Abstract

Redox-active transition metal ions, such as iron and copper, may play an important role in vascular inflammation, which is an etiologic factor in atherosclerotic vascular diseases. In this study, we investigated whether tetrathiomolybdate (TTM), a highly specific copper chelator, can act as an anti-inflammatory agent, preventing lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory responses in vivo. Female C57BL/6N mice were daily gavaged with TTM (30 mg/kg body wt) or vehicle control. After 3 wk, animals were injected intraperitoneally with 50 μg LPS or saline buffer and killed 3 h later. Treatment with TTM reduced serum ceruloplasmin activity by 43%, a surrogate marker of bioavailable copper, in the absence of detectable hepatotoxicity. The concentrations of both copper and molybdenum increased in various tissues, whereas the copper-to-molybdenum ratio decreased, consistent with reduced copper bioavailability. TTM treatment did not have a significant effect on superoxide dismutase activity in heart and liver. Furthermore, TTM significantly inhibited LPS-induced inflammatory gene transcription in aorta and heart, including vascular and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, respectively), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (ANOVA, P < 0.05); consistently, protein levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and MCP-1 in heart were also significantly lower in TTM-treated animals. Similar inhibitory effects of TTM were observed on activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) in heart and lungs. Finally, TTM significantly inhibited LPS-induced increases of serum levels of soluble ICAM-1, MCP-1, and TNF-α (ANOVA, P < 0.05). These data indicate that copper chelation with TTM inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses in aorta and other tissues of mice, most likely by inhibiting activation of the redox-sensitive transcription factors, NF-κB and AP-1. Therefore, copper appears to play an important role in vascular inflammation, and TTM may have value as an anti-inflammatory or anti-atherogenic agent.

Keywords: tetrathiomolybdate, copper, endothelium, lipopolysaccharide, inflammation

adhesion of mononuclear leukocytes to the vascular endothelium is a critical event in the initiation and progression of atherosclerosis. After migrating across the endothelial monolayer, monocytes differentiate into macrophages and take up modified or aggregated lipoproteins, becoming “foam cells” and forming the atherosclerotic fatty streak deposit. Subsequently, inflammation spreads in the vascular wall, inducing smooth muscle cell proliferation and atheroma formation (43, 68).

Expression of adhesion molecules and chemokines by endothelial cells is required for monocyte recruitment to the vascular wall. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) are three well-studied inflammatory mediators involved in different stages of monocyte infiltration. ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 attract and bind circulating leukocytes from the bloodstream and stimulate their adhesion to endothelial cells, whereas the concentration gradient of MCP-1 attracts leukocytes to the subendothelial space of the arterial intima (7, 30). Genetically engineered mice lacking MCP-1 or its receptor have been shown to be protected from vascular lesion formation in several animal models of atherosclerosis (20, 29, 39).

Gene expression of cellular adhesion molecules and chemokines is upregulated by proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1, and by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) via activation of the redox-sensitive transcription factors, nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) (16, 23, 44, 56, 63, 72, 77). Recent evidence suggests that LPS and its receptor, toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), play important roles in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis (17, 22, 27, 59, 74, 78). Redox-active transition metal ions, such as iron and copper, also have been suggested to affect inflammatory gene expression via redox-sensitive cell signaling and transcription factor activation (6, 18, 38, 53, 67, 71, 80, 81). We have found that chelation of intracellular iron or copper strongly inhibits TNF-α-induced expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and MCP-1 in human aortic endothelial cells (84) and LPS-induced synthesis of TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-6 in human monocytic cells (unpublished data). Copper is known to stimulate proliferation and migration of human endothelial cells (32, 52), and copper deficiency has been shown to downregulate inflammatory responses and angiogenesis in mice (58, 62).

In the present study, we used tetrathiomolybdate (TTM), a specific and effective copper chelator, to lower copper status in mice. TTM was initially developed as a therapeutic agent to treat Wilson's disease, which is characterized by excessive copper accumulation in liver and brain (12, 13). While TTM has a good safety index, most of its toxicity in animals is due to copper deficiency that is easily reversible by acute copper supplementation (55). Daily treatment with TTM has been shown to safely reduce bioavailable copper in 2–4 wk in humans and mice, likely through formation of a high-affinity tripartite complex with copper and proteins (8, 15, 28, 55). A recent study revealed that TTM can specifically complex with copper and its chaperon, Atx1, and hence inhibit intracellular copper trafficking and synthesis of holo-cuproproteins (1). The TTM-copper-protein complex is primarily metabolized in the liver, and the metabolites are cleared through bile (34, 36, 51). When TTM is used therapeutically, serum ceruloplasmin, a copper-containing ferroxidase, is monitored as a surrogate marker of copper status (11). Serum or tissue concentrations of copper are not useful markers because the TTM-complexed copper is still detectable but not bioavailable; in contrast, ceruloplasmin is synthesized and secreted in the bloodstream by the liver in a manner that is dependent on the availability of copper (46). Accumulating evidence indicates that expression of several angiogenic, growth-promoting, and pro-inflammatory cytokines is inhibited by copper-lowering therapy with TTM through multiple mechanisms (62), including inhibition of NF-κB activation (61).

Therefore, it is possible that copper lowering with TTM could be of therapeutic value in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis by inhibiting expression of inflammatory mediators. In the current study, we determined whether TTM exerts anti-inflammatory effects in LPS-exposed mice, an established animal model of acute inflammation.

METHODS

Animals.

Female C57BL/6N mice at 11–12 wk of age weighing between 22 and 24 grams were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The animals were housed in pathogen-free conditions and a temperature- and humidity-controlled environment (12:12-h light-dark cycle) with unlimited access to tap water and food. Mice were initially fed with regular chow diet (Purina no. 5001 chow) and then switched to a diet with adequate copper (9 ppm) (TD.05254; Harlan Teklad, Madison, WI) 1 wk before the experiment was initiated. All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Oregon State University.

TTM and LPS treatments.

A solution of ammonium tetrathiomolybdate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was prepared by dissolving TTM in doubly distilled water at a concentration of 3 g/l. LPS (serotype 055:B5 from Escherichia coli; Sigma Aldrich) stock solutions were prepared in Hanks' buffered saline solution (HBSS). Mice (n = 20) were randomly divided into four experimental groups of equal size (n = 5): mice in the “control” or “LPS-treated” groups were gavaged daily with 0.2 ml water; mice in the “TTM-treated” or “LPS- plus TTM-treated” groups were gavaged daily with TTM (30 mg/kg body wt) in 0.2 ml water. On day 21, the control and TTM-treated groups received a single intraperitoneal injection of 0.2 ml HBSS. The LPS and the LPS- plus TTM-treated groups were given an intraperitoneal injection of LPS (50 μg) in 0.2 ml HBSS. Animals were killed 3 h after injection. Blood and tissues were collected for metal content quantification, total RNA preparation, and nuclear protein extraction. Serum samples were prepared and stored at −20°C until analysis. Portions of liver and kidney were submitted to the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Oregon State University within 3 h after animal death for histopathological analysis.

Serum alanine aminotransferase.

Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was measured using the liquid ALT Reagent Kit from Pointe Scientific (Canton, MI). The kinetic-type assay was performed using a Molecular Devices spectrum microplate reader, according to the manufacturer's instructions for the automated test procedure.

Serum ceruloplasmin.

Serum ceruloplasmin assays were performed based on its ferroxidase activity according to Schosinsky et al. (69). Briefly, the assay was conducted in a 96-well microplate. For each well, 10 μl serum, 60 μl 0.1 M sodium acetate, and 20 μl 2.5 mg/ml o-dianisidine were mixed and incubated at 37°C. Reactions were stopped by adding 170 μl of 18 N sulfuric acid at either 15 or 45 min of incubation. Absorption was measured at 540 nm using a Molecular Devices spectrum microplate reader. The 540-nm absorption value at the 15-min time point was used as baseline for subtraction from the 45-min value to calculate ceruloplasmin activity, which was expressed as micromole o-dianisidine oxidized per milliliter per minute.

Tissue copper, molybdenum, and iron.

Tissue copper, molybdenum, and iron were measured using Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). One percent nitric acid was used as diluent for all sample measurements. Mouse heart, lung, kidney, and liver tissues were weighed and digested using 50% nitric acid at 70°C overnight. Subsequently, the digested samples were diluted 200-fold for metal measurement. Serum samples were directly diluted 200-fold with 1% nitric acid. Metal ions were measured by a PQ ExCell ICP-MS detector from Thermo Elemental (Waltham, MA), and indium was used as an internal control. Copper, molybdenum, and iron standards were purchased from Ricca Chemical (Arlington, TX). Metal ion concentrations were expressed as milligram per gram wet tissue.

Serum concentrations of inflammatory mediators.

Serum levels of soluble VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 (sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1, respectively), MCP-1, IL-1α, and TNF-α were measured using ELISA kits from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The sensitivity of the kits is 30 pg/ml sVCAM-1 and sICAM-1, 2 pg/ml MCP-1, 1 pg/ml IL-1α, and 5.1 pg/ml TNF-α.

mRNA levels of inflammatory mediators.

Total RNA was isolated from mouse aorta, heart, and lungs using TRIzol Reagent from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). mRNA levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, MCP-1, TNF-α, IL-6, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were quantitated using real-time RT-PCR. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using the High Capacity cDNA Archive Kit from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). All TaqMan primers and probes were purchased as kits (Assays on Demand; Applied Biosystems). Real-time RT-PCR was performed in 50-μl reaction solutions, with standard curves constructed for each gene in every PCR run, using a DNA Engine Opticon 2 Real-Time PCR Detection System from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Waltham, MA). After normalization to internal GAPDH in each sample, the results for each target gene were expressed as the fold change of control.

Protein levels of inflammatory mediators.

Mouse hearts were isolated and homogenized in lysis buffer [0.1 mol/l K2HPO4, 1 mmol/l phenylmethylsolfonyl fluoride, 0.2% Triton X-100, and 0.1% protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340; Sigma)]. The homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 30 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected. The protein content of the lysate was determined by the BCA protein assay (Pierce, Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of protein (50 μg) were electrophoresed on 15% SDS polyacrylamide gels, electrotransferred to a ProTran nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Riviera Beach, FL), and blotted with the following primary antibodies: goat anti-mouse VCAM-1 (R&D Systems), rat anti-mouse ICAM-1 (Abcam, Boston, MA), rabbit anti-mouse MCP-1 (Abcam), and rabbit anti-mouse GAPDH (Abcam). All horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies, including chicken anti-goat, goat anti-rat, and goat anti-rabbit, were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA). Blots were developed using the SuperSignal pico ECL kit (Pierce, Thermo Scientific). Molecular band intensity was determined by densitometry using NIH ImageJ software.

Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase activity.

Activity of copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD) in heart was determined using the commercial colorimetric SOD assay kit from Dojindo Molecular Technologies. The assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the SOD activity was expressed as the percentage inhibition of the competitive WST reaction with superoxide by SOD per milligram protein.

Activation of nuclear transcription factors.

Nuclear proteins were extracted immediately after animal death from heart and lungs using a nuclear protein extraction kit from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA). The DNA binding activity of NF-κB (p65) and AP-1 (c-fos) was quantitated using Trans-AM ELISA kits from Active Motif, following the manufacturer's instructions. Competition with either wild-type or mutant oligonucleotides for NF-κB (p65) or AP-1 (c-fos) was performed to confirm specificity of DNA binding.

Statistical analysis.

All results were calculated as means ± SE and analyzed using unpaired Student's t-test and one-way ANOVA (Bonferroni correction) followed by multiple comparisons as appropriate. Differences were considered statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level.

RESULTS

Treatment of C57BL/6n mice with TTM does not cause hepatotoxicity or histopathological abnormalities.

After 21 days of treatment, mean body weight and body weight gain did not differ between TTM (30 mg·kg−1·day−1) and non-TTM-treated mice (Table 1). All animals maintained normal physical activity except one TTM-treated mouse that exhibited weakness, possibly because of moderate anemia, which may have been indirectly caused by the decrease in ceruloplasmin activity (see below). The serum level of ALT, a specific marker of hepatotoxicity, was not elevated by TTM treatment (Table 1). Furthermore, no abnormalities were observed in the kidneys and liver of TTM-treated mice by histopathological analysis.

Table 1.

Mouse body weight and serum ALT levels

| Non-TTM Treated | TTM Treated | P Value (t-test) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body wt, g | 23.6 ± 0.2 | 24.4 ± 0.5 | 0.22 |

| Body wt gain, g | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 0.50 |

| Serum ALT, U/l | 23.6 ± 2.3 | 18.9 ± 3.3 | 0.14 |

Data are presented as means ± SE. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; TTM, tetrethiomolybdate.

TTM effectively reduces bioavailable copper.

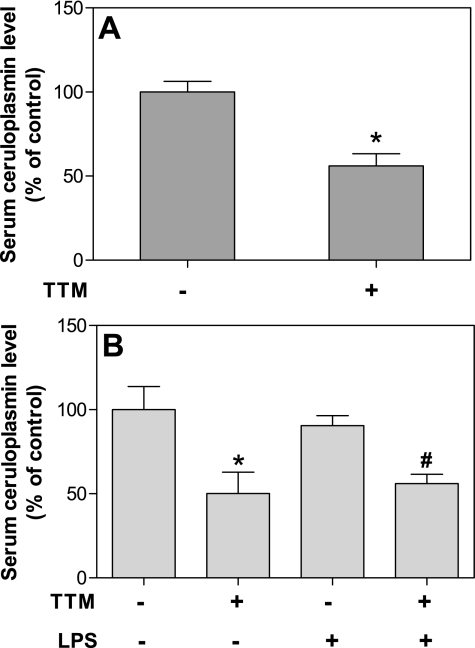

To eliminate possible confounding effects from high copper levels in the standard mouse diet (usually 24 ppm), we used a diet containing 9 ppm copper, which is considered an adequate amount. The copper-containing protein, ceruloplasmin, is produced in a copper-dependent manner and secreted in the bloodstream by the liver. Hence, ceruloplasmin is an established surrogate marker of body copper status and has been used to assess the efficacy of TTM treatment to lower copper status of experimental animals and humans (9, 11, 14). We found that treatment of mice with TTM for 21 days significantly reduced the mean serum ceruloplasmin level by 44% compared with non-TTM-treated mice (P < 0.05, t-test) (Fig. 1A). In addition, exposing the animals to LPS (50 μg ip) for 3 h did not affect serum ceruloplasmin levels (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Treatment of mice with tetrathiomolybdate (TTM) effectively reduces serum ceruloplasmin. Mice were gavaged daily with TTM (30 mg/kg body wt) or water for 21 days and then were given an ip injection of lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 50 μg) or saline buffer. Three hours later, the animals were killed, and blood was collected for measurement of serum ceruloplasmin as described in methods. A: ceruloplasmin levels of TTM and non-TTM-treated groups (n = 10 mice for each group). *Statistically significant difference from non-TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, t-test). B: ceruloplasmin levels of control, LPS, TTM, and TTM- plus LPS-treated groups (n = 5 for each group). *Statistically significant difference between the control and TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, ANOVA). #Statistically significant difference between the LPS and TTM- plus LPS-treated group (P < 0.05, ANOVA). Data are presented as means ± SE.

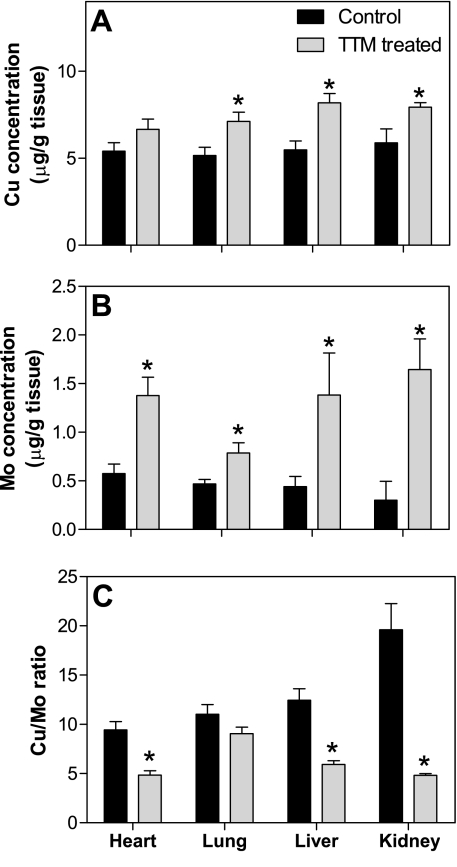

TTM increases tissue copper and molybdenum levels but strongly decreases the copper-to-molybdenum ratio.

Treatment of mice with TTM significantly increased copper levels in liver, kidneys, and lungs by 49, 35, and 38%, respectively (P < 0.05, t-test) and nonsignificantly increased the copper level in the heart by 23% (P = 0.13) (Fig. 2A). Concomitantly, the molybdenum level also increased in heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys by 2.4-, 1.7-, 3.1-, and 5.5-fold, respectively (P < 0.05, t-test) (Fig. 2B). Although endogenous molybdenum is a component of molybdopterin, which is associated with, e.g., the xanthine oxidase and sulfite oxidase families of enzymes (40, 41), the high levels of molybdenum observed in the present study (Fig. 2B) result from the accumulation of TTM in tissues.

Fig. 2.

Treatment of mice with TTM increases tissue copper and molybdenum levels and strongly decreases the copper (Cu)-to-molybdenum (Mo) ratio. Animals were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Heart, liver, kidneys, and lungs were collected immediately after animals were killed. Tissue copper (A) and molybdenum (B) were measured by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) as described in methods. C: the ratio of copper to molybdenum in various tissues. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 10 for each group). *Statistically significant differences from non-TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, t-test).

Because chelation of copper by TTM makes it unavailable for biological functions, the ratio of copper to molybdenum is a suitable marker of bioavailable copper, similar to serum ceruloplasmin. We found that TTM significantly reduced the copper-to-molybdenum ratio in heart, liver, and kidneys by 56, 57, and 87%, respectively (P < 0.05, t-test) and nonsignificantly in the lungs by 21% (P = 0.19) (Fig. 2C). These data indicate that the tissue levels of bioavailable copper were effectively reduced by TTM treatment, consistent with the lower serum ceruloplasmin level (Fig. 1).

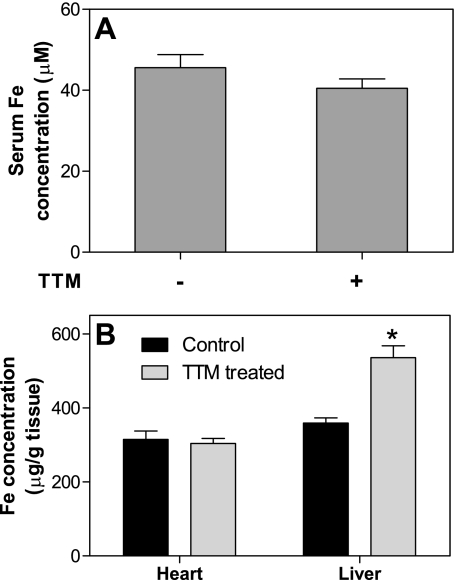

TTM does not affect iron levels in serum and heart but significantly increases hepatic iron.

The ferroxidase activity of ceruloplasmin is required for the mobilization of iron from the liver. Therefore, we investigated whether iron homeostasis was affected by TTM. Although the serum iron level decreased slightly but nonsignificantly by 11% following TTM treatment (P = 0.22, t-test) (Fig. 3A), the iron level in the heart was not affected (Fig. 3B). In contrast, TTM significantly increased the hepatic iron level by 49%, indicating that ceruloplasmin-related iron transport was strongly suppressed (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Treatment of mice with TTM does not affect iron levels in serum and heart but significantly increases hepatic iron. Animals were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Iron levels in serum (A) and heart and liver (B) were measured by ICP-MS as described in methods. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 10 for each group). *Statistically significant difference from non-TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, t-test).

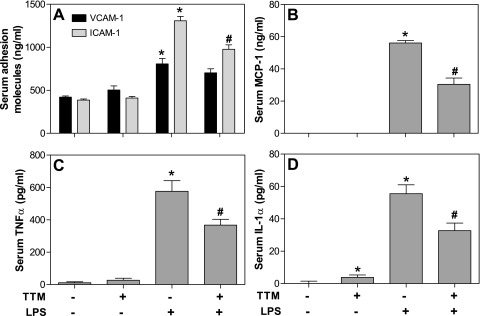

TTM inhibits the LPS-induced increase of inflammatory mediators in serum.

Although there were no statistically significant differences in the mean levels of serum sICAM-1, sVCAM-1, MCP-1, and TNF-α between the non-TTM-treated control group and the TTM-treated group, serum IL-1α was slightly elevated in the latter (P < 0.05, t-test) (Fig. 4). As expected, intraperitoneal administration of LPS (50 μg) within 3 h induced a significant increase in the serum levels of all inflammatory proteins measured (Fig. 4). Prior treatment with TTM strongly inhibited the LPS-induced increase of serum sICAM-1, MCP-1, IL-1α, and TNF-α by 25, 46, 41, and 36%, respectively (P < 0.05, ANOVA) and moderately, but nonsignificantly, inhibited the increase of sVCAM-1 by 13% (P = 0.22, ANOVA) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Treatment of mice with TTM inhibits the LPS-induced increase of serum levels of inflammatory mediators. Animals were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Serum levels of soluble intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1 (A), monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP)-1 (B), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α (C), and interleukin (IL)-1α (D) were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as described in methods. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 5 for each group). *Statistically significant difference compared with control group (P < 0.05, ANOVA). #Statistically significant difference between the LPS and LPS- plus TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, ANOVA).

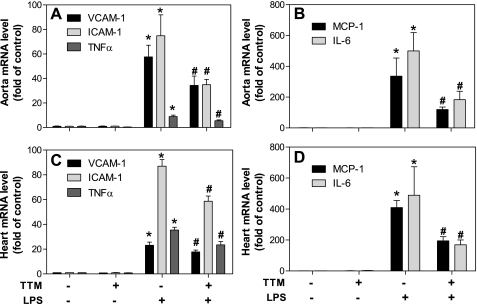

TTM inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory gene transcription in aorta and other tissues.

Treatment of mice with TTM alone did not affect gene expression of cellular adhesion molecules and proinflammatory cytokines in the aorta, as assessed by mRNA levels using real-time RT-PCR (Fig. 5, A and B). As expected, LPS strongly upregulated gene expression of all inflammatory mediators measured. Treatment of animals with TTM significantly inhibited LPS-induced gene transcription by 40, 53, 65, 38, and 63%, respectively, for VCAM-1, ICAM-1, MCP-1, TNF-α, and IL-6 (P < 0.05, ANOVA) (Fig. 5, A and B). Similar results were observed in heart: mRNA levels of all inflammatory mediators were strongly increased by LPS, and this increase was significantly blunted by TTM (P < 0.05, ANOVA) (Fig. 5, C and D). Finally, in the lungs, TTM treatment significantly inhibited LPS-induced gene expression of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and TNF-α by 15, 14, and 57%, respectively (P < 0.05, ANOVA), whereas MCP-1 and IL-6 were not significantly suppressed (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Treatment of mice with TTM inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression in aorta and other tissues. Animals were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Total mRNA was extracted from aorta and heart using TRIzol reagent, and mRNA levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and TNF-α (A and C) and MCP-1 and IL-6 (B and D) were quantified by real-time RT-PCR as described in methods. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 5 for each group). *Statistically significant difference between the LPS-treated and control group (P < 0.05, ANOVA). #Statistically significant difference between the LPS and LPS- plus TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, ANOVA).

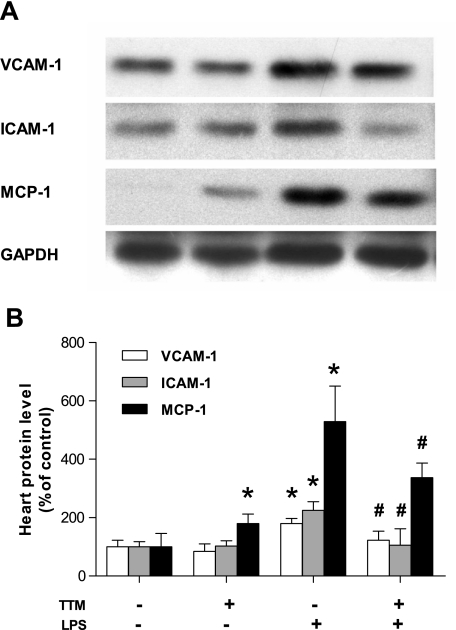

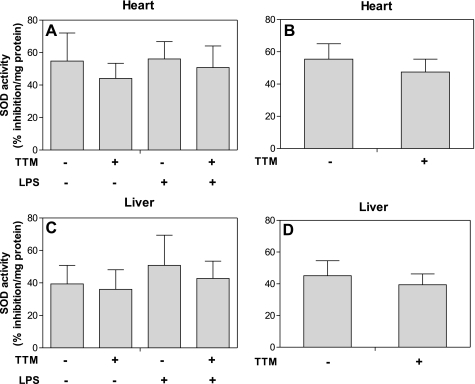

TTM inhibits the LPS-induced increase in protein levels of adhesion molecules and MCP-1 in heart, but does not affect SOD activity.

Analysis of mRNA levels of inflammatory genes in heart and aorta suggested an inhibitory effect of TTM treatment on LPS-induced inflammation. Consistent with mRNA levels, protein levels of VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and MCP-1 in heart were also lower in TTM- plus LPS-treated animals compared with animals treated with LPS only (Fig. 6). TTM alone did not change VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 protein levels but moderately increased MCP-1. In contrast, SOD activity in heart and liver was not significantly affected by LPS with or without prior TTM treatment (Fig. 7). TTM alone led to a modest decrease in SOD activity by 15 and 13% in heart and liver, respectively, but these changes were not statistically significant (P = 0.49 and 0.65, respectively, t-test).

Fig. 6.

Treatment of mice with TTM inhibits LPS-induced protein expression of adhesion molecules and MCP-1 in heart. Animals were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 1. A: total protein was isolated from heart and immunoblotted with anti-VCAM-1, anti-ICAM-1, and anti-MCP-1 antibodies as described in methods. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal loading control. Immunoblots shown are representative of 3 experiments. B: densitometry data of VCAM-1 (open bars), ICAM-1 (gray bars), and MCP-1 (black bars) were generated by analyzing immunoblots with NIH ImageJ software. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 3 for each group). *Statistically significant difference from the control group (P < 0.05, ANOVA). #Statistically significant difference between the LPS and LPS- plus TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, ANOVA).

Fig. 7.

Treatment of mice with TTM does not significantly change copper-zinc superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity in heart and liver. Animals were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 1. Total protein isolated from heart and liver was analyzed for SOD activity as described in methods. SOD activity is expressed as percentage inhibition of the competitive WST reaction with superoxide by SOD. A and C: mean SOD activity of control, LPS, TTM, and TTM- plus LPS-treated groups in heart and liver, respectively (n = 5 for each group). B and D: SOD activity of TTM and non-TTM-treated groups in heart and liver, respectively (n = 10 for each group). Data are presented as means ± SE.

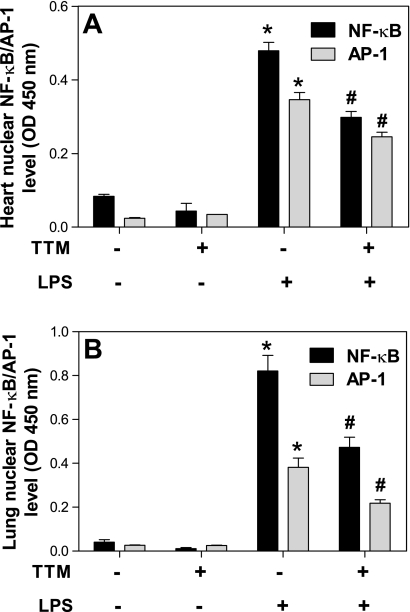

TTM inhibits LPS-induced activation of NF-κb and AP-1 in heart and lungs.

To investigate possible pathways mediating the inhibitory effect of TTM on LPS-induced inflammatory gene transcription, we assessed the DNA binding activity of the NF-κB subunit, p65, and the AP-1 subunit, c-fos, as indicators of nuclear translocation and activation of these transcription factors. TTM alone did not cause NF-κB or AP-1 activation in either the heart or lungs (Fig. 8). In the heart, LPS significantly increased NF-κB and AP-1 activity by 5.7- and 14.2-fold, respectively (P < 0.05, ANOVA); TTM strongly inhibited this LPS-induced activation of NF-κB and AP-1 by 38 and 29%, respectively (P < 0.05, ANOVA) (Fig. 8A). Similar effects of TTM were observed in the lungs: whereas LPS increased NF-κB and AP-1 activation by 20.4- and 14.6-fold, respectively (P < 0.05, ANOVA), TTM significantly inhibited LPS-induced activation of each transcription factor by 43% (P < 0.05, ANOVA) (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Treatment of mice with TTM inhibits LPS-induced activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB and activator protein (AP)-1 in heart and lungs. Animals were treated as described in the legend of Fig. 1. DNA binding activity of NF-κB and AP-1 in heart (A) and lungs (B) was assayed using ELISA as described in methods. Data are presented as means ± SE (n = 5 for each group). *Statistically significant difference between the LPS-treated and control group (P < 0.05, ANOVA). #Statistically significant difference between the LPS and LPS- plus TTM-treated group (P < 0.05, ANOVA).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that the specific copper chelator, TTM, acts as an efficient anti-inflammatory agent in the setting of LPS-stimulated acute inflammation. The oral dosage of TTM used in our experimental mice, 30 mg/kg body wt, administered for 3 wk did not cause any toxicity, consistent with other studies that used higher doses of TTM (14, 62). A potential concern with TTM treatment is alteration of iron homeostasis because of decreased ceruloplasmin ferroxidase activity, which can lead to iron accumulation in the liver, as observed in the present study. Nevertheless, the good safety index of TTM and its proposed clinical use to treat Wilson's disease make it a potential candidate to also treat inflammatory conditions.

Atherosclerosis is an inflammatory disease of the vasculature characterized by overexpression of cellular adhesion molecules, such as VCAM-1 and ICAM-1; proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-6; and the chemokine, MCP-1 (33, 73). These inflammatory molecules play key roles in recruiting blood monocytes in the vessel wall that give rise to lipid-laden macrophage-foam cells and further propagate inflammation and atherosclerotic lesion development. As expected, in our experiments, LPS exposure of mice triggered gene transcription in the vasculature of the same key inflammatory mediators that also contribute to atherosclerosis.

It is well established that LPS derived from enterobacteria binds to the TLR4, which activates multiple redox-sensitive cell signaling pathways leading to NF-κB and AP-1 activation and inflammatory gene expression in cultured vascular cells (24, 35, 65, 79). Recent studies suggest that activation of TLR4 also plays a role in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. For example, TLR4 mRNA and protein were found to be more abundant in murine and human atherosclerotic plaques than in unaffected aortic areas (22, 74, 82). TLR4 activation has been implicated in hypercholesterolemia-induced arterial inflammation in mice, since knockout of either TLR4 or its adaptor protein, MyD88, reduced expression of proinflammatory cytokines, monocyte recruitment to the vessel wall, and plaque size in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice (5, 54). TLR4 was also found to be correlated with proatherogenic, oxidized low-density lipoproteins (LDL), inflammation, and low shear stress during the early stages of atherosclerosis (83). Therefore, LPS-induced acute inflammation can be employed to probe the anti-inflammatory effect of copper chelation in the cardiovascular system, with possible implications for atherosclerosis.

An increased serum copper concentration has been reported in various inflammatory diseases in humans and laboratory animals (6, 42). On the other hand, TTM has been shown to be a potent anti-inflammatory agent in different animal models of inflammatory diseases (10, 31, 48, 49, 58). In our study, consistent with previous findings, TTM alone did not affect the basal expression of adhesion molecules or proinflammatory cytokines and MCP-1 in aorta and heart but strongly inhibited LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression in these cardiovascular tissues. This inhibitory effect of TTM was also observed with respect to lower protein levels of inflammatory mediators in the heart.

We also investigated inflammatory gene expression in the lungs. As an important inflammatory response organ, the lungs are protected by the innate immune system, which acts as a first-line defense against the infiltration of foreign pathogenic microorganisms. We found that TTM effectively inhibited expression of adhesion molecules and TNF-α in the lungs. These data confirm that copper is involved in the activation of the innate immune system, which also plays an important role in atherosclerotic pathology.

To investigate possible underlying mechanisms of the anti-inflammatory effect of TTM, we analyzed NF-κB and AP-1, two key transcription factors for inflammatory gene expression in cells, including aortic endothelial cells (84). We found that TTM strongly inhibited LPS-induced activation of both NF-κB and AP-1 in mouse heart and lungs. Because of the limited quantity of aortic tissue, we could not extract enough nuclear protein for assessment of NF-κB and AP-1 activation in the aorta; however, it is likely that the responses to LPS and TTM are similar in aorta and heart.

Our finding that TTM inhibits NF-κB activation is in agreement with previous observations that TTM downregulated angiogenesis and tumor metastasis by inhibiting NF-κB activation (9, 61). NF-κB was also suggested to be the pivotal regulator when TTM was combined with doxorubicin to induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells (60). Our data demonstrate that both NF-κB and AP-1 are targets of TTM modulation and play important roles in mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of TTM when the innate immune system is activated by LPS.

Copper is an essential trace element required for many biological processes (25). For example, copper is required for cellular energy generation (cytochrome c oxidase), free radical detoxification (copper-zinc SOD), and iron homeostasis (ceruloplasmin) (19, 45). As indicated above, copper also plays an important role in innate immunity (64), and dietary copper deficiency significantly decreases neutrophil function (3).

Interestingly, copper-zinc SOD has been shown to play a role in LPS-induced inflammatory responses in mouse peritoneal macrophages (50). It also has been suggested that copper deficiency can lead to decreased copper-zinc SOD activity and subsequent aberrant reactive oxygen species production, which may modulate inflammatory responses (21, 37, 47). However, our data indicate that SOD activity in heart and liver was not significantly affected by TTM treatment under our experimental conditions, suggesting that TTM imparts its anti-inflammatory effects independent of modulating SOD activity. The differential effects of TTM on SOD activity and serum ceruloplasmin can be explained by the prioritized copper chaperone system, which secures copper supply for enzymes of critical importance for cell survival, such as cytochrome c oxidase and SOD, even in copper-deficient states (4).

As a redox-active metal ion, copper may directly exert pathogenic effects. For example, copper can stimulate oxidative modification of LDL in vitro, although it is doubtful whether these results are relevant in vivo (70, 76). It has also been shown that ceruloplasmin, a pathophysiologically more relevant source of redox-active copper, can oxidatively modify LDL (2, 26, 57). Hence, lowering ceruloplasmin levels with TTM, as observed in the present study and previously (14, 66), may also lower LDL oxidation in vivo, and hence slow the progression of atherosclerosis. The direct effect of copper on vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis has been studied through an implanted silicon-copper cuff around rat carotid arteries (75). The copper ions released from the cuff stimulated arteriosclerotic-like neointima and lesion formation, which suggests that copper may potentiate atherosclerotic lesion development in vivo.

In conclusion, our data indicate that copper chelation with TTM inhibits LPS-induced inflammatory responses in vivo, likely by inhibiting cell signaling processes, resulting in activation of NF-κB and AP-1, two redox-sensitive transcription factors playing a key role in vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Thus chelation of excess copper may be a novel strategy to prevent or treat atherosclerosis and other inflammatory conditions. The link between copper chelation and inhibition of cardiovascular inflammation observed in this study needs to be further investigated in pathologically relevant models of atherosclerosis, such as apolipoprotein E-deficient mice.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine Grant P01 AT-002034. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alvarez HM, Xue Y, Robinson CD, Canalizo-Hernandez MA, Marvin RG, Kelly RA, Mondragon A, Penner-Hahn JE, O'Halloran TV. Tetrathiomolybdate inhibits copper trafficking proteins through metal cluster formation. Science 15: 331–334, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Awadallah SM, Hamad M, Jbarah I, Salem NM, Mubarak MS. Autoantibodies against oxidized LDL correlate with serum concentrations of ceruloplasmin in patients with cardiovascular disease. Clinica Chimica Acta 365: 330–336, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Babu U, Failla ML. Copper status and function of neutrophils are reversibly depressed in marginally and severely copper-deficient rats. J Nutr 120: 1700–1709, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bertinato J, L'Abbe MR. Maintaining copper homeostasis: regulation of copper-trafficking proteins in response to copper deficiency or overload. J Nutr Biochem 15: 316–322, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bjorkbacka H, Kunjathoor VV, Moore KJ, Koehn S, Ordija CM, Lee MA, Means T, Halmen K, Luster AD, Golenbock DT, Freeman MW. Reduced atherosclerosis in MyD88-null mice links elevated serum cholesterol levels to activation of innate immunity signaling pathways. Nat Med 10: 416–421, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bo S, Durazzo M, Gambino R, Berutti C, Milanesio N, Caropreso A, Gentile L, Cassader M, Cavallo-Perin P, Pagano G. Associations of dietary and serum copper with inflammation, oxidative stress, and metabolic variables in adults. J Nutr 138: 305–310, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boring L, Gosling J, Cleary M, Charo IF. Decreased lesion formation in CCR2−/− mice reveals a role for chemokines in the initiation of atherosclerosis. Nature 394: 894–897, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bremner I, Mills CF, Young BW. Copper metabolism in rats given di- or trithiomolybdates. J Inorg Biochem 16: 109–119, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Brewer GJ. Tetrathiomolybdate anticopper therapy for Wilson's disease inhibits angiogenesis, fibrosis and inflammation. J Cell Mol Med 7: 11–20, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brewer GJ, Dick R, Ullenbruch MR, Jin H, Phan SH. Inhibition of key cytokines by tetrathiomolybdate in the bleomycin model of pulmonary fibrosis. J Inorg Biochem 98: 2160–2167, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Brewer GJ, Dick RD, Grover DK, LeClaire V, Tseng M, Wicha M, Pienta K, Redman BG, Jahan T, Sondak VK, Strawderman M, LeCarpentier G, Merajver SD. Treatment of metastatic cancer with tetrathiomolybdate, an anticopper, antiangiogenic agent: Phase I study. Clin Cancer Res 6: 1–10, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brewer GJ, Dick RD, Johnson V, Wang Y, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Kluin K, Fink JK, Aisen A. Treatment of Wilson's disease with ammonium tetrathiomolybdate. I. Initial therapy in 17 neurologically affected patients. Arch Neurol 51: 545–554, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brewer GJ, Dick RD, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkin V, Tankanow R, Young AB, Kluin KJ. Initial therapy of patients with Wilson's disease with tetrathiomolybdate. Arch Neurol 48: 42–47, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brewer GJ, Ullenbruch MR, Dick R, Olivarez L, Phan SH. Tetrathiomolybdate therapy protects against bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. J Lab Clin Med 141: 210–216, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. MI CF, El-Gallad TT, Bremner I, Weham G. Copper and molybdenum absorption by rats given ammonium tetrathiomolybdate. J Inorg Biochem 14: 163–175, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Collins T, Cybulsky MI. NF-kappaB: pivotal mediator or innocent bystander in atherogenesis? J Clin Invest 107: 255–264, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cuaz-Perolin C, Billiet L, Bauge E, Copin C, Scott-Algara D, Genze F, Buchele B, Syrovets T, Simmet T, Rouis M. Antiinflammatory and antiatherogenic effects of the NF-kappaB inhibitor acetyl-11-keto-beta-boswellic acid in LPS-challenged ApoE−/− mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 272–277, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cui JZ, Wang XF, Hsu L, Matsubara JA. Inflammation induced by photocoagulation laser is minimized by copper chelators. Lasers Med Sci 24: 653–657, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dastych M. Copper–biochemistry, metabolism and physiologic function. Cas Lek Cesk 136: 670–673, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dawson TC, Kuziel WA, Osahar TA, Maeda N. Absence of CC chemokine receptor-2 reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Atherosclerosis 143: 205–211, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Donate F, Juarez JC, Burnett ME, Manuia MM, Guan X, Shaw DE, Smith EL, Timucin C, Braunstein MJ, Batuman OA, Mazar AP. Identification of biomarkers for the antiangiogenic and antitumour activity of the superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) inhibitor tetrathiomolybdate (ATN-224). Br J Cancer 98: 776–783, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Edfeldt K, Swedenborg J, Hansson GK, Yan ZQ. Expression of toll-like receptors in human atherosclerotic lesions: a possible pathway for plaque activation. Circulation 105: 1158–1161, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fan H, Sun B, Gu Q, Lafond-Walker A, Cao S, Becker LC. Oxygen radicals trigger activation of NF-kappaB and AP-1 and upregulation of ICAM-1 in reperfused canine heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1778–H1786, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Faure E, Equils O, Sieling PA, Thomas L, Zhang FX, Kirschning CJ, Polentarutti N, Muzio M, Arditi M. Bacterial lipopolysaccharide activates NF-kappaB through toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) in cultured human dermal endothelial cells. Differential expression of TLR-4 and TLR-2 in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 275: 11058–11063, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ferns GA, Lamb DJ, Taylor A. The possible role of copper ions in atherogenesis: the Blue Janus. Atherosclerosis 133: 139–152, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fox PL, Mazumder B, Ehrenwald E, Mukhopadhyay CK. Ceruloplasmin and cardiovascular disease. Free Rad Biol Med 28: 1735–1744, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gitlin JM, Loftin CD. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition increases lipopolysaccharide-induced atherosclerosis in mice. Cardiovasc Res 81: 400–407, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gooneratne SR, Howell JM, Gawthorne JM. An investigation of the effects of intravenous administration of thiomolybdate on copper metabolism in chronic Cu-poisoned sheep. Br J Nutr 46: 469–480, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gosling J, Slaymaker S, Gu L, Tseng S, Zlot CH, Young SG, Rollins BJ, Charo IF. MCP-1 deficiency reduces susceptibility to atherosclerosis in mice that overexpress human apolipoprotein B. J Clin Invest 103: 773–778, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gu L, Okada Y, Clinton SK, Gerard C, Sukhova GK, Libby P, Rollins BJ. Absence of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 reduces atherosclerosis in low density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Mol Cell 2: 275–281, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hou G, Dick R, Abrams GD, Brewer GJ. Tetrathiomolybdate protects against cardiac damage by doxorubicin in mice. J Lab Clin Med 146: 299–303, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hu GF. Copper stimulates proliferation of human endothelial cells under culture. J Cell Biochem 69: 326–335, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hubbard AK, Rothlein R. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression and cell signaling cascades. Free Radic Biol Med 28: 1379–1386, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hynes M, Lamand M, Montel G, Mason J. Some studies on the metabolism and the effects of 99Mo- and 35S-labelled thiomolybdates after intravenous infusion in sheep. Br J Nutr 52: 149–158, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiang Q, Akashi S, Miyake K, Petty HR. Lipopolysaccharide induces physical proximity between CD14 and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) prior to nuclear translocation of NF-kappa B. J Immunol 165: 3541–3544, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Jones HB, Gooneratne SR, Howell JM. X-ray microanalysis of liver and kidney in copper loaded sheep with and without thiomolybdate administration. Res Vet Sci 37: 273–282, 1984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Juarez JC, Manuia M, Burnett ME, Betancourt O, Boivin B, Shaw DE, Tonks NK, Mazar AP, Donate F. Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is essential for H2O2-mediated oxidation and inactivation of phosphatases in growth factor signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7147–7152, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kennedy T, Ghio AJ, Reed W, Samet J, Zagorski J, Quay J, Carter J, Dailey L, Hoidal JR, Devlin RB. Copper-dependent inflammation and nuclear factor-kappaB activation by particulate air pollution. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 19: 366–378, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim WJ, Chereshnev I, Gazdoiu M, Fallon JT, Rollins BJ, Taubman MB. MCP-1 deficiency is associated with reduced intimal hyperplasia after arterial injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 310: 936–942, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kisker C, Schindelin H, Baas D, Retey J, Meckenstock RU, Kroneck PM. A structural comparison of molybdenum cofactor-containing enzymes. FEMS Microbiol Rev 22: 503–521, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kisker C, Schindelin H, Rees DC. Molybdenum-cofactor-containing enzymes: structure and mechanism. Annu Rev Biochem 66: 233–267, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lewis AJ. The role of copper in inflammatory disorders. Agents Actions 15: 513–519, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Libby P, Aikawa M. Mechanisms of plaque stabilization with statins. Am J Cardiol 91: 4B–8B, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Libby P, Ridker PM, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation 105: 1135–1143, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Linder MC, Hazegh-Azam M. Copper biochemistry and molecular biology. Am J Clin Nutr 63: 797S–811S, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Linder MC, Houle PA, Isaacs E, Moor JR, Scott LE. Copper regulation of ceruloplasmin in copper-deficient rats. Enzyme 24: 23–35, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lowndes SA, Sheldon HV, Cai S, Taylor JM, Harris AL. Copper chelator ATN-224 inhibits endothelial function by multiple mechanisms. Microvas Res 77: 314–326, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mandinov L, Mandinova A, Kyurkchiev S, Kyurkchiev D, Kehayov I, Kolev V, Soldi R, Bagala C, de Muinck ED, Lindner V, Post MJ, Simons M, Bellum S, Prudovsky I, Maciag T. Copper chelation represses the vascular response to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 6700–6705, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mandinov L, Moodie KL, Mandinova A, Zhuang Z, Redican F, Baklanov D, Lindner V, Maciag T, Simons M, de Muinck ED. Inhibition of in-stent restenosis by oral copper chelation in porcine coronary arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2692–H2697, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marikovsky M, Ziv V, Nevo N, Harris-Cerruti C, Mahler O. Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase plays important role in immune response. J Immunol 170: 2993–3001, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mason J, Lamand M, Hynes MJ. 99Mo metabolism in sheep after the intravenous injection of [99Mo] thiomolybdates. J Inorg Biochem 19: 153–164, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McAuslan BR, Reilly W. Endothelial cell phagokinesis in response to specific metal ions. Exp Cell Res 130: 147–157, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McElwee MK, Song MO, Freedman JH. Copper activation of NF-kappaB signaling in HepG2 cells. J Mol Biol 393: 1013–1021, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Michelsen KS, Wong MH, Shah PK, Zhang W, Yano J, Doherty TM, Akira S, Rajavashisth TB, Arditi M. Lack of Toll-like receptor 4 or myeloid differentiation factor 88 reduces atherosclerosis and alters plaque phenotype in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10679–10684, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mills CF, El-Gallad TT, Bremner I. Effects of molybdate, sulfide, and tetrathiomolybdate on copper metabolism in rats. J Inorg Biochem 14: 189–207, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Muegge K, Williams TM, Kant J, Karin M, Chiu R, Schmidt A, Siebenlist U, Young HA, Durum SK. Interleukin-1 costimulatory activity on the interleukin-2 promoter via AP-1. Science 246: 249–251, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Mukhopadhyay CK, Fox PL. Ceruloplasmin copper induces oxidant damage by a redox process utilizing cell-derived superoxide as reductant. Biochemistry 37: 14222–14229, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Omoto A, Kawahito Y, Prudovsky I, Tubouchi Y, Kimura M, Ishino H, Wada M, Yoshida M, Kohno M, Yoshimura R, Yoshikawa T, Sano H. Copper chelation with tetrathiomolybdate suppresses adjuvant-induced arthritis and inflammation-associated cachexia in rats. Arthritis Res Ther 7: R1174–R1182, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ostos MA, Recalde D, Zakin MM, Scott-Algara D. Implication of natural killer T cells in atherosclerosis development during a LPS-induced chronic inflammation. FEBS Lett 519: 23–29, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Pan Q, Bao LW, Kleer CG, Brewer GJ, Merajver SD. Antiangiogenic tetrathiomolybdate enhances the efficacy of doxorubicin against breast carcinoma. Mol Cancer Ther 2: 617–622, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Pan Q, Bao LW, Merajver SD. Tetrathiomolybdate inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis through suppression of the NFkappaB signaling cascade. Mol Cancer Res 1: 701–706, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Pan Q, Kleer CG, van Golen KL, Irani J, Bottema KM, Bias C, De Carvalho M, Mesri EA, Robins DM, Dick RD, Brewer GJ, Merajver SD. Copper deficiency induced by tetrathiomolybdate suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 62: 4854–4859, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Park SK, Yang WS, Han NJ, Lee SK, Ahn H, Lee IK, Park JY, Lee KU, Lee JD. Dexamethasone regulates AP-1 to repress TNF-alpha induced MCP-1 production in human glomerular endothelial cells. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 312–319, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Percival SS. Copper and immunity. Am J Clin Nutr 67: 1064S–1068S, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Prince LS, Okoh VO, Moninger TO, Matalon S. Lipopolysaccharide increases alveolar type II cell number in fetal mouse lungs through Toll-like receptor 4 and NF-kappaB. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L999–L1006, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Redman BG, Esper P, Pan Q, Dunn RL, Hussain HK, Chenevert T, Brewer GJ, Merajver SD. Phase II trial of tetrathiomolybdate in patients with advanced kidney cancer. Clin Cancer Res 9: 1666–1672, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Reelfs O, Tyrrell RM, Pourzand C. Ultraviolet a radiation-induced immediate iron release is a key modulator of the activation of NF-kappaB in human skin fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol 122: 1440–1447, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Ross R. Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340: 115–126, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Schosinsky KH, Lehmann HP, Beeler MF. Measurement of ceruloplasmin from its oxidase activity in serum by use of o-dianisidine dihydrochloride. Clin Chem 20: 1556–1563, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Seeger H, Mueck AO, Lippert TH. The inhibitory effect of endogenous estrogen metabolites on copper-mediated in vitro oxidation of LDL. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 36: 383–385, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Suska F, Gretzer C, Esposito M, Emanuelsson L, Wennerberg A, Tengvall P, Thomsen P. In vivo cytokine secretion and NF-kappaB activation around titanium and copper implants. Biomaterials 26: 519–527, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tanaka C, Kamata H, Takeshita H, Yagisawa H, Hirata H. Redox regulation of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced interleukin-8 (IL-8) gene expression mediated by NF kappa B and AP-1 in human astrocytoma U373 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 232: 568–573, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. van de Stolpe A, van der Saag PT. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1. J Mol Med 74: 13–33, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Vink A, Schoneveld AH, van der Meer JJ, van Middelaar BJ, Sluijter JP, Smeets MB, Quax PH, Lim SK, Borst C, Pasterkamp G, de Kleijn DP. In vivo evidence for a role of toll-like receptor 4 in the development of intimal lesions. Circulation 106: 1985–1990, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Volker W, Dorszewski A, Unruh V, Robenek H, Breithardt G, Buddecke E. Copper-induced inflammatory reactions of rat carotid arteries mimic restenosis/arteriosclerosis-like neointima formation. Atherosclerosis 130: 29–36, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Vruwink KG, Gershwin ME, Sachet P, Halpern G, Davis PA. Modification of human LDL by in vitro incubation with cigarette smoke or copper ions: implications for allergies, asthma and atherosclerosis. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 6: 294–300, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang X, Zhang J, Su Y, Li C, Feng W, Zhang Z. Effect of thermal injury on LPS-mediated Toll signaling pathways by murine peritoneal macrophages: inhibition of DNA-binding of transcription factor AP-1 and NF-kappaB and gene expression of c-fos and IL-12p40. Sci China C Life Sci 45: 613–622, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Westerterp M, Berbee JF, Pires NM, van Mierlo GJ, Kleemann R, Romijn JA, Havekes LM, Rensen PC. Apolipoprotein C-I is crucially involved in lipopolysaccharide-induced atherosclerosis development in apolipoprotein E-knockout mice. Circulation 116: 2173–2181, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Wu GJ, Chen TL, Ueng YF, Chen RM. Ketamine inhibits tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-6 gene expressions in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated macrophages through suppression of toll-like receptor 4-mediated c-Jun N-terminal kinase phosphorylation and activator protein-1 activation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 228: 105–113, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Xiong S, She H, Sung CK, Tsukamoto H. Iron-dependent activation of NF-kappaB in Kupffer cells: a priming mechanism for alcoholic liver disease. Alcohol 30: 107–113, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Xiong S, She H, Takeuchi H, Han B, Engelhardt JF, Barton CH, Zandi E, Giulivi C, Tsukamoto H. Signaling role of intracellular iron in NF-kappaB activation. J Biol Chem 278: 17646–17654, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Xu XH, Shah PK, Faure E, Equils O, Thomas L, Fishbein MC, Luthringer D, Xu XP, Rajavashisth TB, Yano J, Kaul S, Arditi M. Toll-like receptor-4 is expressed by macrophages in murine and human lipid-rich atherosclerotic plaques and upregulated by oxidized LDL. Circulation 104: 3103–3108, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Yang QW, Mou L, Lv FL, Wang JZ, Wang L, Zhou HJ, Gao D. Role of Toll-like receptor 4/NF-kappaB pathway in monocyte-endothelial adhesion induced by low shear stress and ox-LDL. Biorheology 42: 225–236, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Zhang WJ, Frei B. Intracellular metal ion chelators inhibit TNFalpha-induced SP-1 activation and adhesion molecule expression in human aortic endothelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 674–682, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]