNOS- and nNOS-dependent responses of cerebral arterioles in nondiabetic rats but restores cerebrovascular dysfunction in diabetic rats.

Fig. 2.

Responses of pial arterioles to ADP and N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) in nondiabetic, resveratrol-treated nondiabetic, diabetic, and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. response in control nondiabetic rats; **P < 0.05 vs. response in control diabetic rats.

Fig. 3.

Responses of pial arterioles to nitroglycerin in nondiabetic, resveratrol-treated nondiabetic, diabetic, and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats. Values are means ± SE.

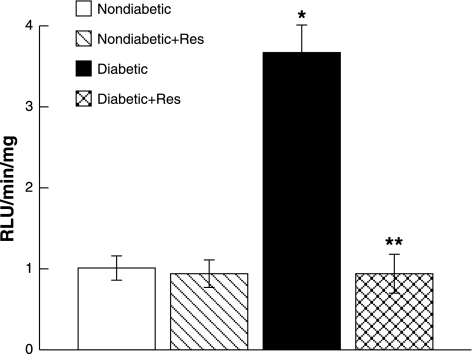

Superoxide levels.

In nondiabetic rats, basal levels of superoxide in parietal cortex tissue were not influenced by chronic resveratrol treatment (Fig. 4). In contrast, basal superoxide levels were increased in parietal cortex samples obtained from control diabetic rats compared with control and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats. In addition, treatment with resveratrol restored superoxide levels in cortex tissue in diabetic rats to levels observed in control and resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats.

Fig. 4.

Superoxide production by parietal cortex tissue in nondiabetic, resveratrol-treated nondiabetic, diabetic, and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats under basal conditions. Values are means ± SE. RLU, relative light units. *P < 0.05 vs. control nondiabetic rats; **P < 0.05 vs. diabetic rats.

Western blot analysis.

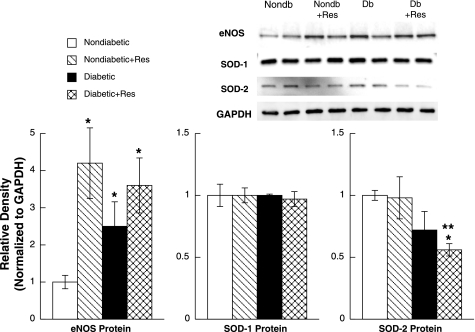

First, we examined eNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 protein levels in isolated cerebral arterioles in the four groups of rats (Fig. 5). We found that eNOS protein was elevated by resveratrol in nondiabetic rats, elevated in diabetic rats, and elevated in diabetic rats treated with resveratrol. However, the increase in eNOS protein in diabetic rats treated with resveratrol was not significantly different than that observed in diabetic rats. SOD-1 protein was not altered by T1D or treatment with resveratrol. SOD-2 protein expression was similar in nondiabetic rats and nondiabetic rats treated with resveratrol. Although SOD-2 protein expression tended to be less in diabetic rats compared with nondiabetic rats, it did not reach statistical significance (P < 0.10). However, SOD-2 protein level was significantly decreased in diabetic rats treated with resveratrol compared with nondiabetic rats and in nondiabetic rats treated with resveratrol but not diabetic rats. Thus T1D and treatment of nondiabetic rats with resveratrol produce an increase in eNOS protein expression, there is no change in SOD-1 protein expression by resveratrol or T1D, and resveratrol treatment decreases SOD-2 protein expression in diabetic rats compared with nondiabetic rats and nondiabetic rats treated with resveratrol.

Fig. 5.

Western blot of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), SOD-1, and SOD-2 proteins from cerebral microvessels from nondiabetic (Nondb), resveratrol-treated nondiabetic, diabetic (Db), and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats. Protein levels for eNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 are normalized to GAPDH. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. control nondiabetic rats; **P < 0.05 vs. resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats.

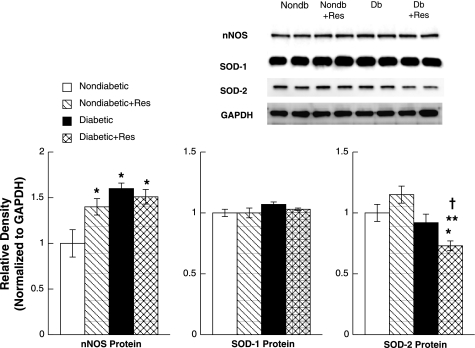

Second, we examined nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 protein levels in parietal cortex tissue in the four groups of rats (Fig. 6). We found that nNOS protein was increased by resveratrol treatment in nondiabetic rats, was increased in control diabetic rats, and was increased in diabetic rats treated with resveratrol compared with control nondiabetic rats. However, the increase in nNOS protein in diabetic rats treated with resveratrol was not significantly different than that observed in diabetic rats. Similar to our findings using cerebral arterioles, we did not find a difference in SOD-1 protein expression between the various groups of rats. We found that SOD-2 protein expression was similar in nondiabetic rats, nondiabetic rats treated with resveratrol, and diabetic rats. However, SOD-2 protein expression was significantly decreased in diabetic rats treated with resveratrol compared with the other groups of rats. Thus T1D and treatment of nondiabetic rats with resveratrol produce an increase in nNOS protein expression, there is no change in SOD-1 protein expression by resveratrol treatment or T1D, and resveratrol treatment decreases SOD-2 protein expression in parietal cortex tissue in diabetic rats compared with nondiabetic rats.

Fig. 6.

Western blot of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), SOD-1, and SOD-2 proteins from brain tissue from nondiabetic, resveratrol-treated nondiabetic, diabetic, and resveratrol-treated diabetic rats. Protein levels for nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 are normalized to GAPDH. Values are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. control nondiabetic rats; **P < 0.05 vs. resveratrol-treated nondiabetic rats; †P < 0.05 vs. diabetic rats.

DISCUSSION

There are three new findings from this study. First, impaired eNOS- and nNOS-dependent dilation of cerebral arterioles in diabetic rats can be restored to that observed in nondiabetic rats by treatment with resveratrol. This finding cannot be explained by a nonspecific effect of resveratrol on vascular function since responses to nitroglycerin were not altered by treatment with resveratrol. Second, the levels of superoxide were increased in parietal cortex tissue from diabetic rats and treatment with resveratrol reversed this increase. Third, treatment with resveratrol produced an increase in the expression of eNOS and nNOS proteins in cerebral arterioles and parietal cortex tissue in nondiabetic, but not diabetic, rats; did not influence the expression of SOD-1 protein in cerebral arterioles or parietal cortex tissue; and did not alter the expression of SOD-2 protein in cerebral arterioles or parietal cortex tissue nondiabetic rats but decreased the expression of SOD-2 protein in cerebral arterioles and parietal cortex tissue in diabetic rats. We suggest that resveratrol prevents T1D-induced impairment in cerebrovascular reactivity by the attenuation of oxidative stress and the preservation of eNOS and nNOS protein expression. We speculate that resveratrol may be a potential therapeutic treatment for the prevention of cerebrovascular dysfunction during T1D.

We used ADP and NMDA to examine eNOS- and nNOS-dependent responses of cerebral arterioles, respectively. ADP appears to dilate cerebral arterioles via the activation of NOS, presumably eNOS (3, 15, 30). However, some have suggested that relaxation of the rat middle cerebral artery to purines is related, in part, to the synthesis/release of nitric oxide and to synthesis/release of an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF) (27, 56). We did not examine a role for EDHF in response to ADP in the present study, but studies by other investigators (9, 10, 16, 19, 51) have suggested that the activation of potassium channels, presumably by EDHF, does not play a significant role in the dilatation of cerebral arterioles to the agonists used in the present study.

Regarding responses to NMDA, we and others have shown that NMDA dilates cerebral arterioles via the activation of nNOS and the subsequent synthesis/release of nitric oxide (16–18, 50). Since NMDA activates glutamate receptor subtypes to produce dilation of cerebral blood vessels and increases in cerebral blood flow, our finding that T1D impairs responses of cerebral arterioles to NMDA may have major clinical significance. Although diabetes leads to cognitive impairment (2, 35), the mechanisms responsible for this are not certain. It appears that disorders of the macro- and microcirculations may play an important role in the development of cognitive decline, dementia, and alterations in the blood-brain barrier. Thus altered vascular function may be a key predictor in the development of cognitive decline observed in humans with diabetes. An understanding of the coupling between cerebral blood vessels, neurons, and astrocytes, i.e., neurovascular coupling, appears to be a critical step in the treatment of altered brain function during disease states, including diabetes.

Several studies have reported that resveratrol produces a decrease in blood glucose concentration in diabetic rats (44, 46, 53). In the present study we also found a small, but significant, decrease in blood glucose concentration in rats treated with resveratrol. The mechanism for the effect of resveratrol on blood glucose concentration is unknown. It is conceivable that this small change in blood glucose concentration by resveratrol could contribute to the improvement in eNOS- and nNOS-dependent responses of cerebral arterioles in the diabetic rats. However, this possibility seems unlikely since blood glucose concentration was still dramatically elevated in resveratrol-treated diabetic rats. Thus, although we cannot completely rule out an effect of this small decrease in blood glucose concentration by resveratrol on cerebrovascular reactivity, we suggest that the beneficial effects of resveratrol are related to its influence on oxidative stress.

Several studies have examined the effects of resveratrol on peripheral organ systems and have reported that resveratrol can provide protection to the heart (8, 53) and kidney (7, 43, 52) and may inhibit carcinogenesis (24, 34). In addition, others have reported that resveratrol may play a beneficial role in impaired vascular function of large peripheral blood vessels during type 1 (41, 44) and type 2 (57) diabetes. Silan (44) reported that treatment of diabetic rats with resveratrol prevented impaired relaxation of the aorta to acetylcholine, presumably via its influence on oxidative stress. Roghani and Baluchnejadmojarad (41) also found that chronic resveratrol treatment prevented T1D-induced impairment in relaxation of the thoracic aorta in rats. These investigators (41) suggested that the mechanism for the effect of resveratrol was probably related to its hypoglycemic, hypolipidemic, and/or antioxidant properties. Thus resveratrol appears to limit oxidative stress, to restore nitric oxide bioavailability, and to preserve NOS-dependent reactivity of large peripheral blood vessels. In addition, others (14, 20, 57) have suggested that resveratrol has significant anti-inflammatory effects. Since diabetes may increase proinflammatory agents, such as TNF-α, it is possible that resveratrol may decrease the activity of proinflammatory pathways to influence vascular function. Support for this concept can be found in a recent study (57) that reported that resveratrol inhibited TNF-α-induced activation of NADPH oxidase and improved endothelial function. The results of the present study complement and extend previous findings. We found that treatment with resveratrol prevented T1D-induced impairment of cerebral resistance arterioles. The mechanism for the effect of resveratrol on cerebrovascular dysfunction during T1D appears to be related to a decrease in oxidative stress; however, the precise cellular pathway remains uncertain.

Others have examined the molecular mechanisms that might explain the beneficial effects of resveratrol on vascular function. These mechanisms vary but appear to involve an increase in the expression of eNOS, an increase in the expression of antioxidant pathways and pathways that might regulate antioxidant responses in cells (including SIRT1 and Nrf2), and/or a decrease in the expression of endothelin (13, 22, 41, 44, 47, 53, 58). It was beyond the scope of the present study to examine all such possibilities in the cerebral microcirculation, but we did investigate the influence of resveratrol on eNOS, nNOS, SOD-1, and SOD-2 protein levels in cerebral arterioles and brain tissue. We found that eNOS and nNOS proteins were elevated in nondiabetic rats treated with resveratrol. eNOS and nNOS proteins were also increased in diabetic rats, but treatment with resveratrol did not produce a further increase in these proteins in diabetic rats even though vascular function was restored by resveratrol treatment. This was somewhat surprising, but given that eNOS and nNOS proteins were already elevated during T1D and that resveratrol significantly decreased superoxide levels, we suggest that altered vascular function during T1D is probably not related to an alteration in eNOS or nNOS proteins/activities.

We also examined SOD-1 and SOD-2 protein levels in cerebral arterioles and brain tissue, respectively, in the various groups of rats. We found that SOD-1 and SOD-2 proteins were not altered in diabetic rats compared with nondiabetic rats in cerebral arterioles or brain tissue. In addition, we found that resveratrol treatment did not alter SOD-1 or SOD-2 proteins from cerebral arterioles or brain tissue in nondiabetic rats, did not alter SOD-1 protein from cerebral arterioles or brain tissue in diabetic rats, but produced a decrease in SOD-2 protein from cerebral arterioles (when compared with nondiabetic and nondiabetic resveratrol treated) and a decrease in SOD-2 protein from brain tissue (when compared with nondiabetic, nondiabetic resveratrol treated, and diabetic) in diabetic resveratrol-treated rats. These findings were somewhat surprising given that a previous study reported an increase in MnSOD (SOD-2) in coronary endothelial cells following treatment with resveratrol (54). We speculated that SOD-1 and SOD-2 proteins might be elevated in diabetic rats as a compensatory response to an increase in oxidative stress in the brain during T1D. However, we did not find this. This might help explain why we observed an increase in superoxide levels in diabetic rats, i.e., an apparent dissociation between an increase in oxidant stress and antioxidant protective mechanisms. We also speculated that resveratrol might produce a further increase in SOD-1 and/or SOD-2 proteins to combat increases in oxidative stress during T1D. But, we did not find an effect of resveratrol on SOD-1 and resveratrol decreased SOD-2 protein in diabetic rats. It is conceivable that treatment with resveratrol effectively suppressed superoxide levels from mitochondria in diabetic rats to a point that there was a compensatory decrease in this antioxidant pathway. It is also possible that resveratrol decreased the numbers of mitochondria in diabetic rats, thus decreasing the amount of superoxide produced. Although we cannot directly determine the precise mechanism for the effects of resveratrol on SOD-2 protein, it appears that resveratrol is able to combat increases in oxidative stress in diabetic rats and reverse cerebrovascular dysfunction, given that superoxide levels from brain tissue were decreased in diabetic resveratrol-treated rats.

In summary, we found that treatment of diabetic rats with resveratrol could prevent T1D-induced impairment in eNOS- and nNOS-dependent responses of cerebral arterioles. In addition, we found that the increase in basal levels of superoxide anion observed during T1D could be prevented by resveratrol. Although there are some limitations to our study to prevent a direct translation to clinical medicine (limited oral absorption of resveratrol in humans and/or the study of resveratrol in an artificial environment), we suggest that resveratrol may be a potential therapeutic agent for the prevention of T1D-induced cerebrovascular dysfunction.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-090657 and AA-11288.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Arrick DM, Sharpe GM, Sun H, Mayhan WG. Diabetes-induced cerebrovascular dysfunction: role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Microvasc Res 73: 1–6, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Arvanitakis Z, Wilson RS, Bienias JL, Evans DA, Bennett DA. Diabetes mellitus and risk of Alzheimer disease and decline in cognitive function. Arch Neurol 61: 661–666, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ayajiki K, Okamura T, Toda N. Involvement of nitric oxide in endothelium-dependent, phasic relaxation caused by histamine in monkey cerebral arteries. Jpn J Pharmacol 60: 357–362, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baird TA, Parsons MW, Barber PA, Butcher KS, Desmond PM, Tress BM, Colman PG, Jerums G, Chambers BR, Davis SM. The influence of diabetes mellitus and hyperglycaemia on stroke incidence and outcome. J Clin Neurosci 9: 618–626, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bertelli AA, Giovannini L, Bernini W, Migliori M, Fregoni M, Bavaresco L, Bertelli A. Antiplatelet activity of cis-resveratrol. Drugs Exp Clin Res 22: 61–63, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bertelli AA, Giovannini L, Giannessi D, Migliori M, Bernini W, Fregoni M, Bertelli A. Antiplatelet activity of synthetic and natural resveratrol in red wine. Int J Tissue React 17: 1–3, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bertelli AA, Migliori M, Panichi V, Origlia N, Filippi C, Das DK, Giovannini L. Resveratrol, a component of wine and grapes, in the prevention of kidney disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 957: 230–238, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bradamante S, Barenghi L, Piccinini F, Bertelli AA, De Jonge R, Beemster P, De Jong JW. Resveratrol provides late-phase cardioprotection by means of a nitric oxide- and adenosine-mediated mechanism. Eur J Pharmacol 465: 115–123, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brayden JE. Hyperpolarization and relaxation of resistance arteries in response to adenosine diphosphate. Circ Res 69: 1415–1420, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chrissobolis S, Ziogas J, Chu Y, Faraci FM, Sobey CG. Role of inwardly rectifying K+ channels in K+-induced cerebral vasodilatation in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 279: H2704–H2712, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coppey LJ, Gellett JS, Davidson EP, Yorek MA. Preventing superoxide formation in epineurial arterioles of the sciatic nerve from diabetic rats restores endothelium-dependent vasodilation. Free Radic Res 37: 33–40, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Creager MA, Luscher TF, Cosentino F, Beckman JA. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part I. Circulation 108: 1527–1532, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Pinto JT, Ballabh P, Zhang H, Losonczy G, Pearson K, de Cabo R, Pacher P, Zhang C, Ungvari Z. Resveratrol induces mitochondrial biogenesis in endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H13–H20, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Das S, Das DK. Anti-inflammatory responses of resveratrol. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 6: 168–173, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Faraci FM. Role of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in cerebral circulation: Large arteries vs. microcirculation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1038–H1042, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Faraci FM, Breese KR. Nitric oxide mediates vasodilatation in response to activation of N-methyl-d-aspartate receptors in brain. Circ Res 72: 476–480, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Faraci FM, Breese KR, Heistad DD. Responses of cerebral arterioles to kainate. Stroke 25: 2080–2084, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Faraci FM, Brian JE. 7-Nitroindazole inhibits brain nitric oxide synthase and cerebral vasodilatation in response to N-methyl-d-aspartate. Stroke 26: 2172–2176, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Role of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in the basilar artery. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H8–H13, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fulgenzi A, Bertelli AA, Magni E, Ferrero E, Ferrero ME. In vivo inhibition of TNFalpha-induced vascular permeability by resveratrol. Transplant Proc 33: 2341–2343, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hadi HA, Suwaidi JA. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. Vasc Health Risk Manag 3: 853–876, 2007 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hasko G, Pacher P. Endothelial Nrf2 activation: a new target for resveratrol? Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H10–H12, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hattori Y, Kawasaki H, Abe K, Kanno M. Superoxide dismutase recovers altered endothelium-dependent relaxation in diabetic rat aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 261: H1086–H1094, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ho SM. Estrogens and anti-estrogens: key mediators of prostate carcinogenesis and new therapeutic candidates. J Cell Biochem 91: 491–503, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Laing SP, Swerdlow AJ, Carpenter LM, Slater SD, Burden AC, Botha JL, Morris AD, Waugh NR, Gatling W, Gale EA, Patterson CC, Qiao Z, Keen H. Mortality from cerebrovascular disease in a cohort of 23 000 patients with insulin-treated diabetes. Stroke 34: 418–421, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Luscher TF, Creager MA, Beckman JA, Cosentino F. Diabetes and vascular disease: pathophysiology, clinical consequences, and medical therapy: Part II. Circulation 108: 1655–1661, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Marrelli SP, Khorovets A, Johnson TD, Childres WF, Bryan RM., Jr P2 purinoceptor-mediated dilations in the rat middle cerebral artery after ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 276: H33–H41, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mayhan WG, Arrick DM, Sharpe GM, Patel KP, Sun H. Inhibition of NAD(P)H oxidase alleviates impaired NOS-dependent responses of pial arterioles in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Microcirculation 13: 567–575, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Mayhan WG. Impairment of endothelium-dependent dilatation of cerebral arterioles during diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 256: H621–H625, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mayhan WG. Endothelium-dependent responses of cerebral arterioles to adenosine 5′-diphosphate. J Vasc Res 29: 353–358, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mayhan WG. Impairment of endothelium-dependent dilatation of the basilar artery during diabetes mellitus. Brain Res 580: 297–302, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mayhan WG. Superoxide dismutase partially restores impaired dilatation of the basilar artery during diabetes mellitus. Brain Res 760: 204–209, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mayhan WG, Heistad DD. Permeability of blood-brain barrier to various sized molecules. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 248: H712–H718, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Meeran SM, Katiyar SK. Cell cycle control as a basis for cancer chemoprevention through dietary agents. Front Biosci 13: 2191–2202, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mogi M, Horiuchi M. Neurovascular coupling in cognitive impairment associated with diabetes mellitus. Circ J 25: 1042–1048, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nassar T, Kadery B, Lotan C, Da'as N, Kleinman Y, Haj-Yehia A. Effects of the superoxide dismutase-mimetic compound tempol on endothelial dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol 436: 111–118, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Nesto RW. Correlation between cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus: current concepts. Am J Med 116, Suppl 5A: 11S–22S, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ohishi K, Carmines PK. Superoxide dismutase restores the influence of nitric oxide on renal arterioles in diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1559–1566, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Phillips SA, Sylvester FA, Frisbee JC. Oxidant stress and constrictor reactivity impair cerebral artery dilation in obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R522–R530, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pieper GM, Mei DA, Langenstroer P, O'Rourke ST. Bioassay of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in diabetic rat aorta. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 263: H676–H680, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roghani M, Baluchnejadmojarad T. Mechanisms underlying vascular effects of chronic resveratrol in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Phytother Res 10: 1–7, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schwaninger RM, Sun H, Mayhan WG. Impaired nitric oxide synthase-dependent dilatation of cerebral arterioles in type II diabetic rats. Life Sci 73: 3415–3425, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sharma S, Anjaneyulu M, Kulkarni SK, Chopra K. Resveratrol, a polyphenolic phytoalexin, attenuates diabetic nephropathy in rats. Pharmacology 76: 69–75, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Silan C. The effects of chronic resveratrol treatment on vascular responsiveness of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Biol Pharm Bull 31: 897–902, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Silan C, Uzun O, Comunoglu NU, Gokcen S, Bedirhan S, Cengiz M. Gentamicin-induced nephrotoxicity in rats ameliorated and healing effects of resveratrol. Biol Pharm Bull 30: 79–83, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Su HC, Hung LM, Chen JK. Resveratrol, a red wine antioxidant, possesses an insulin-like effect in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E1339–E1346, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Sulaiman M, Matta MJ, Sunderesan NR, Gupta MP, Periasamy M, Gupta M. Resveratrol, an activator of SIRT1, upregulates sarcoplasmic calcium ATPase and improves cardiac function in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 298: H833–H843, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sun H, Molacek E, Zheng H, Fang Q, Patel KP, Mayhan WG. Alcohol-induced impairment of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS)-dependent dilation of cerebral arterioles: role of NAD(P)H oxidase. J Mol Cell Cardiol 40: 321–328, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sun H, Zheng H, Molacek E, Fang Q, Patel KP, Mayhan WG. Role of NAD(P)H oxidase in alcohol-induced impairment of endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent dilation of cerebral arterioles. Stroke 37: 495–500, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sun H, Patel KP, Mayhan WG. Impairment of neuronal nitric oxide synthase-dependent dilatation of cerebral arterioles during chronic alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 26: 663–670, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Taguchi H, Heistad DD, Kitazono T, Faraci FM. Dilatation of cerebral arterioles in response to activation of adenylate cyclase is dependent on activation of Ca2+-dependent K+ channels. Circ Res 76: 1057–1062, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tarquini B, Perfetto F, Tarquini R, Cornelissen G, Halberg F. Endothelin-1's chronome indicates diabetic and vascular disease chronorisk. Peptides 18: 119–132, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Thirunavukkarasu M, Penumathsa SV, Koneru S, Juhasz B, Zhan L, Otani H, Bagchi D, Das DK, Maulik N. Resveratrol alleviates cardiac dysfunction in streptozotocin-induced diabetes: role of nitric oxide, thioredoxin, and heme oxygenase. Free Radic Biol Med 43: 720–729, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ungvari Z, Labinskyy N, Mukhopadhyay P, Pinto JT, Bagi Z, Ballabh P, Zhang C, Pacher P, Csiszar A. Resveratrol attenuates mitochondrial oxidative stress in coronary arterial endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1876–H1881, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vilar S, Quezada E, Santana L, Uriarte E, Yanez M, Fraiz N, Alcaide C, Cano E, Orallo F. Design, synthesis, and vasorelaxant and platelet antiaggregatory activities of coumarin-resveratrol hybrids. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 16: 257–261, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. You J, Johnson TD, Marrelli SP, Mombouli JV, Bryan RM. P2u receptor-mediated release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor/nitric oxide and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor from cerebrovascular endothelium in rats. Stroke 30: 1125–1133, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang H, Zhang J, Ungvari Z, Zhang C. Resveratrol improves endothelial function: role of TNFα and vascular oxidative stress. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29: 1164–1171, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Zini R, Morin C, Bertelli A, Bertelli AA, Tillement JP. Effects of resveratrol on the rat brain respiratory chain. Drugs Exp Clin Res 25: 87–97, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]